Jane Lindskold's Blog, page 142

February 6, 2014

TT: Revolts, Plays, Picnics, and Novels, Too!

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back one to where I answer a bunch of questions about how I self-edit. Then come back and join me and Alan as we look at the reaction Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries – and what that has to do with bicycle clubs.

JANE: Last time we dealt with Henry’s motivations and mechanics for dissolving the monasteries. However, you’ve promised that this was far from the end of that matter. I can hardly wait!

What Does This Have to Do With Anything?

ALAN: Not surprisingly the dissolution of the monasteries did not go down well, and there were several revolts over the next couple of years. These are known collectively as the Pilgrimage of Grace. Many religious houses were charged with helping the rebels. The heads of these houses were declared traitors and summarily executed. The monks and nuns were forced out into the community and left to fend for themselves (it’s unclear whether or not they were required to remain chaste) and, of course, all the assets of the houses were confiscated.

JANE: Did any monastic houses survive?

ALAN: Yes, some of the richer ones who could prove they were not involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace and whose annual income exceeded £200 continued to exist – largely because they were rich and could afford to pay the king what I can only describe as protection money.

The King’s Commissioners paid regular visits to these monasteries and much informal pressure was applied to persuade the abbots to increase the stipend they paid to the crown. Resistance was largely futile – the Abbot of Glastonbury showed a distinct disinclination to part with any of his assets. He was executed and his monastery (probably the wealthiest in England) was destroyed. A cynic might say this happened because Glastonbury was one of the wealthiest monasteries in England…

The whole process took about four years and more than 800 monasteries were dissolved.

JANE: This all sounds dramatic enough to turn into a novel or two.

ALAN: And someone has done exactly that. There’s a wonderful series of historical mystery stories by C. J. Sansom that are set during these turbulent times. The first book is called Dissolution and the events in it take place in 1537. Matthew Shardlake is a lawyer and a long-time supporter of Reform (though he is starting to have his doubts about its implementation). He is sent by Thomas Cromwell to investigate a horrific murder at the monastery of Scarnsea on the Sussex coast. The monastery itself will soon become a casualty of Henry’s policies and is in the process of winding down. The combination of murder mystery with the social, political and theological intrigues of the time makes for utterly enthralling reading. Sansom brings the times marvellously alive and I recommend his books unreservedly.

JANE: They do sound good. I’ll need to look for them.

ALAN: Henry’s policies have left a legacy that is still visible today. All over England, monastic ruins stand as mute witnesses to Henry’s excesses. The remains of Fountains Abbey are a prominent landmark which is close to Halifax in Yorkshire where I was born. I remember picnics there with my parents, and a school trip where the class was told the story of the dissolution of the monasteries while we stood in the shadows cast by the tumbled walls of the Abbey itself. That was a very effective way of bringing history to life!

JANE: That does sound like a wonderful field trip. I’m always awed about the sort of historical trips you could take where you grew up. I lived in Washington, D.C., so I went to some wonderful places, not only in D.C., but in Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, but written United States history goes back only a few centuries… Even here in New Mexico, where, because of Spanish settlement the writing historical record goes back much further than on the East Coast, our history is only a few centuries old. Ah, but I tangent.

ALAN: You live in the New World, but these days I live in an even Newer World than you do. Here anything more than about 100 years old is considered truly ancient. That’s quite a contrast to the area where I was born and brought up in England, where we can trace our history back for more than a thousand years…

But to get back on track – the playwright Alan Bennett, he of The Madness of King George fame, wrote a delightful play for the BBC. It was called A Day Out and it concerns a bicycle club who have a day out cycling from Halifax to Fountains Abbey. The Abbey itself has quite prominent part to play!

JANE: Does the abbey serve only as location or is this a time travel story?

ALAN: No, there’s no time travel involved. Much of the play takes place among the ruins of the Abbey and it makes an elegant backdrop to the action.

JANE: Darn… I had visions of monks on bicycles riding off to the future where they could either be poor, chaste, and obedient or disobedient, wealthy, and unchaste – but not be held to a double standard. Maybe I can write that story someday.

ALAN: Let me know when you do. I want to read it!

JANE: More seriously, the reality those monks and nuns faced seems very grim nor, do I imagine, would their situation have gotten much better after Henry VIII shuffled off this mortal coil. Religious wars did not end with his death – in fact, they intensified. They’re nearly as confusing to an American as Henry VIII’s string of Anns and Catherines. Perhaps we can wend our way into that maze another time.

Next week, though, I have a question or two about some more mysterious English terms.

February 5, 2014

How Do You Edit It?

What am I doing right now? I’m immersed in self-editing AA2. It’s an intense process and, while I’ve touched on it in bits and pieces in the past, I had a series of questions from one of the newer readers of these Wanderings that made me think this would be a good time to take a different look at the process.

Sonata for Red Pencil and Paper

So here are the Questions.

“I know you don’t outline. But do you edit at all as you write? Do you do an entire draft and go back through it? How many times do you go through the book before it goes to an agent or editor? How far along is it before Jim reads it? How much does his feedback factor in? What other first readers do you count on?

Answer 1: I don’t outline. Really. Before I start a novel, I have a general feeling about it, but I really don’t know where it’s going until shortly before I get there. However, I do organize, pretty stringently. I call this process “Reverse Outlining.” Since I wrote about that process back in July (WW 7-24-13), I won’t go into details here.

Do I edit as I write? Yes. However, this tends to be minimal (altering a word or two). I’ve known writers who begin their writing day by re-reading what they wrote the day before and carefully grooming it. Then they move onto the next day’s writing. I do that occasionally, but usually only when I need to jog my memory as to where I was last session. Otherwise, I pick up where I stopped and go on from there.

Answer 2: Yes. I pretty much write an entire draft of a novel (or short story) before I go back through it. There are two exceptions. One is if I have a major interruption in the writing process, such as a long trip or a several weeks’ break because another writing obligation comes up. Then I need to go back and find out what I’ve actually written, in contrast to what I’d thought about writing. If my reverse outline is up to date, sometimes I just consult that.

