Chris Eboch's Blog, page 20

January 15, 2016

Writing In No Time – Meeting Your New Year’s #Resolution

At our local SCBWI meeting this week, we discussed our writing goals – successes from last year, and goals for 2016. Since one of the big challenges is finding the time to make things happen, I wanted to reprint this article (originally from Children’s Writer).

At our local SCBWI meeting this week, we discussed our writing goals – successes from last year, and goals for 2016. Since one of the big challenges is finding the time to make things happen, I wanted to reprint this article (originally from Children’s Writer).Writing In No Time – Meeting Your New Year’s #Resolution

So many things demand our time – job, spouse, children, volunteer work, housework. It’s tempting to say, “I’ll write during vacation, or when the kids are back in school, or when the kids leave home, or when I retire ….”

Yet if you want to be a writer, you must find time to write.

Becoming a writer requires commitment. If you don’t take your work seriously, your family and friends certainly won’t either. Let them know how important writing is to you. Insist that writing time is your time, and you must not be disturbed. Carve out a few hours each week. Then close the door and ignore your phone and e-mail, or take your laptop to the library.

Finding even a few hours may seem hopeless when you have young children. Louise Spiegler, author of The Amethyst Road and The Jewel and the Key, said at that time, “It is impossible for me to write with my kids awake and active. I either tried to get both kids to nap at the same time or I spent my non-existent savings on two hours of babysitting.”

Finding even a few hours may seem hopeless when you have young children. Louise Spiegler, author of The Amethyst Road and The Jewel and the Key, said at that time, “It is impossible for me to write with my kids awake and active. I either tried to get both kids to nap at the same time or I spent my non-existent savings on two hours of babysitting.” Try trading babysitting with other writing parents. Or start a play group/writers group: the kids play, the parents write or critique.

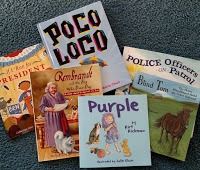

Molly Blaisdell, author of Rembrandt and the Boy Who Drew Dogs and dozens of other books and mother of four, found another creative way to keep her kids busy when they were little. “I kept all the special toys in my office. When I wanted to work on a scene, I’d pull down that box and say, ‘This is quiet time for special toys.’ It would always be good for about half an hour and sometime would go for two hours.”

Molly Blaisdell, author of Rembrandt and the Boy Who Drew Dogs and dozens of other books and mother of four, found another creative way to keep her kids busy when they were little. “I kept all the special toys in my office. When I wanted to work on a scene, I’d pull down that box and say, ‘This is quiet time for special toys.’ It would always be good for about half an hour and sometime would go for two hours.”Involve older children in your writing activities. Brainstorm story ideas together. Have them draw pictures for your manuscripts. You’ll get more done, and they’ll learn to respect your work. Plus, your time together is research. Claudia Harrington liked driving the carpool for her daughter in middle school, because “the ride home is great for eavesdropping.”

No Use for a Muse

No Use for a MuseWhen your writing time is limited, you can’t afford to waste a moment. After having a baby, freelance writer Michele Corriel, author of Fairview Felines: A Newspaper Mystery, said, “I still managed to get up before my daughter and cram in even half an hour. The problem with a shorter amount of time is you really have to ‘switch’ it on.”

Successful writers agree: no waiting for the right mood. Spiegler says, “As soon as the kids were asleep or safely dropped off, I would sit down and start working – no waiting for inspiration.”

The most productive writers work anywhere and everywhere. Jean Daigenau said, “I take advantage of the few minutes of downtime I have at school or home – while I’m eating lunch or supervising the homework group at our after-school latchkey program or soaking in the bathtub.”

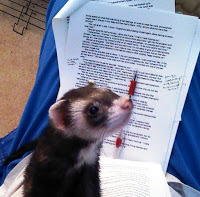

If you can’t do serious writing in five-minute bursts, use the time in other ways. Daigenau suggests, “Get it written on the computer and then use those few minutes here and there to revise.”

If you can’t do serious writing in five-minute bursts, use the time in other ways. Daigenau suggests, “Get it written on the computer and then use those few minutes here and there to revise.”Christine Liu Perkins, author of At Home in Her Tomb: Lady Dai and the Ancient Chinese Treasures of Mawangdui, commented, “When I’m constantly being interrupted, chauffeuring, or sitting in waiting rooms, I brainstorm and prewrite. Wherever I am, I focus on a specific problem for that short session. What points do I want to include in this article? What happens next in the story?”

Compromise

The best organized life can sometimes just get too full. Spiegler, who also teaches college now, cautioned against buying into the super-woman myth. “It is almost impossible for me to work at a demanding job and take care of kids and write regularly. The only way I can write is to be teaching something familiar that I can spend less prep time on.”

You can’t do it all, so decide what’s most important. Then look for areas to cut back. Reduce your work hours, or cut commute time with a job closer to home. Commute by bus and write as you ride. Arrange car pools or play dates for your kids. Dictate into a tape recorder as you walk for exercise. Let the housework slide, and make quick meals. Cut back on email, web surfing or TV.

You can’t do it all, so decide what’s most important. Then look for areas to cut back. Reduce your work hours, or cut commute time with a job closer to home. Commute by bus and write as you ride. Arrange car pools or play dates for your kids. Dictate into a tape recorder as you walk for exercise. Let the housework slide, and make quick meals. Cut back on email, web surfing or TV. Put your family to work as well. Train your kids to do housework and cook one dinner per week – they’ll learn important skills while you get free time!

Don’t let volunteer work take over your life either. Blaisdell commented, “When my volunteer schedule [as regional advisor for SCBWI] burgeoned to 80-hour weeks before conferences, it occurred to me that I could be doing a lot more writing. Yes, I made contacts as a volunteer. I learned stuff from the best writing teachers in the world. Volunteering was a part of paying my dues, but not my lifelong occupation. My time was best spent writing.”

