Emma Darwin's Blog, page 3

August 18, 2018

Being Published Part 4: Covers

This is the third in a series of posts which I'm planning in the run-up to next February, when This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin will be published. In each I'll try to shed light not only on the practicalities of what happens when your book is being published, but also the sometimes surprising ways that this stage of the writing life can affect you and your writing. Part 1: Contracts is here. Part 2: Editing is here and Part 3: Permissions is here.

Your book is (not) your cover

The cover of a book is a hugely important - possibly the most important - selling tool the publisher has. To start with the brute industry facts, I'll quote the chief fiction buyer of Tesco, some years back. When she was deciding what to re-order, and what to stop stocking, she would stand back from the whole display, look at it hard, then turn her back and see which covers she could remember. Those were the ones granted another few weeks' life on the shelves of what was then the nation's biggest bookseller. And if you're horrified by that but luckily don't care because you don't aspire to Tesco, I should point out that the branch of Waterstones which makes the most money per square foot is ... Gatwick North.

TooLongDidn'tRead: drawing potential buyers in quickly, steering them to the book which will genuinely intrigue them, then keeping them there long enough to decide to buy it and then not to bother with an (in-flight) movie, depends hugely on the cover.

So the cover must speak to the reader by Showing, not just Telling, what kind of book it is, and almost before they can read the title. And it needs to be the right reader: the one who will read the title and author and any cover quotes, be interested enough turn it over and read the blurb, be intrigued enough by the blurb to flip through a page or three - or do the online equivalents - and end by buying it.

So it can't represent everything your book is, any more than a "hook line", summary, blurb or synopsis can. Indeed it's best to think of a cover as being like those: sales tools for the industry, not embodiments of your creation. And it's wise to remember that, as a writer, you are by definition in a tiny minority of the readers your book must attract for it to break even. What matters is atmosphere, style, intrigue, echoes of the "If you liked X you'll like this" kind. So - sorry - accuracy to history, geography, the looks of the main protagonists or the setting of the story only matter if they're such drastic mis-steer the book will be a laughing stock. It's incredibly annoying to have inaccurate things on the front of your story - and I hope you won't. But in terms of the book's prospects, it's much less important than other things that might go wrong.

The cover, to be crude, should also not draw in the wrong kind of reader - and even more so these days. Just earning the microscopic amount they do for a copy does little for the longer-term life of publisher, book and author, so word-of-mouth has always been important in selling books. But nowadays the wrong kind of cover can be more immediatly disastrous: the last thing the publisher wants is for someone to buy it, discover it's not what they expected at all, feel they've been cheated out of time and money, and post one-star reviews on Goodreads and The Online Retailer Who Must not be Named.

One more thing in the algorithm: statistically speaking, the book a potential buyer is most likely to buy is one by the author they most recently read and liked. The next most likely is a book which is very like that book. That's another reason to let go of the idea that the cover is a summary or an illustration of your book: what it needs to be saying "This book is about new interesting story X, for readers who like stories by/like/set in/about Y."

That may be obvious with commercial fiction, but literary fiction too (click here to explore what we mean by those terms) has its cover styles, tropes and selling messages - and as with the text inside, that may include playing with famous predecessors. The trade paperback (=instead of a hardback), UK edition of Mike Thomas's Pocket Notebook, was a witty play on the very famous Penguin cover for Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange. But the mass-market paperback cover changed direction, emphasising the rough, real-life as well as satirical nature of the story.

All of which is why, by contract, you won't have right of veto over the cover, only the right to be consulted: you're an expert in your book, but not (generally speaking) in book design or bookselling - although if you are either of the latter, then your publisher will certainly listen to you.

Time was when authors first discovered what their cover (which arguably isn't "theirs", but belongs to the collaborative artefact which is the published book) was like when they saw it in a bookshop. It's largely thanks to the Society of Authors that we now have that right to be consulted, and since the cover's such a crucial selling tool you will probably start hearing about what's planned fairly early: just after you send in the final text, and before the copy-edit would be typical.

With my first two novels that right-to-be-consulted largely consisted of my UK editor saying "Here it is, hope you like it," and me saying "Oh, that's fantastic, thank you so much!" because that was what I felt. My US editor did ask what ideas I had, but when it comes to covers I can't think in the abstract, I just know it when I see it. Beyond saying I hoped it wouldn't involve headless bodices - then the clich�� of commercial historical fiction covers - I couldn't be much help. And luckily I loved that cover too, though it was very different.

Last thought: one thing I regret is that I hadn't realised then just how anxious editors are when they send over the cover: publishing is a creative process, if a second-order one, and it's a huge creative responsibility, as well as a financial one. Editors are really nervous, and I fear my overt response was rather more workaday-appreciative than - looking back - would have been true to my genuine thrilled-ness.

Practicalities

The whole process of cover design takes time. Larger publishers have in-house design departments, but either the importance of the book, or the press of work, may mean they use a freelance. Publicity, marketing and sales will all have their input, and the publisher will hope to get the cover onto the Advance Reading Copies. These - otherwise known as "bound proofs", "uncorrected proofs" or just "proofs" - will be going out to reviewers and the big buyers at least six months before publication date, and very possibly much longer. (Though it's not a catastrophe if the cover's not ready: A Secret Alchemy went out with a perfectly functional, knocked-up-in-house cover because my editor was ill and the real thing got delayed.)

The ARCs are the first testing ground for the cover out in the industry, and it's by no means uknown for one or more of the big buyers - the supermarkets, Amazon, the big wholesalers, the library suppliers - to say that they don't think it works. It would be a foolish publisher who didn't listen to their reasons and tweak the design to suit. And it would be an insane publisher who ignored a big buyer who says, "If you put that cover on it, we won't take the book because it won't sell. If you put a cover on it like Smash Bestseller, we will." If you hate Smash Bestseller's cover, say so to your agent, but in the end the only recourse is to remember that a publisher's first duty to literature is not to go bankrupt, and open the gin.

The next big testing ground is the feedback on and sales of the hardback (or trade paperback), and everything to do with the cover will be re-examined in the light of that, before the mass-market paperback cover is decided. It's a smaller space, so details may just become too fiddly, and there may be review quotes or puffs to fit on it, or even prize nominations. If you see a drastic change between hb and pb, then the publisher has decided the hb version doesn't work - so fingers crossed the new one does. Or it may simply be that the market for the hardback (cool early-adoptors, say) is different from the paperback (mainstream commercial readers). This is more likely if it's fairly literary, because the paperback can't afford to appeal only to hard-core literary readers: there aren't enough of them. Either way, the-book cover and audio book will reflect whatever the physical book is currently wearing.

With This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin, I've been much more involved than with my first novels. My editor feels that the author as well as the publisher must be happy with a cover, and more generally Agent Joanna says that publishers do involve authors much more these days, if only to avoid the fallout of it all going horribly wrong - which, to be honest, it can.

Indeed, there's more blood on the carpet between authors and publishers over covers than almost anything else, but for all the reasons I've been outlining, by no means is the author always right. Still, when you or your agent are considering offering a book to a publisher, it's not a bad idea to take a long, hard look at their covers from the last few years: some definitely have better eyes - and design departments - than others.

If there's a really big gap between what your publisher thinks will draw in readers, and what you think will, then you may like the cover in itself but feel is deeply wrong for the book - or you may just hate it. For all the reasons I've outline you may just have to live with any of those, but hopefully your editor or your agent can explain the thinking behind it, to the point where you can at least make your peace with it.

