Margot Note's Blog, page 25

March 8, 2021

The 182-Year-Old Selfie

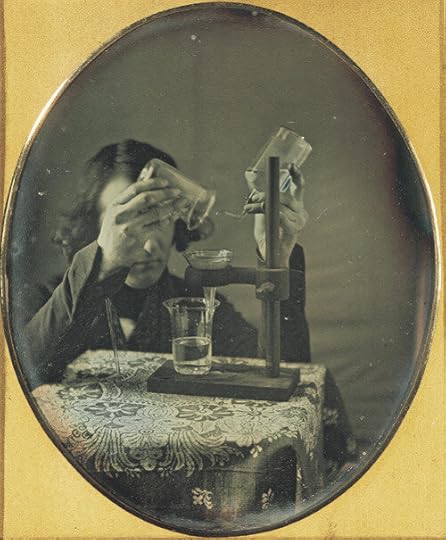

In October 1839, a thirty-year-old Philadelphian named Robert Cornelius stepped into the rear lot of his family’s lamp and chandelier store. The bright sunlight necessary for his experiment saturated the yard. He placed a camera, crafted from a tin box fitted with an opera glass, on a support. Inside was a solid silver plate made light sensitive with iodine. He removed the lens cover and stood as his eyes watered from the sun. After five minutes of stillness, he replaced the cap. Later, he performed a series of chemical processes, including exposure to mercury vapor, to develop the plate and reveal a picture of himself.

His portrait displays a man with crossed arms and tousled hair, eyeing the camera warily. Cornelius’s vibrant depiction belied the long exposure required to make it, and his commanding presence and the off-center composition produced a compelling image. Recognizing his achievement and wanting to capture the moment, he gazed into the lens towards his audience. He imagined himself as one of them – the first ever to see his own photographic visage. One hundred and eighty-two years after its production, the image still captivates us. The daguerreotype now resides at the Library of Congress, with Cornelius’s handwritten note on the back describing it as “the first light Picture ever taken, 1839.” Cornelius’s likeness is the world’s original selfie.

Cornelius, Robert. Self-portrait. 1839. Photograph. Lib. of Cong., Washington D.C. Lib. of Cong. Web. Accessed October 22, 2020. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004....

A selfie, or a self-portrait taken by a cell phone camera and distributed through social media, is a new word for an old phenomenon. Artists have practiced self-portraiture for centuries, and the selfie as an artistic expression dates back to the origins of photography. Additionally, sharing photographic self-portraits is nothing new. The popularity of inexpensive, paper-based cartes de visite in the 1860s, the creation of photo booths in the 1880s, and the invention of Kodak’s Brownie camera in 1900 enabled casual, tradable portraiture and the self-creation of identity. While selfie activity has escalated in recent years, we have only invented a term for the time-honored experience of exploring our ipseity.

After Daguerre announced the invention of his photographic process in August 1839, American photographers soon surpassed the quality of their French counterparts, partly because Philadelphia was one of the leading scientific cities of the world. In the fall of that year, Joseph Saxton approached Cornelius for the silver-coated copper plates required for his daguerreotype experiments, and Cornelius adapted his metallurgy and chemistry knowledge from his father’s lighting business to photography.

With the aid of chemist Paul Beck Goddard, Cornelius used bromide to reduce exposure times for daguerreotypes to less than a minute. As a result, he opened two of the earliest photographic studios in the United States. They operated until 1843, when the increased demand for domestic lighting fixtures monopolized his time. Though Cornelius’s photographic career was brief, thirty of his daguerreotypes have survived. Their quality, along with his portrait, has made him a luminary of early photographic history. He was instrumental in transforming photography from an experimental process into a commercially viable enterprise.

As with Cornelius’s image, initial self-taken digital photographs were flawed; capturing photographs without a viewfinder often created overexposed, out-of-focus, or off-center images. In 2010, a breakthrough occurred when the iPhone 4 featured a front-facing camera. Most devices now include these cameras so that users can take self-portraits while looking at the screen, optimizing framing and focus. The camera’s quality and resolution improves which each upgrade, and the average person can snap photos with no technical knowledge required. Instagram, launched in the same year, generates selfies with artful tones, replacing the harshly lit images of years past. Small, square images invite connections between photographers and viewers, and the app’s visual and textual confines make single subjects more legible than complex ones. Cornelius’s portrait, with his hipster-like appearance and lo-fi aesthetics, could easily pass for a contemporary selfie.

As selfies reached their cultural velocity recently, their detractors associated them with narcissism, exhibitionism, body image issues, and the male gaze gone viral. Rather than dismissing the trend as a derivative of digital culture or a millennial fad, selfies are a means to mark existence and to construct representations of the desired self. Selfie, with its diminutive -ie suffix, is an expression of endearment for the self and the related enterprises of documentation and identity. The appeal of selfies arises from their ease of production and distribution and the control they grant photographers in presenting a curated version of themselves to the world. Their snapshot aesthetic makes these constructed narratives seem more natural and spontaneous than they are; they offer a self-conscious authenticity.

One can only wonder what the message was that Cornelius wished to convey in his selfie. Perhaps he was showing his ingenuity and expertise in demonstrating that portraiture was indeed viable for photography. His second and final self-portrait was taken in 1843, the year he closed his studios. In this daguerreotype, Cornelius performs an experiment on a fabric-draped table used as an armrest for photographic clients. Unlike his first selfie, Cornelius’s face is obscured. The eyes that stared defiantly at us are now, one assumes, focused at his laboratory equipment. His hair, once disheveled, is neatly parted. Rather than skewed and blurred, the crisp image is centered on his work, which is the focus of this unique selfie. Cornelius wished to broadcast to the world that he is a scientific master, demonstrated in his vocation of lighting and avocation of photography.

Cornelius, Robert. Self-portrait. 1843. Photograph. George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

The polished surfaces of Cornelius’s daguerreotypes displayed their viewers like a looking glass. His first, a quarter plate measuring 3-1/8 by 4-1/8 inches, and his final, a 1/6 plate measuring 2-3/4 by x 3-1/4 inches, can rest in the hand, creating a closeness with their audience. Incidentally, the images are similar in size to smartphones, which are gazed into just as much as mirrors. Literally and conceptually, Cornelius’s selfies reflect back on us, demonstrating the universal desire to record ourselves for posterity.

