Jeanne Reames's Blog, page 3

November 21, 2019

Eros, Philia, and Love Magic

Some readers have asked why, even after the boys become lovers, I persist in referring to them as “friends” in the novels? Am I trying to hedge regarding their sexual relationship?

Not at all. I’m trying to highlight a more equal partnership.

The ancient Greeks thought about love differently than we do, sometimes starkly so. They had several different terms, something that modern writers (such as C.S. Lewis in The Four Loves ) make more of than they should. After all, we also have a plethora of terms. We can love, like, desire, crush-on, fancy, adore, appreciate, hold dear…all of which have varied connotations just like their Greek counterparts.

So the difference isn’t with the variety of terms, but with how they categorized them.

Eros —best translated as “desire”—is often described with terminology reminiscent of disease. It makes one weak, helpless, unable to sleep, unable to eat, unable to concentrate; one burns with desire like a fever. All descriptions we’d recognize today. But these aren’t goodthings, not a state one wants to pursue, especially for men.

Self-control (sophrosunē) was the aspired-to ideal, which erosupended. Therefore, eros was a PROBLEM for Greek men.

In the first novel, Becoming , Hephaistion wrestles with the eros he feels for his friend, mostly by trying to ignore and sublimate it. Because he’s almost three years older than Alexandros, and matured early, he’s more sexually aware, if not necessarily all that sexually experienced. By the end of the first novel, they do get their act together.

Yet in the second novel, Rise , they must negotiate the division between eros and philia. Yes, philia is often translated as friendship, but this is where modern definitions can oversimplify HOW the ancients used terms. We tend to view friendship as existing on the edges of other, more important relationships: familial or romantic. But to the Greeks, philia was considered the higher love, topping mere sexual desire (eros). So for them, romantic love existed on the edges of friendship! Philia exalted those who felt it, made them better. Eros might, instead, drag down those who suffered it, driving a man mad. In turn, he sought to make the object of his desire share his insanity. The Greeks virtually invented the notion of “crazy for love.”

We see the distinctions between eros and philiamost clearly in Greek love magic.

Popular assumption rarely associates “magic” with the Greeks. Aren’t they the inventors of philosophy and rational thought? Well, yes, but magic was HUGE all over the ancient world. And then, as now, affairs of the heart occupied a lot of it.

It’s largely men who use aggressive, sometimes violent spells to compel women (and occasionally other men) to submit to them sexually. Setting aside for the moment whether any of this actually worked, it’s the language of Greek love spells that concern us. Here’s an example:

“Seize Euphemia and lead her to me, Theon, loving me with crazy desire, and bind her with inescapable bonds, strong ones of adamantine, for the love of me, Theon, and do not allow her to eat, drink, obtain sleep, jest, or laugh, but make her leap out…and leave behind her father, mother, brothers, sisters, until she comes to me.” (SM 45, trans. C. Faraone)

This is quite typical, and hardly respectful to Euphemia (or the other female targets of these spells). Theon wants to transfer onto her the desperation he feels himself. We could romanticize this, but shouldn’t. Too much of the violent and jealous language of modern romance narrative is rooted in Greco-Roman models. Stalking and controlling behavior isn’t romantic; it’s creepy. “He ravaged her mouth,” or “He rammed into her hard,” isn’t love language. “Ravage” means “to cause severe damage to.” That’s not my idea of a good kiss. Greek men like Theon who cast these aggressive love spells (called agogē or “drawing” spells) wanted to ravage their victims, not woo them. We might want to rethink common Romance tropes that arise from these antique, misogynistic models: compelling a woman, not courting her and inviting her agreement, equal to equal. These are not empowering for women (or men) today.

What Hephaistion and Alexandros share certainly involves desire (eros), but is more respectful. If each are occasionally guilty of manipulation because they’re young and insecure, it’s important to them that they’re in it together, and by choice. As they assert on the beach at the end of the first book, Becoming: “Friends first.” “Friends always.” They aren’t casting coercion spells on each other. Hephaistion does visit a magician near the end of Becoming, but to find a spell to fall OUT of love, not to compel Alexandros to his bed, because he loves his friend more than he lusts for him. The young magician he visits is initially confused by his request, then praises him for such a noble aspiration.

That’s philia . The love for another that wishes the best for them, not necessarily for one’s self. Eros is self-centered and self-involved, desperate, but concerned with power and social “face.” Philia acknowledges the autonomy of the Other in the equation.

Thus, philia comes closer to our modern notion of love. Returning to Greek love magic, we find philia charms used in what are clearly sexual relationships, but which are faithful, and most often employed by women. Erotic spells like that used by Theon above describe the victim as leaving her [or his] house, parents, spouse, children and “forgetting” about them, to rush to the bed of the man. They’re separating and controlling. By contrast, philia charms are about retaining a lover/spouse.So my use of “friends” (philos) is preferable to “lover” (erastes) for Alexandros and Hephaistion’s relationship. It elevates partnership over desire and conquest. Equality over social hierarchy.

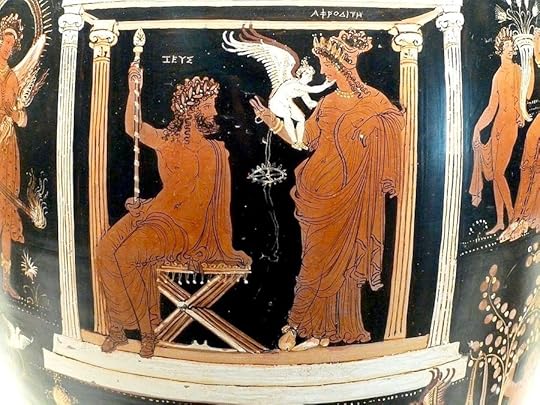

(The image, from Greek pottery, shows Aphrodite holding a iunx, or magic charm, used by women to enspell men to love them/stay faithful. It was whirled around on the strings and made a buzzing sound while the motion held the eye.)

Published on November 21, 2019 19:57

November 14, 2019

Love and War

A persistent, annoying, misogynistic delusion says Romance readers (female or male, but especially female), or women more generally, can’t handle things like hard science fiction, political intrigue, and, especially, military matters. Our pretty little heads are incapable of understanding that “serious stuff.” All we care about are love affairs and fashion.

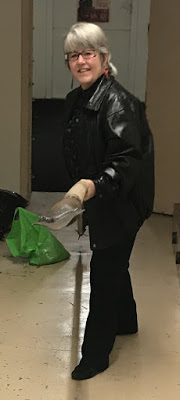

A persistent, annoying, misogynistic delusion says Romance readers (female or male, but especially female), or women more generally, can’t handle things like hard science fiction, political intrigue, and, especially, military matters. Our pretty little heads are incapable of understanding that “serious stuff.” All we care about are love affairs and fashion.Hoo-boy, don’t get me started or I might skewer somebody. (Author at right, with a Macedonian sarissa.)

Funny story about SF author Catherine Asaro: she’s known for her hard-SF Romances, but what a lot of readers don’t know is she’s also Dr.Catherine Asaro, with a PhD in chemical physics from no less a school than Harvard. Some years back, on a now-defunct bulletin board, a male reader proceeded to try to mansplain how Asaro’s physics of space travel just wouldn’t work, and poor lady authors who want to write romance shouldn’t attempt a SERIOUS genre such as hard SF. Well, Dr. Asaro dropped into the convo, citing several of her own published articles in peer-reviewed journals, then proceeded to demolish fan-boy’s ignorant objections to her theories. It was a beautiful thing to behold.

Women do math and science, dammit—as demonstrated by my Kleopatra in the novels.

I don’t believe for one minute that women readers, as much as men readers wouldn't like to know a little about the military matters I describe in Dancing with the Lion, not just the hair and clothes (as I do detail in another blog).

[image error] When non-specialist modern readers imagine ancient Mediterranean armies, it’s usually the Roman legion that comes to mind. The Greek phalanx is similar…but not. A phalanx is a big rectangular block of infantry, usually 8-deep, that presented a “locked shields” front. Larger armies were made up of several phalanges (phalanxes) in a row. Armies were chiefly infantry as horses don’t do well in the rocky Greek south. So their armies had a lot of light troops, such as slingers, but little horse.Yet Greek infantry was legendary. These “Men of Bronze” were sought-after mercenaries in Ancient Near Eastern armies, and would famously rout the Persians at the Battle of Marathon despite being outnumbered. Southern Greek cities also had excellent navies, although Macedonia didn’t, so I won’t address navies here.

The infantryman, or “hoplite,” was armed with a big-ass round, convex shield covering him from chin to knee; a bronze helmet; and—depending on how much money his family had—a bronze breastplate or a cuirass of fused, tough, glued linen with girdle plates; and maybe bronze greaves covering his shins. From the front, this presented a pretty solid defense. But if, in video-games, Greek soldiers all look alike, in truth, Greek armor varied a lot. Helmet styles differed vastly by region, and how much armor a soldier could afford also differed. Shield devices were personal (as in the image above). Put simply: THERE WAS NO ANCIENT GREEK UNIFORM. Individuality mattered. (Hoplite arming, image shows how the shield was held inside.)

