Emma Darwin's Blog, page 4

February 12, 2018

News: This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin

I���m delighted to say that my new book, This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin, will be published by Holland House Books on Darwin Day - 12th February - 2019.

I'm hugely grateful to my wonderful agent Joanna Swainson, of Hardman and Swainson, and Robertt Peet of Holland House Books. But as this is The Itch, I wanted to say a little more, because although the book is rooted in the novelist part of me that wrote The Mathematics of Love and A Secret Alchemy, the writer-about-writing, fresh from Get Started in Writing Historical Fiction, is also involved.

But this book has really come out of my failure to write a different book. For years people have asked me when I was going to write a novel about my family, but as well as my own inhibitions about The Ancestor (of which more here on the blog, and here in the Telegraph) I couldn���t see where the story was. Then I was asked to talk about creative thinking in the wider family, and began to wonder if I could, after all, grow a novel out of the science and the art - the creativity - that runs through two and a half centuries of my family like a seam of Potteries clay.

Books about Charles Darwin and his wife and cousin Emma Wedgwood are legion, but I wanted - creatively speaking I needed - to take the road less travelled. There were the fascinating real lives of Erasmus Darwin and the Lunar Society; Tom Wedgwood, the first photographer; Julia Wedgwood, who as a writer and intellectual was ranked with George Eliot; Ralph Vaughan Williams and his extraordinary love story; and poet and Communist John Cornford, first Briton to be killed in the Spanish Civil War.

But even when I invented a fictional character and slid her into the creative lives of Charles Darwin���s grandchildren - my grandparents��� generation - I struggled. There were ten biographies and memoirs written by and about my major characters - there are two on Gwen Raverat alone - and that was before I tackled the books about secondary characters such as John Maynard Keynes, Rupert Brooke and Virginia Woolf.

But even when I invented a fictional character and slid her into the creative lives of Charles Darwin���s grandchildren - my grandparents��� generation - I struggled. There were ten biographies and memoirs written by and about my major characters - there are two on Gwen Raverat alone - and that was before I tackled the books about secondary characters such as John Maynard Keynes, Rupert Brooke and Virginia Woolf.

Nor was it simply a matter of whether I was ���allowed��� to change my grandmother���s dates, make a villain of a man whose sons, my cousins, are still alive, or write a sex scene involving someone I���d actually met. The real problem was that these people explore their own motives and feelings, and they tell their own stories: where was the space for me to make a story of my own? In trying to do so, I spent three years in a fierce struggle between my heritage and my identity as a writer - and ultimately the struggle nearly killed me.

When I was better, I gave up the novel. But the desire to write about the family went on scratching at me, and at last I realised how I might do it. This Is Not A Book About Charles Darwin is creative non-fiction, and it takes the reader on a journey through my family, evoking them and their times through the lens of my struggle to grow fiction out of them.

I wanted, too, to evoke what it feels like write creatively: to hunt down something that doesn���t yet exist; to spin invention, memory and research together until you can���t tell the difference; to have mere names grow into real-seeming people who have their own life; to take ruthless technical decisions to make your story seem natural and real: to do what Siri Hustvedt describes as "like remembering something which never happened".

So This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin is part memoir, part biography, part book about writing and how stories are told, but at heart it���s the story of how a creative disaster came out of seven generations of creative thinkers. All being well, a year from today it will be on the bookshop shelves. And, meanwhile, in among business as usual on the Itch - which is mostly about your writing - I���ll be blogging about the process of having my writing published, exploring both the facts and the feelings of having a piece of creative work go out into the world.

January 12, 2018

Switching From One to More than One Point-of-View in Your Story?

A few weeks ago, I got an email from a writer, Philippa East, who did our online course in Self-Editing Your Novel (We'll have 300 graduates, by the time the current course has finished. Could you be our 301st?)

Hi Emma - I'm wondering if you have any blogs or can recommend any articles on revising a novel to change it from single POV to a dual POV structure? I understand the basics of writing in multiple POVs, but I'm looking for any help with actually tackling this kind of serious rewrite. Currently I sort of know what I have to do but just don't know how to do it. Thanks for any advice!

I said I didn't know of any articles, but I'd put it on my to-do list, so here goes. If you want a re-cap on the basics of point-of-view, and the possibilities when you tell a story through more than one point-of-view, pop over to the Toolkit. Here, I'm assuming that you've taken those posts on board (or know it all already), are well into the project and are reasonably happy with it in other ways. And for now we'll stick to the conventional assumption that once you've decided which character's point-of-view you're working in, you can only show things that they could and would experience, understand or know. (Although that is only the conventional view: for a different take, scroll down my post on internal narrators).

So, if it was all from Ann's PoV, how do you decide what to re-work in Bill's, or Con's? There are two main things to think about:

What's already "on-stage": existing scenes. In terms of scenes in which Ann and Bill, or Con, or all three, are already both present, you could try reading through each scene with a highlighter, say, and marking which bits would be fruitful in Bill's or Con's. The precise moment of shift might be obvious, or it might be something you decide as you re-work the scene, and realise where there's a natural point to move out of one head and into the other. For more about how to move PoV - and yes, of course you can do it mid-scene - click that link.

What used to be "off-stage": new scenes. If Bill or Con was at events that Ann wasn't, you can now write those events directly, rather than finding other ways to make sure the reader knows about them. But should you? One reason beginner-writers often shy away from working with several points-of-view because how on earth do you decide, when anything is possible?

How to work it all out. If you want to get maximum creative value out of your new PoV, you're going to have to go back to the basics of how the story is built. Try a planning grid, with rows for chapters. The first column is Anna's PoV - i.e. the current version. Jot a note for each scene which is "onstage" at the moment, so you have the outline of the current version from beginning to end. Column two and three are for Bill's and Con's points-of-view- or whoever else is a possible viewpoint character. Make a note of any "off-stage" scenes which currently happen parallel to the "on-stage" scenes, but which Bill or Con are present for. I would then make a fourth column, which is, if you see what I mean, the "new on-stage" version: a first try at laying out the scenes which will now make up the novel. As I jot the scenes into their right places, I'd put little A or B or C in a circle by each one, to show what I think I'll be doing in terms of which PoV for which bit. Do it all in pencil, and be prepared for a LOT of rubbing out while you work it out, not least because you might want to write ...

...totally new bits of story. As you roll around in all this material, it may well be that you realise that things are shifting, and you can or must write new events. If so, don't sigh: it's a really good sign. Huge-scale carpentering on an existing draft always carries a certain risk that you're creating Frankennovel, but finding your creative (as opposed to editorial) imagination waking up proves that the novel is being re-born as a creative whole. (Apologies to whoever first coined "Frankennovel", because I can't remember, but I do so love the concept and have created at least one myself, so please out yourself in the comments if you want to.).

Remember that the narrative voice may, even should, change. As you'll know if you've got your head round Psychic Distance, a different PoV may also affect the narrative voice. The closer-in we are to that character's consciousness, the more the scene and how it's narrated is coloured and shaped by that character's personality. So changing PoV from Ann to Bill doesn't only change the mechanics of what you show us, now we're in Bill's head, and give you the chance to withhold or supply information, it also may also change the words you use in both Showing and Telling us what happens. If that shift from Ann's voice-and-point-of-view to Bill's isn't coming naturally - often it doesn't - there are various things which help.

Copy-type the new PoV sections, don't cut-and-paste. This is why and, I'd say, it's crucial if you want to make sure you don't give birth to Frankennovel.

