Chris Eboch's Blog, page 21

September 23, 2015

Writing and Running: 6 Lessons Learned from Jogging

In honor of the upcoming National Women's Health & Fitness Day, I wanted to share some lessons I learned from running.

In honor of the upcoming National Women's Health & Fitness Day, I wanted to share some lessons I learned from running.In March of 2011 I started jogging. Despite the occasional illness, injury, and ‘I don’t wanna,’ I’m still getting out regularly. On one long and rather tedious solo run, I started making connections between jogging and writing and life.

Get Some Running Buddies

It helps to have inspiration. I started jogging with a Couch to 5K group that met twice a week. Having the regular schedule kept us on track. The program helped us pace ourselves, starting with short runs and frequent walks, and working up to a 45 minute run. We also had an experienced leader to offer advice.

Several of us continued running together after the program ended. I wouldn’t get out there as often if people weren’t waiting for me. I’d be tempted to stop early, if I didn’t have the encouragement of the group. Hey, peer pressure is powerful! You might as well make it work for you. Plus, it’s more fun to run with other people.

A writing retreat is a great place

A writing retreat is a great placeto get feedback – and exercise!For writers, it’s important to find the right peer group for your needs. For many, this is a critique group. They may be large or small, meet in person or online, have open or closed membership, get together weekly or monthly or as needed. Finding a group that suits your needs is invaluable.

Other writers share goals and deadlines, checking in with a friend daily or weekly to report progress. There’s that peer pressure again! Even a non-writing friend can help hold you accountable.

Finally, social groups can provide camaraderie and networking. I live in a small town with a science and engineering college; I know far more computer geeks than writers. But by making monthly trips to Albuquerque to attend a writing meeting, I’ve made many friends who understand what I do. I’ve also made connections by teaching workshops and guest speaking for groups like Sisters in Crime. For those who can’t attend in person, online discussion boards or listserves offer a sense of connection.

New scenery can be inspiring.It’s Distance, Not Speed

New scenery can be inspiring.It’s Distance, Not SpeedIt really is about the journey, not how fast you get there. Pace yourself, and enjoy the journey, or you might burn out along the way. If you can see the end, or at least imagine the cheering crowds and free food, it might give you the extra boost you need to keep going. But take time to enjoy the sights, and the experience will be a lot more fun.

As a writer, don’t focus so much on the response to your query letters. Sure, celebrate successes, and try to learn from disappointments, but put most of your energy into enjoying the journey. (That works for the rest of life, too.)

Robin LaFevers had a post at Writer Unboxed about keeping creative play in your writing.

It's okay to rest – but not for too long.But Keep Moving

It's okay to rest – but not for too long.But Keep MovingA slow pace may get you there, but if you have a long way to go, you might as well do it running. A marathon will take a lot longer at a stroll than at a jog, even a slow jog. Run when you can, walk when you need a rest, but keep moving. That’s the only way to reach the end.

Take the time you need to learn and practice your writing craft. Do as many drafts as you need to polish your novel. Don’t rush, but do keep working. Write a page a day, and you’ll have a complete draft in a year. It may not be perfect, but it will be more than what you started with.

Practice Makes Perfect, or At Least Lessens the Pain

If you’re training, you need to get out regularly. Running once a month will just leave you sore and frustrated each time, and you won’t see any progress in your fitness.

It’s the same with writing. Establishing habits and sticking to them will keep your mind fit. Writing several times a week will hone your skills and make it easier to get started next time.

Beware of Shortcuts

If I map out a 5K run, but take every shortcut, that could cut the distance down to 3 1/2K. Easier, sure, but that won’t prepare me for running a 10K. It’s the same with life. Whether you’re trying to switch careers, meet the right man or woman, or finish a novel, some shortcuts may help, but others may do more harm than good.

I work with a lot of writing students. The beginners want to know if they’ll get published after taking one course. Nobody wants to spend 10 years learning how to write, but you need to do the work in order to earn the reward at the end. If you beg your friend to send your rough draft to her editor, you’ll blow your chance to make the best use of that connection. If you self publish your work before it’s ready, you’ll waste time that could be better spent working on your craft.

Sometimes the long, hard path is the only one that gets you where you want to go.

Set your goals high and work hard to reach them!Push Yourself Sometimes

Set your goals high and work hard to reach them!Push Yourself SometimesWith enough practice, you should get better. When I started jogging, it was a struggle to go for 10 minutes without a break. Six months later, I could make it through 45 minutes without stopping.

And then I plateaued. Jogging had become comfortable, if not easy. Why cause more pain by trying to go farther or faster?

