Andrew Collins's Blog, page 49

September 22, 2011

The killing

OK, having tried to comment on this via Twitter and been defeated by the 140-character limit and nitpickers, I'll have another, more considered go here. The United States of America, a country that still purports to "export democracy" around the world, upholds the death penalty in all but 14 of its 5o states, with four in a constitutional grey area, where it hasn't been abolished but has not actually been used since 1976. (From reading up on it today, I discover that New York and Masachusetts have no death row, but capital punishment is "retained in law.") Last year, there were 46 executions in America, 44 by lethal injection, one by electric chair and, I kid you not, one by firing squad in Utah. That's down from a score of 52 in 2009, and 85 in 2000. The trend seems to be away from killing people for killing other people, but it's still very much in the nation's judicial portfolio. A poll conducted at the end of last year by Lake Research Partners puts public opinion very much against it, with 61% of those US voters polled opting for an alternative to death. Full stats here.

The fact remains, on Wednesday night, at the same allotted hour, in two different states, two different men were given a similar lethal injection. I am not the first to spot this. There is a very good, clear comparison on the Huffington Post by Trymaine Lee, which you may care to read. But I'll precis: Troy Davis, 42, was executed in Butts County, Georgia, for killing a policeman, Mark MacPhail, in Savannah, in 1989. Laurence Russell Brewer, 44, was executed in Jasper, East Texas, for killing James Byrd Jr in the same town, in 1998.

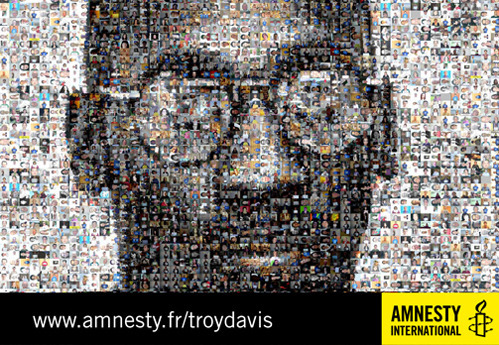

Amnesty International and the NAACP backed the campaign to give Davis a new hearing. He had always protested his innocence, a number of witnesses apparently withdrew their testimony, and the gun with which Davis was charged with shooting MacPhail was never found. His death was a blow to those who had tried to so hard to see justice done. If the state of Georgia had no death penalty, he would still be in prison, but he would be alive, and a retrial might still be possible. Clearly, I have no more idea than you do whether or not he did it. It feels wrong, which is why I err on the side of caution before having someone killed.

The Byrd case is entirely different. He was killed, horrifically – and I won't go into detail, but it's all on the record if you can stomach it – by three men, two of whom were sentenced to death – Brewer and John William King, both self-proclaimed white supremacists (King has yet to be executed) – and a third, Shawn Allen Berry, against whom insufficient evidence could be found, and who said the other two did it, and who is in protective custody, serving life. (So, while Davis was black and his victim white; here, it was the other way around.) Brewer never denied committing the crime, or his hateful reasons for doing it, and indeed, before he died, he claimed he had no regrets and would do it again. He seems to be something of a monster.

In the second case, the only doubt surrounds the extent, and motivation, of Berry's involvement. (All three were in the same pick-up truck.) In the Davis case, it seems far less clear cut. Either way, and here's where I make my statement: I don't believe that killing Davis or Brewer is right.

I am currently reading Margaret Thatcher's memoir The Path To Power, as I've mentioned before, and we're in 1968, she's a Conservative MP in opposition and on the shadow cabinet, and she's just voted to lift the suspension of the death penalty in England, Wales and Scotland. (It was suspended here in the year of my birth and voted on every year in Parliament until 1969 when it was made permanent.) I'm not surprised, of course, to read that one of this country's most right-wing politicians would vote in favour of the state-sanctioned murder of individuals, but it brings it all closer to home. That's only 40 years ago, and in fact, the death penalty remained, legally, until 1998 for the exciting sounding crimes of treason and piracy. But the European Convention on Human Rights stopped all that nonsense and for as long as this country is a member of the Council of Europe, we can't kill anybody. Except "in times of war or imminent threat of war". You can chew that over among yourselves.

My argument is an absolutist one, and it's one that's not political, just instinctive. If we are to hold up willful murder against an unwilling victim as a crime, which we should, then how are we, as a society, to maintain our moral superiority if we, as a society, endorse the murder of murderers? I know there are still people in this country who would "bring back hanging" for murderers, or at least, those murderers who seem more despicable for, say, murdering children, or for torturing and then murdering. It's easy and understandable to get all Old Testament in the heat of the moment, but take a breath and first ask yourself: would you administer the injection, or even stand and watch the person's life ebb away? OK, some hardened pro-death lobbyists would say, yes I would. Fair enough, you have the courage of your convictions. But I would argue that if you take this to its logical conclusion, murder can no longer be a crime if murder is state-sanctioned. And then murderers would not be criminals.