As artifacts of human activity, photographic self-portraits expose the resonant, complex integrity of a person, which others can understand just by looking. To create a self-portrait is to try to understand how one is regarded and how one would wish to be perceived. It is a form of alchemy, once chemical, now technological, that changes our perception of the world and ourselves. Selfies, whether digital or daguerreotype, reveal the human desire to be seen and remembered.

February 22, 2021

Foundations of Visual Literacy: Historic Preservation and Image Management

This paper was written for the Visual Literacies 5 conference at Oxford University in 2011. Despite its age, it still offers insight into the challenges of visually documenting historic preservation work.

Abstract: Visual literacy refers to a number of competencies allowing people to decipher actions, objects, and symbols experienced in the environment and enjoy achievements of visual expression. These abilities are especially imperative in the field of historic preservation, which is heavily reliant upon visual documentation. However, being able to ‘read’ architecture through visual materials remains challenging. In order to understand the highest architectural achievements as well as simple vernacular structures, those who manage images within cultural heritage institutions should be visually literate. Unfortunately, the training archivists, librarians, and other information professionals receive triumphs text over images, and often those charged with image management are impaired by visual analphabetism.

Images conveying built environments or cultural landscapes should not be viewed as decontextualised items, valued only for their aesthetic qualities. Additionally, the ambiguous connotations of images often lead to them being interpreted solely by their subject content. Instead, meaning is revealed by uncovering the context of the images. Information professionals should take into account the historical, aesthetic, and cultural frames of reference, intended functions, relationships and meanings related to conventions at the time and place of construction, and the interests of the image creators. In regards to architectural preservation, the images, as a visual narrative, should impart knowledge about site context, situating projects within their natural or urban landscapes, as well as demonstrating the scope of intervention, including before, during, and after comparisons. This paper explores visual literacy in the historic preservation field through a postmodernist lens. This point of view welcomes a wide range of contextual information as the basis of understanding images and their multiple meanings to advance the universal patrimony embodied in the world’s great monuments.

Key Words: Architecture, conservation, historic preservation, image management, photographs, postmodernism, visual literacy.

Visual literacy is the capacity to analyze, interpret, and use images. Those who are visually literate are interested in the production, circulation, and reception of images, which allows for their placement in a historical context and the evaluation of their integrity. Being visually literate assumes that one form of sense-making does not override others; no single, privileged perspective exists, as images are polysemic. Nor does visual literacy mean that someone can simply see; it is a cultural construction, a learned and cultivated skill. Visual analysis is based on the awareness that a person creates an image, and the image’s subject, the thoughts and feelings of its maker, the techniques used in generating the image, and the context of its response inform the resulting picture.

In an increasingly image-centered world, visual literacy is especially important for information professionals,[i] such as librarians, archivists, and other workers who use information to advance institutional missions. Information professionals have traditionally relied on text as the primary source of information about the past. Education and training in archival, library, and information science has rarely required course work in image analysis, and information professionals often lack skills to evaluate images effectively or have an awareness of their deficiency. Pacey remarks:

There is of course a crucial difference between illiteracy and visual illiteracy. People who cannot read know that they cannot read. We all think we can ‘read’ images—but very probably we cannot.[ii]

Despite logocentrism, scholarly interests across disciplines have expanded, with a growing recognition that photographs transmit information ‘provid[ing] most of the knowledge people have about the look of the past and the reach of the present.’[iii] Photographs ‘now constitute a thoroughly conventional evidentiary resource’ as records of enduring value in their own right.[iv]

This paper explores visual literacy for information professionals when applied to historic preservation image collections. Conservation treats damage caused by natural processes and human actions and thwarts further deterioration using technical and management methods. Historic preservation cannot be understood by text alone; visuals are integral to recording the built environment. Stereophotogrammetry, as well as rectified, X-ray, and infrared photography, provide information to conservators, but this paper focuses on documentary photography, which blends technical ability and artistic skill to record and interpret historic sites.

Although I have previously written about image management in general,[v] this paper arises from my experiences managing a visual collection depicting more than 600 conservation projects in 90 countries over the past 45 years at World Monuments Fund, an international historic preservation organization. To bring the images to a global audience, I have led an initiative to digitize thousands of images and create metadata for ARTstor, a digital image library in the areas of art, architecture, the humanities, and social sciences with a set of tools to view, present, and manage images for research and pedagogical purposes.

While the process has developed my visual literacy, I have found a postmodern approach efficacious. Postmodernism undermines the assumptions of a positivist worldview and discounts its associated concepts of rationality and objectivity. Realizing that there is no ultimate truth but only versions of reality, being visually literate with a postmodern outlook validates the perspectives of conservationists, photographers, and information professionals who manage heritage image collections.

In the nascent years of photography, when long exposures and immobility were required, architecture was a frequent subject. As early as 1850, France’s Historic Monuments Commission (Missions Héliographiques) used photography to survey its architectural treasures.[vi] Since that time, photographs have become understood not as neutral representations of the past, but constructions with historical, aesthetic, and cultural frames of reference with connotations that evolve in response to changing contexts.

As a portal of interdisciplinary exploration, architecture mediates between social values and built forms. Structures are frequently the only tangible evidence of history, offering insights into past cultures and events. Heritage loci, spanning the ancient to the modern, include archaeological sites; burial grounds; cultural landscapes; engineering and industrial works; historic city centers; and, civic, commercial, military, religious, and residential buildings. Cultural significance - the aesthetic, historic, scientific, social, and spiritual values of past, present, and future generations - embodies places, their records, and their uses and associations.[vii]As symbols of the past, locations are instilled with the values of the communities for whom such places have meaning. Different stakeholders ascribe diverse significance to the monuments, producing contrary accounts.

Preservationists assay these site interpretations, determining what the buildings represent related to symbolic qualities, memories, and beliefs. Conservationists are guardians of the past, yet they shape the future, as they research, write, and administer historic significance. The monuments’ ages, uniqueness, associations with people or events, technological qualities, or documentary potential determine historical importance.[viii] Historic value assessment considers if locations demonstrate past customs, philosophies, or systems that are important in understanding historical evolution. Significance is greater where evidence survives in situ or where the settings are largely intact than where they have been changed.

