Margot Note's Blog, page 26

December 21, 2020

Mastering Archival Projects

I've compiled some of my best post posts on archival management. I love being a consultant who can help organizations fund, set up, or expand their archives programs.

Interested in learning more? Explore my services.

December 14, 2020

The Professionalization of Archivists: An Overview

The role of archivists has always been in flux, responding to the needs of the information world and providing the unique skill sets that librarians, historians, and records managers may understand but do not hold. Archivists are colleagues to librarians, historians, and records managers, but are a distinct class unto themselves.

Archival BeginningsArchives were first developed from historical societies at the end of the eighteenth century, research libraries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the rise of universities, which have employed many archivists. Archives have always reflected the culture and technology of the times. For instance, historical societies were established as part of the historical manuscripts tradition, which collected public records as well as personal papers. This happened in part because the development of the postal service created growth in correspondence.

Further DevelopmentsIn the United States, the archival profession first laid roots in the late 1890s within the American Historical Association (AHA), forming the Conference of Archivists in 1909. In the early 19th century, the fields of history and archives advanced enough that one organization could not serve both. In the mid-thirties, the National Archives and the Society of American Archivists were formed, providing a professional identity to archivists. This was an important vocational moment because archivists were formally differentiating themselves from historians.

A Maturity of the FieldThe rise of social history, new repositories, and professional associations fueled an influx of archivists in the 1970s. From the 1970s on, another crucial development of the profession was standardization. Collection distinctiveness is the point where librarians and archivists differ professionally. Although libraries may house rare or special collections, most of their holdings are published monographs, which have copies around the world with similar cataloging. Archivists, however, preserve and protect unique records, without counterparts. Archivists routinely manage information that crosses many technological and administrative barriers during its life cycle. Since archival content differs at each repository, archivists must employ some type of standardization or best practices to provide access and give meaning to the collections.

As the technology of the 20th century allowed more records to be kept, there also became the need to distinguish between records managers and archivists. Archivists work with the permanently valuable records of an organization that no longer needs them for business purposes. Archivists make records available to researchers to document the history of the organization as well as the larger society. Records managers work with records no longer needed for everyday use, which may be temporary, awaiting a destruction date in congress with local, state, and federal law, or permanent, awaiting transfer to an archives. Traditionally, records managers do not grant access to these records for research because the organization still has legal control of them, thus controlling access to the records.

Advocating for the ProfessionDespite the distinct professional identity that archivists hold, the profession is not as well known as similar professions like librarianship. Archivists face complex communication challenges within and outside of their organizations. The absence of a standard university degree and a distinct career path affects how others with limited knowledge of the field perceive them. The Society of American Archivists has, for example, has done considerable work to give archivists the tools to advocate for themselves, including developing tips for creating an elevator speech to explain our roles to others. Archivists have discovered the importance of sharing the excitement of what they do to those that would benefit from using archival materials, if only they knew about their benefits. Archivists continue to convey the enthusiasm, stimulation, and fulfillment they feel as they work with records of enduring value.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

December 7, 2020

Revising a Paper’s Organization

Students often focus on revising the details of their papers, when revising the organization of their papers should be the priority. Once the substance of your paper’s argument has been developed, make sure that readers will find the paper coherent.

Check the following:

Do key terms run through your paper? Do you introduce the main points later in the essay but don’t introduce them earlier in the paper? Does your paper seem to wander?

Is the beginning of each section and subsection clearly signaled? Would inserting headings or extra spaces between major sections make readers more easily understand your points?

Does each major section begin with words that signal how that section relates to the one before it? Are their transitions that show why one section comes after the other? Does that paper flow?

Does each section relate to the whole and to your argument? What is the purpose of the section? Is it necessary? If not, consider cutting it.

Is the point of each section stated in a brief introduction or conclusion?

Do terms that unify each section run through it? What are the major themes of the section that make it distinct? If two sections are the same, consider combining them. If they are too similar, you may need to edit them more so that they are different.

Scan your paragraphs. Do they flow in the right order? Do some paragraphs be broken down further to clarify a point and be easier to read? Does the first sentence, preferably, or the last state the point of the paragraph?

What do you do to revise the organization of your papers?

November 30, 2020

Autocategorization in Records Management

The ability to automatically categorize records is very powerful, but autocategorization is not well understood and needs to be executed properly if it is to succeed. Autocategorization “attempts to assign electronic records to either predefined file structures or to self-defined categories through computer-based processes” (Lubbes 2003, 60). Its objective is to understand and recognize concepts that group similar documents together, yet exclude documents that are not relevant to search queries. It is designed to facilitate contextual searching by delineating the relationships that exist within and between topics in content. When properly established, autocategorization software learns to file documents in either a predefined taxonomy or user-defined categories.

Santangelo (2009) notes that accurate classification allows organizations to “retain [records], place legal holds on it, and make reasonable disposition decisions about it, thus helping to minimize the significant legal costs and risks associated with continuing to store it unnecessarily” (23). Chester (2004) notes that autocategorization’s deployment with other types of material is different than with records management, which “requires great accuracy because the cost of misfiling a record is greater than when sorting press releases or magazine articles” (17). Further complicating matters, file plans are more complex than those found in other applications and are externally determined by the organization, rather than derived from the documents themselves (Chester 2004).

Autocategorization uses either pattern-based systems or rule-based systems. Pattern-based systems use word patterns and concepts to associate the records with the file categories. In essence, the system learns how to distinguish between concepts using sophisticated algorithms. The four basic techniques are k-nearest neighbor, Bayesian, neural network, and support vector machines (Lubbes 2003). Other techniques include “clustering of set of documents based on similarities,…sophisticated linguistic inferences, the use of pre-existing sets of categories, and seeding categories with keywords” (Reamy 2002, 17).

