Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 131

February 19, 2017

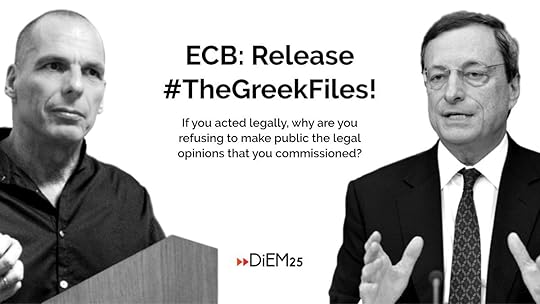

Τι φοβάστε κύριε Ντράγκι; Ώρα να δημοσιοποιήσετε την γνωμοδότηση για το κλείσιμο των ελληνικών τραπεζών

Υποστήριξε την εκστρατεία μας να απαιτήσουμε την άμεση δημοσιοποίηση νομικής γνωμάτευσης για το εάν η ΕΚΤ παρανόμισε κλείνοντας τις ελληνικές τράπεζες το 2015 και επιβάλλοντας capital controls.

ΥΠΟΓΡΑΨΕ ΠΑΤΩΝΤΑΣ ΕΔΩ

Συνυπογράφοντες: Benoît Hamon (υποψήφιος του Σοσιαλιστικού Κόμματος για την Προεδρία της Γαλλικής Δημοκρατίας), Katja Kipping(Πρόεδρος της Die Linke), Gesine Schwan (δύο φορές υποψήφια του SPD για την Προεδρία της Ομοσπονδιακής Δημοκρατίας της Γερμανίας), Γιάνης Βαρουφάκης (DiEM25)

Το 2015, η Ευρωπαϊκή Κεντρική Τράπεζα οδήγησε στο κλείσιμο των ελληνικών τραπεζών, πλήττοντας την ήδη πληγωμένη ελληνική οικονομία με στόχο να επιβληθούν στην ελληνική κυβέρνηση νέα υφεσιακά μέτρα, νέες απώλειες εθνικής κυριαρχίας και νέα μη βιώσιμα δάνεια.

Γνωρίζουμε ότι, πριν προβεί στο κλείσιμο των ελληνικών τραπεζών, η ΕΚΤ ζήτησε γνωμάτευση από ιδιωτικό νομικό γραφείο για το εάν οι ενέργειες της ήταν νόμιμες.

Σήμερα η ΕΚΤ αρνείται να δημοσιοποιήσει το περιεχόμενο εκείνης της γνωμάτευσης που πληρώθηκε με χρήματα των ευρωπαίων πολιτών.

Αν πράξατε νομίμως κ. Ντράγκι, γιατί φοβάστε να δημοσιοποιήσετε την γνωμάτευση;

Εμείς απαιτούμε να μάθουν οι ευρωπαίοι το περιεχόμενο εκείνης της γνωμοδότησης!

Στη Ευρωζώνη, η δυνατότητα της ΕΚΤ να κλείνει τις τράπεζες ενός κράτους-μέλους με αποφάσεις που λαμβάνονται κεκλεισμένων των θυρών, και χωρίς καμία διαφάνεια, παραβιάζει κάθε δημοκρατική αρχή. Παραβιάζει ακόμα την φιλοδοξία και την καταστατική υποχρέωση της ΕΚΤ να είναι ανεξάρτητη και υπεράνω πολιτικών σκοπιμοτήτων. Το ελάχιστο που μπορούν να περιμένουν οι Ευρωπαίοι, είναι πρόσβαση σε νομικές γνωμοδοτήσεις για τις οποίες έχουν πληρώσει οι ίδιοι!

Ως ένα πρώτο βήμα καμπάνιας για την Διαφάνεια στην ΕΕ και την ΕΚΤ, ο Γιάνης Βαρουφάκης (DiEM25) και το μέλος του ευρωπαϊκού κοινοβουλίου Fabio De Masi (GUE/NGL) θα καταθέσουν επίσημο αίτημα στην ΕΚΤ να δημοσιοποιηθεί η σχετική νομική γνωμάτευση.

Τo DiEM25 σας καλεί να συνυπογράψετε το αίτημά των Βαρουφάκη-DeMasi

ΥΠΟΓΡΑΨΕ ΠΑΤΩΝΤΑΣ ΕΔΩ

Mr Draghi, what are you afraid of? Release #TheGreekFiles!

Join the campaign to demand that the ECB publish the legal opinion it commissioned on whether its closure of Greece’s banks in 2015 was… legal. CLICK HERE!

February 14, 2017

Yanis Varoufakis on BBC: “Western Democracies need a New Deal”

Here Yanis Varoufakis, former Greek Finance Minister, argues that it’s time for a “New Deal” – including a universal basic income.

Greece’s Perpetual Crisis

ATHENS – Since the summer of 2015, Greece has (mostly) dropped out of the news, but not because its economic condition has stabilized. A prison is not newsworthy as long as the inmates suffer quietly. It is only when they stage a rebellion, and the authorities crack down, that the satellite trucks appear.