If you and your agent truly feel the cover is catastrophically wrong, then of course you must at least try and change things - and this is one place where having an agent to do the fighting with your editor about the cover, while you have friendly and creative conversations with the same editor about the text, is worth every penny of your agent's 15%. But even if you do manage to persuade the publisher - against what they would say was their better judgement - to change it, remember that if the book bombs, the publisher will be able to blame that on it having a cover they always said wouldn't work.

So, how are covers designed? In terms of how designers think, this is a great post, by Jo Lou, over at Electric Literature, about the journey from first to final cover of ten different books - and this is another of hers on similar lines.

I know the majority of Itch readers are probably mostly writing fiction, but the need to evoke both what the book is, and what kind of book it is, is equally true of creative non-fiction and perhaps clearer to see, and the cover of This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin is a case in point. It was designed by Liam Relph, and to my eye it evokes books like Adam Rutherford's A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, but also perhaps memoirs such as Rose Tremain's Rosie: scenes from a vanished life both of which are good steers for readers who might like it.

But detail matters too. We discussed if the author's name should be above, or below, the title. Above was a nice and clear space, while below risked getting it mixed up, visually speaking, with the subtitle and the "tree of life". But we are hard-wired in the West to read top to bottom. The title is the opening statement - this is a book about Charles Darwin - and visually and verbally it has a joke tucked in; people smile (I know, I've seen them). But if they don't see the author's name till after that then it forms a second joke, a punchline, that the reader didn't see coming: that this book is by another Darwin.

It was important, too, that the "tree" was effective both for readers who know it's derived from The Ancestor's first "tree of life" diagram of the evolution of species from common ancestors, and everyone else. The diagram is pretty famous among anyone interested in these thing - but that's still only a fraction of the people who we can hope would be interested in the book. Some of the designer's versions of the tree were flat colour, but the varied, speckly colours, and the drop-shadow, of the final choice is both visually more dynamic, and to my eye evokes something organic: a microscope slide in biology, perhaps. Since this is not a book about evolution, nor about The Ancestor, accuracy to the actual diagram isn't important, what matters is that it accurately evokes the way the book takes all those things and appliqu��s them together to make a narrative of my journey.

It also matters that the sales team of Holland House Books love it, and so did the vastly experienced and successful booksellers at my local independent bookshop, Village Books. When I took in the Advance Information sheet which is each book's calling card in the trade, their always-friendly welcome to a local author (and good customer) turned into a "Oh, yes," when they saw the title, and an "Oh, fantastic!", and a big thumbs-up, as they assimilated the cover. Booksellers know more than anyone else about the day-to-day reality of what draws readers to books, or doesn't.

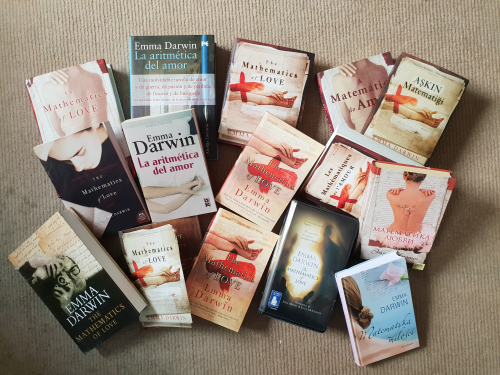

If your book has sold rights in other countries - particularly if that's happened via your publisher - then the chances are you'll have very little input into the covers. Visual traditions are very different even between North America and the UK (which is another reason to resist automatically selling a publisher World Rights), and so are their book markets, so on the whole you'll just get what you get. But as an idea of what might happen, I've rooted out all the different copies I can find of The Mathematics of Love.

Left to right, top to bottom (hb = hardback, pb=paperback, tpb=trade paperback)

US hb, Spanish hb, UK hb, Portuguese tpb, Turkish tpb

US pb, Spanish pb, UK pb, French tpb, Russian hb

UK Large Print, UK bound proof*, UK bound proof for the paperback (this an unusual thing), audio book, Polish hb

* the UK bound proof had an outer cover cut like the letters, and inside that was sales blurb. That was very expensive, and very rare.

Notice how the quite literary-looking, and square royal format UK hb was very cleverly morphed and riffed into the paperback - clearly the same book, but subtly different. You can't see that the US hb had lovely deckle-edged paper to give it a vintage feel, and a cover that surprised my agent, given how prudish the US market can be, but the pb definitely went after a different, less overtly historical-fiction market. Notice too how many of the foreign publishers went with the UK design - but others did their different thing. And the strap on the Spanish hardback mentions The Ancestor, but then, they are his Spanish publisher...

Like I said, always remember that the cover is, at heart, a sales tool.

July 18, 2018

"How dare they?" Can you write fiction ethically, without clipping your own creative wings?

As you may know, I also have a column, Doctor Darwin's Writing Tips, over at Historia, the magazine of the Historical Writers Association. A version of this post first appeared there, but in an era when we've all become more sensitive to questions of cultural appropriate in the arts, it's relevant much more widely. Certainly if you want to build your story on people of another ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, (dis)ability, class or perhaps just wildly different life-experience, there's work to be done compared to what you'd need if you stayed inside your own.

So the ideas and strategies I've suggested in this post are, mutatis mutandis, relevant to anyone who wants to write about - well - almost anything beyond their own edges. And before you snort with outrage at the idea of anyone telling you what you're "allowed" to write, or the idea that it's not possible to imagine beyond your own edges, I should explain something that I myself hadn't clearly realised until I started working on this piece. The processes that will help you to write ethically are the same as those that will help you to write better. And there isn't a reader of This Itch of Writing, I'm absolutely sure, who doesn't want to do that.

***

Dear Dr Darwin

I���m working on a script set in the past. The central character is a fictional young Black teen, and two major characters are actual historical figures: a young Native American warrior and a mixed-blood warrior; the true purpose of the script is to tell their fascinating story. I, however, am White. I am confident that I can tell the story well, and am empathetic as to the struggles both the Blacks and the Native Americans had to endure, and still endure. But there is a part of me that feels like I do not have the right to tell these people���s stories. On the other hand, I feel "why not?" Michael Blake wrote Dances With Wolves, Ezra Jack Keats��� characters were African Americans.

Are there multicultural boundaries we must not cross in historical fiction? And if so, what are they? Or turn the question around, how do we cross these multicultural boundaries without stepping on toes? Thanks for your time.

Tony

Dear Tony

Most writers rage against any suggestion that they���re not ���allowed��� (by a nervous publisher or the mobs of social media) to write anything they like: how dare they tell us what to do? But most writers have also been enraged by slipshod, catchpenny or downright poisonous versions of things we have directly experienced, written by those who haven���t: how dare they tell us what it's like?

And this is not an abstract problem: all women and a good few men rage at how few scripts that actually get made pass the Bechdel-Wallace Test in a male-run Hollywood; on the other hand, a US editor I know of rejected a YA novel set in Spain on the grounds that the writer isn���t Spanish. So, can good, authentic, responsible and thrilling stories rooted in historically and currently disadvantaged groups only be told by writers of that same group?

This particular ethical minefield was sown first in Anthropology, by our modern, white, western and very well-founded guilt about cultural appropriation, and if any readers think this is only a 21st century problem, just look up the furore over William Styron���s Pulitzer-winning The Confessions of Nat Turner. But it���s been rendered creatively toxic by the ���calling-out��� culture which thrives on the undeniable fact that racism happens in small ways that support the big ones, and that everyday sexism is not "just a joke". You can agree with all that, and still find it disastrously self-conscious-making to have a monitor for these things sitting on your shoulder during that first draft, and later. (A parallel could be how many writers, specially those with dyslexia or similar difficulties, find having a school-bred spelling-monitor squatting there hamstrings their first-drafting.) But you only have to spend half an hour on Twitter to have that calling-out voice in your ears, and even reading a responsible, nuanced article about these issues in the culture in general can frighten writers back inside their own edges for good.

