Carolyn Schott's Blog, page 4

January 18, 2016

A 36-Year Search for Cottage Cheese

At long last, I sampled Lithuanian cottage cheese in a blintz-like dessert in Klaipeda

I’ve wanted to visit Lithuania since I was a teenager. And for once, it’s not because of family roots.

My interest in this small Baltic country dates back to high school in the 1970s, when Lithuania was firmly locked away behind the Iron Curtain. In fact, the Soviet Union had so thoroughly subsumed it, I almost thought Lithuania was a mythical place, like Atlantis or a land called Honalee.

And then, somehow, somewhere, my 17-year-old brain learned that Lithuanians love cottage cheese. And my 17-year-old brain thought that was about the funniest thing in the world—that these mythical people could love something as prosaic as the cottage cheese that was plopped on my dinner plate as a side dish when my mom ran out of meal ideas.

This bit of trivia would be long forgotten, except that my 17-year-old self happened to be the news editor of the school newspaper. And I learned this bit of trivia just as we were working on our annual April Fools edition. And so one of our feature spoof stories became an article on the high school marching band traveling to Lithuania to march in the Cottage Cheese Festival parade.

Cottage cheese was everywhere – in the desserts and as bar snacks

Then tragedy struck. Our teacher refused to let us print it, afraid we would offend local Lithuanians. My 17-year-old self was indignant, arrogantly knowing that there couldn’t possibly be enough of these mythical creatures around to be offended. I knew this was censorship. The downfall of civilization was sure to follow. (My now adult self is highly embarrassed by my 17-year-old self and I apologize to Lithuanians everywhere for my thoughts.)

The teacher suggested a compromise—we’d use Curdania, rather than Lithuania, as the country name. But my 17-year-old self was a bit sulky, convinced the article wasn’t a worthy April Fools story with this edit. I used my editorial privilege to pull it.

(Of course, my current self is relieved by that teacher’s journalistic integrity as it prevented me from offending Lithuanians everywhere, which, I’ve discovered, include several long-time friends and my contact lens technician).

This journalistic drama has remained with me decades later, piquing my interest in Lithuania when most people, even today, can’t find it on a map. So when a friend invited me to visit her there, I was determined to seek out the truth once and for all. Do Lithuanians really love cottage cheese?

The answer is a resounding yes. Lithuanians do indeed seem to love their “varske.” Varske recipes abound. Restaurants serve it in dessert and in pancakes and as side dishes. Sellers at the farmers markets have different varieties.

Cottage cheese in Lithuania is not a laughing matter, any more than sauerkraut in Germany or spaghetti in Italy or potatoes in Idaho.

Trakai castle, not far from Vilnius, Lithuania

But I also discovered something so much more important—Lithuania is a country with a proud heritage.

The Duchy of Lithuania was a major power in Europe for five centuries (13th to the 18th), and the biggest kingdom in Europe in the 15th century, with great diversity in language, religion, and culture.

Lithuania’s declaration of independence in March 1990 created a domino effect among the other soviet republics … which ultimately resulted in the breakup of the Soviet Union. Lithuania continues to be feisty, one of the few EU countries to continually stand up against Putin’s aggression in Ukraine.

The shore of the Baltic Sea off the Curonian Spit

In addition to politics, basketball is big in Lithuania. When the Soviet Union won the Olympics gold medal in 1988, the majority of the team was Lithuanian. In 1992, little Lithuania’s first year to compete in the Olympics as an independent country, the Lithuanian team won the bronze.

Trakai, Lithuania

I went to Lithuania in search of cottage cheese because of a silly teenage experience. But instead I found that Lithuania is a country with beautiful nature, centuries of history, a love of sports, and a spirit to stand up for justice. I am humbled.

November 17, 2015

5 Reasons the U.S. Needs to Help Syrian Refugees

Photo courtesy of DFID (UK Dept for International Development) via Wikimedia Commons

I don’t usually write political posts, but all the controversy over whether to admit Syrian refugees into the U.S. has caused these thoughts to be burning on my heart. My day job is as a writer for an international humanitarian organization that cares for people in need, like these refugees. It breaks my heart that with all the privileges and comforts that Americans have, we would let our fear make us lose our compassion for people who are desperate.