The last rebellion occurred in the first half of 2015, when Greek voters rejected piling new loans upon mountains of already-unsustainable debt, a move that would extend Greece’s bankruptcy into the future by pretending to have overcome it. And it was at this point that the European Union and the International Monetary Fund – with their “extend and pretend” approach in jeopardy – crushed the “Greek Spring” and forced yet another unpayable loan on a bankrupted country. So it was only a matter of time before the problem resurfaced.

In the interim, the focus in Europe has shifted to Brexit, xenophobic right-wing populism in Austria and Germany, and Italy’s constitutional referendum, which brought down Matteo Renzi’s government. Soon, attention will shift again, this time to France’s crumbling political center. But, lest we forget, the inane management of Europe’s debt crisis began in Greece. A minor country in the grand scheme of things in Europe became a test case for a strategy that could be likened to rolling a snowball uphill. The resulting avalanches have been undermining the EU’s legitimacy ever since.

The problem with Greece is that everyone is lying. The European Commission and the European Central Bank are lying when they claim that the Greek “program” can work as long as Greece’s government does as it is told. Germany is lying when it insists that Greece can recover without substantial debt relief through more austerity and structural reforms. The current Syriza government is lying when it insists that it has never consented to impossible fiscal targets. And, last but not least, the IMF is lying when its functionaries pretend that they are not responsible for imposing those targets on Greece.

When so many lies – with so much political capital invested in their perpetuation – coalesce, disentangling them requires a swift coup, akin to Alexander cutting the Gordian knot. But who will wield the sword?

Tragically, the problem is both obvious and extremely simple to solve. The Greek state became insolvent a year or so after the eruption of the 2008 global financial crisis. Against all logic, the European establishment, including successive Greek governments, and the IMF extended the largest loan in history to Greece on conditions that guaranteed a reduction in national income unseen since the Great Depression. To mask the absurdity of that decision, new loans – conditioned on more income-sapping austerity – were added.

When one finds oneself in a hole, the simplest solution is to stop digging. Instead, Europe’s powers-that-be, the Greek government, and the IMF blame one another for driving Greece’s people into an abyss.

Recently, Poul Thomsen, the director of the IMF’s European Department, and Maurice Obstfeld, its chief economist, protested in a jointly authored blog post, that “it is not the IMF that is demanding more austerity.” The blame lay elsewhere. “[I]f Greece agrees with its European partners on ambitious fiscal targets,” they argued, “don’t criticize the IMF for being the ones insisting on austerity when we ask to see the measures required to make such targets credible.”

Thomsen and Obstfeld are partly right. Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras had no business agreeing to the crushing fiscal targets demanded by Germany and the EU when I was the finance minister. My successor’s claims that the government never accepted the targets are disingenuous. As he well knows, I resigned chiefly because in April 2015 Tsipras agreed to them behind my back. My former colleagues are shooting the messenger, the IMF in this case, for relaying the bad news that the targets they agreed to require even more austerity.

It is also true that the IMF consistently, and correctly, criticized the targets. But what Thomsen neglects to mention is that, without his and IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde’s personal connivance, the European Commission would not have been able to impose those targets. And I should know: I represented Greece in the meetings of the Eurogroup (comprising the eurozone countries’ finance ministers) where it happened.

Thomsen seems to be aware of his responsibility to stop legitimizing the German-led asphyxiation of Greece’s economy. In a telephone conversation in March with Delia Velculescu, the IMF’s Greek mission chief, Thomsen explained what should happen if Germany insisted on crushing Greece by not granting debt relief. According to the transcript of the call (released by WikiLeaks), Thomsen thought European leaders would leave the issue until after the United Kingdom’s Brexit referendum.

According to Thomsen: “[W]e at that time say, ‘Look, you Mrs. Merkel you face a question, you have to think about what is more costly: to go ahead without the IMF, would the Bundestag say ‘The IMF is not on board?’ Or to pick the debt relief that we think that Greece needs in order to keep us on board?” Right? That is really the issue.”

Velculescu responded that, “for the sake of the Greeks and everyone else, I would like it to happen sooner rather than later.” But it did not happen, because Thomsen and Lagarde never dared to put Merkel on the spot. Instead, the IMF continues to blame others while providing Germany with political cover to maintain its chokehold on Greece.

But, as Velculescu astutely pointed out, the repercussions affect “everyone else.” The troubling developments in Italy, France, and even Germany are a direct consequence of the Greek debacle. But Greece is the immediate victim, and it is therefore the Greek government’s responsibility to cut the Gordian knot, by declaring a unilateral moratorium on all repayments until substantial debt restructuring and reasonable fiscal targets are agreed.

Greece’s voters twice gave their leaders a mandate to do just that: once when they elected the Syriza government in January 2015, and again that July in a referendum. For the sake of Greece – and of Europe – the authorities need to call a spade a spade.

A New Deal to Save Europe

LONDON – “I don’t care about what it will cost. We took our country back!” This is the proud message heard throughout England since the Brexit referendum last June. And it is a demand that is resonating across the continent. Until recently, any proposal to “save” Europe was regarded sympathetically, albeit with skepticism about its feasibility. Today, the skepticism is about whether Europe is worth saving.

