Jeanne Reames's Blog, page 2

January 29, 2021

Map-Making as World-Building

Quiz any of my former students, and they can probably confirm my love for maps. My most recent academic article heavily used digital mapping to demonstrate my primary argument. In virtually all my classes, I state (multiple times) that it’s hard to overemphasize the importance of geography on history, particularly in antiquity. Where people build cities, where they make roads, where they sail and trade, what sort of agriculture they could pursue…all are shaped by the land itself.

That same is true for historical fiction, whether genre or not. A recent article in Writer’s Digest gave me Thinky-Thoughts not just about maps, but how I, personally, utilize them in story construction. Perhaps it will be of interest for others, whether readers or (especially) writers, even if you have no intentions of publishing.

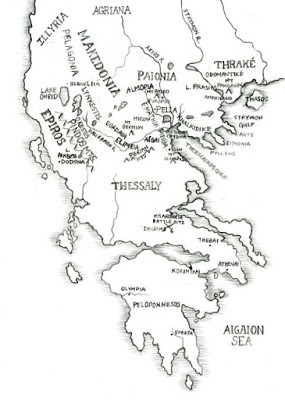

As some of you may have noticed, if you read the “fine print,” the lovely map at the front of Becoming(which I wish had also been at the front of Rise) was drawn by my very talented niece, Selena Reames, a professional artist. How cool to have two Reameses in one book? She also put up with her aunt’s rather exacting placement…”No, that’s too far west…that’s too far south.” Ha. Yet working with her helped me understand how much artistry goes into map-making. (Besides in the front of the first book, the map can be found on my website dedicated to the Dancing with the Lion series.)

Although a lot of action in both novels takes place in only three places (Pella, Mieza, and Aigai), a number of other cities and sites do show up, especially in the second book (which is why I wish the map had been put there too). Some readers don’t care, maybe a lot of readers don’t care, but it’s important to know how far away these various places are, which affects how quickly people can move between them.

Maps matter to timing events. To that end, let me share a site that I make copious use of, both for regular historicals as well as historical fantasy.

ORBIS: the StanfordGeospacial Network Model of the Roman World (Use Chrome for best results)

Yes, this is aimed at the Roman world, but can be used for other eras in the Mediterranean, and other areas notin the Mediterranean. While improvements to boats and wagons—not to mention those famous Roman roads—did affect travel speed, as well as where people could go, you can still get a ballpark estimate. Furthermore, this site allows one to choose method of transport (land, ship, riding, walking, cart, etc.), and speed (military, normal/trade, etc.). One may have to think about changes to place names, etc., but a writer can waste…er, spend a lot of time playing there.

It can ALSO be used for historicals and fantasy set in pre-modern periods, even if not in the Mediterranean, or if placed in one’s own world. Analogize. Look at miles/kilometers and terrain. Travel in mountains or forest/jungle/desert is obviously tougher than through fields, and paved roads are better than dirt, which are better than goat tracks. You also need to think about sailing seasons, and not only in cold environments. The threat of storms can make travel impossible for parts of a year.

And don’t forget it’s all general. If you’re traveling by horse with members in the party who aren’t used to day-long riding, that will slow down everybody. An inexperienced rider doesn’t just hop on a horse and go for hours. It’s not a car. I used to be a decent rider as a kid and teen, so I knew how to sit a horse, move with it, etc. But I hadn’t been riding in over two decades when I went for a 2-hour trip on Naxos, and boy, was I sore after! Experience, recent time on horseback, even age matter.

Also, ancient wagons weren’t equipped with shock absorbers, so well-maintained roads sped up travel, while poor roads slowed it down—could even halt it entirely if a wheel got stuck in a rut, came off, the axel broke…not to mention the “stuff” in the wagon (if hauling breakable objects, such as pots) had better be well-packed with straw.

With an historical such as Dancing with the Lion, the map is set. We might be able to add a few fictional places, but for the most part, we describe real space at a particular point in history.

When writing fantasy, even fantasy heavily influenced by real history, maps are unmoored and we have more freedom. Yet that can feel overwhelming to writers who don’t spend as much time as I do with maps (and climate and agriculture and battlefields, etc.).

Yet making maps—as that Writer’s Digest article describes—can help an author think about her story, even shape the plot.

My current MIP (monster-in-progress) is a projected 4-book epic fantasy series with the working title Master of Battles. When I describe it, I’m always torn on HOW to describe it. The elevator pitch is, “A fugitive shaman fleeing his wicked teacher falls over a balcony into the bedroom of a quirky prince, setting off a prophecy that will change their world.” But what I REALLY want to tell you about it the super-cool world. I not only threw up the historical pieces (events/kingdoms) but also the geographical pieces, to see where they landed.

I steal a lot from history, then hang intentionally obscure or less-known names on places and peoples, which will likely amuse Those Who Recognize but mean nothing to those who don’t. Yet I’ve mixed up the time eras, and geography too.

Creating the map was part of the fun, and that, in turn, yielded different possible outcomes.

First, if you look at our globe, you’ll notice landmasses bulk in the northern hemisphere. We’re “top heavy.” I flipped that; their world is “bottom heavy.” I also moved whole continents, in addition to changing the size of them, in order to alter outcomes. Among the biggest reasons for the massive death among indigenous populations when Europeans showed up en masse to the Americas owed to a lack of disease resistance. I think most people are aware of that; what most aren’t aware of is why.

Domesticated animals. As Coronavirus has taught us, disease can jump from animals to us. The Americas did not have horses, cattle, pigs, goats, sheep…all were imported after 1492 as part of the “Columbian Exchange.” (No really, it’s true; most folks don’t realize that.) In return, we gave Europe key crops (maize, potatoes, peppers, squash, chocolate, tobacco). But American natives just had far less resistance to small pox, etc…diseases that Europeans, Asians, and Africans had developed immunity to millennia before.

What if the Americas weren’tisolated, but had those domesticated animals earlier, and thus, disease resistance? Might make conquest harder. Also, landscape affects how warfare is conducted. As Alexander discovered in India, the phalanx doesn’t do well in a jungle, nor does cavalry. Imagine the Macedonian pike- and cavalry army trying to fight in the Amazon.

As much as I love geography and its impact on history, we must beware of geographical determinism, which is a form of proto- and not-so-proto-racism. While geography affects what we develop (sometimes for surprising reasons), as I constantly tell my students, human beings are enormously creative. If we don’t have X available, we develop Y instead, or we just figure a work-around to not having X. Therefore “civilization” should never be defined by what any given group of people has or doesn’t have, technologically speaking. The term “civilization” is problematic in the first place, but I do my best to uncouple it from specific technology (be it the wheel, iron-working, gun powder, etc.).

