Carolyn Schott's Blog

April 19, 2023

Navigating Moldova Poll Tax Census Records

I’d heard the siren call of this unexplored group of records for many years. There was almost a fairy-tale-like quality to the promise of this collection—all riches could be mine (in the form of genealogical records) if I could just figure out how to find anything in the “Moldova Poll Tax Census (Revision List)” collection on FamilySearch.

I’d heard the siren call of this unexplored group of records for many years. There was almost a fairy-tale-like quality to the promise of this collection—all riches could be mine (in the form of genealogical records) if I could just figure out how to find anything in the “Moldova Poll Tax Census (Revision List)” collection on FamilySearch.

But it was daunting. The collection has nearly 400,000 images, no index, and is poorly catalogued. One of my targets was a specific village’s 1850 revision list. (Revision lists are tax lists of people in a certain village. They’re often used as and called censuses because they list all members of the household with their ages.)

But how to find it? Would a revision list for a village in Bessarabia be under the “Bessarabia Gubernia [Province]” heading (since it’s a type of record kept nationally) or under the “Kischinev [Chisinau]” heading (since the village was in that district)?

Having chosen the Kischinev option, I was confronted with 19 screen pages of links with names like “1802-1872 vol 3” (no information on the type of record or location). Where does one even begin?

Any of the 120 links marked “1850 vol __” could be what I’m looking for. Or they could be a completely unrelated type of 1850 record. And since revision lists are often updated over a couple of years, any of the 46 links with names like “1849-1851 vol 25” or “1850-1867 vol 454” were also possibilities. That’s a lot of records to comb through trying to decipher handwritten Cyrillic (which I am still a novice at reading).

Fortunately, I found some clues, so you don’t have to!

Tips for navigating this collection

FamilySearch screenshot

1) When you click on a link (for example, the one named “1796 vol 1399”), the first image you’ll see, the title page, shows the Moldova National Archives’ collection/inventory/case number (aka fond/opis/delo or фонд/опись/дело or фонд/опис/справа, depending on the language you’re working with). After clicking on “1796 vol 1399,” we’ll see that this set of images is from Fond 3 Opis 1 Delo 1399.

2) The Moldova National Archives site has a catalog of all their holdings. By following the links on their website, we find that the description of Fond 3 Opis 1 Delo 1399 is “документъ удостоверяющие помещиков оргеевского уезда хинкуловъх в дворянском сословии (копии)” or (using DeepL to translate) “Document certifying the landlords of Orhei county Hinculov as members of the nobility (copies).” So even though FamilySearch doesn’t describe what’s included for each link, cross-referencing with the Moldova Archives’ catalog makes it fairly easy to figure it out.

3) Important to note – the “vol” listed in the FamilySearch link corresponds to the delo or case number. This isn’t a surefire way to find anything (because there could be a case 1399 in other fonds too), but it’s a useful clue.

4) Here’s a tool to help you identify the fonds included in each of the main categories shown on FamilySearch with links to the descriptions in the Moldova National Archives catalog (some in Romanian, some in Russian).

So where are the revision lists?To me, the juiciest documents in the “Moldova Poll Tax Census (Revision List)” collection are the revision lists. They seem to be in Fond 134 Opis 2. Here’s the catalog listing for Fond 134 Opis 2 from the Moldova National Archive.

To find a revision list for any village in Bessarabia (skip to next section if you’re mostly interested in German villages):

1) Find your village in the catalog listing. (Note that villages are spelled with the Romanian equivalent of their name, so you might have to do some creative searching.)

2) Identify the case number.

3) Search on the page for Kischinev for that case number (will be listed as the volume). Click and voila! You’ve found your revision list.

German villages in Bessarabia:If, like me, your interest is mainly on German villages, I’ve created a cheat sheet of links to make it super simple to find revision lists. Keep in mind – these are the original documents, so they’re in handwritten Cyrillic. (The Germans from Russia Heritage Society has translated/published some of these if you aren’t up for reading old Cyrillic. But there are many in this collection, especially from 1859, that have not been translated.)

On the cheat sheet, find your village, find the revision list you want (you have 1835, 1850, and 1859 to choose from), click on the link, and you’re ready to start hunting out those ancestors.

