Emma Darwin's Blog, page 2

July 6, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 16: Three Things About Saggy Middles

If you've been told your novel or creative non-fiction has a saggy middle - or you've a nasty suspicion yourself about it - you are absolutely not alone. It's a perennial problem. Writing a novel may simply be a matter of "beginning, muddle and end", but as you discover every time you download an unabridged audiobook, novels are very long, and so the middle muddle is also very long. "Saggy middle" is one of the diseases listed in my Fiction Editor's Pharmacopoeia, but I've decided it's high time I unpacked it in a bit more detail.

1) Saggy middles may have different causes

The stakes aren't rising steadily. "Stakes" are about both what we could win or gain if it all goes right, and what we could lose or suffer if it all goes wrong: the bigger the gap, the higher the stakes. If the things the reader's hoping will happen for your MC haven't got more necessary and more desirable, and the things the reader's fearing will happen for them haven't got more potentially disastrous, then the story sags, because it loses momentum.

Your character isn't still grappling with the need to change. A story starts when circumstances challenge a characters' ideas and plans, force them to respond in new ways both practically and mentally/emotionally. But to maintain momentum and keep the reader reading, after a while you'll have to pose new challenges for them, so your MC needs new information and must find new and different responses. In other words, keep thinking "Then - but - therefore - but - then - but - therefore - but...".

Your character isn't still grappling with the need to change. A story starts when circumstances challenge a characters' ideas and plans, force them to respond in new ways both practically and mentally/emotionally. But to maintain momentum and keep the reader reading, after a while you'll have to pose new challenges for them, so your MC needs new information and must find new and different responses. In other words, keep thinking "Then - but - therefore - but - then - but - therefore - but...".

Your non-linear timeline isn't serving the story. Each time you switch from one strand to another, any saggy middle tendencies will be magnified because the reader is being asked to drop their emotional involvement in one thread, and rev up their commitment to the other. So you'll need to work the structure of how the strands interact - what comes after what, where exactly you stop a scene, and where you start the next one - to maximise the narrative tension. If you repeatedly "cheat" by switching away purely to withold the the outcome of an event, readers will sense you doing that: you need to find a moment which is both a satisfying pause, and holds out the promise that when we come back later, Things Will Happen. More about non-linear timelines and switching between them here .

A zingy opening in medias res has postponed explaining apparently necessary backstory or sidestory until later. Now things have slowed to a crawl as you try to draw together the "now" of the story with all the material which explains and supports it. First, it's worth reviewing how much backstory the reader actually needs: it's probably much less than you needed to write in order to work out the story. Then stringently each scene in the saggy middle, to see if you can bring out, or add, things which build tension and momentum in the "now" of the story.

2) The Midpoint is crucial

Crime writer and writing tutor Caroline Greene talks about the midpoint as the tent-pole which holds up the whole story structure: indeed, what I would call Act 3 (of 5), she reckons is just that single, crucial midpoint scene. Essentially, it's the big turning-point in the centre of the story, when as a result of the main character's trying to get what they need and want, they act in a way that means nothing can be the same again. In The Godfather it's when Michael Corleone has to choose to take the gun out from behind the toilet cistern, and actually do the assassination. In Pride and Prejudice it's Mr Darcy's first proposal to Elizabeth: she is offered a splendid version of the husband-with-enough-money-to-keep-her, which is the only way she can survive in her world - and turns it down.

What they have in common is that the midpoint is a crux of the central issue that the book is about, which is present in the story right from the beginning; the very end of the story is where what started at the midpoint is finally resolved. Indeed, some writers start their novel by writing the midpoint, and work the beginning and end out from there. In Kim Hudson's antidote to the "Hero's Journey" kind of story-structure book, The Virgin's Promise, I think it's the "caught shining" stage. (I do recommend that book, particularly for stories where the central story is psychological: growing up or finding your authentic self, forging your true place in the world.)

3) A saggy middle is not necessarily about there being a lull in the physical action

What matters is that the characters are characters-in-action, and their actions are prompted by the constantly renewing and changing drive to act in the service of what they want or need. True, a powerful midpoint is unlikely to consist of someone lying down and having a snooze (unless your viewpoint character is Lady Macbeth, of course), but it doesn't have to be about an assassination either.

What's crucial is that whatever started your story off, your characters go on trying to get somewhere, action by action, scene by scene, until they find themselves at the crux which is the midpoint. Then, in the changed circumstances of the post-midpoint world, they must grapple with how they will go on. The best analogy I have for this is that of a ship's journey: the point is that every day of that journey, the character has to do something to keep trying to get somewhere.