I used the caveat "against an unwilling victim" earlier so as to skilfully remove the equally thorny issue of assisted suicide from this debate. Again, discuss that among yourselves, but if someone wants to die and convinces a loved one to administer a lethal dose or turn off a machine, it's something other than straightforward murder.

I think I'm writing this down because under the BBC News website story about Troy Davis, which rightly caused emotions to run high, somebody had posted something about the US having the "guts" the rid the streets of its "vermin." This struck me as inappropriate, and baffling. Maybe it's been removed by a moderator by now, but hey, free speech and all that. It made me angry that anybody could be so bloodthirsty and driven by vengeance, so I Tweeted about it and got in a mess. I described it in a Tweet as a "lovely comment" and someone actually asked me if I was being sarcastic or not.

I hope it's clear where I'm coming from now anyway. When two men are executed for committing – or being convicted of committing – such very different crimes, it puts a strain on anyone's liberal certainties. But that's where I got to.

September 20, 2011

Please RT

Hey, this is my blog. You are reading it. I thank you for that. Some of you subscribe to it. And I thank you for that, too. But for the last three months, I've been writing a regular film-related blog for the all-new, singing, dancing, listing Radio Times website. It's called Take Two, because we didn't want it to be called anything with the word "Reel" in it, and I seem to have already written nine of them. You can see them all here. The blogs under this banner tend to be shorter, tangential and discursive, rather than grand, opulent reviews of films, but you might find something there to stimulate a response. My latest one is about being distracted by recognising a lesser-known actor in a film and being unable to get back into the plot. That one is here.

I was asked by a friend of my teenage nephew the other day what I did for a living. I rather obliquely used the line, "I rearrange the English language." I wish I had just given him the straight answer he deserved, but I was feeling coy. In any case, it is precisely what I do for a living. I worry, of course, that one day I will run out of ways to rearrange it. But the project seems to be chugging along quite nicely at the moment. And I've always relished being connected with Radio Times, as it's a magazine I've taken, every week, for virtually my whole life: my parents bought it, and its glossier then-companion TV Times, and now I have it delivered to my door. And if I didn't work for the magazine – something I've done for 12 years – I'd still subscribe.

PS: In searching through my archive to establish which year I was first commissioned to write for Radio Times, I found what I believe was my debut contribution: a "sidebar" called The Perfect Sitcom that went with a larger feature on the artform, and makes odd reading over a decade later, especially one during which I co-wrote 21 episodes of two sitcoms for the BBC, one episode of a sitcom for ITV, and script-edited another for BBC2, after which, I still don't know any more than I knew when, as a viewer, I wrote this:

If there's one thing writers and commissioning editors actually agree on, it's that there's no formula for the perfect sitcom. No-one saw Fawlty Towers coming, Seinfeld ran for three years on NBC before drawing a crowd, and Thames TV were convinced they had a classic on their hands in Tripper's Day because it had Leonard Rossiter in it. Alas, it stank the place out.

So what makes a sitcom great? What, scientifically, separates a Bottle Boys from a Likely Lads? Let's retrace our steps. In America, they often start with an established comic – Dick Van Dyke, Phil Silvers, Ellen DeGeneres, Jerry Seinfeld – and build the plot around them. British stand-ups fare less well in sitcoms, especially old-school entertainers (Jim Davidson in Up The Elephant And Round The Castle, Bruce Forsyth in Slinger's Day), while the post-alternatives stick to sketch shows. So the perfect Britcom requires a great comic actor like Arthur Lowe or Richard Wilson in a role "written for them" (the ultimate flattery). Having said that, ensemble sitcoms are equally durable, from Dad's Army to Are You Being Served?, where top billing is shared. This is not easy.

One thing's for sure, our sitcom must only run for two series, to avoid cosy repetition a la Last Of The Summer Wine, and to keep the original writer keen. The middle-class Terry And June drawing room setting is out, the working-class Royle Family council house is in (best stick to a middle class writer, though). The professions make fruitful subject matter, although most have been done: buses, shops, rag and bone men, accountants, police, vicars, even security guards (remember Channel Four's weird Nightingales?) Here's one: a sitcom about a reflexologist. It's original. Let's call it Best Foot Forward: featuring an ensemble cast, but led by a big name (the master: David Jason); it mixes gritty, docu-soap realism with Father Ted surrealism. Eight episodes. Oh, and sex. We need the all-important "men's-magazine vote" like Babes In The Wood – perhaps Emma Noble co-stars as the flighty receptionist.