1) When we talk about the Holocaust, we always say “We can never let this happen again.” But if we let our fear today cause us to treat Syrian refugees the same way the U.S. treated Jewish refugees during WWII, we have no moral high ground to judge. How many Jewish lives could have been saved if we’d opened our doors? How many Syrian lives can we save now?

2) I get the fear of letting in terrorists, but we need to think this through and look at the facts. Per the International Rescue Committee, a respected relief organization: “Refugees are the most security vetted population who come to the United States. Security screenings are rigorous and involve the Department of Homeland Security, the FBI and the Department of Defense.” Should we lose our humanity in our fear?

3) I get the sentiment of “But we need to help our own homeless and our disabled vets.” But how does helping refugees take away from our ability to help others in need? Who has suggested that if we help refugees, we’ll stop helping anyone else? Compassion is not a zero sum activity.

4) For those of you who are Christians, the Bible is pretty clear about how we are to treat those in need. “Now this was the sin of your sister Sodom: She and her daughters were arrogant, overfed and unconcerned; they did not help the poor and needy.” (Ezekiel 16:49)

5) Caring for refugees, giving them hope that they can rebuild their lives, is much more likely to make them productive members of society. Without that hope, who knows what sort of extremism they’ll turn to?

Stories of the children caught in this crisis

Strudels for Dummies

I don’t usually post recipes, but since there was so much interest in yesterday’s post about my baking powder dilemma and so many people desperately searching for this recipe, so here goes.

Now, I’m not calling you a dummy, but I certainly was when I first tried to make it. My mom didn’t really use recipes and mostly said things like, “You add water until the dough is right.” Right? What does that mean? It made sense to her, but not to me. So I decided to put together a recipe that spelled out every detail.

This recipe evolved over time, starting with shadowing my mom. But I could never get the dough stretching down until I got some lessons from my dad’s cousin Marie and she showed me an easier “beginner” method (holding the dough by the edge and letting gravity work for me rather than flipping it around on the backs of my hands like mom did). Once I found Aunt Idella’s recipe (that called for resting the dough), I made my first successful batch.

Strudels for Dummies

Strudels for Dummies(Start process about 4 hours before serving time.)

With strudels as your main course for heavy-duty strudel-eaters, I usually estimate about 1 cup of flour per person. So this recipe serves about 3. If you’re having other dishes, or you’re more “average” strudel consumers, you would adjust accordingly.

Ingredients:

3 cups flour

2 eggs

2/3 cups warm water (I usually end up adding a little more water to make the dough the right consistency)

1/8 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon baking powder

Oil

Potatoes, cut into large chunks.

Chopped onions (to cook with the potatoes)

Gravy (however you choose to make it – package or from scratch)

1) Mix eggs, water, salt. Add flour & baking powder to make soft dough. (Be careful that it really is a soft dough, too much flour makes the strudels tough. If it’s annoyingly sticky, it’s about right.)

2) Let the dough rest 1 ½ – 2 hours (longer is better).

3) Divide the dough into 3 parts.

4) Let dough rest about 30 minutes.

5) Roll out each ball of dough. Pour small amount of oil (don’t use melted butter) in the center of piece of dough. Fold edges into middle to cover the entire top of the dough with oil, but let it lie flat. (Basically, you just want to let the oil help soften up the dough for stretching.)

6) Let dough rest about 15-20 minutes. At this point, start cooking the potatoes and onions slowly so the water will be simmering by the time you’re ready to put the strudels in the pot. (Some people also cook their meat in this pot and if so, you’ll want to start it sooner. I usually do my meat separately to simplify the timing of it all.)

7) Stretch dough until paper thin, either on the backs of your hands flipping it like pizza dough, or just by holding the edge and letting gravity stretch it. The oil makes it stretch pretty easily, sometimes too easily! When it gets hard to handle, I lay it down on a large cotton dish towel and stretch the edges out a bit more. It’s not the end of the world if it tears some…main thing is to get it stretched thin everywhere, even the edges.