June 27, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 15: Three Things About Point-of-View

Point-of-view is one of the chief tools you have for controlling your reader's experience of the story, and their reaction to it. So I have blogged about it a good deal, mostly in the four posts in the Point-of-View and Narrators series. This Bitesized series post is a quick check-in with a few of the questions which crop up most often.

1) Readers don't only get involved with the viewpoint characters and no one else.

Think about it: there's no equivalent of point-of-view in films and plays - everyone is seen from the outside - any more than there is in real life. But that doesn't stop us empathising with characters on stage and film, and their fate in the story can still matter to us hugely. So although choosing the point-of-view character/s for a story is an important decision, it doesn't cut the reader off from others who matter. You just need to make put those characters in situations which make us care about them, and make sure they act and react so we do.

And bear in mind that if fiction is built on conflicts between what difference characters want and need (which it is), then a story where we not only understand but sympathise with two, opposing, sets of wants-and-needs, is going get a whole lot more interesting for the reader.

And bear in mind that if fiction is built on conflicts between what difference characters want and need (which it is), then a story where we not only understand but sympathise with two, opposing, sets of wants-and-needs, is going get a whole lot more interesting for the reader.

2) Readers don't only think what the viewpoint character thinks.

Given something like this ���

When Andy went into the station, he immediately found himself surrounded by commuters rushing to catch trains or get to work, while others stood about, checking the departures board or sipping coffee.

��� we are technically in Andy's point of view more than anyone else's ("he found himself"). But we don't seriously doubt that these events, in this story-world, are objectively the case; most readers, present in that scene, would experience it in a similar way. But this is different:

At the station, Andy stumbled straight into the commuter-ants pouring across the concourse, helplessly caught up like a leaf in the stream as they made for the office or the train, drank coffee or stared at the departure board: each one an automaton obedient to the demands of its working life.

Because this is more strongly, subjectively flavoured by Andy's personality, the reader has a parallel knowledge that this may be true to Andy's experience, but it's not necessarily true for everyone; another character might find the bright buzz of the place, the brief human contacts, amusing or energising.

Remembering this is also useful if you're worried about a viewpoint character having views & reactions which readers might find offensive. The more strongly the writing is coloured, even distorted, by those objectionable views, the less most readers will buy into them, or think that you do. Though you could belt-and-braces with another character's, different, take on things.

3) Readers don't mind at all if you move point-of-view within a scene.

Yes, those of your writers' group who believe that moving point of view anywhere except at a scene break is "head-hopping" may tell you it's against the rules. But there are no rules, only tools, and provided you do the move well, taking the reader securely and smoothly with you, the rest of the world really won't care - if, indeed, they notice at all.

What readers don't like is a point-of-view move done badly, so that they're disoriented or confused, or don't know who it is who feels the station as an ant-heap. More on how to move point-of-view successfully here.

May 27, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 14: "Effect" vs "Affect"

One of the most common word confusions I see, even in writers who aren't easily confused, is between "effect" and "affect". It's very understandable - both can be a verb, and both can be a noun - and sorting it out is a bite-sized job, so here goes, with a little help from the Cambridge and Merriam-Webster dictionaries.*

You most often meet effect as a noun. It has many uses, but the one we mostly meet is "the result of a particular influence":

The radiation leak has had a disastrous effect on the environment.

It's too early to predict the effect of the report.

Watch the effect of his announcement on the audience.

She had to wait for the anaesthetic to take effect before she could stitch up the cut.

I think he loses his temper in meetings largely for effect.

So in effect the government have lowered taxes for the rich and raised them for the poor.

Winter opening times and regulations are now in effect.

You most often meet affect as a verb and it usually means "to have an effect" or "to cause a change" on something or someone:

His illness affects almost every aspect of his life.

Both buildings were badly affected by the fire.

Her narcissistic rages are affecting the children too.

You couldn't fail to be affected by this novel.

These new results do not affect the conclusions of this report.

The timing of this recipe may be affected by the ambient temperature in your kitchen.

Affect as a verb can also mean to deliberately put something on:

He says he's leaving and she affects indifference to the news.

The band affect a careless, informal style of dress.

She's recently affected film-star type hats.

And from that usage we get the adjective affected, meaning artificial and not sincere:

His apartment was incredibly affected, all pink silk and fake antiques.

After those terrible reviews her writing becomes more affected, full of dramatic pauses and crude words.

But both words can have other forms, which has the effect of affecting many writers' confidence in using them. (see what I did there?)

Effect as a verb is closely related to the noun, meaning "to cause something to happen", "to achieve a certain result":

We must effect a complete return to more sustainable practices.

By abandoning my lunch, I effect a discreet departure (compare "I affect a discreet departure", which would mean to change the style of exit, not to achieve it successfully.)

Effecting change is possible, but it's very slow and difficult.

Only a police officer can effect an arrest for this type of offence.

