MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 187

March 24, 2015

History Trivia - James VI of Scotland becomes James I of England

March 24

1208 King John of England opposed Innocent III on his nomination for archbishop of Canterbury.

1550 France, England and Scotland signed the Peace of Boulogne, ending the War of the Rough Wooing (conflict between England and Scotland with the Scots receiving French military aid).

1603 Elizabeth I died and James VI of Scotland became James I of England, unifying the English and Scottish crowns.

1208 King John of England opposed Innocent III on his nomination for archbishop of Canterbury.

1550 France, England and Scotland signed the Peace of Boulogne, ending the War of the Rough Wooing (conflict between England and Scotland with the Scots receiving French military aid).

1603 Elizabeth I died and James VI of Scotland became James I of England, unifying the English and Scottish crowns.

Published on March 24, 2015 02:00

March 23, 2015

AudioBook Launch - Scribbler Tales (Volume Three)

Written by: Mary Ann Bernal Narrated by: Roberto Scarlato Length: 1 hr and 10 mins Unabridged Audiobook When a highly classified schematic of a prototype engine is stolen, the evidence points to an inside job, in "Hidden Lies". In "Nightmare", Melanie's childhood demons carry over into adulthood when she returns to her ancestral home. Detective Newport races against time to apprehend a killer targeting prosecuting attorneys in "Payback". "The Night Stalker" is not a figment of Pamela's imagination as she tries to convince the police that her life is in danger. Purchase on Audible

Written by: Mary Ann Bernal Narrated by: Roberto Scarlato Length: 1 hr and 10 mins Unabridged Audiobook When a highly classified schematic of a prototype engine is stolen, the evidence points to an inside job, in "Hidden Lies". In "Nightmare", Melanie's childhood demons carry over into adulthood when she returns to her ancestral home. Detective Newport races against time to apprehend a killer targeting prosecuting attorneys in "Payback". "The Night Stalker" is not a figment of Pamela's imagination as she tries to convince the police that her life is in danger. Purchase on Audible

Published on March 23, 2015 08:14

History Trivia - Handel's Messiah performed for the first time in London

March 23

752 Stephen's two-day pontificate began. Elected to succeed Zachary, Stephen II died before his consecration; earlier writers do not appear to have included him in the list of the popes; but, in accordance with the long standing practice of the Roman Church, he is now generally counted among them. This divergent practice has introduced confusion into the way of counting the Popes Stephen.

1743 Handel's Messiah was performed for the first time in London.

752 Stephen's two-day pontificate began. Elected to succeed Zachary, Stephen II died before his consecration; earlier writers do not appear to have included him in the list of the popes; but, in accordance with the long standing practice of the Roman Church, he is now generally counted among them. This divergent practice has introduced confusion into the way of counting the Popes Stephen.

1743 Handel's Messiah was performed for the first time in London.

Published on March 23, 2015 01:30

March 22, 2015

History Trivia - Order of the Knights Templar suppressed

March 22

1312 Order of the Knights Templar was suppressed.

1429 Joan of Arc dictated a warning to the English.

1457 Gutenberg Bible became the first printed book.

1312 Order of the Knights Templar was suppressed.

1429 Joan of Arc dictated a warning to the English.

1457 Gutenberg Bible became the first printed book.

Published on March 22, 2015 02:00

March 21, 2015

History Trivia - Cleopatra restored to the throne

March 21

47 BC, Julius Caesar defeated Ptolemy XII, Cleopatra's brother and rival, at Alexandria, Egypt, thus restoring Cleopatra to the throne.

717 Battle of Vincy between Charles Martel and Ragenfrid who returned defeated to Neustria. Instead of following the army immediately, Charles again used tactics he would use all his remaining life, in a career of absolute success. He took time to rally more men and prepare, before descending in full force. He chose where to provoke them to battle, and, at a place and time of his choosing, in Spring 717, Charles eventually followed them and dealt them a serious blow at Vincy on 21 March. He chased the fleeing king and mayor to Paris.

1152 Annulment of the marriage of King Louis VII of France and Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine. Eleanor retained control of Aquitaine and shortly thereafter wed Henry Plantagenet, who would become the next king of England.

47 BC, Julius Caesar defeated Ptolemy XII, Cleopatra's brother and rival, at Alexandria, Egypt, thus restoring Cleopatra to the throne.

717 Battle of Vincy between Charles Martel and Ragenfrid who returned defeated to Neustria. Instead of following the army immediately, Charles again used tactics he would use all his remaining life, in a career of absolute success. He took time to rally more men and prepare, before descending in full force. He chose where to provoke them to battle, and, at a place and time of his choosing, in Spring 717, Charles eventually followed them and dealt them a serious blow at Vincy on 21 March. He chased the fleeing king and mayor to Paris.

1152 Annulment of the marriage of King Louis VII of France and Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine. Eleanor retained control of Aquitaine and shortly thereafter wed Henry Plantagenet, who would become the next king of England.

Published on March 21, 2015 02:00

March 20, 2015

How did the Romans celebrate ‘Christmas’?

History Extra

It is today associated with decorations, gift giving and indulgence. But how did the Romans celebrate during the festive season? Dr Carey Fleiner, a senior lecturer in classical and medieval history at the University of Winchester, looks back at Saturnalia, the Roman mid-winter ‘festival of misrule’

It is today associated with decorations, gift giving and indulgence. But how did the Romans celebrate during the festive season? Dr Carey Fleiner, a senior lecturer in classical and medieval history at the University of Winchester, looks back at Saturnalia, the Roman mid-winter ‘festival of misrule’

Q: What was Saturnalia, and how was it celebrated?

A: It was the Romans’ mid-winter knees up!

It was a topsy-turvy holiday of feasting, drinking, singing in the street naked, clapping hands, gambling in public and making noise.

A character in Macrobius’s Saturnalia [an encyclopedic celebration of Roman culture written in the early fifth century] quotes from an unnamed priest of the god Saturn that, according to the god himself, during the Saturnalia “all things that are serious are barred”. So while it was a holy day, it was also very much a festive day as well.

The ordinarily rigid and conservative social restrictions of the Romans changed – for example, masters served their slaves during a feast and adults would serve children, and slaves were allowed to gamble.

And the aristocracy, who usually wore conservative clothes, dressed in brightly coloured fabrics such as red, purple and gold. This outfit was called the ‘synthesis’, which meant ‘to be put together’. They would ‘put together’ whatever clothes they wanted.

People would also wear a cap of freedom – the pilleum – which was usually worn by slaves who had been awarded their freedom, to symbolise that they were ‘free’ during the Saturnalia.

People would feast in their homes, but the historian Livy notes that by 217 BC there would also be a huge public feast at the oldest temple in Rome, the Temple of Saturn. Macrobius confirms this, and says that the rowdy participants would spill out onto the street, with the participants shouting, “Io Saturnalia!” the way we might greet people with ‘Merry Christmas!’ or ‘Happy New Year!’

