MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 190

March 14, 2015

How many fingers did Anne Boleyn have?

History ExtraEmma McFarnon

Anne Boleyn. © Classic Image / Alamy There is no concrete evidence that Anne Boleyn had six fingers. George Wyatt, grandson of court poet and ambassador Sir Thomas Wyatt, made reference to an extra nail on one of Anne’s fingers, which may be plausible, although no other reference exists.

Anne Boleyn. © Classic Image / Alamy There is no concrete evidence that Anne Boleyn had six fingers. George Wyatt, grandson of court poet and ambassador Sir Thomas Wyatt, made reference to an extra nail on one of Anne’s fingers, which may be plausible, although no other reference exists.

Nicholas Sander, a Catholic Recusant who was living in exile during Elizabeth I's rule, went even further, describing Anne’s numerous deformities, including a sixth finger, effectively labelling her a witch. But Sander was writing with a political and religious agenda: he resented the schism with Rome, and his account was intended to taint not only Anne’s name, but Elizabeth’s as well.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).For more burning historical Q&As on the Tudors, ancient Rome, the First World War and ancient Egypt, click here.

Anne Boleyn. © Classic Image / Alamy There is no concrete evidence that Anne Boleyn had six fingers. George Wyatt, grandson of court poet and ambassador Sir Thomas Wyatt, made reference to an extra nail on one of Anne’s fingers, which may be plausible, although no other reference exists.

Anne Boleyn. © Classic Image / Alamy There is no concrete evidence that Anne Boleyn had six fingers. George Wyatt, grandson of court poet and ambassador Sir Thomas Wyatt, made reference to an extra nail on one of Anne’s fingers, which may be plausible, although no other reference exists.Nicholas Sander, a Catholic Recusant who was living in exile during Elizabeth I's rule, went even further, describing Anne’s numerous deformities, including a sixth finger, effectively labelling her a witch. But Sander was writing with a political and religious agenda: he resented the schism with Rome, and his account was intended to taint not only Anne’s name, but Elizabeth’s as well.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).For more burning historical Q&As on the Tudors, ancient Rome, the First World War and ancient Egypt, click here.

Published on March 14, 2015 06:24

History Trivia - the Equirria held in Campus Martius

March 14

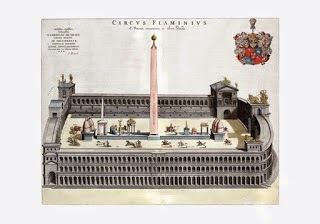

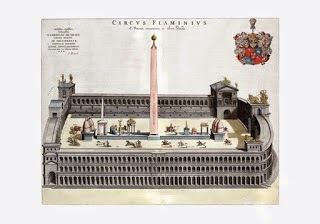

On this day the Equirria took place, which consisted of horse-racing in Campus Martius ("Field of Mars", Italian Campo Marzio; which was a publicly owned area of ancient Rome, about 490 acres) In 221 BC, the Circus Flaminius was built on the southern side of the Campus Martius, near the Tiber. This large track for chariot racing was named after Gaius Flaminius Nepos, who also constructed the Via Flaminia.

840 Einhard, historian and court scholar, and a friend of Charlemagne as well as his biographer, died.

1471 Sir Thomas Malory died. It is believed that Thomas Malory of Newbold Revell, Warwickshire, is the "Syr Thomas Maleore knyght" mentioned in the colophon to Le Morte Darthur, although there is no certain proof.

On this day the Equirria took place, which consisted of horse-racing in Campus Martius ("Field of Mars", Italian Campo Marzio; which was a publicly owned area of ancient Rome, about 490 acres) In 221 BC, the Circus Flaminius was built on the southern side of the Campus Martius, near the Tiber. This large track for chariot racing was named after Gaius Flaminius Nepos, who also constructed the Via Flaminia.

840 Einhard, historian and court scholar, and a friend of Charlemagne as well as his biographer, died.

1471 Sir Thomas Malory died. It is believed that Thomas Malory of Newbold Revell, Warwickshire, is the "Syr Thomas Maleore knyght" mentioned in the colophon to Le Morte Darthur, although there is no certain proof.

Published on March 14, 2015 02:00

March 13, 2015

Magna Carta exhibition is an 800-year-old lesson in people power

The Guardian

British Library showcase highlights value of enduringly popular document still relevant to everything from control orders to European integration

British Library showcase highlights value of enduringly popular document still relevant to everything from control orders to European integration

Demonstrators attack police vans during a protest against the poll tax in 1990. The British Library exhibition shows the Magna Carta as a call to stand up for your rights by any means necessary. Photograph: REX/REX

Demonstrators attack police vans during a protest against the poll tax in 1990. The British Library exhibition shows the Magna Carta as a call to stand up for your rights by any means necessary. Photograph: REX/REX

The most powerful work of art in the gripping Magna Carta exhibition portrays a king being attacked by peasants. They come at Henry I with scythe, fork and shovel, turning the tools of their daily work into crudely effective weapons.

This surreal masterpiece of medieval art is a depiction of a royal nightmare: uneasy lies the head that wears the crown. There was no revolution against Henry I, although a few generations later, in 1215, the reviled King John would be forced at swordpoint to grant freedoms to his people and the Magna Carta would be born.

Yet this superbly drawn illumination from the Chronicle of Worcester, dating from about 1140, portrays Henry menaced by the peasants in his sleep. It is said that he was plagued by nightmares after he broke promises to his people. In other scenes in this sinewy cartoon strip, Henry’s knights loom over his bed with their swords, and bishops raise their croziers threateningly over his unconscious form.

It is a startling window on early medieval Britain. Who knew that British kings so long ago had nightmares about revolution?

A 14th century scroll illustrating the geneolagy of King John 1199-1216 on show at the British Library. Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy, is not an art exhibition, though it has these terrific works of art in it. It is an exhibition about language and power, full of words, most of them written in a hand indecipherable by the untrained eye, on ancient pieces of parchment or paper. Somehow these manuscripts, charters, seals, declarations and statutes are as moving as any art. The Magna Carta, it turns out, still packs a mighty emotional punch.

A 14th century scroll illustrating the geneolagy of King John 1199-1216 on show at the British Library. Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy, is not an art exhibition, though it has these terrific works of art in it. It is an exhibition about language and power, full of words, most of them written in a hand indecipherable by the untrained eye, on ancient pieces of parchment or paper. Somehow these manuscripts, charters, seals, declarations and statutes are as moving as any art. The Magna Carta, it turns out, still packs a mighty emotional punch.

Two teeth and a finger bone belonging to John, extracted by antiquarians from his tomb in Worcester Cathedral, are this exhibition’s strangest relics. Together with a cast of his tomb effigy they testify to the enduring charisma of kingship. And yet this king was so hated for soaking his subjects for cash that in 1215 his own barons forced him to put his royal seal on a document limiting his power.

The Magna Carta is a document and a myth. But what is its real message? The wondrous array of materials here, which include an original copy of the US Bill of Rights lent by Congress, as well as a French revolutionary painting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, made me think that far from a venerable relic of the British middle way, the Magna Carta is a call to stand up for your rights by any means necessary.

Generations of jurists and libertarians have revered it as an ancient guarantor of freedom and justice. In a South African courtroom in 1964, Nelson Mandela stated his respect for the document. Yet the true lesson of Magna Carta’s history as revealed here is that rights have to be fought for and the roots of democracy are bloodsoaked.

A section of the Magna Carta that was found in a London tailor’s shop in the early 17th century. Photograph: Ray Tang/REX/Ray Tang/REX Why has the document to which John put his seal at Runnymede 800 years ago proved so uniquely enduring and rich as a political text? In this exhibition you can see the draft version that he agreed to: “King John concedes that he will arrest no man without judgement”. The words, surely, have endured because they are so simple and forthright – so medieval. We can scarcely imagine, the great historian Johann Huizinga pointed out, how simple, passionate, and rawly expressive people were in the middle ages. Such great simplicity makes the Magna Carta special: it is the great gift of the medieval mind to modern ones.

A section of the Magna Carta that was found in a London tailor’s shop in the early 17th century. Photograph: Ray Tang/REX/Ray Tang/REX Why has the document to which John put his seal at Runnymede 800 years ago proved so uniquely enduring and rich as a political text? In this exhibition you can see the draft version that he agreed to: “King John concedes that he will arrest no man without judgement”. The words, surely, have endured because they are so simple and forthright – so medieval. We can scarcely imagine, the great historian Johann Huizinga pointed out, how simple, passionate, and rawly expressive people were in the middle ages. Such great simplicity makes the Magna Carta special: it is the great gift of the medieval mind to modern ones.

We do not base modern politics on Plato’s Republic or Machiavelli’s Discourses but the Magna Carta is still quoted against everything from control orders to European integration. This bald document has more bite than all the classics of political thought. That is because it is not an abstract philosophical meditation on the nature of justice and freedom, but a blunt assertion of what rulers cannot do. The barons of 13th-century England gave human rights a tough, no-nonsense, visceral force.

A medieval sword, with an occult inscription on its blade, is on display among the illuminated manuscripts and royal seals to remind us that the Magna Carta was obtained through violence. The 13th-century Melrose Chronicle recognised that the Magna Carta turned the world upside down. It said: “The people desired to be masters of the king.”

British Library showcase highlights value of enduringly popular document still relevant to everything from control orders to European integration

British Library showcase highlights value of enduringly popular document still relevant to everything from control orders to European integration Demonstrators attack police vans during a protest against the poll tax in 1990. The British Library exhibition shows the Magna Carta as a call to stand up for your rights by any means necessary. Photograph: REX/REX

Demonstrators attack police vans during a protest against the poll tax in 1990. The British Library exhibition shows the Magna Carta as a call to stand up for your rights by any means necessary. Photograph: REX/REX The most powerful work of art in the gripping Magna Carta exhibition portrays a king being attacked by peasants. They come at Henry I with scythe, fork and shovel, turning the tools of their daily work into crudely effective weapons.

This surreal masterpiece of medieval art is a depiction of a royal nightmare: uneasy lies the head that wears the crown. There was no revolution against Henry I, although a few generations later, in 1215, the reviled King John would be forced at swordpoint to grant freedoms to his people and the Magna Carta would be born.

Yet this superbly drawn illumination from the Chronicle of Worcester, dating from about 1140, portrays Henry menaced by the peasants in his sleep. It is said that he was plagued by nightmares after he broke promises to his people. In other scenes in this sinewy cartoon strip, Henry’s knights loom over his bed with their swords, and bishops raise their croziers threateningly over his unconscious form.

It is a startling window on early medieval Britain. Who knew that British kings so long ago had nightmares about revolution?

A 14th century scroll illustrating the geneolagy of King John 1199-1216 on show at the British Library. Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy, is not an art exhibition, though it has these terrific works of art in it. It is an exhibition about language and power, full of words, most of them written in a hand indecipherable by the untrained eye, on ancient pieces of parchment or paper. Somehow these manuscripts, charters, seals, declarations and statutes are as moving as any art. The Magna Carta, it turns out, still packs a mighty emotional punch.

A 14th century scroll illustrating the geneolagy of King John 1199-1216 on show at the British Library. Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy, is not an art exhibition, though it has these terrific works of art in it. It is an exhibition about language and power, full of words, most of them written in a hand indecipherable by the untrained eye, on ancient pieces of parchment or paper. Somehow these manuscripts, charters, seals, declarations and statutes are as moving as any art. The Magna Carta, it turns out, still packs a mighty emotional punch. Two teeth and a finger bone belonging to John, extracted by antiquarians from his tomb in Worcester Cathedral, are this exhibition’s strangest relics. Together with a cast of his tomb effigy they testify to the enduring charisma of kingship. And yet this king was so hated for soaking his subjects for cash that in 1215 his own barons forced him to put his royal seal on a document limiting his power.

The Magna Carta is a document and a myth. But what is its real message? The wondrous array of materials here, which include an original copy of the US Bill of Rights lent by Congress, as well as a French revolutionary painting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, made me think that far from a venerable relic of the British middle way, the Magna Carta is a call to stand up for your rights by any means necessary.

Generations of jurists and libertarians have revered it as an ancient guarantor of freedom and justice. In a South African courtroom in 1964, Nelson Mandela stated his respect for the document. Yet the true lesson of Magna Carta’s history as revealed here is that rights have to be fought for and the roots of democracy are bloodsoaked.

A section of the Magna Carta that was found in a London tailor’s shop in the early 17th century. Photograph: Ray Tang/REX/Ray Tang/REX Why has the document to which John put his seal at Runnymede 800 years ago proved so uniquely enduring and rich as a political text? In this exhibition you can see the draft version that he agreed to: “King John concedes that he will arrest no man without judgement”. The words, surely, have endured because they are so simple and forthright – so medieval. We can scarcely imagine, the great historian Johann Huizinga pointed out, how simple, passionate, and rawly expressive people were in the middle ages. Such great simplicity makes the Magna Carta special: it is the great gift of the medieval mind to modern ones.

A section of the Magna Carta that was found in a London tailor’s shop in the early 17th century. Photograph: Ray Tang/REX/Ray Tang/REX Why has the document to which John put his seal at Runnymede 800 years ago proved so uniquely enduring and rich as a political text? In this exhibition you can see the draft version that he agreed to: “King John concedes that he will arrest no man without judgement”. The words, surely, have endured because they are so simple and forthright – so medieval. We can scarcely imagine, the great historian Johann Huizinga pointed out, how simple, passionate, and rawly expressive people were in the middle ages. Such great simplicity makes the Magna Carta special: it is the great gift of the medieval mind to modern ones.We do not base modern politics on Plato’s Republic or Machiavelli’s Discourses but the Magna Carta is still quoted against everything from control orders to European integration. This bald document has more bite than all the classics of political thought. That is because it is not an abstract philosophical meditation on the nature of justice and freedom, but a blunt assertion of what rulers cannot do. The barons of 13th-century England gave human rights a tough, no-nonsense, visceral force.

