Andrew Collins's Blog, page 54

June 7, 2011

Hang on a minute, lads, I've got a great idea

For three weeks, we have been All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace, thanks to the empowering genius of BBC2, and to the empowered genius of Adam Curtis. It is easy to call a man a genius, but I think Curtis's track record is now simply too compelling to ignore. I feel fairly sure, looking at his long CV, that the first of his documentary series I saw was Pandora's Box in 1992. I'm going to guess that his "trademark style" was by then in place. If I am wrong, do forgive me. I also feel sure I saw The Mayfair Set in 1999. But it was The Century Of The Self in 2002 (very much a defining commission for the newborn BBC4), about the birth of public relations on the couch of Freud, that really nailed Curtis to the mast and I remember vividly that it had me hooked in from the start. Why was nobody else joining the dots for me this way, I thought. He followed Self with the equally compelling The Power Of Nightmares just a couple of years later. He was spoiling us. He was on a roll. This century, I think, suits him. It gave him 9/11 for a start.

It's rare that a documentary filmmaker carves such a uniquely stylised niche. Plenty of stunning and memorable films have been made that document a certain time or place, or portray a certain group of people in a particularly entertaining or uncomfortable way, but these are usually either fly-on-the-wall or "authored" documentaries, and it's within these parameters that most of our greatest documentarians work their magic; in other words, you either hear the filmmaker's voice or see his/her face, or you don't. Michael Moore and Nick Broomfield are very much part of the narrative of their films; Molly Dineen is sometimes heard, but not seen; as far as I know, Paul Watson keeps out of his films, and Michael Apted was never on camera in Seven Up and subsequent installments.

Adam Curtis is not seen in his astonishing films, but they are his. He narrates them, he authors them, and he originates them, from his brain, and from history, usually 20th Century history. You sometimes hear him off-camera, but these muffled intrusions are not statements, they usually just stand to remind us that Curtis is in the room, and that he likes to edit things together in a rough and ready manner, jump-cutting as if to avoid the artifice of the form. All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace was, to my mind, among his finest and, yes, most graceful works. Perhaps his most audacious? In just three, hour-long films, he managed to link so many disparate and obscure threads your head was spinning throughout. (For the record, he does not deal in gristle: though the tone-setting Pandora's Box ran to six films, Century Of The Self comprised four, and he polished off Nightmares and The Trap in three each.) I really enjoy documentaries on TV, but too often they simply tell a story that's already been told in a slightly different voice, or pick at a scab and hope that bears results. An hour – and I mean a full, BBC hour, not a truncated commercial-TV "hour" with its throw-aheads and recaps – can be a long time when a subject isn't enough to fill it. With Machines Of Loving Grace, you got the feeling that Curtis had timed his stories to the second, so that they built and built, and took in tangents without losing the central thesis, and arrived at their punchline at precisely the right moment. You didn't need to look at the clock while they played out: you could feel the halfway mark, and the ten-minutes-to-go mark. And anyway, who's got time to look at the clock?

If you didn't see them, my best shot at conveying the sheer breadth of material would be to list a few, random markers: Ayn Rand, Joseph Stiglitz, the Federal Reserve, Arthur Tansley, Buckminster Fuller, the Club of Rome, computer utopians, Bill Hamilton, Diane Fossey, Rwandan genocide and copper wire. If some of these names are foreign to you, some of them were to me, too. It's not Curtis's style to run through names that everybody knows, and the final of the three films, my favourite, The Monkey in the Machine and the Machine in the Monkey, was simply mind-blowing in its clear-minded audacity and originality. (I'd heard of almost none of the key players except for Diane Fossey and Richard Dawkins! How thrilling to learn so much.)

Let us simply applaud the BBC for celebrating ideas. Ideas are not always required on the voyage from pitch to programme. A hook is often enough. Or a headline. Or a title. But Adam Curtis trades only in ideas, in connections, in tangents, in profound leaps of intellectual and cultural faith.

I think I love him.

The bomb that will bring us together

Wooooo-ooooo-ooooooh! We're all going to die! Oh, not again! I lived the first 25 years of my life in the shadow of the neutron bomb. I was quite glad when the Cold War ended. And now, according to this dramatic but seemingly sensible new feature-length documentary Countdown To Zero, I'm living in the shadow of either a dirty bomb set off by terrorists, or a neutron bomb that was fired off by accident. It's a compelling film, directed by Lucy Walker and produced by Laurence Bender, which gets a limited cinematic release on June 21 but will presumably turn up on TV or DVD pretty sharpish afterwards. All the details are on the film's official website, but June 21 has been chosen as it's Demand Zero Day, which is basically about reducing the world's nuclear weapons to zero (you can sign a petition, get involved, that sort of thing).

The world certainly looks like a dangerous place in the film. Even though bin Laden's death and the Arab Spring have happened since it was made and altered the landscape for good or ill, the fact remains, there are nuclear weapons everywhere, and nuclear material is sitting around waiting to be turned into weapons: the technology is simple, the will is certainly there among the world's most dispossessed and pissed off, and, as the film shows, detection of this stuff is woefully inadequate. (Bury a piece of uranium inside some cat litter and you can just post it to America, pretty much, and no red lights will go off at any port.)

