Jane Lindskold's Blog, page 139

May 22, 2014

TT: Who’s Your Jeeves?

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back on to learn about a plague that sounds like something right out of the Bible – and to hear about the pre-publication attention Artemis Awakening is getting. Then come back and join me and Alan as we discuss the secret lives of the Hooray Henries and the Sloane Rangers.

Younger or Older?

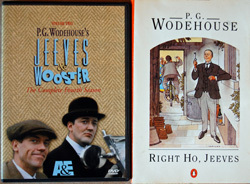

JANE: Jim and I have continued watching the dramatizations of Jeeves and Wooster starring Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry. As we were doing so, I was reminded of a bit of a controversy when these versions first came out. Many people felt that Fry was too young to be a proper Jeeves.

You’ve mentioned you were familiar both with a different adaptation and the original Wodehouse stories by the time you saw Laurie and Fry in the roles. What did you think?

ALAN: Like everyone who has come across the stories, I had a mental picture of Jeeves much coloured by Dennis Price’s performance. Price was suave and smooth in the role and very, very dryly sarcastic. Almost all the episodes have long vanished from the vaults of the BBC, but there is one episode available on Youtube. I’ve just watched it – Claude and Eustace, cousins of Bertie, arrive unexpectedly and explain to Jeeves that there is a club they wish to join – in order to join it, one has to steal things like policemen’s helmets. “Most stimulating, sir,” says Jeeves in his typical desiccated way…

JANE: I remember that story… The Seekers was the name of the club. Remind me, I need to ask you about clubs, but I shall valiantly restrain myself from tangenting at this point and let you get on about Price as Jeeves…

ALAN: Wodehouse himself was very fond of the series and declared that Dennis Price was born to play Jeeves. That’s quite a legacy for Stephen Fry to come to grips with, but I thought he caught the character perfectly. I was particularly impressed by his fruity accent and supercilious, though completely respectful, attitude. He was Dennis Price with extra smarm and one more layer of dry understatement. Absolutely top hole!

Interestingly, Price and Carmichael were almost the same age (Price was older by five years), but Price was not a healthy man and he looked considerably older than Ian Carmichael. So in the TV series Jeeves is played as an older man, almost paternalistic in his attitude towards Bertie. Fry and Laurie are exact contemporaries (they were at university together) and their Jeeves and Wooster are played as belonging to the same generation. It makes for an interesting contrast.

JANE: I was very surprised to find that some viewers of the Laurie/Fry versions thought that Fry was too young to play Jeeves. When I asked why, these dissenters said that Jeeves should be a wise elder, not Bertie’s contemporary.

Having now read pretty much all the stories, I strongly disagree. There are numerous little indications that Jeeves is closer to Bertie’s own age. In one of the Bingo Little stories, Jeeves and Bingo are (unknown to Bingo) competing for the affections of the same young lady. In another tale, Jeeves takes on the same circle of nightlife New York City that Bertie frequents and blends in like a natural – something that certainly would not be the case if he were prim and elderly.

Like Bertie, Jeeves is haunted by aunts and uncles. I’d guess Jeeves is a younger sibling, based on the age of his niece in one tale, but there is plenty of evidence that he is not an old man.

So, an elder brother, certainly, but not a father figure…

ALAN: I agree with you. And much as I admire Dennis Price’s portrayal of an older Jeeves, I now think that Stephen Fry’s portrayal is the better one.

You know, there is absolutely no way that Wodehouse could be called a naturalistic writer. The world that Jeeves and Wooster inhabit never existed. Nevertheless, Wodehouse perfectly captured the zeitgeist of the 1920s and, it has to be admitted that while we see his world through a very distorted lens, we can still recognise the characters that he caricatures.

Here’s some British slang you might enjoy. The Bertie Woosters of the world are known as Hooray Henries (I don’t know the derivation) and the females of the species are known as Sloane Rangers because their natural habitat is Sloane Square, a posh and expensive area of London handy for shopping and lunch. (They are sometimes called Hooray Henriettas as well, though that term is less common.)

JANE: I love that! I’d never heard either term. I think it’s interesting that Bertie and his crew never use these terms for themselves. To them, they are the soul of normality. I think that’s key to the effectiveness of the stories.

ALAN: Just so. As far as the characters are concerned, that is the way that the world works. And remember, as we have said many times before, there is a very thin line between comedy and tragedy. You and I might find Bertie’s dilemmas amusing, but to him they are very real catastrophes, and Jeeves is a desperately needed lifeline. I think it is that tiny little touch of reality that anchors the stories and gives them their strength.

Well, that and the fact that they really are screamingly funny. Let’s not lose sight of the most important thing.

JANE: I agree. The humor is crucial… However, it’s a type that doesn’t appeal to everyone. A friend of mine says the Bertie and Jeeves stories remind her of the old “I Love Lucy” TV show, with situations spiralling out of control. I can see her point but, while I can’t stand “I Love Lucy,” I adore Jeeves and Wooster. The key is, I think, Jeeves. There’s a comfort in knowing that, no matter how bad things get, Jeeves will come up with a solution. Bertie might end up a bit of a sacrificial lamb – in several stories, the conclusion is reached that he is mentally unbalanced – but Jeeves will never let Bertie be forced into an inappropriate marriage or left holding the bag for a conniving friend or relative.

Jim and I came up with our own lyrics to the opening music for the Laurie/Fry production that reflect this view. The final part , set to the stirring music, is: “Then came Jeeves, then came Jeeves, and, and, he saved the day!” Silly, yes, but it sums up why those stories work so well for me.

ALAN: I like that! Please send me a recording of you singing it.

JANE: Hmm… I wonder if anyone has the theme music on karaoke? (And, as an aside, both the opening theme and the animated credits are works of art in themselves.)

There’s another element that is crucial to the success of these stories as well: “The Code of the Woosters.”

In his own way, Bertie fits the model of the classic hero. His code won’t let him leave a pal in a bad situation. He will spend large sums of money, give up his dwelling, pilfer, and confront some truly terrifying people if he is appealed upon to come to the rescue.

ALAN: Oh, most certainly! Bertie is a very moral man, very honourable and straightforward. Some of Wodehouse’s other characters are more than a little dubious on the morality front, not the kind of people you’d have for tea for fear that they’d steal the family silver from under your nose. But you’d have no such worries about Bertie.

JANE: I believe that this was fully intentional on Wodehouse’s part. One of the novels is titled The Code of the Woosters, emphasizing this element of Bertie’s personality. I think this becomes more significant when one remembers that most of the other book titles are “Jeeves and…”

In this context, Bertie’s frequent, slangy references to Jeeves showing “the proper feudal spirit” take on a deeper context. I would be tempted to hazard that Bertie is a sort of Arthur, with Jeeves as his personal Merlin.

