Carolyn Schott's Blog, page 3

August 8, 2016

Traveling Into History

Garret and I with our wonderful host in Berlin, Jenia

Guest blogger Laura Schott is a recent college graduate who took her first-ever trip to Europe to visit her ancestral lands of Germany and Norway.

In the midwestern United States, one can expect to find people of two origins: German and Scandinavian. My fiancé and I, both from Fargo, North Dakota, and both recent University of Minnesota graduates, are no exception. Thanks to my dad’s 100 percent heritage, German dominates my own ancestry, but my mom’s side added some dynamism into the mix: I am roughly 75 percent German, 25 percent Norwegian, and a wee bit of Irish and French. My fiancé, Garret, basically has the same heritage, minus the French—here’s to hoping we’re not related!

College graduates head for the countries of their ancestors

As a graduation gift, Garret and I treated ourselves to our first European vacation where we would visit our “homelands” of Norway and Germany. Two of our very close friends accompanied us to Norway, which we visited first, and continued their journey north as Garret and I took off in the southwest direction for Part II of our adventure in Germany.

The four of us first flew from Minneapolis to Boston to Iceland to Oslo, where we stayed with Camilla, a former exchange student that one of our friends hosted during her senior year of high school. Camilla and her family proved to be excellent hosts. After waking up at 3 a.m. in Minneapolis, then taking three successive plane rides, we arrived at their home in Asker (just north of Oslo) to an incredible smorgasbord of breakfast foods.

Different cultures, different foods

Garret and I with our Norwegian host, Camilla

If the beautiful scenery on the train ride to Asker hadn’t already told me we weren’t in the U.S. anymore, the food certainly did. Before Hege, Camilla’s mother, served us coffee, she warned that it would be quite a bit stronger than we were used to. When she visited her daughter in Minnesota a few years ago, she said that she’d been continually surprised (and disappointed) to find that American coffee tasted like water to her. I braced myself before taking the first gulp, and, while it was indeed strong, I proudly finished my mugful.

I didn’t ask for a refill, though.

Throughout the meal, it became apparent that Europeans are much more conscious of the freshness and authenticity of their foods than we are in America. We drank smoothies that were made entirely of fruit (no added sugar), a variety of goat cheese and cold cuts, and bread that was simply amazing.

I’m not sure quite how to describe it, but I think that Jenia, who would later be our host in Berlin, summed up the difference between American and European bread quite accurately: “Sorry, guys, I can’t do American bread,” she said, shaking her head and scrunching up her nose. “It just tastes artificial to me.” We assured her that there was no reason to be sorry—we agreed wholeheartedly and were not looking forward to returning to American bread ourselves!

Garret and I goofed off a bit at Vigeland Park

Vikings and Vigeland

After we slept off our jet lag, we were able to start exploring Norway. We began by spending a day in Oslo, where we visited a Viking museum that reminded me of the Hjemkomst Center in Moorhead, Minnesota. The highlight of the Hjemkomst Center is an exhibit devoted to Robert Asp, a former guidance counselor at Moorhead Junior High School.

Like many Minnesotans, Asp was proud of his Norwegian heritage, but he took his pride to the next level. Asp’s dream was to build a replica of an ancient Viking ship and sail it—all the way to Norway. Asp began plotting his endeavor in the summer of 1971.

Unfortunately, he passed away before his ship could set sail, but his Norwegian spirit, work ethic, and determination lived on in his children and friends who’d helped get the project underway. These friends and family members sailed the ship all the way to Norway in Asp’s honor. The crew of 12 was greeted by their families and honored by a hero’s welcome by the people of Bergen, Norway, on July 19, 1982. As a Midwesterner who was well acquainted with Asp’s story from many school field trips to the Hjemkomst Center, I felt an immediate connection with the Viking Ship museum, and later when we visited Bergen, the Hjemkomst’s landing site.

Camilla took us to some of Oslo’s best-known sites. We took a stroll through Vigeland Park, which is the most enigmatic sculpture park I’ve ever seen. It consists entirely of naked people cast in bronze, granite, and cast iron. These 200-some figures, all crafted by the sculptor Gustav Vigeland (1869–1943) attract a whopping one million visitors every year.

I don’t know what motivated Vigeland’s vision, and nor, to my knowledge, does any historical society in Oslo. There were no informational signs explaining the motive behind Vigeland’s crowning work.

Experiencing places in a new way

Experiencing places in a new wayThis lack of signage was a difference we continued to notice throughout our trip. In America, it seems that if something has even the slightest claim to historical significance, it is accompanied by a sign giving eager viewers the background of what that thing is made of, the geographical region from which said material comes, the person who created/led/died in it, and the names of every person who may have influenced said person. And, of course, the thing at hand has its own snapchat filter and at least a handful of hashtags associated with it. None of this buzz seemed to exist in Norway; a site exists to be experienced in the moment rather than tweeted about.

We also came across this lack of informational signage and brochures during our Norway in a Nutshell tour, which I could not recommend more. It took us through the very different parts of Norwegian countryside—high, low, cold, hot, wet, dry, but ALL beautiful. As someone who loves to learn about the history of place, I was at first disappointed that Norway’s tourism had less to offer than America’s bombardment of information. However, as I stood between mountain peaks and felt the cool, wet air of an ancient waterfall rush past me, I realized that, sometimes, the best way to fully know a place is without the written word—a tough conclusion for me to come to.

But, one can always write about the experience of place later.

July 30, 2016

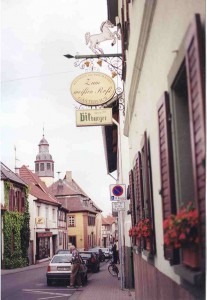

A Village of Quiet Charm

My 2016 visit to Graefenhausen was so much better than my 1999 visit. Instead of standing outside the town hall, I got to sit in the mayor’s chair!

My 1999 visit to Gräfenhausen (origin of my Billigmeier family) epitomizes what not to do when visiting an ancestral town. I showed up there one afternoon, completely unplanned. I stood on the street, looked around, didn’t talk to anyone (didn’t actually see anyone to talk to), took a photo of a building that looked important, stood in the cemetery (no Billigmeier graves), then left. I was probably there about 20 minutes in total.

Visiting last week was a completely different experience, thanks to the warmth and hospitality of the people of Gräfenhausen. The visit helped me fall in love with the quiet charm of this small village, tucked into a wooded valley north of Annweiler.