One tip: If there are multiple villages listed for one set of images (for example, the 1835 revision list), open the Moldova National Archives catalog for Fond 134 Opis 2, then go to the page number shown in the “Inventory Page #” column of the cheat sheet. That shows the page number within that case where your village’s revision list starts.

If you’re into handwritten 19th century documents for Bessarabian villages – the world is now yours! Happy hunting!

February 5, 2023

Stumpp Book Quirks Strike Again

You find the darndest things in the Stumpp book. It’s a classic and almost beloved reference work for those researching their German ancestors who settled in the Russian Empire. It’s also infuriating for its gaps and sometimes just plain wrong information.

You find the darndest things in the Stumpp book. It’s a classic and almost beloved reference work for those researching their German ancestors who settled in the Russian Empire. It’s also infuriating for its gaps and sometimes just plain wrong information.

And then other times, it’s…well…quirky.

Lists of Odessa City GermansWhen Glueckstal researcher Tom Stangl first suggested to me that the Stumpp book’s Odessa City list of craftsmen, which is clearly dated 1814, morphed into an 1858 revision list (aka census) halfway through and without warning, I thought it was wishful thinking on his part, grasping for records that don’t exist. But then I looked into this more closely.

The description of the list says it includes German craftsmen who settled in Odessa in 1814, with the following details: 1) Name of the craftsman; 2) “Soul count” or number in the family, with number of males, females, and total; 3) Number of workers over the age of 12; 4) Number of houses; 5) Occupation. Here’s a typical entry:

Original German:

5. Geisinger, Johann, Schneider, m. 1, w. 1, zus. 2, über 12 J. 2, Haus 1.

Translation:

5. Geisinger, Johann, tailor, males 1, females 2, total 2, over 12 years old 2, houses 1.

The list in the book includes 311 family entries and the sequential numbering alone seemed to indicate that it’s a consolidated list from one time period. But a funny thing happens at family #186—under new subheadings of Kaufleute and Kleinbürger [Merchants and Petty bourgeois], the format changes dramatically. Instead of sparse numerical data, we get a full family description consistent with the information typically included in revision lists. Here’s an example:

Original German:

191. Christophor Christophor’S Wirich 55, seine Frau Katerina Friederike Nikolaus’T 49, seine Söhne Friedrich Franz 21, Bernhard-Heinrich 17, Wilhelm-Philipp 12, sein Bruder Peter 36.

Translation:

191. Christophor Wirich, age 55, son of Christophor; his wife Katerina Friederika, age 49, daughter of Nikolaus; his sons Friedrich Franz age 21, Bernhard-Heinrich age 17, Wilhelm-Philipp age 12; his brother Peter, age 36.

Entries 1 through 185 (let’s call that Section 1 of the list) do look like one set of data, and entries 186 through 311 (Section 2) look like a completely different set of data. Section 1 also follows the common revision list practice of showing single people and orphans at the end of that section (entries 127 through 185). This is another signal that Section 2 really is something completely different that was tacked onto Section 1.

What year is it?OK, but is Section 2 really from 1858? It doesn’t say that anywhere. So I did a test.

Of the 128 families shown in Section 2, 30% of them (38 families) show up in the family registers of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Odessa. I wasn’t surprised that not all families were included in that one church as it was likely that some families in Section 2 could be Catholic.

For these 38 Lutheran families, I compared the names and ages in Section 2 of the Stumpp book list with their expected ages as of 1858 based on the information in the St. Paul’s family register. I found that 58% of these families matched with reasonably explained differences. For the 42% that I counted as not matching, the problem was usually that there wasn’t enough information or so many children were missing from the family list that I couldn’t state with confidence that it was the same family.

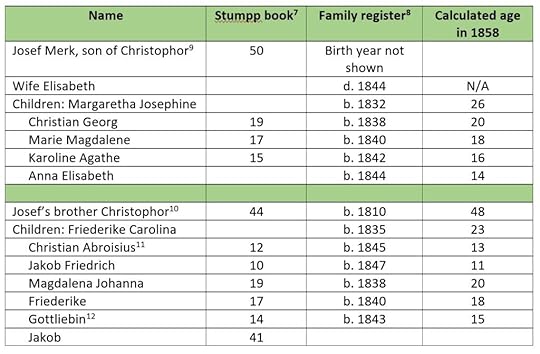

Here’s just one example of a matching family:

The consistency of names and ages makes it clear that the Merk family listed in the Stumpp book and the Merkt families in the family register are the same. Comparing the age of each individual as listed in Section 2 with their expected age in 1858 as calculated from their birth information in the church family register, almost all are consistent with a date of 1858-1859 for Section 2.