Watch! A great change is being effected!

Affect as a noun is a rather different beast, which goes back to Chaucer but nowadays only shows up in psychology and psychiarity, derived from the German Affekt. Here, it means a feeling or subjective experience, an emotion or mood: either the outward signs, or the feeling itself.

The patient showed perfectly normal reactions and affects.

A flat affect is often the most obvious symptom of depression.

Joy, love, contentment and bliss all come under the umbrella of positive affect.

An affective account of this individual's life would emphasise the dominance of mood-swings in determining their activities. (OK, that's an adjective, but you get the point.)

So I do see why writers find it confusing, but it's not actually that complicated. Good luck!

---------------------------------------------

* At the risk of re-running the Boat Race, I should point out that if you have access through your library or institution to the Oxford English Dictionary, there's a lot more detail there.

May 13, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 13: Artist's Dates Don't Have to be About Art

It was Julia Cameron who started the idea of the "Artist Date",* in her book The Artist's Way. The idea is that any creative work draws on a well - or a larder is a more useful image, I think - and if you don't want to run out of creative food and therefore fuel, you have to fill the larder and keep refilling it.

But how do you fill it? A Twitter conversation with children's writer Sally Nicholls has reminded me that people often assume an artist's date has to be about art: painting, or visiting a museum, or playing music. Of course they're wonderful, but they can take some organising and energy, which can be in short supply at exactly the times when you most need feeding and refuelling.

Image by Stux at Pixabay

And when you're self-employed, at home, it's so hard to draw the boundaries. So when, many years ago, I instituted my official Afternoon Off, I made rules first for what it isn't: I do not work on writing (my own, or anyone else's), nor on professional or domestic admin, nor on anything which is all about someone other than myself. For a few hours, I am prioritising my creative needs, and telling everything else it can wait its turn.

Nor do I let myself count the daily duty-walk, or do end-of-the-day-type TV-goggling, noodling on the piano, or reading a magazine. That's like snacking on familiar food that's always in my kitchen: what I need is new flavours and fresh nutrients.

So what might you do? Of course it can be creating something: photography, baking a cake, sewing, putting a new piece of furniture together, or splashing around with paints and paper. But the important point is that it's the process that matters, not the product: you're letting your creative self play, not setting yourself a goal or expecting it to "succeed". (Which, if you'd seen my painting, you'd know is just as well) . So although a Date chosen for the pleasure of it might happen to gather material for a creative project, that's secondary to the Date's real purpose.

In other words, as Julia Cameron herself says, it doesn't have to be directly creative, and it doesn't have to contain art:

The Artist Date is a once-weekly, festive, solo expedition to explore something that interests you. The Artist Date need not be overtly "artistic"��� think mischief more than mastery. Artist Dates fire up the imagination. They spark whimsy. They encourage play. Since art is about the play of ideas, they feed our creative work by replenishing our inner well of images and inspiration.

For those in need of a suggestion for an Artist Date:

Explore your city: Take a walk, and at every turn, choose the less familiar route. What do you learn about the place you thought you knew?

Go to an art supply store with a $10.00 budget. Treat yourself to whatever inspires you. When you get home, use what you just bought...just for fun!

Visit a rug store--looking at the beautiful handmade rugs reminds me of the beauty in creating a handmade life.

Isn't "festive" a great word here? It seems to me that part of what Cameron's talking about is being present: to newness-to-you in the city, to the colours and textures and sense of the hands which made those rugs, to the cool of that paint on your fingers and the marks swooping and wrinkling the paper - and to the experience of being you, doing these things. Note the solo, too: it won't work if some of your attention is with even the bestest of friends.

So although I might well go to a museum, an art gallery or a concert, I might equally well well head out to a new country walk or a National Trust house, or have a massage or a gym session ending in a lot of lolling about in jacuzzis and steam-rooms. And I very likely will finish with the sort of chilling in a caf�� which only works when I'm relaxed enough to be, again, truly present to the world that's going on round me.

And if your Artist Date has to be fitted in between finishing the email and picking up the children, it can be. You can grab a sandwich, lie on the floor and listen with your whole heart to your absolutely favourite album from beginning to end, and splash a lot of paint about, in ninety minutes���

And if you'd like to share what you would do - or like to do - for an Artist's Date, that would be very helpful, so feel free to post it in the comments!

________________________

* Not being German, I'm uncomfortable forcing nouns to behave like adjectives, so in the possessive pronoun goes: "Artist's Date".

May 3, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 12: Don't Pull Your Writing's Teeth

Another thing I frequently find myself writing on students' work is, "Don't pull its teeth!". Here, "it" is a scene, a sentence, a character's thought, or a character's action, which has all the ingredients to be compelling, but somehow falls flat. (Actually, I usually write "Don't draw its teeth" which is the phrase I grew up with. But I wouldn't want you to think we were talking about keeping your sketchbook closed.)