Rule-based systems depend on user-defined sets of rules to decipher the concepts contained in the records. The system then parses documents, determines their concepts, and assigns them to categories based on the rule set. An advantage of rule-based systems is that even if there is an error in filing, it will be consistent unlike filing by humans.

Unless other variables are incorporated as a cross-reference, rule-based systems may classify unrelated documents with similar terms together. Stephens (2007) notes that “The trend is to combine multiple methods to categorize the corpus of documents to increase the accuracy and relevancy of grouping similar documents” (158).

The fundamental problem of records management is getting documents into the system, and it is unrealistic, slow, and costly to expect records creators to classify documents themselves (Medina, et al. 2006). Autocategorization addresses adequate participation and accuracy, the two basic requirements of enterprise content management. However, before undertaking an autocategorization project, RIM professionals must determine if autocategorization is suited to the organization’s documents, their file plan, whether it can be accurate enough to be cost-effective against other types of classification schemes, and whether it will require unacceptable resources to train the system. Medina et al. (2006) advise, “Plan to make use of [autocategorization] in the long term, and introduce it in a later phase of your deployment. Most importantly, make sure to do a test drive against your organization’s documents and requirements” (17). Bock (2002) continues, “There is no commercially oriented benchmark for determining the effectiveness of one particular text-analysis solution or another. Thus, a company choosing between [a product] and its competitors has to do extensive comparisons on its own to determine the costs and benefits of alternative approaches” (as cited in Lubbes 2003, 69).

Even with the best autocategorization system, human intervention is needed to define rules and monitor results. Documents that the system does not understand are reviewed by the RIM professional to decide if the system’s proposed assignments are appropriate or if they should be modified (Chester 2004). Additionally, periodic review is necessary to not only see if the system remains on target, but also because new categories will be introduced and existing categories may “drift” from their original target (Chester 2004, 17).

Autocategorization software works best for organizations with a large influx of documents, preferably well written by professionals, that need to be categorized into a fairly shallow or general fie plan, or else have very highly developed and specialized vocabularies, such as the pharmaceutical or legal industry. However, with careful planning and training of the system, autocategorization can successfully sort records into buckets for later retrieval by RIM professionals.

Works Cited

Bock, G. (2002). Meta tagging and text analysis from Clearforest, identifying and organizing unstructured content for dynamic delivery through digital networks. Patricia Seybold Group.

Chester, B. (March/April 2004). Auto-categorization and records management. Infonomics 16-18.

Lubbes, R. K. (October 2001). Automatic categorization: How it works, related issues, and impacts on records management. Information Management Journal 38-43.

Lubbes, R. K. (March/April 2003). So you want to implement automatic categorization? Information Management Journal 60-69.

Medina, R., Gaffaney, D., & L. Andrews. (July/August 2006). Autocategorization: One key component for enterprise records management. Infonomics 15-17.

Reamy, T. (November 2002). Auto-categorization: Coming to a library or intranet near you! EContent 17-22.

Santangelo, J. (November/December 2009). Rise of the machines: The role of text analytics in record classification and disposition. Information Management 22-26.

Stephens, D. O. (2007). Records management: Making the transition from paper to electronic. Lenexa, KS: ARMA International.

November 23, 2020

Deaccessioning in the Archives

Deaccessioning of archival holdings, the process in which an archives removes accessioned materials from its holdings, is one potential result of reappraisal. Ideally, deaccessioning would occur regularly in the course of archival collections management practices. As a routine procedure, it would allow archival institutions to remove materials determined to be unworthy of retention.

The Society of American Archivists defines deaccessioning as “the process by which an archives, museum, or library permanently removes accessioned materials from its holdings.” This definition separates decisions made before materials are acquired and entered into a repository’s recordkeeping system from those made after materials officially become part of the repository’s holdings.

Deaccessioning is more often discussed in the library world than in the field of archives. Weeding a book collection is more pragmatic for librarians, and they assume other copies of books exist elsewhere. Librarians don’t have to worry about potential donor implications of deaccessioning—or the unique, one-of-a-kind nature of archival materials.

Why Should Archivists Deaccession?There are several valid reasons why archivists may wish to deaccession parts of their holdings. Materials may no longer be useful or relevant to the repository. This decision, of course, implies that a conscious assessment based on current collecting policies and research demands has been performed. Materials may be deaccessioned if they cannot be properly stored, preserved, or made available. They could also be deaccessioned if they no longer retain their physical integrity, identification, or authenticity. A choice in favor of deaccessioning may come because the information is duplicated in other collections. Lastly, the materials may be part of a collection housed at another repository, so combining the two is a logical step.

Types of Deaccessioning OptionsDeaccessioning consists of several options. Materials could be:

Discarded or destroyed

Transferred to another repository

Returned to the donor

Sold, with the proceeds used to benefit the future acquisitions of the repository

Deaccessioning in Real LifeWhen I think about deaccessioning, I’m reminded of a client from several years ago. The college archives lacked both an acquisition policy and a collection policy. Archival acquisition happened when faculty and staff members retired or moved offices, or during campus renovations. Over time, the archives became known as the place to send old stuff on campus.

When reviewing the materials in the collection, we found boxes of popular magazines documenting John F. Kennedy’s presidency and the Apollo 11 moon landing. Although the materials were interesting and historical, they had no connection to the college, lacked a deed of gift, and would not fit into the future collecting policy. I advised that the magazines should be deaccessioned and considered for sale on eBay. Since the magazines were in excellent condition, the small amount of money raised could be used support archival activities.

