Marc Lynch's Blog, page 101

March 12, 2013

Closing windows for peace on the brink

Is the window closing on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process? Probably. But in case you were wondering, you're not alone. A Google search on "window closing peace Israel" produces 17.5 million hits. The window for this metaphor might not have closed, but it's on the brink like Jordan (5.8 million hits).

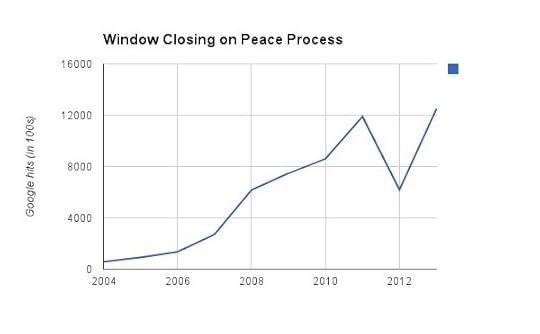

How on the brink is the closing window of the peace process? Well, check out this chart of Google hits by year:

The window was only closing on the peace process 57,000 times in 2004, but by 2007 271,000 creative souls were closing the curtains. 617,000 hits the next year, and then the remarkably resilient window broke the 1 million mark for the first time in 2011. But then a puzzling fall in 2012 to a mere 620,000 pages mentioning a closing window for the peace process clearly presented an irresistably open window and headline writers leapt through: In only two and a half months of 2013 we've already got 1.27 million references!

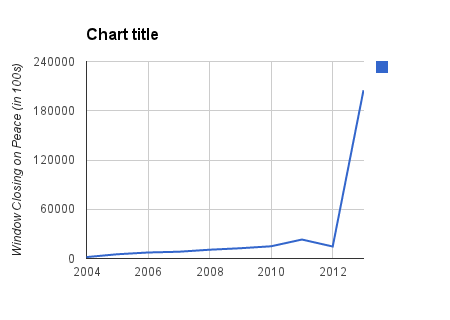

But maybe it's only the peace process that's suffering from this epidemic of closing windows, rather than peace itself? Alas. Searching instead on "window closing peace Israel" -- without the process -- produces this:

Yikes! 20.5 million hits in just over two months (and yes, that's more than the 17.5 million total from the "any time" search -- welcome to Google Math.) Take out that spike, and the second chart looks a lot like the first -- steadily rising use of the window metaphor over a decade followed by an unexplained drop in 2012 and then a big jump this year. What does that mean in the real world? Nothing much, other than that the window for peace is probably closing but the window for window closing metaphors never will. Anyway, this is more fun than grading papers.

OK, editors, this one's free: Once again the peace process is on the brink of a closing window because of a shameful failure of bold leadership. Will the world's headline writers muddle through? Only time will tell.

March 11, 2013

Silent on Saudi Arabia

Two of Saudi Arabia's most prominent human rights activists,

Mohammed Fahd al-Qahtani and Abdullah al-Hamed, were sentenced over the weekend

to lengthy jail terms. As Ahmed al-Omran reports

today for the Middle East Channel, the sentences were not a surprise (when I met him in January, Qahtani told me that they were inevitable), but the

optics for American foreign policy are frankly appalling. Their sentencing was

sandwiched between John Kerry's first visit to Riyadh as secretary of state and

a visit by Attorney General Eric Holder. Neither appears to have publicly said anything whatsoever about this

case nor about any of the massive human rights and democracy issues in Saudi

Arabia, Bahrain, or the rest of the GCC.

Quite the contrary. Instead, both Kerry and Holder waxed

rhapsodic about U.S.-Saudi cooperation on strategic issues and went out of

their way to praise the kingdom's appointment of thirty women to its unelected

Shura Council. Holder was quoted

across the Arab press as praising

the Saudi Interior Ministry's counter-extremism efforts and the Kingdom's

reforms. In Kerry's March 4 press

conference with Saudi Foreign Minister Saud al-Faisal, he had this to say:

"Across the Arab world, men and women have spoken out

demanding their universal rights and greater opportunity. Some governments have

responded with willingness to reform. Others, as in Syria, have responded with

violence. So I want to recognize the Saudi Government for appointing 30 women

to the Shura Council and promoting greater economic opportunity for women.

Again, we talked about the number of women entering the workforce and the

transition that is taking place in the Kingdom. We encourage further inclusive

reforms to ensure that all citizens of the Kingdom ultimately enjoy their basic

rights and their freedoms."

In other words, he places the kingdom within the ranks of

the regimes who have "responded with a willingness to reform." In a meeting with embassy staff, Kerry was even more effusive. On nearly every issue which

concerns the United States, he said, "Saudi Arabia has stepped up and

helped." (For those keeping score,

those issues were the sanctions on Iran, arms to Syria, Yemen, counterterrorism,

Israel, and Egypt's transition.)

