Jeanne Reames's Blog, page 4

August 7, 2019

Alexander as LGBTQI Icon

“Was Alexander the Great gay?”

I get that question ALL the time. The poor horse has been beaten to death, and discussion always ends in an examination of Greek terminology that’s largely academic. I’ve written about it before elsewhere.

I’d like to look at this from a differentangle, here.

For decades (maybe centuries), Alexander has been an icon in the queer community. That upsets a portion of his fanbase, including some Greeks. When early publicity for Oliver Stone’s 2004 blockbuster hinted that Alexander had male lovers, a group of Greek lawyers threatened to sue him. Yet as in the rest of Europe, the younger generation cares less, and in 2015, Greece passed recognition of same-sex civil unions, even if they couldn’t quite make the leap to call it “marriage.” As a result, resistance to Alexander as gay, or at least bisexual, has lessened in Greece. Somewhat.

In the rest of the Western world, “Was Alexander gay?” has shifted for many to “Alexander was gay.” Question to statement.

How’d we get here? Indulge me in a tour of Alexander’s treatment in modern history and recent fiction.I’ll keep it as brief as possible, but stay for the payoff, ‘kay?

The earliest modern historians of Alexander (late 1800s) wouldn’t even talk about Alexander and men. Then, in the 1930s, W. W. Tarn wrote a “defense” of him from those naughty insinuations in his 2-book biography. It wasn’t very convincing unless you were inclined to be convinced. After, either silence or righteous indignation were the usual responses to the matter, and historians routinely ignored Hephaistion (his probable lover) in their work because it might bring up the homosexual thing.

The earliest modern historians of Alexander (late 1800s) wouldn’t even talk about Alexander and men. Then, in the 1930s, W. W. Tarn wrote a “defense” of him from those naughty insinuations in his 2-book biography. It wasn’t very convincing unless you were inclined to be convinced. After, either silence or righteous indignation were the usual responses to the matter, and historians routinely ignored Hephaistion (his probable lover) in their work because it might bring up the homosexual thing.Then, in 1958, Ernst Badian published, “The Eunuch Bagoas” in The Classical Quarterly, and the ground shook. Yes, his article influenced Mary Renault’s later Persian Boy, but it wasn’t a manifesto on Alexander’s same-sex partners. Badian sought to rehabilitate the ancient sources that Tarn had dismissed because they’d suggested that Bagoas was, you know, REAL. Hence the article title.

After, scholarship began to talk about Alexander and men. Yet a certain discomfort remained. Most ATG (Alexander the Great) historians of the time were cis white straight guys. If many (some of whom I know personally, so can vouch for) were also left-leaning agnostic/atheist liberals, people are products of their era. They might acknowledge that Alexander had male lovers, but thinking too closely about it was outside their comfort zone.*

In addition, this new generation coincided with the “Badian Revision” that attacked Alexander’s image as Romantic Hero or Gentleman Conqueror—fairly, to be honest. He committed some horrific acts. In any case, the then-current trend painted him (and his friends and supporters, including Hephaistion) with a hostile brush, independent of sexual orientation.

Well, maybe. Of them all, Hephaistion faired worst, and a lot of that assessment was colored by his emotional role in Alexander’s life.

About the same time, Mary Renault (herself bisexual) published Fire from Heaven (1969). We might characterize it as a toe in the water; she’s allusive about Alexander and Hephaistion there. But in 1972, she followed it with The Persian Boy, and threw down the damn gauntlet.

About the same time, Mary Renault (herself bisexual) published Fire from Heaven (1969). We might characterize it as a toe in the water; she’s allusive about Alexander and Hephaistion there. But in 1972, she followed it with The Persian Boy, and threw down the damn gauntlet.Oh, what a difference a riot can make! Hello, Stonewall.

I’ve noticed a tendency among some younger LGBTQI readers to pooh-pooh Renault for her “off the page” takes on Alexander and sex, or for her idealizing of Alexander, and I agree about the idealizing. But we must place her in her proper historical context. At the time, she was a lightning strike. Whatever I may think of her romanticism, I recognize her enormous impact, and salute her. You go, Grrrrl.

I collect ATG fiction for snorts and giggles, have for a long time. But with a couple exceptions where I was asked to review something, I’ve avoided reading any since 1998, in case it even accidentally influenced my own work. After Dancing with the Lion sold, however, I finally read what I hadn’t, then presented conclusions for an academic paper on Alexander and Hephaistion in fiction post-Stonewall (coinciding with the 50th Anniversary of the riot), presented at Emory in Atlanta for the 2019 annual meeting of the Association of Ancient Historians. I won’t detail the books I covered, but will share the PATTERNS I saw, and let you. Gentle Reader, draw conclusions.

First, and most importantly, allbut one novel presented Alexander and Hephaistion as lovers. If the presentations weren’t universally positive, it marked a sharp break with pre-Stonewall books.