Unlike a lot of the liberal scare-docs we've seen about ecological armageddon and social ills, Countdown To Zero is not gimmicky. Gary Oldman provides the voice of Robert Oppenheimer at the beginning, but other than that, we are not sold the facts by an august Hollywood star to help the medicine go down. (Much of the narration comes from an interview with Valerie Plame, in fact.) The graphics and animation are minimal and low-key. When a bomb "the size of a tennis ball" is mentioned during the Manhattan Project section, we see a tennis ball in mid-air; likewise when grapefruit are used to demonstrate relative size, we see grapefruits. I'm fine with this. Google Maps are used to show various ripples from imagined nuclear devices dropped in the centres of various big cities. A world map is used to show how many nuclear states there are in the world.

I wasn't sure how useful the endless vox pops were. Asking people in assorted cities how many nukes they think are in the world merely demonstrates that guesses range from low to high. But that's how the "real people" are employed in Countdown To Zero: as guessers. I suppose it shows how ill-informed we all are, but not after seeing this. Take your pick where the nuclear holocaust will come from: Iran, North Korea, Pakistan … apparently Boris Yeltsin averted a Russian-American showdown as recently as 1995 when a non-nuclear rocket was misidentified by the Soviets' radar and he chose to ignore it in that brief window of indecision a world leader gets.

I like a horror film occasionally, and this is one, but Bender and Walker must be applauded for their calm tone (the same production company made An Inconvenient Truth), and for the sheer weight of their interviewees: Gorbachev, McNamara, Musharraf, Carter, de Clerk and even Tony Blair. (How unpleasant to see his face, but hey, well done for stirring up global jihad when you were in office and making the world a less safe place in light of all this, eh?) It's an American film, and has an American bias, but it does not shirk American responsibility – they really did start all this, technologically and politically, and it was their Communist paranoia that fanned the flames of escalation for 40 years. (It's enlightening to remember that de Klerk put a stop to South Africa's nuclear programme in 1990 and opted out of the nuclear club with full disclosure and the handing over of all their working to the AEC. Difficult to swallow down that bile and credit him with anything, but there it is. Mind you, Apartheid South Africa had only developed the weapons programme in the first place due to its increasing isolation in the world.)

I hate nuclear weapons. They ruined what might have been an idyllic childhood, scaring the constant shit out of all of us who saw things like Threads, The Day After, On The Beach, Twilight's Last Gleaming, Dr Strangelove, Fail-Safe, Protect and Survive, or even clips of The War Game. The truth is, no nuke has been fired or dropped in anger since the US killed around 200,000 citizens of Japan in 1945, but during the 1980s, particularly, the hand on the Doomsday Clock ticked ever closer to midnight, and it informed so much of how we thought, what we did, and what the music sounded like. Two Tribes was a number one pop record about America and Russia going to war. A pop record! What are number one pop records about now? Oh yeah, nothing.

Anyway, the good thing about living in London, which I didn't for the early part of my teenage years, is that it would all be over very quickly. Don't have nightmares, but do watch this film if you get the chance on June 21.

June 4, 2011

Hellooooooo, O2 man

The view from Row E, at the O2 Arena, or, as Jerry Seinfeld erroneously called it, "the O2 Center", Friday night. Thanks to Richard Herring (who broke the no-photography rule and took this picture), the nice people who distribute his videos, and his girlfriend, who had a prior engagement, I found myself with this clear view of a stool and a mic stand at 8pm. I was excited. If I had paid £100, as many of the 14,000 people in the big barn had, it's possible I would have been even more excited. (I'm not sure I'd pay £100 to see anybody, whether stand-up or band. Isn't there a recession on?)

Seinfeld hadn't played in London since 1998. There's a chance he won't be back any time soon. So it was a golden opportunity to catch him. It's been over ten years since Seinfeld ended and we were all deprived of his big teeth, Brooklyn drawl and constant failure to actually act, although the box sets do provide eternal comfort in a Godless universe. (I actually love all seven seasons. All of them. Pick any episode you like, from any season, and I will like it. I used to hate the slap bass when it started, but I got over that. The rewards are too great to get hung up on an annoying musical sting.)

Anyway, this wasn't about Seinfeld, it was about Seinfeld. Would he cut it as a stand-up, on his own, standing up? Yes is the non-surprise answer. He's 57, he's been standing up and observing life since 1976, keen to get back into the comedy clubs once the sitcom ended in 1998 and clearly more at home behind the mic than in front of cameras. Richard and I were very lucky to be in Row E – this is, I think, the closest to the stage I've ever been in an arena or stadium, not including the times I've been in the moshpit, or side-of-stage, as a journalist. As I noted when we sat down, if Row E had been the back row, it was like seeing Seinfeld in a small club. There just happened to be thousands of other people behind us. Way behind us. I've only ever seen Al Murray at the O2, and he filled it by being larger than life – and having giant beer pumps behind him. Seinfeld moved from left to right, but what you got for your £100 was a man standing in front of some curtains, talking, for around an hour and 40 minutes, non-stop. (Jerry was supported, fairly pointlessly, by his old friend and current Vegas resident George Wallace, whose catchphrase "People say some stupid stuff/shit" was repeated so often it was clearly a device to stall while he recalled the next joke.)