Herr Unger, a life-long resident, gave me a glimpse into the life and history of Gräfenhausen, his love for his home village shining through with every word. And fortunately, Herr Koelsch, who runs the Annweiler Heimatmuseum, assisted both with translation and by giving me additional background on the history of the area.

I was welcomed into that “important-looking” building (the town hall) that I’d taken a photo of 17 years ago, and seated in the mayor’s seat. (Although technically, Gräfenhausen is part of Annweiler and run by its mayor, the village does have its own community leader.) Herr Unger pulled out a bottle of local wine and we sipped a lovely red as we talked over 500 years of history.

Herr Unger shows where his parents had a garden in the house where he grew up.

It’s a small town, without jaw-dropping sights to see. Instead, I got a very personal glimpse of life there as Herr Unger pointed out the historic-looking homes of his parents, grandparents, and cousins. As he showed me the stables, garden, and smokehouse, his description painted a picture of a family growing up in small-town Germany after WWII.

Going back to my ancestors’ time, I learned how this area had been occupied by the French in the late 1700s, and how hard life had been in the early 1800s despite the end of the French occupation—no doubt the reason that free land in Ukraine was an attractive enough offer to entice my family to travel 1,400 miles east.

I learned that there was no Protestant church in the village at that time, and imagined my ancestors walking a little over a mile each Sunday down the valley to the church in Queichhambach. I learned how methodical the farmers of Gräfenhausen were—wine grapes planted on one side of the valley and all other crops planted on the other side. I discovered that there was a book about the history of Gräfenhausen and I was actually in the village long enough to purchase one (from the one store in town, which is only open 6 a.m. to 11 a.m.).

My hosts in my Ferienwohnung (vacation apartment) in a local winery were warm and welcoming (and happened to be cousins of Herr Unger), curious about my centuries-old connection to their town. They got very engaged in helping me look for possible Billigmeier families (unfortunately, only a few in the online telephone directory and even those with a different spelling) hoping to help me find distant cousins.

My only regret was that the local Gasthof, a restaurant with small beer garden, was closed due to the owner’s illness. I’d had visions of drinking beer with the locals and getting to know a few more people, embracing daily life in the village if only for an evening.

My view toward the soccer field on a warm summer evening.

Gräfenhausen sits at the end of the road, up against the wooded slopes of the surrounding hills. No one ends up in Gräfenhausen accidentally—it’s not on the way to anywhere. It seems a remote location and is—most people living there work in the city of Landau, about 10 miles away. Gräfenhausen residents are often asked why they stay, why they don’t move nearer work and the city. But the small community is a close-knit one, with families whose roots stretch back dozens, sometimes hundreds, of years. Its quiet charm is causing it to grow (lots of new construction happening) despite its remote location because people want to experience that quiet sense of community.

I finished my day sitting on the deck, sipping a chilled local rosé, and listening to the shouts from a soccer match and post-game party at the community center. It made me wish that my connection to this community was a little closer than 200 years.

May 30, 2016

Revolution is Coming

There was joy and dancing.

There was joy.

There was singing and dancing and borscht.

There was violence and death.

Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution was a complex progression of populist protest, community gathering, and deadly serious revolution that cost people their lives. Counting Sheep, the interactive “guerrilla folk opera,” brilliantly portrays Ukrainians’ hopes for a better future as they stand up against their corrupt president, their determination that the protest remain peaceful, and then their perseverance as the Berkut (riot police) begin using deadly force against them.

When people ask me, “Are you Ukrainian?” my answer is usually, “Yes, in spirit.” As a lover of Ukraine, I know more than the average American about the Maidan Revolution. I followed Ukrainian news sources daily during the Revolution, networked with friends (existing and new) on the scene, and participated in local protests. I visited Maidan for myself in the fall of 2014, walking along the wall of memorials for the Heavenly Hundred, accompanied by a friend who told me stories about the people who’d been killed.

The protesters face off against the Berkut. The performance takes place against a back drop of actual video footage of the Maidan Revolution.

But after seeing and participating in Counting Sheep, created by Maidan veterans Mark and Marichka Marczyk and performed by Lemon Bucket Orkestra, I understand Maidan even more. In a small (and much safer) way, I feel like I was there in the middle of the revolution. I better understand the moments of joy and community that existed in the reality of Maidan, when most of the media coverage focused more on Molotov cocktails, overturned buses, and walls of fire from burning tires.

This is not a performance to go to as a detached audience member. I was eating borscht with friends (despite going to the performance alone, I’d gained new Georgian, Ukrainian, and anti-Putin Russian friends by the time it started). I was tapping my foot to the music and laughing with the dancers. Then, wham! A Berkut slaps a baton in front of us and we’re forced to flee as a battle breaks out. I joined in building the barricades, frantically passing tires from one person to the next to create a protective shield between us and the guns of the Berkut.

Audience members take cover behind makeshift shields

The security of having the barricades in place brings a respite—and a wedding celebration. I swallow my last bite of vareniki and toss my plate away as I’m flung into a wild wedding dance … and then the shots ring out and we flee again.

I think the most poignant point was that moment of realization when it became clear that all the protesters’ idealistic hopes, all their joy at working together for a brighter future for Ukraine, had resulted in death by sniper fire; peace and joy had turned to war and mourning.

The performance ends as we walk in funeral procession for those killed at Maidan, and then continue on to eastern Ukraine (actually a room in the basement of the venue), where the remaining “sheep” take up arms to defend their country from Russian invaders. Ukrainians have long been an enduring people—war, famine, Soviet oppression. Maybe their very need to endure has been the reason that they seize joy so fiercely. But Maidan turned long-suffering endurance to a hardened resoluteness to fight for freedom.

The performance ends as we walk in funeral procession for those killed at Maidan, and then continue on to eastern Ukraine (actually a room in the basement of the venue), where the remaining “sheep” take up arms to defend their country from Russian invaders. Ukrainians have long been an enduring people—war, famine, Soviet oppression. Maybe their very need to endure has been the reason that they seize joy so fiercely. But Maidan turned long-suffering endurance to a hardened resoluteness to fight for freedom.

The deaths at Maidan may have been a loss of idealistic hopes, but they became the birth of a determination never again to let dictators and corruption rule their lives.

