MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 189

March 17, 2015

Spain finds Don Quixote writer Cervantes' tomb in Madrid

Camila Ruz

BBC News

Forensic scientists say they have found the tomb of Spain's much-loved giant of literature, Miguel de Cervantes, nearly 400 years after his death.

Forensic scientists say they have found the tomb of Spain's much-loved giant of literature, Miguel de Cervantes, nearly 400 years after his death.

They believe they have found the bones of Cervantes, his wife and others recorded as buried with him in Madrid's Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians.

Separating and identifying his badly damaged bones from the other fragments will be difficult, researchers say.

The Don Quixote author was buried in 1616 but his coffin was later lost.

When the convent was rebuilt in 1673, his remains were moved into the new building and it has taken centuries to rediscover the tomb of the man known as Spain's "Prince of Letters".

"His end was that of a poor man. A war veteran with his battle wounds," said Pedro Corral, head of art, sport and tourism at Madrid city council.

Miguel de Cervantes - Father of modern novel

1547: Born near Madrid 1571: Shot and wounded at Battle of Lepanto1575: Captured and enslaved for five years in Algiers1605: Publishes first part of The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, second part in 1615. Don Quixote is man obsessed with chivalry who sets out in search of adventure on his ageing horse Rocinante and with his faithful squire Sancho Panza 1616: Cervantes dies aged 68, with six teeth remaining. Buried at Convent of Barefoot TrinitariansGrave lost when convent rebuilt

The team of 30 researchers used infrared cameras, 3D scanners and ground-penetrating radar to pinpoint the burial site, in a forgotten crypt beneath the building.

Inside one of 33 niches found against the far wall, archaeologists discovered a number of adult bones matching a group of people with whom Cervantes had been buried, before their tombs were disturbed and moved into the crypt.

"The remains are in a bad state of conservation and do not allow us to do an individual identification of Miguel de Cervantes," said forensic scientist Almudena Garcia Rubio.

"But we are sure what the historical sources say is the burial of Miguel de Cervantes and the other people buried with him is what we have found."

Although the initials M.C were found on the coffin lid, they were not thought to refer to Cervantes himself

Although the initials M.C were found on the coffin lid, they were not thought to refer to Cervantes himself

Further analysis may allow the team to separate the bones of Cervantes from those of the others if they can use DNA analysis to work out which bones do not belong to the author.

Investigator Luis Avial told a news conference on Tuesday that Cervantes would be reburied "with full honours" in the same convent after a new tomb had been built, according to his wishes.

"Cervantes asked to be buried there and there he should stay," said Luis Avial, georadar expert on the search team.

The convent's religious order helped pay for his ransom after he was captured by pirates and held prisoner for five years in Algiers.

'Rediscovering Cervantes'

The crypt will be opened to the public next year for the first time in centuries to coincide with the 400th anniversary of Cervantes' death.

Mr Corral told the BBC that the project had not just been about finding the bones of the author but of honouring his memory and encouraging people to learn more about him.

Many people may be rediscovering Cervantes because of the search, he said.

Born near Madrid in 1547, Cervantes has been dubbed the father of the modern novel for The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, published in two parts in 1605 and 1615.

The book is thought to be one of the most widely read and translated books in the world.

A plaque on the convent wall commemorates Cervantes' rescue from captivity

A plaque on the convent wall commemorates Cervantes' rescue from captivity

BBC News

Forensic scientists say they have found the tomb of Spain's much-loved giant of literature, Miguel de Cervantes, nearly 400 years after his death.

Forensic scientists say they have found the tomb of Spain's much-loved giant of literature, Miguel de Cervantes, nearly 400 years after his death.They believe they have found the bones of Cervantes, his wife and others recorded as buried with him in Madrid's Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians.

Separating and identifying his badly damaged bones from the other fragments will be difficult, researchers say.

The Don Quixote author was buried in 1616 but his coffin was later lost.

When the convent was rebuilt in 1673, his remains were moved into the new building and it has taken centuries to rediscover the tomb of the man known as Spain's "Prince of Letters".

"His end was that of a poor man. A war veteran with his battle wounds," said Pedro Corral, head of art, sport and tourism at Madrid city council.

Miguel de Cervantes - Father of modern novel

1547: Born near Madrid 1571: Shot and wounded at Battle of Lepanto1575: Captured and enslaved for five years in Algiers1605: Publishes first part of The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, second part in 1615. Don Quixote is man obsessed with chivalry who sets out in search of adventure on his ageing horse Rocinante and with his faithful squire Sancho Panza 1616: Cervantes dies aged 68, with six teeth remaining. Buried at Convent of Barefoot TrinitariansGrave lost when convent rebuilt

The team of 30 researchers used infrared cameras, 3D scanners and ground-penetrating radar to pinpoint the burial site, in a forgotten crypt beneath the building.

Inside one of 33 niches found against the far wall, archaeologists discovered a number of adult bones matching a group of people with whom Cervantes had been buried, before their tombs were disturbed and moved into the crypt.

"The remains are in a bad state of conservation and do not allow us to do an individual identification of Miguel de Cervantes," said forensic scientist Almudena Garcia Rubio.

"But we are sure what the historical sources say is the burial of Miguel de Cervantes and the other people buried with him is what we have found."

Although the initials M.C were found on the coffin lid, they were not thought to refer to Cervantes himself

Although the initials M.C were found on the coffin lid, they were not thought to refer to Cervantes himself Further analysis may allow the team to separate the bones of Cervantes from those of the others if they can use DNA analysis to work out which bones do not belong to the author.