I'm not going to repeat any of Seinfeld's gags, suffice to say, this was all observational stuff, as we've come to expect from the stand-up that used to bookend his sitcom. Much of it is sharp as a tack, some of it is unoriginal in subject but marginally more original in execution, and all of it is delivered in such an assured and economical manner, you can't fail to have a good time. I laughed a lot. Many people around us didn't laugh at all, especially – if I may generalise – the women, but smiled instead. On one or two golden occasions, a spontaneous arena-ful of appreciative applause broke out. Nobody whooped. I was glad about that. It's great to see a stand-up on top of his game, albeit reciting very old material in places, and you've got to hand it to a man almost in his sixties for doing so much material about technology without simply denigrating it from an old man's Luddite perspective – he's a modern man; he does not necessarily mock the BlackBerry, he mocks the type of person that uses one. He does not pretend to not know how email works, he merely bemoans the fact that it is not delivered once a day like mail used to be, but all day long. Even the material on marriage and fatherhood seems fresh, because, as he makes clear, he's a late adopter to these two institutions, having married at 45.

Thanks to the above laminated guest pass – something neither of us expected when we picked up our comp tickets – Richard and I had access to the inner sanctum backstage. (It's called the Sky Bar, as it's sponsored by Sky.) When Al played, the outer sanctum was the inner sanctum – it's where Al was – but this time, an inner sanctum was created so that Jerry didn't have to mix too heavily with the assembled freeloaders, just the higher echelon of freeloaders. I don't know why this included us, and once we'd dared to enter the inner sanctum, it was pretty much empty. We were happy to have bumped into Simon Amstell and Richard Bacon outside while we tried to actually find the lift that took you to the Sky Bar, but that – or so it seemed – was the full compliment of celebs. Then Clive Anderson turned up, which was nice. We were happy enough with the turnout at this point, and the beer was free (if still served in plastic bottles, even in the inner sanctum). Then, as if by magic, all the real comedy celebs appeared – it seems that they had been watching the show from some exclusive box or something, not from the scummy rows of seats where Rich and I had been. But they were welcome to it. I loved it in Row E.

Anyway, within minutes, we were in the rarefied proximity of Ricky Gervais, Stephen Merchant, Angus Deayton, Lise Mayer, Harry Hill, Lee Mack, Chris Evans, George Wallace and … Seinfeld himself. No, we didn't speak to him, but we spoke to Ricky and Steve, and they'd spoken to him. (The famous comedian Omid Djalili had been sitting next to us in Row E, but he chose not to go to the after-show.) I found myself having an impromptu script meeting with a TV exec who has commissioned a group-written sitcom I'm working on (can't say any more), which was not really what I expected to be doing at the Seinfeld after-show, but I suppose was poetic enough in its own way. At least I was talking about comedy. I have only met Ricky Gervais a couple of times in my life, but he is always gracious enough to say hello to me when someone that famous could easily just blank me, and I appreciate that. He is a just a bloke, after all. (He's arguably as famous as Seinfeld. Think about that.) There was a man in the inner sanctum who seemed to be bothering all the celebs with what might well have been requests for his entirely worthy charity, but he had crossed the line I feel, and had become a pest. (He had swapped glasses with Chris Evans seconds after Chris's arrival, and Chris was totally patient with him, but I found it very uncomfortable. I am as guilty of anyone of gushing to people I admire – you know that – but this man, a serial botherer, seemed to actually be driving people away. I guess you'd have to call it liberal interventionism.

Richard and I left around midnight, having at least breathed in air that Jerry Seinfeld had exhaled, and presumably added to the air that he was breathing with our own exhalations, and missed the last Tube home, so we had to share a cab to his house and pay through the nose for it. The "O2 Center" is a very good venue, well signposted, helpful staff, but it is a long way away from civilisation.

Please let me be about the telly

Saturday mornings are now taking shape along these lines – and as anyone self-employed will tell you, it's sometimes nice to have shape forced upon an amorphous working week – alarm at 5.50am, BBC car at 6.20am, arrive at Radio 2 approx 6.50am, make cup of horrible machine coffee for me and cup of horrible machine tea for the delightful Zoe Ball, who has been broadcasting since 6am, enter studio, provide fizzy, lighthearted review of the week's smaller news stories in two chunks between 7am and 7.30am and give Zoe someone to bounce off. Empty pigeonhole at 6 Music (which is one floor below Radio 2), leave BBC at 7.35am and go home, via public transport, in time for breakfast. On train home, post blog entry about Guardian TV Review Thing, which is written and clip-harvested on a Thursday, filmed on a Friday, and posted on the Guardian website at midnight, ready for viewing on Saturday morning.

Saturday mornings are now taking shape along these lines – and as anyone self-employed will tell you, it's sometimes nice to have shape forced upon an amorphous working week – alarm at 5.50am, BBC car at 6.20am, arrive at Radio 2 approx 6.50am, make cup of horrible machine coffee for me and cup of horrible machine tea for the delightful Zoe Ball, who has been broadcasting since 6am, enter studio, provide fizzy, lighthearted review of the week's smaller news stories in two chunks between 7am and 7.30am and give Zoe someone to bounce off. Empty pigeonhole at 6 Music (which is one floor below Radio 2), leave BBC at 7.35am and go home, via public transport, in time for breakfast. On train home, post blog entry about Guardian TV Review Thing, which is written and clip-harvested on a Thursday, filmed on a Friday, and posted on the Guardian website at midnight, ready for viewing on Saturday morning.