The European idea is being driven into retreat by the combined force of a denial, an insurgency, and a fallacy. The EU establishment’s denial that the Union’s economic architecture was never designed to sustain the banking crisis of 2008 has resulted in deflationary forces that delegitimize the European project. The predictable reaction to deflation has been the insurgency of anti-European parties across the continent. And, most worrying of all, the establishment has responded with the fallacy that “federation-lite” can stem the nationalist tide.

It can’t. In the wake of the euro crisis, Europeans shudder at the thought of giving the EU more power over their lives and communities. A eurozone political union, with a small federal budget and some mutualization of gains, losses, and debt, would have been useful in 1999, when the common currency was born. But now, under the weight of massive banking losses and legacy debts caused by the euro’s faulty architecture, federation-lite (as proposed by French presidential hopeful Emmanuel Macron) is too little too late. It would become the permanent Austerity Union that German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble has sought for years. There could be no better gift to today’s “Nationalist International.”

Simply put, progressives need to ask a straightforward question: Why is the European idea dying? The answers are clear: involuntary unemployment and involuntary intra-EU migration.

Involuntary unemployment is the price of inadequate investment across Europe, owing to austerity, and of the oligopolistic forces that have concentrated jobs in Europe’s surplus economies during the resulting deflationary era. Involuntary migration is the price of economic necessity in Europe’s periphery. The vast majority of Greeks, Bulgarians, and Spaniards do not move to Britain or Germany for the climate; they move because they must.

Life for Britons and Germans will improve not by building electrified border fences and withdrawing into the bosom of the nation-state, but by creating decent conditions in every European country. And that is precisely what is needed to revive the idea of a democratic, open Europe. No European nation can prosper sustainably if other Europeans are in the grip of depression. That is why Europe needs a New Deal well before it begins to think of federation.

In February, the DiEM25 movement will unveil such a European New Deal, which it will launch the next month, on the anniversary of the Treaty of Rome. That New Deal will be based on a simple guiding principle: All Europeans should enjoy in their home country the right to a job paying a living wage, decent housing, high-quality health care and education, and a clean environment.

Unlike Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s original New Deal in the 1930s, a European New Deal must be realized without the tools of a functioning federation, relying instead on the EU’s existing institutions. Otherwise, Europe’s disintegration will accelerate, leaving nothing in its wake to federate.

The European New Deal should include five precise goals and the means to achieve them under existing EU treaties, without any centralization of power in Brussels or further loss of sovereignty:

· Large-scale green investment will be funded by a partnership between Europe’s public investment banks (the European Investment Bank, KfW, and others) and central banks (on the basis of directing quantitative easing to investment project bonds) to channel up to 5% of European total income into investments in green energy and sustainable technologies.

· An employment guarantee scheme to provide living-wage jobs in the public and non-profit sectors for every European in their home country, available on demand for all who want them. On condition that the scheme does not replace civil-service jobs, carry tenure, or replace existing benefits, it would establish an alternative to choosing between misery and emigration.

· An anti-poverty fund that provides for basic needs across Europe, which would also serve as the foundation of an eventual benefits union.

· A universal basic dividend to socialize a greater share of growing returns to capital.

· Immediate anti-eviction protection, in the form of a right-to-rent rule that permits homeowners facing foreclosure to remain in their homes at a fair rent set by local community boards. In the longer term, Europe must fund and guarantee decent housing for every European in their home country, restoring the model of social housing that has been dismantled across the continent.

Both the employment scheme and the anti-poverty program should be based on a modern version of an old practice: public banking for public purpose, funded by a pragmatic but radical currency reform within the eurozone and the EU, as well as in non-EU European countries. Specifically, all seigniorage profits of central banks would be used for these purposes.

In addition, an electronic public clearing mechanism for deposits and payments (outside the banking system) would be established in each country. Tax accounts would serve to accept deposits, receive payments, and facilitate transfers through web banking, payment apps, and publicly issued debit cards. The working balances could then be lent to the fund supporting the employment and anti-poverty programs, and would be insured by a European deposit insurance scheme and deficits covered by central bank bonds, serviced at low rates by national governments.

Only such a European New Deal can stem the EU’s disintegration. Each and every European country must be stabilized and made to prosper. Europe can survive neither as a free-for-all nor as an Austerity Union in which some countries, behind a fig leaf of federalism, are condemned to permanent depression, and debtors are denied democratic rights. To “take back our country,” we need to reclaim common decency and restore common sense across Europe.

Μία Νέα Συμφωνία για τη σωτηρία της Ευρώπης

Άρθρο του Γιάνη Βαρουφάκη για το ThePressProject.gr

«Δεν με νοιάζει τι θα κοστίσει. Πήραμε τη χώρα μας πίσω!» Αυτό είναι το περήφανο μήνυμα που ακούγεται σε όλη την Αγγλία μετά το δημοψήφισμα για το Brexit τον περασμένο Ιούνιο. Πρόκειται για ένα αίτημα που αναπτύσσεται σε όλη την ήπειρο. Μέχρι πρόσφατα, κάθε πρόταση για τη «σωτηρία» της Ευρώπης αντιμετωπιζόταν συμπαθητικά, παρά τον σκεπτικισμό για την εφαρμοσιμότητα της. Σήμερα, ο σκεπτικισμός αφορά το εάν η Ευρώπη αξίζει να σωθεί.

