Jane Lindskold's Blog, page 149

June 6, 2013

TT: Tangenting for Two Years

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back one to where I explore the peculiar convolutions that me led to starting my current novel. Then come back here and

A Toast to Two Years!

join Alan and me as we celebrate two years of nattering on about anything and everything.

ALAN: Well, Jane, we’ve been exploring tangents for two years now. I don’t know about you, but I’m still having lots of fun.

JANE: Oh, I agree. Every time we think we’ve run out of things to talk about, something new comes up. I’ve gotten to the point that I’d seriously miss these discussions.

ALAN: One of the more surreal aspects of writing these things is that, although you and I haven’t met in person for eighteen years or so, we still find it so very easy to talk to each other. Scarcely a day goes by without an exchange of emails.

JANE: I agree about this relationship being rather surreal. I was saying to Jim the other day that I wouldn’t know the sound of your voice and, since you’re as camera shy as I am, I could probably walk past you at a convention without knowing you. However, our chats ‑ both those that become Tangents and those on other matters ‑ have become pulse points in my day.

ALAN: I’m the one who keeps winning the George R. R. Martin look‑alike competition. You’re the one with the wolf and the ecstatic expression. Easy!

JANE: I still see problems. I know George fairly well, so I probably wouldn’t mistake you for him… And I never have a wolf with me at conventions. I fear we’d be ships passing in the night.

Another oddity is that, although we exchange e‑mails on a nearly daily basis, those days are often not the same day. If I’m writing you in the afternoon, especially, the 18 hour time difference means that even when your reply comes within moments, you’re writing me on the next day. I feel as if I’m corresponding with the future.

ALAN: Ah! But that gives me a huge advantage. Because it’s always tomorrow here, I know what happens! Now I have these lottery results that you might be interested in…

JANE: If you can figure out the results for the lottery here, I’m all for it. I’d even split the take with you and Robin!

I will admit, although you’ve been a very good influence on me overall, you have played havoc with my already challenged spelling. I keep fighting an urge to add “u” to words like “humor” and “favor.” My computer’s spell check is constantly trying to get me to Americanize your spelling, but I refuse.

Paul Dellinger, who proofs for us, is very patient in preserving the differences in our spelling and punctuation, something I like because it provides a tacit reminder of our different cultures.

ALAN: Well, since you don’t need to use ‘u’ very often, would you care to send me some? You must have a lot to spare, and I’m starting to run out.

On a more serious note, one of the things I’ve really appreciated about what we’ve been doing is the insight you’ve given me about the way your “foreign” society works. We have a lot of similarities, as you might expect because of our shared European roots, but we also have a lot of differences as well. Pinning these down has been truly fascinating.

JANE: Yes! That’s something I’ve enjoyed as well. Although often our topics have been light ‑ two years ago, we started with names for items of clothing ‑ we’ve managed to tackle some serious subjects as well: voting practices, medical care, and education systems all spring to mind immediately.

ALAN: And naked ladies. Don’t forget the naked ladies!

Of course we’ve also spoken a lot about books; our mutual obsession. That’s been useful as well as fun in that you’ve introduced me to writers who I might not otherwise have stumbled upon. I read The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett so I could discuss the Yorkshire aspects of it with you. I enjoyed it a lot more than I expected to. Excellent book! You also introduced me to Jacqueline Winspear’s “Maisie Dobbs” novels, which I absolutely loved.

JANE: The same for me… I spent a happy week or so immersed in the complexities of James Blish’s Cities in Flight based on your enthusiasm. And I read Jack Vance’s Space Opera. Most recently, I read Harry Harrison’s The Technicolor Time Machine, because you mentioned it.

ALAN: Technicolor ‑ amusingly the British edition retained the American spelling on the cover. But the audio book, which was produced by an American company, used the British spelling – “technicolour.” How weird is that?

JANE: Oh, it’s not weird at all. They probably just got a good deal on the letter “u.”

ALAN: A question that I know both of us have been asked is whether or not these tangents are real discussions. And of course the answer is yes. They derive quite naturally from email conversations that we have. We certainly edit and polish and rearrange the bits and pieces, but even as we are writing them, the early drafts are full of gaps where the other person can make a contribution. And sometimes that contribution sends the conversation off in all kinds of unexpected directions. Just like in real life.

JANE: Yes. Over time, I think we’ve found that the subsequent piece stays most spontaneous if we trade the evolving essay back and forth repeatedly. This also tends to lead to new topics…

In fact, we often have so much to say on a given topic that we need to sub‑divide, which is why one topic may stretch out over several weeks.

Really, it’s been a tremendous amount of fun.

In fact, too much fun… I’ve turned the revised Artemis Awakening in to my editor and I really should be working on the sequel. So, until next time…

June 5, 2013

And We’re Off!

This past week I started the sequel to Artemis Awakening. This is a big deal, an event to be celebrated with ice cream, preferably chocolate.

Awakened by Eyes Like Leaves

At least for me, starting a novel never seems to get any easier. This is true even if – as with this book – I am already acquainted with many of the main characters, have some idea of the setting, and even have a sense of what some of the major plot elements will be. Maybe even because of all these things, there’s this dreadful point where the characters simply aren’t talking to me. (See “Advice from Agatha” WW 1-26-11 for a bit more on this particular stage in writing a novel.)

This novel – untitled as of yet, so let’s call it AA2 – was particularly cursed by circumstances. Literally the day after I got the re-write of Artemis Awakening done and turned in to Claire Eddy at Tor and was walking out the door to go the airport to pick up my mom, who was coming for a Mother’s Day weekend visit, my phone rang. It was an ebullient David Weber, wanting to tell me that he’d finished debugging a timeline problem in our collaborative novel Treecat Wars (don’t ask; it’s fixed; we both love it) and he’d e-mailed me the manuscript and would I re-read it right away…

I told him I couldn’t right away because I was going to visit with my mom, but I’d get to it first thing on Monday. Except, when Monday came, I couldn’t, because my new computer was acting weird and had to be unhooked and sent back to the shop. (They fixed it.) So Weber expressed me a hard copy of the manuscript and I re-read it. Then (figuring out all the new programs on my newly returned computer), I sent him a long letter debugging the bugs that had crept in through the seams. (He stepped on them; they’re dead.)

