John Coulthart's Blog, page 323

January 5, 2011

Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration #1

Last year saw an exploration here of the fecund pages of Jugend magazine so in the same spirit I'm embarking on a serial delve into Jugend's more serious contemporary Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration. I've made a couple of posts in this direction already but these were done before I'd had a chance to look properly through the editions at the Internet Archive, the first thirty of which form a collection which comprises some 7500 pages. Since few people would want to download and trawl through that mountain these posts can serve as a select guide to the contents.

Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration was published by Alexander Koch in Darmstadt and the first issue is dated October 1897–March 1898. Jugend was a humour magazine so the contents tend to be frivolous and lighthearted, Koch's title by contrast was a guide to the best of German contemporary art and design and has the advantage of featuring furniture and architectural designs as well as graphic material. The content of this first issue is relatively sedate compared to some of the later numbers when the Art Nouveau style builds up a head of steam. There's some astonishing design work in subsequent issues, as well as further illustration discoveries like Marcus Behmer; watch this space.

Illustrations by JR Witzel also appeared regularly in Jugend.

Designs by Melchior Lechter from a lengthy article about the artist. As well as examples of his stained glass work the piece shows some of his paintings which deal in a kind of mystical Christianity that's distinctly Symbolist in tone.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Marcus Behmer, 1879–1958

• The art of Melchior Lechter, 1865–1937

• Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration

• Jugend Magazine revisited

January 4, 2011

Art Deco bindings

Contes Oscar Wilde (c. 1928), design by Paul Bonet.

Two selections from this gallery of bookbindings from the 1920s. Few books receive this kind of treatment today but it's by no means a lost art, The Guild of Book Workers has examples of recent designs.

La Canne de Jaspe (c. 1925), design by Pierre Legrain.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Prismes

• The art of Thayaht, 1893–1959

• The Mentor

• The art of Cassandre, 1901–1968

• The Decorative Age

• The World in 2030

January 3, 2011

Alastair's Carmen

"The artist at home" from Alastair: Illustrator of Decadence (1979) by Victor Arwas.

More Beardsley derivations in the form of some illustrations by Hans Henning Voigt (1887–1969), better known as Alastair, and an artist who more than anyone carried the Beardsley style and the fin de siècle ethos into the 20th century. If the photograph above is anything to go by he seemed to take Beardsley's effete and languid characters as role models for an equally effete and languid manner.

The drawings here are a selection from twelve pieces for a 1920 edition of Prosper Mérimée's Carmen, the novel upon which Bizet based his opera. Alastair for me has always been an artist whose enthusiasm for his subject matter outpaced his technique, his figure drawing can be rather weak at times which perhaps explains some of his more eccentric costume designs. Every so often the weakness becomes a virtue when it provides a surprising composition. Carmen didn't seem to inspire him as much as other works, his illustrations for Oscar Wilde's Salomé are a lot better and I may post some of them here if I can find a way of scanning my Victor Arwas book without spoiling it. There still isn't much else of his work on the web but S. Elizabeth did make a start recently with her post A Decadent Parade of Outrageous Fancies at Coilhouse.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Willy Pogàny's Lohengrin

• Willy Pogàny's Parsifal

January 2, 2011

After Beardsley by Chris James

I have Greg Jarvis of Flowers of Hell to thank for prompting this discovery. Greg left a comment on an earlier post about Aubrey Beardsley's influence in the musical world in which he drew my attention to some Flowers of Hell cover art and a video inspired by Beardsley's Morte Darthur drawings. The video reminded me of a short animated film I'd known about for years but never seen, After Beardsley by Chris James. Sure enough it too is on YouTube, to my great surprise since I swear I've searched in vain for this in the past.