Our perfect sitcom is character-based, not gag-based, yet full of gags, with The Young Ones' cult appeal and Only Fool And Horses' ratings. Crucially, the multi-BAFTA-winning Best Foot Forward must be on the BBC, in order to preserve what Galton and Simpson identified as 'three minutes' quality time'. Plus incidental music performed on a slap bass that sets your teeth on edge (it worked for Seinfeld).

The Abbey habit

Downton Abbey is, believe it or not, just a television programme. It's on ITV1, it's set in the past, it draws upon roughly the same transitional period for the English class system as such previous television programmes as Upstairs Downstairs, Brideshead Revisited and Flambards, and everybody's gone nuts for it. Written by Julian Fellowes, and not indebted to a literary source, it feels very much tailor-made for a Sunday night audience.

When it arrived on our screens last September, it was an instant hit, scoring around 10 million viewers an episode. Period dramas of this type have never really gone out of fashion, but they do seem to have enjoyed a renaissance over the last few years, perhaps as a reaction to the more hi-tech, CGI-dominated, sci-fi entertainments predominantly served up to us. With the fashionable success, either critical or commercial, of US imports like The Sopranos, The Wire and the CSI franchise, with their contemporary grit and violence, you can also see a gap widening for drama set in a less coarse era, when forensic science held no sway, and warfare was only just getting mechanised.

Upstairs Downstairs, to my mind one of the finest TV series this country has ever produced – for ITV, lest snobs forget – set a high bar for the historical saga between 1971 and 1975, and is just as watchable today. It was, however, basically a theatre piece, its action played out against plywood sets, and its occasional forays on location marked mainly by the jarring switch from videotape to grainy film quality. When it launched, without fanfare, and having sat in the vaults at ITV for a year, unloved, its first episode did not score 10 million viewers overnight; it went out at 10.15 on LWT and took its time to bed in.

It felt like bad timing that the BBC revived Upstairs Downstairs last Christmas, just a couple of months after Downton Abbey, when the new kid on the block was so indebted to the old kid. Downton began with the sinking of the Titanic, with a key character onboard; Upstairs Downstairs covered this in its third series, when Lady Marjorie, a major character, perished at sea on the Titanic. Perhaps this is the difference not just between the two programmes, but between the eras in which they were first broadcast. In 1971, it was fine for an ITV period drama to begin with an opening episode whose main storyline was a new parlourmaid starting work at 165 Eaton Place who wasn't quite what she seemed; in 2010, it had to be the sinking of the Titanic and an inheritance crisis.

I can never love Downton the way I loved Upstairs Downstairs. (And when I mention it, as delighted as I was to see it back, and with Jean Marsh still in it, on BBC1, I'm always referring to the 1970s original.) This is not Downton's fault. It's just that it feels the need to ramp up the melodrama and explain everything as it goes along, just in case its audience is feeling a bit too "Sunday night" to keep up. In Maggie Smith's Dowager Countess, Downton has its cartoon character, with her withering one-liners, but it's all a little bit easy, isn't it? I think audiences – even a Sunday night ITV audience – were granted with a little bit more concentration and intelligence. (Can this really be true? I guess there were only three channels in 1971, so competition for our attention was less bloodthirsty and unscrupulous.)

The other thing Downton has against it is hype. ITV1 are rightfully pleased with its success, and it's great for the drama industry that it has found such a Teflon hit; the last thing we need in this country, culturally, is for TV drama – and comedy – to be underfunded in favour of wall-to-wall talent and game shows, and "scripted reality". But the second series, which began on Sunday opposite Spooks, arrived amid fanfare, ticker tape, a twenty-one gun salute and acres of listings-mag, TV and newspaper anticipation (Radio Times caught the mood with its "Souvenir Issue" – my employer hasn't been this excited, and on the money, since Doctor Who came back). It can live up to this hype, but such expectation demands numbers, and numbers are achieved not through taking risks, but throwing more big names at the screen and giving people what they want: big stories, big world events, broad brush strokes.

Watching Upstairs Downstairs – and I've done so on DVD box set in the last couple of years so this is not nostalgia – is like having a long, luxurious bath in the past. Downton is more like being whacked in the face with some rolled-up Wikipedia printouts. I'm not sure I'm made of stern enough stuff for that kind of an assault every Sunday.

September 19, 2011

Endtourage

So, how to end a long-running TV show? By belatedly winding up the Korean War, sending everyone on their way and spelling out GOODBYE in white stones, like M*A*S*H? By kicking the already-damaged fourth wall to pieces and making the final episode about the show being cancelled, like Moonlighting? By playing Don't Stop Believin' by Journey, cutting to a black screen, and never explaining anything, like The Sopranos? Or …

Entourage, made by HBO, but aired here on Sky Atlantic (before that, ITV2), ended last week, after eight seasons since 2004 (or nine, if you count the bisected third as two). Its final episode was not, like M*A*S*H, two-and-a-bit hours long, or, like Cheers, one-and-a-half hours, nor was it a two-parter, like Seinfeld, The X-Files or Friends, or a three-parter, like Battlestar Galactica. It was pretty much a regular episode, except that everything was tied up and it wasn't very funny.