Conservationists determine the most accurate period in a site’s history to preserve, often based on visual information provided by the ‘photographed past.’[ix] Heritage sites transform throughout history, and photographs may only capture a moment in time. Ironically, some ancient buildings may be:

restored to a condition captured by a recording medium - photography - that is much younger than they are, and that can only reveal their condition during the span of its own relatively recent history….The implication is that old images have somehow captured things in their ‘right’ condition, and that they therefore contain some sort of standards by which the present can be evaluated, and perhaps even made to conform.[x]

Photography’s power - and danger - is its capacity to affix images to the historical record and instil agelessness in them. The visually literate understand that photographs seem ‘more real, more right, more true’ than monuments, but they are not.[xi]

To ‘get the picture’, that is, to interpret what is shown in photographs, information professionals represent sites that they have never visited before. Architecture, as a spatial experience of movement and scale, cannot be captured accurately in a two-dimensional photograph. Rather than the architecture itself, most viewers examine images, which act as representations, ‘a mediated relationship using signs or symbols between the maker and the viewer of one object that stands for another.’[xii] Photography allows architectural features to be studied better than in person, where the scale and wealth of details overwhelm the eye. Zooming in permits the observation of minutiae that cannot be seen on site.

Photographic documentation of heritage sites centres on the continuation of design and construction knowledge, the preservation of material and aesthetic heritage, and the promulgation of culture, as well as research, interpretation, and education. Images record existing conditions, aid in evaluation report and drawing preparation, and serve as records for features that may become destroyed or damaged. Photographs also document deterioration that is difficult to indicate in drawings, such as cracks and erosion. Before and after photographs demonstrate the project’s achievements, while photographs taken during intervention capture moments in the conservation process.

Photographers frame their images from almost infinite perspectives, and only a fraction of what constitutes a historic site can be represented in one photograph - or one hundred. Photographs capture cultural, natural, or landscape features, including buildings, site context, spatial relationships, construction techniques and methods, architectural details, materials, circulation patterns, or special functions, among other choices. Shots can be aerial, panoramic, long-, mid-, or short-range; interior or exterior; illuminated or shadowed. Some photographs are standard front, rear, and side elevations, while others reveal neoteric views. Photographers may be professionals who capture dramatic evocations of the built environment or project managers who focus on common conservation issues, such as foundation cracks or façade damage.

Akin to conservators and photographers, information professionals interpret photographic records, understanding that photographs are ‘not a facsimile of total past scenes and events, but only a partial reflection of past reality.’[xiii] Unlike texts, image collections have no order by which they can be understood or titles by which they can be described. Image description is ‘idiosyncratic, knowledge-intensive, and time consuming,’[xiv] because ‘the very characteristics that make [images] valuable also make them difficult to describe.’[xv] Burgin writes that ‘the intelligibility of the photograph is no simple thing; photographs are texts inscribed in terms of what we may call “photographic discourse.”’[xvi] Since photographs represent an ‘insoluble historiographic challenge’, information professionals read visual texts, striving to document their contextual relationships, narratives, and multi-provenance characteristics.[xvii]

Visually literate information professionals appreciate levels of pictoric engagement, which fall under many labels. Barthes distinguishes between denotative and connotative.[xviii] Denotative is the literal meaning of the image. Connotative aspects display visual codes, reflecting signification within the culture. Another way to describe Barthes’ perspective would be ‘ofness’, what an image objectively represents, and ‘aboutness’, what it subjectively represents. Panofsky identifies three levels of meaning: preiconography, iconography, and iconology.[xix] Preiconographical description identifies the objects and events represented in the image, whereas iconographical analysis involves conventional meaning requiring cultural familiarity. Iconology is the intrinsic meaning of the work. Kaplan and Mifflin also describe three similar levels: superficial, concrete, and abstract.[xx] Knowledge of the degrees of meaning provides for better visual literacy, as interpreting image significance requires familiarity with cultural codes in a postmodern milieu.

To understand an image, ‘it is essential to know exactly where it was created, in the framework of what process, to what end, for whom…and how it came into our hands.’[xxi] Information professionals should explore the photographic intent ‘not because it provides the only way of interpreting an image, but because it provides one possible starting point for a more complicated reading of a picture.’[xxii] Appreciating photographic value looks beyond content to various contextual factors that endow significance.

The photograph’s format, process, and size convey meaning. The image’s physicality, ‘prescribed by prevailing technology, determines what can be photographed, how it can be displayed or published, how it can be encountered by others, how it can circulate through public culture.’[xxiii] Most collections contain analog, digitized, and born-digital images, whose formats inform visual literacy. For example, some photographic formats were popular during specific years, which identify their date range.

Of analog formats, 35-mm slides provide the most contextual information because their frames encourage labeling. Since slides were used in lectures, information was recorded on them to aid the speaker’s memory. Conversely, photographic prints frequently lack identifying information because writing on them or applying labels can be damaging.

To fulfill their research potential and be reproducible for publications and exhibits, photographs should have ‘proper focus to render detail, exposure that preserves the full range of tonal contrast, clarity, satisfactory composition and be in good physical condition’ - in short, be aesthetically appealing.[xxiv] Depth of field, point of view, rhythm, color balance, and tonal range must be evaluated. Aesthetics are visual grammar: ‘a well-composed picture makes the author’s point more forcefully than a poorly framed image. The rules of composition, like the rules of grammar, improve the final product.’[xxv] Visually literate information professionals choose images that convey the maximum amount of information about architectural details, yet are composed beautifully.

By constructing sequences throughout conservation and determining adequate site coverage from existing photographs, information professionals hone their visual literacy. Information about images are gleaned from progress reports, project manager memorandums, similar photographs, and other materials.

Interpretation is needed because ‘existing captions are often incomplete, inaccurate, deliberately distorted or irrelevant.’[xxvi] Photographs frequently enter cultural heritage collections without captions, because the photographer, usually the project manager, knew their content and context and saw no need to record them for posterity. ‘Even when photographs have extensive captions…research may be necessary to verify their general accuracy by fact-checking a sample…with the same scrutiny given to any primary resource material.’[xxvii] Due to historic preservation’s global scope, captions may be in another language or written by non-native speakers. Conservation terminology confuses language conversion programs, and human translation may be required.

