MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 188

March 18, 2015

Ancient Rome – 6 burning questions

Emma McFarnon

History Extra

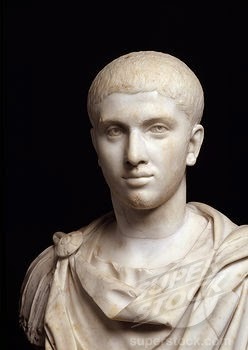

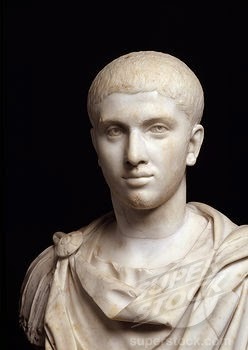

© Papepi | Dreamstime.com

© Papepi | Dreamstime.com

Who founded Ancient Rome?Like all ancient societies, the Romans possessed a heroic foundation story. What made the Romans different, however, is that they created two distinct creation myths for themselves.

In the first it was claimed that they were descended from the royal Trojan refugee Aeneas (himself the son of the goddess Venus). In the second it was stated that the city of Rome was founded by, and ultimately named after, Romulus, son of a union between an earthly princess and the god Mars.

Both myths helped establish the Romans as a divinely chosen people whose ancestry could be traced back to Troy and the Hellenistic world. Roman tradition had Romulus’ foundling city established on the Palatine Hill in what became, for Rome, ‘Year One’ (or 753 BC in the Christian calendar of the West). Archaeological excavation on the hill has found settlement here dating back to at least 1000 BC.

Who ruled in Ancient Rome?Rome made much of the fact that it was a republic, ruled by the people and not by kings.

Rome had overthrown its monarchy in 509 BC, and legislative power was thereafter vested in the people’s assemblies: political power in the senate, and military power with two annually elected magistrates known as consuls.

The acronym ‘SPQR’, for Senatus Populusque Romanus (‘the Senate and People of Rome’) was proudly emblazoned across inscriptions and military standards throughout the Mediterranean – a reminder that Rome’s people (theoretically) had the last word.

By the late 1st century BC, the combination of power-hungry politicians and large overseas territories resulted in the breakdown of traditional systems of government. Even after the rise of the emperors – kings in all but name, who ‘guided’ the Roman political system in the 1st century AD – ‘SPQR’ continued to be used in order to sustain the fiction that Rome was a state governed by purely republican principles.

Who were gladiators in ancient Rome?Gladiatorial games were organised by the elite throughout the Roman empire in order to distract the population from the reality of daily life.

Most gladiators were purchased from slave markets, being chosen for their strength, stamina and good looks. Although taken from the lowest elements of society, the gladiator was a breed apart from the ‘normal’ slave or prisoner of war, being well-trained combatants whose one role in life was to fight and occasionally to kill for the amusement of the Roman mob.

Not all those who fought as gladiators were slaves or convicts, however. Some were citizens down on their luck (or heavily in debt) while some, like the emperor Commodus, simply did it for ‘fun’.

Whatever their reasons for ending up in the arena, gladiators were adored by the Roman public for their bravery and spirit. Their images appeared frequently in mosaics, wall paintings and on glassware and pottery.

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).

Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

What did they eat in Ancient Rome?The Romans ate pretty much everything they could lay their hands on. Meat, especially pork and fish, however, were expensive commodities, and so the bulk of the population survived on cereals (wheat, emmer and barley) mixed with chickpeas, lentils, turnips, lettuce, leek, cabbage and fenugreek.

Olives, grapes, apples, plums and figs provided welcome relief from the traditional forms of thick, cereal-based porridge (tomatoes and potatoes were a much later introduction to the Mediterranean), while milk, cheese, eggs and bread were also daily staples.

The Romans liked to vary their cooking with sweet (honey) and sour (fermented fish) sauces, which often helpfully disguised the taste of rotten meat.

Dining as entertainment was practised within elite society – lavish dinner parties were the ideal way to show off wealth and status. Recipes compiled in the 4th century supply us with details of tasty treats such as pickled sow’s udders and stuffed dormice.

Why did Ancient Rome fall?A whole variety of reasons can be suggested to explain the fall of the Roman Empire in the west: disease, invasion, civil war, social unrest, inflation, economic collapse. In fact all were contributory factors, although key to the collapse of Roman authority was the prolonged period of imperial in-fighting during the 3rd and 4th century.

Conflict between multiple emperors severely weakened the military, eroded the economy and put a huge strain upon local populations. When Germanic migrants arrived, many western landowners threw their support behind the new ‘barbarian’ elite rather than continuing to back the emperor.

Reduced income from the provinces meant that Rome could no longer pay or feed its military and civil administration, making the imperial system of government redundant. The western half of the Roman empire mutated into a variety of discrete kingdoms while the east, which largely avoided both the in-fighting and barbarian migrations, survived until the 15th century.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication. These Q&As were taken from our ‘History Extra explains’ series, which answers burning questions about ancient Rome, the Tudors, ancient Egypt and the First World War. To read them, click here.

To keep up with our latest Ancient Rome Week features, click here. You can also follow the action with the hashtag #AncientRomeWeek on Twitter, and by visiting our homepage.

Tell us what you think by tweeting us @HistoryExtra (don't forget the hashtag!) or by posting on our Facebook page.

History Extra

© Papepi | Dreamstime.com

© Papepi | Dreamstime.com Who founded Ancient Rome?Like all ancient societies, the Romans possessed a heroic foundation story. What made the Romans different, however, is that they created two distinct creation myths for themselves.

In the first it was claimed that they were descended from the royal Trojan refugee Aeneas (himself the son of the goddess Venus). In the second it was stated that the city of Rome was founded by, and ultimately named after, Romulus, son of a union between an earthly princess and the god Mars.

Both myths helped establish the Romans as a divinely chosen people whose ancestry could be traced back to Troy and the Hellenistic world. Roman tradition had Romulus’ foundling city established on the Palatine Hill in what became, for Rome, ‘Year One’ (or 753 BC in the Christian calendar of the West). Archaeological excavation on the hill has found settlement here dating back to at least 1000 BC.

Who ruled in Ancient Rome?Rome made much of the fact that it was a republic, ruled by the people and not by kings.

Rome had overthrown its monarchy in 509 BC, and legislative power was thereafter vested in the people’s assemblies: political power in the senate, and military power with two annually elected magistrates known as consuls.

The acronym ‘SPQR’, for Senatus Populusque Romanus (‘the Senate and People of Rome’) was proudly emblazoned across inscriptions and military standards throughout the Mediterranean – a reminder that Rome’s people (theoretically) had the last word.

By the late 1st century BC, the combination of power-hungry politicians and large overseas territories resulted in the breakdown of traditional systems of government. Even after the rise of the emperors – kings in all but name, who ‘guided’ the Roman political system in the 1st century AD – ‘SPQR’ continued to be used in order to sustain the fiction that Rome was a state governed by purely republican principles.

Who were gladiators in ancient Rome?Gladiatorial games were organised by the elite throughout the Roman empire in order to distract the population from the reality of daily life.

Most gladiators were purchased from slave markets, being chosen for their strength, stamina and good looks. Although taken from the lowest elements of society, the gladiator was a breed apart from the ‘normal’ slave or prisoner of war, being well-trained combatants whose one role in life was to fight and occasionally to kill for the amusement of the Roman mob.

Not all those who fought as gladiators were slaves or convicts, however. Some were citizens down on their luck (or heavily in debt) while some, like the emperor Commodus, simply did it for ‘fun’.