Another thing I frequently find myself writing on students' work is, "Don't pull its teeth!". Here, "it" is a scene, a sentence, a character's thought, or a character's action, which has all the ingredients to be compelling, but somehow falls flat. (Actually, I usually write "Don't draw its teeth" which is the phrase I grew up with. But I wouldn't want you to think we were talking about keeping your sketchbook closed.)

Don't pull the teeth of a thought. This is probably the most common, and I think it stems from the first-drafting writer very naturally mulling over all the possibilities, so they all end up on the page:

Leela gazed at the postcard. Maybe she should just buy a plane ticket to Granada? But that was probably a bad idea. Jim very possibly would still be in New York - and if he was, he would almost certainly be a bit annoyed with her for showing up on his doorstep with only an hour or two warning. No, that really did seem like a bad idea - and it would be rather expensive, too. She probably shouldn't spend that kind of money on just a hope.

See how each action that Leela thinks of - and the reader grabs hold of - is negated? See how many maybe, possibly, almost, a bit and other diluting words there are? In real life we weigh probabilities and opposing arguments, but in print you don't want every move forward to be immediately countered or attenuated. Even if, in the end, Leela isn't going to go, you need to give us the forward-energy first - and only slam on the brakes once they'll have real effect:

Leela gazed at "Sunset Over the Alhambra". She could just buy a ticket to Granada and go. Why not? Cut to the chase, show up on Jim's doorstep, sort it all out before he had time to get angry. Done.

Except that he was probably still in LA. And she could no more afford a plane ticket to LA than she could afford one to the moon. It was hopeless.

Notice how the paragraph-break after Done gives the apparent finish of the thought a moment to resonate before you put the boot in. Notice, too, the one probably which still gets in there - because Leela genuinely can't be sure.

Don't pull the teeth of a sentence. We've seen how maybes and possiblys can weaken the thinking, but there's a different kind of weakening which happens when a writer is - paradoxically - trying to be more exact. I go on about how being specific and particular (scroll down a bit) is usually the best way to fire up the reader's imagination, but there's also the style of sentence which Stephen Pinker calls CYA - which (being better brought up than me) he says stands for "cover your anatomy" - and sometimes "compulsive hedging".

It's the nervous kind of exactitude which must qualify everything, or explain everything, in case you're caught out exaggerating or getting things "wrong" - hence my sense that it's particularly common in historical fiction and other stories resting on researched material.

In the bay, seven boats of varying sizes were drawn up on the very large beach, which looked rather more like shingle than sand.

could be:

Big boats and tiny ones were drawn up on the bay's wide crescent of sandy shingle.

Notice also the looked, which is a classic bit of filtering. Now try this one:

She is very helpful, but it's extremely obvious to him that only her strongly-felt desire to be really thorough keeps her picking almost obsessively at the carpet even after they'd surely found all the broken glass. Though it's very likely that she doesn't want to talk about Dan, of course.

could be:

Long after they've found all the glass, she keeps on picking helpfully, even obsessively, at the carpet. Or does she not want to talk about Dan?

Don't pull the teeth of a scene. If you bring the picnic scene to the climax of the row, the proposal, the murder or the eureka moment - don't let everyone then just pack up and depart unchanged. These events have consequences (if they don't, why are they in the novel?) so make sure they resonate through what follows, proportionately to their importance.

Indeed, what you thought was the climax may in fact be the midpoint: the point when the characters must act, after which nothing can ever be the same. If so, don't short-change the reader of that. Alternatively, you could cut immediately after the big bang - and let the possible consequences ring in the reader's head over the chapter-break. (Just bear in mind that this trick gets very wearisome, and the law of diminishing returns soon sets in.)

My long-ago choir director used to say, "From being a mezzoforte choir, may the good Lord deliver us". Musically, "moderately loud" is chiefly useful as a jumping-off point for music which is about to do something more definite. It's choirs who don't trust themselves who get stuck at mezzoforte level, too uncertain to commit - and in turn the audience can't relax either. Similarly, readers experience writing as confident, and relax into the story, when the writer does things wholeheartedly, without hedging, losing their nerve, or letting their writing draw their storytelling's teeth.

So, if you've realised things are too mezzoforte for too long, the solution is usually to go for either more, or less: either forte or piano. Either put Leela through the flaring hope of sorting things out with Jim - and then swipe her with the denial of that hope - and then move on. Or, if Leela's ditheriness is central to who she is and to what powers the narrative drive, you could do the ditheriness forte: not just a series of toothless probablys and possibles and things briefly raised and easily dismissed: make the dither a series of mounting hopes, each of which is, ultimately and agonisingly dashed.

