Andrew Collins's Blog, page 47

October 29, 2011

You've got the love

This is my 25th Telly Addict TV review for the Guardian, and a reasonable juncture, I think, to thank my two regular producers, the unseen Matt Hall and Andy Gallagher, who produce, direct, shoot and – most importantly – edit it every week. If it's in any way slick, elegant or professional, especially in its use of the clips, it's down to them. I just talk into their camera. This week, in an effort to deliver quantity first, I manage to talk into their camera about five programmes, without tipping over the optimum eight-and-a-bit minute mark: the end of Spooks, BBC1; the end of Celebrity Masterchef, BBC1; the return of Young Apprentice, BBC1; the start of Jamie's Great Britain, C4 and the return of The Walking Dead, FX. It's been tremendous fun doing this every week for half a year, and the lady at Guardian reception actually knows my name now, so long may it continue. It's the only way I'm getting into the building. The link is here.

[image error]

[image error]

October 27, 2011

Arctic role

Eek. I know nature is red in tooth and claw, and I know nature documentaries are as much about death as they are about life, but this particular scene really upset me on Frozen Planet last night. What a hypocrite I am for printing this still. Having whined about the news media showing us Colonel Gaddafi's final moments last week, BBC1 showed me the final moments of a Weddell seal, ingeniously rounded up by a pod of killer whales in the Antarctic, who broke up the ice floe it was basking on from beneath, then, in a coordinated attack, made waves to wash it off with pinpoint accuracy into the icy water. And I'm showing it to you. (Although out of context, it's nothing like as sad.)

As with all dramatic vignettes captured, or created, for nature documentaries (the ultimate in "scripted reality"), this one was cleverly personalised – one seal versus about eight whales – and narrated, by the nation's favourite, ancient, immortal David Attenborough, to accentuate the narrative, which was then underscored by accompanying music. We were led to believe that the seal was doomed, and then safe, and then doomed again, and then safe, until, exhausted and outnumbered by the chase, the poor animal seemed to submit to its fate and allow a whale to pull it down by its tail. It's all in those eyes.

I'm an inveterate animal lover, as you well know. I am the kind of person who would give my last pound to a donkey sanctuary over a children's home. I'm soppy as hell, and more likely to cry at the TV, or in the cinema, if a pet dies than if a man or lady dies. (Fuck me, the fictional character Oregon's fictional horse, Roulette, had me blubbing on Fresh Meat last night, its acting almost as affecting as Jack Whitehall's. If you didn't see it, I won't bother contextualising it, or indeed spoiling it. Just watch it will you?) But I accept that the natural world is a finely balance ecosystem based on one species eating another, and that species eating something smaller, and so on. I am a part of that ecosystem, and I don't even have the nobility to catch and kill my own prey. It's always tough to see death on the television, even in the broadest zoological, ecological and geophysical context.

The Antarctic, and the Arctic, may be in long-term, man-made trouble – something Attenborough's series will not shy away from, you can be certain of that – but the Weddell seal is not endangered. It's doing fine. Killer whales eat to live. They kill to eat (the clue's in the name, although all carnivores should have killer before their name, strictly speaking). Earlier in the same edition of Frozen Planet, some wily Canadian wolves ate a young bison to live. Like the whales, they picked their prey off from the herd and brought it down. It is truly amazing to see animals do things like this, in the wild. It's their gig.

When I interviewed Paul McCartney in 1997, as I am over-fond of relating, I spoke to him about his vegetarianism, which I admired. As a man who has lived in rural surrounds, he backed up his personal decision to not eat animals by conceding that other creatures ate other creatures. When, he said, a hawk swoops down to eat a bird, he doesn't complain, adding. "It's his gig." I've always loved that attitude.

As long as the humans aren't actually intervening and manipulating the drama as it unfolds, I don't mind if they help dramatise it in the edit, and even though I have now watched a Weddell seal's final moments in HD, you might say that it adds to my greater understanding of – and empathy for – the natural world, one for which I already have a hell of a lot of respect. It's better, in many ways, to see a beautiful male polar bear covered in the blood and scratches and bite marks that are a part of his life cycle, as we did last night, than cling to a Fox's Glacier Mint fantasy.

Rest in peace, Mr Weddell. You did no die in vain. As for the killer whales who still haunt my dreams, especially since shamefully and self-gratifyingly paying to see one in a swimming pool in Vallejo, California, in 1994, it's their gig.

October 24, 2011

Well sick

Caught Contagion yesterday, and what a cheery film it is for a Sunday afternoon. It's effectively a disaster movie, which is why I felt intrinsically drawn to it, but instead of the usual CGI-dependent bombast and high-wire thrills, this was all very low key and matter-of-fact. Steven Soderbergh is a curious and vital director; he came from the indie sector and retains that spirit, but he works within the studio system and often with big bucks and big stars. Contagion falls more closely in line with Ocean's Eleven and Erin Brockovitch than Che or Scizopolis, in that it has an all-star cast and is identifiably aimed at a mass audience. In fact, it sort of only works if lots of people go to see it.

The plot is simple – as simple as that of a public information film, in fact: a woman (Gwyneth Paltrow) comes home to Minneapolis from a business trip to Hong Kong, and dies within days of a mystery illness. This is not a spoiler. It's in the trailer. It's the trigger for the whole film. It turns out she has a rare form of pig-bat flu that spreads like wildfire. That's all you need to know. As he did with Traffic, Soderbergh then joins the globalised dots and moves with ease and clarity from one place to the next, plotting the virus's path as it starts wiping us all out. If you've seen Outbreak, it's nothing like Outbreak. Although, as with that film, the scientists are the heroes. There are lots of clever scientists here – Elliot Gould, Jennifer Ehle, Demetri Martin, Kate Winslet, Laurence Fishburne, Marion Cottillard (see what I mean about all all-star cast?) – and for all its disaster movie tropes, it's really a film about the emergency services. What would happen if a novel pathogen spread this fast, and this unstoppably? Well, in Contagion, we pretty much find out. It's been praised for its accuracy and Soderbergh and his screenwriter Scott Z. Burns worked closely with the Center for Disease Control and other experts to get it right.