Answer 3: How many times do I go through a manuscript before I send it off to my agent or editor? At least twice, often three times. The first review is on the computer. In this reading, my primary goal is to fill in details I left out. I’ve never been a writer who slows down the flow of a good yarn because I can’t remember the color of a secondary character’s hair or the day of the week or suchlike. When I come to such a point, I slam in square brackets, sometimes with a note to myself inside them like [color?] and keep going with the story.

This is also where I check continuity and tighten prose, removing duplicate descriptions and other elements that creep in when (for the writer) weeks have passed, when for the reader only a chapter or so has gone by.

I do my second read-through on a hard copy of the manuscript. This is a step I never, ever, ever skip. I seat myself squarely at the table with no fewer than two red pencils at hand and a red pen in case I want to write an additional paragraph. (I write faster in ink than in pencil.) I am as ruthless as possible in this reading: cutting, augmenting, rephrasing, whatever it takes.

Back when I was first getting started, I’d often read the manuscript aloud. There’s no better way to catch clunky sentences or omissions. I still do this with short stories. An added bonus is that reading a manuscript is great training for giving public readings.

Another reading of sorts occurs when I am incorporating my changes into the manuscript. This forces me to take another close look.

Answer 4: How far along is the manuscript when Jim reads it? How much does his feedback factor in? Jim doesn’t see the manuscript until I’m done with these first two or three readings and have made all the corrections. Basically, he doesn’t see the story until it’s as good as I can possibly make it.

Occasionally, if I like a particular line or something, I might read it to him. He’s very patient about hearing parts of novels with no context. However, I don’t look for feedback as I write.

Jim’s feedback is very important. Although it might surprise those who think of archeologists as mere grubbers in the dirt, a lot of the work involves writing. Since Jim’s a project director, he also does a considerable amount of editing. So I’m really lucky in that my first reader is both a writer and a professional editor.

If I disagree with one of Jim’s comments, I make a note of it. If I hear the same comment from another reader, then I take it as a given that I have failed in some way to communicate my intent. Then I will do my best fix the error.

Answer 5: What other first readers do I count on? This varies from book to book, based on who has time and who I can trust to be ruthless with me, if such is called for. Much as I love hearing that I’m someone’s favorite author or that I write wonderful books, such praise isn’t helpful when a book is still in the evolving stages. Heck, even questions about a book that’s published can be useful. Sometimes, if I’ve left something out, I can put it in later in the series (assuming there is a series). Reader comments aren’t always useful because some readers want to dictate a direction for the series that I never intended, but I’d rather have them than not.

Another important thing I look for in a first reader is a familiarity with science fiction and fantasy as a genre. Readers who don’t know the conventions of the genre may praise where praise isn’t really due. (I remember a long-ago colleague who was fascinated by my use of the term “credits,” rather than money in Smoke and Mirrors.) Or they may get flummoxed by some standard genre element and want more explanation than is due.

Answer Six: Wait! There was no Question Six.

Time for me to haul out the red pencils and get back to work.

If you’re interested in other bits I’ve written about revising, editing, and taking criticism, you might enjoy the Wanderings for 2-08-12 (“When It’s There… But It Isn’t”) and 2-15-12 (“Two Heads or Too Many Cooks?”).

This doesn’t mean I don’t invite other questions. By all means, bring ‘em on!

January 30, 2014

TT: Dissolving Monasteries

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back one and read about a really cool amateur art contest for which I’m both sponsoring a prize and writing a story. Then join me and Alan for a stroll through the ruins of the English monasteries.

JANE: You promised to tell me about the dissolution of the monasteries under King Henry VIII. I know it occurred, but that’s about it. What happened?

King Henry’s Solvent

ALAN: It’s not widely known, but Henry VIII was a student of alchemy. As a result of his studies, he developed a universal solvent that would dissolve anything at all. Since he obviously couldn’t find a container to keep it in (it was a universal solvent after all), and not wishing to have it go to waste, he used it to dissolve all the monasteries in England. It turned out that his universal solvent was also an aspect of the philosopher’s stone, that mysterious entity that transmutes base elements into gold. Thus the dissolved monasteries made Henry, and therefore England, very rich indeed!

JANE: You’re being silly again aren’t you?

ALAN: Yes and no. The story that I just made up about universal solvents and philosopher’s stones is obvious nonsense, but it is nevertheless allegorically true. Henry found himself head of a Protestant church in what was now (at least nominally) a Protestant country. The Catholics were more and more being seen as enemies of the state. Indeed, Henry specifically formulated laws that allowed him to declare Catholics who opposed his policies as traitors, and have them executed. That’s the mechanism he used to dispose of Thomas More, if you recall. Henry’s exchequer was also emptying rapidly, and the monasteries and nunneries were often very rich establishments. Put those two elements together and you can see that Henry had very good reasons for getting rid of the monasteries. Nests of traitors could be dispersed and money would pour into the country’s coffers! What could possibly go wrong?

JANE: Ellis Peters’ “Brother Cadfael” mysteries give a very good sense of how, even as far back as the civil war between Stephen and Maud, the monasteries wielded temporal as well as religious authority. I can see why Henry would have wanted to eliminate a considerable power block.

Those books also give a strong sense of how the monasteries had gone from being self-supporting enclaves to generating wealth from their various businesses – farms, smithies, and the like. Then, too, people who had lived wild lives would often donate property or sums of money to monasteries in return for prayers. Well-managed – and since monks were often far better educated than the bulk of the population, all of this was likely to be done – this could grow into a considerable fortune.

ALAN: Quite true. Also the monasteries had a spiritual income obtained from tithes or taxes deriving from the local parish churches. After several hundred years of raking in all this income, some of them were sitting on quite substantial nest eggs.

All over Europe, cash-strapped kings, both Catholic and Protestant, were casting more and more covetous eyes on such a ready source of income to support their armies and fortifications and internal squabbles. Henry was by no means alone in his confiscation of these resources, but perhaps, in his own eyes at least, he had more justification than most.

JANE: Why would he have more justification than the European monarchs?

ALAN: Because he saw the Catholic monasteries as hotbeds of insurrection opposing his Protestant reforms. This point of view was less true of the largely Catholic European kingdoms

JANE: How were the dissolutions actually handled? Surely the monks didn’t just say “Oh, right. If you don’t want us, we’ll leave now.”