Take something as “basic” as writing. What is “writing” except “representative reality”? A symbol (or group of them) stands in for a word. The earliest “Old World” writing systems (Sumerian, Egyptian, Harappan, Chinese) developed symbols that were drawn/incised on a flat surface, be it clay, papyrus, stone, silk… But what if the “symbol” isn’t a mark? What if the symbol is, instead, a system of knots tied in a cord? Isn’t that also “representative reality”?

Hello, South American quipu. Or the wampum of the North American Great Lakes people. (And yes, the Chinese used knots for record-keeping, as did the Hawaiians.)

Hello, South American quipu. Or the wampum of the North American Great Lakes people. (And yes, the Chinese used knots for record-keeping, as did the Hawaiians.) We have to remember to keep our minds open.

Back to my games with maps and continents.

I moved South America across to, roughly, where Africa is—only there’s no isthmus and North America smooshed up all along the southern side (so it’s essentially one big wide continent not unlike Eurasia). Then I moved Africa to where South America is, and the northern areas are a series of larger and smaller island masses (think Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines). Europe is truncated all along the north, there’s not much to Siberia at all, and the Mediterranean/Black Sea basins are longer, divided into two seas split by a sizeable archipelago. There are no Himalayas, so China was never cut off from Persia and India. In their world, the really massive empire (Shim) lies in the east, not the west (Rome). And oh, yeah, there’s a huge-ass rain forest on the southern continent full of Very Different People. And different trade.

That’s just a few of the changes I made.

Play with geography, and completely change history.

To make it more fun, on their world, not one but two sub-species of humanity survived: Aphê and Ensāni…one of whom has a functional prehensile tail. (Because who among us has never wished for a third hand?)

Hopefully, that makes readers curious about the Master of Battles series. But also, I hope it inspires other writers to think about the huge impact that geography—and therefore climate, agriculture, contact/trade, and even disease—can have on world-building, and plotting.

January 1, 2021

What if Alexander IV Escaped Murder?

Another Tumblr question, this time from user Shininglightofdarkness. Sharing it because part of my reply wandered off into a "What If" that, who knows, maybe some aspiring author wants to try. (I don't.) After all, not many periods of history are as crazy-fun as the Successor Wars...

If Alexander lived long enough to see Alexander IV grow up, what sort of father do you think he would have been? For that matter, what do you think Alexander IV was like? I imagine his childhood must have been very stressful, if not outright traumatic.

What sort of father might Alexander have been? I fear, like his own father, largely absent. Especially when his children were young. I don’t think being a father would have slowed down his travel any, and unlike Philip, there wasn’t really a historic “Pella” in his new kingdom for him to come back to.

Once the boy got older, I think he’d have done what his father did and get him a pet philosopher (perhaps Aristotle if the latter was still alive, but in history, he died just one year after Alexander himself, so probably one of Aristotle’s students). Then after he’d spent a few years on an education, Alexander would have taken him campaigning (again, much as Philip did with him).

I do suspect he’d have seen the boy (or boys) periodically, and probably showered them with presents from “strange lands.” But I just don’t think he’d have been around a lot, which might’ve been a good thing, as I can’t imagine that he wouldn’t have held a high bar--again, not unlike his own father.

As for the life Alexander IV actually had…probably very sad. He’d have been at once spoilt and completely overshadowed by his father’s legend. If growing up the son of a living legend (Philip) was hard on Alexander, imagine growing up the son of a dead one? And people tended either to love and admire his father, or hate him. The last years of his life, he spent a prisoner under a man who’d really hated him. I can’t help but think Kassandros took that out on Alexander IV, at least in private.

Now here’s an interesting “what if” story…

What if Roxane realized their time was up, but found a way to smuggle him out so he escaped? Meanwhile, Kassandros found a convenient substitute to kill, to prevent Alex IV claiming his throne…and the Successors were complicit (or at least happy to accept Kassandros’s claims), as they’d prefer him to be and stay dead.

What would the son of Alexander the Great do with himself if he could never be king?

There’s a potential novel for you. Would he feel eternally resentful? Or grateful to his mother (who, let’s say, stayed behind to cover his escape and died after all)? With grandmother dead a some years earlier, would he try to flee to his Aunt Kleopatra in Epiros? Would he be angry he wasn’t king? Or relieved? A lot would depend on what sort of basic personality he had. But it’s a fun “what if?” to consider.

December 30, 2020

Writing Historical Fiction (Well)

Another Tumblr anonymous query whose answer I'm also posting here as of possible wider interest:

"What advice would you give to someone who wants to write about Alexander?" Sorry I didn't clarify, I was thinking of writing a fictional novel (but do not plan to publish it, lol)

Well, if you’re just writing for yourself with no plans to publish, you don’t have to worry about constraints like wordcount and publishability. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to sell mainstream historicals. Selling a genre historical is easier (historical fantasy, historical mystery, historical romance). But there’s a reason it took me 30 years to get Dancing with the Lion into print. Yes, some of that time I was actually writing it, but much more was devoted to finding a market for it, and notice that I did, finally, have to sell it as genre even though it isn’t really. (It was that or shelve it forever.)

Yet if you’re asking for my recommendations, I assume you want to write something that’s marginally readable. Ergo, what follows is general advice I’d give anybody writing historical fiction.

For historicals, one must keep track of two things simultaneously: telling a good story, and portraying history accurately enough. It’s possible to do one well, but the other quite badly.

First, let’s look at how to write a good story.

There are two very basic sorts of stories: the romance, and the novel. Notice it’s romance small /r/. A romance is an adventure story; in romances, the plot dominates and characters serve the plot. A novel is character-driven, so plot events serve character development. Dancing with the Lion is a novel.

Once you’ve decided which of those you’re writing, you have a better handle on how to write it. You also need to know where you’re going: what’s the end of the story? What are the major plot points? Writers who dive in with no road map tend to produce bloated books that require massive edits. That said, romances will almost always be faster paced, in part because “what’s happening” drives it. Whereas in novels, the impact of events on characters drives it. Exclusive readers of romances are rarely pleased by the pacing of novels. They’re too slow: “Nothing is happening!” Things are happening, but internally, not externally.

Yet pacing does matter. Never let a scene do one thing when it can do three.

You will want to pay attention to something called “scene and sequel.” A “scene” is an event and a “sequel” are the consequences. So let’s say (as in my current MIP [monster in progress]) you open with a fugitive from the city jail racing through the streets with guards following: he leaps the wall of a rich man’s house and ends up in the bedroom of a visiting prince. That’s the scene. The sequel is the fall-out. (House searched, prince hides fugitive, prince gets fugitive to tell him why he’s running.) Usually near the end of the sequel(s) to the first scene, you embed the hook to the next (a slave of the rich man has been found murdered outside the city walls). The next scene concerns recovering the body and what they discover (then fall-out from that). Etc., etc., etc.

That’s how stories progress. Or don’t progress, if the author can’t master scene-sequel patterns.

It also means—again—you need to know where you’re going. Outlines Are Your Friends. But yes, your plot can still take a sharp left-hand turn that surprises you…they almost always do.

When I sat down to write Dancing with the Lion, I knew three things:

1) I wanted to write about Alexander before he became king.

2) I wanted to explore his relationship with Hephaistion.

3) I especially wanted to consider how both became the men they’d did.

With those goals in mind, I could frame the story. Because I always intended Hephaistion to be as important as Alexander, the novel opens in his point-of-view to establish that. And because I didn’t want to deal with Alexander as king, the novel had to end before he became one. History itself gives a HUGE and obvious gift in the abrupt murder of Philip. Where to openwas harder to decide, but as I wanted to explore the boys’ friendship and its impact on their maturation into men, I should logically begin with their meeting, and decided not to have them meet too young. From there, I spun out Hephaistion’s background, and his decision to run away from home to join the circus, er, I mean Pages.

December 27, 2020

Traditional Offices at the Macedonian Court: Hetairos, Page, Somatophylax

On Tumblr, I received the following two anonymous queries (maybe from the same person, as they seemingly relate). I chose to post the answers here, as well, as figuring out the finer points of these offices can be problematic. Wikipedia entries are not to be trusted.

----------------

Do we know for certain when Hephaistion became Somatophylakes? I read somewhere that it might have been after the "naming of the Sidonian King". Do you think there was a specific reason behind his appointment (some military or administrative achievement)?

Sorry, this might be a bit dumb to ask but... what exactly did the rank "Bodyguard" (Somatophylakes) entail? They had military positions in addition to their "Bodyguard" station, but... where they in charge of Alexander's security? How exactly did they get this title and was it the "highest rank" they could get? I get so confused between the "Companion" and "Bodyguard" terms.

----------------

The best way to answer this question is to talk about the roles and offices at the Macedonian court more broadly. I will say at the outset there’s no universal agreement on these matters. I’m detailing what I find to be most logical, based on the evidence we have. Argead Macedonian court politics is “my thing.” When I get specific about what I do, it’s court dynamics and prosopography. People often refer to me as the Hephaistion specialist, and that’s fair enough, but my real expertise is broader; he’s just part of that larger web.

As we have no surviving source that clearly outlines what these offices entailed, we must reconstruct them from implication embedded in what our sources do tell us. To complicate things, common nouns are sometimes used generically, sometimes titularly.

Let’s begin with the most basic, and probably oldest rank: Hetairos (Hetairoi, pl.).

The word hetairos just means “companion.” Back at least into the early iron age, Hetairos was used as a generic title for the land-owning elite, as they were the fighting/hunting/drinking companions to royals. In Macedonia, the full title was Basίlikoi Hetaίroi. We cap and don’t italicize foreign words when used titularly. So hetairos (“He’s my traveling companion.”) but Hetairos (“He’s one of the King’s Companions from Almopia.”). But this mixed usage can cause problems in identification.

Similarly, a small circle of personal advisors around the king were called Philoi: Friends (Philos, sing.). As with Hetairos, it had titular import. (Not unlike the Roman emperor’s Amici.) Again, when is a friend a Friend? That matters for someone like Hephaistion. He was a friend of Alexander’s in youth, but by the end of Alexander’s reign, he’s also a Friend of the king.

Anyway, in Maceedon, being an Hetairos was largely hereditary, linked to a festival (probably held in spring) called the Hetairideia. (If you’ve read Dancing with the Lion, I mention it a few times; Hephaistion’s Single Combat competitions are set during the Hetairideia.) Unfortunately, most of what we know about it comes from the Antigonid era (post-Alexander), not the earlier Argead, although it probably dates back into the dim recesses of Macedon’s formation.

If the rank of Hetairos was traditionally hereditary, it was also in the gift of the king, who was bound to his Hetairoi by oaths, renewed each year. So if the son or sons of an Hetairos usually became Hetairoi in turn (thus Hephaistion takes his father’s cloak in Rise), the king maintained the right to strip the title, or make new Hetairoi. The latter was more common than the former. Archelaos famously made Euripides an Hetairos and Philip gave it to several Greeks, as did Alexander. If I recall right, Alexander anointed Darius’s brother Oxyathres a Hetairos too. These appointments probably went along with land grants, at least down to Philip. When he took Amphipolis, he gave out a lot of land to Hetairoi, some of whom would already have had land, but some were non-Macedonians ethnically, such as Nearchos.

[image error]All that dates back to the original connection of Hetairos as land-owners who agreed to fight for the king, mostly on horseback. The Macedonian lowland was (and is) horse country, as were areas of the highlands, especially Elimeia and Eordia with their wide mountain valleys. Elimeia had a crack cavalry better than the lowlands at several points in history. Remember, those upper Macedonian cantons were initially independent kingdoms. It was Philip who bound the highlands securely into the larger Macedonian orbit.

Airopos of Lynkestis (but not his sons) is an example of a nobleman stripped of his title, and exiled by Philip sometimes during the campaigns in the Greek south, whereupon he fled to Athens. That’s one reason why the Lynkestian brothers were implicated in Philip’s murder later. To have the title removed would have been a HUGE blow to their father’s timē(personal, public honor). Murder was, indeed, a possible response; it was that serious. (It’s likely that, when Philip exiled Nearchos, Ptolemy, Harpalos, Erigyios, and Laomedon after the Pixodaros Affair he also took their titles too, but Alexander would have returned them when he recalled them.)

So Hetairoi made up the wealthy landowning class. We’re not sure how many there were. Gene Borza estimated them at about 100; the stone row of seats at the Aigai theatre (with the king’s “throne” in the middle) was likely for Hetairoi, and about 100 butts can fit on it. LOL. Sons of living Hetairoi would be “Hetairos class,” but it’s unclear if they were also Hetairoi until their father was dead. E.g., so while Parmenion lived, were Philotas, Nikanor, and Hektor also Hetairoi? They seem to have been, at least Philotas and Nikanor, but it’s never made clear, nor at what age they would have been named in addition to their fathers, if they were.

From this Hetairoi class, the king drew the King’s Boys (Basilikoi Paides), usually referred to in English as the Royal Pages (or royal pages, although I prefer the cap). They’re closer to squires, in a medieval sense. Again, we aren’t sure how many there were, probably varied, but again, c.100 would make sense. It was at once an honor as well as a way to hold the boys hostage for their fathers’ loyalty. They seem to have served from 14-18 (give or take), after which they were reassigned to various military units as junior officers, or took a turn in the Royal Hunters (sacred to Herakles Kynagidas). We’re not sure what they did, perhaps rural police? The (duty) Pages fought beside the king in combat, and served him daily outside it, performing duties (such as emptying the chamber pot!) normally performed by slaves. Only the king had Pages. It was a sort of officer training school for the elite. (Other officers might have had slaves and junior staffers, but not Pages.)

Princes had their own circles of companions called Syntrophoi, all or the bulk of which were sons of Hetairoi, and might be selected by the king rather than by the prince in question. So in Becoming, Philippos assigns a number of boys to go with Alexandros to Mieza, but also lets Alexanros pick some of his own (Hephaistion and Ptolemaios among them).

Use of Hetairoi gets confusing where it intersects with the military. So the Companion Cavalry (Hippeis Hetairoi) are also called just Hetairoi in our sources. Once upon a time in Macedonian history, the two would have been the same. Only the Hetairoi and their sons could have afforded horses to serve as cavalry, riding with the king.

By Philip’s day (or perhaps earlier under Archelaos), military changes had opened up cavalry beyond nobility. Also under Philip, regular pikemen were called just pezes(Foot), but his special infantry who guarded the king in combat also got a special title: Pezhetairoi: Foot Companions. E.g, the infantry equivalent of the Companion Cavalry. We’re told Philip chose them for size and fighting ability, not necessarily noble birth, although Waldemar Heckel argues that especially the agema (e.g., Royal) unit was composed of young Hetairoi class on the fast track to command. Yet here we begin to see the rise of men on merit, not birth.

A Foot Companion wasn’t necessarily an Hetairos. And increasingly, not all Cavalry were either.

Alexander renamed the special unit Hypaspists (which just means “Shield Bearer”) and extended the honorary Foot Companions to the whole infantry—who certainly weren’t noblemen.

So when we write about Philip and Alexander, at least some Macedonian specialists refer to the army units by English translations, while using the Greek Hetairoi for the political title. I did the same in Dancing with the Lion. But this isn’t a universal usage.

As to the special seven-man unit called Bodyguards, or Somatophylakes (Somatophylax, sing.), like the Pages, it was more political-civic. The Somatophylakes guarded the king’s person, but inside, while the Pages were stationed outside (his tent or chambers). Kings would never have been alone unless demanding it for some particular reason. Yes, even in the bedchamber, even during sex; they weren’t nearly so prudish as we are. It also seems that one Somatophylax was the official taster for the king’s food and drink. (Ptolemy Lagus had that job at one point for Alexander.) During royal supper parties, they were the only armed people in the room. (When Alexander murdered Kleitos during a brawl, he grabbed the spear of a duty Somatophylax.)

So while they did have actual guard duty, it was very much honorary, and they did more than just guard, including act as gofer. As with the Pages, the fact it was for the king turned jobs “beneath their station” into an honor instead of an insult. (This is also why nobody but the king had them. Princes might have guards, but they weren’t Somatophylakes.) It’s not only possible but likely the king had additional guards besides the Seven who were closer to a Secret Service. The Somatophylakes often had other, quite prominent offices, which may have been tough to keep up if also standing guard on the king all night.

We think both the Somatophylakes and Basiliskoi Paides were inspired by Persian court practice. We’re not sure when they emerged. Under Alexander I, who, recall, was a Persian subject in the Persian Wars? His reign ended c. 450. Others date the institutions later, to Archelaos (d. 399), or even Philip II (d. 336). Archelaos introduced numerous advances anticipating Philip II, but his reign was only about 14 years, after which Macedon sank back into crazy successor wars until Philip.

In any case, the Somatophylakes should not be understood as an ancient Macedonian Secret Service. The minutia of how they functioned daily is unclear. I suspect part of our problem is that the unit evolved over time, and the bulk of our evidence comes from the reign of Alexander, who fundamentally changed the military.

One important point Heckel makes is that the unit was honorary, and like other high military offices, a new king couldn’t just sweep out the old to bring in the new. These are not men you demote, not if you want to stay king (and alive). Alexander replaced his father’s only as they died, and even then, he advanced his New Men into those slots slowly. He was just 20 upon taking the kingship, and far from secure in it.

Do not trust the Wikipedia list of names and dates for Alexander’s Bodyguard; only the last two years are correct, as the full Bodyguard was named only once, by Arrian (6.28.4), upon Peukestas’s extraordinary appointment as #8. (And yeah, I just edited it to warn as much.) Prior to that, we know them mostly via a mention here and there, so the completecompliment at any one time is guesswork. For Philip, it’s even worse. We have only a couple names, Balakros being one.

Somatophylakes weren’t necessarily the highest of the high, however. Neither Parmenion nor any of his sons were among them, nor was Krateros, Koinos, etc. That said, by the end of his life Alexander had appointed several of his inner circle to the unit, including Leonnatos, Lysimachos, Perdikkas, Ptolemy, and of course, Hephaistion. Hephaistion was never replaced after his death, so the number returned to seven. In fact, it’s possible that he left the Bodyguard when made Chiliarch, if that appointment did happen late, in, say, Babylon, as such an office would have required a hell of a lot of time—hard to do if you’re also guarding the king’s bed chamber. With Peukestas, Alexander would still have had seven Somatophylakes.

Another point of confusion concerns the distinction between the Seven, and the king’s guard in combat. The Pezhetairoi (for Philip) or Hypaspists (for Alexander) were the king’s personal guard on a battlefield. Somatophylakes did not serve together as a unit. They served (or more often commanded) their own units. So when Hephaistion is called “chief of the king’s bodyguard” at Gaugamela, that means he headed the agema unit of the Hypaspists. Similarly, when Pausanias (who assassinated Philip) is called the king’s “bodyguard,” more likely he was a member of the Pezhetairoi. A king—even one as wildly successful as Philip—couldn’t kick a man out of the Somatophylakes just to replace him with another. Notice that when Alexander wanted to honor a man that way, but had no open slot, he ADDED Peukestas. He didn’t demote anybody.

When Hephaistion joined them is difficult to say. He doesn’t seem to have been a Somatophylax at the time of the Philotas Affair (nor were Krateros or Koinos, the other two who tortured Philotas). See my comment above about Alexander moving slowly in replacing his father’s top men. After the fall of Philotas, and Parmenion, we see increasing upward movement for the “New Men.” Even so, Alexander appointed Kleitos along with Hephaistion to command the Companions, and not long after, following Kleitos’s death, reorganized them all into battalions. Hephaistion commanded one, but only one, albeit the most important (apparently the one with the agema, or royal unit).

That still leaves us in the dark as to when he became a Somatophylax. He was one by Carmania, post-Gedrosia. That’s the best we can say with certainty. Same problem with his Chiliarchy. He was Chiliarch by the last year of his life, but how long before? Alexander engaged in a never-ending revision of army and court, and only sometimes are we told precisely when the changes occurred.

I don’t put Hephaistion’s elevation to Somatophylax early. Waldemar’s right. Alexander couldn’t hand out plum positions to younger men too soon. After all, he still had a Somatophylax in Baktria who led a plot to assassinate him! Demetrios was almost certainly a holdover from Philip’s day. It’s possible Hephaistion got the slot then, but maybe not. He received half the Companions, so making him Somatophylax as well could’ve been perceived as too much.

Back to what our sources don’ttell us. Appointment to the Bodyguard assumed the death, or retirement, of a former Bodyguard. It’s more like a reward and acknowledgement of very high standing at the court than a “promotion.” That’s why Peukestas got the exceptional eighth position: he’d saved Alexander at Malia.

July 9, 2020

New Interview

You can find the interview here.

Read and enjoy!

June 11, 2020

Pride Month Extra!

That's now up on my Cut/Extra Scenes page on the website.

https://jeannereames.net/Dancing_with...

(That it contains huge spoilers goes without sayin'...)

May 8, 2020

How to Compliment a Professor and Not Sound Like a Suck-up

First things first, all professors were once students. We ARE professors because one or more then-professors inspired us and caused us to love higher education enough to want to do it full time. In short, all current professors had a professor or three s/he/they genuinely idolized.

The problem, speaking from the other side of the desk, is that we also get students who attempt to suck-up in order to get an A (or sometimes just a passing grade). When I was an undergrad, I resisted talking to professors for that reason. I’d loved chatting with teachers in junior high and high school, and got called a “teacher’s pet” by those jealous. So I went the other way in college. I stayed aloof. That’s not the solution, either. It took grad school to reconnect me with professors as human beings.

Remember, professors are human, and we’re in this business NOT for the money (trust me!). We love to teach. We love to share knowledge. We love to see other people excited by what excites us. Frankly, I hate grading. Giving feedback is one thing. I want my students to improve. But I’m required to grade. If I could just give feedback to students who honestly wanted to receive it (and actually READ it and took it to heart), and I never had to grade at all? DAMN! That’s my ideal world. I’d work so much harder with each student. But students do papers I grade with extensive markups that I know damn well half (or more) never look at (comments that sometimes literally take hours), so why am I wasting my time? They just want the grade. Not to LEARN. It’s so disheartening.

So there you go. If you want to compliment a professor you really LIKE, who inspires you…tell us what you’re LEARNING. Talk to us about the class you’re in. Ask questions beyond the lectures. Swing by during office hours, just to chat. NO, you’re (probably) not bothering us. Why do you think we’re here? Also, we’re open to hearing what’s not working for you, especially if it’s a new/first time class. Professors experience a class differently from students. I can’t know how students experience it unless they tell me. The best classes are not built by professors alone, but by professors in dialogue with former students.

We want to TALK to you about what we teach. Really.

Telling me I’m “such an awesome lecturer” and “I really love your class” just makes me suspicious about what you want from me. I mean, that’s nice, and maybe you’re genuine, but I hear that shit from a lot of students who just want an “A,” and they think flattering me will get it.

I’m not a narcissist. As soon as you tell me I’m “a great teacher” with no qualification (unless it’s AFTER I’ve turned in final grades), the more I wonder what you want. I’m sorry that’s true, but it’s like excuses for missing class. Students have so many “dead granny” issues during the semester that for the student who really DOES lose a grandmother they loved dearly (my brother went AWOL from the Navy when Granny Brouillette died because he was so close to her), we’re disinclined to believe you. And I hate that. Because if you really DID lose your beloved granny, I’d prefer to sympathize with you. (So, word to the wise, if you’ve an ill family member, please tell your professors immediately in the semester, so if you do lose that person, we’re aware it might happen and it’s comes far less like an “excuse.”)

The upshot is this. The more specific you are about what you like in a class, and the more you ask questions or chat after class/outside of class, the more we’re likely to believe compliments. The more we can See You Real. I prefer that with students. I want to know you. Even if history isn’t your major (it’s not required to be interested in history!), if you still enjoy the topic, let’s chat.

But if you really are just sucking up to the prof to improve a grade you know is borderline? We’ve probably got your number and it works against you. Crap students who try to play Happy, Shiny People at semester end (especially if hoping to graduate) when they’ve been mediocre (at best) all semester? Yeah…not buying it. That actually hurts you as you’re pissing me off by trying to play me.

Last, however much you may like your professor, please maintain polite, professional distance. Don’t loom over us, attempt to touch us/hug us, etc., without exceptional circumstance. This is quite aside from the obvious, don’t offer to have sex with us! Don’t invite us out to have a beer, or bring us presents (worth more than a dollar or two) until aftergrades are given out. You may mean it innocently, but they present a professor with an ethical dilemma: insult you by refusing a present, or take the present and risk accusations of impropriety. I once had a student leave class for a personal emergency who wrote the reason for it on a dollar bill…all he had. I still have that dollar bill in my desk (rather than using or depositing it) to avoid any accusation—years later—of bribery. Now, it’s for humor, but not in the years immediately after. It MATTERS.

More no-nos…don’t try to friend your professor on Facebook (unless a grad student). Never ask for a professor’s phone number, home address, or (non-uni) email, unless there’s a really damn good reason (perhaps a professional conference or similar). Sometimes professors will invite an upper-division class to their home for an end-of-semester party, which is fine with all students there. (I do this for my ATG class.) Don’t try to stay late, or arrive early. Even if it’s innocent, it puts the professor in a bind. Don’t call your professor by his/her/their first name unless invited. (And frankly, they shouldn’t invite it. They’re Prof. ___ or Dr. ___.)

So yes, we’d love to get to know you outside of class! But do maintain those professional boundaries. And if a professor is NOT doing that, and not taking your signals to keep a polite distance…talk to someone else in the department. Don’t become a victim of a predator! If you think it’s creepy…it’s probably creepy. And if I find you creepy (I’ve got one this semester; no sense of personal space), I’ll keep you at a distance and probably be hostile to you. I’m not sure what you want, but suspect it’s not good.

December 29, 2019

How Do I Intend to Depict Alexander Going Forward in DANCING WITH THE LION?

Put all that together, inject it with a hefty dose of testosterone, and you begin to understand Alexander (and larger Macedonian society).

Modern attempts to paint Alexander (ATG) as a hero or a villain often depend on modern views of virtue, not ancient ones. We want our heroes to be Captain America, or Frodo Baggins. Good-hearted, honest, humble, sometimes reluctant heroes. They’re driven by a sense of SERVICE, not a desire for KLEOS.

THAT IS EMPHATICALLY AT ODDS WITH ALEXANDER’S PRECHRISTIAN WORLD.Which makes him a hard sell.

I don’t plan to paint ATG as either hero or villain, in the usual sense. The very last line of Dancing with the Lion: Rise is highly ironic. I won’t repeat it here for those who may not yet have read the second book, but while Alexander absolutely means what he thinks in that moment, it’s a young man’s fancy.

It ain’t gonna be so easy.

Riptide has said they likely won’t publish further in the series, even before the first two came out, because the whole thing is a tragedy, not a romance. The first two books (or really one novel) have a “happily for now” ending, so they were okay with that. But we all know how the story ends.

It’s not a tragedy, however, because Alexander is a megalomaniacal villain. The protagonists of tragedies are called the “ tragic hero ,” after all.

I want to continue writing him much as I tried to in Becoming and Rise: a human being with flaws and virtues. And as with any tragic hero, the greatest flaws are often overdrawn virtues. Virtue turned inside out.

So again, if you’ve read book two, go back to the novel’s last line. There’s his tragic flaw in all it’s glory. His desire to uphold that, often in the face of serious reality checks, will finally break him in Baktria, where in the name of virtue, honor, and piety, he’ll commit a terrible atrocity that will drive Hephaistion from him for some time. Hephaistion is still loyal to him as king, mind, but he can’t stomach what happens on a personal level. It’s no silly love triangle, situational misunderstanding, or manufactured angst for “drama.” It’s a deep, fundamental ideological clash–the sort of thing that Real Couples face sometimes, and must then choose to accept and move beyond, or acknowledge is irreparable and separate.

Obviously, they’ll get over it. But it’s not immediate. Nor easily. And it will involve a lot emotional blood on the floor, from both of them.

Baktria is the pivot point in the series, where it moves from triumph to tragedy. Things that came together are now falling apart.

Less poetically, Alexander is discovering–post Gaugamela–that “compromise” is the ugly truth of successful politics. I love the line from Hamilton, George Washington to another brilliant, impetuous young man named Alexander: “Dying is easy, living is harder.” Alexandros may want to be Achilles, but Achilles DIED.

In Alexander’s case, “Conquest is easy, ruling is harder.”

Alexander has no plans to die, but he’s going to realize how much of what he thought would be the case about rule…isn’t. And maybe his father DID know a thing or three, after all.

Alexander has no plans to die, but he’s going to realize how much of what he thought would be the case about rule…isn’t. And maybe his father DID know a thing or three, after all.Historically, at the end of his life, Alexander is much less idealistic: shrewder, harder, less trusting, and more pragmatic. Just look at his appointments at the beginning and in his last two years. Early on, he’s inclined to put the former ruler back in charge, as long as that ruler surrendered to him, and add a garrison. After returning from India, he discovers how many of those men (and some garrison commanders too) betrayed his trust. So he kills the lot and reappoints…virtually all Macedonians (and a few Greeks).

This is the opposite of Tarn’s “Brotherhood of Mankind” (which was enshrined in Renault’s The Persian Boy, and picked up as well by Stone’s 2004 flick).

This is Macedonian Realpolitik.

It’s also Alexander Disillusioned.

But he’s still not the devil. That’s too simplistic, and too modern. While I greatly admire Brian Bosworth’s scholarship (he was THE Arrian specialist), I disagree with his assessment of Alexander’s career in his 1986 JHS article, “Alexander the Great and the Decline of Macedon,” wherein he ends with, “That was the unity of Alexander–the whole of mankind, Greeks and Macedonians, Medes and Persians, Bactrians and Indians, linked together in a never ending dance of death” (12).

What Bosworth ignores is that nobody at the time would have seen conquest in itself as evil, merely how one went about it. And how Alexander went about it is, actually, a mixed bag. Maybe that’s his problem. He’s not ruthless enough to be admired for his sheer bloody-mindedness (aka, Genghis Kahn), but he did some terrible things, which kinda undercuts the “squeaky good guy” image he wanted to project–and I think genuinely wanted to believe himself to be.

We live in a post-WWI and post-WWII world, where starting a war to take land is sorta frowned upon. Even if Putin, Xi, and Erdoğan Didn’t Get That Memo. But that colors how we read Alexander’s career. We can’t and shouldn’t ignore Alexander’s atrocities, but casting him as a Hitler-esque madman says more about us than him. Alexander was NOT Hitler.

One of the toughest things about doing ancient history is this weird “double think” wherein the historian must UNDERSTAND why ancient people do what they do or think what they think…without necessarily approving of it. THIS IS HARD. It’s really hard. Too often, both professional historians and fans of history either react with modern attitudes and refuse to understand (because they find something so appalling), OR they go so far into the “understand” that they confuse it with “approve.”

One of the toughest things about doing ancient history is this weird “double think” wherein the historian must UNDERSTAND why ancient people do what they do or think what they think…without necessarily approving of it. THIS IS HARD. It’s really hard. Too often, both professional historians and fans of history either react with modern attitudes and refuse to understand (because they find something so appalling), OR they go so far into the “understand” that they confuse it with “approve.”Walking that line is what I hope to do, going forward with Dancing with the Lion. There are ways to faithfully show ancient attitudes even while telegraphing to the reader that’s not okay. (Hephaistion often gets used for that, incidentally, both in what’s been published and in what’s coming.)

Back to Alexander…I think he was often frustrated with Macedonian pushback, given his need for approval/affection. (That’s one of the key elements of ATG’s character that I think Mary Renault hit dead on the head in her novels.) I also think he was deeply disappointed in his Macedonian soldiers at times. As noted above, Tarn’s whole “Brotherhood” notion cracks apart when we look at what Alexander actually DID, not what he said in his “Reconciliation Banquet” speech. (Remember, ancient speeches are NOT what anybody actually said, but [maybe] the gist couched as a rhetorical exercise by the authors of these texts … regardless of whether it’s Thucydides’s “Funeral Oration” of Perikles, Arrian’s speech by Alexander after the Opis Mutiny, or Calgacus’s address to his troops found in Tacitus.)

Remember what I said about expectations for Macedonian kings? Win wars and provide loot. Alexander did that with bells on. As I’ve said before, here and elsewhere, he was the Energizer Bunny of Macedonian kings, just kept going and going and going….

Yet somewhere along the way, he decided he wanted to rule what he’d won, not simply plunder it. Opinions about Alexander’s “Persianizing” have waxed and waned. First, it was so tied into the “Brotherhood” concept that after Badian, et al., torpedoed Tarn, ATG was recast as simply a glorified marauder. Yet more recently, the pendulum has begun to swing back, pointing out that, rather than some ideological notion, perhaps it was pragmatic?

Alexander was a very smart man. He understood that to rule this new united kingdom he’d created, he had to get creative. I think he also, quite genuinely, LIKED some of Persian culture. IMO, there are two basic types of people. Those who see something different, regard it with fear and suspicion, and run away or denigrate it. Then there are those who see something different and regard it with curiosity and run towards it. Alexander was (I think clearly) the latter type.

Alexander was a very smart man. He understood that to rule this new united kingdom he’d created, he had to get creative. I think he also, quite genuinely, LIKED some of Persian culture. IMO, there are two basic types of people. Those who see something different, regard it with fear and suspicion, and run away or denigrate it. Then there are those who see something different and regard it with curiosity and run towards it. Alexander was (I think clearly) the latter type.Yet many of his soldiers were not. They belonged to the former type. Plus, they’d been conditioned to think of themselves as conquerors, masters, etc. They’d proven their superiority on the battlefield. It’s the most simple sort of ethnocentrism: the “schoolyard bully” type. We beat you, so we’re better than you. They didn’t hold with Alexander’s myth-infused notions of conquest. To be honest, I don’t think Alexander held with them after Baktria. But I do think he understood that if he wanted to become Shah-han-shah of Persia, he couldn’t squash the Persians (and everyone else) under his heel.

IMO, too many modern historians are inclined to elevate the objections of Alexander’s soldiers, as if they are somehow pure of motive while Alexander isn’t, and he’s betraying them. That’s buying into ancient narrative bias. Let’s recast the whole thing in the modern era.

I see certain parallels between Alexander’s Macedonian soldiers and the red-hat wearing mobs at Trump rallies, terrified of the “browning of America” and convinced of their own cultural (and racial) superiority. The more diverse Alexander’s army became, the angrier his Macedonian troops got. One of the breaking points behind the Opis Mutiny was the emergence of the “Epigoni,” The mixed-race and Iranian boys trained in Macedonian arms. That INFURIATED the rank-and-file Macedonians. How dare Alexander share the sacred trust of Macedonian military might with Those People (who we just conquered and so, must be inferior to us)?

I see certain parallels between Alexander’s Macedonian soldiers and the red-hat wearing mobs at Trump rallies, terrified of the “browning of America” and convinced of their own cultural (and racial) superiority. The more diverse Alexander’s army became, the angrier his Macedonian troops got. One of the breaking points behind the Opis Mutiny was the emergence of the “Epigoni,” The mixed-race and Iranian boys trained in Macedonian arms. That INFURIATED the rank-and-file Macedonians. How dare Alexander share the sacred trust of Macedonian military might with Those People (who we just conquered and so, must be inferior to us)?Reframed so, I think it easier to get beyond ancient pro-Hellenic source bias.

This is definitely something I’ll be playing with in the novel. It will NOT be “the poor, benighted troops are being mistreated by Ruthless Alexander.” But it also won’t be, “Alexander can do no wrong, and his men have no legitimate beefs.”

Life is NEVER that clear-cut.

NUANCE is all. And in the end, Alexander’s own virtues: his creativity, his ability to think outside the box, his insatiable desire to succeed, and his need to at least appear to be honorable…all these things will be his undoing.

(PSA: I reserve an author’s right to change my mind as I go forward and see how the series unfolds, but at least at present, this reflects my intentions, and some details aside, I think the gist will stay true.)

December 11, 2019

Alexander and Hephaistion Going Forward (future books)

I saved this blog (and Tumblr question) till the end, as it's about the future. I DO hope to continue Dancing with the Lion into Alexander's Asian campaign, but much depends on how well the first two books perform.

Publishers are pragmatic. They buy what they think will sell, so they look at an author's prior sales record, as well as "noise" about their books: e.g., blog posts, Twitter activity, hashtags, and reviews of prior books on Goodreads/Amazon/etc (which can help drive sales). If they don't think prior novels sold well enough, they're not interested. End of the road.

Word of mouth is the best advertising of all. So if you want more, please talk about it. Tell your friends, both in person and online. To that end, looking FORWARD....

Anonymous Question from Tumblr: "I know you've said you'd like to continue Alexander and Hephaistion's story beyond 'Rise,' so can I ask how you see their relationship changing over the years as Alexander becomes 'the Great'?"

The biggest hurdle the two will face are Greek and Macedonian assumptions about proper relationships. If ancient Greece is sometimes portrayed as Gaytopia, it wasn’t. In the novels, I’ve endeavored to depict ancient sexual mores honestly, even if that may “harsh some squees.”

Same-sex partnerships were accepted, but rules still governed WHAT was permitted. It all came down to maintaining the social standing (timē) of the citizen men involved. Anything that made one of them too much “like a woman” was anathema, because theirs was a highly misogynistic society.

[image error] Ergo, past a certain age, men were expected to graduate, if you will, from the younger (passive) partner to become the elder (active) partner. Once able to grow a solid beard, a man who continued in the passive (womanish) role was looked down upon. Whoever held the higher status was assumed to be the “active” partner, and--in the Greek south--ageusually determined who held that status. That's how they framed it, which complicates things for Alexandros and Hephaistion in the first two novels because Alexandros holds the higher social status despite being the younger partner.

All of which leads us to the much BIGGER issue.

What a society presents as an ideal is not necessarily what they're actually doing. Eminent medievalist Peter Brown in his excellent The Body and Society (1988, xvii) described the difficulty for modern historians as, "it is both our privilege and our accursed lot to work the flinty soil of a long-extinct and deeply reticent world." If he was mostly talking about Late Antiquity, it applies to the Greeks of the Classical age, as well.

Anybody who kicks against the goads of the ideal faces problems. THIS is what I hope to explore for Alexandros and Hephaistion, going forward. Until Alexandros is 18/19-ish, their relationship is acceptable, if eyebrow raising due to the status-vs-age issue. Otherwise, it’s a pretty normal pairing until the end of Rise.

When Alexandros becomes king at 20, he’s both too old to be “the boy,” and AS king, absolutely cannot be the boy. Yet Hephaistion is even older, and shouldn’t be “the boy” either, or not without losing social face (the timē I mentioned above). Even as prince, Alexandros had been expected to demonstrate that he could perform sexually with a woman in order to father an heir. In Rise, he takes a mistress, who he does care about, but the primary purpose of the liaison is to prove he's not impotent. After he becomes king, what he and Hephaistion had continued semi-openly must become semi-closeted.

Why?

If Alexandros is perceived to be the passive partner, it undermines his authority. Yet if it’s implied or made clear he is notthe passive partner—Hephaistion is—that not only undermines Hephaistion’s authority going forward, it humiliates him socially. Were Alexandros still prince, they might have continued a little while in a shadowy “Well, they’re not that old yet…”

Alexandros becoming king changes the landscape profoundly.

Kings, especially young kings not yet secure on their thrones, cannot do just whatever the hell they want, as the court of public opinion is merciless. Macedonian kings ruled by the consent and support of the people, especially the army. That meant they had to win wars, deliver loot, and maintain the respect of their people, particularly soldiers. And if Philippos had multiple male lovers, they were all younger and met the usual assumption of status-superior elder (Philippos) to status-inferior junior (Philippos's flavor-of-the-month). In short, Philippos never transgressed social assumptions for same-sex relationships.

In order to stay a couple, Alexandros and Hephaistion must enter the ancient Macedonian closet. And if their inner circle might know they're still sexually involved, it can’t be publicly acknowledged. Their friendship was legendary, and as philiawas regarded as the higher love anyway, it’s not dishonest to emphasize that philia…even if those close to them in the novel realize there's more to it. And as Alexandros's successes compound, the more he's freed of the constraints regarding what his society "allows."

While I realize this can be frustrating to those who'd just like a simple "happily ever after" and a society where same-sex relationships weren't just permitted, but enshrined as a philosophical ideal--I endeavor to tell the truth. And the truth is complex.

To my mind, it's more interesting to examine how a society that did permit same-sex relationships also restricted them. That might shine a light on how we think about them now. Such restrictions are always social constructs. And if being a social construct doesn't make them "unreal" any more than the social construct of a brick wall is unreal (you'll still get a bruise if you slam your shoulder into it), the fact they ARE constructs means that we can "unconstruct" them.

Imagine a life without such walls?

(Image by Neoclassicist painter, Louise Gauffier, 1791. It represents a story from Plutarch wherein Alexander “sealed” Hephaistion’s lips [with his ring] when H. was “caught” reading private mail over the king’s shoulder. An “oops” moment about their intimacy that Alexander handled graciously. But we might imagine that their lips are sealed about what else they do behind closed doors.)

November 25, 2019

Philippos, Amyntor, and Fathering in Dancing with the Lion

As a coming-of-age tale, dynamics between fathers and sons play a crucial role in both novels, making Philippos and Amyntor deliberate foils. Some of this is laid out in Becoming , but in Rise , it occupies front-and-center.

Philippos’s own father died when he was relatively young, 12-13 at most. In addition, he spent at least one, and possibly two, hostage-ships outside Macedonia. He had nothing approaching a normal childhood, even allowing for having grown up royal at a polygamous court. His father had two wives and at least seven children: six sons and a daughter, maybe more, as daughters weren’t necessarily recorded. His time as a hostage at the house of Pammenes in Thebes might have been the closest to normal he ever experienced, although later gossip implied that it wasn’t a fatherly relationship the young Theban general had with young teen Philippos.

Philippos’s own father died when he was relatively young, 12-13 at most. In addition, he spent at least one, and possibly two, hostage-ships outside Macedonia. He had nothing approaching a normal childhood, even allowing for having grown up royal at a polygamous court. His father had two wives and at least seven children: six sons and a daughter, maybe more, as daughters weren’t necessarily recorded. His time as a hostage at the house of Pammenes in Thebes might have been the closest to normal he ever experienced, although later gossip implied that it wasn’t a fatherly relationship the young Theban general had with young teen Philippos.Despite all that (or because of it), the thought he put into Alexandros’s education suggests deep concern not only to raise a son, but an heir who could survive the bloodbath of Macedonian inheritance. Even before Aristoteles arrives, Alexandros’s schooling was based on a southern Greek model. Later, after he returned from study, Philippos gave him increasingly important duties, yet always under guidance. This is the period covered by Rise . So if our instinct is to critique Philippos for being harsh, we must measure it against his own childhood, and his desire that his son survive. He wants to be a good father; he just doesn’t know what that looks like.

As a teen, Alexandros is often overconfident, thinking himself ready for appointments he’s not ready for. Philippos knows better, and does a masterful job of selecting tasks he can manage. Quite contrary to portrayals of Philippos as jealous and trying to hold back Alexandros, when looked at from outside the lens of later propaganda, Philippos fairly consistently sought to teach his heir the essentials of ruling. They had some spectacular blow-ups, but the evidence says they got along as often as not.

Yet there IS a darker side to Philippos: his tendency to violence when frustrated. Unfortunately, Alexandros frustrates him on a number of occasions (as does Myrtalē). I do want to note that this construction is fictional. Evidence that the real Philip of Macedon engaged in regular domestic violence is circumstantial and scarce, outside the “wedding incident.” But I took that event and built on it, given cultural assumptions of the time.

The ancient world permitted, even expected harsh discipline. If they didn’t have mass shootings or serial killers, compared to today, their world was “casually brutal.” Beating a slave for bad behavior or just a perception of laziness was not only allowed, but encouraged. Paddling children or using switches or canes was normal. Slapping a wife or mistress didn’t raise much comment. By no means did every adult male do such things, and there’s indication that beating one’s wife or children was stigmatized, but mostly as evidence of a lack of self-control. Not because the aggression itself was considered wrong.

In one key scene at the beginning of Rise, Alexandros starts to ape his father’s usual response when frustrated by his mother: he raises his arm to strike her. Yet he stops himself. He chooses not to become his father. It isn’t, however, a magic fix. We know that men who engage in assault came, themselves, from violent homes. Children learn what they live . Going forward, Alexandros will face the same choice on other occasions in his life, and sometimes, he’ll fail the test.

So the uncomfortable conflict at the heart of both novels is that Philippos does love his son, does want him to succeed, but finds him frustrating and difficult, and reacts with a brutality he always later regrets.

Yet while he may be the novel’s antagonist, he’s not the “bad guy.”

Making an abuser the bad guy is tempting. How could someone love his son, yet leave him with bruises (or worse)? To claim such a thing might seem to be making excuses. That’s where the tightrope walking begins. Philippos does bad things, which are acknowledged as bad things, yet he repents and tries to make up for them, usually awkwardly. He’s a bad father because he doesn’t know how to be a good father, and that’s his tragedy. He was a magnificent strategist, a wiley negotiator, and a visionary king…but a crappy dad.

Enter Amyntor.

First, Amyntor has a good ten years on Philippos, and four children older than Hephaistion. In short, he has more practice. Furthermore, he and Hephaistion are much alike, personality-wise, something underscored several times in both novels. Amyntor understands his youngest. So he’s presented as the “good father.”

But he’s not a perfect father. Those don’t exist. I’d remind readers of what set in motion events at the start of Becoming(book I): Hephaistion ran away from home.

He did so because he was a teen boy, stubborn and headstrong. Yet Amyntor made mistakes, too, which led to Hephaistion’s bad choices. Both are human. They’re doing the best they can, given their own limited perception of things . And I drew them so, because even well-intentioned, mature people can still screw up. The difference is in how they react. Amyntor doesn’t try to force Hephaistion to come home, quite aside from whether he legally could have. He doesn’t do so because he recognizes his son’s autonomy and respects it, even if he doesn’t agree with it. His reaction is sorrow and worry, not uncontrollable anger.

That’s where he steps away from Philippos. He’s the “good father” because he’s emotionally mature. Anger is a fear reaction, and Philippos learned young to be terrified. When threatened: attack. Amyntor responds to the world in a wholly different way, and teaches his own children the same, plus a few strays: Ptolemaios and Alexandros.

The irony, of course, is that his political acumen isn’t terribly high. If not as clueless as his son thinks, he’s an isolationist by policy, unconcerned (and thus, ignorant) of wider Greek affairs of state and their ramifications. So Hephaistion comes to Pella to learn politics from Philippos. But in the end, it’s Alexandros who learns the greater lesson from Amyntor, who models what fatherhood should look like.

For victims to escape the cycle of violence, they have to know there are other options. Amyntor (and Hephaistion) represent those alternatives for Alexandros.