Jane Lindskold's Blog, page 147

August 15, 2013

TT: The Humor Boom

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back one and learn what “butt-heads” had to do with my lasting fondness for a certain popular TV SF show. Then join me and Alan as we take a look at a couple of writers who contributed hugely to the boom in humorous SF/F that made the 1980’s such a funny time to live.

Some Very Funny Books

JANE: Although humorous Science Fiction and Fantasy was certainly around long before, there seemed to be a boom in the 1980’s. Oddly enough, there was also a boom in Horror around the same time. Probably something in the psychological landscape of the time.

ALAN: Ah yes. All those hilarious novels by Stephen King. I remember them well.

JANE: Smart aleck!

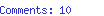

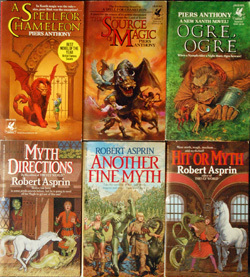

Anyhow, when I think back, two authors immediately spring to mind: Piers Anthony and Robert Lynn Asprin. The first works in their most popular series –Anthony’s “Xanth” and Asprin’s “Myth Adventures” – appeared in the late 1970’s, but by the 1980’s both series were going strong.

ALAN: I quite enjoyed the early Xanth novels but I felt the series deteriorated in quality as it progressed. Anthony also wrote a very funny fix-up novel called Prostho Plus which was all about the adventures of an intergalactic dentist. As someone with a dentist phobia, I found it both amusing and squirmy!

JANE: I agree with you about Xanth. I thought A Spell for Chameleon was a very thoughtful look at the different and contradictory roles a woman is expected to play in the course of her life. I very much enjoyed The Source of Magic and Castle Roogna. However, by Centaur Isle, I felt the puns were coming to dominate the story – the forcing the story to serve the joke, an element you mentioned last week as bothering you as a weakening trait in so much humorous fiction.

I did find that the Xanth stories that focused on non-human characters held my attention longer. I recall liking Ogre, Ogre and I thought Night Mare was very interesting.

ALAN: I also enjoyed Asprin’s early “Myth Adventure” novels, but I felt that he blotted his copy book with Little Myth Marker which was simply a re-telling of Damon Runyon’s Little Miss Marker. I stopped reading Asprin’s books after that.

JANE: I loved the early “Myth Adventure” books. One element that kept me reading was that beneath the puns was a very solid coming of age story that continued into a story about coming to terms with changing relationships and changing roles in life. However, I agree that eventually Asprin lost his sense of where the heart of the stories rested.

Did I ever tell you I interviewed Bob Asprin back in 1992?

ALAN: No – I didn’t know that. Tell me more!

JANE: I’d met Bob at Magnum Opus Con in South Carolina. (That’s where I met David Weber, too. That convention has a lot to answer for. That meeting directly led to Roger asking Bob to be one of the contributors to Forever After, a humorous novel in four parts, to which I also contributed a section.)

The first time we met, we ended up going to the airport at the same time. Bob came into my concourse with me and, while he signed books for my sister – (I never got him to sign one for me, something I regret), – I asked him some questions about writing. His answers were so interesting that I queried one of the academic SF publications to see if they wanted an article. They said “yes,” and the next year I taped an interview. (The article came out in Extrapolation, November 1993.)

ALAN: Is it available on-line anywhere? I wouldn’t mind reading that.

JANE: I don’t know… Maybe one of our readers would.

Anyhow, Bob talked a lot about how the interplay of business and writing had influenced his approach to what he did. He started as an editor of the seminal “Thieves World” anthology series – the one that pretty much gave birth to the entire “shared world” anthology concept. On the strength of that, he was able to sell his original fiction. He saw himself as an entertainer first and writing as only one of the ways he entertained.

Bob also indicated that there was a lot of insecurity behind his “funny” – not an uncommon trait in comedians.

ALAN: Indeed. Witness Stephen Fry’s battles with depression that have brought him more than once to the brink of suicide. And yet Stephen Fry is one of the funniest men on television…

JANE: I had no idea about Stephen Fry, but I agree with you about his talent. I am especially fond of his portrayal of Jeeves.

Anyhow, I remember Bob Asprin telling Roger how he’d just gotten a huge advance for a novel. I forget the amount, but it was pretty impressive. He said, “But I don’t know how to write a $X00,000 novel.” Roger responded with typical gentle wisdom. “They don’t want you to do something other than what you’re already doing. They simply have realized what your work is worth in the market.”

But I have wondered if success is what ultimately undid him.

ALAN: It must have been very stressful for him, so I imagine there’s more than a grain of truth in your speculation.

JANE: I listened to those tapes again when I saw what direction we were going in our chat. I’d just read your comment about “hilarious novels by Stephen King” so you can imagine my shock when Bob suddenly started talking about how close horror and humor really were, paraphrasing Stephen King saying that handled wrong horror could become humorous and humor a source of horror.

ALAN: Oh indeed. They are often two sides of the same coin. The Frankenstein story can be quite shuddersome when taken seriously and yet Mel Brooks managed to turn it into one of the funniest films I’ve ever seen when he made Young Frankenstein. It’s really only a matter of emphasis.

JANE: Yes… I’ve always thought Hamlet has great room for humor. I’ve even written a story…

Going back to Piers Anthony, again I wonder if success weakened Xanth. When I read the entry on him in Supernatural Fiction Writers: Contemporary Fantasy and Horror, the article mentioned that Anthony actively solicited reader feedback for the series, up to and including plot ideas and puns, then incorporated the material into the series. The writer of the article seemed to think this gave the series a certain “freshness,” but I think it could lead to twisting of the plot to make a joke work.

ALAN: Absolutely! I found no freshness in these books. I did attempt to read some of the later Xanth novels and Piers Anthony would often have an introduction or afterword commenting about the reader input. But somehow the stories always seemed stale and forced to me. It was almost as if he was going through a semi-mechanical process to generate the book, with only half his mind on what he was doing. Too many silly jokes and not nearly enough story.

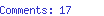

JANE: This brings me back to what I said last week at the end of our discussion of Terry Pratchett. To me, Pratchett never seems to write from anything but the heart – even when that means his book isn’t going to be as “funny” as his readers might expect. Some of my favorites – Small Gods, Nightwatch and Hogfather – are often not funny at all… But they are very wise and the wisdom blossoms forth from the humor.

ALAN: That’s why he’s so successful at what he does. And, of course, now that we’ve exposed his secret to the world, anyone can just follow the formula and be as successful as Pterry! Oh, if only it really was that easy…

JANE: Easy… Yeah. Right. The man is an amazing writer.

Now, mostly thanks to me, this has gotten a bit long. Perhaps next time we could spin through some other aspects of SF/F humor.

August 14, 2013

The Other Great Doorway

Last week we chatted a bit about the books that showed us that SF/F had something to offer that other genres did not. This past weekend, when Jim and my friends Sue and Hilary Estell came over, we found ourselves extending the discussion to include television programs.

Heading Toward the Final Frontier

Although most of these – at least for me – did not have the idea-jolting impact I found in books, they did offer a visual and auditory addition to the story experience that made them compelling in their own unique ways.

Sue, Jim, and I are all of an age that “classic” Star Trek captured our imaginations. Jim watched it during its original release when he was in high school. Sue caught it in re-runs when she was in college. I didn’t catch Star Trek until re-runs and those very sporadically – especially at first. In fact, for the longest time, I thought there was one episode only, “The Menagerie,” because that was the one I’d see in passing, usually when being chased outside to play on some summer afternoon.

My parents weren’t into having kids watch TV. Except for the Sunday evening ritual of Wild Kingdom and The Wonderful World of Disney, I don’t remember watching much TV until was about twelve and started babysitting for other people. Then, whether with the kids I was babysitting (many of whom seemed glued to televisions) or after the kids had gone to bed, I caught up on my TV viewing.

That’s when I discovered that the show with the “butt-heads,” as we had dubbed the aliens in “The Menagerie,” actually had a whole lot of episodes. I also learned that the “butt-head” story, which had always confused me, had done so because it was a two-part story. Catching it in fragments, out of order, had created a very surreal viewing experience.