In every novel wherein Alexander and Hephaistion’s love affair was positively portrayed, Hephaistion was also presented positively. Alexander may or may not have been. In every novel wherein Alexander and Hephaistion’s relationship (and homoeroticism) was negativized, Hephaistion was also negativized, and usually Alexander as well.

Yet several novels ticked “neither of the above.” In some, the relationship was problematized, usually for plot reasons; in others, the author sent mixed messages about homoeroticism (I think accidentally). Curiously, in most of these, Hephaistion was presented positively while Alexander was not. Finally, in the single novel where they were not lovers, Hephaistion was positive, but Greek homoerotic activity was ignored.

Take-away: authors who portray the relationship positively, have a positive Hephaistion. Authors who show it negatively make Hephaistion (and Alexander) morally iffy, at best. Otherwise, it’s a crap-shoot.

Here’s the kicker (and I bet you can guess what’s coming): the positive portrayals were all by women, plus one (British-Lebanese) man. Neutral portrayals might be a mixed bag, gender-wise. The negative ones? All guys. And the one where they weren’t lovers? A guy.

That, to me, sends a powerful message about who’s comfortable with the idea, regardless of whether an author publicly supports LGBTQI rights. Several of the negative ones were published before 2000, but others were recent-ish.

If the queer civil rights movement has made great strides in the 21st century, we’re experiencing a predictable cultural backlash. And in the current environment, I think it hugely important not just for LGBTQI people generally, but especially LGBTQI youth to be able to look at history and say, “Hey! Alexander the Great loved a man, and look what he accomplished!” I won’t go into, here, whether Alexander was “gay,” “bi,” or if we should even use modern terms; I’ll be happy to do that elsewhere over a beer.

Here, I want to say that, YES, dammit, it’s not only okay, but important for the LGBTQI community to claim Alexander. The fact the person he loved best in the world was another guy could keep some queer kid from suicide or self-harm, or even just give her/him/them a reason to get out of bed in the morning.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

* This has changed substantially in the past 20 years and it’s now inaccurate to assume ATG scholars are mostly male, white, or straight. At the last International Alexander Symposium (2018, Edmonton, AB), hosted by Frances Pownall, a substantial number of women scholars presented, at least a third. Furthermore, Frances is, together with Sabine Műller and Sulochana Asirvatham editing the proceeds: a 3-woman editorial team. Frances is also editing a festschrift for Elizabeth Carney (one of the most prominent female scholars on Alexander, Macedonia, and the Successors) along with two others, another of whom is female. And of course, Sulo is not only not male, she’s not white. This is the new face of Macedonian scholarship.

Published on August 07, 2019 20:15

August 4, 2019

Writing Fiction vs. Writing History

When I first announced that I had an historical fictionbook coming out, I got a lot of side-eye.

Not necessarily from my professional colleagues. Yeah, a few were (and remain) skeptical, but of historical fiction period, not necessarily mine.

It was largely everybody else. Could an academicspin a good yarn?

Well, we do it all the time. It’s called teaching, at least if one is any good at it. Not everybody is, of course. Also, what constitutes “a good yarn” can vary (just read reviews on Amazon).

Well, we do it all the time. It’s called teaching, at least if one is any good at it. Not everybody is, of course. Also, what constitutes “a good yarn” can vary (just read reviews on Amazon).That said, it’s a fair enough question.

First, I’ve been a writer longer than a professor. I’ve even published other things (not historical fiction). I’ve joked that most writers who take their craft seriously do conduct considerable research, they just don’t go on to get a degree in the subject. So it’s probably more fair to say I’m a writer who became an academic, rather than an academic who became a writer.

Second, to me, telling a story is all about the characters, and their emotions.

So Dancing with the Lion begins with a runaway boy who’s angry at the world because his favorite brother died, and another who fears he’ll never measure up as the son of the most powerful man in Greece. What happens when they meet? It’s also about those boys’ relationships with their fathers. And for Alexandros, with his mother and sisters. It’s a love story, yes, but also a story about family, and friendship. So it really IS a love story, not just a “falling in love” story. All kinds of love. And a little bit of hate, too, here and there.

It happens to be set in ancient Macedonia (a kingdom just north of Greece). While reading Dancing, I hope readers get the same sense they might being led around New York City by a native New Yorker. I want the place to feel PALPABLE. Real. Deep. This isn’t one of those, “See 7 cities in 6 days” tours.

Yet the story isn’t about Macedonia. The story is about Alexandros and Hephaistion growing up there. Some of what they experience are human universals: grief, first love, fear of failure. Some is a little more specific: going into battle for the first time, or dealing with brawling parents. Yet for me, the focus remains on how these characters cope with what they face.