Investigator Luis Avial told a news conference on Tuesday that Cervantes would be reburied "with full honours" in the same convent after a new tomb had been built, according to his wishes.

"Cervantes asked to be buried there and there he should stay," said Luis Avial, georadar expert on the search team.

The convent's religious order helped pay for his ransom after he was captured by pirates and held prisoner for five years in Algiers.

'Rediscovering Cervantes'

The crypt will be opened to the public next year for the first time in centuries to coincide with the 400th anniversary of Cervantes' death.

Mr Corral told the BBC that the project had not just been about finding the bones of the author but of honouring his memory and encouraging people to learn more about him.

Many people may be rediscovering Cervantes because of the search, he said.

Born near Madrid in 1547, Cervantes has been dubbed the father of the modern novel for The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, published in two parts in 1605 and 1615.

The book is thought to be one of the most widely read and translated books in the world.

A plaque on the convent wall commemorates Cervantes' rescue from captivity

A plaque on the convent wall commemorates Cervantes' rescue from captivity

Published on March 17, 2015 05:37

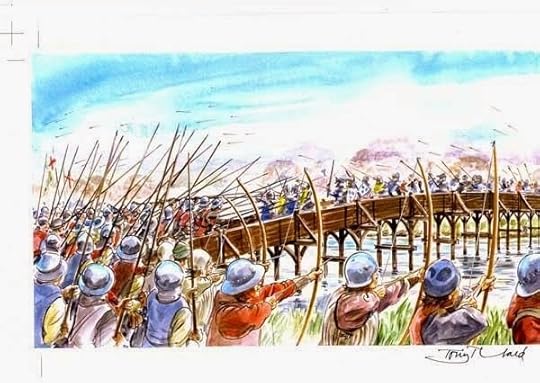

History Trivia - Battle of Munda Julius Caesar defeats Pompeian forces

March 17

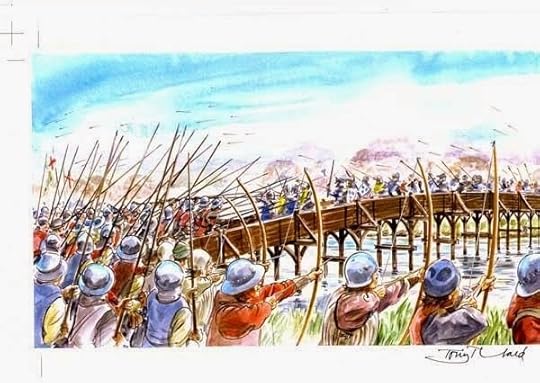

45 BC In his last victory, Julius Caesar defeated the Pompeian forces of Titus Labienus and Pompey the Younger in the Battle of Munda.

44 BC, the conspirators in Julius Caesar's murder were granted amnesty in a short-lived reprieve before Mark Antony stirred the people to take revenge on them.

180 AD, Marcus Aurelius died in his camp-bed during a campaign along the Danube frontier, and Commodus became the sole emperor of the Roman Empire

45 BC In his last victory, Julius Caesar defeated the Pompeian forces of Titus Labienus and Pompey the Younger in the Battle of Munda.

44 BC, the conspirators in Julius Caesar's murder were granted amnesty in a short-lived reprieve before Mark Antony stirred the people to take revenge on them.

180 AD, Marcus Aurelius died in his camp-bed during a campaign along the Danube frontier, and Commodus became the sole emperor of the Roman Empire

Published on March 17, 2015 02:00

March 16, 2015

Audio Book Launch - Sasha by K. Meador

Written by: K. Meador Narrated by: Michaela James Length: 4 mins Unabridged Audiobook

When Sasha's little sister keeps taking her things, Sasha learns a valuable lesson.

Audible

Published on March 16, 2015 16:57

10 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Romans

Harry Sidebottom History Extra

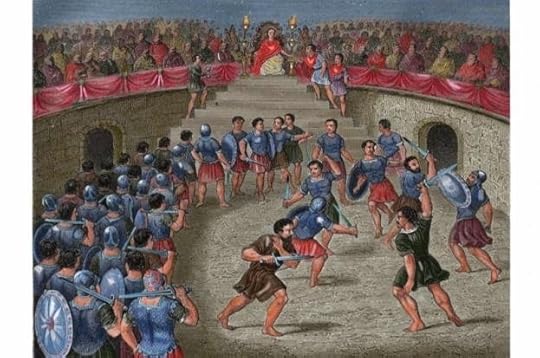

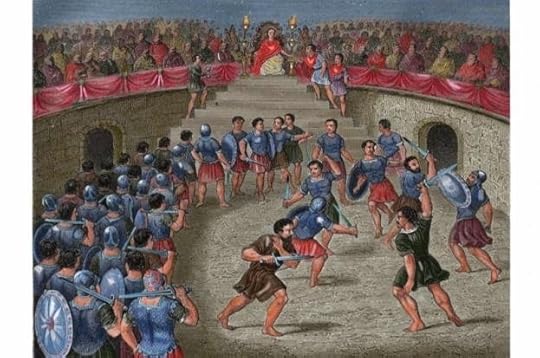

19th-century coloured engraving of gladiators in ancient Rome. © Lanmas / Alamy

19th-century coloured engraving of gladiators in ancient Rome. © Lanmas / Alamy

1) Gladiatorial fighting was not the most popular entertainmentThe seating capacity of the main venues formed a ‘rough and ready’ index of the popularity of the different public shows in Rome. The arena for gladiatorial combat, the Colosseum – known in antiquity as the Flavian Amphitheatre – was huge. Modern archaeologists estimate that it could accommodate 50,000 people. One ancient source put the number even higher, at 87,000.