The infantryman, or “hoplite,” was armed with a big-ass round, convex shield covering him from chin to knee; a bronze helmet; and—depending on how much money his family had—a bronze breastplate or a cuirass of fused, tough, glued linen with girdle plates; and maybe bronze greaves covering his shins. From the front, this presented a pretty solid defense. But if, in video-games, Greek soldiers all look alike, in truth, Greek armor varied a lot. Helmet styles differed vastly by region, and how much armor a soldier could afford also differed. Shield devices were personal (as in the image above). Put simply: THERE WAS NO ANCIENT GREEK UNIFORM. Individuality mattered. (Hoplite arming, image shows how the shield was held inside.)Why the differences among real soldiers? They armed themselves; city-states didn’t provide equipment. So what they brought to the field was whatever they could afford. Also, the primary weapon of the Greek infantryman was the SPEAR, not a sword. Swords were secondary, used only after your spear broke. While Greek armies did have archers along with slingers and peltasts (javelin-men), Greek infantry viewed the bow as a coward’s weapon.

When Philip took over as king of Macedon, the army got a serious overhaul. First, Macedonia—unlike the south—had horses. In fact, prior Macedonian armies had been CAVALRY armies, with limited infantry. Philip reformed the infantry by lightening their armor and giving them the ultimate “pig-poker”: a 15-foot sarissa, or pike. It was about twice as long as a normal Greek spear, requiring one to wield it two-handed.

[image error] Then he shaped up the cavalry, arming them more heavily and deploying them in triangular “spear point” formations, which allowed them to shift direction quickly at a gallop. They carried the xyston, which wasn’t as long as a sarissa, but still formidable. Incidentally, ancient cavalry used neither saddles nor stirrups, only a saddlecloth.

[image error] This Macedonian sarissa phalanx became the ANVIL, while his heavy cavalry became the HAMMER. The Macedonian phalanx would engage the enemy, holding them in place on the battlefield, then Philip would send in his much more mobile cavalry to smash into the enemy flank or rear, tearing them to shreds. It worked. Over and over, it worked. Alexander took that formation strategy to Asia. It worked there too.

So when I describe military matters in Dancing with the Lion, now readers have a better visual image. And don’t let anybody tell you female readers can’t enjoy reading battle scenes, or that female novelists can’t write them.

The hell we can!

After all, the ancient Greeks paired the goddess of love, Aphrodite, with the god of war, Ares. And in the Ancient Near East? Innana/Ishtar was goddess of both, together.

(The sarissa I'm holding above is part of the on-going research of Dr. Graham Wrightson, USD, who kindly let the author handle it, as she also teaches an undergraduate capstone class as well as a graduate seminar on Greek military history. The other modern image belongs to Ryan Jones, another Calgary graduate under Waldemar Heckel.)

Published on November 14, 2019 21:07

November 12, 2019

Ancient Greek Food & the Symposion (Supper Party)

[image error]

A few readers have remarked on my descriptions of meals, and asked how can we know so much about what they ate? Well, in part, because we have recipes! We also have a lot of stray food mentions in ancient texts, plus imagery in various mediums from pottery to mosaics. Andrew Dalby and Sally Granger have done superb work on Greek (and Roman) food, including

The Classical Cookbook

and

Siren Feasts

. I recommend both.

Some of the food you’d order today in a Greek restaurant might have graced an ancient table. Souvlaki has been around forever; we’ve even found grills with indentions for spits to set over hot coals. (At left, with an oven above.) Olives existed in great variety then as now, wheat and barley bread, feta & various sheep and goat cheeses, little pancakes for breakfast (tiganites), grilled fish, eel, and shellfish of all types, cucumber-and-soured-milk (e.g., tzatziki)…the list goes on.

Yet some key modern ingredients in Greek cooking were missing. The lemon, for instance. Citrus had yet to find its way to the Mediterranean. In fact, thank Alexander for the lemon in modern Greek cuisine, as his interactions with Persia would bring the citron west, and from the citron and mandarin orange would come all modern types of citrus (citron = citrus).

No tomatoes, either! Or peppers. Or those yummy Greek potatoes. All this produce is native to the Americas, and appeared in Europe only after 1500.

No sugar from sugar cane! Sweetening came from honey (and a bit from sugar beets). Herbs and spices were both known, but imported spices (pepper, cassia, cinnamon, ginger, and cardamom) could be expensive. Herbs were more common, including anise, thyme, oregano, dill, fennel, hyssop, rosemary, rue, saffron, coriander, mint, and silphium. That latter is now extinct, but was enormously popular in ancient cuisine.

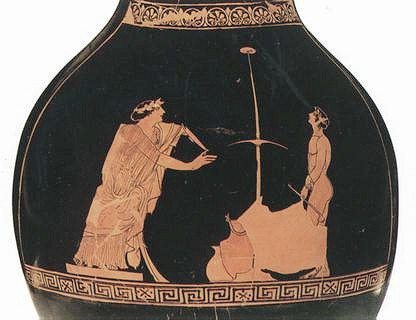

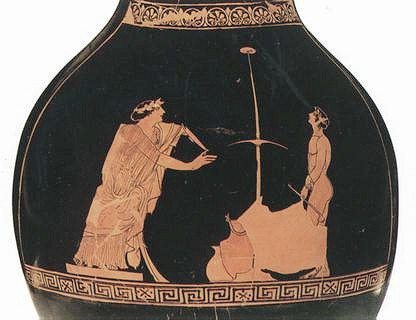

Drinks were simple. You had water, or you had wine. In fact, the Greeks often watered their wine. Think “wine spritzer” (without the carbonation). This practice served the dual purpose of making the wine go further, but also diluted its alcoholic effects. The usual mix for dinner was 3 parts wine to 2 parts water. The most common ancient Greek wine cup (kylix, see below) looks to us more like a soup bowl. It’s wide, flat, and decorated around the outside as well as in the bowl center. Other cup types existed, but the kylix was especially associated with the symposion, or supper party. Yet the literal meaning of symposion ISN’T “supper party,” but “to drink together.” Wine—not food—was the focus, and Greek wine service was ritualized and elaborate, not unlike tea service in some countries.

[image error]

There were also a number of games played at supper parties, including the popular “kottobos,” which was a weird mix of spin-the-bottle and darts. In Kottobos, guests threw the wine lees (junk at the bottom of the cup) at a target on a tall bronze pole. (See the image inside the cup below.) If they hit the target and knocked it down, they got to claim a kiss from a fellow reveler.

Not all ancient wine-drinking cultures engaged in the practice of watering their wine, including the Macedonians, as described in the novels. Southern Greeks (rather haughtily) considered drinking wine “neat” or a-kratos (without the mixing krater [a type of pottery]) to be a sign of a barbarism. (Horrors!)

The Greeks ate two primary meals each day. The first was a light lunch (or “day-meal” as I call it in the novels): mostly finger foods, plus bread. Meat was rarely included. The main, evening meal was typically served after sunset, when men came in from the fields or finished other work and cleaned up. Even today, Greeks eat late, relatively. (“Breakfast” was just a hunk of bread dipped in wine-water to make it less stale, so not considered a real “meal.”)

Dinner could range from simple to elaborate, and while it usually involved at least some bread or grains, vegetables and meat (if any) varied: from porridge with a few veggies and some stew meat, to a many-coursed banquet.

Another thing, while families did occasionally eat together, having an evening “family meal” wasn’t an ancient Greek cultural assumption. It’s what happened in the absence of alternatives. Even among the poor or village farmers, a bunch of male buddies might get together at the house of one, to share conversation and food, while the family women (and male children) would be excluded to eat in the kitchen, or upstairs.

Ergo, Greek families might gather in the courtyard at sunup to pray together at the family altar, but they didn’t necessarily end the day eating together at a supper table.

Some of the food you’d order today in a Greek restaurant might have graced an ancient table. Souvlaki has been around forever; we’ve even found grills with indentions for spits to set over hot coals. (At left, with an oven above.) Olives existed in great variety then as now, wheat and barley bread, feta & various sheep and goat cheeses, little pancakes for breakfast (tiganites), grilled fish, eel, and shellfish of all types, cucumber-and-soured-milk (e.g., tzatziki)…the list goes on.

Yet some key modern ingredients in Greek cooking were missing. The lemon, for instance. Citrus had yet to find its way to the Mediterranean. In fact, thank Alexander for the lemon in modern Greek cuisine, as his interactions with Persia would bring the citron west, and from the citron and mandarin orange would come all modern types of citrus (citron = citrus).

No tomatoes, either! Or peppers. Or those yummy Greek potatoes. All this produce is native to the Americas, and appeared in Europe only after 1500.