ALAN: You know, I’d never thought of Jeeves and Wooster as archetypes, but I find it hard to argue against you. Mainly because you are absolutely correct.

JANE: As you mentioned, Wodehouse didn’t always write about the same sort of characters. I’ve come to love some of his others nearly as much as Bertie and Jeeves – and to loathe at least one. Perhaps we can take a look at these next time?

May 21, 2014

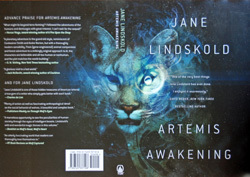

A Plague of Grasshoppers and New Reviews

What do a plague of grasshoppers and reviews for Artemis Awakening have in common? Well, the most obvious link is that they were the two most interesting things to happen to me this last week.

One of the Invaders

I think it was last Wednesday when I walked out into my yard to put some coffee grounds in the compost bin and the ground underfoot appeared to explode upwards. I literally jumped back several feet, nearly scattering coffee grounds to all sides. When I recovered from my surprise, I discovered what you (courtesy of the spoiler in the title) already have figured out. My yard was inundated with grasshoppers.

I know the word “inundated” is most commonly used for liquid materials like water and mud, but I use it deliberately here. There were so many grasshoppers that they seemed to flow up from the ground like water, moving away from me in a wave that was only interrupted when they hit the side of the house or one of the fences. It was positively creepy.

In this first encounter, the grasshoppers and I didn’t make physical contact. However, as the week went on, their numbers increased. Now, when the grasshoppers erupted from where they were hidden among the foliage, they went any which way. The majority still went away from me, but a fair number – probably reacting to the space in front of them being filled by their fellows – bounced back in my direction. I had to be careful to check my hair and clothing before going into the house, lest I carry along an unwelcome hijacker or two.

Unwelcome, I should say, to me. My four cats thought the grasshoppers were the best toys ever, better even than the occasional lizard that slips in under the porch door or the impossible to capture flying creatures. Two year-old Persephone even forewent meals if she even thought a grasshopper had gotten into the house. I’m not sure what was more interesting: watching her hunt an actual grasshopper or watching her search for the grasshopper she was certain was there, but wasn’t. Cats certainly have at least as much imagination as do writers. Maybe that’s why we get along so well.

Despite being soundly annoying, so far the plague of grasshoppers hasn’t been too terrible. They are much smaller than the ones we normally get in late summer. So far, they haven’t shown much interest in my plants. I blame them for the vanishing of a couple of beet seedlings, but that could be unfair. I’m sure we have other predators that would find tender beet greens tempting.

But we’re definitely in a “wait and see” pattern. For one, I have no idea if these grasshoppers will mature into the big green ones that do eat my plants – especially, for some reason, scarlet runner bean pods. The other is that we took advantage in a lull in the winds (which picked up again) to put some young plants in the ground: two types of tomatoes, several varieties of peppers, and ichiban eggplant. So far, the grasshoppers are ignoring them. The birds are also beginning to show an interest in adding grasshoppers to their diet. I’ve seen a few birds pick a grasshopper right out of the air. Maybe Nature will step in and provide a biological control.

Maybe not.

As I mentioned, the other new development this past week was that Artemis Awakening received more reviews from major reviewing organs. Both Library Journal and Kirkus weighed in on the “favorable” side of the balance. I understand that Artemis Awakening has a solid following on Good Reads as well. It was an io9 “pick” for May. What really makes me happy is that the reviewers seem interested not just in this one book, but in the promise of more to come.

I’ve also had queries from readers asking if I’ll be selling Artemis Awakening directly. The answer is “not now.” If you’re interested in a signed copy, you can either buy one and arrange to mail it to me (with SASE included) or contact one of the bookstores where I’ll be doing a signing. Right now, that includes Mysterious Galaxy, Borderlands Books, Page One Books, and Bookworks. Complete information as to dates and contact information are available on my website: http://www.janelindskold.com. Many independent bookstores (such as these) will arrange with you to have books signed and personalized, then ship the books to you. They’ll also have some signed stock afterwards.

However, if you’re interested in some of my older works – including many of the increasingly hard to find Avon mass market paperbacks and hard covers of most of my Tor novels (I’m sold out on some of the Firekeepers) – I have a bookstore page on my website. Unlike with sports and media stars, signing and personalization is done for no extra charge in archival quality ink, often in color! Do consider a signed book as a gift for that difficult person on your list. You can be sure to provide something no one else will!

Now to consider… I often hang my laundry outside. I wonder if I do so how many grasshoppers will it pick up?

May 15, 2014

TT: Enter Bertie and Jeeves

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back one and learn why writers should be careful not to overburden their camels. Then join me and Alan as we happily chatter on about characters we both met within visual media and followed back into prose.

Wooster and Jeeves

JANE: These last few weeks, Jim and I have been ending our evenings watching an episode of the “Jeeves and Wooster” stories as adapted for television. These are the ones with Hugh Laurie as Bertie Wooster and Stephen Fry as his “man,” Jeeves. Are you familiar with them?

ALAN: Indeed I am. Though, rather foolishly, I avoided watching them for quite a long time. I was sure that they couldn’t possibly be any good. It was only when Robin bought one of the DVDs that I finally watched an episode. Needless to say, I was immediately hooked, and we quickly devoured the rest of them.

JANE: Why didn’t you want to watch them?

ALAN: In the 1960s, the BBC made a series about Jeeves and Wooster with Dennis Price as Jeeves and Ian Carmichael as Bertie Wooster. (You’ve probably never heard of those actors, but they were very big in England at the time). The series was a huge success – the critics raved about it and people stayed home in droves to watch it. I had such fond memories of that series that I simply couldn’t see how Fry and Laurie could possibly improve upon it. At best, I thought, they would be pale imitations of the original. I couldn’t have been more wrong, of course. I now think that Fry and Laurie are the definitive Jeeves and Wooster.

JANE: Ah… Actually, I do know who Ian Carmichael is! I became acquainted with his work via audio books. He read a good number of Dorothy Sayer’s works, if I remember correctly. Did a brilliant job. I think he might have played Peter Wimsey in a dramatized version – but there I go out on a limb.

ALAN: You are correct – he did indeed play Peter Wimsey, again for the BBC. There was a time when it seemed that Ian Carmichael had completely cornered the market in upper class chaps. Every time you turned on the TV, there he was…

JANE: Actually, I think there are similarities between the characters of Bertie Wooster and the young Peter Wimsey. The difference is that Wimsey is playing the role to conceal the fact that his experiences in the trenches of WWI have left him emotionally shattered, while Bertie… Well, Bertie is Bertie.

Have you read any of the original Jeeves and Wooster stories?