Whatever their reasons for ending up in the arena, gladiators were adored by the Roman public for their bravery and spirit. Their images appeared frequently in mosaics, wall paintings and on glassware and pottery.

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).

Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

What did they eat in Ancient Rome?The Romans ate pretty much everything they could lay their hands on. Meat, especially pork and fish, however, were expensive commodities, and so the bulk of the population survived on cereals (wheat, emmer and barley) mixed with chickpeas, lentils, turnips, lettuce, leek, cabbage and fenugreek.

Olives, grapes, apples, plums and figs provided welcome relief from the traditional forms of thick, cereal-based porridge (tomatoes and potatoes were a much later introduction to the Mediterranean), while milk, cheese, eggs and bread were also daily staples.

The Romans liked to vary their cooking with sweet (honey) and sour (fermented fish) sauces, which often helpfully disguised the taste of rotten meat.

Dining as entertainment was practised within elite society – lavish dinner parties were the ideal way to show off wealth and status. Recipes compiled in the 4th century supply us with details of tasty treats such as pickled sow’s udders and stuffed dormice.

Why did Ancient Rome fall?A whole variety of reasons can be suggested to explain the fall of the Roman Empire in the west: disease, invasion, civil war, social unrest, inflation, economic collapse. In fact all were contributory factors, although key to the collapse of Roman authority was the prolonged period of imperial in-fighting during the 3rd and 4th century.

Conflict between multiple emperors severely weakened the military, eroded the economy and put a huge strain upon local populations. When Germanic migrants arrived, many western landowners threw their support behind the new ‘barbarian’ elite rather than continuing to back the emperor.

Reduced income from the provinces meant that Rome could no longer pay or feed its military and civil administration, making the imperial system of government redundant. The western half of the Roman empire mutated into a variety of discrete kingdoms while the east, which largely avoided both the in-fighting and barbarian migrations, survived until the 15th century.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication. These Q&As were taken from our ‘History Extra explains’ series, which answers burning questions about ancient Rome, the Tudors, ancient Egypt and the First World War. To read them, click here.

To keep up with our latest Ancient Rome Week features, click here. You can also follow the action with the hashtag #AncientRomeWeek on Twitter, and by visiting our homepage.

Tell us what you think by tweeting us @HistoryExtra (don't forget the hashtag!) or by posting on our Facebook page.

Published on March 18, 2015 08:44

'Blood Moon' May Have Shone on Richard III's Dead Body

Megan Gannon,

Live Science

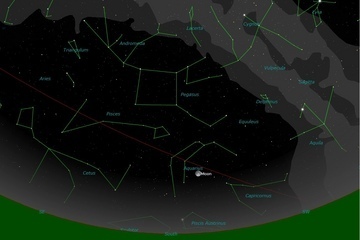

This is what the night sky would have looked like for someone standing in Leicester, England, at 9:50 p.m. on Aug. 25, 1485, with with a partial lunar eclipse.

This is what the night sky would have looked like for someone standing in Leicester, England, at 9:50 p.m. on Aug. 25, 1485, with with a partial lunar eclipse.

Credit: Colin Brooks View full size image

In just a matter of days, Richard III will get a long-overdue royal burial in Leicester, England. The last time the king's body was laid to rest, more than 500 years ago, a "blood moon" might have shone over his naked, heavily wounded corpse, an astronomical simulation suggests.

Richard's two-year reign ended when he died on Aug. 22, 1485, during the Battle of Bosworth Field, the decisive fight in the Wars of the Roses, an English civil war. After the battle, Henry Tudor was established as the new English monarch, and Richard wasn't exactly given a ceremonious funeral.

Rather, historical sources indicate that Richard's gravely injured body was stripped naked and carried by horseback to Leicester to be put on a humiliating display for several days under the arches of the Church of the Annunciation. [Gallery: The Search for Richard III in Photos]

The exact location of Richard's grave was lost for centuries. When archaeologists found it in 2012, they discovered Richard's skeleton buried in a hastily dug grave under the floor of the ruins of a monastery known as Grey Friars in Leicester. He had no coffin and no shroud, and his hands may have been tied in front of him.

Looking for more insight on important moments in King Richard's life (and death), Colin Brooks, a member of the Leicester Astronomical Society and the chief photographer at the University of Leicester (the institution that has spearheaded the search for Richard's grave), turned to historical data from NASA on the position of the moon, planets and stars. Brooks found there was a partial lunar eclipse three days after Richard was killed, on Aug. 25, 1485.

"A lunar eclipse can be quite red depending on the amount of dust thats in the atmosphere," Brooks told Live Science. Sometimes this phenomenon is nicknamed a "blood moon."

Brooks said he didn't find any historical sources that mentioned a blood moon over Richard's body, but he thinks a partial lunar eclipse wouldn't have been as noticeable or ominous as a solar eclipse — like the one that darkened English skies on the day that Richard's wife, Anne Neville, died.

Scientists spent more than two years studying Richard's bones while controversy and legal battles brewed over how and where to reinter the remains. Beginning on Sunday (March 22), there will be a week of events and ceremonies leading up to Richard's final reburial in Leicester Cathedral.

Live Science

This is what the night sky would have looked like for someone standing in Leicester, England, at 9:50 p.m. on Aug. 25, 1485, with with a partial lunar eclipse.

This is what the night sky would have looked like for someone standing in Leicester, England, at 9:50 p.m. on Aug. 25, 1485, with with a partial lunar eclipse.Credit: Colin Brooks View full size image

In just a matter of days, Richard III will get a long-overdue royal burial in Leicester, England. The last time the king's body was laid to rest, more than 500 years ago, a "blood moon" might have shone over his naked, heavily wounded corpse, an astronomical simulation suggests.

Richard's two-year reign ended when he died on Aug. 22, 1485, during the Battle of Bosworth Field, the decisive fight in the Wars of the Roses, an English civil war. After the battle, Henry Tudor was established as the new English monarch, and Richard wasn't exactly given a ceremonious funeral.

Rather, historical sources indicate that Richard's gravely injured body was stripped naked and carried by horseback to Leicester to be put on a humiliating display for several days under the arches of the Church of the Annunciation. [Gallery: The Search for Richard III in Photos]

The exact location of Richard's grave was lost for centuries. When archaeologists found it in 2012, they discovered Richard's skeleton buried in a hastily dug grave under the floor of the ruins of a monastery known as Grey Friars in Leicester. He had no coffin and no shroud, and his hands may have been tied in front of him.

Looking for more insight on important moments in King Richard's life (and death), Colin Brooks, a member of the Leicester Astronomical Society and the chief photographer at the University of Leicester (the institution that has spearheaded the search for Richard's grave), turned to historical data from NASA on the position of the moon, planets and stars. Brooks found there was a partial lunar eclipse three days after Richard was killed, on Aug. 25, 1485.

"A lunar eclipse can be quite red depending on the amount of dust thats in the atmosphere," Brooks told Live Science. Sometimes this phenomenon is nicknamed a "blood moon."

Brooks said he didn't find any historical sources that mentioned a blood moon over Richard's body, but he thinks a partial lunar eclipse wouldn't have been as noticeable or ominous as a solar eclipse — like the one that darkened English skies on the day that Richard's wife, Anne Neville, died.

Scientists spent more than two years studying Richard's bones while controversy and legal battles brewed over how and where to reinter the remains. Beginning on Sunday (March 22), there will be a week of events and ceremonies leading up to Richard's final reburial in Leicester Cathedral.

