Carolyn Schott's Blog, page 5

July 6, 2015

The Things You Don’t Ask

I was always intrigued by the Salmon La Sac exit off Interstate 90. Partly because it’s such a quirky name. But partly because, every time we drove by it on a family road trip, my mom used to say with nostalgia, “Oh, we used to go camping there.”

I was always intrigued by the Salmon La Sac exit off Interstate 90. Partly because it’s such a quirky name. But partly because, every time we drove by it on a family road trip, my mom used to say with nostalgia, “Oh, we used to go camping there.”

Why did this comment never intrigue me enough to ask questions? Why did I never say in disbelief, “Camping? You went camping? Seriously?”

I don’t think we ever went camping even once when I was a child. I vaguely remember visiting some cousins once when they were camping … and then I think we went to a motel. My mom never struck me as a “roughing it” sort of person. Neither of my parents did. So the fact that they camped at all should have sparked some interest.

Why did I never ask, “Why? What was so special about Salmon La Sac? Did you go there often?”

Last weekend, for the first time in my 54 years, I went to Salmon La Sac. It is a beautiful area, but no more beautiful than many other parts of the Cascade Mountains. Did my parents go there often, so my mom’s nostalgia came from familiarity? Did they go there with close friends and that made it meaningful? Did something special happen there? Was I conceived there? What?

Why did I never ask, “Who did you go camping with?”

My mom died seven years ago. My dad, nearly 40 years ago. I don’t even know who I could ask now about why this was a special memory for my mom.

My hike at Salmon La Sac last weekend made me think of all the questions I should have asked my parents, but never did. Or those I asked too late in life when my mother would brush off every question (especially the ones about how she and my dad dated, broke up, and then ended up married) with, “That was so long ago. I don’t remember.”

What are all the things about my parents’ lives that I should have found out more about, and now it’s too late?

Maybe the Salmon La Sac story wasn’t all that important. But maybe it would have revealed something about their life pre-Carolyn that would have helped me understand them better.

What else have I missed? Why didn’t I ask more questions sooner?

Don’t wait to ask the questions. Don’t regret the things you never asked.

June 23, 2015

Walking Like a Local

Street market in Dakar

On my first day in Dakar, my blonde, wide-eyed newness made me a magnet for every street vendor trying to sell something. They followed me persistently; I couldn’t shake them.

On my last day in Dakar 10 days later, my walk down the street was a much different experience. I’d learned the secret.

Engaging with street vendors in the hope that a firm and persistent, “No thanks,” would persuade them that I wasn’t interested was the mistake I made the first day.

Simply ignoring them didn’t work either. The very act of actively ignoring them is a sort of engagement. They feel you ignoring them, and it encourages them to follow, trying to turn your act of ignoring to an act of engaging.

Street vendors in Dakar

By the tenth day, I found that the secret to a peaceful walk through Dakar was to surround myself with a bubble of obliviousness. They’re simply not there. I didn’t hear them. I didn’t see them. I didn’t acknowledge them even by ignoring them. They were irrelevant. I was caught up in my own thoughts, my own destination.

It worked like a charm (even better than barking at them in German, which I also had a small bit of success with). After their “Hello, Madame,” was met with obliviousness, they simply melted away and looked for someone else.

It’s a shame really. When I visit a new place, I like to be engaged. I like to observe everything and everyone around me, trying to absorb the culture. But when engagement means harassment, obliviousness is a welcome relief. I’m so glad the annoying merchants weren’t my only exposure to the people of Senegal and that I got to meet colleagues at the meetings I was attending to have an appreciation for the warmth and friendliness of the Senegalese people.

My bubble of obliviousness also allowed me to pay more attention to walking, avoiding the sidewalk obstacles—trash, cement dissolving into sand, someone sprawled out sleeping.

Although I’ll never look like a local in Dakar, walking down the street without being harassed made me feel like a local—even for a day.

June 14, 2015

Every Day’s a Vacation

Funny, I don’t even notice the power lines when I look at the view from my deck.

It’s no secret that I love to travel. I love exploring new places, absorbing the culture through its foods and music, hanging out in sidewalk cafes and watching the people go by.

