Chris Eboch's Blog, page 15

May 8, 2017

Cliffhangers in Picture Books #NaPiBoWriWee

If you did NATIONAL PICTURE BOOK WRITING WEEK - #NaPiBoWriWee - with Paula Yoo, you should have manuscripts in progress. Before you submit any, make sure they're as strong as possible.

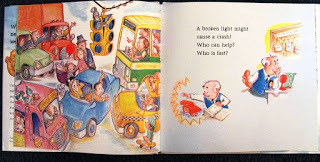

If you did NATIONAL PICTURE BOOK WRITING WEEK - #NaPiBoWriWee - with Paula Yoo, you should have manuscripts in progress. Before you submit any, make sure they're as strong as possible.When we talk about cliffhangers, most people think of the chapter endings in novels. But even a picture book can have a sort of cliffhanger. Take a look at these first few pages from Police Officers on Patrol , by Kersten Hamilton and illustrated by R. W. Alley.

1. Uniform! Badge! Radio! Police Officers, getting ready to go!

2. Squad report—Sergeant Santole. “People need help! Let’s rock and roll!”

3. A broken light might cause a crash! Who can help? Who is fast?

Hey, look at those last two sentences — they make a cliffhanger! The first three pages act as a sort of chapter, ending in the cliffhanger question, “Who will help prevent the crash?” This 144-word picture book has three of these episodes, each with its own cliffhanger. If you write picture books and have been told your work is "Too quiet," or if you have trouble writing a picture book under 1000 words, study Kersten Hamilton to see how much action a skilled writer can pack in to a few words.

Let's look at an even trickier example, a nonfiction picture book, Blind Tom: The Horse Who Helped Build the Great Railroad, written by Shirley Raye Redmond and illustrated by Lois Bradley. This is the story of a blind horse who worked on the transcontinental railroad. Here's an excerpt from a few pages in:

Let's look at an even trickier example, a nonfiction picture book, Blind Tom: The Horse Who Helped Build the Great Railroad, written by Shirley Raye Redmond and illustrated by Lois Bradley. This is the story of a blind horse who worked on the transcontinental railroad. Here's an excerpt from a few pages in: But the workers needed help. They had to move heavy iron rails and spikes, which were piled onto flatcars. The cars were very hard to pull.

What do you suppose could help pull the flatcars?

—Again, a question acts as a cliffhanger. We turn the page to find out the answer...

Horses!

This page continues with some new information, ending in yet another question. The entire narrative follows this kind of question and answer format.

In both these picture book examples, questions act as cliffhangers. If the reader thinks she knows the answer, she'll turn the page to find out if she's right. If she doesn't know the answer, she'll turn the page to find out what it is. Kersten Hamilton notes that with novels, the questions at the chapter ends are implied. With picture books, the author asks the questions outright—you are teaching children how to read and understand a story.

Questions aren't the only possible cliffhangers, of course. Action or other dramatic moments can be used, just as in novels. In Stellaluna , written and illustrated by Janell Cannon, Stellaluna gets separated from her mother. One early page ends like this:

By daybreak, the baby bat could hold on no longer. Down, down again she dropped.

Of course we are going to turn the page to find out where she lands.

Illustrators can use cliffhanger techniques as well. According to another writer, David Weisner said that in his award-winning wordless picture book Flotsam , he used images as cliffhangers. Take a look at the book and see what you think.

Exercise: Grab a stack of published picture books. Go through them slowly, looking for the cliffhanger moments. How many are there? How do they work to encourage the reader to turn the page? If you don't find a cliffhanger, could you rewrite the text to add dramatic tension to certain moments?

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting. Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting. Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page.You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Remember the magic of bedtime stories? When you write for children, you have the most appreciative audience in the world. But to reach that audience, you need to write fresh, dynamic stories, whether you’re writing rhymed picture books, middle grade mysteries, edgy teen novels, nonfiction, or something else.

In this book, you will learn:

How to explore the wide variety of age ranges, genres, and styles in writing stories, articles and books for young people.How to find ideas.How to develop an idea into a story, article, or book.The basics of character development, plot, setting, and theme – and some advanced elements.How to use point of view, dialogue, and thoughts.How to edit your work and get critiques.Where to learn more on various subjects.

Whether you’re just starting out or have some experience, this book will make you a better writer – and encourage you to have fun!

Published on May 08, 2017 05:00

May 1, 2017

The Long Road to Short Fiction, by Catherine Dilts

Welcome guest author Catherine Dilts! A mystery novelist, Catherine offered to share her experience writing short fiction. (If you would like a guest spot on this blog, leave a comment or contact me through my website.) Here's Catherine:

Welcome guest author Catherine Dilts! A mystery novelist, Catherine offered to share her experience writing short fiction. (If you would like a guest spot on this blog, leave a comment or contact me through my website.) Here's Catherine:The Long Road to Short Fiction

One tidbit thrown into the avalanche of advice given to new writers is, “Write and publish a short story to draw attention to your long fiction.” As though short fiction is a stepping stone to the ultimate goal, the novel.

My journey to short fiction began precisely in that manner. I was seeking an agent and/or publisher for my novel-length fiction. I had cranked out half a dozen horrible novels up to that point, and had finally written something I had hope would be publishable.

There came that advice again. The pearls of wisdom I’d ignored years ago. Write a short story, get it published, and agents and editors will notice you. THEN you can get your novel published.

But I wasn’t interested in short stories. I liked reading, and writing, novels. I finally decided to heed the advice when it came from a successful short story author. I was concerned about taking time away from my novel-length writing, but I could at least test the waters.

I attempted writing several 700 word short mysteries for a women’s magazine, Woman’s World . They were all rejected, but I learned several valuable lessons.

Writing short is hard! Mark Twain is attributed with saying, “I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.” Writing a successful short story, as opposed to a novel, turned out to be nearly as time consuming, and considerably more difficult.

Writing short stories is liberating! When writing a novel, or a novel series, you are tied into a setting and characters for a long time. Perhaps years. Short stories offer more opportunity for creativity and spontaneity. You can play with off-the-wall characters, different points of view, noir, humor, or whatever strikes your fancy.

Writing short stories is rewarding! If you are a small press, Indy, or self-pubbed author, kudos if you’re turning out a novel a year, and even more so if you’re making a profit. In a recent article, one multi-published short story author spelled out in cold, hard numbers the financial aspects of writing short. For some of us, writing short fiction may be just as financially rewarding as writing novels.

Writing short stories is rewarding! If you are a small press, Indy, or self-pubbed author, kudos if you’re turning out a novel a year, and even more so if you’re making a profit. In a recent article, one multi-published short story author spelled out in cold, hard numbers the financial aspects of writing short. For some of us, writing short fiction may be just as financially rewarding as writing novels.Short fiction is a thriving art form! From traditional magazines, to e-zines, to anthologies, short stories are enjoying a revitalized status in the fiction world. I have listed below some of the current outlets. In order to write short, you need to read short. Treat yourself to a steady diet of short fiction, and I’ll just bet you become addicted.