Η ευρωπαϊκή ιδέα οδηγείται σε υποχώρηση λόγω των συνδυαζόμενων δυνάμεων της άρνησης, της εξέγερσης και της πλάνης. Η άρνηση του ευρωπαϊκού κατεστημένου να παραδεχθεί ότι η οικονομική αρχιτεκτονική της Ε.Ε. δεν ήταν σχεδιασμένη για να αντέξει την τραπεζική κρίση του 2008 είχε ως αποτέλεσμα αποπληθωριστικές δυνάμεις που απονομιμοποιούν το ευρωπαϊκό οικοδόμημα. Η προβλέψιμη αντίδραση στον αποπληθωρισμό ήταν η εξέγερση αντιευρωπαϊκών κομμάτων σε όλη την ήπειρο.

Και, το πιο ανησυχητικό απ’όλα, το κατεστημένο απάντησε ότι η «μικρή ομοσπονδιοποίηση» μπορεί να αποκρούσει το εθνικιστικό κύμα.

Δεν μπορεί. Από το ξεκίνημα της ευρωπαϊκής κρίσης, οι Ευρωπαίοι ανατριχιάζουν στη σκέψη να δώσουν στην Ε.Ε. περισσότερη εξουσία στις ζωές και τις κοινότητές τους. Μία πολιτική ένωση της Ευρωζώνης, με μικρό ομοσπονδιακό προϋπολογισμό και κάποιο διαμοιρασμό των κερδών, εξόδων και χρέους θα ήταν χρήσιμη το 1999, όταν γεννήθηκε το κοινό νόμισμα. Αλλά τώρα, υπό το βάρος τεράστιων τραπεζικών εξόδων και χρεών που προκλήθηκαν από τη λανθασμένη αρχιτεκτονική του ευρώ, η μικρή ομοσπονδιοποίηση (όπως προτάθηκε από τον υποψήφιο για τη γαλλική προεδρία Εμανουέλ Μακρόν) είναι πολύ λίγη, πολύ αργά. Θα είχε ως αποτέλεσμα τη μόνιμη Ένωση Λιτότητας, την οποία ο Γερμανός υπουργός Οικονομικών, Βόλφγκανγκ Σόιμπλε επιθυμεί εδώ και χρόνια. Δεν θα μπορούσε να υπάρξει καλύτερο δώρο στη σημερινή «Εθνικιστική Διεθνή».

Για να το θέσω απλά, οι προοδευτικοί πρέπει να θέσουν ένα ευθύ ερώτημα: Γιατί η ευρωπαϊκή ιδέα πεθαίνει; Οι απαντήσεις είναι ξεκάθαρες: ακούσια ανεργία και ακούσια μετανάστευση εντός της Ε.Ε.

Η ακούσια ανεργία είναι το αποτέλεσμα των ανεπαρκών επενδύσεων στην Ευρώπη, λόγω της λιτότητας, και των ολιγοπωλιακών δυνάμεων που έχουν συγκεντρώσει τις θέσεις εργασίας στις πλεονασματικές οικονομίες της Ευρώπης κατά τη διάρκεια της αποπληθωριστικής εποχής. Η ακούσια μετανάστευση είναι το αποτέλεσμα των οικονομικών αναγκών στην ευρωπαϊκή περιφέρεια. Η συντριπτική πλειοψηφία των Ελλήνων, Βουλγάρων και Ισπανών δε μετακομίζουν στη Βρετανία ή τη Γερμανία για το κλίμα. Μετακομίζουν γιατί πρέπει.

Οι ζωές των Βρετανών και των Γερμανών δε θα βελτιωθούν με το χτίσιμο ηλεκτρικών φραχτών και με την υποχώρηση στο δόγμα του έθνους – κράτους, αλλά με τη δημιουργία αξιοπρεπών συνθηκών σε κάθε ευρωπαϊκή χώρα. Και αυτό ακριβώς είναι που χρειάζεται για να αναγεννηθεί η ιδέα της δημοκρατικής, ανοιχτής Ευρώπης. Κανένα ευρωπαϊκό έθνος δεν μπορεί να αναπτυχθεί βιώσιμα αν οι υπόλοιποι Ευρωπαίοι υποφέρουν από ύφεση. Για το λόγο αυτό, η Ευρώπη χρειάζεται μία Νέα Συμφωνία πολύ πριν αρχίσει να σκέφτεται την ομοσπονδιοποίηση.

Το Φεβρουάριο, το κίνημα DiEM 25 θα καταθέσει μία τέτοια Ευρωπαϊκή Νέα Συμφωνία, την επέτειο της Συνθήκης της Ρώμης. Αυτή η Νέα Συμφωνία θα βασίζεται σε έναν απλό οδικό κανόνα: Όλοι οι Ευρωπαίοι θα πρέπει να απολαμβάνουν στη χώρα τους το δικαίωμα σε εργασία με βιώσιμο μισθό, αξιοπρεπή στέγαση, υψηλής ποιότητας υπηρεσίες υγείας και εκπαίδευσης και καθαρό περιβάλλον.