You could create a fictional character who you do feel entitled to inhabit ��� presumably in your case, Tony, a white character ��� and show us the world, tell that story, through that consciousness. But that may make some storytelling impossible, if events would be radically changed or hopelessly inauthentic: Jane Austen, famously, wrote not a single all-male scene, but it's simply not possible to write an authentic and natural men���s locker-room scene by putting a woman in it. More fundamentally, it would become a completely different project, de-centering from what you want to centre it on, and arguably a worse act of cultural appropriation: it would betray your reasons for embarking on this project in the first place, which is to put the experience of these people front and centre.

So what do you do?

First, tattoo on your monitor is that it���s your book and your rules, and you can���t libel the dead. Then think about your true purpose, the heart of why you want to tell this story, and what it will take, creatively speaking, to fulfil your purpose responsibly ��� which is to say properly ��� without cowardice or sloppiness. Use that to guide you in working out your personal rule-book: what you feel comfortable with in fictionalising away from the recorded facts; how deep you let yourself go inside these imagined and real-historical heads; how strongly you want to evoke historically- and ethnically-inflected voices.

But that still leaves the question of how not to tread on toes. To think about general principles, let���s imagine that Earthling colonisers took over Saturn in a couple of centuries of genocidal, Martian-slave-importing fervour. Is a modern Earthling-descendant, arguably still benefitting from that historical dominance, entitled to write as if from inside the life of a fictional Martian, and about real-historical Saturnians and mixed-planet Martio-saturnians?

Unquestionably, the command to "Write what you know" is one route to authentic and creatively responsible writing, and it���s true that you can���t in that sense "know" the experience of being inside a different ethnicity. But we all have many identities, and anyway, neither ethnicity, nor sex, gender, sexuality, class, age, religion, education, nationality, disability, language and even marital status are necessarily binary. You may not have ethnicity in common with your protagonists, but you will have many other things which are just as much part of their truth: look for the truths that you do know.

And don���t forget that, by definition, the story of a novel never actually happened, however close it is to the un-reclaimable historical events that did. So the only viable command for fictioneers is actually,"Write what you like, and make me believe that you know it." If a good writer can make dragons believable, or Thomas Cromwell sympathetic, then anything is possible, and who that writer is, is arguably beside the point.

But that doesn���t mean you can ignore the practical writerly dangers. For what it���s worth, when my Saturnian friends grumble about how badly Earthling writers write Saturnian history and people, the ���badly��� seems to come under broad headings:

The Saturnian and Martio-saturnian characters are all the old, familiar stereotypes. By definition even neutral or positive stereotypes ��� that all Martio-saturnian miners on Saturn were wonderfully musical, hymn-singing Presbyterians ��� are off-the-peg characters and can���t come alive for us: there will be nothing individual, fresh or new about this second-hand package of characteristics. You must refuse to buy any character off-the-peg, but imagine them from the ground up, complete with nuance and newness.

If the stereotypes are negative ones of a historically oppressed group they���re particularly likely to offend, and particularly important to watch for, and interrogate. Notice that I don���t say necessarily "to avoid". Historical accuracy or authenticity to the range of human nature may demand them: the fact that Earthling colonisers and their descendants consistently stereotyped Saturnians as tight-fisted or melancholic doesn���t mean that no Saturnian was ever such a thing.

But if you can���t help having a character who conforms to an established negative stereotype, it���s worth trying to undercut it with something less stereotyped - a Martio-saturnian who is indifferent to music - and to balance them with others who run directly and convincingly counter to that: make some Saturnians open-handed and sanguine - and see if you can find some jazz-singing Roman Catholic miners there too.

The characters are just Saturnian in a superficial way, for modishness, or as a cheap bit of bolt-on characterisation. The easy, obvious name-checks , brand-names and cultural symbols have been plucked straight from Wikipedia and other pre-filtered sources, and the writer hasn't properly dug into the culture, and worked at the individuality and nuance of what being fully Saturnian ��� or Martio-saturnian ��� means for who they are and how they act.

What the writer knows or has researched of Martians on Mars, or Martio-earthlings on Earth - perhaps because there are many more sources, or they're more easy to read - is imported directly and applied to Martio-saturnians on Saturn, despite the fact that there are two centuries of different experience behind them, a different legal context, and significantly different culture. It's like researching the culture of Jane Austen's Bath and using it to write a story set in the Moscow of War and Peace.

Every single minute of every single scene among Saturnians and Martio-saturnians is about The Issues. Perhaps in an effort to make sure he/she takes the issues seriously, the writer has lost sight of the fact that sometimes Saturnians are just people having dinner or sex, or disembowelling enemies or sewing curtains. This is particular egregious if your scenes among Earthlings, on the other hand, are about all sorts of "just people" things, not particularly to do with The Issues of being an Earthling.

Earthling characteristics and attitudes are the norm and default ��� which often means taken-for-granted and not evoked. Meanwhile the Saturnians and Martio-saturnians are all busily evoked as Other, even when the point-of-view is ostensibly Saturnian. It may be an attractive, exotic Other, but their voices, clothes, food, colouring, manners and attitudes are always commented-on, and dealt with in terms of their difference from that unremarked-on norm.

All the Saturnians and Martio-saturnians are painted as angels. The writer���s motivation may be pure ��� or simply fearful of the Twitter mobs ��� but as well as being dull storytelling, it���s also offensive, it could be argued, not to grant Saturnians the full fictional-human right that you have granted your Earthlings to be villainous, stupid, awkward or just smelly.

The Too-Long-Didn't-Read version of all the above, of course, is that ethical writing and good writing involve the same processes of care, research, detailed imagining, and ruthless self-editing, just as unethical writing and bad writing are both caused by the writer being slipshod, lazy or unimaginative.

So, how might you avoid these traps, and write something which you feel ethically comfortable with, and so able to ignore the shrieks of calling-out from the loonier fringes of the Twitterverse?

Be sure ��� I know you are, Tony ��� that you are telling this story for honest and responsible reasons, and because you respect the experience of those on whom you���re basing it.

"Research till your eyes bleed", as writer Emily Gale , puts it, and that includes not only material facts, but the points of view, experience, voices and direct testimonies of Saturnians, Martians, Martio-saturnians... and Earthling-descendants, because the original sources and voices have nuance and complexity that the bulk cultural memory, and the websites, has sifted out.

Walk many miles in those shoes ��� or bare, calloused feet ��� imaginatively speaking. It���s not just responsible and respectful, it also helps you creatively: the wider the range of stories, responses and attitudes you can find, the more material you have to choose between, and the more nuance and individuality you���ll be able to draw on. Again, good writing and ethical writing involve the same processes.

If you���re really worried, ignore the censor to let your first draft flow, and later double-check:

Seek out a sensitivity reader - and if the word spikes anyone's blood-pressure, take a chill-pill. Any male writer with any sense, writing a childbirth scene from the point of view of any woman, let alone the one on the birthing-stool (no, in many cultures it's not a bed) would seek out a woman who's been there and pushed that, and ask for feedback. That's sensitivity reading: just another form of essential feedback. In your case, Tony, you'd be looking for an experienced Saturnian or Martian reader or editor who will reflect back to you their experience of how that group is evoked in your novel.

Remember that your sensitivity-reader does not have censorship rights (unless the book's under contract and your editor decides they do). It's your book and your rules, and besides, no one person can represent whole of any group (no one can), especially not its history. You have to be the ultimate creative arbiter of what you do with any feedback, but this should open your eyes to what you, as an Earthling-descendant, just don���t know about being a Saturnian or Martio-saturnian, living on colonial or post-colonial Saturn.