Counting Sheep helps you experience the joy and the terror of revolution.

Playing in Toronto through June 5, and in Edinburgh, Scotland, in August.

****

If you don’t know the story of Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution, it started in November 2013 when then-President Yanukovych refused to pursue an association agreement with the European Union. It ended in February 2014 with the deaths of about 100 protestors from government sniper fire. Within days, Yanukovych had fled the country and an interim president was installed until elections could be held. In March 2014, Russia illegally annexed Crimea and invaded the Donbas (eastern Ukraine) under the guise of a Ukrainian separatist movement. Crimea and the Donbas continue to be occupied by Russia. The government, under a newly elected president and Parliament, stumbles toward reform.

If you don’t know the story of Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution, it started in November 2013 when then-President Yanukovych refused to pursue an association agreement with the European Union. It ended in February 2014 with the deaths of about 100 protestors from government sniper fire. Within days, Yanukovych had fled the country and an interim president was installed until elections could be held. In March 2014, Russia illegally annexed Crimea and invaded the Donbas (eastern Ukraine) under the guise of a Ukrainian separatist movement. Crimea and the Donbas continue to be occupied by Russia. The government, under a newly elected president and Parliament, stumbles toward reform.

May 1, 2016

Neither Rain Nor Sleet Nor Broken Foot

Visiting the cemetery in my ancestral town of Hoffungstal, Bessarabia, Ukraine

Sometimes it’s the little things in life that are the most dangerous. I survived petting a lion in Zambia and driving through crazed Athens traffic. But I was done in by my hotel door in Bosnia. In my own defense, it was an exceptionally high door threshold that you truly had to step over, sort of like I’ve seen on some ships. I guess I didn’t step quite high enough … and was down for the count.

When a night’s sleep and a couple of Advil didn’t alleviate the pain—well, okay, when I almost collapsed in a heap on the bathroom floor trying to put weight on that foot getting out of the shower—I decided some actual medical attention might be a good idea.

As charmed as I was by Mostar, the historic district (aka a Sea of Cobblestones) didn’t seem like a promising place for modern medicine, so I made a run for the border, back to Croatia, which seemed like my best bet for finding western-style healthcare. It also had the advantage of allowing me to stick with my original itinerary—which meant I’d have a hotel bed to sleep in that night.

I had this unarticulated (and stupid) idea in my mind that if I didn’t take any painkillers, it would mean the injury was not that serious. As a result, struggling up and down stairs with my suitcase to get from hotel to car, multiple hours of driving with my foot throbbing, a 90+ degree day, and a stop at a clinic where they told me that they couldn’t help me, had about done me in.

The last straw was when my rental car wouldn’t start. Piercing pain with every step, hot sun beating down on my head, I felt the tears gathering. I hovered on the brink of a meltdown for what seemed like forever. Only the reminder that at the end of the meltdown I’d still be in the same predicament held back the tears. Rental car company wasn’t answering the phone and I couldn’t walk to get help (since the clinic couldn’t help me medically, I assumed they wouldn’t be able to help me mechanically). Finally, I swallowed my pride and unwillingness to play the helpless female, and asked a group of men chatting in front of the clinic for help.

I’m not sure they spoke English, but my incoherent and frazzled look communicated better than words. But then I couldn’t decide if I should be grateful or irritated that the man who helped me was able to start the car within about a minute.

A moving car with air conditioning revived me enough to face the next ordeal—the hospital in Korcula. The eerie emptiness when I walked through the front door was reminiscent of the Saturday night midnight horror movies I’d watched at childhood slumber parties (after our parents were asleep). It seemed a bad sign that a hospital could be so devoid of life. I started opening doors and peering down hallways, “Hello? Is anyone there?”

I reinforced the gauze of my Croatian cast with duct tape so it would survive the trip through Croatia, to the airport, and on to Vienna.

Persistent wandering led me to the emergency room and then the radiology department, also deserted until I ignored all hospital rules and started peering into one exam room after another—“Hello?”—until a radiologist appeared.

Post-x-ray, I joined what must have been the only human beings in the building—a group of elderly Croatians in a waiting room. I don’t know if they were waiting for medical care or this was just where they met for afternoon coffee, but I ignored their energetic chatter (since I don’t speak Croatian) until I heard a doctor’s voice mention an “Amerikanska.” All eyes turned to me. I guess I stood out a little.

Fortunately, the doctor spoke English. Unfortunately, he confirmed what I’d feared—the foot was broken. I was introduced to the Croatian cast—a bit of plaster on my heel wrapped in lots of gauze. He assured me it was a walking cast and that when the gauze started falling apart, I could come back and get it re-wrapped. I did not find that comforting as I wasn’t sure it would last through the parking lot to get back to my car.

A few hours later, the second tear storm threatened. Instead of a couple of days wandering the streets of old town Korcula, I was stuck at this all-inclusive tourist hotel with mediocre food, unable to walk without my “cast” falling apart. But the worst thing was figuring out whether my gauze-wrapped foot would hold up (or not) to the main part of my trip—tromping through ancestral villages in rural Ukraine, which involves a lot of unpaved, dusty roads, goose-poop-filled yards, and overgrown cemeteries. Should I just cancel that part of the trip and fly home?

A few snips from ordinary desk scissors and voila! The cast is gone!

Then suddenly, I had a flash of inspiration and sprung into action. The plan:

Figure out how to make an international call to Seattle

Seattle friend goes to my house, potentially walking in on my housesitter, and retrieves an orthopedic boot (previous foot injury) from my closet

Friend ships boot to Vienna using overnight delivery, which actually takes two days with the time difference

I call hotel in Vienna and beg them to accept the package even though it will arrive before I’m checked in (which is against their policy)

I worry for two days about whether my plan will work

Boot arrives at hotel in Vienna

Two hours later, I arrive at hotel in Vienna (flying in from Croatia)

I borrow desk scissors and snip off my Croatian cast (remember, it’s mostly gauze) and insert foot into orthopedic boot

Meet my friends for the flight to Odessa as planned. Next stop—rural Ukraine!

Genealogists are like the postal service—neither rain, nor sleet, nor a broken foot will keep us from tromping through cemeteries and ancestral towns.

April 24, 2016

The History of the Schott Name

English translation of Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s book on the family history.