Yet it was dwarfed by the Circus Maximus, where some 250,000 could watch chariot racing. Despite the popularity of pantomime (closer to our ballet than modern panto), theatrical shows came off a poor third. The largest theatre in Rome, that of Marcellus, could hold a mere 20,500.

2) Roman warships were not rowed by slavesIn almost all ‘swords and sandals’ movies and novels, when a galley [a large ship propelled primarily by rowing] appears, we hear the clank of slaves’ chains and the crack of the overseer’s whip. Both are completely anachronistic: the Romans, like the Greeks, had an ideology that we call ‘civic militarism’. It was believed that if you were a citizen you had a duty to fight for your state, and conversely if you fought you were entitled to political rights.

This excluded the use of slave rowers, or slave soldiers like those of medieval Islam. In the handful of exceptional times when slaves were admitted to the armed forces, they were either freed before enlistment, or promised manumission if they performed well in battle.

3) They did not all die youngThe average life expectancy – although all such figures are uncertain – was only about 25. However, this did not mean that no one lived into their thirties or on into old age. The average was skewed by the number of women who died giving birth, and by high infant mortality. If a Roman made it to maturity, they were likely to live as long as people in the modern western world.

4) Very few Roman hours lasted an hourLike us, the Romans divided the day into 24 hours. But unlike us, their hours varied in length. For the Romans there were always 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of darkness. Thus, for example, a daylight hour in high summer was considerably longer than one in midwinter.

5) Not all Romans spoke LatinStretching from the Atlantic to the Tigris, the Roman empire contained perhaps about 65 million inhabitants. While Latin was the language of the army and of Roman law, many peoples incorporated into the empire continued to speak their native tongue, either as well as, or, especially in the countryside, instead of Latin. Thus variants of Celtic and Syriac, and more obscure languages such as Cappadocian and Thracian, survived.

The Roman elite was bilingual. For them, knowledge of Greek was a badge of status – as such it was similar to French for aristocrats across Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. So internalised was the Roman usage, when the senators assassinated Julius Caesar, some shouted out not in Latin, but Greek.

6) Many Romans disliked philosophyThe empire produced eminent philosophers such as Seneca and Marcus Aurelius. Yet some Romans were hostile to philosophy for two main reasons: first, it was a Greek invention, and the Greeks were a conquered race – Roman attitudes to the Greeks were very mixed. Second, the study of philosophy, with its hair-splitting definitions and its concentration on the inner man, could be considered to unfit a man for an active life that would serve the state.

The latter view had long been held by some Greeks. Galen, the doctor to the imperial court, remarked that the Romans regarded philosophy as being of no more use than drilling holes in millet seeds.

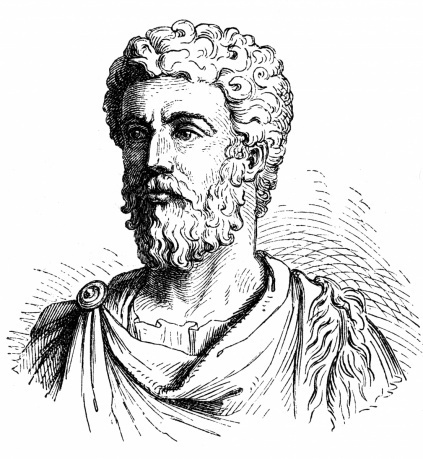

19th-century wood engraving of Roman Emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius. © INTERFOTO / Alamy

7) There were sexual ‘do’s’ and ‘don’t’sThe great French scholar Paul Veyne said that the Romans were paralysed by sexual inhibitions. While that might be going too far, there were strict limits to socially acceptable behaviour: after the wedding night, for example, a modest Roman wife should not let her husband see her naked again. Consequently, it might be no surprise that those philosophers who argued that a man should not have sex with anyone but his wife, not even with his slaves, won few converts.

8) Generals seldom fought in combatAlthough in art they liked to be depicted in heroic and martial posture, Roman generals were ‘battle managers’, not warriors. Only in the most exceptional circumstances were they expected to fight hand-to-hand. If a battle was lost, the commander should draw his sword and either turn it on himself, or seek an honourable death at the hands of the enemy. Not until Maximinus Thrax (who reigned from AD235 to 238) was an emperor recorded as fighting in the line of battle.

9) Emperors poisoned themselves every dayFrom the end of the first century AD, Roman emperors had adopted the daily habit of taking a small amount of every known poison in an attempt to gain immunity. The mixture was known as the Mithridatium, after the originator of the practice, Mithridates the Great, king of Pontus (who reigned from c120 to 65BC).

A drinking vessel made from the horn of the one-horned horses or donkeys, believed by the Romans to have lived in India, was thought to be an antidote to fatal poisons.

10) Romans believed they had good reasons to persecute ChristiansThe Romans believed their empire rested on the Pax Deorum: if the Romans did right by the pagan gods, those deities would do right by them. Christians, on the other hand, either claimed the pagan gods were evil demons, or denied they existed at all. If the Romans allowed such atheists to propagate their beliefs, it was little wonder that the gods were angered and withheld their favour from Rome.