If you are anxious about being "called out" about fictionalising real people, then put an Historical Note at the end, to make clear where you���ve deviated from the record or imagined into its spaces.

And, finally, hold on to your confidence that fiction works by evocation, possibility and imaginative recreation, to tell a story that never (in the strictly literal sense) happened. Your job is not to represent the current arguments about history and ethnicity, or even the historical record of them, except to the extent that it serves your storytelling.

And, one last thought: when it comes to non-fiction arguments about fiction, you don���t have to listen to, let alone pander to, anyone who doesn���t understand the difference.

June 3, 2018

Being Published Part 3: Permissions

This is the third in a series of posts which I'm planning in the run-up to next February, when This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin will be published. In each post, I'll try to shed a bit of light not only on the practicalities of what happens when your book is being published, but also the sometimes surprising ways that this stage of the writing life can affect you and your writing. Part 1: Contracts is here. and Part 2: Editing is here.

I've had to get permissions for all my books, starting with various epigraphs and quotes in my fiction. Get Started in Writing Historical Fiction had a good hundred quotes in it, because how can you write about writing without quoting it? - but see below for the kind of quoting, called "Fair Dealing", which you don't need permission for. This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin, which is all right on the quote front - it's almost all Fair Dealing - nonetheless has lots of portraits and pictures in it, which do need permissions cleared. So here goes. As ever, we'll start with what this might mean for your creative work, and then move on to the practicalities.

WHAT'S THIS "PERMISSIONS" THING ALL ABOUT?

When we say "permissions", what we mean is permission to use, in your published work, a part or the whole of a piece of writing or an image which has been created by someone else and is still in copyright. Copyright is all about intellectual ( as opposed to physical) property: your story is your intellectual property, as the words or pictures that you want to use are the property of their creators. The laws of intellectual property are therefore trying to strike a balance between two often opposing needs. The world would be a poorer place if any creator without a private income starved because they didn't get paid for their work - and most people's sense of social justice includes the idea that workers are entitled to be paid for their work. On the other hand, all art and craft takes place in a cultural context, and it would also be the poorer if artists couldn't draw on that cultural material, which will include art and craft created by other artists.

So, whether your book or story uses song lyrics to evoke a night's clubbing or a romantic idyll; or you have quotations as epigraphs; or one character quotes Ian Fleming/McEwan to another; or your memoir includes photographs; or you've found a perfect picture for the cover of your self-published novel... you need to think about permissions:

which you need - see below for more about this

where to get them - because, generally speaking, the writer clears the permissions

whether you'll be able to afford them - because, generally speaking, the writer pays for the permissions

Of those three, the first is the only one in your control: it's perfectly possible to write a book, and have it published, without needing to ask permission for anything - either because you use nothing, or because everything you use is thoroughly and provably out of copyright. But assuming that's not the case, then it's well worth understanding early what you might be letting yourself in for.

In the following do bear in mind that I'm not a lawyer, and that intellectual property law is complex and very specialist, and so the high street solicitor who did such a good job on your will is not the person to ask either. Instead, the Society of Authors (more book-oriented) or Writers' Guild (more script-oriented) or the US Author's Guild should be your first stop; your publisher should also be able to advise you.

You don't need permission to type an in-copyright quotation into your novel-in-progress, or to mess around with a cover-design using a lower-resolution image off the internet. But since you will need permission for the published thing, it's much easier to think about complying with the law while the project is still malleable and you can find creative ways round any difficulties. It's also asking for trouble - as in endless hassle and last-minute panic - not to keep a clear list, right from the start, of the quotation(s) or images you use, and where you found them.

Permissions are one of the first things your publisher will want to get on with, and so your editor will ask you about. That's partly because permissions can take ages: copyright holders can be hard to track down, and cost a fair bit, though surprisingly often they cost nothing. But what's really important is that

in law, your publisher is liable for any breaches of copyright in your book, and can be sued. So

your contract will include a clause where you indemnify the publisher against them being sued. i.e. if in your novel Andy quotes two lines of "Heart of Grass", without you getting permission, and Blondel sues for breach of copyright and wins, your publisher can come after you for both the damages and costs awarded to Blondel, and (as far as I know) their own costs.

your publisher will therefore insist on you taking this issue seriously; I suggest making sure you send them a clear list of everything you've used, and how/where the permission must be obtained.

Welcome, in other words, to the real world of being an author: it's law, and it's business. But it's worth bearing in mind that a quotation might not be the best way to do the job you're hoping it does.

At the simplest level, remember that swathes of readers don't read epigraphs, just as they don't read chapter numbers, or dates or times in sub-headings, and even those who do read may only skim; I know this, because by default I'm one of them. If the epigraph from A Hard Day's Night is going to cost a lot, or that poet will take you days to track down, does it really add enough to the book to be worth it?

But storytelling, too, comes into it. It may or may not matter whether the reader recognises a line about what your Mum and Dad do to you - though if they don't some air may go out of the joke, and I explored here what's going on when readers don't get a reference. It may or may not matter to the story whether they know it's by Philip Larkin, let alone get a reference to Hull, or to libraries, unless you make it clear. And the making-clear needs to be un-clunky, for the sake of those who do know: author-splaining is a minor insult to the reader. But again, are the cost and the hassle of obtaining the permission, and the necessary 'splaining, worth it?

But at least with prose or a poem, in principle the words are sufficient unto themselves: if they express something you want expressed, better than you can, and make extra layers and connections, then maybe you do want them. That's far, far less true of song-lyrics, because they were written to be integrated with a tune, and when read, on their own, on the page, at most they can only supply half the effect. Even assuming your reader recognises the song, that doesn't mean the music will play in their head, or at least not without them stopping and working it out like a pub quiz question. There's an odd parallel here with brand-names of, say, cars or clothes: on the page a song-lyric, arguably, is a shorthand you hope is embodying all sorts of other things - both the physical properties (the tune, the snarl of a Harley-Davidson) and the cultural properties (the Heavy Metal world, the Establishmentness of Aquascutum). Not everyone can read the shorthand well enough to feel the embodied thing - and some can't read it at all.

Paraphrasing or referring to a quotation is fine. For example - "We talked about being teenagers, and I mentioned what your Mum and Dad do to you, even when they don't mean it" - would not land you in copyright trouble, and "She put 'Heart of Grass' on the turntable, and it struck me that this kind of love wasn't a gas at all" should be fine too.

THE PRACTICALITIES OF GETTING PERMISSIONS

For the Society of Authors' basic guide to copyright and permissions, click here: it's free for anyone to download. It outlines at least some of the differences in US law, and includes a model copyright permission letter, and lists of places to search for copyright owners. More detailed advice is available to members (so what do you mean, you've been offered a book contract or an agency agreement, and you're not a member...?) I therefore won't go into all the details here, just I'll just flag up some basic points and common misconceptions.

Basics: In the UK and the European Community, copyright lasts for 70 years from publication, or after the death of the author, whichever is later. Copyright applies to unpublished work too: for manuscripts, letters, diaries etc. it's basically still life-plus-70, but there are some fiddly little rules for authors who are already dead. US copyright law is different, and more complicated, so don't assume it's the same.

The fact that something in copyright has been reproduced on the internet, with or without permission, does not affect its copyright status: you will still need to get permission for your purposes. And in the UK at least, the idea of something "being in the public domain" doesn't have any legal standing worth hoping for. Either something is in copyright, or it isn't.

It's "the estate" of a dead author which holds the copyright for that last 70 years; the owners may be family, but the estate may be administered by a literary agent, or the author's publisher.

Copyright exists in the text or image, even if the physical object is owned by someone else. So the painting, photograph or portrait above your uncle's fireplace might make the perfect book cover, but unless when he bought it the artist specifically assigned reproduction rights to him (or to the sitter in the portrait) you will need the artist's permission to reproduce it. Same goes for letters and diaries: the recipient of the letter may own the physical object, but it's still the writer of the letter who must grant permission for it to be quoted. Note that if you're reproducing the actual image of the page, say, the publisher holds their own copyright, separately, in the specific arrangement of the text on the page in that edition.

You must ask permission to use any "substantial" extract: "Substantial" is as much about the importance of this chunk to the overall work, as it is about numbers of words, and is not defined in law. A couple of lines of a poem or song-lyric are certainly substantial, and the key sentences from a long book's argument might be too. If the context in which you want to use the quote doesn't come clearly under Fair Dealing, the only safe course is to ask permission for everything. Even if you don't think it's substantial your publisher will almost certainly refuse to risk it, since lawyers are far better paid than authors or publishers.

There is no copyright in facts or ideas, only in the form - the words and pictures, and I think graphs and grids - that the idea is embodied in. In a landmark case, two of the three authors of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail sued Dan Brown, claiming that The DaVinci Code breached their copyright. No one denied that the novel drew on historical facts and deductions that the non-fiction book, among other books, laid out, but the Holy Blood authors lost the case; the judge explicitly said that copyright does not extend to giving an author of a book "exclusive property rights" over the "information, facts, ideas, theories and themes in it."

Plagiarism may be a moral and ethical crime, but it is not a legal one: the issue is always about copyright. Riffing, satirising, morphing or messing about with someone else's work to create a new one may or may not be a breach of copyright: see Fair Dealing, further down. But pastiches, spinoffs and the like may also be a breach of an author's moral rights, (which are a legal right asserted on the copyright page) not to have their work treated derogatorily, and not to have other people's work attributed to them: it is possible for the author to sue if those rights are breached. Fan-fic, for example, has some very grey legal areas indeed.

There is no copyright in titles, or the names of shops, companies or places: you can write "We sat and watched A Hard Day's Night, then wandered over to Harrods", and whoever owns Lennon & McCartney's rights, or the shop, can't do a thing. The moment you quote a line from the film, or reproduce the shop's name in its trademarked visual form or (I think) its slogan, for example, you need permission. Companies can get very shirty, though, if you use their name in a context which suggests that they're unethical or bad in some other way. And, again, their pockets are deeper than yours.

There is no copyright in characters, as they count as ideas... except when there is copyright in a character, which is more likely in the US. The Society of Authors' Nicola Solomon (who in a previous job advised the third author of Holy Blood, who didn't sue - good call!) explains more here. Nor is there copyright in ordinary names: "Harry Potter" is too short to be protected by copyright so is only trademarked in specific visual forms; apparently "Peter Rabbit" is trademarked too.

Translations: there is copyright in both the original text, and the translation, and you may have to seek two sets of permission. And an out-of-copyright work may still be in copyright. If you're lucky, the information will be on the copyright page of the book, but if you found the quote in something else, the translator may not be credited. That happened to me in The Mathematics of Love: the original French book has never been published in English, and my source was a line I'd found in a history of photography published decades ago by the BBC with the author un-credited. Balking at trying to extract an answer from Auntie Beeb, I got the French original and a big dictionary out of the library, used the published translation as a crib, and did my own; my reward was that I could make the quote fit my themes even better than the original had. Try Project Gutenberg for out-of-copyright translations of classic works.

Don't forget quotes in your narrative or dialogue: Having had all that drama with The Mathematics of Love's epigraph, I clean forgot that at one point I'd made my photographer Theo relay something that Robert Capa said, which was actually a line I borrowed from Capa's memoir Slightly Out of Focus. TMOL was about to go to print, so thank God for the internet: I found Capa's estate, which was owned by his brother Cornell Capa, and the administrator whizzed back a formal email overnight giving permission - and didn't even charge me, bless him. But, don't be like Emma, or you might end up with Emma's heart-rate that day...

Who does the legwork: Basically, clearing permissions is the author's job, and (see above) your contract promises your publisher you will do it. Having said that, your publisher may be willing to help, especially if the books you want to quote are published by another part of the same overall company. But this is one of many reasons to have been very practical and record-keep-y about all these things.

Who pays: If you're lucky, the publisher, but generally speaking the author. If you're not being offered an advance, then bargain hard for the publisher to pay, so that you're not out of pocket; at the very least they should put the money up front, and then take it out of your royalties.

Who to ask: with many things, it should be obvious. If you get stuck, that Society of Authors download has a list of places to go looking for copyright holders.

For quoting from books, the publisher of the original edition is your first port of call; they probably have anthology and quotation rights by contract, so even if you know the author personally, they can't necessarily give you clearance. And note, too, that if you quote your own work in another book, you will still need permission from the publisher of that book. The publisher should have a standard setup for handling this - often a form on the website - and a scale of fees. If the book is no longer in print, as far as I know the rights will have reverted to the author.

With journalism and photojournalism it's much more usual for the newspaper or magazine to routinely own the copyright for work it commissioned, so be prepared to track the mag down. It's is no longer published, its copyrights will have been assigned to some entity - but who? With luck, it'll be an existing company, or an archive.

For film and TV scripts, start with the production company, and start saving, for similar reasons to song-lyrics

For play texts, start with whoever owns the performing rights

Quoting song-lyrics is notoriously expensive: a very small amount is likely to count as "substantial", and with the destruction of other revenue streams, music companies are desperate to make money wherever they can. Blake Morrison has described how he was asked ��500 to quote one line of "Jumpin' Jack Flash". Essentially, the best advice for pop lyrics is: Don't.

Pictures are complicated: Galleries and museums should be like publishers in having a well-organised system, but can in addition charge you fees for the cost of digitising the image, or lending it to you to be reproduced. What seems to be a grey area is that even reproducing a Rembrandt is not straightforward, since he is very out-of-copyright, but because they control the physical object, the museums seem to be able to control who and how the image is reproduced. However, Wikimedia Commons may be able to help: at least some of the uploaded files are decent resolution, and every page details what you are allowed do with the image (which varies), and the form the acknowledgement must take.

What to explain: The copyright owner probably will want to know

what the book is: fiction, non-fiction, academic, educational

what you want to quote from

exactly what and how many words you'll be quoting

who your publisher is

the territories it will be sold in

the approximate number of copies in the first edition

Fees: pieces of string come to mind, and there's nothing you can do about it. It may be nothing, or a flat fee, or may depend on all the variables above. For what it's worth, in A Secret Alchemy, which was to be published in all English Language territories, I wanted to quote two lines from a Noel Streatfeild novel; the publisher wanted ��125. Editor friends say that the charge for the Streatfeild was on the high side, but I was skint, so I paraphrased it instead. On the other hand for Get Started in Writing Historical Fiction, with its educational purpose, Routledge asked nothing for a similar-length quote from Jerome de Groot's The Historical Novel. Some publishers have a standard length below which they don't charge.

Acknowledgements: you will have to acknowledge the copyright holder for giving you permission, and in the form of words they require. This is a different kind of acknowledgement from the small essays in life-writing that the authors' personal acknowledgements have become, and can be very small print, buried at the back of the book.