Scrutiny of the images reveals details to formulate captions. Information professionals may decipher signs, posters, numerals, and other clues. Sometimes, research enhances description, although the findings should be confirmed with multiple citations.

Captions should denote information not readily apparent. For example, captions such as ‘façade’, ‘general interior’, or ‘exterior detail’ should be replaced respectively with ‘northern façade with fire damage’, ‘Great Hall interior, looking south, post-conservation’, or ‘east exterior wall with marble inlay detail’. Captions can identify the image elements and the direction from which the photograph was taken or supply an extensive interpretation of what was photographed and how various elements interrelate.

Description for heritage sites should include site names and locations, names of the photographers and organizations responsible for the documentation, dates, and captions. Other elements may include item titles, image measurements, photographic processes, collection titles, identification numbers, and citations.[xxviii] Data should be captured at the most granular level. For example, locations should include country, region, city, and address; dates should include day, month, and year.

For homogeneous descriptions, I use a metadata schema adapted from VRA Core 4.0, a data standard for the description of works of visual culture as well as the images that document them.[xxix] For architectural terminology, I consult the Art & Architecture Thesaurus, a structured vocabulary created to improve access to information about art, architecture, and material culture.[xxx] Although site features may have been called different names throughout a monument’s history, consistent naming conventions should be used.

Information professionals should also record provenance, the person, agency, or office that created, acquired, used, and retained the images in the course of their work. Knowing who took the photographs, when, and why is essential to understanding the image’s content and the importance of the subject depicted.

Building on a foundation of visual literacy to document heritage sites, information professionals should choose images that address site context, such as the heritage curtilage. Collections should include interiors and exteriors when appropriate and details illustrating character-defining features. For heritage sites undergoing conservation, preservation issues should be recorded. Photographs with people demonstrate site use, scale, and community significance that cannot be conveyed through sterile façades. When different photographers document the same site, the quality varies; information professionals should curate a uniform image collection that complements associated site narratives and drawings. The images should be placed in sequence and keyed to site plans illustrating the locations and directions of the photographic views.

Conservation-based image collections represent heritage sites differently depending on the purpose of the intervention as factors change with each project; some images document narrow physical interventions, while others provide site context. Historic architecture images function both as part of a series and as individual units. They should be compelling as unique images, but they should also tell a narrative about the project and the conservationists’ role in it. Taken as a series, the images impart an understanding of site context, situating the project within its landscape. The sequence also demonstrates the scope of intervention, such as the number of conserved buildings and, to the extent possible, the results of the conservation, including before, during, and after comparisons. For certain projects, including efforts to preserve specific features, identifying the conservation stage is critical. For others, such as efforts to improve site management or sustainable tourism, identifiers are less important.

An escalating demand for architectonic images makes users seek photography more readily than ever before. Through a contextual approach, information professionals provide intellectual and physical access to images. Improving visual literacy for information professionals reveals the marvels of places that speak of their ingenuity, aspiration, and achievement across time, geography, and cultural boundaries. As evidence of humanity’s finest expression, historic structures connect generations, representing the continuity of humankind and the cumulative result of our monumental endeavors.

[i] I use the phrase information professionals, rather than archivists, librarians, or curators, because the management of images affects diverse institutions, such as academic research libraries; historical societies; natural history collections; special collections libraries; commercial archives; and local, municipal, state, and federal records offices. Thus, job titles for those that manage image collections vary widely.

[ii] Phillip Pacey, ‘Information Technology and the Universal Availability of Images’, IFLA Journal 9, no. 3 (1983): 233.

[iii] Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Picador, 1977), 4.

[iv] James W. Cook, ‘Seeing the Visual in U.S. History’, Journal of American History

95, no. 2 (2008): 432.

[v] Margot Note, Managing Image Collections: A Practical Guide (Oxford: Chandos, 2011).

[vi] Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2011), 53.

[vii] Marta de la Torre, ed., Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage (Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2002).

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Derek Bousé, ‘Restoring the Photographed Past’, The Public Historian 24, no. 2 (2002): 10.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid., 11.

[xii] W. J. T. Mitchell, ‘Representation’, in Critical Terms for Literary Study, eds. Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 11.

[xiii] Elisabeth Kaplan and Jeffrey Mifflin, ‘“Mind and Sight”: Visual Literacy and the Archivist’, in American Archival Studies: Readings in Theory and Practice, ed. Randall C. Jimerson (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2000), 85.

[xiv] Claire Dannenbaum, ‘Seeing the Big Picture: Integrating Visual Resources for Art Libraries’, Art Documentation 27, no. 1 (2008): 16.

[xv] Sara Shatford, ‘Describing a Picture: A Thousand Words are Seldom Cost Effective’, Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 4, no. 4 (1984): 14.

[xvi] Victor Burgin, Thinking Photography (London: Macmillan, 1982), 144.

[xvii] Geoffrey Batchen, ‘Camera Lucida: Another Little History of Photography’, in The Meaning of Photography, eds. Robin Kelsey and Blake Stimson (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 76.

[xviii] Roland Barthes, Image-Music-Text (London: Fontana, 1977).

[xix] Erwin Panofsky, Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1939).

[xx] Kaplan and Mifflin, “Mind and Sight.”

[xxi] Michel Duchein, ‘Theoretical Principles and Practical Problems of Respect des Fonds in Archival Science’, Archivaria 16 (1983): 67.

[xxii] Martha A. Sandweiss, ‘Image and Artifact: The Photograph as Evidence in the Digital Age’, Journal of American History 94, no. 1 (2007): 194.

[xxiii] Ibid.,197.

[xxiv] Cilla Ballard and Rodney Teakle, ‘Seizing the Light: The Appraisal of Photographs’, Archives and Manuscripts 19, no. 1 (1991): 47.

[xxv] Frank Boles, Selecting and Appraising Archives and Manuscripts (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2005), 133.

[xxvi] Richard J. Huyda, ‘Photographs and Archives in Canada’, Archivaria 5 (1977): 10.

[xxvii] Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler and Diane Vogt-O’Connor, Photographs: Archival Care and Management (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2008), 77n15.

[xxviii] Ibid., 288.