But I also love that I live in a place that makes me feel like I’m on vacation every day. This weekend, I threw my to-do list and errands to the wind, and lounged on my deck watching the sailboats on Lake Union. When I felt the need for more people around me, I walked a couple blocks to my local Starbucks to sip a frappucino and indulge in reading a book.

It was just a short hop (mentally) to France as I sampled pastries and sipped coffee with friends in a tiny urban bakery courtyard, where we poked our heads into the doorway of a children’s cooking class in progress next door. Then I journeyed on to Greece via a shrimp/feta/ouzo/garlic/tomato dish I made with a recipe from my favorite Greek chef.

Discovering a new brunch place is always a useful way to spend a Sunday.

An impromptu Sunday trip to the local farmers market in search of rhubarb (me) and radishes (my friend), ended with a bag full of goodies and exploring the outdoor deck of a new brunch place.

All vacations (and weekends) have to end. And tomorrow I’ll be back to commuting and emails and juggling work projects. But for now, I think I’ll wrap up my weekend nibbling raspberries and Gouda in my own little oasis in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood.

June 7, 2015

On the Shores of Africa: Gorée Island

The Door of No Return, House of Slave, Gorée Island

Most of what I learned in school about slavery were dry facts about the Emancipation Proclamation or Underground Railroad. As I grew older, books and shows like “Gone With the Wind” and “Roots” put a more human (though probably misleading, at least in the case of GWTW) face on it. But the focus of all of these sources is the experience of slaves in America. So I’ve never known much about the slave trade from the African side.

I’ve never really thought about (except in an abstract sort of way) the homes and culture these people were torn away from and forced to leave behind. I’ve never really thought about how they were captured—maybe by a warring tribe or a local mercenary doing business with the white slave traders. I’ve never thought about how they waited in darkness and chains in their own land to be auctioned off to a slave trader—only to have to go through the same humiliation again when they reached the shores of America.

Gorée Island, Senegal

Gorée Island beach

But now I’ve been to Africa. Funny what a difference that makes. I’ve met the descendants of the lucky ones who weren’t captured. I’ve stood in the doorway that so many Africans walked through, their last time to stand on their own continent before walking out the door onto the gangplank to the ship where they were piled onto shelves and shipped across the ocean.

A trip to Gorée Island, a slave trading center in the 1700s just off the coast of West Africa, is a surreal experience. The ferry from Dakar docks at a charming village with brightly colored houses and restaurants on the beach serving freshly caught fish. The vibrant bougainvillea spills over the walls as we dodge the persistent vendors selling jewelry and fabrics and ornately carved wooden ornaments. Boys play soccer in the center of the village, just an ordinary Sunday afternoon. Until I realize the structure in the middle of the town square where the boys were playing was not a charming viewpoint, but instead the auction block where slaves were sold.

Gorée Island street

It’s surreal to get your mind around the fact that this charming, colorful beach island was the center of the dark and penetrating evil that happens when one group of humans profits off the suffering of other human beings.

It’s surreal to watch a couple of 20-something women pose for tourist photos on the staircase at the House of Slaves with a cute, sexy, over-the-shoulder smile.

It’s surreal to know that, 200 years ago, young women just like them were forced up that staircase to be raped by white slavers. It’s surreal to know that 200 years ago, being raped and impregnated was these young women’s ticket to remaining in freedom on Gorée, rather than being thrown on a ship to America.

It’s surreal to think about slave traders living and partying on the upper floor of the House of Slaves and apparently disregarding the groans and despair of the African people, imprisoned and chained in dark cells just below them.

And despite my ever-present focus on family heritage, it never occurred to me that the majority of African Americans probably have their roots in West Africa (vs. any other part of Africa). It never occurred to me that certain groups of Africans were harder hit by this cancerous disregard for human life and dignity simply because of their misfortune in living closer to a continent across the sea with an appetite for enslaving other human beings.

And despite my ever-present focus on family heritage, it never occurred to me that the majority of African Americans probably have their roots in West Africa (vs. any other part of Africa). It never occurred to me that certain groups of Africans were harder hit by this cancerous disregard for human life and dignity simply because of their misfortune in living closer to a continent across the sea with an appetite for enslaving other human beings.

There’s a lot about slavery I never thought about until I stood on the shores of Africa.

June 4, 2015

Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia – History of a German Village (Part 6)

This is the final of 6 blog posts on my grandfather’s home village of Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia (now Ukraine).