After that, although I never became a “Trekkie,” I was certainly hooked. I watched every episode more than once or twice or three times. I read the James Blish short stories based on the episodes. Later, at the Smithsonian of all places, I bought a boxed set of the first four “Star Log” stories by Alan Dean Foster. These were based on the animated Star Trek, which I’d never seen, so they were very exciting – all new Star Trek. Later, I picked up others in the series.

These were the days before media tie-in novels cluttered bookstore shelves. Even when tie-ins started appearing, there were only a few that caught my imagination. The New Voyages collection had some good stories, as I recall, but most of the original novels were missing some intangible quality I found on the screen. (Later I’d find a couple really good ones, but going into that topic could be its own Wandering!)

I owned two non-fiction Star Trek books – The World of Star Trek and The Making of Star Trek – but, although I read these through repeatedly, they mostly served to confirm me in a preference that continues to this day. Even if I love a show, I don’t care about the actors or how special effects were designed. Although I enjoyed a few anecdotes, especially those about how the set design people created a starship on a shoestring budget, mostly I didn’t want the fourth wall broken – and I still don’t. Let me keep my illusions and believe that , on some deep level, it’s all real.

I guess because of my willingness to believe the Star Trek universe was “real,” I puzzled over little unexplained details. Initially, I watched Star Trek on a black and white television. (For that reason, the joke about “red shirts” meant nothing to me the first time I heard it.) When I saw the show in color, I tried to work out what each different color of uniform shirt indicated. (And wondered why engineering and security apparently wore the same color.) I also wondered what the different lengths of the braid on the cuffs meant. Remember, these were the days before VCRs or the ability to “pause” and study a screen. I had to gather my information on the fly!

Stardates were a particular puzzle. I kept a notepad with the dates mentioned in a given episode, then tried to figure out the order in which the different stories happened. You can imagine my disappointment when I realized these dates were tossed out at random and were not an indication of continuity.

All of this was great fun and, I think, contributed to my appreciation of the little details that can make or break a story world.

Star Trek was certainly my favorite SF TV show, but those late night babysitting gigs exposed me to a lot I hadn’t caught the first time around. Mission: Impossible was a favorite (although I was a bit startled to see Spock without his ears and characteristic haircut). I liked The Six Million Dollar Man, but never got into The Bionic Woman – especially after they introduced the stupid dog. I could stretch my credulity to believe that a school teacher might get the bionic add-ons, — especially with the threat her very expensive boyfriend might go AWOL if she wasn’t saved – but a dog? A kid?

I watched other shows occasionally, but usually those with continuing casts, rather than anthology series like The Twilight Zone.

Sue Estell was a much more voracious viewer. I asked her what stories grabbed hold of her imagination. After noting that she couldn’t leave out the impact of the Star Wars movies, she went on to say that she had continued to follow the various Star Trek incarnations, liking Next Generation quite a bit, and finding something to value in most of the others. She then noted a range of programs, stretching to the present day: “The Outer Limits and Twilight Zone, Lost in Space, Time Tunnel, Land of the Giants, Battlestar Galactica (both the laughable old one and the edgier new one), V, SeaQuest, Babylon 5, Quantum Leap, StarGate SG1 and Atlantis (I did NOT like StarGate: Universe), Farscape, and more. I watched just about anything on the SciFi channel in past years (before their programming managers went mad and classified wrestling as SciFi), except for The X-Files, which never drew me in.”

Sue’s “twenty-something” daughter, Hilary, has a viewing history that overlaps her mom’s, then takes off in new directions: “I think Star Trek all around was a starter in sci fi for me too, simply because Mom watched it a lot when I was little and it’s the kind of show I grew up knowing about. I especially remember the original Trek and Next Generation. I didn’t sit down to watch shows with Mom though until later, when I saw Farscape and Stargate SG-1, both of which I really, really enjoyed. Although Stargate started before Farscape, I know I only started watching it in season 3, so I’m pretty sure Farscape was The One that really started everything. (Show-wise at least. I’m in agreement with Mom about the impact Star Wars had on me for watching sci-fi/fantasy). I also watched about two seasons of Stargate Atlantis before losing interest, and then got into Firefly late to the game after I saw reruns on the Sci Fi channel. My most recent choice isn’t actually on the tv really; it’s a web-series called The Guild, which is about 6 gamers trying to cope with real life.”

As for me, when I went to college, my TV viewing pretty much ended for four years, as neither I nor my roommates had televisions. The one exception was The Muppet Show, which my then boyfriend’s roommates watched with great fidelity. Even after my undergrad years, when I moved out of the dorms and had a little TV, I didn’t get back into watching in a big way. However, I did watch some “after school” animated programs.

These were the days when SF/Fantasy was becoming more prevalent, even in the afternoon TV shows. I really liked Thundercats, at least for the first season. After it became a hit, characters and stories were altered to provide more merchandizing opportunities. Sigh… He Man and the Masters of the Universe and Jayce and the Wheeled Warriors were fun, too, although not up to the standard of Thundercats

When I finished grad school and moved to Lynchburg, Virginia, to teach at Lynchburg College, I had cable for the first time in my adult life. However, even cable was not enough to draw me back into regular television watching. I remember liking some of Quantum Leap, but I was too busy (this was when I was both teaching college for the first time and trying to break into selling fiction) to spend time watching much television. Gaming was my chosen break and stress reliever, followed by – thanks to Steve Hogge, a young man with whom I gamed, and southern fan Diana Bringardner – my first opportunity to watch more than the occasional bit of anime. (That is another topic, one I touched on in the WW for 3-10-10, “Animated Enthusiasm.”) These days, anime remains my main viewing choice.

Clearly, visual media is the other great doorway into SF/F. Nor is there a dividing line between media fans and reading fans. Both the Estells are voracious readers. (That’s how I met them.)

What television programs were your favorites? Which ones can you forgive for their flaws because they showed you places that made you dream richer dreams? I haven’t really gone into movies here (so many stories, so little time), but feel free to include them!

August 8, 2013

TT: Humorous SF/F

Looking for the Wednesday Wanderings? Just page back one and join me, George R.R. Martin, Ellen Datlow, Steve Gould, and many other writers, editors, and devoted readers as we wander on about the books that made a difference when we were just getting started reading SF/F. Then come back and have a laugh with me and Alan as we take a look at what we find funny.

JANE: One type of SF/F I’ve really wanted to discuss with you is humorous SF/F. I think it would be fascinating to find out where humor does and does not cross cultural (not to mention gender and age) lines.

Books of Wit and Wisdom

ALAN: It’s an all or nothing thing – you can’t be a little bit funny. Either it works or it doesn’t. It’s funny or it isn’t.

JANE: Before we get started, I should warn you. I strongly suspect I don’t have a sense of humor or, if I do, it’s a bit skewed because I often don’t find funny things other people find hilarious. Here’s an example…

Are you familiar with the movie Raising Arizona?

ALAN: I know of it, but it’s a movie I’ve gone out of my way to avoid seeing because I know I’ll hate it.

JANE: Hmm… Then you probably have heard it’s about the lengths to which a childless couple will go to acquire a baby of their very own.

Jim thought it was one of the funniest movies he’d ever seen – not because he’s particularly cruel to children or anything, but because of the outrageous situations. So, when we were dating, he rented it to show me. He was appalled to discover that I found it very, very sad. Maybe I’d known too many people who desperately wanted children, but I didn’t find the childless couple’s predicament funny at all. I also didn’t find what the baby went through funny either…

So, be warned, you’re going to try to discuss humor with someone who doesn’t find lots of funny things funny at all…

ALAN: Well actually, measuring by that yardstick, I think we have rather similar tastes. I find no humour in other people’s tragedies and disasters. Perhaps I’m just too empathic.

JANE: Good, then, we won’t be advocating humor based on cruelty, but I bet we’ll be able to find a lot we both think is funny.

From the “tour” of Australia we did via The Last Continent, I already know we both love and admire the works of Terry Pratchett.