When you don't need permission: "fair dealing" and "fair use": Fair Dealing is the UK version, Fair Use is the slightly less restrictive US version. In the cause of not restricting the creative and practical needs of artists and scholars too much, there is a very specific, though slightly fuzzy-edged, set of rules about when you can quote from existing in-copyright texts for creative and/or educational purposes, without first getting permission. Again, there's more advice in the Society of Authors download, but to sketch out the Fair Dealing principles:

it only applies to work which has been already published with the consent of the copyright holder

you must use no more than is required for your specific purpose. The old definition of "for the purpose of criticism or review, or reporting current events" has been widened, at least a bit.

it must be genuinely used as a quotation, not just silently borrowed to save you having to make new words up

it must be properly acknowledged

the amount used must be reasonable and appropriate to your purpose

it should not affect the market for the original work, or substitute for it

in parody, caricature or pastiche, you must use only "limited, moderate" amounts, and it must not infringe the original author's moral rights

As an example: in Get Started in Writing Historical Fiction I did not have to get permission in advance to quote texts that I wanted to discuss or explain: I only had to make sure they were properly credited in the acknowledgements. But the Teach Yourself creative writing books also include boxed, standalone inspiring quotes about writing (the brief says "inspirational", but I'd rather cut my throat) in each chapter. For those, my editor did ask me to get specific clearance, as they were not obviously down in among the discussion - and I negotiated a budget, in case I needed to pay for the permissions.

And that's it. It probably sounds very complicated - and it can be, if what you're determined to do is very specific - but it's also about being a grown-up writer. And it's really not difficult to cope with the basics; what's more it's often possible - even sometimes creatively fruitful - to find workarounds for the rest. And, y'know, do as you would be done by. If you'd be furious that someone, without asking you, borrowed your words, or your garden produce, or your dog, and made or saved money out of them without asking you and, if you wanted it, paying you some of that money, then ... you work it out.

May 18, 2018

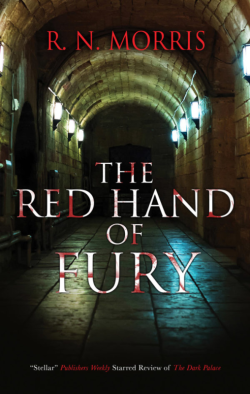

Guest Post by R.N.Morris: Plotting the Perfect Crime (Novel)

R.N.Morris is an old writer-friend of mine, and ever since his debut, A Gentle Axe, starring Dostoevsky's Porfiry Petrovitch, the examining magistrate from Crime and Punishment, I've known his work for pulling no punches but also being subtle, complex and thought-provoking. Has a superb sense of setting and period and (which isn't the case with every good writer) he's also good at articulating what he does. I'm not a crime-writer, though I love the detective/mystery end of the genre particularly, and am awed by anyone who can fit all the bits together and simultaneously make one care, shiver, and stay up late to find out whodunnit. So when I heard Roger had a new book out, I thought it would be a good moment to ask him to unpick a little of his personal how/what/why in writing fiction, for the Itch.

***

Let���s face it, writing novels is a strange occupation for a grown-up. (It���s just making up stories, after all.) But if that���s the case, then writing crime novels is even stranger. After all, as crime writers, we spend a lot of our time trying to work out how one person might kill another and get away with it. I mean to say, is that normal? Is it healthy?

Let���s face it, writing novels is a strange occupation for a grown-up. (It���s just making up stories, after all.) But if that���s the case, then writing crime novels is even stranger. After all, as crime writers, we spend a lot of our time trying to work out how one person might kill another and get away with it. I mean to say, is that normal? Is it healthy?

Friends and family do tend to look at you in a different way once they���ve read one of your books. As if you���re not quite the person they thought you were, and you might actually be capable of the things you���ve written about. The former will almost certainly be true ��� the latter? Well, isn���t that the point of crime fiction, to suggest that we might all be capable of more than we care to admit?

Where does all that darkness come from? you can almost hear them thinking. It���s a question that���s worth pondering.

The wellsprings for dark stories are the same as those for any story, I believe. Fundamentally, it���s to do with characters. Characters who want things and need things. In crime novels, some of these characters are prepared to do all sorts of unspeakable acts to get what they desire. It���s about motivation, in other words.

It���s about conflict too. Crimes often come about because one character is frustrated in achieving what they desire. And the obstacle that is blocking them is another character���s contrary wishes. In a non-crime novel, this conflict might be resolved in any number of ways. A third character might act as a catalyst to bring the two antagonists together. Or neither character might end up getting what they want, but somehow, inadvertently, they might help each other get what they need ��� and through that come to a greater understanding of themselves.

But we���re talking about crime novels here. In a crime novel ��� the kind of crime novel I write ��� conflict is usually resolved through violence. Violence that often results in death.

The mental funnel. The process of how you get to the specific idea ��� the crime ��� that is at the core of your book probably varies from writer to writer. For me, it starts with a mental funnel into which I pour all sorts of things. I write a particular kind of crime fiction, historical mysteries, so a lot of what I put into that funnel is to do with the period and place that my stories are set.

I then watch to see what drips out of the funnel, one detail at a time. Inevitably, something will catch my attention. The germ of an idea that will grow into a story.

Sometimes it can be quite abstract. My Silas Quinn series of novels is set in London on the eve of the First World War. My idea was to pack into a relatively short period of time a set of horrific crimes that would serve somehow as a harbinger of the wholesale carnage to come. In the first of those novels, Summon Up The Blood, I also wanted to explore the theme of sacrifice and also acknowledge the shadow cast by the Jack the Ripper murders. So I came up with a serial killer who preyed on male prostitutes. Attitudes to homosexuality at the time, as well as the history of male prostitution, were some of the things that I fed into my mental funnel. It���s probably fair to say that in this case I already had the idea ��� in the form of a theme ��� I just needed to find a way to make it concrete.

Sometimes it can start with a single image. For example, in my novel A Gentle Axe, it was a body found hanging from a tree in a snowy St Petersburg park, with a second body in a suitcase on the ground nearby.

Whodunit, howdidtheydunit, whydidtheydunit? That image set me a puzzle which I then spent the rest of the novel unpacking. Who was the body hanging from the rope? Had he committed suicide? If so, why? What was the connection between the first dead body and the second? The first part of the plotting process was to ask myself as many questions as possible and work out the answers to them. Some of the questions required quite ingenious ��� and even devious ��� answers. But I think I got to them by the simple, if not brutal, exercise of logic.

Logic can be a heartless method, as we know from Sherlock. When I was dealing with the lives ��� and deaths ��� of my characters I had to lay my pity to one side. That would come later. That was for the reader to bring to the story. But of course, for that to happen, there had to be enough in the story for the reader to respond to. So paradoxically ��� and clandestinely - I had to maintain my empathy at all times. Deep down, I had to know that I was treating my characters appallingly, all the while that I was doing it. It���s another aspect of the splinter of ice in the heart that Graham Greene considered an essential part of the writer���s armoury.

The first task of a storyteller is to keep readers reading. And one of the great ways of doing that is through suspense. You reveal as little as possible and keep the reader guessing. The question and answer formula comes in handy here too. I actually use it as a system for constructing my stories ��� to think of the story as a series of questions. Except every question is answered by��� another question. Until you get to the denouement. And even then, perhaps, some questions have to go unanswered. Though it helps if you have the big one, whodunit, already worked out!

***

R.N.Morris is the author of eight historical crime novels which have been nominated for both Historical and Gold Daggers at the Crime Writers Association. After the Porfiry Petrovich series he moved from 1860s Moscow to London on the eve of the First World War, and began the Silas Quinn series: the latest, The Red Hand of Fury is just out. He is also the author of a standalone contemporary novel, Taking Comfort, and an opera libretto, When the Flame Dies (that's a great trailer, by the way!). Roger studied Classics at Cambridge, and on the days he isn't writing novels, he works as a copywriter.