Αντίθετα με την πρωτότυπη Νέα Συμφωνία του Φραγκλίνου Ρούζβελτ τη δεκαετία του 1930, η Ευρωπαϊκή Νέα Συμφωνία θα πρέπει να γίνει πραγματικότητα χωρίς τα εργαλεία μίας λειτουργικής ομοσπονδίας, αλλά βασιζόμενη στους υπάρχοντες θεσμούς της Ε.Ε. Αλλιώς, η αποσύνθεση της Ευρώπης θα επιταχυνθεί, μην αφήνοντας στο πέρασμα της τίποτα για να ομοσπονδιοποιηθεί.

Η Ευρωπαϊκή Νέα Συμφωνία θα πρέπει να περιλαμβάνει πέντε συγκεκριμένους στόχους και τους τρόπους για να επιτευχθούν αυτοί, στο πλαίσιο των ήδη υπαρχόντων ευρωπαϊκών θεσμών, χωρίς κανένα συγκεντρωτισμό εξουσιών στις Βρυξέλλες ή άλλες απώλειες εθνικής κυριαρχίας:

Οι πράσινες επενδύσεις μεγάλης κλίμακας θα χρηματοδοτηθούν από μία συνεργασία μεταξύ των τραπεζών δημοσίων επενδύσεων της Ευρώπης (Ευρωπαϊκή Τράπεζα Επενδύσεων, KfW και άλλες) και κεντρικές τράπεζες (στη βάση της ποσοτικής χαλάρωσης για επενδυτικά ομόλογα) για να μετατραπεί το 5% του συνολικού ευρωπαϊκού εισοδήματος σε επενδύσεις πράσινης ενέργειας και βιώσιμων τεχνολογιών.

Ένα σύστημα εγγύησης της εργασίας που θα παρέχει θέσεις εργασίας με βιώσιμους μισθούς σε δημόσιους και μη κερδοσκοπικούς τομείς για κάθε Ευρωπαίο, στη χώρα γέννησης του, διαθέσιμες για όλους όσοι τις επιθυμούν. Με την προϋπόθεση ότι το σύστημα δε θα αντικαταστήσει θέσεις εργασίας δημοσίων υπαλλήλων ή υπάρχουσες παροχές, θα δημιουργήσει μία εναλλακτική στην επιλογή μεταξύ μιζέριας και μετανάστευσης.

Ένα ταμείο κατά της φτώχειας που θα ικανοποιεί τις βασικές ανάγκες σε όλη την Ευρώπη και θα λειτουργεί επίσης ως βάση για μία επόμενη ένωση επιδομάτων.

Ένα καθολικό βασικό μέρισμα για την κοινωνικοποίηση μεγαλύτερου μέρους των αυξανόμενων εσόδων που επιστρέφουν στο κεφάλαιο

Άμεση προστασία από τις εξώσεις, με τρόπο που θα επιτρέπει στους ιδιοκτήτες που αντιμετωπίζουν έξωση να παραμείνουν στα σπίτια τους σε ένα δίκαιο ενοίκιο που θα αποφασίζεται από τις τοπικές κοινότητες. Μακροπρόθεσμα, η Ευρώπη θα πρέπει να χρηματοδοτεί και να εγγυείται για αξιοπρεπή στέγαση για κάθε Ευρωπαίο στη χώρα γέννησής του, αποκαθιστώντας το μοντέλο της κοινωνικής στέγασης που έχει αποσυναρμολογηθεί σε όλη την ήπειρο.

Και το σύστημα εργασίας και το πρόγραμμα κατά της φτώχειας θα πρέπει να βασίζονται σε μία σύγχρονη έκδοση μίας παλιάς πρακτικής. Δημόσιο τραπεζικό σύστημα για δημόσιο συμφέρον, χρηματοδοτούμενο από μία ρεαλιστική αλλά ριζοσπαστική νομισματική μεταρρύθμιση εντός της Ευρωζώνης και της Ε.Ε., όπως επίσης και σε χώρες εκτός της Ε.Ε. Ειδικότερα, όλα τα κυριαρχικά έσοδα των κεντρικών τραπεζών θα χρησιμοποιούνται γι αυτούς τους σκοπούς.

Επιπλέον, σε κάθε χώρα θα πρέπει να θεσπιστεί ένας ηλεκτρονικός δημόσιος μηχανισμός για καταθέσεις και πληρωμές (εκτός του τραπεζικού συστήματος). Οι φορολογικοί λογαριασμοί θα λειτουργούν για να δέχονται καταθέσεις, να αποδέχονται πληρωμές και να διευκολύνουν μεταφορές μέσω web banking, εφαρμογών για πληρωμές και χρεωστικών καρτών. Τα έσοδα που θα δημιουργηθούν, θα χρησιμοποιηθούν για τη χρηματοδότηση του ταμείου που θα υποστηρίζει την εργασία και τα προγράμματα κατά της φτώχειας και θα ασφαλίζονται από ένα ευρωπαϊκό σύστημα προστασίας των καταθέσεων, ενώ τα ελλείμματα θα καλύπτονται από ομόλογα κεντρικών τραπεζών, εκδιδόμενα με χαμηλό επιτόκιο από τις εθνικές κυβερνήσεις.