Because that’s the only way to get better. And most likely, it’s the only way to stay interested. Fortunately, one of my jogging partners is great about coming up with new workouts. We add in some sprints one day, do hills another day. We choose different routes on different terrains. Variety keeps it interesting, which makes it easier to work hard.

With my writing, I find that I get bored if I become too comfortable with something. After publishing a dozen children’s books as Chris Eboch, I wanted a change. I tried writing romantic suspense for adults, using the name Kris Bock. This brought new challenges – writing books two or three times as long as what I was used to, exploring romantic subplots, delving deeper into character. I didn’t always get things right the first time, but I became a better writer – and I renewed my interest in writing.

With my writing, I find that I get bored if I become too comfortable with something. After publishing a dozen children’s books as Chris Eboch, I wanted a change. I tried writing romantic suspense for adults, using the name Kris Bock. This brought new challenges – writing books two or three times as long as what I was used to, exploring romantic subplots, delving deeper into character. I didn’t always get things right the first time, but I became a better writer – and I renewed my interest in writing.(Janice Hardy blogged about “growing pains” novels, the books we must struggle through in order to grow as writers.)

Are you a writer who runs? Join us for the Writers Who Run retreat August 3-7, 2016, in Fontana Dam, North Carolina.

Are you a writer who runs? Join us for the Writers Who Run retreat August 3-7, 2016, in Fontana Dam, North Carolina.Kris Bock writes novels of suspense and romance involving outdoor adventures and Southwestern landscapes. Read excerpts at www.krisbock.com or visit her Amazon page.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with 30+ traditionally published books for children. Her book Advanced Plotting helps writers fine-tune their plots, while You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers offers great insight to beginning and intermediate writers. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with 30+ traditionally published books for children. Her book Advanced Plotting helps writers fine-tune their plots, while You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers offers great insight to beginning and intermediate writers. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page.

Published on September 23, 2015 06:00

August 26, 2015

Get Critique Feedback from a Pro

Expert writers often share adviceI’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. So far I've shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends; discussed some basics about critique groups; shared challenges to watch out for in a critique group, and listed specific character types to watch out for in your critique group, and taking classes to improve your writing. Now let's look at one final option, hiring a professional editor or critiquer.

Expert writers often share adviceI’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. So far I've shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends; discussed some basics about critique groups; shared challenges to watch out for in a critique group, and listed specific character types to watch out for in your critique group, and taking classes to improve your writing. Now let's look at one final option, hiring a professional editor or critiquer.Hiring a Pro

It’s tempting to stick with trading manuscripts for free, and you may get some excellent feedback that way. However, getting feedback from family, friends, and even other writers might not be enough to perfect your work. Many critique partners won’t want to read your manuscript through multiple revisions. And unless they are experienced writers and writing teachers, critique partners may miss issues a professional editor would catch.

Hiring a pro may provide better advice. You might ask a friend to help you bandage a scraped knee, but if you have a bone sticking out of your leg, you’re going to the hospital. When the situation is serious, professional experience counts, so if you are serious about your writing, consider using a professional editor.

Hiring a pro may provide better advice. You might ask a friend to help you bandage a scraped knee, but if you have a bone sticking out of your leg, you’re going to the hospital. When the situation is serious, professional experience counts, so if you are serious about your writing, consider using a professional editor. Professional developmental editors can help writers shape their manuscripts. They can help beginning or intermediate writers identify weak spots in their skill sets, acting as a one-on-one tutor. They provide expertise that family and friends, and even critique partners, often lack. A professional editor will prioritize your work because it’s a job.

Some of my critique clients have mentioned that they’ve taken a manuscript through a critique group, but they know it still needs work. They’ve gone as far as they can with critique group help, so they’re turning to a paid critique. If someone is paying me several hundred dollars to critique a novel, I’m going to devote my time to getting it done well and quickly. I’ll dig deep and be as tough – but helpful – as I can be. My novel critique letters typically run five or six single-spaced pages, with comments broken down into categories such as Characters, Setting, Plot (Beginning, Middle, and End), Theme, and Style. Most critique group members don’t have that kind of time, even if they have the skills to identify the problems.

Some of my critique clients have mentioned that they’ve taken a manuscript through a critique group, but they know it still needs work. They’ve gone as far as they can with critique group help, so they’re turning to a paid critique. If someone is paying me several hundred dollars to critique a novel, I’m going to devote my time to getting it done well and quickly. I’ll dig deep and be as tough – but helpful – as I can be. My novel critique letters typically run five or six single-spaced pages, with comments broken down into categories such as Characters, Setting, Plot (Beginning, Middle, and End), Theme, and Style. Most critique group members don’t have that kind of time, even if they have the skills to identify the problems. If you aren’t sure if you need professional help, do a trial run with a manuscript you’ve finished. Send out a half dozen queries to agents or editors and see what kind of response you get. I’ve had clients come to me because editors have turned down a manuscript they “didn’t love enough.” This is a good indicator that the idea may be strong, but the writing isn’t there yet. No hired editor can guarantee that your manuscript will ever sell, but a good editor can improve the manuscript and also teach you to be a better writer.