I no longer see short stories as a stepping stone to that loftier goal, the novel. Writing short stories taught me how to be concise. How to make every word count. How to write a coherent plot that drives to a logical conclusion.

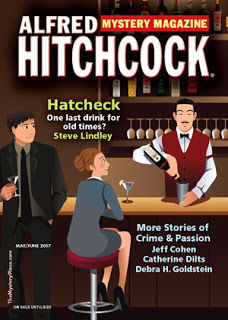

After several false starts and failed attempts, my first fiction sale was to Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine in 2013. I have since had five more published by AHMM, including "Unrepentant Sinner," appearing in the May/June 2017 issue on sale now. My story "The Chemistry of Heroes" is a Derringer finalist.

If you are one of those writers who believes you can’t write short, I challenge you to give it a try. I didn’t think I could, or wanted to, write short stories. Now short fiction is my personal success story.

Mystery ShortAlfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine

Mystery ShortAlfred Hitchcock Mystery MagazineMystery Weekly

Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine

The Strand

King’s River Life - mystery section - novel reviews and short stories

Women’s World - a short mystery in each issue

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine

Bouchercon - annual anthology

Mysterical-e

Flash and Bang - annual anthology by SMFS

Catherine Dilts is the author of the amateur sleuth Rock Shop Mystery series, set in the Colorado mountains. Her short story “The Chemistry of Heroes” (May 2016 - Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine) is a Derringer Award finalist. Watch for her story “Unrepentant Sinner” in the AHMM May/June 2017 issue, on sale now. Catherine has a day job as an environmental regulatory compliance specialist. You can learn more about Catherine at http://www.catherinedilts.com/.

Published on May 01, 2017 05:00

April 24, 2017

#NaPiBoWriWee - Developing Your Picture Book Ideas

I discussed Finding the Seeds of Stories for STORYSTORM. When brainstorming, it's fine if you think up quick, basic ideas that need a lot of development – you’ve still met the challenge! But you may want to spend a little more time developing your idea before trying to write a draft for National Picture Book Writing Week (#NaPiBoWriWee, May 1-7).

I discussed Finding the Seeds of Stories for STORYSTORM. When brainstorming, it's fine if you think up quick, basic ideas that need a lot of development – you’ve still met the challenge! But you may want to spend a little more time developing your idea before trying to write a draft for National Picture Book Writing Week (#NaPiBoWriWee, May 1-7).(The following is excerpted from You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. The bookis available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. That book and A dvanced Plotting will provide lots of help as you write and edit.)

Developing an Idea

Once you have your idea, it’s time to develop it into a story or novel. Of course, you can simply start writing and see what happens. Sometimes that’s the best way to explore an idea and see which you want to say about it. But you might save time – and frustration – by thinking about the story in advance. You don’t have to develop a formal, detailed outline, but a few ideas about what you want to say, and where you want the story to go, can help give you direction.

Once you have your idea, it’s time to develop it into a story or novel. Of course, you can simply start writing and see what happens. Sometimes that’s the best way to explore an idea and see which you want to say about it. But you might save time – and frustration – by thinking about the story in advance. You don’t have to develop a formal, detailed outline, but a few ideas about what you want to say, and where you want the story to go, can help give you direction. You can look at story structure in several ways. Here’s one example of the parts of a story or article:

· A catchy title. The best titles hint at the genre or subject matter.

· A dramatic beginning, with a hook. A good beginning:

– grabs the reader’s attention with action, dialogue, or a hint of drama to come

– sets the scene

– indicates the genre and tone (in fiction) or the article type (in nonfiction)

– has an appealing style

· A solid middle, which moves the story forward or fulfills the goal of the article.

Fiction should focus on a plot that builds to a climax, with character development. Ideally the character changes by learning the lesson of the story.

Nonfiction should focus on information directly related to the main topic. It should be organized in a logical way, with transitions between subtopics. The tone should be friendly and lively, not lecturing. Unfamiliar words should be defined within the text, or in a sidebar.

· A satisfying ending that wraps up the story or closes the article. Endings may circle back to the beginning, repeating an idea or scene, but showing change. The message should be clear here, but not preachy. What did the character learn?

· Bonus material: An article, short story, or picture book may use sidebars, crafts, recipes, photos, etc. to provide more value. For nonfiction, include a bibliography with several reliable sources.

Take a look at one of your STORYSTORM ideas. Can you start developing it by thinking about story structure in this way?

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. AdvancedPlotting is available in print or ebook at Amazon and Barnes & Noble, or in various ebook formats at Smashwords.

Published on April 24, 2017 06:00

April 18, 2017

Writing Nonfiction Books for Children: Market Research for #NaPiBoWriWee

#NaPiBoWriWee - National Picture Book Writing Week – is coming up, May 1-7. Perhaps you already have some ideas from STORYSTORM (formerly known as Picture Book Idea Month). If your ideas include nonfiction topics, you’ll need a good understanding of what editors are buying. Even if you are writing purely for your own enjoyment, or to share your memories with your family, studying other children’s literature will make you a better writer. It may also inspire new ideas!

#NaPiBoWriWee - National Picture Book Writing Week – is coming up, May 1-7. Perhaps you already have some ideas from STORYSTORM (formerly known as Picture Book Idea Month). If your ideas include nonfiction topics, you’ll need a good understanding of what editors are buying. Even if you are writing purely for your own enjoyment, or to share your memories with your family, studying other children’s literature will make you a better writer. It may also inspire new ideas!The following is excerpted and adapted from You Can Write for Children : A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.

Hit the Library

Hit the LibraryMaybe you are already an avid reader of recent children’s nonfiction. If so, great! If not, it’s time to start. You’ll learn a lot and get to enjoy wonderful stories at the same time. The library is an excellent place to explore children’s lit, but make sure you look for recent books or magazines. Styles have changed over the years, so it’s best to focus on books published in the last five years.

Try keeping notes on what you read, if you don’t already. Did you enjoy the book? Why or why not? What aspects did you think worked well, and what could have been stronger? The patterns you pick up will tell you something about the children’s book industry, but they’ll tell you even more about yourself. Maybe you are attracted to humorous articles for younger kids. Or perhaps you love picture book biographies with poetic language. If you are going to write, why not write what you love to read?

If you want to write for publication, you can also start researching agents and publishers here. When you read books you love, or ones that seem similar to your work, make a note of the publisher. You may also be able to identify the author’s agent in the acknowledgments, or from the author’s website. This will help you learn which publishers are producing what type of books. When you have something appropriate to submit, you’ll have a list of agents or publishers that are suitable.