Published on March 18, 2015 08:39

'For Allah' Inscription Found on Viking Era Ring

Rossella Lorenzi, Discovery News

Live Science

The Viking Age ring with the Arabic inscription.

The Viking Age ring with the Arabic inscription.

Credit: Christer Åhlin/Swedish History Museum View full size image

Ancient tales about Viking expeditions to Islamic countries had some elements of truth, according to recent analysis of a ring recovered from a 9th century Swedish grave.

Featuring a pink-violet colored stone with an inscription that reads “for Allah” or “to Allah,” the silver ring was found during the 1872-1895 excavations of grave fields at the Viking age trading center of Birka, some 15.5 miles west of Stockholm.

center of Birka, some 15.5 miles west of Stockholm.

It was recovered from a rectangular wooden coffin along with jewelry, brooches and remains of clothes. Although the skeleton was completely decomposed, the objects indicated it was a female burial dating to about 850 A.D.

The ring was cataloged at the Swedish History Museum in Stockholm as a signet ring consisting of gilded silver set with an amethyst inscribed with the word “Allah” in Arabic Kufic writing.

The object attracted the attention of an international team of researchers led by biophysicist Sebastian Wärmländer of Stockholm University.

team of researchers led by biophysicist Sebastian Wärmländer of Stockholm University.

“It’s the only ring with an Arabic inscription found in Scandinavia. We have a few other Arabic-style rings, but without inscriptions,” Wärmländer told Discovery News.

Video: Mythical Viking Sunstone is Real

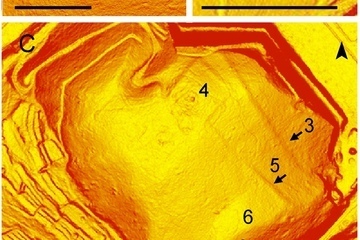

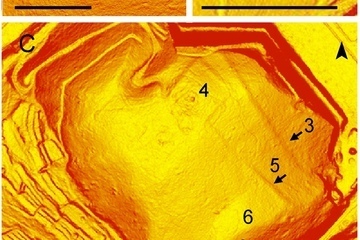

Using a scanning electron microscope, the researchers discovered that the museum description wasn’t entirely correct.

“Our analysis shows that the studied ring consists of a high quality (94.5 percent) non-gilded silver alloy, set with a stone of colored soda-lime glass with an Arabic inscription reading some version of the word Allah,” Wärmländer and colleagues wrote in the journal Scanning.

(94.5 percent) non-gilded silver alloy, set with a stone of colored soda-lime glass with an Arabic inscription reading some version of the word Allah,” Wärmländer and colleagues wrote in the journal Scanning.

Although the stone wasn’t an amethyst, as long presumed, it wasn’t necessarily a material of lower value.

“Colored glass was an exotic material in Viking Age Scandinavia,” Wärmländer said.

A closer inspection revealed the glass was engraved with early Kufic characters, consistent with the grave at Birka dating to around 850 A.D.

Mysterious Toe Rings Found on Ancient Skeletons

The researchers interpreted the inscription as “il-la-lah,” meaning “For/To Allah.” Alternative interpretations of the engraving are possible, and the letters could also be read as “INs…LLH” meaning “Inshallah” (God-willing).

“Most likely, we will never know the exact meaning behind the inscription, or where and why it was done,” the researchers wrote.

Viking ‘Hammer of Thor’ Unearthed

“For the present investigation, it is enough to note that its Arabic-Islamic nature clearly links the ring and the stone to the cultural sphere of the Caliphate,” they added.

Most interestingly, Wärmländer and colleagues noted the ring body is in mint condition.

“On this ring the filing marks are still present on the metal surface. This shows the jewel has never been much used, and indicates that it did not have many owners,” Wärmländer said.

In other words, the ring did not accidentally end up in Birka after being traded or exchanged between many different people.

“Instead, it must have passed from the Islamic silversmith who made it to the woman buried at Birka with few, if any, owners in between,” Wärmländer said.

Viking Women Colonized New Lands, Too

“Perhaps the woman herself was from the Islamic world, or perhaps a Swedish Viking got the ring, by trade or robbery, while visiting the Islamic Caliphate,” he added.

or robbery, while visiting the Islamic Caliphate,” he added.

Either way, the ring constitutes evidence for direct interactions between the Vikings and the Islamic world, the researchers concluded.

“The Viking Sagas and Chronicles tell us of Viking expeditions to the Black and Caspian Seas, and beyond, but we don’t know what is fact and what is fiction in these stories,” Wärmländer said.

“The mint condition of the ring corroborates ancient tales about direct contacts between Viking Age Scandinavia and the Islamic world,” he said.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Live Science

The Viking Age ring with the Arabic inscription.

The Viking Age ring with the Arabic inscription.Credit: Christer Åhlin/Swedish History Museum View full size image

Ancient tales about Viking expeditions to Islamic countries had some elements of truth, according to recent analysis of a ring recovered from a 9th century Swedish grave.

Featuring a pink-violet colored stone with an inscription that reads “for Allah” or “to Allah,” the silver ring was found during the 1872-1895 excavations of grave fields at the Viking age trading

center of Birka, some 15.5 miles west of Stockholm.

center of Birka, some 15.5 miles west of Stockholm.It was recovered from a rectangular wooden coffin along with jewelry, brooches and remains of clothes. Although the skeleton was completely decomposed, the objects indicated it was a female burial dating to about 850 A.D.

The ring was cataloged at the Swedish History Museum in Stockholm as a signet ring consisting of gilded silver set with an amethyst inscribed with the word “Allah” in Arabic Kufic writing.

The object attracted the attention of an international

team of researchers led by biophysicist Sebastian Wärmländer of Stockholm University.

team of researchers led by biophysicist Sebastian Wärmländer of Stockholm University.“It’s the only ring with an Arabic inscription found in Scandinavia. We have a few other Arabic-style rings, but without inscriptions,” Wärmländer told Discovery News.

Video: Mythical Viking Sunstone is Real

Using a scanning electron microscope, the researchers discovered that the museum description wasn’t entirely correct.

“Our analysis shows that the studied ring consists of a high quality

(94.5 percent) non-gilded silver alloy, set with a stone of colored soda-lime glass with an Arabic inscription reading some version of the word Allah,” Wärmländer and colleagues wrote in the journal Scanning.

(94.5 percent) non-gilded silver alloy, set with a stone of colored soda-lime glass with an Arabic inscription reading some version of the word Allah,” Wärmländer and colleagues wrote in the journal Scanning.Although the stone wasn’t an amethyst, as long presumed, it wasn’t necessarily a material of lower value.

“Colored glass was an exotic material in Viking Age Scandinavia,” Wärmländer said.

A closer inspection revealed the glass was engraved with early Kufic characters, consistent with the grave at Birka dating to around 850 A.D.

Mysterious Toe Rings Found on Ancient Skeletons

The researchers interpreted the inscription as “il-la-lah,” meaning “For/To Allah.” Alternative interpretations of the engraving are possible, and the letters could also be read as “INs…LLH” meaning “Inshallah” (God-willing).

“Most likely, we will never know the exact meaning behind the inscription, or where and why it was done,” the researchers wrote.

Viking ‘Hammer of Thor’ Unearthed

“For the present investigation, it is enough to note that its Arabic-Islamic nature clearly links the ring and the stone to the cultural sphere of the Caliphate,” they added.

Most interestingly, Wärmländer and colleagues noted the ring body is in mint condition.

“On this ring the filing marks are still present on the metal surface. This shows the jewel has never been much used, and indicates that it did not have many owners,” Wärmländer said.