A small statue of Saturn might be present at such feasts, as if Saturn himself were there. The statue of Saturn in the temple itself spent most of the year with its feet bound in woolen strips. On the feast day, these binds of wool wrapped around his feet were loosened – symbolising that the Romans were ‘cutting loose’ during the Saturnalia.

People were permitted to gamble in public and bob for corks in ice water. The author Aulus Gellius noted that, as a student, he and his friends would play trivia games. Chariot racing was also an important component of the Saturnalia and the associated sun-god festivities around that time – by the late fourth century AD there might be up to 36 races a day.

We say that during Christmas today the whole world shuts down – the same thing happened during the Saturnalia. There were sometimes plots to overthrow the government, because people were distracted – the famous conspirator Cataline had planned to murder the Senate and set the city on fire during the holiday, but his plan was uncovered and stopped by Cicero in 63 BC.

Saturnalia was described by first-century AD poet Gaius Valerius Catullus as “the best of times”. It was certainly the most popular holiday in the Roman calendar.

Q: Where does Saturnalia originate?

It was the result of the merging of three winter festivals over the centuries. These included the day of Saturn – the god of seeds and sowing – which was the Saturnalia itself. The dates for the Saturnalia shifted a bit over time, but it was originally held on 17 December.

Later, the 17th was given over to the Opalia, a feast day dedicated to Saturn’s wife – who was also his sister. She was the goddess of abundance and the fruits of the earth.

Because they were associated with heaven (Saturn) and Earth (Opalia), their holidays ended up combined, according again to Macrobius. And the third was a feast day celebrating the shortest day, called the bruma by the Romans. The Brumalia coincided with the solstice, on 21 or 22 December.

The three were merged, and became a seven-day jolly running from 17–23 December. But the emperor Augustus [who ruled from 27 BC–AD 14] shortened it to a three-day holiday, as it was causing chaos in terms of the working day.

Later, Caligula [ruled AD 37–41 ] extended it to a five-day holiday, and by the time of Macrobius [early fifth century] it had extended to almost two weeks.

As with so many Roman traditions, the origins of the Saturnalia are lost to the mists of time. The writer Columella notes in his book about agriculture [De Re Rustica, published in the early first century AD] that the Saturnalia came at the end of the agrarian year.

The festivities fell on the winter solstice, and helped to make up for the monotony of the lull between the end of the harvest and the beginning of the spring.

Q: Were gift-giving and decorations part of Saturnalia?

A: Saturnalia was more about a change in attitudes than presents. But a couple of gifts that were given were white candles, named cerei, and clay faces named sigillariae. The candles signified the increase of light after the solstice, while the sigillariae were little ornaments people exchanged.

These were sometimes hung in greenery as a form of decoration, and people would bring in holly and berries to honour Saturn.

Q: Was Saturnalia welcomed by everyone?

A: Not among the Romans!

Seneca [who died in AD 62] complained that the mob went out of control “in pleasantries”, and Pliny the Younger wrote in one of his letters that he holed up in his study while the rest of the household celebrated.

As might be expected, the early Christian authorities objected to the festivities as well.

It wasn’t until the late fourth century that the church fathers could agree on the date of Christ’s birth – unlike the pagan Romans, Christians tended to give no importance to anyone’s birthday. The big day in the Christian religious calendar was Easter.

Nevertheless, eventually the church settled on 25 December as the date of Christ’s nativity. For the Christians, it was a holy day, not a holiday, and they wanted the period to be sombre and distinguished from the pagan Saturnalia traditions such as gambling, drinking, and of course, most of all, worshipping a pagan god!

But their attempts to ban Saturnalia were not successful, as it was so popular. As late as the eighth century, church authorities complained that even people in Rome were still celebrating the old pagan customs associated with the Saturnalia and other winter holidays.

It is today associated with decorations, gift giving and indulgence. But how did the Romans celebrate during the festive season? Dr Carey Fleiner, a senior lecturer in classical and medieval history at the University of Winchester, looks back at Saturnalia, the Roman mid-winter ‘festival of misrule’

It is today associated with decorations, gift giving and indulgence. But how did the Romans celebrate during the festive season? Dr Carey Fleiner, a senior lecturer in classical and medieval history at the University of Winchester, looks back at Saturnalia, the Roman mid-winter ‘festival of misrule’Q: What was Saturnalia, and how was it celebrated?

A: It was the Romans’ mid-winter knees up!

It was a topsy-turvy holiday of feasting, drinking, singing in the street naked, clapping hands, gambling in public and making noise.

A character in Macrobius’s Saturnalia [an encyclopedic celebration of Roman culture written in the early fifth century] quotes from an unnamed priest of the god Saturn that, according to the god himself, during the Saturnalia “all things that are serious are barred”. So while it was a holy day, it was also very much a festive day as well.

The ordinarily rigid and conservative social restrictions of the Romans changed – for example, masters served their slaves during a feast and adults would serve children, and slaves were allowed to gamble.

And the aristocracy, who usually wore conservative clothes, dressed in brightly coloured fabrics such as red, purple and gold. This outfit was called the ‘synthesis’, which meant ‘to be put together’. They would ‘put together’ whatever clothes they wanted.

People would also wear a cap of freedom – the pilleum – which was usually worn by slaves who had been awarded their freedom, to symbolise that they were ‘free’ during the Saturnalia.

People would feast in their homes, but the historian Livy notes that by 217 BC there would also be a huge public feast at the oldest temple in Rome, the Temple of Saturn. Macrobius confirms this, and says that the rowdy participants would spill out onto the street, with the participants shouting, “Io Saturnalia!” the way we might greet people with ‘Merry Christmas!’ or ‘Happy New Year!’

A small statue of Saturn might be present at such feasts, as if Saturn himself were there. The statue of Saturn in the temple itself spent most of the year with its feet bound in woolen strips. On the feast day, these binds of wool wrapped around his feet were loosened – symbolising that the Romans were ‘cutting loose’ during the Saturnalia.

People were permitted to gamble in public and bob for corks in ice water. The author Aulus Gellius noted that, as a student, he and his friends would play trivia games. Chariot racing was also an important component of the Saturnalia and the associated sun-god festivities around that time – by the late fourth century AD there might be up to 36 races a day.

We say that during Christmas today the whole world shuts down – the same thing happened during the Saturnalia. There were sometimes plots to overthrow the government, because people were distracted – the famous conspirator Cataline had planned to murder the Senate and set the city on fire during the holiday, but his plan was uncovered and stopped by Cicero in 63 BC.

Saturnalia was described by first-century AD poet Gaius Valerius Catullus as “the best of times”. It was certainly the most popular holiday in the Roman calendar.

Q: Where does Saturnalia originate?

It was the result of the merging of three winter festivals over the centuries. These included the day of Saturn – the god of seeds and sowing – which was the Saturnalia itself. The dates for the Saturnalia shifted a bit over time, but it was originally held on 17 December.

Later, the 17th was given over to the Opalia, a feast day dedicated to Saturn’s wife – who was also his sister. She was the goddess of abundance and the fruits of the earth.