If you are writing purely for your own enjoyment, or to share your work with family and friends, you don’t need to worry about producing something of publishable quality. But if you are writing for publication, and agents or editors don’t seem impressed with your work, a professional critique can teach you a lot.

Preparing for the Edit

Even if you decide to hire a freelancer, you’ll get more from the experience by turning in a draft you’ve already edited. According to freelance editor Linda Lane, “Carefully preparing your manuscript for an editor rather than simply forwarding the latest draft saves dollars, because freelance editors often charge an hourly rate.” (Use the tips in Chapter 14: Editing in You Can Write for Children to revise your manuscript as much as you can on your own.) If you have critique partners, revise based on their feedback as well.

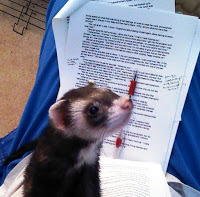

I'm an expert!Then start looking for a professional editor. However, if you want a professional critique on the content of your book – the plot, characters, overall writing style, and so forth – don’t wait until you think you have a completely polished draft. If it turns out you have major problems with the plot or character development, it’s better to identify those before you’ve gone through 10 drafts and have proofread the whole thing.

I'm an expert!Then start looking for a professional editor. However, if you want a professional critique on the content of your book – the plot, characters, overall writing style, and so forth – don’t wait until you think you have a completely polished draft. If it turns out you have major problems with the plot or character development, it’s better to identify those before you’ve gone through 10 drafts and have proofread the whole thing.Ask other writers for recommendations to editors. Try the SCBWI online discussion boards or local writers’ groups. Make sure the editor has experience with the kind of writing you are doing. Someone who only writes for adults is probably not the best editor for your children’s picture book.

Communicate clearly with a prospective editor to make sure you know what you’re getting. Typically content or developmental editors look at the big picture items. Copy editors and proofreaders can catch inconsistencies and spelling or grammar errors. Start by working with someone who will focus on content, structure, and stylistic weaknesses. Don’t pay someone to fix your typos when you might still have major changes to make. Ask questions or ask for a sample to make sure you are hiring the right editor for your needs.

Professional Editors

This listprovides past and present instructors from the Institute of Children’s Literature who critique for a fee.

Learn about my critique services here.

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.Remember the magic of bedtime stories? When you write for children, you have the most appreciative audience in the world. But to reach that audience, you need to write fresh, dynamic stories, whether you’re writing rhymed picture books, middle grade mysteries, edgy teen novels, nonfiction, or something else.

Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Published on August 26, 2015 05:30

August 20, 2015

Get Writing Feedback by Taking Classes

I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. So far I've shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends; discussed some basics about critique groups; shared challenges to watch out for in a critique group, and listed specific character types to watch out for in your critique group. Here's a new option – taking classes to improve your writing.

I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. So far I've shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends; discussed some basics about critique groups; shared challenges to watch out for in a critique group, and listed specific character types to watch out for in your critique group. Here's a new option – taking classes to improve your writing.Taking Classes

Do a little searching, and chances are you’ll find many options for writing classes to suit every need. Often community colleges offer classes. So do some senior centers or community centers. Writing organizations often have meetings that may include short workshops. They may also sponsor classes or conferences. The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators is an international organization with regional branches around the world. See if they have meetings in your area.

You might find paid classes, free meetings, or social events through other local groups, such as Sisters in Crime, Romance Writers of America, or Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America. While these groups don’t focus on writing for children, you could learn valuable writing techniques. There are also local or regional groups, such as SouthWest Writers, based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Writing Barn in Austin, Texas, has picture book classes and other writing events, some paid and some free.

An online webinarIf you can’t find a local class at a convenient time and place, you still have options. Several organizations and individuals offer classes online or through the mail. Two well-known organizations focusing on writing for kids are The Institute of Children’s Literature and Children’s Book Insider.

An online webinarIf you can’t find a local class at a convenient time and place, you still have options. Several organizations and individuals offer classes online or through the mail. Two well-known organizations focusing on writing for kids are The Institute of Children’s Literature and Children’s Book Insider.You’ll find a lot of variety in costs, course material, and how much feedback is provided. Shop around to find the class that works best for you. Do you want to learn the business side of publishing or focus on craft techniques? Do you want lectures with no homework? Do you want specific feedback from an expert teacher on your own work? Make sure that is included.