The Polish countryside

Resettlement to Poland

The areas of West Prussia and Posen/Warthegau in northern and western Poland had been directly annexed to Germany. By the first part of 1941, the SS had expelled close to 400,000 Poles from their property in these areas, intending to settle ethnic Germans, including the Bessarabian refugees, there. With these lands available, most of the former Bessarabians were resettled and left the refugee camps fairly quickly. The uprooted Poles, many of them dying en route, were sent to the “General Government” or central and southern part of Poland, which was now occupied and administered by the Nazis.

Pawns in the Nazi settlement plans

The villagers of Hoffnungstal were originally intended to be resettled in the province of Danzig-West Prussia. However, the process was delayed and the people of Hoffnungstal ended up remaining in the refugee camps for about two years. Still in the refugee camp in 1942, the villagers of Hoffnungstal were the only of the Bessarabian mother colonies unable to celebrate the centennial of the founding of the village in their home.

The people of Hoffnungstal were told that the delay was due to the death of their mayor, Immanuel Aipperspach. However, coincidentally, during this same time the Nazis were revising their settlement policies. Anticipating Nazi victory, they were planning for the “Re-organization of Europe,” which included settling the General Government area with ethnic Germans. In late 1942 and 1943, more Poles were expelled from the Zamosc-Lublin area, many of them being sent to concentration camps or conscripted for labor.

The Hoffnungstalers were then given the choice of remaining in refugee camps for the rest of the war or being settled farther east than the other Bessarabians, in the General Government area nearer the war front. Desperately wanting to leave the refugee camp, not fully aware they had become pawns of the Nazi settlement policies, the people of Hoffnungstal, along with another Bessarabian village, agreed to be settled in the district of Lublin/Zamosc in December 1942—a small group of 4,000 ethnic Germans in the heart of Poland, surrounded by Poles with good reason to hate and fear anything German.

What mixed emotions the former Bessarabian Germans must have had as they settled into their new homes and became more fully aware of their situation. Relief that they were out of the refugee camps and able to work again as farmers and craftsmen. Justified in taking over these Polish farms, as they had left behind their own long-established and prosperous farms with the promise that they would be compensated for what they’d left behind.

And yet what dismay they must have felt knowing that the Poles had been forced from their homes and were now working for the German farmers as day laborers in what once were their own fields.

Source: Bundesarchiv Bild 183-1990-0323-501, Flüchtlingsfamilie in Oberschlesien./Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikimedia Commons

“Front-line” farmers

The Poles, terrified by the expulsions by the Nazis and probably fearing that they would soon suffer the same fate as the Jews, formed partisan resistance units and struck out at anything German—making no distinction between the SS and the Bessarabian Germans whose only motivation was to be able to farm and work their own land again.

For more than a year of living in this area, the German villagers were constantly terrorized by Polish partisans setting their homes on fire by night and other violent acts. All men ages 18 to 65 kept a nightly watch and rarely got a full night’s sleep.

The attacks got so bad that the Germans asked the district SS commander to send the women and children to safety in Germany and the men would enlist in the army where they could “at least see the enemy in front of them.” They never knew which direction a partisan attack would come from. The SS commander told them to stop their complaining, sling a gun onto their backs and get behind their plows. After all, they were “front-line farmers.” An especially tragic set of attacks in June 1943 resulted in a large number of deaths in just one or two nights.

In 1944, the Russian army was advancing and the partisan attacks became even more brutal. Finally in March 1944, the women, children, and elderly were sent west for safety in refugee camps near Lodz. The men were required to remain in their Zamosc homes to fight and start that year’s crop. Finally in July, the battle front was advancing too quickly and the men headed toward Lodz with whatever possessions they could put in wagons. Many of the men of Hoffnungstal either died or were imprisoned by the Russians during the flight to Lodz. Those that made it to Lodz were either drafted into the German army or into labor battalions to build entrenchments.

Die Flucht (The Flight)

The last chaotic flight to escape the advancing Russian army occurred in January and February 1945. Leaving most of their possessions behind, they fled with whatever was available—wagon, some trucks, or on foot—toward Germany. Fifteen of the people from Hoffnungstal died as they fled ahead of the advancing war front. Another 23 people either disappeared while fleeing or may have been overrun and captured by the Russian army. (The specific fates of all of these people are not known, but some are known to have been deported to Siberia.)