There are several theories for the origin of the name Schott. The one described by Johann Schott von Schottenborn in 1587 is that Schott ancestors originated in the town of Schotten in Hessen, Germany. He describes how his branch of the family left Schotten and settled first near Eisemroth, Hessen. They were smelters and forgers of iron goods for many years until the late 1100s when the country and forests were destroyed due to the wars of Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa.

Without forests to provide the charcoal necessary for iron smelting, the family scattered throughout Hessen. Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s ancestors settled in Braunfels, Hessen. As these families scattered, they would likely have been known as being “zu Schotten” or “from Schotten,” which would have eventually been shortened to using Schott as a last name.

Later critics of the 1587 Schottenchronik are Von Hartmann Pieper and J. Reinhardt Schott, Jr., who published an update to this document sometime after 1960. They warn that Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s work is based on oral tradition, not documented fact or church records that can be objectively proven. They suggest several other possibilities for the origin of the Schott name. One possibility is that any foreigner that was from Scotia (Scotland or Ireland) might have been tagged with the name Schott or Schotten whether or not they originated from the town of Schotten. They believe that it would have been very common for a foreigner to have been singled out even before last names were commonly in use.

Pieper and Schott also suggest the possibility that Schott was a variation on a word for peddler or merchant. Another possibility is that it came from a medieval first name, Schotto.

While it’s true that there are many possibilities for the origin of the name and that the genealogical facts in Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s 1587 document are based primarily on oral tradition rather than documentation, there are a number of pieces of evidence that would seem to (at least partially) support his opinion.

A number of Schott family branches in various locations had coats of arms. While none of these are the same, many of them have similar objects on them—most commonly showing a pod or bundle of pods. (In German, a pod is a Schote—possibly a play on the name Schott.) This could indicate a connection among Schott families in many locations.

Johann Schott von Schottenborn mentions three Schott brothers who scattered from Eisemroth first to Worms, then to the Strasbourg area in the early 1200s. Other documents from the 1500s corroborate that there were indeed three brothers named Schott during this time in Strasbourg who had come from Worms. One document would have been in an archive that it is unlikely Johann Schott von Schottenborn would ever have seen; another was published after his death. So although his information may not have been 100 percent accurate, there is evidence that supports at least some of it.

My branch of Schotts ended up in Kulm, North Dakota.

Literacy and written documentation were rare in those days compared to today’s society. Much information was passed on through oral tradition, so it doesn’t seem unreasonable to believe that Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s information has at least some truth to it. As Sir Samuel Haslam Scott says “The account of the successive generations … and of the derivation of the surname … depends on oral tradition. But the tradition is at any rate venerable, and in the opinion of such an authority as Mr. Oswald Barron it presents an example of the genuine family tradition with no inherent improbability, in contrast to the ordinary family myth so distrusted by the genealogist.” [Note: Oswald Barron was a noted British authority on heraldry and genealogy.]

Therefore, it seems plausible to believe that a great deal of the 1587 document could be accurate, including its speculations on the origin of the Schott name, although it can’t be proven with complete assurance.

As Sir Samuel Scott concludes: “The name [Schott] is an old one, but it is not a distinguished lineage, nor is it an eventful record. The lives of the estimable make a less exciting story than the dramatic villainies of the unscrupulous.”

Sources:

Arnold, Friedrich E.G. Stammreihen der nassauisch-hessischen Familie Schott aus Eisemroth bei Dillenburg. Self-published, Hamburg-Blankensee, 1957. Available on microfilm 1181524, item 3, from the Family History Library in Salt Lake City. [This is one of the updates to Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s Die Schottenchronik. An incredible source of information on the village of Schotten and Schott family history from the year 1015 through the 1900s for many branches. This is primarily genealogical data with some written history, but shows all the Schott families that occupied Hessen through this time period. As you might guess from the title, it’s all in German.]

Pieper, Von Hartmann and J. Reinhardt Schott, Jr. Die Schottenchronik. Published sometime after 1960. [This is another version of Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s family history. This one is based on the original manuscript, rather than the F.E.G. Arnold version, which was based on a copy. These authors make a lot of the fact that the early Schott family history is based on oral tradition, and can’t be verified in any way and therefore, should not be relied on. They also claim that their version is much more accurate than the F.E.G. Arnold version because it’s based on the original, not a copy. While I certainly found some discrepancies, I would say these are minor. These authors, however, have added to the original with information from other sources, which makes this version more complete overall.]

Scott, Sir Samuel Haslam of Yews. “An Old German Family History.” The Ancestor (London, April 1903).

Scott, Sir Samuel Haslam of Yews. A True Relation by Johann Schott von Schottenborn 1587. Translation by Sir Samuel Haslam Scott of Yews. Oxford University Press, 1929. [An incredible find—I had seen references to this English translation of the Johann Schott von Schottenborn document by an English branch of the family, but had no idea how to get my hands on a copy. I finally found it in an Irish bookstore through a rare book site on the Internet—and they were more than happy to sell this to me. This book/manuscript is the basis for all of the really early Schott family history and the theories about how the Schott name came into existence.]

March 9, 2016

Hope/Nadiya/надія

Seattle says #FreeSavchenko

I am an idiot. In the space of about 18 hours, I participated in two demonstrations (one in pouring rain), tweeted about both, participated in a Twitter storm (an online protest), wrote emails to my senators and congressional representative, and prayed for Nadiya Savchenko.

Nadiya is a woman to admire—a pilot who was the first woman to graduate from Ukraine’s military flight school and served with peacekeeping forces in Iraq, an elected member of Ukraine’s parliament, and a delegate to the European Parliamentary Assembly Council of Europe.

She is also a prisoner, held in Russia on trumped-up charges for nearly two years. In protest of their trial proceedings (which bear more resemblance to a Three Stooges movie than to justice), and the continually delayed but expected sentence of 23 years in a Russian prison, she recently started a dry hunger strike. No food, no water. It’s estimated that a person can live a week, or maybe eight to 10 days at the outside, without water.

Nadiya’s been without water for six days. So her release is a little urgent.

The urgency drives my actions. But I’m an idiot because, for all my frenzy of activity, I have no expectation that anything I do will make a difference. She has become a symbol of feisty Ukrainian resistance to Russian interference with and invasion of Ukraine. As such, Putin can never back down and let her go.

Possibly (though not likely), she’ll listen to the pleas from many to stop her hunger strike, and when the court reconvenes on March 21, she’ll be sentenced to 23 years in a Russian prison.