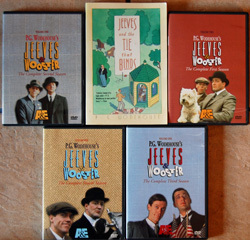

ALAN: Yes indeed. On the strength of the Carmichael and Price series, I started taking a lot of Wodehouse books out of the library. In some ways I found them to be better than the TV series – television is a very plot and character driven medium, and while Wodehouse created wonderful characters and convoluted plots that translate extremely well to the screen, he was also a master wordsmith who crafted some of the funniest and most elegant sentences I’ve ever encountered. You never see any of that aspect of his writing on the television, of course. So I love his books; they have an extra dimension to them.

JANE: Like you, I encountered the television productions first. (Although a different one.) George R.R. Martin brought over the first DVD, way back in the day when Roger was still alive. Or maybe he gave it to us for Christmas. Anyhow, we enjoyed it greatly. Eventually, I introduced Jim to the productions. When opportunity arose, we bought the whole set.

Along the way, when searching for an appealing audio book, I came across Wodehouse and decided to give him a try. I was very taken with the stories, although I noticed changes from how they had been scripted. Actually, though, overall I was happily impressed by these adaptations.

ALAN: That’s interesting. What changes did you spot?

JANE: Well, there are always changes. That’s part of a good adaptation. For example, when Bertie first tries Jeeves’ anti-hangover potion, Wodehouse’s description is brilliant and very, very funny. As you said, the writing is positively brilliant. The folks writing the script dropped all of this and let Hugh Laurie carry it all with his wonderfully mobile face.

There were a lot of changes along this order.

What I noticed – and which impressed me greatly – was how often the script writers took several stories and interwove them. This permitted an hour-long episode that moved rapidly and was full of incident, where relying on a faithful adaptation of one story would have required them to pad.

ALAN: It’s been many, many years since I read the stories and I really don’t remember any plot details from them. In my head, the stories are all a vague mishmash of country houses, terrifying aunts, inappropriate trousers of which Jeeves does not approve, marriage proposals gone wrong, and Jeeves finally sorting everything out on condition that Bertie gets rid of the trousers. Can you give me an example of what you mean?

JANE: Sure! A good example is when they combined the story about Bertie’s Uncle George and the waitress with the story of Bertie’s visit to the house of friends where, despite a moratorium on gambling, the very creepy Steggles makes book at the events at the local church fair.

Stretching either of these stories to a full hour production would have weakened their impact. Instead, the events with Uncle George are why Bertie flees to the country. A cameo with Uncle George and his bride-to-be near the end of the episode links the stories nicely.

In combining them, the scriptwriters were well within what might be called the “Wodehouse tradition,” since many – although not all – of his “novels” were actually interlinked short stories arranged as novels.

ALAN: That’s interesting. And you are right, many of Wodehouse’s novels are just short story collections. And jolly good show, I say!

JANE: Sometimes the combinations were a bit over the top, I’ll admit. In the “American” sequence, the story of Rocky Todd and his domineering aunt was combined with that of Bicky Bickerstaff and his tightwad father in a fashion that I’m still meditating over… Unlike my prior example, this combination led to more distortion of the original stories. Still… If I let myself relax, I can see there were advantages as well.

We’ve barely touched on the complex entity that is P.G. Wodehouse. I’d love to talk about pigs, but pumas are beckoning. How about next time?

May 14, 2014

At a Loss…

This week I’m rather at a loss for something to wander on about. It’s not because nothing is going on. Rather it’s because too many small things are going on. This leaves me distracted and disoriented which, in turn, makes it difficult to come up with something to write about.

Writers! Don’t Overburden Your Camel!

I’ve certainly never been one of those writers who needs “a room of one’s own” to work. I’ve written in classrooms, in faculty meetings, in my office (back when I still taught), on airplanes, and at boring banquets. However, a certain amount of what might be called clear “head room” is a good thing to have, especially when, as with these wanderings, I need to come up with a new topic every week.

As anyone knows who has ever stared at the wall in desperation trying to figure out what to write for some college essay assignment, formulating the idea is half or even three-quarters of the battle. Back then, I’d spend a considerable amount of time rendering all my various thoughts down to a simple, one sentence thesis statement. After that, the rest of the paper would flow easily.

The same can be true with fiction writing. Getting the idea, whether for the overall project or for the particular section one is working on, is the biggest challenge. Once you slip into your characters’ heads, then the story toddles along quite nicely. Getting in there is the hard part.

By purest coincidence, over the last couple of months, I spoke with two professional writer friends who admitted that they were behind because they had assumed they could take on more work by scheduling themselves to write on Project One in the morning and Project Two in the afternoon. Both of these gentlemen – multiply published, quite experienced authors – discovered that this was impossible. Once they were securely into one universe, their imaginations did not want to shift into the other.

Even worse, they discovered that the Morning/ Afternoon division of labor did not work, because even prolific writers seem to have only so much writing in them. When that writing has been expended, the Muse acts like a camel that has had the proverbial “last straw” loaded into her panniers. She folds her legs under herself, sits down, and refuses to get up until the unreasonable burden is removed.

So, how does a writer cope with this? One way is to do what I’m doing right now – start writing and see what comes out. In other of these wanderings, I believe I’ve mentioned that when I can’t seem to write anything, I make myself write at least twelve sentences.

This number evolved from a time when Roger Zelazny mentioned to me that he managed to sit down three or four times a day and write three to four sentences each time and that somehow this managed to turn into a considerable amount of finished prose – especially since when he had a really good day and wrote pages and pages, he didn’t take the next day off, but went right back to that sitting down three to four times a day and writing three to four sentences.

Anyhow, I was teaching college then and was lucky if I could find time to work on fiction once a day, so I multiplied three to four times by three to four sentences and arrived at twelve. It worked. I wrote four novels and quite a number of short stories while teaching college full time, by dedicating time to getting those twelve sentences on paper. (And I was teaching English, so I was also spending a huge amount of time reading and grading essays. This is not an inspirational activity, I assure you.)

Nonetheless, even with the best will and finest discipline in the universe, it seems that the Muse is only willing to let a writer come up with so much prose in a day. How much varies from writer to writer. However, I firmly believe that with a strict exercise regime, the Muse can be convinced to give a little bit more, just as a runner or swimmer can go from doing one or two laps to three or four, on and on, until a whole mile is reached.

But the training takes patience and quite a bit of understanding of one’s own temperament. This is one reason I only write one Wandering a week. Often on the day that I write it, my creative well is dry for the day. My Muse turns camel. Even if I remind her that we weren’t writing fiction, just a nice, bouncy little essay, she says, “Hah! You can’t fool me.” Sometimes she’s kinder and will accept a division between fiction and non-fiction.

Tempting the Muse works best for me if the fiction piece is already underway, particularly if I stopped in the middle of a particularly juicy scene, so that the Muse is eager to show off how we’re going to get our characters out of whatever predicament they’re in at that moment.