[xxix] For more information, see www.vraweb.org/projects/vracore4

[xxx] For more information, see www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat

Bibliography

Ballard, Cilla and Rodney Teakle. ‘Seizing the Light: The Appraisal of Photographs’. Archives and Manuscripts 19, no. 1 (1991): 43–9.

Barthes, Roland. Image-Music-Text. London: Fontana, 1977.

Batchen, Geoffrey. ‘Camera Lucida: Another Little History of Photography’. In The Meaning of Photography, edited by Robin Kelsey and Blake Stimson, 76–91. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

Boles, Frank. Selecting and Appraising Archives and Manuscripts. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2005.

Bousé, Derek. ‘Restoring the Photographed Past’. The Public Historian 24, no. 2 (2002): 9-40.

Burgin, Victor. Thinking Photography. London: Macmillan, 1982.

Cook, James W. ‘Seeing the Visual in U.S. History’. Journal of American History 95, no. 2 (2008): 432-41.

Dannenbaum, Claire. ‘Seeing the Big Picture: Integrating Visual Resources for Art Libraries’. Art Documentation 27, no. 1 (2008): 13–7.

de la Torre, Marta, ed. Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2002.

Duchein, Michel. ‘Theoretical Principles and Practical Problems of Respect des Fonds in Archival Science’. Archivaria 16 (1983): 64-82.

Huyda, Richard J. ‘Photographs and Archives in Canada’. Archivaria 5 (1977): 3–16.

Kaplan, Elisabeth and Jeffrey Mifflin. ‘“Mind and Sight”: Visual Literacy and the Archivist’. In American Archival Studies: Readings in Theory and Practice, edited by Randall C. Jimerson, 73-97. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2000.

Marien, Mary Warner. Photography: A Cultural History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2011.

Mitchell, W. J. T. ‘Representation’. In Critical Terms for Literary Study, edited by Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin, 11-22. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Pacey, Phillip. ‘Information Technology and the Universal Availability of Images’. IFLA Journal 9, no. 3 (1983): 230-5.

Panofsky, Erwin. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 1939.

Ritzenthaler, Mary Lynn and Diane Vogt-O’Connor. Photographs: Archival Care and Management. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2008.

Sandweiss, Martha A. ‘Image and Artifact: The Photograph as Evidence in the Digital Age’. Journal of American History 94, no. 1 (2007): 193-202.

Shatford, Sara. ‘Describing a Picture: A Thousand Words are Seldom Cost Effective’. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 4, no. 4 (1984): 13–30.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Picador, 1977.

February 15, 2021

Formulating an Archival Mission Statement

To identify the goals and needs of the archives effectively, archivists need to write mission statements for their repositories. A mission statement outlines the responsibilities of the archivist and the authority of the archives to pursue its goals.

It should address the purpose of the archives, the legal authority of an archives to fulfill its purpose, the primary and secondary needs the archives should meet, and the administrative placement of the archives within in the organization. The archives’ mission statement should mirror its organization’s mission statement so that it remains aligned with critical business objectives. A good mission statement balances the practical with the inspirational as well. It expresses the values and a vision that the organization takes pride in.

Unfortunately, the importance of creating a mission statement is often misunderstood due to many poorly written, vague, or ineffective statements. However, mission statements, when written correctly, can provide a clear direction for internal decision-making.

Use Plain LanguageA mission statement is usually brief, no longer than a few paragraphs. It should be written clearly using the language that constituents use without professional jargon. Avoiding complex language makes the statement more straightforward to users.

Mission statements can also inform researchers and resource allocators about archival work. During difficult economic times, archivists need to succinctly communicate with their mission statements why their repository’s work is important and deserves investment. Mission statements articulate the value of repositories the same way that elevator pitches convey the value of individual archivists.

Aids in Decision-MakingArchivists need to be able to articulate and justify the mission statement amid changing circumstances. The statement sets the boundaries for an archives, positioning it as memorable and unique. Think about the one thing you want your repository to be known for in the world. More importantly, what is the message that already resonates with your donors and users? A mission statement should reflect the goals of the organization, not just the archives. It also helps prevent misunderstandings among archives staff, administrators, and users. The statement serves as an effective tool for offering directions and making decisions.

Most importantly, a mission statement aids in creating an acquisition mandate that outlines the parameters of what an archives will collect. It should state how the institution’s work differs from other institutions. The directive acts as a guiding principle in the archives’ acquisition-related business. Acquisition is a deliberate decision-making practice, because expensive, laborious activities, such as processing, storage, preservation, and access, center on it. A mission statement can also point to collection development needs to be fulfilled through fieldwork. A mission statement provides a foundation upon which other policies can be created, and strategic choices can be made.

Elements to IncludeGreat mission statements have three pivotal elements: a cause, an action, and a result. While most mission statements are longer or more complicated than just these factors, these elements distill your repository’s work to its essence. The statement is not supposed to tell everything about your archives. Instead, it is supposed to get people interested in hearing more.

The statement includes a description of the nature, scope, and functions of the program. You may wish to include information on why the program was initiated and its relationship to the parent organization’s work and goals. In addition, the statement outlines what types of activities the program aims to document, what kinds of records it seeks to collect, and what research groups or interests it exists to serve and support.

Archival AdvocacyA strong mission statement serves as an effective tool for archival advocacy. The process of formulating the mission statement challenges archivists to transcend everyday concerns and reflect on their program’s purposes.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

February 8, 2021

Information Seeking Behavior in Archives

Archival activities begin with developing a collecting policy, then move to acquiring collections and entering them into recordkeeping systems through accessioning, arrangement, description, preservation, and access. Where does the creation of finding aids, and access tools of all sorts, fit into this process?

Is it the end of the processing phase in terms of bringing materials under bibliographic and physical control? Or is it framed with the user in mind, as part of reference services? How do archivists consider how their patrons approach their collections?

Some ConsiderationsBefore examining the information-seeking behavior of archival researchers, it is essential to consider certain factors. The research world changes quickly, and with the impact of technology, the ability to keep current becomes difficult. It is challenging to keep the pace as an information professional, and even more difficult for scholars who are balancing their subject matters and new tools.

The uniqueness of each institution, despite increasing standardization, makes information-seeking challenging. Another factor is the uniqueness of collections—with each being one-of-a-kind. Even within a repository, systems change over time, and retrospective updating is not always performed.