In this respect, and with H1N1 still fresh in our over-active minds, it's fucking terrifying. (Put that on the posters.) From the first cough – which occurs over a blank screen, the film hasn't even started yet! – you're gripping your armrest, and then feeling self-conscious about who might have gripped the armrest before you. Soderbergh shoots on high-def DV stock, and plays the whole thing muted, like Traffic, and that other global jigsaw Syriana, which he produced, allowing the enormity of the catastrophe to hit us in small jolts, not in huge set-pieces. At one point, Winslet visits the sports stadium that will be pressed into service as a hospital; the scale of the empty hall is as shocking as any frantic later shots of a busy hospital. This is clever, economical filmmaking. We see a couple of characters actually die, one of them shockingly, another of them the subject of a close-up autopsy, but the real shocks come when bodies are calmly zipped into bags. Or when they first cough. One doctor casually mentions to another that his mother died; there are no tears, we have not met his mother, but it's shocking nonetheless. Shocking in its casual delivery.

I am not one to panic. I refused to join in the paranoia when H1N1 led to signs about handwashing being posted all over the BBC and the British Library in 2009. I wash my hands all the time anyway. (I am allergic to my own cat, so I'm forever at the sink after stroking her.) When Jude Law's rogue blogosphere nutter – the character I most identified with, obviously, despite his terrible Australian accent (a nod to Assange?) – tries to break the media blackout on a potential herbal cure, Soderbergh and Burns are able to get a few digs in at the Government and the pharmaceutical industry. One top scientist is refused safe passage home from the frontline as the government plane is rerouted to transport a Congressman. But this is not a film about corporate dominance or even political corruption, it's about science. It's about viruses. It's about human contact. It's about air travel. It's about globalisation and the ease with which the cells from a fluey piglet in Asia can travel to Minnesota overnight. It's about globalisation, but it presents globalisation as a done deal. We can't go back now. If this is going to happen, it's going to happen, and only men and ladies in white coats can save us. This is no doubt true. So we're all going to die. Deal with it.

Contagion is a superbly effective film. Not a date movie. Not a film for the paranoid or worrisome. Just by focussing us on the way we touch everything – bars, cocktail glasses, napkins, folders, door handles, lift buttons, buses, aprons, each other – Soderbergh makes us look at the world differently. This is quite a feat. It's done subtly, too: no dramatic close-ups of fingerprints. The writing, too, is without camp, but with deep impact. Here's a classic line. One surgeon, doing an autopsy, finds something amiss. The other surgeon says, "Shall I call someone?" The first surgeon says, "Call everybody."

If you can handle the truth, go and see it. It's a classic cinematic ride. Actually, you've probably been to see it already after all that viral marketing.

[image error]

[image error]

October 22, 2011

Man covered in blood

This is a picture of a man covered in blood. The man is in the process of being killed. He is in pain. He is about to die. Don't worry, though, he is a fictional character, Sonny Corleone, played by the actor James Caan, being made to look as if he is covered in blood and being killed using special effects in a film, The Godfather. This week, specifically Friday, the front page of every major national newspaper bore a picture, or pictures, of a man covered in blood. The man was in the process of being killed. He was in pain. He was about to die. He was factual and not played by an actor; he was Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, deposed leader of Libya, who was finally, and perhaps inevitably, captured and killed by rebel troops in his home city of Sirte on Thursday. The video footage from which the ubiquitous screen grabs were taken was shown on BBC News in the afternoon, over and over again. I don't know if the footage was shown on Sky News, but I suspect it was.

This was a newsworthy image, from newsworthy footage, and its newsworthiness was never in doubt. Gaddafi was a dictator and he was killed by his own people (with a bit of bombing help from NATO) after 42 years in power. The uprising against him, and the sanctioned NATO assistance, tell us a lot about the so-called Arab Spring, which continues to rage across the Middle East and North Africa, and I'm not debating the need for the world media to cover this story in detail. It's front page news in any year, in any decade, in any country, in any language.

What I question is the decision to run these gory pictures, in many cases blown up to large size for maximum impact. When I went to pick up my paper on Friday morning I was pretty offended by the sweep of bloody faces at my feet in the garage. Gaddafi is dead. Gaddafi was killed. Gaddafi was beaten to a pulp before being shot. We get the picture. But did we actually need to see the picture, without warning? I'm really only talking about the impact of the front cover images here, the ones that were on display in newsagents and garages up and down the land, where tiny children – and, hey, the adult squeamish – were likely to see them.

Clearly, none were more offensively framed than this one, but it's no more or less than we've come to expect from The Sun:

[image error]

I know, I know, the argument runs thus: this image of a bloodied, pre-death dictator was all over the internet within seconds of the footage being released by the National Transitional Council (they don't sound much like a death squad with that name, do they?), so it would be a dereliction of journalistic duty for the mainstream news media not to follow suit and publish/run it. It is, after all, proof of a man's death. And hey, it's already out there. But there is still a difference between the internet, where many unpleasant images are just a click away from the eyes of users of all ages, and stacks of newspapers in a newsagent. It felt a bit like Snuff Day.

It felt to me as if it was OK to run pictures of this particular man in pain and about to die because he was a bad man. I'm not saying he wasn't. But although the Sun went mad with vengeful bloodlust, it was no more exploitative than the other, more "respectable" papers really. (You had to admire the Express and Times, and I think the Star, who at least ran the picture small.) As Billy Bragg stated on Question Time the other week, human rights apply to all humans, and not exclusively to those humans that other humans have deemed worthy. Was there no dignity available for Gaddafi? Had he actually forfeited that human right? You might say yes. After all, when the body of Mussolini was hung on a meat hook from the roof of a petrol station in Milan in 1945, I expect these photos were sent around the world (albeit perhaps with a little less velocity).

As with my recent whine about animal rights, some of you may think me wasting my energy worrying about the dignity of a dead dictator. But it does coarsen our view of the world if men covered in blood, moments before death, are displayed across our newspaper covers. When I was at the NME, we debated long and hard about whether we could print the photograph of Richey Manic after his self-inflicted "4 REAL". If memory serves, we decided against running it as the cover image, and only ran it in black and white on the news pages. It appeared, in full colour, inside the paper. But he was not dead. He was fine. This was 20 years ago, when competition with other media was less stiff, and newspapers were in a less of a panic about copy sales. I guess it took a brave newspaper editor not to run the bloody Gaddafi pic full splash on the front cover.