After Beardsley was made in 1981 and my knowledge of the film is a result of its being praised by V&A curator Stephen Calloway. The picture of Aubrey in a hospital bed featured in the 1993 V&A exhibition High Art and Low Life: The Studio and the fin de siècle, and is also the final picture in Calloway's 1998 biography of the artist. Chris James describes the film thus:

The film After Beardsley attempts to depict today's world through Beardsley's eyes and in his drawing style…Beardsley is 'resurrected' from his death bed and begins to walk through time to the present. On his journey he witnesses the evolution of the car and of air and sea travel, then climbs a phallic mountain before descending into 20th century New York City. [The] ghost of Aubrey Beardsley explores the urban jungle of New York City where, amongst other things, he sees Bob Dylan as a satyr sitting by an iconic 1959 Chevy, and Lenny Bruce being injected with heroin. He is then beckoned by Patti Smith (as Beardsley's Messalina) into a hospital room where he finds himself hooked up to life support equipment. His hospital persona shows his ghost the horrors of the present day—overpopulation, pestilence starvation, and death. Via John Lennon, he sees the horrors of a nuclear winter. The premise of the film is that, if Beardsley had been alive today instead of the 1890s, modern medicine would have kept him alive, but that, having had a glimpse of where the world was heading, he may have chosen to die anyway. Written and drawn by Chris James, after Aubrey Beardsley. Music by Ronnie Fowler.

As Beardsley pastiche the drawing is some of the best I've seen, it's easy to see why Calloway would be impressed. The film is split into three parts here, here and here, and Chris James has more animation on his YT channel. I'd be tempted to ask for a better quality copy but for now seeing the film at all is good enough.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Beardsley's Rape of the Lock

• The Savoy magazine

• Beardsley at the V&A

• Merely fanciful or grotesque

• Aubrey Beardsley's musical afterlife

• Aubrey by John Selwyn Gilbert

• "Weirdsley Daubery": Beardsley and Punch

January 1, 2011

Weekend links: New Year edition

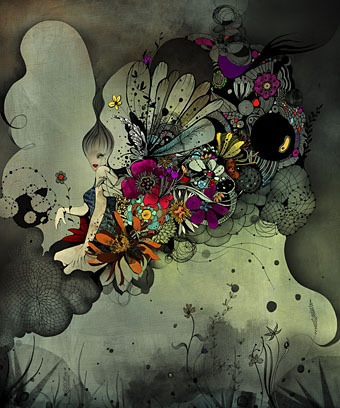

Flower Me Gently (2010) by Linn Olofsdotter.

• "Many of Moorcock's editorials are published here, and they still make exhilarating reading. Then, as now, Moorcock set his face against a besetting English sin: a snobbish parochial weariness, an ironic superiority to the frightful oiks who have started filling up the streets. You can almost hear, behind the languorous flutter of the pages, Sir Whatsits sniggering to Lady Doo-Dah. It still goes on, and it's usually the same flummery in different clothes. Moorcock not only would not go to the party: he threw the literary equivalent of explosive devices into the Hampstead living rooms." Michael Moorcock's Into the Media Web reviewed. And also here.

• "Beefheart channeled a secret history of America, the underbelly of a continent and a culture that has now all but vanished along with one of its greatest poets." Jon Savage on the life and work of the late Captain.

• Miniatures Blog, in which musician Morgan Fisher works his way through each of the fifty one-minute tracks on his extraordinary Miniatures compilation album, with details and anecdotes about the artists and the recording of each piece.

• Look at Life: IN gear (1967). A Rank Organisation newsreel about Swinging London. Sardonic commentary and some great colour photography showing how the often shabby reality differs from the caricature. Many of the shots are familiar from documentaries about the era but this is the first time I've seen them all in one place.

Predator (Self-portrait) by Linn Olofsdotter.

• Lewis Carroll's new story: The Guardian's review of Through the Looking-Glass from December, 1871. Related: My Through the Psychedelic Looking-Glass 2011 calendar is now reduced in price.

• The United Kingdom and Ireland as seen from the International Space Station, December, 2010. Related: Spacelog, the stories of early space exploration from the original NASA transcripts.

• The "Big Basket" Fraud, 1958: "…there seems to be a limited segment with a one-track mind interested in seeing an exaggerated masculine appendage."

• "Ancient arena of discord": a billboard for King's Cross by Jonathan Barnbrook. Related: Vale Royal by Aidan Andrew Dun.