ALAN: We actually wrote four of them: 9/2/2012 – Visiting the Last Continent, 16/2/2012 – Legends of the Last Continent, 23/2/2012 – Meat Pies and Cork Hats, 1/3/2012 – Strine and Newzild.

JANE: Even if you do insist on writing the dates all wrong, thank you very much!

Anyhow, from comments you have made here and there, I realize that sometimes I’m missing a lot that a British audience would immediately grasp. For example, I’d never realized that many of Nanny Ogg’s bawdy songs were in the tradition of the Pantomime Dame and music hall burlesque.

I wonder what else I might have missed?

ALAN: You need to read The Annotated Pratchett File which is a compendium explaining the many, many, many references that Pterry builds into his books. It can be found on the L-Space Web (named, of course, after Pterry’s delightful notion that all libraries are interconnected in L-Space). You can waste many happy hours browsing through it.

JANE: Pterry? You’ve used that term before. I suspect it is a joke. Can you explain it?

ALAN: Pratchett has been known as Pterry ever since a very early Discworld novel called Pyramids which was set in the Discworld version of Egypt and which featured characters called Ptraci and Ptaclusp, etc. — obvious references to Ptolemy, of course. I thought the joke was well-known, but perhaps it hasn’t made it over the pond. Certainly it’s ubiquitous in Right Pondia, to the extent that I actually find it difficult to write Terry. The word just plain looks wrong without the silent P…

JANE: Ah! It was a joke, but very much an “in” joke since, if you don’t know the linguistic gimmick in Pyramids, it’s not going to make any sense.

The Annotated Pratchett File sounds like a very attractive time eater! Could you maybe give one small example of the treasures we might find?

ALAN: How about this from Small Gods where the book title Ego-Video Liber Deorum is translated as Gods: A Spotter’s Guide. The annotation says:

“Actually, the dog-Latin translates more literally to The I-Spy Book of Gods. I-Spy books are little books for children with lists of things to look out for. When you see one of these things you tick a box and get some points. When you get enough points you can send off for a badge. They have titles like The I-Spy Book of Birds and The I-Spy Book of Cars.”

JANE: Lovely! We have similar games here, but I do think the “I spy with my little eye…” probably came from you folks.

I think that one reason Pratchett’s humor works cross culturally is that much of his humor is universal. British or American, a reader is going to find the idea of an orangutan librarian funny. However, it’s Pratchett’s particular genius that he can make the idea appealing and strangely practical as well.

ALAN: The thing that makes the books work so well for me is that they contain almost no jokes (I seldom find jokes amusing). The humour rises naturally out of the situation and is often not funny at all to the people involved. I’ve heard Pterry talk about this aspect of the Discworld many times. An example he often uses is the character of Mr Ixolite, a banshee who has lost his voice. He cannot stand on the roof and howl. All he can do is write “Oooh! Oooh! Oooh!” on a piece of paper and push it under the door. From our point of view this is funny, but consider it from Mr Ixolite’s point of view and it becomes a tragedy – he’s lost his whole reason for living. He can’t do what he’s supposed to do. It must be unbearable for him. So why are we laughing?

The art of the theatre is symbolized by the masks of comedy and tragedy. There’s no doubt that the two are closely related. And I’m uncomfortably aware that I’m contradicting myself here. I find Mr Ixolite funny for exactly the same reason that I don’t find Raising Arizona funny.

JANE: Certainly this is true. Many of Shakespeare’s comedies, for example, only fail to be tragedies because the resolution of the play ends with a marriage rather than a funeral. The same can be said for Mr. Ixolite or Otto, the vampire who insists of using flash photography, even though the bright light reduces him to a heap of ash. Their actions are comic because they have figured out ways to cope, despite their disabilities.

ALAN: I hadn’t thought of that, but you’re right. That’s almost certainly why I can laugh at them with a clear conscience.

JANE: So I’ll agree… To a point. Mr. Pratchett is not above the Pun. Indeed, one reason I will not listen to his works on audio is that I like it when one of his puns sneaks up on me. I read by shape, rather than by sound, so I was well into Small Gods before I realized the main character, a monk named “Brutha,” was, in fact, “Brother Brother.”

The one that really snuck up on me were the revered Ankh-Morpork firm of Burleigh and Stronginthearm. American English does not always pronounce “leigh” as “lee” so while I caught the silliness in the second word, I completely missed that the first should be pronounced “burly.” When I did, I was so delighted that I had to run off and make sure Jim caught it, too!

ALAN: As you know, I’m from Yorkshire. We have a saying: Yorkshire born and Yorkshire bred, strong in the arm and thick in the head. I’ve no idea if Pterry was referencing this, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised…

JANE: Eep! You’re admitting to it?

As for “jokes,” I’m not sure how you’d define that in prose… Pratchett certainly is not above taking a situation and taking it to its extreme for the sake of humor. The scene that springs to mind is the one in Guards, Guards where it’s going to take a one in a million shot to hit the dragon in its vulnerable spot. The positions into which Sergeant Colon is twisted to make sure the shot might qualify as a one in a million shot are a very visual joke. And so is what he falls into when he falls…

Wouldn’t you call that a joke? It’s certainly seemed like a joke to me. Yes, I know the situation wasn’t funny to the characters – since when is a dragon attack funny? – but this seems different from the plight of Mr. Ixiolite.

ALAN: And as Pterry well knows, one in a million chances work nine times out of ten…

Actually you’re right. But Pterry’s jokes tend to arise naturally from the situation. There are some so-called humorous novels where the situations are twisted to fit the joke and these never work for me. I can’t think of any SF/F examples but, in the mainstream Tom Sharpe is a very popular writer, but I’ve bounced off every one of his novels that I’ve tried to read for that very reason.

JANE: I absolutely understand… A careful sculpting works – as in Roger Zelazny’s classic “Then the fit hit the Shan” from Lord of Light – but when the story is wrenched around and forced to be “funny” it usually fails horribly.

There’s another element in Pratchett’s humor that can’t be overlooked. He has the ability to take humor and twist it into wisdom.

One of my favorite examples comes from Small Gods. The novel opens with one of those “cosmic” passages that violate just about every rule for narrative hooks by being strange and nearly unintelligible. The theme of this one is tortoises and eagles. It ends with the line “One day a tortoise will learn to fly.” And when it happens… Heavens above! It’s both a laugh out loud scene and one to bring tears to your eyes…

That combination doesn’t happen very often.

As we have already proven, we can do multiple posts just on Terry Pratchett’s work. However, there are other writers of humorous SF/F. Let’s move on to some of these works.

August 7, 2013

Books that Make a Difference

This past weekend, Jim and I were chatting about science fiction and fantasy with our friends Kris Dorland and Kennard Wilson. Eventually, the subject ambled around to those books that are special to individual readers because the ideas hit them at a particularly receptive point and the world starts opening up.

Just a few books…

Kris spoke movingly about how much Anne McCaffery’s Menolly books had meant to her, when she discovered them as a fifteen-year-old who didn’t quite fit in. However, almost as important were the discussions she had about books with two friends, one of whom was devoted to Marion Zimmer Bradley’s “Darkover” novels and another to Stephen R. Donaldson’s Thomas Covenant tales . Those lively discussions comparing and contrasting approaches were important, too.

Ken – who is a chemist at Los Alamos National Labs – unsurprisingly began his journey as a reader of “hard” SF. However, anyone who knows his lively personality will be unsurprised to find out that he appreciated Fantasy as well and remains an avid reader of both.

The book I mentioned as having a huge impact on me was Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land. This was given to me when I was fifteen by a law school classmate of my mom’s. I already read SF/F and had even read Heinlein. (Space Cadet was a lot of fun.) However, Stranger exposed me to so many things I’d never really thought about before – and no, it wasn’t just the group marriage concept, although I’ll admit that was rather mind-blowing to a student at an all-girl’s Catholic high school.