So here I am. This week, Telly Addict (I'm so pleased we called it that) covers Britain's Got Talent (ITV1), Horrible Histories (CBBC) and Four Rooms (C4), and I am wearing a green, stripy top. I hope you like it. I'm having breakfast.

May 31, 2011

Please let me be on the telly

While my current TV career amounts to occasional repeats of clips shows, whereupon people will usually tell me I'm on via Twitter and exclaim that my hair looks either nice or not as nice, and from that I'll try and work out whether the show was filmed in 2002 or 2005, my Dad has been on BBC2 and BBCHD. He went to Wentworth, the famous golf course, on Friday, to see some of the PGA Championship with his friend Ken – he and my Mum are golf mad, by the way – and in tribute to Seve Ballesteroes, who sadly died in May aged just 54, many of the players and spectators dressed in Seve's trademark outfit, of navy jumper, navy trousers and white polo shirt. It looks from the BBC report to be a very sober but moving memorial, out there on the golf course, where Seve won over millions of fans. I am proud that my Dad was interviewed and that the interview was used on the BBC. He is cool. He was on Telly Addicts. (He and Mum were on Sky Sports, too, also talking about golf.) If you want to hear my Dad's brief contribution, and see the full, two-minute film, it's on the BBC Sport website, and Dad starts speaking at 01.11. I think there's a joke about a golf link in there somewhere.

Apple: machines of self-loving grace

I am in an abusive relationship. That's right. I am an Apple Mac user. I have been ever since computers were invented. Alright, ever since I first played with a computer, which was at the beginning of the 1990s. IPC Magazines, for whom I worked at the time, were about to "go computerised." The NME might have been an outpost of revolutionary thought and rock'n'roll devilry, but we also had to get a newspaper out on a weekly basis (and always did, even when we all went on strike), and when I arrived at the paper in 1988, it was all done by hand.

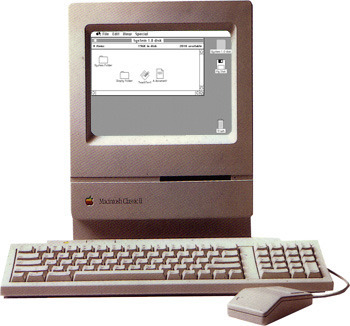

I enjoy playing the "it was all fields" card and telling young people that I worked on a newspaper pre-computers. Some of the nerdier kids at school must have had Sinclair or BBC computers, but no-one in my immediate social circles did. Our family had the Pong game console for our telly, although we only rented it, and Dad took it back because the shop couldn't initially supply the gun for the shooting game, and while we waited for it, we got bored with the tennis and squash games, so he got his money back. The first computer I ever "played on" was the Apple Mac Classic II in 1990, the year IPC started to move from cut-and-paste layout to desktop publishing. (Vox, which launched in October 1990, was IPC's first fully desktop-published magazine, I believe I am right in saying. I worked on it, and typed in my first ever copy to a computer.)

If I may just reminisce about the Old Days for a moment: when I started work on the NME in 1988 the layout room was just that: drawing boards mounted on desks where grids were laid out with photocopies of photos and Letraset-created headlines once they had been "sized up" to fit. The copy – calculated into lengths from the word-count – was "flowed in", which meant drawing a line in pencil to indicate where it would sit, once typeset. The Even Older Days of "hot metal" printing were behind us, and this is how the copy was typeset: the typewritten pages, marked up by the sub-editors in red pen, were sent to the typesetters, via courier, where the words would be "input" into … yes, a computer! So the company that had a computer could charge us to use it, basically. You can see why a large corporation might think that this had to change once smaller, more affordable desktop PCs came in.

So, in one of the very few examples of actual training I have ever had in my stupid, ramshackle career, I was taught how to use a Mac. Apple colonised the publishing industry pretty categorically. The first computer I used was a Mac, and so I became a Mac user. This was not a qualitative decision, nor an aesthetic one, and certainly not a lifestyle choice, as it may have been for other people. As a freelance journalist, you'd be insane to buy a PC and risk hitting incompatibility problems with your employers. So Macs proliferated through the print media. (The BBC used PCs, and still do. I vividly remember seeing email for the first time in around 1992 when I started broadcasting on Radio 5; our producer, John Yorke, sent a message from his PC to another BBC employee. It was magic. Although his PC had a blue screen and the words came out in white, which looked pretty knackered to my Mac-trained eyes.)

I must have taken the plunge and purchased my own Mac Classic II in 1992, as that's the date on the oldest Word document in my existing archive: some Collins & Maconie sketches for Mark Goodier's Radio 1 programme. I think I replaced it with a much heftier Apple Performa in 1994. This was the computer that had a modem, although I could never get it to work and it didn't matter that much. If I wrote anything at home, I just copied it to a floppy disk and took that with me to whichever office required it. I didn't know that many people with an email address, and I know for a fact that I wrote my first book, Still Suitable For Miners, without access to the Internet, or email, in 1997. (I interviewed Neil Kinnock for that book by fax to his office in Brussels; and when I wished to look at Billy Bragg's messageboards on his website, I had to look at them on his PA's, in her kitchen, and print them off.)