Sometimes even that isn’t enough.

So, my advice if you’re stuck? Write. Even when you don’t think you have anything to write about, write. You just might (as I have myself today) surprise yourself!

May 8, 2014

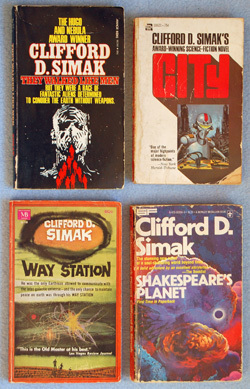

TT: Simak, Spirituality, and Sound

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back one and get a glimpse at the full cover of Artemis Awakening and get some news about the forthcoming audiobook edition. Then join me and Alan as we continue our discussion of what makes the works of Clifford Simak so special.

JANE: You know, Alan, one of the things I love about Simak is that he doesn’t ignore the fact that humans – and non-humans – have a deeply spiritual side. This takes many forms, up to and including acknowledgment that there is a place for conventional religion – even in outer space.

Spirits from Otherwhere

Last week, when we talked a bit about Simak’s novel, Shakespeare’s Planet, I mentioned that one of the characters is a ship that has human brains installed in it. The three brains might be said to represent the three general ways in which humanity has tried to answer the great questions. There is the Grande Dame, who comes from a materialist point of view, the Scientist who is, well, scientific, and the Monk, who represents conventional religion.

A lesser author would have made the Monk a straw man for putting down religion as mere superstition – especially since the Monk admits he’d signed on for the mission because of his fear of death. However, Simak allows the Monk to be a voice for the part of humanity that never stops questing for something larger than wealth or knowledge.

ALAN: You’re right! This debate about, and deep appreciation of, spirituality is present to a greater or lesser extent in pretty much everything Simak wrote. I hadn’t realised that before. Thank you for the insight.

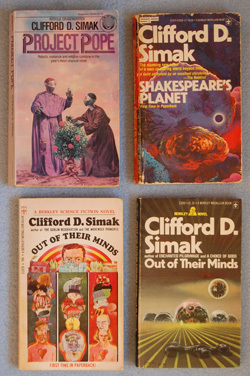

JANE: But I have run on. Last week you mentioned Project Pope. I would love to hear your thoughts about it. Did you like it?

ALAN: It’s a wonderful tale, often very funny and populated with Simak’s usual collection of raving eccentrics, some of them human, some of them not. But it has a lot more going for it than just that.

The story tells of a colony of advanced robots on a remote planet. They have set up a project called Vatican-17 which is an attempt to build an infallible, computerized pope. When the pope accumulates sufficient wisdom, it will be able to create a truly universal religion.

But first the pope needs data, lots of it. It has a team of Listeners, psychic humans, whose minds are sent out to explore the far reaches of time and space. Mary, one of the Listeners, makes an important discovery. She, quite literally, finds heaven. The robot cardinals fiercely debate the implications of Mary’s discovery.

JANE: And that’s only a small portion of the story… Psychology enters in. There are aliens. A mysterious Whisperer… And in the end, unlike many authors who would fudge when dealing with such a profound topic, a – for me at least – satisfactory conclusion.

ALAN: And for me as well.

JANE: Simak was not at all afraid of complex concepts, up to and including the nature of reality. Have you ever read Out of Their Minds?

ALAN: I know I’ve read it, but I retain no memory of it. Hang about – I’ll go and get it from my shelves…

…OK, I’m back. Here it is, published in England in 1973 by New English Library. The cover shows a picture of what looks like a brain on top of a spinal cord. It’s running down a road and is being hotly pursued by a knight in shining armour and a man on a donkey. I’m guessing that’s Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, but why would they be chasing a disembodied brain? Oh well, this is Simak so why not?

JANE: Why not indeed? What do you think about taking a break so you can read it, then get back to me? I’m already re-reading it. I think it would be cool if both of us were reading the same book on opposite sides of the planet.

ALAN: That’s a good idea. What a shame we can’t synchronise the page turns…

… Right. I’ve read it. It’s quite a short book – only 175 pages of quite large print. Most novels from that era are short, mere novellas by today’s standards. It’s definitely Don Quixote and Sancho Panza on the cover, but there’s no disembodied brain. That’s a shame. I was looking forward to that bit.

JANE: Oh, I don’t know… I think the brain disembodied is rather the theme of the book since what comes “out of our minds” is what the story is about, that and a great speculation on reality.

ALAN: Duh! What an idiot I am. Why didn’t I spot the visual pun? I certainly spotted it in the words of the title. Sometimes the most obvious things slip by unnoticed…

As you said before, it’s definitely a speculation about the nature of reality. The premise is that human beings, have created a fantasy world in their minds through their love of storytelling and somehow that fantasy world now has an objective existence. The hero, Horton Smith, has discovered this and now the beings from the fantasy world are trying to kill him to protect their secret.

JANE: Just as an aside, Simak must have liked the name “Horton,” since it’s the surname of the protagonist of Shakespeare’s Planet. Maybe these two Hortons are related. So, what did you think of the story?

ALAN: There are a lot of quite ingenious set pieces as Horton is placed in danger and has to get himself out of trouble. Unfortunately, never once does Horton hear a Who. I think Simak missed an opportunity there.

JANE: Indeed! Heaven knows, Dr. Suess would fit right in.

I wondered how some elements of the novel worked for you, since some of the references are very American – and not only that, pop culture American that was beginning to be dated even for an American like me by the time I read it.

ALAN: I didn’t really notice anything like that. There were quite a lot of old American comic book characters in the story, characters I’d never heard of. But the context made it very clear what was going on, so that didn’t worry me at all. Is that what you meant?

JANE: Well, yes. For example, Horton gets clued into the identity of the hillbilly couple who take him in when one of them mentions “Barney.” It’s only a mild spoiler to note that originally Snuffy Smith and Barney Google were linked in one comic strip. By the time I started reading it, Barney had been pretty much phased out, so I didn’t catch the clue until Horton spells it out.

ALAN: I’d never heard of any of them. But Horton does explain who they are and, while I’m sure I missed something because of my unfamiliarity with the characters, it didn’t really hold the story up at all for me.

By the way, I also took the opportunity to re-read The Goblin Reservation after you mentioned it the other day, and I think I’m starting to see a pattern.

The thing that really appeals to me about Simak is his sense of surrealism. He constantly juxtaposes commonplace things that simply don’t go together, and yet somehow the joins don’t show. It’s exactly the same effect you get from Magritte’s train roaring out of a fireplace or Dali’s soft watches hanging off a tree. They work brilliantly even though they make no rational sense. In many respects, Magritte in particular is a thoroughly naturalistic painter. It’s just that he puts things in odd relationships to each other. After all, why shouldn’t a landscape be part of the glass of a shattered window? Who’s to say it isn’t true? You’re looking at it through glass. Who says the landscape still has to be there when the glass breaks?

Simak does with words what Magritte does with pictures and it gets to me every time. Brilliant, spine-tingling stuff!

JANE: Absolutely! You mentioned the cover of your copy of Out of Their Minds. On one of my copies the artist went for a sort of psychedelic montage. It doesn’t work for the book (in my opinion) precisely because it tries too hard to be weird. Simak’s hallmark is that the weirdest combinations make perfect sense.

ALAN: And that really does sum Simak up in a nutshell.

JANE: Tune in next time when we will discuss…. Well, just wait and see!

May 7, 2014

Artemis Awakening: Sight and Sound

Over the last week or so, there have been a couple cool new developments on the Artemis Awakening front.

I was sent the full cover and discovered that it’s a wrap-around image! The original half-face design is expanded to become a full portrait. I particularly liked this because, in a weird and twisted way, this actually makes the cover even more true to the original design image suggested by my friend, Cale Mims. (See WW 10-02-13 if you missed the really interesting fashion in which this cover evolved.)

Full Cover Image

Why? Because now instead of one half-face, we have two… This makes for a neat variation of the old saying “half a loaf is better than none.” Right?

The cover also includes blurbs from hotshot SF writers Vernor Vinge, S.M. Stirling, Jack McDevitt, and David Weber… Basically, it’s a design to warm any writer’s heart.

Late last week, I discovered who will be reading the audiobook version of Artemis Awakening when I received an e-mail from narrator Joe Barrett. Mr. Barrett has read over two hundred titles from a wide variety of authors. He was getting in touch in the hope that I’d agree to chat with him about the book.

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m a serious audiobook junkie – fiction and non-fiction both – so I was excited. Not only would this give me a chance to make sure that names and all were pronounced closer to the way I hear them in my head but, also I’d have a chance to slip in a few questions about a profession that has interested me for a long time.

Even before we chatted, I had one of those fascinating behind the scenes looks. I had asked Mr. Barrett if he would recommend something he’d narrated, so I could get feel for his performance style. His e-mailed reply was fascinating: “I never know quite what to recommend – mostly because I don’t listen to my own titles. Can’t stand it.”

I actually understood. I’ve been told I’m a good reader and I honestly enjoy giving readings. However, on the occasions where I’ve had an opportunity to listen to my own recorded voice – whether of a reading or an interview – I’ve shied away. My voice sounds odd to me.

So I went and searched the Audible catalog for Mr. Barrett’s work, and quickly settled on The Tomb by F. Paul Wilson. My friend, Paul Dellinger, had recommended the “Repairman Jack” novels a couple of times, but I hadn’t gotten to them because I wanted to start early in the series. The Tomb was listed in the catalog as the first Repairman Jack novel.

Anyhow, Mr. Barrett and I made a date to chat last Sunday. My phone rang promptly at the agreed upon time and a now familiar voice said, “Jane?” Talking to Joe Barrett proved to be very easy. He started out by making sure he had the pronunciation of the various character names correct. From there we moved to one of the odder aspects of the novel – the “Interludes” that close each chapter. The Interludes are written in verse – sometimes rhymed, sometimes free – and contain idiosyncrasies that would provide no problem at all to a text reader, but offer a real challenge to a narrator.

My favorite was from the Interlude that appears at the end of Chapter 10. Visually, it’s simple enough: “Seek + (you shall) = Find.” If I were doing this as part of a live reading, I’d read it as “Seek, plus, you shall, equals find.” Where the parenthesis occur, I’d sketch them in the air with a finger.

Mr. Barrett wouldn’t have that option. We agreed that having him include the punctuation verbally would interrupt the flow – as well as being jarring, since he wasn’t reading the punctuation elsewhere. We playfully considered reading the punctuation following the example of that comic – you know who I mean, the one who made sounds for all the punctuation marks – but laughed that off as just too silly.

In the end, we decided that the parenthesis would need to be ignored, as would those passages that ended with a trailing line of dots…. Pity…. But sometimes one form demands concessions that another does not.

The Interludes also originate from a variety of points of view. Mr. Barrett was on target with those we discussed but, to make life easier for him, I agreed to e-mail a list of attributions so he could match voice to point of view as appropriate.

In the course of our chat, I learned a bit about how Mr. Barrett works. He has narrated for a variety of companies – including Blackstone Audio and Audible – and has his own home studio, complete with professional quality mike, recording equipment, and sound-deadening equipment. His professional background includes acting, so he doesn’t just read, he performs.

He reads the entire book in advance, looking for possible typos. He checked these with me in advance, just to be sure that he wasn’t mistaking as typo a deliberate stylistic choice. In most cases, he had found typos (to be fair, he was working from an advance copy, not the final manuscript). However, in two cases, I was able to set him straight as to why I had chosen a particular word. (I thought everyone knew what a dhole was… but the copy editor also flagged this.)

I really appreciated his attention to detail and found myself wondering if I would listen to the finished book. I’m still not sure. I know how the characters sound in my head, how they interact. I’m not sure I want to superimpose someone else’s voice. On the other hand, I do love audiobooks and it might be interesting. I guess I’ll find out down the line…

May 1, 2014

TT: Simak — Looking Behind the Words

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back one, then amble along the stacks and let me know what libraries mean to you. Then join me and Alan as we continue our journey into the weird and wonderful worlds of Clifford Simak.

JANE: Last week we were discussing the works of Clifford D. Simak. We talked a lot, but I feel we barely scratched the surface of what makes him such a fantastic writer.

From Cities to Shakespeare: Is Nothing Sacred?

ALAN: I agree. Humour was always one of Simak’s major strengths. He was never totally serious even in his totally serious books – there was always a lightness of touch running through his deeper, more thoughtful works. But sometimes he just went for straight comedy, and of course he did it brilliantly. They Walked Like Men is an aliens-invade-the-Earth story, but it’s quite unlike any other such story you have ever read.

(WARNING: A bit of a spoiler coming up). The aliens can turn themselves into any shape they like, though in their natural form they look like bowling balls. Initially, most of them turn themselves into money which they use to buy up lots of real estate – taking over the Earth by semi-legitimate means! Unfortunately the aliens have a serious weakness, they find the smell of a squirting skunk to be absolutely the most marvellous perfume ever. So defeating the invasion is simple. Just travel through town with an angry skunk in tow, and soon all the money in the bank will turn back into eager bowling balls rolling down the road in rapture.

JANE: Oh, yes! I need to re-read that one. The resolution is silly – but the story is not.

ALAN: Indeed so, and it is a measure of Simak’s skill that he can carry such an absurd story off quite brilliantly. It still makes me chuckle even today.