I also cautioned that just like the weeding of library collections, deaccessioning items in the archives can be a sensitive area, especially for those who don’t understand the importance of maximizing work on set parameters Before deaccessioning any items, I noted that the collection policy should be clear about the proper deaccessioning procedure and include the necessary signoffs.

Deaccessioning Done RightOnce the decision is made, the implementation of deaccessioning activities has its own set of requirements. For example, the decisions involved in deaccessioning must be consistent with the repository’s mission, collecting policy, and appraisal guidelines. In addition, written policies, procedures, and documentation are required throughout the deaccessioning process. Selling the materials instead of transferring them raises other questions that should be addressed by policy. Materials with monetary value require special consideration, rather than simply being moved to another home.

The activities of deaccessioning should be performed in a systematic manner. When appropriate, the donor should be notified that such action is taking place to alleviate public relations problems. Transparency throughout the archival collections management process, including deaccessioning, strengthens donor relations. Deaccessioning done right allows archival repositories to concentrate their limited resources on collections with the most enduring value to researchers and society as a whole.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

November 16, 2020

Painting an Information Map

I recently watched R.I.P.: Rest in Pieces: A Portrait of Joe Coleman, a 1997 documentary about the painter and performance artist. Coleman paints detailed, overwhelming, and chaotic scenes in a similar style to Hieronymus Bosch. Coleman's work is categorized as "outsider art," a condescending way of saying an artist is talented, but without the usual pretension of being an artiste.

Although many of Coleman's paintings are autobiographical, he often paints pictures of historic figures that interest him, like Hank Williams or Houdini. The paintings are visual data maps, displaying an incredible amount of biographical information about his subjects. He wears magnifying glasses as he paints minuscule illustrations within his paintings using a single-hair paintbrush. Coleman describes it as, "trying to find more and more information inside each tiny brushstroke." Fellow painter Robert Williams says, "Not only do you get a remarkably well done piece of art with Joe Coleman, but you get a brilliant interpretation of history of whatever subject he would like to express."

Coleman collects information about his subjects with an academic's zeal. He says, "I go to the library, or bookstore, or do a book search. I go through my own collection of books which is pretty extensive. I research the subject without any preconceived composition. Once I start, I keep painting until the whole surface is covered and then that’s it. I can’t even do research on another painting until I completely finish the one I’ve started." For him, a painting categorizes the information he gathers, stating, "The painting orders it, clarifies it, borders it. It puts boundaries on something that is so overwhelming and disturbing to me."

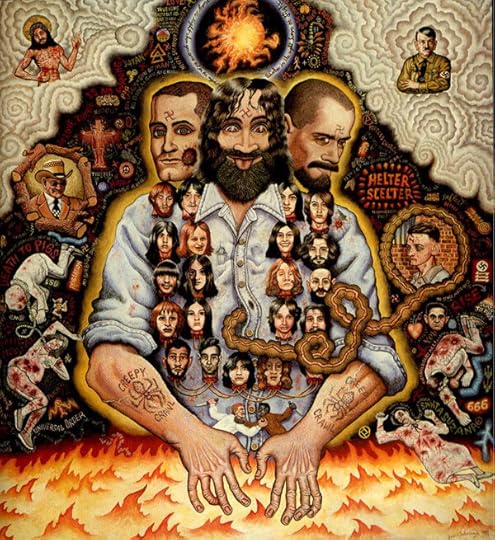

I chose Coleman's "Portrait of Charles Manson" (1988) to illustrate how he creates effective information maps for two reasons. It was the largest biographical image I could find on the web; it reveals some of the tiny illustrations within, but not all. Also, I am well-versed on the Manson Family, allowing me to better "read" the information presented in the painting. Manson has called Coleman, "a caveman in a space ship," which I believe is a compliment!

Manson is displayed as a Christ-like figure, poised between heaven and hell. Manson may have belonged to the Process Church, which worshiped both Christ and Satan. Manson often referred to himself as Jesus ("Man's Son"). A bloodied, reborn Jesus appears in the upper left (the right hand of Manson, making him God,) while Hitler, another figure Manson admired, is to the upper right.

The trinity of faces are Manson as a young hood, Manson as the Death Valley guru on acid, and Manson as he returned to prison. Manson wears the heads of his Family members as garland like Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction and protection. The unmistakable lolling tongue is also a Kali trait.

The Family member portraits are mostly taken from mugshots in Vincent Bugliosi's true crime classic Helter Skelter, and, moving counterclockwise from the top left, I recognize Steven Grogan aka Clem, Bobby Beausoleil, Ruth Ann "Ouisch" Moorehouse, Mary Brunner, Charles "Tex" Watson (on acid when arrested, hence the funny face), Susan Atkins, Stephanie Scram, Leslie Van Houten, Juan Flynn, Bill Vance, Catherine "Gypsy" Share, Sandra Good, Catherine Gillies, Harold True, Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, Robert Reinhard, Patricia Krenwinkel, Bruce Davis, [Unknown], and Nancy Pitman/Brenda McCann.

The man framed in wood to the left is is George Spahn, the elderly man who owned the ranch that the Family lived on. Looped in intestines to the right is Manson as a young, abused boy in reform school.

The most famous Manson Family victims are (to the left) actress Sharon Tate and hairstylist Jay Sebring. Coffee heiress Abigail Folger and her Polish boyfriend Voytek Frykowski are on the right. They are represented as how they looked in death, including Sebring's face covered, with rope around his neck leading to Tate.

Although most of the illustrations are too small to see, "Rise," "Death to Pigs," and "Helter Scelter" are recognizable in red, replicating what the killers wrote in blood at the Tate/LaBianca crime scenes.