The Performa lasted for a few years. I have fond memories of it, as it felt very professional through its sheer bulk, and I taught myself to touch-type on it, using the Mavis Beacon programme that came with it. I will always be grateful to Mavis.

Stuart, who was much cleverer on computers than me, showed me the Internet, on his Mac at home. I couldn't believe how long it took for an image to appear, but was moderately impressed. When I was the editor of Q, I experimented with the Internet at the office, but it was pretty lawless and uncoordinated in the mid-90s, and slow, of course. At Emap, which published Q, an "online" department was established on a lower floor, and lots of young people in glasses started appearing. Some of the magazines launched websites, and they were rubbish, but we felt we ought to. It's amazing to think how new all this was as recently as 1996.

I found a computer engineer in South London who was prepared to do home visits and understood Macs and he made my modem work in about 1998. At the same time, he sold me a reconditioned iMac in a part-exchange deal, which was excellent value for money, and anyway, the iMac struck me as a lovely thing. Around this time, although being a Mac user was like being a second-class citizen in the world, I began to fully appreciate how easy on the eye the Mac interface was, and how nice the machines looked on the outside. And the iMac was so portable and user-friendly, I think I entered my first wave of if not evangelism, certainly preference. With the blooming of email, you didn't need disks, and compatibility problems were becoming a thing of the past. If I'd wanted to switch to a PC, and enter a world where more computer engineers actually knew how to fix your computer, now was the time. (I seem to remember this new thing called live streaming was unfriendly to Macs initially too.) I declined to swap brands.

I liked the iMac. The modem worked from day one. And it had a handle on top, which was useful now I was 100% freelance and my home was my office, or a rented office was now my office. Moving house or office was much less hassle with the iMac. I switched from the iMac to a Mac PowerBook in around 2004, as I was doing more scriptwriting and wanted the freedom to write wherever I found myself collaborating and had moved out of London.

Stuart had impressed me with his Sony VAIO laptop and I was tempted. But something conservative within me kept me on the Apple path. It's a strange thing. Apples and PCs look exactly the same. I use a PC at the BBC when I'm at 6 Music, and I used one to write Grass on with Simon Day, as we either wrote in BBC writing sheds, or at my agent's office, which had PCs. Lee Mack and I wrote the first series of Not Going Out on PCs, as that's what Avalon had installed in our rented office. Meanwhile, at Radio Times, which is part of the BBC but is a magazine, it's Apple all the way.

What I'm saying is: I use Mac and PCs in a normal working week. But I prefer using Macs. I hate the way you have to scroll up from the bottom on the PC. I miss the sweet little icons when I'm not on a Mac. I would not get into an argument, much less a fight, about which is better. As you can see, I started out as a Mac user by necessity, not design. And when I was at Q, I fell in love with the intuitive nature of Macs in terms of graphics and text. And yet … I have an LG phone whose camera will only upload to a PC. Little niggles persist.

And the goth-black MacBook, which I bought with the insurance money after my PowerBook was destroyed in a flood at the office I rented in July 2007, should by rights still be in service. It's only four years old. But I've been forced to upgrade. Built-in obsolescence is an age-old trick of the electronics and white goods industries, but the speed at which stuff needs replacing now is criminal. And the computer market is the most brazen of all. I hate it.

The old MacBook, which I did actually love, saw me through quite a bit of thick and thin. It almost became famous, as it was the laptop Richard and I used to record our podcasts on – and indeed, it was GarageBand, bundled in, that first enabled us to even consider the idea of starting a podcast back in 2008, after I'd seen it in action at Word magazine. That MacBook was seen, live, onstage, by hundreds of people. But, as regular listeners to the podcast will know, it rejected the £50 home studio Richard bought it for Christmas, no matter how hard we tried to get the two machines to mate. And last year, in Edinburgh, GarageBand finally ate an entire podcast – the infamous Podcast 123 – something that had been brewing for a while, as GarageBand would often freeze after recordings in the attic. (Here's a phrase to strike fear into the hearts of Mac users: "Application not responding" … Force quit!)

Also, having taken my MacBook to the, ahem, Genius Bar, at the Apple Store in Central London's Regent Street once already when the mousepad packed up due to the also-famous collapsing casing issue in January 2009, it had subsequently started to go again. If Apple are so clever, and they are always telling us how clever they are, why did they make a laptop whose casing would crack and cave in under the weight of two wrists? They call it a "known issue" as as such, will repair your casing, by replacing it, as I discovered. But the Apple shop is not a place I like to visit. It's too friendly and clean and it feels a bit like you are joining a cult just by entering it. The staff are evangelists, and well-trained, and I hope they are well paid, because they are a bit like "greeters" who also know everything about the stock they sell. I bought my second, replacement laptop in PC World, where, at the time, I congratulated myself for only having about two laptops to choose from in the Mac section, whereas PC users had loads to choose from! But I also discovered that PC World's competitive insurance policy only applied, at that time, to PCs, and not to Macs, which they also sold. In order to have my flooded MacBook looked at, I had to drive to the arse-end of an industrial estate to find some people who could help me. Apple Stores are all very well if you live, or work, near one, but there are only 28 in the whole of the UK, so good luck if you don't live near a big city.