I'm not sure I always approve of the world I live in.

Muthaf*#@!ng baked potato

I haven't written about Fresh Meat, now five hour-long episodes into its first series of six on C4, but it is officially my favourite comedy of 2011 (certainly my favourite new comedy of 2011 – Modern Family remains the benchmark). It's a comedy drama, strictly, but it works to both briefs. Unlike C4′s more esoteric Campus, which concentrated on the staff of a university, here is a student comedy that concentrates on six freshers in a houseshare at a fictional Manchester seat of learning, and yes, if you really stretch the point, it's a bit like a 21st century Young Ones. Except it isn't.

I remember watching The Young Ones in the early 80s as a teenager and not even really knowing it was about students. I loved it from the word go, and thought Mayall, Edmondson, Planer, Sayle and Ryan were just about the funniest people I'd seen on telly since Cleese, Chapman, Idle, Palin, Jones and Gilliam. I know people bang on about The Young Ones being the first "punk" sitcom, but that's not overstating the case. It was on BBC2 and yet it felt, in 1982, like it was for "us" and not "them." It was a twisted, surreal, cartoon-like rendition of student life where anything could happen, written and performed by young men who were not that long out of redbrick universities (which I know now to be historically relevant, too, as a certain pair of non-redbrick universities were where TV traditionally went for its comedians). Fresh Meat makes no claims to be revolutionary, but it is, in a modest way, as it's about young people, created by two people who are not quite so young but remember what it was like, and instead of either trying to be those young people's best mate it gently mocks them, but without losing empathy for them. Over an hour, that's some achievement. They are feckless layabouts, after all.

Honestly, you will actually care about the six studes in Fresh Meat. They are shallow and pathetic at times, and almost disabled by their own self-consciousness, but they are students in a strange city for the first time, finding their way as so many others have found their way, and it's hard not to warm to their plight. The writing is the key for me; created by Sam Bain and Jesse Armstrong, who've thus far only written the first episode, it's been farmed out to lesser-known names who have picked up the brief and run with it. I'm jealous of them all, of course. The performances are uniformly human, too, if occasionally hidebound by the post-Office acting style. If the cast has "stars" they are Joe Thomas, basically playing Simon from The Inbetweeners with his gelled fringe patted down, and stand-up Jack Whitehall, in his first acting role. I was as suspicious as you of the latter, but believe me, he's brilliant as a grotesque version of his own, posh self. It was he, as JP, who in the first episode uttered the phrase, "muthafucking baked potato" and it's one of my favourite TV moments of the year. All five episodes are on 4OD and the final one's on next Wednesday.

I hope it gets a second series – unlike my second favourite comedy of the year, Sirens (another comedy drama that ran over an hour actually, and was also on C4; it could have easily run for another series) – and I hope all the writers come down with a debilitating but non-threatening illness that means they are unable to write it, so that Sam and Jesse have to go looking for other writers to do it.

I review Fresh Meat, and show clips, on this week's Telly Addict review for the Guardian. Also: Kissinger on More4; Blue Bloods on Sky Atlantic; and Holy Flying Circus on BBC4, which was warmly received, written by a Fresh Meat scribe, Tony Roche, and is exactly the kind of show that BBC4 won't be making any more, because the BBC needs to deliver quality first, apparently.

The Telly Addict link is here.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 19, 2011

Who art in Kevin

This is one of those films I saw quite a while ago, but it's released this Friday, so let's get my feelings down. We Need To Talk About Kevin is a rare beast, in that it's based on a novel that I have read. Yes, a novel that I have read! (If you don't know me by now, you'll never, never, never know that if I'm reading a book, it will be a non-fiction book, as I'm too hungry for knowledge to read things that are made up and with each passing day I become hungrier.) As such, I can be one of those bores who leave the cinema and say, "Well, it's not as good as the book."

Of course the film isn't as good as the book. Whatever film it is, it's going to be shorter than the book, unless it's a tiny book, and when you read the book, you imagined what it would be like, in your imagination, and thus any visual interpretation of the book will be other than your own, and intrinsically disappointing. Unless the film's screenwriter and director happen to have cast, interpreted and shot the film exactly as you imagined it, it's going to feel weird. Also, if you love the book – and we've been down this read recently with One Day – no filmmaker is going to be able to match that love, as they will have had to hack the story back, and details you know will be missing. Sometimes whole characters. Certainly whole scenes. I was once asked to come up with a list of five films that are better than the book for an item on The One Show. Off the top of my head, and up for a fight, I think I chose A Clockwork Orange (because Burgess's book is, while seminal, for me, difficult to read even on a good day, and the film is easier to follow), The Shining (because Kubrick – again! – extracted the right bits from a fairly dense novel and made Jack Torrance the focus and not his son, Danny) and … three others which I can't remember. It's a pretty audacious thing to judge. Better not to compare. As I am about to do …

I came late to Lionel Shriver's book. It was first published in 2003 and I don't believe I picked it up until around 2007, after it had won the Orange Prize. I knew roughly what it was about – although to be fair, this is given away on the blurb on the back, which makes it more interesting and not less – and I knew it was widely acclaimed. I'd also had it recommended to me. I'm sure I must have resisted. It sounded like a book about parenting and wondered if I'd be able to connect with it.

Well, I was able, and it actually offered a lucid insight into parenting. In daring to investigate the issues around a mother who hates her child, from birth, Shriver seems to say the unsayable. By making Kevin something of a monster, as a baby, as a toddler, and eventually as the sociopathic high schooler, but telling the story exclusively from the mother Eva's perspective, the author allows us the cold comfort of possibility that his monstrousness is at least partly in Eva's imagination. Certainly, Franklin, the doughy old softy of a dad, doesn't see him this way. Kevin does bad things, for sure. And if you haven't read or seen it, I won't even hint at what those things might be.