As an example, Gotham Writers Workshop offers a ten-week children’s book writing class for $400 (as of this writing). This fee covers lectures, writing exercises, and two opportunities for critiques. The Picture Book Academy offers a five-week course focused on picture books for $379. It includes access to a critique group and help through conference calls; a personal critique with a teacher is an extra $100. The Online Writing Workshops by author Anastasia Suen cost $299 and involves 12 lessons, with several critiques. She has workshops that focus on children’s novels, picture book biographies, nonfiction picture books, and rhyming picture books.

These are only a few of the many options. They are listed as examples or what’s available; I’m not offering a personal recommendation. Many experienced authors give workshops in person or online, so check out local events or browse online offerings. You can sign up for my mailing list to learn about any upcoming webinars:

Retreats build connectionsYou’ll also find some wonderful writing retreats available, some for a weekend and some for a week or more. Many are put on by SCBWI, in lovely locations around the world. The Highlights Foundation has regular retreats in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, on a variety of subjects related to writing for children. They are highly praised for the content, the setting, and the food. While the retreats are expensive, Highlights gives many scholarships.

Retreats build connectionsYou’ll also find some wonderful writing retreats available, some for a weekend and some for a week or more. Many are put on by SCBWI, in lovely locations around the world. The Highlights Foundation has regular retreats in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, on a variety of subjects related to writing for children. They are highly praised for the content, the setting, and the food. While the retreats are expensive, Highlights gives many scholarships. Some retreats may have a particular focus. For example, Picture Book Boot Camp in western Massachusetts, run by authors Jane Yolen and Heidi Stemple, is a master class for picture book authors. Other retreats cover all genres or simply allow writers time to work on their own projects.

One bonus to taking a class or attending a retreat is that you may meet other writers, who could become your critique partners after the class ends. This is easier with a live class, but even an online class may offer a chance for students to chat and connect.

Have you tried any classes in writing for children? What works well for you – a live class, online tutorial, etc.?

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. In this book, you will learn:

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. In this book, you will learn:How to explore the wide variety of age ranges, genres, and styles in writing stories, articles and books for young people.How to find ideas.How to develop an idea into a story, article, or book.The basics of character development, plot, setting, and theme.How to use point of view, dialogue, and thoughts.How to edit your work and get critiques.Where to learn more on various subjects.

Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Published on August 20, 2015 06:00

August 14, 2015

Get Southwestern Romantic Suspense on Sale

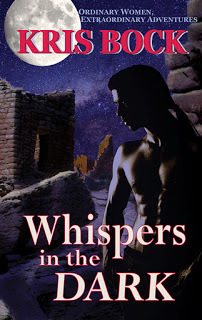

Whispers in the Dark is on sale for $.99!

Whispers in the Dark is on sale for $.99!Reviewers give it a 4.3 star average: “A great read with a strong plot line & likeable characters!”

Whispers in the Dark:

Archaeology student Kylie Hafford craves adventure when she heads to the remote Puebloan ruins of Lost Valley, Colorado, to excavate. Romance isn’t in her plans, but she soon meets two sexy men: Danesh looks like a warrior from the Pueblo’s ancient past, and Sean is a charming, playful tourist. The summer heats up as Kylie uncovers mysteries, secrets, and terrors in the dark. She’ll need all her strength and wits to survive—and to save the man she’s come to love.

Whispers in the Dark, romantic suspense set in the Four Corners region of the Southwest, will appeal to fans of Mary Stewart, Barbara Michaels, and Terry Odell. Get your copy today!

Website sampleBuy or sample on AmazonBarnes & Noble SmashwordsAppleARE

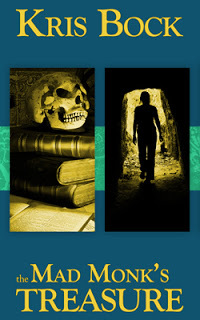

The Mad Monk’s Treasure e-book is also on sale for $.99!

The Mad Monk’s Treasure e-book is also on sale for $.99! Reviewers give it a 4.4 star average: “Great balance of history, romance, and adventure. Smart romance with an "Indiana Jones" feel. Well-written with an attention to detail that allowed me to picture exactly in my head how a scene looked and played out.” - Jules R.

A heretic Spanish priest’s gold mine, made richer by the spoils of bandits and an Apache raider—the lost Victorio Peak treasure is the stuff of legends.