So, I have a shiny new MacBook Pro, and I am using it today for the very first time. It is faster than the old MacBook, and that's about it. I really only wanted a like for like replacement, not an upgrade, but since my old one was showing all the signs of packing up under the weight of more than a couple of programmes running at the same time, and had begun to crash on a near-daily basis, especially if I had the audacity to plug a dongle into it, I felt I should play it safe. After all, this laptop is my office. It is my business. When I'm not talking on the radio, all the work I do must travel through this machine of loving grace. Naturally, transferring all my business from MacBook one to MacBook two should have been a breeze. It hasn't been. Tell me all about Migration Assistant and Time Machine, but you'll need to buy a lead to do all that. I object to all the extra things Apple make me pay for in order to be a Mac user, especially one who had already paid for the Mac itself. The new MacBook has a new FireWire socket. This means I need a new lead to connect it to my old Mac. Brilliant.

I have now pretty much transferred everything over using a portable hard drive which I bought a few years ago. I did it piecemeal really, and wouldn't have been able to without the many Mac forums I looked up, or without the assistance of the friendly nerds who follow me on Twitter. (You know who you are.) I went to plug my iPod into my new MacBook this morning for its first charge and, ha ha, the lead had an old FireWire socket on one end. If Apple are going to keep changing things, they should let us have the new leads for free. I think, at the end of the day, I like using Apple products, I just don't like owning them. And I don't like the way Apple treats its disciples. It expects them to jump up and down and whoop and pay top dollar for every new shiny Apple thing it puts onto the market, and then it will release a new, improved version, that's cheaper, about six months later, as a punishment for those early adopters who work so tirelessly on the corporation's behalf, singing its praises and demonstrating the iPad and the iPhone by waving them around on trains.

My iPod is second generation. It had a black-and-white screen and does not play videos. It is also very big and heavy. I had to get the battery replaced a few years into its life, and I resented that, but I am determined not to replace it. Maybe it will come back into fashion. I do not have an iPad, and nor will I buy an iPad. The iPad is a racket. I will not buy a MacBook Air, as sleek and light as it is, because it doesn't have a CD drive, and I need one of those, and I'm not buying an external one. I do not have an iPhone. If I did, I would be able to sync it with my MacBook, but a belligerent part of me does not want to give Steve Jobs the satisfaction.

Richard Herring's house is like an Apple Store where nothing is for sale. He is Steve Jobs' wet dream. Or is he? He hates Apple, too. Many of us do. If you are a PC user, do not look patronisingly down upon us. We are caught in a web. And Apples do look nicer. You must admit. And that's what counts, in the end.

May 28, 2011

Party trick

Telly Addict number four is up. This week, on what they're all calling the Guardian TV Thing, I review MTV's Geordie Shore – Hooray! More "structured reality"! – BBC2′s All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace, ITV1′s Prince Philip at 90, and a quick recap of who lost the TV Baftas. I still can't embed it, but you can watch it here.

May 27, 2011

Storm in a teacup

Here's something I need to put out there. I reviewed the film An Education in the Radio Times because it was on the telly. This is what I wrote (you can skip to end of the penultimate paragraph):

An Education

Fleet Street grande dame Lynn Barber first wrote about her experiences as a 16-year-old schoolgirl whose dreams of applying to Oxford in 1961 were sidetracked by an older man in Granta magazine. It grew into a book and, thanks to the screenwriting skills of novelist Nick Hornby, a film, which gives a new spin to the apparently swinging 60s we usually see on screen.

Barber-surrogate Jenny (Carey Mulligan) lives with her parents in old-fashioned, curtain-twitching suburban Twickenham, so when she meets metropolitan charmer David Goldman (Peter Sarsgaard with a passable English accent) and he whisks her off to London's West End for cocktails and foreign films, she is besotted. Her parents – a scene-stealing Alfred Molina, and Cara Seymour – take more convincing, as does her starchy headmistress Emma Thompson.

This will chime with anyone who was told by their parents that they were throwing their life away, which is why An Education works as more than just a nostalgia-inducing period piece.

With a fine supporting cast including Dominic Cooper, Olivia Williams and Rosamund Pike, Danish director Lone Sherfig (Italian For Beginners) makes convincing work of recreating English life as it was lived then – apart from one glaringly erroneous single teabag dunked into a mug. (In 1961?)

Carey Mulligan is the chief revelation, though – 23 at the time, she brings incredible depth and subtlety to Jenny's flowering, which does not run smoothly. AC

Not exactly a controversial review. However, it led to a subsequent letter being published in the magazine – from none other than restaurant critic Jay Rayner! He challenged my knowledge of teabags! With lighthearted affection I like to imagine, he pulled me up on my assertion that it's unlikely someone would have dunked an individual teabag into a mug in 1961, when the film is specifically set.

Well, let me back this assertion up. According the the UK Tea Council website and its excellent history of the teabag, yes, teabags were introduced onto the market before the war in this country – having been "invented" in America in 1908, when samples of tea were sent out in small silken bags by merchant Thomas Sullivan (although infusers go back centuries) – but the British public didn't take to them as readily as the Americans had. Even after the war, Brits remained skeptical and stuck to loose-leaf tea, infused in a teapot and poured through a strainer.