For instance, and without giving too much of a spoiler, in one scene after Hephaistion has been hurt, Alexandros goes to the temple of Darron, the Macedonian god of medicine, in order to make a sacrifice for his friend. It’s not unlike going to the hospital chapel to pray for somebody in the ER. But I don’t walk readers through the steps of ancient Greek sacrifice. Nobody is there for my class on Greek religion. The scene is about Alexandros’s fear for his friend.

That’s why it’s a novel, not a history book.

(*And yes, those are my beaten-up Loebs of the 4 primary Alexander historians [minus Justin]. Once upon a time, they were all pretty and new. LOL.)

Published on August 04, 2019 18:15

August 1, 2019

Why is he Alexandros, not Alexander?

From the very beginning, I wanted to use Alexander’s real name. I did so for the same reasons I chose to write in his point-of-view in the first place, not in the heads of people all around him.

I want to make him real. “Alexander the Great” is a legend. Alexandros of Macedon, or really Makedon, was a living, breathing human being. That’s who I’m writing about.

Some readers may think it pretentious, or that I’m making all those weird Greek names harder. But again, I’m not writing about the legend, I’m writing about the boy. And the notion that “Alexander” is easier for English-speakers to say than “Alexandros” strikes me as naive. Same thing with Philip and Philippos. Now I might give you that Aristotle is easier than Aristoteles, but for the most part, the name thing affects a bare handful. If readers can handle Hephaistion and Erigyios (for which there are no alternatives), I think they can manage Aristoteles! I dislike underestimating or insulting my readers.

Some readers may think it pretentious, or that I’m making all those weird Greek names harder. But again, I’m not writing about the legend, I’m writing about the boy. And the notion that “Alexander” is easier for English-speakers to say than “Alexandros” strikes me as naive. Same thing with Philip and Philippos. Now I might give you that Aristotle is easier than Aristoteles, but for the most part, the name thing affects a bare handful. If readers can handle Hephaistion and Erigyios (for which there are no alternatives), I think they can manage Aristoteles! I dislike underestimating or insulting my readers.ALL these Greek names look strange to English-speakers, and a lot of folks will just gloss them. They’ll become the Eri-guy or Heph, or Leo (for Leonnatos). That’s okay.

My students love to make up nicknames in class for ancient figures, and if people think Greek names appear odd, try Suppiluliuma (a Hittite king). But so fun to say! I’d get my whole Ancient Near Eastern class to pronounce names together, at once, just so nobody felt stupid for having no clue how to say something that’s six syllables long. At first, they were a bit reluctant, but after the first few times, they really got into it. Suppiluliuma was dubbed “Soupy,” but I think the funniest was “Mega-bus” for Megabyzos, a Persian general.

I don’t want to make fun of people’s names, but teaching gives me a good idea of how readers are going to see these. While on the one hand, readers can certainly handle the real Greek, I fully expect a lot of readers will shorten them in their heads. I’m cool with that.

Yet if readers would like to hear the names, So if, like me, you love language and hearing the names, pop over to the website and take a listen. Otherwise, as you read, you can pronounce/remember those suckers however works best for you!

Published on August 01, 2019 20:12

July 25, 2019

The Love Story at the Heart of DANCING WITH THE LION

The nature of Alexander’s relationship with Hephaistion completely fascinates me.

Not whether they were lovers (for the novel, I've assumed that), but the honesty, duration, and sheer depth of it.

Alexander called Hephaistion “Alexander too,” and “Philalexandros”—friend of Alexander, in contrast to one of his other generals, Krateros, who he called only “Philobasileus”—friend of the king.

Alexander called Hephaistion “Alexander too,” and “Philalexandros”—friend of Alexander, in contrast to one of his other generals, Krateros, who he called only “Philobasileus”—friend of the king.Although it seems they did often agree on policy, his support wasn’t brown-nosing. We’re explicitly informed that Hephaistion would tell Alexander what he really thought. Nobody else was as free as he was to upbraid the king. Yet Alexander never seemed to have felt threatened by him.

They were true best friends.

How many rulers throughout history have had that? Someone who they utterly trusted? And for about nineteen years, too. Maybe even longer (we’re not sure when they met).

Who was this guy? What must he have been like, to become best friend to Alexander the Great? I’ve spent much of my career studying him, and I’m working on a biography about him now. But fiction lets me speculate in ways history doesn’t.

It seems to me that a lot of novelists who write about Alexander aren’t entirely sure what to do with Hephaistion. He winds up bland, or bitchy. It may also be why at least some historians have a hard time believing he deserved his commands. He had to have been a yes-man or Alexander wouldn’t have kept him so close. Or he’s painted as Richelieu-esque, called “sinister,” and described as “tall, handsome, spoilt, spiteful, overbearing, and fundamentally stupid.”