Μόνο μία Ευρωπαϊκή Νέα Συμφωνία μπορεί να σταματήσει την αποσύνθεση της Ε.Ε. Κάθε ευρωπαϊκή χώρα θα πρέπει να σταθεροποιηθεί και να ευημερήσει. Η Ευρώπη δεν μπορεί να επιβιώσει ούτε ως ελεύθερη για όλους ούτε ως Ένωση Λιτότητας, στην οποία κάποιες χώρες, πίσω από ένα φύλλο συκής για ομοσπονδιοποίηση, καταδικάζονται σε μόνιμη ύφεση και οι χρεωμένοι στερούνται δημοκρατικών δικαιωμάτων. Για «να πάρουμε πίσω τη χώρα μας» πρέπει να ξανακερδίσουμε κοινή αξιοπρέπεια και να επαναφέρουμε την κοινή λογική σε όλη την Ευρώπη.

Η διαρκής κρίση της Ελλάδας

Άρθρο του Γιάνη Βαρουφάκη για το Project Syndicate – απόδοση στα ελληνικά ThePressProject.gr

Από το καλοκαίρι του 2015, η Ελλάδα δεν βρίσκεται (συνήθως) στη διεθνή ειδησεογραφία, αλλά όχι επειδή η οικονομική της κατάσταση έχει σταθεροποιηθεί. Μια φυλακή δεν είναι ενδιαφέρουσα εάν οι κρατούμενοι υποφέρουν σιωπηλά. Μόνο όταν οι κρατούμενοι οργανώσουν μια εξέγερση και οι αρχές προσπαθούν να την ελέγξουν, τότε εμφανίζονται τα ειδησεογραφικά συνεργεία.

Η τελευταία εξέγερση σημειώθηκε κατά το πρώτο εξάμηνο του 2015, όταν οι Έλληνες ψηφοφόροι απέρριψαν τη συσσώρευση νέων δανείων πάνω στον όγκο του ήδη μη βιώσιμου χρέους, μια κίνηση που θα παρέτεινε την πτώχευση της Ελλάδας και στο μέλλον, ενώ θα προσποιοόταν ότι αυτή έχει ξεπεραστεί. Και ήταν σε αυτό το σημείο που η Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση και το Διεθνές Νομισματικό Ταμείο- με την προσέγγιση «παράτασης και προσποίησης» τους να κινδυνεύει- διέλυσαν την «Ελληνική Άνοιξη» και επέβαλαν ακόμα ένα ανεξόφλητο δάνειο σε μια χρεοκοπημένη χώρα. Έτσι, ήταν μόνο θέμα χρόνου πριν επανέλθει το πρόβλημα.

Εν τω μεταξύ, η προσοχή στην Ευρώπη έχει μετατοπιστεί προς το Brexit, τον ξενοφοβικό δεξιό λαϊκισμό στην Αυστρία και τη Γερμανία και το συνταγματικό δημοψήφισμα της Ιταλίας, το οποίο έριξε την κυβέρνηση του Ματέο Ρέντσι. Σύντομα, η προσοχή θα μετατοπιστεί και πάλι, αυτή τη φορά προς το ετοιμόρροπο πολιτικό κέντρο της Γαλλίας. Αλλά, να μην ξεχνάμε ότι η βλακώδης διαχείριση της κρίσης χρέους της Ευρώπης ξεκίνησε στην Ελλάδα. Μια μικρή χώρα μπροστά στα μεγαλεπήβολα σχέδια στην Ευρώπη έγινε ένα πείραμα μιας στρατηγικής που θα μπορούσε να παρομοιαστεί με έναν έντονο χιονιά. Οι επακόλουθες χιονοστιβάδες υπονομεύουν από τότε τη νομιμότητα της ΕΕ.

Το πρόβλημα με την Ελλάδα είναι πως όλοι λένε ψέματα. Η Ευρωπαϊκή Επιτροπή και η Ευρωπαϊκή Κεντρική Τράπεζα ψεύδονται όταν ισχυρίζονται ότι το «πρόγραμμα» για την Ελλάδα μπορεί να λειτουργήσει εφ’ όσον η ελληνική κυβέρνηση ακολουθήσει τις οδηγίες τους. Η Γερμανία ψεύδεται όταν επιμένει ότι η Ελλάδα μπορεί να ανακάμψει χωρίς ουσιαστική ελάφρυνση του χρέους, μέσω μεγαλύτερης λιτότητας και διαρθρωτικών μεταρρυθμίσεων. Η σημερινή κυβέρνηση ΣΥΡΙΖΑ λέει ψέματα όταν επιμένει ότι ουδέποτε συμφώνησε σε ανέφικτους δημοσιονομικούς στόχους. Και, τελευταίο αλλά όχι λιγότερο σημαντικό, το ΔΝΤ λέει ψέματα όταν οι αξιωματούχοι του προσποιούνται ότι δεν είναι υπεύθυνοι για την επιβολή των στόχων αυτών στην Ελλάδα.