I grew up in the late 60s and early 70s and this is how I remember all tea being made. We didn't even have mugs. Teabags may well have existed, but none ever crossed the threshold of my house, or the houses of my family and friends. A good decade after the year An Education is set, and the teabag was still a foreign object. Now, the book and film are set in suburban London, and we were in provincial Northampton, so I accept that Metropolitan types may have adopted the bag before we bumpkins did. That said, the character who dunks one in An Education is Olivia Williams' kindly schoolteacher (she makes a mug for herself and one for Carey Mulligan's heartbroken teen in her modest flat). She is not some early-adopting trendsetter or radical. Nor rich. And teabags seemed like a pretty fancy way of delivering tea, even in the 70s. They must have been more expensive per cup, as they were sold on convenience, not price.

This is why I am sticking to my anecdotal certainty that a schoolteacher would have possessed neither the money nor the adventurousness to buy individual teabags to dunk in mugs in 1961. Even in Twickenham. Even though Tetley had launched their teabag in 1953, by the early 60s, according to the UK Tea Council, bags made up only 3% of the British tea market. Of course it is physically possible for a teacher to be part of that 3% in 1961, but, I would argue, still unlikely. And not normal. If one of Mulligan's trendy London friends had whipped one out, I'd have bought it as a cultural signifier. But I'm going out on a limb here and I'm saying that the two dunked teagbags – that's individually dunked, not dropped into a teapot – are an anomaly.

But I need backup. Anybody old enough to remember 1961? Did you ever see anyone dunk a teabag? I am prepared to let Jay Rayner win. He's a nice guy, and I respect his restaurant reviews, and he was brought up in London, not the Midlands. But he wasn't born in 1961 (he's 44) and I have a hunch that he's wrong. What do you think?

May 25, 2011

Five Angry Men and One Woman

Well, not angry, exactly, but animated and exercised and passionate about whether the music from You Only Live Twice is better than the music from Goldfinger or not. (It is.) On Friday March 18, I was invited by BBC Radio 5 Live to join a jury charged with selecting the Top 10 instrumental film scores of all time for a forthcoming concert by the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, whose running order would be based upon our hard-fought selection. It's all part of BBC Philharmonic Presents … a week of concerts themed around the proclivities of various BBC radio networks [find out all about it here]. 5 Live's was chosen to be film-themed, and goes out live in two Fridays' time, June 10, from 2pm, curated and presented by its cult film-reviewing/bickering duo Simon Mayo and Mark Kermode, whose "Wittertainment" initiative has defied nature and survived Simon's move to Radio 2 (it remained in place on a Friday afternoon on 5 Live, which shows just how valued it is by the Beeb). The idea of these concerts is to officially launch the BBC's new Salford Quays home, MediaCityUK, which has a venue built in. I wish I was going up to Manchester for the gig, but I am too busy. Should be a fine afternoon's "instrutainment". Tune in.

You can see us all gathered around the warm glow of a green studio light that bright Friday afternoon, a jury of six charged with the ludicrous task of stacking up a dozen great orchestral film scores. From left, then: Mark Kermode, the good doctor, linchpin of the Corporation's film coverage and – as luck would have it – a skiffle musician in his own right; chairman, the genial Simon Mayo, and Mark's unofficial handler; the Philharmonic's General Manager Richard Wigley (who'd just flown back, with the band, from Japan, when the earthquake hit – if you want airlifting out of a stricken country, be connected to the BBC!); eminent and garrulous American conductor Robert Ziegler, who actually conducted one of our shortlist, and about which he was extremely humble and gracious, There Will Be Blood; colourful, platinum-selling pop singer and actress Paloma Faith, the only jury member to dress up and wear a massive hat for the occasion as if it was on TV (unless she always looks like that, or was on her way somewhere else); and me. I had my laptop out because I'd forgotten to print off my own personal shortlist.

We all brought in a personal wish-list, as instructed, and to kick things off Simon asked us all to read them out. I went first, and as I remember just kind of rattled them off. Paloma went second, and opted instead to make a passionate case for each one of her choices. Because she is a singer, and had been part of a previous concert of film music, conducted by Mr Ziegler, most of her choices had been influenced by that experience. We discussed them all. (The whole judging process has been made available as a podcast by 5 Live, which is nice. If you really want to hear it, it's here. I have yet to listen back to it, so maybe it's not as tense and fraught as some of it felt on the day. I sincerely hope you can hear Paloma eating her ambient BBC canteen salad.) I enjoyed Robert Ziegler's propensity for singing the themes when they came up – I seem to recall a spirited dum-de-duh-dum-dum-ing of Bernstein's The Magnificent Seven – again, I may be misremembering. Mark kept his powder dry and was the last to pitch in with his own personal favourites, most of which were on the obscure side and many of the other jurors weren't familiar with them. That's the way – uh-huh – he likes it. (The production staff on the other side of the glass were heroic on the day: the session was taped, as live, over an hour, and they managed to rustle up clips to play through our headphones almost as soon as they were mentioned. Even some of Mark's. Top work.)