Usually, Roman persecutors gave Christians every chance to acknowledge the traditional gods, and thus avoid martyrdom. Of course, a committed Christian could not offer such false idols even a pinch of incense, or say the necessary ritual words.

Harry Sidebottom is a lecturer in ancient history at Lincoln College, Oxford, and author of the Warrior of Rome and Throne of the Caesars series of novels.

Our Ancient Rome Week, which runs from Monday 16 March, celebrates the March 2015 issue of BBC History Magazine, which includes a feature on the sights and sounds of Britannia at the time when Hadrian's Wall was being completed. To keep up with the latest content, click here.

19th-century coloured engraving of gladiators in ancient Rome. © Lanmas / Alamy

19th-century coloured engraving of gladiators in ancient Rome. © Lanmas / Alamy 1) Gladiatorial fighting was not the most popular entertainmentThe seating capacity of the main venues formed a ‘rough and ready’ index of the popularity of the different public shows in Rome. The arena for gladiatorial combat, the Colosseum – known in antiquity as the Flavian Amphitheatre – was huge. Modern archaeologists estimate that it could accommodate 50,000 people. One ancient source put the number even higher, at 87,000.

Yet it was dwarfed by the Circus Maximus, where some 250,000 could watch chariot racing. Despite the popularity of pantomime (closer to our ballet than modern panto), theatrical shows came off a poor third. The largest theatre in Rome, that of Marcellus, could hold a mere 20,500.

2) Roman warships were not rowed by slavesIn almost all ‘swords and sandals’ movies and novels, when a galley [a large ship propelled primarily by rowing] appears, we hear the clank of slaves’ chains and the crack of the overseer’s whip. Both are completely anachronistic: the Romans, like the Greeks, had an ideology that we call ‘civic militarism’. It was believed that if you were a citizen you had a duty to fight for your state, and conversely if you fought you were entitled to political rights.

This excluded the use of slave rowers, or slave soldiers like those of medieval Islam. In the handful of exceptional times when slaves were admitted to the armed forces, they were either freed before enlistment, or promised manumission if they performed well in battle.

3) They did not all die youngThe average life expectancy – although all such figures are uncertain – was only about 25. However, this did not mean that no one lived into their thirties or on into old age. The average was skewed by the number of women who died giving birth, and by high infant mortality. If a Roman made it to maturity, they were likely to live as long as people in the modern western world.

4) Very few Roman hours lasted an hourLike us, the Romans divided the day into 24 hours. But unlike us, their hours varied in length. For the Romans there were always 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of darkness. Thus, for example, a daylight hour in high summer was considerably longer than one in midwinter.

5) Not all Romans spoke LatinStretching from the Atlantic to the Tigris, the Roman empire contained perhaps about 65 million inhabitants. While Latin was the language of the army and of Roman law, many peoples incorporated into the empire continued to speak their native tongue, either as well as, or, especially in the countryside, instead of Latin. Thus variants of Celtic and Syriac, and more obscure languages such as Cappadocian and Thracian, survived.

The Roman elite was bilingual. For them, knowledge of Greek was a badge of status – as such it was similar to French for aristocrats across Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. So internalised was the Roman usage, when the senators assassinated Julius Caesar, some shouted out not in Latin, but Greek.

6) Many Romans disliked philosophyThe empire produced eminent philosophers such as Seneca and Marcus Aurelius. Yet some Romans were hostile to philosophy for two main reasons: first, it was a Greek invention, and the Greeks were a conquered race – Roman attitudes to the Greeks were very mixed. Second, the study of philosophy, with its hair-splitting definitions and its concentration on the inner man, could be considered to unfit a man for an active life that would serve the state.

The latter view had long been held by some Greeks. Galen, the doctor to the imperial court, remarked that the Romans regarded philosophy as being of no more use than drilling holes in millet seeds.

19th-century wood engraving of Roman Emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius. © INTERFOTO / Alamy

7) There were sexual ‘do’s’ and ‘don’t’sThe great French scholar Paul Veyne said that the Romans were paralysed by sexual inhibitions. While that might be going too far, there were strict limits to socially acceptable behaviour: after the wedding night, for example, a modest Roman wife should not let her husband see her naked again. Consequently, it might be no surprise that those philosophers who argued that a man should not have sex with anyone but his wife, not even with his slaves, won few converts.

8) Generals seldom fought in combatAlthough in art they liked to be depicted in heroic and martial posture, Roman generals were ‘battle managers’, not warriors. Only in the most exceptional circumstances were they expected to fight hand-to-hand. If a battle was lost, the commander should draw his sword and either turn it on himself, or seek an honourable death at the hands of the enemy. Not until Maximinus Thrax (who reigned from AD235 to 238) was an emperor recorded as fighting in the line of battle.

9) Emperors poisoned themselves every dayFrom the end of the first century AD, Roman emperors had adopted the daily habit of taking a small amount of every known poison in an attempt to gain immunity. The mixture was known as the Mithridatium, after the originator of the practice, Mithridates the Great, king of Pontus (who reigned from c120 to 65BC).

A drinking vessel made from the horn of the one-horned horses or donkeys, believed by the Romans to have lived in India, was thought to be an antidote to fatal poisons.