Manson believed that the Beatles encoded their music with messages and their song "Helter Skelter" alluded to an apocalyptic race war between whites and blacks, which Manson and his Family would emerge the victors to repopulate the earth. (Hence the fighting figures in the bottom of the painting). Although Helter Skelter was an important part of the Manson Family mythos, the drug-addled hippies never seemed to spell it right. "Helter Scelter" was written at Spahn Ranch; "Healter Skelter" was written on the LaBianca's refrigerator in their blood.

The forearm tattoos refer to "creepy crawls," a Family practice of breaking into the homes of sleeping people, rearranging their furniture, and stealing things: basically test runs for murder.

Interestingly enough, the Manson girls created their own autobiographical information map: an embroidered jacket for Manson that illustrated important Family moments. When they shaved their heads while Manson was on trial, the girls added their hair as fringe. They sent the jacket to Manson in prison, and, hardened criminal that he was, he cut it into pieces and gave them to other prisoners so they wouldn't steal it from him.

Explore Joe Coleman's website, including a gallery of his paintings with detailed views.

November 9, 2020

Archival Program Management

The management of the archival program connects to the hosting institution’s mission; it cannot be an afterthought. Unfortunately, management is an area where archivists traditionally lack experience, but, recently, most LIS programs require students to take at least one management course.

Archivists usually reside in organizations whose primary mission is something else, which can isolate them. Archivists often lack control over matters related to budgets or facilities; they need to be able to find and explain costs so resource allocators can understand them.

In addition, operations and daily practices and procedures often preoccupy archivists. Because there’s usually a lack of resources, keeping the archives functioning and making the collections available becomes more urgent than long-term planning and quality management.

A Coordinated EffortCoordination depends on the size and nature of the institution, but there’s always a level of service duplication within institutions. Functions such as public relations, procurement, facilities management, and human resources are often centralized. Other duties, more central to the archives, such as IT and conservation, often cross institutional lines. Sometimes there’s also coordination across functional areas, such as when a centralized office manages cataloging outside of the archives. In some institutions, there are multiple archives with differing levels of independence.

In addition, professional boundaries have grown blurry because of the overlap of archives with records management, knowledge management, and IT. Executives making decisions often misunderstand what exactly archivists do, and why their duties are distinct from allied professions.

Placement = PowerThe organization’s mission statement should outline the purpose of the archives, and placement will determine that focus and scope.

Proper placement within the organization is essential. Where is the archives department found within the organization’s hierarchy? To whom does the archivist report? Placement begins with differentiating between what occurs within the archives and the larger institution. These lines differ according to the nature of the institution.

For example, within a university setting, the archives can be part of the library, the registrar’s office, the President’s office, or the legal or public relations departments. The library is the most common location, where archives can be part of special collections or exist as a separate unit. Archivists often report to library administrators who may know little about the archives.

Within the government, for instance, the archives could be considered part of the cultural wing, another organizational structure, or part of administrative information services. Some state archives relate to the state library; others are separate agencies. Some report to the Secretary of State.

Staffing and Archival LaborSurveys of archival repositories show that many archivists work in small departments, with one to three full-time employees. For “lone arrangers,” it becomes clear how difficult it is to run an archives without help. This responsibility makes it important to prioritize, but it also means that archivists often get limited management experience.

Archivists managing multiple staff members face challenges, such as balancing professional and support staff. Academic institutions have categories of support staff, including students. Historical societies and public libraries may have volunteers, which bring their issues.

With multiple staff members, outline reporting structures and responsibilities. The tendency is to assign support staff to the desk and to assign processing responsibilities to non-professional staff, which from a quality point of view is illogical.

Work responsibilities also relate to the separation of functions. Does one person do collection development? Is there a separate reference department, or does everyone sit on the desk? What about dealing with special format materials?

Other staffing issues relate to hiring criteria, professional development, and promotion. Institutions often require the ALA-accredited MLIS. Some places value certification. It’s challenging to get the human resources team to understand the needs for hiring in an archives—where job titles can vary wildly—let alone to offer a competitive wage

Management Done RightManagement assures that everyone has clear responsibilities and enough information and support to conduct assigned tasks. Delegation is crucial. In addition, the department needs regular staff meetings, frequent communication, and written guidelines for staff members and researchers. Over time, the profession has focused more on improving the management and administration of archival departments, which will make them more functional, more initiative-taking, and more responsive to contemporary research needs.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

November 2, 2020

The Social Implications of Data Mining

This post explores how data mining, a rapidly changing discipline of new technologies and concepts, affects the individual right to privacy. As technology becomes more enmeshed in the daily lives of individuals, information on their activities is being stored, accessed, and used. Society is developing a new definition of privacy in this information environment, with few laws specifying privacy protection with electronic transmission and storage. Collecting and using data without limitations is unacceptable, but norms have changed enough that data collection has been accepted without much opposition.

Data collection and privacy issues are in the forefront of international discussions. Interest groups who believe that voluntary restraints are sufficient struggle against privacy advocates who argue that controls must be backed by legislation to be effective. Advocacy groups are alarmed about the government’s potential for invading privacy, but data collection by businesses has expanded that concern to public and private sectors.

Under the guise of protecting public interest, government and business are revising regulations to expand use of data once considered private such as bank records and medical files. Advocacy groups counter this trend by encouraging the need for participation in any personal data collection and distribution.

With so much data already stored and transmitted, privacy advocates feel it is no longer possible to control the process. This lack of confidence indicates the need to strengthen watchdog efforts, if privacy rights are to be retained. What are ethical information practices that can satisfy data mining users and privacy advocates? Can data mining principles be developed to dictate how personal data can be protected in terms of quality, purpose, use, security, participation, and accountability?