ALAN: It started in 1535, when the King’s Commissioners visited all the monasteries and nunneries and surveyed their status and income. The commissioners, well aware of the king’s ultimate goal, made very sure to bias their reports and were not very diplomatic in their approach. Many complaints were made about their bullying tactics, but these were all ignored.

JANE: Because, of course, those complaints would have been made to officers of the king. Go on!

ALAN: Once the information had been gathered, an act was passed declaring that all institutions with an income of less than £200 a year would immediately be dissolved. The abbots and abbesses were offered a pension and the monks and nuns were given the choice of transferring to one of the few remaining houses or going out into the world freed from their vows of poverty and obedience (so that at least they would be able to earn a living). However they were not freed from their vow of chastity! They must have found that quite frustrating…

JANE: I don’t follow this. Why would Henry have started by closing down the lower income monasteries? Those would seem to be the ones that were actually following their vows of poverty. And probably those of chastity and obedience, too!

ALAN: The monks might have been obeying their vows far too well. I think Henry saw them as being too poor to provide him with a decent long term income. Therefore, being a pragmatic man, he just liquidated them immediately, leaving him free to concentrate on squeezing regular payments out of the richer ones.

JANE: Fascinating!

ALAN: Some 300 or so religious houses were closed down under the terms of the act. Their assets were forfeit to the crown – the land was sold and the gold and silver were melted down. The fabric of the buildings was given to the local villagers who immediately began pilfering the structures to build fences for their fields and houses for themselves. The few remaining monasteries had to pay an annual fee to the crown to ensure their continued survival.

JANE: I suspect this is what Louis meant in the Comments back on December 12, when he wrote: “Ah! Now we get to the meat of the matter: why later generations of Englishmen could boast that they were ‘rich enough to buy an Abbey.’”

However, I admit, I’m rather confused the rest of his statement: “And, perhaps, why in later years ‘Abbess’ was not a term of endearment.”

Maybe we can appeal to Louis and the rest of our readers to answer this question.

ALAN: That sounds like a good idea. But we haven’t finished with the topic yet. The dissolution of the monasteries has had a profound effect on the English psyche and it has provided inspiration for any number of fascinating things – revolts and novels, plays and picnics. Let me tell you about them next time.

January 29, 2014

Cover Art Contest

Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve wandered down a strange and interesting new road. It began with an e-mail from my friend Scot Noel asking if I’d mind taking a look at some information he was putting together for a cover art contest he and his wife, Jane, had decided to sponsor on their website, ScienceandFantasyFiction.com .

Color Your Worlds

I did. I liked what I saw. Both cover art and amateur art hold great interest for me. Next thing poor Scot knew, I was asking if I could get involved.

(Oh! You can learn about how Scot, Jane, and I became friends on the Wednesday Wandering for 10-24-12. Not surprisingly, it involves both art and storytelling.)

The contest is just getting started. Take a look at www.sffcontest.com for details. I’m not going to be a judge, but I am sponsoring one of the prizes. I’m also going to write a short story based on one of the winning pieces. The contest web pages are works of art in themselves. (Scot and Jane are professional website designers.) The pages also very clearly spell out the guidelines, both technical and artistic. If the contest cover page doesn’t give you enough detail, try the FAQ. We tried to anticipate more specific questions there.

The featured art is by my friends Rowan Derrick and Tori Hansen. As well as being very good, their contributions show the wide range of approaches that are welcome.

While you’re browsing, don’t forget to take a look at the Science Fiction and Fantasy Fiction site. It has reviews, short fiction for free download, and some other interesting stuff.

So, what’s an author doing getting involved in an art contest? Is this where you learn that I paint and draw in my spare time? Actually, the reason I’m getting involved is precisely because I can’t paint or draw. People who can do so seem downright magical to me.

Also, I’ve always been thrilled when fans show me art that my stories have inspired. I’m looking forward to letting someone’s art inspire a piece of my fiction. Additionally, Scot and I plan to have a chat or two about how visual art can inspire written art.

So, I hope some of you will choose to enter. Feel free to pass this information along to any of your artistically inclined friends. Pieces will be posted on-line, so even if your art doesn’t win, you’ll have the pleasure of sharing it with a different range of viewers!

So, ready? Set! Get out your pencils and start drawing!

January 23, 2014

TT: Creative Impact

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back one and have a piece of cake as we celebrate the fourth anniversary! Then join me and Alan as we continue take a look at some of the ramifications of sailing in pirate haunted waters.

JANE: Last time I mentioned that second-hand bookstores and libraries had an impact on the creative process of writing. Can you guess what it is?

Threat to Creativity

ALAN: I’m sorry, but that’s got me completely flummoxed! The only thing that comes to mind is something vague about second-hand ideas, but I’m sure that’s not what you mean. So what is the creative impact?

JANE: The creative impact is that publishers are less willing to take gambles because they are less certain of selling copies. I can’t name names, because most of what I know was told to me in confidence, but I have spoken to several award-winning, popular authors who were basically told: “Write for me in your X universe/series and we’ll buy it. Otherwise, sorry, not interested.”

ALAN: That explains a lot. I get so sick of never-ending series that really should have been put out to pasture many books ago. I simply don’t understand why they continue to sell. There comes a point where the stories turn into writing by numbers; just hack work.

JANE: And that’s a situation that’s particularly sad when a writer finds himself or herself becoming a hack within a universe they created and once loved.

I’m sure if Roger Zelazny was still alive, he’d find a lot of interest in more and more Amber novels. That’s great for fans of Amber, but it would mean that wonderful books like A Night in the Lonesome October would never get written.

ALAN: Much as I love Roger’s work, I really wouldn’t have wanted to see any more Amber books. That universe was written out. Like you, I much preferred to see him working on something new and fresh rather than old and tired.

JANE: Me, too.

ALAN: Of course, just like DVDs, books are now available in electronic form. Many providers of e-books try and stop people from copying them by encrypting them in a special way – it’s called DRM (Digital Rights Management), and the practical effect is that you can only read the book on the e-reader you used to purchase it. You can’t transfer the book to another device, which effectively prevents people from copying the book illegally. The downside is that if your e-reader breaks or if you buy a new one with bigger bells and louder whistles, you have to buy the book again. And again, and again… There’s a school of thought that says this actually harms sales since many people simply refuse to buy e-books that come with DRM.