10) Romans believed they had good reasons to persecute ChristiansThe Romans believed their empire rested on the Pax Deorum: if the Romans did right by the pagan gods, those deities would do right by them. Christians, on the other hand, either claimed the pagan gods were evil demons, or denied they existed at all. If the Romans allowed such atheists to propagate their beliefs, it was little wonder that the gods were angered and withheld their favour from Rome.

Usually, Roman persecutors gave Christians every chance to acknowledge the traditional gods, and thus avoid martyrdom. Of course, a committed Christian could not offer such false idols even a pinch of incense, or say the necessary ritual words.

Harry Sidebottom is a lecturer in ancient history at Lincoln College, Oxford, and author of the Warrior of Rome and Throne of the Caesars series of novels.

Our Ancient Rome Week, which runs from Monday 16 March, celebrates the March 2015 issue of BBC History Magazine, which includes a feature on the sights and sounds of Britannia at the time when Hadrian's Wall was being completed. To keep up with the latest content, click here.

Published on March 16, 2015 05:32

History Trivia - Battle of Boroughbridge

March 16

37 Emperor Tiberius died at the age of 78 and was succeeded by Caligula.

1072 Adalbert, archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen and guardian and tutor to Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, died.

1322 The Battle of Boroughbridge took place in the First War of Scottish Independence.

37 Emperor Tiberius died at the age of 78 and was succeeded by Caligula.

1072 Adalbert, archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen and guardian and tutor to Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, died.

1322 The Battle of Boroughbridge took place in the First War of Scottish Independence.

Published on March 16, 2015 02:00

March 15, 2015

World's Oldest Pretzel Found in Germany

Rossella Lorenzi Discovery News

German archaeologists announced this week they have discovered what could be the world’s oldest pretzel.

German archaeologists announced this week they have discovered what could be the world’s oldest pretzel.

Unearthed during a large excavation on the “Donaumarkt” in Regensburg, an area nearby the Danube which was destroyed in the 1950-60s, the charred pretzel fragments are believed to be 250 years old. They were recovered beneath a floor in a structure long known to be a bakery.

“We found the remains of two pretzels, a piece of bread shaped like a croissant and three small bread rolls,” Silvia Codreanu-Windauer, of the Bavarian State Department of Monuments and Sites, told Discovery News.

Photos: Archaeologists Find 250-Year-Old Pretzel

All the baked goods were totally carbonized, which is why they have been preserved for so long.

“We suppose the baker forgot the pieces in the oven and afterwards he threw them away in a hole under the floor,” Codreanu-Windauer said.

Carbon dating showed the pastries were made between 1700 and 1800. Indeed, the archaeologists found written evidence that in 1753 a baker named Johann Georg Held was living at the site.

“As far I know these are the world’s oldest pretzels, although we know from 12th century miniature pictures and from a pretzel shaped fibula that these dough products were baked since the early Middle Age,” Codreanu-Windauer said.

Ancient Greeks Used Portable Grills at Their Picnics

It is believed pretzels were invented sometime between the 5th and 6th centuries by monks who twisted leftover strips of dough to look like arms crossed in prayer.

Even though they are 250 years old, the pretzel fragments are similar to today’s product.

“They look the same. The fragments are just a little bit smaller because of the carbonizing process,” Codreanu-Windauer said.

The baked goods represent the first archaeological proof of a typical Bavarian bakery assortment.

Cheese Chunks Adorn Ancient Mummies

“It is lucky for archaeologist to find such organic pieces. You know, we always find tons of ceramics, glass, metalworks or bones, but such glimpses of everyday life are extremely rare,” Codreanu-Windauer said.

Image: The remains of the 250-year-old pretzel fragment found in Germany. Credit: Thomas Stöckl/Bavarian State Department of Monument and Sites.

German archaeologists announced this week they have discovered what could be the world’s oldest pretzel.

German archaeologists announced this week they have discovered what could be the world’s oldest pretzel.Unearthed during a large excavation on the “Donaumarkt” in Regensburg, an area nearby the Danube which was destroyed in the 1950-60s, the charred pretzel fragments are believed to be 250 years old. They were recovered beneath a floor in a structure long known to be a bakery.

“We found the remains of two pretzels, a piece of bread shaped like a croissant and three small bread rolls,” Silvia Codreanu-Windauer, of the Bavarian State Department of Monuments and Sites, told Discovery News.

Photos: Archaeologists Find 250-Year-Old Pretzel

All the baked goods were totally carbonized, which is why they have been preserved for so long.

“We suppose the baker forgot the pieces in the oven and afterwards he threw them away in a hole under the floor,” Codreanu-Windauer said.

Carbon dating showed the pastries were made between 1700 and 1800. Indeed, the archaeologists found written evidence that in 1753 a baker named Johann Georg Held was living at the site.

“As far I know these are the world’s oldest pretzels, although we know from 12th century miniature pictures and from a pretzel shaped fibula that these dough products were baked since the early Middle Age,” Codreanu-Windauer said.

Ancient Greeks Used Portable Grills at Their Picnics

It is believed pretzels were invented sometime between the 5th and 6th centuries by monks who twisted leftover strips of dough to look like arms crossed in prayer.

Even though they are 250 years old, the pretzel fragments are similar to today’s product.

“They look the same. The fragments are just a little bit smaller because of the carbonizing process,” Codreanu-Windauer said.

The baked goods represent the first archaeological proof of a typical Bavarian bakery assortment.

Cheese Chunks Adorn Ancient Mummies

“It is lucky for archaeologist to find such organic pieces. You know, we always find tons of ceramics, glass, metalworks or bones, but such glimpses of everyday life are extremely rare,” Codreanu-Windauer said.