Make sure Bill and Con are really developed characters : perhaps review their dialogue, as a way of clarifying their voices now you need them to colour the narrative as well.

Write some of Bill's in first person, maximising the differences quite cold-bloodedly , in some of the ways I suggest in that post, then flip it back into third.

First-draft a short story in Bill or Con's voice-and-point-of-view. Sometimes it's easier to develop this kind of thing independently of the practical demands of the plot you already have.

And that's it, I think. Oh, and Happy New Year!

December 28, 2017

Happy New Writing Year!

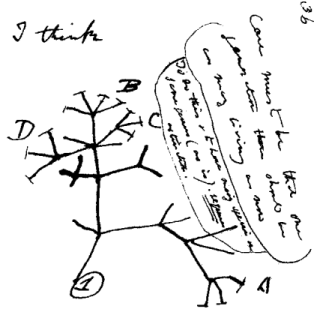

I don't believe in giving things up for the New Year. True, the days are getting longer, and just this morning on the Essex-Suffolk border the sun is sparkling, but here in the northern hemisphere there's an awful lot of dark-and-cold about. So it's asking to fail, it seems to me, to choose to think in terms of denial and deprivation in matters where you don't have to. Instead, here are some Trees of Life, from the Museo de Arte Popular, in Mexico City.

In a similar spirit, this post, from the same season a few years back, is about forgiving oneself for failure, but this year, by way of wishing my dear blog-readers all writerly health and happiness in 2018, I've been looking ahead. What might you (I) choose to do and think about, to make your (my) writing life richer, happier, easier, more productive and, as a happy by-product, perhaps more successful in worldly terms?

Walk up a hill every day. You may not care about your bodily health, but the brain's blood vessels fur up as easily as the body's do. What's more, if you pop a plot problem instead of a phone in your pocket, you're likely to come home with the problem solved.

Practice staying inside your head, because that's where the writing is. In this clamorous world, it takes more forethought, but it can be done. Not least, on that walk.

Allow yourself to take your writing seriously. Writing is the thing that we love doing more than anything else, but the ratio of effort to material reward is so very unpromising, it's easy to feel in this post-Protestant, capitalist world that it's self-indulgent. You may have got over the idea that you "ought" to give up altogether, but your Inner Calvinist may still be very good at self-sabotage, in his/her own guise or dressed up as some other helpful but misguided soul.

Allow yourself to take the tools of your trade seriously, as part of taking your writing seriously, from the notebooks that suit you best to the software (such as Scrivener) which doesn't get in the way of your writing and the chair that doesn't wreck your back. This is one of the wisest ideas in Carol Lloyd's very wise book Creating a Life Worth Living. Of course your budgets of space, time and money are limited, but painters hunt out and pay for the quality of paint they need even if it does mean forgoing some drinks, and dancers know they must have space to practice - but maybe that church has a room upstairs with a decent floor, in return for some help with the cr��che. Similarly, the second-hand office furniture shop might let you try a chair for a few days with the promise of a full refund if it doesn't help, and when it comes to notebooks, it may be too late (or too early) for your Christmas list, but when's your birthday?

Don't forget to be kind to your writerly self. Writing may be hard in terms of work, and in terms of working with difficult stuff, but that's a reason to be less, not more hair-shirt-ish in other matters.

Write a very short story or a poem every day. Ring-fence the time as you would the time for having a shower or cooking the tea because both are necessary for your health. Just do it. The result doesn't have to be good, or long, or experimental, or developmental or have any other obvious virtue: it just has to be there. The strange thing is that if you keep on writing these little things on which nothing is riding, they will begin to acquire those virtues - or even some virtue that you didn't even know you sought to acquire. As Ray Bradbury says in Zen and the Art of writing: "Quantity gives experience. From experience alone can quality come."

Take a poetry course if you're a prose writer. Here's why. If you're a poet, take a prose course: not necessarily fiction, but certainly one involving storytelling and human voices.

But don't forget that, since The Itch is always about ideas and possibilities - tools to try, not rules to follow - I'm assuming that you've been reading these (and perhaps this New Year's list of things to try) and applying your Accept, Adapt, Ignore scanner. And if you have anything you're planning to take up, not give up, in the New Year, and are able to add it to the comments, you might be doing some other Itch-reader a tremendous favour, so feel free to do chip in.

And with that, I shall wish all of you

HAPPY NEW YEAR & HAPPY WRITING

AND HOPE TO SEE YOU IN 2018

November 27, 2017

10 Reasons for a Prose Writer to do a Poetry Course

Every now and again someone asks me not, "How can I write this story better?" - to which I have a whole Tool-kit-full answers, obviously - but "How can I become a better writer?" Assuming that my interlocutor is already meeting the absolute pre-condition of being a better writer, which is reading more, and more widely, my next suggestion is probably to take a poetry course. That's not because I think everyone should write lyrically - although that is a very honourable goal - but because I think it can help any writer to develop. As Ray Bradbury puts it in Zen in The Art of Writing,

Poetry is good because it flexes muscles you don���t often use enough. Poetry keeps you aware of your nose, your eye, your tongue, your hand. And, above all, poetry is compacted metaphor or simile.

On Monday 4th December our Words Away Salon welcomes the award-winning poet Maura Dooley, who is also Professor of Creative Writing at Goldsmiths, to explore how thinking a poet can help your fiction and creative non-fiction. If you can make it to the Tea House Theatre I can guarantee a fascinating, enriching and thought-provoking evening (plus cake and wine and tea and other writers). Meanwhile, here are a few of my own thoughts:

1) Sound is the most fundamental quality a word possesses: it affects the listener, and by extension the reader, even when we don't understand the meaning of a word. (Think IKEA names, and the Bouba-Kiki effect). The linguisticians call this aspect of language prosody, and poets learn to work with the sounds of the consonants and vowels, the patterns of weight and stress, the rise and fall of intonation, the echoes, links and contrasts of sounds, as they join up to make phrases and sentences. One way to give your prose more substance and intensity - or lightness and delicacy - or energy and attack - is to learn to work with its sounds.

2) A poem takes you on a journey, as Ruth Padel explores in her book about reading (and therefore writing) poetry. But it doesn't need a story, so you are free to play with everything else that language does, without the contraint of having to make it all hitch up together with the logic of a plot built from causes and consequences.

3) Poetry can play fast and loose with conventional grammar, syntax and punctuation, if it helps to create the effect in the reader that the poet is after. Again, if you're not trying to convey a chain of storytelling logic, and can assume that the reader may to and fro inside the poem, then you can work to explore and develop your skills at bending and messing with the conventions, at the edges of what's possible before all sense breaks down.

4) Poets work constantly with the halo of connotation of a word, as well as what it denotes: think about all the other meanings, implications, connections and echoes that a word like apple has: not just rhymes like dapple and slant-rhymes like triple or bobble, but everything from Adam and Eve to computers, from Disney and round pink cheeks to Cockney stairs and the Beatles. That's another way to add substance: richness, layers, echoes, reflections, implications, references ...

5) Poetry works with metaphor and simile to make the invisible and intangible, the abstract and metaphysical, concrete. And it does so, as Bradbury says, in the most dense and economical way, for the greatest possible emotional and pyschological power.

6) Poetry is (usually) shorter, every word is highly visible, and has to work extra hard. A phrase or image that doesn't really fit, is surplus to requirements, is a clich��, or merely dully off-the-peg becomes blindingly obvious. You don't need me to tell you why that's good practice for prose-writers.