I’ve challenged these portrayals in my scholarship, but believe a goodly chunk of the problem is trying to imagine the sort of man who’d become “Alexander too,” without menacing the authority of such a dominant figure as Alexander. I think Hephaistion was a gamma male. Pop definitions can be found all over the net, but the term was born in anthropology to describe the (few) male bonobo chimps who simply didn’t play the game. While some pop definitions assume gamma males will always clash with alphas because of a gamma’s dislike of authority, that’s only partly true. For especially powerful and intelligent alpha males, gammas may be their onlytrue friends.

I’ve challenged these portrayals in my scholarship, but believe a goodly chunk of the problem is trying to imagine the sort of man who’d become “Alexander too,” without menacing the authority of such a dominant figure as Alexander. I think Hephaistion was a gamma male. Pop definitions can be found all over the net, but the term was born in anthropology to describe the (few) male bonobo chimps who simply didn’t play the game. While some pop definitions assume gamma males will always clash with alphas because of a gamma’s dislike of authority, that’s only partly true. For especially powerful and intelligent alpha males, gammas may be their onlytrue friends.I believe Alexander trusted Hephaistion because he was neither a follower nor a leader, and he could keep up with him intellectually, shared his visions and ideals. They had a mission together. All the best love affairs do. Far from bland or bitchy, Hephaistion must have been complex and formidable. And theirs is one of history’s most interesting love stories, even if we may not know a whole lot about how it came to be.

But that’s what fiction is for.

Published on July 25, 2019 16:38

July 22, 2019

When Your Chief Protagonist is *Really Famous*

I love coming-of-age stories, especially about people you know will go on to do amazing things.

Yet authors of historical fiction usually avoid making a famous person the chief protagonist. It’s likely to tick off readers if your vision doesn’t match theirs, especially if you go into the character’s head.

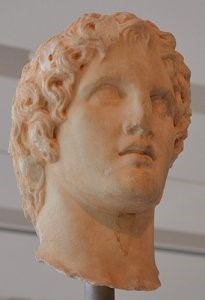

In my case, however, it’s precisely Alexander’s fame that led me to focus on him. He was enormously complex, the source of continued fascination throughout history, but everybody has a different Alexander. To some, he’s a hero, to others, he’s a monster. He’s also not really what one would expect in the man who’d go on to conquer most of his known world before he was 33: the fresh-faced kid with a “melting gaze” (so the ancient authors), who liked to present himself as a “philosopher in armor.” He’s a feisty bundle of contradictions.

In my case, however, it’s precisely Alexander’s fame that led me to focus on him. He was enormously complex, the source of continued fascination throughout history, but everybody has a different Alexander. To some, he’s a hero, to others, he’s a monster. He’s also not really what one would expect in the man who’d go on to conquer most of his known world before he was 33: the fresh-faced kid with a “melting gaze” (so the ancient authors), who liked to present himself as a “philosopher in armor.” He’s a feisty bundle of contradictions.But whatever people think about him, he seems larger than life.

Which is exactly why I wanted to write about him. I want to humanize him.

Alexander is the poster child for what happens when a famous father produces an even more famous son. We don’t hear about Philip of Macedon much today because Alexander sucked up all the air in the room. But when he was a boy, nobody knew what he’d become. He grew up in the fishbowl of palace life, son of “the greatest of the kings of Europe” (so Diodorus, an ancient author). What must that have been like? Supposedly, he used to complain to his friends that his father wasn’t leaving anything for him to accomplish. Even in his teen years, he had a hunger for glory. Today, we prefer our heroes humble, but the Greeks didn’t.

It’s easy to assume he was a golden boy from the very beginning, he did everything early and easily—got it all right on the first try. Or one might prefer the contrary camp that claims he was lucky and Not All That.

Neither of those play for me. The truth is, I think, in the middle. He made mistakes, did stupid stuff—not just politically, but militarily, despite his reputation as a military genius. The measure of success isn’t making no mistakes, but learning to recover from them quickly, which he did. And it’s that guy I want to explore in my fiction, not the larger-than-life hero.

Dancing with the Lion: Becoming & Rise available at Riptide Publishers

Published on July 22, 2019 16:37

July 18, 2019

A Boy and His Horse

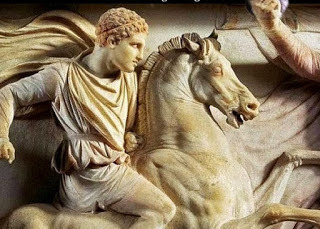

Some important characters in Dancing with the Lionhave four legs. And Alexander didn’t enter the pages of history alone.

[image error] He rode there.

History has given us some pretty famous horses: Traveler. Secretariat. Trigger. Marengo.

But Bucephalas was first. (Or Boukephalas, in the novel, the Greek spelling.)

At the ripe old age of twelve, Alexander tamed a big, dark horse* that nobody else could handle. It’s a great story, if also likely exaggerated. Yet that’s where their legendary friendship began. Supposedly, the horse would let nobody else ride him. And when a hill tribe kidnapped Boukephals at one point during the campaign, Alexander threatened to lay waste to the entire countryside and butcher very person in the region unless they brought his horse back.

They brought his horse back.

When Boukephalas died in India, Alexander even founded a city and named it after him. Now, as much as Alexander loved Hephaistion, he didn’t get any cities named after him.

Macedonians adored their horses, and Boukephalas was a very special companion to Alexander. For those of us who’ve loved a special pet, we can empathize.

And it’s not just Alexander’s Boukephalas who plays a role in the book. If we don’t know the name of Hephaistion’s horse in history, in Dancing with the Lion, he’s Brephas, who was raised from birth by Hephaistion, and is just as precious to him as Boukephalas is to Alexander. Perhaps even more so, as Alexander has just acquired Boukephalas a few months before the novel opens, whereas Hephaistion has had Brephas for years.

So it was fun to give some personality not just to the two-leggeds, but the four-leggeds. Horses play a significant role, as Hephaistion comes from a family that breeds and trains them.

I’d like to give a shout-out to well-known SFF novelist Judith (Judy) Tarr and Carolyn Willekes ( The Horse in the Ancient World ), who did their best at different points to keep my horse facts on track.

(*Boukephalas is often called “black,” but the word in Greek just means “dark,” and the Pompeii mosaic shows him as a brown bay, a very, very common coat shade. So that’s what he is in the novel. Hephaistion gets the cool horse colors. Brephas is a sandy-bay.)

Published on July 18, 2019 18:18

July 17, 2019

Alexander's Mum: Bitch from Hell?

(Another from the series of blogs written for the publication of Dancing with the Lion: Becoming.)

Modern portrayals of Alexander’s mother (Olympias-Myrtalē) are almost universally hostile, not just in fiction, but also in history books. Just consider how Oliver Stone cast and portrayed her in the 2004 “Alexander”: Angelina Jolie in heavy eye-makeup, a snake twined around her arm, slinking about palace corridors to spy, and quite possibly complicit in the murder of her husband, the king.

Was she really such a bitch?

Almost certainly not. She was a woman trying to survive at a polygamous court in a man’s world. She did do some horrific things, although killing her husband wasn’t one of them. But nothing she did wasn’t also done by her husband or son. Their actions were seen as savvy, or at least necessary, politicking. When a woman did it, that was horrible.

Her bad rep owes chiefly to ONE ancient historian: Plutarch.

Who the hell is Plutarch and why do you care? Well, he invented biography. He was interested in what made people tick. But he was also a “moralist.” That is, he wasn’t just interested in why Alexander became Great, but in teaching his readers ethics along the way.

Who the hell is Plutarch and why do you care? Well, he invented biography. He was interested in what made people tick. But he was also a “moralist.” That is, he wasn’t just interested in why Alexander became Great, but in teaching his readers ethics along the way.Now remember, Greek men were notoriously misogynistic. Perikles of Athens said the best women were not to be spoken of in public, either for ill or good. Plutarch wasn’t from Athens, but he shared the general Greek opinion that there was little worse than a clever woman.

And Myrtalē was extremelyclever.

At polygamous courts, the most important male in a woman’s life was not her husband, but her son(s). This is true even in non-polygamous courts, but in a polygamous situation, not only was a woman’s status tied to the sons she could produce, but her very life might hinge on one of them rising to the throne. Philip married five women in his first five years as king. Myrtalēwas number four or five (their order isn’t clear). From her perspective, that’s four-to-one odds against her, but she put her son on the throne.

Whether in fiction or history, a lot of emphasis gets placed on the role Alexander’s father played in his life. That’s true in Dancing with the Lion too. As a coming-of-age story, it may explore the love that developed between Alexander and Hephaistion, but even more, it’s a novel about fathers and sons.

Yet it was Alexander’s motherwho kept him alive long enough to reach his teen years, where the novel begins. In Dancing, Alexander and Myrtalēdo quarrel at times. She has her blind spots, but I made a concerted effort to get away from portrayals of her as some sort of witchy femme-fatale, sexually jealous of Philip’s other wives. She didn’t care who he slept with, as long as it didn’t result in another son to compete with hers.

Want to know more about such a fascinating, powerful woman (outside the novel)? The best modern biography is Elizabeth D. Carney’s Olympias.

Published on July 17, 2019 12:32

July 15, 2019

Alexander and Women

(The following post first appeared as part of a blog tour for the release of Dancing with the Lion: Becoming. I will reposting all eight of them on my own blog over the next two weeks.)

I’ve heard that Alexander was sympathetic to women. Was he an early femininst?

No. And yes.

Ancient Greece was famously misogynistic. Even Sparta’s supposed freedom for women was all to one purpose: turn them into superior baby-making machines.