JANE: My opinion on DRM has changed. Initially, I was all for DRM because, as we discussed last week, piracy seriously hurts writers. However, once e-books could be read on different media, DRM seemed like a bad idea to me for all the reasons you mentioned. That’s why if you buy one of my handful of e-books directly from me, they will not have DRM.

Sadly, too, even if a book is protected by DRM, determined pirates will break it – and brag about how clever they are. I get depressed just thinking about it.

ALAN: Tor, which publishes a lot of your books, now has a policy of not attaching DRM to their e-books. Unfortunately they only sell e-books through stores like Amazon, and Amazon is a law unto itself. More often than not they attach DRM to Tor books even though Tor tells them not to. I’ve been caught in this trap more than once and I have several Tor books which proudly proclaim in the small print that they are DRM-free. Nevertheless Amazon has put DRM on them. Tor seems completely powerless to get Amazon to stop doing this, and Tor never answer their emails when I complain to them about it. Consequently I no longer buy e-books published by Tor.

JANE: Well, I’ll pass this along to my editor, Claire Eddy, at Tor. She’s a good listener. Maybe she’ll know what we can do.

ALAN: Wildside Press e-books and Baen e-books are also DRM-free. Both these publishers sell their books directly as well as through Amazon. I always make a point of buying e-books directly from Wildside and Baen and I’ve spent a lot of money doing just that. If Tor ever starts selling e-books directly, I’ll certainly start buying from them again.

JANE: I’ll definitely pass this along. I know that Patrick Nielsen Hayden, one of Tor’s senior editors, is avidly interested in how the Internet is changing publishing. It’s completely possible he has no idea what Amazon is doing. E-mails like the one you sent often get lost as they’re handed up the line.

ALAN: Many individual authors are now selling their e-books on the internet as well. I’ve bought lots of DRM-free books from Matthew Hughes, Mike Resnick, Rudy Rucker, and Jack Vance. And in this case, of course, the authors get to keep all of the money!

JANE: Not quite all, especially if the writers sell through Amazon or Barnes and Noble. Then there is a small commission. Also, upfront expenses and investment in time are much higher for an author who wants to do an e-book than many imagine until they start working on an e-book.

I kept careful track of my expenses when I did my three e-books. It took a good many sales for them to earn out what I’d spent. This was even though I think my expenses were lower than average. I also must stress that many people will say: “But you can do it all yourself and it’s free.” That’s not completely true. There’s an investment of time, time that gets taken away from writing.

ALAN: Oh gosh yes! I’ve turned some of these tangents into an ebook and I was astonished to find how much time it took. It’s tedious and laborious. And of course it doesn’t help that I’m an incredible pedant who tries very, very hard to cross all the i’s and dot all the t’s. You wouldn’t believe how much time that eats up. It gave me a whole new appreciation for just how hard professional editors must work.

JANE: Well, since you’ve mentioned it, let me remind our readers that they can download the fruits of your labors for free from your website http://tyke.net.nz/books.

E-books are also touted as the way authors can publish those books that the professional outfits won’t take because they’re too daring or not in a popular series or whatever. This is lovely in theory, but the author still needs to put in the time writing the book, getting it ready for e-book and/or POD publication, and then promoting it. Not many writers are so rich that they can afford a year or more away from paying work, especially if writing is their primary means of support. This leads to authors taking on other jobs – either outside of writing or writing something to pay the bills.

Once again, the field suffers.

Worse, whether reprints or new fiction, people start pirating those e-books, too… It’s actually pretty disheartening.

ALAN: That’s depressingly true. But nevertheless, I think that the British DVD assumption that the purchaser of the product is basically honest is the way to go. If you start by assuming that everyone is a pirate, both you and your audience are left with a bit of a nasty taste in the mouth.

JANE: I agree. I’ve had to reach for the mouthwash, especially when well-meaning friends send me links to where my books have been pirated. Still, I agree with you that if people feel it’s assumed they’ll cheat, then I think they’re more likely to feel clever when they figure out how to pull the cheat off. It’s much harder when they realize they’re just as scummy as someone who pockets candy in a Mom and Pop store that’s having trouble meeting its bills.

ALAN: The remedy lies with the publishers themselves. I hope that the approach taken by Tor and Baen starts a trend. Tor’s implementation may be flawed, but at least their heart is in the right place.

JANE: On that optimistic note, I need to go write. I’m immersed in revising AA2. It’s quite absorbing.

January 22, 2014

Four Years Old!

Today we’re celebrating the fourth anniversary of the Wednesday Wanderings!

Kung of Kungs

Why Wanderings? Because when I started writing these, I wanted to be able to focus on whatever seemed like fun at the moment. I’d done a series of blogs for Tor.com. While I enjoyed them, there came a time when I got weary of writing about, well, writer stuff. When I decided the time had come for me to dive into the blogosphere, I didn’t want to raise the expectation that I’d always be offering wit, wisdom, writerly advice and professional news items.

(Why “Wednesday”? It alliterates. Also, Wednesday gives me time to review reader comments and think about them over the weekend before starting to draft the next week’s piece.)

So, while the fifty-some articles I’ve done in the last year have often dealt with writerly issues, I’ve also felt free to talk about outings I’ve taken, my garden, books I’ve been reading, and even some of my craft projects.

The funny thing is how often I do end up talking about topics that tie into writing, whether directly or indirectly. Part of the reason for this is that I genuinely love what I do – and, because of my early training as an English major (and experience as an English professor), I also enjoy thinking about the whys and wherefores that lead to the creation of a story.

In four years, I’ve written well over two hundred essays. (I hate the word blog… It’s so ugly.) This doesn’t count the more than a hundred pieces I’ve put together with my collaborator Alan Robson, for our Thursday Tangents. Highlights of the last year included the publication of Treecat Wars, written in collaboration with David Weber, Snackreads publishing two of my short stories (“Hamlet Revisited,” and “Servant of Death” written with Fred Saberhagen), and regular updates on the progress of both Artemis Awakening and its yet untitled sequel, AA2.