But, by then, a couple of weeks had gone by, weeks that I’d spent in another universe with other people. That didn’t exactly make it easier to “hear” Adara and Griffin and Terrell and Sand Shadow, nor to “see” their world and their particular situation. I kept trying, but nothing was coming forth. Alan and I wrote back and forth a lot about other people’s stories, so I wasn’t exactly unproductive, but AA2 still was more theoretical than a reality.

As I’ve mentioned a few times, I’m a subconscious plotter. I don’t outline. If I try, all that happens is that inspiration rolls over and dies, like a butterfly with a pin through its heart. This can be frustrating but, after 22 published novels and 60 some short stories, I’ve learned not to fight it.

What gave me my breakthrough?

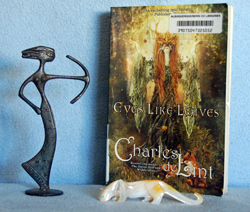

Well, the novel I’m currently reading is Eyes Like Leaves, by Charles de Lint. It’s an odd book because, although it was written sometime in 1980, it was not published until 2012. (If you want to know why, go read Charles’ excellent introduction to the novel. It’s worth it, especially as a window into the conflicting and complementary forces of market and art.) Charles says he did not heavily revise that long-ago manuscript, but he did polish. His biggest change was rewriting the opening chapter. He included the original version as an “extra” at the end.

It was in de Lint’s short introduction to this “extra” that I found the key to open my mental door.

I quote: “I wasn’t enjoying the first chapter. It just seemed to go on and on with back story, when all I wanted was for the book to start. Then I remembered a piece of advice from mystery writer Lawrence Block. He said that one should go ahead and write one’s novel, but when you’re done, just throw the first chapter away. Too many newer writers (such as I was when I wrote this book) feel they have to cram all this unnecessary information into the beginning pages of the book instead of just getting on with things.”

When I read this, I found myself getting all excited. Remember how I said that maybe it was because I had so many ideas about AA2 and where it was going that I was having trouble starting? Maybe I was trying to put too much in? Certainly, because I’d spent much of the last couple of months mostly in editorial mode (both with Artemis Awakening and Treecat Wars), rather than in creative mode, I was thinking in a very pragmatic fashion. I decided that, instead of thinking about foundations, I should go to where the story started. Almost as soon as I made that decision, I heard my characters talking.

“Forbidden, you say? That sounds promising.”

The conversation tumbled on, almost faster than I could scribble. The opening may not be precisely like this when the book is done, but that doesn’t matter. I’m there… The story has started. We’re on our way to places forbidden…

So, thank you, Charles, and thank you, Lawrence Block. And thank you, Griffin and Terrell and Adara. I can’t wait to see where we’re going next.

May 30, 2013

TT: Roger Zelazny — Master of Odd Twists

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back and join me as I muse over why magical items are suddenly so unpopular with some readers of Fantasy. Then join me and Alan as we continue our discussion of one of our favorite writers.

Zelazny’s Mythic Universes

JANE: Last time we were just getting into Roger Zelazny and his particular ‑ or perhaps I should say “peculiar” ‑ take on using mythological and historical material in his fiction. I know we both had other books we wanted to touch on. You go first!

ALAN: Roger continued to explore mythological themes in two novels called Isle of the Dead and To Die in Italbar. Both books featured a character called Francis Sandow. However this time Roger didn’t base the stories on any known mythology, he made everything up from scratch.

Sandow himself is an avatar of the god Shimbo of Darktree, Shrugger of Thunders. Isn’t that a wonderful phrase?

JANE: It is indeed…

ALAN: The books play with similar ideas to those in Lord of Light (men as gods) but I enjoyed them a lot more, probably because I didn’t have to struggle with references to mythologies I only half remembered. When the writer invents his own mythologies, every reader starts from the same level of ignorance and the book succeeds or fails purely on its own merits. As I recall (correct me if I’m wrong), these novels were not a great critical success ‑ but I always enjoyed them a lot and I felt that the interweaving of an invented mythology with the story line worked brilliantly.

JANE: I don’t recall how great a critical success the novels were (I was about five when Isle of the Dead was published). However, I liked them a lot. One difference between the Sandow novels and Lord of Light is the manner in which humans can become gods. In Lord of Light, the means may or may not be merely technological. In the Sandow stories, the becoming is far more mystic.

Another novel where Roger drew both on traditional mythology ‑ in this case, Egyptian and Greek, as well as creating his own – was the very strange novel, Creatures of Light and Darkness. I remember being pretty confused by it the first time I read it, but I found it merited a re‑reading. Now it’s one of my favorites of Roger’s works.

ALAN: What a peculiar book it is. Lighthearted and grim at one and the same time. Osiris captures a deadly enemy and weaves his nervous system into the fabric of a rug. Every so often Osiris entertains himself by jumping up and down on the rug and listening to the screams of pain that the rug broadcasts through loudspeakers. I find that simultaneously hilarious, sick, wonderfully imaginative and quite twisted.

Come to think of it, you could describe the whole book with those words. It continues Roger’s fascination with the theme of men who might be gods, but this time it paints the picture with Egyptian and Greek mythologies. It is set in the far future and so technology plays a large part in it. In some ways it feels a bit like a proto‑cyberpunk novel. The style is also very odd. It’s written in the present tense and it’s got poetry and a playscript in it. Given that it experiments so much with style, it could even be thought of as a New Wave novel!

JANE: It also has one of the oddest sex into romance plots in any of Roger’s novels. Actually, I’d go so far as to say in any novel at all.

Roger didn’t write Creatures of Light and Darkness with any plans for publication, so, I suppose, in some ways it could be looked upon as the quintessential Zelazny novel. If I remember correctly, he mentioned it to Samuel R. Delany ‑ one of the brightest lights of the American New Wave ‑ who convinced him to show it to an editor. So your feeling that it belongs to that particular “tradition” seems right on the spot to me.

ALAN: Gosh ‑ I never knew that. I was just commenting on the feeling I got from the text.