If you want to write for publication, you can also start researching agents and publishers here. When you read books you love, or ones that seem similar to your work, make a note of the publisher. You may also be able to identify the author’s agent in the acknowledgments, or from the author’s website. This will help you learn which publishers are producing what type of books. When you have something appropriate to submit, you’ll have a list of agents or publishers that are suitable. Book Markets

Are you most interested in picture books? There are important differences between a picture book and an article, so you need to know which you are really writing and all the elements a picture book needs!

Are you most interested in picture books? There are important differences between a picture book and an article, so you need to know which you are really writing and all the elements a picture book needs! To prepare to write a picture book, you might review several of your favorite books, or see what’s new at the library or bookstore. It wouldn’t hurt to check out some of those magazines as well. They’re still a good source for understanding the interests and reading abilities of children at different ages. Plus, you might try comparing some magazine stories and some picture books to see if you can identify the differences.

Briefly, picture books are usually under 1000 words, often under 500 words, although nonfiction picture books may be up to 2500 words or so. They should have at least 12 different scenes that can be illustrated. Look for similar books at the library or bookstore and see who publishes them.

You’ll also find nonfiction in Easy Readerbooks, which are designed to help kids learn to read. They use simple vocabularies and short sentences, appropriate to a particular reading level. They may be a few hundred words long or several thousand words, depending on the reading level. Often they have a few illustrations, maybe one per chapter. Some publishers specialize in this kind of work, while others do not produce these books at all. They may also be called early readers, early chapter books, beginning readers, and so forth. For more on this kind of book, see Yes! You Can Learn How to Write Beginning Readers and Chapter Books, by Nancy Sanders.

You’ll also find nonfiction in Easy Readerbooks, which are designed to help kids learn to read. They use simple vocabularies and short sentences, appropriate to a particular reading level. They may be a few hundred words long or several thousand words, depending on the reading level. Often they have a few illustrations, maybe one per chapter. Some publishers specialize in this kind of work, while others do not produce these books at all. They may also be called early readers, early chapter books, beginning readers, and so forth. For more on this kind of book, see Yes! You Can Learn How to Write Beginning Readers and Chapter Books, by Nancy Sanders. Educational nonfiction, typically aimed at the school market, covers all school ages up through high school. Topics are usually chosen by the publisher based on what schools need. If you are interested in this kind of writing, the process is a bit different – you’ll probably need to submit a resume and writing samples instead of a manuscript or proposal. Then the publisher will contact you when/if they have a project appropriate for your skills and interests. You can submit new material every year or two when you have an expanded resume or fresh writing samples. You can still identify these publishers and get a feel for their preferred style by browsing books in the library.

Educational nonfiction, typically aimed at the school market, covers all school ages up through high school. Topics are usually chosen by the publisher based on what schools need. If you are interested in this kind of writing, the process is a bit different – you’ll probably need to submit a resume and writing samples instead of a manuscript or proposal. Then the publisher will contact you when/if they have a project appropriate for your skills and interests. You can submit new material every year or two when you have an expanded resume or fresh writing samples. You can still identify these publishers and get a feel for their preferred style by browsing books in the library.Think about how to organize your notes so they’ll be useful in the future. Should you keep a reading notebook, set up a spreadsheet, or use color-coded index cards? Find a system that works for you.

Market listings:

Children’s Writer’s & Illustrator’s Market

Magazine Markets for Children’s Writers

Book Markets for Children’s Writers

The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) provides members with THE BOOK, which includes market surveys and directories for agents. The quarterly SCBWI Bulletin provides market updates.

Stop by next Wednesday for more advice on writing work for hire educational nonfiction – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Stop by next Wednesday for more advice on writing work for hire educational nonfiction – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in You Can Write for Children : A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers

Published on April 18, 2017 05:00

April 9, 2017

Middles: Keep Your Novel Moving

With a brother who writes screenplays and teaches script writing, it's no surprise that I sometimes include script writing advice on this blog.

With a brother who writes screenplays and teaches script writing, it's no surprise that I sometimes include script writing advice on this blog.Because my local SCBWI group is talking about "maddening middles" this month, let's consider what movies have to teach us about keeping readers turning the pages through the middle of our novels.

Consider each scene in your novel. How can you make it bigger, more dramatic?

“Imagine the worst thing that could happen, and force the issue,” says Don Hewitt, who co-wrote the English-language screenplay for the Japanese animated film Spirited Away with his wife Cindy.

My brother Doug stresses the effectiveness of “set pieces—the big, funny moment in a comedy, the big action scene in an action movie. The ‘wow’ moments that audiences remember later. Novelists can give readers those scenes they’ll remember when they put the book down.”

Yet even in big scenes, you must balance action and dialogue. Long action scenes can be dull without dialog or characterization. “When you look at the page, it shouldn’t be blocky with action,” says Paul Guay, who co-wrote screenplays for Liar, Liar, The Little Rascals and Heartbreakers.

Hewitt adds, “Try to be as economical as you can with the action, and as precise as you can. Break it up with specific dialogue to strengthen it.”

Don’t let dialog take over either. Any long conversation where nothing happens is going to be boring. David Steinberg, who wrote the screenplay for Slackers and co-wrote American Pie 2, says, “Movies are about people doing things, not about people talking about doing things.” Even in comedies, he says, dialogue must be relevant to the plot. “Dialogue is funny because of the situation, not because it’s inherently funny.” The same goes for novels, too.

So throughout your novel, make sure you have a mixture of action and dialogue. And make sure both move the story forward. If your character is alone during the scene, you can use his or her thoughts in place of dialogue.

Think Movie

Try thinking cinematically as you sketch out a scene. Imagine your book made into a movie. Will it be a bunch of talking heads, people sitting around in an ordinary setting having a conversation? Try putting your characters someplace interesting instead, and maybe even giving them something to do while they talk.

In the original version of Sweet Home Alabama, Doug set some dialogue scenes in the main character’s parents’ trailer. But during filming, the scenes were shot at a Civil War re-enactment, which added Southern flavor to the movie. Apply this approach to your novel. “In a novel, you can get away with just people talking,” Doug says. “But give people something more interesting to do while talking than just drinking coffee. It makes the scene more alive.”

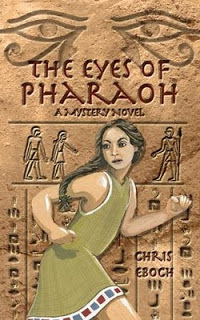

In the original version of Sweet Home Alabama, Doug set some dialogue scenes in the main character’s parents’ trailer. But during filming, the scenes were shot at a Civil War re-enactment, which added Southern flavor to the movie. Apply this approach to your novel. “In a novel, you can get away with just people talking,” Doug says. “But give people something more interesting to do while talking than just drinking coffee. It makes the scene more alive.”Here’s an example from my middle grade novel, The Eyes of Pharaoh. Reya, a 16-year-old soldier, warned his friends Seshta and Horus that Egypt is in danger from foreign nomads. He promised to tell the more at their next meeting. Seshta has been waiting anxiously:

At last Seshta reached the dock. Horus sat on the end of it, trailing a fishing line in the water.

Seshta trotted across the wooden boards. “Where’s Reya?”

“I’m glad to see you, too. Reya’s not here yet.”

“Oh.” Seshta flopped onto her back and stared at the sky. A hawk soared in lazy circles overhead. Seshta remembered her dream, and her ba fluttered in her chest. She rolled over and stared at the river.

Horus watched his fishing line, seeming content to sit there forever. Downstream, laundrymen sang as they worked at the river’s edge. Two men washed clothes in large tubs, their shaved heads glistening and their loincloths drenched. Two others beat clothes clean on stones, and one spread the garments out to dry.

Seshta sighed. “What do you think of his story yesterday? His big secret?”

“Probably just showing off to impress you. But with Reya, you never know.”

“Well, we’ll find out when he gets here. He’s not putting me off today!”

Horus glanced at her and smiled. “No.”

“I wish he’d hurry.” She slapped out a rhythm on the dock. “This is boring.”

“He’ll be here when he gets here. You can’t change time.”

Seshta sighed. Once she knew Reya was safe, she could curse him for distracting her and get back to more important matters. She needed to concentrate on dancing, not waste her time worrying about strange foreigners.

Ra, the sun god, carried his fiery burden toward the western horizon. Horus caught three catfish. A flock of ducks flew away quacking. Dusk settled over the river, dimming shapes and colors until they blurred to gray. The last fishing boats pulled in to the docks, and the fishermen headed home.

But Reya never came.__________

This is a slow scene by its nature, because they’re waiting for something that doesn’t happen. But the unusual setting makes it more interesting. Hopefully you can see the scene, and you get a feeling for the characters’ different personalities by the way they behave in that situation. We get character, setting, and plot all together.

This is a slow scene by its nature, because they’re waiting for something that doesn’t happen. But the unusual setting makes it more interesting. Hopefully you can see the scene, and you get a feeling for the characters’ different personalities by the way they behave in that situation. We get character, setting, and plot all together.Visit Doug’s fabulous scriptwriting blog, Let’s Schmooze. Doug's books, The Three Stages of Screenwriting and The Hollywood Pitching Bible, have great advice for novelists as well. Learn more or link to retailers at Screenmaster Books.

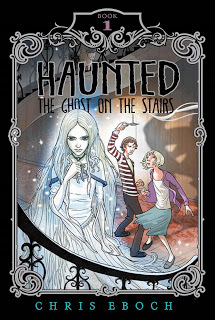

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Her novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Her novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting. Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page,

Published on April 09, 2017 04:00

April 8, 2017

Resources for Children’s Book Writers

This is the handout for my workshop at the UNM writing conference.

Books: The Idiot’s Guide to Children’s Book Publishing, by Harold Underdown, explains everything from the genres to how to find a publisher. Underdown also has FAQs about the children’s book industry, and publisher updates, on his website. The Way to Write for Children, by Joan Aiken, is also recommended. The Writer’s Bookstore and Writer’s Digest offer books on writing for children and basic writing craft, plus market guides.

You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, by Chris Eboch, offers an overview on writing for young people. Learn how to find ideas and develop those ideas into stories, articles, and books. Understand the basics of character development, plot, setting, and theme – and some advanced elements, along with how to use point of view, dialogue, and thoughts. Finally, learn about editing your work and getting critiques.

You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Chris Eboch’s Advanced Plotting is designed for the intermediate and advanced writer: you’ve finished a few manuscripts, read books and articles on writing, taken some classes, attended conferences. But you still struggle with plot, or suspect that your plotting needs work.

This really is helping me a lot. It's written beautifully and to-the-point. The essays really help you zero in on your own problems in your manuscript. The Plot Outline Exercise is a great tool!

The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (first year $95, then $80 yearly) provides informational publications on the art and business of writing and illustrating. SCBWIalso publishes a bimonthly newsletter and offers awards and grants for published works and works in progress. SCBWImembers can join discussion boards. The SCBWI has an annual Summer Conference in Los Angeles and events around the US and the world. Learn more, or find out what’s happening in your region, via the organization’s main website.

SCBWI-New Mexico, our regional branch, sends out weekly e-lerts (email notices) about our programs, other local events, and industry information. Contact elertsto get on the mailing list. We also put out a quarterly newsletter on the web site. Visit the region’s page at the organization’s main website for activities and our latest newsletter.

We have monthly Shop Talks in Albuquerque, the second Tuesday of each month, from 7-8:30 at North Domingo Baca Multigenerational Center. These feature short workshops or discussions, followed by social time. Topics and location are announced through the e-lerts.

A peer critique group meets on the third Saturday of the month, from 1:30 to 3:30 at the Erna Ferguson Library community room.

Helpful blogs:KidLit.com: Agent Mary Kole runs this blog for readers and writers of children’s literature.Adventures in YA Publishing: A group blog by young adult writers.Project Mayhem: A group blog by middle grade writers. Cynsations: News and lots of links on all aspects of children’s literature, especially multicultural books.Chris Eboch’s blog: Posts on the craft of writing.Janice Hardy’s Fiction University: Great craft advice.

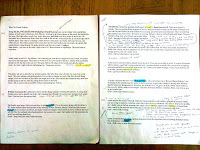

Critiques by Chris: $2 per page for novels; $40 for works up to 1000 words (picture books, stories, or articles). This provides a critique letter of editorial comments on plot, characterization, flow, language, etc. (1-2 pages for short work, 4-6 pages for novels), plus notes written on the manuscript. Learn more at her website “for writers” page.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Her novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting.

Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page, or check out her writing tips at her Write Like a Pro! blog.

Books: The Idiot’s Guide to Children’s Book Publishing, by Harold Underdown, explains everything from the genres to how to find a publisher. Underdown also has FAQs about the children’s book industry, and publisher updates, on his website. The Way to Write for Children, by Joan Aiken, is also recommended. The Writer’s Bookstore and Writer’s Digest offer books on writing for children and basic writing craft, plus market guides.

You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, by Chris Eboch, offers an overview on writing for young people. Learn how to find ideas and develop those ideas into stories, articles, and books. Understand the basics of character development, plot, setting, and theme – and some advanced elements, along with how to use point of view, dialogue, and thoughts. Finally, learn about editing your work and getting critiques.

You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Chris Eboch’s Advanced Plotting is designed for the intermediate and advanced writer: you’ve finished a few manuscripts, read books and articles on writing, taken some classes, attended conferences. But you still struggle with plot, or suspect that your plotting needs work.

This really is helping me a lot. It's written beautifully and to-the-point. The essays really help you zero in on your own problems in your manuscript. The Plot Outline Exercise is a great tool!

The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (first year $95, then $80 yearly) provides informational publications on the art and business of writing and illustrating. SCBWIalso publishes a bimonthly newsletter and offers awards and grants for published works and works in progress. SCBWImembers can join discussion boards. The SCBWI has an annual Summer Conference in Los Angeles and events around the US and the world. Learn more, or find out what’s happening in your region, via the organization’s main website.

SCBWI-New Mexico, our regional branch, sends out weekly e-lerts (email notices) about our programs, other local events, and industry information. Contact elertsto get on the mailing list. We also put out a quarterly newsletter on the web site. Visit the region’s page at the organization’s main website for activities and our latest newsletter.

We have monthly Shop Talks in Albuquerque, the second Tuesday of each month, from 7-8:30 at North Domingo Baca Multigenerational Center. These feature short workshops or discussions, followed by social time. Topics and location are announced through the e-lerts.

A peer critique group meets on the third Saturday of the month, from 1:30 to 3:30 at the Erna Ferguson Library community room.

Helpful blogs:KidLit.com: Agent Mary Kole runs this blog for readers and writers of children’s literature.Adventures in YA Publishing: A group blog by young adult writers.Project Mayhem: A group blog by middle grade writers. Cynsations: News and lots of links on all aspects of children’s literature, especially multicultural books.Chris Eboch’s blog: Posts on the craft of writing.Janice Hardy’s Fiction University: Great craft advice.

Critiques by Chris: $2 per page for novels; $40 for works up to 1000 words (picture books, stories, or articles). This provides a critique letter of editorial comments on plot, characterization, flow, language, etc. (1-2 pages for short work, 4-6 pages for novels), plus notes written on the manuscript. Learn more at her website “for writers” page.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Her novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting.

Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page, or check out her writing tips at her Write Like a Pro! blog.

Published on April 08, 2017 07:00

April 3, 2017

Turning an Idea into Story: Building the Middle

The middle of a story is a trouble spot for many writers. Maybe it feels slow, maybe it feels boring, maybe you can't even figure out what happens next.

A good middle should be filled with complications.

If a character solves his problem or reaches his goal easily, the story is boring. To keep tension high, you need complications. For short stories, try the “rule of three” and have the main character try to solve the problem three times. The first two times, he fails and the situation worsens.

Remember: the situation should worsen. If things stay the same, he still has a problem, but the tension is flat. If his first attempts make things worse, tension rises.

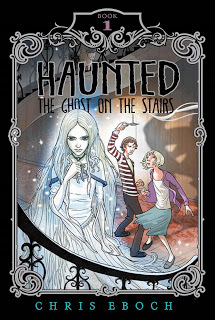

For novels, you may have even more attempts and failures. In my first Haunted book, The Ghost on the Stairs, I made sure each ghost encounter felt more dangerous. As Tania tries to get closer to the ghost in order to help her, Jon worries that she will go too far and be injured or even killed. With enough variety, you can sustain this kind of tension indefinitely (witness the ongoing battle between Harry and Voldemort in the seven-book Harry Potter series).

For novels, you may have even more attempts and failures. In my first Haunted book, The Ghost on the Stairs, I made sure each ghost encounter felt more dangerous. As Tania tries to get closer to the ghost in order to help her, Jon worries that she will go too far and be injured or even killed. With enough variety, you can sustain this kind of tension indefinitely (witness the ongoing battle between Harry and Voldemort in the seven-book Harry Potter series).

Worse and Worser You can worsen the situation in several ways. The main character’s actions could make the challenge more difficult. In my children’s mystery set in ancient Egypt, The Eyes of Pharaoh, a young temple dancer searches for her missing friend. But when she asks questions at the barracks where he was a soldier, she attracts dangerous attention from his enemies.

You can worsen the situation in several ways. The main character’s actions could make the challenge more difficult. In my children’s mystery set in ancient Egypt, The Eyes of Pharaoh, a young temple dancer searches for her missing friend. But when she asks questions at the barracks where he was a soldier, she attracts dangerous attention from his enemies.

The villain may also raise the stakes. In my Mayan historical drama, The Well of Sacrifice, the main character escapes a power-hungry high priest. He threatens to kill her entire family, forcing her to return to captivity.

The villain may also raise the stakes. In my Mayan historical drama, The Well of Sacrifice, the main character escapes a power-hungry high priest. He threatens to kill her entire family, forcing her to return to captivity.

Secondary characters can cause complications, too, even if they are not “bad guys.” In The Ghost on the Stairs, the kids’ mother decides to spend the day with them, forcing them to come up with creative ways to investigate the ghost while under her watchful eyes.

Finally, the main character may simply run out of time. At her first attempt, she had a week. At her second attempt, she had a day. Those two attempts have failed, and now she has only an hour! That creates tension.

• For each turning point in the story, brainstorm 10 things that could happen next. Then pick the one that is the worst or most unexpected, so long as it is still believable for the story.

In the coming weeks, I'll have more advice on building an exciting and dramatic middle.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Her novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting.

Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page.

A good middle should be filled with complications.

If a character solves his problem or reaches his goal easily, the story is boring. To keep tension high, you need complications. For short stories, try the “rule of three” and have the main character try to solve the problem three times. The first two times, he fails and the situation worsens.

Remember: the situation should worsen. If things stay the same, he still has a problem, but the tension is flat. If his first attempts make things worse, tension rises.

For novels, you may have even more attempts and failures. In my first Haunted book, The Ghost on the Stairs, I made sure each ghost encounter felt more dangerous. As Tania tries to get closer to the ghost in order to help her, Jon worries that she will go too far and be injured or even killed. With enough variety, you can sustain this kind of tension indefinitely (witness the ongoing battle between Harry and Voldemort in the seven-book Harry Potter series).

For novels, you may have even more attempts and failures. In my first Haunted book, The Ghost on the Stairs, I made sure each ghost encounter felt more dangerous. As Tania tries to get closer to the ghost in order to help her, Jon worries that she will go too far and be injured or even killed. With enough variety, you can sustain this kind of tension indefinitely (witness the ongoing battle between Harry and Voldemort in the seven-book Harry Potter series).Worse and Worser

You can worsen the situation in several ways. The main character’s actions could make the challenge more difficult. In my children’s mystery set in ancient Egypt, The Eyes of Pharaoh, a young temple dancer searches for her missing friend. But when she asks questions at the barracks where he was a soldier, she attracts dangerous attention from his enemies.

You can worsen the situation in several ways. The main character’s actions could make the challenge more difficult. In my children’s mystery set in ancient Egypt, The Eyes of Pharaoh, a young temple dancer searches for her missing friend. But when she asks questions at the barracks where he was a soldier, she attracts dangerous attention from his enemies. The villain may also raise the stakes. In my Mayan historical drama, The Well of Sacrifice, the main character escapes a power-hungry high priest. He threatens to kill her entire family, forcing her to return to captivity.

The villain may also raise the stakes. In my Mayan historical drama, The Well of Sacrifice, the main character escapes a power-hungry high priest. He threatens to kill her entire family, forcing her to return to captivity.Secondary characters can cause complications, too, even if they are not “bad guys.” In The Ghost on the Stairs, the kids’ mother decides to spend the day with them, forcing them to come up with creative ways to investigate the ghost while under her watchful eyes.

Finally, the main character may simply run out of time. At her first attempt, she had a week. At her second attempt, she had a day. Those two attempts have failed, and now she has only an hour! That creates tension.

• For each turning point in the story, brainstorm 10 things that could happen next. Then pick the one that is the worst or most unexpected, so long as it is still believable for the story.

In the coming weeks, I'll have more advice on building an exciting and dramatic middle.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Her novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting.

Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page.

Published on April 03, 2017 04:00

March 6, 2017

Editing Your Novel during #NaNoEdMo – The Big Picture

In honor of #NaNoEdMo (National Novel Editing Month), I'm sharing some advice from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.

The book market is more competitive than ever. Editors with mile-high submission piles can afford to choose only exceptional manuscripts. Authors who self-publish must produce work that is equal to releases from traditional publishers. And regardless of their publishing path, authors face competition from tens of thousands of other books. Serious authors know they must extensively edit and polish their manuscripts.

The book market is more competitive than ever. Editors with mile-high submission piles can afford to choose only exceptional manuscripts. Authors who self-publish must produce work that is equal to releases from traditional publishers. And regardless of their publishing path, authors face competition from tens of thousands of other books. Serious authors know they must extensively edit and polish their manuscripts.

For many writers, a new manuscript is their “baby.” You love it, and it may be hard to think of it as anything less than perfect. But you wouldn’t send your newborn baby out into the world and expect it to survive on its own. You help your children grow up, teaching them, gently correcting misbehavior, and helping them express their wonderful selves. As your children grow older, you can step back a bit and see them as individuals in their own right, separate from you. Once they are grown, you can send them off into the world, perhaps still worrying at times but with confidence that they can survive on their own.

Editing a manuscript is similar. You need to distance yourself enough from the work that you can see it for what it is – not what you dreamed it would be, but what is actually on the page. Then you guide and shape it, perhaps with help from others. You release it into the world when you’re confident the story can survive on its own, without you there to explain or defend it.

The Big Picture

Wading through hundreds of novel pages trying to identify every problem at once is intimidating and hardly effective. Even editing a picture book, short story, or article can be overwhelming if you try to address every issue at once. The best self-editors break the editorial process into steps. They also develop practices that allow them to step back from the manuscript and see it as a whole.

Wading through hundreds of novel pages trying to identify every problem at once is intimidating and hardly effective. Even editing a picture book, short story, or article can be overwhelming if you try to address every issue at once. The best self-editors break the editorial process into steps. They also develop practices that allow them to step back from the manuscript and see it as a whole.

Editor Jodie Renner recommends putting your story away for a few weeks after your first complete draft. During that time, share it with a critique group or beta readers. (Beta readers give feedback on an unpublished draft. They are not necessarily writers, so they give a reader’s opinion.) Ask your advisors to look only at the big picture: “where they felt excited, confused, curious, delighted, scared, worried, bored, etc.,” Renner says. During your writing break, you can also read books, articles, or blog posts to brush up on your craft techniques.

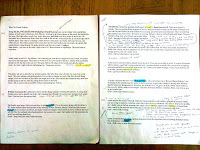

Then collect the feedback and make notes, asking for clarification as needed. Consider moving everyone’s comments onto a single manuscript for simplicity. This also allows you to see where several people have made similar comments, and to choose which suggestions you will follow. At this point, you are only making notes, not trying to implement changes.

In my book Advanced Plotting, I suggest making a chapter by chapter outline of your manuscript so you can see what you have without the distraction of details. For each scene or chapter, note the primary action, important subplots, and the mood or emotions. By getting this overview of your novel down to a few pages, you can go through it quickly looking for trouble spots. You can compare your outline to The Hero’s Journey or scriptwriting three-act structure to see if those guidelines inspire any changes. (Get this Plot Arc Exercise as a free downloadable Word document on my website.)

As you review your scenes, pay attention to anything that slows the story. Where do you introduce the main conflict? Can you eliminate your opening chapter(s) and start later? Do you have long passages of back story or explanation that aren’t necessary? Does each scene have conflict? Are there scenes out of order or repetitive scenes that could be cut? Make notes on where you need to add new scenes, delete or condense boring scenes, or move scenes.

As you review your scenes, pay attention to anything that slows the story. Where do you introduce the main conflict? Can you eliminate your opening chapter(s) and start later? Do you have long passages of back story or explanation that aren’t necessary? Does each scene have conflict? Are there scenes out of order or repetitive scenes that could be cut? Make notes on where you need to add new scenes, delete or condense boring scenes, or move scenes.

Colored highlighter pens (or the highlight function on a computer) can help you track everything from point of view changes to clues in a mystery to thematic elements. Highlight subplots and important secondary characters to make sure they are used throughout the manuscript in an appropriate way. Cut or combine minor characters who aren’t necessary.

Using Your Notes

Once you have an overview of the changes you want, revise the manuscript for these big picture items: issues such as plot, structure, characterization, point of view, and pacing. Renner recommends you then reread the entire manuscript, still focusing on the big picture. Depending on the extent of your changes, you may want to repeat this process several times.

During this stage of editing, consider market requirements if you plan to submit the work to publishers. Is your word count within an appropriate range for the genre? Are you targeting a publisher that has specific requirements? If you’re writing a romance, will the characters’ arcs and happy ending satisfy those fans? If you have an epic fantasy, is the world building strong and fresh? If your thriller runs too long, can it be broken into multiple books, or can you eliminate minor characters and subplots?

Once you’ve done all you can, you may want to hire an editor. You could also send the manuscript to new beta readers or critique partners. People who have not read the manuscript before might be better at identifying how things are working now. (See my blog posts on Critiques for tips on when and how to use family and friends, other writers, and professional editors for feedback.)

Editing Tips:

Editing Tips:

Don’t try to edit everything at once. Make several passes, looking for different problems. Start big, then focus in on details.

Try writing a one- or two-sentence synopsis. Define your goal. Do you want to produce an action-packed thriller? A laugh-out-loud book that will appeal to preteen boys? A richly detailed historical novel about a character’s internal journey? Identifying your goal can help you make decisions about what to cut and what to keep.

Next make a scene list, describing what each scene does. · Do you need to make major changes to the plot, characters, setting, or theme (fiction) or the focus of the topic (nonfiction)?· Does each scene fulfill the synopsis goal? How does it advance plot, reveal character, or both? · Does each scene build and lead to the next? Are any redundant? If you cut the scene, would you lose anything? Can any secondary characters be combined or eliminated? · Does anything need to be added or moved? Do you have a length limit or target?

· Can you increase the complications, so that at each step, more is at stake, there’s greater risk or a better reward? If each scene has the same level of risk and consequence, the pacing is flat and the middle sags.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in You Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in You Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with over 30 traditionally published books for children. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Chris also writes novels of suspense and romance for adults under the name Kris Bock; read excerpts at www.krisbock.com.

The book market is more competitive than ever. Editors with mile-high submission piles can afford to choose only exceptional manuscripts. Authors who self-publish must produce work that is equal to releases from traditional publishers. And regardless of their publishing path, authors face competition from tens of thousands of other books. Serious authors know they must extensively edit and polish their manuscripts.

The book market is more competitive than ever. Editors with mile-high submission piles can afford to choose only exceptional manuscripts. Authors who self-publish must produce work that is equal to releases from traditional publishers. And regardless of their publishing path, authors face competition from tens of thousands of other books. Serious authors know they must extensively edit and polish their manuscripts. For many writers, a new manuscript is their “baby.” You love it, and it may be hard to think of it as anything less than perfect. But you wouldn’t send your newborn baby out into the world and expect it to survive on its own. You help your children grow up, teaching them, gently correcting misbehavior, and helping them express their wonderful selves. As your children grow older, you can step back a bit and see them as individuals in their own right, separate from you. Once they are grown, you can send them off into the world, perhaps still worrying at times but with confidence that they can survive on their own.

Editing a manuscript is similar. You need to distance yourself enough from the work that you can see it for what it is – not what you dreamed it would be, but what is actually on the page. Then you guide and shape it, perhaps with help from others. You release it into the world when you’re confident the story can survive on its own, without you there to explain or defend it.

The Big Picture

Wading through hundreds of novel pages trying to identify every problem at once is intimidating and hardly effective. Even editing a picture book, short story, or article can be overwhelming if you try to address every issue at once. The best self-editors break the editorial process into steps. They also develop practices that allow them to step back from the manuscript and see it as a whole.

Wading through hundreds of novel pages trying to identify every problem at once is intimidating and hardly effective. Even editing a picture book, short story, or article can be overwhelming if you try to address every issue at once. The best self-editors break the editorial process into steps. They also develop practices that allow them to step back from the manuscript and see it as a whole.Editor Jodie Renner recommends putting your story away for a few weeks after your first complete draft. During that time, share it with a critique group or beta readers. (Beta readers give feedback on an unpublished draft. They are not necessarily writers, so they give a reader’s opinion.) Ask your advisors to look only at the big picture: “where they felt excited, confused, curious, delighted, scared, worried, bored, etc.,” Renner says. During your writing break, you can also read books, articles, or blog posts to brush up on your craft techniques.

Then collect the feedback and make notes, asking for clarification as needed. Consider moving everyone’s comments onto a single manuscript for simplicity. This also allows you to see where several people have made similar comments, and to choose which suggestions you will follow. At this point, you are only making notes, not trying to implement changes.

In my book Advanced Plotting, I suggest making a chapter by chapter outline of your manuscript so you can see what you have without the distraction of details. For each scene or chapter, note the primary action, important subplots, and the mood or emotions. By getting this overview of your novel down to a few pages, you can go through it quickly looking for trouble spots. You can compare your outline to The Hero’s Journey or scriptwriting three-act structure to see if those guidelines inspire any changes. (Get this Plot Arc Exercise as a free downloadable Word document on my website.)

As you review your scenes, pay attention to anything that slows the story. Where do you introduce the main conflict? Can you eliminate your opening chapter(s) and start later? Do you have long passages of back story or explanation that aren’t necessary? Does each scene have conflict? Are there scenes out of order or repetitive scenes that could be cut? Make notes on where you need to add new scenes, delete or condense boring scenes, or move scenes.

As you review your scenes, pay attention to anything that slows the story. Where do you introduce the main conflict? Can you eliminate your opening chapter(s) and start later? Do you have long passages of back story or explanation that aren’t necessary? Does each scene have conflict? Are there scenes out of order or repetitive scenes that could be cut? Make notes on where you need to add new scenes, delete or condense boring scenes, or move scenes.Colored highlighter pens (or the highlight function on a computer) can help you track everything from point of view changes to clues in a mystery to thematic elements. Highlight subplots and important secondary characters to make sure they are used throughout the manuscript in an appropriate way. Cut or combine minor characters who aren’t necessary.

Using Your Notes

Once you have an overview of the changes you want, revise the manuscript for these big picture items: issues such as plot, structure, characterization, point of view, and pacing. Renner recommends you then reread the entire manuscript, still focusing on the big picture. Depending on the extent of your changes, you may want to repeat this process several times.

During this stage of editing, consider market requirements if you plan to submit the work to publishers. Is your word count within an appropriate range for the genre? Are you targeting a publisher that has specific requirements? If you’re writing a romance, will the characters’ arcs and happy ending satisfy those fans? If you have an epic fantasy, is the world building strong and fresh? If your thriller runs too long, can it be broken into multiple books, or can you eliminate minor characters and subplots?

Once you’ve done all you can, you may want to hire an editor. You could also send the manuscript to new beta readers or critique partners. People who have not read the manuscript before might be better at identifying how things are working now. (See my blog posts on Critiques for tips on when and how to use family and friends, other writers, and professional editors for feedback.)

Editing Tips:

Editing Tips:Don’t try to edit everything at once. Make several passes, looking for different problems. Start big, then focus in on details.

Try writing a one- or two-sentence synopsis. Define your goal. Do you want to produce an action-packed thriller? A laugh-out-loud book that will appeal to preteen boys? A richly detailed historical novel about a character’s internal journey? Identifying your goal can help you make decisions about what to cut and what to keep.

Next make a scene list, describing what each scene does. · Do you need to make major changes to the plot, characters, setting, or theme (fiction) or the focus of the topic (nonfiction)?· Does each scene fulfill the synopsis goal? How does it advance plot, reveal character, or both? · Does each scene build and lead to the next? Are any redundant? If you cut the scene, would you lose anything? Can any secondary characters be combined or eliminated? · Does anything need to be added or moved? Do you have a length limit or target?