The book is presented as a series of letters written by Eva to her by-now-estranged husband, through which the story gathers momentum. Lynne Ramsay, who directed We Need To Talk About Kevin and co-wrote it with Rory Stewart Kinnear, might not be your first choice to take on such a huge task. Her previous work had been personal, esoteric and impressionistic. And British. Her astonishing debut Ratcatcher was set in the Glasgow in which she grew up, and at a time, 1973, when she was growing up in it. It was raw, and moving, and boldly mixed social realism with moments of quasi-fantasy, certainly rapture, and marked her out from the word go as a talent. (It picked up awards like a magnet.) Her follow-up, Morvern Callar, based on the Alan Warner novel, showed that she could work with existing material, but make that her own, too. It was, if anything, less linear and more fuzzy, and was quite a trip. How would Ramsay – whom I interviewed for Radio 4 at the time and found her humble, likeable and determined – follow this? Well, she didn't.

She got caught up in what sounds like a nightmare, down to adapt and direct her first blockbuster novel, The Lovely Bones, and eventually forced off the project, if I understand it correctly. It can't have been a happy experience, and the only Ramsay credit we've seen between 2002 and this coming Friday was her video for Doves' Black and White Town. This was a tragedy. So all hail We Need To Talk About Kevin; not only does it prove that she's the equal of any bestselling source novel – and would surely have made a far better job of The Lovely Bones than Peter Jackson did – but it puts her back on the circuit.

[image error]

Throwing out the letters and presenting a straightforward narrative, Ramsay and Kinnear nonetheless play with the chronology, and it is this approach that makes the film so intriguing. You really have to pay attention. And even if you see the pivotal event coming, you won't see what comes after it coming. (Unless you've read the book, of course! Luckily, I'd actually forgotten it.) The film grips because of finely tuned performances from Tilda Swinton as the mother who has the joy squeezed right out of her lovely bones, John C Reilly as her soulmate turned antagonist, and Ezra Miller as the teenaged Kevin, all asymmetric fringe and glowering eyes. In chopping the story up into bitesize chunks and throwing them all up the air to see how they land, Ramsay creates a fractured narrative that says so much with glances and glimpses and hints. Usually, when you've seen a film's trailer as many times as regular visitors to the Curzon have done, you look forward to discovering the wider context of the snapshots therein. With this film, you may find that they are merely part of slightly longer snapshots. This also gives the impression of it being a saga remembered. It's not playing out before your very eyes, but in the memory of its chief protagonist.

I really loved it. It's dark and foreboding, hot and stuffy, and convincingly American, and through Swinton's exacting and subtle performance, it provides an X-ray of a mother in distress. It's as if you can see through her translucent, Scottish skin and watch her soul squirming around within. It's not a great film to see if you're thinking of starting a family, especially, I would imagine, if you're the prospective carrier of this progeny.

Lynne Ramsay, still only 41, has yet to put a foot wrong in her career. But while Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar worked on a relatively small canvas, Kevin is much bigger, much more mainstream, but without ever losing its eye for detail, or its feel for the arthouse.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 18, 2011

Narc de triomphe

[image error]

Here is the latest Zelig-style shot of me standing next to some famous people. Actually, you probably don't recognise them, although the gentlemen on the right was in Betty Blue, among many other French films. He is the urbane Jean-Hughes Anglade, one of the four principals in smash hit French cop drama Braquo, whose second season begins on French cable channel Canal+ in November, and whose first season premieres here on FX from October 30. I've seen the first four episodes. It's fantastic. I'm in. And on Friday, I hosted a Q&A about the show at London's Soho Hotel for the British media, with three of the cast, plus executive producer Claude Chelli, who is on the left. The other gentleman, whose impressive head is why many commentators are already calling it "the French Shield", is Joseph Malerba. Here is his head, in character, alongside Anglade's moustache. Their co-stars are Nicholas Duvauchelle (who wasn't in London for the Q&A) and Karole Rocher (who didn't hang around at the reception afterwards).

Critic Stephen Armstrong, who was also on the panel on Friday, wrote a very good introductory piece about Braquo for the Sunday Times' Culture, which is not much use to you here, as it will be hidden behind the Times' paywall. So this is all you need to know in advance:

Braquo will also, inevitably, be compared to The Wire – a comparison underwritten by the fact that Canal+, effectively France's "fourth TV channel", seems to have been forged in the image of HBO, with its strong adult fare and subscription base. It bears some similarity: it's gritty and handheld and exposes the dark underbelly of a large city, in this instance Paris; its central quartet of cops are prone to "crossing the line" in order to bring justice to scumbags, and their maverick methodology means they rub up against their chiefs on a regular basis. What makes it different from The Wire is that it is not especially interested in the criminals. So let's put a stop to the Wire comparisons. Although, having said that, Braquo's creator, writer and predominant season-one director Olivier Marchal, was once a cop, so he has that in common with The Wire's co-creator Ed Burns. Oh, and it also employs novelists as writers.

I shall warn you now, it's violent. In the opening scene of the first episode of eight, it sets out its stall. This is strong stuff. As it's subtitled, we must hope we are getting the full impact of the writing, which is sexually frank and full of expletives. It was odd to watch this episode on the big screen before the Q&A with the French-speaking cast and producer, who were watching it with the English translation. Of the four, Chelli was the most fluent English speaker, and he said he was satisfied with the way it had been subtitled. (It's been done for a British audience – we get "bog" for toilet, for instance.) The cinematically dingy warehouse that seems to pass as a police station in the suburbs of Paris is an atmospheric, tactile base for our rogue cops; it even has its own bar – which, it turns out, is not a wishful fantasy. So this is a glimpse into the world of French urban policing that has its own attractions for a foreign audience.

All cops shows genuflect to American culture, and it's there in Braquo, but it's peculiarly Gallic, too, very moody and a touch existential. There are few laughs. There is little banter. It's incredibly dark, and if the first four episodes are anything to go by, Eddy (Anglade), Theo (Duvauchelle), Roxanne (Rocher) and Walter (Malerba), these four have a habit of making things worse with their reckless procedural ways. And demons? They've got 'em!