Entourage is a comedy-drama, I guess, although it's 30 mins long (22 with ads), which makes it a sitcom, essentially. It's certainly been uproariously funny along the way, while maintaining a strong dramatic imperative. It's had its ups and down, as any long-running series does, and through it all, the central four-way friendship between movie star Vince and his less successful brother Johnny, his driver Turtle and his manager E, has been its engine. Based, as you probably know, on the real-life New York entourage of Mark Wahlberg (who produces), and their adventures beyond the velvet rope in Los Angeles, it worked best when it offered a semi-fictionalised insight into the movie business, with cameos from real stars and real directors. There's a lot of "as himself" and "as herself" in Entourage, which might make it a bit "in" and a bit pleased with itself, but at its best, it never felt that way. It poked fun at the vacuous business of show, but with great affection, and its guest stars were people like Nick Cassavetes and Randall Wallace.

Of the four, Vince (Adrian Grenier) was always the weakest character, and even when he got into drugs and went out with a porn star in Season Seven, his stories were usually enablers for much more interesting ones for Johnny (Kevin Dillon – a real life less talented brother to the more successful Matt), Turtle (Jerry Ferarra, who lost a ton of weight towards the end of the run and with it some of his outsider charm) and E (Kevin Connolly). The trump card was always Ari Gold (Jeremy Piven), Vince's barrel-chested, alpha-bastard agent, who existed outside of the central entourage, but whose Tasmanian-Devil presence always whipped things up and who will always be remembered for the line, "Hug it out, bitch."

So what went wrong with the final episode? Even though we're constantly being teased with the possibility of a spin-off movie, creator Doug Ellin clearly felt the need to tie everything up neatly with ribbons. This need drove much of the final season, with Vince rehabilitated and ready to fall in love after years of one-night stands, Ari desperate to mend his marriage, E desperate to mend his tiresome relationship with Sloan, Turtle desperate to mend his entrepreneurial business ambitions, and Johnny desperate to mend his fragile, post-Johnny's Bananas career. SPOILER ALERT: they did all of these things. And flew off in a plane to Paris. I never bought Alice Eve's Vanity Fair journalist falling for Vince, or for Vince falling for her. I never bought E sleeping with Sloan's stepmother. I bought Johnny's Bananas, but not the strike led by Andrew Dice-Clay ("as himself", gosh, what a nightmare he seemed). The only strand I bought was Ari's.

The lives of these characters were always at their most entertaining when things were going awry (Turtle's luxury car business; Johnny's part on Five Towns; Vince leaving Ari; the Medellin disaster at Cannes). At the end of the day, things went, like, so totally right. And things got boring. I allow them this closure, of course, as they've given me a lot of pleasure over the years, but how much more fun if Vince had gone on a coke binge, Turtle had got trapped beneath the landing gear of the plane, Johnny set fire to the studio, E came out as gay and had sex with Lloyd, and Mrs Ari took Ari for every cent he had. And Scott Caan's neck finally grew thicker than his head.

Cold feat

If I watched the famous BBC version of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy in 1979, I don't remember much about it. I probably remember it being on, and Alec Guinness being on the cover of the Radio Times, but it's not imprinted on my memory. I have better recall for Secret Army, which aired around the same time, and Colditz, which was much earlier. As such, I have no fidelity to it, nor any overwhelming nostalgia for it, as many people have. I've certainly never read the le Carré book. So … Tomas Alfredson's new adaptation, which has been greeted with high praise in all quarters, and which is set in 1973, making it a period piece rather than a contemporary drama, as was the TV series, is something I'm able to assess cleanly and without prejudice.

It's very good. I admired Alfredson's previous work, Let The Right One In, which was set in the early 80s, and it's not stretching credibility to say that there are overlaps between the two films, even though one is about pre-pubescent vampires in Stockholm, and the other is about the British secret service in London (and Budapest, and Istanbul). As a director, he certainly seems interested in atmospheres. A chill descends over both films. Although while in the former, much of the action takes place outside, in the latter, we're mostly confined to offices.