More likely, she’ll continue her strike and she will be dead on March 21. Whatever sentence Russia gives at that point will make no difference. (I can even see a horrific scenario in which the court makes the perverse announcement that they never intended to sentence her to prison at all. I wouldn’t believe them, but I can see them delighting in torturing her family.)

Demonstrating for Nadiya in the Seattle rain

All of my protesting and tweeting and letter writing is based on the assumption that Russia cares what the world thinks of them, and therefore, will release her. But I know that Russia doesn’t care. And since the international community hasn’t stopped them when they invaded Ukraine or propped up the despotic Assad regime in Syria, I doubt that international leaders’ calls for her release have any impact on their plans.

So why do I bother?

I met someone at the demonstration I went to today. He’s been in the U.S. for 20 years and says he feels more American than Ukrainian. And even growing up in Ukraine, his childhood and youth were during Soviet times, so he said he felt more Russian than Ukrainian. But, he said, this isn’t about politics. It’s about standing up for moral principles. I agree.

But also, in some unexplainable, illogical way—I have hope. I see no possible way for this to work out well for Nadiya. But I remember in the final days of Maidan, I felt the same. People were dying. Agreements were being struck that left the corrupt Yanukovych in place. I saw no good path forward … and then one appeared. Yanukovych fled, leaving the opening for a new government to be established. Even with all the current problems, Ukraine is better off than it was before Maidan.

I see no good path forward for Nadiya to be able to return to Ukraine a free woman. But Nadiya’s very name (in Ukrainian) is Hope.

Nothing I am doing will logically make a difference. But I choose to hope. And demonstrate. And tweet. And write emails. And pray. I may be an idiot, but I choose hope.

February 17, 2016

Pilgrimage to Maidan

“I’m dying.” –Tweet from a 21-year-old volunteer medic, Olesya Zhukovskaya, February 20, 2014.

This update was the first thing I saw in my Facebook feed that morning two years ago.

Maidan in Kyiv

I’d woken up determined to cut back on my obsessive reading of news about Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution. Since the day in November 2013 when brutal beatings by police had sent peaceful protesters fleeing to St. Michael’s church for refuge, the first thing I’d done each morning and each evening after work was scour Facebook and Twitter for news from Ukraine.

I cheered on the bravery of the Maidaners in their persistent demonstration against the corrupt Yanukovych government, wanting something better for their country and their lives. I was horrified at news of mysterious disappearances, torture, and suppression laws that violated individual freedoms. The news that people were losing their lives to brutal riot police and snipers made me weep. I did what little was in my power (mostly writing and tweeting to U.S. and EU officials) to support their courage.

I’d traveled to Ukraine multiple times. I had friends there. I’d walked the streets where the revolution was happening. My heart was in Ukraine. But sitting at my breakfast table in Seattle that morning, I’d told myself that reading the news obsessively wasn’t helping anyone in Ukraine. I needed to focus on my own life rather than events thousands of miles away that I couldn’t change.

“I’m dying.” The voice of a young woman, shot in the throat. So much more poignant and immediate than a detached news report published hours and days after the event.

I gave up any idea of detachment. Hour by hour, I watched the tragedy unfold as the government threatened the protesters, international officials tried to negotiate peace, and Yanukovych brought in snipers, killing about hundred protesters. I couldn’t do anything. I was thousands of miles away. But somehow, knowing what was happening, praying, I felt like I had a very minor walk-on role in these faraway events.

My heart was in Ukraine, at Maidan, through the winter of 2013-2014. So when my body was finally able to go to Ukraine in October 2014 (as an international observer for their elections), naturally, the first place I wanted to visit was Maidan.

Memorial to the Heaven’s Hundred

Visiting Maidan

I don’t know what I expected, but Kyiv was deceptively normal. People walking their dogs and children playing in Mariinsky Park. People in coffee shops, talking on their phones, walking through the streets to work.

And yet …

Police wearing bulletproof vests were numerous on the streets around Maidan, as were men in military outfits. Large photo displays documented the presence of Russian troops in the east. Body-shaped outlines on Hrushshevsky Street showed where the first people killed in this revolution had died.

The memorials to those killed at Maidan, the “Heaven’s Hundred” as they’re called, are covered in icons and flowers. These are fresh scars in people’s memories—sons, brothers, husbands who will never come home again because they believed in a Ukraine of freedom and justice.

My friend Natasha participated in Maidan. She brought life to some of the names and photos as she pointed to each—this man was a beloved teacher who came to Maidan each day after school; this young man had decided to give up and go home, but then turned around and came back to Maidan … only to be shot hours later. Real people with real families mourning them.

The memorial that brought me to tears was the one for Antonyna Dvoryanets. As a volunteer for Voices of Ukraine, I’d edited the translation of her story. She went to Maidan every day, bringing food to help feed the protesters and was killed there on February 18. Somehow, editing the story made it more personal for me than simply reading it. I found myself dripping tears as I marked corrections in red pen.

The memorial that brought me to tears was the one for Antonyna Dvoryanets. As a volunteer for Voices of Ukraine, I’d edited the translation of her story. She went to Maidan every day, bringing food to help feed the protesters and was killed there on February 18. Somehow, editing the story made it more personal for me than simply reading it. I found myself dripping tears as I marked corrections in red pen.

Standing on Maidan that cold fall day in Kyiv, I gazed at Antonyna’s memorial and heard her daughter’s words in my head: “I want my Mom. Anywhere, just take me to my Mom.”

Antonyna died at Maidan. Young Olesya lived. Real people. Real heroes.

Slava Ukraini. Heroyam slava.

Glory to Ukraine. Glory to the heroes.

February 9, 2016

Osthofen, Germany: My Ancestral Town

The town of Osthofen, Germany, was the home of the Schott family from at least1717 to 1809. It is over 1,200 years old, and was first mentioned in 784 in the Lorscher Codex (a manuscript from the Lorsch Monastery). In 784 it was referred to as Ostova. Later names included Osthoven (1262), Osthouen (1268), Ostown (1283), Osthoen (1330), Osthoben (1346), Osthoffen (1438), and finally Osthofen.

The town of Osthofen, Germany, was the home of the Schott family from at least1717 to 1809. It is over 1,200 years old, and was first mentioned in 784 in the Lorscher Codex (a manuscript from the Lorsch Monastery). In 784 it was referred to as Ostova. Later names included Osthoven (1262), Osthouen (1268), Ostown (1283), Osthoen (1330), Osthoben (1346), Osthoffen (1438), and finally Osthofen.