• The inevitable Ghost Box link, Jim Jupp is interviewed at Cardboard Cutout Sundown.

• Amazon is still playing the random moral guardian at the Kindle store.

• Antwerpian Expressionists at A Journey Round My Skull.

• Salami CD and vacuum packaging by Mother Eleganza.

• Paris 1900: L'Architecture Art Nouveau à Paris.

• Bill Sienkiewicz speaks about Big Numbers #3.

• Philippe Druillet illustrates Dracula, 1968.

• Aesthetic Peacocks at the V&A.

• Well Did You Evah! (1990), Deborah Harry & Iggy Pop directed by Alex Cox.

December 31, 2010

02011

Life magazine for March 2nd, 1911, with cover art by Orson Lowell. The Peacock Number, eh? Can't help but wonder what the rest of this issue was like.

02011? Read this.

Happy new year!

December 30, 2010

Blood on the Moon

A final picture to round off the year, a very large view of the recent lunar eclipse by Chris Hetlage. Via NASA's Astronomy Picture of the Day.

December 29, 2010

"Who is this who is coming?"

Whistle and I'll Come to You (1968).

He blew tentatively and stopped suddenly, startled and yet pleased at the note he had elicited. It had a quality of infinite distance in it, and, soft as it was, he somehow felt it must be audible for miles round. It was a sound, too, that seemed to have the power (which many scents possess) of forming pictures in the brain. He saw quite clearly for a moment a vision of a wide, dark expanse at night, with a fresh wind blowing, and in the midst a lonely figure—how employed, he could not tell. Perhaps he would have seen more had not the picture been broken by the sudden surge of a gust of wind against his casement, so sudden that it made him look up, just in time to see the white glint of a sea-bird's wing somewhere outside the dark panes.

MR James, Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad.

One of the alleged highlights of this year's Christmas television from the BBC was a new adaptation of an MR James ghost story, Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad. The film starred John Hurt and came with the same truncated title, Whistle and I'll Come to You, as was used for Jonathan Miller's 1968 version, also a BBC production. The story title comes originally from a poem by Robert Burns. The new work was adapted by Neil Cross and directed by Andy de Emmony, and I describe it as an alleged highlight since I wasn't impressed at all by the drama, the most recent attempt by the BBC to continue a generally creditable tradition of screening ghost stories at Christmas. Before I deal with my disgruntlement I'll take the opportunity to point the way to some earlier derivations. (And if you don't want the story spoiled, away and read it first.)

Illustration by James McBryde (1904).

James's story was published in 1904 along with seven others in Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, the first of four supernatural collections which were adjuncts to the author's theological researches but are now the works for which the name MR James is most widely recognised. A first edition can be found at the Internet Archive which is worth seeing for its illustrations by James McBryde, a friend of James who died before he had a chance to finish illustrating the book. He did manage to complete the two drawings for Whistle shown here and it's a shame the scanned edition is another poor job by Google who haven't copied the pages in high-resolution and manage to blur the linework. McBryde's second drawing has also been used as a cover illustration for various editions.

Illustration by James McBryde (1904).

Illustration by Ernest Wallcousins (1947).

The 1947 edition of The Collected Ghost Stories of MR James features a frontispiece by Ernest Wallcousins depicting the moment when Whistle's unfortunate Professor Parkins is nearly pushed out of his bedroom window by the vengeful ghost. Both McBryde and Wallcousins yield to the temptation of showing us the climax of the story and the ghost itself, something which is arguably a bad idea for this kind of tale. In Wallcousins' case the nebulous spirit has gained a distinctly brawny arm. Ghosts and monsters may possess a substance which overlaps but ghosts in the James manner exist for the most part as intimations whose presence the reader's imagination brings to life. Forcing these intimations into a solid representation does them few favours, a problem which also bedevils film and television adaptions.

Whistle and I'll Come to You (1968).