When Erin, a quiet history professor, uncovers a clue that may pinpoint the lost treasure cave, she prepares for adventure. But when a hit and run driver nearly kills her, she realizes she’s not the only one after the treasure. And is Drew, the handsome helicopter pilot who found her bleeding in a ditch, really a hero, or one of the enemy? Just how far will Erin go to find the treasure and discover what she’s really made of?

“The story has it all - action, romance, danger, intrigue, lost treasure, not to mention a sizzling relationship....”

Get it now from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, All Romance E-Books, Kobo, or Apple/iTunes:

Webpage sampleAmazonNookARESmashwordsKoboApple/iTunes

Published on August 14, 2015 05:00

August 12, 2015

The Mad Monk’s Treasure on sale

The Mad Monk’s TreasureThe Mad Monk’s Treasure e-book version is currently on sale for $.99! “Great balance of history, romance, and adventure. Smart romance with an "Indiana Jones" feel. Well-written with an attention to detail that allowed me to picture exactly in my head how a scene looked and played out.” - Jules R.

The Mad Monk’s TreasureThe Mad Monk’s Treasure e-book version is currently on sale for $.99! “Great balance of history, romance, and adventure. Smart romance with an "Indiana Jones" feel. Well-written with an attention to detail that allowed me to picture exactly in my head how a scene looked and played out.” - Jules R.Get it from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, All Romance E-Books, Kobo, or Apple/iTunes. (Click the link in this post and use the website links in the left-hand column, or see the links in the comments)

http://www.krisbock.com/the_mad_monk_...

Published on August 12, 2015 16:53

•

Tags:

romantic-suspense, sale

99c Romantic Suspense sale

Whispers in the Dark is on sale for $.99!

Archaeology and intrigue among ancient Southwest ruins. Reviewers give it a 4.3 star average: “A great read with a strong plot line & likeable characters!” Get your copy today,

Whispers in the Dark: Archaeology student Kylie Hafford craves adventure when she heads to the remote Puebloan ruins of Lost Valley, Colorado, to excavate. Romance isn’t in her plans, but she soon meets two sexy men: Danesh looks like a warrior from the Pueblo’s ancient past, and Sean is a charming, playful tourist. The summer heats up as Kylie uncovers mysteries, secrets, and terrors in the dark. She’ll need all her strength and wits to survive—and to save the man she’s come to love.

Whispers in the Dark, romantic suspense set in the Four Corners region of the Southwest, will appeal to fans of Mary Stewart, Barbara Michaels, and Terry Odell.

Website sample and links to variouse-book retailers - http://www.krisbock.com/whispers_in_t...

Published on August 12, 2015 11:17

•

Tags:

romantic-suspense, sale

Critique Group Characters

Great critiquers!I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. First I shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends. Then I discussed some basics about critique groups. Last week I shared some challenges to watch out for in a critiquegroup. Now here are some specific character types to watch out for in your critique group.

Great critiquers!I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. First I shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends. Then I discussed some basics about critique groups. Last week I shared some challenges to watch out for in a critiquegroup. Now here are some specific character types to watch out for in your critique group.Critique Group Characters

Watch out for the following personality types in a critique group:

It's all wonderful!

It's all wonderful!Art by Lois BradleyThe Cheerleader. She loves everything you do! This is gratifying, especially when you are doubting your talent, but it’s not particularly helpful in improving your work.

The Grammarian. He doesn’t have a lot to say about the content of your work, but he’ll circle every typo in red pen and may insist you follow strict grammar rules that have gone out of date. (By the way, I never use red pen on critiques – blue, purple, or green ink stands out from the black text, without that negative association of graded English papers.)

Me? An opinion?The Mouse. You can’t tell whether or not she likes your work, because she never voices an opinion. She might hide behind the excuse that she’s not experienced enough to offer feedback. She’ll do this for years.

Me? An opinion?The Mouse. You can’t tell whether or not she likes your work, because she never voices an opinion. She might hide behind the excuse that she’s not experienced enough to offer feedback. She’ll do this for years.The Perpetual Beginner. He truly isn’t experienced enough to offer feedback, and he never seems to improve. This type can be divided into The Rut, who brings in the same manuscript over and over without ever making substantial changes (despite all your thoughtful advice) and The Hummingbird, who throws away a manuscript as soon as it’s gotten one negative comment, preferring to work on something new.

The Chatterbox. She wants to talk about anything and everything – other than the manuscripts you’re supposed to be critiquing. This person sees a writing group as a social occasion, not a way to improve your craft.

That's not how I'd do it.Father Knows Best. He always has an opinion, which he voices clearly and often. He prefers to discuss how he would write the story if it were his own, ignoring the author’s vision.