And why should he be more critical? It's not like he was being pushed on these issues. In his various press availabilities in

Riyadh and Doha and in the seven interviews he recorded in Doha on March 5, Kerry

was peppered with questions about arming Syrian rebels and negotiations with

Iran and how he was getting along with President Obama. Not a single question was asked about

human rights or reform in the Gulf. No worries, though -- there was time for a

question about Dennis Rodman. Because the American people want to know.

This is a mistake which will have enduring implications. I've

been pointing to the

problems caused by the "Saudi exception" in American foreign policy for a

while now, and I

had urged Secretary Kerry to not set aside human rights and democracy

questions during his inaugural trip to the Gulf. By punting on these issues on

this trip he sent a clear signal about American priorities, which do not

include democracy or human rights in these Gulf countries. The sentences on Qahtani and Hamed have been months in the making, but it's hard to not interpret the timing of their harsh sentence amidst these two high profile American visits as a clear signal of "message received."

Ignoring these questions

of reform, human rights in exchange for support on strategic issues

probably seems prudent but I believe it reflects a real misreading of the evolution

of Gulf politics. Bahrain isn't over. The Saudi public sphere is rapidly transforming.

Gulf-backed

sectarianism is doing serious damage across the region. Do go read Omran's

essay on why this matters and how Saudi reformists are responding to this

American silence.

March 7, 2013

That column on sectarianism

March 5, 2013

Egypt Policy Challenge: The Results!

John Kerry's first

visit to Cairo as Secretary of State this weekend laid bare some of the deep

limitations of U.S. policy toward Egypt. Kerry, like many others, is struggling

to find a bridge between supporting a staggering Egypt and pushing it in a more

democratic direction.The administration is open to new thinking about the

nature of Egypt's problems and possible U.S. responses. Over the last month, the Middle East Channel has been hosting an

"Egypt

Policy Challenge," asking leading analysts to offer their perspective on

the nature of Egypt's ongoing political crisis and their advice for U.S.

foreign policy. Today, we are

pleased to announce the release of The Egypt Policy

Challenge as a free PDF collection

in the POMEPS Briefs series - download it today!

The challenge

was framed around the ways in which Washington might help Egypt become more

democratic. A significant portion of the policy, academic, and activist

community likely disagrees with either the goal

of democratizing Egypt, the assumption that the United States actually wants democracy in Egypt, or the idea

that the United States has any useful role

to play in accomplishing such a goal. A significant faction within the broader

policy community likely believes that Hosni Mubarak's Egypt was better for

American interests than what has followed, particularly given intense suspicion

about the Muslim Brotherhood and the widespread circulation of anti-American

attitudes across the Egyptian political arena. Many others do support the goal of democracy in Egypt, but

fundamentally reject the conceit that the United States government shares that

goal.

While those

critical views deserve attention and discussion on their own merits, the focus

of this particular Egypt policy challenge was more limited: if the United

States. does want to support a democratic transition, then what can and should

it do? [[BREAK]]

The new

administration is clearly still in evaluation mode, as Kerry repeatedly

emphasized during his trip. It is trying to assess the real intentions of the

Muslim Brotherhood and Morsi's capacity to govern as well as the opposition's

critiques of the emerging system. It is trying to determine whether the parliamentary

elections slated to begin in April can be a meaningful step toward building

real democratic institutions. It is desperate to find some way to help prevent

economic collapse and to stop the dangerous degradation of public security.

He made only

cautious moves on this first trip. He announced $250 million in immediate

economic assistance, including a new $60 million Egyptian-American Enterprise

Fund. He urged the opposition to take part in the upcoming elections and the

government to ensure that they would be free and fair. He said many of

the right things about U.S. priorities, pushing President Mohamed Morsi to

compromise and the opposition to participate in the elections. His statement on

the trip made clear that

"more

hard work and compromise will be required to restore unity, political stability

and economic health to Egypt. The upcoming parliamentary elections are a

particularly critical step in Egypt's democratic transition. We spoke in depth

about the need to ensure they are free, fair and transparent. We also discussed

the need for reform in the police sector, protection for non-governmental

organizations, and the importance of advancing the rights and freedoms of all

Egyptians under the law -- men and women, and people of all faiths."

Few found this

rhetoric or the new U.S. commitments satisfying, of course. The hotly polarized

political environment in Egypt made such a balancing act excruciatingly

difficult, as all sides hope for a more explicit endorsement of their position and bitterly resent anything which does not fully reflect their narrative. But for all the frustration, Kerry was right to make Egypt one of his first stops. This is a good moment for

the U.S. to take stock of what is happening in Egypt: Has it diagnosed Egyptian

politics correctly? Is it offering useful advice and material support? Is it communicating its policy

effectively?

The free PDF The Egypt Policy

Challenge collects some of the best recent analyses and recommendations

on these difficult questions. The

contributors include Holger Albrecht, Steven Cook, Michael Wahid Hanna, H.A.

Hellyer, Ellis Goldberg, Hani Sabra, Tamara Wittes, Elijah Zarwan and more. Download

it today!