I was fascinated by the concept of the Fair Witness, trained to report precisely what occurred, without all the unconscious editorial information we usually add to our descriptions. Since I had grown up in Washington, D.C., I’d seen a lot of statues, but it was Jubal Harshaw’s comment “’Statues’ are dead politicians. This is ‘sculpture.’” that made me see the difference between the categories of sculpture and statuary. And I loved the behind-the-scenes political maneuvering, something that helped make sense of cryptic comments I’d heard all my life as my parents and their friends discussed politics.

I could go on just about this one book, but I thought it would be fun to ask some friends about the books that made a difference for them. Since Jim was sitting across from me in our office, I started with him. He couldn’t narrow it down to one book and finally settled on “Reading a lot of Andre Norton in seventh grade and thereafter opened my mind to what the future might be, both technologically and socially.”

John Maddox Roberts (author of both SF/F and mystery fiction) told this wonderful tale: “September 1959, 1st day of 7th grade, South Junior High School, Kalamazoo, MI. I was already a reader, and went to check out the new school’s library. Went in the door, turned left, found myself in the fiction section. Came to the H’s and found an intriguing title: Space Cadet. Checked it out, along with another: Red Planet. Read them both that night, came back the next day and checked out the rest by the author whose name I couldn’t pronounce yet. I was hooked. Proceeded to the N’s and read all the Andre Norton books. 12 years old, the golden age of SF.

“In the years since, I’ve often wondered how my life might have been different if I’d turned right that day.”

Sally Gwylan (author of A Wind Out of Cannan) was already a devoted SF/F reader (the Oz books, Red Planet, A Wrinkle in Time were all favorites) when she read Ursula LeGuin’s A Wizard of Earthsea: “The book that changed my life.” She says, “That book told me to turn around and face what you fear and made it believable. LeGuin made it clear that there would be a high price. That book led to me getting out of an abusive home.”

Suzy McKee Charnas (author of many SF/F novels) had a fascinatingly diverse list: “Gunner Cade (don’t know who wrote it)[collaboration between C.M. Kornbluth and Judith Merrill; thank you Gardner Dozois], More Than Human (Sturgeon), Earth Abides (Stewart), Judgment Night (Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore), and Against the Fall of Night (Clarke, also titled The City and the Stars). But it all started, for me, with an illustrated edition of Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island that we had in the house.”

She went on to say: “Gunner Cade sticks as a clear, uncluttered example of the basic SF plot of the naive young man completely integrated into his authoritarian society’s soldier class (or other take-orders stratum) who, unfairly ejected from his familiar environment by the plot, is nabbed by ‘the resistance’ under whose aegis the scales fall from his eyes, and he ends up leading the violent overthrow of the wicked ruling regime. It was and is *everywhere* in SF – I just picked up a forthcoming first novel called Red Rising, and there it is again, only nowadays it apparently takes three volumes to cover the same ground that flew by so satisfyingly in the form of one skinny paperback. Come to think of it, when I used it myself, in Walk to the End of the World, that was a skinny paperback, too.”

Steve Gould (SF author and current president of SFWA) contributed a nice, juicy list: “First sip was The Runaway Robot by Lester del Rey. Then, out of sequence, I found my grandfather’s copy of The Gods of Mars, followed by Warlord of Mars. Didn’t read Princess of Mars for another five years. Time Traders by Andre Norton. Think my first Heinlein juvenile was Red Planet but once I found that I rolled through them all in time to hit Starship Troopers when it came out and then Stranger [in a Strange Land].”

Laura Mixon-Gould (who also writes as M.J. Locke) had a somewhat different selection: I had a summer of discovery when I was 11. Clifford D. Simak’s Ring Around the Sun and Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time were the first two that did it for me, followed by Asimov’s I, Robot, then Burroughs’s ‘Mars’ books, followed by C.L. Moore’s ‘Jirel of Joiry’ stories, Jack Vance’s stuff, and, of course, the Heinlein juveniles.”

Editor Ellen Datlow had an interesting list, especially for someone who would become an award-winning editor of horror: “Eleanor Cameron’s Mushroom Planet books when very young, then Bradbury short stories, Dangerous Visions, and much later (college-independent study course) some novels like Dune, The Left Hand of Darkness, Slan, The Humanoids, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Creatures of Light and Darkness.”

Another editor, Gardner Dozois, weighed in with a long list that covered his later high school reading as well: “… my first taste of Sword & Sorcery came in De Camp’s Swords and Sorcery, and also in Dan Benson’s Unknown. De Camp’s The Incomplete Enchanter and Castle of Iron were important to me, as were his historical novels The Bronze Gods of Rhodes and An Elephant for Aristotle. The Heinlein “juveniles,” of course. (I actually hit the Andre Norton juveniles first, but soon decided the Heinleins were better, and moved on. ) Hal Clement’s Cycle of Fire and Mission of Gravity. James Schmidt’s Agent of Vega and Van Vogt’s The War Against the Rull. A bit later on, the stories in Cordwainer Smith’s Space Lords blew my mind, as did Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination and Fritz Leiber’s The Big Time. Jack Vance’s The Star Kings and The Killing Time. Delany’s The Towers of Toron trilogy, little read these days… I’d read The Hobbit years before I ran into the pirated Ace edition of The Fellowship of the Rings, but when I did, it had a major impact on me. Le Guin’s early novels, Avram Davidson’s Rork and Masters of the Maze.

“First book that made a big impact on me might have been Kipling’s The Jungle Books. At about that age, I gobbled up Burroughs’s Tarzan books too, although I didn’t read his Martian stuff until much later.”

George R.R. Martin (author of SF/F and Horror) weighed in with a diverse list:

“Heinlein’s Have Spacesuit Will Travel introduced me to SF.

“A couple of anthologies did the same for fantasy and horror – Swords and Sorcery, edited by L. Sprague de Camp, and Boris Karloff’s Favorite Horror Stories, edited (allegedly) by Boris Karloff. The former was my first taste of Conan and REH [Robert E. Howard], the latter my first taste of HPL [H. P. Lovecraft].

“And then, of course, Lord of the Rings.

“I also read a lot of Andre Norton and/or Andrew North in the early days. Star Guard, Star Man’s Son, Plague Ship were particular favorites.”

Pennsylvania area fan David Axler shaped his comment to make an interesting point: “Pre-teen stuff for me included the original Tom Swift books (the Boys’ Club in Binghamton NY had a full set in its library, along with a pile of first-edition Burroughs ((which must be worth a fortune now if they’re still around) and an odd mix of other stuff published mostly before WW2)), the Mushroom Planet series that Ellen mentioned, the Winston juvenile series (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winston_Science_Fiction), and a bunch of Verne and Wells. Andre Norton, of course, as well as Madeleine L’Engle’s Wrinkle in Time and its successors.

“I think it might be just as important to note the best book SOURCES from my childhood, because availability played such an important part in the amount of sf/f I read.

“My family moved from Binghamton to the Philly suburbs in ’58, and into the city proper two years later. The Philadelphia school system at that time was a big supporter of the Scholastic Book Clubs, and a fair chunk of my allowance went into sf/f they made available.

“That was also a time when the Philadelphia public schools had both libraries and librarians, and many of the latter made sure that their fiction sections included a fair amount of sf/f.

“I also have to give immense credit to the Philadelphia Free Library, which sponsored a Vacation Reading Club that was a big part of my summer reading experiences.

“Through the latter, I encountered a lot of the ‘classic’ anthologies from the 40′s, 50′s, and early 60s, which led to a major expansion of my overall reading list — any time I liked a story, I wrote down the author’s name so I could look for more on my next visit to the library.”

My query received many shorter replies as well, as well as many that duplicated the above lists. Robert Heinlein and Andre Norton won as “gateway authors” – which may reflect the generation of my research pool, as well as these authors’ undoubted popularity. However, what was wonderful was how diverse a selection of authors were represented. Edward Eager, T.H. White, Edgar Pangborn, and Ray Bradbury were just a few.

So what are your special books? Where did you find them? Did programs like Scholastic Book Clubs have an impact? (They did for me!) Was there a person who handed you a special book?

August 1, 2013

TT: All the News?

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Page back one and hear a bit about Treecat Wars, my forthcoming novel with David Weber. Then come and hear about how the earth shook for Alan — and we had no idea what was going on.