Another factor is the records-centered nature of archives with an emphasis on provenance and original order. Archivists tend to orient their systems around the records and expect researchers to be able to understand and find information within these systems. Working in a face-to-face environment may make things easier but may not with remote research. This traditional approach to archives is not user-oriented and can be intimidating to researchers.

Researcher ExpectationsResearchers tend to base their information-seeking behavior on what they expect to find. They may assume that everything is cataloged or available through a single access point. They may also expect that everything is online and presume item-level access. Researchers do not always distinguish, or know how to distinguish, between primary and secondary sources. Archivists may lack the skills and training to explain how to use archival holdings or to address these assumptions head-on.

Research ApproachesUses for primary sources can be as varied as archival holdings. Scholarly use dominates, but non-scholarly use is also important and often overlooked.

Information seeking preferences vary. Some people enjoy browsing or reading. Other chase footnotes or citations. Others ask their colleagues for leads. Still, others depend on search engines, OPACs, ArchiveGrid, and other discovery systems.

A nonlinear research approach is typical. Some research, for example, is iterative. The more a researcher knows about the subject, the more he or she finds. Developing that knowledge base takes time. Some researchers are looking for a known item, while others are taking a more explorative approach.

Researchers do not naturally connect their information needs to the hierarchical structure of archives. For most researchers, provenance-based finding aids are less than optimal, even though the context that provenance maintains is essential for understanding the records.

Researchers vary on the acceptable quantity of material to access. How much of a collection is a researcher willing to go through? In information retrieval, this is referred to as the balance between precision versus recall. How ready are researchers to wade through unprocessed collections? Or those which have been processed minimally using archivists Mark A. Greene’s and Dennis Meissner’s “More Product, Less Process” approach?

More User-Centered ApproachesArchival systems are set up to expect researchers to be able to connect subjects to proper names. While subject access is more common than it used to be, it is easier to find and provide access points for proper names. Access by place name and date is necessary, too, and finding aids should emphasize these facts as well.

Archival holding systems also tend to be complicated, which is one of the reasons why the staff needs to know the collections as well as the peculiarities of the repository access system, but also need to understand the user’s perspective. Empathizing with and embodying the user experience and their information-seeking behaviors allow archivists to deliver records of enduring value that will support research, pedagogical, and personal projects.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

February 1, 2021

Acquisition and Appraisal for More Representative Archival Collections

Archivists are tasked with making informed selections of primary sources to provide the future with a representation of the human experience. They should build their collections by looking at the bigger picture of history and collecting records that will most accurately present the past to the future.

The process will never be purely objective. However, archival acquisition and appraisal policies can be thoughtful and strategic, using limited time, space, and resources to maximize the collection’s usefulness.

AcquisitionSome archives perceive that their primary duty is to be the custodian of records and abdicate the process of documenting the world to others. If this responsibility is shifted to historians, for example, archival holdings risk reflecting narrow research interests rather than the broad spectrum of human experience. Archivists must be able to work locally between archives as well as nationally to develop guidelines and strategies for archival collecting.

Archivists must employ acquisition policies that are interdisciplinary, cooperative, and definitive. Confronting the problem of acquisition development on an individual basis or continuing to amass documentation on a topic while deferring tough decisions, is no longer a sufficient response. To collect historical evidence, archivists must create strategies to build collections thoughtfully, rather than being passive receivers of files of limited value.

Documentation StrategyArchivists should also build collections cooperatively while minimizing duplication. They can adapt collection management strategies from libraries by building alliances across repositories. Documentation strategy is a multi-institutional, cooperative analysis that combines many archives’ appraisal activities to document main themes and events. The documentation strategy integrates official government and other institutional records with personal manuscripts and visual media, as well as published information and oral histories. Using documentation strategies requires the analysis of the topic’s history and scope, so that adequate records can be gathered. However, the documentation strategy may have limited value for institutional or corporate archives because they cannot share records with other institutions.

Once an acquisition strategy has been formulated, records must be gathered. The systematic process of acquiring manuscripts requires data-gathering, preliminary contact, appraisal, negotiation, transport and receiving, and follow-up. With the documentation strategy in mind, an archivist fills in gaps or strengthens previously acquired collections. Like historians, archivists should strive to develop empathy for the past and a sense of the relationships which once existed.

AppraisalAll archival processes hinge upon appraisal since the decisions made during appraisal will affect future costs and labor at the repository. Administrating modern records has several challenges, such as bulk, redundancy, and impermanence. The growing preservation demands of modern records coupled with the sacrifices made by pursuing less effective alternatives require archivists to ensure optimal use is made of scarce resources through effective planning and evaluation of archival options.

Archivist Gerald Ham cites six collections management elements: interinstitutional cooperation, documented application of appraisal procedures, de-accessioning, pre-archival control, record-volume reduction, and analysis and planning. While by no means all-inclusive, these elements will, if applied judiciously, rationalize and streamline archival acquisition and appraisal. Of course, archivists need to create practices that work for their repositories, rather than following past practices blindly.

During appraisal, archivists function as mediators to find ways to protect the evidence of human action. Archivists leave questions of the meaning of information communicated by records to posterity to investigate. Archivists are, therefore, not processors of information, but keepers and protectors of the integrity of evidence. The purpose of the archivist and their institutions is to preserve the integrity of historical records as reliable and trustworthy evidence of the actions from which they originated.

Archivists also function as mediators between creators and users. They apply appraisal policies formed by committees so that an individual’s viewpoint cannot skew holdings. They act not as interpreters of society because they are responsible to future generations to let them judge society by the documents it produced. Appraisal uses a methodology that reflects current best practices and is appropriate for the repository to preserve historical documentation.

An Active RoleArchivists are not passive receivers and protectors of history; they actively preserve primary sources for research. Although they may not be interpreting these sources, they provide the materials in which histories are written. If all documents arise from memorializing something, they are history in their own right. To decide to preserve them, or destroy them, affects the historical record of the future.

Archivists need to take a more active role in shaping the archival record of the future, creating a more useful and representative documentary heritage. This requires archivists and associated professionals to take leadership roles in selecting and acquiring records, which calls for decision-making and strategy skills. Factors such as the bulk of records, missing data, vulnerable records, and technology have created an information environment in which archivists may have to make hard decisions.