What I like is that FX are getting into the imported foreign-language drama groove. BBC4 have made it their trademark with The Killing and Spiral (whose Law & Order-style equal emphasis on the legal system makes it much more officey than Braquo, so the pair can be watched as companions to one another), and SkyArts are currently following suit with the Italian Romanzo Criminale, a period mafia origins story set in Rome whose first episode I enjoyed. I say, the more subtitled dramas the merrier. Who would have guessed five or ten years ago that the boutique channels would be fighting over imports with writing at the bottom of the screen? Let they fight. We, the viewers, are the winner.

It was fun to host a Q&A whose panel were not English, and one of whom, Rocher, spoke through a translator. (I'm hoping that watching Braquo will help me with my French, which is schoolboy at best, and hasn't been tried out in the field since 2005 when I last went to Paris.) I discovered that US imports are all over French TV, and that, less predictably, the biggest bought-in shows out there are The Mentalist, and CSI in all its forms. As for British shows, Chelli was a big fan of The Shadow Line, which hasn't been shown in France, and Red Riding, which has. I was interested to find out that one of the key influences on Marchal in terms of style and story was the lesser-known American cop drama, Joe Carnahan's Narc from 2002, starring Ray Liotta, which I must admit I loved, as it seemed to hark back to 70s classics like The French Connection, which is nice, as there really is a French connection now. (Before the Q&A we had a lively discussion about how the best American cinema was influenced by the French New Wave, and yet, this grew out of a bunch of French critics' love of classic Hollywood directors like Hawks and Hitchcock, so the give-and-take between the two cultures has always been potent.)

Anyway, looks out for Braquo, if you have access to FX. They're about to start work on Season Three in France. And no, Monsieur Anglade didn't really want to talk about Betty Blue. I tried.

[image error]

[image error]

October 17, 2011

Don't touch that donkey

[image error]

Mark Cousins' glorious Story Of Film on More4 continues to delight on a weekly basis, and, after this week's chapter about Bergman, Bresson, Tati and Fellini, I have even more films on a list of must-sees. I was particularly taken by Robert Bresson's Balthazar (or Au hazard Balthazar), which I have never seen; made in 1966, it apparently tells the tale of a donkey through his various owners, who, Cousins said, mistreat him. The moment a black-and-white clip came onscreen, I started to feel uncomfortable. Were they about to show a clip of a donkey being mistreated? If so, it being a French film made in 1966, there seemed to be every chance that actual cruelty might be involved. Fortunately, this was not the case. In fact, Cousins merely showed a fixed shot of Balthazar, looking noble, which was his point about Bresson. But will the film itself upset me? It seems a possibility. I have the celebrated new Greek film Dogtooth sitting there in my Sky+ tank, but I know it has something about cruelty to cats in it – a boy seems to be going after one with some garden shears in the trailer – so I haven't dared watch it yet.

The older I get, the less tolerant I become about animal cruelty. And by animal cruelty, I don't just mean actual animal cruelty – you know, those disgusting stories you read in the papers about kids putting pets in tumble driers, or animals being left to fend for themselves by neglectful owners in sheds or bedrooms, or even, that deranged woman who put a cat in a wheelie bin and walked away – I mean implied animal cruelty in fiction. Of late, I have seen two dogs being subject to implied violence and cruelty in Tyrannosaur, and what looked to me like actual cruelty towards two dogs in the forthcoming Wuthering Heights by Andrea Arnold. (Having mentioned the latter, someone from the film's distributor Artificial Eye reassured me that animal trainers were on set. I don't doubt this. But having seen the film, this did not reassure me, unless both scenes were done with CGI, which I doubt.)

I'm well aware that we live in enlightened times with regards the treatment of animals on films sets. And certainly in Tyrannosaur, the two dogs are not harmed on camera. One is pulled about on a dog lead, but this is as far as it goes; the other is also restrained on a lead while it barks madly at someone. I have no doubt that both dogs are handled by trainers who love them and respect them, and I understand it's very difficult to train a dog with anything other than love and rewards, so it might be said that dog actors are likely to be even better treated than dog non-actors. So we're going to put this one down to my own over-sensitivity on the issue. The two dogs in Wuthering Heights, who must, again, be loved by their handlers, looked to my eyes to be at least made uncomfortable for a few seconds of screen time each. If you've read the book, this happens on the page, and is significant in describing the nature of a human character. However, I don't believe we need to see animals squirm to make a dramatic point. (If anyone else has seen this film, I'd be interested to hear how you felt about it. It's released on 11 November, and has much to recommend it, artistically. I'll review it nearer the date.)

I realise to see Tyrannosaur, a film about horrific domestic abuse meted out to human beings, and be affected so deeply by abuse meted out to pets, I am falling into the cliche of an animal lover. I can't help that. Human actors choose to act in films. Animals do not. In this country, I think I'm right in saying that a film cannot be certificated if it is not passed by animal cruelty organisations. That's as it should be. (Is it voluntary to be passed by the Humane Society in the United States? I think it is.) Again, I think I'm right in saying that laws are more lax in other territories. Remember the video nasty era, and the mythology surrounding "snuff" films? Well, I understand animals are dismembered and killed in films like Cannibal Holocaust (again, how ironic – films about eating humans do not harm humans, but do harm animals). I haven't seen those films. I don't wish to. I'm pretty squeamish about screen violence, but it won't stop me seeing a film – hey, Drive, Kill List, Tyrannosaur, I'm seeing brutally violent films on a regular basis at the moment, and on TV the likes of Boardwalk Empire and forthcoming French import Braquo are pretty damned violent, too. But I'll never get used to cruelty towards animals.

Techniques like tripwires to trip up horses used to be commonplace. S0 when I see some of my favourite classic westerns, I know I am watching animal cruelty. In Apocalypse Now, perhaps my favourite film of all time, an ox is ritually slaughtered before our very eyes, in slow motion, the descending machetes hacking its flesh shown repeatedly. I can't say I enjoy it, but it's in the past. Heaven's Gate had a high body count, too, apparently. I loved Bernardo Bertolucci's 1900, a sometimes overblown Euro-pudding epic about fascism, but in one scene we are invited to understand the cruelty of one character, played by Donald Sutherland, by watching him hang a cat by its collar on a hook on a wall and headbutt it to death. Clearly, Sutherland doesn't actually kill the cat with his head, but – and here we go again – it is seen squirming on that hook, clearly distressed and confused. I have to look away, or fast forward. I can't bear to watch it. As a huge fan of European cinema of the 50s, 60s and 70s, I am always on guard for such moments, when animal life is declared cheap.