Data Mining DefinedThe information age has enabled many organizations to gather large amounts of data, but its usefulness is negligible if knowledge cannot be extracted. Data mining attempts to answer this need by connecting the fields of databases, artificial intelligence, and statistics. It has steadily evolved since the 1960s.

Data mining is the discovery of actionable patterns in large amounts of data using statistical and artificial intelligence tools (Berry & Linoff, 1997). More specifically, it is “the process of nontrivial extraction of implicit, previously unknown and potentially useful information such as knowledge rules, constraints, and regularities from data stored in repositories using pattern recognition technologies as well as statistical and mathematical techniques” (Lee & Siau, 2001, 41). Data mining can also be defined as “the analysis of (often large) observational data sets to find unsuspected relationships and to summarize the data in novel ways that are both understandable and useful to the data owner” (Hand, Mannila, & Smyth, 2001, 1). Observational data—rather than experimental—refers to data that has already been collected for an original purpose, such as bank transactions. As a secondary use, data mining harvests this information to find actionable patterns.

There are two main categories of data mining tasks: description and prediction (Mena, 2004). In description, the goal is to discover patterns by seeking out variables common to different individuals or groups that exhibit certain characteristics. Examples of descriptive methods include association rule discovery and clustering. Association rule discovery finds connections among sets of items or objects in database, which implies the likelihood of the occurrence of several events (Agrawal, Imielinski, & Swami, 1993). Clustering creates a grouping from objects; objects that belong to the same cluster are similar to each other and differ from objects in other clusters (Berkhin, 2001). Prediction is used to make statements about the unknown based upon the known; it can forecast the future or explain the present (Weiss & Indurkhya, 1998).

Privacy DefinedThe term “privacy” is used frequently in ordinary language, yet it has no single definition (Kemp & Moore, 2007). The concept of privacy has broad historical roots in sociological and anthropological discussions about how it is preserved in various cultures. Some argue that the values of privacy are distinctly Western, culturally relative, and not universally accepted (Brey, 2009). Globalization and the emergence of the Internet has created an international community, which requires a moral system. German theologian Hans Küng stresses the need for global ethics, a shared moral framework agreed upon by all cultures, especially because actions in cyberspace are not local (Küng, 2001, as cited in Brey, 2009). How global ethics will mold a universal definition of privacy has yet to be seen.

The historical use of the word “privacy” is not uniform, and confusion over its meaning, value, and scope remains. “Outside of narrow academic circles, constructing an exact definition of privacy has proven less important than addressing concrete claims for privacy protection. Seclusion, solitude, anonymity, confidentiality, modesty, intimacy, secrecy, autonomy, and reserve—securing these social goods is what privacy is all about” (Allen, 2006, 1).

Different conceptions of privacy typically fall into six categories: the right to be let alone, limited access to the self, secrecy, control of personal information, personhood, and intimacy (Solove, 2002). In this paper, privacy refers to the right of users to conceal their personal information and have some degree of control over the use of any personal information disclosed to others. Data mining techniques should be effective without disposing of the need to preserve privacy, one of the basic values of modern free societies.

Data Mining ProblemsWhen used responsibly, data mining can be beneficial to society. The explosion of data generated by new technologies, decreasing costs of computer storage, and increasing capabilities of search tools have made data mining an important instrument of government anti-terrorism efforts since September 11, 2001.

Additionally, data mining is important for business because it reveals information about past performance that can predict future functioning. It exposes emerging trends from which the company might profit and allows for statistical predictions, groupings, and classifications of data. Data mining tools allow businesses to make proactive, knowledge-driven decisions and answer business questions that were previously too time-consuming to resolve. While some values of data mining are evident, the ethical repercussions of its usage have been slower to emerge.

For example, the government accesses an extraordinary volume of personal data to search for terrorist activities. Privacy statutes fail to limit the government’s access to personal data, and they have been amended in the post-9/11 world to reduce them further. The Fourth Amendment, the constitutional guarantee of individual privacy, has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to not apply to routine data collection, accessing data from third parties, or sharing data, even if illegally gathered. Data mining leads to false positives of innocent people being investigated, which can have serious consequences (Quinn, 2009). Privacy advocates believe that data mining exposes ordinary people to ever more scrutiny by authorities while skirting legal protections designed to limit the government’s collection and use of personal data.

Data mining that allows companies to identify their best customers could easily be used by businesses to categorize vulnerable customers such as the elderly, poor, or sick. Unscrupulous businesses could use the information to offer people inferior deals or to discriminate against certain populations. One person’s file may be confused with another’s, causing an individual with good credit to be rejected for a loan. Although this problem may be corrected in time, the mistake will have negatively affected the individual’s life. Some companies compile data, use it for their own purposes, and then sell it for profit. Other organizations do not have enough security measures in place to protect against unauthorized access. Since information about customers has become a commodity, businesses have increased incentives to acquire information from customers, making it more difficult to protect their privacy (Rosenberg, 2000, as cited in Quinn, 2009).

Another area where data mining presents ethical problems relates to data mining for health-related issues of employees. In the past, employers have used data mining to determine the frequency of sicknesses and possible illnesses that may result. This information is useful when purchasing health insurance for an organization, but there is the potential that the findings may be used when making hiring decisions. For example, an employer may make the decision not to hire an employee because they are likely to have certain expensive health problems. Similarly, insurance companies could refuse to sell policies those that they identified as high risk for carrying diseases.

Data mining tools also make inference easier (Clifton & Marks, 1996). “Inference is the process of users posing queries and deducing unauthorized information from the legitimate response that they receive” (Thuraisingham, 2005). Thuraisingham (2005) points out that inference problems, which mainly deal with confidentiality, have parallels to problems with privacy. While data mining is an important tool for many applications, the information extracted should be used ethically.