The final shortlist of 11 (don't ask) – heavily influenced, it must be said, by Richard Wigley's valuable input on the sheer practicality/impracticality of an orchestra actually playing the extracts on the night/afternoon, and by our collective aim of not putting any composer in twice (except for John Barry, because we couldn't help it!) – included Raiders Of The Lost Ark, You Only Live Twice, Blue Velvet (or at least a specific song by Angelo Badalamenti from it, Mysteries Of Love), Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Taxi Driver, The Mission (specifically Gabriel's Oboe), The Godfather (one of my picks, although not exactly difficult to pitch), The Magnificent Seven, Midnight Cowboy, There Will Be Blood, and last but not least, 2046, which Paloma championed from the start as her absolute, foot-stamping must-have, a score from a still fairly obscure Wong Kar-Wai sci-fi love story by Shigeru Umebayashi, who, if he knows he made the shortlist, would be pretty surprised, I should imagine.

You've got to love Dr Kermode – the case he made for Badalamenti, whose most famous score, after all, is for a TV series, was so feverish, the whole room went away convinced he is as vital a film composer as Bernard Herrmann or John Williams or John Barry. (Mark looked like he might commit suicide if we didn't allow the theme from Firewalk With Me, which hardly anybody was familiar with, but we didn't, and he was talked down off the roof in order to accept Blue Velvet.) I also like the idea that Mark was egged on to volunteer to play the harmonica with the orchestra for Midnight Cowboy. "Oh, go on, then …"

A funny, odd and mostly enjoyable way to spend an hour, and democracy in action. Hey, it's the only way I'm going to get back into that 5 Live studio on a Friday afternoon.

Photos by Jane Long.

May 24, 2011

The wrong man

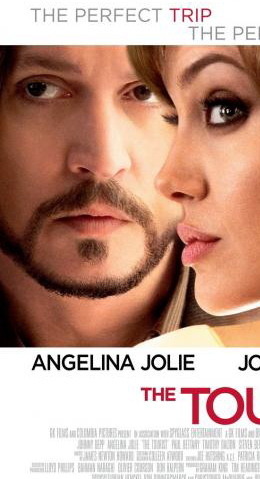

This is a partial image of the poster for The Tourist. Because I only partially saw The Tourist. I had fully intended to watch it all, on DVD. But it was awful. So I turned it off and stopped watching it. The context: it is the second film from writer-director Florian Henckel von Donnesmarck, the apparent genius behind one of the finest films of 2006, the Oscar-winning The Lives Of Others. I met and interviewed this giant of a man at the time for Radio 4, and came away suitably impressed. I'd loved his first feature, and, fluent in five languages and an actual, leonine German nobleman, he seemed to be a superstar in the making.

Having spent three years making The Lives Of Others, Henckel von Donnesmarck understandably fancied a break from the doom and gloom of the East German secret police and their pinched-faced surveillance culture, so he decided to make an old-fashioned, 60s-style spy caper, the kind which might once have starred Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn, but in 2011 can only star Johnny Depp and Angelina Jolie. Set in Venice, revolving around a case of mistaken identity and with an early scene of two strangers meeting on a train, it would be a shamelessly Hitchcockian travelogue thriller romp. I was intrigued. I don't much like Angelina Jolie onscreen, but I have an awful lot of time for Johnny Depp, an offbeat, intelligent actor and the only person I ever interviewed who smoked all the way through it. (This was pre-smoking ban, but nonetheless rare in mixed, professional company and among straight-edge, pleasure-averse Hollywood royalty.)

So, we sat down to watch it. And lasted about half an hour.

Because The Tourist had endured some horrible reviews, we had low expectations but went in with an open mind. And, ironically, it wasn't as bad as you might expect. Certainly not as bad as Eat, Pray, Love. Jolie was poised and pert and old-fashioned (it's set in contemporary times, by the way, but harks back to cigarette-holder 50s and 60s glamour and really ought to have been honest and set in the 50s or 60s), and her English accent was fine; Paul Bettany seemed a good fit for the harassed detective trying to catch a criminal; further British casting added Rufus Sewell, a revived Timothy Dalton and Steven Berkhoff to the list of potential attractions; and Johnny Depp … well, he'd be Johnny Depp, right?

Wrong. Depp, looking uncharacteristically puffy and unhappy, was actually the weak link. Miscast and possibly misdirected, I know he was supposed to be a crumpled "math" teacher dragged into an international manhunt because he's the same height as the real criminal, but "everyman" is not his strongest suit. His actual suit looked wrong, too. He didn't seem to know if this was a comedy or a thriller, and nor did the rest of us. Jolie's character leads Depp to believe she's seducing him, when in fact she's using him, and they fetch up at the poshest hotel in Europe, and then Berkhoff's gangsters turn up and suddenly there's running in pyjamas over rooftops, and …

OFF

That was enough of that. Life is way too short to watch films that you don't really want to watch. I hadn't read much about The Tourist's genesis, but, the statutory lazy remake of a recent French film, it seems that it had been passed like a parcel from director to director, and from actor to actor (it could have been Charlize Theron, who I'd have preferred, acting against Tom Cruise, or Sam Worthington, either of whom I'd also have preferred), and when Henckel von Donnesmarck signed back on for the second time, he apparently rewrote it in two weeks and knocked it off in two months.

Maybe it got better in minute 31 and thereafter. I'm afraid I didn't stick around to find out. I'm sure the German nobleman will live to make another great film. The Tourist defied the critics and took $277 million worldwide. The people have spoken. The people were obviously not as disturbed by Johnny Depp as I was.

Good to try stuff out, though. It takes all sorts. Sniiiiiiiiiiiip!

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers