Chris Eboch's Blog, page 19

March 16, 2016

Editing Your Novel during #NaNoEdMo – Editing Tips

In honor of #NaNoEdMo (National Novel Editing Month), I'm sharing some advice from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Two weeks ago I offered advice on “big picture” editing. Last week I covered Fine Tuning. Here are some final quick tips on editing to help you through NaNoEdMo.

In honor of #NaNoEdMo (National Novel Editing Month), I'm sharing some advice from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Two weeks ago I offered advice on “big picture” editing. Last week I covered Fine Tuning. Here are some final quick tips on editing to help you through NaNoEdMo.Editing Tips:

Don’t try to edit everything at once. Make several passes, looking for different problems. Start big, then focus in on details.

Try writing a one- or two-sentence synopsis. Define your goal. Do you want to produce an action-packed thriller? A laugh-out-loud book that will appeal to preteen boys? A richly detailed historical novel about a character’s internal journey? Identifying your goal can help you make decisions about what to cut and what to keep.

Next make a scene list, describing what each scene does.Do you need to make major changes to the plot, characters, setting, or theme (fiction) or the focus of the topic (nonfiction)?Does each scene fulfill the synopsis goal? How does it advance plot, reveal character, or both?Does each scene build and lead to the next? Are any redundant? If you cut the scene, would you lose anything? Can any secondary characters be combined or eliminated?Does anything need to be added or moved? Do you have a length limit or target?Can you increase the complications, so that at each step, more is at stake, there’s greater risk or a better reward? If each scene has the same level of risk and consequence, the pacing is flat and the middle sags.Check for accuracy. Are your facts correct? Are your characters and setting consistent?Does each scene (in fiction) or paragraph (in nonfiction) follow a logical order and stick to the topic?Is your point of view consistent?Do you have dynamic language: Strong, active verbs? A variety of sentence lengths (but mostly short and to the point)? No clichés? Do you use multiple senses (sight, sound, taste, smell, touch)?Finally, edit for spelling and punctuation.

(For detailed editing questions, see my Plot Outline Exercise. It’s in my book Advanced Plotting or available as a free Word download on my website.)

Editing Description

For each detail, ask:

Does it make the story more believable?Does it help readers picture or understand a character or place better?Does it answer questions that readers might want answered?Does it distract from the action?Could it be removed without confusing readers or weakening the story?For illustrated work, could the description be replaced by illustrations?

Use more details for unusual/unfamiliar settings. Try using multiple senses: sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and the feeling of touch. Especially in picture books, use senses other than sight, which can be shown through the illustrations.

Editing Resources:Print/Ebook

Advanced Plotting

, by Chris EbochSelf-Editing for Fiction Writers, by Renni Browne and Dave KingStyle That Sizzles & Pacing for Power – An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction, by Jodie RennerManuscript Makeover, by Elizabeth LyonNovel Metamorphosis, by Darcy PattisonRevision & Self-Editing, by James Scott BellThanks, But This Isn’t For Us, by Jessica Page Morrell

Editing Resources:Print/Ebook

Advanced Plotting

, by Chris EbochSelf-Editing for Fiction Writers, by Renni Browne and Dave KingStyle That Sizzles & Pacing for Power – An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction, by Jodie RennerManuscript Makeover, by Elizabeth LyonNovel Metamorphosis, by Darcy PattisonRevision & Self-Editing, by James Scott BellThanks, But This Isn’t For Us, by Jessica Page MorrellOnline I haven’t tried this, but the “Hemingway App” is designed to identify overly long or complicated sentences, so it might be helpful in learning to simplify your work for younger audiences:

Grammarly is a free app that claims to find more errors than Microsoft Word’s spelling and grammar check option, including words that are spelled correctly but used incorrectly:

Resources for Writers, by editor Jodie Renner, list several of her editing books as well as blog posts on various writing topics.

The Plot Outline Exercise from Advanced Plotting helps you analyze your plot for trouble spots. (It’s available as a free Word download on my website, in the left-hand column of this page.)

Middle grade author Janice Hardy’s Fiction University blog has great posts on many writing craft topics.

Author and writing teacher Jordan McCollum offers downloadable free writing guides on topics such as character arcs and deep point of view.

In “A Bad Case of Revisionitis,” Literary agent Natalie M. Lakosil discusses when to stop revising.

Subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in You Can Write for Children : A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. Advanced Plotting also has advice on editing novels.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with over 30 traditionally published books for children. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page, or check out her writing tips at her Write Like a Pro! blog. Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Chris also writes novels of suspense and romance for adults under the name Kris Bock; read excerpts at www.krisbock.com.

Published on March 16, 2016 05:00

March 9, 2016

Editing Your Novel during #NaNoEdMo – Fine Tuning

In honor of #NaNoEdMo (National Novel Editing Month), I'm sharing some advice from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Last week I offered advice on “big picture” editing. Once you're comfortable with the overall structure and content of your novel, it's time to consider the details.

Fine Tuning Once you are confident that your characters, plot, structure, and pacing are working, you can dig into the smaller details. At this stage, make sure that your timeline works and your setting hangs together. Create calendars and maps to keep track of when things happen and where people go.

Once you are confident that your characters, plot, structure, and pacing are working, you can dig into the smaller details. At this stage, make sure that your timeline works and your setting hangs together. Create calendars and maps to keep track of when things happen and where people go.

Then polish, polish, polish.

Bill Peschel, author of Sherlock Holmes parodies and other books for adults, and a former newspaper copy editor, says, “Reading with a critical eye reveals weak spots in grammar, consistently misspelled words, and a reliance on ‘crutch words’ [unnecessary and overused words] such as simply, basically, or just. While it can be disheartening to make the same mistakes over and over again, self-editing can boost your ego when you become aware that you’re capable of eliminating them from your work. It takes self-awareness, some education, and a willingness to admit to making mistakes.”

This stage of editing can be time-consuming, especially if you are prone to spelling or grammatical errors. “Be systematic,” Peschel says. “Despite all the advice on how to multi-task, the brain operates most efficiently when it’s focusing on one problem at a time. This applies to proofing. You can look for spelling mistakes, incorrect grammar, and your particular weaknesses, just not at the same time. So for effective proofing, make several passes, each time focusing on a different aspects.”

One pass might focus only on dialogue. “Read just the dialogue out loud,” editor Jodie Renner suggests, “maybe role-playing with a buddy or two. Do the conversations sound natural or stilted? Does each character sound different, or do they all sound like the author?”

Wordiness (using more words than necessary) is a big problem for many writers, so make at least one pass focused exclusively on tightening. “Make every word count,” Renner advises. “Take out whole sentences and paragraphs that don’t add anything new or drive the story forward. Take out unnecessary little words, most adverbs and many adjectives, and eliminate clichés.” Words you can almost always cut include very, really, just, sort of, kind of, a little, rather, started to, began to, then. To pick up the pace in your manuscript, try to cut 20% of the text on every page, simply by looking for unnecessary words or longer phrases that can be changed to shorter ones.

Wordiness (using more words than necessary) is a big problem for many writers, so make at least one pass focused exclusively on tightening. “Make every word count,” Renner advises. “Take out whole sentences and paragraphs that don’t add anything new or drive the story forward. Take out unnecessary little words, most adverbs and many adjectives, and eliminate clichés.” Words you can almost always cut include very, really, just, sort of, kind of, a little, rather, started to, began to, then. To pick up the pace in your manuscript, try to cut 20% of the text on every page, simply by looking for unnecessary words or longer phrases that can be changed to shorter ones.

Make additional passes looking for grammar errors, missing words, and your personal weak areas. For example, if you know you tend to overuse “just,” use the “Find” option in a program like Microsoft Word to locate that word and eliminate it when possible.

Even if you’re not an expert editor, you may be able to sense when something is wrong. “Trust your inner voice,” when you get an uneasy feeling, Peschel says. “It can be something missing, something wrong, something clunky, and if you stick to it – read it out loud, read it backwards, look at it from a distance – the mistake should declare itself.”

Fool Your Brain

By this point, you’ve read your manuscript dozens of times. This can make it hard to spot errors, since you know what is supposedto be there. Several tricks can help you see your work with fresh eyes.

By this point, you’ve read your manuscript dozens of times. This can make it hard to spot errors, since you know what is supposedto be there. Several tricks can help you see your work with fresh eyes.

Peschel says, “Reading the same prose in the same font can cause the eye to skate over mistakes, so change it up. Boost the size or change the color of the text or try a different font. Use free programs such as Calibre or Scrivener to create an EPUB or MOBI file that can be read on an ebook reader.”

Renner also recommends changing your font. Print your manuscript on paper if you are used to working on the computer screen. Finally, move away from your normal working place to review your manuscript. “These little tricks will help you see the manuscript as a reader instead of as a writer,” she says.

“An effective way to check the flow of your story is to read it aloud or have someone read it to you,” freelance editor Linda Lane notes. “Better yet, record your story so you can play it back multiple times if necessary. Recruiting another person to do this will give you a better idea of what a reader will see.” Some software, such as MS Word 2010, has a text-to-voice feature to provide a read aloud.

“An effective way to check the flow of your story is to read it aloud or have someone read it to you,” freelance editor Linda Lane notes. “Better yet, record your story so you can play it back multiple times if necessary. Recruiting another person to do this will give you a better idea of what a reader will see.” Some software, such as MS Word 2010, has a text-to-voice feature to provide a read aloud.

Lane adds, “If recording your story yourself, run your finger just below each line as you read to catch omitted or misspelled words and missing commas, quote marks, and periods. Also, enunciate clearly and ‘punctuate’ as you read, pausing slightly at each comma and a bit longer at end punctuation. While this won’t catch every error, it will give you a good sense of flow, highlight many shortcomings, and test whether your dialogue is smooth and realistic.”

Some people even recommend reading your manuscript backwards, sentence by sentence. While this won’t help you track the flow of the story, it focuses attention on the sentence level. Finally, certain computer programs and web platforms are designed to identify spelling and grammar errors, and in some cases even identify clichés. While these programs are not recommended for developmental editing (when you’re shaping the story), they can be an option for later polishing. (They can also make mistakes, though, so don’t trust Microsoft Word’s spelling & grammar check to be right about everything.)

How Much Is Enough?

How much editing you need to do depends on your goals for the story. If you simply want to write down the bedtime stories you tell your children as a family record, a spelling error or two doesn’t matter too much. If you are going to submit work to a publisher, you need to be more careful. Some editors and agents say they will stop reading if they find errors in the first few pages, or more than one typo every few pages. If you plan to self-publish, most experts advise hiring a professional editor to help you shape the story and a professional proofreader to make sure the book doesn’t go out with typos. Weak writing and other errors could cause readers to get annoyed and leave bad reviews.

Looking at all the steps to successful self-editing may be daunting, but break them down into pieces, take a step at a time, and don’t rush your revisions. “This whole process could easily take several months,” Renner says. “Don’t shoot yourself in the foot by putting your manuscript out too soon.”

Each time you go through this process you’ll be developing your skills, making the next time easier. “Like anything else, self-editing becomes easier the more you do it,” Peschel says. “When it becomes second-nature, you’ll have made a big leap toward becoming a professional writer.”

Stop by next Wednesday for final tips on editing – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with over 30 traditionally published books for children. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page. Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Chris also writes novels of suspense and romance for adults under the name Kris Bock; read excerpts at www.krisbock.com

Fine Tuning

Once you are confident that your characters, plot, structure, and pacing are working, you can dig into the smaller details. At this stage, make sure that your timeline works and your setting hangs together. Create calendars and maps to keep track of when things happen and where people go.

Once you are confident that your characters, plot, structure, and pacing are working, you can dig into the smaller details. At this stage, make sure that your timeline works and your setting hangs together. Create calendars and maps to keep track of when things happen and where people go. Then polish, polish, polish.

Bill Peschel, author of Sherlock Holmes parodies and other books for adults, and a former newspaper copy editor, says, “Reading with a critical eye reveals weak spots in grammar, consistently misspelled words, and a reliance on ‘crutch words’ [unnecessary and overused words] such as simply, basically, or just. While it can be disheartening to make the same mistakes over and over again, self-editing can boost your ego when you become aware that you’re capable of eliminating them from your work. It takes self-awareness, some education, and a willingness to admit to making mistakes.”

This stage of editing can be time-consuming, especially if you are prone to spelling or grammatical errors. “Be systematic,” Peschel says. “Despite all the advice on how to multi-task, the brain operates most efficiently when it’s focusing on one problem at a time. This applies to proofing. You can look for spelling mistakes, incorrect grammar, and your particular weaknesses, just not at the same time. So for effective proofing, make several passes, each time focusing on a different aspects.”

One pass might focus only on dialogue. “Read just the dialogue out loud,” editor Jodie Renner suggests, “maybe role-playing with a buddy or two. Do the conversations sound natural or stilted? Does each character sound different, or do they all sound like the author?”

Wordiness (using more words than necessary) is a big problem for many writers, so make at least one pass focused exclusively on tightening. “Make every word count,” Renner advises. “Take out whole sentences and paragraphs that don’t add anything new or drive the story forward. Take out unnecessary little words, most adverbs and many adjectives, and eliminate clichés.” Words you can almost always cut include very, really, just, sort of, kind of, a little, rather, started to, began to, then. To pick up the pace in your manuscript, try to cut 20% of the text on every page, simply by looking for unnecessary words or longer phrases that can be changed to shorter ones.

Wordiness (using more words than necessary) is a big problem for many writers, so make at least one pass focused exclusively on tightening. “Make every word count,” Renner advises. “Take out whole sentences and paragraphs that don’t add anything new or drive the story forward. Take out unnecessary little words, most adverbs and many adjectives, and eliminate clichés.” Words you can almost always cut include very, really, just, sort of, kind of, a little, rather, started to, began to, then. To pick up the pace in your manuscript, try to cut 20% of the text on every page, simply by looking for unnecessary words or longer phrases that can be changed to shorter ones.Make additional passes looking for grammar errors, missing words, and your personal weak areas. For example, if you know you tend to overuse “just,” use the “Find” option in a program like Microsoft Word to locate that word and eliminate it when possible.

Even if you’re not an expert editor, you may be able to sense when something is wrong. “Trust your inner voice,” when you get an uneasy feeling, Peschel says. “It can be something missing, something wrong, something clunky, and if you stick to it – read it out loud, read it backwards, look at it from a distance – the mistake should declare itself.”

Fool Your Brain

By this point, you’ve read your manuscript dozens of times. This can make it hard to spot errors, since you know what is supposedto be there. Several tricks can help you see your work with fresh eyes.

By this point, you’ve read your manuscript dozens of times. This can make it hard to spot errors, since you know what is supposedto be there. Several tricks can help you see your work with fresh eyes.Peschel says, “Reading the same prose in the same font can cause the eye to skate over mistakes, so change it up. Boost the size or change the color of the text or try a different font. Use free programs such as Calibre or Scrivener to create an EPUB or MOBI file that can be read on an ebook reader.”

Renner also recommends changing your font. Print your manuscript on paper if you are used to working on the computer screen. Finally, move away from your normal working place to review your manuscript. “These little tricks will help you see the manuscript as a reader instead of as a writer,” she says.

“An effective way to check the flow of your story is to read it aloud or have someone read it to you,” freelance editor Linda Lane notes. “Better yet, record your story so you can play it back multiple times if necessary. Recruiting another person to do this will give you a better idea of what a reader will see.” Some software, such as MS Word 2010, has a text-to-voice feature to provide a read aloud.

“An effective way to check the flow of your story is to read it aloud or have someone read it to you,” freelance editor Linda Lane notes. “Better yet, record your story so you can play it back multiple times if necessary. Recruiting another person to do this will give you a better idea of what a reader will see.” Some software, such as MS Word 2010, has a text-to-voice feature to provide a read aloud. Lane adds, “If recording your story yourself, run your finger just below each line as you read to catch omitted or misspelled words and missing commas, quote marks, and periods. Also, enunciate clearly and ‘punctuate’ as you read, pausing slightly at each comma and a bit longer at end punctuation. While this won’t catch every error, it will give you a good sense of flow, highlight many shortcomings, and test whether your dialogue is smooth and realistic.”

Some people even recommend reading your manuscript backwards, sentence by sentence. While this won’t help you track the flow of the story, it focuses attention on the sentence level. Finally, certain computer programs and web platforms are designed to identify spelling and grammar errors, and in some cases even identify clichés. While these programs are not recommended for developmental editing (when you’re shaping the story), they can be an option for later polishing. (They can also make mistakes, though, so don’t trust Microsoft Word’s spelling & grammar check to be right about everything.)

How Much Is Enough?

How much editing you need to do depends on your goals for the story. If you simply want to write down the bedtime stories you tell your children as a family record, a spelling error or two doesn’t matter too much. If you are going to submit work to a publisher, you need to be more careful. Some editors and agents say they will stop reading if they find errors in the first few pages, or more than one typo every few pages. If you plan to self-publish, most experts advise hiring a professional editor to help you shape the story and a professional proofreader to make sure the book doesn’t go out with typos. Weak writing and other errors could cause readers to get annoyed and leave bad reviews.

Looking at all the steps to successful self-editing may be daunting, but break them down into pieces, take a step at a time, and don’t rush your revisions. “This whole process could easily take several months,” Renner says. “Don’t shoot yourself in the foot by putting your manuscript out too soon.”

Each time you go through this process you’ll be developing your skills, making the next time easier. “Like anything else, self-editing becomes easier the more you do it,” Peschel says. “When it becomes second-nature, you’ll have made a big leap toward becoming a professional writer.”

Stop by next Wednesday for final tips on editing – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with over 30 traditionally published books for children. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page. Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Chris also writes novels of suspense and romance for adults under the name Kris Bock; read excerpts at www.krisbock.com

Published on March 09, 2016 05:00

March 7, 2016

Resources for Diversity in Children's Literature

I'm preparing for an SCBWI Shop Talk on diversity in children's literature. This is the list of "Resources for Diversity" I developed. It is certainly not all-inclusive, but it has places to start. I'm posting it here so that people who attend the talk have live links all in one place. And anyone else is certainly welcome to browse or share!

I'm preparing for an SCBWI Shop Talk on diversity in children's literature. This is the list of "Resources for Diversity" I developed. It is certainly not all-inclusive, but it has places to start. I'm posting it here so that people who attend the talk have live links all in one place. And anyone else is certainly welcome to browse or share!Resources for Diversity:

Chris Eboch’s blog post has links to all of the sites below:http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/2016/0...

SCBWI has a page of Diversity Resources including blogs and websites, awards, organizations and articles: https://www.scbwi.org/diversity-resou...

SCBWI also has grants to promote diversity and children’s books: http://www.scbwi.org/awards/grants/gr...

The Children’s Book Council CBC Diversity shares news encouraging diversity of race, gender, geographical region, sexual orientation, and class: http://www.cbcdiversity.com/

Cynthia Leitich Smith’s blog often touches on diversity or links to articles about it. Her Exploring Diversity page links to book lists about many religions/races, with relevant interviews: http://www.cynthialeitichsmith.com/li...

Multiculturalism Rocks! is a blog celebrating multiculturalism in children’s literature, with many useful links: http://nathaliemvondo.wordpress.com/

We Need Diverse Books promotes changes in the publishing industry to produce literature that reflects all young people: http://weneeddiversebooks.org/

Disability in Kidlit examines the portrayal of disability: http://disabilityinkidlit.com/

Author Lee Wind’s blog lists books with gay teen characters or themes, interviews with agents seeking diverse stories, videos on gender identity, and more: http://www.leewind.org/

DiversifYA “is a collection of interviews that allows us to share our stories, all of us. All sorts of diversity and all marginalized experiences.” http://www.diversifya.com/

Reading While White, a blog by librarians, has interesting blog posts on children's lit subjects, and a page of "Resources for Further Research": http://readingwhilewhite.blogspot.com/

This post on the SCBWI blog links to articles regarding A Birthday Cake For George Washington: http://scbwi.blogspot.com/2016/01/hav...

Mitali Perkins often touches on diversity subjects on her blog: http://www.mitaliblog.com/ A particularly valuable post is “The Danger of a Single Story, Once Again”: http://www.mitaliblog.com/2015/11/the...

“You Will Be Tokenized”: Speaking Out About the State of Diversity in Publishing by Molly McArdle has voices from the front lines: http://tinyurl.com/z2p9sbo

“We’ve Been Out Here Working”: Diversity in Publishing, a Partial Reading List has many links on the subject: http://tinyurl.com/josp8hk

Published on March 07, 2016 05:00

March 2, 2016

Editing Your Novel during #NaNoEdMo – The Big Picture

In honor of #NaNoEdMo (National Novel Editing Month), I'm sharing some advice from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.