Memorial in the Hoffnungstal cemetery

A scattered community

Although the majority of the 2,088 Hoffnungstalers who were resettled in 1940 survived the war, after WWII they were scattered throughout Germany and were no longer a unified community. With the post-war division of Germany into East and West, many families were also separated by these political barriers.

Visits to Bessarabia, as part of the Soviet Union, were officially impossible until 1993 when Ukraine took over this territory (although some clandestine visits may have occurred). In particular, the site of Hoffnungstal was used as a restricted military area by the Russians and was therefore off-limits. Sometime after the Germans left, the Russians flattened the village (possibly using the deserted village for target practice during their training exercises) and the cemetery gravestones, and set up a military base and power station nearby. (It’s also possible that the village buildings were already damaged from an earthquake that occurred soon after the villagers first left in 1940.) The only structure that remained standing as of 2001 is the schoolhouse, which was taken away from its original location to be used as part of the power station.

In 1994, former residents of Hoffnungstal now living in Germany erected a memorial stone at the site of the former Hoffnungstal cemetery. In 1996, they returned to add a copper plaque with an inscription to the top of the memorial stone and held a service dedicated to the memory of their former home. The copper plaque later disappeared, and a more substantial stone memorial was built, commemorating the German settlers of Hoffnungstal, now a ghost town called Nadezhdivka, Ukraine.

June 2, 2015

Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia – History of a German Village (Part 5)

This is part 5 of 6 blog posts on my grandfather’s home village of Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia (now Ukraine).

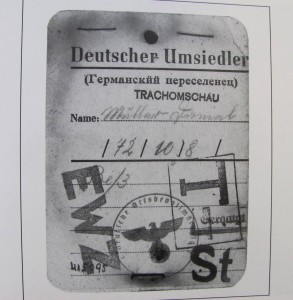

Identification card for those being resettled (Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

The beginning of the end … leaving Bessarabia

The year 1940 was a major turning point in the history and life of the Bessarabian villages, including Hoffnungstal. As part of the Versailles Treaty after WWI, Bessarabia had been annexed to Romania in 1918. In June 1940, Soviet troops demanded the Romanian evacuation of Bessarabia. As part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, the German colonists would be resettled to Germany as the Soviet Union claimed the land of Bessarabia.

Although the villagers could not know what would lie ahead for them, it was immediately clear that their position had changed. All schools were closed and hospitals were seized by the Soviet authorities. Traffic was restricted on the roads and all private travel by train was forbidden.

Taxes for 1940 had to be paid again in full, even if they had previously been partly (or even fully) paid. Overnight, the Romanian lei was declared to be invalid currency, meanting the taxes had to be paid in material goods (grain, etc.) An arbitrarily determined amount from the 1940 harvest had to be handed over to Soviet authorities. Often there was alleged contamination of the grain, and the villagers were forced to hand over additional amounts above and beyond what would pay their debt.

Soviet authorities nationalized many businesses including banks, companies with more than 20 workers, book and printing shops, electric facilities, and schnapps and wine distilleries. In addition, they took over all the schools, hospitals, drugstores, movie theaters, museums, and hotels throughout Bessarabia. The German villagers faced all of this with resignation, saving all they could of the possessions that they still had.

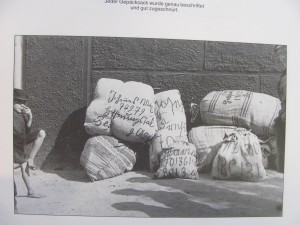

Packing up household goods for the journey to Germany (Source: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

The Umseidlung (Resettlement)

On September 15, 1940, the German Resettlement Commission arrived in Hoffnungstal to begin assessing the villages in the area for resettlement. The assessment continued until about the end of October. The Commission went door to door through the village, assessing the contents and property of each family. The villagers would only be allowed to take a small number of possessions with them—the rest they were to leave to the Russians and they were to be reimbursed when they had returned to Germany.