Of course, there are some differences. Josef’s daughter Margaretha Josephine and Christophor’s daughter Friederike Carolina are missing from the Section 2 list but are of an age when they were likely married and included under their husbands’ names.

The exclusion in the Section 2 list of Josef’s daughter Anna Elisabeth, age 14 in 1858, is more of a mystery, unless she died and her death somehow didn’t get recorded in the family register. The family register includes three children—Catharina, Catharine, and Eduard—who died before 1858, making it reasonable that they wouldn’t appear in the Stumpp book Section 2. Section 2 also lists a Jakob Merk, age 41, as the son of Christophor, age 44. Clearly, that is impossible and Jakob is more likely to be a brother of Josef and Christophor. It’s unknown why he wouldn’t be listed in the St. Paul family register.

Still, these are minor discrepancies compared to the consistency of names and ages that exists. Based on the ages in this example, as well as the other 37 families that went to St. Paul’s, the data in Section 2 of the Stumpp book list was probably recorded about 1858 or 1859.

ConclusionThe significant change in type and format of data between Section 1 and Section 2 support the theory that the data was collected at different points in time. The correlation of families and their ages in Section 2 with data from the local church register makes it certain that the data in Section 2 is indeed from 1858-1859 rather than 1814 as the description of the list shows. Whether or not it is a transcription of the official Odessa City 1858 revision list is unknown (as that document has never surfaced), but the type of data included in Section 2 is consistent with data included in other revision lists of that time.

So yes, the list that is clearly marked 1814 does morph into an 1858/59 list. What can I say? The Stumpp book is quirky.

_________________________________________________________________

All translations from German are by the author. Because this blog post is about historical times when the city was controlled by the Russian Empire, the spelling Odessa will be used rather than the spelling of Odesa, which is correct today.

[1] Karl Stumpp, The Emigration from Germany to Russia in the Years 1763-1862 (Lincoln, Nebraska, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, reprinted 1997).

Karl Stumpp, “Odessa” in The Emigration from Germany to Russia in the Years 1763-1862 (Lincoln, Nebraska, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, reprinted 1997), p. 958.

Stumpp, “Odessa,” p. 958, family 5, Johann Geisinger.

Stumpp, “Odessa,” p. 965, family 191, Christophor Wirich.

Karl Stumpp, “Neudorf Revisionsliste 1816” in The Emigration from Germany to Russia in the Years 1763-1862 (Lincoln, Nebraska, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, reprinted 1997), p. 699-704. This is an example of a revision list showing single people at the end.

“1833-1860 St. Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church Family Book” in Odessa St Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church: Church Registers, translated by Germans from Russia Heritage Society (Bismarck, North Dakota, 2001); citing file 630-1-355, State Archives of Odesa, Odesa, Ukraine.

[7] Stumpp, “Odessa,” p. 965, family 204, Josef Merk.

[8] “1833-1860 Church Family Book,” St Paul Lutheran Church, p. 47 Joseph Merkt family and p. 58 Christian Merkt family.

[9] The surname in the family register is Merkt.

[10] The name in the family register is Christian rather than Christophor.

[11] The name in the family register is spelled Christian Ambrosius rather than Christian Ambroisius.

[12] The name in the family register is Gottliebine.

August 19, 2021

Travel in COVID Times-Part 1

It took me at least a month of deliberation to decide to launch myself out into the world during a global pandemic. Decision made, I’m embracing it as a new type of travel adventure. I just hope it doesn’t turn out to be a broke-my-foot-in-Bosnia-type adventure or an abandoned-in-a-dingy-Slovakian-train-station-at-night-type adventure.