When a real crisis intrudes – sick kids, ailing parents, a job change or divorce – you may need to take time off from writing. Just don’t let it drag on forever. Plan how you’ll handle the crisis, and schedule a time to return to writing. In the meantime, read writing magazines or books for a few minutes each week to keep your focus. Spending even five minutes a day thinking about your writing can make it easier to transition back into writing more, without feeling like you’re starting from scratch.

How about your time? Where does writing fit in your life?

Decide, and make a commitment to your work. Then repeat this mantra: I am a writer, and writers write.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with 30+ traditionally published books for children. Her novels for ages nine and up include The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy, The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; and the Haunted series, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with 30+ traditionally published books for children. Her novels for ages nine and up include The Genie’s Gift, a middle eastern fantasy, The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery in ancient Egypt; The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure; and the Haunted series, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs. Chris’s writing craft books include You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers, and Advanced Plotting. Learn more at www.chriseboch.comor her Amazon page, or check out her writing tips at her Write Like a Pro! blog.

Chris also writes for adults under the name Kris Bock. “Kris Bock” writes action-packed romantic suspense involving outdoor adventures and Southwestern landscapes. The Mad Monk’s Treasure follows the hunt for a long-lost treasure in the New Mexico desert. In The Dead Man’s Treasure, estranged relatives compete to reach a buried treasure by following a series of complex clues. In Counterfeits, stolen Rembrandt paintings bring danger to a small New Mexico town. Whispers in the Dark features archaeology and intrigue among ancient Southwest ruins. What We Found is a mystery with strong romantic elements about a young woman who finds a murder victim in the woods. Read excerpts at www.krisbock.com or visit her Amazon page. Sign up for Kris Bock newsletter for announcements of new books, sales, and more.

Chris also writes for adults under the name Kris Bock. “Kris Bock” writes action-packed romantic suspense involving outdoor adventures and Southwestern landscapes. The Mad Monk’s Treasure follows the hunt for a long-lost treasure in the New Mexico desert. In The Dead Man’s Treasure, estranged relatives compete to reach a buried treasure by following a series of complex clues. In Counterfeits, stolen Rembrandt paintings bring danger to a small New Mexico town. Whispers in the Dark features archaeology and intrigue among ancient Southwest ruins. What We Found is a mystery with strong romantic elements about a young woman who finds a murder victim in the woods. Read excerpts at www.krisbock.com or visit her Amazon page. Sign up for Kris Bock newsletter for announcements of new books, sales, and more.

Published on January 15, 2016 07:19

January 13, 2016

Writing Nonfiction for Children: Magazine Market Research

Last week I discussed Why You Should Write Magazine Nonfiction. This week let's explore magazine market research. The following is excerpted and adapted from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.

Last week I discussed Why You Should Write Magazine Nonfiction. This week let's explore magazine market research. The following is excerpted and adapted from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.A lot of people are intimidated by nonfiction but then find writing articles fun and interesting once they try a few. As a bonus, it can be easier to sell nonfiction because there’s more demand for nonfiction articles, but fewer people write them. Most children’s magazines use some nonfiction but not get many submissions. For example, Highlightspublishes about equal amounts of fiction and nonfiction, but I’ve heard the magazine receives about 90% fiction submissions. And then there are many magazines focused on topics such as science and history, which only publish nonfiction.

Plus, if you are fairly new to modern children’s lit, studying magazines is a way to learn more about writing for different ages. The Cricket Magazine Group is a great place to start. They publish 14 magazines. Some are fiction and some are nonfiction, and they cover age ranges from birth to teen. You can read an online sample of each magazine on their website.

Plus, if you are fairly new to modern children’s lit, studying magazines is a way to learn more about writing for different ages. The Cricket Magazine Group is a great place to start. They publish 14 magazines. Some are fiction and some are nonfiction, and they cover age ranges from birth to teen. You can read an online sample of each magazine on their website. You may have a good idea of what you want to write; for example, maybe you are primarily interested in fiction for ages 4-6. But give the other magazines a look anyway. You may have a great idea that would be better for a different age range.

Magazines Everywhere

Magazines EverywhereWith some digging, you can find hundreds of other magazines targeted at children, or at parents or teachers. Magazine Markets for Children’s Writers and Children’s Writers and Illustrators Market have listings. (You can see if your local library has a copy, though it's nice to have your own copy so you can add notes.)

A search for “children’s magazines” will also bring up lots of links. Many are sites selling magazines, but they give you an overview of what’s being published. If you are interested in writing about a particular sport or hobby, you might find a children’s magazine that addresses it. Most religious groups also have their own magazines for children.

Learn from Reading

Once you identify a couple of magazines that interest you, check out their writer’s guidelines. An internet search for the magazine’s name plus “writer’s guidelines” or “submission guidelines” usually does the trick. It’s important to study those guidelines, and also actual copies of the magazine, before you submit work.

Even magazines that seem similar can be quite different in their requirements. For example, some religious magazines focus on Bible stories, while others want modern true anecdotes. In some, the message can be subtle and God need not be mentioned, while in others, the focus should be on God providing guidance.

You might also get ideas for how best to craft an article or story that will appeal to that magazine’s editor. Studying National Geographic Kids several years ago, I noticed that most articles were broken into short bites of information, such as “10 Cool Things about Dolphins.” If I wanted to pitch an article to them, I’d try to do something similar.