In other words, the ring did not accidentally end up in Birka after being traded or exchanged between many different people.

“Instead, it must have passed from the Islamic silversmith who made it to the woman buried at Birka with few, if any, owners in between,” Wärmländer said.

Viking Women Colonized New Lands, Too

“Perhaps the woman herself was from the Islamic world, or perhaps a Swedish Viking got the ring, by trade

or robbery, while visiting the Islamic Caliphate,” he added.

or robbery, while visiting the Islamic Caliphate,” he added.Either way, the ring constitutes evidence for direct interactions between the Vikings and the Islamic world, the researchers concluded.

“The Viking Sagas and Chronicles tell us of Viking expeditions to the Black and Caspian Seas, and beyond, but we don’t know what is fact and what is fiction in these stories,” Wärmländer said.

“The mint condition of the ring corroborates ancient tales about direct contacts between Viking Age Scandinavia and the Islamic world,” he said.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Published on March 18, 2015 08:35

Richard III's Remains Sealed Inside Coffin

Rossella Lorenzi

Discovery News

King Richard III’s twisted skeleton was sealed inside a coffin at a private ceremony Sunday, the University of Leicester announced Tuesday.

King Richard III’s twisted skeleton was sealed inside a coffin at a private ceremony Sunday, the University of Leicester announced Tuesday.

During the ceremony, the king’s bones were laid out as if articulated in a lead casket along with bone fragments and scientific samples wrapped up in linen bags.The lead casket had been placed inside a 5-foot, 10-inch oak coffin built by Michael Ibsen, a descendant of Richard III’s elder sister, Anne of York.

“In order to pack the bones into the lead lined coffin, natural materials sourced from the British Isles which would have existed in the medieval period were used,” the University of Leicester said in a statement. “A combination of washed natural woolen fleece, wadding and unbleached linen were used for the layers of packing."

Face of Richard III Reconstructed

A rosary was also placed in the inner coffin and the final layer was an embroidered piece of Irish linen.

Once the lead casket was sealed, Ibsen fixed the lid of the outer coffin in position.

The ceremony -- carried ahead of the king’s reburial at Leicester’s Cathedral on March 26 -- was witnessed by representatives from the university, Leicester Cathedral, the City Council, the Richard III Society, an independent witness and relatives of Richard III who donated their DNA as part of the identification process.

All Hail King Richard! Details of Elaborate Burial Unveiled

The skeleton was found in 2012 beneath a car park. Mitochondrial DNA showed a match between Richard and two of his living relatives, confirming that the bones are indeed those of the king.

Further analysis shed light on his diet and disease, and even provided a blow-by-blow account of his final moments.

Depicted by William Shakespeare as a bloodthirsty usurper, Richard ruled England from 1483 to 1485. He was killed in 1485 in the Battle of Bosworth, which was the last act of the decades-long fight over the throne known as War of the Roses. England’s last king to die in battle, he was defeated by Henry Tudor, who became King Henry VII.

Richard III Killed by Sword Thrust Upwards Into Neck

Richard III’s coffin will travel through Leicestershire in a funeral procession on Sunday, March 22 before a service at the cathedral.

The following Thursday, after having rested in the Cathedral for four days, the mortal remains of Richard III will be finally reburied.

“The reinterment is considered to be a final act and there are no plans to reopen the tomb in the future,” the University of Leicester said.

Image: King Richard III’s twisted skeleton. Credit: University of Leicester

Discovery News

King Richard III’s twisted skeleton was sealed inside a coffin at a private ceremony Sunday, the University of Leicester announced Tuesday.

King Richard III’s twisted skeleton was sealed inside a coffin at a private ceremony Sunday, the University of Leicester announced Tuesday.During the ceremony, the king’s bones were laid out as if articulated in a lead casket along with bone fragments and scientific samples wrapped up in linen bags.The lead casket had been placed inside a 5-foot, 10-inch oak coffin built by Michael Ibsen, a descendant of Richard III’s elder sister, Anne of York.

“In order to pack the bones into the lead lined coffin, natural materials sourced from the British Isles which would have existed in the medieval period were used,” the University of Leicester said in a statement. “A combination of washed natural woolen fleece, wadding and unbleached linen were used for the layers of packing."

Face of Richard III Reconstructed

A rosary was also placed in the inner coffin and the final layer was an embroidered piece of Irish linen.

Once the lead casket was sealed, Ibsen fixed the lid of the outer coffin in position.

The ceremony -- carried ahead of the king’s reburial at Leicester’s Cathedral on March 26 -- was witnessed by representatives from the university, Leicester Cathedral, the City Council, the Richard III Society, an independent witness and relatives of Richard III who donated their DNA as part of the identification process.

All Hail King Richard! Details of Elaborate Burial Unveiled

The skeleton was found in 2012 beneath a car park. Mitochondrial DNA showed a match between Richard and two of his living relatives, confirming that the bones are indeed those of the king.

Further analysis shed light on his diet and disease, and even provided a blow-by-blow account of his final moments.

Depicted by William Shakespeare as a bloodthirsty usurper, Richard ruled England from 1483 to 1485. He was killed in 1485 in the Battle of Bosworth, which was the last act of the decades-long fight over the throne known as War of the Roses. England’s last king to die in battle, he was defeated by Henry Tudor, who became King Henry VII.

Richard III Killed by Sword Thrust Upwards Into Neck

Richard III’s coffin will travel through Leicestershire in a funeral procession on Sunday, March 22 before a service at the cathedral.

The following Thursday, after having rested in the Cathedral for four days, the mortal remains of Richard III will be finally reburied.

“The reinterment is considered to be a final act and there are no plans to reopen the tomb in the future,” the University of Leicester said.

Image: King Richard III’s twisted skeleton. Credit: University of Leicester

Published on March 18, 2015 08:26

Missing monarchs: The kings who did not rest in peace

Greig Watson

BBC News

A king may expect an elaborate tomb as a perk of the job but the fates often have something else in mind

A king may expect an elaborate tomb as a perk of the job but the fates often have something else in mind

DNA tests may be about to prove a skeleton found beneath a Leicester car park are the mortal remains of King Richard III.

And while it may seem extraordinary that a king's grave could be lost, history shows the last of the Plantagenets was not the only one to suffer such indignity.

Here are seven English kings who have no confirmed grave.

Alfred the Great

Alfred beat the Vikings but may have met his match in a group of construction workers

Alfred beat the Vikings but may have met his match in a group of construction workers

Alfred, who turned back the tide of Viking conquest, died in 899 and was buried with due ceremony and pomp in the Old Minster in Winchester, Hampshire. His corpse was then moved twice, ending up across town in Hyde Abbey.

When Henry VIII moved to disband the monasteries in 1538, Hyde was dismantled. Tradition has it the graves of Alfred and his family were left undisturbed but subsequently ransacked during the construction of the town jail in 1788.

But Robin Iles, education officer for Winchester Museums, said the truth was uncertain: "The decorated tombs would have been an obvious target for those stripping the abbey of valuables in 1538 but there was also a lot of disturbance during the building of the prison. The truth is we don't know what happened.

"An excavation in the 1990s confirmed where the tombs used to be and slabs now mark the spot."

Harold II

Harold suffered one of the most famous deaths on one of the most famous dates in English history

Harold suffered one of the most famous deaths on one of the most famous dates in English history

As if being the last English king to have his country successfully invaded was not bad enough, Harold Godwinson's undoubted bravery and political manoeuvring did not guarantee a respectful burial.