8) Start rolling one edge of the dough, then pull the dish cloth up to let the dough “automatically” roll up.

9) Cut into approximately 2” lengths. Lay strudels on the top of the potatoes; the water should already be boiling. Try not to let strudels lie on top of each other and keep them from being completely submerged in the water. The potatoes should act as a “platform” for the strudels to lie on and steam. Cover and cook ½ hour without taking the cover off.

10) Serve with gravy and any meat dish you might choose to add.

Voila! A scrumptious Black Sea German treat!

November 16, 2015

Cooking in the Footsteps of My Ancestors

My mother was always blunt, or “direct” if you want to be polite. I learned to live with comments like, “Well, that hairstyle doesn’t look good on you,” or “You just have no sense of style,” (when I preferred my own tailored look to her more flamboyant, sequin-bedecked clothing suggestions).

So it didn’t really surprise me when she looked at her plate one Christmas day and said, “These aren’t right.”

She was looking at the strudels I’d prepared, based on her own recipe. Little pockets of fluffy, dumpling-like goodness—tossed in the air until they’re tissue paper thin, rolled up and steamed over potatoes, and then served with gravy, sauerkraut, and North Dakota sausage. A delectable treat for anyone who grew up in a Black Sea German home. They were my favorite of all the German dishes my mom cooked when I was growing up. I’d spent years learning to make them myself, including coaching from my mom, my dad’s cousin (for effective dough stretching techniques), and my Aunt Idella.

She was looking at the strudels I’d prepared, based on her own recipe. Little pockets of fluffy, dumpling-like goodness—tossed in the air until they’re tissue paper thin, rolled up and steamed over potatoes, and then served with gravy, sauerkraut, and North Dakota sausage. A delectable treat for anyone who grew up in a Black Sea German home. They were my favorite of all the German dishes my mom cooked when I was growing up. I’d spent years learning to make them myself, including coaching from my mom, my dad’s cousin (for effective dough stretching techniques), and my Aunt Idella.

“What’s not right?”

“These. They’re sort of hard.”

Well, they tasted the same as always to me. When I pointed out that this hadn’t prevented either of us from eating a plateful (I could be direct, too), the conversation ended. Until the next day.

The phone rang and when I answered it, the voice on the other end said, “Baking powder.”

It took me a moment to realize this wasn’t the typical approach of a telemarketer and that it was my mother’s voice.

“How old is your baking powder? That’s it. That’s why they weren’t right.”

She obviously had been stewing on this all night. But I confess, I was a little annoyed with the “not right strudel” conversation, so I rolled my eyes, promised to check, and hung up. Later that morning, when I got around to making good on my promise, I discovered that my baking powder was past its expiration date—by seven years. Woops.

Fast forward to yesterday. It was a cold, rainy weekend in Seattle, and strudels seemed like the perfect antidote. Another important factor was that I planned to be home all day. The strudel recipe calls for the dough to rest a lot, so you have to be nearby to tend it.

I’ve learned to check my baking powder these days, and sure enough, mine was expired. But only by a month and I didn’t want to run to the grocery store. I decided it was still fine.

But it wasn’t. My strudels did not live up to my mother’s, aunts’, or grandmothers’ cooking. Probably not my great-grandmothers’ either, but I never had a chance to try their strudels for myself.

Baking powder seems to be my Achilles heel of strudels. I can just sense the disappointment of centuries of Black Sea German ancestresses. I’m sure they whipped up a pot of strudels for the family dinner, flipping the dough up in the air while doing laundry with the other hand and tending small children underfoot.

They created doughy goodness in their primitive kitchens—no running water, wood-fired stoves, a cellar across the yard providing the only refrigeration. By contrast, my kitchen is 21st century elegance—granite tile, gas range, stainless steel appliances, and lots of doodads that peel, core, and chop. And yet, I was foiled by baking powder.

I’ve often visited my ancestral towns to walk in the footsteps of my ancestors. But I still struggle to cook in the footsteps of my ancestors. Sigh. Off to the store for more baking powder.