No sugar from sugar cane! Sweetening came from honey (and a bit from sugar beets). Herbs and spices were both known, but imported spices (pepper, cassia, cinnamon, ginger, and cardamom) could be expensive. Herbs were more common, including anise, thyme, oregano, dill, fennel, hyssop, rosemary, rue, saffron, coriander, mint, and silphium. That latter is now extinct, but was enormously popular in ancient cuisine.

Drinks were simple. You had water, or you had wine. In fact, the Greeks often watered their wine. Think “wine spritzer” (without the carbonation). This practice served the dual purpose of making the wine go further, but also diluted its alcoholic effects. The usual mix for dinner was 3 parts wine to 2 parts water. The most common ancient Greek wine cup (kylix, see below) looks to us more like a soup bowl. It’s wide, flat, and decorated around the outside as well as in the bowl center. Other cup types existed, but the kylix was especially associated with the symposion, or supper party. Yet the literal meaning of symposion ISN’T “supper party,” but “to drink together.” Wine—not food—was the focus, and Greek wine service was ritualized and elaborate, not unlike tea service in some countries.

[image error]

There were also a number of games played at supper parties, including the popular “kottobos,” which was a weird mix of spin-the-bottle and darts. In Kottobos, guests threw the wine lees (junk at the bottom of the cup) at a target on a tall bronze pole. (See the image inside the cup below.) If they hit the target and knocked it down, they got to claim a kiss from a fellow reveler.

Not all ancient wine-drinking cultures engaged in the practice of watering their wine, including the Macedonians, as described in the novels. Southern Greeks (rather haughtily) considered drinking wine “neat” or a-kratos (without the mixing krater [a type of pottery]) to be a sign of a barbarism. (Horrors!)

The Greeks ate two primary meals each day. The first was a light lunch (or “day-meal” as I call it in the novels): mostly finger foods, plus bread. Meat was rarely included. The main, evening meal was typically served after sunset, when men came in from the fields or finished other work and cleaned up. Even today, Greeks eat late, relatively. (“Breakfast” was just a hunk of bread dipped in wine-water to make it less stale, so not considered a real “meal.”)

Dinner could range from simple to elaborate, and while it usually involved at least some bread or grains, vegetables and meat (if any) varied: from porridge with a few veggies and some stew meat, to a many-coursed banquet.

Another thing, while families did occasionally eat together, having an evening “family meal” wasn’t an ancient Greek cultural assumption. It’s what happened in the absence of alternatives. Even among the poor or village farmers, a bunch of male buddies might get together at the house of one, to share conversation and food, while the family women (and male children) would be excluded to eat in the kitchen, or upstairs.

Ergo, Greek families might gather in the courtyard at sunup to pray together at the family altar, but they didn’t necessarily end the day eating together at a supper table.

Published on November 12, 2019 18:00

November 10, 2019

November 8, 2019

Kampaspē, Slavery, and the Uglier Side of Ancient Greece

When writing a novel about a prince and eventual world conqueror, the modern author must wrestle with how to depict those in society upon whose backs such privilege was built.

Enter Kampaspē, Alexandros’s mistress in Rise.

[image error] Although an hetaira(the highest class of prostitute in ancient Greece), she’s still a slave. Not only her well-being, but her very LIFE, depends on the good will of her owner. Alexandros is not a cruel master and expresses genuine fondness for her, even initially offering to buy her free, but that doesn’t change the uncertainty of her status. Writing scenes from her point-of-view allows me to show her reality. Ancient Greece got some things right: the invention of critical reasoning, the birth of democracy, and the, at least partial, acceptance of same-sex relationships. But it got a lot of things wrong. Misogyny was rampant and slavery assumed. As an author, I can’t ignore that.

Ancient slavery differed from American colonial in several important ways, not least that skin color had nothing to do with it. Greeks routinely owned other Greeks from different city-states, although as time progressed, a larger and larger number of slaves in Greece were non-Greeks taken in war. Families of moderate means usually owned 1-3 slaves, but even the largest factory operations owned slaves only in the hundreds, not thousands. Most of Greece was not a slave-society, unlike later Rome or the American South. A “slave society” is one whose economy depends on slave labor and would collapse without it. In ancient Greece, such a definition fit only Sparta’s helot system with state slavery, although by the Hellenistic Age, the economic importance of slavery had risen considerably, and by the late Roman Republic into the Imperial era, it ballooned into true “slave state” dimensions.

But even if Greece wasn’t a “slave society,” we can’t let that blind us to the horrors of a slave’s life. They were described as “living tools” and “two-legged livestock.” THINGS, objects, not people. Beatings were common disciplinary measures, and for a slave’s testimony to count in court, interrogation had to be conducted under torture. In artwork, they're routinely shown as "smaller" than their owners, almost like children.

Nobody much questioned this. It was just the “way of the world”—deeply embedded and taken for granted.

In fact, by the Imperial era, wealthy slaves might own slaves To modern minds shaped by Colonial slavery, that seems to be a very strange concept (both wealthy slaves and slaves owning slaves).Ancient Greece had no abolitionist movement, and philosophy mostly ignored it as a subject of moral discourse. While emancipation was possible in ancient Greece, it was uncommon. When it came, it was typically in old age, in thanks for a lifetime of service, and/or in a master’s will.

In fact, the modern notion of scientific racism owes to Aristotle(Aristoteles), Alexandros’s own teacher, who, building on the medical Hippocratic corpus, articulated the basics: some people are born inferior as a result of climate, ethnicity, or some innate flaw. “For that some should rule and others be ruled is a thing not only necessary, but expedient; from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule...” (Aristotle, Politics).

So Aristotle (and others) thought people—especially non-Greeks—wound up slaves by “physis”: nature. But the more common, and older, notion was that slaves became slaves by bad luck .

Again, the bulk of slaves became so as prisoners of war: why such categories as “skilled slaves” existed. If, at the end of battle, one had rounded up a goldsmith, teacher, blacksmith, or physician among the enemy captives, one didn’t toss them into the fields or mines to do hard labor. They continued to ply their trade, but gave the bulk of their earnings to their new master. One form of “investment” in ancient Greece, in fact, involved purchasing such skilled slaves. They were costly, but their owner could count on a good return on the investment across years, which is why skilled slaves found it difficult to earn freedom. They were their owner’s “Golden Goose.”

Again, the bulk of slaves became so as prisoners of war: why such categories as “skilled slaves” existed. If, at the end of battle, one had rounded up a goldsmith, teacher, blacksmith, or physician among the enemy captives, one didn’t toss them into the fields or mines to do hard labor. They continued to ply their trade, but gave the bulk of their earnings to their new master. One form of “investment” in ancient Greece, in fact, involved purchasing such skilled slaves. They were costly, but their owner could count on a good return on the investment across years, which is why skilled slaves found it difficult to earn freedom. They were their owner’s “Golden Goose.”Hetairai, such as Kampaspē, were a form of “skilled slave.” These “companions” (what hetaira means, literally) were trained to read, write, recite poetry, play music, keep up with politics, all in addition to any bedroom skills. In Kampaspē’s case, she was trained from a young age, and if she wasn’t an actual prisoner of war, she was sold into slavery as a result of political rivalry.

Her story is a tragedy. All too often in novels about ancient Greece, famous hetairai (such as Thaïs or Phryne) are portrayed as mistresses of their own destinies, choosing the rich men with whom they wish to cavort. The few historical mentions of Kampaspe paint her similarly, as from a prominent family in Larissa—a point I kept, if with a twist. Yet that popular notion is mostly a male fantasy, and such freedoms came only after establishing themselves. The bulk of hetairai, even at this high level, began as slaves, sometimes of older hetairai who acted as madams. As they aged, hetairaimight save enough to buy freedom, but their choices after were restricted.

Kampaspēis my answer to the romantization of Greek hetairai in fiction. When Alexander is suddenly unable to protect her (for reasons I can’t reveal without a spoiler), what recourse does Kampaspē have? She must seek a new master/mistress/patron. She ends up okay, but the life of even a skilled slave is lived on the side of a volcano.

There’s no way around the ugly of Greek slavery. Kampaspē is there to remind readers of it, even if she doesn’t suffer as badly as many did. Because it doesn’t matter how well she’s treated. She’s still a slave. And slavery is never justifiable.

Further Reading: Peter Hunt, Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery, Wiley-Blackwell, 2017.

Published on November 08, 2019 18:26

November 6, 2019

Hephaistion, Virtue, and Beauty

Anonymous Question (via Tumblr):

“So you emphasize Amyntor is ‘ugly’ in the first Dancing with the Lion novel, and sort of imply Hephaistion might not be his real son. Is there a reason for that? IS Hephaistion his son?”

Amyntor is a loose, literary parallel for the philosopher, Sokrates. The ancient Greeks maintained a confluence of assumed ideal characteristics: wealth, birth, beauty, intelligence, bravery, and athletic ability. This defined the “hoi aristoi,” or “best men”—the aristocracy. To be honest, it’s not so different from modern America, and elsewhere in the West, which tends to elevate celebrity beauty. Yet the Greeks did recognize it as a cultural fiction. Sokrates, especially, blew it up. He was reputedly the “ugliest man in Athens,” but also the wisest, and had the biggest heartthrob in Athens chasing him: Alkibiades. And, of course, Alkibiades (Alcibiades) challenged the assumption from the opposite direction; he was anything but a virtuous man. In any case, Sokrates was enormously controversial in his own lifetime, which led to his execution by state order. Later, he was virtually deified in the works of Plato and Xenophon, et al.

In the novels, Amyntor is a Sokrates figure. We have this unattractive man who’s nonetheless beloved by most who know him well (including his beautiful wife who gives her looks to her beautiful son). Yet in terms of politics and outside his family/circle, he's more controversial, in part because he speaks his mind.

Hephaistion doesn’t care about looks precisely because of his family. He knows what true virtue is. He’s well aware he’s attractive, and isn’t falsely modest, but he measures his own worth by other criteria. Despite the very pretty cover on Becoming, Alexandros is not exceptionally good looking. Hephaistion even observes of him: “Only a flatterer would call him handsome.” But Hephaistion falls for him anyway because he knows the truth: looks aren’t virtue. He seeks virtue.

Hephaistion doesn’t care about looks precisely because of his family. He knows what true virtue is. He’s well aware he’s attractive, and isn’t falsely modest, but he measures his own worth by other criteria. Despite the very pretty cover on Becoming, Alexandros is not exceptionally good looking. Hephaistion even observes of him: “Only a flatterer would call him handsome.” But Hephaistion falls for him anyway because he knows the truth: looks aren’t virtue. He seeks virtue.So as he comes to know Alexandros’s soul, he falls in love with the beautiful. It’s very Platonic (in the real sense). True virtue as beauty. Because he’s exceptionally attractive, but most of his family—who he loves dearly—are not, Hephaistion has a unique perspective. He sees past the surface, even while himself being a sort of ideal surface. For Hephaistion, his good looks are more handicap than help. I wanted to invert the notion of attractiveness as beneficial.

That’s why I wrote Amyntor as “ugly.” Because, in all the ways that matter, he’s not ugly at all. And therein lies the irony, which Greek theatre would appreciate. And maybe Plato, too.

(Ptolemy does note at one point, by the way, that Hephaistion resembles his brother Agathon, especially around the eyes.)

Published on November 06, 2019 16:05

November 4, 2019

Writing Kleopatra and Alexander's Other Sisters

In the guest blogs for Becoming, I talked about Alexander and Women, and Alexander’s Mum, but I wanted to save his sisters for the release of Rise, as all three have more important roles in the second half.

In my first drafts of Dancing with the Lion, Kleopatra—Alexander’s only full sister—played a role, even a significant one near the end, but not as a point-of-view character. Yet I’d developed a real love for the character, and it finally occurred to me, “Hey, why don’t you just let her speak for herself?”

So I did.

For a variety of reasons, I stayed out of Myrtalē’s head (Alexander’s mother, better known to posterity as Olympias). But Kleopatra was another matter, and it seemed useful to provide her view not only of her brother, but also of their mother and father.

Yet she added so much more. Kleopatra opens a window onto the women’s quarters. Some of that is shown in Becoming, but we get a better view in Rise with Kleopatra’s undermining of her father’s last wife, also a Kleopatra. (The Macedonians had popular names too, so think of “Kleopatra” as the ancient Macedonian version of Taylor, Madison, or Elizabeth.)

[image error] It’d be a spoiler to tell what happens, but suffice to say the three sisters (really half-sisters) gang up on the interloper. Kynnane wields a spear (yes, she really could; her father took her to war), but Kleopatra? She wields an abacus and a loom. And she’s the chess master behind it all. Or perhaps we should say, the math mind behind it, three steps ahead of everybody else.

Kleopatra would go on to become the Queen of Epiros where, after her husband’s death, she took over as regent for her son. She and her brother would remain close, and reportedly, when he was told that she’d taken a lover, instead of expressing the expected outrage, replied, “Well, she ought to be allowed to enjoy herself.”

Dancing with the Lion is a coming-of-age story for Alexander and Hephaistion, but also for Kleopatra. Although a secondary character, she has her own journey to maturity across both books. I hope readers enjoy reading about her as much as I enjoyed writing about her.

When I continue the series, she’ll remain a significant secondary character, providing an important view on what’s happening back in Greece, as her brother wends his way across Asia. In fact, at present, the opening scene of book #3, King, is in Kleopatra’s head.

Published on November 04, 2019 13:50

November 3, 2019

Alexander’s Heroes: Achilles and Herakles

Alexander may have become a hero to subsequent generations, but he had heroes of his own. The two he preferred most were Achilles (Akhilleus) and Herakles (Hercules in Latin). In book 2, Rise, he admits to Hephaistion that when he was young, he used to dress up in an ancestor’s old antique armor and pretend to be Achilles. It’s not so very different from the armies of children who recently knocked on doors for Halloween, dressed as Batman or Captain America.

Why Achilles and Herakles? He considered both to be his ancestors. We might view it as quaint, but the ancients really did believe the heroes of myth had been real, and some of the living were descendants of them.

On Alexandros’s father’s side, he claimed descent from Herakles, and Herakles appeared on his first coins (along with Zeus, Herakles’s father, on the coin reverse). Later, Herakles would morph into Alexandros himself, still wearing the lion-head helmet. In Rise, readers will discover how he got that helmet (or at least my fictional version). The series title (Dancing with the Lion) will also finally be explained. Lions were a symbol of royalty in the Ancient Near East back into the Bronze Age. Greece (and Macedonia) merely continued the tradition.

[image error] [image error]

On his mother’s side, however, he counted descent from Achilles. The young, brash hero of the Iliad appealed to a young, brash king. Herakles is typically depicted (and thought of by the Greeks) as an older man, late 30s to 40s. Philip prominently linked himself to Herakles. But the young Alexandros preferred the young Achilles, often depicted in Greek art as beardless.

Unlike Homer’s other epic hero, the crafty Odysseus, Achilles was a straight-shooter. He said what he thought, and Alexandros likes to think of himself the same way. Achilles was also a runner, his epithet in the Iliad being “swirft-footed.” Likewise, Alexandros is a runner.

Yet another reason Achilles might have appealed involves his legendary friendship with Patroklos, who, by the 4th century BCE, most Greeks (and Macedonians) considered Achilles’s lover too. Patroklos was older than Achilles, typically shown in art as bearded. And of course, their relationship is depicted as a sexual one in Madeline Miller’s popular The Song of Achilles .

[image error] In Becoming, it’s memory of “Akhilleus and Patroklos” that eases Alexandros’s mind about his own new relationship with Hephaistion. As prince, he shouldn’t be the beloved (eromenos), but then he recalls that Achilles had been Patroklos’s eromenos, and lost no honor for it.

Recent scholarship has raised questions about just how much the historical Alexander and Hephaistion made of an Achilles-Patroklos parallel. Some even go so far as to see it all as later Romanizing by the biographer Arrian, in order to please his patron, the Emperor Hadrian, who had a young lover, Antinoōs. So Arrian wrote Alexander and Hephaistion as Achilles and Patroclus…and by implication, so also were Hadrian and Antinoōs.

This is not a silly proposal, as Roman authors likedtheir historical-mythic parallels. Yet I’m inclined to think the comparison exaggerated rather than invented whole cloth, as Alexander’s interest in Achilles is evinced plenty elsewhere. To cast his best friend and probable lover as Patroklos would have suited him, and so I use it in the series.

In any case, Alexander the Great had his own heroes, on whose lives and deeds he both modeled himself, but against which he also competed.

Published on November 03, 2019 19:42

August 26, 2019

Hephaistion's Physical Appearance in Dancing with the Lion

anonymous asked: hello. how do you imagine hephaestion, esp look-wise?

Another question from Tumblr that yielded a long response of possible interest to others....

Apologies in advance for a long discussion, but…it’s a long discussion (with pretty pictures?).

With Hephaistion, we have only ONE statue that’s positively identified (e.g. he’s named). Several others are IDed as him by art historians, but it’s speculation, and alternative IDs have been offered. To complicate matters further, the one certainly identified sculpture is a dedicatory plaque (currently in the Thessalonike Museum, image below). These are often “idealized,” or even pre-carved to be selected by the purchaser. So we can’t be sure the image of Hephaistion on the plaque was what he actually looked like.