His death in 1066 fighting William the Conqueror at the battle of Hastings - either by an arrow in the eye, the swords of cavalry, or possibly both - apparently left the body so mangled only his common-law wife, the ornithologically named Edith Swannesha (Swan-Neck), could identify the remains.

Rosemary Nicolaou, from Battle Abbey museum, said what happened next is confused: "We are told Harold's mother offered William a sum of gold equal to the weight of the body but William refused. He ordered it to be buried in secret to stop it becoming a shrine.

"After that we just don't know. There are various stories including his mother finally getting the body or it being taken by monks to Waltham Abbey, but nothing has been proved".

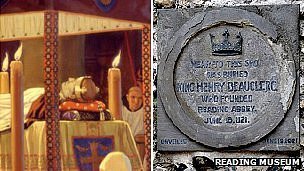

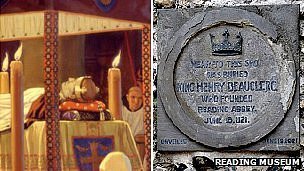

Henry I

Henry I's body was returned to England sewn into a bull's skin but the grave has vanished

Henry I's body was returned to England sewn into a bull's skin but the grave has vanished

A son of William the Conqueror, Henry seized the crown in August 1100 with a series of well organised political manoeuvres in the days after brother William II was killed in an apparent hunting accident. After Henry died in Normandy in December 1135, his corpse was brought back to England in singular style.

Jill Greenaway, collection care curator at Reading Museum, explained: "His body was embalmed, sewn into a bull's hide and brought to Reading where in January 1136 he was buried in front of the High Altar of the abbey that he had founded in 1121.

"His tomb did not survive the dissolution of the monasteries by his namesake Henry VIII and we do not know what happened to his body."

A small plaque marks the rough area of his grave but rumours place the exact spot under nearby St. James' School.

Stephen

King Stephen's bones may have been fished out of a ditch and placed in a nearby parish church

King Stephen's bones may have been fished out of a ditch and placed in a nearby parish church

After a reign so turbulent it was known as The Anarchy, it is perhaps no surprise Stephen also struggled for peace after his death in 1154. He was buried in a magnificent tomb in the newly constructed Faversham Abbey in Kent but - in what became a pattern - it was demolished on the orders of Henry VIII.

Local historian Jack Long said: "In John Stow's 'Annales' of 1580, he repeats the local legend that the royal tombs were desecrated for the lead coffins and any jewellery that the bodies might have worn, and the bones thrown into the creek.

"(It adds) they were retrieved and reburied in the church of St Mary of Charity in Faversham. There is an annexe (in the church) dating from the period but which has no original markings.

"To the best of my knowledge, no work has ever been undertaken to establish exactly what exists behind or below this mysterious annexe."

Edward V

The mystery and tragedy of the Princes in the Tower has inspired painters and playwrights

The mystery and tragedy of the Princes in the Tower has inspired painters and playwrights

Richard III plays a central role in one of the most emotionally charged stories in English history. In April 1483 Edward IV died leaving his 12-year-old son, also called Edward, as heir.

The dying king had appointed his brother, Richard of Gloucester, as the boy's protector. In short order Edward was placed in the Tower of London, had his coronation postponed and was then barred from the throne after his parents' marriage was declared illegitimate. In June Richard was declared king.

Along with his younger brother Richard, Edward was never seen outside the tower again.

In 1674, the skeletons of two children were discovered during building work in the tower and were reburied in Westminster Abbey under the names of the missing children but controversy rages as to who they really were - as well as the true fate of the princes and the identity of any killer.

Oliver Cromwell

The Royalists' revenge on Oliver Cromwell was a spectacular piece of macabre theatre

The Royalists' revenge on Oliver Cromwell was a spectacular piece of macabre theatre

Admittedly not a king, but Cromwell was certainly a head of state. And most of him has no grave.

After leading the Parliamentarian forces to victory in the civil war against Charles I, Cromwell took the reins of power until his death in 1658 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

When Charles II came to the throne in 1660, his supporters decided to enact a peculiarly spiteful form of vengeance, exhuming Cromwell's body and hanging it on the scaffold at Tyburn near modern day Marble Arch.

John Goldsmith, curator of the Cromwell Museum in Huntingdon, said: "It was then cut down and beheaded. Despite various stories about it being spirited away, his body was almost certainly dumped in a nearby pit.

"His embalmed head was later removed from a spike and went from owner to owner - including being an attraction in a travelling show - until eventually being reburied at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge in 1960."

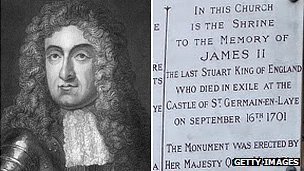

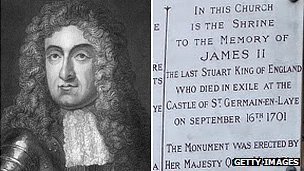

James II

James II refused to be buried in the hope his body might return to England

James II refused to be buried in the hope his body might return to England

Chased from the throne in 1688 for attempting to restore the absolute monarchy of his father Charles I, James lived in exile in Paris until his death and anatomical dissection in 1701.

He refused burial in the belief he would get his place in Westminster Abbey and the coffin was put in the Chapel of Saint Edmund in the Church of the English Benedictines in the Rue St Jacques.

His brain was sent to the Scots College in Paris and put in a silver case on top of a column, his heart went to the Convent of the Visitandine Nuns at Chaillot and his intestines were divided between the English Church of St Omer and the parish church of St Germain-en-Laye.

Aidan Dodson, author of The Royal Tombs of Great Britain, said: "It all disappeared in the French Revolution of 1789. The mob attacked the churches and his lead coffin was sold for scrap, as was the silver case for his brain.

"The church (of St Germain-en-Laye) was demolished but then rebuilt in 1824 and during this his intestines were found and reinterred - so a bit of him survives."

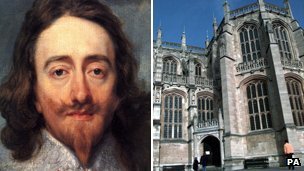

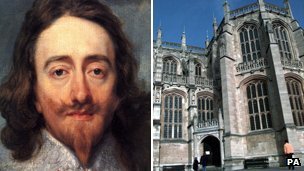

And one who was just mislaid... Charles I

The temporary loss of Charles I's grave ensured he never received an elaborate monument

The temporary loss of Charles I's grave ensured he never received an elaborate monument

After losing the Civil War, Charles's fortunes took a downward turn when he was executed in 1649. He was buried quietly in St George's Chapel, in Windsor Castle, after being denied a place in Westminster Abbey.

Mr Dodson said: "He was put in with Henry VIII and Jane Seymour but the problem was that they forgot where that entire vault was.

"This was also an excuse for Charles II to pocket the money parliament had given him for his dad's new tomb."

Workmen rediscovered the vault by accident in 1813 and found a velvet draped coffin with the missing monarch's name on it. To satisfy their curiosity, a group of notables opened the casket and, sure enough, found a body with a detached head and a pointy beard.

BBC News

A king may expect an elaborate tomb as a perk of the job but the fates often have something else in mind

A king may expect an elaborate tomb as a perk of the job but the fates often have something else in mind DNA tests may be about to prove a skeleton found beneath a Leicester car park are the mortal remains of King Richard III.

And while it may seem extraordinary that a king's grave could be lost, history shows the last of the Plantagenets was not the only one to suffer such indignity.

Here are seven English kings who have no confirmed grave.