And then there's The Shadow Line, Hugo Blick's phenomenal highbrow police drama from earlier this year. In one now infamous scene, Rafe Spall's sadistic villain proves his sadism by threatening to drown a cat. He appears to dunk a real cat in a barrel of water. In real life, he doesn't. It's very cleverly staged. But, in real life, a wet cat runs away from the scene. To even make a cat wet is, to my mind, cruel. Cats hate being wet. Flicking a few drops of water on a cat makes it uncomfortable. So I was against this scene. Also, and here's a grey area, there are a lot of stupid people out there. For most sensible people with the basic degree of empathy for God's creatures, seeing a woman put a cat in a bin would remind you never to put one in a bin. For a tiny minority, it might give them an idea. (We live in a YouTube world, where people will it seems do anything to get themselves noticed, whether that's putting themselves in danger, or a mouse.)

This post is not really about animal cruelty. For the majority of us, it's a given that harming an animal for no good reason is wrong. (In one of the incidents in Tyrannosaur, the character is harming the dog because it has harmed another character; I don't agree with it, but you could argue self defence in a court of law, if it was human against human.) Also, there are those who lead a vegan lifestyle, which does not include me, and that kind of respect for animals is near-religious and about as admirable as any lifestyle choice can be. I allow animals to be killed so that I can eat them, but I choose to spend more money on meat in order than it comes from animals that were not raised in cages or cramped barns without sunlight, and were not pumped full of drugs in order to speed up their lives. That's as much as any carnivore can do.

What worries me is that animal cruelty, the implied kind, seems to be creeping back into the fictional mainstream. The Shadow Line was not making a point about animal cruelty, it was making a point about a character. Wuthering Heights is not making a point about animal cruelty, it is making a point about a character. In many ways, these fictions are respectful to animals; they are saying, this character is such a villain he will harm a cat or a dog – imagine what he might do to a human! But that doesn't help me out. I suspect that as I get even older, I will become even more of a sentimental sop on this issue.

When I was a kid, I was taken to the circus on more than one occasion. And to zoos. I loved them. It took me a long time to change my attitude towards the captivity and exploitation of animals. But once I had turned that moral corner, I could never go back. Circuses no longer use animals as performers. Zoos are all about conservation. Life for animals has improved immeasurably. So let's stop putting them on the stage, Mrs Worthington.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 15, 2011

Haircut

Hello. This week's Telly Addict, featuring a smart new haircut and a very nice black shirt, casts a critical eye over Celebrity Come Dine With Me (C4), the return of Boardwalk Empire (Sky Atlantic), the return of House (Sky1) and Later … With Jools Holland (BBC2). I know, that's four programmes, not the usual three, but we try to offer value. I'll catch up with The Comic Strip, which was on last night, next week. The link is here.

[image error]

[image error]

October 14, 2011

Don't burn this

The end of this month sees the release of National Treasures, a two-disc singles album chronicling what now amounts to 25 years in showbiz for the Manic Street Preachers. That's 38 singles in total, in order, beginning with Motown Junk (and thus excising New Art Riot from their history, because – apparently – it was an EP, not a single) and ending with their new cover of The The's This Is The Day, which is a well chosen cover but inessential. Well, it's commercially essential, as all compilations must be flagged by a loss-leader single, by law. I've been listening to these 38 singles, in order, a lot, as I'm reviewing the album for Word, but you'll have to wait a month for that. The experience has been a rewarding one, but then, I am a fan of the Manic Street Preachers, and put up with the slightly less incendiary later singles by viewing the bigger picture: this is a band who've stuck together, stuck to their political guns, survived the loss of a crucial bandmember, turned the Spanish Civil War and Richard Nixon into hit singles, and never stopped being interesting.

Although I was initially suspicious – perhaps because the first journalist to latch onto them at the NME, where I worked in 1990, was the late Steven Wells, whose predilection for CAPITAL LETTERS and overstatement were not always to be trusted. But their music won me over, and I fell pretty hard for them. They were the first new band I'd met who could virtually recite the previous week's NME, and although they gave me no special treatment initially, despite my love for them (Nicky Wire famously described me to a journalist from our arch-rivals the Melody Maker as a "pork pie dwarf"), we found common purpose and any chance I got to spend time with them, I jumped at it.

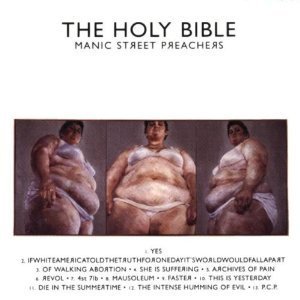

In 2004, Word asked me to write about my memories of Richey Edwards to mark the tenth anniversary reissue of The Holy Bible, for which I chatted amiably on the phone with James and Nicky. I rediscovered this piece – having pretty much forgotten about it – while writing about National Treasures, and since it's not available online, I reprint it here, as it details the occasions on which I crossed paths with the band. (I've edited a bit, as it's quite long.)

Richey James Edwards spent the summer of 1994 at the Priory, Roehampton's psychiatric hospital of choice for the rich and famous. Scaling back his role in Manic Street Preachers while doctors attempted to cure his predilection for self-harm, alcohol abuse and anorexia, he was visited daily by his three bandmates, friends since junior school in Blackwood, South Wales.

They brought artwork to approve and reviews to read, maintaining an important sense of normality at what was, even for this square peg of a band, a pretty fucked-up time. For James Dean Bradfield, singer and gifted tunesmith, there were also guitar lessons to administer. Despite Richey's vital role as co-iconographer and lyricist (with bassist and best friend Nicky Wire), guitar was never his strong point. He looked good wielding one onstage – legendary, in fact – but plugging it into actual amplifiers was not generally encouraged.

So imagine Richey's horror when The Priory's own Norman Stanley Fletcher dropped by. Though the others have reason to believe Richey may have embellished or even invented this story, they want it to be true and so do I. Eric Clapton, an unpaid volunteer within those walls, apparently popped his head round the door and said an old timer's hello to the latest musician on the wing.