April 11, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 11: "Who Says This?" Make sure the reader knows who's talking.

One of the most frequent things I find myself writing on students' manuscripts is "Who says this?" I did a big post on writing dialogue a couple of years ago, so this is a round-up of solutions to this specific problem.

Start a new paragraph when the speaker changes. This doesn't mean that every speech must have its own, standalone paragraph, separate from any narrative prose, and it can make the narrative feel very choppy if you do.

If the reader has to stop work out the speaker, or is wrong-footed to find they've been "hearing" the wrong speaker, you've failed as a storyteller.

We're not writing a script for actors: dialogue and narrative are all part of the same medium, so they need to flow one into the next. So you'll often want to ...

Image credit Kate Kalvach at Unsplash

Image credit Kate Kalvach at Unsplash... Connect the speech to an action by the speaker. The convention is that the grammatical subject of the narrative sentence is also the speaker of any dialogue, if they're in the same paragraph. If the speech is a standalone paragraph, then there's no such anchor for the reader.

Differentiate characters' voices. A radio drama producer I know takes every script and puts a ruler over the left-hand margin, where the characters' names label each speech. If she can't then tell who says what, she rejects the script. But you can be quite cold-blooded and deliberate in maximising the differences between characters' voices.

Use speech tags. I said, she says, they will say, are almost invisible, fancier speech tags are much less so, and some I see are truly awful. More on speech tags here. But if every speech has a tag (particularly if they're always in the same place in relation to the speech itself) even said will start to stick out .

If the reader needs an anchor, they need it soon: a good rule of thumb is to give the reader that handhold - an action, a speech tag, a name spoken - no more about than a line and a half after the beginning of the paragraph.

In a two-handed conversation you probably need an anchor about every five speeches. You will need more if there are more speakers, so it's worth developing a repertoire of anchors and where to put them:

"What do you mean?" I said. "You can't do that!"

Sally poured water onto the coffee. "Why not? Who's to stop me?"

"Oh, don't be ridiculous, the pair of you!" Yousuf burst out, but he didn't look particularly exasperated.

Sally muttered that she wasn't going to be told what to do by a pair of jumped-up adolescents, then pressed the coffee-plunger so hard that hot water and grounds slopped out over the counter. "Now look what you've made me do!"

I said as calmly as I could, "Never mind, Sally. I'll get a cloth."

Starting the line with a speech tag guarantees that the reader will hear the right speaker:

Andy said, "You can't know that it was Gerry. It might have been anyone."

But my sense is that you don't see this so much now, though I'm not sure why. For what it's worth, I chiefly do so when I'm using reported speech:

Andy said that no one could know it was Gerry: that it might have been anyone.

Or I move it a little way in, which to my ear gives the whole line more dynamism and drama.

"You can't know it was Gerry," said Andy. "It might have been anyone."

If one speaker quotes someone else's speech you need to demarcate that speech-inside-speech with different speech-marks:

���Well, of course I said to him, I said, ���Why don���t you pick on someone your own size?��� And of course he just stormed off, didn't he. Couldn't handle being told off, could he!��� (normal UK book practice)

���Well, of course I said to him, I said, ���Why don���t you pick on someone your own size?��� And of course he just stormed off, didn't he. Couldn't handle being told off, could he!��� (normal US practice, and normal UK magazine pratice)

or you could use reported speech:

���I said to him, I said, why didn���t he pick on someone his own size. And of course he just stormed off.���

Don't forget that reading aloud can help highlight the who-says-what problems.

April 1, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 10: Ten Reasons to Read Your Work Aloud

You know there are no rules for which words get on the page, nor for how you should set about putting them there. But there are tools - and one of the sharpest and most universal is reading your work aloud. What's more, it applies to any kind of writing, from poetry and fiction to your doctoral thesis. I'm not talking here about preparing reading for events or reading at events, but about reading aloud, to yourself, as part of the editing process. Here are some reasons why it's such a good tool, and some things to help you wield it.

1) Meaning into sound: Your brain has to analyse those black marks into sentences which mean something, before it can set the motor nerves in your lips, tongue, vocal folds, jaw and diaphragm working, and control them to speak that meaning. This process gets you closer to the experience of the reader, who doesn't already know what the words are.

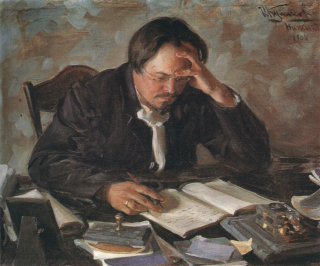

Painting of Russian writer Evgeny Chirikov by Ivan Kulikov (1875-1941) Source Wikimedia Commons

2) Checking words: When your brain meets a typo or a literal it will say to your reason, "Huh? How am I supposed to say that?".