Alfred the Great

Alfred beat the Vikings but may have met his match in a group of construction workers

Alfred beat the Vikings but may have met his match in a group of construction workers Alfred, who turned back the tide of Viking conquest, died in 899 and was buried with due ceremony and pomp in the Old Minster in Winchester, Hampshire. His corpse was then moved twice, ending up across town in Hyde Abbey.

When Henry VIII moved to disband the monasteries in 1538, Hyde was dismantled. Tradition has it the graves of Alfred and his family were left undisturbed but subsequently ransacked during the construction of the town jail in 1788.

But Robin Iles, education officer for Winchester Museums, said the truth was uncertain: "The decorated tombs would have been an obvious target for those stripping the abbey of valuables in 1538 but there was also a lot of disturbance during the building of the prison. The truth is we don't know what happened.

"An excavation in the 1990s confirmed where the tombs used to be and slabs now mark the spot."

Harold II

Harold suffered one of the most famous deaths on one of the most famous dates in English history

Harold suffered one of the most famous deaths on one of the most famous dates in English history As if being the last English king to have his country successfully invaded was not bad enough, Harold Godwinson's undoubted bravery and political manoeuvring did not guarantee a respectful burial.

His death in 1066 fighting William the Conqueror at the battle of Hastings - either by an arrow in the eye, the swords of cavalry, or possibly both - apparently left the body so mangled only his common-law wife, the ornithologically named Edith Swannesha (Swan-Neck), could identify the remains.

Rosemary Nicolaou, from Battle Abbey museum, said what happened next is confused: "We are told Harold's mother offered William a sum of gold equal to the weight of the body but William refused. He ordered it to be buried in secret to stop it becoming a shrine.

"After that we just don't know. There are various stories including his mother finally getting the body or it being taken by monks to Waltham Abbey, but nothing has been proved".

Henry I

Henry I's body was returned to England sewn into a bull's skin but the grave has vanished

Henry I's body was returned to England sewn into a bull's skin but the grave has vanished A son of William the Conqueror, Henry seized the crown in August 1100 with a series of well organised political manoeuvres in the days after brother William II was killed in an apparent hunting accident. After Henry died in Normandy in December 1135, his corpse was brought back to England in singular style.

Jill Greenaway, collection care curator at Reading Museum, explained: "His body was embalmed, sewn into a bull's hide and brought to Reading where in January 1136 he was buried in front of the High Altar of the abbey that he had founded in 1121.

"His tomb did not survive the dissolution of the monasteries by his namesake Henry VIII and we do not know what happened to his body."

A small plaque marks the rough area of his grave but rumours place the exact spot under nearby St. James' School.

Stephen

King Stephen's bones may have been fished out of a ditch and placed in a nearby parish church

King Stephen's bones may have been fished out of a ditch and placed in a nearby parish church After a reign so turbulent it was known as The Anarchy, it is perhaps no surprise Stephen also struggled for peace after his death in 1154. He was buried in a magnificent tomb in the newly constructed Faversham Abbey in Kent but - in what became a pattern - it was demolished on the orders of Henry VIII.

Local historian Jack Long said: "In John Stow's 'Annales' of 1580, he repeats the local legend that the royal tombs were desecrated for the lead coffins and any jewellery that the bodies might have worn, and the bones thrown into the creek.

"(It adds) they were retrieved and reburied in the church of St Mary of Charity in Faversham. There is an annexe (in the church) dating from the period but which has no original markings.

"To the best of my knowledge, no work has ever been undertaken to establish exactly what exists behind or below this mysterious annexe."

Edward V

The mystery and tragedy of the Princes in the Tower has inspired painters and playwrights

The mystery and tragedy of the Princes in the Tower has inspired painters and playwrights Richard III plays a central role in one of the most emotionally charged stories in English history. In April 1483 Edward IV died leaving his 12-year-old son, also called Edward, as heir.

The dying king had appointed his brother, Richard of Gloucester, as the boy's protector. In short order Edward was placed in the Tower of London, had his coronation postponed and was then barred from the throne after his parents' marriage was declared illegitimate. In June Richard was declared king.

Along with his younger brother Richard, Edward was never seen outside the tower again.

In 1674, the skeletons of two children were discovered during building work in the tower and were reburied in Westminster Abbey under the names of the missing children but controversy rages as to who they really were - as well as the true fate of the princes and the identity of any killer.

Oliver Cromwell

The Royalists' revenge on Oliver Cromwell was a spectacular piece of macabre theatre

The Royalists' revenge on Oliver Cromwell was a spectacular piece of macabre theatre Admittedly not a king, but Cromwell was certainly a head of state. And most of him has no grave.

After leading the Parliamentarian forces to victory in the civil war against Charles I, Cromwell took the reins of power until his death in 1658 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

When Charles II came to the throne in 1660, his supporters decided to enact a peculiarly spiteful form of vengeance, exhuming Cromwell's body and hanging it on the scaffold at Tyburn near modern day Marble Arch.

John Goldsmith, curator of the Cromwell Museum in Huntingdon, said: "It was then cut down and beheaded. Despite various stories about it being spirited away, his body was almost certainly dumped in a nearby pit.

"His embalmed head was later removed from a spike and went from owner to owner - including being an attraction in a travelling show - until eventually being reburied at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge in 1960."

James II

James II refused to be buried in the hope his body might return to England

James II refused to be buried in the hope his body might return to England Chased from the throne in 1688 for attempting to restore the absolute monarchy of his father Charles I, James lived in exile in Paris until his death and anatomical dissection in 1701.

He refused burial in the belief he would get his place in Westminster Abbey and the coffin was put in the Chapel of Saint Edmund in the Church of the English Benedictines in the Rue St Jacques.

His brain was sent to the Scots College in Paris and put in a silver case on top of a column, his heart went to the Convent of the Visitandine Nuns at Chaillot and his intestines were divided between the English Church of St Omer and the parish church of St Germain-en-Laye.

Aidan Dodson, author of The Royal Tombs of Great Britain, said: "It all disappeared in the French Revolution of 1789. The mob attacked the churches and his lead coffin was sold for scrap, as was the silver case for his brain.

"The church (of St Germain-en-Laye) was demolished but then rebuilt in 1824 and during this his intestines were found and reinterred - so a bit of him survives."

And one who was just mislaid... Charles I

The temporary loss of Charles I's grave ensured he never received an elaborate monument

The temporary loss of Charles I's grave ensured he never received an elaborate monument After losing the Civil War, Charles's fortunes took a downward turn when he was executed in 1649. He was buried quietly in St George's Chapel, in Windsor Castle, after being denied a place in Westminster Abbey.

Mr Dodson said: "He was put in with Henry VIII and Jane Seymour but the problem was that they forgot where that entire vault was.

"This was also an excuse for Charles II to pocket the money parliament had given him for his dad's new tomb."

Workmen rediscovered the vault by accident in 1813 and found a velvet draped coffin with the missing monarch's name on it. To satisfy their curiosity, a group of notables opened the casket and, sure enough, found a body with a detached head and a pointy beard.

Published on March 18, 2015 08:21

History Trivia - Edward, the Martyr, King of Anglo-Saxons murdered

March 18

235 Emperor Alexander Severus and his mother Julia Mamaea were murdered by legionaries near Moguntiacum (modern Mainz), ending the Severan dynasty.

978 Edward, the Martyr, King of Anglo-Saxons was murdered

1314 Jacques de Molay, the 23rd and the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, was burned at the stake.

235 Emperor Alexander Severus and his mother Julia Mamaea were murdered by legionaries near Moguntiacum (modern Mainz), ending the Severan dynasty.