Because they were associated with heaven (Saturn) and Earth (Opalia), their holidays ended up combined, according again to Macrobius. And the third was a feast day celebrating the shortest day, called the bruma by the Romans. The Brumalia coincided with the solstice, on 21 or 22 December.

The three were merged, and became a seven-day jolly running from 17–23 December. But the emperor Augustus [who ruled from 27 BC–AD 14] shortened it to a three-day holiday, as it was causing chaos in terms of the working day.

Later, Caligula [ruled AD 37–41 ] extended it to a five-day holiday, and by the time of Macrobius [early fifth century] it had extended to almost two weeks.

As with so many Roman traditions, the origins of the Saturnalia are lost to the mists of time. The writer Columella notes in his book about agriculture [De Re Rustica, published in the early first century AD] that the Saturnalia came at the end of the agrarian year.

The festivities fell on the winter solstice, and helped to make up for the monotony of the lull between the end of the harvest and the beginning of the spring.

Q: Were gift-giving and decorations part of Saturnalia?

A: Saturnalia was more about a change in attitudes than presents. But a couple of gifts that were given were white candles, named cerei, and clay faces named sigillariae. The candles signified the increase of light after the solstice, while the sigillariae were little ornaments people exchanged.

These were sometimes hung in greenery as a form of decoration, and people would bring in holly and berries to honour Saturn.

Q: Was Saturnalia welcomed by everyone?

A: Not among the Romans!

Seneca [who died in AD 62] complained that the mob went out of control “in pleasantries”, and Pliny the Younger wrote in one of his letters that he holed up in his study while the rest of the household celebrated.

As might be expected, the early Christian authorities objected to the festivities as well.

It wasn’t until the late fourth century that the church fathers could agree on the date of Christ’s birth – unlike the pagan Romans, Christians tended to give no importance to anyone’s birthday. The big day in the Christian religious calendar was Easter.

Nevertheless, eventually the church settled on 25 December as the date of Christ’s nativity. For the Christians, it was a holy day, not a holiday, and they wanted the period to be sombre and distinguished from the pagan Saturnalia traditions such as gambling, drinking, and of course, most of all, worshipping a pagan god!

But their attempts to ban Saturnalia were not successful, as it was so popular. As late as the eighth century, church authorities complained that even people in Rome were still celebrating the old pagan customs associated with the Saturnalia and other winter holidays.

Published on March 20, 2015 04:00

History Trivia - Thomas Seymour executed

March 20

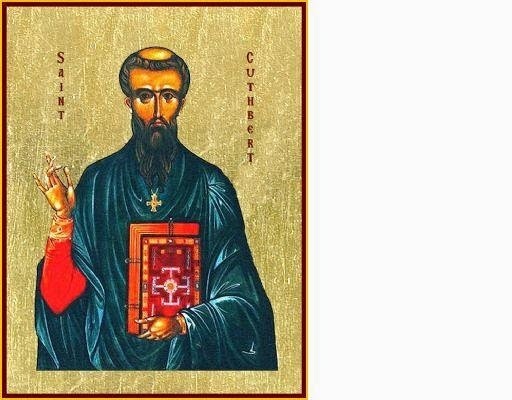

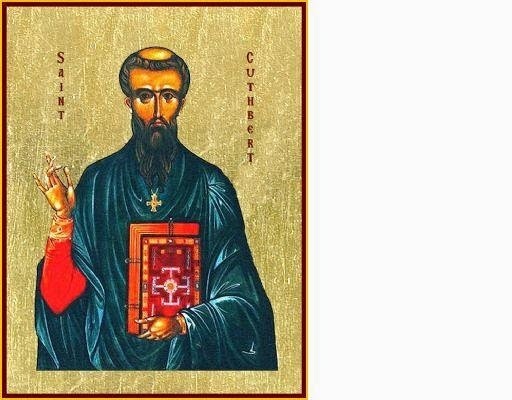

687 Saint Cuthbert, a shepherd and hermit who achieved fame as a holy man, healer, and bishop, died.

1345 Saturn/Jupiter/Mars-conjunction was thought to have been the caused the plague epidemic.

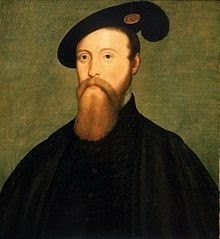

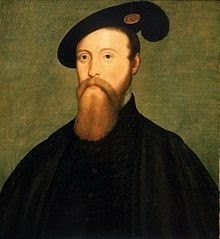

1549 Thomas Seymour was executed. Seymour had married Henry VIII's widow Katherine Parr and pursued the young princess Elizabeth without success. When his piratical activities were discovered he was arrested, tried, and executed.

687 Saint Cuthbert, a shepherd and hermit who achieved fame as a holy man, healer, and bishop, died.

1345 Saturn/Jupiter/Mars-conjunction was thought to have been the caused the plague epidemic.

1549 Thomas Seymour was executed. Seymour had married Henry VIII's widow Katherine Parr and pursued the young princess Elizabeth without success. When his piratical activities were discovered he was arrested, tried, and executed.

Published on March 20, 2015 02:00

March 19, 2015

Dormice, ostrich meat and fresh fish: the surprising foods eaten in ancient Rome

Banquet at a wealthy home in ancient Rome. © North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy History Extra

Banquet at a wealthy home in ancient Rome. © North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy History ExtraArchaeologists exploring sewers and cesspits at Herculaneum in 2013 made the startling discovery that, contrary to the long-held belief that ancient Romans survived on a basic diet of bread and olive oil, they in fact enjoyed a rich variety of fish, fruit, and spicy dishes. Now, as part of our Ancient Rome Week, Dr Erica Rowan, one of the archeologists involved in the project, tells you everything you need to know about ancient Roman culinary habits…

We often think of the Mediterranean triad – bread, wine and olive oil – as the diet of most Romans, but in fact food in ancient Rome was much more diverse. And within each food type there was a range of goods suited to fit every financial budget: cheap local plonk or expensive Falernian wine from the Bay of Naples; home grown pot-herbs or exotic seasonings from India, and traditional salted pork or the coveted salted tuna from Spain. Consumption practices in ancient Rome, too, ranged from the traditional to the truly exotic.

Conversely, another myth surrounding Roman food and eating practices claims the Romans held elaborate banquets where bears, smelly fish sauce and even dormice were eaten. The exaggeration and perpetuation of these stories is primarily due to the fact that the Romans themselves were, on occasion, both fascinated and disgusted by their own eating habits, and so wrote them down.

The works of these ancient authors, usually elite men, were then copied by monks in the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods, and have eventually found their way to us: today, for example, you can buy recipe books based on the works of Apicius. Although the real Apicius lived during the 1st century, the recipes are actually a compilation that was published sometime during the 4th century AD. Here’s one of the recipes for a sauce to serve with boiled ostrich meat:

“Pepper, mint, roasted cumin, celery seed, long or round dates, honey, vinegar, passum (raisin wine), liquamen (fish sauce) and a little oil. Put in a pan and bring to the boil. Thicken it with starch and in this state pour over the pieces of ostrich on a serving dish and sprinkle with pepper…” Recipe 6.1

Are the ingredients in these recipes really what people in ancient Rome and Italy were eating? You may be surprised to find out that the answer is yes. Sort of...