Image: The remains of the 250-year-old pretzel fragment found in Germany. Credit: Thomas Stöckl/Bavarian State Department of Monument and Sites.

Published on March 15, 2015 06:40

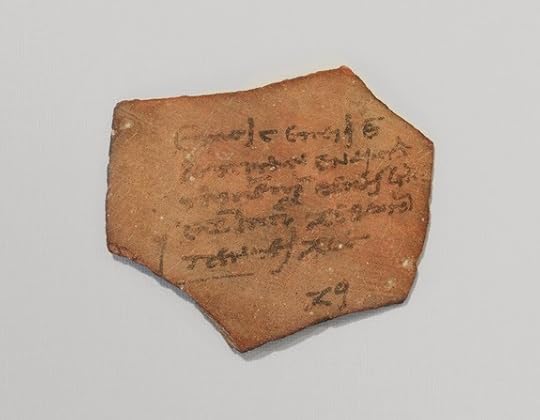

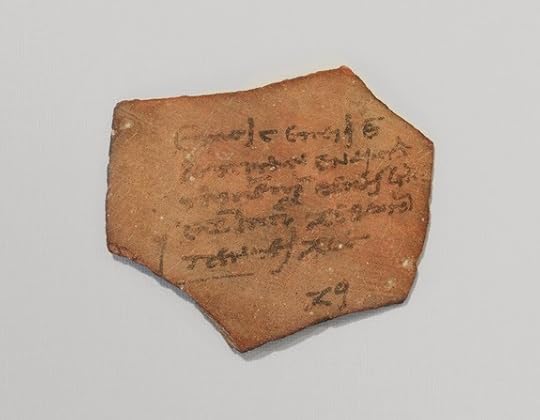

Ancient Receipt Proves Egyptian Taxes Were Worse Than Yours

Owen Jarus

Live Science

Several ancient and medieval texts at McGill University Library and Archives are in the process of being deciphered and published by Brice Jones, a PhD student at Concordia University. Until now the texts had not been studied and few knew of their existence.

Several ancient and medieval texts at McGill University Library and Archives are in the process of being deciphered and published by Brice Jones, a PhD student at Concordia University. Until now the texts had not been studied and few knew of their existence.

Credit: Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library and Archives

Tax day is nearing in the United States, and people are scrambling to file their returns before the April 15 deadline. While this is never fun, people can take solace in a new finding: A recently translated ancient Egyptian tax receipt shows a bill that is (literally) heavier than any American taxpayer will pay this year — more than 220 lbs. (100 kilograms) of coins.

Written in Greek on a piece of pottery, the receipt states that a person (the name is unreadable) and his friends paid a land-transfer tax that came to 75 "talents" (a unit of currency), with a 15-talent charge added on. The tax was paid in coins and was delivered to a public bank in a city called Diospolis Magna (also known as Luxor or Thebes).

But just how much was 90 talents worth in ancient Egypt? [See photos of the ancient Egyptian tax receipt]

"It's an incredibly large sum of money," said Brice Jones, a Ph.D. student at Concordia University in Montreal, who translated the text. "These Egyptians were most likely very wealthy."

The receipt has a date on it that corresponds to July 22, 98 B.C. Paper money didn't exist at that time, and no coin was worth anywhere near one talent, the researchers said. Instead people made up the sum using coins that were worth varying amounts of drachma.

One talent equaled 6,000 drachma, so 90 talents totaled 540,000 drachma, researchers say. For comparison, an unskilled worker at that time would have made only about 18,000 drachmaa year said Catharine Lorber, an independent scholar who has published numerous journal articleson Egyptian coins.

In 98 B.C., the highest-denomination coin was probably worth only 40 drachms Lorber said. This made for a truly back-breaking tax load.

It "would have taken 150 of these coins to make a talent, and 13,500 of them to equal 90 talents," Lorber told Live Science in an email. "The coins in question weigh, on average, 8 grams [0.3 ounces], so the total payment of 90 talents probably had a weight in excess of 100 kilograms [220 lbs.]."

What likely happened is that one or more tax farmers (people charged with collecting certain types of taxes) got 90 talents' worth of coins from the individuals paying this tax, the researchers said. These tax farmers then would have had to physically bring the cash into the bank. Lorber noted that the Ptolemies (the ruling dynasty in Egypt at the time) required tax farmers to absorb the cost of transport and handling. In cases where tax farmers had to bring in a big load, "it was packed in baskets and carried by donkeys," Lorber said. [6 Odd Historical Tax Facts]

The 15-talent surcharge, which was added on to the 75-talent tax bill, suggests that the people paying this land-transfer tax were penalized for not paying part of the bill in silver — a charge that was called the "allage," Lorber said.

"This was an exchange fee imposed on bronze currency when it was used to pay an obligation that legally should have been paid in silver," Lorber said. "This system was maintained even in periods when silver coinage was scarcely available."

Egyptian infighting

Today, people often complain about political gridlock and conflict on Capitol Hill, but this is likely nothing compared to the drama and infighting among Egypt's rulers around the time this newly translated bill was paid.

Around 98 B.C., Egypt's politics were volatile, to say the least. At the time, Egypt was ruled by Ptolemy X, a pharaoh who fought against his own brother for the throne. Some ancient writers even say he killed his own mother in 101 B.C. so he wouldn't have to share power with her.

