Translation: An Art, Not a Craft

Last week I wandered on about the delicate balancing act that an author faces when deciding how much detail to provide on a particular subject. In the course of this discussion, I mentioned that I was reading a book on horses translated from German that contained equestrian terminology that I had not encountered before.

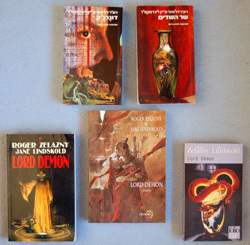

A Few Translated Works

This spurred (yes, pun intended) an off-site Comment from a reader who is something of an expert on the subject of horses. She noted that she had never encountered – not even when she had been employed by German equestrians – some of the terms that I cited. We had a fun and lively discussion on the subject, and both concluded that translation involved a lot of decisions on the part of the translators.

Should these translators have noted that certain terms were more common in German equestrian circles than elsewhere? While this might have helped readers draw a line between areas of specialized knowledge, it also would have been a distortion of the original text – and one that could not be done with any confidence without the translators knowing precisely which English-speaking audience they were translating for, since British and American terminology can differ considerably.

My opinion — for what it’s worth – is that in this case the translators did their best. The collection they were translating was a series of short essays, meant to be read out of order, so they would have had to repeat their clarification over and over again. The book was clearly listed as a translation and even a mildly alert reader should have been able to detect that it was written from a German perspective, since the majority of the examples had a German cultural bias.

(Aside: I found this slant particularly obvious in the section on the horse in the Wild West, where the author the German author Karl May was given precedence, followed by the Franco-Belgian comic book character, “Lucky Luke.” John Wayne was mentioned in passing. Nothing wrong with this, just a strong indication of cultural bias.)

I have the good fortune to know several professional translators of literary works, and I decided to ask them for stories about the challenges they’ve encountered in the course of their work.

Rick Walter, whose recent translations of many of Jules Verne’s novels show far better than the stiff translations I encountered years ago why Verne was so popular and so influential, confirmed that even among “English” translators, different choices need to be made to reach specific audiences.

He offered me the following example:

In “20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEAS, penultimate chapter: one of the characters whips out ‘une clef anglaise’ to undo some bolts …

“– My SUNY Press translation renders the term as ‘monkey wrench.’

“ — William Butcher’s Oxford UP translation gives ‘adjustable spanner.’”

I’ve always wondered what a “spanner” was… Now I know what it means to “throw a spanner in the works.” It means to shove a monkey wrench in the gears!

But translators face far more delicate challenges than merely pulling out a dictionary, then plugging into the appropriate slot the appropriate term in a grammatically correct form. Cultures differ widely in forms of address or humor or swearing or myriad other things that, if translated literally, come across as stilted or just plain peculiar. The translator must constantly choose between being what I might call “accurate” in favor of being “right.”

I asked a couple of professional translators for examples of the challenges they have faced over the years. Tiina Nunnally, who became a Knight of the Norwegian Order of Merit for her work as a translator, said: “Translation always involves endless decisions, both big and small, and it takes years of experience to figure out how far to veer from the original without altering the intent and tone of the book.”

She continued: “So one of the biggest challenges — especially when dealing with fiction — is translating swear words. A few years ago I translated a Danish novel that was filled with profanities, and I had to make sure that all the curse words would have the same force in English as they did in Danish. In the Scandinavian languages, the strongest and most searing swear words all have to do with the devil — but the devil has almost no impact in English. Instead, all of our swear words have to do with God or sex or various body parts. So I had to come up with words that would have the same vulgar equivalence in English. The publisher sent the author (who had only a perfunctory knowledge of English) a copy of the translated manuscript, and he immediately sent me an irate email saying “What are all these ‘God’s doing in my book!” He had no idea that a ‘literal’ translation of all those epithets would have ruined his book in English… ”

(Aside: Look for Tiina’s work in Only the Dead by Norwegian author Vidar Sunstol, to be released this October.)

In translating Jules Verne, Rick Walter faced a different challenge.

“For me, the trickiest challenge is translating jokes. You wouldn’t know it from most of their English versions, but humor is a major element in Jules Verne’s novels-not only was Verne a chronic punster, his yarns are full of running gags, black comedy, slapstick, and social satire. Needless to say, these are the scourge of translators everywhere, and many duck the challenge altogether.

“One such mindbender is the witty tagline of Chapter 2 in Around the World in 80 Days. The French valet Passepartout has just met his new boss, a sedentary, robotic, anal-retentive Englishman named Phileas Fogg . . . and he marvels at the fellow:

“Un homme casanier et régulier ! Une véritable mécanique ! Eh bien, je ne suis pas fâché de servir une mécanique !

“A literal translation of the above would be: ‘A home-loving and regular man! A veritable piece of machinery! Well, I don’t mind serving a machine!’

“Well, I didn’t want to chicken out and skip the it; so, after hours of cudgeling my brain, I finally came up with: ‘He’s a homebody, an orderly man! A real piece of machinery! Well, it won’t pain me to have a domestic appliance for a master!’”

As these small examples show, the process of translating is rather fascinating… I wish I read another language well enough to read one of my stories in translation. It would be interesting to find out what I said!