JANE: Humor is a tough thing to pull off because what one person finds funny, another does not. However, Simak’s humor works for me, perhaps because it’s whimsical, even in its more overt moments.

ALAN: Simak has been called a bucolic or pastoral writer and there’s a ring of truth in that. His most successful stories have a wistful nostalgia that harks back to simpler times and simpler people. Often there is a yearning for past glories. His two most successful novels, City and Way Station, are perhaps the epitome of this attitude.

City is a fix-up novel built from a series of stories. It is set in the far future. People are long gone from the Earth. Only the dogs they loved and the robots they built are left to tell each other the old stories and to wonder whether human beings ever existed at all.

JANE: Pastoral and nostalgic are not automatically the same thing but in Simak, you’re right, the two are often linked. If I recall correctly, one of the elements in City is speculation on how big cities would no longer be necessary in a future where everyone had their own personal flying machine. This was bucking in the face of common SF fiction and artistic tropes where towering cities and flying machines seemed inevitably linked.

I think this is a good example of how Simak was both pastoral (showing a preference for a rural setting and lifestyle) and cutting edge SF, because he thought about the implications of how technology would change the manner in which people lived.

Way Station is a gem… I think it’s Jim’s favorite Simak novel. You beat me to it, so you get to tell about it first!

ALAN: Way Station is about a veteran of the American Civil War. He is the caretaker of a secret way station, a transfer point for aliens journeying to and from mysterious destinations. Inside his way station he never ages, though the time he spends outside the station does count against him. He makes many friends among the aliens who pass through. He learns a lot about the nature of the universe and they learn about the nature of the Earth. But the outside world is snooping around. His longevity is arousing suspicion and a crisis is fast approaching.

JANE: Enoch Wallace is a wonderful character, simple but possessed of a deep, sophisticated wisdom. Again, under the guise of pastoral simplicity, Simak takes on some serious questions, including what is it at the heart of human nature that must be changed before peace is possible. A lovely book and one that fully deserved the Hugo it won in 1964.

Simak has often been criticized for being “bucolic,” as if this meant he was unwilling to face the challenges of the world, but I firmly believe that this was far from the case. As Carter Horton, the protagonist of Simak’s novel Shakespeare’s Planet says, “It seems that our species at times may hold an almost fatal fascination for the past.” This “fatal fascination” is hardly passive nostalgia.

I encountered Shakespeare’s Planet in a rather odd situation. Would you like to hear about it?

ALAN: Yes please – somehow you, Simak and odd situations seem to go hand in hand. It all feels perfectly right!

JANE: I think I’ll take that as a compliment…

Shift the dials of the time machine slight forward. I’m a little older, though still in my teens, and it’s during the school term. I’m sick enough that not only am I permitted to stay home from school (a rare occasion) but I’m downstairs in my parents’ room so I can watch the television.

My mom comes home with a stack of paperbacks for me. She knows I like SF, but at that point doesn’t read any so it’s great good luck that one of her random choices was Shakespeare’s Planet by Clifford Simak. It’s possible she picked it for the vaguely literary title. If she expected me to be getting a little covert education she was right, but not the sort she might have intended.

The book was solidly weird. It featured an odd assortment of characters: a couple humans (from not only different places, but different times), a robot, an alien, and a spaceship with human brains installed in it. Oh! And a quite possibly insane human who called himself Shakespeare and is now dead, but remains a vivid character through the journal entries he left behind.

All of them are stranded on a planet where once a day some powerful force strips their minds down to the barest elements. This God Hour was so strange that the first time I read the book I credited the high fever I was running with the weirdness. I re-read it later. I was wrong. It really was that weird.

ALAN: I think it’s possibly the strangest book I’ve ever read. Simak had a genius for putting the oddest elements together and making a coherent story out of them. He proved it time after time. Shakespeare’s Planet is probably one of the more extreme examples of this technique, but it is by no means alone.

JANE: Oh! I’m so very glad it’s on your “likes” list, too!

The book wasn’t all special effects weirdness. Far from it. For a book published in 1976, it contained some neat SF speculation. The robot, Nicodemus, has multiple brains that enable him to function in a multi-purpose fashion. Today, where we’re accustomed to hardware and software, just how innovative this idea was would slip by most readers, but, in 1976, robots (and often computers as well) were single-purpose items. When software was first introduced onto the general market, I immediately thought of Nicodemus and understood what was going on.

ALAN: Simak’s robots were always highly sophisticated, utterly different from the clanking monstrosities of traditional SF and different again from Isaac Asimov’s mechanistically sophisticated but philosophically quite shallow creations. I think Simak always regarded his robots as being self-aware, an idea that writers like Asimov played with but never properly came to grips with. And it is this self-awareness that lies behind Project Pope, probably one of Simak’s most profound novels, though the story is told in his normal, pastoral and often whimsical style, which makes the medicine slip down unnoticed.

JANE: I agree… Project Pope is also a wonderful gateway into discussing an aspect of Simak’s writing that we haven’t touched on yet. I’ll leave that for next time.

April 30, 2014

Crossing the Threshold

I’m curious. Did a library, public or private, play a role in your life as a reader?

Children’s Section

Last week, in the course of discussing our first encounters with the works of Clifford Simak, Alan Robson and I tangented off into recollections of our earliest crossings between the “children’s” and “adult” sections of the library. I was pleased when several of those who chose to comment mentioned their own First Encounters of the Library Kind.

When I bopped into the library this past weekend to pick up my hold on Naruto, volume 65, a DVD of Galaxy Quest, and several magazines I’m checking over before actually subscribing, I found myself wondering what role libraries play in readers’ lives these days.

I’ve been a library junkie pretty much as long as I’ve known libraries existed. At first I went only for books. Then one summer I discovered that libraries also had record albums. (This being in those days of yore when music was magically pressed into black vinyl.) I believe that, among us, my siblings and I kept out several favored albums out for the entire summer. The library also had collections of the comics I’d previously encountered sparingly doled out in the newspaper. Now, at last, it was possible to read the evolution of various characters. Non-fiction was less attractive to me in those early days but still, occasionally, I’d take out a book about some art or craft that interested me.

Adult Section

I do much the same today. I take out novels, but I also take out armloads of research materials. I miss the old card catalogs, but computer catalogs do make inter-branch loans incredibly easy. I’ve typed my library card number in so many times that I actually have the fifteen digits memorized. With the resources offered by having the entire library system available to me for a few keystrokes and a little patience, I’ve explored works I might otherwise never have known were available.

I see lots of young parents in the library, but usually their arms are full of kids or books for the kids, not for themselves. I’ve garnered the impression that folks between their tweens and, say, early thirties, seem to have dropped out of the library scene, except when the need to pick up something related to a certification exam or suchlike drives them through the doors.