The book market is more competitive than ever. Editors with mile-high submission piles can afford to choose only exceptional manuscripts. Authors who self-publish must produce work that is equal to releases from traditional publishers. And regardless of their publishing path, authors face competition from tens of thousands of other books. Serious authors know they must extensively edit and polish their manuscripts.

The book market is more competitive than ever. Editors with mile-high submission piles can afford to choose only exceptional manuscripts. Authors who self-publish must produce work that is equal to releases from traditional publishers. And regardless of their publishing path, authors face competition from tens of thousands of other books. Serious authors know they must extensively edit and polish their manuscripts.

For many writers, a new manuscript is their “baby.” You love it, and it may be hard to think of it as anything less than perfect. But you wouldn’t send your newborn baby out into the world and expect it to survive on its own. You help your children grow up, teaching them, gently correcting misbehavior, and helping them express their wonderful selves. As your children grow older, you can step back a bit and see them as individuals in their own right, separate from you. Once they are grown, you can send them off into the world, perhaps still worrying at times but with confidence that they can survive on their own.

Editing a manuscript is similar. You need to distance yourself enough from the work that you can see it for what it is – not what you dreamed it would be, but what is actually on the page. Then you guide and shape it, perhaps with help from others. You release it into the world when you’re confident the story can survive on its own, without you there to explain or defend it.

The Big Picture

Wading through hundreds of novel pages trying to identify every problem at once is intimidating and hardly effective. Even editing a picture book, short story, or article can be overwhelming if you try to address every issue at once. The best self-editors break the editorial process into steps. They also develop practices that allow them to step back from the manuscript and see it as a whole.

Wading through hundreds of novel pages trying to identify every problem at once is intimidating and hardly effective. Even editing a picture book, short story, or article can be overwhelming if you try to address every issue at once. The best self-editors break the editorial process into steps. They also develop practices that allow them to step back from the manuscript and see it as a whole.

Editor Jodie Renner recommends putting your story away for a few weeks after your first complete draft. During that time, share it with a critique group or beta readers. (Beta readers give feedback on an unpublished draft. They are not necessarily writers, so they give a reader’s opinion.) Ask your advisors to look only at the big picture: “where they felt excited, confused, curious, delighted, scared, worried, bored, etc.,” Renner says. During your writing break, you can also read books, articles, or blog posts to brush up on your craft techniques.

Then collect the feedback and make notes, asking for clarification as needed. Consider moving everyone’s comments onto a single manuscript for simplicity. This also allows you to see where several people have made similar comments, and to choose which suggestions you will follow. At this point, you are only making notes, not trying to implement changes.

In my book Advanced Plotting, I suggest making a chapter by chapter outline of your manuscript so you can see what you have without the distraction of details. For each scene or chapter, note the primary action, important subplots, and the mood or emotions. By getting this overview of your novel down to a few pages, you can go through it quickly looking for trouble spots. You can compare your outline to The Hero’s Journey or scriptwriting three-act structure to see if those guidelines inspire any changes. (Get this Plot Arc Exercise as a free downloadable Word document on my website.)

As you review your scenes, pay attention to anything that slows the story. Where do you introduce the main conflict? Can you eliminate your opening chapter(s) and start later? Do you have long passages of back story or explanation that aren’t necessary? Does each scene have conflict? Are there scenes out of order or repetitive scenes that could be cut? Make notes on where you need to add new scenes, delete or condense boring scenes, or move scenes.

As you review your scenes, pay attention to anything that slows the story. Where do you introduce the main conflict? Can you eliminate your opening chapter(s) and start later? Do you have long passages of back story or explanation that aren’t necessary? Does each scene have conflict? Are there scenes out of order or repetitive scenes that could be cut? Make notes on where you need to add new scenes, delete or condense boring scenes, or move scenes.

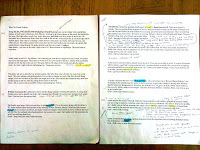

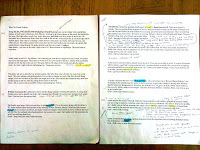

Colored highlighter pens (or the highlight function on a computer) can help you track everything from point of view changes to clues in a mystery to thematic elements. Highlight subplots and important secondary characters to make sure they are used throughout the manuscript in an appropriate way. Cut or combine minor characters who aren’t necessary.

Using Your Notes

Once you have an overview of the changes you want, revise the manuscript for these big picture items: issues such as plot, structure, characterization, point of view, and pacing. Renner recommends you then reread the entire manuscript, still focusing on the big picture. Depending on the extent of your changes, you may want to repeat this process several times.

During this stage of editing, consider market requirements if you plan to submit the work to publishers. Is your word count within an appropriate range for the genre? Are you targeting a publisher that has specific requirements? If you’re writing a romance, will the characters’ arcs and happy ending satisfy those fans? If you have an epic fantasy, is the world building strong and fresh? If your thriller runs too long, can it be broken into multiple books, or can you eliminate minor characters and subplots?

Once you’ve done all you can, you may want to hire an editor. You could also send the manuscript to new beta readers or critique partners. People who have not read the manuscript before might be better at identifying how things are working now. (See my blog posts on Critiques for tips on when and how to use family and friends, other writers, and professional editors for feedback.)

Editing Tips:

Editing Tips:

Don’t try to edit everything at once. Make several passes, looking for different problems. Start big, then focus in on details.

Try writing a one- or two-sentence synopsis. Define your goal. Do you want to produce an action-packed thriller? A laugh-out-loud book that will appeal to preteen boys? A richly detailed historical novel about a character’s internal journey? Identifying your goal can help you make decisions about what to cut and what to keep.

Next make a scene list, describing what each scene does. · Do you need to make major changes to the plot, characters, setting, or theme (fiction) or the focus of the topic (nonfiction)?· Does each scene fulfill the synopsis goal? How does it advance plot, reveal character, or both? · Does each scene build and lead to the next? Are any redundant? If you cut the scene, would you lose anything? Can any secondary characters be combined or eliminated? · Does anything need to be added or moved? Do you have a length limit or target?

· Can you increase the complications, so that at each step, more is at stake, there’s greater risk or a better reward? If each scene has the same level of risk and consequence, the pacing is flat and the middle sags.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with over 30 traditionally published books for children. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Chris also writes novels of suspense and romance for adults under the name Kris Bock; read excerpts at www.krisbock.com.

The book market is more competitive than ever. Editors with mile-high submission piles can afford to choose only exceptional manuscripts. Authors who self-publish must produce work that is equal to releases from traditional publishers. And regardless of their publishing path, authors face competition from tens of thousands of other books. Serious authors know they must extensively edit and polish their manuscripts.

The book market is more competitive than ever. Editors with mile-high submission piles can afford to choose only exceptional manuscripts. Authors who self-publish must produce work that is equal to releases from traditional publishers. And regardless of their publishing path, authors face competition from tens of thousands of other books. Serious authors know they must extensively edit and polish their manuscripts. For many writers, a new manuscript is their “baby.” You love it, and it may be hard to think of it as anything less than perfect. But you wouldn’t send your newborn baby out into the world and expect it to survive on its own. You help your children grow up, teaching them, gently correcting misbehavior, and helping them express their wonderful selves. As your children grow older, you can step back a bit and see them as individuals in their own right, separate from you. Once they are grown, you can send them off into the world, perhaps still worrying at times but with confidence that they can survive on their own.

Editing a manuscript is similar. You need to distance yourself enough from the work that you can see it for what it is – not what you dreamed it would be, but what is actually on the page. Then you guide and shape it, perhaps with help from others. You release it into the world when you’re confident the story can survive on its own, without you there to explain or defend it.

The Big Picture

Wading through hundreds of novel pages trying to identify every problem at once is intimidating and hardly effective. Even editing a picture book, short story, or article can be overwhelming if you try to address every issue at once. The best self-editors break the editorial process into steps. They also develop practices that allow them to step back from the manuscript and see it as a whole.

Wading through hundreds of novel pages trying to identify every problem at once is intimidating and hardly effective. Even editing a picture book, short story, or article can be overwhelming if you try to address every issue at once. The best self-editors break the editorial process into steps. They also develop practices that allow them to step back from the manuscript and see it as a whole.Editor Jodie Renner recommends putting your story away for a few weeks after your first complete draft. During that time, share it with a critique group or beta readers. (Beta readers give feedback on an unpublished draft. They are not necessarily writers, so they give a reader’s opinion.) Ask your advisors to look only at the big picture: “where they felt excited, confused, curious, delighted, scared, worried, bored, etc.,” Renner says. During your writing break, you can also read books, articles, or blog posts to brush up on your craft techniques.

Then collect the feedback and make notes, asking for clarification as needed. Consider moving everyone’s comments onto a single manuscript for simplicity. This also allows you to see where several people have made similar comments, and to choose which suggestions you will follow. At this point, you are only making notes, not trying to implement changes.

In my book Advanced Plotting, I suggest making a chapter by chapter outline of your manuscript so you can see what you have without the distraction of details. For each scene or chapter, note the primary action, important subplots, and the mood or emotions. By getting this overview of your novel down to a few pages, you can go through it quickly looking for trouble spots. You can compare your outline to The Hero’s Journey or scriptwriting three-act structure to see if those guidelines inspire any changes. (Get this Plot Arc Exercise as a free downloadable Word document on my website.)

As you review your scenes, pay attention to anything that slows the story. Where do you introduce the main conflict? Can you eliminate your opening chapter(s) and start later? Do you have long passages of back story or explanation that aren’t necessary? Does each scene have conflict? Are there scenes out of order or repetitive scenes that could be cut? Make notes on where you need to add new scenes, delete or condense boring scenes, or move scenes.

As you review your scenes, pay attention to anything that slows the story. Where do you introduce the main conflict? Can you eliminate your opening chapter(s) and start later? Do you have long passages of back story or explanation that aren’t necessary? Does each scene have conflict? Are there scenes out of order or repetitive scenes that could be cut? Make notes on where you need to add new scenes, delete or condense boring scenes, or move scenes.Colored highlighter pens (or the highlight function on a computer) can help you track everything from point of view changes to clues in a mystery to thematic elements. Highlight subplots and important secondary characters to make sure they are used throughout the manuscript in an appropriate way. Cut or combine minor characters who aren’t necessary.

Using Your Notes

Once you have an overview of the changes you want, revise the manuscript for these big picture items: issues such as plot, structure, characterization, point of view, and pacing. Renner recommends you then reread the entire manuscript, still focusing on the big picture. Depending on the extent of your changes, you may want to repeat this process several times.

During this stage of editing, consider market requirements if you plan to submit the work to publishers. Is your word count within an appropriate range for the genre? Are you targeting a publisher that has specific requirements? If you’re writing a romance, will the characters’ arcs and happy ending satisfy those fans? If you have an epic fantasy, is the world building strong and fresh? If your thriller runs too long, can it be broken into multiple books, or can you eliminate minor characters and subplots?

Once you’ve done all you can, you may want to hire an editor. You could also send the manuscript to new beta readers or critique partners. People who have not read the manuscript before might be better at identifying how things are working now. (See my blog posts on Critiques for tips on when and how to use family and friends, other writers, and professional editors for feedback.)

Editing Tips:

Editing Tips:Don’t try to edit everything at once. Make several passes, looking for different problems. Start big, then focus in on details.

Try writing a one- or two-sentence synopsis. Define your goal. Do you want to produce an action-packed thriller? A laugh-out-loud book that will appeal to preteen boys? A richly detailed historical novel about a character’s internal journey? Identifying your goal can help you make decisions about what to cut and what to keep.

Next make a scene list, describing what each scene does. · Do you need to make major changes to the plot, characters, setting, or theme (fiction) or the focus of the topic (nonfiction)?· Does each scene fulfill the synopsis goal? How does it advance plot, reveal character, or both? · Does each scene build and lead to the next? Are any redundant? If you cut the scene, would you lose anything? Can any secondary characters be combined or eliminated? · Does anything need to be added or moved? Do you have a length limit or target?

· Can you increase the complications, so that at each step, more is at stake, there’s greater risk or a better reward? If each scene has the same level of risk and consequence, the pacing is flat and the middle sags.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with over 30 traditionally published books for children. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Chris also writes novels of suspense and romance for adults under the name Kris Bock; read excerpts at www.krisbock.com.

Published on March 02, 2016 05:00

February 24, 2016

Nonfiction Truths: Finding Your Theme in Nonfiction

Writers tend to talk about theme less than they talk about characters, plot, and even setting. When theme does come up, it's usually with fiction. Yet identifying a theme can even help in writing powerful nonfiction.

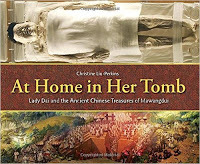

Writers tend to talk about theme less than they talk about characters, plot, and even setting. When theme does come up, it's usually with fiction. Yet identifying a theme can even help in writing powerful nonfiction. Christine Liu-Perkins, author of At Home in Her Tomb: Lady Dai and the Ancient Chinese Treasures of Mawangdui, says, “My book is about a set of 2,100-year-old tombs in China that had over 3,000 well-preserved artifacts, including the body of a woman. I decided to write about the tombs as a time capsule, the various artifacts revealing what life was like during that period. Coming up with a theme really helped me develop the focus and content for my nonfiction book, and also helped in pitching my proposal to the publisher.”

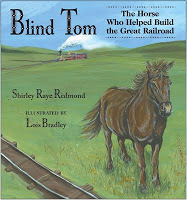

Shirley Raye Redmond gives another example. “Before writing my first draft of

Blind Tom: The Horse Who Helped Build theGreat Railroad

(Mountain Press Publishing), I narrowed the focus of my story and identified my story theme by answering the following questions as thoroughly as possible: who, what, when, where, how and why? I then abbreviated my answers so they fit concisely on an index card. On the back of the card, I wrote my theme statement: With perseverance, ordinary people (and even a blind horse) can play important roles in shaping major historical events. I kept my ‘focus card’ where I could see it as I drafted—and later refined—my story.”