That's not how I'd do it.Father Knows Best. He always has an opinion, which he voices clearly and often. He prefers to discuss how he would write the story if it were his own, ignoring the author’s vision. The Bully. She enjoys tearing apart your manuscript. No suggestions, just criticisms bordering on insults.

All these characters have one thing in common. They don’t help you improve your work. Having one Cheerleader in the group can be nice, as it means you’ll hear some praise. The Grammarian may be useful, although often those comments are unnecessary and time-consuming when you are still developing a story and focusing on the big picture, not proofreading.

The Mouse and the Perpetual Beginner don’t do a lot of harm, but they waste your time. Why should you spend hours doing thoughtful critiques when you’re not getting anything in return? (Note, sometimes these people can learn over time. Ask for the specific feedback you want or encourage them to use one of the lists of critiques provided in this chapter. But if they won’t make an effort to be better critique partners, it may be time to end the relationship.)

Some people hate everythingThe Chatterbox is an even bigger time waster. Sometimes that person can be controlled by having a set time for visiting, perhaps the first or last half hour of each meeting. Including some social time is a way for the group to bond. Some critique groups like to start or end with a nice potluck meal. You could also have one or two meetings a year that are purely social. If there’s a way to get Father Knows Best or the Bully to change their behavior, I don’t know it. They should be avoided.

Some people hate everythingThe Chatterbox is an even bigger time waster. Sometimes that person can be controlled by having a set time for visiting, perhaps the first or last half hour of each meeting. Including some social time is a way for the group to bond. Some critique groups like to start or end with a nice potluck meal. You could also have one or two meetings a year that are purely social. If there’s a way to get Father Knows Best or the Bully to change their behavior, I don’t know it. They should be avoided.A good critique is kind and supportive, pointing out both good qualities and weak spots in your manuscript, and giving you ideas for how to improve it. The best critiques leave you fired up and ready to get to work on revisions, even if you know you have a lot of work ahead. Look for people who can provide that.

If you've run into these characters, do you have advice on dealing with them? Are there other character types to watch out for?

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.Remember the magic of bedtime stories? When you write for children, you have the most appreciative audience in the world. But to reach that audience, you need to write fresh, dynamic stories, whether you’re writing rhymed picture books, middle grade mysteries, edgy teen novels, nonfiction, or something else.

Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Cat emoticons by Lois Bradley.

Published on August 12, 2015 05:30

August 5, 2015

Critique Group Challenges

A good critique partner? Hmm.I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. First I shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends. Last week I discussed some basics about critique groups. Today I'm sharing some challenges to watch out for in your critique group.

A good critique partner? Hmm.I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. First I shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends. Last week I discussed some basics about critique groups. Today I'm sharing some challenges to watch out for in your critique group. Critique Group Challenges

Critique groups can be great. A good one can shorten your journey to publication by years. At their best, these groups are both a source of emotional support and a way to get thoughtful, detailed suggestions about your writing. If you have a supportive and helpful group, remember to say thank you (perhaps with hugs and chocolates).

Unfortunately, not every group is this wonderful. Some start well but fizzle out quickly, because not all members are committed. Others have trouble establishing a regular meeting time, although online groups can bring people together when they don’t live in the same area.

Cozy critiquingBeginning writers in particular may find it hard to join a serious, experienced critique group. Often the most accomplished writers want to work with other professionals, and established groups may be closed to new members. Still, you may be able to join or start a group with other beginning or intermediate writers. You can learn together and encourage each other. Some groups have started with all new writers and several years later had every member published.

Cozy critiquingBeginning writers in particular may find it hard to join a serious, experienced critique group. Often the most accomplished writers want to work with other professionals, and established groups may be closed to new members. Still, you may be able to join or start a group with other beginning or intermediate writers. You can learn together and encourage each other. Some groups have started with all new writers and several years later had every member published.In the worst case, a bad group, or even one bad person in a group, can be discouraging, even soul-crushing. Watch out for problems and act quickly to protect yourself. This could mean leaving the group, starting a splinter group with some members, or setting up new rules for the current members.

Individual writers have different levels of sensitivity. If you find any critical comment horrifying, the problem may lie with you, and you’ll need to either develop thicker skin, or write for your own enjoyment but not expect anyone else to publish or review your work.

On the other hand, if you’re normally open to suggestions but a particular critique partner leaves you feeling like you never want to write again, you may need to end that relationship. If you have a good group except for one problem person, you might discuss the issue with other members of the group. Do you think the person might respond to a direct request for a change in behavior? If not, maybe that person could be politely informed that they are not a good fit for the group. Or you could disband the group and start a new one without telling them. If you don’t take some action, the group will fall apart and you’ll lose everyone.

Have you run into these problems in a critique group?