The town lies near the left bank of the Rhine River (a couple of miles west of the river), just north of the city of Worms and south of Mainz.

Throughout the Middle Ages, many religious orders owned estates in the town (the Bishops of Metz, Mainz, and Worms; the monasteries at Hornbach, Mühlheim, and Lorsch; and the Hospitaller Knights). The village sheriff (or administrator), who also had responsibility for the neighboring town of Westhofen, was a vassal of the emperor and or various nobility.

By 1195, a well-fortified town had been built on the hill (on the south edge of the current town), which is currently the site of the Bergkirche (literally, the “mountain church”) and the cemetery. This town was completely destroyed in 1241 by the troops of Bishop Landolf of Worms (possibly because the citizens of Osthofen were preying upon their less-well-protected neighbors by robbing them then retreating to the protection of the town walls).

The Bergkirche in Osthofen

Strife in the area continued until 1342 when Count Friedrich II of Leiningen became the patron of the village. From 1468 to 1798, Osthofen belonged the Electoral Palatine (often called the Palatinate or Pfalz region), ruled by the Elector Count Palatine. (Being an Elector meant he was one of the group entitled to elect the Holy Roman Emperor.)

As a result of the Peasants’ Rebellion in 1525 (which had its roots in the philosophies of the Reformation), the town of Osthofen was attacked by the Holy Roman Emperor’s forces. In 1548, Count Friedrich II recognized the Lutheran religion as an official religion in the Palatinate in addition to Catholicism. In 1560, the entire Palatinate area, under Elector Count Friedrich III, adopted the Calvinist Reform faith. The counts Palatine became chief drivers of the Protestant cause, with Count Friedrich IV becoming the head of a Protestant military alliance, known as the Protestant Union, in 1608.

The 1600s were a particularly turbulent time in the Palatinate (including the area around Osthofen), due to a series of wars (a result of religious differences and battles over succession of various nobility) and the plague. The area of Osthofen was right in the path of numerous armies, causing the inhabitants to flee the village several times during the 17th century. With the Elector Count Palatine being one of the key powers supporting Protestantism, this area became one of the primary battlegrounds.

The Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648) resulted in widespread battles throughout Europe, but primarily in Germany and the lands of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1621, the entire village of Osthofen was destroyed by General Spinola of Spain and his army. In 1637, the Osthofen villagers fled to escape the imperial army. Some hid in the ruins of the village until 1642, but from 1642 to 1648, the village of Osthofen was completely deserted. (Another source says the village was deserted as early as 1632.) Although the villagers began to return after 1648 when peace was declared, many had died—either as casualties of the war or from the plague which was sweeping through Germany. Less than 15 percent of the original villagers returned.

Typical Fachwerk in Osthofen

More war swept through the area between 1674 and 1676, as the French armies tried to annex this area to France. Then in 1685, the Count of the Palatinate died without an heir. King Louis XIV of France was determined to put his sister-in-law on the throne, who had a claim through marriage. (This became a power struggle between the Hapsburg and Bourbon dynasties.) The War for the Pfälzisch Succession (also called the War of the League of Augsburg) raged from 1689 to 1698, and once again, the town of Osthofen was deserted since it lay in the path of the warring armies. (This war also caused a large number of Germans from the Palatinate area to immigrate to America, primarily Pennsylvania, at this time.)

When the war was over, a few families returned. A 1698 census shows only 39 families (about 200 people) living in Osthofen—primarily of the Reform faith. (Six families were Catholic and four were Lutheran.) The town began to rebuild itself and grow once again. By 1710, the town was prosperous enough to pave its main street through town. With peace in the area, there were opportunities for new people to move in and help the area grow again. By 1722, the population had risen to 787 people.

It was sometime during this time period that Michael Schott arrived. The first documentation is of his marriage in 1717, at the age of 24, to Gertraudt Bitter. (Although, presumably he would have lived there at least a couple of years to be considered an acceptable husband to Gertraudt’s parents.) Michael’s father (also named Michael) died when he was just 12, leaving him living with his stepmother. This may have been one of the reasons he left his home village of Ober Gleen, Hessen, to migrate to Osthofen.

After the Thirty Years War and as the town grew, Osthofen contained a mixture of religions. Although the townspeople was primarily of the Calvinist Reform faith, there were also Lutherans (including the Schott family), Catholics, some Mennonites from Switzerland, and some Jews.

The Catholics used a chapel in the town for their services. The Lutheran and Reform congregations probably shared the Bergkirche (which had been built before the Thirty Years War on the hill where the fortified town had once been) until 1705, the year of the Pfälzisch Church division. The larger Reform congregation continued to use the Bergkirche, while the Lutheran congregation met on the site of the destroyed city hall (presumably making some repairs first).

In 1727, the town decided that they wanted to further repair and refurbish the city hall and use it once again, however the Lutherans refused to give up their church. By 1738, the situation had been decided in the Lutherans’ favor, and the city built a new city hall on another site.

In the meantime, the Lutherans were building a new church building. Opponents of the Lutherans harassed them during the construction, pulling down the church bell, striking the walls, and stealing a column that was originally meant to be used in the church for use in the new city hall. The Lutherans persevered however, and finally had a “proper” church in 1739. (In 1822, the Reform and Lutheran churches merged, becoming the German Evangelisch Church. Although the Lutheran church building still stands, it is no longer used as a church because the Evangelisch congregation uses the Bergkirche.)

The Lutheran congregation shared a pastor with Westhofen. Until 1720, the pastor’s home and main church was in Westhofen. In 1720, he moved his primary home to Osthofen.

View of the village

Each of the churches also had their own schools. The Lutheran school existed from 1702 to 1822, and is probably where the Schott children attended school. It was about half the size of the Reform school (87 students in 1813 versus 214 students in the Reform school), and paid correspondingly poorer wages. The Lutheran school teacher earned 13 “Malter” of grain per year. A “Malt” was a unit of measure that could vary from 11 to 240 liters, so it’s difficult to know how well-paid the schoolteacher was.

The teacher from 1739 to 1772 was Konrad Helfenbeiner. His son, Johann Peter Helfenbeiner, succeeded him as teacher from 1772 to 1794. His daughter, Johanna, married into the Schott family.