JANE: You obviously have a good sense for literary forms…

Roger’s most popular works ‑ the ten volume Chronicles of Amber ‑ were also heavily indebted to myth and history. Corwin, the narrator of the first five books, has lived for centuries, been a soldier in many wars, and left traces of himself in our myths and legends. So, too, have his numerous siblings.

Roger kept the references light, but I always felt they added depth to what otherwise might have been just another sword and sorcery adventure. In fact, I missed these brush strokes of myth and history in the latter five books, where the narrator (for all that his name is Merlin) is much younger and the stories delve more deeply into the back history of the courts of both Amber and Chaos.

ALAN: Oh, I agree completely. The stories about Merlin always felt thin and lacking in depth to me. Merlin is a callow youth in comparison to his father and the stories were slight. I missed Corwin’s vast experience and his cynicism.

What do you think of A Night in the Lonesome October? It’s one of my favourites of Roger’s books. Not only is it very, very funny but it also uses mythology in a way that few other writers have used it. Mythologies are not static. Every age adds its own stories to the myths and legends. There are layers upon layers.

JANE: I agree… While one definition of “mythology” is firmly rooted in religions, there is another that embraces the themes and stories that define us as a culture.

ALAN: Our modern myths seem to involve Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper et. al. (who may themselves be avatars of older beings). There are also many nods to the supernatural in the telling of our tales (the stories of the Angels of Mons from the First World War spring to mind, along perhaps with more mundane entities such as vampires and werewolves). Of course this kind of thinking leads naturally to the current glut of Buffy/Twilight urban fantasy rubbish. But in A Night in the Lonesome October, Roger treated the ideas in a much more mature fashion and the result is quite delightful.

JANE: I loved A Night in the Lonesome October. However, I am rather biased… After Roger was done with the book and re‑reading it, he told me that he realized he’d modeled the cat, Graymalk, somewhat after me, especially in the banter with Snuff, the dog. I, of course, was thrilled…

A Night in the Lonesome October was also one of the few of Roger’s books that I had the chance to “watch” being written from start to finish. He’d had the idea for the book for many years, but he’d had his heart set on Gahan Wilson illustrating it. Eventually, he decided to just go ahead and write it in the hope that Gahan Wilson could find time to do his part. (Which he did.) I’m so glad Roger did so. His joy in the project was a delight.

By the way, the book is a homage to many of the writers whose work Roger read when he was young. The dedication provides a listing, just in case you’re interested. I think he touched on most of the major modern “mythologies” in that one ‑ with the exception of Tarzan, and Tarzan got his nod in Donnerjack.

ALAN: But of course Roger had other literary interests as well. Perhaps we could look at some of those next time?

JANE: I’d enjoy that quite a bit

May 29, 2013

Musing on Magical Items

So, how much is too much when it comes to magical items?

Swords, Scarabs, Dragons, and Rings

Over the last few years, I’ve encountered a real resistance among some readers, writers, and editors of Fantasy fiction to novels that include magical swords, amulets, rings, and the like. These works are spoken of with a sneer and are much less likely to get attention when the time comes for award nominations. Oddly, this resistance includes “fan” awards, even when the books in question are topping the bestseller lists.

As for dragons… I’ve been on panels where panelists have proudly and loudly announced that their forthcoming Fantasy novel is a “dragon-free” zone.

But I wander off my point. (But then, these are Wanderings, right?)

So, where did this resistance to magical items come from? Why has the idea arisen that the inclusion of such makes a piece less magical?

Certainly magical items belong to Fantasy from its earliest roots in mythology. Many of the Norse gods possessed magical items. Some had more than one. Thor, for example, not only had his hammer Mjolnir, but also an iron mitten that let him catch the hammer when he threw it at a target. (The hammer apparently had boomerang properties). Thor also had a magical belt that increased his strength two-fold. Oh, yeah, let’s not forget his war cart, which was drawn by billy-goats and flew through the air.

Greek myths also contain magical items. These are not limited to those like the Chariot of the Sun, which can be “excused” as a pseudo-scientific explanation for natural phenomena. Nor are they restricted to divinities. Mortal heroes often bear magical weapons. Perseus is equipped with not only Athena’s mirror-bright shield, but with Hermes’ own magical sword. As if this is not enough, the nymphs of the north loan him magical sandals that let him fly, a cap that makes him invisible, and a bag that swells to contain whatever is put into it,( so he’ll have a neat and tidy place to store Medusa’s head).

I could go on and on… There are magical harps of the British Isles. The amulets and charms of the Egyptians. The magical armor and weapons with which almost every culture equips its gods and heroes. Sometimes, the ability to use these items is taken as proof that the bearer is, in fact, worthy to be a hero.

So, again I ask, why are such so often scorned when they appear in Fantasy fiction? Why does giving the protagonist a magical sword immediately slide the tale down the literary scale?

Over the last week or so, inspired by Alan and my discussion of Fantasy fiction that draws from Welsh sources (TT 5-02-13), I’ve been re-reading Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles. (The first book is The Book of Three, if you’re interested in trying them.) Here we have a magical sword, a glowing sphere, and a magical harp… There are magical tomes, potions and lotions, and a very potent amulet. Indeed, the only item in the magical bag of tricks that is missing is a ring.

Despite this, I have heard the books praised by the hardest of the hard-headed as really good Fantasy fiction. Nor do I think that the Prydain Chronicles “get away” with including magical items because they are “children’s books.” In fact, as an avid reader of YA fiction, lately I’ve encountered more – not less – aversion to novels that include magical items. Yes. Even though Harry Potter included a host of such, the resistance is there.

I could go on and on, but I’ll pause and give you a chance to get a word in. Do you have a particular favorite among the magical items of Fantasy fiction? When do you think enough is enough? Does the inclusion of magical items – especially those classic swords and rings and suchlike – cause you to hesitate to even give the story a try?

May 23, 2013

TT: The Role of the Reader’s Knowledge

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back and take a look at Puye Cliffs. Then come on back and join Alan and me as we take a look at how the reader’s knowledge can shape the reading experience. Along the way, we focus in on a writer whose works we both admire greatly – Roger Zelazny.

Eye of Cat

JANE: Last time, Alan, you mentioned how – although you like Fantasy and Science Fiction that uses myth, history, or both as a foundation - the further the material moves from sources with which you are also familiar, the less easy you find it to relate to.