Asking Tough QuestionsAs they conduct their work, archivists should ask themselves if there are opportunities to create alliances with other archives collecting similar material. How can they lead their repositories to be knowledge creators, rather than containers? In asking themselves those questions, they can begin to empower themselves as helping to shape a more representative and accurate history of all people.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

January 25, 2021

Meeting Users’ Expectations of Access to Archives

Throughout the history of the profession, archivists have provided access to the wealth of information they steward. Archivists are responsible for promoting the use of records; this is a fundamental purpose of the keeping of archives.

The decisions archivists make about what evidence is saved and what is discarded shape cultural memory. The nature of the historical record is formed not only by the actions of archivists but also by the public’s ability to access this information.

Technology ChangesAccess has changed considerably in the last few decades, as technology and the Internet provide archivists with the opportunity and the means to reach an international audience, rather than just their local community. In many ways, access is easier in the new information environment. Important or well-used materials can be digitized and made available on the web, preserving and securing the originals. A website, with clear policies and frequently asked questions, can reduce routine reference interactions, so archivists can concentrate on unique research queries.

Societal ChangesSociety has changed so that records are less hierarchical, more decentralized, and abundant, making their relationships and importance harder to distinguish. Access has also become more democratic, as the profession stresses open, equitable access to all users without discrimination or preferential treatment. In the past, only serious researchers and scholars were allowed access. Now, genealogists, students, and the intellectually curious are welcome. Outreach efforts and professional recruitment activities have reached new and underserved communities. Access is no longer a privilege but a right.

Archivists only place restrictions on access for the protection of information privacy or confidentiality, concerns that have become heightened by personal privacy laws, national security, and a more litigious society. Deeds of gift have also changed so that donors and family members no longer have so much control over access.

Technology has also affected societal expectations. Whereas reference used to involve letters or phone calls over time, many researchers expect instant replies; digitized, fully searchable records, and the ability to search across all archival holdings as if they are using Google. To remain relevant, archivists should attempt to satisfy the expectations of “Internet time,” yet still provide the quality service they are known for.

Reference InterviewsWhat archivists offer, that Google cannot, is the reference interaction. Reference interviews, both entering and exiting the repository, are complex, multilayered interactions with intellectual and administrative elements.

Although archives foster user-centered environments, the personal aspect of reference will always be present. Like librarians, archivists mediate between users and source material. However, reference is more vital in archives because archivists have knowledge about the unique nature of materials and of their holding repositories.

People skills are needed to navigate collections and to successfully fulfill complex research questions. Both naïve and experienced researchers have a plethora of needs to be fielded in-person, on the phone, and through email and mail. Unrealistic expectations, such as instant service or unlimited help, need to be treated courteously and professionally.

Interviewing PatronsEntrance interviews orientate researchers on the use of the materials, help them identify relevant holdings, and ensure that research needs are met. Using question negotiation, with its progression of query abstraction, resolution, and refinement, the archivist provides quality reference services within the realities of the archival environment.

Exit interviews are just as important, but they may not occur because researchers may not announce their departures. The exit interview evaluates the success of the visit and the effectiveness of the reference service offered. Additionally, researchers, who may be subject experts, can give feedback about the collection, flag important documents, or raise concerns about misfiling.

Overall, successful archival service—and access—begins and ends with reference interviews, which utilize the full usefulness of the archives while meeting the administrative requirements of the repository. Archivists will continue to build collections; manage their organization, use, and preservation; and, most importantly, provide access.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

January 18, 2021

Archival Values and Use

Archivist T. R. Schellenberg originated the appraisal concepts of evaluating the evidential and information value of records. Although he focused on administrative records, his appraisal concepts can be applied to all records as archivists determine their value and potential use.

Evidential and Informational ValuesEvidential value refers to the evidence the records contain of the organization that produced them and its functions. Information value applies to the information they hold on the “things” which the government body dealt with. Schellenberg proposed that records be assessed for evidential values, mainly if they were records on origins and substantial programs, with different recommendations given for summary narrative accounts, policy, public relations, publicity, and internal management.

Tests for informational values include uniqueness (of the information and the records that contain the information), form (of the information in the records and the records themselves), and importance, applied on groups of records containing information on persons, things, and phenomena.

In providing these guidelines for archival materials, Schellenberg disregards research value or use, which he believed was subjective and easily justified. Instead, he is concerned with making records useful to researchers through systematic analysis of evidential or informational value.

Primary and Secondary UsesValues can also be applied to archivists to differentiate them from creators and users. Whereas creators and users see records as a means to an end, or the primary use, archivists see many applications: the secondary uses. Secondary value, of course, includes evidential or informational value. This secondary value is often unforeseen by the creator of the records, but placed upon them by others later who see multiple ways in which the records can be used to study history. This value is long-lasting and enduring and, therefore, in its essence, archival.

Archival records exist for research, and are not merely saved for their own sake. Some records should be preserved long after their primary purpose, and they should be preserved completely and coherently with a context. They should be organized promptly and administered equitably and impartially, with sensitive information protected.

Does Use Determine Value?Archivist Mark Greene builds upon these theoretical issues to provide the “Minnesota Method” for analyzing the validity of use as an appraisal criterion, which questions the very nature of what archives are. The method has five documentation levels in order of importance. For lower documentation levels, the archivist must decide what will satisfy the most user needs with the least space and least effort. Greene states that use is a measurement of value and the overall success of an archival program. Appraisal considers use, as well as the repository’s mission and resources.

Archivists as UsersArchivists may be among the most critical users of their own archives, particularly as intermediaries for other users. Using the archives so comprehensively gives an archivist a more profound sense of what is both valuable and useful. Implementing use analysis, for example, allows archivists to predict how beneficial they think records are based on past usage patterns. Archivists should also balance access issues, such as physical, legal, and format, to determine if they will impede use.

If a collection is referred to repeatedly, its use determines its value. In my experience as an archivist, I have created finding aids for particular collections and selected records to digitize based on use. Use was often the only way I knew that my colleagues—my primary users—felt that specific records are useful. As a lone arranger, I saw that my own usage patterns (based on queries submitted by others) helped locate the most valuable records, the ones that I returned to repeatedly.