· Can you increase the complications, so that at each step, more is at stake, there’s greater risk or a better reward? If each scene has the same level of risk and consequence, the pacing is flat and the middle sags.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in You Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.

You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in You Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Advanced Plotting

also has advice on editing novels.Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with over 30 traditionally published books for children. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Chris also writes novels of suspense and romance for adults under the name Kris Bock; read excerpts at www.krisbock.com.

Published on March 06, 2017 05:00

February 25, 2017

Ancient Egypt Speaks to Kids Today: #History and Mystery for the Middle Grade Classroom

Today I'm celebrating the re-release of my middle grade mystery set in ancient Egypt, The Eyes of Pharaoh, via Spellbound River Press. I've been reaching out to social studies teachers, and we've already had an order for 290 copies (I'm assuming from a school district)! If you are a teacher or librarian interested in finding out if this novel would work in your school, contact me through my website to get a free digital copy for review.

Today I'm celebrating the re-release of my middle grade mystery set in ancient Egypt, The Eyes of Pharaoh, via Spellbound River Press. I've been reaching out to social studies teachers, and we've already had an order for 290 copies (I'm assuming from a school district)! If you are a teacher or librarian interested in finding out if this novel would work in your school, contact me through my website to get a free digital copy for review.

The Eyes of Pharaoh by Chris Eboch: This mystery set in 1177 BCE Egypt, for ages nine and up, introduces young readers to an ancient world. The dangers and intrigues of the time echo in the politics of today, while the power of friendship will touch hearts both young and old.

The Eyes of Pharaoh is ideal for use in elementary and middle school classrooms or by homeschooling students studying ancient Egypt. Suzanne Borchers says, “I teach a gifted class of fourth and fifth graders. Using this historical fiction is a window into Ancient Egypt—its people, culture, and beliefs. My class enjoyed doing research on Egyptian gods and goddesses, and hieroglyphs. Projects extended their knowledge of this fascinating time and place. I also highly recommend it for its fast paced plot, interesting and ‘real’ characters, and excellent writing.”

To help teachers in the classroom, extensive Lesson Plans provide material aligned to the Common Core State Standards. View them here.

The Eyes of Pharaoh is available in paperback, hardcover, and e-book via book retailers and distributors.

Chris Eboch is the author of more than 40 books for young people, including The Well of Sacrifice. This historical drama set in ninth-century Mayan Guatemala is used in many schools as supplemental fiction when students learn about the Maya. Kirkus Reviews said, “The novel shines not only for a faithful recreation of an unfamiliar, ancient world, but also for the introduction of a brave, likable and determined heroine.”

Chris Eboch is the author of more than 40 books for young people, including The Well of Sacrifice. This historical drama set in ninth-century Mayan Guatemala is used in many schools as supplemental fiction when students learn about the Maya. Kirkus Reviews said, “The novel shines not only for a faithful recreation of an unfamiliar, ancient world, but also for the introduction of a brave, likable and determined heroine.” The Eyes of Pharaoh is sure to reach readers in the same way. Ms. Eboch’s other titles include The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show; the fictionalized biographies Jesse Owens: Young Record Breaker and Milton Hershey: Young Chocolatier (part of Simon & Schuster’s Childhood of Famous Americans series); and many nonfiction titles.

Published on February 25, 2017 05:00

February 6, 2017

How Do You Turn Your Idea into a Story? Follow-Up for #STORYSTORM

Jan. 1-31 was #STORYSTORM with Tara Lazar. Formerly known as #PiBoIdMo, the challenge was to come up with one new story idea each day of the month. Maybe you met the challenge every day, or maybe you came up with fewer ideas. Either way, the next question is, "Now what?

Sometimes, a writer has a great premise, an intriguing starting point—but nothing more. How do you recognize when you have just a premise, and when you have the makings of a full story? And more importantly, how do you get from one stage to the other?

What is a story?

If you have a “great idea,” but can’t seem to go anywhere with it, you probably have a premise rather than a complete story plan. A story has four main parts: idea, complications, climax and resolution. You need all of them to make your story work.

The idea is the situation or premise. This should involve an interesting main character with a challenging problem or goal. Even this takes development. Maybe you have a great challenge, but aren’t sure why a character would have that goal. Or maybe your situation is interesting, but doesn’t actually involve a problem.

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can’t. That gave me the characters and the situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain an entire series?

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can’t. That gave me the characters and the situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain an entire series?

Tania feels sorry for the ghosts and wants to help them, while keeping her gift a secret from everyone but her brother. Jon wants to help and protect his sister, but sometimes feels overwhelmed by the responsibility.

Now we have two main characters with problems and goals. The story is off to a good start. (It became Haunted: The Ghost on the Stairs.)

Tip:

Make sure your idea is specific and narrow, especially with short stories or articles. Focus on an individual person and situation, not a universal concept. For example, don’t try to write about “racism.” Instead, write about one character facing racism in a particular situation.

Next week we'll talk about how to set up those complications through CONFLICT.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Chris Eboch’s novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Chris Eboch’s novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting.

Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page.

Sometimes, a writer has a great premise, an intriguing starting point—but nothing more. How do you recognize when you have just a premise, and when you have the makings of a full story? And more importantly, how do you get from one stage to the other?

What is a story?

If you have a “great idea,” but can’t seem to go anywhere with it, you probably have a premise rather than a complete story plan. A story has four main parts: idea, complications, climax and resolution. You need all of them to make your story work.

The idea is the situation or premise. This should involve an interesting main character with a challenging problem or goal. Even this takes development. Maybe you have a great challenge, but aren’t sure why a character would have that goal. Or maybe your situation is interesting, but doesn’t actually involve a problem.

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can’t. That gave me the characters and the situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain an entire series?

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can’t. That gave me the characters and the situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain an entire series?Tania feels sorry for the ghosts and wants to help them, while keeping her gift a secret from everyone but her brother. Jon wants to help and protect his sister, but sometimes feels overwhelmed by the responsibility.

Now we have two main characters with problems and goals. The story is off to a good start. (It became Haunted: The Ghost on the Stairs.)

Tip:

Make sure your idea is specific and narrow, especially with short stories or articles. Focus on an individual person and situation, not a universal concept. For example, don’t try to write about “racism.” Instead, write about one character facing racism in a particular situation.

Next week we'll talk about how to set up those complications through CONFLICT.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Chris Eboch’s novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting.

Chris Eboch is the author of over 40 books for children, including nonfiction and fiction, early reader through teen. Chris Eboch’s novels for ages nine and up include The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy; and the Haunted series, about kids who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Her writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting. Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page.

Published on February 06, 2017 04:00