JANE: You know, Alan, if I didn’t correspond regularly with you, I’d have had no idea that starting in mid-July your part of New Zealand was absolutely bombarded with earthquakes.

News Selections

ALAN: Yes – there was a swarm of small quakes on the 19th. Many of them were too small to be felt, but some of them were quite large and noticeable. It culminated on the 21st with a very shallow earthquake, magnitude 6.5 on the Richter scale. Because it was so shallow and so strong, it really shook everything up and it was very, very scary.

Since then there have been more than 2,000 aftershocks and they are still going on. Again, they are mostly low intensity and can’t be felt. But we are told by the experts that there is a 10% chance of another 6.5 or greater quake over the next week. The last time this happened was in the early 1950s and the aftershocks then lasted for a month or so.

JANE: Dear lord! That’s scary. Talk about waiting for the earth to drop out from under your feet. How did the quake of the 21st effect your area? Was your home hit?

ALAN: After the big one on the 21st, the central city was covered in glass from broken windows and several buildings have suffered damage. The CBD was closed for 24 hours. All train services were cancelled while the tracks were inspected for damage (fortunately there wasn’t any and normal service was resumed the next day). The airport was closed for several hours while the runways were inspected and navigational instruments checked. The runways were fine, but some of the navigational aids had to be run from backup equipment for a time. In retrospect we got off lightly – but there may be more to come…

My house is built on solid rock which absorbs a lot of the energy, so it didn’t suffer any real damage, though a loose knob on the garage door fell off and has now completely disappeared!

My cats slept through it all and didn’t notice a thing. So much for the theory that animals can give you early warnings of these things!

JANE: Perhaps Harpo and Bess were more psychic than even cats are credited with being and they knew your house was safe and there was no reason to worry.

Now, I’ll admit, especially since I let my newspaper subscription lapse for various reasons, I’m not the best informed person. Jim, however, regularly checks the news on-line and listens to news radio. On the day my e-mail from you informed me that the quakes which had started the Friday before were still on-going and had gotten worse, the banner headline was that Princess Kate had gone into labor.

Jim later checked around and found on the “international news” page the New Zealand quakes were mentioned far down the list. However, the birth of said baby – also an international event – was, once again, banner news. I’m so embarrassed at how our “news” has become both parochial and superficial.

ALAN: Oh you’re not alone in your parochialism. Australia is just the same, if not worse. If your only source of news was the Australian papers, you could easily be forgiven for not knowing that countries other than Australia even existed! New Zealand also has its moments – way back around about 1981, the Israelis bombed an Iraqi nuclear power plant. There much concern at the time that this could lead to all-out war. On that day, the headline on the front page of one of New Zealand’s largest newspapers was: “Young Man Dies From Rugby Injury.”

JANE: Wow… Of course these were the days when newspapers were both paper and assumed to contain news. Now this no longer seems to be the case. This is one reason why I stopped getting a print subscription – this despite the fact that the newspaper I was getting was The Wall Street Journal, a paper with a very good reputation and one that I had been a regular reader of for many decades.

ALAN: Why did you stop your subscription?

JANE: The price for a subscription jumped massively and, despite my being a long-time subscriber, they wouldn’t give me a break. I let the subscription lapse. Now, about every four months, I get those bargain offers. However, I have resisted being seduced. Not only did I realize that without a newspaper I suddenly I had more time to read fiction and non-fiction both, I found I wasn’t missing much.

ALAN: And I’d agree with you. I’m a bit of a news junky and I need my daily fix. But even in those pre-internet days, I didn’t get much of my news from the papers. I depended far more on radio and TV. The BBC World service was, and continues to be, a superb source of news and later, of course, it migrated from radio to television along with organisations such as CNN and Al Jazeera. And they are all much better at reporting on world affairs than newspapers are. I remember that when Mikhail Gorbachev was briefly under arrest after the communist hardliners mounted what proved to be an abortive coup against him, he commented that he had kept himself informed about what was happening by listening to the BBC World Service news broadcasts. I think that speaks for itself.

JANE: Absolutely. I agree that for current events some web-based service is the way to go. That’s why I was appalled that – on the service Jim currently uses – a woman going into labor was considered more important than a series of major earthquakes. I think that if local newspapers are to survive, they need to become “parochial” – focus on their immediate community and provide thoughtful coverage of the issues. They can no longer hope to “scoop” a major event.

ALAN: We actually have community newspapers that do exactly that. They only report on local activities and leave the big picture to the bigger papers. But, as you rightly say, the big papers are becoming largely irrelevant these days.

JANE: Clear as mud… but our local newspaper can’t seem to figure this out. We live in a state that relies heavily on art tourism, yet the Art section of the Sunday paper gets thinner and thinner. Given the number of high profile local authors (some of whom are quite famous), they could do a weekly interview and rarely repeat themselves. If they added in visual artists, people working in film, and all the rest, they’d have ample. And that’s just one area… Ah, well.

ALAN: Earlier on you said that when you stopped reading The Wall Street Journal you found that you weren’t “missing much”. What did you mean by that?

JANE: As soon as I wasn’t reading daily news, I came to see how much that passed for news was really speculation. When The Wall Street Journal changed hands, many people were disturbed. I, however, found that undeclared competition with The New York Times meant that there was a lot more coverage of “my” field – various branches of the arts. However, I soon saw how much of the “this is what will be hot this year” was just guessing. And I began to wonder how much that was true in areas where I was less aware of the trends.

Do you take a newspaper?

ALAN: I’ve never subscribed to a newspaper – I just used to buy them as and when I felt the urge. These days I seldom read them at all. But in the days when I did read newspapers I read the “serious” papers such as The Times and the Guardian. I was particularly fond of the Guardian because it was (and is) a left wing paper whose editorial style appealed to my socialist tendencies. It was also a lot of fun. Colloquially the paper was known as the “Grauniad” because it was notorious for having spelling mistakes in its articles and the apocryphal story was that it couldn’t even spell its own name. It did once publish a review of the opera “Doris Gudunov”…

JANE: Alas, poor Boris…

You mentioned being a news junkie. How much news do you want?

ALAN: Personally, I want lots. The more the better, though I suspect that information fatigue might set in after a while. We have too many news sources these days and so we get overloaded. And the paranoid among us might say that makes it too easy for conspiracies to slip by unnoticed.

JANE: I see… I’ve seen information fatigue in several of my friends. They always seem anxious, sputtering about some perceived crisis that a month later they don’t seem to care about. I know this because I’ve asked “so what about such and such that we were talking about a couple weeks ago?” and been given a blank look. At the best, I’m sure these people are living more informed and sophisticated lives than I am, but often they seem like teenyboppers who, rather than obsessing over the latest trend or hot band, are obsessing over news items.

Would you consider yourself a typical New Zealander?

ALAN: No I think I’m quite untypical. Most people here are interested in local news (generally sport and politics in that order) and there’s a mild interest in what’s happening in our own back yard so news from Australia and the Pacific islands is also well reported. But apart from really important things like wars and catastrophes, I suspect many people don’t pay much attention to the rest of the world.

JANE: Well, as Jim’s experience showed us, you can want to pay attention to the rest of the world, but sometimes that’s not as easy as it should be.

We’ll keep watching the news and hoping that New Zealand is safe from any other earthquakes. Stay in touch! If we don’t hear from you, given what we’ve learned about our news coverage, we’re likely to assume the worst.

July 31, 2013

One Step Closer: Treecat Wars

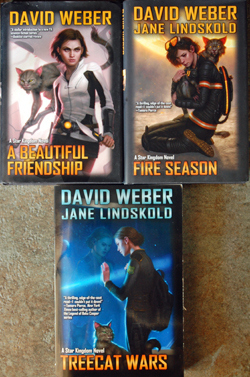

This Saturday, the postman came to the door with a big, fat package. Inside were advanced review copies of Treecat Wars, my latest collaboration with David Weber.

The Star Kingdom Novels

I’d seen a jpeg of the cover art, but I’ll admit I liked it even more when I held the book in my hot little hands and looked at it without the intermediary of a computer screen. It didn’t hurt that the dominant color is one of my favorite shades of blue. I’m getting really tired of cover art – especially for YA fiction – in shades of sepia.