February 28, 2013

Louis Vuitton John

My weekly FP column just went up: "Welcome to the Middle East, Mr. Secretary -- here's what to expect." The column offers John Kerry some friendly advice on what he is likely to hear and what he should say in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE and Egypt. Besides some suggestions on Syria and Egypt, I urge him to bring up democracy and human rights issues on all of his stops -- including raising Bahrain and Mohammed Fahd al-Qahtani in all the Gulf capitals -- no matter how awkward that might seem. There's only one chance to make first impressions, and not mentioning them will speak volumes.

I was pretty happy to be able to work "Louis Vuitton John" into the piece, though I couldn't find a place for the full lyrical reference: "since I signed the con I'm Louis Vuitton John heading out to Ram to eat up all the shwarm." That's what blogs are for.

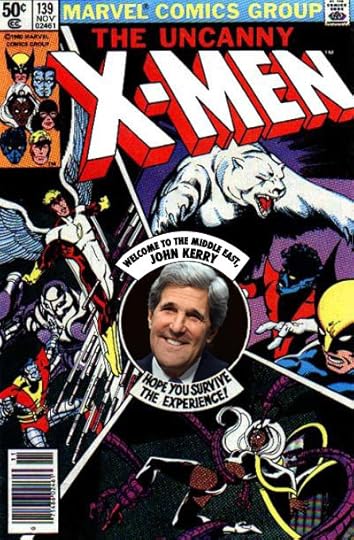

And since I couldn't figure out how to get the inspiration for the piece's title into the actual column, I'm thrilled to be able to post it here (thanks Erin!): Welcome to the Middle East, John Kerry.. Hope You Survive the Experience!

I'll have more discussion of it in a later post, but for now I just wanted to be sure that blog readers knew about it. After getting Big Sean and a classic X-Men meme into an FP article, my work here is done.

February 25, 2013

An impromptu American-Iranian dialogue

Talks between

Iran and the P5+1 on the Iranian nuclear program are set to begin tomorrow in

Kazakhstan after some eight months. The expectations game is in full swing, with American officials tipping

an offer of a "clear pathway" to sanctions relief (which won't

be easy) and Iran

signaling a tough initial line. Few expect

a breakthrough at the talks, but there is some hope that it might lay the foundation for more

regular, ongoing negotiations on the core issues or even to direct U.S.-Iran

talks. I don't know

what's going to happen in Almaty. But at this weekend's Camden Conference in Maine, I at

least got a preview of what the opening rounds of a direct Iranian-American

dialogue might look like. It wasn't pretty. But it was a useful demonstration of the vast

conceptual divide between the two sides which any negotiation will somehow need

to bridge.[[BREAK]]

The preview

came at the end of the first day of the conference. Shai Feldman of Brandeis University first presented a

detailed, sophisticated account of Israeli strategic thinking about Iran (see

here for a sample of his analysis on the Middle East Channel). He left the stage following his remarks, and was followed by Hossein

Mousavian, a former Iranian nuclear negotiator and currently a Research

Scholar at Princeton University who presented a standard Iranian narrative

of unjustified international suspicion and illegitimate international pressure

(his December

Carnegie Council presentation and today's FT column gives a sense of his talk).

But the

anticipated Israeli-Iranian rhetorical standoff never materialized, because with Feldman off-stage the United

States stepped forward instead in the person of conference moderator Nicholas

Burns. (Take the symbolism of that as you will). Burns, a former under-secretary of state for political affairs and currently a professor at Harvard

University, played a key role in American policy towards Iran at the State

Department. When he sat down for

the Q+A following Mousavian's presentation, he couldn't let certain parts of

the Iranian narrative pass unremarked.

What followed

was a rare and revealing public interaction between two retired officials who

had played key roles in the policies of their respective governments but rarely had the opportunity to interact officially. Burns called out Mousavian on the Iranian government's support for terrorism, the broad

international consensus on Iran's nuclear ambitions. Mousavian challenged Burns on the impact of sanctions, the

underlying assumptions of the focus on the Iranian nuclear program, and Iran's

legal right to peaceful nuclear energy and enrichment. (Oddly, the hostage crisis didn't appear in his historical narrative.) Why so much mistrust of

Iran, wondered Mousavian; perhaps

because the Iranian government has lied about its nuclear activities so often, countered Burns. If the Iranian government is so

blameless, Burns suggested, why is it that the Security Council including

Russia and China is united against it on these issues; they aren't, really, came the response.

How could the U.S. justify the human toll of the sanctions on the Iranian

people, asked an audience member; what other alternative is there to war if

Iran will not deal with a unified international community, countered Burns (a

sizable portion of the audience booed).