In that sense, the utilization of materials begat better access tools, which resulted in even more use. Use and value can be depicted as the ancient symbol of the ouroboros, a serpent eating its own tail, as records of enduring value continue to demonstrate their value by being used.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

January 11, 2021

Shifting Concepts of Archival Permanence

Archivists need to understand and communicate what they mean by permanence. A historical overview of the concept of permanence starts with oral traditions and ends with current ideas about archives without permanence.

Over time, permanence has acquired varied and shifting meanings for archivists; they distinguish between the permanence of the information and the permanence of the original form of the material. Preservation grew and changed with new technologies, but the only practical solution is to preserve select, rather than comprehensive, records.

The Complicated Concept of PermanentThe idea of permanent records is problematic. To view archival records as permanent disregards the ability of archivists to choose deaccession. The concept of “permanent” in archives has always been a more complicated term than it appears. A reconsideration of the idea of the permanent value of records began to emerge in professional archival discussions in the mid-1980s. A more realistic phrase than permanence is “records of enduring value.” “Acceptable permanence” has also been discussed as archivists further define what can be preserved in contemporary archives.

Digitization as PreservationThe concept of permanence informs digitization. Just as those in earlier times published to ensure permanence of a collection, digitization has become a new tool for preservation. This concept is true to a degree. When a record is digitized, the need to access its original is reduced, limiting wear and tear. Publishing a digitized record online also provides access to many communities previously not served by access to analog records. However, some users believe that if a record is not digital, it does not exist, or the effort to retrieve it is not worth it. Digital preservation is still in its infancy, but it has become clear that there may be even less permanence with digital records than with analog records.

Archivists must understand the nature of the material, such as hardware and software, which make up digital records. They are familiar enough with paper to see how it deteriorates, but they have yet to see how digital records will break down over time and how they can cost-effectively preserve them while retaining their original formatting. Unlike a paper record that may be damaged but is still readable, a digital record that is damaged even slightly is completely unreadable.

Preservation AssessmentCollections should have a preservation assessment at the time of accessioning, with preservation being an ongoing activity. Controlling the environment is the key to preservation, and some preservation activities may be done in-house, while others are left for preservation professionals.

While preservation cannot save materials forever, it can extend their life and their usefulness as historical objects. Preservation can protect items by minimizing their chemical and physical deterioration. In doing so, preservation also reduces information loss.

Making Tough DecisionsArchives without permanence is a contradictory and challenging concept to understand, especially because preservation is so tied to archives. However, this concept offers freedom to archivists because it allows them to make critical decisions regarding the archives.

Using phrases such as “continuing value” or “enduring value” tends to be more accurate than “permanent value” because it recognizes that appraisal decisions made in the past may change. Future archivists may decide that the records no longer hold historical value and can make the decision to reappraise them. This flexibility of judgment allows for archivists to be more responsive to collection needs.

The explosion of records in contemporary times makes selection vital lest archivists find themselves drowning in records. The concept of permanence, and the reality of its temporary nature, is conflicting—but the profession must agree upon standards of “acceptable permanence” to do our work properly and to bring the past to the future.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

January 4, 2021

Archives and Records Management: Then and Now

Archival management originated in the 1930s with the establishment of the National Archives and the Society for American Archivists, as well as the Historical Records Survey (HRS) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

The subsequent evolvement of records management as a specialized enterprise occurred in the 1950s. The expanse of governmental activity and its subsequent records spurred a need to reduce the number of records while retaining the quality of records of enduring value.

Records Scheduling DefinedRecords scheduling identifies and describes records, usually at the series level, and provides information on their retention periods, which differ depending on their nature and origination. Records schedules offer mandatory instructions for disposition, which may include the transfer of permanent records to an archives or the destruction of temporary records. Archives acquire records after their initial purpose—what archivist T. R. Schellenberg called “primary values”—is complete. Records are retained because of their continuing informational, evidential, and intrinsic values.

Both archivists and records managers share the primary tasks of the efficient, systematic arrangement, description, and preservation of documents for future retrieval and reference. The professions of archives and records management meet at records scheduling, because consistent standards for the transfer of records from an organization to an archives create better, representative collections. Archivists have discovered that traditional or analog-based records scheduling and accessioning methods have not proved effective with born-digital records. A current challenge in archives and records management is the development of new skills to expedite the transfer of digital files and to evaluate file format longevity and authenticity.

Enter the Digital AgeHow is the relationship between archives and records management changing in the digital age? The traditional concept of the life cycle of records will change when archivists and records managers work with digital records.

Records management traditionally is explained as a life cycle, with the end being the disposal of records or the transfer of the records to the archives, where it has another life cycle. The continuum model emphasizes that as records end up in archives, record managers should have responsibilities in deciding what is preserved for posterity. Collaboration is best viewed as a continuum, involving working together, iterative adjustment, and information exchange for the mutual benefit of archivists and records managers. The form of collaboration can change depending on circumstances, and it, therefore, implies a set of relationships, rather than one relationship.

The life cycle model is difficult to apply to electronic data because its stages cannot be separated. Creation with digital records is ongoing, then altered many times. Additionally, database management systems separate elements of a record, which can be manipulated. Schedules also become continuous because data is created and re-created.

The Continuum ModelThe split between archivists and records management in the life cycle model may be too defined. Instead, a four-stage continuum may be more accurate. These stages include the creation and receipt of a record, classification within the existing system, scheduling of information, and the maintenance and use of the information.

All record stages are interrelated, forming a significant overlap in which both records managers and archivists are involved, to varying degrees, in the ongoing management of information. The lifecycle stages that records underwent were, in fact, a series of recurring activities performed by archivists and records managers. The underlying unifying or linking factor in the continuum was the service function to the records’ creators and all users.

A Lasting RelationshipIn an environment where organizational hierarchies are being eliminated, and electronic record-keeping systems are becoming dominant, archivists and records managers will continue to work together. An effective record-keeping program, to provide a comprehensive account of an organization’s activities and structure, must be designed and implemented by professional archivists and records managers. The archives program must be highly placed, visible, and accessible—and initiative-taking.

The blog was originally published on Lucidea's blog.

December 28, 2020

How to Be a Better Researcher

Here's a roundup of my best blog posts on Research Methods. I love learning and teaching these tips to make people into better scholars and writers.