You might also get ideas for how best to craft an article or story that will appeal to that magazine’s editor. Studying National Geographic Kids several years ago, I noticed that most articles were broken into short bites of information, such as “10 Cool Things about Dolphins.” If I wanted to pitch an article to them, I’d try to do something similar.Study the magazines and submission guidelines, making a note of the type of content and target audience. Here are some questions to ask:

· What is the target age level?· Do they use both fiction and nonfiction? If so, what is the rough percentage of each?· What is their maximum word count? Do most of the stories/articles seem to be at the longer end of the range or at the shorter end?· Are they open to submissions? What do they want (e.g., a query letter, a proposal, the complete manuscript, a writing sample)?· Do they list any topics or genres they don’t want? (e.g., no articles about insects) Note that some magazines may use their own staff for certain items. For example, they may publish puzzles, but do them all “in house” so they don’t take submissions of puzzles.

Explore the Magazine Markets:

Children’s Writers and Illustrator’s Market: http://www.writersdigestshop.com/2014-childrens-writers-illustrators-market-group

The SCBWI “Magazine Market Guide” is in The Book, included with membership: https://www.scbwi.org/online-resources/the-book/

Get magazine samples at your library, school, or house of worship; requests sample copies from the publisher; or visit publishers’ web sites to see if they have online samples.

A list of children’s magazines with links to their websites: http://www.monroe.lib.in.us/childrens/kidsmags.html

Stop by next Wednesday for more advice on analyzing the magazine market – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Stop by next Wednesday for more advice on analyzing the magazine market – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe or Follow by E-Mail buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in You Can Write for Children : A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers

Published on January 13, 2016 05:00

January 6, 2016

Why You Should Write Magazine Nonfiction

The following is excerpted and adapted from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.

The following is excerpted and adapted from

You Can Write for Children

: A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.Beginning writers often focus on trying to publish picture books or novels. However, many career writers – those who make their living from writing – do at least some nonfiction work for magazines. For example, in the tax year before this writing, I sold over a dozen articles, earning over $3000. That's more than I made from novel advances and royalties combined.

Nancy I. Sanders, author of Yes! You Can Learn How to Write Children’s Books, Get Them Published, and Build a Successful Writing Career, describes the advantages of magazine writing. “There’s an unending opportunity to get published and build your writing credentials, especially in the smaller magazines. There are countless topics to write about for each different magazine’s focus, so it’s easy to find one that matches your personal passion. And finally, there are a significant number of magazines that pay and pay well.”

Nancy I. Sanders, author of Yes! You Can Learn How to Write Children’s Books, Get Them Published, and Build a Successful Writing Career, describes the advantages of magazine writing. “There’s an unending opportunity to get published and build your writing credentials, especially in the smaller magazines. There are countless topics to write about for each different magazine’s focus, so it’s easy to find one that matches your personal passion. And finally, there are a significant number of magazines that pay and pay well.”Author, instructor, and free-lance editor Bobi Martin’s says, “If I come across a topic that intrigues me, I study Magazine Markets for Children’s Writers to find magazines that my idea might be a good fit with. Next, I check to see if the age range and word limits of the magazines I’ve targeted fit with what I had in mind for the article. When I don’t have a topic in mind, I study the listings to see what magazine editors are looking for. When I have two or three magazines in mind, I visit their websites for their most current information. This is a great way to generate new topics to write about!”

Follow the Guidelines

Checking writer’s guidelines is important, because magazines often have strict rules for article lengths and the topics they cover. Some even use theme lists, with each issue covering a specific topic, such as a particular aspect of history or science.

Marcia E. Lusted is an Assistant Editor and Staff Writer for e-Pals Publishing, working with the Cobblestone group of children’s nonfiction magazines. “My advice would be to really pay attention to what magazines’ needs are, particularly if they are themed,” she says. “We get so many good queries that just don’t fit any of our upcoming themes and we can tell that the writer hasn’t bothered to notice that we are themed! The marketing aspect of writing – figuring out what a magazine needs and matching ideas – take time and effort.”

Marcia E. Lusted is an Assistant Editor and Staff Writer for e-Pals Publishing, working with the Cobblestone group of children’s nonfiction magazines. “My advice would be to really pay attention to what magazines’ needs are, particularly if they are themed,” she says. “We get so many good queries that just don’t fit any of our upcoming themes and we can tell that the writer hasn’t bothered to notice that we are themed! The marketing aspect of writing – figuring out what a magazine needs and matching ideas – take time and effort.”One advantage to writing magazine nonfiction is that you can sometimes pitch an idea instead of submitting a completed article. Even if a magazine only accepts finished articles, you can suggest other ideas in your query letter.

“When you submit a manuscript or query a magazine with your idea, it also helps to add a list of three to five ideas that might fit well into their particular magazine if your main topic doesn’t fit their current needs,” Nancy Sanders says. “I’ve landed more magazine writing assignments over the years by including a short list of other ideas in my query or cover letter for the editor to consider. Giving them the chance to choose another topic if they find merit in your writing helps avoid the constant stream of ambiguous rejections from editors saying, ‘Doesn’t suit our current needs.’”

Stop by next Wednesday for advice on researching the magazine market – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.

Stop by next Wednesday for advice on researching the magazine market – or subscribe to get posts automatically and never miss a post. You can use the Subscribe buttons to the right, or add http://chriseboch.blogspot.com/ to Feedly or another reader.You can get the extended version of this essay, and a lot more, in You Can Write for Children : A Guide to Writing Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. Order for Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

Sign up for Chris’s Workshop Newsletter for classes and critique offers

Published on January 06, 2016 05:00

December 10, 2015

Nonfiction Truths: Finding Your Theme in Nonfiction

Writers tend to talk about theme less than they talk about characters, plot, and even setting. When theme does come up, it's usually with fiction. Yet identifying a theme can even help in writing powerful nonfiction.