By the end,

one frustrated member of the audience challenged both men on their radically

divergent narratives: How, she

asked, can anyone hope to resolve this issue if there isn't even a single set

of agreed upon facts? That's a familiar problem in any polarized and entrenched conflict, of course, and hardly new to bargaining theory or practice. But it's still worth recalling and bringing to the forefront. The

real issues standing in the way of a negotiated settlement of the Iranian

nuclear issue are daunting enough: verification and timing issues; the fears

and ambitions of regional players such as Israel, Turkey and the Gulf states;

Iran's right to enrichment; the ongoing shadow war between the two sides; and very real

questions about whether either Iran or the United States genuinely wants a deal

or is capable of agreeing to or implementing one. But nobody should dismiss the

significance of that added layer of mutual incomprehension and radically

opposing narratives, and the cognitive or political incentives to keep them that way. If there's any real hope of reaching a deal, then at some

point those pre-negotiations are going to have to begin.

This obviously

isn't the first time that such exchanges between top former American and

Iranian officials have taken place, so I don't want to exaggerate its significance. But it was fascinating to watch it unfold in public (similar encounters I've witnessed have all been at private, off the record events). Real talks, so urgently needed, will be carried out by people who think, talk and act very much like their highly professional and experienced former colleagues. In other words, as Burns told me

afterwards, the conversation on the Camden stage probably looked something like the opening round of the real

direct Iranian-American talks -- especially if they are done in public: testy

at times, exposing more disagreement than

consensus, and not visibly changing any minds ... but nonetheless a critical first step.

Syria's Hard Landing

How can the United States and the international community best help Syrians in the face of its escalating horrors? The most popular recommendation in Washington circles is to provide more weaponry to the "moderate" parts of the Syrian opposition in order to help their military efforts against the Assad regime and to strengthen politically against the increasingly powerful jihadist trends in the opposition. I continue to believe that arming the rebels is unlikely to tip the military balance against Assad, bring the fighting to an end, create enduring influence with the Syriabn rebels, or crowd out the jihadists. As arms pour in and the fighting doesn't end, this will almost certainly continue to dominate the international policy debate (Last week I hosted a roundtable to debate those points.)

But there should be more to the debate than only whether or not to arm the rebels. Given the scale of the humanitarian devastation and political stalemate, it's entirely fair to ask what alternatives remain. On Friday, the Center for a New American Security released my new policy brief, Syria's Hard Landing, which lays out a set of policy alternatives beyond arming the rebels. The main recommendations include a push at the U.N. for a massively increased cross-border humanitarian operation and for explicit integration of that aid with the construction of opposition-based alternative governance structures. My weekly column presenting those recommendations only made it online during the peak prime time of late Friday afternoon, though, because of the report's production timeline.

With this post I therefore urge you to read my column, "Here's Your Plan B: Arming rebels isn't the only (or best) way to help Syria" and the Syria's Hard Landing report upon which it is based. As always I look forward to feedback, and if I get enough productively critical responses I'll publish another roundtable.

February 21, 2013

Roundtable: arming the Syrian rebels

My FP column last week argued that the Obama administration was correct

to reject plans to arm the Syrian opposition. The objections

to arming have become weaker as the conflict has become fully militarized,

I argued, but the upside to arming has not become substantially higher. My

column tomorrow will feature the second half of my current take on Syria, with a

set of alternative policy recommendations drawn from my forthcoming CNAS Policy

Brief. Stay tuned for that tomorrow!

Today I am happy to be able to feature three interesting and important

responses to my column. This is

part of my ongoing effort to promote serious, critical debate and discussion on

these issues (for previous episodes, see the Egypt

policy challenge responses and the Twitter

Devolutions responses). Today's

roundtable features Daniel Byman (Georgetown and Brookings), Emile Hokayem

(International Institute for Strategic Studies), and Mona Yacoubian (Stimson

Center). I am also going to quote from a piece by

Karl Sharro that touched on similar themes. I regret that several others whom I invited didn't have time to contribute to the roundtable, but I look forward to hearing their thoughts in other venues. [[BREAK]]

Daniel Byman (Security Studies Program

at Georgetown University and research director of the Saban Center at Brookings).

I've long championed aiding the Syrian opposition and warned

that Assad might not fall

unless pushed. Yet as Marc Lynch has

contended in his columns (and many other skeptics in and out of

government would agree) aiding the opposition is risky. Even if done well it could easily fail,

and the United States might feel obliged to further escalate and deploy its own

troops, which would be a mistake. Although the Obama administration appeared to

consider and reject supporting the opposition last year, again the option is

bruited about as U.S. policy toward Syria continues to

flounder.

With a large and sustained program to arm (and particularly

train) the opposition, the United States can shape it, enabling more moderate

forces to gain strength vis-à-vis radical rivals and prove themselves on the

battlefield. A more effective and

moderate opposition increases the chance that Assad will fall and, just as

important, that a post-Assad Syria will avoid being a failed state. Coordinating

U.S. efforts with those of Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other regional allies

would increase our chances of success.

However, a sense of realism is necessary. We are years late to the game, and the

opposition is painfully fractious -- while radicals are more and more

entrenched. Iran has gone all-in

to support Assad, and he shows no sign of giving in. In the past, some of the insurgents backed by the United

States remained inept and, even more jarring, ungrateful for U.S. support after

the conflict ended.