Jonathan Miller's version of the story dealt superbly with this issue, managing to hint at much and show little except for a couple of crucial moments. Miller aged the character of Parkins (Michael Hordern) with no detriment to the story, and with a recurrence of reflected images suggested that the presence summoned by the blowing of an ancient whistle might be a spectre from Parkins' imagination. It's amusing to read now of James purists being upset by these minor changes, the maulings sustained by the most recent version must have ruptured blood vessels. Miller's film is an excellent example of how to adapt a short story for the screen.

Whistle and I'll Come to You (2010).

Had Miller's version remained unseen since 1968 there might have been a reason to make a new adaptation of the story but it's not a buried treasure by any means; the BBC have shown it several times since, the BFI released it on DVD in 2001 and the film is very familiar to all aficionados of these ghost films. More damaging than the attempt to compete with Miller's version was the ruinous altering of the narrative and a mise en scène which showed little grasp of what makes an MR James story effective.

Neil Cross's adaptation updated James to the present day, a manoeuvre might have worked if it wasn't for a clumsy attempt to explain why Hurt's character wouldn't summon help with his mobile phone. Clumsier still was the tone of the whole thing which seemed ghostly from the outset, with its semi-catatonic characters and gloomy, vapour-filled interiors. John Hurt's retired scholar was given an absent wife and discovered a ring instead of the Templar's whistle, a detail which made nonsense of the story's title and also lost the motor of the story. In place of the escalating horror of Miller's dream sequence there was a confusion of unrelated images. This kind of mangling has never made sense to me, it implies a lack of faith in the original material which the producers have nevertheless committed themselves to adapting. "We can't work convincingly with this hokum," it seems to say, "but we'll do something with it anyway." The film's biggest shocks—someone or something hammering on a hotel door at night—were not only further impositions on the original tale but were plundered wholesale from one of the greatest of all ghost films, Robert Wise's The Haunting. Neil Cross might have benefited from reading James's own ghost story recipe:

Let us, then, be introduced to the actors in a placid way; let us see them going about their ordinary business, undisturbed by forebodings, pleased with their surroundings; and into this calm environment let the ominous thing put out its head, unobtrusively at first, and then more insistently, until it holds the stage. (More.)

From the introduction to Ghosts and Marvels (1924).

MR James published twenty-six ghost stories during his lifetime, only a handful of which have been adapted for film or television. In choosing to rework something which already exists in a superior version the BBC show themselves adept at least in competing with the worst tendencies of Hollywood, where producers and directors see something they like from the past and believe for whatever reason that it can be refreshed or even improved upon. For UK viewers the new Whistle will be screened again late tonight on BBC 1. Anyone who finds themselves unsatisfied by this is encouraged to search out some of the earlier adaptations (see below). Future adaptors, meanwhile, might try creating something new instead of messing with things better left undisturbed.

Recommended viewing:

• Whistle and I'll Come to You by MR James (1968)

• The Stalls of Barchester by MR James (1971)

• A Warning to the Curious by MR James (1972)

• The Stone Tape by Nigel Kneale (1972)

• Lost Hearts by MR James (1973)

• The Treasure of Abbot Thomas by MR James (1974)

• The Ash Tree by MR James (1975)

• The Signal-Man by Charles Dickens (1976)

• Schalcken the Painter by J Sheridan Le Fanu (1979)

• Ghosts and Scholars, home of the MR James Newsletter

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Penda's Fen by David Rudkin

• Kwaidan

• The Watcher and Other Weird Stories by J Sheridan Le Fanu

• Alice in Wonderland by Jonathan Miller

• The Willows by Algernon Blackwood

December 28, 2010

Wildeana #4

I could make these posts a lot more often since there's seldom a week goes by when Oscar Wilde's work or something from his life isn't making the news somewhere. I forget now how I came across the Robert Hichens book but the Beardsley-derived cover design is the best I've seen for this title. The Green Carnation was first published in 1894 and is the notorious roman à clef whose lead characters, Esmé Amarinth and Lord Reginald Hastings, are based on Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas. Hichens paints the pair as very obvious inverts with none of the "is he or isn't he?" subtlety that Wilde managed to sustain in public. For a scandalised London the book seemed to confirm what was already suspected about Wilde and Bosie's relationship.

The cover art is credited to one John Parsons, an illustrator whose other work, if there is any, eludes the world's search engines. This edition was published in 1949 by Unicorn Press and it's something I'm tempted to buy as a companion for my Unicorn Press edition of Dorian Gray.

The following links are to recent articles spotted whilst looking for other things:

• Oscar Wilde, Classics Scholar. A review of The Women of Homer by Oscar Wilde, edited by Thomas Wright and Donald Mead.

• A new Broadway production of The Importance of Being Earnest has actor Brian Bedford playing Lady Bracknell.

• Buyers go Wilde for Oscar as short note to his friend sells for €1,500.

• Outsmarted: What Oscar Wilde could teach us about art criticism.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Philippe Jullian, connoisseur of the exotic

• Wildeana #3

• The voice of Oscar Wilde

• Wildeana #2

• The Oscar Wilde Galop

• Heinrich Vogeler's illustrated Wilde

• Teleny, Or the Reverse of the Medal

• Tite Street then and now

• Wildeana

• Uranian inspirations

• Henry Keen's Dorian Gray

• The real Basil Hallwards

• Dallamano's Dorian Gray

• Oscar Wilde playing cards

• Matthew Bourne's Dorian Gray

• John Osborne's Dorian Gray

• Dorian Gray revisited

• The Picture of Dorian Gray I & II

December 23, 2010

The Snow Queen

Edmund Dulac.

Empty, vast, and cold were the halls of the Snow Queen. The flickering flame of the northern lights could be plainly seen, whether they rose high or low in the heavens, from every part of the castle. In the midst of its empty, endless hall of snow was a frozen lake, broken on its surface into a thousand forms; each piece resembled another, from being in itself perfect as a work of art, and in the centre of this lake sat the Snow Queen, when she was at home. She called the lake "The Mirror of Reason," and said that it was the best, and indeed the only one in the world.

Here in Britain it may not be quite as cold as it was earlier in the month but the Snow Queen still has us in her thrall. Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale was published in 1845 and, like many of the writer's stories, is a blend of the beguiling and irritating: beguiling for the traces of older folk tales in its trolls and their magic mirror, and the Snow Queen as an embodiment of the season; irritating for the Christian gloss which is layered over everything like a sugar-coating. In this respect it's a lot like Christmas; religiose sentimentality papered over winter rituals that are older and darker than the celebrations we're supposed to acknowledge.

Edmund Dulac.

Andersen's story has been illustrated and filmed many times with varying success. The Internet Archive has several illustrated editions, the selections here being from two of the better ones. Edmund Dulac's Stories from Hans Andersen (1911) is one of the shorter collections and features predominantly colour pictures while Dugald Stewart Walker's Fairy Tales from Hans Christian Andersen (1914) is one of the most heavily illustrated as well as having finer renderings of many stories. But not of the Snow Queen in her palace, Dulac beats everyone there.

Dugald Stewart Walker.

This description stood out from the second part of Andersen's tale:

In winter all this pleasure came to an end, for the windows were sometimes quite frozen over. But then they would warm copper pennies on the stove, and hold the warm pennies against the frozen pane; there would be very soon a little round hole through which they could peep…

My sister and I had been reminiscing recently about growing up in the 1960s when central heating and double-glazing were a lot less common than they are today. This meant little or no heating in bedrooms, so very cold weather often meant the same frozen windows which Andersen describes. People in rural places will be familiar with this but it's something I haven't seen for years. When you're a child it's quite an excitement waking up to find that Jack Frost has paid a visit but these days I prefer a warm house.

As usual I'll be away for a few days so the archive feature will be activated to summon posts from the past. Have a good one. And Gruß vom Krampus!

Dugald Stewart Walker.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Dugald Stewart Walker revisited

• More Arabian Nights

• The art of Dugald Stewart Walker, 1883–1937

John Coulthart's Blog

- John Coulthart's profile

- 31 followers