Data Mining Problems and the InternetThe Internet has enabled privacy threats to occur on a broader scale. Cavoukian (1998) notes that one of the purposes of data mining is to map Internet patterns. When considering privacy threats related to data mining, it is important to explore how the Internet facilitates data mining and exacerbates privacy issues.

According to Slane (1998), the four privacy issues in data mining with the Internet are security, accuracy, transparency, and fairness. Before the Internet, access to databases was reasonably limited to a few authorized people. However, the Internet makes it easier for more people to access databases. Without strong access control, private information can be disclosed, manipulated, and misused. Accuracy is also a problem because with the growth of the Internet, data mining involved large amounts of data from a variety of sources. The more databases involved, the greater the risk that the data is inaccurate and the more difficult it is to clean the data, which may lead to errors and misinterpretation. Transparency becomes difficult because people cannot correct data about themselves, and they cannot express concern with the use of their information. When data mining, no one can predict what kinds of relationships or patterns of data will emerge. It is questionable that data subjects are being treated fairly when they are unaware that personal data about them is being mined.

Ethics and Data MiningEthical inquiry provides a basis for choosing proper actions based on rational principles and sound arguments. With this in mind, the ethics of data mining will be examined using utilitarianism and Kantianism.

“Act utilitarianism is the ethical theory that an action is good if its net effect (over all affected beings) is to produce more happiness than unhappiness” (Quinn, 2009, 75). In other words, an action is right from ethical point of view, if the sum total of utilities produced by that act is greater than the sum total of utilities produced by any other act the agent could have performed in its place. Utilitarianism holds that in the final analysis only one action is right: that one action whose net benefits are greatest by comparison to the net benefits of other alternatives. Both the immediate and foreseeable future costs and benefits that the alternative will provide for individuals must be taken into account as well as any significant indirect effects. The alternative that produces the greatest sum total of utility must be chosen as the ethically appropriate course of action. Utilitarianism also has the advantage of being able to explain why we hold that certain types of activities are generally morally wrong, such as lying, while others are generally morally right. Actions are never always right or always wrong; it depends on the circumstances.

From a utilitarian viewpoint, data mining is ethical because it enables corporations to minimize risk and increase profits, helps the government strengthen security, and benefits society with technological advancements. The invasion of personal privacy and the risk of having people misuse the data would be considered a small downside. Based on this theory, since the majority benefits from data mining, data mining is ethical.

Kantianism is the belief that “people’s actions ought to be guided by moral laws, and that these moral laws were universal” (Quinn, 2009, 69). The first formulation categorical imperative is “act only from moral rules that you can at the same time will to be universal moral laws” (Quinn, 2009, 70). The second formulation categorical imperative is “act so that you always treat both yourself and other people as ends to themselves and never only as means to an end” (Quinn, 2009, 71). In other words, people should not use others to achieve their goals. Kant set forth that “it is morally obligatory to respect every person as a rational agent” (Davis, 1993, 211). Kantianism requires individuals to consider the impact of their actions on other persons and to modify their actions to reflect the respect and concern they have for others.

Using Kantianism, data mining is unethical because users advance their own interests without regard for people’s privacy—using them as a means to an end.

Privacy Preserving Data MiningSince the ethical nature of data mining is questionable, privacy preserving data mining may be a suitable solution, which benefits data mining users and individuals concerned with their right to privacy. Privacy preserving data mining refers to data mining techniques that protect sensitive data while allowing useful information to be extracted from the data set. Many schemes have been proposed for privacy preserving data mining, but there is no paradigm for research. “Although there is an extensive pool of literature that addresses many aspects of both privacy and data mining, it is often unclear as to how this literature relates and integrates to define an integrated privacy preserving data mining research discipline” (Fu, Nemati, & Sadri, 2007, 48). Rakesh Agragwal at IBM Almaden, Johannes Gehrke at Cornell University, and Christopher Clifton at Purdue University are forerunners to further developing privacy protecting data mining by modifying algorithms, maintaining some level of privacy (Thuraisingham, 2005). The field is young, but promising.

Vaidya and Clifton (2004) argue that data mining does not inherently threaten privacy and discuss two strategies in which data can reveal patterns without revealing private information: randomization and secure multiparty computation (SMC). Randomization arbitrarily samples from datasets that share certain characteristics with the original data. SMC allows parties to cooperate in data mining, without revealing data to parties that do not already know them.

Additionally, algorithms can be used to extract data patterns without directly accessing the original data (Kargupta, Liu, Datta, Ryan, & Sivakumar, 2003). Other approaches are based on perturbation, which adds random noise from a known distribution to the privacy sensitive data, and the data miner uses the reconstructed distribution for data mining purposes (Liu, Kantarcioglu, & Thuraisingham, 2008). Sensitive data can be masked in a number of statistical ways, yet still provide workable information to data mining users.

Social Implications of Data MiningSociety is redefining privacy to conform to concepts compatible with the information era. Individuals, governments, and corporations are trying to find common ground, balancing the individuals’ right to privacy and government’s and industry’s need to disseminate information necessary to best serve public interests.

The increasing use of data mining tools in both the public and private sectors raises concerns regarding the potentially sensitive nature of the data being mined. The utility gained from data mining comes into conflict with an individual’s right to privacy. Privacy preserving data mining solutions achieve a paradox: enabling data mining algorithms to use data without accessing it. Thus, the benefits of data mining may be enjoyed, without compromising privacy.

Works Cited

Agrawal, R., Imielinski, T., & Swami, A. (1993). Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases. SIGMOD Record, 22(2), 207.