Όταν τόσα πολλά ψέματα- με τόσο πολύ πολιτικό κεφάλαιο να επενδύεται στη διαιώνιση τους – ενώνονται, ο διαχωρισμός τους απαιτεί ένα άμεσο χτύπημα, παρόμοιο με αυτό του Αλεξάνδρου όταν έκοψε τον γόρδιο δεσμό. Αλλά ποιος θα υψώσει το σπαθί;

Κατά τραγικό τρόπο, η λύση του προβλήματος είναι προφανής και εξαιρετικά απλή. Το ελληνικό κράτος έγινε αφερέγγυο περίπου έναν χρόνο μετά την έκρηξη της παγκόσμιας οικονομικής κρίσης του 2008. Ενάντια σε κάθε λογική, το ευρωπαϊκό κατεστημένο, περιλαμβανομένων των διαδοχικών ελληνικών κυβερνήσεων και του ΔΝΤ, επέκτεινε το μεγαλύτερο δάνειο στην ιστορία προς την Ελλάδα με τέτοιους όρους που εγγυώνται μια μείωση του εθνικού εισοδήματος σε τέτοιο επίπεδο που δεν έχει παρατηρηθεί από τη Μεγάλη Ύφεση. Για να συγκαλύψουν τον παραλογισμό αυτής της απόφασης, προστέθηκαν νέα δάνεια που βασίζονται σε ακόμα μεγαλύτερη λιτότητα μέσω της περικοπής των μισθών.

Όταν κάποιος βρίσκει τον εαυτό του σε έναν λάκκο, η απλούστερη λύση είναι να σταματήσει το σκάψιμο. Αντ’ αυτού όμως, οι δυνάμεις της Ευρώπης, η ελληνική κυβέρνηση και το ΔΝΤ κατηγορούν ο ένας τον άλλο για το ποιος οδήγησε τους Έλληνες σε μια άβυσσο.

Πρόσφατα, ο Πολ Τόμσεν, ο διευθυντής του Ευρωπαϊκού Τμήματος του ΔΝΤ και ο Μορίς Όμπστφελντ, επικεφαλής οικονομολόγος του, διαμαρτυρήθηκαν σε μια από κοινού γραμμένη δημοσίευση σε μπλογκ, λέγοντας ότι «δεν είναι το ΔΝΤ που απαιτεί περισσότερη λιτότητα». Το φταίξιμο βρίσκεται αλλού. «Αν η Ελλάδα συμφωνεί με τους Ευρωπαίους εταίρους της για φιλόδοξους δημοσιονομικούς στόχους», υποστήριξαν , «μην επικρίνετε το ΔΝΤ για το ότι επιμένει στη λιτότητα όταν ζητάμε να δούμε τα απαιτούμενα μέτρα για να γίνουν τέτοιοι στόχοι αξιόπιστοι».

Ο Τόμσεν και ο Όμπστφελντ έχουν εν μέρει δίκιο. Ο Έλληνας πρωθυπουργός, Αλέξης Τσίπρας, δεν είχε καμία δουλειά να συμφωνήσει στους καταστρεπτικούς δημοσιονομικούς στόχους που απαιτήθηκαν από τη Γερμανία και την ΕΕ όταν ήμουν υπουργός Οικονομικών. Οι ισχυρισμοί του διαδόχου μου ότι η κυβέρνηση ποτέ δεν δέχτηκε τους στόχους, είναι ανειλικρινείς. Όπως πολύ καλά γνωρίζει, παραιτήθηκα κυρίως επειδή τον Απρίλιο του 2015 ο Τσίπρας συμφώνησε σε αυτούς τους στόχους πίσω από την πλάτη μου. Οι πρώην συνεργάτες μου τα βάζουν με αυτόν που φέρνει τα κακά νέα, το ΔΝΤ σε αυτήν την περίπτωση, για το ότι οι στόχοι στους οποίους συμφώνησαν απαιτούν ακόμα μεγαλύτερη λιτότητα.

Είναι επίσης αλήθεια ότι το ΔΝΤ συστηματικά και ορθώς, επέκρινε αυτούς τους στόχους. Αλλά αυτό που ο Τόμσεν αμελεί να αναφέρει είναι ότι, χωρίς τη δικιά του ανοχή και την ανοχή της Γενικής Διευθύντριας του ΔΝΤ Κριστίν Λαγκάρντ, η Ευρωπαϊκή Επιτροπή δεν θα ήταν σε θέση να επιβάλει αυτούς τους στόχους. Και αυτό είμαι σε θέση να το ξέρω: εκπροσώπησα την Ελλάδα στις συνεδριάσεις του Eurogroup (το οποίο περιλαμβάνει τους υπουργούς Οικονομικών των χωρών της ευρωζώνης), όταν συνέβη αυτό.

Ο Τόμσεν φαίνεται να έχει τη συναίσθηση της ευθύνης του να σταματήσει τη νομιμοποίηση της ασφυξίας που γίνεται στην ελληνική οικονομία υπό γερμανικής καθοδήγησης. Σε μια τηλεφωνική συνομιλία τον Μάρτιο με την Ντέλια Βελκουλέσκου, επικεφαλής της ελληνικής αποστολής του ΔΝΤ, ο Τόμσεν εξήγησε τι πρέπει να συμβεί αν η Γερμανία επιμείνει στη διάλυση της Ελλάδας μέσω της μη χορήγησης μιας ελάφρυνσης του χρέους. Σύμφωνα με την απομαγνητοφώνηση της κλήσης (που κυκλοφόρησε από το WikiLeaks), ο Τόμσεν πίστευε ότι οι ευρωπαίοι ηγέτες δεν θα ασχοληθούν με το ζήτημα μέχρι την ολοκλήρωση του δημοψηφίσματος για το Brexit στη Μ. Βρετανία.