It took me at least a month of deliberation to decide to launch myself out into the world during a global pandemic. Decision made, I’m embracing it as a new type of travel adventure. I just hope it doesn’t turn out to be a broke-my-foot-in-Bosnia-type adventure or an abandoned-in-a-dingy-Slovakian-train-station-at-night-type adventure.

Trying to figure out the requirements for entering another country is a Byzantine labyrinth of websites that contradict and describe so many exceptions that you lose track of whether you qualify or not. I flashed back to learning about nested if/then/else statements in my BASIC computer programming classes in the 1980s. Despite being a reasonably intelligent person, I gave up and decided to get tested in addition to being vaxxed, though I’m not really sure that was necessary.

Arranging a test was no less confusing. I arrived at the airport testing site at 7:45 for my 8:45 appointment because their website insisted that all times were in Mountain (rather than Pacific) time. That seemed bizarre, and even their customer service number provided no insights: “We’re just the call service. We don’t really know anything.”

Not surprisingly, I needed to wait until 8:45 Pacific for my test, but a nearby Starbucks and my Kindle app staved off airport boredom.

Testing options abound, but deciding on the right COVID test required understanding all those contradictory websites. How does it even make sense that one test for travel only guarantees results in 96 hours when it’s standard for countries to want tests that have been done in the past 72 hours? Has anyone done that math?

The path of least resistance (though plenty of $) seemed to be testing at the airport. Since they do it all the time for people traveling all over, they had to know the right test, right? The guy next to me traveling to Italy (another EU country) seemed to think so.

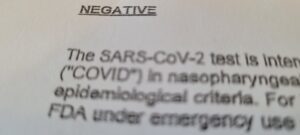

Although I had no reason to think I had COVID and was just testing for travel, I was relieved to get my negative result. Onward to figuring out the German government site for registering the info and the next part in this adventure travel series.

Although I had no reason to think I had COVID and was just testing for travel, I was relieved to get my negative result. Onward to figuring out the German government site for registering the info and the next part in this adventure travel series.

Passport + vax card + negative test result – the new travel kit for the international traveler.

April 18, 2020

A Walk Through Childhood

My first home-1960s

What’s a globe-trotting, ancestral-town-seeking, genealogist to do when under COVID-19 lockdown? Find places of family significance closer to home to explore, of course.

I’ve been walking in my neighborhood (permissible under lockdown guidelines) but all the closed coffee shops and stores mock me, making me think of the DBC (Days Before COVID). A couple of days ago, I decided I needed a different neighborhood for my daily walk. So I took a short drive to the street that I grew up on.

It was a walk in the sunshine to get some exercise and shake off the trapped feeling of lockdown, but it was also a walk through my childhood.

My first home-2020

I parked near the house where we lived when my parents first brought me home from the hospital, then walked down the street to the larger house where we moved when I was 3. Twenty-three years of my life, all on one block.

Both houses have a lot more elaborate landscaping than when we lived there, but maybe it was just the 60s thing to do to have wide open lawns boundaried by flower beds and not much else. I peered through the hedge to see the kitchen window where, as a toddler, I loved to watch birds, and looked up at my long-time bedroom window.

Even with paint and renovation changes over the years, I could easily pick out house after house where schoolmates had lived, with fun memories of trick or treating, playing kick the can, riding our bikes, going to Girl Scouts. Of course, there are less fun memories, like the house where two girls that I thought were friends ran into the garage and quickly shut the door to hide so they wouldn’t have to invite me to play with them. (Oh those nerdy years when it became obvious that I was more the boring straight-A kid than cool kid.)

House I grew up in-1960s

I retraced the steps of young Carolyn to my old schools—first my grade school and then my junior high school. How many times had I walked/run/biked those streets? Yet despite everything feeling familiar, I also felt oddly detached.

This suburban neighborhood of large 50s-era houses with well-manicured yards and sweeping views gives off such a different vibe than where I live today, which alternates small craftsman bungalows with tall new townhouses (the perfect low-maintenance option for those of us who like to drop everything to travel or hike). My neighborhood is filled with quirky coffee shops, people with every style and color of hair (with neon almost as common as blonde or brown), and has a proud tradition of an annual neighborhood festival that features naked bikers as well as a troll statue that we are all very fond of.