Gary Oldman has been officially sanctioned, it seems, as a worthy successor to Guinness. Because I don't really remember Guinness, I have no comparison to make. But Oldman is excellent: conveying much without saying anything, carrying the weight of his experience, good and bad, on slight shoulders, showing strength and authority without menace. His George Smiley is a relic from the Cold War, even though the Cold War is still playing out. The British secret service seems like a relic, here, too. Never mind the hi-tech wizardry and political complexity of Spooks; this is the Civil Service, in non-partitioned offices, with files in folders, and folders on shelves, and shelves in libraries that you have to sign in to use. It's all about men. Apart from a cameo from Kathy Burke (for which her old pal Oldman apparently tempted her out of acting retirement), there simply are none. Smiley's wife is never seen, except once from behind, at the back of a shot, and who she is manages to be vital and unimportant at the same time. (Sian Phillips played her on TV, and I understand she was a key player.) I'm sure this all rings true for the time: it's the 70s, but it may as well still be the 60s, or the 50s.

That said, it's a film about men, but not necessarily only for men. It's not macho. There is a nicely maintained air of homoeroticism at work here – another layer of secrets in a world built on secrecy – and it's never overplayed. This adaptation, written by a husband-and-wife team, Peter Straughan and the late Bridget O'Connor, takes us back to a particular time and place and doesn't view it through a modern prism: it is what it is, a time capsule. (With, say, Mad Men, set at a time when women were still very much second class citizens, you sense that its writers occasionally try to redress the balance by making its female characters stronger than the men, through sexist guilt.)

Because I don't know the story in any detail, I have no idea how much it's been concertinaed, but at two hours, it will have been, maybe radically. As such, I'm not sure I cared enough about which of the four main suspects within MI5 was "the mole." We didn't exactly get to know Colin Farrell, Ciarán Hands, Toby Jones or David Dencik, spending far more time with Oldman, Mark Strong (particularly good, and given a really deep and complex character), Tom Hardy, Benedict Cumberbatch and John Hurt. This reduced the central thriller aspect for me; the essential whodunit. I was happy to let the story unfold, especially in the slow, subtle, sometimes impressionistic way it was told, with short scenes thrown in like jigsaw pieces, but the tension wasn't there. I make an honourable exception for the sequence in Istanbul with Tom Hardy, with its nod to Rear Window.

I worry that Tinker Tailor has been the recipient of too much hype. It's very good. A fine cast. Clever writing. Confident direction. But I wonder if its appeal, especially among middle-aged critics, is too predicated on a perhaps dodgy nostalgia for the British 70s, when men were free to do what they liked, the Russians were the enemy, and women took dictation. And you could smoke anywhere.

September 17, 2011

Can you feel the farce?

Here's something new: going to the theatre to see a farce. Well, kind of. I went to the Curzon Mayfair, a cinema, on Thursday night to enjoy the latest NT Live link-up, whereby a performance from the very stage of the National Theatre is beamed live to a number of cinemas up and down this land, and in fact around the world, where it will be nearly live. (If you want to find out more about this fantastic initiative – even more pertient if you don't live in stupid London – check out their website.) The play was One Man, Two Guvnors, adapted by Richard Bean from the 1743 Italian Commedia dell'arte farce Arlecchino servitore di due padroni, or Servant of Two Masters, directed by Nicholas Hytner and starring James Corden, as a modern-day truffaldino, or harlequin. It was a revelation.

A summer smash at the National with five-star reviews stamped on its forehead, here was our chance to see it at cinema prices, and – as per previous NT Live events we've attended, Hamlet and Frankenstein – with the advantage of close-ups and other filmic devices. I didn't know what to expect, not having read any of the reviews, or even really looked into the type of comedy it was. I knew it would be interesting to see Corden back where he belongs, onstage, and I knew he'd been praised from the rooftops for his work in it. I knew it was set in the early 60s, but that was about it. I didn't know anything about it being Italian. So I was quite taken aback when the curtains parted – after some live skiffle songs by a band in period costume – and some actors started acting as if they were perhaps in an episode of On The Buses. They winked at the audience, and declaimed unrealistically, and spoke in comedy voices, and I guess the 1963 setting merely added to the sitcom feel. I thought it was funny, and cleverly written, and when a man who was clearly a woman (Jemima Rooper) turned up, I started to "get it". I was watching a farce. Now, my experience of the theatre is limited. I understand that it's not like watching a film. It's sort of unrealistic by definition. It's men and women on a stage pretending to be something they're not. I like the theatricality of the medium, but it takes a bit of decompression when you're so used to seeing fiction that has been filmed and lit and treated to look real.

One Man, Two Guvnors is basically about Corden's corpulent bodyguard (I'm not insulting him, it's part of the character) taking on two jobs – he works for the woman pretending to be her dead twin brother, and for the posh man (Oliver Chris from The Office and Green Wing) who killed her dead twin brother, both of whom have a trunk, and are expecting a letter from the Post Office, and don't realise that the other is also in Brighton. Confusion ensues. Now that I know it was originally set in 18th century Venice, I can sort of understand it better, but the brilliance of this reworking is that it's been redrawn for a modern audience. As a fan of slapstick as a kid, I really enjoyed the physical silliness. There's a long scene in which Corden, who's really hungry, has to serve both masters a gourmet meal in two dining rooms without either of them finding out, while squirreling away food for himself, and it involves a "member of the audience" being dragged up onstage, and the whole thing might have been out of particularly skilful edition of Crackerjack or Charlie Caroli. It's like pantomime for grown-up theatregoers. It's funny, and mad, and designed by experts to make you hoot out loud, but it's also, I would say, an acquired taste.