September 20, 2015

A Genealogist’s Hog Heaven

True meets her genealogy mentor, Dean Spratlan

Guest blogger True Lewis blogs about family history. Her blog is a personal diary about her slave Granddaddy Ike Ivery and the Miles Daniel Family. Along with her mother’s European heritage, her ancestors come from Bullock County, Midway, Alabama, and Houston County, Georgia. With strong roots in Cumberland County, Newville, Pennsylvania, she’s been blogging for three years as of November 7.

I had been pondering what to do with all my genealogical research. I had helped create the family website along with my cousin Lisa. I wanted to take it to another level as I was always talking to people one on one trying to explain. I needed a format to keep the conversation going, find a visual where all can see the names and dates. This is how I got started on my documentary for my family history at our ancestral home.

Sweet Home Alabama

On a sunny Monday morning, October 3, 2011 I started my journey to Sweet Home Alabama. Prior to all this, I did much preparation as I could, but sometimes in our research, one has to go to their ancestral place of origin to get information that you just can’t do over the Internet. It was also a personal journey for me after my parents passed in 2008 and 2009; their souls are resting.

I arrived in Birmingham and went to the New Grace Hill Cemetery, which on a 1946 death certificate was called Mason City Cemetery—three weeks of trying to find its location and the history. I was there to locate one of Daddy’s brothers named Rev. Obie Lewis.

Next it was on to Bullock County, Midway and Union Springs. This is where my earliest ancestor William, 1812, and Minty (Ivey) Ivery, 1834, were to make their roots. They seemed to start using Ivery after Emancipation even though I have both spellings on documents. At times during my visit I felt like was taking a step back into time. Not much had changed.

The Bullock County Courthouse

I went to our family church, Mt. Coney Missionary Baptist, which was founded in 1875. I’d written for permission a month in advance to videotape the church. Pastor Robbins was more than welcoming and very accommodating. He gave the history on the church and cemetery, which is where a lot of my ancestors are buried.

Ike Ivery is my great-grandmother’s father. I find it ironic that Granny Eddie is buried right beside her father, which was befitting from all the stories I have been told about how close their relationship was when they were living.

I got to spend two wonderful days in the Bullock County Courthouse, which houses a lot of my family documents, in just-beyond-belief research. I have so many letters and envelopes from the courthouse that I was in “Hog Heaven,” as my mom would say.

I enjoyed walking around and going through all the index and map plat books, marriage registers, and the old Union Springs Herald. All the times I had been down home, I was now seeing it through a different pair of eyes. I thoroughly enjoyed the rich history and town.

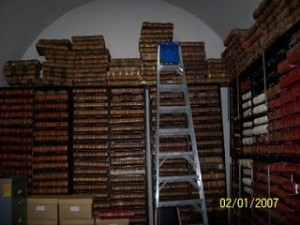

I rummaged through a lot of books that you had to actually walk to flip the page over because they were so huge. I saw books I wouldn’t have been exposed to over the Internet. It was something you have to go there to experience.

I was a dust bowl by the time the day was over, my calves were sore from climbing the ladder to get at some book tucked up high, but I couldn’t get enough.

The Alabama Department of Archives and History was on my bucket List. I finally made it! I’m also a card carrying member of the Alabama Genealogical Society. Beyond Words. I shed a tear when I got there, how silly!

After almost eight years of corresponding over snail mail, I finally got the pleasure and honor of meeting my mentor, Mr. Dean Spratlan, who is the president of the Bullock County Historical Society. This man has taught me patience in doing family research. He shared so much with me over this time I will be eternally grateful.

Mouthwatering goodies for a genealogist! (i.e. old records in the courthouse)

Time With Family

I also learned things from all four of my aunts, ages of 80 to 95. The oral history they gave me was invaluable; all the talking over the phone was nothing compared to sitting and fellowshiping with them in person.

A casual conversation with my cousin led to finding a book written by a family member: Glimpse of Providence: “A Black Boy’s Experience in Foreign Lands” by Isaac Robbins that describes a black soldier’s life in Midway, Alabama. Who Knew?