This isn’t just based observation when I’m in the library – after all, my hours are weird and erratic, as benefits my self-employed state. Instead, I’ve received the impression when I’ve mentioned something I’ve taken out of the library (ours has a pretty good manga collection), and co-hobbyists seem unaware of the option. So I’ve wondered… Has the library been replaced by the internet for a certain age group? If so, I think that’s a pity.

Using the library is nearly as easy as reading off the net. Many library catalogs are available on-line. That means it’s possible to order in advance, and only stop by the library to pick up the swag when it comes in. In some cases, as with audio books, more and more libraries are offering downloads. I take out several each week without ever leaving the comfort of home.

But I believe I’ll always enjoy trips to the library. There’s nothing like browsing through open stacks for discovering books you might not have otherwise found. When I was researching for my novel Child of a Rainless Year, I encountered Blue Cats and Chartreuse Kittens by Patricia Lynne Duffy, a non-fiction work about synesthesia. I was looking for another book on another subject entirely. Yet, this accidental find shaped some elements of my novel. Without that idle wander down the shelves, I never would have encountered it and my novel would have missed something special. It’s hard to have the same sort of impulse contact, even with the best search engine and most provocative series of links.

Some years ago, our library started shelving non-fiction for children side-by-side with adult books on the same topic. I think space considerations were part of the reason, but part was to tempt children to cross the line. This pays off for adults, too. Often the best way to learn about a new subject is to read a treatment for children. Terms are often better defined, providing a foundation from which to read further.

I know some people think there shouldn’t be a “Children’s” section at all. I can see the arguments for both sides. As with so many issues regarding what children should and should not be exposed to, I think that parental, rather than institutional, guidance is advised.

But I wander a bit far… How do you feel about libraries? Do you use them? Do you like how they are changing? Do you think the internet has made them obsolete, and that they should be replaced by rows of computer terminals?

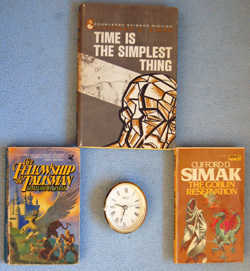

April 24, 2014

TT: The Writer from Wisconsin

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back one and enjoy a behind the scenes look at the process of translation. Then join me and Alan as we venture into realms twisted, weird, and utterly wonderful.

JANE: When we were discussing the various genres of SF and Fantasy a few months ago, I mentioned that a writer I particularly enjoyed was Clifford D. Simak. I was delighted when you said that you liked him too.

PInkness, Ghosts, Neanderthals, and Goblins, oh, my!

ALAN: Oh yes – one of my favourite writers. He seems largely forgotten now, but in his day he was a prolific and popular author. He made the mistake of dying just a few days before Robert Heinlein died and, in the fallout from that massive event, he passed largely unnoticed. I’m not even sure if his books are still in print. If not, they certainly should be.

JANE: I wanted to talk about Simak when we first mentioned him, but I got distracted and went off on a tangent.

ALAN: Isn’t that what it’s all about?

JANE: You bet!

I encountered Simak’s work back before I paid a lot of attention to who wrote the books I was reading. Books were their own wonderful things and the authors were incidental. Simak was the author who changed that for me.

Interested in time travel?

ALAN: Yes indeed. Time travel stories are my favourite stories.

JANE: All right, climb into the cabinet and swirl back the dials. It’s summer, sometime probably in the late 1970’s. I’m in my early teens and have discovered SF and F. Every week or so, my mom takes me and my siblings to the public library. There, we are permitted to take out as many books as we can carry. Because of this weight restriction, I have abandoned what was then called the “Children’s” section with its big, bulky hardbacks and gravitated toward the wire paperback racks. It is on one of these that I first encounter the works of Clifford Simak. After a while, I find myself deliberately searching for more. I finally run out of paperbacks. Then it hits me.

This is a library! That means it works like the school library! Up until then, I think I’d considered the public library as more a holiday place, not operating by library rules, if that makes any sense. I browsed, but never systematically searched. But now, my desire to read more Simak is heating my blood. I check the card catalog. I found Simak’s name, and bravely crossed the invisible line into the Adult stacks. I half-expected someone to pull me back from Forbidden Lands.

ALAN: I vividly remember my first excursion into the Adult Library. I think that for people like you and me, it’s a coming of age ritual, a rite of passage. Do you recall any Simak titles from your exploration of the Forbidden Lands?

JANE: I can’t say precisely which was my first, but I can remember an early favorite: The Goblin Reservation. It had everything: time travel, space travel, inventive aliens, goblins and their fey ilk, Neanderthals, and ghosts. It was a murder mystery, a tale of political intrigue, and, for those who insist that SF teaches nothing, it was also the first place I encountered the theory that Shakespeare did not write the plays.

I still enjoy it greatly. I could go on with more titles, but maybe I should turn off my time machine and give you a turn.

ALAN: Well actually I have a time machine of my own. (Wavy lines and eerie music…)

I was about twelve or thirteen. It was summer and my parents and I were on holiday at the seaside. I found Time Is the Simplest Thing in a pile of second hand paperbacks. I’d never heard of Clifford Simak, but the blurb attracted me and so I bought the book. I think it cost me sixpence, and it turned out to be the best sixpence I ever spent. I read the story with jaw-dropping amazement.

JANE: I haven’t read that one in years. Can you remind me a bit about the plot?

ALAN: Indeed I can. Earth has turned its back on space travel. The best they’ve ever managed is to send the minds of brave people out to the stars while their bodies remain on Earth. Shepherd Blaine is one such explorer. But on his latest trip, he encounters a telepathic alien which he describes as a pinkness. “Hi, pal!” it yells in his head. “I change with you my mind.” And it does. Blaine returns to his body with a bit of the pinkness in him. He immediately goes on the run – previous explorers to whom something like this has happened have been arrested and have vanished from view. They have been contaminated and they must be dealt with.

JANE: I remember! As soon as you said “pinkness” that did it. I bet you loved it.

ALAN: I was completely absorbed in the story. So much so that I never registered that my aunt and uncle and cousin had joined us for the day. Eventually it dawned on me that my cousin was talking to me.

“What’s the book?”

“Science fiction,” I mumbled, not lifting my eyes from the page.

“Who’s your favourite author?”

There was only one possible answer. “This chap,” I said, showing him the cover.

JANE: Have you ever read Time is the Simplest Thing again?

ALAN: I read the book again as an adult and I got a lot more out of it the second time around. It was still a gripping can’t-put-the-book-down story but this time round I realised it was an allegory about racial intolerance in America. People with paranormal abilities, those with a pinkness in their mind, are feared and ostracised by society. As Blaine runs and hides in the back blocks of America, the story fills with images of rusty, decaying small towns, angry mobs and the dangling corpses of lynching victims. This is a common theme with Simak – again and again and again his novels tell us that we are all in this together and that superficial things like a pinkness in the mind really don’t matter in the grand scheme of things. And so all his books have the strangest companions working together in harmony. The book you mentioned, The Goblin Reservation, is quite typical in this regard.