Writers tend to talk about theme less than they talk about characters, plot, and even setting. When theme does come up, it's usually with fiction. Yet identifying a theme can even help in writing powerful nonfiction. Christine Liu-Perkins, author of At Home in Her Tomb: Lady Dai and the Ancient Chinese Treasures of Mawangdui, says, “My book is about a set of 2,100-year-old tombs in China that had over 3,000 well-preserved artifacts, including the body of a woman. I decided to write about the tombs as a time capsule, the various artifacts revealing what life was like during that period. Coming up with a theme really helped me develop the focus and content for my nonfiction book, and also helped in pitching my proposal to the publisher.”

Shirley Raye Redmond gives another example. “Before writing my first draft of

Blind Tom: The Horse Who Helped Build theGreat Railroad

(Mountain Press Publishing), I narrowed the focus of my story and identified my story theme by answering the following questions as thoroughly as possible: who, what, when, where, how and why? I then abbreviated my answers so they fit concisely on an index card. On the back of the card, I wrote my theme statement: With perseverance, ordinary people (and even a blind horse) can play important roles in shaping major historical events. I kept my ‘focus card’ where I could see it as I drafted—and later refined—my story.”

Shirley Raye Redmond gives another example. “Before writing my first draft of

Blind Tom: The Horse Who Helped Build theGreat Railroad

(Mountain Press Publishing), I narrowed the focus of my story and identified my story theme by answering the following questions as thoroughly as possible: who, what, when, where, how and why? I then abbreviated my answers so they fit concisely on an index card. On the back of the card, I wrote my theme statement: With perseverance, ordinary people (and even a blind horse) can play important roles in shaping major historical events. I kept my ‘focus card’ where I could see it as I drafted—and later refined—my story.” For my fictionalized biography of Olympic runner Jesse Owens, I considered the various lessons of his life in order to focus the book. Because he overcame ill health, racism, poverty and a poor education to become one of the greatest athletes the world has known, a theme quickly presented itself: Suffering can make you stronger, if you face it with courage and determination.

For my fictionalized biography of Olympic runner Jesse Owens, I considered the various lessons of his life in order to focus the book. Because he overcame ill health, racism, poverty and a poor education to become one of the greatest athletes the world has known, a theme quickly presented itself: Suffering can make you stronger, if you face it with courage and determination. With this in mind, I chose to open the book when Jesse was five, and his mother cut a growth from his chest with a knife. I ended the chapter with his father saying, “If he survived that pain, he’ll survive anything life has to offer. Pain won’t mean nothing to him now.” Jesse shows that spirit again and again throughout Jesse Owens: Young Record Breaker (Simon & Schuster), written under the name M. M. Eboch. Identifying that theme helped me craft a dramatic story, and may even inspire kids to tackle their greatest challenges.

In your theme, you can find the heart of your story. It’s your chance to share what you believe about the world, so take the time to identify and clarify your theme, and make sure your story supports it. Through your messages, you may influence children, and perhaps even change lives.

Published on December 10, 2015 15:15

November 9, 2015

PiBoIdMo: Developing Your Picture Book Ideas

Last week, I discussed Finding the Seeds of Stories for Picture Book Idea Month (PiBoIdMo). It's fine if you think up quick, basic ideas that need a lot of development – you’ve still met the challenge! But maybe you want to spend a little more time developing your idea now. Or you could bookmark this post or print it out to use later, when you go back to your favorite ideas and develop them.

Last week, I discussed Finding the Seeds of Stories for Picture Book Idea Month (PiBoIdMo). It's fine if you think up quick, basic ideas that need a lot of development – you’ve still met the challenge! But maybe you want to spend a little more time developing your idea now. Or you could bookmark this post or print it out to use later, when you go back to your favorite ideas and develop them.(The following is excerpted from You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. The bookis available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. That book and A dvanced Plotting will provide lots of help as you write and edit.)

Developing an Idea

Once you have your idea, it’s time to develop it into a story or novel. Of course, you can simply start writing and see what happens. Sometimes that’s the best way to explore an idea and see which you want to say about it. But you might save time – and frustration – by thinking about the story in advance. You don’t have to develop a formal, detailed outline, but a few ideas about what you want to say, and where you want the story to go, can help give you direction.

Once you have your idea, it’s time to develop it into a story or novel. Of course, you can simply start writing and see what happens. Sometimes that’s the best way to explore an idea and see which you want to say about it. But you might save time – and frustration – by thinking about the story in advance. You don’t have to develop a formal, detailed outline, but a few ideas about what you want to say, and where you want the story to go, can help give you direction. You can look at story structure in several ways. Here’s one example of the parts of a story or article:

· A catchy title. The best titles hint at the genre or subject matter.

· A dramatic beginning, with a hook. A good beginning:

– grabs the reader’s attention with action, dialogue, or a hint of drama to come

– sets the scene

– indicates the genre and tone (in fiction) or the article type (in nonfiction)

– has an appealing style

· A solid middle, which moves the story forward or fulfills the goal of the article.

Fiction should focus on a plot that builds to a climax, with character development. Ideally the character changes by learning the lesson of the story.

Nonfiction should focus on information directly related to the main topic. It should be organized in a logical way, with transitions between subtopics. The tone should be friendly and lively, not lecturing. Unfamiliar words should be defined within the text, or in a sidebar.

· A satisfying ending that wraps up the story or closes the article. Endings may circle back to the beginning, repeating an idea or scene, but showing change. The message should be clear here, but not preachy. What did the character learn?

· Bonus material: An article, short story, or picture book may use sidebars, crafts, recipes, photos, etc. to provide more value. For nonfiction, include a bibliography with several reliable sources.

Take a look at one of your PiBoIdMo ideas. Can you start developing it by thinking about story structure in this way?

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. AdvancedPlotting is available in print or ebook at Amazon and Barnes & Noble, or in various ebook formats at Smashwords.