The photos for these pieces (and the Thursday Tangents) are mostly taken by my husband, Jim Moore. This week’s “Kung of Kungs” is a pun indebted to the fact that in mah-jong, four of a kind is called a “kung” or “kong” or sometimes “Oh, wow! I can’t believe I just drew that tile!” I had a hand almost this good over the Christmas holidays…

Writing the Wednesday Wanderings has been a lot of work, but it’s been fun, too. I anticipate it remaining fun, since May 2014 is going to see the release of Artemis Awakening and at least one short story. There are some other surprises in the wings.

Heh, just looked out my office window. My neighbor has let his beard get really thick. Cold weather’s the reason, I bet. Ah, but I wander.

And that’s the point, if there is any. I hope you’ll continue wandering along with me. For those of you just discovering these pieces, the entire output of four years is archived on my WordPress site. They’re even more or less categorized!

Let me know if there’s anything you’d like to hear about. If you’re too shy to use the Comments, that’s okay. The e-mail address jane2@janelindskold.com will also reach me.

Now… Back to AA2. I finished a rough draft, and am now in the middle of the first of several read-throughs. I left my characters facing an unexpected confrontation. Better go see how they handle it.

January 16, 2014

Ahoy! Pirates!

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back and join in the discussion of when darkness is inspirational and when enough is just enough. Then set sail with me and Alan as we move into the troubled waters of piracy.

ALAN: I was watching some DVDs today, all legitimately purchased. Some were American and some were British. The American-produced ones all start with a (VERY LOUD) advert along the lines of “You wouldn’t steal a car, you wouldn’t steal…” and go on to point out that pirating DVDs is punishable by death, dismemberment, and life in prison (OK, I’m exaggerating a little there).

Treasure Island

JANE: I’ll admit, it’s a long time since I bought a new DVD, other than anime. I’m familiar with the written FBI warning, but I hadn’t encountered this particular approach. You’re educating me again!

That said, as someone who makes her living through intellectual properties, I’ve got to say that pirating is not a good thing.

ALAN: Oh, it definitely isn’t a good thing at all, and the British DVDs are concerned to get the same message across. But they all start with a very short and not very loud advert which simply says (and I quote directly): “By purchasing this DVD you are protecting the British film and television industry. Thank you.”

Two very different approaches which are essentially saying the same thing. I know which one I prefer. I’d much rather be thanked than threatened.

JANE: I absolutely agree. I like the British approach very much. For one thing, it’s educational. I honestly believe that if more people realized how writers – for one – are paid, they wouldn’t be as inclined to pirate. It’s viewed as one of those “victimless crimes.” The British approach gives a name to the victims.

I know a couple of people who have written for Hollywood. Would you like me to ask them if piracy hits the writer or just the Big Studio?

ALAN: Yes please – I really don’t know very much about how screenwriting works. I’ve never met anyone who does it.

JANE: Okay… I’m back. Debbie Lynn Smith, who wrote for several popular T.V. shows, and is now working on the soon-to-be released comic Gates of Midnight, said: “Both freelance and staff writers get residuals. Residuals work on a sliding scale. So the first rerun gets about half the script payment. Then each subsequent rerun gets a percentage less. I’m still receiving residuals on Murder, She Wrote, Touched By An Angel, and Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman.

“There are also foreign sales, which pay much less. DVD is even less. Streaming – I don’t know anything about as I never dealt with that.”

Then I checked with Melinda Snodgrass, who in addition to writing novels and short fiction has written both for television (Star Trek: TNG) and film. She added some details about how screenwriters are hurt by piracy: “…we don’t get money on a movie unless somebody buys that DVD… yes, piracy hurts us worse [than it does television writers], but we also get money when Netflix is streaming a film.”

ALAN: That’s interesting. I had no idea that individual writers were affected like this. I thought it was only the big, faceless, greedy companies who got hit in their bottomless corporate pockets. If I thought about it at all, I suppose I just assumed that the small creators got an upfront payment for their work. Obviously I was wrong…

JANE: Oh, they do get an upfront payment, but pirates are keeping them from getting paid for continued use of their work.

Speaking of small creators… One thing that surprises me is how few people know how print writers make money from their books. Just the other day, we had some friends over. They were talking about selling some of their books to a used bookstore. I mentioned that used bookstores – especially now that most have their stock listed on the internet – were one of the things that were killing professional writers.

ALAN: I’d never really thought of second-hand bookstores as being harmful to a writer’s income. I know you don’t receive any money from second-hand sales of your books, but I’m surprised that the impact is that large. Furniture manufacturers don’t receive any money from the sale of second-hand furniture, but they show no signs of going out of business!

JANE: Ah… But second-hand furniture sellers are not likely to sell outside of their immediate market. After all, furniture is expensive to ship. However, many second-hand booksellers now have an on-line store. That’s changed everything.

Once upon a time, second hand bookstores were very useful to both readers and writers. Readers could try a new writer or series at a discount. If they liked what they found, then they would probably turn to a seller of new books to feed their habit – after all, a used bookstore would be unlikely to have a complete run of a series or everything an author had written. Now, that’s changed. A reader can go on-line and buy from a huge variety of used bookstores, often at an astonishing discount.

A writer receives nothing from the sale of used books. Since sometimes “used” books show up almost as quickly as “new” – a result of reviewers selling sample copies – not even the newest of the new works will earn a writer income.

ALAN: But doesn’t the publisher pay you in advance for your book?

JANE: Yes. However, the term is “advance against royalties” for a reason. If enough copies sell for the writer to “earn out” the advance, more income is forthcoming. Unless you’re a super-duper bestseller, used bookstores make earning out the advance less likely than before – and, even before the Internet, earning out an advance was far from certain.

Moreover, publishers estimate the advance based on how many copies sell. If copies don’t sell (because readers are buying used), then advances go down, fewer copies are printed, and the nasty downward spiral that has forced many formerly solidly selling “midlist” writers out of business continues.