Women, children, and the elderly would travel by truck. The men would travel with the horses and wagons. Those traveling by truck could take only carry-on personal items. Those traveling by wagon could take one wagonload of possessions per family. Officially, each family was allowed to take some livestock, limited to two horses or oxen, one cow, one pig, five sheep or goats, and some poultry. In reality, however, the villagers were not allowed to take livestock with them due to “transportation” problems. The cherished Bessarabian horses were sold or later requisitioned for a German cavalry unit.

The villagers were allowed to take only 2,000 lei (probably about $3 U.S.) per person, plus the proceeds of any documented sales of personal property. No gold or silver in ingot or dust could be taken. Gold or silver in watch chains, wedding bands, etc. was limited to 500 grams per adult.

Weapons, binoculars, or any items of military origin were forbidden (except for one gun per hunter). Manufactured items or store-bought clothing were limited. Family photos could be taken along, but no other photos, documents, or printed items could be taken. No engine or electrical-powered devices could be taken, nor any seeds, seedlings, or grape vine cuttings.

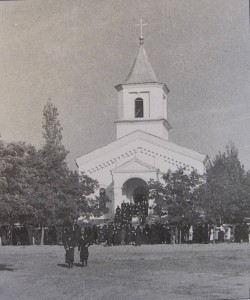

The farewell service in the Hoffnungstal cemetery (Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

On September 26, a farewell service was held in the Hoffnungstal cemetery, and on October 1, the families of Hoffnungstal began leaving their home of almost a century. First the women, children, and the elderly from Hoffnungstal’s east street left.

They went by truck to the Danube harbor at Reni, then by ship to Semlin near Belgrade. After spending two days in a refugee camp at Semlin, they went by train through Vienna to the Sachsen area of Germany to a refugee camp near Chemnitz.

The men from Hoffnungstal’s east street left on October 2 by horse and wagon. At the border between Bessarabia (now Russian-occupied) and Romania, all the wagons had to be unloaded for a customs spot check. All bags, pillows, etc. were opened and checked. Then everything had to be packed up again and loaded back on the wagons. They crossed the river on a shaky bridge, headed for the harbor at Galatz.

At Galatz, the luggage was unloaded and stored. (The Hoffnungstalers would not see these possessions again for two years.) Wagons and horses were handed over to the German military to be used as a cavalry unit in the Balkan campaign. The men, along with their carry-on personal possessions, took a ship up the Danube to rejoin their families at the camp near Semlin, then later to the refugee camp near Chemnitz.

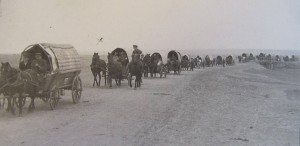

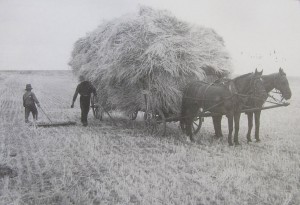

Wagons leaving Hoffnungstal (Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

The Hoffnungstalers living on the west street followed the same journey about a week later, with the women and children leaving on October 9, and the men leaving on October 15. They also ended up in the refugee camps near Chemnitz.

About 50 people from Hoffnungstal had been too sick to travel by regular truck—these people were transported by ambulance or special trucks to Semlin along with sick people from other Bessarabian villages. In many cases, their families, waiting for them in Chemnitz, never saw them again.

Living as refugees in Germany

Mealtime at a refugee camp in Germany (Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

The camps at Chemnitz were gymnasiums, factory halls, restaurants converted for the purpose of housing refugees where everyone slept together in big rooms with many cots. Many of the young men were drafted into the German army, the Wehrmacht. Other men were assigned to work in the factories—difficult physically as they performed hard labor on meager rations, and difficult emotionally for those used to being outdoors working their own fields or working as independent craftsmen.

Prior to resettlement, each person had to pass the “citizen harmonization” process. This testing consisted first of a physical examination, and then a race-political examination given by the Nazi Immigration Office and the National Security Service. This involved proving their German ethnicity so they could be declared “racially useful and politically dependable.”

(To be continued)

May 31, 2015

Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia – History of a German Village (Part 4)

This is part 4 of 6 blog posts on my grandfather’s home village of Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia (now Ukraine).

Celebrations

Memories of life in Hoffnungstal include much hard agricultural work. But there are also many stories of dances in the fall on the empty threshing areas with the musicians playing “zippy” dance music, the young men and women flirting, and the children playing at the edge of the dance floor. The upper and lower villages each had their own Kameradschaft or youth group that competed against each other. Each youth group had their own three-man band that would play for dances. And it was frowned on for a young woman from one youth group to marry a man from another!

(Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

Favorite celebrations included the Mayfest and Easter. For the Mayfest, two huge trees or poles would be set up in front of the church and decked out with glittery tinsel. For Easter, the youth would play the traditional “Eierlesen” or Easter Egg game.

“It was the custom that one went to the Easter egg hunt at the festival square on the second day of Easter. There, under a flag, were four rows of fifty eggs laid out. Every ten eggs, there was a hard-cooked, colored Easter egg. The rows were aligned with the four compass points—orth, south, east, west. The state flag would have been raised next to the Bessarabian flag.

“The procession was led by a band, four young men, and eight girls in gaily colored traditional costumes and carrying egg baskets. The procession was accompanied by the villagers.

“Each egg-gathering group consisted of two girls and a young man. The young man gathers the eggs and put them in one of the girls’ apron. The other girls had to put the eggs in their baskets. At each colored egg, the gathering would be interrupted and the band would play a dance. The goal was to gather all the eggs as quickly as possible and throw the last egg over the flag. The group that first managed to do this was the winner. Afterward, everyone went to the community center where late into the evening one celebrated, sang, and danced.” (Bessarabian Newsletter 4-1. Written by Friedrich Ernst; contributed by Armin Flaig; translated by Carolyn Schott)

Sickness and health

Compared to other colonies, Hoffnungstal had relatively few epidemics. Cholera claimed a number of lives in 1855. Also diphtheria, typhus, smallpox, and flu occasionally swept through the colony. Still, even without epidemics, the overall health situation in Bessarabia in the 1800s was bad. The dusty conditions in the field and roads caused a number of respiratory and lung diseases. The lack of sanitary conditions and prenatal care caused many women to die in childbirth.

Medical care was primitive. Most medical care was done in the home and was based primarily on prayer and home remedies. Although settlers started arriving in Bessarabia around 1812, the first doctor did not arrive until 1830. Up until the 1900s, the few available doctors were located only in the largest towns. In 1860, the nearest doctor for Hoffnungstalers would have been in Tarutino, approximately 16 miles away.

Long before the Internet…

Typical of frontier communities, communication and transportation services were also fairly primitive. With the opening of the Bender-Reni rail line in 1878, the mail began to be delivered daily to Leipzig. Someone would pick up mail in Leipzig and deliver it to the Tarutino post office. Surrounding villages had to pick up their mail from there.

Prior to 1878, mail arrived only weekly and had to be picked up from as far away as Sarata (about 45 miles) or Kauschani. Tarutino also received a telegraph office in 1877, and a telephone office a few years later.

(To be continued)

May 29, 2015

Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia – History of a German Village (Part 3)

This is part 3 of 6 blog posts on my grandfather’s home village of Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia (now Ukraine).

Education and the legendary teacher, Leopold Roßmann

School building in Hoffnungstal, built in 1910/1911 (not the original built in the 1800s). (Source: Hoffnungstal: BIlder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

Until 1858, there was no schoolhouse or teacher in Hoffnungstal. Children attended school in a farmhouse and the teachers were those farmers who were knowledgeable in reading and writing. Once a schoolhouse was built, the subjects expanded to also include arithmetic and the Lutheran catechism. The schoolbooks used were primarily the Bible, the hymn book, and a catechism. Instruction in religion was the primary purpose for education and Hoffnungstalers had little use for additional education.

“The people of Hoffnungstal gave all of their energy to … farming; they … valued culture very little. ‘When someone advised a farmer to send his son … to the ‘Werner School,” he would … ask very sharply ‘What shall my Robert become? A teacher? No, no that will never happen. He has to work and learn how to become a farmer.’” (Hoffnungstal Heimatbuch, p. 29-30). [Note: The Werner School was in the large town of Sarata that offered a range of subjects similar to high school and junior college, as well as a four-year program for training teachers.]

Leopold Roßmann was the main teacher in the Hoffnungstal school from 1874 until 1916. Until the late 1890s, he was the only teacher in the school despite having a large number of students. Even in 1905, there appear to have been only two teachers for 330 students.

Herr Roßmann, center, was the head teacher and sexton in Hoffnungstal for 42 years. Pictured here with his children. (Source: Hoffnungstual: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

In the 1890s, the Russian government passed a law requiring that school be taught in Russian, and in 1896, the Hoffnungstal school received a Russian teacher in addition to Herr Roßmann. However, it’s questionable whether the students learned very much since they probably spoke little or no Russian.

Herr Roßmann was a strict disciplinarian and well respected, almost to the point of fear, among the young and old of Hoffnungstal. He enjoyed music and sang with a strong voice in church services. As teacher, he also served as sexton. The sexton’s duties included reading the Sunday service (since Hoffnungstal shared a pastor from the parish church at Klöstitz), leading the choir, and arranging for baptisms and burials in the absence of the pastor.

Herr Roßmann was also extremely conservative and resistant to change. When a new hymn book was introduced in Bessarabia, it was easily accepted by most villages. However, Herr Roßmann led Hoffnungstal’s resistance to this new innovation and they continued with the traditional hymn book up until the Umsiedlung in 1940. (Which caused no end of troubles for the bookbinder in Sarata, as the old books were no longer published. Therefore, they were extremely difficult to find when the Hoffnungstal church required new books.)

For years, there were attempts to introduce schoolbooks other than the Bible into the school. (There was a new ABC book with colorful pictures of a rooster on the front cover and Little Red Riding Hood on the back cover that was popular in other places.) Although these were finally accepted during the tenure of Pastor Julius Peters, the village’s resistance to this scandalous innovation caused one pastor, Reverand Burkhardt, to actually leave the parish.

Leopold Roßmann’s conservative influence was felt long after his death. Whenever one of his successors tried to introduce something new, the typical response was: “This will not be done. Our old teacher Roßman would have never thought of this, and what he has done, and what he has said, was good and right and still is; we will not change anything; we will leave everything as it is.” (Hoffnungstal Heimatbuch, p. 32)

(Source: BIlder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

This continued until the late 1930s, when the last sexton-teacher of Hoffnungstal, Emil Wernick, was able to introduce some changes such as reviving the church choir, introducing a Ladies Aid Society, and starting a youth fellowship.

The influence of faith and church in Hoffnungstal

The village of Hoffnungstal was always staunchly Lutheran. Although several of the initial settlers were Catholic, they soon joined the Lutheran church. Up until 1918, there was a group of Separatists led by Michael and later Samuel Aipperspach, but that group eventually died out. At the time of the resettlement (1940), there were no Baptists, Adventists or followers of any other sect because “the people of Hoffnungstal had no love for religious fanatics.” (Hoffnungstal Heimatbuch, p. 27)—“fanatics” apparently being anyone who wasn’t Lutheran.

The schoolhouse also served as the prayer house or chapel until the Hoffnungstal church was dedicated on October 16, 1905. As part of the parish of Klöstitz, Hoffnungstal shared a pastor with other villages in the parish, so the local sexton-teacher was responsible for many of the daily pastoral duties in the village. Confirmations and weddings were presided over by the pastor at the church in Klöstitz, but if you wanted the pastor (rather than the sexton) to give a funeral service, you had to arrange for his transportation, picking him up and returning him home by wagon.

Reverend Julius Nikolaus Peters, about 1900 (Source: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

From 1879 to 1915, the Klöstitz parish was served by the Reverend Julius Peters. Reverend Peters was well-known by the German settlers in Bessarabia and was sometimes called the “Vicar of Bessarabia” since he often helped out by serving in other parishes when they did not have a pastor. He was of middle stature, with a friendly face and glasses. He was faithful right up until the end of his life as he died in the pulpit while holding an evening Lenten service.

“One can truthfully say that the people of Hoffnungstal were diligent church goers, and when worship services were held by the pastor, the church was usually filled to overflowing.” (Hoffnungstal Heimatbuch, p. 32)

(To be continued)

May 27, 2015

Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia – History of a German Village (Part 2)

This is part 2 of 6 blog posts on my grandfather’s home village of Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia (now Ukraine).

(Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

Prospering through agriculture

The land available for farming also expanded. The village was initially granted about 14,000 acres of land. In 1897, they purchased 675 acres, and in 1899, they purchased another 1,100 acres from Countess Tolstoi. They also leased a great deal of land from the Princess Gagarin.

The rolling hills surrounding Hoffnungstal made transport in and out of the village difficult, especially with heavily loaded wagons. But soil in the area was very rich and good for many crops with little need to fertilize it. The Hoffnungstal farmers practiced crop rotation, but due to the high quality of their soil, they didn’t need to let the ground lay fallow in alternating years. The land supported a number of different crops, including (as of 1940) wheat, barley, oats, corn, soybeans, potatoes, rye, castor beans, millet, sun flowers, rape, mustard, flax, beets, watermelons, and pumpkins.

“The people of Hoffnungstal were real farmers, plain, firm but open-hearted, just and hospitable … Land, land, was the password of the farmers of Hoffnungstal … To buy or rent more land was always the aspiration of Hoffnungstalers, since they had pride in farming. Their machines had to be modern and in good repair in order to carry on the work of growing grapes and grain …” (Hoffnungstal Heimatbuch, p. 29-30).

This hunger for land drove many Hoffnungstalers in the late 1800s and early 1990s to immigrate to the U.S., Canada, the Crimea, the Caucasus, West Siberia, and Brazil in search of new opportunities to develop their own land.

Commercial buyers bought wine directly from the farmers, however, the farmers had to haul their grain to the market themselves. Hoffnungstal farmers usually hauled their grain either to the train station at Beresina (about 11 miles) or to the county seat of Akkerman (56 miles). To get the best profit, some farmers took their produce to the large harbor city of Odessa (90 miles). However, this port was lost after WWI when Bessarabia (including Hoffnungstal) was annexed to Romania, while Odessa continued as part of Russia.

A farmers’ cooperative handled marketing the colonists’ produce. With Hoffnungstal’s agriculture as the main business and the marketing of the produce in German hands, the village was considered one of the most economically sound in Bessarabia.

(Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

Sheep and cows and horses, oh my!

Hoffnungstal farmers raised animals in addition to agricultural farming. Sheep were popular for their low expense and high income from wool, cheese, and the sale of lambs. Some milk cows and beef cattle were maintained, although profits from cow’s milk were small and the primary market for beef cattle was in Odessa.

However, the pride of the Bessarabian farmer was the Bessarabian horses. “In Bessarabia the horse is like family … love and care are given to the horse ahead of all other animals.” (Diary of the Village Assessor of Hoffnungstal, Hoffnungstal Newsletter 3-3.) Farmers often owned large numbers of horses as this was a measure of their reputation and village standing.

Careful attention was paid to maintaining a good breed, and the favorite color to breed for was black. The horses were based on the old Arabian pure-breds. “The last breeding stallion from the upper village, a beautiful animal, was auctioned off for 63,000 Lei. This horse was taken to Germany with a few other especially selected horses.” (Hoffnungstal, p. 31) [Note: This was approximately $10,000 and probably occurred about 1940. This price would put the horse in the category of an exceptional stud of National Champion status.]

Hoffnungstal’s varied businesses

Hoffnungstal also had several mills used for making flour and oil. The first steam-driven mill was built by Friedrich Schott in the late 1800s. (He later sold the mill to finance his family’s immigration to America.) Farmers from many of the surrounding villages came to Hoffnungstal to use the mills.

Although the main occupation in Hoffnungstal was farming, there were many craftsmen in the village as well. Sometimes they practiced their craft as a sideline; sometimes it was their main occupation. In 1940, the primary trades represented included metal workers, blacksmiths, carpenters, cartwrights, shoemakers, harness makers, mill owners, and game keepers. There were also individuals who were coopers, tailors, brick makers, quarrymen, land surveyors, night watchmen, roofers, and midwives. There was also a butcher, a beekeeper, a truck garden farmer, a cistern finisher, and a gravedigger. “Roaming” craftsmen, who did work on a commission basis, included watchmakers, a sewing machine repairman, a pots and pans repairman, and a knife grinder. Moldavians often were hired as cattle herdsmen, and Russians did sheep shearing on a seasonal basis.

Hoffnungstal’s economic connection with the village of Beresina was especially important, because it was a source of wood for Hoffnungstal’s carpenters and wagon makers, as well as the nearest train station.

(To be continued)