For centuries the foods and recipes discussed by ancient authors were all the information we had about Roman diet. More recently, the field of environmental archaeology, which includes the sub-disciplines of archaeobotany and zooarchaeology (the study of ancient plant remains and animal bones respectively), has been able to provide us with a wealth of new information: bones and soil samples collected during archaeological excavations in places such as Pompeii and Herculaneum have led to the recovery of foodstuffs such as fish bones, peppercorns and mint seeds. Consequently, we are now able to discuss with much more precision the diet in ancient Rome and Italy.

Mineralised mint seed from Herculaneum, AD79. © Erica Rowan

As the centre of an enormous empire, Rome attracted goods and foods from the provinces and beyond. In theory it was possible to either purchase or import even the most exotic goods, such as ostrich. The Romans had very few food taboos, so anything could be tried at least once. Yet, similar to many other ancient societies, what you ate in ancient Rome depended upon what you could afford.

Food for saleOnly the wealthiest inhabitants were able to pay for exotic meats, and even then, they probably ate them only very rarely. More affordable – and far more common – meat included sheep, goat, chicken, and especially pork. Fresh meat, which was expensive, came from animals brought in from the surrounding countryside and butchered in the city. Salted pork, because it could travel farther and preserve longer, was less expensive, and would have been the type of meat consumed by all but the very poorest.

Fresh fish would have been similarly expensive, as it had to be brought up the Tiber from the sea each day. Salted fish, or the famous Roman fermented fish sauce (liquamen or garum), would again be much more common and inexpensive. Fish sauce was not made in Rome, but was imported in large ceramic vessels called amphorae from Spain, North Africa and even the Black Sea.

Fresh fruits and vegetables came from Rome’s hinterland, and were brought into Rome to be sold in markets. Price fluctuated based on what was in season, but in general, the most popular fruits were grapes, olives, figs, apples, pears, pomegranates and blackberries. Peaches were an expensive fruit, only introduced into Italy in the mid 1st century AD. Common vegetables included cabbage, onion, garlic, lettuce and leeks. Moreover, people could buy several different types of nuts, including hazelnuts, walnuts, chestnuts, almonds and pine nuts.

Thus far, this description of food in Rome could probably be applied to any city in Roman Italy. Yet unlike many small towns and cities, Rome’s size made it a logistical challenge with regards to food supply: in the 1st century AD, Rome had a population of approximately one million people, and it had grown too big to be supplied exclusively by its hinterland.

Traditionally, the staple of the Roman diet was wheat: large bakeries in Rome’s port town, Ostia, attest to the fact that most Romans ate much of their wheat as bread. And we know from ancient texts and inscriptions that grain was imported in huge ships from Egypt and North Africa.

Yet food finds in 2013 from Herculaneum, a city on the Bay of Naples destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, suggest the Romans ate more than just wheat. At Herculaneum there is evidence of the consumption of both foxtail and broomcorn millet, and the different quantities of wheat and millet finds indicate that while wheat was often turned into bread, other cereals (including emmer wheat) were eaten as a porridge or stew. The Romans also ate lentils, chickpeas, beans and peas. The Murecine tablets [a collection of wooden writing tablets, found in a villa just outside Pompeii in an area now called the ‘Agro Murecine’], also buried during the eruption of Vesuvius, record that many of these pulses were imported from Egypt.

Taste and flavourAs we do today, Romans included a multitude of seasonings in their dishes: cumin, coriander, sesame and mint seeds have been found in Herculaneum, as have dill, fennel and poppy seeds. In fact, the Romans went to great lengths to flavour dishes. Black pepper, which has also been found in Rome, Herculaneum and even Roman London, was imported from the south-western coast of India in Roman times. In a journey that took several months, the black pepper was shipped across the Indian Ocean, up the Red Sea, along the Nile to Alexandria before being put on a boat and sent to Rome. It appears in many of Apicius’ recipes, including the one below for sea urchins:

“Take a new porridge pan, add a little oil, liquamen, sweet wine, ground pepper; bring it to heat. When it is simmering put the sea urchins in one at a time. Stir them and bring them to the boil three times. When they are cooked, sprinkle with pepper and serve.” Recipe 9.8.1

Sea urchin spine and body fragment from Herculaneum, AD79. © Erica Rowan

Every single item in the above recipe can be attested to archaeologically: all the ingredients were recovered from a single sewer that ran beneath a shop and housing complex inhabited by those of moderate means in Herculaneum.

It is clear from the numerous modern cookbooks, blogs and museum exhibits that Roman food continues to inspire our culinary practices today. Lastly, and just to set the record straight, there is no archaeological evidence of bear consumption in ancient Rome, and Roman fish sauce is comparable to modern Thai fish sauce and was used simply to salt and flavour dishes, not to make them taste fishy.

Finally, while the Romans really did eat dormice (although how often is debated), dormice are not the same species as the small white mice that get into your house and scurry across the floor today!

Dr Erica Rowan is an associate research fellow at the University of Exeter whose main research interests are in the areas of Roman food, nutrition and health. To find out more about the 2013 exploration of sewers and cesspits at Herculaneum, click here.

Published on March 19, 2015 08:32

In case you missed it... The A to Z of life in Pompeii

Emma McFarnon

History Extra

Buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, and gradually disinterred from the middle of the 18th century, Pompeii is probably the world’s most famous archaeological site. But what was life like for the Romans who lived there, pre-eruption? Not that different from our own, as Mary Beard reveals in her A to Z of the ancient town, complete with yob culture, nightlife and plonk.

Buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, and gradually disinterred from the middle of the 18th century, Pompeii is probably the world’s most famous archaeological site. But what was life like for the Romans who lived there, pre-eruption? Not that different from our own, as Mary Beard reveals in her A to Z of the ancient town, complete with yob culture, nightlife and plonk.

This article was first published in BBC History Magazine in 2008

A

is for artists at work

House makeovers? Style gurus? Des res? Painters and decorators did a roaring trade in Pompeii, transforming dark and often pokey interiors with a lavish coat of paint much as they do today. And we now have a precious glimpse of how the painters operated.

In one house, recently uncovered, a team of three or four decorators were interrupted by the eruption almost in mid-brush stroke, scarpering as the ash fell and abandoning their tools, 50 pots of paints, and a bucket of fresh plaster precariously balanced up a ladder. The assistants had been busy slapping on the plaster and the broad washes of colour, while the masters had drawn out the design in rough sketches and were painting the figures and the fiddly bits.

B

is for banking

The Romans didn’t have cheques or credit cards, but there were money lenders, the banks of the day. The most famous Pompeian banker is Lucius Caecilius Jucundus (now best known as the hero of the early parts of the Cambridge Latin Course).

Some of his records and receipts, stashed away in the attic of his house, give an idea of his business activities. Banker is actually a bit of a euphemism – he was mainly an auctioneer profiting on both sides of the transaction, charging the seller a commission and then lending money to the buyer at a healthy rate of interest.