Another highlight was finding my own father, James E. Lewis, mentioned in the book, “In Freedom’s Name: The War Years 1941-1945 WW2 Bullock County Veterans” about soldiers in World War 2. Another genealogical gem is the book, “Soldier’s and Sailor’s Discharge Records for Bullock County,” which Mr. Spratlan personally signed the book for me as he was a part of the research in 1996 when this book was written.

Heading home

This trip was not only good for my research, but it did my soul good as well. I needed to go walk the land, see and smell and get a feel for what life might have been like for my ancestors, but also for the family who haven’t left there.

As I was leaving Alabama on County Road 82, a truck full of cotton was leading the way. At first I didn’t know what it was blowing all over the place like snow, but then I pulled over and took some home with me, along with a bag full of pecans from my 91-year-old Aunt Sallie Bea.

I also got some Alabama red dirt, that in the following week I took to Pennsylvania to place on my parents’ grave. They were born and raised in Midway, Alabama, they might have been part of the Great Migration and left Alabama but Alabama never left them.

As the sun was going down, I was leaving town. I hated to leave. I started reflecting and I felt an inner peace like no other, like the ancestors were riding with me. I started to see their faces in everything driving down that highway. With what sun was left on the horizon blaring in my eyes, I felt like my “people” were smiling on me from above.

A song came on my radio called “Secret Place” that was right on time and appropriate for my documentary; it was just what I needed to make it complete.

I just let the tears fall from joy.

The finished work on my documentary can be found at: Granddaddy Ike to True’s Story!

Read more In Their Footsteps posts.

September 17, 2015

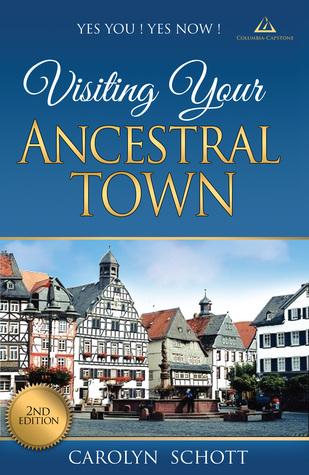

Enter to Win!

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Visiting Your Ancestral Town

by Carolyn Schott

Giveaway ends September 24, 2015.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

September 14, 2015

You Can Go Home Again

Scott on the ramparts of Battle Abbey

Guest blogger Scott Billigmeier is a California native who has lived in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. for 25 years. He’s been researching his genealogy for 30 years. Scott is a strategic account executive at Symantec (Veritas) focused on the U.S. public sector. He received his B.A. from U.C. Santa Barbara and has done Masters-level course work at U.S. Army War College and The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. He is married and has twin daughters who are currently attending college.

It was a bright, crystalline day in southern England. The kind that you can never set your watch by but when they come, oh my, they are brilliant. Warm but not hot, and mediated by a fresh, exhilarating breeze that keeps the occasional wispy cloud moving jauntily across the sky.

This was the day that found our family heading to the southern coast and the ancient town (now city) of Hastings. My mother’s maiden surname was Hastings and it had always been supposed, without a great deal of thought, that this place was where our people came from sometime in the distant past.

Most of what my mother and her family knew and passed on (which wasn’t much, with one great exception) turned out not to be true or was completely wanting of any evidence. In the case of Hastings though, it remained plausible and the evidence was helpfully scant (if you wanted to believe) before the 17th century. All we knew for sure was that our immigrant ancestor left Ipswich, Suffolk, in April 1634 for the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

As an amateur genealogist coming up on 30 years, I knew a surname had to come from some place or characteristic and if you were lucky enough to have one based on a location such as Hastings, that was a natural place to look.

The ruins of Hastings Castle. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Hard living in Hastings

Hastings has been pillaged, burned, rebuilt (repeat several times), and bombed during two world wars. Over a millennium of hard living had taken place in that coastal spot. Even the once remarkable port wasn’t viable any longer and hadn’t been for 600 years. The ancient Hastings Castle, which sits on a hill overlooking the old town, has mostly fallen into the sea. The tidal line has been rather elastic over the centuries covering or eroding the lower recesses of town. All of these things conspired to lower our expectations for what we might find.