Shirley Raye Redmond gives another example. “Before writing my first draft of

Blind Tom: The Horse Who Helped Build theGreat Railroad

(Mountain Press Publishing), I narrowed the focus of my story and identified my story theme by answering the following questions as thoroughly as possible: who, what, when, where, how and why? I then abbreviated my answers so they fit concisely on an index card. On the back of the card, I wrote my theme statement: With perseverance, ordinary people (and even a blind horse) can play important roles in shaping major historical events. I kept my ‘focus card’ where I could see it as I drafted—and later refined—my story.” For my fictionalized biography of Olympic runner Jesse Owens, I considered the various lessons of his life in order to focus the book. Because he overcame ill health, racism, poverty and a poor education to become one of the greatest athletes the world has known, a theme quickly presented itself: Suffering can make you stronger, if you face it with courage and determination.

For my fictionalized biography of Olympic runner Jesse Owens, I considered the various lessons of his life in order to focus the book. Because he overcame ill health, racism, poverty and a poor education to become one of the greatest athletes the world has known, a theme quickly presented itself: Suffering can make you stronger, if you face it with courage and determination. With this in mind, I chose to open the book when Jesse was five, and his mother cut a growth from his chest with a knife. I ended the chapter with his father saying, “If he survived that pain, he’ll survive anything life has to offer. Pain won’t mean nothing to him now.” Jesse shows that spirit again and again throughout Jesse Owens: Young Record Breaker (Simon & Schuster), written under the name M. M. Eboch. Identifying that theme helped me craft a dramatic story, and may even inspire kids to tackle their greatest challenges.

In your theme, you can find the heart of your story. It’s your chance to share what you believe about the world, so take the time to identify and clarify your theme, and make sure your story supports it. Through your messages, you may influence children, and perhaps even change lives.

Subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.Chris Eboch is the author of You Can Write for Children : A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Published on February 24, 2016 05:13

February 17, 2016

Getting Started In Educational Publishing Work for Hire

Last week I provided an overview of educational publishing. Today I’ll go into more detail about how to get “work for hire” (WFH). This article was originally published in Children’s Book Writer. Publishing professionals mentioned may have changed jobs, so please do your research before submitting any work.

To be considered for WFH assignments, most publishers request a resume, a list of previous publications, and a writing sample. At ABDO, Hedlund says, “We want to know what you are interested in writing about and what makes you qualified to write for that area – education or avid interests are helpful.”

To be considered for WFH assignments, most publishers request a resume, a list of previous publications, and a writing sample. At ABDO, Hedlund says, “We want to know what you are interested in writing about and what makes you qualified to write for that area – education or avid interests are helpful.”

Bender Richardson White accepts submissions from potential authors, but networking can be more valuable than writing samples. “Overall, I use authors I have met and know,” Bender says, “those that come as recommendations, and those that I track down and get to know. At book fairs, book exhibitions, and writers’ conferences such as SCBWI, I am always on the lookout for new authors to extend our range. For specialist subjects, I will seek out authors via the Yahoo Group NFforKids, or by reviewing books on the market and tracking down the authors via the internet.” Note – Bender is one of the organizers of the 21st Century Children’s Nonfiction Conference, June 10-12, at Iona College, New Rochelle, New York!

When writing for a series, individual titles must fit perfectly with the overall series, so writers may be asked to write a targeted sample. “I definitely like to see a sample at whatever grade level we are asking for before we go forward with a project,” Heller says. “If there is an outline available, I ask them to write off that, just to make sure the writer really has a grasp on the voice and tone for the individual project. It also helps to have a list of some previous work-for-hire experience to see what might be a good fit.”

When writing for a series, individual titles must fit perfectly with the overall series, so writers may be asked to write a targeted sample. “I definitely like to see a sample at whatever grade level we are asking for before we go forward with a project,” Heller says. “If there is an outline available, I ask them to write off that, just to make sure the writer really has a grasp on the voice and tone for the individual project. It also helps to have a list of some previous work-for-hire experience to see what might be a good fit.”

Building up to Steady Work

Breaking in can be a challenge, but a successful first project can lead to steady work. “We are lucky to have a core group of writers that have worked on many of our series for some time,” Heller says. “We consult with other editors as well to see if they have worked with good and reliable freelance writers.”

Whether writing nonfiction or fiction, the best work for hire writers are flexible and have a broad range of skills. “We love it if a work-for-hire writer is able to write across age-ranges,” Heller says. “It opens up more possibilities for both them and us if they can transition from chapter-book to middle-grade, for example.”

Whether writing nonfiction or fiction, the best work for hire writers are flexible and have a broad range of skills. “We love it if a work-for-hire writer is able to write across age-ranges,” Heller says. “It opens up more possibilities for both them and us if they can transition from chapter-book to middle-grade, for example.”

Duke shares additional WFH tips. “Be willing to revise and do what’s necessary and what the editor asks promptly. Meet your deadlines. Don’t be needy or a pest. Be professional and make your emails short and to the point. Ask questions early on if there’s something you need to know about the assignment. Make the subject line of emails specific. Make the editor’s work easier in any way you can by doing your job well.”

Why write for hire? Get published and release more booksHone your writing skillsFind new opportunitiesWrite on diverse topicsGet to know the editors and work with themBooks are published quicklyMost companies pay quicklyOpens the door to school visits for pay

Get published and release more booksHone your writing skillsFind new opportunitiesWrite on diverse topicsGet to know the editors and work with themBooks are published quicklyMost companies pay quicklyOpens the door to school visits for pay

Why Not?Short deadlines (often 1 to 6 weeks) require fast writingDetailed research and footnoting requiredYou may need to provide an index, glossary, captions, and sometimes photo researchYou don’t control titles or contentIt takes time away from your own trade writingUsually no royalties

Resources:Writing Children’s Nonfiction Books for the Educational Market, by Laura Purdie SalasYes! You Can Learn How to Write Children’s Books, Get Them Published, and Build a Successful Writing Career, by Nancy I. SandersThe Society of Children’s Books Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) provides a listing of educational publishers to members. The US copyright office has legal information on “Works Made for Hire” online: http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ09.pdf

Stop by next Wednesday for a look at another kind of work for hire, writing for standardized tests – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Stop by next Wednesday for a look at another kind of work for hire, writing for standardized tests – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Chris Eboch is the author of You Can Write for Children : A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

To be considered for WFH assignments, most publishers request a resume, a list of previous publications, and a writing sample. At ABDO, Hedlund says, “We want to know what you are interested in writing about and what makes you qualified to write for that area – education or avid interests are helpful.”

To be considered for WFH assignments, most publishers request a resume, a list of previous publications, and a writing sample. At ABDO, Hedlund says, “We want to know what you are interested in writing about and what makes you qualified to write for that area – education or avid interests are helpful.” Bender Richardson White accepts submissions from potential authors, but networking can be more valuable than writing samples. “Overall, I use authors I have met and know,” Bender says, “those that come as recommendations, and those that I track down and get to know. At book fairs, book exhibitions, and writers’ conferences such as SCBWI, I am always on the lookout for new authors to extend our range. For specialist subjects, I will seek out authors via the Yahoo Group NFforKids, or by reviewing books on the market and tracking down the authors via the internet.” Note – Bender is one of the organizers of the 21st Century Children’s Nonfiction Conference, June 10-12, at Iona College, New Rochelle, New York!

When writing for a series, individual titles must fit perfectly with the overall series, so writers may be asked to write a targeted sample. “I definitely like to see a sample at whatever grade level we are asking for before we go forward with a project,” Heller says. “If there is an outline available, I ask them to write off that, just to make sure the writer really has a grasp on the voice and tone for the individual project. It also helps to have a list of some previous work-for-hire experience to see what might be a good fit.”

When writing for a series, individual titles must fit perfectly with the overall series, so writers may be asked to write a targeted sample. “I definitely like to see a sample at whatever grade level we are asking for before we go forward with a project,” Heller says. “If there is an outline available, I ask them to write off that, just to make sure the writer really has a grasp on the voice and tone for the individual project. It also helps to have a list of some previous work-for-hire experience to see what might be a good fit.”Building up to Steady Work

Breaking in can be a challenge, but a successful first project can lead to steady work. “We are lucky to have a core group of writers that have worked on many of our series for some time,” Heller says. “We consult with other editors as well to see if they have worked with good and reliable freelance writers.”

Whether writing nonfiction or fiction, the best work for hire writers are flexible and have a broad range of skills. “We love it if a work-for-hire writer is able to write across age-ranges,” Heller says. “It opens up more possibilities for both them and us if they can transition from chapter-book to middle-grade, for example.”

Whether writing nonfiction or fiction, the best work for hire writers are flexible and have a broad range of skills. “We love it if a work-for-hire writer is able to write across age-ranges,” Heller says. “It opens up more possibilities for both them and us if they can transition from chapter-book to middle-grade, for example.”Duke shares additional WFH tips. “Be willing to revise and do what’s necessary and what the editor asks promptly. Meet your deadlines. Don’t be needy or a pest. Be professional and make your emails short and to the point. Ask questions early on if there’s something you need to know about the assignment. Make the subject line of emails specific. Make the editor’s work easier in any way you can by doing your job well.”

Why write for hire?

Get published and release more booksHone your writing skillsFind new opportunitiesWrite on diverse topicsGet to know the editors and work with themBooks are published quicklyMost companies pay quicklyOpens the door to school visits for pay

Get published and release more booksHone your writing skillsFind new opportunitiesWrite on diverse topicsGet to know the editors and work with themBooks are published quicklyMost companies pay quicklyOpens the door to school visits for payWhy Not?Short deadlines (often 1 to 6 weeks) require fast writingDetailed research and footnoting requiredYou may need to provide an index, glossary, captions, and sometimes photo researchYou don’t control titles or contentIt takes time away from your own trade writingUsually no royalties

Resources:Writing Children’s Nonfiction Books for the Educational Market, by Laura Purdie SalasYes! You Can Learn How to Write Children’s Books, Get Them Published, and Build a Successful Writing Career, by Nancy I. SandersThe Society of Children’s Books Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) provides a listing of educational publishers to members. The US copyright office has legal information on “Works Made for Hire” online: http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ09.pdf

Stop by next Wednesday for a look at another kind of work for hire, writing for standardized tests – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Stop by next Wednesday for a look at another kind of work for hire, writing for standardized tests – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.Chris Eboch is the author of You Can Write for Children : A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Published on February 17, 2016 05:00

February 10, 2016

Educational Publishing: Steady Work for Career Writers

This article was originally published in Children’s Book Writer. Publishing professionals mentioned may have changed jobs, so please do your research before submitting any work.

When people first dream of writing for children, they typically imagine crafting original novels or picture books. However, few authors can sell enough original work – or earn large enough advances – to support themselves. Many writers who make a living from writing supplement their own projects with writing for hire.

When people first dream of writing for children, they typically imagine crafting original novels or picture books. However, few authors can sell enough original work – or earn large enough advances – to support themselves. Many writers who make a living from writing supplement their own projects with writing for hire.

For writers, the term “work for hire” (WFH) usually means freelance work done as an independent contractor. Most WFH pays a flat fee, although some publishers pay royalties. Payment can range from a few dollars to several thousand dollars, depending on the project.

A contract is necessary to clarify the legal status of the work, including who holds the copyright – usually the employer. A written agreement also clarifies other terms. “Make sure your fee is clear and ask ahead of time about how soon you’ll be paid,” advises Shirley Duke, the author of many nonfiction books. In addition, “Get a contract and check out the publisher or packager to make sure they are reputable. Ask [your colleagues] if anyone has worked for them before.” These precautions ensure a satisfying experience for everyone.

Books for Teaching Kids

Books for Teaching Kids

Educational publishing provides many WFH opportunities for children’s book writers. These books are frequently nonfiction, are often designed for classroom use, and are targeted at specific reading levels. For example, ABDO has three divisions: ABDO Publishing produces nonfiction for grades PreK-12; Magic Wagon produces fiction and nonfiction for grades PreK-8 and includes picture books, beginning readers, graphic novels, and chapter books; Spotlight licenses popular fiction.

Magic Wagon accepts original manuscripts from authors. Stephanie Hedlund, Editorial Director of Magic Wagon and Spotlight, says, “As a series publisher, we want to see an outline of how a submission can be a series of four to six titles.”

Only about 5% of authors are hired through original submissions, however; most ABDO books are developed in-house. “We accept author resumes and review them for work-for-hire assignments,” Hedlund says. “We are always looking to add graphic novel authors and illustrators to our author stable.”

Many educational projects are produced through book packagers. Bob Temple, President of Red Line Editorial, Inc., explains, “The lion’s share of the projects that we handle are complete, beginning-to-end book development projects for educational publishers. We work with publishers to develop ideas, then produce the books using our in-house staff and freelancers, including all editorial and design work.”

Many educational projects are produced through book packagers. Bob Temple, President of Red Line Editorial, Inc., explains, “The lion’s share of the projects that we handle are complete, beginning-to-end book development projects for educational publishers. We work with publishers to develop ideas, then produce the books using our in-house staff and freelancers, including all editorial and design work.”

Book packagers use many freelance authors. “We have a large database of authors who have worked for us in the past, or have been recommended to us, or have sent us their information,” Temple says. “When we have a new project, we search for authors who have experience in the subject matter, reading level, writing style, etc., that the project calls for.”

In this internet era, WFH jobs can come from anywhere in the world. Bender Richardson White is based in the UK but works with American and Canadian publishers. Editorial Director Lionel Bender says the company handles, “Both single titles and series of highly illustrated nonfiction for children grades 2 upward, mostly for the schools and library market but also some trade books.”

In this internet era, WFH jobs can come from anywhere in the world. Bender Richardson White is based in the UK but works with American and Canadian publishers. Editorial Director Lionel Bender says the company handles, “Both single titles and series of highly illustrated nonfiction for children grades 2 upward, mostly for the schools and library market but also some trade books.”