House I grew up in-2020

In my current neighborhood, my practical walking outfit of sandals that have traveled the world with me along with t-shirt and pulled-back hair designed for hiking ease make me blend right in. In my childhood neighborhood, my choice of attire was quite a contrast to the women joggers with perky pony tails and families with 2.3 children taking the dog for a walk.

Walking my old neighborhood reminds me of my Norman-Rockwell, Sally-Dick-and-Jane childhood, which was a wonderful, safe place to launch me into life. I recognize how lucky I am to have had that security, since many children don’t.

I have such fond memories of grade school. But from this angle, it looks a little like a prison, doesn’t it?

But walking the old ‘hood became a nudge to reflect on all the places I’ve been since then, and all the new and interesting friends I’ve made as a traveler and hiker and explorer of family history. I suppose this is true of most of us, but my life experiences have made me a much more interesting person than the Carolyn who walked to school clutching her Lost in Space lunchbox. (Hmm, since Barbie lunchboxes were the norm for little girls in the 60s, perhaps my lunchbox choice was a foreshadowing of my explorer gene wanting to burst out.)

Touching base with my childhood roots was a reminder of my travels through life, and how each step of the journey has taken me far from that old neighborhood into a much richer set of friends and experiences—a valuable gift from a walk that was mostly planned as an escape from COVID Confinement.

April 1, 2020

Pandemic Perspective

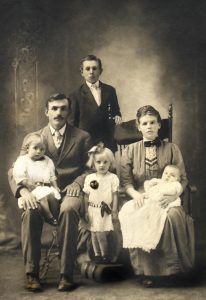

Rudolf and Christine (Beck) Schott with family

I’m an explorer. Whether it’s traveling to explore ancestral towns, traveling to explore new places with friends and family, checking out new hiking trails in the mountains, or simply trying a new restaurant in my neighborhood, my life is all about being out and about.

So being in lockdown for weeks, with no known end date (at least, no reliable end date), strikes to my very core.

One of the projects I’ve been working on during lockdown is indexing obituaries of Germans from Bessarabia. Thinking about their lives as I’ve indexed names/dates/places is a bit of a kick in the pants to realize just how fortunate I am.

Bessarabian Germans had made a pretty good life for themselves in their villages near the Black Sea. Sure there had been a little bit of upheaval in 1918 after WWI when they suddenly switched from being Russian citizens to Romanian citizens, but all in all, they had prosperous farms and peaceful lives.

Our lives today have been unexpectedly turned upside down by a pandemic, just as theirs were turned upside down in June 1940 when they learned the Soviets were re-taking the area. The German villagers would have to leave their family homes of more than a century and would be resettled by the Nazis to farms in Poland.

One of these villagers was my grandfather’s younger brother, Rudolf Schott. At the age of 54, just when he probably thought he’d made a pretty comfortable life farming and could slide into years of watching his children and grandchildren grow, he and his wife had to pack up their six children and everything they owned in a wagon and leave.

They stagnated for two years in a resettlement camp near Chemnitz, then were assigned a farm in eastern Poland to build new lives there. They farmed by day, and by night they fought off Polish partisans (who were justly angry at the Nazi invasion and seizure of their land).

In January 1945, Rudolf and family had to flee to escape the approaching Russian army. Rudolf’s daughter Ida told me that to this day, when she hears a plane overhead she stops and listens to see if it was a normal plane or one that would drop a bomb. “I got to know the difference,” she said.

After the war, Rudolf (now about 60) and his wife Christine started over again, this time in Eastern Germany. Their older sons had probably lost years of their lives to service in the Wehrmacht. Their younger children had several years of schooling disrupted. For five or six years, Rudolf and his family’s lives became unrecognizable from what they had been in June 1940. So much so, that when my grandfather offered to sponsor them to come to the U.S., they turned him down. After a life in Bessarabia, limbo in the resettlement camp, starting over in Poland, and starting over in Eastern Germany, they just didn’t have the energy for one more do-over in their lives. Their future had changed in ways they could never have guessed.

So when I feel depressed about the inconvenience of staying home, or am concerned about what the future will bring financially, or am sad about the restrictions on travel, or feel desperate to have things be normal so I can run an errand and buy a Starbucks coffee without reaching for the disinfectant—well, then I just think about Grand-Uncle Rudolf, whose life was changed much more dramatically than it is likely I will experience.