978 Edward, the Martyr, King of Anglo-Saxons was murdered

1314 Jacques de Molay, the 23rd and the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, was burned at the stake.

Published on March 18, 2015 02:00

March 17, 2015

Saint Patrick, the Apostle of Ireland

Saint Patrick

The stained glass image of St Patrick hails from Cabinteely church, Dublin

The stained glass image of St Patrick hails from Cabinteely church, Dublin

Saint Patrick is the patron saint and national apostle of Ireland. St Patrick is credited with bringing christianity to Ireland. Most of what is known about him comes from his two works; the Confessio, a spiritual autobiography, and his Epistola, a denunciation of British mistreatment of Irish christians.

Saint Patrick is the patron saint and national apostle of Ireland. St Patrick is credited with bringing christianity to Ireland. Most of what is known about him comes from his two works; the Confessio, a spiritual autobiography, and his Epistola, a denunciation of British mistreatment of Irish christians.

According to different versions of his life story it is said that he was born in Britain, around 385AD. His parents Calpurnius and Conchessa were Roman citizens living in either Scotland or Wales. As a boy of 14 he was captured and taken to Ireland where he spent six years in slavery herding sheep. He returned to Ireland in his 30s as a missionary among the Celtic pagans.

Saint Patrick described himself as a “most humble-minded man, pouring forth a continuous paean of thanks to his Maker for having chosen him as the instrument whereby multitudes who had worshipped idols and unclean things had become the people of God.”

Many folk ask the question ‘Why is the Shamrock the National Flower of Ireland ?’ The reason is that St. Patrick used it to explain the Holy Trinity to the pagans. Saint Patrick is believed to have been born in the late fourth century, and is often confused with Palladius, a bishop who was sent by Pope Celestine in 431 to be the first bishop to the Irish believers in Christ.

In the custom known as “drowning the shamrock”, the shamrock that has been worn on a lapel or hat is put in the last drink of the evening.

Saint Patrick is most known for driving the snakes from Ireland. It is true there are no snakes in Ireland, but there probably never have been – the island was separated from the rest of the continent at the end of the Ice Age. As in many old pagan religions, serpent symbols were common and often worshipped. Driving the snakes from Ireland was probably symbolic of putting an end to that pagan practice. While not the first to bring christianity to Ireland, it is Patrick who is said to have encountered the Druids at Tara and abolished their pagan rites. The story holds that he converted the warrior chiefs and princes, baptizing them and thousands of their subjects in the “Holy Wells” that still bear this name.

There are several accounts of Saint Patrick’s death. One says that Patrick died at Saul, Downpatrick, Ireland, on March 17, 460 A.D. His jawbone was preserved in a silver shrine and was often requested in times of childbirth, epileptic fits, and as a preservative against the “evil eye.” Another account says that St. Patrick ended his days at Glastonbury, England and was buried there. The Chapel of St. Patrick still exists as part of Glastonbury Abbey. Today, many Catholic places of worship all around the world are named after St. Patrick, including cathedrals in New York and Dublin city

A toast for St Patrick’s Day, “May the roof above us never fall in, and may we friends beneath it never fall out.”

Saint Patrick’s Day?Saint Patrick’s Day has come to be associated with everything Irish: anything green and gold, shamrocks and luck. Most importantly, to those who celebrate its intended meaning, St. Patrick’s Day is a traditional day for spiritual renewal and offering prayers for missionaries worldwide.

Why is it celebrated on March 17th? One theory is that that is the day that St. Patrick died. Since the holiday began in Ireland, it is believed that as the Irish spread out around the world, they took with them their history and celebrations. The biggest observance of all is, of course, in Ireland. With the exception of restaurants and pubs, almost all businesses close on March 17th. Being a religious holiday as well, many Irish attend mass, where March 17th is the traditional day for offering prayers for missionaries worldwide before the serious celebrating begins.

In American cities with a large Irish population, St. Patrick’s Day is a very big deal. Big cities and small towns alike celebrate with parades, “wearing of the green,” music and songs, Irish food and drink, and activities for kids such as crafts, coloring and games. Some communities even go so far as to dye rivers or streams green!

The stained glass image of St Patrick hails from Cabinteely church, Dublin

The stained glass image of St Patrick hails from Cabinteely church, Dublin Saint Patrick is the patron saint and national apostle of Ireland. St Patrick is credited with bringing christianity to Ireland. Most of what is known about him comes from his two works; the Confessio, a spiritual autobiography, and his Epistola, a denunciation of British mistreatment of Irish christians.

Saint Patrick is the patron saint and national apostle of Ireland. St Patrick is credited with bringing christianity to Ireland. Most of what is known about him comes from his two works; the Confessio, a spiritual autobiography, and his Epistola, a denunciation of British mistreatment of Irish christians.According to different versions of his life story it is said that he was born in Britain, around 385AD. His parents Calpurnius and Conchessa were Roman citizens living in either Scotland or Wales. As a boy of 14 he was captured and taken to Ireland where he spent six years in slavery herding sheep. He returned to Ireland in his 30s as a missionary among the Celtic pagans.

Saint Patrick described himself as a “most humble-minded man, pouring forth a continuous paean of thanks to his Maker for having chosen him as the instrument whereby multitudes who had worshipped idols and unclean things had become the people of God.”

Many folk ask the question ‘Why is the Shamrock the National Flower of Ireland ?’ The reason is that St. Patrick used it to explain the Holy Trinity to the pagans. Saint Patrick is believed to have been born in the late fourth century, and is often confused with Palladius, a bishop who was sent by Pope Celestine in 431 to be the first bishop to the Irish believers in Christ.

In the custom known as “drowning the shamrock”, the shamrock that has been worn on a lapel or hat is put in the last drink of the evening.

Saint Patrick is most known for driving the snakes from Ireland. It is true there are no snakes in Ireland, but there probably never have been – the island was separated from the rest of the continent at the end of the Ice Age. As in many old pagan religions, serpent symbols were common and often worshipped. Driving the snakes from Ireland was probably symbolic of putting an end to that pagan practice. While not the first to bring christianity to Ireland, it is Patrick who is said to have encountered the Druids at Tara and abolished their pagan rites. The story holds that he converted the warrior chiefs and princes, baptizing them and thousands of their subjects in the “Holy Wells” that still bear this name.

There are several accounts of Saint Patrick’s death. One says that Patrick died at Saul, Downpatrick, Ireland, on March 17, 460 A.D. His jawbone was preserved in a silver shrine and was often requested in times of childbirth, epileptic fits, and as a preservative against the “evil eye.” Another account says that St. Patrick ended his days at Glastonbury, England and was buried there. The Chapel of St. Patrick still exists as part of Glastonbury Abbey. Today, many Catholic places of worship all around the world are named after St. Patrick, including cathedrals in New York and Dublin city

A toast for St Patrick’s Day, “May the roof above us never fall in, and may we friends beneath it never fall out.”

Saint Patrick’s Day?Saint Patrick’s Day has come to be associated with everything Irish: anything green and gold, shamrocks and luck. Most importantly, to those who celebrate its intended meaning, St. Patrick’s Day is a traditional day for spiritual renewal and offering prayers for missionaries worldwide.

Why is it celebrated on March 17th? One theory is that that is the day that St. Patrick died. Since the holiday began in Ireland, it is believed that as the Irish spread out around the world, they took with them their history and celebrations. The biggest observance of all is, of course, in Ireland. With the exception of restaurants and pubs, almost all businesses close on March 17th. Being a religious holiday as well, many Irish attend mass, where March 17th is the traditional day for offering prayers for missionaries worldwide before the serious celebrating begins.