Yet the other possible policies are off the table or even

more risky. The United States is

not about to intervene with its own troops, and diplomatic solutions have failed

again and again. Beyond the

increasingly horrific body count and refugee flows, ignoring the conflict is

also risky, as violence from Syria

is spilling over into neighboring states and risks destabilizing the region as

a whole. So aiding the opposition ends up being the best -- or really

the least worst -- option.

Emile Hokayem, International Institute for

Strategic Studies

Thanks

for the opportunity to engage in the debate. You make an articulate but

ultimately unconvincing argument in favor of withholding any kind of military

help to the Syrian rebels.

First,

let's dispense with a few matters. I don't argue my case from the perspective

of U.S. interests -- I am not an American citizen, so I factor U.S. interests only as

part of a broader mix of considerations.

Very

few people who support the arming of the rebels make the case for a direct

military intervention. Intervention has become a catch-all word to dismiss

advocates for more limited action as unreformed hawks (many among us opposed the

Iraq war and agree that intervention should be the rarest of exceptions). I too

question the wisdom and merits of a direct intervention (including a no-fly

zone and a safe zone) in current circumstances. Given the very complex Syrian

terrain, the risks and costs are likely to be enormous. A direct intervention

may be needed in the extreme cases of WMD use or if genocide, contingencies

that military planners would do well to consider.

Second,

I accept that some types of weaponry, including anti-aircraft missiles are too

sensitive to be introduced. I actually find it unfair that the U.S. is singled

out for its opposition to the delivery of such weapons to the rebels when other

countries, including Turkey, have done so for fear they would reach jihadi or Turkish

separatist groups.

The

case against arming the rebels is often followed by a plea for renewed,

creative diplomacy, which often would somehow be undermined by supplying weapons.

First, diplomacy is in a comatose state and, as I

argued in Foreign Policy, Assad will have none of it beyond theatrics.

Second, why should diplomacy and strengthening the rebels be mutually exclusive

and decoupled? History is rife of examples of both strategies being deployed in

parallel. After all, NATO had to help the Croats and the Bosnians ahead of the

Dayton talks, which often cited as a possible template for Syria.

With

a death toll on par with the worst months of the Iraq war, the argument that

"more guns will lead to more violence" is the weakest one in the debate. And

the question is not the quantity of weapons but its distribution among the

various groups. Assad not only has better weapons in greater quantity, he also has

access to re-supply from Iran and Russia and a local defense industry. Also,

one doesn't have to be a scholar of just war theory to know that not all

violence is the same.

The

case for arming the rebels has evolved over time. At first, arming (with or

without a no-fly zone) was supposed to convey a sense of Western commitment to

the downfall of Assad that would send a decisive message to key players in the

military and the regime, thus encouraging defections.

Then,

it became about giving the rebels a military edge, but I think the military

rationale is overstated. It is simply too late to organize and equip the rebels

in a manner that would quickly bring down the regime while preserving the state

for a smooth transition (I also accept that this goal was probably unrealistic,

but perhaps less so than the U.S. administration's continued attachment to a

peaceful transition that would follow a political solution). That initial goal

has crumbled: The regime is holding on while the state is essentially gone.

Forget those ridiculous headlines about Assad and his lieutenants being in a

state of panic -- the regime can still allocate military resources in a rational

manner and can put up a fight where it needs to.

The

Syrian rebels have never been given a reason to coalesce and the dithering has

made things worse. Some analysts will argue, based on historical precedent,

that they would never have, but this has to be tried. Analysts will say the U.S.

has constantly failed at picking winners, but that's the wrong expectation.

Many of those who argue against arming pretend that their opponents in that

debate are promising the moon in return for weapons. I am not. The U.S. will in

no case pick the winning party in Syria; the question is whether whoever fights

now or wins later will even care to listen to the U.S. or any other Western

state.

In

the very unlikely event Russia and the U.S. agree on Syria, both will likely have

zero leverage to translate this into a regional and Syrian political solution.

The political leaders the U.S. supports today will be powerless to negotiate, let

alone enforce anything because they couldn't deliver in time of need. It may

well be impossible to contain the worst instincts of warlords and military

leaders who, having seized power through blood and force, will be reluctant to

abide by the rules of politics.

In

the not-so-distant future, jihadi groups may well roam on the borders with

Israel, Jordan, Lebanon or Turkey, and do nasty things. The U.S. may then feel

compelled to send its drones to take them out because it will not have local

partners to turn to for help. The narrative that day will be that the U.S.

couldn't be bothered to meaningfully help the revolutionaries against Assad but

doesn't bother to go after those who did. It will be an imperfect and unfair

narrative, but it will resonate across the region.

By

waiting for so long before engaging the Syrian rebels in a meaningful manner,

the Western states (now that the EU has renewed its arms embargo) have made

themselves at best marginal to the dynamics of a conflict that has already

overtaken Iraq's in regional and strategic terms and will shape the future of

the Levant. Every other state is developing proxies and allies.