The people either side of us were guffawing and crying and squealing with delight. I occasionally snorted and shook my chair, but on the whole, I was appreciating it inwardly. James Corden was incredible: funny on every level. Some of the schtick he did with the trunk, and with a dustbin lid, and with the gourmet meal, and some letters, was exceptional. He moves lithely for a big lad. He also dealt superbly with a seemingly unexpected bit of audience interaction, although I'm prepared to discover that this was also planted and set up. Whichever it was, he either improvised well, or pretended to, and both are skills.

Props also to an actor called Tom Edden, who turned up as an 87-year-old waiter with the requisite shaky hand and pacemaker, and stole the show. He seems to have been singled out in every review I've subsquently read. This was physical comedy of the very highest order, and perhaps the sort that would only work onstage. (Ironically, I was watching it on a cinema screen, but you know what I mean.) Although I am drawn to verbal comedy in my adult life, the childhood slapstick fan still exists within me, and I'm a sucker for a good pratfall. Tom Edden may be the king of this particular discipline.

So, I've gone and seen an actual Italian farce. Tick that one off then. (It made sense of Fawlty Towers, in many ways.)

Resume

Ah, what fun we had with this week's Telly Addict review for the Guardian – you'll see what I mean if you watch it to the end. In it, I review The Body Farm on BBC1, Celebrity Masterchef on BBC1 and the second season of Treme on Sky Alantic. Have a look here.

September 13, 2011

A lotta meatballs

It's been a looooooong time coming, and it was originally logged in the wrong category, and for some reason it's UK only, and the picture used to illustrate it is all out of perspective and makes me look like a ventriloquist's dummy … but it's nice to be back in podcast form, with Josie, and tucked inside the 6 Music portfolio. You may now subscribe via iTunes and listen to 50 minutes of the non-music bits from Saturday's show on the very first Andrew Collins and Josie Long podcast. I guess in some ways it's a luxury to have done five Saturday morning shows that weren't made into podcasts; in any case, here we are, bedded in, getting used to each other, mucking about, starting with one thought and ending up on an entirely different one, and reliant, as ever, on your contributions in terms of jingles, texts, emails and Twitter contributions. It's a fun show to do. Josie's enthusiasm is quite extraordinary, and it's hard to imagine anyone so grateful and delighted to be on the radio. It's her show, really, and I'm happy to help. This week, with your assistance, we invented a band, Dublin Robot, who now have a detailed backstory, again thanks to your archaeological input, and whose first record we intend to play next Saturday.

As if often the way with new podcasts, thanks to the unique (ie. arcane) way in which iTunes calculates their "popularity", we rose like a bubble to the top of the charts yesterday. Here is the evidence, which is important, as we've dropped out of the Top 10 already, as the world grows bored of something so old. But it was nice to be there for a bit.

We actually got as high as number 4 after I'd taken this grab. And we were number one in the Music podcasts, which is a bit mad, as it isn't one. Now it's been re-categorised as a Comedy podcast but isn't in the Comedy podcast charts. Ah well. By the way, sorry it's UK only; I suspect that's to do with the licensing of the snatches of music that still find their way into the podcast via beds and intros/outros. It certainly seems to be the case with other podcasts from 6 Music. Hey, subscribe, artificially push us momentarily back up the charts for no discernible reason!

Or just tune in on Saturdays, 10am-1pm, for as long as it lasts. You never can tell.

In other podcast news, thanks to Graham Tugwell, we have two more Collins & Herring Pretend Podcasts from the 6 Music archives in the tank, ie. I've sent the files and blurbs over to the British Comedy Guide for processing. So listen out for those. These are the final Tugwell Tapes, Pts 5 and 6, and feature two "deps" Richard and I did in 2009. Check the BCG for updates. Maybe the next one will be a real one?

September 12, 2011

Moor of the same

Jane Eyre, the latest version of which arrived at the Curzon on Friday, has been adapted for the screen about 30 times in numerous languages over the years, and it was only while watching it on Saturday afternoon that I realised I've never seen it.

I knew I'd never read it – to be honest, it's the sort of literary classic that, if I wasn't taught it on the syllabus at school, I was never going to seek out for my own pleasure – but assumed that I must have seen one of the many TV adaptations at least. I know it's the one with Mr Rochester in it, but that, it seems, is the kind of information that seeps in by osmosis. I know this: I didn't recognise the plot as it unfolded in Cary Fukunaga's adaptation.