Published on November 09, 2015 06:00

November 2, 2015

PiBoIdMo: Finding the Seeds of Stories

November is Picture Book Idea Month (PiBoIdMo). The goal is to come up with a new picture book idea every day. Impossible? You'll find lots of idea starters and writing prompts on the PiBoIdMosite and elsewhere.

November is Picture Book Idea Month (PiBoIdMo). The goal is to come up with a new picture book idea every day. Impossible? You'll find lots of idea starters and writing prompts on the PiBoIdMosite and elsewhere.Here are some more options for brainstorming ideas. (The following is excerpted from You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. The bookis available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. That book and A dvanced Plotting will provide lots of help as you write and edit.)

Take some time to relax and think about each question. Delve deep into your memories. Take lots of notes, even if you’re not sure yet whether you want to pursue an idea. You can put each idea on a separate index card, or fill a notebook, or start a file folder with scraps of paper. Do whatever works for you.

Find story and article ideas based on your childhood experiences, fears, dreams, etc.:

· What’s the scariest thing that happened to you as a child? The most exciting? The funniest?

· What’s the scariest thing that happened to you as a child? The most exciting? The funniest?· What’s the most fun you ever had as a child? What were your favorite activities?

· What was the hardest thing you had to do as a child?

· What interested you as a child?

· When you were a child, what did you wish would happen?

Find story and article ideas based on the experiences of your children, grandchildren, students, or other young people you know:

· What interests them?

· What interests them?· What frightens them?

· What do they enjoy?

· What challenges do they face?

· What do their lives involve – school, sports, family, religion, clubs?

Other questions to consider:

What hobbies or interests do you have that might interest children?

What hobbies or interests do you have that might interest children? What jobs or experiences have you had that could be a good starting point for an nonfiction book or story?

Do you know about other cultures, or a particular time period?

What genres do you like? Would it be fun to write in that genre?

What genres did you like as a child? Did you love mysteries, ghost stories, fantasies, or science fiction? What were your favorite books? Why?

What genres did you like as a child? Did you love mysteries, ghost stories, fantasies, or science fiction? What were your favorite books? Why?Look for inspiration in other stories, books, or TV shows. Can you take the premise and write a completely different story? Do you want to write something similar (a clever mystery, a holiday story, or whatever)? Do you want to retell a folktale or fable as a modern version, or with a cultural twist?

What do you see in the news? Is there a timely topic that could make a good article? If you read about kids doing something special, could you turn it into a profile for a children’s magazine? (This wouldn't work as well for a picture book, but I’m being flexible with the concept here.)

How might that news story work as fiction? Could you base a short story or novel on a true story about someone surviving danger or overcoming great odds?

Even the phonebook can provide inspiration. Check the Yellow Pages: Could you interview an automotive painter, animal trainer, or architect for a nonfiction book? What would life be like for a child to have parents in that field?

Wherever you look for ideas, search for things that are scary, exciting or funny – strong emotion makes a strong story.

Don’t preach. Kids don’t want to read about children learning lessons. All stories have themes, but when someone asks you about a mystery you read, you’re probably not going to say, “It was a story about how crime doesn’t pay.” Rather, you’ll talk about the exciting plot, the fascinating characters, perhaps even the unusual setting. A story’s message should be subtle.

Now start brainstorming and have fun!

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. AdvancedPlotting is available in print or ebook at Amazon and Barnes & Noble, or in various ebook formats at Smashwords.

Published on November 02, 2015 06:00

October 29, 2015

#Recipes and Tips

I have a recipe and possibly some tips in this book: We'd Rather Be Writing: 88 Authors Share Timesaving Dinner Recipes and Other Tips. Check it out if you'd like to find some quick recipes and other timesaving tips, and meet some authors writing in a variety of genres. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1940...

Published on October 29, 2015 07:15

•

Tags:

recipe

October 26, 2015

NaNoWriMo: Developing Your Idea

Last week, I discussed National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) and Picture Book Idea Month (PiBoIdMo), both of which take place over the month of November. If you plan to participate, it helps to do some prep!

Last week, I discussed National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) and Picture Book Idea Month (PiBoIdMo), both of which take place over the month of November. If you plan to participate, it helps to do some prep!Here are some tips for developing your idea. (If you are doing NaNoWriMo, try to do this before you start writing in November. For PiBoIdMo, bookmark this post or print it out so you can use it as you brainstorm ideas next month.)

(The following is excerpted from You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. The bookis available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. That book and A dvanced Plotting will provide lots of help as you write and edit.)

Developing an Idea

If you have a “great idea,” but can’t seem to go anywhere with it, you probably have a premise rather than a complete story plan. A story should have three parts: beginning, middle, and end (plus title and possibly bonus material). This can be a bit confusing though. Doesn’t every story have a beginning, middle, and end? It has to start somewhere and end at some point, and other stuff is in the middle. Beginning, middle, and end!

If you have a “great idea,” but can’t seem to go anywhere with it, you probably have a premise rather than a complete story plan. A story should have three parts: beginning, middle, and end (plus title and possibly bonus material). This can be a bit confusing though. Doesn’t every story have a beginning, middle, and end? It has to start somewhere and end at some point, and other stuff is in the middle. Beginning, middle, and end!Technically, yes, but certain things should happen at those points.

1. The beginning introduces a character with a problem or a goal.

2. During the middle of the story, that character tries to solve the problem or reach the goal. He probably fails a few times and has to try something else. Or he may make progress through several steps along the way. He should not solve the problem on the first try, however.

3. At the end, the main character solves the problem himself or reaches his goal through his own efforts.

You may find exceptions to these standard story rules, but it’s best to stick with the basics until you know and understand them. They are standard because they work!

Cute, but no conflictTeachers working with beginning writers often see stories with no conflict – no problem or goal. The story is more of a “slice of life.” Things may happen, possibly even sweet or funny things, but the story does not seem to have a clear beginning, middle, and end; it lacks structure. Without conflict, the story is not that interesting.