And so it was that I found myself approaching Hastings on the A21 and admiring the beautiful countryside. The road is being turned into a motorway which will make Sussex more accessible, but is disturbing some fine views. High-speed rail is also planned, which will make the commute to London, where housing is tight and ultra-expensive, much more reasonable. Depending on one’s perspective then, the area is either on the cusp of a renaissance or obliteration.

I tend to think that making Kent and Sussex more accessible portends unwanted and unstoppable change so I was glad to be visiting now before it’s too late. In fact, as we passed signs for Churchill’s Chartwell, Kipling’s home known as Bateman’s, and numerous castles and abbeys, I wished I had made the trip a decade or two earlier.

Seashore at Hastings

First impressions

We arrived in Hastings and found our surprisingly chic accommodation just off the High Street in the small, old town nestled between the castle ruins and an adjacent cliff that has been set aside as a park. First impressions were positive (especially those of our twin daughters) and they mostly held during our four-day stay.

Hastings today, and for probably as long as anyone cares to remember, is about the seashore. It is a resort area with a strong fishing tradition. To my surprise, virtually everything about the Battle of Hastings has been relegated to the nearby battlefield, the majestic ruins of Battle Abbey that sits on the place where King Harold was supposedly slain, and the town of Battle that sprung from history’s fertile soil.

For these reasons and others I suppose, I felt strangely detached during our visit; more tourist than amateur historian or genealogist. I attribute that to the speculative nature of the family connection to Hastings and Sussex—logical, plausible, but unproven and unprovable at this remove.

Exploring Hastings

The historic core of Hastings is better preserved than I expected with exception of the sad old castle ruin. Buildings dating back to around the 14th century are mixed in with later creations. The medieval churches of All Saints and St. Clement’s provide the religious continuity that is lost on most of today’s inhabitants and visitors. The bomb damage from World War II is only apparent in a few places and, interestingly, it’s attributed to “enemy” (not German) bombers. One mustn’t agitate the continental tourists!

Pub in historic Hastings

Walking down the narrow High Street toward the English Channel is a short but pleasant stroll. George Street is on the right and it’s arguably the epicenter of Old Town. It shares and amplifies the characteristics of Hastings and most seaside resorts in the U.K.—attractive but a bit shabby, aromatic in a way that harkens back to the days of chamber pots, and striving for something greater than the sum of its parts or perhaps the halcyon days when people traveled here to take the water and enjoy the spas. We enjoyed George Street and were often drawn back to it, but we were always careful where we stepped and, like anywhere in Hastings, aware of the ever-present dive-bombing seagulls.

Hastings isn’t a place that venerates its past for any reason other than to propel itself to a more prosperous future. If you’re in town to see the sites of the BBC’s Foyle’s War or where the Rockers and the Mods were whipped into a frenzy by the Rolling Stones in 1964, then you are in luck!

I didn’t come to Hastings expecting or even hoping to find things of direct family relevance. Sometimes you just have to go and get the vibe of the place and that I did. As for emotional connection, it was akin to visiting my ancestral village in Germany. I knew my ancestors had lived there and yet their imprint was indiscernible or long ago erased if they ever left a mark.

A contrasting ancestral visit was to eastern and central Massachusetts several years ago. Family still lived in the area, three hundred year old family homes still stood and everywhere I turned, there seemed to be a road or a hill named after some ancestor. That is what we all hope for when we make such a trip “home.”

As for Hastings, it was and is an incarnation of home. If one takes time to reflect, it is what you make it to be through the mist of the past.

(Read more In Their Footsteps stories)

September 10, 2015

Once in a Lifetime

Merv (along with translator Inna) speaks at Lymans’ke’s 200th anniversary celebration.