Σύμφωνα με τον Τόμσεν: «Εμείς τότε λέμε, “Κοιτάξτε κ. Μέρκελ, αντιμετωπίζετε ένα ερώτημα, πρέπει να σκεφτείτε τι έχει περισσότερο κόστος: να συνεχίσετε χωρίς το ΔΝΤ και η Ομοσπονδιακή Βουλή να πει ‘Το ΔΝΤ δεν συμμετέχει;’ ή να επιλέξετε την ελάφρυνση του χρέους που πιστεύουμε ότι χρειάζεται η Ελλάδα για να μας κρατήσει ενεργούς;” Σωστά; Αυτό είναι το πραγματικό ζήτημα».

Η Βελκουλέσκου απάντησε ότι «για το καλό των Ελλήνων και όλων των υπολοίπων, θα ήθελα αυτό να συμβεί νωρίτερα παρά αργότερα». Αλλά αυτό δεν συνέβη γιατί ο Τόμσεν και η Λαγκάρντ ποτέ δεν τόλμησαν να στριμώξουν την Μέρκελ. Αντιθέτως το ΔΝΤ συνεχίζει να κατηγορεί άλλους, παρέχοντας παράλληλα στη Γερμανία πολιτική κάλυψη για να συνεχίζει να πιέζει ασφυκτικά την Ελλάδα.

Αλλά, όπως επεσήμανε έξυπνα η Βελκουλέσκου, οι επιπτώσεις επηρεάζουν και «όλους τους υπόλοιπους». Οι ανησυχητικές εξελίξεις στην Ιταλία, τη Γαλλία και ακόμη και στη Γερμανία αποτελούν μια άμεση συνέπεια του ελληνικού φιάσκου. Η Ελλάδα όμως είναι το άμεσο θύμα και είναι επομένως ευθύνη της ελληνικής κυβέρνησης να κόψει το γόρδιο δεσμό, κηρύσσοντας μονομερώς μορατόριουμ για όλες τις αποπληρωμές μέχρι να συμφωνηθεί μια ουσιαστική αναδιάρθρωση του χρέους και λογικοί δημοσιονομικοί στόχοι.

Οι ψηφοφόροι της Ελλάδας έδωσαν δυο φορές στους ηγέτες τους την εντολή να κάνουν ακριβώς αυτό: μια φορά όταν εξέλεξαν την κυβέρνηση ΣΥΡΙΖΑ, τον Ιανουάριο του 2015, και πάλι εκείνον τον Ιούλιο σε δημοψήφισμα. Για χάρη της Ελλάδας- και της Ευρώπης- οι αρχές πρέπει να λένε τα πράγματα με το όνομά τους.

February 13, 2017

Open Letter to the editor of The Times: Your Athens correspondent has done it again!

Dear Sir,

A day after one of your able journalists interviewed me in London, with a view of composing a piece for your newspaper (which I suppose is forthcoming), my attention was drawn to a separate piece that I am sure slipped inadvertently into your newspaper through your various filters. Its defamatory and wholly made-up title tells the whole story: “Varoufakis ‘funnels thousands to offshore bank account’“.

This is not the first time your excellent newspaper has been led down the garden path by the same Athens correspondent. Back in October, Anthee Carassava reported that I was charging $60,000 per speech and that I was demanding payment through some Oman-based account. Nothing could be further from the truth. For the purposes of making that clear, and in the interests of full transparency, I did something that no politician has ever done: I published on my website the list of every talk I had given and the precise fee that I had received, demonstrating that the vast majority of my talks are free (indeed that, for some of them, I cover my own transport costs).

Today, the same TIMES correspondent, exhibiting an astonishing lack of journalistic ethics, attempted to exploit the furore over the Panama papers to submit to you exactly the same defamatory piece, without even mentioning that it was a re-print of her October tall tale, complete with the same fictitious figure and the same fictitious Oman-based account.

As I am sure that you are not aware of the above, I am addressing this open letter to you to protect you from defamatory pieces submitting by this particular Athens correspondent.

Finally, so that there is no smidgeon of doubt, let met state it for the record that:

I have never had an offshore bank account or used one such account, in Oman or anywhere else on the planet

No one (investigative reporter or authority) has ever claimed that I have had or used such an account

I have never used any method for reducing the tax I pay to the Greek authorities

Convinced that, after having read the above, I trust that you will take the necessary steps to reign in unscrupulous reporting from your Athens correspondent.

Regards

Yanis Varoufakis

February 10, 2017

DiEM25 unveils its ‘European New Deal: An economic agenda for European Recovery’

To mark its first anniversary DiEM25 has today published a summary of its White Paper entitled ‘European New Deal: An economic agenda for European Recovery’. The full White Paper will be launched on the 25th March 2017 in Rome, in the context of the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome. Click here for a pdf.

February 9, 2017

DiEM25 unveils its ‘European New Deal: An economic agenda for European Recovery’

Yanis Varoufakis's Blog

- Yanis Varoufakis's profile

- 2451 followers