JANE: Absolutely! But the best thing about Simak is that he never lectures. I think one of the things I love the most about his works – and that I think has had a huge influence on what I choose to write – is how size or shape or species are not an issue in what makes for friendship or alliances.

Even when he latches onto what for other writers might become a really conventional trope, this emphasis on character connection makes the story special. In his Fantasy novel, The Fellowship of the Talisman, what could be a typical ho-hum quest story becomes special because of the extraordinary group which ends up looking for a talisman that may or may not exist. Have you read this one?

ALAN: Indeed I have, though it’s not one of my favourites. I think I’m just biased against quest stories…

JANE: Sigh… The members of the quest start out seeming rather typical: Duncan, a young knight and his childhood best friend, Conrad, who is a burly warrior. Then there’s a wardog, Tiny, and a warhorse, Daniel, and a little donkey named Beauty. Mind you, none of the animals are magical or can talk, but that doesn’t matter. They’re members of the Fellowship. Along the way Duncan’s group becomes even more diverse… But I don’t want to spoil the story by going into too much detail. Suffice to say that they become a group so varied and interesting as to make a combination of humans, hobbits, elves, and dwarves seem positively conventional.

And the resolution of the quest is not at all what anyone would expect…

ALAN: Simak had a lot of strings to his literary bow. Let’s look at some aspects of his work next week.

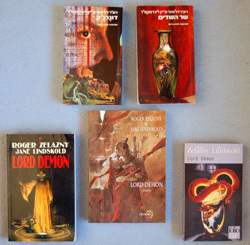

April 23, 2014

Translation: An Art, Not a Craft

Last week I wandered on about the delicate balancing act that an author faces when deciding how much detail to provide on a particular subject. In the course of this discussion, I mentioned that I was reading a book on horses translated from German that contained equestrian terminology that I had not encountered before.

A Few Translated Works

This spurred (yes, pun intended) an off-site Comment from a reader who is something of an expert on the subject of horses. She noted that she had never encountered – not even when she had been employed by German equestrians – some of the terms that I cited. We had a fun and lively discussion on the subject, and both concluded that translation involved a lot of decisions on the part of the translators.

Should these translators have noted that certain terms were more common in German equestrian circles than elsewhere? While this might have helped readers draw a line between areas of specialized knowledge, it also would have been a distortion of the original text – and one that could not be done with any confidence without the translators knowing precisely which English-speaking audience they were translating for, since British and American terminology can differ considerably.

My opinion — for what it’s worth – is that in this case the translators did their best. The collection they were translating was a series of short essays, meant to be read out of order, so they would have had to repeat their clarification over and over again. The book was clearly listed as a translation and even a mildly alert reader should have been able to detect that it was written from a German perspective, since the majority of the examples had a German cultural bias.

(Aside: I found this slant particularly obvious in the section on the horse in the Wild West, where the author the German author Karl May was given precedence, followed by the Franco-Belgian comic book character, “Lucky Luke.” John Wayne was mentioned in passing. Nothing wrong with this, just a strong indication of cultural bias.)

I have the good fortune to know several professional translators of literary works, and I decided to ask them for stories about the challenges they’ve encountered in the course of their work.

Rick Walter, whose recent translations of many of Jules Verne’s novels show far better than the stiff translations I encountered years ago why Verne was so popular and so influential, confirmed that even among “English” translators, different choices need to be made to reach specific audiences.

He offered me the following example:

In “20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEAS, penultimate chapter: one of the characters whips out ‘une clef anglaise’ to undo some bolts …

“– My SUNY Press translation renders the term as ‘monkey wrench.’

“ — William Butcher’s Oxford UP translation gives ‘adjustable spanner.’”

I’ve always wondered what a “spanner” was… Now I know what it means to “throw a spanner in the works.” It means to shove a monkey wrench in the gears!

But translators face far more delicate challenges than merely pulling out a dictionary, then plugging into the appropriate slot the appropriate term in a grammatically correct form. Cultures differ widely in forms of address or humor or swearing or myriad other things that, if translated literally, come across as stilted or just plain peculiar. The translator must constantly choose between being what I might call “accurate” in favor of being “right.”

I asked a couple of professional translators for examples of the challenges they have faced over the years. Tiina Nunnally, who became a Knight of the Norwegian Order of Merit for her work as a translator, said: “Translation always involves endless decisions, both big and small, and it takes years of experience to figure out how far to veer from the original without altering the intent and tone of the book.”

She continued: “So one of the biggest challenges — especially when dealing with fiction — is translating swear words. A few years ago I translated a Danish novel that was filled with profanities, and I had to make sure that all the curse words would have the same force in English as they did in Danish. In the Scandinavian languages, the strongest and most searing swear words all have to do with the devil — but the devil has almost no impact in English. Instead, all of our swear words have to do with God or sex or various body parts. So I had to come up with words that would have the same vulgar equivalence in English. The publisher sent the author (who had only a perfunctory knowledge of English) a copy of the translated manuscript, and he immediately sent me an irate email saying “What are all these ‘God’s doing in my book!” He had no idea that a ‘literal’ translation of all those epithets would have ruined his book in English… ”

(Aside: Look for Tiina’s work in Only the Dead by Norwegian author Vidar Sunstol, to be released this October.)

In translating Jules Verne, Rick Walter faced a different challenge.

“For me, the trickiest challenge is translating jokes. You wouldn’t know it from most of their English versions, but humor is a major element in Jules Verne’s novels-not only was Verne a chronic punster, his yarns are full of running gags, black comedy, slapstick, and social satire. Needless to say, these are the scourge of translators everywhere, and many duck the challenge altogether.

“One such mindbender is the witty tagline of Chapter 2 in Around the World in 80 Days. The French valet Passepartout has just met his new boss, a sedentary, robotic, anal-retentive Englishman named Phileas Fogg . . . and he marvels at the fellow:

“Un homme casanier et régulier ! Une véritable mécanique ! Eh bien, je ne suis pas fâché de servir une mécanique !

“A literal translation of the above would be: ‘A home-loving and regular man! A veritable piece of machinery! Well, I don’t mind serving a machine!’

“Well, I didn’t want to chicken out and skip the it; so, after hours of cudgeling my brain, I finally came up with: ‘He’s a homebody, an orderly man! A real piece of machinery! Well, it won’t pain me to have a domestic appliance for a master!’”

As these small examples show, the process of translating is rather fascinating… I wish I read another language well enough to read one of my stories in translation. It would be interesting to find out what I said!