Let

me end with this: Let's assume that you are indeed right that the course chosen

by the Obama administration is the best. I hope you will agree that even this

policy is under resourced, badly implemented, and awfully communicated, and that

it likely won't have any significant, let alone decisive impact inside Syria.

Mona Yacoubian, Stimson

Center

Arming the Syrian opposition remains a bad idea. If anything, Syria's chaotic evolution

toward sectarian civil war vindicates the Obama administration's caution on the

question. The potential is great

for unintended consequences: Arms

may fall into the wrong hands, and the United States could get sucked into a long,

nasty proxy war that foments spillover across the region. Lessons not only from Afghanistan, but

also Libya (from Benghazi to Mali), highlight the deadly pitfalls of funneling

arms into conflict. That such an

inherently volatile and complicated process can be successfully "managed"

requires a significant leap of faith.

Beyond that, the negative repercussions would be significant

should the United States essentially become a partisan in an evolving sectarian

civil war. In the region, the United States is already perceived as favoring

Sunni (and in some cases Islamist) interests as in Bahrain or the Muslim

Brotherhood in Egypt. Rather than

an "above the fray" superpower seeking a negotiated outcome that ushers in a

post-Assad Syria, the United States would be viewed by many as simply a

partisan player in a Sunni-Alawite civil war. Its ability to help promote the emergence of a

multi-sectarian, democratic Syria would diminish significantly. Indeed, U.S. interests in a post-Assad

Syria must rise above sectarian agendas.

Moreover, greater U.S. involvement in Syria's civil war would also

open the United States up to greater security threats in the region and beyond

(remember Lebanon). US arming of

Sunni armed groups in Syria could provoke Hezbollah, Iran, or others to launch attacks on U.S. targets. The

United States should avoid being implicated more directly in the destabilizing Sunni-Shiite

conflict that is expanding across the region.

Three critical factors have remained constant since the

beginning of Syria's uprising and are responsible for its downward spiral from

peaceful protests to sectarian civil war:

1) The regime's perception of any protest (peaceful or otherwise) as an existential threat and

therefore its unwillingness to reform or negotiate. Instead, Assad and those around him are engaged in a fight

to the death; there is no "Yemen solution" to Syria.

2) The opposition's

inability to overcome ethno-sectarian divisions and unite around a

vision of post-Assad Syria which would provide solid guarantees (not just

assurances) to Syria's minority communities, especially Alawites, Christians,

and Kurds.

3) The international community's enduring stalemate, marked

by an inability to forge a consensus on Syria that has rendered the UN

ineffective and dramatically minimized the prospects for successful diplomacy.

The only way to cease Syria's continuing downward spiral

would be to reverse at least two of these three factors. U.S. arming of the opposition would have

the opposite effect. It would further

polarize the international community, pushing Russia (and of course Iran)

further into the regime's corner. Moreover,

U.S. arming of the opposition would do nothing to alleviate minorities' deepening

concerns that there is no place for them in a post-Assad Syria. In short, U.S. arming (direct or

indirect) can do greater damage than good -- distancing the prospects the Syrian

conflict's resolution and embedding

the United States into a dangerous sectarian dynamic that is spreading across

the Middle East.

Karl Sharro, "The

Myth of Constructive Meddling"

[This is excerpted from a blog post, which you should be

sure to read in its entirety.]

...The underlying assumption among analysts is that the U.S.,

and the West more broadly, should adopt a "sticks and carrots" approach to

encourage the armed rebel groups to fall in line with the political opposition

and isolate the more radical elements thus weakening their influence.

Those calls are voiced by analysts that have demonstrated that they really

understand the dynamics of the conflict in Syria, particularly in terms of the

military, geo-strategic and logistical aspects. The option appears seductive

because it appears as a logical extension of this body of knowledge and the

analysis built on top it. It is nevertheless a delusion. At the heart of this

is characteristic arrogance that assumes that favourable outcomes could be

orchestrated through a calibrated policy of political, financial and military

support.

....the emerging policy option suggests arming and supporting

the more moderate elements. The mistake here is assuming that weapons and

financial support can compensate for lack of or weak popular support.

Furthermore, it totally ignores the way in which Jabhat al-Nusra and the

multitude of Islamist brigades and groups will be able to use that to galvanise

further support, as Hezbollah has done successfully in the past by seizing on

evidence of external support for its opponents.

.... The ‘arming the moderates' option is an exercise in abstract

political logic that is entirely oblivious to the fast-changing social and

political dynamics in Syria. The military and strategic snapshot it relies on

provides only half of the picture....

February 19, 2013

Will the Kingdom be Atomic?