Next week I'll discuss some of the particular problem characters who can show up in a critique group. The following weeks will provide advice on taking classes and hiring a professional editor.

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. In this book, you will learn:

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. In this book, you will learn:How to explore the wide variety of age ranges, genres, and styles in writing stories, articles and books for young people.How to find ideas.How to develop an idea into a story, article, or book.The basics of character development, plot, setting, and theme.How to use point of view, dialogue, and thoughts.How to edit your work and get critiques.Where to learn more on various subjects.

Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Published on August 05, 2015 05:30

July 29, 2015

Making the Most of a Critique Group

I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. Last week I shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends. Today, let's look at getting feedback from other writers.

I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. Last week I shared the intro to the chapter and advice on getting feedback from family and friends. Today, let's look at getting feedback from other writers.Critiquing with Other Writers

Joining a critique group is often a great way to get feedback as well as emotional support for your journey as a writer. Reach out through local writing groups, writers’ discussion boards, or Goodreads author groups. The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) “Blueboard” discussion boards have a section specifically for arranging manuscript critique exchanges. This section is available to SCBWI members only. You can also try putting up notices in libraries, bookstores, and cafes. (Be careful about listing personal information, and make sure you meet strangers in a public place.)

When you critique each other, try to keep in mind the “sandwich” method of giving feedback. You start by saying something you like about the manuscript. Then you offer some suggestions or ask questions. Finally, you end with more praise. When the more critical comments are sandwiched between compliments, it’s easier to accept the advice. Note also that you should be offering advice, not criticism. What’s the difference?

Your story is boring. – Criticism

I didn’t notice a lot of conflict. Maybe if she had a stronger goal, with higher stakes, the story would be more dramatic. – Advice

Your character is a brat. I hated her. – Criticism

I couldn’t really identify with your character. I wonder what about her appealed to you? Maybe if the reader understood her better, she’d be more likable. – Advice

Conferences are a way to meet other writersCriticism points out a problem, often in a mean way. That tends to leave the writer discouraged and not wanting to write anymore. Advice points out problems in a gentler way, ideally with ideas for fixing the problem. Suggestions should be presented as options, not absolute truth. Advice acknowledges that this is only one reader’s opinion; others may have a different reaction, and ultimately it’s the writer’s goal that matters. Good advice leaves the writer enthusiastic about working on the story.

Conferences are a way to meet other writersCriticism points out a problem, often in a mean way. That tends to leave the writer discouraged and not wanting to write anymore. Advice points out problems in a gentler way, ideally with ideas for fixing the problem. Suggestions should be presented as options, not absolute truth. Advice acknowledges that this is only one reader’s opinion; others may have a different reaction, and ultimately it’s the writer’s goal that matters. Good advice leaves the writer enthusiastic about working on the story.Have you struggled to find a good critique group, or do you have a success story to share?

Over the next few weeks, I'll be discussing critique group challenges and characters, and then offering advice on taking classes and hiring a professional editor.

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.Remember the magic of bedtime stories? When you write for children, you have the most appreciative audience in the world. But to reach that audience, you need to write fresh, dynamic stories, whether you’re writing rhymed picture books, middle grade mysteries, edgy teen novels, nonfiction, or something else.

Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers.

Published on July 29, 2015 05:30

July 22, 2015

Critiques, Critiquers, and Critiquing

I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. Here's part one, part of the intro plus advice on getting a critique from family or friends.

I’ve released a new book on the craft of writing, called

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. To celebrate the release, I’m sharing a excerpt from the chapter on Critiques. Here's part one, part of the intro plus advice on getting a critique from family or friends.Why Get a Critique?

If you are not writing for publication, and you don’t care about improving as a writer, you don’t need to take criticism from anyone. That’s fine; it’s totally your decision. But if you do hope to publish your work, or if you simply want to learn to be a better storyteller, you’ll need to get feedback at some point. Few people are good at analyzing their own writing, so getting critiques is an important part of editing and learning how to improve your writing.

Getting critical feedback can be painful. Sometimes this comes from the critique partner being unnecessarily harsh. At other times, it comes from the writer being overly sensitive. If your manuscript is your “baby,” you might not appreciate any comments that suggest it isn’t perfect. But praise alone won’t help you improve your writing.

Try to keep in mind that a critique isn’t an insult. It’s a way to help you make the manuscript even better. Also, it isn’t about you as a person, or even you as a writer. It’s about this particular manuscript, at this moment in time. If the manuscript is flawed, that’s all right. In fact, it’s usually a necessary part of the process. Most writers produce horrible, ugly, embarrassing manuscripts in the early stages. It’s the editing that makes those stories wonderful. A quote contributed to several different authors is “You can’t edit a blank page.” Get something down, and then figure out how to make it better. Getting a critique can help you figure out how to make it better.