C

is for cafe culture

The latest estimate reckons that there were about 200 cafes and bars in the town altogether – about one for every 60 residents. A counter usually ran along the street to catch the passing trade, selling cheap takeaway food from large jars.

Wine was stacked up behind it and there were tables in a back room for sit-down eating and drinking. It was the reverse of today’s society, where the rich eat out and the poor cook up at home. In Pompeii, the poor, living in tiny quarters with no facilities, relied on cafe food.

D

is for diet (and dormice)

Rich Pompeians did occasionally eat dormice. Or so a couple of strange pottery containers – identified, thanks to descriptions by ancient writers, as dormouse cages – suggest. But elaborate banquets were a rarity and just for the rich.

The staples were bread, olives, beans, eggs, cheese, fruit and veg (Pompeian cabbages were particularly prized), plus some tasty fish. Meat was less in evidence, and was mainly pork. This was a relatively healthy diet. In fact, the ancient Pompeians were on average slightly taller than modern Neapolitans.

E

is for education, education, education

One of the puzzles of Pompeii is where the kids went to school. No obvious school buildings or classrooms have been found. The likely answer is that teachers took their class of boys (and almost certainly only boys) to some convenient shady portico and did their teaching there.

A wonderful series of paintings of scenes of life in the Forum seems to show exactly that happening – with one poor miscreant being given a nasty beating in front of his classmates. And the curriculum? To judge from the large number of quotes from Virgil’s Aeneid scrawled on Pompeian walls, the young were well drilled in the national epic.

F

is for faith communities

The official religion of the town sponsored solemn sacrifices and raucous festivals celebrating Jupiter, Apollo, Venus and the Roman emperor, who was to all intents and purposes a god himself. But alongside this, happily co-existing so far as we can tell, were all kinds of other religions.

One of the most impressive sights at Pompeii is the little temple of the Egyptian goddess Isis, once tended by its white-clad, shaven-headed priests. We have evidence, too, for Jews and worshippers of Cybele, known as the Great Mother.

There is no clear sign of any Christians, but in one house an ivory statuette of the Indian goddess Lakshmi has turned up. Souvenir, curiosity or object of devotion? Nobody knows.

G

is for garum

No Roman cooking was complete without garum – a disgusting concoction of rotten fish. A more generous interpretation sees it as a version of the spicy fish sauces that are part of modern Thai cooking, and it was popular in Pompeii, which had at least one garum shop. One of its richest families made its fortune in the trade – and advertised the fact by decorating their front hall with a design of garum jars in mosaic. Garum traders were canny businessmen, with an eye on different markets. A kosher version (guaranteed to contain no shellfish) was produced for the local Jewish community.

H

is for hygiene

Pompeii boasted at least six public bathing complexes – some owned by the city council, some by private enterprise operations. Only a few of the very richest houses had their own facilities. The vast majority of the population would have exercised, scraped down, sweated and taken a dip in one of the communal establishments.

As you might imagine, they were hotbeds of germs and infection. The plunge pools had limited water circulation, no chlorination and must have been full of the usual sort of human effluent. Ancient doctors recommended not going to the baths with an open wound – it could lead to gangrene.

I

is for illness

Illness struck the young hard. Over half of Pompeii’s children were dead by the age of 10. And the telltale marks left by childhood infectious diseases are clearly visible on the teeth of many of the victims of the eruption.

But the good news was that if they survived into adolescence, ancient Pompeians could expect a life not much shorter than our own. For those who fell sick, the doctors would try out a diagnosis and cure – equipped with many of the same instruments, everything from tweezers to gynaecological specula, that you find in a modern medical surgery.

J

is for job seekers

Dozens of trades and professions are found at Pompeii: carpenters, actors, surveyors, gem-workers, architects, inn keepers, perfume-sellers, laundry men. There is even a “public pig keeper” by the name of Nigella. Occasionally there was big money to be made, but mostly these were low profit margin occupations, and many of those involved were ex-slaves or slaves still working to add to the fortunes of their masters.

If you didn’t have a job, what then? One of the paintings of Forum life shows a beggar (plus dog) taking hand-outs from a grand lady. Mostly, though, the poor did not exist. In a world without social care, those without means of support simply died.

K

is for kitchens

Even in the grandest houses, Pompeian kitchens could hardly have cooked up a banquet. They are mostly small, dark, and equipped with just a hearth and a place to boil a few pots.

But this impression may be misleading: plenty of elaborate kitchen utensils survive, from egg poachers and vast cauldrons to mousse-moulds and industrial-scale sieves.

For those occasional banquets, we must imagine preparations extending well beyond the kitchen. One ancient novel talks about a slave shelling peas on the front step, while doubling as hall porter.

Large joints of meat would have sizzled away on portable braziers, perhaps in front of the guests.

L

is for lavatories

The usual place for a Pompeian lavatory was in the kitchen. Hygiene aside, it presumably functioned as a convenient waste-disposal unit, in addition to its more familiar function.

A few had shafts that dropped down into a running water supply, though the truth is that rich Pompeians were more interested in using piped water to run ornamental fountains than to make their ablutions more efficient. Many went directly into cesspits, and the remains still lingering in them today are a favourite target of archaeologists wanting to find out what really went in and out of Pompeian stomachs.

M

is for mains drains

Why are there so many stepping stones in Pompeii’s streets? The answer is simple. There were hardly any public drains to take rainwater and sewage out of the city.

Most water, and a lot else, no doubt, flowed out through the streets, which must have become rather unsavoury rivers in a downpour. There were no such features at the nearby town of Herculaneum, where there was a developed system of underground drainage.

N

is for nightlife

When the night fell in Pompeii, it was very dark indeed. The thousands of oil lamps discovered can hardly have made much impact on the gloom. All the same, the bars kept on serving. Some hung welcoming lamps over their front doors. One striking example is in the shape of a pygmy with an enormous phallus, lights dangling from every extremity.

And a group of mates signing themselves ‘the late drinkers’ left their message on a Pompeian wall. Sign writers too were busy in the dark. A man called Celer posted up an advertisement for a gladiator show, “written,” it says, “by the light of the moon”. Add to this the noise of all the guard dogs barking, the horses bellowing and the odd wakeful, honking pig: it was probably noisy as well as dark after hours in Pompeii.

O

is for one-way streets

How did two carts pass in a Pompeian street? A few of the major thoroughfares were wide enough for two-way traffic, but the vast majority were definitely single track. Reversing would be next to impossible with a horse-drawn cart, never mind all the stepping stones in the way.

One solution was to ring a loud warning bell, or send a boy ahead to make sure the way was clear. But, by studying the wheel ruts and the scrapes made by wheels hitting the curbs as they rounded corners, some archaeologists now think that a one-way street system was in operation, which would have prevented collisions.

P

is for plonk

One of the best-known products of the land surrounding Pompeii was wine. The excellent Roman premier cru, Falernian, came from nearby. And one amphora of Pompeian wine was prized enough by someone that it found its way to England, probably as a gift or a souvenir, rather than evidence for a flourishing wine trade with the northern provinces.