Merv Weiss began researching his family’s history in the year 2000. All four of his grandparents were ethnic Germans (Catholic) who were born in a region that was once Russia (now Ukraine). His paternal family has roots in the Odessa region, his mother’s family in Crimea. Merv recognized that genealogical research requires a good foundation in the history and geography of one’s ancestral regions, and has visited Ukraine six times. He’s also visited Weiss relatives (Spätaussiedler) in Germany numerous times. His greatest satisfaction in genealogical research to date has been meeting his “new” cousins in Germany. Merv grew up in southwestern Saskatchewan, and lives today in Saskatoon.

The expression “once in a lifetime” is perhaps over-used, but Sunday, 21 September 2008 was, for me, truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience. After all, a 200-year jubilee can only occur once. The year 2008 marks the passage of two hundred years since the first Rhineland Germans ventured into the Kutschurgan Valley, Odessa district, having been enticed there by the promises of Tsar Alexander I. The Germans built six villages there, which served as the foundation of their culture and Catholic faith for 136 years. The central economic and administrative center for those villages was the village of Selz, today called Lymans’ke.

Selz is special for me, because it is the birthplace of my father’s parents. My grandparents married there and had three daughters before they immigrated to Canada in 1913, the peak year of outward migration of Germans from South Russia. They sang in the choir of that great cathedral, the Church of the Assumption, which today exists in a sad state of ruin and neglect. My grandmother’s direct ancestor, Michael Fetsch, was the first mayor of Selz, and her second cousin, Alexander Fetsch, was the last German mayor of Selz. Selz was home to the Weiss and Fetsch families for five generations before my grandparents, Konrad Weiss and Brigetta Fetsch, decided that the unknown of North America was a better option than the growing turmoil of South Russia.

Merv is greeted with the traditional Ukrainian gift of bread and salt by Lymans’ke’s mayor, Mr. Zharikov.

Selz has survived, but it has endured much. Once considered the most prosperous German colony in Odessa district, the village today looks poor and beaten down, by North American standards. It still holds bitter memories for those Germans whose families remained behind. There are many yet who remember the onslaught of a new economic order in the 1920s, the persecutions and banishments of the program to collectivize agriculture, the Holodomor or great famine of the 1930s, Stalin’s great terror campaign of 1937/38, and the final abandonment of their villages in 1944. I can feel the burdens and pains of those years still today as I walk the streets of Lymans’ke. The tired-looking homes still seem to weep for their former German inhabitants. The flocks of ducks and geese wander and quack and honk, as if they still wonder, “Where did they go?”

My visit in 2008 was my fourth to my ancestral village, and I now enjoy the comfort of familiarity when I am there. I was in Selz on this day to help the village celebrate its two-hundred-year jubilee. I remember reading Konrad Keller’s description of the Kutschurgan villages in 1908 when they celebrated the toils and accomplishments of 100 years of German colonization. I imagined the pride the Selz people must have felt for their new and beautiful cathedral. But throughout the day I could not quit thinking about the sad and tragic history of the second one hundred years, as those Germans were beaten into serfdom and dragged through thousands of miles of Europe and Siberia and Asia. But this was 2008, and I was in Selz, and we were there to celebrate.

Light rain throughout the day, following a week of rain, obscured the many preparations by the residents of Lymans’ke to clean up their town, to clean up the church grounds, to put up anniversary banners and balloons. But it was obvious from the moment we arrived on Sunday morning that this was no ordinary day in Selz. People with and without umbrellas were wandering everywhere on the streets around the old church. Inside the church, several hundred people had gathered, waiting to celebrate Holy Mass. Once again, the cathedral walls echoed with the liturgy and the songs of the Holy Mass in German and Latin. And as I received Holy Communion, how could I not think about my grandparents doing likewise in the very same spot?

Merv receives communion in the cathedral where his grandparents had married.

The church service may have started late, but the parade band struck out at precisely 11:00 am, interrupting my reverie inside the church. We followed the band to the “Palace of Culture,” an old Soviet term for what we would call a community theatre. An extensive program of entertainment interspersed with presentations and speeches would fill most of the afternoon. People stood in the aisles and entrances long after the five hundred seats had been filled. I was one of the several guests of honor, presented with the traditional loaf of bread and salt (called korovai) on a cloth. I was interviewed by television and newspaper reporters from Odessa and Kyiv, interested in speaking to a North American descendant of original Selz colonists.