"Perhaps I'll bring my guitar round next time?"

Richey was mortified at the prospect of jamming some 12-step blues. "Just what I need," he told James after the visitation. "I'm going to be confronted by God, and God's going to realise that I can't play the guitar."

It's OK to smile. It might help shade in the colouring-book picture of Richey many people still hold in their minds: that of a drawn, troubled, depressed individual, a butterfly broken upon that oft-misquoted wheel. Certainly, Richey was not a happy rock star, fours years into a career that had brought front covers, a fanatical following, Top Ten hits and a unique notoriety. But he was no lobotomised zombie and nor did the band treat him like bone china, even when hospitalised. Despite their outward seriousness and total conviction, the Manics have always used humour as a defence against the world, and Richey was especially funny, by turns amused and amusing, ever conscious of the farcical circles in which he now moved.

His stay at the Priory was punctuated with bright moments and gentle ribbing. How tickled they all were at Richey's indignation when tests on his liver revealed he hadn't been drinking quite as much as he'd claimed. He bemoaned the fact that the staff didn't believe he was mad ("But you're not mad!" James would insist). Richey spoke of "the token gestures of insanity" – hiding in bushes, barking orders – and considered putting an Éclair on his head and "talking to an imaginary giraffe." When building his weight back up from rock bottom (an alarming six stone), the band called him Mr Blobby.

If anything, perhaps Richey's self-awareness, entertaining though it seemed, was his undoing. Was it, in time-honoured rock'n'roll fashion, Too Much Fucking Perspective that sent Richey off into the night?

By the way, I realise I've broken a golden rule of hard-nosed journalism in referring to my subject by first name rather than second, but it seems appropriate in this instance. Not because I'm here to reveal the inner workings of The Richey Only I Knew, simply that he never used his surname, preferring to be credited as Richey or Richey James. Only when he disappeared on Wednesday 1 February 1995 and became the subject of police appeals and national newspaper investigations did his full name seem to become forever formalised.

That was almost ten years ago. So why are we still idolising him, this guitarist who couldn't play the guitar, this lyricist whose lyrics didn't scan, this icon who couldn't hack being an icon? Because the remaining Manic Street Preachers have given us their explicit blessing. Even though they're currently touring brand new mainstream rock album Lifeblood, their fourth as a trio, they are simultaneously reissuing 1994′s The Holy Bible. This was their third and Richey's last extant Manics album. For some fans it remains their finest hour. None of which makes its repackaging an obvious move.

We are talking a digitally remastered 10th anniversary Special Edition, the kind of fanfare and deforestation usually reserved for a conventional Classic Album like Dark Side Of The Moon, Diamond Dogs or London Calling – even Definitely Maybe. But The Holy Bible? A record whose lyric sheet's fourth word is "cunt" and whose tracks includes The Intense Humming Of Evil, Archives Of Pain, Mausoleum and surely the only recorded reference in rock music to serial-killing nurse Beverley Allitt?

Speaking to Nicky Wire it becomes clear that he is the architect of this lavish repackaging, not Sony records. Since Richey's departure, Nicky has willingly allowed domesticity to engulf him, retreating between albums to his house in Blackwood where he watches sport, sees to his baby and takes sellotape to the dog hairs on he and his wife's soft furnishings. A 35-year-old man who makes no secret of a near obsessive-compulsive desire to keep his house in order (his self-mocking t-shirt at the Brits in 1997 read I HEART HOOVERING) he's the natural candidate to, in his own words, "take control of the catalogue."

But this is not just about quality control; the special edition Holy Bible exists as a memorial, albeit one for a man who has never been pronounced dead [NB: Richey was pronounced "presumed dead" in 2008]. Nicky speaks with touching candour when he says, "Sometimes Richey goes off the critical radar and I feel guilty about it. I really do. People need to be reminded how amazingly cool and great he was."

Richey James Edwards: cool and great. It's not a bad epitaph. "There's no way I'd be allowed to be in any other band in the world!" he once told me. James used to describe Nicky and Richey as his two wingers.

For a forensic account of Richey's last days in circulation I refer you to Simon Price's biography Everything. Suffice to say, shaven of head and recently bereaved (his dog, Snoopy, had died at the age of 17 in mid-January 1995), Richey left few clues when he drove the band's silver Vauxhall Cavalier from London to his "yuppie flat" in Cardiff, then parked it at Aust services by the Severn Bridge. Lurid press reports inevitably leapt to the suicide conclusion, wrongheadedly grouping Richey with accidental rock martyrs like Hendrix and Vicious (he would have preferred Curtis and Cobain), but his body has never been washed up and Elvis-like sightings in the years since – including one in Goa – have mostly amounted to wishful thinking.

As Price points out, an estimated 250,000 people go missing each year in the UK, a good 14,000 cases remaining unsolved at any one time. With more of that palliative good Manics humour, Wire described Richey's vanishing act as "more Reginald Perrin than Lord Lucan."

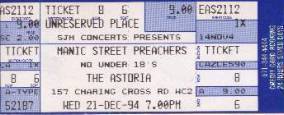

The last time most of us outside of the band's inner circle saw Richey was at the triumphant London Astoria gigs in December 1994. I was there, in the circle, watching the glorious mayhem. Playing the backside out of The Holy Bible, this was a band at the top of their game, the anti-Britpop messiahs, somehow energised in aptly Nietzschean fashion after a European jaunt supporting Suede that had almost killed them. They smashed up their equipment on the last night. An £8,000 orgy they could ill-afford with Priory bills outstanding and diminishing commercial returns, it proved to be their final act as a four-piece. A fitting curtain call from a band who'd arrived on the baggy London scene in 1990 seemingly fully-formed.

They weren't the first rock band with a gang mentality built on childhood friendship and smalltown disaffection, nor the first to stencil slogans on their shirts – indeed, they were precisely the second – but this studied love-hate relationship with rock history was their making. They read the NME from cover to cover, awaiting their moment.