Ptolemy X was part of a dynasty of pharaohs of Macedonian descent who ruled Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great.

Modern-day historians cast doubt on the ancient claim that Ptolemy X murdered his own mom, but in any event, he eventually lost power. In 89 B.C., his own army turned against him, and he was killed the following year. His brother Ptolemy IX then took over the country.

The ancient tax receipt is located at McGill University Library and Archives in Montreal. Jones is studying and translating several texts from the library and is set to publish his findings in an upcoming issue of the journal Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists.

Live Science

Several ancient and medieval texts at McGill University Library and Archives are in the process of being deciphered and published by Brice Jones, a PhD student at Concordia University. Until now the texts had not been studied and few knew of their existence.

Several ancient and medieval texts at McGill University Library and Archives are in the process of being deciphered and published by Brice Jones, a PhD student at Concordia University. Until now the texts had not been studied and few knew of their existence. Credit: Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library and Archives

Tax day is nearing in the United States, and people are scrambling to file their returns before the April 15 deadline. While this is never fun, people can take solace in a new finding: A recently translated ancient Egyptian tax receipt shows a bill that is (literally) heavier than any American taxpayer will pay this year — more than 220 lbs. (100 kilograms) of coins.

Written in Greek on a piece of pottery, the receipt states that a person (the name is unreadable) and his friends paid a land-transfer tax that came to 75 "talents" (a unit of currency), with a 15-talent charge added on. The tax was paid in coins and was delivered to a public bank in a city called Diospolis Magna (also known as Luxor or Thebes).

But just how much was 90 talents worth in ancient Egypt? [See photos of the ancient Egyptian tax receipt]

"It's an incredibly large sum of money," said Brice Jones, a Ph.D. student at Concordia University in Montreal, who translated the text. "These Egyptians were most likely very wealthy."

The receipt has a date on it that corresponds to July 22, 98 B.C. Paper money didn't exist at that time, and no coin was worth anywhere near one talent, the researchers said. Instead people made up the sum using coins that were worth varying amounts of drachma.

One talent equaled 6,000 drachma, so 90 talents totaled 540,000 drachma, researchers say. For comparison, an unskilled worker at that time would have made only about 18,000 drachmaa year said Catharine Lorber, an independent scholar who has published numerous journal articleson Egyptian coins.

In 98 B.C., the highest-denomination coin was probably worth only 40 drachms Lorber said. This made for a truly back-breaking tax load.

It "would have taken 150 of these coins to make a talent, and 13,500 of them to equal 90 talents," Lorber told Live Science in an email. "The coins in question weigh, on average, 8 grams [0.3 ounces], so the total payment of 90 talents probably had a weight in excess of 100 kilograms [220 lbs.]."

What likely happened is that one or more tax farmers (people charged with collecting certain types of taxes) got 90 talents' worth of coins from the individuals paying this tax, the researchers said. These tax farmers then would have had to physically bring the cash into the bank. Lorber noted that the Ptolemies (the ruling dynasty in Egypt at the time) required tax farmers to absorb the cost of transport and handling. In cases where tax farmers had to bring in a big load, "it was packed in baskets and carried by donkeys," Lorber said. [6 Odd Historical Tax Facts]

The 15-talent surcharge, which was added on to the 75-talent tax bill, suggests that the people paying this land-transfer tax were penalized for not paying part of the bill in silver — a charge that was called the "allage," Lorber said.

"This was an exchange fee imposed on bronze currency when it was used to pay an obligation that legally should have been paid in silver," Lorber said. "This system was maintained even in periods when silver coinage was scarcely available."

Egyptian infighting

Today, people often complain about political gridlock and conflict on Capitol Hill, but this is likely nothing compared to the drama and infighting among Egypt's rulers around the time this newly translated bill was paid.

Around 98 B.C., Egypt's politics were volatile, to say the least. At the time, Egypt was ruled by Ptolemy X, a pharaoh who fought against his own brother for the throne. Some ancient writers even say he killed his own mother in 101 B.C. so he wouldn't have to share power with her.

Ptolemy X was part of a dynasty of pharaohs of Macedonian descent who ruled Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great.

Modern-day historians cast doubt on the ancient claim that Ptolemy X murdered his own mom, but in any event, he eventually lost power. In 89 B.C., his own army turned against him, and he was killed the following year. His brother Ptolemy IX then took over the country.

The ancient tax receipt is located at McGill University Library and Archives in Montreal. Jones is studying and translating several texts from the library and is set to publish his findings in an upcoming issue of the journal Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists.

Published on March 15, 2015 06:29

Beware the Ides of March

March 15, 44 BC Julius Caesar, Dictator of the Roman Republic, was stabbed to death by Marcus Junius Brutus, Gaius Cassius Longinus, Decimus Junius Brutus and several other Roman senators on the Ides of March. He had appointed his great-nephew, Octavian, as his heir. Civil war broke out between Caesar's assassins and his successors (Mark Antony and Octavian).

Published on March 15, 2015 02:30

History Trivia - Theodorik the Great defeats Odoaker of Italy

March 15

44 BC Julius Caesar, Dictator of the Roman Republic, was stabbed to death .

351 Constantius II elevated his cousin Gallus to Caesar, and put him in charge of the Eastern part of the Roman Empire.

493 Theodorik the Great defeated Odoaker of Italy.

44 BC Julius Caesar, Dictator of the Roman Republic, was stabbed to death .

351 Constantius II elevated his cousin Gallus to Caesar, and put him in charge of the Eastern part of the Roman Empire.

493 Theodorik the Great defeated Odoaker of Italy.

Published on March 15, 2015 01:00

March 14, 2015

Neanderthals wore eagle talons as jewelry 130,000 years ago

Fox NewsMegan Gannon

The eight eagle talons from Krapina arranged with an eagle phalanx that was also found at the site. (Luka Mjeda, Zagreb)

The eight eagle talons from Krapina arranged with an eagle phalanx that was also found at the site. (Luka Mjeda, Zagreb)

Long before they shared the landscape with modern humans, Neanderthals in Europe developed a sharp sense of style, wearing eagle claws as jewelry, new evidence suggests.

Researchers identified eight talons from white-tailed eagles — including four that had distinct notches and cut marks — from a 130,000-year-old Neanderthal cave in Croatia. They suspect the claws were once strung together as part of a necklace or bracelet.

"It really is absolutely stunning," study author David Frayer, an anthropology professor at the University of Kansas, told Live Science. "It fits in with this general picture that's emerging that Neanderthals were much more modern in their behavior." [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

The talons were first excavated more than 100 years ago at a famous sandstone rock-shelter site called Krapina in Croatia. There, archaeologists found more than 900 Neanderthal bones dating back to a relatively warm, interglacial period about 120,000 to 130,000 years ago. They also found Mousterian stone tools (a telltale sign of Neanderthal occupation), a hearth and the bones of rhinos and cave bears, but no signs of modern human occupation. Homo sapiens didn't spread into Europe until about 40,000 years ago.

The eagle talons were all found in the same archaeological layer, Frayer said, and they had been studied a few times before. But no one noticed the cut marks until last year, when Davorka Radov?i?, curator of the Croatian Natural History Museum, was reassessing some of the Krapina objects in the collection.

The researchers don't know exactly how the talons would have been assembled into jewelry. But Frayer said some facets on the claws look quite polished — perhaps made smooth from being wrapped in some kind of fiber, or from rubbing against the surface of the other talons. There were also nicks in three of the talons that wouldn't have been created during an eagle's life, Frayer said.

Now extinct, Neanderthals were the closest known relatives of modern humans. They lived in Eurasia from about 200,000 to 30,000 years ago. Recent research has uncovered evidence that Neanderthals may have engaged in some familiar behaviors, such as burying their dead, adorning themselves with feathers and even making art.

But scientists debate the extent to which Neanderthals were capable of abstract thinking. Deliberately making or wearing jewelry would suggest some degree of symbolic thought, as well as planning, Frayer explained. And the age of the talons suggests that if the Neanderthals were indeed wearing jewelry, they didn't pick up on the trend from modern humans.

"Eagle talons are not easy to find," Frayer said. "My guess is that they were catching the birds live — which also isn't easy."

The findings were published March 11 in the journal PLOS ONE.

The eight eagle talons from Krapina arranged with an eagle phalanx that was also found at the site. (Luka Mjeda, Zagreb)

The eight eagle talons from Krapina arranged with an eagle phalanx that was also found at the site. (Luka Mjeda, Zagreb)Long before they shared the landscape with modern humans, Neanderthals in Europe developed a sharp sense of style, wearing eagle claws as jewelry, new evidence suggests.

Researchers identified eight talons from white-tailed eagles — including four that had distinct notches and cut marks — from a 130,000-year-old Neanderthal cave in Croatia. They suspect the claws were once strung together as part of a necklace or bracelet.

"It really is absolutely stunning," study author David Frayer, an anthropology professor at the University of Kansas, told Live Science. "It fits in with this general picture that's emerging that Neanderthals were much more modern in their behavior." [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

The talons were first excavated more than 100 years ago at a famous sandstone rock-shelter site called Krapina in Croatia. There, archaeologists found more than 900 Neanderthal bones dating back to a relatively warm, interglacial period about 120,000 to 130,000 years ago. They also found Mousterian stone tools (a telltale sign of Neanderthal occupation), a hearth and the bones of rhinos and cave bears, but no signs of modern human occupation. Homo sapiens didn't spread into Europe until about 40,000 years ago.

The eagle talons were all found in the same archaeological layer, Frayer said, and they had been studied a few times before. But no one noticed the cut marks until last year, when Davorka Radov?i?, curator of the Croatian Natural History Museum, was reassessing some of the Krapina objects in the collection.

The researchers don't know exactly how the talons would have been assembled into jewelry. But Frayer said some facets on the claws look quite polished — perhaps made smooth from being wrapped in some kind of fiber, or from rubbing against the surface of the other talons. There were also nicks in three of the talons that wouldn't have been created during an eagle's life, Frayer said.

Now extinct, Neanderthals were the closest known relatives of modern humans. They lived in Eurasia from about 200,000 to 30,000 years ago. Recent research has uncovered evidence that Neanderthals may have engaged in some familiar behaviors, such as burying their dead, adorning themselves with feathers and even making art.

But scientists debate the extent to which Neanderthals were capable of abstract thinking. Deliberately making or wearing jewelry would suggest some degree of symbolic thought, as well as planning, Frayer explained. And the age of the talons suggests that if the Neanderthals were indeed wearing jewelry, they didn't pick up on the trend from modern humans.

"Eagle talons are not easy to find," Frayer said. "My guess is that they were catching the birds live — which also isn't easy."

The findings were published March 11 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Published on March 14, 2015 06:33