If Iran gets a nuclear weapon, will it set off a cascade of

unmanageable nuclear proliferation in the Gulf? Not necessarily, according to "Atomic Kingdom," a fascinating and

deeply researched new report from the Center for a New American Security (full

disclosure: I'm a non-resident senior fellow at CNAS, but I didn't review this

report). Colin Kahl, Melissa Dalton, and Matt Irvine make a pretty strong case

that its own self-interest would probably stop Saudi Arabia from taking the nuclear plunge. Their report is a vital corrective to one of those

poorly-vetted Washington "facts" which too often shape policy ... even if it

ultimately raises as many questions as it answers.[[BREAK]]

The logic of "Atomic Kingdom" is fairly

straightforward: While Riyadh

would feel deeply threatened by an Iranian nuclear weapon, the costs to Saudi

Arabia of secondary proliferation would be higher than most assume, its

technical capability to make the move is less than most believe, and it has

better options at its disposal to enhance its security in the face of a nuclear

Iran. Nor is the long-rumored Pakistani option for an off the shelf bomb very

likely, given the risks and costs to both sides in doing so. Instead, the authors argue, Saudi Arabia

is more likely to push for an American nuclear umbrella and deeper security

guarantees (which would not be without its own complications).

They draw usefully on the academic literature

on nuclear proliferation to frame their case, in a prime example of the policy

relevance of academic research that we all so love to debate. As Kahl put it to me over email, it is indeed striking that "nuclear

cascades have been predicted for decades, yet since the NPT went into force,

cascades have never actually occurred." What do we do with that track record? As with my argument about the lessons for Syria of the literature on the dismal track

record of external arming of rebel groups, this doesn't prove that it wouldn't

play out differently in this particular case. Iran and its neighbors might really be different, just like

Syria might really be different from all the other comparable cases. But it would be folly to ignore

both the lessons of history and rigorous analysis of causal mechanisms when trying to formulate policy responses.

The

core of their argument is that going nuclear wouldn't be Riyadh's choice

despite its oft-expressed anxieties about Iran. They see Riyadh as facing "profound disincentives to rushing

to a bomb or acquiring one "off the shelf" from Pakistan, including

the prospect of facing crippling economic sanctions and a rupture in the U.S.-Saudi

strategic partnership." A key to their logic is that "Saudi Arabia acquiring its own nuclear weapons could, on net, make

the threat to stability worse, not better." It would find itself potentially targeted by Israel or by

Iran, it might find itself locked into an arms race, the nuclear weapons might

be an attractive target for domestic jihadists, and it might run afoul of

Congress regardless of whether the White House prefers to let it pass. The most likely outcome, in their view,

is based on the classic Realist calculation that Riyadh would opt to balance

Iranian nuclear power by moving closer to Washington rather than bandwagoning

with a hated Tehran, going it alone, or relying on an unpredictable and

competitive Pakistan.

The

argument is well-made, but I see some key points which remain unresolved. India and Pakistan got away with going

nuclear, oil behemoth Saudi Arabia is hardly a prime target for economic

sanctions, and Washington doesn't have a great track record of standing up to Riyadh.

What's more, the authors probably overestimate the rationality and coherence

of Saudi foreign policy, which might leap forward out of status concerns or

irrational terror of Tehran despite the compellingly logical reasons they

shouldn't. For that reason, I just hope that "Atomic

Kingdom" is read closely in Riyadh and its logic fully internalized there among

the relevant decision-makers.

One other point struck me. The report

demonstrates effectively why Saudi Arabia might prefer an American nuclear

umbrella over other options, but what about the United States? Would Washington genuinely prefer a

nuclear umbrella over Saudi to its standing up its own deterrent? Kahl noted that such a nuclear umbrella "would keep the United States

bogged down in costly defense commitments in the Gulf for decades to come,

entrenching ties to the least democratic countries in a democratizing region

and limiting Washington's ability to strategically pivot toward Asia." Those are all rather problematic for

the kind of "right-sizing"

Middle East strategy which I think the Obama administration should be, and

arguably is, pursuing.

Despite these questions, Atomic Kingdom" is a good piece of

work which should generate some interesting and useful debate about the probability and the potential responses to a nuclear cascade in the Gulf. I hope it gets

widely read and discussed --- and I'm especially keen to see the response from Riyadh!

February 18, 2013

Debating Jordan's Challenges

"375,000

Syrians have come to Jordan since March 2011, which is 6-7% of our population.

In American numbers, at that rate, this is 17-18 million people." The spillover effects of the Syria

conflict were very much on the mind of Jordanian Foreign Minister Nasser Judeh

during a wide-ranging conversation over coffee in Washington last week. His government's

focus for Syria was very much on finding a political transition which, he said,

"everybody realizes at this stage is the only game in town." His other primary preoccupation was to advance a narrative of successful reform following Parliamentary elections against my more cynical perspective.

On the problem of Syrian refugees, Judeh and I had little about which to disagree. Jordan has good

reason to be concerned about the impact of Syrian refugees on the Kingdom.