R.N.Morris is the author of eight historical crime novels which have been nominated for both Historical and Gold Daggers at the Crime Writers Association. After the Porfiry Petrovich series he moved from 1860s Moscow to London on the eve of the First World War, and began the Silas Quinn series: the latest, The Red Hand of Fury is just out. He is also the author of a standalone contemporary novel, Taking Comfort, and an opera libretto, When the Flame Dies (that's a great trailer, by the way!). Roger studied Classics at Cambridge, and on the days he isn't writing novels, he works as a copywriter.

May 12, 2018

All the Posts on Getting Published that I Mentioned @ClaphamBookFest...

... and a few I forgot in the excitement. If there's one I mentioned there and haven't remembered here, or you can't find via the Tool-Kit link up there in the right-hand corner, do say in the comments and I'll try to dig it up.

With many thanks to Philip Gwyn Jones for being so fascinating and informative about publishing from the publisher's point of view, and the lovely team at the Clapham Book Festival, and the Omnibus Theatre for all the organising, and for the delectable chocolates (from MacFarlane's Deli, since you ask...)

For more about my forthcoming memoir This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin click the link.

The WordsAway Writers' salons are held at the Tea House Theatre in Vauxhall Gardens, once a month.

BEING PUBLISHED PART 1: CONTRACTS : First in a series about both practicality and psychology, in the publishing process, from the writer's' point of view.

BEING PUBLISHED PART 2: EDITING : Second in the series about both practicality and psychology in the publishing process, from the writer's point of view.

WHAT IS LITERARY FICTION? : for writers, for readers, for the industry.

CROSSING GENRES: The Perils and Pleasures : being rejected because your book is "neither one thing nor the other"? A exploration of the issues.

HOW TO PRESENT A MANUSCRIPT : these are the industry standards. They're not difficult, they exist for very good reasons, and you'd be mad not to follow them.

SURVIVING THE SUBMISSION BLUES : A post about an inevitable, but not much discussed, part of any serious writer's life.

COMMITTING TO WRITING: Should you, could you, "go for it"? All the questions to ask yourself

HOPING TO MAKE A LIVING WRITING BOOKS? : A realistic picture of the models that (sometimes) work, and the ones that really don't.

BUT CAN YOU TEACH CREATIVE WRITING? : What does a CW teacher do, and is that better than a trainee writer going it alone?

WRITING COURSES: the pros and cons : Should you do one? Which one? When?

SHOULD I DO A CREATIVE WRITING MA : What might it do for my writing? How do I choose?

There are lots more posts about everything from Showing and Telling to how to present a manuscript in The Itch of Writing Tool-Kit, which you can also reach from the link in the top right-hand corner of every page.

May 9, 2018

You love writing: should you, could you, commit to it?

So the writing's going well. You've realised you're happier writing than doing anything else; you've re-found the confidence you had in your childhood and teenage years; you're a nicer and better person in the rest of your life for having those hours on your own with your words. Perhaps you've had successes in getting short things published or placed in competitions, or a self-publishing venture is doing much better than the average sold-it-to-my-family numbers. Maybe, even, an agent or three have said they can't sell this book, but they'd love to see the next one.

Writing is no longer just an amusing hobby, then: this seems to matter to you, and there's a place you want to go with it - not necessarily a book contract, but certainly a greater focus, a larger purpose, a body of work of some sort. But to do that would take more time and energy than your present arrangements allow: could you - should you - commit more of yourself and your life to your writing? Dare you go for it?

There can be no blanket answer, of course. So, just as with my questions to ask your novel, your description, or your voice(s), this post is about pointers to thinking, not about answers.

For a start, what does "go for it" mean to you? Doing a course that costs significant time and money? Cutting down on your working hours? Withdrawing the parent-taxi service? Taking over the box room and installing your desk and a "Gone Writing" sign? Insisting that your elderly parents get Meals on Wheels? Getting up at 5am and writing till your partner gets back from her night shift and you can go to work? Choosing not to get a new puppy when aged Fido finally breathes his last? Or just putting the iron and ironing board on eBay?

How much do you already go for it? There's a strong argument that the thing you should be doing is the thing you already keep finding yourself doing. Do you already look at your diary for the week and pencil in writing time, or do you just hope it will show up somewhere and then mostly it doesn't? You may only have ten minutes a day or an hour a month to write in - but do you defend that hour like a tiger? If there's nothing planned this weekend, do you start clearing the garage or WhatsApping friends, or do you switch off your phone and get on with the writing? When life has made writing impossible for a time, is writing the first thing you go back to when the rest eases off?

What have you already given up in order to write more? Money, time in the gym, time with the children or partner, socialising, sleep, serious cooking or house-enhancing, other creative arts? It's not that you must already be ruthless in these things, but it's one pointer that your first reaction to wonderful invitations, exciting domestic improvements, or the Bake-off urge to make more and better cakes is, "No, I need to revise that story." If you can't resist setting the novel aside for those other things, then how likely are you to resist setting it aside in favour of fun, when it's claimed even more of your time?

Do you keep going back to writing? Even if your life is full of genuine, unavoidable responsibilities and emergencies, does the current project go on nagging at you, so that you do grab time to write when you can? Do you act in some way - a course, a book, a forum - that will help to develop your writing, and then see that through, rather than just being a course junkie? Is your work focused on actually completing (however slowly) a project worth completing, that teaches you something worth learning. Do you grit your teeth and workshop it a second time, make notes about what didn't work ready for the next project, submit it somewhere - and then somewhere else?

What is supporting your belief that it would be worth going for? Everyone has the absolute right, of course, to choose to take their writing seriously. And we all hope for someone in life whose validation is unconditional: the friend who says "Just send it. I love everything you write"; the partner who supports your passion for writing Fantasy though the only book she ever reads is a Haynes Manual. But if you're seeking any kind of audience for your writing, either from sheer desire or to justify the costs of committing to it, then the fact that writing matters to you, that you're happier writing than doing anything else, that you feel grumpy and scratchy when you can't write, is not enough data to make that decision. In other words, what kind of conditional validation have you had? Who, beyond your mother and your lovely supportive friends, has told you, reasonably clearly, that your writing speaks to them, that they like reading it, that it has power? Has anyone with whom you don't have a direct relationship suggested that although getting things published will still be hard, your writing is of a publishable standard? What competitions have long-listed you, what have you had published in something which exercises some editorial sifting and control?

Are you making progress already? Wobbles of confidence aside, is this year's writing quite often a bit better than last year's? Is one thing that makes you choose a new writing project the fact that you don't know how to tackle it, or whether it'll be any good, but you'll have a bloody good try? Did you come out of a course a better writer (after perhaps an ugly duckling phase) than you were before? To gain anything from a bigger commitment you'll need the capacity to learn.

How resilient is your writerly confidence? The more of your life you commit to the goal of writing seriously, the more you have at stake. There isn't a writer on the planet who isn't sometimes convinced that they're hopeless (Neil Gaiman's is my favourite version of this), and of course it's unsurprising that rejections may make any of us doubt what we do - but so can having your work out on submission, and even a success can trigger a bout of imposter syndrome. All psychologists and physiotherapists know health isn't about never getting ill, it's about how you recover from illness. So how well do you climb back out of the slough of despond? How do you recover from the cringing conviction that you were (and looked!) a fool to even try that magazine or that agent. How quickly and successfully do you manage to pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and get going again?