When it was finally my turn to speak, there were many things I wanted to say. Of course, most of the day’s program reflected the area’s Ukrainian and Russian character and history. But I was very grateful that the people of Lymans’ke were recognizing the German colonists who first ploughed this land, and built this village. What I wanted most to say was to tell the people that my grandparents loved Russia. They did not leave because they hated Russia. Russia was their motherland, but when they recognized the changing character of Russia’s internal politics, they left. They left for a huge unknown on the Great Plains of North America, and the new beginning had many challenges and obstacles to overcome.

And I wanted to tell the people of Lymans’ke, that even though I was born in Canada, my roots have led me back to the Kutschurgan Valley. I am as German as the people who came to this valley in 1808, and I am as German as the Germans who were forced to leave this village in 1944. This history is part of who I am, and I want my children and my grandchildren, and the people of Lymans’ke, to understand this about me. This history is why I came back to Selz to celebrate this jubilee. I am grateful that the friends traveling with me were able to share the day with me, and I know that they understood the relevance this day held for me. It is my hope, that in another 200 years, the people living in Lymans’ke will still remember the Germans who first colonized the Kutschurgan valley, and who built the village of Selz.

September 9, 2015

In Their Footsteps

As I talk to people about my book, Visiting Your Ancestral Town, I get to hear so many great stories from people who have traveled to their own ancestral towns. So I thought it would be fun to give people a place to share their experiences.

I’ve started a new section of my blog called In Their Footsteps where I’m inviting guest bloggers to tell their stories about visiting places where their family once lived. If you’ve got a story, I’d love to hear from you!

Stories should be no longer than about 1,000 words. (Though if you have a hard time telling your story in that length, send it on to me anyway and we’ll work it out.)

Stories should include at least 3 photos that go along with the story

Please include a short bio of you (about 50 words)

Send everything to me at carolyn[at]carolynschott.com (Of course, substitute @ for [at] – this is just my low-tech way of foiling spammers.)

Let the stories begin!

First World Problems

Wifi purchased in 1/2 hour increments with indecipherable passwords.

Daily life can be filled with irritations. The technical support people who seem to know less about their product than I do and therefore offer little support. The barista who makes my frappucino in slow motion while talking in fast motion to her co-workers about her car troubles. The hidden app on my new smartphone that gobbles up data usage.

But two weeks in Africa gave me some perspective. It made me think about all the things that just happen seamlessly in my daily life that I never appreciate not being irritated by.

Every morning, I don’t really appreciate the steady stream of hot water that comes out of my shower—not cold water, not just a trickle that you’re unable to bathe with, not a wild spurting of water that soaks down everything in the bathroom. My shower at home never irritates me.

I don’t really appreciate electricity like I should. I don’t appreciate that when I flick on the light switch in the middle of the night, there is light. I don’t appreciate enough that I never have sudden moments where everything goes dark and I have to freeze in place trying to remember how to navigate through utter darkness to get to the nearest flashlight. Electricity at home never irritates me.

I don’t really appreciate the availability of wifi. I’m writing this at a coffee shop with a strong wifi signal, just as good as I have at home or at work. I don’t appreciate enough that when it shows a strong 5-bar signal, I actually have a strong signal (vs. flickering instantaneously over and over between 5 bars and nothing). I don’t appreciate the fact that wifi is free everywhere I go, rather than having to pay for it in 30-minute increments that only last 20 minutes, then having to re-log in each time by reading a nonsensical 5-point-font faded-ink password off a tiny receipt slip to gain another 30 minutes of access.

In my everyday life, I don’t appreciate enough that problems with slow baristas and fancy phone apps are first world problems that people in the developing world can’t even imagine being irritated about. They seem to accept, with a patience I find unimaginable, how to navigate life without reliable water or electricity or wifi.

It gives one perspective.