Allen, A. L. (2006). Privacy, definition of. In W. G. Staples (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Privacy A-M (pp. 393-403). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Berkhin, P. (2001) Survey of clustering data mining techniques. Retrieved February 17, 2019, from: http://www.accrue.com/products/rp_clu...

Berry, M., & Linoff, G. (1997). Data mining techniques for marketing, sales, and customer support. New York: Wiley.

Brey, P. (2009). Is information ethics culturally relative? In E. Eyob (Ed). Social implications of data mining and information privacy: Interdisciplinary frameworks and solutions (pp. 1-14). Hershey, PA: ICI Global.

Cavoukian, A. (1998). Data mining: Staking a claim on your privacy. Information and Privacy Commissioner. Retrieved March 1, 2019, from http://www.ipc.on.ca/images/Resources/datamine.pdf

Clifton, C., & Marks, D. (1996). Security and privacy implications of data mining. Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD Conference Workshop on Research Issues in Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery.

Davis, N. (1993). Contemporary deontology. In P. Singer (Ed)., A Companion to ethics (pp. 205-218). Oxford: Blackwell.

Fu, L., Nemati, H., & Sadri, F. (2007). Privacy-preserving data mining and the need for confluence of research and practice. International Journal of Information Security and Privacy, 1(1), 47-64.

Hand, D., Mannila, H., & Smyth, P. (2001). Principles of data mining. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kargupta, H., Liu, K., Datta, S., Ryan, J., & Sivakumar, K. (2003). Homeland security and privacy sensitive data mining from multi-party distributed resources. The IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems: Vol. 2. (pp. 1257-1260).

Kemp, R., & Moore, A. D. (2007). Privacy. Library Hi Tech, 25(1), 58-78.

Küng, H. (2001). A global ethic for global politics and economies. Hong Kong: Logos and Pneuma Press.

Lee, S. J., & Siau, K. (2001) A review of data mining techniques. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 100(1), 41-46.

Liu, L., Kantarcioglu, M., & Thuraisingham, B. (2008). The applicability of the perturbation based privacy preserving data mining for real-world data. Data & Knowledge Engineering, 65(1), 5-21.

Mena, J. (2004). Homeland security techniques and technologies. Hingham, MA: Charles River Media.

Quinn, M. J. (2009). Ethics for the information age. (3rd ed.). New York: Pearson Education.

Rosenberg, A. (2000). Privacy as a matter of taste and right. In E. Frankel, Jr., F. D. Miller & J. Paul (Eds)., The right to privacy (pp. 68-90). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Slane, B.H. (1998). Data mining and fair information practices: Good business sense. Retrieved March 1, 2019, from: http://www.privacy.org.nz/data-mining-and-fair-information-practices-good-business-sense/

Solove, D.J. (2002). Conceptualizing privacy. California Law Review, 90, 1087-1156.

Thearling, K. (n.d.). An introduction to data mining: Discovering hidden value in your data warehouse. Retrieved February 17, 2019, from: http://www.thearling.com/text/dmwhite...

Thuraisingham, B. (2005). Privacy-preserving data mining: Developments and directions. Journal of Database Management, 16(1), 75-87.

Vaidya, J., & Clifton, C. (2004). Privacy-preserving data mining: Why, how and when. IEEE Security and Privacy, 19-27.

Weiss, S. M., & Indurkhya, N. (1998). Predictive data mining: A practical guide. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

October 26, 2020

The Problem with Digital Image Banks

Historical photographic collections in archives, libraries, and museums have been influenced by the two billion dollar a year global stock photography industry. The images, used in marketing, advertising, editorials, multimedia products, and websites, are filed at an agency that negotiates licensing fees on the photographer’s behalf in exchange for a percentage, or in some cases, owns the images outright. Pricing is determined by the size of audience or readership, how long the image is to be used, country or region where the images will be used, and whether royalties are due to the image creator or owner. The images are generic and decontextualized with flat, rich color and blank backgrounds, acting as “the wallpaper of consumer culture” (Frosh 2003, 1). Image banks “distort the nature of the imagery, treating them as if photography were a kind of universal Esperanto” (Ritchen 1999, 90). Cartier-Bresson notes that an image bank “will never match the work of an author. On one side is a machine: on the other is a living and sensitive being” (Dorfman 2002, 60).

Getty Images and Corbis, the two largest digital image banks, represent 70% of the images used in advertising and marketing (Frosh 2003). Getty Images was co-founded by Jonathan Klein and Mark Getty, grandson of oil tycoon J. Paul Getty. Corbis is owned by Microsoft founder Bill Gates. In some countries, Getty’s 25% market share would be considered illegal (Machin 2004). Machin (2004) writes that stock photography companies are changing visual perceptions of “the photograph as witness, as record of reality, to one which emphasizes photography as a symbolic system and the photograph as an element of layout design, rather than as an image which can stand on its own” (319). He continues:

We should be concerned about the effect of this increasingly stylized and predictable world on audience expectations of what the visual representation of the world should look like. We should be concerned about the fact that we no longer flinch when we see a posed, processed, stylized, colour-enhanced, National Geographic image of a woman and child taken from Getty and placed on a page in The Guardian for a documentary feature on the Kashmir conflict (335).

More worrisome for information professionals is the fact that image banks have also acquired historical photographic archives. Getty contains the Eastman Kodak Image Bank, the Hulton Picture archives, and the National Geographic image collection, among others (Ramamurthy 2009). Corbis absorbed the Sigmund Freud archives and the photo archives of UPI, the defunct news wire service (Aalto 2008; Dorfman 2002). It also bought the Bettmann Archive in 1995, which contains more than 16 million photographs, one of the world’s largest private depository of images. Batchen (2001) notes that many of the images owned by Corbis are historically significant:

Remember Malcolm X pointing out over his crowd of listeners, the airship Hindenburg exploding in the New Jersey sky, that naked Vietnamese child running toward us after being burned by napalm, Churchill flashing his V-for-victory sign, Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, Patty Hearst posing with her gun in front of the Symbionese Liberation Army banner, LBJ being sworn into office aboard Air Force One beside a blood-spattering Jackie? Corbis offers to lease us electronic versions of them all. It offers to sell us, in other words, the ability to reproduce our memories of our own culture, and therefore of ourselves (150).

Corbis has digitized only the previously top best-selling 225,000 images. The rest are stored in an Iron Mountain underground cold storage facility, inaccessible to researchers. Lister (2009) notes that “In these processes of acquisition and selection a kind of digital ‘editing of history’ is at stake” (344). By neither digitizing images nor making them accessible for research, scholars are deprived of the cultural heritage of visual records.

Works Cited

Aalto, B. (2008). Industry in transition. Applied Arts 23(2), 10.

Batchen, G. (2001). Each wild idea: Writing, photography, history. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dorfman, J. (July/August 2002). Digital dangers: The new forces that threaten photojournalism. Columbia Journalism Review 60-63.

Frosh, P. (2003). The image factory: Consumer culture, photography and the visual content industry. New York: Berg.

Lister, M. (2009). Photography in the age of electronic imaging. In L. Wells (Ed.), Photography: A critical introduction. (pp. 311-344). London: Routledge.

Machin, D. (2004). Building the world’s visual language: The increasing global importance of image banks in corporate media. Visual Communication 3(3), 316-336.

Ramamurthy, A. (2009). Spectacles and illusions: Photography and commodity culture. In L. Wells (Ed.), Photography: A critical introduction. (pp. 205-256). London: Routledge.

Ritchen, F. (1999). In our own image: The coming revolution in photography. New York: Aperture.

October 19, 2020

Investing in Institutional Archives

When we think of archival repositories, we frequently think of academic archives or large historical societies. We often forget about business or institutional archives, because they are usually closed to the public.

Institutional archives fall into many categories: government at all levels, corporations, not-for-profit organizations, colleges and universities, and religious institutions. These organizations establish archives for several reasons and develop archival collection policies.

Why Invest in Archives?The first motive for establishing an archives program is efficiency. Organizations recognize the need to both preserve and find valuable information. Organizations have accountability issues and must be able to retrieve documents for information purposes, as well as for evidence. Unchecked and uncontrolled growth of records is unwieldy and costly.

The second aim is responsibility, which is like efficiency in some respects. Records are created and hold administrative, legal, and fiscal value, and organizations need to document their many functions. As organizations have become more significant and multifaceted, these functions are harder to track.

A sense of history is another reason. Manuscript repositories share this characteristic as well, but for in-house archives, there is often pride regarding organizational accomplishments, and a desire to promote those achievements. Archives are often established on a significant anniversary or event. Sometimes in business, the looming retirement of the founder, for example, brings attention to the need to preserve the history of the corporation.

The last major reason is publicity, which is connected to the previous point. Organizations want to be able to promote what they do, and often that requires documentation that the archives would have retained. Smart businesses have realized the value of using historical materials for many of their advertisements. Coca Cola, for example, is a leader in this field and promotes its history throughout its website and marketing materials.

I recently stayed at the historic Peabody Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee, a site that has fully embraced their history and use it in their marketing. Along with their world-famous ducks in residence—a tradition they have kept for more than 80 years—they also have a “memorabilia room” on their mezzanine. Inside this smartly appointed area are artifacts and documents displaying their legacy. By using their archival material as a marketing resource, the Peabody has generated so much business for itself and downtown Memphis.

Shared CharacteristicsWhile institutional archives vary in size and complexity, they do share specific features. They have a greater emphasis on provenance and original order than non-institutional archives. Institutions have an inherent structure, reflected in the organizational chart, and the archives reflect that order. Understanding which department created a series of records is crucial, and the filing systems take on more importance than they do in a typical manuscript collection where original order might not exist. Archivists thus must be familiar with the organizational chart and filing systems.

They differentiate between primary and secondary audiences. In some ways, in-house archives are like special libraries in that they serve a specific user group, namely employees of the sponsoring organization. Institutional archives may be open to the public or may help the internal audience. Even the Coca Cola archives, which has a public face, provides public access to a small and defined element of the overall records.

Institutional archives also tend to have different descriptive and reference systems. Since the in-house audience is more circumscribed, the finding aid system does not have to meet the needs of the same broad user groups. In fact, in most cases, the archivist does the searching and retrieving of the information for the requesting employee, providing either information or copies of documents. There is more likely to be an overall structure to the finding aid system rather than separate finding aids for individual collections. The structure of the organization is in and of itself a kind of finding aid, as one can identify which office produced the desired materials. Along similar lines, in-house archives don’t need the same kind of public service system and facilities. Often there is no real reading room.

When I was the head of an archives department at an international nonprofit, I fielded research requests from around the world. Although the archives were closed to the public, I was able to do research for the users and send them digitized records that fulfilled their needs.

The Value of Institutional ArchivesIn my consulting practice, I encounter so many businesses that are interested in preserving their history but don’t know where to start. Although they may be unaware of the archival program options available to them, they are eager to establish archival workflows ad archival collection policies that protect their hard-earned knowledge and history in perpetuity. Embracing the value of their records has inspired them to invest in their archives.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

If you like archives, memory, and legacy as much as I do, you might consider signing up for my email list. Every few weeks I send out a newsletter with new articles and exclusive content for readers. It’s basically my way of keeping in touch with you and letting you know what’s going on. Your information is protected and I never spam.

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook