Luke Wroblewski's Blog, page 2

September 25, 2025

Future Product Days: How to solve the right problem with AI

In his How to solve the right problem with AI presentation at Future Product Days, Dave Crawford shared insights on how to effectively integrate AI into established products without falling into common traps. Here are my notes from his talk:

Many teams have been given the directive to "go add some AI" to their products. With AI as a technology, it's very easy to fall into the trap of having an AI hammer where every problem looks like an AI nail.

We need to focus on using AI where it's going to give the most value to users. It's not what we can do with AI, it's what makes sense to do with AI.

AI Interaction Patterns

People typically encounter AI through four main interaction types

Discovery AI: Helps people find, connect, and learn information, often taking the place of search

Analytical AI: Analyzes data to provide insights, such as detecting cancer from medical scans

Generative AI: Creates content like images, text, video, and more

Functional AI: Actually gets stuff done by performing actions directly or interacting with other services

AI interaction patterns exist on a context spectrum from high user burden to low user burden

Open Text-Box Chat: Users must provide all context (ChatGPT, Copilot) - high overhead for users

Sidecar Experience: Has some context about what's happening in the rest of the app, but still requires context switching

Embedded: Highly contextual AI that appears directly in the flow of user's work

Background: Agents that perform tasks autonomously without direct user interaction

Principles for AI Product Development

Think Simply: Make something that makes sense and provides clear value. Users need to know what to expect from your AI experience

Think Contextually: Can you make the experience more relevant for people using available context? Customize experiences within the user's workflow

Think Big: AI can do a lot, so start big and work backwards.

Mine, Reason, Infer: Make use of the information people give you.

Think Proactively: What kinds of things can you do for people before they ask?

Think Responsibly: Consider environmental and cost impacts of using AI.

We should focus on delivering value first over delightful experiences

Problems for AI to Solve

Boring tasks that users find tedious

Complex activities users currently offload to other services

Long-winded processes that take too much time

Frustrating experiences that cause user pain

Repetitive tasks that could be automated

Don't solve problems that are already well-solved with simpler solutions

Not all AI needs to be a chat interface. Sometimes traditional UI is better than AI

Users' tolerance and forgiveness of AI is really low. It takes around 8 months for a user to want to try an AI product again after a bad experience

We're now trying to find the right problems to solve rather than finding the right solutions to problems. Build things that solve real problems, not just showcase AI capabilities

Future Product Days: Hidden Forces Driving User Behavior

In her talk Reveal the Hidden Forces Driving User Behavior at Future Product Days, Sarah Thompson shared insights on how to leverage behavioral science to create more effective user experiences. Here's my notes from her talk:

While AI technology evolves exponentially, the human brain has not had a meaningful update in approximately 40,000 years so we're still designing for the "caveman brain"

This unchanging human element provides a stable foundation for design that doesn't change with every wave of technology

Behavioral science matters more than ever because we now have tools that allow us to scale faster than ever

All decisions are emotional because there is an system one (emotional) part of the brain that makes decisions first. This part of the brain lights up 10 seconds before a person is even aware they made a decision

System 1 thinking is fast, automatic, and helped us survive through gut reactions. It still runs the show today but uses shortcuts and over 180 known cognitive biases to navigate complexity

Every time someone makes a decision, the emotional brain instantly predicts whether there are more costs or gains to taking action. More costs? Don't do it. More gains? Move forward

The emotional brain only cares about six intuitive categories of costs and gains: internal (mental, emotional, physical) and external (social, material, temporal)

Mental: "Thinking is hard" We evolved to conserve mental effort - people drop off with too many choices, stick with defaults. Can the user understand what they need to do immediately?

Social: "We are wired to belong" We evolved to treat social costs as life or death situations. Does this make users feel safe, seen, or part of a group? Or does it raise embarrassment or exclusion?

Emotional: "Automatic triggers" Imagery and visuals are the fastest way to set emotional tone. What automatic trigger (positive or negative) might this design bring up for someone?

Physical: "We're wired to conserve physical effort" Physical gains include tap-to-pay, facial recognition, wearable data collection. Can I remove real or perceived physical effort?

Material: "Our brains evolved in scarcity" Scarcity tactics like "Bob booked this three minutes ago" drive immediate action. Are we asking people to give something up or are we giving them something in return?

Temporal: "We crave immediate rewards" Any time people have to wait, we see drop off. Can we give immediate reward or make people feel like they're saving time?

You can't escape the caveman brain, but you can design for it.

Future Product Days: The AI Adoption Gap

In her The AI Adoption Gap: Why Great Features Go Unused talk at Future Product Days in Copenhagen, Kate Moran shared insights on why users don't utilize AI features in digital products. Here's my notes from her talk:

The best way to understand the people we're creating digital products for is to talk to them and watch them use our products.

Most people are not looking for AI features nor are they expecting them. People are task-focused, they're just trying to get something done and move on.

Top three reasons people don't use AI features: they have no reason to use it, they don't see it, they don't know how to use it.

There are other issues like in enterprise use cases, trust. But these are the main ones.

People don't care about the technology, they care about the outcome. AI-powered is not a value-add. Solving someone's problem is a value-add.

Amazon introduced a shopping assistant that when tested, people really liked because the assistant has a lot of context: what you bought before, what you are looking at now, and more

However, people could not find this feature and did not know how to use it. The button is labeled "Rufus" people don't associate this with something that helps them get answers about their shopping.

Findability is how well you can locate something you are looking for. Discoverability is finding something you weren't looking for.

In interfaces that people use a lot (are familiar with), they often miss new features especially when they are introduced with a single action among many others

Designers are making basic mistakes that don't have anything to do with AI (naming, icons, presentation)

People say conversational interfaces are the easiest to use but it's not true. Open text fields feel like search, so people treat them like smarter search instead of using the full capability of AI systems

People have gotten used to using succinct keywords in text fields instead of providing lots of context to AI models that produce better outcomes

Smaller-scope AI features like automatic summaries that require no user interaction perform well because they integrate seamlessly into existing workflows

These adoption challenges are not exclusive to AI but apply to any new feature, As a result, all your existing design skills remain highly valuable for AI features.

Future Product Days: Future of Product Creators

In his talk The Future of Product Creators at Future Product Days in Copenhagen, Tobias Ahlin argued that divergent opinions and debate, not just raw capability, are the missing factors for achieving useful outcomes from AI systems. Here are my notes from his presentation:

Many people are exposing a future vision where parallel agents creating products and features on demand.

2025 marked the year when agentic workflows became part of daily product development. AI agents quantifiably outperform humans on standardized tests: reading, writing, math, coding, and even specialized fields.

Yet we face the 100 interns problem: managing agents that are individually smarter but "have no idea where they're going"

Limitations of Current Systems

Fundamental reasoning gaps: AI models have fundamental reasoning gaps. For example, AI can calculate rock-paper-scissors odds while failing to understand it has a built-in disadvantage by going second.

Fatal mistakes in real-world applications: suggesting toxic glue for pizza, recommending eating rocks for minerals.

Performance plateau problem: Unlike humans who improve with sustained effort, AI agents plateau after initial success and cannot meaningfully progress even with more time

Real-world vs. benchmark performance: Research from Monitor shows 63% of AI-generated code fails tests, with 0% working without human intervention

Social Nature of Reasoning

True reasoning is fundamentally a social function, "optimized for debate and communication, not thinking in isolation"

Court systems exemplify this: adversarial arguments sharpen and improve each other through conflict

Individual biases can complement each other when structured through critical scrutiny systems

Teams naturally create conflicting interests: designers want to do more, developers prefer efficiency, PMs balance scope.This tension drives better outcomes

AI significantly outperforms humans in creativity tests. In a Cornell study, GPT-4 performed better than 90.6% of humans in idea generation, with AI ideas being seven times more likely to rank in the top 10%

So the cost of generating ideas is moving towards zero but human capability remains capped by our ability to evaluate and synthesize those ideas

Future of AI Agents

Current agents primarily help with production but future productivity requires and equal amount of effort in evaluation and synthesis.

Institutionalized disconfirmation: creating systems where disagreement drives clarity, similar to scientific peer review

Agents designed to disagree in loops: one agent produces code, another evaluates it, creating feedback systems that can overcome performance plateaus

True reasoning will come from agents that are designed to disagree in loops rather than simple chain-of-thought approaches

September 15, 2025

Defining Chat Apps

With each new technology platform shift, what defines a software application changes dramatically. While we're still in the midst of the AI shift, there's emergent properties that seem to be shaping what at least a subset of AI applications, let's call them chat apps, might look like going forward.

At a high level, applications are defined by the systems they're discovered and operated in. This frames what capabilities they can utilize, their primary inputs, outputs, and more. That sounds abstract so let's make it concrete. Applications during the PC era were compiled binaries sold as shrink-wrapped software that used local compute and storage, monitors as output, and the mouse and keyboard as input.

These capabilities defined not only their interfaces (GUI) but their abilities as well.

The same is true for applications born of the AI era. How they're discovered and where they operate will also define them. And that's particularly true of "chat apps".

So what's a chat app? Most importantly a chat app's compute engine is an AI model which means all the capabilities of the model also become capabilities of the app. If the model can translate from one language to another, the app can. If a model can generate PDF files, the app can. It's worth noting that "model" could be a combination of AI models (with routing), prompts and tools. But to an end user, it would appear as a singular entity like ChatGPT or Claude.

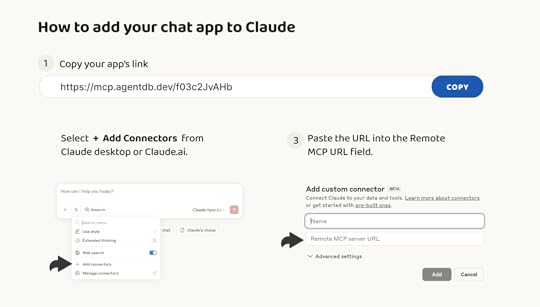

When an application runs in Claude or ChatGPT, it's like running in an OS (windows during the PC era, iOS during the mobile era). So how do you run a chat app in an AI model like Claude and what happens when you do? Today an application can be added to Claude as a "connector" probably running as a remote Model Context Protocol (MCP) server. The process involves some clicking through forms and dialog boxes but once setup, Claude has the ability to use the application on behalf of the person that added it.

As mentioned above, the capabilities of Claude are now the capabilities of the app. Claude can accept natural language as input, so can the app. When people upload an image to Claude, it understands its content, so does the app. Claude can search and browse the Web, so can the app. The same is true for output. If Claude can turn information into a PDF, so can the app. If Claude can add information to Salesforce, so can the app. You get the idea.

So what's left for the application to do? If the AI model provides input, output, and processing capabilities, what does a chat app do? In it's simplest form a chat app can be a database that stores the information the app uses for input, output, and processing and a set of dynamic instructions for the AI model how to use it.

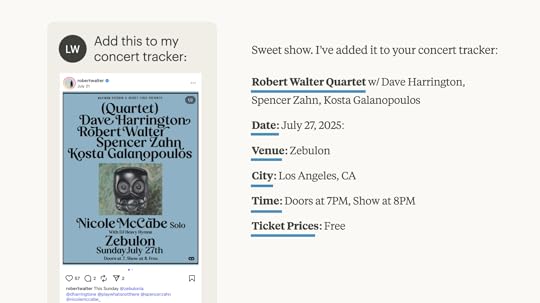

As always, a tangible example makes this clear. Let's say I want to make a chat app for tracking the concerts I'm attending. Using a service like AgentDB, I can start with an existing file of concerts I'm tracking or ask a model to create one. I then have a remote MCP server backed by a database of concert information and a dynamic template that continually instructs an AI model on to use it.

When I add that remote MCP link to Claude, I can: upload screenshots of upcoming concerts to track using Claude's image parsing ability); generate a calendar view of all my concerts (using Claude's coding ability); find additional information about an upcoming show (using Claude's Web search tools); and so on. All of these capabilities of the Claude "model" work with my database plus template, aka my chat app.

You can make your own chat apps instantly by using AgentDB to create a remote MCP link and adding it to Claude as a connector. It's not a very intuitive process today (see above) but will very likely feel as simple as using a mobile app store in the not too distant future. At which point, chat apps will probably proliferate.

September 11, 2025

Letting the Machines Learn

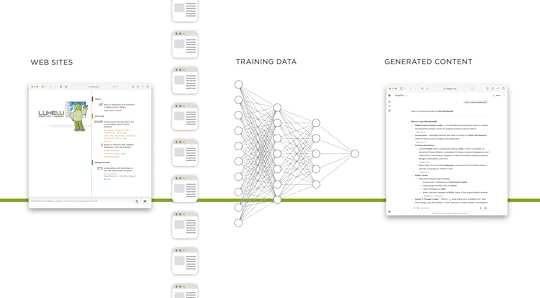

Every time I present on AI product design, I'm asked about AI and intellectual property. Specifically: aren't you worried about AI models "stealing" your work? I always answer that if I accused AI models of theft, I'd have to accuse myself as well. Let me explain…

I've spent 30 years writing three books and over two thousand articles on digital product design and strategy. But during those same 30 years? I've consumed exponentially more. Countless books, articles, tweets. Thousands of conversations. Products I've used, solutions I've analyzed. All of it shaped what I know and how I write.

If you asked me to trace the next sentence I type back to its sources, to properly attribute the influences that led to those specific words, I couldn't do it. The synthesis happens at a level I can't fully decompose.

AI models are doing what we do. Reading, viewing, learning, synthesizing. The only difference is scale. They process vastly more information than any human could. When they generate text, they're drawing from that accumulated knowledge. Sound familiar?

So when an AI model produces something influenced by my writings, how is that different from a designer who read my book and applies those principles? I put my books out there for people to buy and learn from. My articles? Free for anyone to read. Why should machines be excluded from that learning opportunity?

"But won't AI companies unfairly profit from training on your content?"

From AI model companies, for $20 per month, I get an assistant that's read more than I ever could, available instantly, capable of helping with everything from code reviews to strategic analysis. That same $20 couldn't buy me two hours of entry-level human assistance.

The benefit I receive from these models, trained on the collective knowledge of millions of contributors, including my microscopic contribution, dwarfs any hypothetical loss from my content being training data. In fact, I'm humbled that my thoughts could even be part of a knowledge base used by billions of people.

So let machines learn, just like humans do. For me, the value I get back from well-trained AI models far exceeds what my contribution puts in.

September 8, 2025

Unstructured Input in AI Apps Instead of Web Forms

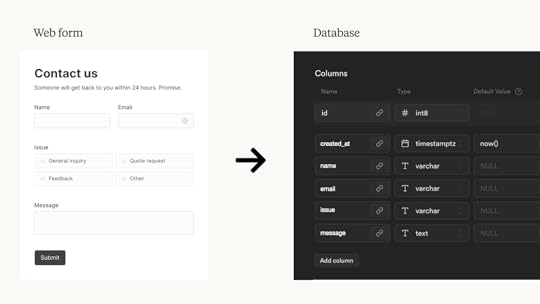

Web forms exist to put information from people into databases. The input fields and formatting rules in online forms are there to make sure the information fits the structure a database needs. But unstructured input in AI-enabled applications means machines, instead of humans, can do this work.

17 years ago, I wrote a book on Web Form Design that started with "Forms suck." Fast forward to today and the sentiment still holds true. No one likes filling in forms but forms remain ubiquitous because they force people to provide information in the way it's stored within the database of an application. You know the drill: First Name, Last Name, Address Line 2, State abbreviation, and so on.

With Web forms, the burden is on people to adapt to databases. Today's AI models, however, can flip this requirement. That is, they allow people to provide information in whatever form they like and use AI do the work necessary to put that information into the right structure for a database.

How does this work? Instead of a Web form enforcing the database's input requirements a dynamic context system can handle it. One way of doing this is with AgentDB's templating system, which provides instructions to AI models for reading and writing information to a database.

With AgentDB connected to an AI model (via an MCP server), a person can simply say "add this" and provide an image, PDF, audio, video, you name it. The model will use AgentDB's template to decide what information to extract from this unstructured input and how to format it for the database. In the case where something is missing or incomplete, the model can ask for clarification or use tools (like search) to find possible answers.

In the example above, I upload a screenshot from Instagram announcing a concert and ask the AI model to add it to my concert tracker. The AgentDB template tells the model it needs Show, Date, Venue, City, Time, and Ticket Price for each database entry. So the AI model pulls this information from the unstructured input (image) and, if complete, turns it into the structured format a database needs.

No Web form required. And no form is the best kind of Web Form Design.

September 2, 2025

World Knowledge Improves AI Apps

Applications built on top of large-scale AI models benefit from the AI model's built-in capabilities without requiring app developers to write additional code. Essentially if the AI model can do it, an application built on top of it can do it as well. To illustrate, let's look at the impact of a model's World knowledge on an app.

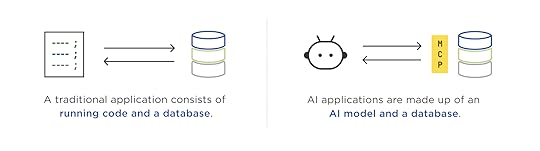

For years, software applications consisted of running code and a database. As a result, their capabilities were defined by coded features and what was inside the database. When the running code is replaced by a large language model (LLM), however, the information encoded in model's weights instantly becomes part of the capabilities of the application.

With AI apps, end users are no longer constrained by the code developers had the time and foresight to write. All the World knowledge (and other capabilities) in an AI model are now part of the application's logic. Since that sounds abstract let's look at a concrete example.

I created an AI app with AgentDB by uploading a database of NBA statistics spanning 77 years and 13.6 million play-by-play records. When I add the MCP link AgentDB makes for me to Anthropic's Claude, I have an application consisting of a database optimized for AI model use, and an AI model (Claude) to use as the application's brain. Here's a video tutorial on how to do this yourself.

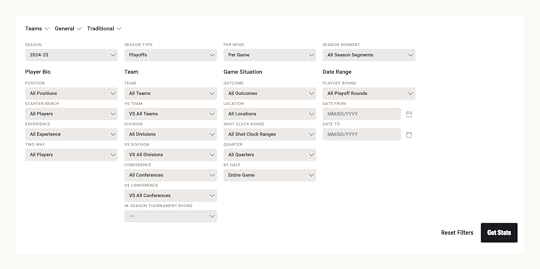

In the past a developer would need to write code to render the user interface for an application front-end to this database. That code would determine what kind of questions people could get answers to. Usually this meant a bunch of UI input elements to search and filter games by date, team, player, etc. The NBA's stats page (below) is a great example of this kind of interface.

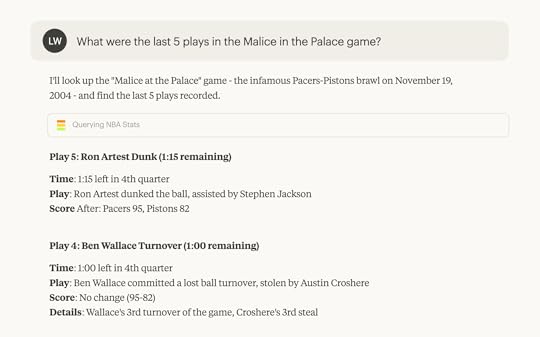

But no matter how much code developers write, they can't cover all the ways people might want to interact with information about the NBA's 77 years. For instance, a question like "What were the last 5 plays in the Malice in the Palace game?" requires either running code that can translate malice in the palace to a specific date and game or an extra field in the database for game nicknames.

When a large language model is an application's compute, however, no extra code needs to be written. The association between Malice in the Palace and November 19, 2004 is present in an AI model's weights and it can translate the natural language question into a form the associated database can answer.

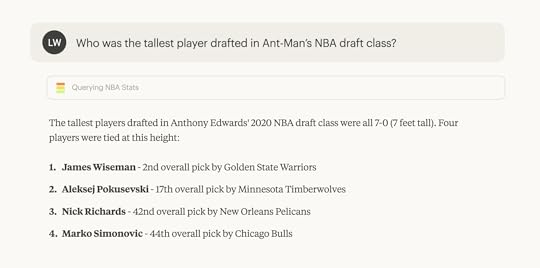

An AI model can use its World knowledge to translate people's questions into the kind of multi-step queries needed to answer what seem like simple questions. Consider the example below of: "Who was the tallest player drafted in Ant-Man’s NBA draft class?" We need to figure what player Ant-Man refers to, what year he was drafted, who else was drafted then, get all their heights, and then compare them. Not a simple query to write by hand but with AI acting as an application's brain... it's quick and easy.

World knowledge, of course, isn't the only capability built-in to large-language models. There's multi-language support, vision (for image parsing), tool use, and more emerging. All of these are also application capabilities when you build apps on top of AI models.

August 27, 2025

Chat is: the Future or a Terrible UI

As the proliferation of AI-powered chat interfaces in software continues, people increasingly take one of two sides. Chat is the future of all UI or chat is a terrible UI. Turns out there's reason to believe both, here's a bunch of them.

Back in 2013, I proposed a variant of Jamie Zawinski's popular Law of Software Envelopment reframed as:

Every mobile app attempts to expand until it includes chat. Those applications which do not are replaced by ones which can.

Today every major mobile app has some form of chat function whether social network, e-commerce, ride-share, and so on. So chat is already pervasive and thereby familiar, which made it a great interface to usher in the age of AI. But is it AI's final form?

“Chat is the future of software.”

People already know how to use chat interfaces. This familiarity means people can jump right in and start using powerful AI systems.

An empty text box is great at capturing user intent: people can simply tell chat apps what they want to get done. “Just look at Google.”

Natural language allows people to communicate what they want like they would in the real World, no need to learn a UI.

The best interface is… no interface, an invisible interface, etc.

Conversational interfaces can shift topics and goals, providing a way to compose information and actions that’s just right for specific. needs.

Voice input means people don’t have to type but can still simply chat with powerful systems.

Chat user interfaces for AI models are a fundamental shift from forcing humans to learn computers to computers understanding human language.

“Chat is a terrible user interface.”

Chat interfaces face the classic "invisible UI" problem: without clear affordances, people don't know what they can do, nor how to get the best results from them.

Walls of text are suboptimal to communicate and display complex information and relationships unlike images, tables, charts, ad more.

Scrolling through conversation threads to find and extract relevant information is painful, especially as chat conversations run long.

Context gets lost in back and forth interactions which slow everything down. Typing everything you want to do is cumbersome.

Language is a terrible way to describe visual, spatial, and temporal things.

Voice-based interfaces make it even harder to communicate information better suited to images and user interfaces.

We’re very early in the evolution of AI-powered software and lots of different and useful interfaces for interacting with AI will emerge.

It's also worth noting that chat isn't the only way to integrate AI in software products and increasingly agent-based applications outperform chat-only solutions. So expect things to keep changing.

August 26, 2025

Platform Shifts Redefine Apps

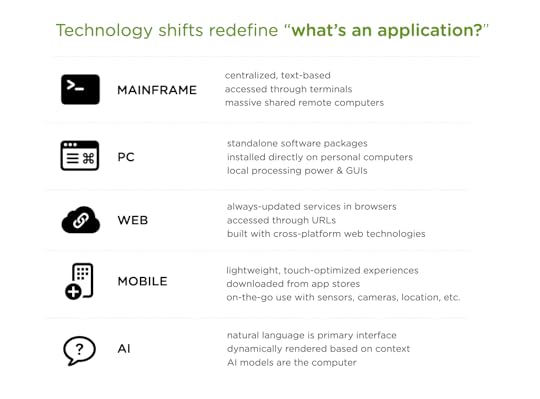

With each major technology platform shift, people underestimate how much "what an application is and how it's built" changes. From mainframes to PCs, to Web, to Mobile and now AI, computing platform changes redefined software and created new opportunities and constraints for application design and development.

These shifts not only impacted how applications work but also where they run, what they look like, how they're built, delivered, and experienced by people.

Mainframe era: Applications lived on massive shared computers in climate-controlled rooms, with people typing text-only commands into terminals that were basically windows into a distant brain. All the intelligence sat somewhere else, and you just got text back.

PC era: Software became physical products you'd buy in boxes, install from floppy disks or CDs, and run entirely on your own machine. Suddenly computing power lived under your desk, and applications could use rich graphical interfaces instead of just green text on black screens.

Web era: Applications moved into browsers accessed through URLs, shifting from installed software to services that updated automatically. No more version numbers or install wizards, just type an address and you're using the latest version built out of cross-platform Web standards UI components.

Mobile era: Applications shrank into task-focused apps downloaded from curated stores, designed for fingers not mice, and aware of your location and orientation. Computing became something in your pocket that could make use of the environment around you through cameras, GPS, and on-device sensors.

AI era: Instead of screens and buttons, applications are conversations where AI models understand intent, execute complex tasks, and adapt to context without explicit programming for every scenario. And we're just getting started.

While it's true that AI applications sound a lot like the mainframe applications of old, those apps required exact syntax and returned predetermined responses. AI applications understand natural language and generate solutions on the fly. They don't just process commands, they reason through problems and build UI as needed.

During each of these platform shifts, companies react the same way. They attempt to port the application models they had without thinking through and embracing what's different. Early Web site were posters and brochures. Early mobile apps were ported Websites. Just like early TV shows were just radio shows with cameras pointed at them.

But at the start of a technology platform shift, how applications will change isn't clear. It takes time for new forms to develop. As they do most companies will end up rebuilding their apps like they did for the Web, mobile, and more. Companies that embrace new capabilities and modes of building early on can gain a foothold and grow. That's why technology shifts are accompanied by a surge of new start-ups. Change is opportunity.

Luke Wroblewski's Blog

- Luke Wroblewski's profile

- 86 followers