ALAN: I’d have thought libraries would be more of a worry. After all, lots and lots of people borrow library books. That’s a lot of potential customers to lose. For a long time authors got no money at all from this, but a few years ago we got something called the Public Lending Right which does give authors a tiny income from borrowed library books. Do you have anything like that?

JANE: No. American writers get nothing but the original sale for library circulations. That’s why it’s a sort of backhanded compliment when a reader comes up to a writer and says, “I love your books so much! I’ve taken all of them out of the library five times!”

Also, after a while, libraries aren’t likely to have a full set of a series or all the works by an author. This used to lead to readers seeking out the rest, a demand for reprints, and other good things for the writer. These days… Not so much.

I’m not saying I don’t use the library or used bookstores. I do. Avidly. But when there are writers who I want to see able to keep writing, then I go out and buy their books new.

There’s a creative impact, too. Can you guess what it is?

ALAN: That’s a tricky one. Let me think about it and maybe we can discuss it next time.

January 15, 2014

Darkness Has Its Place

Last week I talked about how light, escapist fiction may not be so escapist at all. Does this mean I don’t like fiction that deals with darker issues? Not in the least. I will admit that the outcome of the story will have a lot to do with whether I decide to go back to the story at some future date, but even with those books I know I’ll never read again or movies I won’t watch again, I often take away something that makes me think.

Be Brave

If light stories remind us why we live, dark stories often supply the tools that help us forge ahead when living seems to be too demanding. Frodo’s anguished determination as he slogs through Mordor. Or Tell Sackett’s lone stand against those who murdered his wife and now want him out of the way, as well. Or… You must have your stories that inspire you, even in their darkest parts.

One of the greatest compliments I ever received was in a series of e-mails from a reader who told me that my Firekeeper books had kept her going during a really bad time in her life. I assumed this was because the books had let her escape. The final e-mail I received from her showed differently. She mentioned that she was going on a trip to Europe with her mother and that, although she was afraid of going to strange places and of snakes and of several other things, she was “going to be like Firekeeper and be brave.”

Even those dark stories in which the challenges aren’t mighty and heroic can be wonderfully heartening. When I was in high school, I read Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. This is not a light story, but it has remained with me all my life, serving as a talisman about trying to find victory even when surrounded by what looks like defeat.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the tale, it recounts one day spent by Alexander Denisovich Shukhov, a prisoner the Stalin-era Siberian labor camps. The final paragraphs, in which Shukhov seeks value where most would concentrate on the horrible conditions in which he lives (including the fact that he’s imprisoned for no justifiable reason at all), are worth quoting. Here they are in Ralph Parker’s translation:

“Shukhov went to sleep fully content. He’d had many strokes of luck that day: they hadn’t put him in the cells; they hadn’t sent his squad to the settlement; he’d swiped a bowl of kasha at dinner; the squad leader had fixed the rates well; he’d built a wall and enjoyed doing it; he’d smuggled that bit of hacksaw blade through; he’d earned a favor from Tsezar that evening; he’d bought that tobacco. And he hadn’t fallen ill. He’d got over it.

“A day without a dark cloud. An almost happy day.

“There were three thousand, six hundred, and fifty-three days like that in his stretch. From the first clang of the rail to the last clang of the rail.

“Three thousand, six hundred, fifty-three days.

“The extra three days were for leap years.”

Nor did I stop with this fictional account with this very qualified “happy” ending. I also read Solzehnitsyn’s very long Gulag Archipelago. Powerful stuff. Horrible stuff. Frightening stuff. Inspiring stuff.

There are other dark stories that have nothing to do with overt violence, rape, and mayhem. A tale like Citizen Kane is about forgetting what you really care about – in that, it’s very depressing. It’s also uplifting, if you choose to take from it a reminder of what you do care about.

Going back to Winston Churchill for a moment. (For those of you who didn’t join us last week; Churchill’s life is what got me started on this train of thought.) His life wasn’t a novel. Readers bring expectations to novels – and believe me, I’m still getting angry fan mail from readers who feel I violated their expectations as to who Firekeeper should have settled down with!

The boy Winston didn’t know as he struggled with his erratic academic career (at one point, his father despaired of him as sub-intelligent) that he would be remembered as a brilliant writer and historian. The young Winston, who broke with the Conservatives on matters of principle, didn’t know that twenty years later, he’d be welcomed back. The political “exile” didn’t know that exile would end. As far as Winston knew, he – like his father – would find that standing up for his principles would mean his political career was over.

One of the things that sustained Winston Churchill thorough all of this were stories: stories about idealism and heroism, stories about friendship, stories about valor. He was a historian, and so knew all too well how vicious humans could be to other humans. However, he chose his models and tried to live up to them – even when he was aware of how often he failed.

Now, I’ll admit, I don’t particularly like reading stories about nasty people doing even nastier things to other people, but I can find value in them. When I find myself getting upset, I look at why I’m so offended by the content. Often, in the process, I learn what I value. That’s worth something in itself.

When I was in college, Stephen R. Donaldson’s “Chronicles of Thomas Covenant” were on everyone’s “must read” list. As the series unfolded, I noticed something interesting. Darkness, grittiness, and edgy content weren’t enough to sustain the readership. As Covenant refused to learn and grow, the series lost readers… It never recovered.

In fact, I suspect that most readers of “dark” fiction are waiting for the light at the end of the tunnel. I’m willing to be told I’m wrong. I’d be curious as to your response.

January 9, 2014

TT: Tipping — The Really Confusing Parts

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back one and join in as we take a look at why “light” fiction is not necessarily either fluffy or without value. Then come and help me explain to Alan the greater complexities of tipping.

JANE: Well, Alan, last time I attempted to explain tipping to you and apparently only confused you. I should warn you, this part isn’t going to get any better. Sure you want me to go on?

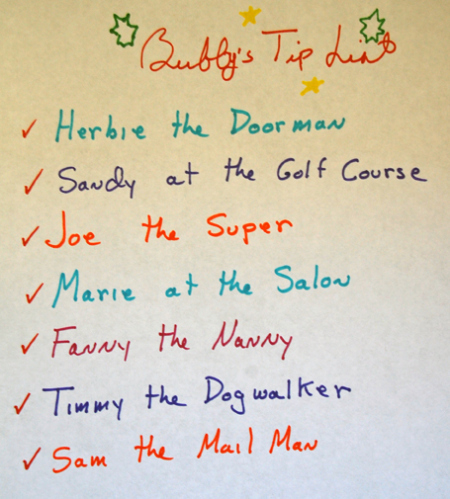

Buffy’s Christmas Tip List

ALAN: Yes please. Explain it to me as you would if I was only five years old…

JANE: Ah, the way you’ve explained some computer weirdness to me! Got it.