This also means I can't compare it to, say, the famous 1940s version with Orson Welles as Rochester, or the more recent Franco Zeffirelli one, with William Hurt as Rochester and Charlotte Gainsbourg and Anna Pacquin as Jane. Nor even the most recent BBC one, with Ruth Wilson and Toby Stephenson. Where have I been? I'm a sucker of costume dramas of this type. I thought I'd collected 'em all. I mean, I've seen Sense & Sensibility in more than one incarnation, and Pride & Prejudice more than that. Likewise, Vanity Fair, North and South, Wives and Daughters, Sons and Lovers, Cranford, Madame Bovary, Middlemarch, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Great Expectations … I've seen Daniel Deronda and The Way We Live Now, and every Hardy in the library. But never Jane Eyre. Weird. (I've even seen the BBC's 2006 adaptation of The Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys, the prequel!)

So, this is the best Jane Eyre I've ever seen. Put that on the poster!

Actually, I can compare it to the other bonnet-based costume dramas I've seen. And it compares well. Mia Wasikowska – previously Alice in Alice In Wonderland – made a pale and windswept but striking and deep Jane, and for an Aussie, her Yorkshire accent was a hell of a lot more convincing than the American Anne Hathaway's, to pluck a recent example. I'm already a big fan of Michael Fassbender, whose Killarney accent did come through a bit in his Rochester, but he was otherwise strong, moody and unknowable (which is a good thing, as he's the man with the secret). I must admit I'm a bit bored of Judi Dench being automatically cast as the mousey/formidable old maid in these things, but enjoyed Jamie Bell coming of age with his whiskers, and Simon McBurney is an actor who I'm only just starting to spot and identify, but he was a scene-stealer as the sadistic Mr Blocklehurst.

Lit flicks like this rely on suitable casting, and a too-modern-looking face can be their undoing, such as – to my mind, and through not fault of her own – Charity Wakefield's in the BBC Sense and Sensibility. (It feels churlish and unfair to use this yardstick, but it's amazing how much an inexplicably modern face can break the spell.) As such, Eyre was well populated – Jane's two "sisters" particularly good in smaller parts: The Borgias' Holliday Grainger, and The Tudors' Tamzin Merchant. Odd to see Imogen Poots in a small role, too, having just recently seen her play a convincing American in the stupid Fright Night, but it takes all sorts.

Shot in Yorkshire, it looked the part, and was as torrid and buttoned-up as it ought to have been, with Jane's indomitable spirit released in just the right amount and at just the right junctures. I wonder if the novel's big "moments" weren't slightly thrown away, as if Fukunaga didn't want to be too obvious – the camera pulls back from the first kiss, and the big revelation upon which the story hinges didn't quite provide the Gothic punch it promised (also, I didn't make the link between the first fire and this seismic reveal, which ought to have been more explicit, I feel – you'll know what I'm talking about if you're already a student of Brontë).

Overall, a decent bash. And one thing I will say, the sound design was exquisite. You really got a sense of the sound of the resonant old houses with their stone floors that our characters are forced to rattle around in. As with Joe Wright's Pride & Prejudice, modern technology didn't interfere, but it provided a new layer of realism, and took us back to the period. Gorgeous music by Dario Marianelli, too (it was his score for Pride & Prejudice, and for Atonement).

I wonder if we shall ever tire of these literary classics being re-made and remodelled? I have a big appetite for them and say: bring on the bustles and bodices. And Keira Knightley's just signed up for Wright's Anna Karenina (having already essayed Lara Antipova and Elizabeth Bennett), so, in the words of her boyfriend's band The Klaxons, it's not over, not over, not over, not over yet.

September 10, 2011

Don't look up

My most vivid memory of September 11, 2001, is of being in a BBC building when the first and second planes hit and suddenly feeling vulnerable. I was in a government building in the centre of a capital city. Two planes had been flown into a building in a major city on the other side of the Atlantic. Enemies of America are by definition of enemies of Britain. The thin veneer of normality had ruptured. This wasn't supposed to happen. I thought, I'm going home.

I'd been inside a studio when the first plane hit, recording a pilot for the as-yet unnamed 6 Music (it was still called Network Y in those prototypical days). The show was My Life In CD. It was eventually presented by Tracey MacLeod when 6 Music went live in March 2003, by which time I had been trained to do the Teatime show. My Life In CD was simply a rock'n'roll Desert Island Discs, in which a famous person would look back over their life by way of ten chosen tracks. I'd already done a pilot with Glenn Tilbrook, and one with Courtney Pine. On September 11, it was the comedian Linda Smith. We'd had a lovely time chatting about her uprbringing and her love of Ian Dury, produced by Frank Wilson, who'd go on to produce Teatime. After the recording, we emerged into the corridor and were immediately dragged into a nearby office by whoever was working in that little corner of Western House to see what was unfolding on TV. The second plane had just hit, and what had seemed like a horrific accident had turned into a horrific attack.