Will you have support for your new determination? That might be financial - your partner picking up the shortfall in the drop in household income - or practical: the children accepting that the box room is not their playroom any more. But it's also psychological. Friends and family who resent your absence, or feel their own failures more acutely when they see you actually doing something about your ambitions, might not dream of overtly sabotaging you. But when they try to talk you down to the pub, or consistently have crises shortly after you've closed your writing door, that's what they're doing, just as the friend is who pushes you to have a glass of wine when you're doing Dry January. Even the generous friend who offers their spare-room or shed for your study may also be longing for a chat; are you willing and able to keep your boundaries solid, and shut the door?

Are you plagued by procrastination? Many, many writers find that when they finally manage to clear the acres of time for writing that they'd always longed to have, they write no more than they did when it was squeezed into non-existent gaps of time. Giving things up to write raises the stakes placed on your writing, and many writers find that pressure messes with their writerly compass or wakes their inner rebellious teenager. But procrastination has many causes, and correspondingly many, at least partial, solutions.

Are you realistic about what you might (eventually) earn, in return for this investment in your time and your self? Dreams are lovely - necessary, even, to keep us going - but hopes need to take account of the real world to have a chance of being fulfilled.

Do you have a fallback position or a Plan B? You might find you can't make the money you need, or write well what you want to write, or get what you can write well actually published. You might get feedback that makes you realise you need to learn far, far more about writing than you'd thought. Or you might find simply that the writing life really doesn't suit you. If so - what would you do instead, both practically and psychologically, to find a new path?

What do you value about the act and nature of the writing process? As will become clear in my series on Being Published, any kind of serious work to find an audience, and validation for what you write, changes your relationship to your writing. Thousands of writers have had two books published (or the equivalent in other forms) and no more; for each who spends the rest of their life bitter and frustrated than they've never been offered another contract, there is a writer who (perhaps after a certain wailing and gnashing of teeth) realises they are profoundly glad, because now they're free to recapture the unconditional joy that was why they loved writing in the first place.

I hope all of those questions are helping you to think these things out. But please, please do remember something which it's very difficult to hang on to in our Western, success-worshipping age, where we are supposed to give "one hundred and ten percent", and the sort of obssessive-compulsive behaviour that it takes to be a great sports or film star is an ideal, not a regrettable necessity.

That last question is a clue: there's no shame - there should be honour - in deciding that you love doing something, and you will do it as part of your existing life, setting it aside sometimes, and taking it up again at others. Remember that "amateur" means "lover", and "dilettante" means "one who delights in something". I take photographs and writing poems on that basis; I know what it would take to develop them to a professional level - I did do the equivalent with writing, after all - and I choose, instead, to stay with love and delight. Taking anything worth doing more seriously - committing to it - means giving up other things that you might be doing or having, and those are good things too.

Finally - the more carefully you have thought about it all, the easier it is to commit wholeheartedly to whichever road you take. And not only are you then more likely to travel further and take more pleasure in the journey, you're less likely to regret whichever choice you made, back there, in the yellow wood.

April 25, 2018

Being Published Part 2: Editing

This is the second in a series of posts which I'm planning in the run-up to next February. (Did I mention that my memoir This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin will be published on 12th February next year by Holland House Books? No, surely not!). In each post, I'll try to shed a bit of light not only on the practicalities of what happens when your book is being published, but also the sometimes surprising ways that this whole part of the writing life can affect you and your writing. Part 1: Contracts, is here.

BEING EDITED

If you've ever had good, experienced feedback on your work, in some ways being edited by a publisher isn't that different. It can even be better, because a professional editor's basic duty is to help you write the book that you thought you'd already written - and why wouldn't you want someone to do that? But a publisher's editor must also embody your potential readers: the thousands who they hope will hand over the cash that will pay back what your publisher has just paid you. This is closer and sharper than you've probably ever been to the detail of how publishers stay solvent: and your book is part of that how.

And it's not only about that: your editor is your main interface with the whole publishing house. They will be your book's chief champion, gingering up publicity, sales, marketing and everyone to be excited about it and do their best for it - and they'll champion it outwards, too, to booksellers and journalists. An editor is up there with the person marking your MA portfolio in terms of the power they have over the fate of your work.

So it's important to maintain a good relationship with your editor, so that each of you can exercise your respective expertises - theirs as a reader and seller of your book, yours as the writer - and integrate them on the page. Since you do need to stay something like friends, while also being prepared to kick up a stink with your editor if the publisher is really falling down on the job, it helps enormously to have an agent, who can have those fights on your behalf.

But you are entitled to your expertise, and so it's not a matter of just "doing what you're told"; it's your book, and your job to find the right solutions to the problems that your editor raises. What you can't do is ignore those problems, since they are problems that will make readers not like your book; but how you solve them may very well not be the solution your editor first proposes. You may find my posts on how to handle feedback useful, and the Fiction Editors Pharmacopoeia might help you decode what the more baffling kinds of feedback say into something you can act on.

All the authors I know are profoundly grateful for being well-edited - and most would say that although the Gordon Lish degree of intervention is pretty much unheard of nowadays (which may not be a bad thing) it's simply not true that "no one edits any more". But that's not to say it's always comfortable. Being edited can feel a bit like having teacher mark your work, and thereby stir up some dormant teenaged wiring you thought you'd long outgrown - and not every editor "gets" every book they work on as the writer would wish. So it's important to remember that this is collaboration: the aim is to have an editorial conversation which results in a better and more saleable book than either you, or your editor, could have created on your own.

THE PRACTICALITIES OF BEING EDITED

Who will edit you? It's probably an acquisitions editor or senior editor who acquired - as in, bought - your book, and they may well go on to work with you on it, and to champion it throughout its life. However, it may be that your book was bought by an editorial director, say, or the acquiring editor leaves, and your editor will be someone else. There may also be an in-house desk editor, experienced but more junior, or an editorial assistant, (which is where all editors started) who's in charge of tracking all the stages and processes, the communication with different departments, the freelances who are used, and so on. In a small publisher one person may do all those jobs, and any of them may be done by freelancers: it's especially common for your copy-editor to be freelance.

Editorial Processes. Traditionally, there are several separate editing stages, and there is overlap between them, so that it's quite possible to combine the structural and line edit, for example. Exactly what your publisher does will depend on both them, and your book, but it's still useful to understand the nature of the different kinds of editing you should get.

The Structural Edit. This is all about the storytelling: the shape and pace; the order of events, and the order that the events are told in; the development of characters and themes and the resolving of plotlines; the overall voice; the choice of viewpoint characters and the moves between them, and so on. If the book was finished when the publisher bought it there may not be much of this, since it was the rightness of these things which made them want it in the first place. With a book written under contract, (or one where the voice and the premise are so amazing the publisher's taken a gamble on sorting out the plot and bought it anyway) it's likely there will be a good deal more.

The structural edit is most likely to come back to you in the form of notes, or even an editorial conversation with a follow-up email, and then you will get to work. Specific references will be given as line numbers: "p.6 l.14: sounds a bit grown-up for a 6yr old"; "p.264 l.8 up [i.e. from the bottom]: but what about the trip to Skye?" so make sure you're working on a matching manuscript (I think you can even set Word to show line-numbers?).

The Line Edit. This is all about how the big storytelling issues play out line by line: picking up where the voice wobbles, or any surplus explaining and "filtering". Are there point-of-view slips or places where things aren't clear? Are characters' voices consistent? Are settings earning their keep in enhancing the mood and theme? Are there any little gaps or contradictions in what people say or do? This is immensely slow and focused work; in the best book I know on this stuff, The Forest for the Trees: an editor's advice to writers, editor Betsey Lerner says that the fastest she can do this is about five or six pages an hour. Fortunately, with a traditional publishing deal you won't be paying for it. And it can only be done by someone who already knows the book, picking up these things in the light of what the book's trying to be.