7) Poets' techniques are perfect for working with the senses, and close-in psychic distances. Poetry claims the right to depart from the clear chains of meanings - sentences - that prose is normally built of, while still having something to say. When you want to evoke the stream (or more often tumble) of immediate consciousness and experience in prose, while still moving the story on, you want some of that freedom too.

8) Poets talk not about clich��s, or second-hand language, but received language: phrases and ideas that have originated with someone else. That gets us away from the literary-snobbish (and unachievable) goal of every word being "original", towards the much better and more interesting idea that any word or phrase might have a place in your writing: it's just a case of recognising its pre-existingness, and using it for good.

9) Poetry rewards - and often requires - close reading, which is an important habit for a writer of any kind to develop. In reading prose, it's very easy not to open more of your mind than is required to make sense of the story, and often only poetry presents us with the "desirable difficulty" by which we really get inside a piece of writing.

10) Writing poetry is fun. There's a playfulness about messing around with noises and pictures, with not having to worry (for now) if it makes literal sense, with being able to trust that the reader is in the game with you - which it's very easy to lose touch with as you grapple with the mechanics of plot and story. And finishing and revising a poem is quicker than finishing a novel; you may spend a lot longer on each phrase, but it still won't be as long before you can sit back and say "I made that.' And finally, someone really has to love you before they'll read your novel in manuscript, but poets swap poems and give readings all the time: for something that is often thought to be an intensely private experience, poetry is an amazingly sociable creative practice.

If you're intrigued by these few thoughts, why not come down to our Words Away Salon at the Tea House Theatre on Monday 4th December, and join Maura Dooley, Kellie, me and a cake-eating, wine-drinking audience of fellow writers, to think more?

November 8, 2017

"Cut All the Adjectives & Adverbs". Why it's Nonsense, and When it Isn't

Cut all the adjectives & adverbs" is right up there with "Show, don't Tell", as one of the first "rules" that new writers get told, and for similar reasons. And although it's perhaps responsible for more bland, threadbare writing than almost any other phenomenon except the ghost of Hemingway, it's not entirely nonsense either, any more than Hemingway is.

The truth is, writing would be impossible if we couldn't use adjectives, adverbs and adverbial and adjectival phrases. But although you'll never get me to say that you "should" cut them, there is a whiff of good writerly sense somewhere at the root of it. It's not necessarily a bad idea to take a long, hard look at the adjectives of quality and adverbs of manner in your drafts, and seeing if the effect they're trying for would be better achieved another way.

Let's start with the basics, for which I must thank David Crystal's entirely brilliant books Rediscover Grammar, which is about how language works, and Making Sense of Grammar, about how to use how it works to your advantage. Whether you're old enough to have had the old grammar beaten into you, the generation (like me) who learnt little grammar except, unhelpfully, via foreign or ancient languages, or the younger generation who are gaining (or suffering) from the pendulum swinging the other way again but with a new vocabulary of terms, I can't recommend Crystal's books highly enough.

AN ADJECTIVE is a word which changes or adds to the meaning of a noun: red, hopeless, French, happier, contemplative, fancy, your, which, quick, sad. Some words function as an adjective when they have another function in other contexts - the town clock (noun); an early train (adverb); a calculating man (-ing form of a verb, a.k.a present participle); the alleged crime (-ed form of a verb, a.k.a. past participle). And an "adjectival phrase" may join several words to describe a single thing: that house is larger than mine; do take the chair by the table; the dress I bought yesterday.

But notice that your mistaken writing buddy is only talking about one small sector of the class of adjectives: adjectives of quality, which answer the question What kind?: square (shape), huge (size), red (colour), scruffy (condition), quick (behaviour), sad (feeling). They're not talking about adjectives like many (adj. of quantity), six (adj. of number), French (proper adj.), this (demonstrative adj.), which (interrogative adj.), mine (possesive adj.)

CUT ADJECTIVES (of quality)

- when they're Telly (informing, summarising), when you'd be better off Showing (evoking, dramatising). "Don't just tell us that Adam is angry," says your writing buddy, "Show us his red face, clenching hands and how he whispers, 'I hate you'." (Red and clenching are adjectives, of course.) The human imagination deals in concrete things, so if your game is to make the reader's mind evoke a real sense of Adam then feeding some of those concrete things into our imagination will always make things more vivid in there. Similarly a beautiful and no doubt expensive vase isn't going to do much to evoke a real, physical thing, and we won't feel much shock when it's hurled into the fire.

- when they contribute to overwriting: Overwriting is an effect that can have many causes, but one cause is piling on the adjectives, so that no person, place or object comes un-decorated with detail, till the passage is as indigestible as an over-rich, over-long meal.

- when this is not something that needs more explaining or describing. If we know the champagne is being poured, do we need telling that it's fizzy and straw-coloured? Does it matter that the bus is big and red and smelly? Here? Now? Will plot, story, or the crucial kind of vividness which is about getting the reader to buy into the world of your story, suffer without it? In other words, if you're embarking on an explain-ectomy, the adjectives will probably be some of the first words to go.

INTERROGATE ADJECTIVES

- should you not cut but change them? The fate of that elegant and no doubt expensive vase will be much more vivid if it was evoked as a slim, silver vase studded with pearls before you hurled it on the fire.

- are they right for voice, point-of-view and psychic distance? This is what's really going on in the decision about Here? Now? Through whose eyes are you showing us this thing that might (or might not) need extra evocation? Would they think that extra stuff? At that moment? Might they not know, or not specially notice, that it's a slim silver vase studded with pearls, but certainly experience it as beautiful? Are they someone who would guess it was expensive? If so, you do want a summarising sort of adjective like that. Or are you sliding deliberately a little away from your down-to-earth, unworldly viewpoint character who wouldn't notice anything except that it holds flowers, and instead granting your narrator the storyteller's right to evoke the slim, sliver, pearl-studded vase, because you want the reader to experience it that way?

- are they proportionate to the person or thing's importance in the story? Subject to the voice-and-point-of-view judgement, if a narrative gives a lot of space to evoking a particular, individual example of a bus or shopkeeper or house, there's an implicit signal to the reader that it's important, and we'll try to read and remember it as such. Is it that important?

- Is this the moment to take time over description? Is Anne sitting in Beth's bedroom, trying to read the photographs on the mantelpiece so as to work out if Beth's telling the truth that they have the same mother? Or are we in the middle of a car-chase? Or is the storyteller taking us a little away from the moment, to show us the setting while the story's quiet, ready for the nightmare later?

- are they consistent with the style and voice of the narrative? You can write as richly or as sparely as you like, you can evoke all sorts of small, passing details that add up to a wonderful tapestry of your story's world. But once your reader has settled into the style and quality of the narrative, inconsistencies where things are suddenly less, or more, densely descriptive, will jar, make the reader feel restless and un-engaged.

- do they make the sentence monotonous? If every noun comes with a preceding adjective, the sentence gets very ploddy: The thin woman had a narrow face with a low forehead and sandy hair. She wore a red hat, a brown scarf,* and furry gloves on her thin hands. But the cure may not be to write: The woman had a face with a forehead and hair, a hat, a scarf, and gloves on her hands. Instead, exploit the fact that a) English sentences can hold adjectives in many different ways: b) now's your chance to bring in a bit of character-in-action: The woman was thin, with a narrow face: her forehead was low, and her thin, fur-gloved hands poked at her sandy hair, as if she knew its colour clashed with a hat that was as red as a poppy. To practice this kind of reworking, when a sentence forms itself in your mind as you wait for a bus, see how many ways you can re-jig it, as I did with this one, and how that changes its effect.

KEEP OR ADD ADJECTIVES

- when Showing takes too long. Sometimes, as a storyteller, you just need us to know the fact that Adam was angry last week, or the vase was elegant, so you can get to the meat of the scene.

- when Showing is merely "signalling": using gestures for emotion which have become stereotyped, rather as Victorian engravings show shock by the lady holding her hands up: wide eyes for amazement, shaking hands for fear. As with any tired, second-hand idea, language or image, the reader just picks up the signal as information, and moves on without actually feeling anything. You might be better off just saying "He was amazed", and then moving on to what that amazement makes him do next.

- when the scene or person is bland and flat: You know it makes sense: I went into the room and found a man is not as vivid as I stormed into the vast room and found a tiny man. Or, probably better still: I stormed in, and found it to be a room so vast that the tiny man in the corner was almost invisible.

- when the voice or PoV demand it: do we need to know swiftly how a character experiences something - that the man is beautiful and expensive, say - without you spending ages on the particular detail? Adjectives like that might also be right if your viewpoint character is someone who just wouldn't think in terms of the man's cheekbones, eyes and Italian silk-mohair suit?

AN ADVERB is a word which changes or adds to the meaning of a verb: soon, fast, frankly, well, tomorrow, quite, disgustedly, anxiously, quickly, sadly. Some words which are not obviously adverbs can be put together to form an "adverbial", which is a phrase doing the job of modifying a verb: never, ever try Morris Dancing; for a week I lived upstairs; they went in the car.

Notice that the adverbs they tell you to cut are always adverbs of manner, which answer the single question How?. Most end with -ly - sadly, quickly, hilariously, effervescently, fortunately - which is why some new writers who are anxious about them do a search for words ending in -ly. But there are other endings: fast, clockwise, sideways, widdershins, Soviet-style. The tutor telling you to cut all adverbs is never talking about adverbs like here (adv. of place), soon (adv. of time), extremely (adv. of degree), always (adv. of frequency).

CUT ADVERBS (of manner, chiefly)

- when they're Telly: in she ran quickly, quickness is built into the idea of run, unless you specify otherwise. Same with but consider thoughtfully; he crawled slowly; I cuddled lovingly

- when they contribute to overwriting: as with adjectives, any given adverb can be an excellent word in itself, but if you have too many of them too close together, it's like wearing three diamond necklaces, and then earrings so long they get tangled too... Pick the best diamond, and let it shine clear.

- when this is not something that needs more explaining or describing: The bubbles filled the glass frothily, for example, or "Will you put the dog out?" she said enquiringly: the latter would probably be better off with just asked. Or enquired, of course: often the unwanted adverb is a clue to a better verb.

INTERROGATE ADVERBS

- could verb+adverb be replaced with a better verb? One that doesn't need the help of an adverb? She ran fast is rarely going to be as vivid as showing us that she raced, she scuttled, she galloped, she pelted. And as writerly yoga, next time you're waiting for a bus, think of a standard verb+adverb, and see how many ways you say the same thing just with a well-chosen verb. For example, take he sat down. How about: He subsided... He collapsed... He perched... . (n.b. down is acting as an adverb here, but not an adverb of manner.)

- are they right for the voice, point-of-view and psychic distance? Again, absolutely any decision about which words to use needs to be subject to these three fundamental aspects of the piece, so if you haven't explored these issues, do follow the links further up.

- are they consistent with the style and voice of the narrative? Again, it's the same as with adjectives: the richness or sparingness of your narrative is part of its fundamental, individual nature and voice - so make sure it's consistent.

- do they make the sentence monotonous? The cure for a ploddy sentence like She walked quickly down the road, breathing noisily as she trod carelessly over the crookedly-placed paving stones, may not be, She walked down the road breathing as she trod over the paving stones. Exploit the fact that adverbs can go in all sorts of places in a sentence, can point you towards a more effective adverbial phrase, or morph into a different part of speech, to do the same job in a re-jigged sentence with a better structure and rhythm. How about, "Quickly, she set off down the road, careless about how she trod over the crooked paving stones.

KEEP OR ADD ADVERBS

- when Showing is too fancy. For example, rather than digging out different verbs, you might choose to cover the ground in evoking a long journey with something like this: They sailed slowly, they sailed fast, they sailed carefully and fearfully, but always with hope.

- to help us to "hear" how something is said. In dialogue, sometimes an adverb is a better choice than a fancy speech-tag (more on speech-tags here). "I know you took the money," Bella said quietly, is fine to convey the volume of the speech, if whispered or murmured would be too much or the wrong effect. But do you want us to "hear" how another character might experience Bella's tone? "I know you took the money," she said thoughtfully, might do that better, and Gently, she said, "I know you took the money." would also be more precise, but to a different experience.

- when the voice or PoV demand it: as with adjectives, a well-chosen adverb may be the most streamlined way to evoke the way a character experiences a place, without you digging up a funky verb that might not be right for them, or ladling in adjectives and descriptions simply draw too much attention to themselves.

A last thought: as with all the tools in your writerly (note: a -ly word, but not an adverb) tool-kit, it will help enormously if you a) read voraciously, sometimes immersively by just soaking in good writing, and sometimes analytically, pausing to think about how the adverbs and adjectives are working in this particular piece - and whether they're working well or badly. b) do writerly yoga of the sort I've suggested above, flexing and bending not just your sentence structures, but your vocabulary and all the different jobs any given word can do.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*note the need for the Oxford comma, to make it clear she's not wearing a scarf on her hands, as well as gloves.

October 10, 2017

Basing Your Fiction on Real People? Can "Real" and "Fiction" live in the same book?

At October's Words Away Salon next Monday, the 16th, Kellie and I are delighted to be hosting Jill Dawson. We'll be talking about writing fiction based on real characters - recent or ancient. Jill is a poet and novelist, and a highly-regarded mentor of writers, and her most recent novel is The Crime Writer. That's about Patricia Highsmith, but she's also written The Great Lover, about Rupert Brooke, and Fred and Edie, based on a famous Victorian murder.

So we thought she'd be the perfect person to start us off talking about this fascinating but very challenging kind of fiction, and in thinking about our conversation next week, I came across this post, from a few years ago. I've tweaked it a bit, and I hope that it's useful, whether or not you can join us on Monday for tea, wine, cake, beer, and lots of excellent writerly conversation. Just be warned - we do sometimes sell out before the night, so to be sure of a place, book ahead.

***

I've explored What Counts as Historical Fiction? before, but when you're contemplating a writing about a world that has or had real people in it, there's another question. Fiction is often a way of exploring real worlds and lives, but what makes a narrative about a real historical character a novel, and not a biography?

A biography or autobiography is a whole life narrated with the techniques and boundaries of the historian: provable facts assembled; the record (which is never the same thing as the facts) interrogated for reliability; gaps of time or space acknowledged; inference and speculation labelled as such. But the emergence of creative non-fiction has changed things in life-writing: it uses the techniques that fiction has evolved to evoke in the reader the characters' consciousness and experience: dialogue, imaginative re-creation, non-linear structures, different points of view and psychic distances, etc. Added to the real interest of this liminal territory is the unarguable fact that it's much easier to sell a story through the industry chain from agent to book festival, if it has a "non-fiction hook". So novels about real historical characters are big business: they are sold as fiction, and yet much is made of how faithful they are to "the facts". So confused are we all that in the USA Schindler's Ark - titled over there Schindler's List - was sold as a "non-fiction novel".