But much of the really local wine was bottom of the range. One Roman writer complained that it gave you a hangover till midday.

Q

is for quality of life

Life was comfortable for the wealthy, living in large – albeit often rather dark – houses, with gardens and shady colonnades. One house in the centre of the town was as big as some of the palaces occupied by the kings of the ancient world, and a few spectacular multi-storey properties on the western side of the town enjoyed marvellous views over the Mediterranean.

For the slaves and the poor, however, things were bleak. They lived in cramped service quarters or in single rooms above their shop or workshop – with not much more space than a family would need to sleep. Hence, in part, the attraction of cafes and bars where there was room to stretch out.

R

is for real estate

Despite the occasional fortune made in the garum trade, land was the main source of wealth in Pompeii. Every owner of a grand house in Pompeii would have had a country property too, growing vines or olives, or grazing sheep. Not many of these properties have been found – unlike the town itself, it’s harder to know where to look for them.

But the country burial ground of one well-known Pompeian family has been discovered, next to what is presumed to be their country house. And a magnificent estate, which may have belonged to the family of Nero’s wife Poppaea, survives at Oplontis, a few miles from the town.

S

is for sex workers

The ancient brothel – a rather grim corner property, with five cubicles, a series of erotic paintings and a lavatory – is now one of the most visited sites in the town. Ironically, it is more frequented now than it was in the Roman world.

That said, hundreds of bits of graffiti from satisfied Roman customers survive on its walls, as well as a learned post-coital quotation from Virgil. But sex was almost certainly for sale in all kinds of other parts of town, in bars or seedy one-room lodgings. For the rich, sex was a service provided by slaves.

T

is for theatre-goers

Pompeii had two theatres and one amphitheatre. The amphitheatre (the earliest to survive anywhere in the world) featured occasional gladiator shows and wild beast hunts, with boars and goats rather than lions.

No less popular were the theatrical performances – plays, mimes and ancient pantomime, a combination of music and dance that is the ancestor of modern ballet, rather than our traditional Christmas entertainment. Fan clubs supported particular artistes, proclaiming their enthusiasm on the walls of the town: “Come back soon, Anicetus”.

U

is for upstairs, downstairs

What happened upstairs is another big Pompeian puzzle. Many houses had upper floors, but most were destroyed by the force of the eruption. The telltale surviving stairways, leading up from the ground floor, give away their presence even when all other trace has gone.

There are all kinds of guesses about how these quarters were used – perhaps storage, slave dormitories or rental apartments for lodgers.

V

is for voting

Pompeian men went to the polls each year to vote for four officials to take charge of town business: a senior pair called ‘the two men for delivering justice’, and a junior pair of aediles, officials who took care of markets, city property and streets.

Painted slogans indicate where support lay, for example “The bakers are supporting Caius Julius Polybius”. Negative campaigning (“Don’t vote for…”) was not the custom. But slogans like “The slackers say vote for Polybius” probably amounted to much the same.

W

is for writing on the wall

Pompeian walls, outside and sometimes inside, were covered with notices and graffiti. These included adverts for shows, electoral campaign posters, as well as personal messages of every sort: “Please, no shitting here”, “Successus the weaver’s in love with Iris and she doesn’t give a toss”, “A bronze jar has gone from this shop – reward for its return”.

How far the ability to read and write spread through Pompeian society is a matter of dispute. Some historians put it as low as 20 per cent of the adult males, but the sheer prevalence of writing and the simple everyday information conveyed by it (including price lists) suggests that it was considerably higher.

X

is for xenophobia

Pompeii was a surprisingly cosmopolitan town. With graffiti in Hebrew, ivories from the Far East, Egyptian statues, and traces of exotic spices, interaction with other nationalities clearly took place. That did not necessarily mean that the locals embraced foreign cultures with easy-going tolerance.

One favourite theme in painting was the imaginary life of pygmies on the Nile: these strange diminutive creatures were depicted getting up to all kinds of weird practices, from cannibalism to group sex.

Y

is for yob culture

Antisocial behaviour was a feature of ancient life as much as our own – not to mention binge-drinking and sports hooliganism.

The most infamous case of this occurred in AD 59, when a riot broke out in the amphitheatre between Pompeians and visitors from nearby Nuceria. In part this was a clash between home and away supporters. But Tacitus, the Roman historian who describes it, refers darkly to “illegal gangs”. The upshot was a complete ban on gladiatorial games in the town for ten years.

Z

is for Zanker and other books on Pompeii

I have just finished a book, Pompeii: The Life Of A Roman Town (Profile Books, September 2008), which focuses, as the title suggests, on its daily life.

I can also recommend Paul Zanker’s Pompeii: Public and Private Life (Harvard UP, 1998) for the development of the town and its architecture, and Alison E Cooley and MGL Cooley, Pompeii: A Sourcebook (Routledge, 2004). The latter, among other things, collects together and translates some of the most evocative of the Pompeian graffiti.

History Extra

Buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, and gradually disinterred from the middle of the 18th century, Pompeii is probably the world’s most famous archaeological site. But what was life like for the Romans who lived there, pre-eruption? Not that different from our own, as Mary Beard reveals in her A to Z of the ancient town, complete with yob culture, nightlife and plonk.

Buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, and gradually disinterred from the middle of the 18th century, Pompeii is probably the world’s most famous archaeological site. But what was life like for the Romans who lived there, pre-eruption? Not that different from our own, as Mary Beard reveals in her A to Z of the ancient town, complete with yob culture, nightlife and plonk.This article was first published in BBC History Magazine in 2008

A

is for artists at work

House makeovers? Style gurus? Des res? Painters and decorators did a roaring trade in Pompeii, transforming dark and often pokey interiors with a lavish coat of paint much as they do today. And we now have a precious glimpse of how the painters operated.

In one house, recently uncovered, a team of three or four decorators were interrupted by the eruption almost in mid-brush stroke, scarpering as the ash fell and abandoning their tools, 50 pots of paints, and a bucket of fresh plaster precariously balanced up a ladder. The assistants had been busy slapping on the plaster and the broad washes of colour, while the masters had drawn out the design in rough sketches and were painting the figures and the fiddly bits.

B

is for banking

The Romans didn’t have cheques or credit cards, but there were money lenders, the banks of the day. The most famous Pompeian banker is Lucius Caecilius Jucundus (now best known as the hero of the early parts of the Cambridge Latin Course).

Some of his records and receipts, stashed away in the attic of his house, give an idea of his business activities. Banker is actually a bit of a euphemism – he was mainly an auctioneer profiting on both sides of the transaction, charging the seller a commission and then lending money to the buyer at a healthy rate of interest.

C

is for cafe culture

The latest estimate reckons that there were about 200 cafes and bars in the town altogether – about one for every 60 residents. A counter usually ran along the street to catch the passing trade, selling cheap takeaway food from large jars.

Wine was stacked up behind it and there were tables in a back room for sit-down eating and drinking. It was the reverse of today’s society, where the rich eat out and the poor cook up at home. In Pompeii, the poor, living in tiny quarters with no facilities, relied on cafe food.