The flow from

Syria has been more intense than the wave of Iraqi refugees during the last decade: faster,

more concentrated, and with no end in sight. The early accommodations for a much smaller refugee flow have struggled to keep pace, and Jordanians are feeling the strain from hosting this massive influx (things have only gotten worse since this sharply reported FP account by Nicholas Seeley a few months ago). [[BREAK]]

Judeh presented at length the plight of the

Syrian refugees in the Kingdom, who often arrive in desperate conditions, fleeing fighting and

needing urgent medical care. For a

long time, he said, 500 to 700 people a night crossed the border. But now it is up to 3,000 to 5,000 a

night. Jordan never

established a refugee camp for Iraqi refugees, preferring that they disperse

through the cities, but has already established one for Syrians (and has plans

for a second). Conditions in that

camp have been grim during a harsh winter. And while there is a great

deal of "goodwill" in the international community, including substantial

pledges of humanitarian aid at the recent Kuwait donors crisis, the cold fact

is that the international community has failed to deliver needed assistance for

these refugees. Jordanian

officials estimate costs of nearly $500 million in 2013 in energy, food, water,

education, health and subsidies. They should get it.

The impact of the refugee flow and fears of militarized spillover give some urgency to Jordan's efforts to find some solution. Foreign Minister Judeh repeatedly emphasized the goal of an inclusive political

transition agreement for Syria, and brushed aside questions about possible plans for arming rebels or no-fly zones. He

worried about the potential territorial breakup of Syria, which he described as

"a danger that we should avoid at all cost." He told me the same that he told several other interviewers: "for all intents and purposes this is a

civil war of a political nature," but the worst scenario would be that it

devolves into a true "ethnic sectarian civil war."

For Jordan, he insisted, "what is most important to us as a country

contiguous to Syria is to preserve the territorial integrity of Syria, to do

everything in our power to ensure that whatever transition takes place in Syria

is all inclusive." Judeh seemed encouraged by recent signals from Moaz al-Khatib,

head of the Syrian National Coalition, of a willingness to engage in talks, and

supportive of the ongoing efforts of United Nations Special Envoy Lakhdar

al-Brahimi. He couldn't point to signs that the Assad regime was interested,

but emphasized again: "I think everybody realizes that at this stage the

political transition is the only game in town."

Our

conversation ranged over a wide range of issues besides Syria, of course. He emphasized yet again Jordan's view

of the urgency of engaging on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, and

emphatically dismissed any suggestions that Jordan wanted any role in the West

Bank other than one supporting the creation of a sovereign, independent and

territorially contiguous Palestinian state. (I joked that I should program my

recorder to automatically replay his rejection of Israeli ideas about the "Jordanian Option"

every six months.) He also emphasized the serious economic stakes

involved in Jordan's ongoing discussions with Egypt over its failure to provide

promised levels of natural gas, upon which the Jordanian economy is highly

dependent.

But the lion's share of our conversation following the discussion of Syria focused on Jordan's domestic politics, which turned into a long, interesting and productive (if inconclusive) debate. As Judeh knew well, I've been publicly and privately skeptical about the extent and implications of Jordan's reforms, after long years of watching royal promises of change fail to materialize. Why, I asked, should we expect these reforms to be any different from the repeated cycle of past empty promises, to significantly empower the elected Parliament or to meaningfully change the nature of monarchical authority?

Judeh

was keen to convince me that these reforms were different. He

stressed that Jordan had met the benchmarks it laid out for itself in the

reform process: revising the constitution, enacting relevant laws, establishing

an independent election commission and a constitutional court, and holding

elections. "This marks the end of

the constitutional phase of the reforms," he argued, and the beginning of a new

phase of consolidating Parliamentary government. He portrayed the process of government formation now

unfolding, in consultation with Parliamentary blocs, as an historic change. Now, he insisted, we would see the unfolding of a new culture of Parliamentary government and the crystallization of genuine political parties and blocs. Who could have imagined, he argued, that the King would go before Parliament and demand that it launch a "White Revolution"?

But why would this be any different than before, I pressed him? He acknowledged past failures, but argued that this time the reforms were irreversible, fully

embedded in the constitution and new institutions and fully supported by the

King. He argued that the new institutions and authorities embedded in the Constitution would prevent any relapse; I countered that the law hadn't really prevented government by emergency law from 2001-2003. He pointed to the many new faces in Parliament and the high electoral turnout; I noted that the "new" Parliament selected as Speaker Saad Hayel Srour.. for the sixth time. He pointed to the high turnout and the genuinely impressive performance of the new Independent Election Commission; I pointed out the continuing controversy around the election law and gerrymandered districts, and the fragmented and conservative Parliament it produced. (For more on this, see my conversation with Yale's Ellen Lust, who was in Jordan for the election.) And around it went.

The bottom line is that the Palace is clearly feeling its oats on reform after the election, and thinks it has a positive story to sell at home and abroad. Casual observers will likely be easily convinced by the narrative they are offering. Skeptics like me are going to want to see a lot more: the new institutions actually functioning to constrain executive power, the Parliament actually behaving like a Parliament, and so on. Judeh's trump

card was that after all that had happened in the region, the overthrown regimes and wars and economic crises, "we are still here. We

must be doing something right."

Perhaps.

Marc Lynch's Blog

- Marc Lynch's profile

- 21 followers