Cute, but no conflictTeachers working with beginning writers often see stories with no conflict – no problem or goal. The story is more of a “slice of life.” Things may happen, possibly even sweet or funny things, but the story does not seem to have a clear beginning, middle, and end; it lacks structure. Without conflict, the story is not that interesting.You can have two basic types of conflict. An external conflict is something in the physical world. It could be a problem with another person, such as a bully at school, an annoying sibling, a criminal, or a fantastical being such as a troll or demon. External conflict would also include problems such as needing to travel a long distance in bad weather.

The other type of conflict is internal. This could be anything from fear of the dark to selfishness. It’s a problem within the main character that she has to overcome or come to terms with.

An internal conflict is often expressed in an external way. If a child is afraid of the dark, we need to see that fear in action. If she’s selfish, we need to see how selfishness is causing her problems. Note that the problems need to affect the child, not simply the adults around her. If a parent is annoyed or frustrated by a child’s behavior, that’s the parent’s problem, not the child’s. The child’s goal may be the opposite of the parent’s; the child may want to stay the same, while the parent wants the child to change.

For stories with internal conflict, the main character may or may not solve the external problem. The child who is afraid of the dark might get over that fear, or she might learn to live with it by keeping a flashlight by her bed. The child who is selfish and doesn’t want to share his toys might fail to achieve that goal. Instead, he might learn the benefits of sharing.

For stories with internal conflict, the main character may or may not solve the external problem. The child who is afraid of the dark might get over that fear, or she might learn to live with it by keeping a flashlight by her bed. The child who is selfish and doesn’t want to share his toys might fail to achieve that goal. Instead, he might learn the benefits of sharing.However the problem is resolved, remember that the child main character should drive the solution. No adults stepping in to solve the problem! In the case where a child and a parent have different goals, it won’t be satisfying to young readers if the parent “wins” by punishing the child. The child must see the benefit of changing and make a decision to do so.

A Story in Four Parts

If “beginning, middle, and end” doesn’t really help you, here’s another way to think of story structure. A story has four main parts: situation, complications, climax, andresolution. You need all of them to make your story work. (This is really the same as beginning, middle, and end, with the end broken into two parts, but the terms may be clearer.)

The situation should involve an interesting main character with a challenging problem or goal. Even this takes development. Maybe you have a great challenge, but aren’t sure why a character would have that goal. Or maybe your situation is interesting, but it doesn’t actually involve a problem.

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can’t. That gave me the characters and situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain a series?

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can’t. That gave me the characters and situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain a series?Tania feels sorry for the ghosts and wants to help them, while keeping her gift a secret from everyone but her brother. Jon wants to help and protect his sister, but sometimes he feels overwhelmed by the responsibility. Now we have characters with problems and goals. The story is off to a good start. (This became the four-book Haunted series.)

Tips:

· Make sure your idea is specific and narrow. Focus on an individual person and situation, not a universal concept. For example, don’t try to write about “racism.” Instead, write about one character facing racism in a particular situation.

· The longer the story, the higher the stakes needed to sustain it. A short story character might want to win a contest; a novel character might need to save the world.

· Ask why the goal is important to the character. Why does this particular individual desperately want to succeed in this challenge?

· Ask why this goal is difficult. If reaching the goal is too easy, there is little tension and the story is too short. The goal should be possible, but just barely. It might even seem impossible. The reader should believe that the main character could fail.

· Even if your main problem is external, try giving the character an internal flaw that contributes to the difficulty. This adds complications and also makes your character seem more real. For some internal flaws, see the seven deadly sins: lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride.

· Test the idea. Change the character’s age, gender, or looks. Change the point of view, setting, external conflict, or internal conflict. Choose the combination that has the most dramatic potential.

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. AdvancedPlotting is available in print or ebook at Amazon and Barnes & Noble, or in various ebook formats at Smashwords.

Published on October 26, 2015 07:57

October 21, 2015

Getting Ready for NaNoWriMo and PiBoIdMo

During National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), thousands of people work on writing a rough draft of a novel in a month of November. For those of you who write for younger children, November is also Picture Book Idea Month (PiBoIdMo). There the goal is to come up with a new picture book idea every day. These challenges may sound intimidating, but they are widely popular.

During National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), thousands of people work on writing a rough draft of a novel in a month of November. For those of you who write for younger children, November is also Picture Book Idea Month (PiBoIdMo). There the goal is to come up with a new picture book idea every day. These challenges may sound intimidating, but they are widely popular.Why? Well, taking on an intensive challenge for a month has several advantages. The most obvious is that it very quickly gives you material to develop. You can get a jump start on a new novel, or brainstorm a few dozen picture books ideas to pursue (though not all will be worth developing).

The time pressure forces you to put aside your editor and critic hats and instead focus on getting words on paper. This helps some people avoid the insecurity that can come with starting a new project, or the temptation to endlessly edit the first few chapters instead of moving forward. For picture book writers, having a lot of new ideas allows you to choose the best one, so you don’t waste time on a mediocre idea.

The time pressure forces you to put aside your editor and critic hats and instead focus on getting words on paper. This helps some people avoid the insecurity that can come with starting a new project, or the temptation to endlessly edit the first few chapters instead of moving forward. For picture book writers, having a lot of new ideas allows you to choose the best one, so you don’t waste time on a mediocre idea.It encourages you to schedule writing time – plenty of it, every week. It’s easier to give up TV, reading, and other hobbies for a single month. It’s also easier to get family members to adjust their schedule to yours if you are requesting a favor for a month, not forever. (You may even discover that your family, and the world, can function with less of your attention than you thought. Even if you can’t devote the same amount of time to writing after November, maybe you can carve out some time every week.)

Finally, both challenges have a strong sense of community. You can network with other writers, encourage each other, and find inspiring blog posts or helpful tips to keep you moving for your project.

Are You in?

Are You in?If you want to be ready to write a novel in November, it’s best to start brainstorming and planning in advance. My next few posts will discuss finding and developing ideas. In November I'll have a couple of posts on PiBoIdMo. For NaNo writers, you can bookmark this site and stop by to check out the writing tips on everything from developing characters to building to a strong climax. (Scroll down to see the labels on the right-hand side.) Then check back in March for editing tips during National Novel Editing Month (NaNoEdMo).

The following is excerpted from You Can Write for Children : How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers. The bookis available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. That book and A dvanced Plotting will provide lots of help as you write and edit.

Finding Ideas

Finding IdeasIdeas are everywhere, including in our own lives. Of course, even the most exciting events may lack important story qualities such as character growth and strong plots. (Those qualities are covered in detail in You Can Write for Children .) Still, personal and family experiences can provide the raw material to be molded into publishable stories and articles.

Amy Houts wrote Down on the Farm, about a girl on a farm vacation who wants to ride a horse but must do chores first. Houts was inspired by her own experiences, though not by a specific episode. “I was one of those horse-crazy girls,” she says. “I knew how a girl could long to ride a horse.”

Sometimes the smallest nugget can inspire a story. Susan Uhlig says, “My teen daughters and friends went on a mission trip to do a building project. The man overseeing the project was disappointed that there were no boys. I played the writer game of ‘what if?’ What if the man wouldn’t let the team stay because they were all girls? That developed into a short story very easily – what he would say, my main character girl would do, how the problem would be solved, etc.” The story sold to Brio.

Personally, I sold a story to Highlights based on the experience of finding frogs all over my neighborhood after a rainstorm. They also bought a historical story about the Mayan ballgame. That story, and my Mayan historical novel The Well of Sacrifice, were inspired by visiting Mayan ruins in Mexico and Central America.

Personally, I sold a story to Highlights based on the experience of finding frogs all over my neighborhood after a rainstorm. They also bought a historical story about the Mayan ballgame. That story, and my Mayan historical novel The Well of Sacrifice, were inspired by visiting Mayan ruins in Mexico and Central America.Realistic, Not Real

Sometimes real life translates well into fiction – though a twist may make it more fun for children. Leslie Helakoski says, “My picture book, Big Chickens, is about all the things I was afraid of when young and I’d go into the woods with my brothers and sisters. I just turned us all into chickens and played with the language.”

Sometimes real life translates well into fiction – though a twist may make it more fun for children. Leslie Helakoski says, “My picture book, Big Chickens, is about all the things I was afraid of when young and I’d go into the woods with my brothers and sisters. I just turned us all into chickens and played with the language.” Caroline Hatton drew on school and home memories of growing up in Paris for her middle-grade novel, Véro and Philippe. Yet she did not simply write a memoir. “I wanted to write about a pet snail because I kept one in a shoebox in my family’s apartment in Paris. But in my real life, my big brother left me and my pet snail alone – not much of a story, is it? So in the book, I made the brother threaten to eat the snail, as escargot.”

Characters and outcomes may also change, Hatton points out. “My brother rigged a thing to scare me in the middle of the night. But in the book, I swapped roles, and it’s the little sister who does it to her big brother. Sharing this with kids makes them howl with the pleasure of revenge.”

Characters and outcomes may also change, Hatton points out. “My brother rigged a thing to scare me in the middle of the night. But in the book, I swapped roles, and it’s the little sister who does it to her big brother. Sharing this with kids makes them howl with the pleasure of revenge.”Houts adds, “Most of the time I have to twist the reality of an experience so my story can include all the elements of good storytelling: a contrast of characters; a goal the main character strongly desires to reach; and believable obstacles the main character needs to overcome to reach her goal. Time needs to be cut down to a day or two [for a picture book]. That condenses the action and makes the story more focused.”

Author Renee Heiss says, “Use your life story as the skeleton, and then flesh it out with period details, colorful dialogue, and tons of sensory imagery to place your young readers into the time period and setting. It’s not enough to tell what happened; you must show your readers your story and immerse them into your life as if they were a sibling growing up with you.”

Asking friends and family members to share stories can provide ideas, while allowing you to turn the story into your own creation. Uhlig didn’t witness the mission trip firsthand. “That freed me up to create problem, action, dialogue, etc. without being stuck on what really happened,” she says.

You can “borrow” stories from history and the news as well. I found an interesting tidbit in a history of Washington State. A teenage boy had met bank robbers in the woods, and for some reason he told nobody about them. Why? This question, and my imagined answers to it, became my YA survival suspense Bandits Peak.

You can “borrow” stories from history and the news as well. I found an interesting tidbit in a history of Washington State. A teenage boy had met bank robbers in the woods, and for some reason he told nobody about them. Why? This question, and my imagined answers to it, became my YA survival suspense Bandits Peak. You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback.

You Can Write for Children

: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers is available for the Kindle, in paperback, or in Large Print paperback. AdvancedPlotting is available in print or ebook at Amazon and Barnes & Noble, or in various ebook formats at Smashwords.

Published on October 21, 2015 06:56

September 23, 2015

Writing and Running: 6 Lessons Learned from Jogging

In honor of the upcoming National Women's Health & Fitness Day, I wanted to share some lessons I learned from running.

In honor of the upcoming National Women's Health & Fitness Day, I wanted to share some lessons I learned from running.In March of 2011 I started jogging. Despite the occasional illness, injury, and ‘I don’t wanna,’ I’m still getting out regularly. On one long and rather tedious solo run, I started making connections between jogging and writing and life.

Get Some Running Buddies

It helps to have inspiration. I started jogging with a Couch to 5K group that met twice a week. Having the regular schedule kept us on track. The program helped us pace ourselves, starting with short runs and frequent walks, and working up to a 45 minute run. We also had an experienced leader to offer advice.

Several of us continued running together after the program ended. I wouldn’t get out there as often if people weren’t waiting for me. I’d be tempted to stop early, if I didn’t have the encouragement of the group. Hey, peer pressure is powerful! You might as well make it work for you. Plus, it’s more fun to run with other people.

A writing retreat is a great place

A writing retreat is a great placeto get feedback – and exercise!For writers, it’s important to find the right peer group for your needs. For many, this is a critique group. They may be large or small, meet in person or online, have open or closed membership, get together weekly or monthly or as needed. Finding a group that suits your needs is invaluable.

Other writers share goals and deadlines, checking in with a friend daily or weekly to report progress. There’s that peer pressure again! Even a non-writing friend can help hold you accountable.

Finally, social groups can provide camaraderie and networking. I live in a small town with a science and engineering college; I know far more computer geeks than writers. But by making monthly trips to Albuquerque to attend a writing meeting, I’ve made many friends who understand what I do. I’ve also made connections by teaching workshops and guest speaking for groups like Sisters in Crime. For those who can’t attend in person, online discussion boards or listserves offer a sense of connection.

New scenery can be inspiring.It’s Distance, Not Speed

New scenery can be inspiring.It’s Distance, Not SpeedIt really is about the journey, not how fast you get there. Pace yourself, and enjoy the journey, or you might burn out along the way. If you can see the end, or at least imagine the cheering crowds and free food, it might give you the extra boost you need to keep going. But take time to enjoy the sights, and the experience will be a lot more fun.

As a writer, don’t focus so much on the response to your query letters. Sure, celebrate successes, and try to learn from disappointments, but put most of your energy into enjoying the journey. (That works for the rest of life, too.)

Robin LaFevers had a post at Writer Unboxed about keeping creative play in your writing.

It's okay to rest – but not for too long.But Keep Moving

It's okay to rest – but not for too long.But Keep MovingA slow pace may get you there, but if you have a long way to go, you might as well do it running. A marathon will take a lot longer at a stroll than at a jog, even a slow jog. Run when you can, walk when you need a rest, but keep moving. That’s the only way to reach the end.

Take the time you need to learn and practice your writing craft. Do as many drafts as you need to polish your novel. Don’t rush, but do keep working. Write a page a day, and you’ll have a complete draft in a year. It may not be perfect, but it will be more than what you started with.

Practice Makes Perfect, or At Least Lessens the Pain

If you’re training, you need to get out regularly. Running once a month will just leave you sore and frustrated each time, and you won’t see any progress in your fitness.

It’s the same with writing. Establishing habits and sticking to them will keep your mind fit. Writing several times a week will hone your skills and make it easier to get started next time.

Beware of Shortcuts

If I map out a 5K run, but take every shortcut, that could cut the distance down to 3 1/2K. Easier, sure, but that won’t prepare me for running a 10K. It’s the same with life. Whether you’re trying to switch careers, meet the right man or woman, or finish a novel, some shortcuts may help, but others may do more harm than good.

I work with a lot of writing students. The beginners want to know if they’ll get published after taking one course. Nobody wants to spend 10 years learning how to write, but you need to do the work in order to earn the reward at the end. If you beg your friend to send your rough draft to her editor, you’ll blow your chance to make the best use of that connection. If you self publish your work before it’s ready, you’ll waste time that could be better spent working on your craft.

Sometimes the long, hard path is the only one that gets you where you want to go.

Set your goals high and work hard to reach them!Push Yourself Sometimes

Set your goals high and work hard to reach them!Push Yourself SometimesWith enough practice, you should get better. When I started jogging, it was a struggle to go for 10 minutes without a break. Six months later, I could make it through 45 minutes without stopping.

And then I plateaued. Jogging had become comfortable, if not easy. Why cause more pain by trying to go farther or faster?

Because that’s the only way to get better. And most likely, it’s the only way to stay interested. Fortunately, one of my jogging partners is great about coming up with new workouts. We add in some sprints one day, do hills another day. We choose different routes on different terrains. Variety keeps it interesting, which makes it easier to work hard.

With my writing, I find that I get bored if I become too comfortable with something. After publishing a dozen children’s books as Chris Eboch, I wanted a change. I tried writing romantic suspense for adults, using the name Kris Bock. This brought new challenges – writing books two or three times as long as what I was used to, exploring romantic subplots, delving deeper into character. I didn’t always get things right the first time, but I became a better writer – and I renewed my interest in writing.

With my writing, I find that I get bored if I become too comfortable with something. After publishing a dozen children’s books as Chris Eboch, I wanted a change. I tried writing romantic suspense for adults, using the name Kris Bock. This brought new challenges – writing books two or three times as long as what I was used to, exploring romantic subplots, delving deeper into character. I didn’t always get things right the first time, but I became a better writer – and I renewed my interest in writing.(Janice Hardy blogged about “growing pains” novels, the books we must struggle through in order to grow as writers.)

Are you a writer who runs? Join us for the Writers Who Run retreat August 3-7, 2016, in Fontana Dam, North Carolina.

Are you a writer who runs? Join us for the Writers Who Run retreat August 3-7, 2016, in Fontana Dam, North Carolina.Kris Bock writes novels of suspense and romance involving outdoor adventures and Southwestern landscapes. Read excerpts at www.krisbock.com or visit her Amazon page.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with 30+ traditionally published books for children. Her book Advanced Plotting helps writers fine-tune their plots, while You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers offers great insight to beginning and intermediate writers. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with 30+ traditionally published books for children. Her book Advanced Plotting helps writers fine-tune their plots, while You Can Write for Children: How to Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers offers great insight to beginning and intermediate writers. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page.

Published on September 23, 2015 06:00