ALAN: That’s right. And the example I used to point it out was Roger Zelazny’s novel Eye of Cat which was full of references to Navajo culture.

JANE: I was already somewhat familiar with Navajo material when I read Eye of Cat. Nope. It wasn’t because I was such a great scholar. It was because I liked the mystery novels of Tony Hillerman, which are largely set on a Navajo reservation and have many Navajo characters. (Hillerman, by the by, shares the dedication of Eye of Cat with his two most famous fictional characters, Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee.)

However, for reasons I now forget, when I taught a science fiction seminar back when I was still at Lynchburg College, I chose Eye of Cat as an assignment. My students were as uncomfortable with the material as you were. Now that I think about it, it might not have been my best choice. Not only was the material indebted to Navajo myth and legend, one of the main characters is a highly unreliable shapeshifter. And part of the novel is written in verse…

I’ve found that once readers are overwhelmed, they miss things that ordinarily they would catch. Roger was notorious for the jokes – some sly, some overt – that he would slip into an otherwise serious novel. Therefore, you’d think more of his readers would have thought carefully about a certain passage in Eye of Cat. Not one of my students did – not until I had them work it out in class.

The passage in question comes at the end of the novel: “Moving nearer, he saw the pictograph Singer himself had drawn on the wall with his own blood. It was a large circle, containing a pair of dots, side by side, about a third of the way down its diameter. Lower, beneath these, was an upward-curving arc.”

Did you get it?

ALAN: It’s a smiley face! How delightful!

JANE: Yep! A smiley face… To me (putting on my English professor hat), this pictograph says a lot about how Billy felt at this key point… But most people will miss the detail. Therefore the ending of the novel will be oblique

ALAN: It’s been many years since I read the novel, but I don’t recall spotting that at the time. I was so lost and confused by that stage of the book that I think pretty much everything was passing me by.

JANE: Yeah… I don’t think most people did. Roger out-clevered himself.

As an aside, I don’t know if it’s available anywhere, but Roger read Eye of Cat as an audio book. His readings were always wonderful, but this book especially loaned itself to being read aloud. It was released in a slightly abridged form (which might contribute to confusion) but, even so, it’s wonderful. Roger also was recorded reading A Night in the Lonesome October. People always talked about Roger being shy. In some ways he was, but he also loved to perform.

ALAN: Roger had a wonderful voice and he used it to great effect when reading out loud. When you and he were here in New Zealand as convention guests, he read some extracts from A Night in the Lonesome October to us. He was just brilliant; he carried his audience with him all the way and afterwards I told him how much I’d enjoyed it and how well he’d done the reading. He smiled happily. What I didn’t tell him (perhaps I should have) was that I’ve done a lot of reading to audiences – I’ve won prizes for it. So I know what’s involved and how hard it is to do it well. Roger did it very well indeed. I’d love copies of those recordings, if they still exist.

JANE: How wonderful that you’ve won awards for reading aloud! That’s neat.

So, how about Zelazny’s Lord of Light? He used a lot of material from Hindu and Buddhist sources. How easily did you relate to that one?

ALAN: Lord of Light was also hard to relate to in some ways, but it wasn’t as difficult as Eye of Cat. I did know a little bit about the mythologies (though not as much as I should have), so to that extent the book was approachable. And there’s also something irresistibly attractive about a god with the very prosaic name Sam. Little touches like that kept me reading and enjoying the book.

And of course the book contains one of the best jokes Roger ever made. The Shan of Irabek suffers an unexpected grand mal seizure:

“Then the fit hit the Shan.”

I read that sentence with utter chortling delight. It truly made my day.

JANE: I remember the first time I read that passage… I just sat there staring at the page, unable to believe it. Then I started laughing. The only other time I’ve reacted in that fashion was to the opening verse of “C’est Moi” from the musical Camelot.

Interestingly, the readership seems split on that scene in Lord of Light. Some people love it, while some think it is completely out of place in an otherwise “serious” novel.

ALAN: Nothing’s so serious that you can’t have a little bit of fun with it.

JANE: I’m with you on that! I think without being too bold, I can say that Roger would have agreed with us both.

Now, duty calls, deadlines beckon. However, I’d like to continue discussing Roger’s work next time.

ALAN: Yes – Roger was such a versatile writer. There’s a lot more to explore.

May 22, 2013

Puye Cliffs

Ever wonder what it might be like to live in a cave? Last weekend, when Jim and I drove out to Puye Cliffs to participate in their Open House, I had a chance to examine that question up close and personal.

Doorways in the Rock

As so often on such expeditions, our friend Michael Wester was with us. During the nearly two hour drive north from Albuquerque, our conversation ranged from the prehistoric peoples who had occupied the land over which we traveled, to the very modern issues of computer technology, to the role of entropy in the choices we make. The weather noticeably cooled as we moved north. The pale green of the cottonwoods showed as a pale ribbon of green that meandered through the darker greens of the pinyon and juniper, contrasting against the golden brown of rock and sand.

When we arrived at Puye (pronounced “poo-yay”), the cliffs dominated the landscape, their color shifting from grey-brown to almost golden, depending on the light. Since the day was partly cloudy, we had ample opportunity to enjoy the shifting hues and enjoy the crisp mid-morning air.

For the first hour or so of our visit, we observed the cliffs from below. The small Puye Cliffs museum and gift shop occupies a former Harvey House, built in the 1930′s to cater to tourists who found the newly expanding railroad a wonderful way to explore the Wild West. According to the brochure, “puye” means “place where the rabbits gather,” a name that provides at least one indication as to why the area was originally settled.

As part of the Open House, Jim was giving a flintknapping demonstration. As he used hammer stones and pieces of deer antler to break off flakes that might eventually be turned into arrowheads, I helped by explaining what he was doing to groups which included both residents of Santa Clara pueblo and tourists in for the day.

In between batches of visitors, I soaked in Chuck Hannaford’s explanations of the various primitive tools and weapons that are part of the kit used in the educational outreach program sponsored by the Office of Archaeological Studies where Chuck and Jim both work. I already knew that the arrowhead was considered the “disposable” part of a spearhead or atlatl dart. However, many of the creative ways the primitive weapons makers had come up with to preserve the valuable straight wooden shafts were new to me.

Several tour groups came and went, then it was our turn to ascend the cliffs.

Our guide was Sam, a big burly man from Santa Clara pueblo, the Tewa group that is descended from the original inhabitants of these cliffs. There is still some debate as to where the inhabitants of Puye Cliffs came from originally. Some say they came from Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. However, many archeologists now feel the inhabitants were present in the Rio Grande valley long before the migrations from further north. Either way, Sam’s ancestors have lived in this region for thousands of years.

The cliff dwellings were in use when the Spanish came into New Mexico in 1598, although much of the population had moved into the lowlands where there was better farming and more water. During the pueblo revolt of 1680, the cliffs became one of the strongholds of the revolt. Today, the caves are vacant. However, Sam’s tour was sprinkled with anecdotes related to his own childhood, of visiting the cliffs with his father (who was also a guide) and of splashing with his brother in the water held in a catch basin built by his long-ago ancestors to supply their needs.

Puye Cliffs are made from relatively soft volcanic tuff – a stone formed from dense concentrations of volcanic ash. In this case, the ash was supplied by the explosion that created the Valles Caldera, a massive explosion that scattered debris as far as Kansas and Louisiana. The tuff could be easily hollowed out, making small caves that held heat in the winter and remained cool in the summer. The interior of these caves was plastered to help improve the natural insulation. Where the rocky shelf outside the caves permitted, blocks of tuff were used as bricks to make more roomy habitations. Although these exterior structures were gone, we could still see the holes in the cliff face where the narrow logs used to support the roofs had once rested.

Since the cliff dwellings occupied several levels connected by ladders, they reminded me of apartment buildings. As we walked along the trail, Sam pointed out various petroglyphs etched into the stone. In many cases, the pictures were the clan signs of the group that had occupied that particular area. Sometimes more than one clan sign was displayed side by side and may have indicated closely related clans.

Sam pointed out places where the interior of the caves had been sculpted to make living more comfortable. Among the most common adaptations were hollowed areas meant to hold water jugs. As Sam explained with a grin, water was very precious and in those relatively crowded spaces, it would be all too easy for an overactive child to spill the supplies. One of my favorite caves was the one where a weaver had once lived. Two holes in the wall showed where the top of the loom had been anchored.

The cliff dwellings were not the only place the inhabitants resided. On top of the mesa was a sprawling pueblo (now little more than a mound with scattered courses of blocks indicating where the rooms once stood). Here, too, were the kivas – the rounded buildings in which sacred dances and other rituals were held. All of this was framed by wide reaching views over the green forests, to the surrounding mountains.

Today, it is hard to imagine the vibrant community that once must have lived here. The quiet, windswept areas seem to belong very much to the snakes, rabbits, and birds that we glimpsed. One of Sam’s favorite stories was about the mountain lion who rambled among the caves just last year. Needless to say, tours were halted until the puma moved on, but Sam showed us a place where the big cat had leapt to use one of the ladders, scraping its claws against the soft stone, leaving its own mark to join the petroglyphs of the former inhabitants.

I found myself wondering what it would have been like to live at Puye. Would I have chosen one of the cave dwellings, neat and snug, caught between earth and sky? Would I have preferred to live on top of the mesa where the views stretch seemingly forever?

I’m not sure which would have been better.. I do know that I’ll go back someday. Maybe then I’ll decide.

May 16, 2013

TT: Egypt and Other Exotic Cultures

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back one for a discussion of that controversial topic: fan fiction. Then come and join me and Alan as we examine some of the more exotic settings for Fantasy fiction.

Exotic Lands, Fantastic Tales

JANE: It would be false modestly for me to take this topic – Fantasy based in historical/mythological material – much further without mentioning that I’ve delved into it a bit myself in my novel , The Buried Pyramid.

ALAN: I enjoyed The Buried Pyramid a lot. The first half of the novel is a completely traditional ripping yarn. There are mysterious coded messages, and hints of a shadowy evil that pursues the protagonists through the desert sands. You captured the sense of time and place beautifully – I could smell the unwashed bodies and taste the grit.

Then in the second half you changed the mood completely. We learn that the Egyptian gods have not gone away. There are plots afoot and sometimes even the gods themselves need help. The protagonists are soon closely involved with the gods and their schemes.

The segue from the grittily naturalistic adventure story of the first section to the fantasy story of the last section was handled really smoothly. One false step here could easily have broken the spell of the story. But the joins didn’t show at all. Well done!

What made you write the book this way?

JANE: I’m not sure. As I’ve said elsewhere, I write Fantasy and Science Fiction because my mind seems to “work” that way. I’ve always liked stories where, rather than exploration debunking the mystic, the mystic is revealed. And, I think, I wanted to write a story in which exploration of the mysteries of ancient Egypt did not revolve around a mummy and a lost love.

Research for The Buried Pyramid was a real challenge because, for the historical part of the novel, I needed to be up-to-date on the theories current in the late 1870′s, but for the “fantasy” section I needed to be as accurate as possible to what Egypt might have been like in the days of the pharaohs – and, specifically, in the days of my own fictional pharaoh, Neferankhhotep.

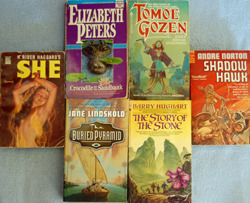

ALAN: As long as we’re on the topic of Egypt – they’re not really fantasy per se, but I’ve always enjoyed Elizabeth Peters’ novels about archeologist Amelia Peabody and her husband Emerson who have a fine old time exploring Egyptian ruins. The books are full of references to Egyptological history and myths. I learned a lot from them, as well as having fun with the stories. And one of the novels, The Last Camel Died At Noon, is almost a fantasy story – it plays with the “lost race” theme that Haggard (and Edgar Rice Burroughs) used so well in their books.

JANE: I really liked Crocodile on the Sandbank, but I’ve been more mixed about other of the Amelia Peabody novels. They started to seem like parodies of themselves. Also, I must admit, I could not stand the young Rameses, although he got somewhat more tolerable in other books.