D

is for diet (and dormice)

Rich Pompeians did occasionally eat dormice. Or so a couple of strange pottery containers – identified, thanks to descriptions by ancient writers, as dormouse cages – suggest. But elaborate banquets were a rarity and just for the rich.

The staples were bread, olives, beans, eggs, cheese, fruit and veg (Pompeian cabbages were particularly prized), plus some tasty fish. Meat was less in evidence, and was mainly pork. This was a relatively healthy diet. In fact, the ancient Pompeians were on average slightly taller than modern Neapolitans.

E

is for education, education, education

One of the puzzles of Pompeii is where the kids went to school. No obvious school buildings or classrooms have been found. The likely answer is that teachers took their class of boys (and almost certainly only boys) to some convenient shady portico and did their teaching there.

A wonderful series of paintings of scenes of life in the Forum seems to show exactly that happening – with one poor miscreant being given a nasty beating in front of his classmates. And the curriculum? To judge from the large number of quotes from Virgil’s Aeneid scrawled on Pompeian walls, the young were well drilled in the national epic.

F

is for faith communities

The official religion of the town sponsored solemn sacrifices and raucous festivals celebrating Jupiter, Apollo, Venus and the Roman emperor, who was to all intents and purposes a god himself. But alongside this, happily co-existing so far as we can tell, were all kinds of other religions.

One of the most impressive sights at Pompeii is the little temple of the Egyptian goddess Isis, once tended by its white-clad, shaven-headed priests. We have evidence, too, for Jews and worshippers of Cybele, known as the Great Mother.

There is no clear sign of any Christians, but in one house an ivory statuette of the Indian goddess Lakshmi has turned up. Souvenir, curiosity or object of devotion? Nobody knows.

G

is for garum

No Roman cooking was complete without garum – a disgusting concoction of rotten fish. A more generous interpretation sees it as a version of the spicy fish sauces that are part of modern Thai cooking, and it was popular in Pompeii, which had at least one garum shop. One of its richest families made its fortune in the trade – and advertised the fact by decorating their front hall with a design of garum jars in mosaic. Garum traders were canny businessmen, with an eye on different markets. A kosher version (guaranteed to contain no shellfish) was produced for the local Jewish community.

H

is for hygiene

Pompeii boasted at least six public bathing complexes – some owned by the city council, some by private enterprise operations. Only a few of the very richest houses had their own facilities. The vast majority of the population would have exercised, scraped down, sweated and taken a dip in one of the communal establishments.

As you might imagine, they were hotbeds of germs and infection. The plunge pools had limited water circulation, no chlorination and must have been full of the usual sort of human effluent. Ancient doctors recommended not going to the baths with an open wound – it could lead to gangrene.

I

is for illness

Illness struck the young hard. Over half of Pompeii’s children were dead by the age of 10. And the telltale marks left by childhood infectious diseases are clearly visible on the teeth of many of the victims of the eruption.

But the good news was that if they survived into adolescence, ancient Pompeians could expect a life not much shorter than our own. For those who fell sick, the doctors would try out a diagnosis and cure – equipped with many of the same instruments, everything from tweezers to gynaecological specula, that you find in a modern medical surgery.

J

is for job seekers

Dozens of trades and professions are found at Pompeii: carpenters, actors, surveyors, gem-workers, architects, inn keepers, perfume-sellers, laundry men. There is even a “public pig keeper” by the name of Nigella. Occasionally there was big money to be made, but mostly these were low profit margin occupations, and many of those involved were ex-slaves or slaves still working to add to the fortunes of their masters.

If you didn’t have a job, what then? One of the paintings of Forum life shows a beggar (plus dog) taking hand-outs from a grand lady. Mostly, though, the poor did not exist. In a world without social care, those without means of support simply died.

K

is for kitchens

Even in the grandest houses, Pompeian kitchens could hardly have cooked up a banquet. They are mostly small, dark, and equipped with just a hearth and a place to boil a few pots.

But this impression may be misleading: plenty of elaborate kitchen utensils survive, from egg poachers and vast cauldrons to mousse-moulds and industrial-scale sieves.

For those occasional banquets, we must imagine preparations extending well beyond the kitchen. One ancient novel talks about a slave shelling peas on the front step, while doubling as hall porter.

Large joints of meat would have sizzled away on portable braziers, perhaps in front of the guests.

L

is for lavatories

The usual place for a Pompeian lavatory was in the kitchen. Hygiene aside, it presumably functioned as a convenient waste-disposal unit, in addition to its more familiar function.

A few had shafts that dropped down into a running water supply, though the truth is that rich Pompeians were more interested in using piped water to run ornamental fountains than to make their ablutions more efficient. Many went directly into cesspits, and the remains still lingering in them today are a favourite target of archaeologists wanting to find out what really went in and out of Pompeian stomachs.

M

is for mains drains

Why are there so many stepping stones in Pompeii’s streets? The answer is simple. There were hardly any public drains to take rainwater and sewage out of the city.

Most water, and a lot else, no doubt, flowed out through the streets, which must have become rather unsavoury rivers in a downpour. There were no such features at the nearby town of Herculaneum, where there was a developed system of underground drainage.

N

is for nightlife

When the night fell in Pompeii, it was very dark indeed. The thousands of oil lamps discovered can hardly have made much impact on the gloom. All the same, the bars kept on serving. Some hung welcoming lamps over their front doors. One striking example is in the shape of a pygmy with an enormous phallus, lights dangling from every extremity.

And a group of mates signing themselves ‘the late drinkers’ left their message on a Pompeian wall. Sign writers too were busy in the dark. A man called Celer posted up an advertisement for a gladiator show, “written,” it says, “by the light of the moon”. Add to this the noise of all the guard dogs barking, the horses bellowing and the odd wakeful, honking pig: it was probably noisy as well as dark after hours in Pompeii.

O

is for one-way streets

How did two carts pass in a Pompeian street? A few of the major thoroughfares were wide enough for two-way traffic, but the vast majority were definitely single track. Reversing would be next to impossible with a horse-drawn cart, never mind all the stepping stones in the way.

One solution was to ring a loud warning bell, or send a boy ahead to make sure the way was clear. But, by studying the wheel ruts and the scrapes made by wheels hitting the curbs as they rounded corners, some archaeologists now think that a one-way street system was in operation, which would have prevented collisions.

P

is for plonk

One of the best-known products of the land surrounding Pompeii was wine. The excellent Roman premier cru, Falernian, came from nearby. And one amphora of Pompeian wine was prized enough by someone that it found its way to England, probably as a gift or a souvenir, rather than evidence for a flourishing wine trade with the northern provinces.

But much of the really local wine was bottom of the range. One Roman writer complained that it gave you a hangover till midday.

Q

is for quality of life

Life was comfortable for the wealthy, living in large – albeit often rather dark – houses, with gardens and shady colonnades. One house in the centre of the town was as big as some of the palaces occupied by the kings of the ancient world, and a few spectacular multi-storey properties on the western side of the town enjoyed marvellous views over the Mediterranean.