Compared to most Greek men, Alexander did express uncommon respect and sympathy. When Timoklea, a highborn Theban, was brought before him for judgment after having killed her rapists (his soldiers), he took herside. And when he was told his sister Kleopatra had taken a lover (after her husband’s death), his reply was, “Well, she ought to enjoy herself.” To say neither of these responses was typical might be a ginormous understatement.

Compared to most Greek men, Alexander did express uncommon respect and sympathy. When Timoklea, a highborn Theban, was brought before him for judgment after having killed her rapists (his soldiers), he took herside. And when he was told his sister Kleopatra had taken a lover (after her husband’s death), his reply was, “Well, she ought to enjoy herself.” To say neither of these responses was typical might be a ginormous understatement.

Likewise, he was kind to the childless Ada of Karia (a kingdom in south Turkey). She’d been queen there before being ousted by a male relative. Alexander put her back on the throne, and she adopted him as her heir. While that eventually got him her kingdom to add to his growing collection, he did seem to genuinely care about her and kept her on the throne until her death.

Then there was Sisygambis, mother of the Persian Great King Darius—e.g., the mum of Alexander’s chief enemy. After the Battle of Issos, the first major encounter between the two kings, Darius fled the field—leaving behind his whole family. Alexander visited them. They’d been wailing not just for Darius (whom they thought dead), but out of fear of rape, etc. What usually happens to women in war. Instead, Alexander had them protected, refused to take Darius’s wife as his mistress because her husband was still alive, and treated the elderly Sisygambis with utmost respect. He continued to call her “Mother” for the rest of his life, sending her presents from his travels. When Alexander later died in Babylon, she turned her chair to the wall and starved herself to death, in grief.

Now, let’s be honest here. These are lovely, romantic tales. Had Timoklea been a slave, not a highborn woman, not only would Alexander not have cared, he’d never have heard about her rape in the first place. And Sisygambis probably feared what would happen after Alexander was gone, so better to die on her own terms. Also, Alexander supposedly gave away his mistress Kampaspe to his favorite painter Apelles because Apelles was (he said) in love with her. So far as we know, Alexander didn’t ask Kampaspe’sopinion before doing this.

So no, Alexander wasn’t a feminist. He belonged to his time. Yet for the ancient world, his sensitivity to women was unusual. We can, I believe, thank his mother (and sisters) for making him as much of a feminist as the ancient world might allow.

Follow Kleopatra’s story in Dancing with the Lion. It’s not ALL about the boys! Alexander’s sister has her own coming-of-age arc across both books, too.

I’ve heard that Alexander was sympathetic to women. Was he an early femininst?

No. And yes.

Ancient Greece was famously misogynistic. Even Sparta’s supposed freedom for women was all to one purpose: turn them into superior baby-making machines.

Compared to most Greek men, Alexander did express uncommon respect and sympathy. When Timoklea, a highborn Theban, was brought before him for judgment after having killed her rapists (his soldiers), he took herside. And when he was told his sister Kleopatra had taken a lover (after her husband’s death), his reply was, “Well, she ought to enjoy herself.” To say neither of these responses was typical might be a ginormous understatement.

Compared to most Greek men, Alexander did express uncommon respect and sympathy. When Timoklea, a highborn Theban, was brought before him for judgment after having killed her rapists (his soldiers), he took herside. And when he was told his sister Kleopatra had taken a lover (after her husband’s death), his reply was, “Well, she ought to enjoy herself.” To say neither of these responses was typical might be a ginormous understatement. Likewise, he was kind to the childless Ada of Karia (a kingdom in south Turkey). She’d been queen there before being ousted by a male relative. Alexander put her back on the throne, and she adopted him as her heir. While that eventually got him her kingdom to add to his growing collection, he did seem to genuinely care about her and kept her on the throne until her death.

Then there was Sisygambis, mother of the Persian Great King Darius—e.g., the mum of Alexander’s chief enemy. After the Battle of Issos, the first major encounter between the two kings, Darius fled the field—leaving behind his whole family. Alexander visited them. They’d been wailing not just for Darius (whom they thought dead), but out of fear of rape, etc. What usually happens to women in war. Instead, Alexander had them protected, refused to take Darius’s wife as his mistress because her husband was still alive, and treated the elderly Sisygambis with utmost respect. He continued to call her “Mother” for the rest of his life, sending her presents from his travels. When Alexander later died in Babylon, she turned her chair to the wall and starved herself to death, in grief.

Now, let’s be honest here. These are lovely, romantic tales. Had Timoklea been a slave, not a highborn woman, not only would Alexander not have cared, he’d never have heard about her rape in the first place. And Sisygambis probably feared what would happen after Alexander was gone, so better to die on her own terms. Also, Alexander supposedly gave away his mistress Kampaspe to his favorite painter Apelles because Apelles was (he said) in love with her. So far as we know, Alexander didn’t ask Kampaspe’sopinion before doing this.

So no, Alexander wasn’t a feminist. He belonged to his time. Yet for the ancient world, his sensitivity to women was unusual. We can, I believe, thank his mother (and sisters) for making him as much of a feminist as the ancient world might allow.

Follow Kleopatra’s story in Dancing with the Lion. It’s not ALL about the boys! Alexander’s sister has her own coming-of-age arc across both books, too.

Published on July 15, 2019 11:29

February 13, 2019

Alexander & Hephaistion: Historical Besties for V-Day

As Valentine’s Day rolls around, and I’m working on final edits for the Alexander novels as well as mulling over Hephaistion for an academic biography, I’m reminded of one of the things that originally caught my attention.

As Valentine’s Day rolls around, and I’m working on final edits for the Alexander novels as well as mulling over Hephaistion for an academic biography, I’m reminded of one of the things that originally caught my attention.Alexander and Hephaistion are a great love story. I don’t mean romantic love (eros), although maybe they had that too, at least as boys. I mean theirs is a true LOVE story (philia).

“Philalexandros” is the name Alexander gave Hephaistion, at least according to Plutarch (Alex. 47.5), who adds it wasn’t a one-time clever come-back to supporters of Krateros (Hephaistion’s chief rival at court). Apparently he used it a lot (Plutarch uses "frequently"). It translates as “Lover of Alexander,” in contrast to Krateros as “Lover of the king” (Philobasileus).

The word used here for love, “philia,” often gets translated as “friendship,” but that doesn’t do it justice. To the Greeks, philia stood above eros, or simple desire. One could eros a boy, a woman, or a well-cooked piece of tuna. They used it much as we use “love” today. But philia was reserved for people, or one’s city-state, or perhaps ideals. Philiawas assumed to be of longer standing, if not as fiery. The poets cry out that they’re “sick” with eros. The same language isn’t used of philia. So Alexander is saying that Krateros loves/respects his position as king. But Hephaistion loves Alexander, the man. In another story, where one of the Persian royal women accidentally bows to Hephaistion, not Alexander, and is embarrassed, Alexander replies with, "He is Alexander, too." (See the illustration above [Curt. 3.12.17]).

That’s what I find of interest. How many of history’s most powerful men (or women) had a true best friend? Someone s/he trusted above all others to love him for him/herself? It’s not unique, but it is rare. Power usually kills trust, and I think it did kill Alexander’s trust in a lot of those around him. But not his trust in Hephaistion.

One can question aspects of this legendary friendship. Afterall, we have multiple issues with our original sources. Some issues that pop up like dandelions in spring:

1) Were they really boyhood friends, or is that a later assumption/insertion?2) Was the Achilles/Patroklos trope one they used themselves, or was it made up by later Roman-era authors (esp. Arrian) seeking to flatter imperial patrons? Or maybe they used it once or twice, but it got padded and blown up by later authors?3) (The Million Dollar Question) Were they really lovers, or just Bromance Buddies? All are legitimate questions. My own answers are 1) I think they were, 2) it was probably exaggerated later (Alexander did court Achilles comparisons), and 3) yes, at least when they were boys, but who knows later and it doesn’t really matter to their mutual affection. I tend to be less skeptical about Hephaistion’s importance to Alexander in general, although I remain carefully cautious about the exact nature of that tie (whether ever sexual or not).

The thing is…it didn’t matter. And that’s what I want to elevate on this Valentine’s Day. One of the best historical love stories I know isn’t about romantic love of the sexual variety.

It’s about the most powerful man in his section of the world at the time with a friend he genuinely trusted, even when he’d become paranoid about virtually everyone else. When Alexander lost Hephaistion to some sort of febrile illness, he grieved not unlike a spouse who’d lost a long-time partner, and died about ten months later. If he didn’t die of a broken heart, I’ve argued elsewhere his death wasn’t unrelated to his profound grief (w/ Eugene N. Borza, "Some New Thoughts on the Death of Alexander the Great," The Ancient World 31.1 (2000) 1-9). Alexander speaks of Hephaistion as “more important than my own head.” That’s some serious importance.

It can be tempting for historians to get cynical about our subject matter, or about our sources—not unfairly. Doing real history tends to burst bubbles and quash romantic notions about people in the past. History is not myth, and whatever myths Alexander wanted to perpetrate about himself, that statue had clay feet. Very porous clay feet.

But true love does exist, and some people are lucky enough to find it. I think Alexander was one of the lucky ones. He had a true love and loyal friend.

But true love does exist, and some people are lucky enough to find it. I think Alexander was one of the lucky ones. He had a true love and loyal friend.So on Valentine’s Day, I wanted to celebrate a real historical love story that wasn’t necessarily romantic (eros). Maybe they had romantic love, too; I find it possible, if also impossible to corroborate from the state of our evidence.