ALAN: Ah, now there we differ – I found the young Ramses hilarious, literally laugh out loud funny. More than once Robin asked me what I was giggling about so I’d read the dialogue out to her and she usually collapsed into giggles as well. I was very sad when Ramses grew up and stopped being precocious.

JANE: To each their own!

Andre Norton wrote several novels using Egyptian motifs. Shadow Hawk is a straight historical, dealing with Egypt under the Hyksos. I like it a lot. She also did a more contemporary Egyptian novel: Wraiths of Time.

ALAN: I don’t want to sound as if I’m riding a hobby horse, but Henry Rider Haggard was also fairly obsessed with Egyptian mythology – indeed his novels were my first introduction to the subject. Wisdom’s Daughter tells the tale of the childhood of Ayesha, She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed, and in it we learn that she was a priestess of Isis before she came to the caves of Kor. Unfortunately, when she fell in love with Kallikrates, she had to renounce her vows (priestesses are supposed to be celibate) but even so she remained greatly influenced by her upbringing and all four of the novels about Ayesha are full of Egyptian mythological references.

Even in fairly straightforward historical novels such as Cleopatra, Haggard could not resist introducing mythological insights and there are many scenes in the book that can be read as direct interference by the gods. Of course it is a measure of Haggard’s skill as a writer that other interpretations are possible as well…

JANE: Switching myths and cultures, several Fantasy novelists have used material taken from Chinese and Japanese mythology. Among the Chinese variations, my personal favorites are the three novels by Barry Hughart: Bridge of Birds, Story of the Stone, and Eight Skilled Gentlemen. The first is probably the most indebted to a specific myth, but all of them use mythic elements.

ALAN: I’ve read the Hughart books and enjoyed them. Would you consider your own “Breaking The Wall” books to be in this tradition? I’m not familiar enough with Chinese mythology to know how much you and Hughart borrowed and how much (if anything) you made up out of whole cloth.

JANE: Not quite in the same tradition because Barry Hughart’s books are set in a China that never was, while mine are rooted in our world – and even the alternate China is firmly rooted in events that are historical to our world.

That said, pretty much all my Chinese material is rooted in actual Chinese myth and legend. That “actual” must be taken within context because the Burning of the Books – an historical event central to the novels – meant that a tremendous amount of material was lost and the Chinese have had to rebuild their cultural heritage.

I had a great deal of fun building a magical system around a combination of the elements in mah-jong as interpreted through Chinese mythological and cultural material. After a while, it started to have a logic of its own!

ALAN: That’s interesting. I didn’t realise that the Burning of the Books was a real historical event. I just looked up the details. It sounds horrid.

JANE: You think I’d lie to you? It really happened and it really was horrible!

Thinking of other mythic/historical traditions that have been used in Fantasy fiction, I’ve enjoyed several novels using Japanese material. Jessica Amanda Salmonson’s novels about Tomoe Gozen are set in Naipon, an alternate Japan, and use both the culture and feudal historical setting very nicely.

I also enjoyed Kij Johnson’s Fox Woman quite a bit, although I felt that Fudoki, which featured a cat, was a bit of a re-tread. Still, she handled her material with skill and elegance.

However, I will admit that these novels involve a bit more of a stretch, since neither the cultures nor their traditional religions are taught in American schools. By contrast – probably because the root cultures had such an influence of “western” civilization – most American readers are familiar with a smattering of Greek, Roman, and Norse mythology.

ALAN: I’ve always found fantasy novels that refer to cultures and myths that are outside of the Western mainstream very hard to come to grips with for exactly that reason. A good example of this would be stories that make use of the traditional North American myths – perhaps these are more familiar to American readers, but they are certainly quite outside my own experience.

Roger Zelazny, for example, wrote a novel called Eye Of Cat, which depended very much on Navajo culture. However, my unfamiliarity with that culture made it very difficult for me to understand what the characters were doing. I found the story confusing and fairly impenetrable. It remains one of my least favourite of his books for that reason.

JANE: Ah… I actually taught Eye of Cat as part of a science fiction course I did years ago. My experiences – and several others related to Zelazny’s work with myth and history – are rich topics that I’d like to save it for next time.

May 15, 2013

Fan Fiction

Last week I wrote about my dislike of fiction based on someone else’s fictional characters or universe. (See WW 5-08-13 for exactly what I mean by this.) I don’t know why, but I never anticipated that the subject of “fan fiction” would come up in response.

Fan

How do I define fan fiction and how is it different from the type of novels I discussed last week?

The biggest difference is that fan fiction is often written about works that are actively owned by someone else, rather than being in the public domain. Sherlock Holmes is (mostly) in the public domain. So is Jane Austen. So is the Wizard of Oz. Or Jane Eyre. Even though a single unique author wrote the work, that author’s copyright has expired and the work is now open for use by the greater public.

What takes a work out of copyright? Time. Pretty much nothing else. No. It doesn’t matter if the work is no longer in print. That doesn’t mean it’s in the public domain, any more than the fact that you’re not wearing a certain pair of shoes means that someone else can take them from your closet and wear them.

Always be careful about assuming a work is no longer protected by copyright. Copyrights can be renewed. Translations are copyrighted separately than the work from which they were translated. Sometimes (as in the case of the poet Emily Dickinson), a work may be published after the author’s death and so the copyright has nothing to do with the life span of the original author, but rather with the date of first publication of the particular piece.

Fan fiction has a long tradition. However, only recently could writers of fan fiction easily publish their work for a large audience. Before that, availability was usually limited by the number of copies the fan author could produce. The mimeographed fanzine was later succeeded by the photocopier, but both of these involved some expense and – in many cases – a considerable outlay for postage.

The Internet has changed all of that. Now fan writers can publish their take on Harry Potter or Game of Thrones or whatever takes their fancy at the push of a button or two. Moreover, instead of being available to a few hundred people, the work is available to the world. (Available doesn’t mean read by, just available.)

Is this really publishing? Fan writers may not think so – after all, no one has paid them for their work. However, according to a prominent intellectual properties attorney who I consulted before writing this, yes, posting something on the Internet counts as publishing, even if no money changes hands. Therefore, it is a violation of the original author’s copyrighted material.