A medieval sword, with an occult inscription on its blade, is on display among the illuminated manuscripts and royal seals to remind us that the Magna Carta was obtained through violence. The 13th-century Melrose Chronicle recognised that the Magna Carta turned the world upside down. It said: “The people desired to be masters of the king.”

Published on March 13, 2015 06:01

Gothic wonder: 5 spectacular buildings of medieval England

History Extra

Emma McFarnon

The early medieval period was one of the greatest for English art and architecture. Here, Paul Binski from the University of Cambridge nominates five buildings that continue to inspire today

Day-to-day life in early medieval England was a largely humdrum affair, with the majority of people living in modest dwellings built from local materials. Yet between 1290 and 1350, amid the struggle of daily existence, teams of workers overseen by highly skilled artists challenged ideas of what could be accomplished in architecture, and pushed the boundaries to produce some of Europe’s most remarkable buildings.

Day-to-day life in early medieval England was a largely humdrum affair, with the majority of people living in modest dwellings built from local materials. Yet between 1290 and 1350, amid the struggle of daily existence, teams of workers overseen by highly skilled artists challenged ideas of what could be accomplished in architecture, and pushed the boundaries to produce some of Europe’s most remarkable buildings.

In his new book, Gothic Wonder: Art, Artifice and the Decorated Style, Paul Binski, professor of medieval art at the University of Cambridge, sheds new light on this pioneering period during which magnificent buildings like the cathedrals of Ely, Norwich and Canterbury were built to proclaim Christianity, and to convey statements about sovereignty with God, the Church and royalty. These constructions, which today dominate city skylines, played a pivotal role in medieval life, and caught the attention of artists and architects across Europe.

Here, writing for History Extra, Binski shares his top five masterpieces from this time period...

Ely CathedralI’d point first to Ely Cathedral, because I find the contrast between the isolation of the place in the Fens, and the power and inventiveness of its architecture, so amazing.

Ely seems out of the way, but in the Middle Ages it was one of England’s richest dioceses. So when after 1320 the bishop and monks decided to raise new buildings, they were well resourced. One of these was the new Lady Chapel, which I think is one of the most amazing interiors in medieval Europe because of its carved surfaces and ornateness – as if the stone had oozed and rippled out of the walls like a living thing, telling the story of the life and miracles of the Virgin Mary. The craftsmanship is outstanding.

And then you pass into the centre of the church to stand beneath the giant octagon, begun after the central tower fell in 1322 – quite possibly because it was undermined by the digging of the foundations of the Lady Chapel nearby! I found out that the octagon is almost the same height as Rome’s great Pantheon – about 43 metres high – and I suspect this was deliberate. It’s a Gothic dome. Apparently, craftsmen working as far as the south of France knew what the great masons of Ely were doing.

[image error]

Norwich CathedralUp the road from Ely is the quite wonderful cloister of Norwich Cathedral, one of the most entertaining and inventive places of its type: the cloister is huge and graceful, but what matters here is that the artisans responsible for it in around 1320 were making the most advanced Gothic arch shapes and patterns in Europe. You can find similar patterns in English embroidered vestments.

At Ely the carvings in the Lady Chapel were smashed after the Reformation, but at Norwich the cloister has a quite amazing, actually unique set of carved vault bosses telling Bible stories or just poking fun – a laundress berates a boy trying to steal her washing while buskers play musical instruments, and an acrobat hangs off the vaults as if about to fall.

Wells CathedralFor sheer beauty, the cathedral at Wells is amazing: its great west front full of figures and niches was studied by the Lady Chapel architects at Ely, but in the early 14th century the choir and east end were rebuilt in a way that shows the sophistication and subtlety of English art of the time.

A French Gothic church would be very tall and thin, but plain. Here instead every surface is covered in the most beautifully scaled and engineered detailing, including the incredible vaulting that looks like a great net stretched out over the carved under surface. These ‘net’ vaults amazed European architects, and you can find copies of them as far away as Prague. Wells, though obscure as a place, was an art centre recognised across Europe during this period. The English love of pattern triumphs.

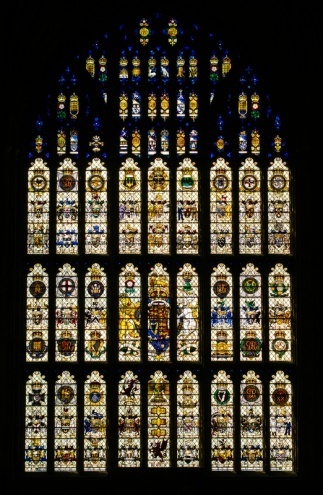

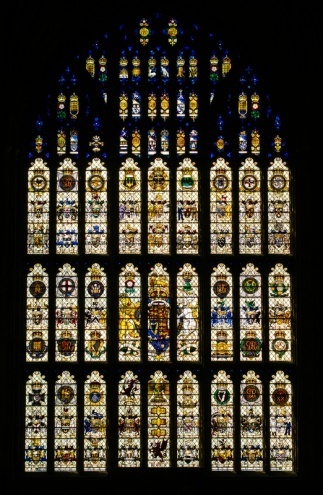

Gloucester CathedralI think the choir of Gloucester cathedral is one of the most elegant of all Gothic buildings. Again, like most English structures of the time it isn’t huge, but it is very refined.

In the middle of the 14th century the masons were providing a framework for the tomb of the murdered king Edward II, and used a type of stone cage-work to cover up the old dumpy Norman building underneath – it’s a sort of Gothic botox. You can follow the lines of the old building underneath the sparkling Gothic skin of stone. The effect is beautifully slender and crisp: here, a new style of Gothic emerges, called Perpendicular, which really took off as the form of churches and chapels in England in the later Middle Ages.

The most amazing feature of the choir is the huge window –at the time it was the largest single window in the known world, and it is still largely intact today. The English were brilliant at adapting, and so retaining their older cathedral buildings and breathing new life into them.

Westminster HallIn around 1393, right at the end of the period my book covers, King Richard II recast the interior of Westminster Hall in the Houses of Parliament with a single-span hammer beam roof. It narrowly escaped destruction in the fire that destroyed the old palace in 1834. Even in the Middle Ages it was famous – one writer says that Wookey Hole was as big as Westminster Hall, showing that it was a measure of hugeness.

The miracle here is not just its survival, but its courage – the largest timber span of its type anywhere in northern Europe done by a method that shows how inventive the English were in wood. The point holds true for the timber octagon at Ely, and perhaps even for the panelled effect of the interior of the choir at Gloucester.

The builders of these great structures had brilliant know-how, but also guts. A building fit for a king and, incidentally, one of England’s most important medieval shopping malls.

To find out more about Paul Binski’s Gothic Wonder: Art, Artifice and the Decorated Style (Yale Books, November 2014), click here.

Emma McFarnon

The early medieval period was one of the greatest for English art and architecture. Here, Paul Binski from the University of Cambridge nominates five buildings that continue to inspire today

Day-to-day life in early medieval England was a largely humdrum affair, with the majority of people living in modest dwellings built from local materials. Yet between 1290 and 1350, amid the struggle of daily existence, teams of workers overseen by highly skilled artists challenged ideas of what could be accomplished in architecture, and pushed the boundaries to produce some of Europe’s most remarkable buildings.

Day-to-day life in early medieval England was a largely humdrum affair, with the majority of people living in modest dwellings built from local materials. Yet between 1290 and 1350, amid the struggle of daily existence, teams of workers overseen by highly skilled artists challenged ideas of what could be accomplished in architecture, and pushed the boundaries to produce some of Europe’s most remarkable buildings.In his new book, Gothic Wonder: Art, Artifice and the Decorated Style, Paul Binski, professor of medieval art at the University of Cambridge, sheds new light on this pioneering period during which magnificent buildings like the cathedrals of Ely, Norwich and Canterbury were built to proclaim Christianity, and to convey statements about sovereignty with God, the Church and royalty. These constructions, which today dominate city skylines, played a pivotal role in medieval life, and caught the attention of artists and architects across Europe.

Here, writing for History Extra, Binski shares his top five masterpieces from this time period...

Ely CathedralI’d point first to Ely Cathedral, because I find the contrast between the isolation of the place in the Fens, and the power and inventiveness of its architecture, so amazing.

Ely seems out of the way, but in the Middle Ages it was one of England’s richest dioceses. So when after 1320 the bishop and monks decided to raise new buildings, they were well resourced. One of these was the new Lady Chapel, which I think is one of the most amazing interiors in medieval Europe because of its carved surfaces and ornateness – as if the stone had oozed and rippled out of the walls like a living thing, telling the story of the life and miracles of the Virgin Mary. The craftsmanship is outstanding.

And then you pass into the centre of the church to stand beneath the giant octagon, begun after the central tower fell in 1322 – quite possibly because it was undermined by the digging of the foundations of the Lady Chapel nearby! I found out that the octagon is almost the same height as Rome’s great Pantheon – about 43 metres high – and I suspect this was deliberate. It’s a Gothic dome. Apparently, craftsmen working as far as the south of France knew what the great masons of Ely were doing.

[image error]

Norwich CathedralUp the road from Ely is the quite wonderful cloister of Norwich Cathedral, one of the most entertaining and inventive places of its type: the cloister is huge and graceful, but what matters here is that the artisans responsible for it in around 1320 were making the most advanced Gothic arch shapes and patterns in Europe. You can find similar patterns in English embroidered vestments.

At Ely the carvings in the Lady Chapel were smashed after the Reformation, but at Norwich the cloister has a quite amazing, actually unique set of carved vault bosses telling Bible stories or just poking fun – a laundress berates a boy trying to steal her washing while buskers play musical instruments, and an acrobat hangs off the vaults as if about to fall.

Wells CathedralFor sheer beauty, the cathedral at Wells is amazing: its great west front full of figures and niches was studied by the Lady Chapel architects at Ely, but in the early 14th century the choir and east end were rebuilt in a way that shows the sophistication and subtlety of English art of the time.

A French Gothic church would be very tall and thin, but plain. Here instead every surface is covered in the most beautifully scaled and engineered detailing, including the incredible vaulting that looks like a great net stretched out over the carved under surface. These ‘net’ vaults amazed European architects, and you can find copies of them as far away as Prague. Wells, though obscure as a place, was an art centre recognised across Europe during this period. The English love of pattern triumphs.

Gloucester CathedralI think the choir of Gloucester cathedral is one of the most elegant of all Gothic buildings. Again, like most English structures of the time it isn’t huge, but it is very refined.

In the middle of the 14th century the masons were providing a framework for the tomb of the murdered king Edward II, and used a type of stone cage-work to cover up the old dumpy Norman building underneath – it’s a sort of Gothic botox. You can follow the lines of the old building underneath the sparkling Gothic skin of stone. The effect is beautifully slender and crisp: here, a new style of Gothic emerges, called Perpendicular, which really took off as the form of churches and chapels in England in the later Middle Ages.

The most amazing feature of the choir is the huge window –at the time it was the largest single window in the known world, and it is still largely intact today. The English were brilliant at adapting, and so retaining their older cathedral buildings and breathing new life into them.

Westminster HallIn around 1393, right at the end of the period my book covers, King Richard II recast the interior of Westminster Hall in the Houses of Parliament with a single-span hammer beam roof. It narrowly escaped destruction in the fire that destroyed the old palace in 1834. Even in the Middle Ages it was famous – one writer says that Wookey Hole was as big as Westminster Hall, showing that it was a measure of hugeness.

The miracle here is not just its survival, but its courage – the largest timber span of its type anywhere in northern Europe done by a method that shows how inventive the English were in wood. The point holds true for the timber octagon at Ely, and perhaps even for the panelled effect of the interior of the choir at Gloucester.

The builders of these great structures had brilliant know-how, but also guts. A building fit for a king and, incidentally, one of England’s most important medieval shopping malls.

To find out more about Paul Binski’s Gothic Wonder: Art, Artifice and the Decorated Style (Yale Books, November 2014), click here.

Published on March 13, 2015 05:47

Cnut's invasion of England: setting the scene for the Norman conquest

History Extra

The 1066 battle of Hastings is one of the most famous dates in medieval history. But it is often forgotten that the Norman conquest was preceded by another invasion of England some 50 years earlier – that led by Danish warrior Cnut in 1015–16. Here, medieval blogger Dr Eleanor Parker explains why we are wrong to overlook these events…

The 1066 battle of Hastings is one of the most famous dates in medieval history. But it is often forgotten that the Norman conquest was preceded by another invasion of England some 50 years earlier – that led by Danish warrior Cnut in 1015–16. Here, medieval blogger Dr Eleanor Parker explains why we are wrong to overlook these events…

In the summer of 1013, the Danish king Svein, accompanied by his son Cnut, launched an invasion of England – the first of the two successful conquests England would witness in the 11th century, but by far the less well known.

Scandinavian armies had been raiding in England on and off for more than 30 years, extracting huge sums of money from the country and putting King Æthelred under ever-increasing pressure, but Svein’s arrival in 1013 seems to have been something different – a carefully-planned, full-scale invasion. After years of raiding England, Svein knew enough about the English political situation to exploit its weaknesses: Æthelred's court was fractured by internal rivalries, a poisonous atmosphere attributed to the influence of his untrustworthy advisor Eadric, and Svein was able to make a strategic alliance with some of those who had fallen from the king's favour.

The invasion progressed with devastating speed: within a few weeks all the country north of Watling Street – the ancient dividing-line between the north and south of England – had submitted to the Danish king. Next the south was subdued by violence, and before the end of the year Æthelred and his family had been forced to flee to Normandy.

Svein, now king of England and Denmark, ruled from Christmas to Candlemas, but died suddenly on 3 February 1014. The Danish fleet chose Cnut to succeed him, but the English nobles had other ideas: they contacted Æthelred, still in refuge in Normandy, and invited him to come back as king. They said, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us, “that no lord could be dearer to them than their natural lord, if he would govern more justly than he had done before”. In response, Æthelred promised to be a better king, to forgive those who had deserted him, and to “remedy all the things of which they disapproved”. On these terms the agreement was made, and Æthelred returned to England. This time he managed to drive out Cnut, and the fleet went back to Denmark.

But a year later the young Danish king was back, hoping to repeat his father’s conquest. Despite his promises, Æthelred did not forgive those who had sided with the Danes: he viciously punished the northern leaders who had made an alliance with Svein, and in doing so caused his son, Edmund Ironside, to rebel against him. When Cnut returned in 1015, Æthelred was ill and England was divided: large parts of the country submitted to the Danes, while Edmund struggled to put an army together.

Only after Æthelred died in April 1016 did southern England finally unite behind Edmund, and six months of war followed, with the two armies fighting battles all over the south. The last was fought at a place called Assandun in Essex on 18 October 1016 – by strange coincidence, 50 years almost to the day before the battle of Hastings – and there the Danes were victorious. Edmund died six weeks later (likely by wounds received in battle or by disease, but some sources say he was murdered), and Cnut was finally sole king of England.

The immediate aftermath of Cnut's conquest was violent, although not much more so than the last years of Æthelred's reign. Potential opponents were summarily killed, and the remaining members of the royal family were driven into exile. Cnut married Æthelred's widow, Emma, sister of the duke of Normandy, and between them they founded a new dynasty – part Danish, part Norman, but presenting itself as English. There had been Danish kings ruling in England before, some of them famous Vikings whose names were still something to conjure with in the 11th century: Cnut's poets, extolling his conquest in Old Norse verse, compared him to the fearsome Ivar the Boneless and the sons of Ragnar Lothbrok, and in one sense, Cnut was heir to the conquests of these larger-than-life Danish kings.

But at the same time Cnut presented himself as a conciliatory conqueror, eager to learn from the land he had captured: by gifts to churches and monasteries he made amends for the damage his father and previous Danish kings had done, and he ruled in English and through English laws – even as his poets praised him for driving Æthelred's family out of England. When he made a diplomatic visit to Rome in 1027, he was welcomed as the Christian ruler of a new North Sea empire. Almost the only thing many people know about Cnut is that he made a grand display of his inability to control the tide, and this story – first recorded in the 12th century – is not quite as silly as it is sometimes assumed to be: power over the sea was the very basis of Cnut's authority, and a story in which Cnut yields that sea-power to God might have helped to explain the remarkable transformation of a Viking king into a Christian monarch.

When Cnut died in 1035, after ruling for nearly 20 years, he was buried in Winchester, the traditional seat of power of the kings of Wessex. His empire did not long survive him. After the early death of Harthacnut, Cnut’s son by Emma, Æthelred's son Edward regained the English throne – “as was his natural right”, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says. During his reign Edward had to deal with those, like Earl Godwine and his sons, who had risen to power under Cnut, but before long the impact of the Danish Conquest was to be overshadowed by the second, more famous conquest of the 11th century.

Compared to the Norman victory in 1066 – perhaps the single most famous date in medieval English history – the Danish Conquest has always seemed less important, with few enduring consequences. But the story of Svein’s well-planned invasion and Cnut’s successful reign tells us some interesting things about regional divisions within England, and England’s relationship with Scandinavia and the rest of Europe in the 11th century: in many ways – not least by destabilising the English monarchy and driving Edward into exile in Normandy – the Danish Conquest set the stage for much of what happened in 1066.

Dr Eleanor Parker is Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Anglo-Norman England at the University of Oxford. She blogs about medieval England at www.aclerkofoxford.blogspot.co.uk. You can follow her on Twitter @ClerkofOxford

The 1066 battle of Hastings is one of the most famous dates in medieval history. But it is often forgotten that the Norman conquest was preceded by another invasion of England some 50 years earlier – that led by Danish warrior Cnut in 1015–16. Here, medieval blogger Dr Eleanor Parker explains why we are wrong to overlook these events…

The 1066 battle of Hastings is one of the most famous dates in medieval history. But it is often forgotten that the Norman conquest was preceded by another invasion of England some 50 years earlier – that led by Danish warrior Cnut in 1015–16. Here, medieval blogger Dr Eleanor Parker explains why we are wrong to overlook these events…In the summer of 1013, the Danish king Svein, accompanied by his son Cnut, launched an invasion of England – the first of the two successful conquests England would witness in the 11th century, but by far the less well known.

Scandinavian armies had been raiding in England on and off for more than 30 years, extracting huge sums of money from the country and putting King Æthelred under ever-increasing pressure, but Svein’s arrival in 1013 seems to have been something different – a carefully-planned, full-scale invasion. After years of raiding England, Svein knew enough about the English political situation to exploit its weaknesses: Æthelred's court was fractured by internal rivalries, a poisonous atmosphere attributed to the influence of his untrustworthy advisor Eadric, and Svein was able to make a strategic alliance with some of those who had fallen from the king's favour.

The invasion progressed with devastating speed: within a few weeks all the country north of Watling Street – the ancient dividing-line between the north and south of England – had submitted to the Danish king. Next the south was subdued by violence, and before the end of the year Æthelred and his family had been forced to flee to Normandy.

Svein, now king of England and Denmark, ruled from Christmas to Candlemas, but died suddenly on 3 February 1014. The Danish fleet chose Cnut to succeed him, but the English nobles had other ideas: they contacted Æthelred, still in refuge in Normandy, and invited him to come back as king. They said, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us, “that no lord could be dearer to them than their natural lord, if he would govern more justly than he had done before”. In response, Æthelred promised to be a better king, to forgive those who had deserted him, and to “remedy all the things of which they disapproved”. On these terms the agreement was made, and Æthelred returned to England. This time he managed to drive out Cnut, and the fleet went back to Denmark.

But a year later the young Danish king was back, hoping to repeat his father’s conquest. Despite his promises, Æthelred did not forgive those who had sided with the Danes: he viciously punished the northern leaders who had made an alliance with Svein, and in doing so caused his son, Edmund Ironside, to rebel against him. When Cnut returned in 1015, Æthelred was ill and England was divided: large parts of the country submitted to the Danes, while Edmund struggled to put an army together.

Only after Æthelred died in April 1016 did southern England finally unite behind Edmund, and six months of war followed, with the two armies fighting battles all over the south. The last was fought at a place called Assandun in Essex on 18 October 1016 – by strange coincidence, 50 years almost to the day before the battle of Hastings – and there the Danes were victorious. Edmund died six weeks later (likely by wounds received in battle or by disease, but some sources say he was murdered), and Cnut was finally sole king of England.

The immediate aftermath of Cnut's conquest was violent, although not much more so than the last years of Æthelred's reign. Potential opponents were summarily killed, and the remaining members of the royal family were driven into exile. Cnut married Æthelred's widow, Emma, sister of the duke of Normandy, and between them they founded a new dynasty – part Danish, part Norman, but presenting itself as English. There had been Danish kings ruling in England before, some of them famous Vikings whose names were still something to conjure with in the 11th century: Cnut's poets, extolling his conquest in Old Norse verse, compared him to the fearsome Ivar the Boneless and the sons of Ragnar Lothbrok, and in one sense, Cnut was heir to the conquests of these larger-than-life Danish kings.

But at the same time Cnut presented himself as a conciliatory conqueror, eager to learn from the land he had captured: by gifts to churches and monasteries he made amends for the damage his father and previous Danish kings had done, and he ruled in English and through English laws – even as his poets praised him for driving Æthelred's family out of England. When he made a diplomatic visit to Rome in 1027, he was welcomed as the Christian ruler of a new North Sea empire. Almost the only thing many people know about Cnut is that he made a grand display of his inability to control the tide, and this story – first recorded in the 12th century – is not quite as silly as it is sometimes assumed to be: power over the sea was the very basis of Cnut's authority, and a story in which Cnut yields that sea-power to God might have helped to explain the remarkable transformation of a Viking king into a Christian monarch.

When Cnut died in 1035, after ruling for nearly 20 years, he was buried in Winchester, the traditional seat of power of the kings of Wessex. His empire did not long survive him. After the early death of Harthacnut, Cnut’s son by Emma, Æthelred's son Edward regained the English throne – “as was his natural right”, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says. During his reign Edward had to deal with those, like Earl Godwine and his sons, who had risen to power under Cnut, but before long the impact of the Danish Conquest was to be overshadowed by the second, more famous conquest of the 11th century.

Compared to the Norman victory in 1066 – perhaps the single most famous date in medieval English history – the Danish Conquest has always seemed less important, with few enduring consequences. But the story of Svein’s well-planned invasion and Cnut’s successful reign tells us some interesting things about regional divisions within England, and England’s relationship with Scandinavia and the rest of Europe in the 11th century: in many ways – not least by destabilising the English monarchy and driving Edward into exile in Normandy – the Danish Conquest set the stage for much of what happened in 1066.

Dr Eleanor Parker is Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Anglo-Norman England at the University of Oxford. She blogs about medieval England at www.aclerkofoxford.blogspot.co.uk. You can follow her on Twitter @ClerkofOxford

Published on March 13, 2015 05:41

History Trivia - British astronomer Frederick William Herschel discovers the planet Uranus

March 13

483 Felix III became pope. He repudiated the Henoticon, a deed of union originating with Patriarch Acacius of Constantinople and published by Emperor Zeno with the view of allaying the strife between the Miaphysite Christians and Chalcedonian Christians. This renunciation initiated the Acacian schism between the Eastern and Western Christian Churches that lasted thirty-five years.

607 12th recorded perihelion passage of Halley's Comet.

1781 British astronomer Frederick William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus

483 Felix III became pope. He repudiated the Henoticon, a deed of union originating with Patriarch Acacius of Constantinople and published by Emperor Zeno with the view of allaying the strife between the Miaphysite Christians and Chalcedonian Christians. This renunciation initiated the Acacian schism between the Eastern and Western Christian Churches that lasted thirty-five years.

607 12th recorded perihelion passage of Halley's Comet.

1781 British astronomer Frederick William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus

Published on March 13, 2015 02:00

March 12, 2015

History Trivia - Cesare Borgia killed

March 12

538 Witiges, king of the Ostrogoths ended his siege of Rome and retreated to Ravenna, leaving the city in the hands of the victorious Roman general, Belisarius.

604 Pope Gregory I died. Saint Gregory was the foremost influence in shaping the medieval papacy, and also reformed the mass, which enabled the development of the Gregorian Chant.

1507 Cesare Borgia was killed while fighting for the Navarrese king in the city of Viana, Spain.

538 Witiges, king of the Ostrogoths ended his siege of Rome and retreated to Ravenna, leaving the city in the hands of the victorious Roman general, Belisarius.

604 Pope Gregory I died. Saint Gregory was the foremost influence in shaping the medieval papacy, and also reformed the mass, which enabled the development of the Gregorian Chant.

1507 Cesare Borgia was killed while fighting for the Navarrese king in the city of Viana, Spain.

Published on March 12, 2015 02:00

March 11, 2015

Van Gogh landscape to be shown for first time in 100 years

The GuardianDalya Alberge

Van Gogh’s Moulin d’Alphonse was painted in Arles in southern France. The artist used paper as he wished to save his canvas to paint with his friend Paul Gauguin who was due to visit.

Van Gogh’s Moulin d’Alphonse was painted in Arles in southern France. The artist used paper as he wished to save his canvas to paint with his friend Paul Gauguin who was due to visit.

Experts expect Le Moulin d’Alphonse to fetch around $10m after research tying it directly to the artist via the records of his sister-in-law Johanna

A landscape by Vincent van Gogh is to be exhibited for the first time in more than 100 years following the discovery of crucial evidence that firmly traces back its history directly to the artist.

The significance of two handwritten numbers scribbled almost imperceptibly on the back had been overlooked until now. They have been found to correspond precisely with those on two separate lists of Van Gogh’s works drawn up by Johanna, wife of the artist’s brother, Theo.

Johanna, who was widowed in 1891 – months after Vincent’s death – singlehandedly generated interest in his art. She brought it to the attention of critics and dealers, organising exhibitions, although she obviously could never have envisaged the millions that his works would fetch today.

Le Moulin d’Alphonse Daudet à Fontvieille, which depicts vivid green grapevines leading up to a windmill with broken wings in the distance, is a work on paper that he created with graphite, reed pen and ink and watercolour shortly after he reached Arles, in the south of France.

It dates from 1888, two years before his untimely death. Windmills and vines were among his most beloved subjects.

Van Gogh, one of the greatest figures in Post-Impressionist painting, worked on paper as he excitedly awaited the arrival of his artist-friend, Paul Gauguin. He wrote to Theo that he wanted “canvas in reserve for the time when Gauguin comes”.

Research into Le Moulin d’Alphonse was conducted by James Roundell and Simon Dickinson, British art dealers, in collaboration with the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

They will be unveiling it at TEFAF Maastricht, arguably the world’s most prestigious art fair, opening in the Netherlands on Friday. They have set the price “in the region of $10m (£6.6m)”, which tallies with the figure fetched by a comparable work sold by Sotheby’s a decade ago. The vast majority are in public collections.

Roundell is a former head of Impressionist and Modern Pictures at Christie’s, whose sales of masterpieces have included Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, which broke the then record for a work of art when it sold in 1987 for nearly £25m.

Commenting on Le Moulin d’Alphonse, he said that the number “5”, in Johanna’s hand, relates to her 1902 list, while another number corresponds to her 1912 list. “So you’re getting a double reinforcement of lists that come direct from Johanna … I’m excited that we’re able to bring to light information about a drawing which really wasn’t known.”

He added: “Johanna was left with the life’s work of this artist, her brother-in-law who, in theory, she had mixed emotions about. But she set about trying to build … a legacy for him. She could have just burned the lot because, at that point, Van Gogh had no real market.”

Since its last exhibition in 1910 in Germany, the drawing – which measures 30.2 x 49 cm – has been hidden away in private European collections.

The dealers’ catalogue notes that Van Gogh arrived in Arles in 1888, exhausted and battling illness, writing to his sister that “I cannot prosper with either my work or my health in the winter”. He was immediately struck by the brilliant colours of the landscape, writing to a friend of “pale orange” sunsets, “which makes the fields appear blue”.

Most significantly, it was in Arles that Van Gogh developed as a draughtsman, producing some of his most exquisite works. In 1888, he wrote to his brother: “As for landscapes, I’m beginning to find that some, done more quickly than ever, are among the best things I do.”

Van Gogh’s Moulin d’Alphonse was painted in Arles in southern France. The artist used paper as he wished to save his canvas to paint with his friend Paul Gauguin who was due to visit.

Van Gogh’s Moulin d’Alphonse was painted in Arles in southern France. The artist used paper as he wished to save his canvas to paint with his friend Paul Gauguin who was due to visit. Experts expect Le Moulin d’Alphonse to fetch around $10m after research tying it directly to the artist via the records of his sister-in-law Johanna

A landscape by Vincent van Gogh is to be exhibited for the first time in more than 100 years following the discovery of crucial evidence that firmly traces back its history directly to the artist.

The significance of two handwritten numbers scribbled almost imperceptibly on the back had been overlooked until now. They have been found to correspond precisely with those on two separate lists of Van Gogh’s works drawn up by Johanna, wife of the artist’s brother, Theo.

Johanna, who was widowed in 1891 – months after Vincent’s death – singlehandedly generated interest in his art. She brought it to the attention of critics and dealers, organising exhibitions, although she obviously could never have envisaged the millions that his works would fetch today.

Le Moulin d’Alphonse Daudet à Fontvieille, which depicts vivid green grapevines leading up to a windmill with broken wings in the distance, is a work on paper that he created with graphite, reed pen and ink and watercolour shortly after he reached Arles, in the south of France.

It dates from 1888, two years before his untimely death. Windmills and vines were among his most beloved subjects.

Van Gogh, one of the greatest figures in Post-Impressionist painting, worked on paper as he excitedly awaited the arrival of his artist-friend, Paul Gauguin. He wrote to Theo that he wanted “canvas in reserve for the time when Gauguin comes”.

Research into Le Moulin d’Alphonse was conducted by James Roundell and Simon Dickinson, British art dealers, in collaboration with the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

They will be unveiling it at TEFAF Maastricht, arguably the world’s most prestigious art fair, opening in the Netherlands on Friday. They have set the price “in the region of $10m (£6.6m)”, which tallies with the figure fetched by a comparable work sold by Sotheby’s a decade ago. The vast majority are in public collections.

Roundell is a former head of Impressionist and Modern Pictures at Christie’s, whose sales of masterpieces have included Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, which broke the then record for a work of art when it sold in 1987 for nearly £25m.

Commenting on Le Moulin d’Alphonse, he said that the number “5”, in Johanna’s hand, relates to her 1902 list, while another number corresponds to her 1912 list. “So you’re getting a double reinforcement of lists that come direct from Johanna … I’m excited that we’re able to bring to light information about a drawing which really wasn’t known.”

He added: “Johanna was left with the life’s work of this artist, her brother-in-law who, in theory, she had mixed emotions about. But she set about trying to build … a legacy for him. She could have just burned the lot because, at that point, Van Gogh had no real market.”

Since its last exhibition in 1910 in Germany, the drawing – which measures 30.2 x 49 cm – has been hidden away in private European collections.

The dealers’ catalogue notes that Van Gogh arrived in Arles in 1888, exhausted and battling illness, writing to his sister that “I cannot prosper with either my work or my health in the winter”. He was immediately struck by the brilliant colours of the landscape, writing to a friend of “pale orange” sunsets, “which makes the fields appear blue”.

Most significantly, it was in Arles that Van Gogh developed as a draughtsman, producing some of his most exquisite works. In 1888, he wrote to his brother: “As for landscapes, I’m beginning to find that some, done more quickly than ever, are among the best things I do.”

Published on March 11, 2015 06:28

Following the success of the Richard III excavation, is it time to dig up other famous skeletons?

History ExtraEmma McFarnon

Rarely, in recent weeks, has archaeology been out of the history headlines: the coffin-within-a-coffin in Leicester that was found to contain a woman; the medieval bodies discovered underneath a Paris supermarket; and, of course, the countdown to Richard III’s reinterment at the end of March

Rarely, in recent weeks, has archaeology been out of the history headlines: the coffin-within-a-coffin in Leicester that was found to contain a woman; the medieval bodies discovered underneath a Paris supermarket; and, of course, the countdown to Richard III’s reinterment at the end of March

The remains of Richard III © the University of Leicester

These discoveries offer unique insights into the lives of individuals and populations past, helping us to understand where, when and how people once lived. British Museum curator, Alexandra Fletcher, last year wrote that human remains “advance knowledge of the history of disease, epidemiology and human biology…. [and offer] valuable insight into different cultural approaches to death, burial and beliefs.”

As in the case of Richard III, exhumations can also help to answer burning questions such as how the last Plantagenet king died (by two blows to the head and one to his pelvis), and from what conditions he suffered (scoliosis, malnutrition and a roundworm infection). We even know his probable hair colour (blonde, with blue eyes), and that he enjoyed a diet of swan, crane and heron!

What’s more, we are, as historian Dan Jones argued late last year, “better equipped to study historical remains than ever before”. Is it time, then, in pursuit of knowledge, to dig up other famous skeletons? Look inside, say, the urn in Westminster Abbey containing the supposed remains of the princes in the Tower; place a camera inside Elizabeth I's tomb?

There are, of course, a number of ethical issues to consider. As Mike Parker Pearson, Tim Schadla-Hall and Gabe Moshenska state in their 2011 paper ‘Resolving the Human Remains Crisis in British Archaeology’: “Given the powerful emotional, social and religious meanings attached to the dead body, it is perhaps unsurprising that human remains pose a distinctive set of ethical questions for archaeologists.” Likewise, Dan Jones points out that despite living in a “relatively secular age… we are so squeamish and prissy about meddling with the dead”.

Of particular importance is the treatment of human remains: as archaeologist Grahame Johnston writes, whereas in centuries past “the remains of native people and their artefacts were torn from their locations and displayed in foreign museums or sold to high-bidding collectors with little thought for the living descendents… [today] a more respectful approach of dealing with human remains has entered into the academic stream. It is now not uncommon to have a Rabbi, at least on-call, if not on-site, on major archaeological excavations in Israel.”

The issue is often complicated further by the fact people of varying traditions and faiths may prefer to treat remains differently. As The Economist explained in 2002: “However scientifically respectable their methods, archaeologists have been forced to acknowledge that they do not operate in a vacuum, and must take the values of others into account.” The British Museum echoed this sentiment when, last year, curator Alexandra Fletcher wrote: “There is no justification for the voyeuristic display of human remains simply as objects of morbid curiosity. As in storage, displays of human remains must acknowledge that the remains were once a living person and respect this fact.”

Queen Elizabeth I's tomb and monument by Maximilian Colt, 1603, in Westminster Abbey. © Angelo Hornak / Alamy

A second consideration, illustrated by the battle between the University of Leicester and the Plantagenet Alliance over where Richard III’s remains should be reburied, is ownership: to whom do newly discovered human remains – and artefacts – ‘belong’? The Economist writes: “Around the world, the general question of who has the first claim on buried items – local people, the descendants of the original owners or archaeologists – is deeply controversial.”

We ought also to consider whether there is sufficient justification for disturbing the resting places of famous skeletons. According to the ethical guidelines drawn up by the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology: “No burial should be disturbed without good reason. Archaeological excavation of burial grounds is normally carried out as a response to a threat to the cemetery due to modern development. Disturbance of unthreatened sites should only be contemplated if it is essential to an adequately funded, peer-reviewed research project orientated toward specific and well-justified research aims.”

And while we might be, in the words of Dan Jones, “better equipped than ever to glean new information from… long-dead bones”, surely future generations will be better prepared still? As the Council for British Archaeology states: “In many cases, it is better to wait, to leave objects and other evidence in the ground where it has been lying safely for hundreds or thousands of years. As long as it remains safe then it is better to leave the evidence for future generations to investigate with better techniques and with better-informed questions to ask.”

It is, says The Economist, “a central paradox of archaeology… discovery involves destruction; investigation requires intrusion. Where should archaeologists draw the line when deciding how much of an important site to excavate, if they are not to hinder future investigations?”

Rarely, in recent weeks, has archaeology been out of the history headlines: the coffin-within-a-coffin in Leicester that was found to contain a woman; the medieval bodies discovered underneath a Paris supermarket; and, of course, the countdown to Richard III’s reinterment at the end of March

Rarely, in recent weeks, has archaeology been out of the history headlines: the coffin-within-a-coffin in Leicester that was found to contain a woman; the medieval bodies discovered underneath a Paris supermarket; and, of course, the countdown to Richard III’s reinterment at the end of March

The remains of Richard III © the University of Leicester

These discoveries offer unique insights into the lives of individuals and populations past, helping us to understand where, when and how people once lived. British Museum curator, Alexandra Fletcher, last year wrote that human remains “advance knowledge of the history of disease, epidemiology and human biology…. [and offer] valuable insight into different cultural approaches to death, burial and beliefs.”

As in the case of Richard III, exhumations can also help to answer burning questions such as how the last Plantagenet king died (by two blows to the head and one to his pelvis), and from what conditions he suffered (scoliosis, malnutrition and a roundworm infection). We even know his probable hair colour (blonde, with blue eyes), and that he enjoyed a diet of swan, crane and heron!

What’s more, we are, as historian Dan Jones argued late last year, “better equipped to study historical remains than ever before”. Is it time, then, in pursuit of knowledge, to dig up other famous skeletons? Look inside, say, the urn in Westminster Abbey containing the supposed remains of the princes in the Tower; place a camera inside Elizabeth I's tomb?

There are, of course, a number of ethical issues to consider. As Mike Parker Pearson, Tim Schadla-Hall and Gabe Moshenska state in their 2011 paper ‘Resolving the Human Remains Crisis in British Archaeology’: “Given the powerful emotional, social and religious meanings attached to the dead body, it is perhaps unsurprising that human remains pose a distinctive set of ethical questions for archaeologists.” Likewise, Dan Jones points out that despite living in a “relatively secular age… we are so squeamish and prissy about meddling with the dead”.

Of particular importance is the treatment of human remains: as archaeologist Grahame Johnston writes, whereas in centuries past “the remains of native people and their artefacts were torn from their locations and displayed in foreign museums or sold to high-bidding collectors with little thought for the living descendents… [today] a more respectful approach of dealing with human remains has entered into the academic stream. It is now not uncommon to have a Rabbi, at least on-call, if not on-site, on major archaeological excavations in Israel.”

The issue is often complicated further by the fact people of varying traditions and faiths may prefer to treat remains differently. As The Economist explained in 2002: “However scientifically respectable their methods, archaeologists have been forced to acknowledge that they do not operate in a vacuum, and must take the values of others into account.” The British Museum echoed this sentiment when, last year, curator Alexandra Fletcher wrote: “There is no justification for the voyeuristic display of human remains simply as objects of morbid curiosity. As in storage, displays of human remains must acknowledge that the remains were once a living person and respect this fact.”

Queen Elizabeth I's tomb and monument by Maximilian Colt, 1603, in Westminster Abbey. © Angelo Hornak / Alamy

A second consideration, illustrated by the battle between the University of Leicester and the Plantagenet Alliance over where Richard III’s remains should be reburied, is ownership: to whom do newly discovered human remains – and artefacts – ‘belong’? The Economist writes: “Around the world, the general question of who has the first claim on buried items – local people, the descendants of the original owners or archaeologists – is deeply controversial.”

We ought also to consider whether there is sufficient justification for disturbing the resting places of famous skeletons. According to the ethical guidelines drawn up by the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology: “No burial should be disturbed without good reason. Archaeological excavation of burial grounds is normally carried out as a response to a threat to the cemetery due to modern development. Disturbance of unthreatened sites should only be contemplated if it is essential to an adequately funded, peer-reviewed research project orientated toward specific and well-justified research aims.”

And while we might be, in the words of Dan Jones, “better equipped than ever to glean new information from… long-dead bones”, surely future generations will be better prepared still? As the Council for British Archaeology states: “In many cases, it is better to wait, to leave objects and other evidence in the ground where it has been lying safely for hundreds or thousands of years. As long as it remains safe then it is better to leave the evidence for future generations to investigate with better techniques and with better-informed questions to ask.”

It is, says The Economist, “a central paradox of archaeology… discovery involves destruction; investigation requires intrusion. Where should archaeologists draw the line when deciding how much of an important site to excavate, if they are not to hinder future investigations?”

Published on March 11, 2015 06:20

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?

History Extra

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).

Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

For more burning historical Q&As on the Tudors, ancient Rome, the First World War and ancient Egypt, click here.

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

For more burning historical Q&As on the Tudors, ancient Rome, the First World War and ancient Egypt, click here.

Published on March 11, 2015 06:14