For the slaves and the poor, however, things were bleak. They lived in cramped service quarters or in single rooms above their shop or workshop – with not much more space than a family would need to sleep. Hence, in part, the attraction of cafes and bars where there was room to stretch out.

R

is for real estate

Despite the occasional fortune made in the garum trade, land was the main source of wealth in Pompeii. Every owner of a grand house in Pompeii would have had a country property too, growing vines or olives, or grazing sheep. Not many of these properties have been found – unlike the town itself, it’s harder to know where to look for them.

But the country burial ground of one well-known Pompeian family has been discovered, next to what is presumed to be their country house. And a magnificent estate, which may have belonged to the family of Nero’s wife Poppaea, survives at Oplontis, a few miles from the town.

S

is for sex workers

The ancient brothel – a rather grim corner property, with five cubicles, a series of erotic paintings and a lavatory – is now one of the most visited sites in the town. Ironically, it is more frequented now than it was in the Roman world.

That said, hundreds of bits of graffiti from satisfied Roman customers survive on its walls, as well as a learned post-coital quotation from Virgil. But sex was almost certainly for sale in all kinds of other parts of town, in bars or seedy one-room lodgings. For the rich, sex was a service provided by slaves.

T

is for theatre-goers

Pompeii had two theatres and one amphitheatre. The amphitheatre (the earliest to survive anywhere in the world) featured occasional gladiator shows and wild beast hunts, with boars and goats rather than lions.

No less popular were the theatrical performances – plays, mimes and ancient pantomime, a combination of music and dance that is the ancestor of modern ballet, rather than our traditional Christmas entertainment. Fan clubs supported particular artistes, proclaiming their enthusiasm on the walls of the town: “Come back soon, Anicetus”.

U

is for upstairs, downstairs

What happened upstairs is another big Pompeian puzzle. Many houses had upper floors, but most were destroyed by the force of the eruption. The telltale surviving stairways, leading up from the ground floor, give away their presence even when all other trace has gone.

There are all kinds of guesses about how these quarters were used – perhaps storage, slave dormitories or rental apartments for lodgers.

V

is for voting

Pompeian men went to the polls each year to vote for four officials to take charge of town business: a senior pair called ‘the two men for delivering justice’, and a junior pair of aediles, officials who took care of markets, city property and streets.

Painted slogans indicate where support lay, for example “The bakers are supporting Caius Julius Polybius”. Negative campaigning (“Don’t vote for…”) was not the custom. But slogans like “The slackers say vote for Polybius” probably amounted to much the same.

W

is for writing on the wall

Pompeian walls, outside and sometimes inside, were covered with notices and graffiti. These included adverts for shows, electoral campaign posters, as well as personal messages of every sort: “Please, no shitting here”, “Successus the weaver’s in love with Iris and she doesn’t give a toss”, “A bronze jar has gone from this shop – reward for its return”.

How far the ability to read and write spread through Pompeian society is a matter of dispute. Some historians put it as low as 20 per cent of the adult males, but the sheer prevalence of writing and the simple everyday information conveyed by it (including price lists) suggests that it was considerably higher.

X

is for xenophobia

Pompeii was a surprisingly cosmopolitan town. With graffiti in Hebrew, ivories from the Far East, Egyptian statues, and traces of exotic spices, interaction with other nationalities clearly took place. That did not necessarily mean that the locals embraced foreign cultures with easy-going tolerance.

One favourite theme in painting was the imaginary life of pygmies on the Nile: these strange diminutive creatures were depicted getting up to all kinds of weird practices, from cannibalism to group sex.

Y

is for yob culture

Antisocial behaviour was a feature of ancient life as much as our own – not to mention binge-drinking and sports hooliganism.

The most infamous case of this occurred in AD 59, when a riot broke out in the amphitheatre between Pompeians and visitors from nearby Nuceria. In part this was a clash between home and away supporters. But Tacitus, the Roman historian who describes it, refers darkly to “illegal gangs”. The upshot was a complete ban on gladiatorial games in the town for ten years.

Z

is for Zanker and other books on Pompeii

I have just finished a book, Pompeii: The Life Of A Roman Town (Profile Books, September 2008), which focuses, as the title suggests, on its daily life.

I can also recommend Paul Zanker’s Pompeii: Public and Private Life (Harvard UP, 1998) for the development of the town and its architecture, and Alison E Cooley and MGL Cooley, Pompeii: A Sourcebook (Routledge, 2004). The latter, among other things, collects together and translates some of the most evocative of the Pompeian graffiti.

Published on March 19, 2015 08:21

History Trivia - Catholic Church calls a crusade against Cathar heretics in Toulouse

March 19

235 Maximinus Thrax was proclaimed Emperor of Rome.

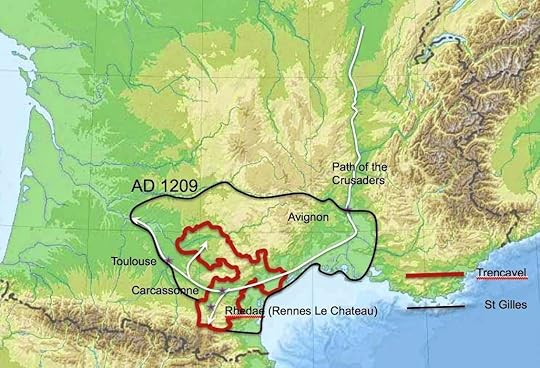

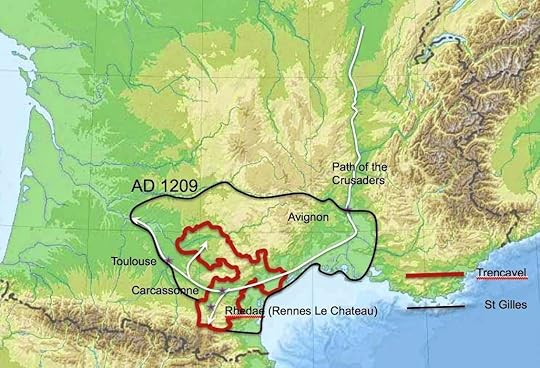

1179 The Third Lateran Council of the Catholic Church called a crusade against Cathar heretics in Toulouse.

1307 The Douglas Larder raid - Sir James Douglas was a Scot who returned home from school in Paris to find his estates had been claimed and occupied by an Englishman, Robert de Clifford. Joining with Robert the Bruce for a time, he returned in an attempt to take back his land, attacking his own castle three times. After his final assault, known as the Douglas Larder, he razed the castle to the ground.

235 Maximinus Thrax was proclaimed Emperor of Rome.

1179 The Third Lateran Council of the Catholic Church called a crusade against Cathar heretics in Toulouse.

1307 The Douglas Larder raid - Sir James Douglas was a Scot who returned home from school in Paris to find his estates had been claimed and occupied by an Englishman, Robert de Clifford. Joining with Robert the Bruce for a time, he returned in an attempt to take back his land, attacking his own castle three times. After his final assault, known as the Douglas Larder, he razed the castle to the ground.

Published on March 19, 2015 02:00