By the 1780s, Osthofen had successfully risen from the ashes of the traumatic 17th century. The population in 1787 was 1727 inhabitants—an eight-fold increase from 1698. The town had three churches and three schools.

The area around Osthofen was a rich, agricultural area. In particular, growing grapes for wine was a very important crop. However, crafts and industries also played an equally important role in Osthofen’s development and prosperity.

A list from 1786 shows the following craftsmen: 2 barbers, 3 bakers, 3 beer brewers, 2 lathe turners, 3 shopkeepers, 11 coopers (some of whom also made beer and distilled brandy), 7 linen weavers (which would have included a couple of the Schott families), 4 stonemasons, 4 butchers, 9 millers (Osthofen had several mills), 2 sackmakers, 1 saddler, 4 innkeepers (although the translation of Schildwirth as innkeeper is uncertain), 1 locksmith/mechanic, 3 blacksmiths, 8 tailors, 3 cabinet makers, 16 shoemakers, 2 wagon builders, 2 master carpenters, and one village brick/tile factory.

The guilds were very important in 18th century Germany as a craftsman had to belong to a guild to sell their products. Presumably, the Schotts must have belonged to the linen weavers’ guild.

The guilds were very important in 18th century Germany as a craftsman had to belong to a guild to sell their products. Presumably, the Schotts must have belonged to the linen weavers’ guild.

The main guild hall for Osthofen’s craftsmen was initially in Alzey, then later in Westhofen. An example of their power: in Osthofen in 1744, the shopkeepers’ guild managed to make it illegal for itinerant peddlers and door-to-door salesmen to sell goods. In 1786, the “protected Jew” Hertz was forbidden to sell spices, oil, and vinegar because this was reserved for the guilds. (I’m not sure what the “protected” designation meant.) However, with the occupation of the area by France in 1798, the guild system came to an end.

Osthofen also had a number of village officials. Some of the positions that existed (certainly during the 1600s and many probably carried over to the 1700s) were: Bürgermeister or mayor, night watchman, police guard (who had the responsibility to ensure that no one drank wine during “forbidden times”), tax collector, town gate watchmen, a bell ringer (who had the responsibility of ringing the bell every morning at 6:00 a.m.), a building contractor for village buildings, firefighters, “vintner hunters” (who probably had the responsibility to watch over the vineyards in the fall), and wine coopers.

In 1792, the French army invaded the German areas on the left bank of the Rhine. They arrived in Osthofen in October. In the spring of 1793, the Prussian army came through and 1,220 Prussian troops were quartered there, which almost doubled the size of the town. After 1793, the French once again occupied the area. They quartered 1,670 men in the town in 1794, and plundered and confiscated supplies, including bread, wine, brandy, hay, straw, and chickens. In 1795, Osthofen citizens were recruited to man entrenchments near Mainz. Finally in 1797, the Prussian army made its final retreat, destroying the vineyards of Osthofen as they passed. In 1798, Osthofen, along with the rest of the German villages on the left bank of the Rhine, became part of the French jurisdiction called the Departement Mont-Tonnerre in Canton Bechtheim.

A Weingut in Osthofen

The French continued to quarter troops in the area. In 1806, Osthofen was asked to provide supplies for Prussian prisoners being held in the town of Alzey. The mayor replied that it was unreasonable to expect Osthofen to not only to provide daily support for the troops in the area, but also to provide more supplies when the town was already empty and some of the impoverished men and families were “already in misery.” He also makes the point that because Osthofen was near a crossing point on the Rhine, that more goods were requisitioned from their town than from other towns in the district.

The French occupation of Osthofen continued until 1816, but by that time, the Schott family had immigrated to Russia.

Today Osthofen is a small, pleasant town of about 8,000 residents that is an easy commute by train to Worms. Osthofen is known for its excellent wines, and each September celebrates the Wonnegau Region Winegrowers’ Fest.

Sources:

1200 Jahre Osthofen, Auf den Spuren der Vergangenheit. Druckhaus Seibert GmbH. Osthofen, 1984. [A valuable resource on Osthofen information with lots of historical details, photos, and maps – but difficult since it’s all in German!]

Blanning, T.C.W. The French Revolution in Germany. Oxford University Press. New York. 1983. [Scholarly to the point of being difficult to read – but has great information on a bit of history that seems to be invisible elsewhere – and that obviously had a direct impact on why the Schott family decided to leave Germany and go to Russia.]

Brilmayer, Karl Johann. Rheinhessen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Verlag Weidlich, Würzburg, 1985. Reprinted from 1905 edition, Verlag von Emil Roth. [Some interesting stuff on Osthofen, but that old Gothic print makes it a last choice as an information resource.]

Kitchen, Martin. Cambridge Illustrated History – Germany. Cambridge University Press, 1996. [I don’t think the Germans’ migration to Russia is mentioned even once – but aside from that glaring hole, this is a good overview of the history of Germany.]

February 7, 2016

First-Timer Impressions of RootsTech

After 20 years of doing genealogy, I thought it was about time I got myself to RootsTech, an enormous annual genealogy convention in Salt Lake City. A few first-timer impressions:

The positive

Tech stuff – the wifi connection was awesome and there were charging stations everywhere for my hungry electronic devices. The charging station counter was just the right size for my personal-size pizza (that was satisfying my hunger) to sit nicely on the counter next to my plugged-in phone (satisfying its hunger). This is not trivial. I’ve been to so many meetings where connectivity is a huge and annoying issue.

Tech stuff – the wifi connection was awesome and there were charging stations everywhere for my hungry electronic devices. The charging station counter was just the right size for my personal-size pizza (that was satisfying my hunger) to sit nicely on the counter next to my plugged-in phone (satisfying its hunger). This is not trivial. I’ve been to so many meetings where connectivity is a huge and annoying issue.

Genealogy stuff – the Expo Hall has vendors exhibiting everything you could possibly want for genealogy. Software, fancy charts, cool scanners, vendors with new records available online, books, new apps, methods for creating family books, advice on preserving antique textiles and family heirlooms, people standing by to give you advice on navigating their websites, how-to presentations. It’s a veritable selling frenzy.

I confess that some exhibits left me thinking “Who could possibly need this?” And when I asked one of the fancy chart-making software firms why I needed their “working charts” when I had Family Tree Maker and nearby Fedex/Office Depot stores that could print on large-size paper, they admitted, “You don’t.”