Of the images identified as him, but not certainly named, they fall into 3 basic categories. First, the hopelessly generic “young ephebe,” of which the Getty head is perfect, although the Getty head is, also, quite likely a FORGERY. Yet it’s still a good example of the “type.” If you compare this to generic Classical and early Hellenistic portraiture of young men in their late teens/early 20s, you’ll see there’s really nothing DISTINCTIVE (e.g., a likeness, or even a portrait) about it. So this isn’t what he looked like, either, issues of forgery aside.

Of the images identified as him, but not certainly named, they fall into 3 basic categories. First, the hopelessly generic “young ephebe,” of which the Getty head is perfect, although the Getty head is, also, quite likely a FORGERY. Yet it’s still a good example of the “type.” If you compare this to generic Classical and early Hellenistic portraiture of young men in their late teens/early 20s, you’ll see there’s really nothing DISTINCTIVE (e.g., a likeness, or even a portrait) about it. So this isn’t what he looked like, either, issues of forgery aside.

There are two other types, one a sort of oval face where (honestly) he looks sorta dim–the so-called “Demetrios” statue (which might, in fact, BE Demetrios Poliorketes), and another type that has a squarish jaw, and–of them all–seems the closest to a portrait. Whatever I said above about the Thessaloniki dedication, it does fall into that third category, which I call “Square-jaw Hephaistion.” Maybe that’s the one physical attribute we can give him? Incidentally, in the novel, I do describe him in several places as “square-jawed” in reference to that.

There are two other types, one a sort of oval face where (honestly) he looks sorta dim–the so-called “Demetrios” statue (which might, in fact, BE Demetrios Poliorketes), and another type that has a squarish jaw, and–of them all–seems the closest to a portrait. Whatever I said above about the Thessaloniki dedication, it does fall into that third category, which I call “Square-jaw Hephaistion.” Maybe that’s the one physical attribute we can give him? Incidentally, in the novel, I do describe him in several places as “square-jawed” in reference to that.

But the head that has always intrigued me most is the Prado Bronze. Today, it’s more commonly called Demetrios Poliorketes, but the head isn’t positively named. I’ve seen other portraits of Poliorketes, and I don’t think it’s the same person (hair motif aside). That doesn’t make it Hephaistion, of course, but there are arguments in favor of that identification. (But, alas, the jaw is mostly missing/smashed, so I can’t use the “square jaw” argument, ha.)

ERGO, the Prado Bronze remains my “Hephaistion head-cannon” from ancient statuary.

When Riptide was asking me for input for the cover images, I sent the above image-, as well as the Akropolis head for Alexander. They also asked about human models, and for Alexander, I didn’t have one. Yet L.C. Chase used the Akropolis head and worked some sort of wonderful voodoo to find that stock model because he knocked me on my ass. Whoever he is, he’s as close to a living model for Alexander that I’ve seen. Well, he’s too pretty (my Alexander is less attractive with a crooked nose), but, my God, THOSE EYES. Perfect.

When Riptide was asking me for input for the cover images, I sent the above image-, as well as the Akropolis head for Alexander. They also asked about human models, and for Alexander, I didn’t have one. Yet L.C. Chase used the Akropolis head and worked some sort of wonderful voodoo to find that stock model because he knocked me on my ass. Whoever he is, he’s as close to a living model for Alexander that I’ve seen. Well, he’s too pretty (my Alexander is less attractive with a crooked nose), but, my God, THOSE EYES. Perfect.

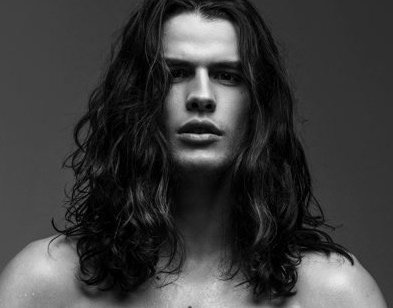

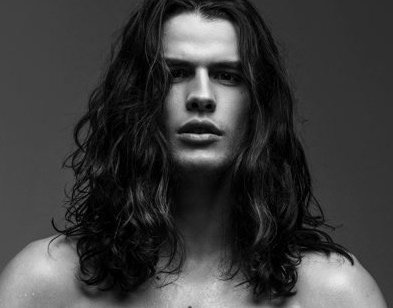

For Hephaistion, I went out to poke around a bit on the web, Prado Bronze in mind, and came across a Portuguese model named Vick Correia who, while not a dead ringer, I thought could be a younger version of the Prado. Correia’s mouth is wider, and his nose is not that no-dip-between-the-eyes blade of a Greek nose, but…it’s not a bad match. Plus he just happened to have long, curly hair and dark coloring. So, here’s the image of Correia that I first saw that made me go, “THERE HE IS!”

ANOTHER:

ANOTHER:

And Number 3 (that shows off the square jaw on the model)

And Number 3 (that shows off the square jaw on the model)

LC (the cover artist) couldn’t use Correia himself for book 2, for a variety of reasons (mostly related to COST), but she went hunting for as close as she could get, and it’s…not bad. I joke about him as “Vampire Hephaistion” but that’s partly a function of fixing the hair (it’s too, too straight) and using a “blue wash” on the color. Yet comparing the stock model next to Correia, it’s all right. (I’m actually more miffed at the ROMAN aquaduct in the background; if she’d asked, I’d have recommended using the Temple to Hephaistos in the Athenian agora…what a wonderful visual pun!)

LC (the cover artist) couldn’t use Correia himself for book 2, for a variety of reasons (mostly related to COST), but she went hunting for as close as she could get, and it’s…not bad. I joke about him as “Vampire Hephaistion” but that’s partly a function of fixing the hair (it’s too, too straight) and using a “blue wash” on the color. Yet comparing the stock model next to Correia, it’s all right. (I’m actually more miffed at the ROMAN aquaduct in the background; if she’d asked, I’d have recommended using the Temple to Hephaistos in the Athenian agora…what a wonderful visual pun!)

ANYway–and the hunt for living models aside–given the absolute paucity of certain images of Hephaistion, we have to turn to the literature, which is only a bit more help. There are two glancing descriptions of him, both found in Curtius, and another that’s a couple degrees removed but still might give us something.

ANYway–and the hunt for living models aside–given the absolute paucity of certain images of Hephaistion, we have to turn to the literature, which is only a bit more help. There are two glancing descriptions of him, both found in Curtius, and another that’s a couple degrees removed but still might give us something.

In Curtius book 3, we have our longest description of Hephaistion in any ancient source, and by “description,” I mean information about him, not just physical. The physical in the description is frustratingly brief. We’re told that he was “of larger physique” than Alexander, and attractive. The Latin usually translated as “taller” really just means “bigger” (and not as in fatter). But yes, “taller” would certainly work. A LOT of modern fiction authors do portray him as not only larger but taller, sometimes notably so. Yet keep in mind, Curtius is only comparing him to Alexander, who was apparently a bit short. So to be honest, he could have been of average height. (But where’s the fun in that? And I have a reason I think he was actually tall/large.)

Later in (I think? I’m doing this from memory) book 6 of Curtius, Hephaistion is compared to another Page who had (apparently) caught Alexander’s eye. The Page came off the worse for the comparison, being called perhaps as attractive, but not as viral, or manly.

But that’s all we got from the texts. It doesn’t add up to much.

In the book, I gave him dark coloring for an historical reason. First, I’d like to point out that the ancient Greeks were not as COLOR (hue) focused as we are. They elevated other qualities such as brightness, contrast, etc. Sometimes their terms for colors (frustratingly) throw together shades we consider distinct. Blue can be gray can be green. “Melas,” just means “dark,” so Melas Boukephalas could have been any shade from black to brown. Ergo, what color Alex’s hair was remains a debated point. He’s called ruddy-fair in complexion, but Plutarch never named his hair color. If the Istanbul sarcophagus can be believed (which, together with the Pella mosaics, I think it can be), Alexander was a *strawberry blond*. That would perfectly match a ruddy-fair complexion. But note hair color is our obsession, not theirs.

That said, I chose to give Hephaistion dark coloring because of his probable Ionic-Attic roots, which I’ve talked about before, and which I’m working on the finishing touches of a loooong-ass epigraphic/onomastic digital mapping project. BUT, Athenians and others of Ionic roots were described as darker than Dorians (or Aeolians). So Hephaistion’s hair/eyes in the novel are “black” (melas). That just means his hair is super dark espresso brown and his eyes are “cow eyes.” Btw, the Greek considered that a COMPLIMENT. Hera is described as having beautiful “cow eyes.”

Last … the whole SIZE thing. If you look at statuary of Alexander, he may have been of slightly less than average height, but he’s almost routinely shown to have broad shoulders and a wide chest. Maybe that’s idealization, too, but not necessarily. We know he fought in the front line, he was a runner, and he was just damn strong. So I’m inclined to think of him as shortish, but *broad*. (Not unlike my father, incidentally, who as a young soldier in WW II had a build very like Alexander’s in statuary. And my father, although only 5′8″ on a good day, was not only stronger than his taller contemporaries, but as tough as nails.)

So keep that in mind, when Curtius says Hephaistion is “larger in physique.” Alexander is not *small* or skinny. He’s just short.

Now, one LAST piece…Hephaistion is described as leading the “bodyguard” at Gaugamela. Lots of confusion over that. Doesn’t mean the Bodyguard (as in the 7-man Somatophylakes) but the bodyguard, the Hypaspists. And the Hypaspists were, under Philip, called the Pezhetairoi. The infantry were just “pezes” …footmen. Alex gave the name Pezhetairoi to the infantry as an honor, so needed a new name for the special crack unit his father created. He chose the term hypaspists, which meant “Shield bearer.” It’s an honorary term for (usually) the leader’s inner circle. Patroklos would have been a hypaspist for Achilles.

But we’re told something else about ol’ Phil’s Pezhetairoi. In selecting his crack troops, he didn’t use regional units (as usual) for regular sarissaphoi (infantry). INSTEAD, he selected men based on SIZE. The biggest and best fighters.

So if Hephaistion is leading the Hypaspists (=Pezhetairoi) at Gaugamela, and by leading, that’s probably the agema and (so Waldemar Heckel, and I think he’s right) the exclusive Hammipoi of the Hypaspists, HEPHAISTION WAS BIG GUY. Probably not only in height but in musculature.

In the novel, I still have him as a skinny late teen/early 20-something. He’s only 22 when Rise ends. But he’s still maturing. He’ll become sizable as the novel series progresses. :-)

Another question from Tumblr that yielded a long response of possible interest to others....

Apologies in advance for a long discussion, but…it’s a long discussion (with pretty pictures?).

With Hephaistion, we have only ONE statue that’s positively identified (e.g. he’s named). Several others are IDed as him by art historians, but it’s speculation, and alternative IDs have been offered. To complicate matters further, the one certainly identified sculpture is a dedicatory plaque (currently in the Thessalonike Museum, image below). These are often “idealized,” or even pre-carved to be selected by the purchaser. So we can’t be sure the image of Hephaistion on the plaque was what he actually looked like.

Of the images identified as him, but not certainly named, they fall into 3 basic categories. First, the hopelessly generic “young ephebe,” of which the Getty head is perfect, although the Getty head is, also, quite likely a FORGERY. Yet it’s still a good example of the “type.” If you compare this to generic Classical and early Hellenistic portraiture of young men in their late teens/early 20s, you’ll see there’s really nothing DISTINCTIVE (e.g., a likeness, or even a portrait) about it. So this isn’t what he looked like, either, issues of forgery aside.

Of the images identified as him, but not certainly named, they fall into 3 basic categories. First, the hopelessly generic “young ephebe,” of which the Getty head is perfect, although the Getty head is, also, quite likely a FORGERY. Yet it’s still a good example of the “type.” If you compare this to generic Classical and early Hellenistic portraiture of young men in their late teens/early 20s, you’ll see there’s really nothing DISTINCTIVE (e.g., a likeness, or even a portrait) about it. So this isn’t what he looked like, either, issues of forgery aside. There are two other types, one a sort of oval face where (honestly) he looks sorta dim–the so-called “Demetrios” statue (which might, in fact, BE Demetrios Poliorketes), and another type that has a squarish jaw, and–of them all–seems the closest to a portrait. Whatever I said above about the Thessaloniki dedication, it does fall into that third category, which I call “Square-jaw Hephaistion.” Maybe that’s the one physical attribute we can give him? Incidentally, in the novel, I do describe him in several places as “square-jawed” in reference to that.

There are two other types, one a sort of oval face where (honestly) he looks sorta dim–the so-called “Demetrios” statue (which might, in fact, BE Demetrios Poliorketes), and another type that has a squarish jaw, and–of them all–seems the closest to a portrait. Whatever I said above about the Thessaloniki dedication, it does fall into that third category, which I call “Square-jaw Hephaistion.” Maybe that’s the one physical attribute we can give him? Incidentally, in the novel, I do describe him in several places as “square-jawed” in reference to that.But the head that has always intrigued me most is the Prado Bronze. Today, it’s more commonly called Demetrios Poliorketes, but the head isn’t positively named. I’ve seen other portraits of Poliorketes, and I don’t think it’s the same person (hair motif aside). That doesn’t make it Hephaistion, of course, but there are arguments in favor of that identification. (But, alas, the jaw is mostly missing/smashed, so I can’t use the “square jaw” argument, ha.)

ERGO, the Prado Bronze remains my “Hephaistion head-cannon” from ancient statuary.

When Riptide was asking me for input for the cover images, I sent the above image-, as well as the Akropolis head for Alexander. They also asked about human models, and for Alexander, I didn’t have one. Yet L.C. Chase used the Akropolis head and worked some sort of wonderful voodoo to find that stock model because he knocked me on my ass. Whoever he is, he’s as close to a living model for Alexander that I’ve seen. Well, he’s too pretty (my Alexander is less attractive with a crooked nose), but, my God, THOSE EYES. Perfect.

When Riptide was asking me for input for the cover images, I sent the above image-, as well as the Akropolis head for Alexander. They also asked about human models, and for Alexander, I didn’t have one. Yet L.C. Chase used the Akropolis head and worked some sort of wonderful voodoo to find that stock model because he knocked me on my ass. Whoever he is, he’s as close to a living model for Alexander that I’ve seen. Well, he’s too pretty (my Alexander is less attractive with a crooked nose), but, my God, THOSE EYES. Perfect.

For Hephaistion, I went out to poke around a bit on the web, Prado Bronze in mind, and came across a Portuguese model named Vick Correia who, while not a dead ringer, I thought could be a younger version of the Prado. Correia’s mouth is wider, and his nose is not that no-dip-between-the-eyes blade of a Greek nose, but…it’s not a bad match. Plus he just happened to have long, curly hair and dark coloring. So, here’s the image of Correia that I first saw that made me go, “THERE HE IS!”

ANOTHER:

ANOTHER: And Number 3 (that shows off the square jaw on the model)

And Number 3 (that shows off the square jaw on the model) LC (the cover artist) couldn’t use Correia himself for book 2, for a variety of reasons (mostly related to COST), but she went hunting for as close as she could get, and it’s…not bad. I joke about him as “Vampire Hephaistion” but that’s partly a function of fixing the hair (it’s too, too straight) and using a “blue wash” on the color. Yet comparing the stock model next to Correia, it’s all right. (I’m actually more miffed at the ROMAN aquaduct in the background; if she’d asked, I’d have recommended using the Temple to Hephaistos in the Athenian agora…what a wonderful visual pun!)

LC (the cover artist) couldn’t use Correia himself for book 2, for a variety of reasons (mostly related to COST), but she went hunting for as close as she could get, and it’s…not bad. I joke about him as “Vampire Hephaistion” but that’s partly a function of fixing the hair (it’s too, too straight) and using a “blue wash” on the color. Yet comparing the stock model next to Correia, it’s all right. (I’m actually more miffed at the ROMAN aquaduct in the background; if she’d asked, I’d have recommended using the Temple to Hephaistos in the Athenian agora…what a wonderful visual pun!) ANYway–and the hunt for living models aside–given the absolute paucity of certain images of Hephaistion, we have to turn to the literature, which is only a bit more help. There are two glancing descriptions of him, both found in Curtius, and another that’s a couple degrees removed but still might give us something.

ANYway–and the hunt for living models aside–given the absolute paucity of certain images of Hephaistion, we have to turn to the literature, which is only a bit more help. There are two glancing descriptions of him, both found in Curtius, and another that’s a couple degrees removed but still might give us something.In Curtius book 3, we have our longest description of Hephaistion in any ancient source, and by “description,” I mean information about him, not just physical. The physical in the description is frustratingly brief. We’re told that he was “of larger physique” than Alexander, and attractive. The Latin usually translated as “taller” really just means “bigger” (and not as in fatter). But yes, “taller” would certainly work. A LOT of modern fiction authors do portray him as not only larger but taller, sometimes notably so. Yet keep in mind, Curtius is only comparing him to Alexander, who was apparently a bit short. So to be honest, he could have been of average height. (But where’s the fun in that? And I have a reason I think he was actually tall/large.)

Later in (I think? I’m doing this from memory) book 6 of Curtius, Hephaistion is compared to another Page who had (apparently) caught Alexander’s eye. The Page came off the worse for the comparison, being called perhaps as attractive, but not as viral, or manly.

But that’s all we got from the texts. It doesn’t add up to much.

In the book, I gave him dark coloring for an historical reason. First, I’d like to point out that the ancient Greeks were not as COLOR (hue) focused as we are. They elevated other qualities such as brightness, contrast, etc. Sometimes their terms for colors (frustratingly) throw together shades we consider distinct. Blue can be gray can be green. “Melas,” just means “dark,” so Melas Boukephalas could have been any shade from black to brown. Ergo, what color Alex’s hair was remains a debated point. He’s called ruddy-fair in complexion, but Plutarch never named his hair color. If the Istanbul sarcophagus can be believed (which, together with the Pella mosaics, I think it can be), Alexander was a *strawberry blond*. That would perfectly match a ruddy-fair complexion. But note hair color is our obsession, not theirs.

That said, I chose to give Hephaistion dark coloring because of his probable Ionic-Attic roots, which I’ve talked about before, and which I’m working on the finishing touches of a loooong-ass epigraphic/onomastic digital mapping project. BUT, Athenians and others of Ionic roots were described as darker than Dorians (or Aeolians). So Hephaistion’s hair/eyes in the novel are “black” (melas). That just means his hair is super dark espresso brown and his eyes are “cow eyes.” Btw, the Greek considered that a COMPLIMENT. Hera is described as having beautiful “cow eyes.”

Last … the whole SIZE thing. If you look at statuary of Alexander, he may have been of slightly less than average height, but he’s almost routinely shown to have broad shoulders and a wide chest. Maybe that’s idealization, too, but not necessarily. We know he fought in the front line, he was a runner, and he was just damn strong. So I’m inclined to think of him as shortish, but *broad*. (Not unlike my father, incidentally, who as a young soldier in WW II had a build very like Alexander’s in statuary. And my father, although only 5′8″ on a good day, was not only stronger than his taller contemporaries, but as tough as nails.)

So keep that in mind, when Curtius says Hephaistion is “larger in physique.” Alexander is not *small* or skinny. He’s just short.

Now, one LAST piece…Hephaistion is described as leading the “bodyguard” at Gaugamela. Lots of confusion over that. Doesn’t mean the Bodyguard (as in the 7-man Somatophylakes) but the bodyguard, the Hypaspists. And the Hypaspists were, under Philip, called the Pezhetairoi. The infantry were just “pezes” …footmen. Alex gave the name Pezhetairoi to the infantry as an honor, so needed a new name for the special crack unit his father created. He chose the term hypaspists, which meant “Shield bearer.” It’s an honorary term for (usually) the leader’s inner circle. Patroklos would have been a hypaspist for Achilles.

But we’re told something else about ol’ Phil’s Pezhetairoi. In selecting his crack troops, he didn’t use regional units (as usual) for regular sarissaphoi (infantry). INSTEAD, he selected men based on SIZE. The biggest and best fighters.

So if Hephaistion is leading the Hypaspists (=Pezhetairoi) at Gaugamela, and by leading, that’s probably the agema and (so Waldemar Heckel, and I think he’s right) the exclusive Hammipoi of the Hypaspists, HEPHAISTION WAS BIG GUY. Probably not only in height but in musculature.

In the novel, I still have him as a skinny late teen/early 20-something. He’s only 22 when Rise ends. But he’s still maturing. He’ll become sizable as the novel series progresses. :-)

Published on August 26, 2019 22:13

August 21, 2019

Alexander, Hephaistion, and the Problem of Our Sources

Anonymous asked (on Tumblr): I just finished ‘Becoming’ and I absolutely loved it! I just wondered if you believe that AtG and Hephaistion continued their romantic relationship throughout their lives or if you think they let that side of their friendship go as they got older as was more common at the time? Anyway! I absolutely loved ‘Becoming’ and I can’t wait to read ‘Rise’!

I’m guessing you’re asking about the historical people, as opposed to the fictional characters? I do hope/plan to continue the Dancing with the Lion series, and in it, yes, they will remain romantically involved. Whether or not future novels are bought, however, rests on how well Becoming and Rise do. (So if you want more, get the word out and post reviews. *grin*)

Yet, with regard to the historical men, I think it’s very hard to know whether they remained sexual partners as adults. And the reason it’s hard to know involves the difficulty of our surviving sources.

As soon as historians start talking SOURCES, a lot of folks tune out. It’s BORING. *grin* But in order to give an honest answer, I kinda have to Go There.

First, let me give the TL;DR version. If they were still sexually involved as adults, I suspect it was quite occasional. And the fact it was quite occasional (if at all), may be why we don’t hear anything about it in the sources (discussion to follow). After all, they were both extremely busy men with duties and responsibilities that sometimes kept them apart for months. If they were still sexually/romantically involved, they had what we’d today call a long-distance relationship at points…and without the benefit of cell phones.

It may have been a gradual “weaning” from each other, rather than anything sharp. So they may have been lovers as teens, then over time, each took younger beloveds, and finally, wives—all while remaining emotionally very, very close. (Although I suspect that, like any friendship OR love affair, they had ups-and-downs, fights and reconciliations.)

Now, here’s why the TL;DR summary above gets a big fat label: “SPECULATION.”

The sources are the only way we know anything about the past, and if they can’t be trusted, or at least not trusted in toto, we have a Really Big Problem. So let me lay it out.

Before I do, however, I want to remind readers that I DO think Alexander and Hephaistion were lovers, at least in their youth. But no, it’s not “obvious.” Theirs wasn’t a world especially reticent about same-sex affairs (*cough* see below), even if post-Christian, modern historians had trouble with it until the last 40 years or so. So if the (surviving) ancient authors don’t talk about them as lovers, even while discussing other same-sex pairs in the same damn text, we have to ask…why? One very real possibility is that they didn’t talk about them as lovers because they weren’t. Full stop. There could have been other reasons (I think there were), but let’s not flinch from being honest, here.

So…back to our Persnickety Sources.

So…back to our Persnickety Sources.

First, nothing has survived that Alexander wrote himself. We have a couple public inscriptions, but not one piece of writing, even a letter, from Alexander. (Any surviving letters are quoted in later sources, and probably aren’t real.*)

Second, nothing has survived written by anyone who actually knew Alexander, or even lived when he did, except forensic speeches from Athenian demagogues who mostly hated him (and weren’t writing histories anyway). One may as well trust Demosthenes on Philip.

The sources we do still have used histories written by those who knew Alexander, such as Ptolemy, Aristobulos, Nearchos, Marsyas, and even the court historian, Kallisthenes. They also used other texts of dubious worth, such as Onesikritos, who was made fun of even in his own day for writing “historical fiction.” And sometimes our later authors were using texts who, themselves, were using earlier texts. So we’ve got three (or more) layers, not just two!

Third, we have not just layers of sources, but layers in the CULTURE behind those sources.

The first layer is, of course, Macedonian. How did the Macedonians themselves view Alexander? We don’t know—not truly. Nothing survives from a Macedonian source, such as Marsyas or Ptolemy. (Some of you “in the know” might be thinking, But Polyaenus! No. Polyaenus lived 500 years after ATG; that was a very different Macedonia. [Yes, I used the Latin spelling, as he was Roman. ;p])

The second layer is Greek, but we have to qualify this. Layer 2.0 is Greece of the 4th century, especially Athenian reactionism, writing about the emerging Macedonian kingdom. There could be huge cultural differences even among Greek city-states. Case in point: Athens vs. Sparta. Greeks didn’t always understand Macedonians (sometimes, I swear, on purpose).

BUT we also have the increasingly homogenized Hellenistic world of the Successors, which was sorta like when you throw in a bunch of different colored shirts and wash them in hot water. You get a color-bleeding mess. Your red shirt (Attic-Ionic) might have a big blue streak (Doric) on it now. That’s sort of what happened to Greek culture as the Hellenistic era progressed. Lots of bleed. This had begun prior to Alexander, but he accelerated it like kerosene on a trash fire. We can call that Greek Layer 2.1, or something.

Then we have the Romans, and their culture, which, if similar to Greek, definitively wasn’t Greek in key ways. All our surviving sources were written as the Republic was collapsing and the Empire emerging, and by that point, Greece was a Roman province.

Again, we’ve got two groups here: Greeks living under Roman rule, such as Plutarch, Diodorus, and Arrian—who wrote in Greek—and then Roman authors such as Curtius, and later Justin, who wrote in Latin. But the Greeks under Rome shouldn’t be conflated with Athenians in ATG’s own day, or even under the Successors. The culture evolved and took on Roman shadings.

So that’s not just layers of sources, but layers of cultures trying to understand what people who lived a hundred or two hundred or three hundred years before them thought/believed.

Ergo, are we hearing what Alexander (or anybody else around him) really thought or intended? Or just what writers of the Second Sophistic (such as Plutarch) wanted him to model? Or how even later authors, such as Arrian, wanted to use him to flatter his patron, Hadrian?

What’s Roman, what’s Greek, and what’s Macedonian? Can we tease that out? I’d say it’s damn tricky, and often, flat impossible—although unlike some of my colleagues, I don’t believe it’s all Roman overlay. That goes too far in the other direction, IMO.

Last, we have several authors who weren’t writing about Alexander specifically, but have bits of Alexander lore embedded in their texts: Athenaeus’s “Supper Party,” or Polyaenus’s “Strategems,” or even Plutarch’s “Moralia,” just to name three.

Among these, especially later, we have authors writing material they (or later readers) tried to pass off as written by earlier authors. We often refer to these authors with the preface “Pseudo-” as in “Pseudo-Kallisthenes.” It was NOT written by Kallisthenes, but was later attributed to him.

So, now you have some idea of why Alexander historians want to pull our hair out!

But I detail that to explain why it’s so hard for me to give you any clear answer about whether Alexander and Hephaistion remained lovers as adults. Or even if they were lovers at all.

In none of our five primary histories of Alexander, nor in Plutarch’s other stuff, nor Athenaeus, etc. is Hephaistion ever called Alexander’s lover. This includes sources that do mention with apparent unconcern other pairs of male lovers. So this isn’t “the love that dared not speak it’s name.” The Greeks were pretty okay with talking about their boyfriends.

There could be OTHER reasons for deep-sixing mention of Hephaistion and Alexander as lovers, mostly having to do with status (some of which I touched on in the novels), yet the lack of clear affirmation is a problem. The only mentions we do have come from late sources, one of which belongs to that category of “pseudo-” authors I mentioned: Pseudo-Diogenes (in Aelian), as well as Arrian recording the Stoic Epiktatos. The philosophers are trying to make a point about the dangers of giving in to physical desire, so it’s hard to know how much credit to give these references.

Thus, we’re left with little besides the indirect (e.g., the Achilles-Patroklos allusions, etc.). Those have their own problems, which I’ll not go into now, as I’ve already written a small essay.

One potential reason for a lack of mention in our surviving sources is that any sexual love affair had been a product of their youth. What remained was a fiercely deep and passionate devotion. Before you pooh-pooh that—Of course they were still having sex!—consider modern marriages that have lasted for decades but no longer include sexual activity, at least between the married partners. Don’t be sucked in by Romance novel tropes.

When I was doing bereavement counseling (et al.), I ran into all sorts of arrangements that married couples made across time. Some marriages break up when the partners stop being sexually attracted to each other, and “cheat.” But others don’t, because it’s not “cheating” if it’s mutually agreed to. Or in some cases, the partners simply lost interest in sex as they aged…but didn’t fall out of love with each other. So they might have sex once a year? Maybe? That was enough. Or they had sex on the side, with permission. People don’t fit into boxes well, IME. Honesty was the hallmark of marriages that lasted even when they weren’t still having sex. I’ve known of marriages where the couples had stopped having sex years ago, but when one of them died, the other was completely devastated because of the enormous EMOTIONAL investment. I think that’s what hit Alexander when Hephaistion died. Maybe they were still having sex, at least once in a blue moon. Maybe they weren’t. That didn’t matter.

LOVE is deeper than sex, by a long shot. Which is why the Greeks counted PHILIA (true friendship) as the superior love to eros (desire).

So whether Alexander and Hephaistion were still sexually involved—or had ever had sex—doesn’t reflect the depth of their love for each other. We might not be told by the sources that they were lovers, physically, either as youths or continuing into adulthood. But the sources are abundantly clear that they loved each other best of all. When Hephaistion died, Alexander followed him about 10 months later.

(Final note: what I intend to do in the series, going forward, is a bit different from what I described here, but that’s why I specified this involves the historical men, not necessarily my fictional characters.)

*My reference to quoted material, such as letters—or speeches—not being real: it was a common practice in the ancient world for the author of histories to just MAKE SHIT UP. It was all about showing off one’s own rhetorical skills. I think, in a lot of cases, we are probably getting at least the gist of what was said. But NEVER, EVER, EVER trust the “transcription” of an ancient speech…unless it was actually recorded later by the author. So, say, Demosthenes’ Philippics are probably a cleaned up version of the speeches he delivered. But Alexander’s “Speech at Opis” is NOT what Alexander actually said.

I’m guessing you’re asking about the historical people, as opposed to the fictional characters? I do hope/plan to continue the Dancing with the Lion series, and in it, yes, they will remain romantically involved. Whether or not future novels are bought, however, rests on how well Becoming and Rise do. (So if you want more, get the word out and post reviews. *grin*)

Yet, with regard to the historical men, I think it’s very hard to know whether they remained sexual partners as adults. And the reason it’s hard to know involves the difficulty of our surviving sources.

As soon as historians start talking SOURCES, a lot of folks tune out. It’s BORING. *grin* But in order to give an honest answer, I kinda have to Go There.

First, let me give the TL;DR version. If they were still sexually involved as adults, I suspect it was quite occasional. And the fact it was quite occasional (if at all), may be why we don’t hear anything about it in the sources (discussion to follow). After all, they were both extremely busy men with duties and responsibilities that sometimes kept them apart for months. If they were still sexually/romantically involved, they had what we’d today call a long-distance relationship at points…and without the benefit of cell phones.

It may have been a gradual “weaning” from each other, rather than anything sharp. So they may have been lovers as teens, then over time, each took younger beloveds, and finally, wives—all while remaining emotionally very, very close. (Although I suspect that, like any friendship OR love affair, they had ups-and-downs, fights and reconciliations.)

Now, here’s why the TL;DR summary above gets a big fat label: “SPECULATION.”

The sources are the only way we know anything about the past, and if they can’t be trusted, or at least not trusted in toto, we have a Really Big Problem. So let me lay it out.

Before I do, however, I want to remind readers that I DO think Alexander and Hephaistion were lovers, at least in their youth. But no, it’s not “obvious.” Theirs wasn’t a world especially reticent about same-sex affairs (*cough* see below), even if post-Christian, modern historians had trouble with it until the last 40 years or so. So if the (surviving) ancient authors don’t talk about them as lovers, even while discussing other same-sex pairs in the same damn text, we have to ask…why? One very real possibility is that they didn’t talk about them as lovers because they weren’t. Full stop. There could have been other reasons (I think there were), but let’s not flinch from being honest, here.

So…back to our Persnickety Sources.

So…back to our Persnickety Sources.First, nothing has survived that Alexander wrote himself. We have a couple public inscriptions, but not one piece of writing, even a letter, from Alexander. (Any surviving letters are quoted in later sources, and probably aren’t real.*)

Second, nothing has survived written by anyone who actually knew Alexander, or even lived when he did, except forensic speeches from Athenian demagogues who mostly hated him (and weren’t writing histories anyway). One may as well trust Demosthenes on Philip.

The sources we do still have used histories written by those who knew Alexander, such as Ptolemy, Aristobulos, Nearchos, Marsyas, and even the court historian, Kallisthenes. They also used other texts of dubious worth, such as Onesikritos, who was made fun of even in his own day for writing “historical fiction.” And sometimes our later authors were using texts who, themselves, were using earlier texts. So we’ve got three (or more) layers, not just two!

Third, we have not just layers of sources, but layers in the CULTURE behind those sources.

The first layer is, of course, Macedonian. How did the Macedonians themselves view Alexander? We don’t know—not truly. Nothing survives from a Macedonian source, such as Marsyas or Ptolemy. (Some of you “in the know” might be thinking, But Polyaenus! No. Polyaenus lived 500 years after ATG; that was a very different Macedonia. [Yes, I used the Latin spelling, as he was Roman. ;p])

The second layer is Greek, but we have to qualify this. Layer 2.0 is Greece of the 4th century, especially Athenian reactionism, writing about the emerging Macedonian kingdom. There could be huge cultural differences even among Greek city-states. Case in point: Athens vs. Sparta. Greeks didn’t always understand Macedonians (sometimes, I swear, on purpose).

BUT we also have the increasingly homogenized Hellenistic world of the Successors, which was sorta like when you throw in a bunch of different colored shirts and wash them in hot water. You get a color-bleeding mess. Your red shirt (Attic-Ionic) might have a big blue streak (Doric) on it now. That’s sort of what happened to Greek culture as the Hellenistic era progressed. Lots of bleed. This had begun prior to Alexander, but he accelerated it like kerosene on a trash fire. We can call that Greek Layer 2.1, or something.

Then we have the Romans, and their culture, which, if similar to Greek, definitively wasn’t Greek in key ways. All our surviving sources were written as the Republic was collapsing and the Empire emerging, and by that point, Greece was a Roman province.

Again, we’ve got two groups here: Greeks living under Roman rule, such as Plutarch, Diodorus, and Arrian—who wrote in Greek—and then Roman authors such as Curtius, and later Justin, who wrote in Latin. But the Greeks under Rome shouldn’t be conflated with Athenians in ATG’s own day, or even under the Successors. The culture evolved and took on Roman shadings.

So that’s not just layers of sources, but layers of cultures trying to understand what people who lived a hundred or two hundred or three hundred years before them thought/believed.

Ergo, are we hearing what Alexander (or anybody else around him) really thought or intended? Or just what writers of the Second Sophistic (such as Plutarch) wanted him to model? Or how even later authors, such as Arrian, wanted to use him to flatter his patron, Hadrian?