I asked several writers how they felt about fan fiction based on their work. Most said that, although they were flattered, even if they did not actively attempt to “shut down” the writer, they would just as soon not have people writing fan fiction and publishing it on the Internet. Many stated that they do not read fan fiction based on their own works lest at some future time there be a potential conflict.

How do I feel? Pretty much the same. I’ve been repeatedly approached by fans of my works asking if they can write fan fiction or a script or do a comic book based on my works. My answer is always the same… What you do in private, to stimulate your personal creativity, is your own business. However, if you really love my worlds and characters, please don’t attempt to profit from them, even if the only profit is a boost to your ego.

(I should note that the intellectual property attorney I consulted said that “commercial gain” can be widely interpreted by courts. Simply driving a lot of traffic to your website can be construed as commercial gain, especially if the website or blog runs advertisements or in any way generates income for anyone at all.)

If you do think you have written a saleable screenplay or script, then talk to my agent. Don’t show it to me. I won’t read it. Worse. I really can’t read it without setting myself up for a potentially ugly situation down the road.

Ugly? Here’s what I mean…

About the time I was starting my career, a Very Famous Science Fiction Writer (VFSFW) who shall remain nameless was sued by someone who claimed that the VFSFW had stolen his idea. As evidence, the person bringing the suit produced a short story and a letter from the VFSFW commenting on that short story. A jury who knew nothing about SF – including how many shared concepts there are (things like faster than light travel or space colonies or anti-gravity) decided that VFSFW had taken advantage of the poor new writer. Damages were, reportedly, considerable.

This isn’t precisely the same situation as fan fiction. However, fan fiction holds the potential for the same sort of situation – or even worse. After all, the characters, setting, and even elements of plot may be the same. So, sadly, professional writers are forced to protect themselves by walking a tightrope between awareness and ignorance. The situation becomes even worse with trademarked material, but I’m not going into that.

Yes. There is fair use, but fan fiction rarely stays within those very limited parameters, so I’m not going into that particular issue here, either. Sometimes even a very limited reference to another writer’s work or setting – such as Walter Jon Williams’ reference to “Damnation Alley” in his novel Hardwired – can make a publisher insist on permission from the original author before they will publish the work in question.

I’m not immune to the appeal of writing fan fiction. I’ve done my share – as has almost every writer I know. Some fan fiction is written because the writer has an idea about something the characters might have done but didn’t. Another reason is that the fan fiction writer has come up with a story that will smooth out a perceived problem within the official story line. Another common reason for writing fan fiction is because the series or book has ended, and the fan simply needs to fill the void.

Fan fiction can be a great way to write with “training wheels.” (I have used this term for years and was amused when my fellow writer Steve Gould – author of Jumper and the recently published Impulse – used it in his response to my query.) After all, someone else has created the characters, the setting (including all the world building – a thing that looks easy until you start doing it), and may have even provided the seed for the plot.

All the fan writer has to do is come up with the rest of the plot and maybe a supporting character or two. It’s a great way to learn. But it’s not a great way to publish.

Works such as those based on Sherlock Holmes or the Wizard of Oz, or sequels approved by an author’s estate, or even collaborative works may give the uninformed writer the idea that anything published is up for grabs. It isn’t. Keep your fan fiction for yourself and a small group of friends. Everyone will be happier for it.

May 9, 2013

TT: Mixing Myth and History

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back one and find out what sort of fiction can drive me nuts… Then join me and Alan as we continue our voyage into the realms of myth fantastic.

Swann and Anderson

JANE: Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve been talking about Fantasy fiction that uses historical and mythological material for its foundations. I’m certainly far from done!

ALAN: Me too! It’s one of my hobby horses and I tend to ride it to death.

JANE: An author I’d like to mention is Thomas Burnett Swann. He wrote a bunch of novels that used historical events but retold them with myth and legend blended in. For example, Lady of the Bees tells the story of Romulus and Remus but includes dryads, fauns, and other mythological creatures. Swann also shifts the emphasis of the tale in a very interesting manner that, while not violating the “history” (if you can call a legend “history”), reinterprets the motivations of those involved.

His late novel, The Gods Abide, tells what happened to the “pagan” deities in the time of Constantine. In his novels, Swann repeatedly addressed an issue that I’d wondered about since I was a little girl, suddenly realizing that myths were different from fairy tales in that fairy tales were just stories, but myths had been someone’s religion. Even then I wondered, what happens to gods when their worshipers change alliance? Swann provided some interesting answers.

ALAN: Sometimes the technique can work the other way round. Henry Treece, who I mentioned last time, did exactly the opposite with the Greek myths. He wrote three novels – Jason, Elektra and Oedipus (guess what stories they told?), and he presented the stories as factual history with all trace of myth and magic removed (the golden fleece was just a grubby old sheepskin flecked with traces of alluvial gold). I’m not completely convinced that’s a good idea!

JANE: Oh! I remember hearing about that… That ratty sheepskin did take some of the romance out of the tale. By contrast, Mary Renault, who I’ve wandered on about (WW 1-18-12), could do a realistic treatment of mythological events without reducing the sense of wonder. Her re-tellings of the myth of Theseus – The King Must Die and The Bull From the Sea – are wonderful. The Mask of Apollo, while purely historical, adds in the spiritual dimension that would have been a big part of the participant’s lives.

ALAN: An author who was an eye opener for me was Poul Anderson. Not many of his books were published in England, but I avidly devoured the few that appeared. They were science fiction rather than fantasy, but several of them involved time travel back to some rather grim historical milieus (a word I’d never heard until I started reading Anderson!). One of them, The Corridors of Time, was my first exposure to the idea of the Earth Mother, the Goddess. That novel remains a firm favourite of mine because of that. Of course it helps that it’s a brilliant story in its own right!

JANE: I’m a huge Anderson fan myself. His Earthbook of Stormgate is a marvelous piece, a short fiction collection that reads like a novel. It doesn’t hurt that it includes the novella “The Man Who Counts” – released as a novel with the unfortunate title, War of the Wingmen. Even in these purely science fictional tales, Anderson shows his fascination for the mythic in that the frame story is an exchange of tales between humans and winged aliens.