Here we go… Other places a traveler in the U.S. would encounter routinely expected tips are taxi cabs and hotels. Now, this is where my resistance level starts going up. If a cabbie handles heavy luggage or something, I don’t mind giving a bonus, but why should I tip for the cabbie simply sitting behind the wheel of a car and driving me from point A to point B? Especially since these days, with GPS, they don’t even need to know the complexities of the city.

ALAN: Exactly. Why should you? Here I pay what’s on the meter, no more and no less. And the taxi drivers are perfectly happy with that.

JANE: Makes sense to me. However, it’s not only cabbies who expect to be compensated for just doing their job.

In hotels, especially the more expensive ones, the number of people with their hands out is astonishing. If someone moves your luggage for you, he expects a tip. If someone helps make a restaurant reservation, she expects a tip. If someone brings a room service meal to your room (a meal which is already highly overpriced), they expect a tip. If they park your car for you (even if that’s hotel policy), ditto. When they retrieve it, ditto, ditto.

ALAN: Again, that simply doesn’t happen here. No hotel staff ever expect to be given a tip. They are always pleased and appreciative if you do give them one, but it’s never expected and no pressure is brought to bear.

JANE: It’s getting worse. There’s increasing pressure to leave money for whoever has “done” the room – even though these days the service is much decreased because linens and towels are not changed daily, in order to save water and energy. (A trend I approve of, by the by.)

Again, unless I’m asking for something out of the ordinary, I balk. I particularly balk at leaving an envelope of cash in my room for some member of the cleaning staff since I have no assurance that it will go to the person who has been “taking care” of me.

ALAN: It would never even occur to me to leave an envelope of cash. And neither would it occur to me to tip the cleaning staff.

Since my habit is never to tip anybody for anything, how would I get on if I came to America? Would I get into any trouble? Would the people I didn’t tip take their revenge on me?

JANE: I think your accent would be your protection. Or maybe not. I checked the web and several sites have detailed lists of what sort of tipping is expected in a wide variety of nations. Ignorance may no longer be bliss.

Frankly, and I’m bracing myself to be told why I’m wrong by people who know more, I feel that tipping in the U.S. has increasingly taken on the aura of a bribe. There are all sorts of stories – I hope most are urban legends – about wait staff spitting in the meals of habitually bad tippers, of luggage handlers deliberately scratching or denting bags, and the like. This reminds me of what you said about your father leaving Christmas boxes, not because he was grateful – which to me is what the term “gratuity” should mean – but to avoid the potential of malicious mischief.

ALAN: That’s verging on the nasty, and it sounds rather like being required to pay protection money to the local mob!

JANE: I like the comparison. There’s an even worse aspect, a situation where, frankly, the “tip” cannot be taken as anything other than a bribe. That’s when special services are provided to those who know how much and to whom to give extra money.

ALAN: Sorry – I’m not sure what you mean by that. Can you give an example?

JANE: Sure! Some friends of Jim’s and mine went to a city famous for its nightlife. There they met up with a friend who was a resident. My friends were very impressed that their contact got them into something – I forget if it was a show or a trendy restaurant – that was ostensibly full because he “knew how things worked” and handed wads of money to the right people.

I wasn’t impressed. I thought it sounded very seamy.

ALAN: And it has aspects of showing off again – look at me, I’m important, I can do things that normal people can’t do. It makes me cringe.

JANE: Yeah. Me, too.

Let’s see… If you and Robin were traveling in the U.S., you wouldn’t need to worry about many of the other places where tipping is increasingly routine. Still, I might as well mention them, just to be complete. Golf courses, casinos, and beauty salons all expect tips. I have no idea what one would tip for at a golf course, since I don’t play. Same with casinos. As for beauty salons, I only tip if I’m really happy with service. However, I can see why someone who wants to establish a relationship with a particular stylist might reward exceptional artistry.

ALAN: Robin and I are already beautiful; we have no need for salons. We don’t play golf because that’s exercise and we’re geeks. Geeks don’t do exercise. And we’ve both studied mathematics to advanced enough levels that we are very familiar with the odds involved in gambling. So we don’t go to casinos either. Consequently I think we’d be quite safe…

JANE: That’s a relief!

We got off on this topic because of the subject of Christmas Boxes, so it’s only fair I fill out how the custom works here. Just like in your father’s day, the letter carrier is eligible for either a gratuity or a small gift. Jim and I really like our regular letter carrier, Gilbert. He routinely carries packages up to the door and keeps an eye on people along his route. One day he rang my bell and asked if I knew if the elderly lady next door was all right because she hadn’t been picking up her mail and didn’t answer her door. (Turns out she was traveling and had forgotten to have her mail stopped.)

However, I don’t give Gilbert a tip at Christmas. Instead I fill out cards for the post office making sure they know he’s doing a great job. Also, if I happen to catch him, I’ll give him homemade cookies.

ALAN: Oh that’s nice. I hope his supervisors take note of what you say.

JANE: I do, too. Gilbert is a gem.

A lot of the other “service personnel” who are “traditionally” tipped don’t really apply to my life. I don’t have a building superintendent, a doorman, or someone who delivers a newspaper. I don’t have a relationship with a hair stylist (who is apparently supposed to get an extra tip this time of year). I don’t have someone who walks my dog (probably because I don’t have a dog), cares for or teaches my children (ditto).

ALAN: Half the fun of having a dog is walking it yourself. And you wouldn’t tip yourself. So why should you tip someone else who is getting the fun? Fun is its own reward.

JANE: I agree. I used to walk my neighbor’s dog just for the fun of it. We both enjoyed it immensely.