I also liked how Daniel Dos Santos added depth and interest to the piece by his clever use of reflections. The young lady on the cover is Stephanie Harrington, looking down at the planet she is leaving behind. Her treecat companion, Lionheart (aka Climbs Quickly), looks amazingly serene given that he is the first of his kind to travel by spaceship, but that reaction makes sense given that his link with Stephanie would reassure him that, however peculiar this journey will be, it’s within the range of what she thinks of as “normal.”

This is probably the least dynamic of the three covers in the series. I admit a sneaking fondness for the cover of A Beautiful Friendship. Stephanie looks very fierce with her drawn vibroblade. Indeed, in attitude (not appearance), she looks much as I envisioned the young Firekeeper in my “Wolf Books.”

I like the cover of Fire Season, too. The ash greys and burnt oranges in the color scheme really catch the feeling of the forest fires that dominate the action. Then, too, I was pleased that Jessica Pherris, one of the characters I created for the series, was featured. Her anguish and protectiveness for the alien she holds cradled in her arms is eloquent in her posture. Close by, Climbs Quickly stands watch, his green eyes transformed to orange by the raging flames surrounding them.

Let me reassure you that, despite the apparent tranquility of the cover, Treecat Wars is anything but a tranquil tale. The aftermath of the forest fires have created problems for the treecats, problems that may only be solved by war – a particularly horrible alternative for a race that is not only telepathic, but tele-emphatic as well. Even more than in Fire Season, this story takes the reader into the culture of the treecats. Far too often, “first contact” stories focus mostly on the reactions of humans encountering aliens. Even in most of the Honorverse novels, the treecat point of view has been represented by treecats who know – and almost always like – humans. To Keen Eyes, humans are an unpredictable factor and one whose spreading presence may lead to the destruction of his fire-battered clan.

Interpersonal relationships take a big jump in Treecat Wars as well. Stephanie’s chance to leave Sphinx to study on Manticore forces her and Anders to take an honest look at what it means to be in love with someone who lives on another planet. Stephanie’s absence pushes Jessica into the role of liaison with a new group of xenoanthropologists…

Ah… But I’ll stop here. Treecat Wars hard cover release date is October of 2013. Those of you who can’t wait – and have e-readers – can check out the Baen Books website for e-book options. The countdown to launch is underway!

July 25, 2013

TT: Even More Buffy Fic

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back to where I discuss the values of Reverse Outlining. Then join me and Alan as we continue our examination of the latest variation on urban fantasy.

Buffy Fic — and influence?

JANE: Okay, Alan. I know you have another Buffy Fic author you’re eager to talk about. (For those of you who weren’t with us last week, take a quick look at last week’s Tangent if you want to know exactly how we define “Buffy Fic.”) Come to think of it, I have a couple to mention, too!

ALAN: I think Buffy Fic really came into its own for me with Charlaine Harris’s Sookie Stackhouse novels. I’ve admired her work for a long time. She’s a very prolific writer in a lot of genres, but these novels are the ones that brought her fame and fortune.

JANE: I fear I haven’t read the books, so I can’t respond except to say that you’re not the only one who seems to have enjoyed them. I sat next to Ms. Harris at a World Fantasy mass signing just as her star was rising and got to listen to her readers gush. What made the Sookie Stackhouse novels work for you?

ALAN: Sookie was a very appealing character – I admired her feistiness – and the premise that there are vampires among us was introduced very well with, initially at least, a very sympathetic vampire character. However, you can have too much of a good thing. The early novels are engrossing but, as the series progressed, I found myself becoming quite disenchanted with it.

One of the strengths of urban fantasy is the contrast between the mundane world and the magic world and the influences creatures of faerie have on the way that our world works. The Sookie Stackhouse novels certainly started out like that but, as the series progressed, more and more supernatural entities were introduced (werewolves and the like) and the stories moved away from their contemporary setting and turned into dull and unconvincing discourses on vampire politics and the like. In my opinion, she over-salted her stew. We got less and less reality and more and more fantasy, and I lost patience with it. I suspect she might have realised this herself because she recently announced that her next novel will be the last in the series; a decision I applaud.

JANE: Yes, I agree that focusing on the politics of the hidden world, rather than our world with supernatural world revealed (as in de Lint, Bull, Windling etc.), can lead to a sense of a world completely cut off from our own.

In my Changer, for example, there are hidden politics, yes, but they’re tied to the real world. One plot thread deals with sasquatches and fauns wanting to have some say in environmental policy and resenting that the “humanform” supernaturals want the non-humanform kept hidden because if humanity learns that monsters are real…

ALAN: Well, it seems that we agree about structures that work and structures that don’t. Do you have any authors who you think have managed to do this kind of thing convincingly?

JANE: Well, let’s see. Jim got me to read the first couple novels in was Andrew Fox’s “FatWhiteVampire” series. (The first book is Fat White Vampire Blues.) They’re set in New Orleans and the gimmick is that this time the person turned isn’t cool, handsome, or even particularly socially ept. In fact, Jules Duchon is a loser. Being turned into a vampire doesn’t make him any better. The only bright idea he has is that now he can be a superhero. The books have some clever touches – including the contrast with Anne Rice’s elegantly vampire-haunted New Orleans and the fact that Jules has not lost his taste for New Orlean’s style cooking. When he drinks someone’s blood, he seeks traces of the food he loves and will never again be able to eat.

ALAN: I’ve not heard of them before. They sound like enormous fun – obviously I need to add them to my reading list.

JANE: Moving back to Buffy Fic, something that concerns me about this particular variation on urban fantasy is that, in addition to the disconnect from our own world, there is a certain formulaic nature. I’ve come across more than one series that starts with vampires, moves to vampires and werewolves, then includes mages, then includes the fairy folk (often in a “fey light” mode), then moves to include ghosts.

I can’t help but be reminded of the sequencing of a certain series of gaming books put out by White Wolf in the 1980’s: Vampire the Masquerade, Werewolf the Apocalypse, etc. There seems to be a lack of imagination here.

ALAN: Indeed so – it’s all too easy to fall into cliché when imagination fails and I suspect that’s what we’re seeing here.

JANE: When I tried Jim Butcher’s wildly popular “Harry Dresden” series, part of what turned me off was the sense of that I’d seen this all before. Another was that Harry seemed too dumb to have survived to this point in his life. Have you read any of these novels?

ALAN: Oh goodness me! You are so right, they are completely unreadable! Harry is such a moron. I just want to reach into the page and shake some sense into him. I gave up after about three books. I couldn’t stand his stupidity any more

JANE: You got further than I did – and this despite the fact that there were times Butcher really impressed me with his descriptive ability. Unlike many of the “follow the trend” writers of Buffy Fic, he has skill. I just couldn’t find myself caring about what he chose to do with it.

A variation you sometimes get in Buffy Fic, is angels and demons in addition to all the movie monsters. I’ve also found this presented as a separate subset, where demons replace vampires and angels take the roll of the fairy folk. It’s as if, instead of the basic inspiration being movie monsters (since most of the vampires etc. owe more to film than to folklore), it’s a watered-downed Judeo-Christian myth.

ALAN: Well, we’re all familiar, to some extent, with the Judeo-Christian myths so there’s absolutely no reason why they can’t form the basis of novels like these. Indeed, there’s a New Zealand writer who makes a very successful living out of writing exactly these kinds of books. Her name is Nalini Singh (she’s of Indian descent). I’ve met her several times and spoken to her about her books. For a long time she just wrote straight romance novels – the Mills and Boon kind of thing.

JANE: Alan? What’s a Mills and Boon?