—————

This is typically what happened to the young men. But the documents to verify that are not readily available at the (COVID-19 pandemic) moment.

May 25, 2019

Desperation Leads to Travel Souvenirs

Fleece, scarf, bathing suit = memories of German snow, Budapest concerts, and Abu Dhabi beaches

Most people buy souvenirs when they travel. I seem to buy clothes.

Not because I’m a fashionista (believe me, jeans and sweatshirt are my favorite outfit). Not because I intentionally set out to remember my travels through apparel. But something always seems to come up to make the clothes in my suitcase inadequate.

There was the time I went to Germany for two months to study the language and travel. Who expected torrential rain in July and August? New German rain jacket to the rescue.

In my zeal for packing light on a two-month trip to Europe, my travel wardrobe included minimal color options (as I wanted every top, sweater, pants, skirt to match). It was only when I “dressed up” to go to a concert in Budapest one night that I realized that all the black made me look like something from a horror movie. The green scarf I bought at Budapest’s Central Market Hall has become a constant companion. It adds a splash of color and dresses up any outfit, but is lightweight and surprisingly warm when wrapped around my neck on a cold day.

In Abu Dhabi, an appropriate way to experience one of the richest cities in the world was at one of the most expensive hotels in the world. Of course, my budget does not run to spending $800 a night on a suite (and I was staying with a friend anyway). But it could spring for a day pass to the beach club (also expensive, but financially feasible for the experience, especially since it included a camel ride). My lack of bathing suit was easily solved at a local mall (no shortage of those—Google lists more than 30 mall options in Abu Dhabi). The suit looks a little like a tablecloth for a church picnic, but it was cheap (had to save money somewhere) and it fit.

My latest clothing adventure was in Germany earlier this month. It had been in the 70s and 80s the week before I left home. Even though I knew it was cooling off a little for the weeks I would be there, I didn’t pack for temps in the 30s and 40s (and snow!). After all, it was May. Fortunately, a frantic text to a local cousin “Ute, quick! What’s the equivalent to REI in Germany?” set me up with a nearby sports store and fleece jacket. (I suppose I could have googled, but Cousin Ute is a more reliable source.)

Although purchased out of desperation, many of these items have become favorites. I have fond memories of Baltic adventures when I wear the puffy coat I bought in Lithuania (to replace a jacket lost at a Polish airport) when I visit North Dakota in winter. The fleece-lined jacket from the San Juan Islands (honestly, it was 95 degrees the day before . . . how could it drop to the 50s for whale watching?) is my favorite “wander my Seattle neighborhood in winter” jacket.

I guess a travel souvenir is whatever brings back memories of your travels. And in my case, memories of wardrobe desperation.

April 14, 2019

House Sitter from Hell

The worst house sitter I ever had was the one I had to pay.

The worst house sitter I ever had was the one I had to pay.

For years, my long trips seemed to coincide with a friend or friend-of-friend’s need to escape difficult roommates, find somewhere to live during a breakup, or stay when home for the summer while working abroad. All of these were mutually beneficial situations—my house was lived in and cared for during my absence, and a friend had somewhere to stay rent free. Win win.

Then came a month-long trip with no potential house sitters in sight. It was probably positive that I didn’t have any friends in crisis, but it left me with a dilemma. Fortunately (or so I thought), a friend told me about an experienced house sitter named Melanie.* Paying for a house sitter was a new concept for me, but a reasonably priced acquaintance of a friend seemed like the ideal solution.

My first inkling of trouble was the voice mail message I received in Germany.

“Carolyn, can you call me? I’ve locked myself out of your house.”

Now admittedly, there was a quirk with my door, but I’d explained that to her in detail—both verbally (with lots of emphasis on not closing the door without a key in hand or confirming the door was unlocked) and in my written instructions. And I wasn’t sure what she expected I could do to help when I was 5,000 miles away. Hop on a plane?

By the time I got the message, she’d been standing outside of my house, in her pajamas, for an hour. I suggested she call one of my friends, whose numbers I’d given her, who had keys to my house. But no, the phone numbers were in the locked house. And in those days before cellphones roamed internationally, I’d left my U.S. cellphone (where all my contacts were) at home. Fortunately, I had one of the friends’ numbers memorized and gave that to her. I pointed her in the direction of my nicest neighbors if she was getting cold or her cellphone battery ran out. I suggested she could pay a locksmith to let her back in.

I felt sort of bad hanging up at that point, but had nothing else to offer her. “Good luck. Let me know how it turns out.” And I went out to dinner. I later learned that she’d called her mother to rescue her while trying to get hold of my friend to get back in the house . . . which she eventually did.

My next inkling of trouble was after I got home. She’d already moved out by then, we’d chatted by phone and laughed (I thought) about the lock-out situation. I’d sent her a check.

But I should have waited until I used the door myself. The next day, I put my key in the lock. Or tried to. The key wouldn’t go in, so the door’s deadbolt wouldn’t unlock and I had to let myself in through the back door.

I’d been to the grocery store to restock after the trip and started putting things away before I called her about the door situation. Except nothing was familiar in my cupboards. Boxes that had been in cupboards on the east side of the kitchen were on the west side of the kitchen. Cans that had been in cupboards on the west side of the kitchen were now in the pantry. What cyclone had hit my kitchen?

I called Melanie, and asked if she’d experienced any problems with the deadbolt.

“When I was locked out, I tried to pick the lock with a stick. It broke off in there. So I just didn’t use the deadbolt the rest of my visit.”

And she wasn’t going to tell me? Did she think I wouldn’t notice? And who breaks something on a stranger’s house and doesn’t tell them? I resisted the urge to ask her if she had a background in breaking and entering that would have made the picking-a-lock-with-a-stick plan seem like a practical idea.

And the kitchen?

“I was getting something off the shelf and one of the boxes started sliding out. I moved it and I guess I got carried away.”

EVERY SINGLE item in two cupboards had been moved. Carried away seemed like an understatement.

The odd thing was, she didn’t even seem embarrassed or apologetic for breaking something, hiding it, and not offering to have it fixed . . . or for rummaging through cupboards she had no business in. I think my house might have been safer left on its own than under the influence of Cyclone Melanie.

I suppose it could have been worse. The plants were watered and no family heirlooms disappeared. But it’s made me wary of house sitters. At least, the ones who want to be paid. Now, whenever I plan a trip, I have a battle with myself. I don’t really hope a friend will have a housing crisis, but . . .

*Name changed to protect the guilty.

October 31, 2018

A Great Cloud of Witnesses

A snowman stands guard over my aunt’s grave in Kulm, North Dakota. Snowman courtesy of great-grandsons.

Genealogists and cemeteries go together like peanut butter and jelly. So exploring cemeteries is nothing new to me.

I’ve tip-toed through broken stones and overgrown lilac bushes in the cemeteries of German villages in Ukraine, hoping to find a shard from an ancestor’s grave.

I’ve bumped over gravel roads to find the country cemetery out on the North Dakota prairie where my great-great-grandmother is buried.

I’ve walked in reverence through perfectly manicured cemeteries in Germany, knowing I wouldn’t find a 200-year-old ancestor (because they recycle graves in Germany), but searching for modern-day distant cousins.

I’ve visited my parents’ graves, two small graves among thousands in a city cemetery in Seattle.

I’ve even poked around cemeteries in Lviv and Havana that have no family connections, just because they’re picturesque.

So I’m no stranger to cemeteries, but I never expected to feel the sense of community I felt as I entered the Congregational Church cemetery in Kulm, North Dakota.

“There are my Schott grandparents,” I pointed out to the step-cousins in the car with me. “Oh, and that Billigmeier is related to me, but distantly. Oh look, there are Bobby and Alice. I remember such a great day my mom and I had with them once when I was visiting.” I thought not of their graves, but of each of these people’s lives. And felt a bit sad as we stood on one uncle’s grave, with the empty spot next to him that had been reserved for, but never used by, his wife. She was buried in Fargo, next to her not-liked-by-the-family second husband.

As the wind howled like only an October Dakota prairie wind can howl, the pastor at my Aunt Idella’s burial service (who also happens to be Idella’s grandson), talked about the great cloud of witnesses surrounding her as we laid her to rest.

It could have been creepy, but it was strangely cozy. I was surrounded by my peeps, relatives everywhere I looked.

It could have been cold and dismal, but the wind was strangely energizing as it enfolded our small group. We were surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses. Our community. Our family.

May 20, 2018

Torn Between Two Homes

Guest blogger Alex Hamel is a graduate of the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota. For several years, she has taught English and lived in the country of her birth—South Korea.

Guest blogger Alex Hamel is a graduate of the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota. For several years, she has taught English and lived in the country of her birth—South Korea.

I have two homes and every day I feel torn between the two.

One is where I grew up in Minnesota, pictured myself getting married, having kids, starting my career. The other is where I was born in South Korea, and didn’t have a true connection with until I graduated from college.

One is where I have to guard myself, “not be so sensitive,” and live with being different. Although I can easily communicate my feelings, oftentimes I don’t. The other is freeing and comforting, not easily explained how weight is just lifted off my shoulders, yet I struggle with simple tasks because of my language barrier.

One is where others think I should be and where the logical career woman would foster. The other is where my heart yearns for and where I feel emotionally whole.

I could easily live in both homes, but I choose to be whole. I choose to fill my heart. I choose Korea.

April 7, 2018

The Elusive Wesley

Photo was circa 1914, based on the ages of my aunt and uncles in the photo. Wesley is standing in the back.

I know he existed. But where did he go?

One of our family mysteries is Wesley, an orphan boy that lived with my Schott grandparents sometime in the early 1900s. The family lore is that my Grandpa Peter “went to the train station” to pick him up, that he was a bit wild, and that he died when he fell off a horse, hitting his head on a rock because his feet were stuck in the stirrups. The story about him being “wild” is either connected to the fall, or the story that he used to load my young aunt and uncles into a wagon and then have a horse pull them around the farmyard.

What I find so mysterious is that Wesley is not listed in the North Dakota state death index nor in the records of the Kulm Congregational Church, the Schott family’s church. Why wouldn’t his death be recorded in one of these places?

What I know

I have a photo, so I know he lived with my grandparents’ family in 1914. In that photo, I’m guessing he’s between 10 and 13 years old (maybe a bit older if he’s not standing on something to make him taller).

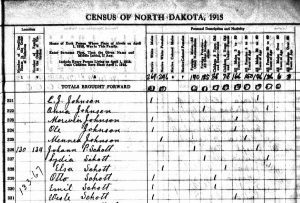

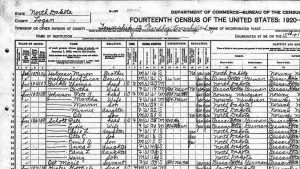

He shows up on the 1915 North Dakota state census as “Wesle Schott.” That indicates to me that, whether they adopted him officially or not, they considered him a member of the family. But he’s gone by the next U.S. census, recorded in January 1920.

1915 North Dakota census

My wild speculations

I know that I need to focus my search based on what I know, at least until I prove that it’s wrong. But I can’t help speculate.

What if he didn’t really die (since I can’t find his death record), but instead ran off and became a WWI doughboy?

Could he have come from the Orphan Train (based on the reference to my grandfather picking him up at the train station)? But when I contacted the Orphan Train Society, they could find nothing on him. Of course, I didn’t have much information to work with, not even his real last name.

Could he have been Catholic? Many of the Orphan Train riders were Irish Catholics from New York. And in the early 20th century, it might not have been considered proper to record the death of a Catholic boy in the records of a Protestant church.

1920 U.S. census

Where I’m looking

But, going back to what I’ve been told—that he died while living with my grandparents—I devised a plan to search the 1915 through 1920 issues of the local paper, the Kulm Messenger, while I was in Kulm for Easter this year. Even if his death didn’t get recorded officially, I’m sure such a tragic accident would make it into the paper.

Unfortunately, timing issues and snowy roads cut into my research time and I was only able to search one out of the five years I needed to look at. (Bad microfilm didn’t help my cause … being hard to read made it difficult to scan quickly and slowed me down.)

No luck so far, and the mystery continues to be unsolved. I self-medicated my disappointment with a Caribou dark chocolate mocha … and started making plans for getting myself back to North Dakota to keep searching.