It was all about context; the effects of Ecstasy and Acid House had softened rock music's edges in the latter years of the 80s and a hybrid form we rather quaintly called "indie-dance" held lolloping sway. The Manics existed as a self-styled antidote. For the weekly music press they were a gift. They had a look, a manifesto and gave good quote.

Having had my initial doubts blown away by their first, audacious singles for the Heavenly label in 1991, Motown Junk and You Love Us, I joined the band as an NME writer at the residential Black Barn studios in leafy Ripley in Surrey, where they were locked into the recording of their debut double album for Columbia Records, Generation Terrorists. (The one they'd swaggeringly promised to sell 16 million copies of and split up.) It was here that I first witnessed the unique and efficient division of labour that underpinned the Manics. James and drummer Sean Moore wrote and recorded the music; Nicky and Richey provided the lyrics and decorated the walls of their bedrooms, Joe Orton style, with Edward Munch photocopies and cut-out pictures of Axl Rose, Brigitte Bardot, lipstick and Cherokee Indians.

During a conversation illuminated only by the flickering recording lights of a ghetto blaster playing one of Guns N'Roses' Use Your Illusion albums, I fell under Richey's spell as he demonstrated his innate knack for distilling into a soundbite entire swathes of cultural theory: "We will always hate Slowdive more than we hate Adolf Hitler."

You should have heard the withering contempt in the way he mouthed the words "Loz from Kingmaker" when comparing that year's model of NME indie decency to Vivien Leigh. Meanwhile, out in the converted barn, songs as good as Motorcycle Emptiness and Little Baby Nothing were being committed to tape.

[image error]

Only a band this lovable could get away with a song called You Love Us. They only half-believed they'd sell 16 million albums so when they actually sold 200,000 and stayed together, it was too unwieldy a stick to beat them with. There was little point in accusing them of selling out. I'd tried that at the time of their first, disappointing single for Columbia, Stay Beautiful, produced by Steve Brown (Elton John, Wham!, The Cult). I'm rather ashamed to say that I accused them, in an NME review, of "going soft now that they're firmly positioned upon corporate dick." They didn't hold the sentiment against me. Indeed, Nicky virtually quoted the 13-year-old line back to me when I spoke to him last week.

Perhaps the only disturbing aspect of my trip to Ripley was the sight of Richey's left arm, whose healing scars still read "4 REAL", six months after carving the letters with a blade to make a point to my colleague Steve Lamacq in Norwich. A disturbing display that telegraphed things to come and provided one of the decade's most haunting rock'n'roll images, I vividly remember the hoo-hah in the NME office the next morning when photographer Ed Sirrs first slapped the transparencies on the lightbox. Could we run them in colour? Could we run them on the cover? (We compromised on both counts.) We all worried for Richey from that day on, even those who thought him an idiot. I found that image hard to reconcile with the gentle soul I always met.

The struggle to be taken seriously was collective, but for Richey it had a physical manifestation. The life of a touring rock band is shallow. Most anaesthetise themselves into compliance or pound themselves at the hotel gym, but Richey was too intelligent and too tuned in to ever tune out. He would drink himself to sleep but his mind would be brimming over, fighting against it. He nodded out once while we conducted a late-night interview, Paula Yates style, on his bed at Hook End Manor studios outside Reading in 1993. He was babbling to the end of the Smirnoff bottle:

"Fuck knows, I don't know. It's not the same thing is it? Twelve per cent . . . Steve Lamacq knows what you're talking about . . . You too can lie in a bed like this . . . you too . . . very Morrissey . . . don't hate 'em all . . . bit too reverential about Suede . . . forgive Suede . . . forgive themzzzzzzz."

As James recalls, when they were holed up in London for mixing, rehearsal or promo, woozy with hiraeth (the intense Welsh form of homesickness), Richey would expose himself to the seedier side of life and allow, say, a prostitute he saw at King's Cross to get under his skin. This is a band who became enraged by Ned's Atomic Dustbin, so you can see why a little knowledge of the world might go a long way for a person as sensitive as Richey James.

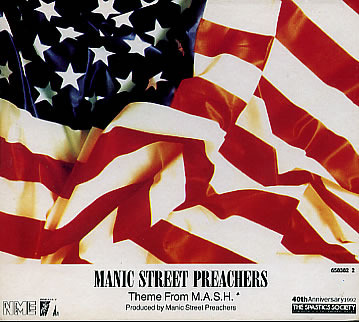

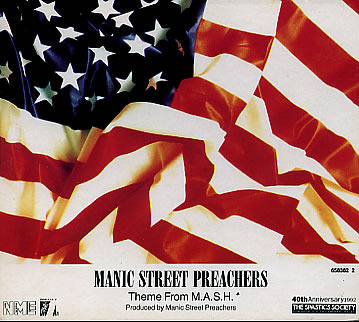

Incidentally, I used the sleeve of the Manics' first top ten hit, Suicide Is Painless, to illustrate this entry, as it formed the basis of a vignette I supplied for the band's website to mark National Treasures' release. This is my truth, many other writers, commentators and musicians have told theirs. They're all here, but this is mine:

I was lucky enough to meet Republican party reptile PJ O'Rourke in September 1992. I had a still-warm CD copy of the Manics' Theme From M*A*S*H in my bag, and asked him to sign it. Across the image of a crumpled stars and stripes, he wrote, "Don't burn this!" I covered his cautionary words with sticky-back cellophane for protection and still have this unique cultural mash-up. Their first top ten hit, recorded for a Spastics Society charity album of number ones the NME had compiled to mark its 40th year, the band unearthed the crunching epic in Johnny Mandel and Mike Altman's Byrdsian lament. (Altman, son of M*A*S*H director Robert, was 14 when he wrote the sappily nihilistic lyric.) It was twinned with an unrecognisable and unplaylisted (Everything I Do) I Do It For You by Irish art-hooligans Fatima Mansions – their only hit, on a technicality ("the only way to win is cheat"). An extra curio: the extra track on the UK CD, Sleeping With The NME, though credited to the Manics, was in fact an extract from a fly-on-the-wall Radio 5 documentary, in which the '4 REAL' aftermath at the NME lightbox was frozen in hysterical aspic. The Theme From M*A*S*H is thus a little piece of history from a prelapsarian age when it was still called the Spastics Society.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers