Margot Note's Blog, page 23

July 26, 2021

8 Secrets to Your Best Academic Performance Ever

I’m an expert in doing well in school.

I was in the top ten academically in high school, and I got As all through my higher education years. I worked full-time during graduate school and while writing my books. I teach a course on Research Methods for graduate students to help them develop skills that will last them through their careers as historians.

I am by no means brilliant. But I am smart enough, work hard, and have developed habits that achieve the best results for me.

I want to share some tips to help you get better grades in less time and with less stress and effort.

A caveat: my suggestions are written primarily for undergraduates in the humanities who attend school in person. Most of what I suggest is transferable to students in high school or graduate school, those who study STEM subjects, and online students.

Befriend a LibrarianI learned at a professional conference recently that a one-hour session with a librarian can save up to nine hours of individual research.

Talk with the staff at your library and develop a rapport with them. People became librarians because they want to help people discover information. Librarians can help in a pinch when you have overdue fines, need a book ordered, or have an obscure research topic.

Before you start a project, talk to a librarian to develop a research plan. A 15-minute conversation will set you on the right path quickly.

At the beginning of the school year, most schools offer bibliographic instruction classes, where a librarian discusses all the sources of information that are available to students. Many classes are in person; some are online. Take advantage of this opportunity before the school year gets underway. The class allows you to see the scope of materials that available to you, so you’ll have a better understanding of where to start your research.

Beyond GoogleA client of mine told me that almost half of their academic library’s budget is devoted to database subscriptions. A chunk of your tuition is put towards scholarly databases; if you only use Google for research, you are throwing away money.

It is possible to do good research on Google, but you would already have to be an excellent researcher. All too often, people only use the results that show up on the first page, which are not always the best.

Instead, use the scholarly databases that your library subscribes to which will give you better quality sources such as peer-reviewed articles and better search options.

Depending on your subject, one or two databases may be the ones that will find the best material. Ask a reference librarian which ones would be the best for your project and how to search within them. Each database offers different options and filters to refine your search.

Develop a Study RoutineAs you mature as a scholar, you will discover what study and research options work best for you. For example, I like to write notes by hand and read them to myself to retain the information better. Through trial and error, I’ve found this method works the best for me.

Set the stage for your best work. What do you like to drink as you study? Do you play music or is it quiet? Where do you like to study? What can you do to maintain your concentration? Do you study best in a group or individually? What time of day works for you?

There’s no single best way to study, only one that syncs up best with your learning style and preferences.

Attend Office HoursIf a professor has office hours, stop by. This is especially important for subjects that may not come easily to you.

As a first-year, I took a 7:00 am Calculus class; I still don’t know what I was thinking. I had a hard time understanding some concepts from class, so I visited my professor during his office hours so we could work through my calculations. I received one-on-one attention, and he became more comfortable teaching me. I did better in class, and I imagine I was graded better—as much as there is some wiggle room in grading a math class—because he knew that I was putting in the extra effort.

Teachers teach, so let them. Take advantage of their wisdom. It’s helpful for them to know what you are struggling with, because you are probably not the only one in class who is having that problem.

Visit the Writing CenterEveryone benefits from writing better and having an editor.

If your campus has a writing center, visit it before your next assignment is due. You’ll be able to work one-on-one with another student to refine your paper. They will pick up on ideas that need more clarification and fix the awkward phrasing and grammatical errors that take away from what you’re trying to express.

Many students come to college without the ability to write well, and professors don’t often have the time to copy-edit your writing. Use your time as a student to develop your writing skills; no matter what career you ultimately land in, being a good writer will always help you.

As an undergraduate, I used to work at the campus writing center. A nursing student began meeting with me because she was having difficulty completing her assignments.

For example, when she read her writing out loud, she inserted words that weren’t on the page. She “wrote” perfectly while speaking, but her written communication was choppy. She didn’t see the omissions until I pointed them out.

It wasn’t easy working with her. Sometimes she was frustrated and angry. Who wouldn’t feel uncomfortable when someone is pointing out your errors? I admired her because she kept on working. We discovered ways to improve her writing while still retaining her unique voice.

After a few weeks, she told me that her professors noticed her progress and her grades jumped. She radiated pride. It was all on her; I was just there to facilitate her growth.

Use the Pomodoro TechniqueFrancesco Cirillo invented a time management system called Pomodoro after the tomato-shaped timer he used to track his work as a student. (“Pomodoro” is Italian for “tomato”).

The methodology is simple. When faced with a large task, break the work down into intervals (called “Pomodoros”) which are interrupted by short breaks. This structure trains your brain to focus and rewards it with a pause.

Typically, a Pomodoro is 25 minutes, and a break is 5 minutes. When you are procrastinating, promise yourself you will complete a Pomodoro. You will be amazed at what you can complete during that period, and you may find yourself eager to complete more Pomodoros.

Learn Editing TricksWhen you are nearing completion of your assignment, print it out. Make your edits on paper, and read it out loud. Editing on screen can catch major errors, but editing on paper reveals minor mistakes.

Reading your assignment out loud allows your ears to find errors that your eyes can’t see. You detect awkward phrasing, misused words, and other quirks. I use text-to-speech readers online discover more issues to correct.

Grammarly, Hemmingway App, and Expresso can also be used to fix grammar and style mistakes. Take their suggestions with a grain of salt; not everything they find needs to be changed.

Practice Self-CareMany schools offer health and wellness programs to their students. Seek professional help if you find yourself overwhelmed by stress, anxiety, or physical or mental problems. Develop ways to stretch yourself academically while also spending time relaxing and recharging.

A friend of mine was in a rigorous architecture school, which required endless hours of working, rendering, and studying. Even during the craziest of deadlines, she took a 20-minute walk daily. She needed that short period to clear her mind before she could continue working.

The most important part of becoming a better scholar is to become a better person, holistically. No grade is worth overworking yourself or becoming unbalanced in life.

July 19, 2021

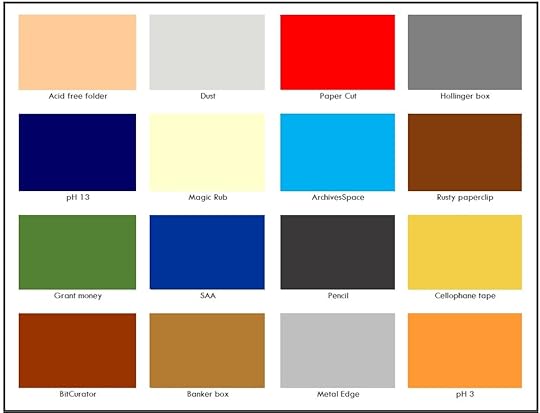

An Archives & Records Management Palette

Some of us remember Carole Jackson’s classic book Color Me Beautiful, which everyone seemed to own in the 1980s. I remember browsing through my mother's copy when I was a child.

The theory is based on four color types: Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter. Each seasonal type depends on the undertone of your skin, hair, and eyes, and your overall tone. I'm a Summer because my coloring is soft, light, and cool.

The swatches in the book made me think of the colors appropriate to archives and records management. Grey, beige, and blue predominate, but occasionally there's a bright splash of red!

July 12, 2021

Project Management as Change Management in Heritage Institutions

Adhering to proven project management practices reduces risk, cuts costs, and improves the success rates of projects. Organizations are likely to nurture a project management culture when they understand the value it brings and how projects drive change. Organizations also recognize that when projects fail, they are less likely to achieve strategic goals. Archives, libraries, and museums should acknowledge the value of people who are resourceful, have strategic insight, and champion knowledge development and transfer as essential to performance improvement. Utilizing project management makes success possible.

Project management is closely tied to change management because projects, by their very nature, cause change. Change management is the implementation of planned alterations to established missions, objectives, or procedures within an organization. It typically refers to the intentional processes undertaken by organizations in response to internal needs, but it may also include strategies for reacting to external events. Lasting change incorporates the mission, goals, and objectives of the institution. Simultaneous changes in structures, systems, and people leads to changes in the culture of the organization. As with project management, change management requires that stakeholders understand the rationale for change and that they are engaged and supportive of new solutions.

Information professionals need to be capable of managing and participating in projects and should be able to anticipate and support the resulting organizational change. Indeed, change management is crucial to the success of projects involving the integration of new information technologies. For example, it is not enough to implement a new content management system and incorporate it into organizational functions. It must also be accepted and applied by the creators and users of documents, which involves the application of change management skills.

Weingand (1997) writes:

Too often, organizational culture is rooted in tradition and habit, and change is often an unwelcome visitor. Yet, change is today’s one constant, and no organization can escape its presence and effects. Whether regarded as an opportunity or as a threat, the specter of change sits on every organization’s board of directors; the library is no exception (7).

In the world in which most information professionals work, innovation and the change that comes as a result have not always been welcomed in organizations focused on maintaining the status quo of previous generations. Memory institutions like libraries, archives, and museums adhere to traditions, which can sometimes make change difficult. Schreiber and Shannon (2001) write:

The hyper speed of change in information services now demands libraries that are lean, mobile and strategic. They must be lean to meet expanding customer expectations within the confines of limited budgets; mobile to move quickly and easily with technological and other innovations; and strategic to anticipate and plan for market changes (36).

Additionally, information professionals work in environments that include complex classification systems, technical infrastructures, and organizational configurations. It is tempting to view these conditions as constraining. However, thinking about organizations structurally overlooks the challenge that is central to the information profession: deploying information services in ways that change the communities libraries, archives, and museums serve. Information professionals are increasingly called upon to facilitate the reconceptualization and redesign of services. As project managers, team members, or stakeholders, information professionals are involved in projects that change organizations.

As a result, Doan and Kennedy (2009) note that information professionals have: come to view change as the means of accomplishing significant goals, recognizing that our organizations must keep pace with user needs, acknowledging that we do indeed have information competitors and that we are part of organizations and therefore must align with larger objectives than our own. It is essential to innovate to continue to be meaningful (349).

Munduate and Media (2009) state similarly, “Organizations will only survive if they have the flexibility to react to the constantly changing demands and if they are adept enough at redirecting, orientating, and exploiting their resources efficiently” (299). Successful projects are one way to create an environment that embraces change as an opportunity, not as a threat.

Present situations in organizations are largely the result of decisions made in the past. Information professionals should not allow themselves to become captives to previous decisions. They must question decisions made in the past and effect changes that would position the organization well in the future. Innovation and the systematic abandonment of obsolete practices is a critical factor in the renewal and growth of memory institutions.

Works Cited

Doan, T., Kennedy, M.L., 2009. Innovation, creativity, and meaning: leading in the Information Age. Journal of Business and Finance Librarianship 14 (4), 348–358.

Munduate, L., Media, F., 2009. Organizational change. In: Tjosvold, D., Wisse, B. (Eds.), Power and Interdependence in Organizations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 299–316.

Schreiber, B., Shannon, J., 2001. Developing library leaders for the 21st century. Journal of Library Administration 32, 35–57.

Weingand, D.E., 1997. Customer Service Excellence: A Concise Guide for Librarians. American Library Association, Chicago.

Project Management for Information Professionals By Margot Note Buy on Amazon Get StartedWork with an archival expert. Learn more about how I might help you by clicking the contact button below.

Contact

July 5, 2021

Strategies for Archival Advocacy

Archives and archivists must promote themselves, their institutions, and their missions to the larger world. Successful advocacy efforts go hand in hand with solid programs that are viewed as assets by others.

The archives world contains a diverse group of individuals and institutions who share a joint mission to procure, preserve, and present records of enduring value. The overall goal of advocacy is to raise the profile of archives. There are several ways that archivists can strengthen the infrastructure of their programs.

Tips and Proven PracticesArchivists can enhance the perception of the quality of their programs. They should highlight their achievements, focus their communications on specific audiences, and raise expectations. They should also find influential allies and secure their involvement on behalf of the program. One way to do this is to find ways to attract people with power to create opportunities.

One way to do so is to establish and maintain awareness and understanding at the highest level of management and governance. Archivists must maintain regular communication channels with senior-level individuals with credibility. Another way is to use external professional expertise for evaluation and ideas. Consultants, subject matter experts, and archivists at similar institutions can provide opinions and advice. Often, people in leadership positions are more likely to understand information from objective outsiders than receive the same message from their staff members.

Seek external funding support from sources beyond the institution of which the archives is a part and internal sources through means beyond the established budgeting system. When seeking outside financial resources, look first for opportunities for program development rather than maximum dollars for basic program support. The goal is to build new initiatives and not just make do; granting agencies may not fund ongoing programs they think the institution should fund, although they will fund startup projects if the institution commits to maintaining them after the granting program is over.

Archivists must advocate for their programs and the issues that influence their programs with knowledge and forethought. They should develop an attractive case statement to articulate the program’s value. They should try to avoid tangential projects, no matter how enticing, unless they believe they will strengthen the program eventually. Unfortunately, it is often hard to say “no” to those in power while also maintaining good relationships with decision-makers within an institution. However, articulating healthy boundaries of what the archives should do is necessary for a successful archives program.

Asking QuestionsTo develop a case for advocacy, archivists should ask themselves the following questions:

What is the goal of advocating for archives? What is to be accomplished?

What are the objectives? Why are they important?

What are the strategies and activities needed do to accomplish the goal?

Who is the target audience?

Why should they care?

In a sentence or two, what is the message?

What data or stories support this message?

Making the CaseIt seems that archivists must continually explain who they are, what they do, and why their work is important. Archivists should not wait until events require advocacy efforts but should instead implement simple advocacy goals and activities into their mission and activities.

Archives witness the past. Records provide evidence and explanation for past actions and present decisions. Archives allow civilized communities to take root and flourish, from promoting education and research to protecting human rights and confirming identity. Archives are unique records and, so, once lost, cannot be replaced. Only through proper identification, care, and comprehensive access can archives’ vital role be fully realized to the benefit of humanity.

Archivists are aware of the societal, institutional, and individual construction of memory and understand the implications of how memory is transmitted over time. This awareness becomes even more critical as collections are represented online. It is also vital for retaining evidence in time and over time, especially through digital preservation processes. Now, more than ever, archives are important to advocate for and protect.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

Get StartedWork with an archival expert. Learn more about how I might help you by clicking the contact button below.

Contact

June 28, 2021

The Future of Image Management

Since its invention more than 150 years ago, photography has revolutionized communication and has provided a technological method for the comprehensive documentation of social and physical landscapes. Since photographic images serve as immediate links to the past and transcend time and place, they provide a valuable visual record of the past century for scholars and non-academic users alike.

Due to photography’s usage as a primary source for pedagogy and research, archives, libraries, and museums holding historical photograph collections have a responsibility to manage them properly and make them available for generations to come. Until the advent of online collections, most historical collections of photography were difficult to access, but as photographic equipment and methods have evolved, so have photographic collections. The digitization of image collections has vastly increased the numbers of images available to researchers through electronic means. The phenomenal growth of digital information in cultural heritage institutions prompts an examination of the nature and importance of hybrid image collections, as technology changes the ways in which users access information and conduct research.

There is a continuing argument within memory institutions and photographic circles that nothing changes with regard to how users evaluate the relevance of a photograph, even if it no longer has a material existence but is stored as digital code. Users continue to view images, whether analog or digital, as indexical representations of the real. Others feel that digital images are pure abstractions with constitutive mutability and manipulation, and that without some physical link to their subjects, they are not ‘real’ photographs. The first approach emphasizes the continuity of the medium, based on the unchanging combination of photographer, camera, and subject. Those who see digitization as the end of photography wish to cling to the traditional, tangible imprint of reality; they blame digitization for the death of photography, for the end of the believability that photography holds as an index, rather than an icon or symbol.

How the nature of photography has changed as a result of digitization remains a matter of discussion. As Batchen (1999) notes:

A singular point of origin, a definitive meaning, a linear narrative: all of these traditional historical props are henceforth displaced from photography’s provenance. In their place we have discovered something far more provocative—a way of rethinking photography that persuasively accords with the medium’s undeniable conceptual, political, and historical complexity (202).

Whatever the conclusion to this debate, it seems clear that digital technology has thoroughly assimilated photography of all kinds, including image collections that will enter the archives, libraries, and museums hereafter. Lipkin (2005) notes that the future holds more questions than answers:

How will [technological] advances change our notion of what photography can or should be? What will happen as modeling software becomes increasingly capable of generating photo-realistic imagery that cannot be distinguished in any way from real life? The only thing we can be sure of is that the human desire to understand the world through representation will propel the process of making images through greater and greater changes in the years to come (10).

Although the fate of photography remains unknown, and technical, social, practical, and theoretical issues continue to emerge, there are several factors that information professionals can depend on as they look to the future of image management. Digital resources will increase significantly and information technology will change rapidly. Research trends will expand and scholars will continue to demand that collections be as inclusive as possible. Intellectual property rights management will also evolve as digital content replaces analog sources. Financial and human resources will be unable to keep pace with demand but should be allocated in the most cost-effective manner to achieve an acceptable balance between the quality of resources and the expenditure of time and money. The sustainability of collections will also continue to be an issue, as digitization is not just about the creation of images, but also about their maintenance and management. As a result of these developments, best practices for access, preservation, and management of image collections will transform as well.

Works Cited:

Batchen, G. (1999). Burning with desire: The conception of photography. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lipkin, J. (2005). Photography reborn: Image making in the digital era. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Managing Image Collections: A Practical Guide (Chandos Information Professional Series) By Margot Note Buy on Amazon Get StartedClick the button below to work with an expert.

Contact

June 21, 2021

Selection Criteria for Digitization

As the world continues to be impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, archival repositories have made more materials available online. Projects to digitize materials began years ago, but since online access is now the only access for many organizations, there has been a renewed interest in making holdings available virtually.

The pandemic pushed organizations to find ways to make their collections more accessible, which often means investing in broader digitization efforts.

Since digitizing everything is unrealistic and expensive, archivists use selection criteria for digitization. In choosing wisely, organizations focus on facets of their collections that are best suited to digitization, make effective use of technology, and meet researchers’ needs. Digitization policies and plans allow institutions to articulate how they will use digitization to support their missions and build consensus about what criteria will guide the choice of projects and the programs’ growth. Archivists build online collections that provide the most research value, sustainable over time. Below are some selection considerations, organized in order of importance.

CopyrightProjects suitable for digitization must have their copyright cleared before proceeding. Collections with copyright owned by the institution, produced by the institution, or in the public domain should receive priority treatment above collections that lack copyright permissions or have unclear copyright agreements. There is no point in an organization spending time, money, and talent to digitize something they cannot post.

Information NeedsCandidates for digitization should meet constituencies’ information needs, who increasingly demand digitized archival and special collections materials for better access. The judgment used for collection development can also evaluate the intellectual quality of items or collections to digitize. Since the cost of digitization projects is so high, the work must focus on digitizing the most useful and unique materials that meet users’ information needs, rather than the long tail of lesser used, less popular, or derivative materials.

UseIf the collections have a high frequency of demand because they meet user information needs, they may qualify for digitization. Suppose visitors have always accessed a physical collection, but items are no longer available because the reading room is closed. In that case, the materials after digitization may be even more useful for remote users.

ValueOrganizations should digitize high-value items for preservation and security. Value is gauged monetarily, by the uniqueness of the material, and its importance to the community served by the institution. The interests of funding agencies or grant providers can also assess value. Archivists should query their stakeholders as to what collections are the most valuable to the organization.

PreservationItems or collections that have preservation problems because of inadequate housing, physical damage, fragility, size, or outdated formats also qualify for digitization. An added benefit is that providing alternative access to the information decreases the handling of original materials, facilitating preservation.

CostsIf physical materials are costly to retrieve, then suitable digital versions may be more cost-effective. Digital access can save money because it reduces the need for employees to supply retrieval services.

Processed CollectionsCollections that are already organized, described, and processed with proper metadata, should be given higher priority than unprocessed collections. In most cases (although not always), processed collections signify that they meet the above criteria for information needs, use, and value. Since the information is already there, digitization is just one more step to increased accessibility.

Wise DecisionsNo repository can digitize everything it owns. Thoughtful decisions arise from assessing the nature and content of materials, their intellectual property rights, and the requirements for items that provide the users’ need for access to the content and the institution’s need to preserve materials of enduring value. Selection works best within a matrix of priorities for digitization.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

Get StartedWork with an archival expert. Learn more about how I might help you by clicking the contact button below.

Contact

June 14, 2021

Archival Data Standards: A Short History

Archival description captures and provides access to information about collections of historical records. The primary descriptive tools of archivists have been finding aids, which supply inventories of collections to help with discovering and using archival materials.

Archival description includes everything from repository guides to catalog cards detailing individual items. Inventories come in various formats but have become more systematic as archivists adopt standards such as MARC and EAD. They also increasingly tend to represent collections. Archives have moved away from the library practice of describing individual items to describing collections, their contents, and their context. When used with a robust archival collections management system (CMS), data standards offer archivists a powerful tool for consistent description.

The Creation of StandardsLibrarians developed MARC as a descriptive tool for books in online public access catalogs (OPACs). Archivists, recognizing the possibilities and lacking an electronic descriptive standard of their own at that time, adopted MARC as a method for describing collections while maintaining finding aids as the primary descriptive tool. Archives commonly implemented MARC to gain representation in library catalogs to help with subject searching and access.

MARC has limitations for archives beyond the issues of granularity, extensibility, and technological obsolescence. One problem with MARC is that while it can manage collection-level description, it does not lend itself to the more detailed parts of archival description. It is possible in MARC to associate series level records with one another and with the collection-level record, but it can be cumbersome in practice.

Some repositories create both EAD-encoded finding aids and MARC records for uncatalogued collections. Though the archival community can question the need for continued MARC cataloging when finding aids are available online, others argue that the benefit of attracting users by including MARC records in local and union catalogs outweighed the added work involved in cataloging.

Data Standards for Finding AidsModern-day inventories usually have a combination of standard data elements and narrative notes. Typically, a finding aid consists of a main entry or title, dates covered in the materials, the cubic or linear feet of the collection, a biographical or historical note providing the user with background on the creating entity, a note describing the scope and contents of the collection, and a statement about arrangement. Other components may include a note on provenance, a list of series or subordinate parts (such as correspondence), descriptions of the series, and a container list detailing the contents of each box and folder.

XML-based StandardsThe use of XML-based standards is an indisputable advantage for archivists. It is simple to convert from one XML DTD or schema to another, making the reuse of all or part of a finding aid easier. XML also creates an environment where it is easy to completely change the look and feel of finding aids by changing a stylesheet.

Despite archivists’ reticence to adopt standard methods for describing the materials in their care, best practices suggest the need for following standard data structures and regularizing the data put into these structures. The interoperability of XML has shown itself to help use the data created to fulfill the requirements of one standard, such as MARC, by reusing it in a new standard like EAD.

Standard AdherenceArchival repositories should capitalize on modern technologies and data standards, enabling the future needs for conversion and reuse of data that archivists have yet to foresee. The use of internationally supported data structure standards also allows archivists to benefit from others’ work by using rules, standards, and conversion tools.

Adherence to standards is necessary for complete machine-processed conversion, such as transferring data from a legacy system to an archival CMS. The consistent application of data standards makes data clean-up unnecessary or minimized. Using controlled vocabularies in establishing creator names and selecting subject headings saves time while creating EADs, for example, as archivists had already checked entries against authority files.

Standardization plays a key role in the ability to adapt to technological change. Traditionally archivists have been skeptical of using standards, in part because the unique nature of archival and manuscript materials requires a unique approach with each collection. This approach changed with the adoption of data structure and content standards. In an online environment, standards improve archival descriptions by new groups of users who may be inexperienced in archival research. The use of standards is also crucial for archival institutions to quickly respond to innovative technologies and user demands.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

Get StartedWork with an archival expert. Learn more about how I might help you by clicking the contact button below.

Contact

June 7, 2021

Description of Electronic Records

One of the most persistent issues, as long as electronic records have existed, is whether traditional archival principles apply.

Some have argued that they do, and archivists should treat electronic records as just another format, like maps, photographs, or audiovisual materials. Others state that the nature of how electronic records are created and managed means that archivists need a new set of rules, practices, and procedures to describe them.

One issue regarding digital records is the mutability of their information. With analog materials, it is easier to tell if changes have been made with and to verify specific versions. It is difficult, if not impossible, to do so with digital materials. Authenticity and reliability are essential to archival appraisal, which carries over into access. Electronic records also have dependencies on hardware and software, as well as issues of the fragility of the media they are recorded on.

There is a pressing need to describe electronic records because of the machine dependency of data, and electronic systems’ complexity. A lack of inherent arrangement underlies description. There is also the need to incorporate life cycle information into description to establish the nature of records, the timing of their creation, and data authenticity.

Description ChallengesElectronic records present several problems regarding traditional description. The first is timing. Most archives develop descriptive language and write finding aids after archivists have accessioned and arranged the records. The stages of the life cycle of records are creation, distribution and use, storage and maintenance, retention and disposition, and archival preservation. Archivists tend to get involved at the very end of the life cycle. Electronic records dictate earlier involvement; delay means crucial information is often irretrievably lost.

Another challenge is the custody of records of enduring value. Archivists tend to describe the records they have in their possession. Electronic records have different models: custodial and noncustodial. Archives may describe records scheduled to come to the archives at some point or records that might remain with the creating agency. A significant decision archivists need to make is what to capture rather than necessarily what to keep.

Traditional description focuses on physicality. Archivists tend to describe physical units, such as boxes, folders, and volumes, leading to the container list that’s typically part of a finding aid, which does not exist with electronic records. Electronic data is stored randomly, so that structure and content are not bound together.

A shift in the emphasis of the description also exists. The description of electronic records tends to emphasize the system level and not the series. However, there is also a shift in terms of provenance and content. There is a greater tendency to focus on provenance: where records come from recordkeeping evidence and often proof of authenticity. There is less of an emphasis on content.

Metadata and DescriptionArchivists must have sufficient data to know that a record exists and identify it, locate it, and determine the conditions under which researchers can use it. Once found, the user needs enough information to access the record, to retrieve the information, and to understand the context of its creation. The user needs information to interpret the content. Sometimes this information can be abstract, assume levels of knowledge, or be based on codes. Description must provide information to verify authenticity and to support the records. Information about a record captured at the system’s creation provides information, but it may not include provenance or sufficient context for an archival perspective.

Professional literature focuses on the role of metadata in description of electronic records. Some argue that all archival description is metadata. Does the existence and availability of metadata preclude the need for anything resembling traditional archival description? It is necessary at the item level to include digital materials online but leads to the conundrum of item level versus aggregate level description, an area that becomes exceedingly complex with electronic records.

Electronic records have unique characteristics, such as the need for supporting documentation to describe their contents and the convenience of editing, copying, erasure, and reformatting. The ease of manipulation, including the challenge of tracing these changes, acts as a double-edged sword. Description of electronic records will change over time, impacting traditional methods of description used for analog materials.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

Get StartedWork with an archival expert. Learn more about how I might help you by clicking the contact button below.

Contact

May 31, 2021

Why Your Organization Needs Records Management

The management of an organization’s current records is records management. Records managers identify and classify an organization’s records, monitor their use and storage, and facilitate access to them. Records policies outline the records management program’s authority, particularly legal mandates governing record creation and maintenance for administrative, legal, and fiscal purposes.

The lifecycle of an organization’s records, including creation, retention, and disposition instructions, is articulated in a records retention schedule. This document assigns responsibility for the creation of records and supports their disposition, or the length of time records are to be retained, whether temporary or permanent.

An organization’s records create its story. Materials created during business document a company’s founding, growth and change, define its corporate structure, and display its accomplishments. Records come in all media: paper, digital files, audiovisual recordings, photographs, prints, and any other format used for recording and accessing information.

Employees use current administrative, legal, and fiscal records for the completion of business activities. Once records have fulfilled the original purpose of their creation, they become inactive and are retained for certain periods per their records retention schedule.

It is unnecessary, risky, and expensive to keep all records permanently. However, some records are inherent to an organization’s fiscal, legal, and intellectual viability and the overall preservation of their heritage and should be permanently kept.

Get StartedWork with a records management expert. Learn more about how I might help you by clicking the contact button below.

Contact

May 24, 2021

Seven Ways to Leverage Organizational History

Your organization’s history allows you to draw critical insights from experience and lay the foundation for distinctive solutions that can set you apart from competitors. Use these seven strategies to harness your history:

Visit your archives or begin one. Understanding institutional history requires access to important documents, images, and artifacts.

Survey the organization’s history. This information will help you understand how history shapes beliefs about the institution today and fill in missing pieces that should be addressed.

Interview of departing, long-tenured employees. Such interviews often provide a history not covered in the written record.

Make the organization’s history accessible. Capture stories about the organization’s work and use them for marketing, publications, and social media.

Document lessons learned on significant projects and initiatives. Recognize that you can discover as much from failure as from success.

Seek historical perspective from the organization’s past before major decisions.

Talk at every opportunity about the organization’s history—iconoclasts, innovations, impact—and what it says about the organization you are or wish to become.

Get StartedWork with an expert with experience in capturing and preserving organizational history. Learn more about how I might help you by clicking the contact button below.

Contact