ALAN: Aha! We’ve stumbled over another one of those cultural differences that caused us to start writing these tangents in the first place! Let me go off on yet another brief tangent…

Mills and Boon are British publishers of romantic fiction. I think they are similar to Harlequin in America. Because they only publish romance their name has become synonymous with romance, and British people tend to talk about Mills and Boon books rather than romance books. Mills and Boon publish a huge number of novels and they have a huge stable of writers, all of whom have female names. I use that phrase advisedly – I know someone who writes for Mills and Boon as a hobby. He is about six feet tall and six feet broad with enormous muscles. In his day job, he is a policeman. Nevertheless, as far as his readers are concerned, he is a delicate female with a very romantic view of the world…

JANE: Lovely! I hope he carries this over into his personal life. His partner would be very lucky indeed.

ALAN: Meanwhile, back to Nalini Singh – she found that she couldn’t make a living by writing just pure romance.

Then one day she had a brainwave; why not combine a romance novel with a fantasy plot? And she’s never looked back. She’s a regular on the New York Times Bestseller lists and she makes quite a comfortable living from her writing.

She has two major series on the go: “Psy-Changeling” (which is vaguely science fictional) and the “Guild Hunter” series which is the kind of thing we’ve just been discussing: stories that are full of sexy angels, archangels and the like. The stories get quite raunchy at times as well, which is an added bonus!

They’re not really my cup of tea (I’m not all that fond of romance as a genre), but I’ve read several of Nalini’s books and there’s no question about it, they are beautifully written page turners. She’s a skilful writer and, if you like that kind of thing, I promise you won’t be disappointed.

JANE: A similar but different take on the use of Judeo Christian tropes in Buffy Fic are Darynda Jones’ “Charley Davidson” books. (The first book is First Grave on the Right.)

Charlie is the Grim Reaper – what this means is defined in the series and it’s too complex to go into here. Her mundane life is as a private investigator – a profession in which it can be very useful to be able to talk to people who have died but have unfinished business.

The books are light and breezy, full of sexual allusions and the occasional hot sex scene. There’s an on-going romance, too, although a very odd one. Charlie is a likeable character, who genuinely cares about the people – living and dead – with whom her life becomes intertwined. I save the books for times when I want a light read that isn’t shallow. That’s often hard to find.

And, as a plus, no vampires!

ALAN: Big plus!

JANE: I’m sure our readers will want to fill us in on the good Buffy Fic we’ve missed. I hope they’ll feel invited to do so!

July 24, 2013

Reverse Outlining

Not much rain since last time. Lots of veggies. (I’ve picked at least ten ichiban eggplant, about a gallon of string beans, and three monster zucchini since Monday. Oh, and another mystery squash and a few tomatoes.) And this week’s writing task is…

Reverse Outline: Treecat Wars

Reverse outlining the 30,000 plus word manuscript I have of “Artemis Awakening 2.”

Reverse outlining? What are you talking about? And, hey, wait! Aren’t you always saying you don’t outline your novels?

You’re right. I do say that and I hold to it. I don’t outline a novel before writing it – which is what most people mean when they talk about outlining – but I do outline as I write. Often I start when I have a chapter or two in place. This time the novel took fire so quickly that, until I was interrupted by the need to do the page proofs for Treecat Wars, I neglected this essential step.

Why would you bother to outline what you’ve already written? I mean, isn’t it wasted effort? Don’t you have the manuscript there in front of you?

I do have it and, no, it’s not wasted effort. In fact, I find reverse outlining the absolutely best way for me to keep track of my plot, characters, and the general flow of the action in an evolving novel. So, how does reverse outlining work?

First, I pull out a sheaf of nice, white lined paper. Yes. I could do this on a computer, but I’m one of those people who remember things better if I write them down by hand. Since part of the goal of a reverse outline is to serve as an aid to memory, I write mine by hand.

Next, I pull out a sheaf of brightly colored pens. I assign one color to each point of view character and another to be used for chapter headings. I also pull out a pencil. The last preparatory step is to pull the manuscript file up on my computer screen.

Since my reverse outline isn’t for anyone except me, I don’t worry about writing down everything that happens in a particular section. I focus in on events that will jog my memory when questions crop up like “When exactly did they arrive in Spirit Bay?” or “When did that mugging happen?” or “How many days have elapsed since….”

In the side margin I use the pencil to note what day a given event happened. I use pencil because sometimes dates shift, especially if I end up going and adding something later on. If the book has a precise starting date, I use that. Otherwise, I simply label each day as Day One, Day Two, etc. Later on, I can always add a notation as to calendar date, if that will be important. I also make notations as to season since time of year can affect anything from length of days to temperature. I also note the phase of the moon if that will be important.

What do I do if the action skips ahead several days? I make a note of that as well. More importantly, I note why those days were skipped. Maybe there was uneventful travel or maybe time needed to heal from a wound or maybe the characters were waiting for some information. Especially in the case of travel time, these details can come in really useful, making sure that journeys between points take about the same amount of time.

I recently finished reading a fantasy novel in which I never could feel the terrain was at all real since travel time between points seemed to shift according to the needs of the plot. Most of the time, the characters seemed to slog along, step by step. However, when the climax required a last minute arrival of the Good Guys, they showed up, a bit sweaty and all, but certainly faster than I could believe. It took some of the fun out of the climax for me to feel that there was a deus ex machina, when the plot was going out of its way to eliminate deus or machina.

Yes, I do realize that, especially when a book is set in a low tech setting, travel times can vary widely. If so, why not make a note of the reason? You don’t need to write that long slog through the snow unless that slog is important, but you can note that getting from point A to point B took longer (or shorter) because of weather conditions.

But reverse outlining is useful for more than just consistent geography. It can help with characterization, too. Characters can marvel that they’ve known each other only a few days, but feel bonded. Or, conversely, that they’ve been together for weeks but, after a short time, the friendship ceased to progress beyond initial introductions.

Why do I color code my point of view characters? (Well, beyond the fact that it gives me an excuse to play with colored pens, which I love?) I do this because it enables me to see at a glance whether the story has gotten out of balance. Certainly, there are times when one character has more to do than another. However, it is also true that a writer can become deeply drawn into one plot thread at the expense of another. If this isn’t deliberate, then some rebalancing is in order.

So, time to pull out the colored pens and get back to it…

July 18, 2013

TT: Modern Twist to Urban Fantasy

Looking for the Wednesday Wandering? Just page back one. Maybe you can tell me what’s growing in my garden. You’ll also learn why, no matter how busy I am, I never skip page proofs. Then come back and join me and Alan as we take a look at the newest evolution in urban fantasy: Buffy Fic!

Buffy Fic: It’s Not All Like This…

JANE: As we mentioned a few weeks ago, the term urban fantasy has recently expanded to incorporate what used to be the monsters of horror, presented in a less monstrous, often romantic, context. Since it seemed to me that this sort of urban fantasy blossomed forth as the Buffy the Vampire Slayer television series grew in popularity, I’ve tended to term it “Buffy Fic.”

ALAN: And that’s a name that seemed so appropriate the first time I heard you use it, that I’ve been using it ever since. But “Buffy” was a TV show. I suspect that the huge popularity of Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight novels has also had a lot of influence on the growth of this kind of thing as a literary genre.

JANE: Now, I’ll admit, as a reader I have an aversion to fiction focused around vampires— although I have read all the “Twilight” books, mostly so I could find out what the fuss was about. Anyhow, to me, it doesn’t matter if the vampires are the good guys or the villains or both. It’s just not my flavor. Therefore, I’m hardly an expert on this particular variation of urban fantasy. Perhaps you could mention some authors or titles you have enjoyed.

ALAN: I rather like vampires. Can I tangent off our tangent for a moment so that I can talk about vampires?

JANE: Go for it… I’m always hoping to figure out what possible appeal vampires could have.

ALAN: The archetypal example of the genre would be Anne Rice’s work – Interview With The Vampire et al, but I must confess I always found them rather turgid.

JANE: Whoa! I remember when Anne Rice’s work was omnipresent. Wasn’t it considered horror?

ALAN: I think that’s the slot that many readers and reviewers put it in, but I was never completely convinced. Anne Rice always presented the vampire Lestat in a very romantic light. He was handsome and sexy as well as dangerous. I’m sure you could make a very good case that Buffy Fic draws at least as much inspiration from Anne Rice’s work as it does from anything else. After all, the prevailing characteristic of Buffy Fic is that feeling of slightly dangerous romance.

JANE: I really think that one of the biggest differences between Buffy Fic and Horror is that in Buffy Fic romance is crucial. It also lacks the “darkness” that prominent horror editor, Ellen Datlow, mentioned is key.

It’s worth re-quoting her: “To me, horror is less a distinct genre than a tone that develops from the approach writers take to their material. It’s the darkness, always the darkness that prevails. Even when the protagonist survives, the darkness is never left entirely behind. Things are not ‘ok’ in the world (which is why most of what is today called ‘urban fantasy’ is not horror).”

ALAN: That’s quite true.

But, sticking just to vampires for the moment, I’ve greatly enjoyed Mike Resnick’s approach in Stalking The Vampire which is a sort of hard-boiled private detective novel with vampires and jokes. He’s written several books in this series and they are all a lot of light-hearted fun, played strictly for laughs.

Christopher Moore has also written a trilogy of vampire novels which I think are some of the funniest books I’ve ever read – I was literally crying with laughter when I was reading them. The novels are: Blood Sucking Fiends, You Suck and Bite Me. I think the puns are obvious…

Then there’s Kim Newman and his Anno Dracula series. The premise here is that Dracula triumphed over his enemies – Jonathan Harker and Van Helsing were soundly defeated. Dracula wooed, won and married Queen Victoria, as a result of which vampirism became very fashionable and it wasn’t long before everybody who was anybody at all in high society was turned into a vampire…

Newman’s stories are not precisely played for laughs; there’s a grim subtext. But nevertheless there is a lightness of tone which makes them really rather a lot of fun.

Books like these straddle the line between horror and Buffy Fic.

And, to be more serious for a moment, Octavia Butler’s last novel Fledgling uses the vampire as a metaphor for the outsider and her novel, while it’s a brilliant straightforward vampire story on the surface, is also an examination of racial and sexual prejudice underneath the surface. Vampires definitely have their literary uses!

JANE: Well… Let’s just say that I don’t feel any desire to add these to my reading list.

You know, you still really haven’t given an example of Buffy Fic… How about one?

ALAN: OK – back to Buffy Fic. I’ve really enjoyed the Rachel Morgan novels by Kim Harrison. The premise is that most of the human race has been destroyed in a world wide pandemic caused by genetically modified tomatoes and now the supernatural entities (who weren’t affected by the pandemic) can slot themselves neatly into the organisational structure of society. There’s still an uneasy relationship between the humans and the supernaturals but nevertheless there is a relationship.

Rachel Morgan herself is a witch and a detective. Her cases involve both the mundane and the supernatural and much of the strength of the series comes from the impact of her relationships, both romantic and otherwise, with her clients and partners. The titles of the novels are wonderfully clever puns on Hollywood movies – for example Dead Witch Walking, and The Good, the Bad, and the Undead.

JANE: Oh! I’m giggling madly! Genetically modified tomatoes? Funny! But, actually, it’s also a nice reference to the rising fear of genetically engineered crops.

Now It’s my turn.

My husband, Jim, is usually my gateway into any book with vampires. He really likes Carrie Vaughn’s “Kitty” books. Kitty is a radio talk show host who is assaulted by a werewolf and becomes one herself. Initially, she is a very convincing wreck. However, she finds her strength in becoming a voice for the voiceless. I’ve only read a few of the books, but I’ve liked what I’ve read. Jim is positively hooked.

One thing that makes the Kitty books work for me is that – although there is a fair dose of hidden politics – there are real world issues, too. Kitty’s mother gets breast cancer and Kitty needs to figure out how to visit her mother with dangerous enemies on her tail. In Kitty Goes to Washington, Kitty has to testify before Congress regarding the reality of supernatural entities.

Best if all, not all the vampires are powerbrokers. One of my favorite scenes is the one where a young man calls into Kitty’s show. He was “turned” and now the only work he can get is in a late night stop and shop. He’s not cool. He’s not powerful. And he’s trapped this way for all eternity. It’s a bit of nice balance.

ALAN: I’m not familiar with those books. Perhaps we should take a break here while both of us go and do some reading…

JANE: And I go do some writing! Spoiler warning for our readers… We’re not done yet! Hurry back next week for more of the best of Buffy Fic.

July 17, 2013

Fragments: Rain, Page Proofs, and Vegetables

We had rain this week. Sunday night was particularly memorable. We got over half an inch. Most of that fell within an hour. The rest drizzled down over the next few hours. Male and female rain, as I’ve been told our Navajo neighbors would term it. We just call it good weather.

Mystery Squash (about five inches, top to bottom)

Several times Sunday evening, Jim dashed out between the raindrop to check our fancy digital rain gauge (a very useful tool when most rainfall is under an inch), finally returning to announce triumphantly, “We just hit exactly half an inch!”

I may not have been born a “child of a rainless year” as was Mira, the protagonist of my novel of that name but, during the nineteen years I’ve lived in New Mexico, I’ve really come to appreciate rain. These last couple of years, when we’ve been in drought conditions, every rainfall is a reason for celebration.

Living here has really reversed how I see rainy days. “Back East” where I grew up, a rainy day mood meant feeling gloomy. Remember Joe Btfsplk, the character in the cartoon Li’l Abner, the one who had a raincloud hanging over his head all the time? No one needed to be told that he was perpetually down. The symbolism just doesn’t work here.

Soon after I moved to New Mexico, I read a newspaper column by Jim Belshaw in which he commented that New Mexico was the only place he’d ever lived where when it rained people just got up from their desks, stood by the window to watch it rain a while, and went back to work – and no one thought this at all strange.

When Jim and I went to ride our bikes on Monday morning after the big rain, the skies were still overcast, but everyone we passed was smiling broadly. “Great weather!” more than one person called out. “60% chance of more today!” someone shouted. Yeah… Live in the desert long enough and all your symbols get screwed up. It’s pretty fun, actually, since it makes you take a fresh look at all your preconceptions – never a bad thing for a writer.

Speaking of being a writer… The page proofs for Treecat Wars, my second collaboration with David Weber, came in on Saturday. Page proofs are the pages of the book set up pretty much as they’ll be printed. Reviewing proofs is the last stage in an author’s work on a book. I never skip proofs. Most of the time, everything is great, but there was the time I found that the first paragraph in every chapter of The Buried Pyramid had been left out. I’ve found some other weird errors. Most have crept in during production, usually the result of some odd keystroke globally changing the spelling of a word to some other word.

So, even in these days of computers – maybe especially in these days of computers – I don’t skip the proofs. Yeah, I’d rather be writing on the sequel to Artemis Awakening, (still AA2, though I’m trying out different titles), but duty calls. My plan is to do new writing in the morning and proofs in the afternoon. Plans rarely work out, but, hey, you gotta have a plan, right?

I’ve come to think that every writer should have a garden, because gardens are a wonderful reminder that planning only goes so far. After a slow start, our garden is taking off. Monday morning I picked nine small ichiban eggplant and a substantial zucchini. Jim picked about two cups of string beans. We had stir fry for dinner. I’m guessing we’ll have it again sometime around Thursday. But I can only guess… Zucchini, in particular, seem to go from “Nice, pick that in a few days” to “Holy cow!” faster than even a long-time gardener can predict.

Sunday we had a salad with our first tomato of the season as well as our own Swiss chard and radishes. Cucumbers are behind schedule – but since when have we been able to predict them? Some years they take over. Some, like this, they poke along.

And then there are the mystery squash. We couldn’t resist planting some squash seeds that came in fund raiser packet. The package showed a variety of types – both summer and winter – that I recognized. These don’t match any of the pictures. Jim has been taking photos in to his office and consulting both the ethnobotanist and various other colleagues. The best advice so far has been, “Hmm… Looks like a winter squash variety. Sometimes those are better when picked young, before the rind gets too hard. Why not just try one?”

So, we probably will…

It’s all very amusing. Life is like that. Rain to celebrate. Symbolism to contemplate. Jobs to do. Gardens to enjoy. Oh, yeah, and writing… Always and forever, writing. It’s what I do, and a large part of who I am.