Finally, any critique advice is a matter of opinion. If several people are pointing out a problem, there’s likely a problem. But if only one person makes a comment, and it doesn’t resonate with you, it’s fine to ignore it or get a second opinion. Ultimately you have to write something that pleases you; it’s not your job to change your manuscript based on every piece of advice that anybody cares to give.

You can get feedback in several different ways. Today we'll look at getting critiques from family members or friends.

I help!Family and Friends

I help!Family and FriendsYou may have family members or friends who are happy to read your writing. Usually these people are not experienced writers. That means they may not know how to identify story problems or give advice about them. Still, they might be able to offer opinions from a reader’s perspective.

When getting critiques from family and friends, it’s best to keep your request simple. You might ask your readers to mark any place they:

Are boredAre confusedDon’t believe things would happen that way

That’s simple enough for anyone to follow, and it should point out trouble spots in the manuscript. For a little more detail, Freelance Editor Karen R. Sandersonoffers this list to provide guidance to your critique partners:

Critical: Please provide an honest response, not only compliments.

Real: Does it feel real and does the dialogue read like people actually talk?

Imagery: Can you imagine the scenes, places, and people?

Timing: Did the timing of events, chapters, and character introductions make sense?

Interesting: Did it capture your interest or were you ready to put it down after the first paragraph?

Questions: Did you have questions? Were you unsure of what was happening or why?

Unique: Is it unique or is it like a dozen other books you wished you hadn’t purchased?

Engaging: Were you engaged in the characters, the scenes, the events?

By giving a little direction, you emphasize that you truly want feedback (not only compliments), and you encourage people to look at the bigger picture and not just mark any typos they notice. Otherwise you may only hear good things. Praise is delightful, but when it comes from people you know, the rave reviews do not necessarily mean your work is wonderful. It could mean those people don’t want to hurt your feelings. It could mean they don’t read enough in this genre to tell good from bad. Or it could simply mean that they like you and are predisposed to enjoy anything you write.

The latter issue is especially common with reading stories to your children, grandchildren, or students. They enjoy the attention and it’s fun to hear stories read aloud. People who know you well may also recognize family stories, which would not have the same appeal to an outside audience. For example, if you base a story on the antics of your family’s cat, your children may love it, but it may not resonate the same way with strangers.

The latter issue is especially common with reading stories to your children, grandchildren, or students. They enjoy the attention and it’s fun to hear stories read aloud. People who know you well may also recognize family stories, which would not have the same appeal to an outside audience. For example, if you base a story on the antics of your family’s cat, your children may love it, but it may not resonate the same way with strangers.Many professionals warn against taking feedback from non-writers too seriously. Editors and agents do not want to hear in your query letter that your children, grandchildren, students, etc. loved your work. That’s meaningless and might be taken as a sign that you are not a serious writer.

On the other hand, sometimes family members and friends offer blunt, even brutal, criticisms. Some people seem to think it’s OK to be rude to a loved one in a way they wouldn’t behave to a stranger. Some people may even be secretly trying to discourage you, so you’ll spend more time on them and not your new hobby. Others may honestly be trying to help but not know how to give balanced, encouraging feedback. Or maybe they don’t understand the kind of writing you are doing. Someone who only reads epic fantasy novels for adults may not be the best person to give feedback on a picture book for young children.

In short, feedback from friends and family can vary greatly in its helpfulness and hurtfulness. It can be especially crushing to hear negative reactions from a loved one. If someone’s comments make you feel sad or discouraged, maybe you don’t want to share your stories with that person in the future.

Of course, if you are not really ready to hear any criticism, don’t ask for it. It’s fine to share your work with family members or friends and let them know that you do not want comments, you simply want to share. If they insist on trying to provide criticism anyway, interrupt them. Make it clear that’s not their job; you only want support.

What challenges have you faced in getting feedback from family or friends?

Over the next few weeks, I'll be looking at getting feedback from other writers – including critique group challenges and characters – as well as taking classes and hiring a professional editor.

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. In this book, you will learn:

You can get this whole essay, and a lot more – including a chapter on Advanced Critique Questions – inYou Can Write for Children: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. In this book, you will learn:How to explore the wide variety of age ranges, genres, and styles in writing stories, articles and books for young people.How to find ideas.How to develop an idea into a story, article, or book.The basics of character development, plot, setting, and theme.How to use point of view, dialogue, and thoughts.How to edit your work and get critiques.Where to learn more on various subjects.

Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers

Published on July 22, 2015 05:30