As I look at this list, one thing that strikes me is how it reflects two things: affluence (living in a building with a doorman) and a relatively urban existence. Nor am I certain that these holiday tips are uniformly observed throughout the U.S. When I lived in New York a usual feature of grocery stores was a little container where you were supposed to toss a tip for the person who was bagging groceries.

When I moved to Virginia and, later, to New Mexico, these little containers were not in evidence and no one has ever seemed to expect me to tip them for bagging my groceries. It’s possible that many of the tipping customs I’ve mentioned are regional. That’s one part of this discussion where our readers can help us out.

ALAN: Well, thanks for clearing all that up. I think I understand what’s expected of me now. Mind you, I really don’t think I’d be any good at it – I’d resent the expectation, and I’d always be afraid that I was doing it wrong and perhaps over- or under-tipping. Oh! The embarrassment!

JANE: I know how you feel…

ALAN: On another tangent, I bought a couple of DVDs recently and stumbled across an enormous cultural difference between the ways that the Americans and the British approach the problem of piracy. Can we chat about that next time?

JANE: I’d like that. It sounds fascinating.

January 8, 2014

Light, Not Necessarily Fluffy

Recently, I’ve been listening to audio books about Winston Churchill. Oddly enough, that’s started me thinking about fiction, light and dark, and the role both play in our lives.

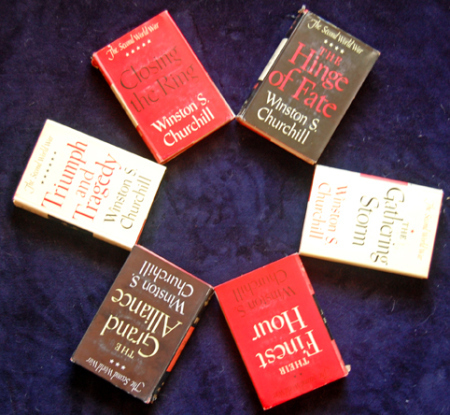

A Few Churchill Titles

I’d been interested in Churchill in an abstract fashion since I was a kid. Every second house seemed to have a set of his WWII chronicles, bound in red and white and black, their stirring titles (Triumph and Tragedy, The Gathering Storm) sounding more like novels than history. Despite this, I didn’t know much about Churchill other than the pictures of the big man with the cigar, looking very tired. I’d also heard a few stirring quotations and a few caustic jokes credited to him. The one biography I read felt like one of those tiny samples they give you in the deli when you want taste their potato salad.

When I decided to amend this, the two books our library had as MP3 audio downloads were not about the Winston Churchill of those pictures and quotes at all. Martin Gilbert’s Churchill: A Life, Part One focused on Churchill’s early life, from his boyhood, through 1918. The next one, William Manchester’s The Last Lion Alone: Winston Spenser Churchill, 1932-1940, focused on Churchill’s “years of exile.” Although Churchill had risen to First Lord of the Admiralty during WWI and remained in Parliament thereafter, for many years he was far from a mover and shaker. Most of his contemporaries thought he was washed up. His income came from the phenomenal amount of non-fiction he wrote – and even that wasn’t enough to sustain his lifestyle. When the Nazi threat became something that couldn’t be ignored and changed Churchill’s fortunes, he actually had his country house on the market.

For someone like me who knew Winston Churchill as a great and influential politician, perhaps one of the last who merited the title “statesman,” it was a shock to learn that he was a 65 year-old “has been” when he was at last, reluctantly, given a Cabinet seat.

But you can read about Churchill elsewhere…

Even as I was listening to these books (the Manchester one alone ran 35 hours), I found myself thinking how differently I would have reacted if I hadn’t known that Churchill would be vindicated, that his faith that he would someday be able to serve his country in her hour of need (a hope expressed in numerous letters) would come to pass. Even knowing – maybe especially knowing – the larger historical context, I found myself frustrated. I knew the story would have a “happy ending,” but getting there was a real trial.

And that got me thinking about the expectations we bring to fiction – and about different purposes different types of fiction serve in helping us to deal with our lives. Even light fiction or adventure fiction serves a very good, very solid purpose – other than the “escape” that most readers of such sheepishly admit they are longing for when they curl up with a much re-read favorite or a book they know isn’t going to end with death, doom, and destruction. “Light” in this context doesn’t mean without thoughtfulness or merit, any more than a Shakespearean comedy was a laugh a minute.

Recently, a friend mentioned that because his job has been very stressful and demanding, he’d been reading a considerable amount of Georgette Heyer. Heyer specialized in historical romance novels, usually (although not always) set during the English Regency. In them, love will conquer all sorts of obstacles: class differences (or perceived differences), income gaps, misunderstandings of heroic proportions, and more. No matter how complicated the plot, by the end, the right guy and right girl will have found their way to love – and the promise of a future that will allow them both to flourish.

Trite? No. I wouldn’t say that. We all have learned that there are times that love won’t conquer all. Is there anything wrong with remembering that you really love someone and so maybe you need to work a bit harder? Is there anything wrong with love being an inspiration to better things? I don’t think so.

I’m not much of a fan of romance novels, although I like stories where romance is an element. However, I’m drawn to stories where love in its many forms becomes a driving force. I like “buddy” stories. I like action or war stories, where not letting down the side drives the characters beyond what they thought they could achieve. I found Dumas’ Count of Monte Cristo incredibly compelling because it’s a story about hatred and revenge in which the main character – who has every reason to hate with every fiber of his being – also learns to conquer that hatred.

Light reading? Escapism? Call it that if you will. I think I’d call it healing, a reminder that although life has ground you down, the good things do exist, even if at that moment they seem out of your reach. After Roger died, I read an enormous amount of Terry Pratchett. (Seriously, I think I read everything Pratchett had published to that point, courtesy, largely, of Jan and Steve Stirling, who handed over boxes containing their entire collection; I’ve now bought my own copies.)

It wasn’t Pratchett’s humor that lifted my heart. It was that his stories reminded me of why we love, even though love can hurt you worse than anything. When my dad, my grandfather, and several beloved pets all died within a few months, again, it was to “light” fiction I turned for the building blocks of healing.

What about dark fiction? Oh… I read that, too. But I’ve wandered on enough for one day. I have a novel to finish. I’ll take a look at the dark side next week!