3) Checking sentences: When your brain meets vocabulary, grammar, syntax or punctuation which doesn't add up, it won't know how the stresses, inflections or pauses should go - because it's not sure what the meaning is. So it'll say to your reason, "Huh? How am I supposed to shape this sentence?". Oddly, reading aloud often works for picking up homophones too: rain, rein, reign and Rayne may sound the same, but they don't mean the same, and your brain spots it even if your spellchecker didn't.

4) Shape and rhythm: If your prose tends to fall into the same shape and length of sentence too often, this monotony is quickly revealed, because the sentences will all have the same rhythm and inflection. It'll also show, if your sentences are too messily long, or to boringly consistently short.

5) Punctuation: Punctuation originated as a way of registering in writing how a sentence would have been spoken to make its meaning clear, in the absence of the speaker. As "reading in your head" developed in the 17th century (yes, that recently), punctuation marks came to have a slightly separate life and set of rules for on-the-page sentences. But your brain-mouth-tongue system, trying to speak the meaning of your sentences, will often point out where the commas and full stops should be - and where they shouldn't.

6) Repeats: Your aural memory registers what you've just read aloud: if you over-use a particularly noticeable word, use the same metaphor two pages running, or the same phrase very often throughout the book, your memory will alert you, even if your eye-reading didn't.

7) Dialogue: If your characters' voices are unconvincingly written the clunkiness will be more obvious when you voice them (sorry!). If they're poorly differentiated, they'll all sound the same. For more on dialogue, click here. And I've never worked out a consistent, find-and-replace type rule for when to contract do not into don't and would have into would've, and when to let them stand (and vice versa), but your voice will tell you what comes naturally in narrative and dialogue.

8) Tongue-twisters: If you struggle to get your tongue round a sentence, chances are your reader's mind will struggle too. Having said that, I've sometimes found that a sentence which works really well on the page, doesn't work when I'm reading at an event, and vice versa. I'll edit it for events, but even when I could change the print version - say for the paperback - I'll probably let it stand. Horses for courses.

9) Speed: Reading aloud, you can't skim, as your eye so easily can with a text that you know by heart (and may be thoroughly fed up with): to communicate it at a normal, readerly pace, you have to read what's actually there.

10) Getting someone to read your work to you can help you to experience it from the outside; some writers I know even use the read-aloud facility of their word-processor. And if your reader-aloud is human, they may give you useful feedback. What this doesn't do is put your words through the ultimate mental-physiological stress-test of you reading it yourself. Some writers record their own reading-aloud and listen back, again for the getting-outside thing, which could be worth trying.

The editorial read-aloud process

A full read-aloud is probably most useful at a late stage. But reading paragraphs or pages aloud to find out whether the narrative voice is working, whether the dialogue convinces, or whether a particularly tricky couple of sentences are finally reading well, will be super-useful at any stage. To get the most out of the process, bear these in mind:

a) Have the text in a convenient form not just for reading, but for marking things up with as little fuss as possible, without losing the forward momentum of the reading. For me, that's a generously-marginned printout and a biro; if you're on screen, it's perhaps track-changes, and knowing the keyboard shortcut for making a comment balloon. Above all, make sure you don't get sucked into fiddling.

b) You're not acting - even professional audiobook narrators would say it's a very different job from acting - but to get your brain engaged you do need to be trying to communicate the story and characters to an imagined someone.

c) Drink lots of water and keep going with the snacks. Reading aloud is dehydrating, and uses calories too. A real energy slump can leave you disengaged and mumbling, and you'll miss things you'd otherwise have picked up. If you're going straight through it will take a day, and you may get a bit hoarse.

d) Try not to be self-conscious: truly no one's listening. If you still can't bring yourself to do it, it's probably your Inner Critic trying to shame you into staying safe, by dressing up as your Inner Elocution Teacher. B***cks to the IC: they just don't want you to do what at heart you know your writing needs.

e) Self-consciousness is death to good writing, and to reading-aloud. To communicate, you have to feel free to be whole-hearted about it. If you really can't face the thought that others might hear you, pretend you're a spy in a Cold War Moscow hotel, and put music or the radio on to baffle the unseen listeners. And you might not be a good candidate for recording yourself.

And if you're still not convinced, I'll share an anecdote which actor, novelist, and audiobook narrator extraordinaire, Imogen Church, told in a Society of Authors seminar. Before he was a bestselling crime novelist, Mark Billingham was an actor, and so he narrates his own audiobooks. Apparently, he won't send the final draft of a new book to his publisher until he has recorded the audiobook. He's that convinced that only in reading the book aloud will he find every last thing which could be working better. What better reason do you need to read your work aloud?