But though the gap between a novel based on a real life, and a real life told novelistically, has narrowed, it is still there. Memoirs claim truth because the writer is narrating the authentic, historical truth of his or her own experience, through his or her own consciousness. It doesn't totally negate that claim if events or people are rearranged or conflated, if dialogue is imaginatively re-created, if only bits of the life are told, if gaps are filled with imagination by someone who was there. The story has the unarguable claim to evoking the writer's truth: a lovely example is Alexandra Fuller's Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight .

But what if your life-writing is about someone else's life? Your truth-claims can't simply be the unarguable, "This is what I experienced". It seems to me that it's still Life Writing if you, the writer, have direct access to that life. In your memoir of a parent or friend, your evocation is still anchored in your own experience of the person whose story this is: the truth-claims of the narrative don't have to stretch too far. The fact that other writers might disagree - as many do with Edmund Gosse's portrait of his father , for example - doesn't (or shouldn't) negate your right to your truth.

A different kind of life-writing links your life with your discovery of a long-gone consciousness: "This is what I experienced of that life". The first master of this is Richard Holmes; a favourite example of mine is Janet Malcolm's Reading Chekhov. Other than Holmes's way, once you don't have that direct connection and can only experience your character through biographies or other records, you can't say more than "This is what others experienced".

It seems to me that you then have a choice. If you want to make the truth-claim that your narrative is a faithful representation of the life, then the proportion of imagining and changing you can do is fairly small: the narrative logic of cause and effect is pretty much prescribed for you. It's still worth doing, particularly if you exploit the form: Ruth Padel's Darwin: a Life in Poems is definitely life-writing, not fiction, but she has the freedom of the poet to break out of the logical necessities of the already-documented life.

But if you want to imagine and shape things beyond what a biographer would allow themselves - re-create minds, write direct dialogue, evoke emotion and sensation, shape satisfying stories "as if" we were there - then you're moving into the territory of biographical or historical fiction. From Wolf Hall to Rose Tremain's The Darkness of Wallis Simpson , some fo the best writers and writing have centred fiction on real historical figures. And it doesn't have to be Royals: Jill Dawson's Fred and Edie is about Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywater: two real Victorians convicted - controversially in her case - of murder. It's also the case on which F Tennyson Jesse's 1925 novel A Pin to See the Peepshow was fairly obviously based, but Dawson, with the greater distance but also perhaps the need to make clearer the connection to a case now forgotten, didn't veil the story with different names. Then there's Julian Barnes' Arthur and George , about a miscarriage of justice case involving Conan Doyle. The challenge of growing fiction out of well-known figures and events is different from the business of plucking people and events from obscurity.

The thing is, of course, that when you do decide that this will be a novel, suddenly you have much greater freedom. You can call it a novel, make your own rules about what you must stick to and what you can invent, and get going. The reader won't necessarily consciously realise that you've made yourself a rule-book, though many an "author's note" or "historical notes" at the end are implicitly just that. But having a rule-book will mean that there's a consistency about the your novel's relationship to the record which I think readers sense, even if they don't analyse it.

But do be free with your rules. It's the worst of both worlds to claim the fictioneer's freedom and then not take it, whether from the sterilising fear of "getting it wrong", or from a lazy reluctance to go to the bother of imagining when you could just re-write what's in the history books. As Rose Tremain says, facts are inert data until they've lost their real-world tethers and disolved into your imagination along with everything else. An historical novel about a real person must inhabit the character as fully, as imaginatively, and with as much freedom to invent, as if they weren't real. If you can't bring yourself to write as if your real historical character never existed - or if your real desire is to build an historical argument about the innocence of Richard III or the guilt of Edith Cavell - then you need to stop calling it a novel, and admit it's a history book. Or a biography.

October 4, 2017

Is Your Writing Out on Submission? Welcome to Hell

So you (or your agent) has sent your work out to ... someone. A magazine, a competition, a publisher, a broadcaster, a film company, an agent you hope for, an author whose quote you desperately want for the cover, even a mentor or editor you've hired yourself. You are now officially in the condition known as Waiting To Hear.

Welcome to a minor and largely unacknowledged room in Writer's Hell. Or rather, two rooms. You may have short, relatively easy time in Limbo, when you genuinely know you won't hear: the stretch before the competition deadline or the closure of the submissions window; the months before the date they've said the competition result will be announced; the three Frankfurt-sodden weeks when your agent will definitely not be reading it, or she knows that editors won't be.

And then there's the true Purgatory that starts at one minute past 9am (your time-zone may vary) on the day you can start hoping (however unrealistically) to hear. Particularly excruciating side-chapels of Purgatory include the one for those competitions which have a longlist and a shortlist, and the one where the editor says she loves it, and wants to take it to acquisitions.

A writer I know refuses to talk about "submissions" and "rejections", because we should consider ourselves equals in this transaction: we offer work, and the publisher/agent/broadcasters accept or decline it, he says. He's quite right, but there's no denying that it's hard not to feel abject when you're in Purgatory. You may hope that they'll want you, but unarguably they don't need you, and you do need them.

What's more, after all these months or years as onlie begetter and sole ruler of your work, you have unavoidably stapled your heart, or even (unwisely) your mortgage, to those pages ... but there's nothing, now, you can do to alter the outcome. And if you write poetry or for magazines, or you are a serial writer of novels, or have made the (usually wise) decision to submit your book widely, you can live in the Limbo-Purgatory circle for a very long time, or even permanently.

SO HOW DO YOU SURVIVE IN LIMBO?

Start something new. I cannot emphasise this enough. If you allow the conviction to grow that your entire writing future rests on this story or book or commission, you will go mad. Besides, it doesn't: you can write something else. Really you can, and you must. Rejections are horrible, but they're a whole lot horribler if you let them spell the end of the dream you've been working so hard to make real: that you can be a writer. Plus, if you do find yourself talking to an editor or agent, they will certainly want to know what you've got in the pipeline.

Don't pin all your hopes on one submission. Send it out elsewhere. Generally speaking, ignore those who say they don't take simultaneous submissions, which give editors and agents more control over your work than they deserve when they haven't paid for it - but be prepared for the consequences and consider what you'll do in the various possible combinations of acceptance and rejection.

Send out some other stuff, somewhere else. It might seem to make it worse, but actually it dilutes the agony: when the first rejection comes in, you'll still have a different something out in different places. By the time those have come flumping back into your inbox, you'll have another batch out somewhere. It keeps the hope going.

Do practical things which will be useful if your work is published - but only realistic ones, that you won't regret if it isn't. Buy your domain name and bag Twitter and other accounts to match; set up a blog if you have a topic, ideally relevant to the book, which you enjoy and can sustain (but not under your own name if it's chronicling rejections); hunt down a good writers' circle or forum, if you haven't got one already; start going to readings, events and festivals in your form and genre; start following people and making connections on social media ditto.

Cut yourself some slack. Accept that your shitty first draft will be shittier than usual, and make notes as you go about what you're not stopping to put right at the moment. Switch to research if you're really distracted and stuck. Switch to intensive reading of relevant creative writing if you're even stucker. If you really can't do stuff for your own writing - or you realise it's only the must-write demon insisting that you should - then concentrate on nourishing and re-fuelling reading. Oh, and this is almost certainly not the moment to go on a strict diet or give up smoking, or do anything else hair-shirt-ish.

Recognise when self-consciousness is sabotaging you. All too often, a piece of your writing-brain scampers off to read the editor's/agent's/judge's mind, and badgers the rest of your brain to write what would please those judges. Don't let it - partly because it can't read those minds, and partly because self-consciousness is death to creativity.

Don't be sucked into fiddling instead of real writing or real revising and editing. This is why.

Recognise when the doubt-demons are sabotaging you. That self-consciousness evolves horribly easily into an Inner Critic. A simple-minded, primitive Critic may clearly tell you that your writing is rubbish and you're a fool who's too big for their boots, and everyone at the publishers' or competition's office is laughing at you. The first may be true, but you're unlikely to be told that either way. The rest are not. The even more evolved Inner Critic learns to don disguises, however, so keep an eye out for those devilish eyes glinting through the mask.

Take care to nourish and refuel your creative self: Enjoy the fact that you are no longer grabbing every minute to hammer away at a manuscript. Now is the time to sort out the garage or the attic if you're the kind of person who once they've knuckled down will get real satisfaction from a good job well done. The rest of us bake cakes, take photographs, write poems (and poets try writing stories), go for long walks in nice places, and catch up with friends we trust not to ask (too often) about how the submissions are going. Just don't get fed up with yourself if nothing is quite as satisfying: Waiting To Hear is rather like having a bit-of-a-headache for three months.

Recognise your procrastination for what it is, but explore why you're procrastinating. It might be the agony of Waiting To Hear, but it might not be - and the causes do make a difference to what you do to overcome or side-step it.

Remember we all go through it. This article is comforting, but on the whole writers don't admit they've got things out there because a) they'd rather not set themselves up for having to talk later about books that were rejected. b) Facebook syndrome: we are all selective about what parts of our lives we make public c) we get fed up with being asked, since there's actually nothing to say when kind people say "any news?"; non-writers in particular may innocently say things which are at best tactless.

Find companions in misery. This is when your closed, private circle of trusted fellow-writers, your secret Facebook group or your old muckers from the Masters come into their own. They understand both the agony and the context, and they've been there themselves, or will be soon. The first thing I do, when I've sent something off, is to collapse into the private forum where all my dearest and oldest writing friends hang out, pour myself a very large virtual drink, and catch up with who else is suffering. They are also the friends who will say very lovingly, when I'm being hysterically furious or crushed about something else, that it's my Waiting-to-Hear condition which is making it hard to get my balance again.

Recognise when you really are not OK, shift into self-care mode, and if that doesn't work, get professional help.

AND HOW DO YOU SURVIVE TRUE PURGATORY?

Try not to spend your life trying to read the entrails of how long it takes to hear, or what the first few say when they do respond, or what you read elsewhere about the state of the market, or what another writer says about their success or failure. Obviously, if a website gives a deadline or a likely response time (and these days many do), it's perfectly fair, a little while after that time, to email and ask if they have an answer yet. There's nothing to stop you doing that even if the website says nothing, but you may not get an answer. Other than that, really, truly, the only thing you can tell from not having heard yet is that you haven't heard yet - and the only answer to "how long will it take?" is however long it takes.

Know that being slow to get answers is incredibly common - and ever more so. Editors at magazines have to do more and more work with less and less help; at the literary end they have to spend swathes of time on grant applications, and almost certainly have a day job too; a book, to be acquired, has to promise with increasing certainty to sell in much larger numbers, and that certainty has to be based on all sorts of figures and judgements. And now that a decision to acquire has to go through many hands and committees, and there's always someone off sick or away, the response to you will arrive at the speed of the slowest in-box.

Lean on your agent but remember they are not your best friend or your counsellor. Your agent's job is to be your interface with the industry, and that includes explaining how things work, when you might hear, and what the next stage is. Don't feel ashamed of asking apparently silly or ignorant questions: there are fundamental ways in which we are not part of the industry, and all new writers, and many established ones, simply can't have learnt all this stuff. Having said that, your agent has a job to do, and it's not to answer daily furious or miserable or just fussing emails from you because you need to let off steam.

Allow yourself to be miserable when you do receive a rejection someone declines to buy your work. It not only hurts to have someone say "I didn't like it enough", but you've had your hope taken away, however temporarily, and that is a bereavement. The only way round grief is through it. And be prepared for a temporary flare-up of self-consciousness, Inner-Criticism, self-sabotage and procrastination.

Try not to feel that you'll be letting others down if the work doesn't sell, whether it's your agent or your writing tutor or your family. It's human, but that way madness (or at least an unhealthy emotional dependence on your agent) lies. Agents are gamblers, and they don't always win. That's not your fault, any more than it's your fault if someone looks at your racehorse, reads up the form, and chooses puts money on it. Tutors are the same: we are thrilled when our students succeed, we are very sad when they don't, and as part of our reflective practice we worry about we could have done better - but at heart we know that it's just how it goes. And family? I think the only thing you can do is make sure they know something about the realities of how it actually works, managing their expectations as well as your own. To which end:

Understand more about the context of acceptance and rejection. I know that sometimes you'd rather not know - but this classic post by a publisher is very funny, but also very informative. The good news is, as long as your manuscript is better than this - "Author can write passable paragraphs, and has a sufficiently functional plot that readers would notice if you shuffled the chapters into a different order. However, the story and the manner of its telling are alike hackneyed, dull, and pointless" - then it's already better than 75% of the slushpile.

Find out more about the acquisitions process. Many an aspiring writer, having slogged and studied and bagged a good agent, is startled and depressed to discover that it's only the beginning. But the acquisitions process is also worth thinking about when you're looking for an agent, since they earn their living by understanding how editors think ... This post, over at the always-excellent Nicola Morgan's blog Help! I Need a Publisher, sets it all out very clearly, and this one is good on how magazine editors operate.

Get practical about your idea that if this works, you might be able to write for a living. What is this Hell telling you about how much you care - or don't - about the business of finding readers? If having work out there makes you realise that you want to do a Masters, or start a magazine for others' writing, or build a writing hut, or turn to self-publishing, then go for it. But, I can't emphasise enough: don't commit to anything, financial or otherwise, which you will regret having committed to if this work is rejected. And don't let your legitimate hopes blind you to the realistic possibilities, because there are all sorts of factors governing your work's fate which are nothing to do with its qualities, and everything to do with things you can't know about.

Finally, don't be ashamed to recognise that this is not what you want to do with your life. I know more than one person who worked and slogged and got a novel out there and ... in the process of submissions, realised that, actually, the time-and-emotion-suck wasn't worth it, and didn't serve their happiness, and they stopped. That's a perfectly honourable decision, which you shouldn't allow pride, or other people having nailed their colours to your mast, to stop you making.

But, if you do decide to start, or carry on, submitting:

Bon Courage!

September 10, 2017

All the Posts I Mentioned at the York Festival of Writing 2017

I'm just back from the 2017 York Festival of Writing. If you don't know what I'm on about, this is a selection of posts from former years, and if you do, you'll know that the weekend was, as ever, packed with workshops, one-to-ones, lunches, dinners, breakfasts (yes, everyone talks writing even over the cornflakes and sausages, and through the hangover), agents, publishers, authors, writers and ducks.

And, as ever, I mentioned various blog posts at various times to various people, as a way of expanding on whatever we were talking about. This, to the best of my ability, are the posts I mentioned, but if you remember another one, do say so in the comments, and I'll do my best to dig it up.

If you're interested in the 6-week online course Self-Editing Your Novel, which I co-teach with Debi Alper, there are more details in that link. And those who are in reach of London might be interested in the Words Away monthly salon for writers, which I co-host with writer Kellie Jackson, at the Tea House Theatre in Vauxhall. It's easy to get to, very informal, a lot of fun in a particularly quirky and delightful venue, and there are more details here: Words Away Salons. Writers who were in my session on Writing From Life might be particularly interested in our salon on Monday 16th October, when Jill Dawson, author of The Crime Writer, which is about Patricia Highsmith, and many others, will be joining us to talk about writing fiction based on real people.

And before we start, do note that wherever you are on the blog, you can always get to the Itch of Writing Tool-Kit: just click up there in the right-hand corner. Most of the posts below can also be found there, along with lots of others.

BASICS

PSYCHIC DISTANCE: what it is and how to use it : also called narrative distance; an extraordinarily useful way of thinking, which is responsible for more lightbulb moments in my students than everything else put together.

SHOWING AND TELLING: the basics : how to use both to make your story do everything you want it to do.

HOW SHOWING AND TELLING CO-OPERATE : why you need both, and how they work together

HOW TO TELL, AND STILL SHOW : how to get on with the story without sacrificing vividness

PAST AND PRESENT TENSE : the pros and cons of both : the different issues that arise with first and third person for each tense, and why the new creative writing orthodoxy is wrong.

STORYTELLING

PLOT vs. STORY : what's the difference and why does that mean for your writing?

THE BASIC UNIT OF STORYTELLING : making your characters act

NARRATIVE DRIVE : how to get your story moving, and your reader turning the pages

FORTUNATELY-UNFORTUNATELY : how stopping your characters from staying on the same track powers the story-engine and keeps your reader reading

GETTING FROM ONE SCENE TO THE NEXT : jump-cut or narrated slide? Doof-d00f-doof ending then crash landing, or taking the reader there in stages?

CREATE THE READER YOU NEED : you can make the novel work however you want, as long as you get the reader to read it the way you need them too, and stay consistent.

: deciding what real life facts - geography, history, dates, news, whatever - you can ignore or adapt, and what you must stick to

POINT OF VIEW

POINT OF VIEW & NARRATORS 1: the basics : what point of view is, what a narrator is, and why it matters

POINT OF VIEW & NARRATORS 2: internal narrators : character-narrators who narrate in first person

POINT OF VIEW & NARRATORS 3: external narrators : limited, switching and privileged point of view in narrators who narrate in third person

POINT OF VIEW & NARRATORS 4: moving point of view and other stories : how to work with a moving point of view, second-person narrators and other stuff

HOW TO MOVE POINT OF VIEW : not just between chapters, but in a single sentence. And why (as long as you do it well) no one can tell you it's not allowed.

CIRCLES OF CONSCIOUSNESS : a more useful and sophisticated way of thinking about point-of-view and psychic distance, and how to use it to best effect

FREE INDIRECT STYLE : what it is and how to use it : the huge advantage we have over the playwrights and scriptwriters, so why wouldn't you exploit all the things it can do?

WRITING FROM LIFE

HISTORICAL NOVEL? BIOGRAPHY? When is your life writing actually historical fiction, or vice versa?

CREATIVE NON-FICTION : including memoir, life writing, travel writing. What is it, and are you writing it?

HOW TO DEAL WITH FEEDBACK : Whether it's informal writing-chat, part of a course, or a written report or review.

REVISING & SUBMITTING

REVISIONS: Taking down the scaffolding : many writers find it hard to spot the things which needed to be in the first draft, but must be fished out in revision. Here's how to spot them.

"FILTERING": HD for your writing : an unhelpful name for the single, simplest way to revise your writing into greater vividness.

FILTERING, SCAFFOLDING & HOW TO PERFORM AN EXPLAIN-ECTOMY : more about how to get rid of the extra clutter which is blurring and smudging your story's impact.

CUTTING, CONDENSING & FILLETING: what to do when your story is much too long.

THE SYNOPSIS: Relax! : the synopsis won't make or break your novel's fate, but it can help to give it the best chance. Here's how.

September 6, 2017

How To Handle Feedback On Your Writing

I've blogged more than once about how to give feedback, but most writers get feedback even more than they give it, since as well as workshop friends, you'll get it from teachers, agents, editors, reviewers, friends and family. Here, I'm going to refer to them all as "the reader", because that's what we hope a feeder-back will be: a representative of the readers we're hoping for.

Obviously the setup varies. Some settings are "live": a Skype session with a mentor, round a workshop table, at a one-to-one book doctor session, in virtual workshop on your online course. Some are written - either as comments on a forum, or a marked-up manuscript or a some pages of notes, or a review on a website. But essentially, you have been given something which you have decided you want to deal with. So how do you do that?

First, I've realised that my basic suggestions for commenters have a mirror-image for the writer:

Have a bit of humility: Know that you are (in a sense) the worst reader of your own work, and recognise that a reader's experience is genuine for them. If they felt it, they felt it. That, in itself, doesn't mean you have to change a word, but you are trying to communicate something, so why wouldn't you listen to a report on how it's received?

Listen for specifics: Both about the nature of the reader's reaction, and the words, phrases, paragraphs that caused it. These are gold.

Keep your ears open: Many of us go involuntarily but protectively deaf at bad news (just as many patients do) and then don't hear the equally useful good news. On the other hand, a surprising number of us also don't hear bad news, when it's about what we haven't yet recognised as our darlings.

Think twice before wasting energy trying to explain why you were right to do it this way, and the reader is therefore wrong.

Know that the reader's brutality isn't necessarily right and brave: it may just be because they're thick-skinned or have unconsciously taken agin you or your writing for some reason.

Know that the reader's approval isn't necessarily right and truthful: it may just be because their Social Survival Mammoth doesn't let them say anything which might upset anyone.

If you do propose a solution, let the reader demur about whether it'll work. Your job is not to persuade them that you're right, any more than their job is to persuade you that they are (although if this is a book under contract, it's a bit more crucial that you and your editor can negotiate)

So, when you've got all the feedback, what do you do next? As always, the fundamental options are Accept, Adapt, Ignore, but before we get into that, would asking a bit more be useful, if it's possible? Not as a covert way of fending off the feedback, but to get more light on the reader's reaction. "Which bit was most like that for you?" should push them into specifics. "Do you think it would be better on a plane than a ship?" might be useful, if they're used to perm-ing and con-ing story possibilities and kick-start your own creative motor.

Also, don't be afraid to take into account who your reader is: someone who reads your genre by the ton has difference desires and expecations from someone who never does - and it isn't always the former who will hit the nail on the head for you. And just because the problem your writing tutor highlights seems obscure and technical, that doesn't mean you can ignore it on the grounds that "real readers won't notice": most of our tools for working on readers work in ways that they don't notice.

Accept is easy. "Duh! Of course." Or "Ah, OK, I can see lots of readers might take it that way." And then you change it. But don't necessarily work out the change there and then, at least for anything more than a typo. On the Don't Fiddle principle, it's much safer to wait until you have a list of everything that needs doing, and a plan for how to do it.

Ignore is fairly easy. But, before you press the Eject button, do strip down your "Ignore" to make sure it's not a) a disguise for your own reluctance to murder darlings, b) a reaction to a reader who you have yourself unconsciously taken agin for some reason, c) or because the feedback is about something you didn't ask for - e.g. about macro issues when you were looking for micro ones, or vice versa: unsolicited feedback is not, a priori, wrong.

Adapt is trickier. First, remember that a lot of feedback will be about what the reader experienced as unsatisfactory, but they well may attribute their discomfort to the wrong cause: "it's too long", for example, can have lots of causes, and most of them are not about there being too many words. To decode reactions into causes, try my Fiction-Editor's Pharmacopoeia.

Once you've decided what the real cause is, then lots of the time, if you go on chewing away at possible solutions (I do this on a walk, more often than not) it'll be clear what you need to do about that particular problem. But I want to suggest a crucial shift in your thinking. This is not about Teacher correcting your work, nor about Invader giving orders you should resist. Whatever others have written (literally or figuratively) in the margins of your work, you should give it the same status - no more but no less important - as your own comments have when you do a print-and-mark-up editing session on your own work. In other words, you need to take others' feedback as part of a larger stage of problem-finding, and then use your own sense of what this story is to integrate everything into some kind of plan: a clear to-do list, if you like.

You may be allergic to planning, but don't forget you need the problem-solving to lead to a strong, coherent piece of story-telling. Since in any piece of well-written fiction, every aspect of it depends on other aspects, if you don't think about your process, but dodge about fixing a paragraph here and a plot-line there, it's like loading the car for Christmas: if you throw in anything that your eye lands on, chances are you'll forget lots, there won't be room for everything, and half the presents will get squashed. As with everything in writing, if you get the process right, the product has a far better chance of coming out right too, so do the writerly equivalent of gathering everything that needs to go into the middle of the sitting room floor, and thinking about what order to pack things in before you start.

If there's so much writing and so much feedback that you're drowning, try my post on Taming Your Novel. And if you've sorted out a to-do list but still don't know where to start, trying the one on How To Eat An Elephant.

Finally - which is really first - long before you're staring at the email or the writer across the table, it's worth thinking about when feedback would be most useful, which means thinking about how to ask for the right kind of help. I'm working on a post about that, but meanwhile I've got a good few events coming up, so it'll have to wait. Good luck!

August 17, 2017

Events Round-up: Salons, (Not) Darwin & More

The fact that I'm online in a hotel bar perched above a staggeringly beautiful gorge in North Mexico is not something I'm typing just to make you jealous. I've squeezed in a few days away (photography, poetry, walking, trains ... my usual stuff) while I'm really here for work. But it's made me realise that it's been a while since I posted about what I'm up to in the next few months, so here goes.

I don't know how many readers of This Itch of Writing live in or around Mexico City - although it never ceases to astonish me what distant quarters of the globe the Itch reaches, but if you are...

Thursday 24th August 6pm

EVOLUTION, EFFECTS & AFFECTIONS OF THE DARWINS: a family story (

Evoluci��n, efectos y afectos de los Darwin. Una historia de familia

)

Not a lot of people know that the Darwin-Wedgwood-Galton clan included (and includes) not only scientists but artists, scholars, engineers, writers and musicians. In this conversation with Antonio Lazcano, one of Mexico's most distinguished biologists, and I will be exploring how the family evolved and changed over the years. This event takes place as part of FILUNI 2017, which is the first book fair drawing together university presses from across Latin America and beyond. A long time ago I worked for for a few years marketing and distributing university presses, and now that trade publishing has narrowed its lists so drastically, university presses are often where the most exciting publishing is happening. Although my Spanish is non-existent, I'll be very to see what's going on.

Friday 4th August at 6pm

THIS IS NOT A LECTURE ABOUT CHARLES DARWIN:

creative thinking in the Darwin-Wedgwood Dynasty

In this illustrated lecture I shall be exploring the family's history through the lens of how creative thinking works across the arts and scientists. What did my physicist great-grandfather George Darwin have in common with his artist daughter Gwen Raverat - and what did he not? I am honoured to have been asked by Antonio Lazcano to give this lecture at Mexico's Colegio Nacional, which gathers together the most distinguished men and women in every field of activity. If I've read the website right, it will also be live streamed, although as we're 6 hours behind the UK, so it might be a bit late (or early, for Kiwi Itch-readers, of course!).

Friday 8th to Sunday 10th September

YORK FESTIVAL OF WRITING

As ever, I'll be there, giving workshops on Point of View and Psychic Distance on the Saturday, and Memoir, Biography and Life Writing on the Sunday. I'll also be doing one-to-ones with writers (a bit like speed-dating, but much more useful), and generally hanging around the bar. If you've never been to York, this batch of posts will give you an idea of what to expect; they're still open for bookings, and if you do take the plunge, do please come and say Hi!

Monday 18th September at 9am

WORKING WITH FICTION, CREATIVE NON-FICTION AND THEIR WRITERS

I'm flattered to have been asked to give a workshop at the Society of Editors and Proof-readers' Annual Conference. We will be exploring how writers work - the creative and technical decisions we make and the way we try to put them into practice - from the point of view of the professional editors whose job is to "help you to write the book you thought you'd already written". There is

THE WORDS AWAY SALONS Autumn Season

Do come and join us at the Tea House Theatre Vauxhall, for an informal evening as we welcome a different, inspiring writer each month. Words Away's Kellie Jackson and I start the conversation and everyone joins in, all helped along with plenty of tea, wine and cake. Doors at 7.30.

Monday 11th September 2017 at 7.30pm

IMAGINING AND DEVELOPING CHARACTERS with Monica Ali

Dynamic characters-in-action are the life blood of strong story-telling, but how do you set about imagining people who never existed, then give them the substance and individuality that they need? In this session, we���ll be joined by the award-winning, best-selling writer Monica Ali to explore ways to create living, breathing fictional characters with agency and drive. By the end of this salon you should be flush with new ideas to propel your characters and WIP to the next level.

Monday 9th October 2017 at 7.00pm

WRITING FICTION USING REAL CHARACTERS with Jill Dawson

Writing fiction inspired by a real person or people is an exciting challenge for the writer but fraught with obstacles. Jill Dawson is an award winning novelist who���s especially skilled at incorporating real people in her fiction, the most recent being The Crime Writer about the author Patricia Highsmith. Others include Fred and Edie about the hanged murderess Edith Thompson, and The Great Lover, about the poet Rupert Brooke. You should come away from this evening with a bundle of new approaches to creating characters based on real people.

Monday 6th November 2017 at 7.30pm

SHORT OR LONG? FORM IN FICTION with Tessa Hadley

Ever start writing in one form and find it���s morphed into something else entirely? Join us as we explore the possibilities of form in fiction. Our guest author, Tessa Hadley, is a Professor of Creative Writing at Bath Spa University, and an award winning novelist and short story writer. She publishes short stories regularly in the New Yorker, reviews for the Guardian and the London Review of Books. This salon should appeal to writers who are trying to decide whether to distil their idea into a short story or expand it to a novel.

Monday 4th December 2017 at 7.30pm

POETRY FOR PROSE WRITERS with Maura Dooley

Join us alongside the award winning poet, Maura Dooley, as we discuss how thinking like a poet helps prose-writers to ���flex muscles you don't use enough���. Maura is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and Reader in Creative Writing at Goldsmiths. You should come away from tonight���s salon with a clearer idea of the possibilities, and some creative suggestions to enrich your practice and nourish your prose.