Yet it was the love born of long-standing friendship, philia, that sat foremost. This love was remembered and remarked on by both their contemporaries as well as later authors.

And that's pretty romantic.

Published on February 13, 2019 21:00

September 27, 2018

A Deal with the Devil (Kavanaugh hearings)

Some thoughts on the Blasey Ford/Kavanaugh hearings....

As I see it, two layers here intersect, but should not be conflated. The first is Kavanaugh's confirmation. The other is the verisimilitude of Blasey Ford's allegations. The problem is an assumption that bringing forward Blasey Ford's allegations at the 11th hour was done solely to stop the confirmation and that means they're false (or at lease "mixed up," to use one Republican senator's assessment, even before hearing her testimony). This is false logic, and I'd ding a student who tried to use it in a paper. Why?

We have a verifiable paper trail. One could argue all of it is a lie--everybody on the Democratic side is making it up from the get-go--but that seems overly conspiratorial. Let's take the basics: Blasey Ford submitted her allegations to her representative when Kavanaugh was merely one of several names that had floated to the top of potential Supreme Court nominees. But--this is very important--she asked to remain anonymous, because she feared (rightly) the blow-back. The woman is a psychologist. She's probably better suited than most of us to assess the likely outcome of her emergence from obscurity with name attached.

So the issue is not that she failed to come forward earlier in the confirmations (she clearly did come forward earlier), but with why her allegation was saved until later.

Some would/have tried to sing the ol’ “Why didn’t she report it at the time?” song, which is notably tone deaf in the wake of the many #WhyIDidn’tReport stories. We won’t even look at the difference between the early 1980s and the late 20-teens, in how women were treated in court for allegations of sexual assault. She’d have been slut-shamed; I know, I graduated high school in 1982. I wouldn’t have reported it, either. I could go into this further but I have other fish to fry. If you’re inclined to blame her for not reporting it in the early ‘80s, you’re living on a different planet, or at least in a delusional bubble.

The better question is why did Feinstein wait so long to bring up this letter? I think anyone honestly considering the whole thing must ask it. Yet I fear it's been couched in an automatic negative that assumes, as part of it, the fabrication of the entire episode. E.g., she held it back because Feinstein and company cooked it up at the last minute. (But see above about when Blasey Ford wrote and submitted it, originally.)

I'd like to re-posit Feinstein's reasons to the positive: she sought to respect Blasey Ford's request for anonymity, and her legitimate fear of going public. Blasey Ford has a family, and kids. Terror of reporting due to threat (or at least fear) of retribution against not just the victim, but a victim’s family, is a potent tool for criminals of all types since antiquity. Here the threat wasn’t from Kavanaugh, per se, but from the rabid supporters of his confirmation who would—and did—threaten Blasey Ford and her family with violence.

Feinstein knew things would get ugly; she got elected in the wake of the Anita Hill hearings. She was disinclined to bring it up if it looked as if Kavanaugh would not be confirmed anyway. Blasey Ford submitted her accusations because she was worried that Kavanaugh would wind up on the Supreme Court. If it seemed like he wouldn't, why expose Blasey Ford to a potential 3-Ring Circus?

So yes, when it seemed that he might be confirmed, Feinstein brought out the letter...not because it was false, or made up, but because the time had come, and she suspected Blasey Ford would want that--which appears to have been the case. As Blasey Ford said herself, she was terrified to testify on Thursday, but believed testifying was her civic duty.

So Feinstein kept the letter confidential to protect Blasey Ford's requested anonymity, not as some trumped-up charge at the last minute. When it looked as if Kavanaugh might be confirmed in a highly partisan vote, Feinstein decided the good of the many outweighed the good of the one, and gambled Blasey Ford would agree. You may not like Feinstein's decision, you may think the letter should have been put forward sooner, but I do not believe her motives for reserving it were, as Kavanaugh claimed, "seek and destroy"...unless it was to avoid seek and destroy of Blasey Ford, re-victimizing her.

Is it political? Of course it is, but not in the way so stridently touted today by Kavanaugh. Roe vs. Wade is the real political battle here. Yet putting a sexual predator on the High Court (in a lifetime appointment) just to abolish Roe vs. Wade—that’s immoral. I understand the larger question of abortion is complex. I am pro-Choice, but understand, and even respect, pro-Life arguments, even if I think they mostly rest on faulty biology or outdated theology. But pick a better candidate.

This is all about TIMING, as Kavanaugh’s supporters fear that control of at least the House will change and the bulk of the US electorate does not favor abolishing Roe vs. Wade. It’s become “Kavanaugh or bust.” Yet putting Kavanaugh on the court just to get a swing vote to kill Roe vs. Wade is a deal with the devil.

Published on September 27, 2018 23:23