March 24, 2022

Are You Looking For Help With Your Writing?

Are you looking for help with your writing? Whether you write fiction, creative non-fiction or short stories in any genre, I currently have a few spaces in my diary. I offer one-off tutoring, advice, appraisals and editorial help, as well as longer-term mentoring, and workshops for all kinds of groups & courses, in-person or online. For more information and to find out how I can help you, click through to my website.

And of course you can always help yourself to the famous Tool-kit, here on This Itch of Writing.

October 1, 2018

All the posts I mentioned at the Bront�� Parsonage Festival of Women's Writing

A couple of weekends ago I had the pleasure of holding two workshops, as part of the Festival of Women's Writing - which doesn't at all exclude men - organised by the Bront�� Parsonage Museum, and held at the entirely wonderful Ponden Hall. We covered a lot of ground, and in the nature of things, many topics cropped up which are expanded on in posts here on Itch. So these are links to the ones I particularly remember mentioning. If anyone remembers any others, do drop me a line, and I���ll try to dig it up. These, and a lot more posts, are all in the THE TOOL-KIT (click that, or the link in the top right-hand corner).

GENERAL

PSYCHIC DISTANCE: what it is and how to use it : also called narrative distance; an extraordinarily useful way of thinking.

SHOWING AND TELLING: the basics : how to use both to make your story do everything you want it to do.

"RE-IMAGINING IS PARTLY A PROCESS OF FORGETTING": Why factual accuracy in fiction is not enough, and may even be a bad thing. The post otherwise known as Yours to Remember, and Mine to Forget.

WRITING HISTORICAL FICTION:

My column, Dr Darwin's Writing Tips, at Historia, the Historical Writers Association e-zine (which I also recommend in general, for exploring what���s going on in Historical Fiction at the moment

WRITING ETHICALLY WITHOUT CLIPPING YOUR CREATIVE WINGS : how to build stories on other ethnicities, genders, cultures, sexualities, classes, religions, (dis)ablements, ages, histories, countries, nationalities, than your own, without censoring yourself or treading on toes

: deciding what real life facts - geography, history, dates, news, whatever - you can ignore or adapt, and what you must stick to

SO WHAT COUNTS AS HISTORICAL FICTION? : for writers, for readers, for the industry. See also a more recent exploration here: http://www.historiamag.com/what-counts-historical-fiction/

HISTORICAL NOVEL? BIOGRAPHY? When is your life writing actually historical fiction, or vice versa?

CREATIVE NON-FICTION : including memoir, life writing, travel writing. What is it, and are you writing it?

NON-LINEAR NARRATIVES : what they are, whether to use one, and how to make it work

YOUR BOOK, YOUR RULES, BUT MAKE SOME : more on how to make sure your book works in a consistent way - and save yourself some effort too

My book, Get Started in Writing Historical Fiction, is available via all good bookshops, so that link to the Online Retailer Who Must Not Be Named is only in case you can't track it down any other way!

MAKE YOUR STORY SHINE: Self-editing:

NARRATIVE DRIVE : how to get your story moving, and your reader turning the pages

PAST AND PRESENT TENSE : the pros and cons of both : the different issues that arise with first and third person for each tense, and why the new creative writing orthodoxy is wrong

WRITING A SCENE : when to Show/Evoke/Dramatise, when to Tell/Inform/Summarise, and how to work with both to control how your reader experiences the scene.

CHARACTERISATION-IN-ACTION : how to develop your characters-in-action and make sure their journey is really compelling.

POINT OF VIEW & NARRATORS 1: the basics : what point of view is, what a narrator is, and why it matters (and links to the rest of this 4-part series)

FLASHBACKS AND BACKSTORY : how to handle the stuff from Before The Story Starts

WRITING DIALOGUE : how do it well, how to make it better

FREE INDIRECT STYLE : what it is and how to use it : the huge advantage we have over the playwrights and scriptwriters, so why wouldn't you exploit all the things it can do?

WRITING SEX: ten top tips : writing sex is notoriously difficult, but this should help.

TACKLING REVISIONS AND EDITS : feeling as if you've got to eat an elephant, and your spoon is too small? Here's help.

DON'T FIDDLE : how to stop yourself endlessly tweaking, poking and mini-editing and getting in a muddle, and keep moving steadily forward whether you're drafting or revising.

"FILTERING": HD for your writing : an unhelpful name for the single, simplest way to revise your writing into greater vividness.

GETTING FROM ONE SCENE TO THE NEXT : jump-cut or narrated slide? Doof-d00f-doof ending then crash landing, or taking the reader there in stages?