ALAN: I’d heard rumours of fantasy novels that Anderson had written and eventually somebody published an English edition of The Broken Sword. I was absolutely blown away by the story. It’s an epic tale firmly based on the Norse view of the world. Orm the Strong kills the family of a witch. She allies herself with the elves who steal Orm’s son leaving a changeling in his place. The elves name Orm’s baby Skafloc and raise him as their own.

I’d never seen elves like these before. Mean spirited and vengeful, some might almost say evil, certainly they were cold and cruel and had little regard for the welfare of others. This was a dark and thoroughly depressing book. The villains were nasty and so were the heroes. I loved it.

JANE: It’s been a long time since I read The Broken Sword, but I remembered liking it.

ALAN: Anderson was fascinated by the Norse myths and he incorporated references to them in many of his novels. And then some time in the 1970s he wrote Hrolf Kraki’s Saga which, as the title implies, is a Norse saga told in a very Norse style. I was never very clear whether he made it up out of whole cloth or whether he fleshed out existing fragments of a real saga, but it certainly sounded very authentic. It was nominated for a British Fantasy Award. I must confess I found it hard to read; the writing style was very traditionally Norse, somewhat old-fashioned in tone and quite repetitious, with long passages in the passive voice. Not my cup of tea. But nevertheless I have to admit that it’s a tour de force.

JANE: Ah… I differ with you there. I read Hrolf Kraki’s Saga when I was in college and loved it almost to the point of obsession. The Norse prose style must have resonated with my Scandinavian blood.

Hrolf Kraki was not invented by Anderson. He was the most famous of the Danish kings in the “heroic age.” He even had a role in Beowulf, under the name of Hrothulf. I believe that what Anderson did in Hrolf Kraki’s Saga was similar to what Evangeline Walton did with the Mabinogi – he took what he wanted from a wide body of material about Hrolf Kraki, most especially from the Hrolfssaga, and turned it into a novel.

ALAN: Ah, I see. Thanks – I didn’t know that.

JANE: By the way, since we’re talking about Poul Anderson’s work, I must tell a little tale. Back in the mid-nineties, Steve (S.M.) Stirling invited Jim and me to come over, have dinner, and meet Poul and Karen Anderson. Poul was working on a book set in the American Southwest, and Steve thought Poul might enjoy picking Jim’s brain for details. Poul did, and Jim is mentioned in the acknowledgments for Operation Luna. We have our signed copy – a gift from Poul – along with his thank you note, among our treasures. A charming person, as well as an excellent writer.

ALAN: Most definitely! I have an autographed copy of The Earth Book Of Stormgate and, though I only spoke to Poul for a short time as he signed his name, I remember him as a very pleasant person, very approachable and easy to talk with. I was pleased to find that a writer I admired so much was also someone whose company I enjoyed.

JANE: I have an idea for where I’d like to take this next, but I need to get to work. So, next time?

May 8, 2013

Homage or Hack Work?

Every reader has quirks. Some people don’t like graphic sex scenes. Some people find detailed combat dull. Some people don’t care how many human characters are killed in the course of a novel, but kill an animal – especially a cat or dog – and the author will be in, well, the dog house…

Hatchet Jobs?

My quirk is a little different. I really dislike books that are recognizably based on someone else’s novels or characters or named setting.

By this I don’t mean collaborations, where the original author is part of the project. I’ve done several of these, most recently Fire Season with David Weber (as well as the forthcoming Treecat Wars) which use Weber’s character, Stephanie Harrington. I’ve also written several “Honorverse” novellas at Weber’s invitation. I’ve written a Berserker story with Fred Saberhagen and expanded the history of his Mask of the Sun (in the anthology, Golden Reflections). I wrote a story for the Jack Williamson tribute anthology, The Williamson Effect. I also had my go at Larry Niven’s Known Space in a recent Man/Kzin War anthology.

However, what pushes my buttons to the point that I won’t even pick up the novel are those books that are based around highly recognizable fictional characters: the many refurbishments of Sherlock Holmes, the increasingly numerous expansions of cast of Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice, the Wizard of Oz revamped, Jane Eyre…

As an author, I did step over this line twice. Once, when invited to do a story for the anthology Fantastic Alice. However, even then I was very careful to tell my tale “outside” of the Alice in Wonderland canon, not just recycle Alice and the Queen of Hearts or the Walrus and the Carpenter… My story was from the point of view of the Dormouse and tells what happens when he’s in the teapot. To tell the truth, if asked today, when the market seems increasingly glutted with novels based on other people’s works, I would probably decline. The other time was in a Lovecraft anthology. Since Lovecraft opened up the gates to his uncanny realms during his own lifetime, I didn’t feel I was abusing his property.

Recently, my friend Tori asked me why fiction – especially novels – based on other writer’s works bothers me so much, especially since I’m not bothered by stories that use mythology or folklore as a foundation.

Basically, it’s because while mythology and folklore belong to a culture – to a group of people who share an ethnic or religious background – fictional characters belong to that one author. I can’t help but feel as if these works – especially on-going series that don’t even bother to file off the serial numbers – are less affectionate homages, than attempts to capitalize on someone else’s works. Even when it’s legal – as with characters whose original novels have entered the public domain – I just don’t care for it.

The Iliad and the Odyssey or the Aeneid have named authors (in this case Homer and Virgil), but still fall into the “mythology and folklore” category for me, since it’s quite likely that the “authors” were closer to compilers of long-standing oral tradition. That is, Homer and Virgil took material that was already being told around the fireside and arranged it into what has become the “official” version.

Recently, as we were working on a future Tangent, Alan Robson mentioned how certain fictional elements have become part of our modern “mythology”: Dracula, Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes, Frankenstein, Jack the Ripper (a historical figure, but one who has been fictionalized so often that most people couldn’t sort apart the fiction elements from the non-fictional) and others. While in the context of our discussion, I saw his point, still…

Frankly, I don’t read the stuff. If you want me as a reader, don’t ride into the literary arena on someone else’s coattails. Give me your own people and places. I’m much more likely to give your works a try.

Where is the line between “homage” – a work written because the writer is deeply attached to a piece – and exploitation? I’d be interested to know what you think.