Workshops – they have a wide variety of workshops on a wide variety of topics from research topics to family story gathering. Even workshops I wasn’t that excited about attending provided a few new tidbits of useful info.

Logistics – this conference is a well-oiled machine. It’s easy to find the rooms and events of the day, their app notifies you of room changes, registering is quick and easy, a herd of volunteers in green shirts are there to help. They are absolute Disney-esque in their efficiency with a smile.

Focus on youth – Saturday was “Family Discovery Day” to introduce kids/youth to family history. Fun and games like Genealogy Twister (“Anyone who had an ancestor fight in a war, right hand red!”) If you drag your family along to your genealogy conventions or live in Salt Lake City, this is a fun way to get kids interested.

The less positive

The convention definitely caters to the mainstream – beginning to intermediate genealogists, especially the vast majority of people who have roots in the U.S., U.K., Ireland, and to a lesser extent, Germany.

Although I didn’t expect to find information on my own “dead people demographic” (Germans who came from Ukraine and other parts of Central/Eastern Europe), I did expect there to be a good variety of genealogy workshops on advanced topics. While these did exist, there weren’t many and they were generally in the smaller rooms. I got shut out of three of the four advanced topic workshops I tried to attend. And I didn’t find the technology content all that advanced. Maybe that was in the workshops that filled up and I couldn’t go to.

Because this is such a prominent conference in the industry, I thought I would be learning something really solid, like (to use a food metaphor) a juicy steak and baked potato dinner. Instead, I felt that I only got cheese and crackers. A tasty snack, but not the substantial meal I was expecting. It left me wanting more.

If I go again, I’ll be a lot more aggressive and cutthroat in getting into the classes I want.

The biggest highlight? Meeting a distant cousin who I’d only corresponded with by email. When you’re searching for dead people, it’s always fun to actually find a live one.

January 26, 2016

Schotten, Germany: Land of My People

Traditional architecture in Schotten

The town of Schotten is said to be the place of origin of both the Schott family and the Schott name sometime between the 11th and 13th centuries. The official history for the town of Schotten, Germany, is that an early document mentions a church “ad scotis” or “of the Scots” that is one of eight churches that Abbot Beatus bequeaths to the monastery Honau by Strasbourg. It is thought that this is likely to have been the first church in Schotten, which was built by Irish-Scottish monks.

This church probably grew, and by 1050, the first Roman Catholic church was built. Then, in the 1300s, the original Liebfrauenkirche (which was still in existence in 2001) was built in the town of Schotten.

A slightly more romantic version of this story is described in Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s 1587 family chronicle. [Quotes are from Sir Samuel Haslam Scott’s English translation.] This describes the origin of the village in 1015, when two Scottish princesses (Dickmunda and Adelmunda/Rosamunda) “founded at Wetter in the land of Hessen a nunnery.”

Liebfrauenkirche in Schotten

While the idea of Scottish (which may have actually been Irish) princesses wandering around 11th century Germany may seem improbable, there is evidence to support this. During a renovation of the church in Schotten in the 1700s, a parchment document dating from the 1300s was discovered which stated (in Latin): “anno 1015 after the birth of Christ in the reign of the King nicknamed the lame (Henry II, Emperor 1002 – 1024) two sisters from Scotia, one called Rosamunda, the other Dicmudis, began to build this town and our first church at Schotten.” There were also two wooden busts of these two sisters found in the church.

There were several “Schottenkirchen” (churches started by Scottish-Irish monks) in the Hessen area, all dependent on the mother church at Strasbourg. Florens, an Irish hermit, had been elected bishop of Strasbourg in 679. It’s likely that these two sisters were Irish, rather than Scottish, since Irish monks had been instrumental in spreading Christianity to the European continent, beginning with the work of St. Columban in 585.

(It’s also been speculated that these two sisters were the daughters of the Irish King Brian Boru, and that they fled to the European continent to do missionary work after the disastrous battle of Clontarf in 1014. However, there is nothing to substantiate this.)

According to Die Schottenchronik, the Schott family left Schotten in the late 12th or early 13th century and settled in other parts of Hessen.

Today Schotten is a modern town and well-known vacation spot for sports enthusiasts.

Sources:

Arnold, Friedrich E.G. Stammreihen der nassauisch-hessischen Familie Schott aus Eisemroth bei Dillenburg. Self-published, Hamburg-Blankensee, 1957. Available on microfilm 1181524, item 3, from the Family History Library in Salt Lake City. [This is one of the updates to Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s Die Schottenchronik. An incredible source of information on the village of Schotten and Schott family history from the year 1015 through the 1900s for many branches. This is primarily genealogical data with some written history, but shows all the Schott families that occupied Hessen through this time period. As you might guess from the title, it’s all in German.]

Cahill, Thomas. How the Irish Saved Civilization. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. New York, 1995. [More about the Roman Empire and the Irish than Germany, but it does give some background on why those Irish missionaries would have been wandering around founding the town of Schotten, Germany.]

Pieper, Von Hartmann and J. Reinhardt Schott, Jr. “Die “Schottenchronik.” Published sometime after 1960. [This is another version of Johann Schott von Schottenborn’s family history—this one is based on the original manuscript, rather than the F.E.G. Arnold version, which was based on a copy. These authors make a lot of the fact that the early Schott family history is based on oral tradition, and can’t be verified in any way and therefore, should not be relied on. They also claim that their version is much more accurate than the F.E.G. Arnold version because it’s based on the original, not a copy. While I certainly found some discrepancies, I would say these are minor. These authors, however, have added to the original with information from other sources, which makes this version more complete overall.]

Scott, Sir Samuel Haslam of Yews. “An Old German Family History.” The Ancestor (London, April 1903).

Scott, Sir Samuel Haslam of Yews. A True Relation by Johann Schott von Schottenborn 1587. Translation by Sir Samuel Haslam Scott of Yews. Oxford University Press, 1929. [An incredible find—I had seen references to this English translation of the Johann Schott von Schottenborn document by an English branch of the family, but had no idea how to get my hands on a copy. I finally found it in an Irish bookstore through a rare book site on the Internet—and they were more than happy to sell this to me. This book/manuscript is the basis for all of the really early Schott family history and the theories about how the Schott name came into existence.]