THINKING AND INTROSPECTION : how to keep the reader reading when there's no physical action

CREATE THE READER YOU NEED : you can make the novel work however you want, as long as you get the reader to read it the way you need them too

The online course Self-Editing Your Novel at Jericho Writers. The November course is actually full, but the next one begins on January 22nd 2019, and later dates will soon be up. Generally speaking, it runs four times a year - January, March, June and September. I notice that at the moment the course is priced in Euros, which makes it look more expensive than it is!

September 15, 2018

"No Word Count Boot Camp or Productivity Push": #100daysofwriting

I've got a novel to revise.

At least the York Festival of Writing and the Historical Novel Society Conference have been and gone. But the next Self-Editing Your Novel course is about to start, I'm off to Yorkshire for the Bronte Parsonage Museum's Festival of Contemporary Women's Writing and life is decidedly busy on other fronts.

Then there are the writers I'm helping as a tutor and mentor, and occasionally boring old real life has to be dealt with. And did I mention (no, surely not!) that I have a new book coming out in February? So there are press-releases, and illustrations, and absolutely, totally and completely the last chance to find those typos. Then there's the 3am horrors I get of every reviewer hating the new book and saying so - and the next night's variation, which is that it isn't reviewed at all.

And though it's obvious that the horrors can be paralysing, and other work has a way of bleeding into what ought to be writing time, the good stuff also derails me. It's nice to be involved in a good writing workshop; it's good career sense to browse in the library or make contact with other writers on social media; and why wouldn't I say "Yes" to the next person who ask me to do work which I need or enjoy? And that's before we even start counting all the other things that other people, from the government to the baby, demand that you to treat as being more important and more urgent than your writing. Given the such demands and pleasures, which of us wants, instead, to deliberately shut the door and to fight our way into a hydra-headed plot-muddle, or crawl along picking up every tiny consequence of having moved a crucial scene from a catacomb to the deck of a square-rigger?

So half a hundred things can stop you knuckling down to the very thing which is at the core of all of this, the thing without which none of it would be happening: your own writing.

And this is a problem for writers whether or not you earn your living by writing and writing-related work. It is not easy, and often not appealing, to go on shutting up the anti-writing demon, and keep on keeping on at something which is lonely, hard work, not immediately rewarding and doesn't have to be done today ... because maybe tomorrow would do. But that way procrastination lies.

It's harder still if you have yet to tame your novel, or even when you have a perfectly good To-Do list but not the first idea how to tackle it.

In fact, this time I do actually know what I must do, I think, and I've broken it down into clear and specific jobs, so that I don't fiddle. But actually settling down and doing it, on the other hand...

So when novelist Jenn Ashworth said on Facebook (and Instagram, and Twitter) that she was settling in for another #100days of writing, I jumped in to join her. Jenn is not only a terrific writer - you may remember her terrific guest post here on the Itch about how her novel Fell works - but a vastly experienced teacher, and mentor for Arvon and elswhere. She's @jennashworth82 on Instagram, and @jennashworth on Twitter.

Not that "joining" is exactly formal. I'll let Jenn explain:

I did a quick count yesterday and I think there are about 40 of you, across various platforms, signed up to join in with the second #100daysofwriting and that isn���t counting those of you who started earlier this month or in August.

I���m a bit anxious. What if I mess up and you���re all looking at me? Never mind. There have been a lot of questions so I will try to respond in this post.

Anyone can join in. Just turn up every day. One sentence counts. Opening the word document counts. Taking yourself for a walk or a nap to figure out a problem counts. Any type of writing counts. You don���t have to be published or be working toward publication.

No word count boot camp or productivity porn. If you don���t have the spoons to do this every day or you care for other people then you can change the rules so they suit you. If writing is part of your job (academic friends who are working to contract - this is for you) and you need to care for yourself and your colleagues by resisting work at weekends, then change the rules to make it work for you. If you miss a day or a week or change your mind it is okay.

Let���s be gentle and see what happens: I���m doing this because it reminds me to make writing more important than the stuff other people want me to make important. Let���s go! 2/100

And she went into more detail about how and why it works, here on the Prolifiko blog.

So "signing up" is simply making a decision, for yourself, that showing up to the page on as many every days as your life allows will be useful to you and your writing. Some of those doing #100daysofwriting are writing PhDs, or poetry, or articles. The hashtag is just a way of us connecting with each other: acknowledging that we're all writing, but that the writing is whatever and however it and each of us, today, need it to be. And the 2/100, or whatever, is your own, personal count of where you are in the hundred days. Everyone's will be different

In my case, on this first day I've done some writing in the sense of importing the draft from Word, and getting it ship-shape as a fresh Scrivener project, and using note-making to get my creative brain going on the specifics of how to achieve what I know it needs. I've also done some more writing as thinking on my walk. That the words in the draft itself are no different doesn't matter. It all counts - it's all writing. 1/100