By the time I got home, the towers had collapsed. Like everyone else, I spent the rest of the day watching the news, dazed. We had booked and cancelled a holiday to New York the previous year, and had planned to eat at the Windows On The World restaurant in the North Tower of the World Trade Center. It's not like we would've been in the building that day, but even having booked it for the year before felt surreal. I still had my ticket from going up to the top of the Towers in 1997. That seemed surreal too. What? Those buildings had gone?

By the end of that week, emerging from the daze and having been told again and again by the media that the world had changed, I resisted this truism with every bone of my body. Since George W Bush had stolen the election, I had felt the unsavoury change in mood coming from the White House, as we all had, and although Bush's approval ratings were already through the floor, I sensed that he had seized this horrible moment and captured the zeitgeist with his monosyllabic, simple-minded patriotism. Hearing that we were "all New Yorkers now", I felt the hype bearing down upon me and squeezing my head. As far as I was belligerently and stubbornly concerned, the world had not changed on September 11. I was prepared to accept that America had, but why should that drag in the rest of us?

Resisting what I saw as US imperialism, I ploughed a lonely furrow for a while. I felt less lonely when the marches against the war started. I marched on Sunday 18 November, 2001, against the invasion of Afghanistan, and had to pass on the opportunity to interview the directors of Monsters Inc for Radio 4, but I felt strongly about the situation and hoped that this frivolous decision would be respected as I marched past the Dorchester Hotel on Park Lane where the interviews were taking place alongside a particularly loud knot of young Muslim men chanting pro-Taliban slogans and pointing up the mass of contradictions inherent in what was unfolding. (I marched again, of course, on February 15, 2003, against the invasion of Iraq, and felt a distinct lack of loneliness, although, of course, it was clear that the US and their nodding-dog allies were going to make pretty sure that the world changed at that point. It had long since stopped having anything to do with me.)

The irony of all this is that, as the years passed, and the two wars I'd marched against descended into bloody chaos, and George W Bush managed to get reelected, as did Tony Blair, I became mildly obsessed with September 11, 2001. It became the lightning rod for all of my existing interests in modern warfare, politics, foreign policy, America, empire and 20th Century history. I read voraciously. I stopped pedantically refusing to call it "9/11″. I read books which saw events from an essentially right-wing perspective and from a far-left perspective, as well as tomes such as Lawrence Wright's The Looming Tower and Jason Burke's Al-Qaeda, which took no side. I became hooked on conspiracy theories, too, I don't mind admitting it, and even if you prefer the consensus on such things, 2004′s The New Pearl Harbour by David Ray Griffin is a fascinating read.

I am now convinced that September 11, 2001 did indeed change the world. It enabled neocon foreign policy, which, although a dismal and lethal failure, has reshaped the Middle East and beyond. Obama couldn't have happened without Bush, who would never have been reelected without 9/11 and his fireman's-helmet, mission-accomplished reaction to it. The war in Iraq ultimately did for Tony Blair, among other things, and ushered the Tories back in here. The monetary policy of both Bush and Blair/Brown enabled the crash and recession. You might argue that the Arab Spring wouldn't have happened had the neocon Middle East campaign not failed so miserably. Certainly, all major geopolitical events of that past ten years have their roots in that explosive day in 2001, and the tightening of security, thumping of chests and incitement of extremism (of all stripes) that grew out of it.

Me? I haven't stepped foot on American soil since the trip in 1997 when I went up the South Tower to the Observation Deck, there to observe what can now no longer be observed. The fact that you have to be fingerprinted for the FBI now puts me off, I'll be honest. I got to interview one of the directors of Monsters Inc, Pete Docter, when he was promoting Up two years ago, so that worked out OK, even if the thing I was marching against in 2001 didn't. I've watched all the films. I've seen all the documentaries. I've read all the books – God, even a handful of novels, which I don't normally bother with. I retrospectively purchased the September 11, 2001 edition of the New Yorker on eBay. I am still obsessed with 9/11, as it continues to exert an eerie hold over us in the West, and, I should imagine, in parts of the East.

I would like to return to New York now. See how the old place is getting on. It's one of the greatest cities in the world. When I first went there, wet behind the ears, in 1990, I was advised, "Don't look up." This was when tourists might get mugged, and the best way to advertise the fact that you were a tourist was to look up. I looked up anyway. I'd like to go back so I could look up again.

And we all miss Linda Smith.

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers