John Coulthart's Blog, page 20

August 3, 2024

Weekend links 737

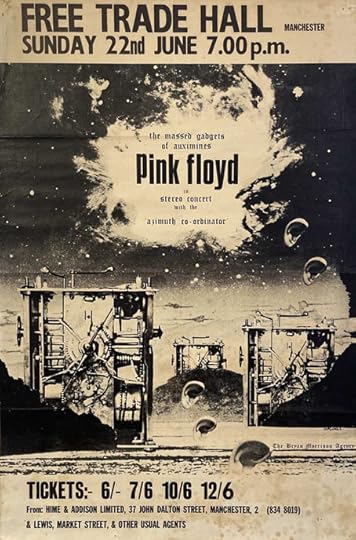

The Massed Gadgets of Auximines – Pink Floyd – in stereo concert with the “Azimuth Co-ordinator”. Design by Hipgnosis, 1969.

• At Rond1900: Sander Bink explores the life of another obscure Dutch Symbolist, Léonard Sarluis (1874–1949): artist, friend of Oscar Wilde and lover of Alfred Jarry.

• At Spoon & Tamago: Manga artist Hirohiko Araki pays tribute to Osaka station’s history and culture with new public art sculpture.

• At Public Domain Review: Scenes of reading on the early portrait postcard by Melina Moe and Victoria Nebolsin.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: 33 films that either faked ingesting LSD or did.

• At Bandcamp: Blissful Noise, Bad Vibes: A Doomgaze Primer.

• Mix of the week: Azimuth Coordinator by Tarotplane.

• New music: Global Transport by Monolake.

• The Strange World of…Gay Disco.

• Postcard From Jamaica (1967) by Sopwith Camel | Postcards Of Scarborough (1970) by Michael Chapman | An Unsigned Postcard (1991) by Tuxedomoon

July 31, 2024

Daybreak in the Universe, a film by Julius Horsthuis

Being 25 minutes of alien architecture, or extraterrestrial lifeforms, or DMT landscapes… There’s something of all these things in Daybreak in the Universe, a journey through shimmering fractal geometries, with music by synthesist Michael Stearns from his 1980 album, Morning Jewel. Looks best on a big screen, needless to say. There are similar explorations at the Julius Horsthuis YouTube channel.

Via Scotto Moore.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Cosmic Flower Unfolding, a film by Ben Ridgway

July 29, 2024

Occult rock: The Devil Rides In

The Devil rode in at the weekend on three shiny compact discs crammed with Satanic psychedelia and the pentagram-branded rock music of the early 1970s: 55 tracks in all. I’d been hoping for some time that an enterprising anthologist might put together an officially-sanctioned collection like the series of mixes compiled by The Ghost of the Weed Garden. Cherry Red Records are ideal candidates for the task, having distinguished themselves in recent years with a series of multi-disc compilations that mine specific periods of British music: psychedelia, heavy rock, folk, punk, reggae, post-punk, experimental electronics, electro-pop, and so on. The Devil Rides In bears a subtitle that ties the collection to the prime years of the Occult Revival, “Spellbinding Satanic Magick & The Rockult 1966–1974”, a period when the Aquarian transcendence of the hippy world was jostling with darker trends in the media landscape. 1967 was the year the Beatles put Aleister Crowley on the cover of the Sgt Pepper album; it was also the year that Hammer were filming their first Dennis Wheatley adaptation, The Devil Rides Out. The song of the same name by Icarus appears on the second disc of this compilation, a single intended to capitalise on the publicity generated by the film. For all the serious occult interest that flourished during by this period many of the cultural associations were frivolous or superficial ones, either cash-ins like the Icarus single or exploitations by those who followed in Dennis Wheatley’s wake. Serious occultists no doubt abhorred the exploitation but it helped create a market for Man, Myth and Magic magazine, and for all the reprints of grimoires and other magical texts that were appearing in paperback for the first time. I’ve always enjoyed the frivolous side of the Occult Revival, probably because I grew up surrounded by it. Without Ace of Wands and Catweazle on the TV I might not have been so interested in my mother’s small collection of occult paperbacks, or gravitated eventually to the Religion and Spirituality shelves of the local library.

The Devil Rides In was conceived, designed and annotated by Martin Callomon, working here under the “Cally” pseudonym he uses for many of his activities. The accompanying booklet is evidence of a labour of love, the detailed notes being illustrated throughout with Occult Revival ephemera: film posters and magazines (the inevitable Man, Myth & Magic), also plenty of paperback covers which tend towards the lurid and exploitational end of the magical spectrum (the inevitable Dennis Wheatley). Cherry Red always take care with their sleeve notes but Cally’s booklet design has gone to considerable lengths to track down many obscure book covers, some of which I’d not seen before. The same diligence applies to the music, with the proviso that compilations are often restrained by the hazards of licensing law. There’s a track list on the Cherry Red page but this doesn’t tell you that the collection is divided into eight themed sections:

1) Buried Underground

2) Phantom Sabbaths

3) Popular Satanism

4) She Devils

5) Folk Devils

6) Evil Jazz

7) Beelzefunk

8) Let’s All Chant

Many of the selections on the first disc are the kinds of songs I’d usually avoid outside this collection, the lumbering heavy rock that filled the Vertigo catalogue for the first half of the 1970s. But groups that you wouldn’t want to hear at album length become palatable when placed in a context such as this.

Among the immediate highlights I’d pick Race With The Devil by The Gun, already a favourite of mine by the group that launched Roger Dean’s career as a cover artist; Black Mass by Jason Crest, a psychedelic B-side whose subject matter and high-pitched wailing is a precursor of the heavy-metal future; and the perennially popular Come To The Sabbat by Black Widow. A few of the selections have been chosen more for their name than anything else, something I’m okay with so long as the choices are good ones. Cozy Powell’s Dance With The Devil, for example, is a drum-led instrumental with a musical theme swiped from Jimi Hendrix; it has nothing at all to do with the Devil but it’s still a great piece of music which was also a surprise UK chart hit in 1973. More of a reach is Magic Potion by The Open Mind, a song about psychedelic drugs not witches’ brews. I included this one on one of my psychedelic mixes so I can tolerate its presence here. Less tolerable is Long Black Magic Night by Jacula, an Italian prog band whose contribution features Vittoria Lo Turco as “Fiamma Dallo Spirito” stuck in one channel of the stereo mix where she intones monotonously in very poor English; the cumulative effect is diabolical in the wrong way. And I would have prefered Julie Driscoll’s long, slow version of Season Of The Witch instead of Sandie Shaw squeaking her way through Sympathy For The Devil. But you can’t always get what you want, as Mick Jagger reminds us elsewhere, something which is especially true of compilation albums.

Psychedelic devilry by Circa from the gatefold interior of Sacrifice by Black Widow.

Notable by their musical absence is the group most commonly associated with early occult rock, Black Sabbath, whose debut album is alluded to in the colouring of the booklet cover art, while the band themselves appear in a news clipping on the back. I’m sure they would have been included if the licensing had allowed it but Birmingham’s heaviest export aren’t exactly starved for attention. Sabbath may not be present musically but listening to some of their contemporaries you can see why Ozzy and co. were so successful despite their debut album being critically lambasted in 1970. Black Widow released Sacrifice a month after Black Sabbath, something which might have set the two bands in competition if they didn’t sound so different. Come To The Sabbat has an intoxicating chorus but the song is distinctly jaunty, and very typical of the era with its folky flute lines. The opening track on Sabbath’s debut is pure horror by comparison, and like nothing else in this collection. If Cally had managed to include the song it would have overshadowed everything else.

Even before The Devil Rides In fell through the letterbox I’d been wondering whether this might be the start of another Cherry Red compilation series or whether Cally’s collection has exhausted the best material. It’s certainly the best of the British end of this niche…or almost; there’s no Black Mass: An Electric Storm In Hell by White Noise, another dose of pure horror that’s the scariest thing about Dracula AD 1972 when some of the music is used in the vampire-summoning scene. Not everything on The Devil Rides In is British either—apart from Jacula, Coven were American, while Curtis Knight was an American singer with a British band—but Britons have had a particular taste for this kind of material, and a more relaxed attitude towards its commercial exploitation than you’ll find elsewhere. In American music of the same period there are plenty of songs about witches but the Devil is only present as a hangover from the blues tradition. The closest you get to anything in this collection is Dr John’s amazing voodoo album, Gris-Gris, and the clone of the same recorded by Exuma in 1970. Everything else tends to be novelty Halloween songs, comedy rock’n’roll by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, or one-off things like Mort Garson’s Moog album, Black Mass, which was credited to “Lucifer”. American musicians in 1970 would have had to deal with greater pushback from the tireless Christian complainers, even though any cultural manifestation of the Devil always reinforces the Christian theological model: if the Devil exists then so does his opposite number. Nat Freedland’s documentary album, The Occult Explosion, was an American production released in 1973 which featured interviews with Alan Watts, Anton LaVey and others. For the musical component, however, they had to use two tracks by Black Widow which suggests that Coven weren’t available and they couldn’t find anything home-grown to take their place. Which also suggests that this compilation may well be a one-off despite the recommendations in Cally’s notes for further listening. There’s apparently a Spotify playlist containing some of the music they couldn’t include on the CDs but I don’t use Spotify so I can’t confirm this: try searching for “The Devil Rides In” and see what happens. The Devil still has the best tunes but in this case you’ll need an account to hear them.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The most unusual magazine ever published: Man, Myth and Magic

• Jan Parker’s witches

• Llewellyn occult magazine and book catalogue, 1971

• Typefaces of the occult revival

• Dreaming Out of Space: Kenneth Grant on HP Lovecraft

• MMM in IT

• The Occult Explosion

• Wilfried Sätty: Artist of the occult

• Aleister Crowley on vinyl

July 27, 2024

Weekend links 736

South Polar Map of Jupiter by the Cassini spacecraft, 2000.

• “A ghostly train journey on a forgotten branch line transports a son, Jozef, visiting his dying Father in a remote Galician Sanatorium. Upon arrival Jozef finds the Sanatorium entirely moribund and run by a dubious Doctor Gotard who tells him that his father’s death, the death that has struck him in his country has not yet occurred, and that here they are always late by a certain interval of time of which the length cannot be defined. Jozef will come to realise that the Sanatorium is a floating world halfway between sleep and wakefulness and that time and events cannot be measured in any tangible form.” The Quay Brothers have finished their third feature film, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, a combination of live action and animation which is being premiered next month at the Venice film festival. No sign of a trailer as yet but the curious can prime themselves by watching (or rewatching) the Quays’ Street of Crocodiles—their first adaptation of Bruno Schulz—or Hourglass Sanatorium, the first screen adaptation of Schulz’s stories by Wojciech Has.

• “No one is sure when the tremendous whirl—the largest and longest-lived storm in our current solar system, with a diameter wider than planet Earth and wind speeds of more than 260 miles per hour—began. Or why it’s red. Or even who first observed it…” Katherine Harmon Courage on Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.

• New music: Bórdice by Nestor, and Nightfall by Trentemøller, the latter with a video swiping shots from Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon. Nice song but musicians really need to stop plundering independent film-makers when they want some visual embellishment.

• At The Daily Heller: Steven Heller talks to Drew Friedman about Friedman’s new book of caricatures, Schtick Figures.

• Mixes of the week: A mix for The Wire by Miaux, and Isolatedmix 127 by David Douglas & Applescal.

• DJ Food’s latest psychedelic trawl is a collection of book covers, puzzles, etc, designed by Peter Max.

• At Unquiet Things: Vic Prezio’s Gothic book covers.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Morgan Fisher Day.

• Jupiter (1990) by NASA Voyager Space Sounds | Jupiter! (Feed Your Head Mix) (1994) by System 7 | Jupiter Collision (2002) by Redshift

July 24, 2024

Frank C. Papé’s The Well of Saint Clare

I was asked recently if I’d ever written anything about British illustrator Frank C. Papé (1878–1972). The answer was no for two reasons, the first being that where book illustration is concerned I like to be able to point to whole books, and until recently there hasn’t been much of Papé’s work available in complete editions. The second reason is that Papé’s illustration is often broadly comic, to a degree that had he been born a generation or two later he might have been drawing humorous comic strips or editorial cartoons. Papé was very adept on a technical level but his drawings aren’t always to my taste so I’ve never spent much time looking for his books.

The first of those caveats has been ameliorated by recent uploads at the Internet Archive which include this volume, one of several Anatole France editions with Papé illustrations. The Well of Saint Clare (1928) is a collection of religious stories set in the medieval era. The book appeared a few years after Papé had illustrated James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice, a quasi-medieval fantasy which was the subject of a celebrated obscenity case in the USA. Anatole France’s satires were almost as contentious for a time—the Vatican put his books on their prohibited list—which leaves me wondering whether Papé had a natural inclination for risqué material or whether his publishers pushed him in this direction. Probably a little of both.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Ray Frederick Coyle, 1885–1924

July 22, 2024

Inventions for echo guitars

I thought about calling this one A Young Person’s Guide to Echo Guitar but that would only end up attracting people expecting a tutorial of some kind. It’s not really a guide either, more an overview of a musical idiom whose predominant feature is guitar played through analogue or digital echo machines, often without additional instrumentation. I have a predilection for this kind of thing, something I was thinking about recently when listening to Michael Brook’s Cobalt Blue album.

A Watkins Copicat as seen (and used) in Berberian Sound Studio.

This is also another example of technology inspiring the development of new forms of music. Echoed guitar dates back to the early days of rock’n’roll but it was the advent of echo machines like the Watkins Copicat that made it possible for guitarists to produce rich clusters of sound without any other instrumentation. The Copicat was portable and could be activated with a foot pedal, making it perfect for guitar players. These machines aren’t always credited in album notes but I’d guess that one or two of the earlier recordings on this list have been made using Copicats. (John Martyn, however, preferred an Echoplex.) As for the more recent examples, one reason to write this piece is to fish for suggestions of things I may have missed. I’m sure I put a Bandcamp discovery in one of the weekend lists that involved quantities of echo guitar but I’m going to have to trawl back through old posts to find it.

Echo (1972) by Achim Reichel and Machines

Achim Reichel is an odd character in German music. In the 1960s he was a singer and guitarist in a popular Beatles-like band, The Rattles, followed by a stint with a short-lived psychedelic outfit, Wonderland; by the 1980s he was a very successful German pop artist. For a few years in the 1970s, however, he recorded a handful of albums which in later years he seems to have found embarrassing despite their being regarded now as highlights of the so-called Krautrock era. Echo is the most adventurous of these, a double album which used to be a frustrating item, being praised by those who heard it while also being very difficult to find. The two discs contain four suites that fill each side, the first one opening with long stretches of echo-guitar which soon establish the mood of the album with their unpredictable evolution. Echo as a whole is a succession of unexpected swerves and musical detours, taking in orchestral arrangements, field recordings, snatches of song, heavy rock, and (regrettably) a long stretch of glossolalic jabbering that tests the listener’s patience. I forgive the latter when the rest of the album is so good. The guitar sound that Reichel developed here became a recurrent feature of his music for the next two years, especially in live performances.

Reichel’s popularity has overshadowed his earlier recordings to an extent that Echo wasn’t given an official reissue until 2017 when he relented to persistent requests and put together a 10-disc CD set, The Art Of German Psychedelic 1970–74. This is too much Reichel for the casual listener but if you can bear his occasional lurches into Steppenwolf-style psych-rock there’s a great deal of excellent music in the collection. Among the exclusive offerings is a superb live performance of kosmische improvisation from 1973, also an entire disc of unaccompanied echo-guitar recordings.

Wilburn Burchette Opens The Seven Gates Of Transcendental Consciousness (1972)

Many of Wilburn Burchette’s albums would be suitable here but I chose this one because I like the title and it has the grooviest cover. Burchette’s subtitle—“A Transcendental Ballet For The Mind Of God”—suggests something more overtly cosmic than the music itself which is less freeform than Achim Reichel. This is also the first self-released album in a list which coincidentally contains several such releases.

• Opens the Seven Gates of Transcendental Consciousness

Inventions For Electric Guitar (1974) by Ash Ra Tempel/Manuel Göttsching

Cult album time. This one was labeled as the sixth release by Ash Ra Tempel but it’s really the first solo album by Manuel Göttsching, in which he used multi-track recording together with copious echo and other effects to create something that sounds more like the synthesizer music of 1974 than anything made with guitars. The cover art fixes the album in a specific time but the music itself is timeless. In 2010 he performed the album in its entirety at a Japanese music festival, assisted by three other guitarists: Steve Hillage, Elliott Sharp and Zhang Shouwang. If there’s a complete video of this concert I’ve yet to see it but there is this extract showing the musicians playing Pluralis.

Samtvogel (1974) by Gunter Schickert

The second self-released album on the list, and Gunter Schickert’s musical debut. I’m not keen on Schickert’s songs but the second side of Samtvogel (Velvet Bird) is filled by 21 minutes of echo-guitar.

• Wald

Live At Leeds (1975) by John Martyn

The third self-released album is on the list for the 18-minute version of Outside In, originally a shorter piece on Martyn’s Inside Out album which he often played live in much longer versions. I don’t know when Martyn started playing his guitar through an Echoplex but his technique was well-established by 1973, which puts him in the vanguard of the form. He’s also unusual in favouring an acoustic guitar with a pickup connected to his effects units. I was first made aware of this in 1981 via an astonishing performance of Outside In on the BBC’s A Little Night Music. Until then I’d not heard much of his music at all, and always assumed he was a rather typical folk/blues artist, not someone who did things like this. A few weeks ago I was very pleased to find a compilation of Martyn’s early BBC appearances which includes the 1981 Outside In performance. And if you zip to the beginning of the video you can also see him playing Skip James’ I’d Rather Be The Devil in his own echo-inflected manner.

Cobalt Blue/Live At The Aquarium (1992) by Michael Brook

Michael Brook makes the list with two separate albums, Live At The Aquarium being a performance of Cobalt Blue which was given a limited release shortly after the studio album. (Both albums were later reissued as a double-disc set.) Brook is often credited with playing “Infinite Guitar” but this is a form of endless sustain, not an echo effect.

The Golden Vibe (2019) by Steve Hillage

Released in 2019 but actually recorded in 1973, this isn’t really an album as such, more a collection of sketches for future compositions. Hillage recorded the music while still in Gong but the pieces all look forward to the solo albums he was recording a few years later, with early try-outs for The Dervish Riff, Leylines To Glassdom and The Golden Vibe.

Improvisations For Echo Guitar (2023) by Tarotplane

The most recent example to date…or is it? I’m sure there’s more to be found at Bandcamp, for example, but the search options there need serious improvement.

• Improvisations For Echo Guitar

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Fender guitar catalogue, 1976

• Manuel Göttsching, 1952–2022

July 20, 2024

Weekend links 735

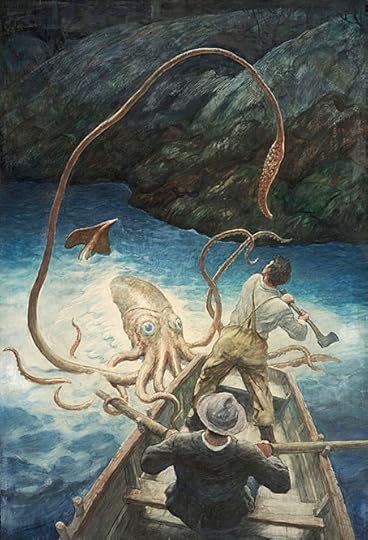

The Adventure of the Giant Squid (c.1939) by NC Wyeth.

• Mix of the week is a superb XLR8R Podcast 860 by Kenneth James Gibson. Elsewhere there’s DreamScenes – July 2024 at Ambientblog, and Deep Breakfast Mix 267 at A Strangely Isolated Place.

• A trailer for a restored print of Time Masters (1982), the second animated feature by René Laloux, with character designs/decor by Moebius. Now do Gandahar.

• Coming soon from Strange Attractor: Music From Elsewhere: Haunting Tunes From Mythical Beings, Hidden Worlds, and Other Curious Sources by Doug Skinner.

Not only a prolific lyricist, Lovecraft considered his main vocation to be poetry. And at its best, his verse can be judged an apt expression of his philosophical vision, in which cosmic horror embodies the predicament of all sentient beings in a meaningless universe. That Lovecraft’s poetry never reaches the heights attained by such Modernists as T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound should not diminish the fact that his is verse that, in the most archaic of ways, advances a startlingly modern metaphysic, a poetic encapsulation of what Thomas Ligotti in The Conspiracy Against the Human Race describes as an affirmation that the universe is a “place without sense, meaning, or value.” Lovecraft, with his antiquated prosody and his anti-human ethics, presented readers with a type of counter-modernist poetry. Ironically, he is the radical culmination of William Carlos Williams’s injunction of “No ideas but in things;” he is an author for whom there are only things. Graham Harman in Lovecraft and Philosophy describes Lovecraft as a “violently anti-idealist” who “laments the inability of mere language to depict the deep horrors his narrators confront.” Unpleasant stuff, for sure. It is verse that at best exemplifies something that controversial poet Frederik Seidel called for in the Paris Review: “Write beautifully what people don’t want to hear.”

Ed Simon on The Unlikely Verse of HP Lovecraft

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, by HP Lovecraft.

• At Spoon & Tamago: An ethereal bubble emerges from a Japanese townhouse.

• New music: The Head As Form’d In The Crier’s Choir by Sarah Davachi.

• Mabe Fratti’s favourite albums.

• Bubble Rap (1972) by Can | Bubbles (1975) by Herbie Hancock | Reverse Bubble (2014) by Air

July 17, 2024

Thomas Mackenzie’s Crock of Gold

Thomas Mackenzie (1887–1944) was an English illustrator whose work has appeared here before via his illustrations for a verse rendering of the Aladdin story by Arthur Ransome, a typical product of the 1920s’ boom in illustrated children’s books. James Stephens’ The Crock of Gold (1912) is a vessel of a different kind, too sophisticated for children yet suffused with a fairy-tale quality, this is more like a fable for adults:

A mixture of philosophy, Irish folklore and the “battle of the sexes”, it consists of six books, Book 1 – The Coming of Pan, Book 2 – The Philosopher’s Journey, Book 3 – The Two Gods, Book 4 – The Philosopher’s Return, Book 5 – The Policemen, Book 6 – The Thin Woman’s Journey, that rotate around a philosopher and his quest to find the most beautiful woman in the world, Cáitilin Ni Murrachu, daughter of a remote mountain farm, and deliver her from the gods Pan and Aengus Óg, while himself going through a catharsis. (more)

The illustrations, which Mackenzie created for a 1926 edition, are a little different to his earlier work, tending in places towards that Hellenic stylisation that became increasingly popular in the graphic art of the 1920s and 30s. The depictions of Pan remind me that I once tried to catalogue all the appearances of the god in prose and poetry from the 1890s on. The years from 1890 to 1930 saw Pan become a persistent presence in English literature, while also giving a title to one of the leading Jugendstil journals. The idea of trying to document all this activity is an attractive one until you set to work and find that there are many more examples than you imagined, not all of them indicated in the titles of the works.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Reflected Faun

• The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

• The Great God Pan

• Peake’s Pan

July 15, 2024

Tokyo Loop

Tokyo Strut (Masahiko Sato, Mio Ueta), Tokyo Trip (Keiichi Tanaami)

Fishing Vine (Mika Seike), Yuki-chan (Kei Oyama).

Search for the phrase “Tokyo Loop” and you’ll be offered information about the Yamanote rail line which runs in a circle through Japanese capital. The Loop that concerns us here is very different, a collection of 16 short films made in 2006:

Tokyo’s centre for experimental and art cinema, Image Forum, under the guidance of program director Takashi Sawa and coordinator Koyo Yamashita, has a knack for putting together some clever screening packages together for the Image Forum Festival every year. Many of these packages, such as Thinking and Drawing, make their way into international festivals, and in some cases even onto DVD. Such is the case with the 2006 omnibus Tokyo Loop featuring the work of both established artists like Yoji Kuri, Taku Furukawa, Keiichi Tanaami, Nobuhiro Aihara, as well as exciting younger artists such as Kei Oyama, Mika Seike, Tabaimo, and Tomoyasu Murata.

Tokyo Loop came out of Image Forum’s desire to do something to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of Stuart Blackton’s animation “Humorous Phases of Funny Faces” (1906), considered by many the first publicly screened animated film. Sawa and Yamashita commandeered the help of Furukawa who contributed to the project with a film of his own and helped recruit other independent animation and experimental artists.

The 16 artists were asked to contribute a short film inspired by the city of Tokyo. The films would also be linked by the participation of Seiichi Yamamoto, a well-known musician from Osaka’s underground music scene who composed the score. Yamamoto corresponded with the artists during the production process. He composed the music in advance based upon the sketches and storyboards provided by each animator, then revised them to fit the final edit of the film. (more)

Dog & Bone (Kotobuki Shiriagari), Public Convenience (Tabaimo)

Tokyo (Atsuko Uda), Black Fish (Nobuhiro Aihara).

Everything in the collection is animated to some degree but the experimental factor dominates, with the films running through a range of different styles and techniques. I especially enjoyed Tokyo Strut, a minimal display of wireframe animation; and Nuance, a film where nocturnal drives through city streets are presented with flickering rotoscoped shapes and colours.

Unbalance (Takashi Ito), Tokyo Girl (Maho Shimao)

Manipulated Man (Atsushi Wada), Nuance (Tomoyasu Murata).

All the films are wordless, with scores that run through a variety of musical styles, from abrasive noise and glitchy electronics to simple melodies played with guitar and synthesizer. I didn’t recognise Seiichi Yamamoto‘s name at first but he’s a versatile and prolific musician whose collaborations with other artists (Boredoms among them) are copious enough for him to be lurking on some of the Japanese CDs on my shelves. One of his own bands, Omoide Hatoba, released Kinsei in 1996, an album I bought when it was released but have never played very much. Time to give it another airing.

Hashimoto (Taku Furukawa), Funkorogashi (Yoji Kuri)

Fig (Kouji Yamamura), 12 O’Clock (Toshio Iwai).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Chirico by Tanaami and Aihara

• The Midnight Parasites by Yoji Kuri

• Sweet Friday, a film by Keiichi Tanaami

• Tadanori Yokoo animations

July 13, 2024

Weekend links 734

Illustration by Frank Mechau for The Love of Myrrhine and Konallis (1926) by Richard Aldington.

• At A Year In The Country: The Delaware Road: “A surreal post-war Albion and Quatermass meets Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.”

• At Colossal: Rajesh Vora photographs the unique Punjabi tradition of adorning homes with sculptural water tanks.

• At Unquiet Things: The fragile eternity of Margaretha Roosenboom’s floral still lifes.

Illustration by Frank Mechau for The Love of Myrrhine and Konallis (1926) by Richard Aldington.

• New music: Damaged by Ghost Dubs, and Selene by Akira Kosemura & Lawrence English.

• At Public Domain Review: Allison C. Meier on The Dance of Death across centuries.

• RIP Shelley Duvall. Related: Anne Billson on Shelley Duvall: her 20 greatest films.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Galerie Dennis Cooper presents…Félicien Rops.

• Steven Heller’s font of the month is Sisters.

• Eno Williams’ favourite records.

• Two Sisters (1967) by The Kinks | All Your Sisters (1996) by Mazzy Star | Two Sisters (2017) by Gel-Sol

John Coulthart's Blog

- John Coulthart's profile

- 31 followers