Fiction writers can also find opportunities. Alyson Heller, Associate Editor, Aladdin Books/Simon and Schuster Children’s Publishing, says, “Our work-for-hire projects are mainly with chapter-book and middle-grade works, particularly with our series publishing. We also do some in-house developed original stand-alone titles (also known as IP), and we use work-for-hire writers for those, too.”

Special Skills

While educational publishing can provide steady work, writers must develop specific skills in order to be successful. Classroom nonfiction requires detailed research, often with every fact footnoted. Writers may be required to provide an index, image captions, and extensive back matter, such as a timeline, glossary, additional resources, and more. Some publishers even ask the writers to do photo research.

Writers must also understand reading levels and be able to target them. “The ability to take sometimes difficult concepts and write them at the proper reading level is very important,” Temple says. “The ability to meet deadlines is crucial, as is the ability to communicate well with our staff. Another key skill is the ability to research a topic thoroughly. Also, our deadlines are generally tight, so the ability to do all this with some speed is helpful, too!”

Writers must also understand reading levels and be able to target them. “The ability to take sometimes difficult concepts and write them at the proper reading level is very important,” Temple says. “The ability to meet deadlines is crucial, as is the ability to communicate well with our staff. Another key skill is the ability to research a topic thoroughly. Also, our deadlines are generally tight, so the ability to do all this with some speed is helpful, too!”

“I’m looking for authors with huge imaginations who write quickly and consistently,” Hedlund says. “My favorite authors to work with understand writing for children and are able to get creative but keep the vocabulary, tone, and content for our young readers.”

To work with Bender Richardson White, authors need to accept a detailed brief and follow it closely. Bender also offers a reminder: “You are part of a team, along with the designer, editor, picture researcher, which sometimes means being flexible and compromising.”

Compass Publishing produces educational materials for students learning English as a second or foreign language. These books offer additional challenges, such as writing from a limited vocabulary word list. Senior Editor Casey Malarcher says they like to see writers with, “EFL/ESL teaching experience, experience in writing educational materials, and familiarity with current practices and trends in EFL/ESL instruction.”

Compass Publishing produces educational materials for students learning English as a second or foreign language. These books offer additional challenges, such as writing from a limited vocabulary word list. Senior Editor Casey Malarcher says they like to see writers with, “EFL/ESL teaching experience, experience in writing educational materials, and familiarity with current practices and trends in EFL/ESL instruction.”

Because these books are used in classrooms in Asia, the Middle East, and South America, in addition to multi-cultural classrooms in the U.S., Compass looks for certain kinds of writers, Malarcher explains: “Writers who can envision how their materials are actually applied in classroom settings where both teachers and students may need extensive support and guidance, and writers who are sensitive to cultural aspects of both their work and classroom settings where their work may be used.”

Stop by next Wednesday for more advice on getting started in educational publishing– or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Chris Eboch is the author of

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Chris Eboch is the author of

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers

When people first dream of writing for children, they typically imagine crafting original novels or picture books. However, few authors can sell enough original work – or earn large enough advances – to support themselves. Many writers who make a living from writing supplement their own projects with writing for hire.

When people first dream of writing for children, they typically imagine crafting original novels or picture books. However, few authors can sell enough original work – or earn large enough advances – to support themselves. Many writers who make a living from writing supplement their own projects with writing for hire.For writers, the term “work for hire” (WFH) usually means freelance work done as an independent contractor. Most WFH pays a flat fee, although some publishers pay royalties. Payment can range from a few dollars to several thousand dollars, depending on the project.

A contract is necessary to clarify the legal status of the work, including who holds the copyright – usually the employer. A written agreement also clarifies other terms. “Make sure your fee is clear and ask ahead of time about how soon you’ll be paid,” advises Shirley Duke, the author of many nonfiction books. In addition, “Get a contract and check out the publisher or packager to make sure they are reputable. Ask [your colleagues] if anyone has worked for them before.” These precautions ensure a satisfying experience for everyone.

Books for Teaching Kids

Books for Teaching KidsEducational publishing provides many WFH opportunities for children’s book writers. These books are frequently nonfiction, are often designed for classroom use, and are targeted at specific reading levels. For example, ABDO has three divisions: ABDO Publishing produces nonfiction for grades PreK-12; Magic Wagon produces fiction and nonfiction for grades PreK-8 and includes picture books, beginning readers, graphic novels, and chapter books; Spotlight licenses popular fiction.

Magic Wagon accepts original manuscripts from authors. Stephanie Hedlund, Editorial Director of Magic Wagon and Spotlight, says, “As a series publisher, we want to see an outline of how a submission can be a series of four to six titles.”

Only about 5% of authors are hired through original submissions, however; most ABDO books are developed in-house. “We accept author resumes and review them for work-for-hire assignments,” Hedlund says. “We are always looking to add graphic novel authors and illustrators to our author stable.”

Many educational projects are produced through book packagers. Bob Temple, President of Red Line Editorial, Inc., explains, “The lion’s share of the projects that we handle are complete, beginning-to-end book development projects for educational publishers. We work with publishers to develop ideas, then produce the books using our in-house staff and freelancers, including all editorial and design work.”

Many educational projects are produced through book packagers. Bob Temple, President of Red Line Editorial, Inc., explains, “The lion’s share of the projects that we handle are complete, beginning-to-end book development projects for educational publishers. We work with publishers to develop ideas, then produce the books using our in-house staff and freelancers, including all editorial and design work.” Book packagers use many freelance authors. “We have a large database of authors who have worked for us in the past, or have been recommended to us, or have sent us their information,” Temple says. “When we have a new project, we search for authors who have experience in the subject matter, reading level, writing style, etc., that the project calls for.”

In this internet era, WFH jobs can come from anywhere in the world. Bender Richardson White is based in the UK but works with American and Canadian publishers. Editorial Director Lionel Bender says the company handles, “Both single titles and series of highly illustrated nonfiction for children grades 2 upward, mostly for the schools and library market but also some trade books.”

In this internet era, WFH jobs can come from anywhere in the world. Bender Richardson White is based in the UK but works with American and Canadian publishers. Editorial Director Lionel Bender says the company handles, “Both single titles and series of highly illustrated nonfiction for children grades 2 upward, mostly for the schools and library market but also some trade books.”Fiction writers can also find opportunities. Alyson Heller, Associate Editor, Aladdin Books/Simon and Schuster Children’s Publishing, says, “Our work-for-hire projects are mainly with chapter-book and middle-grade works, particularly with our series publishing. We also do some in-house developed original stand-alone titles (also known as IP), and we use work-for-hire writers for those, too.”

Special Skills

While educational publishing can provide steady work, writers must develop specific skills in order to be successful. Classroom nonfiction requires detailed research, often with every fact footnoted. Writers may be required to provide an index, image captions, and extensive back matter, such as a timeline, glossary, additional resources, and more. Some publishers even ask the writers to do photo research.

Writers must also understand reading levels and be able to target them. “The ability to take sometimes difficult concepts and write them at the proper reading level is very important,” Temple says. “The ability to meet deadlines is crucial, as is the ability to communicate well with our staff. Another key skill is the ability to research a topic thoroughly. Also, our deadlines are generally tight, so the ability to do all this with some speed is helpful, too!”