In American cities with a large Irish population, St. Patrick’s Day is a very big deal. Big cities and small towns alike celebrate with parades, “wearing of the green,” music and songs, Irish food and drink, and activities for kids such as crafts, coloring and games. Some communities even go so far as to dye rivers or streams green!

Published on March 17, 2015 06:05

The dangerous streets of ancient Rome

Emma McFarnonHistory Extra

A fresco painting of game players in a tavern on the Via di Mercurio in Pompeii. (Corbis)

A fresco painting of game players in a tavern on the Via di Mercurio in Pompeii. (Corbis)

Ancient Rome after dark was a dangerous place. Most of us can easily imagine the bright shining marble spaces of the imperial city on a sunny day – that’s usually what movies and novels show us, not to mention the history books. But what happened when night fell? More to the point, what happened for the vast majority of the population of Rome, who lived in the over-crowded high-rise garrets, not in the spacious mansions of the rich?

Remember that, by the first century BC, the time of Julius Caesar, ancient Rome was a city of a million inhabitants – rich and poor, slaves and ex-slaves, free and foreign. It was the world’s first multicultural metropolis, complete with slums, multiple-occupancy tenements and sink estates – all of which we tend to forget when we concentrate on its great colonnades and plazas. So what was backstreet Rome – the real city – like after the lights went out? Can we possibly recapture it?

The best place to start is the satire of that grumpy old Roman man, Juvenal, who conjured up a nasty picture of daily life in Rome around AD 100. The inspiration behind every satirist from Dr Johnson to Stephen Fry, Juvenal reminds us of the dangers of walking around the streets after dark: the waste (that is, chamber pot plus contents) that might come down on your head from the upper floors; not to mention the toffs (the blokes in scarlet cloaks, with their whole retinue of hangers on) who might bump into you on your way through town, and rudely push you out of the way:

“And now think of the different and diverse perils of the night. See what a height it is to that towering roof from which a pot comes crack upon my head every time that some broken or leaky vessel is pitched out of the window! See with what a smash it strikes and dints the pavement! There’s death in every open window as you pass along at night; you may well be deemed a fool, improvident of sudden accident, if you go out to dinner without having made your will… Yet however reckless the fellow may be, however hot with wine and young blood, he gives a wide berth to one whose scarlet cloak and long retinue of attendants, with torches and brass lamps in their hands, bid him keep his distance. But to me, who am wont to be escorted home by the moon, or by the scant light of a candle he pays no respect.” (Juvenal /Satire/ 3)

Juvenal himself was actually pretty rich. All Roman poets were relatively well heeled (the leisure you needed for writing poetry required money, even if you pretended to be poor). His self-presentation as a ‘man of the people’ was a bit of a journalistic facade. But how accurate was his nightmare vision of Rome at night? Was it really a place where chamber pots crashed on your head, the rich and powerful stamped all over you, and where (as Juvenal observes elsewhere) you risked being mugged and robbed by any group of thugs that came along?

Probably yes.

Outside the splendid civic centre, Rome was a place of narrow alleyways, a labyrinth of lanes and passageways. There was no street lighting, nowhere to throw your excrement and no police force. After dark, ancient Rome must have been a threatening place. Most rich people, I’m sure, didn’t go out – at least, not without their private security team of slaves or their “long retinue of attendants” – and the only public protection you could hope for was the paramilitary force of the night watch, the vigiles.

Exactly what these watchmen did, and how effective they were, is a moot point. They were split into battalions across the city and their main job was to look out for fires breaking out (a frequent occurrence in the jerry-built tenement blocks, with open braziers burning on the top floors). But they had little equipment to deal with a major outbreak, beyond a small supply of vinegar and a few blankets to douse the flames, and poles to pull down neighbouring buildings to make a fire break.

Part of the Palatine Hill, one of the most ancient areas of the city. (Bridgeman Art Library)

While Rome burnedSometimes these men were heroes. In fact, a touching memorial survives to a soldier, acting as a night watchman at Ostia, Rome’s port. He had tried to rescue people stranded in a fire, had died in the process and was given a burial at public expense. But they weren’t always so altruistic. In the great fire of Rome in AD 64 one story was that the vigiles actually joined in the looting of the city while it burned. The firemen had inside knowledge of where to go and where the rich pickings were.

Certainly the vigiles were not a police force, and had little authority when petty crimes at night escalated into something much bigger. They might well give a young offender a clip round the ear. But did they do more than that? There wasn’t much they could do, and mostly they weren’t around anyway.

If you were a crime victim, it was a matter of self-help – as one particularly tricky case discussed in an ancient handbook on Roman law proves. The case concerns a shop-keeper who kept his business open at night and left a lamp on the counter, which faced onto the street. A man came down the street and pinched the lamp, and the man in the shop went after him, and a brawl ensued. The thief was carrying a weapon – a piece of rope with a lump of metal at the end – and he coshed the shop-keeper, who retaliated and knocked out the eye of the thief.

This presented Roman lawyers with a tricky question: was the shopkeeper liable for the injury? In a debate that echoes some of our own dilemmas about how far a property owner should go in defending himself against a burglar, they decided that, as the thief had been armed with a nasty piece of metal and had struck the first blow, he had to take responsibility for the loss of his eye.

But, wherever the buck stopped (and not many cases like this would ever have come to court, except in the imagination of some academic Roman lawyers), the incident is a good example for us of what could happen to you on the streets of Rome after dark, where petty crime could soon turn into a brawl that left someone half-blind.

And it wasn’t just in Rome itself. One case, from a town on the west coast of modern Turkey, at the turn of the first centuries BC and AD, came to the attention of the emperor Augustus himself. There had been a series of night-time scuffles between some wealthy householders and a gang that was attacking their house (whether they were some young thugs who deserved the ancient equivalent of an ASBO, or a group of political rivals trying to unsettle their enemies, we have no clue). Finally, one of the slaves inside the house, who was presumably trying to empty a pile of excrement from a chamber pot onto the head of a marauder, actually let the pot fall – and the result was that the marauder was mortally injured.

The case, and question of where guilt for the death lay, was obviously so tricky that it went all the way up to the emperor himself, who decided (presumably on ‘self-defence’ grounds) to exonerate the householders under attack. And it was presumably those householders who had the emperor’s judgment inscribed on stone and put on display back home. But, for all the slightly puzzling details of the case, it’s another nice illustration that the streets of the Roman world could be dangerous after dark; and that Juvenal might not have been wrong about those falling chamber pots.

But night-time Rome wasn’t just dangerous. There was also fun to be had in the clubs, taverns and bars late at night. You might live in a cramped flat in a high-rise block, but, for men at least, there were places to go to drink, to gamble and (let’s be honest) to flirt with the barmaids.

The remains of a tavern in the Roman port town of Ostia. (Copyright Alamy)

The Roman elite were pretty sniffy about these places. Gambling was a favourite activity right through Roman society. The emperor Claudius was even said to have written a handbook on the subject. But, of course, this didn’t prevent the upper classes decrying the bad habits of the poor, and their addiction to games of chance. One snobbish Roman writer even complained about the nasty snorting noises that you would hear late at night in a Roman bar – the noises that came from a combination of snotty noses and intense concentration on the board game in question.

Happily, though, we do have a few glimpses into the fun of the Roman bar from the point of view of the ordinary users themselves. That is, we can still see some of the paintings that decorated the walls of the ordinary, slightly seedy bars of Pompeii – showing typical scenes of bar life. These focus on the pleasures of drink (we see groups of men sitting around bar tables, ordering another round from the waitress), we see flirtation (and more) going on between customers and barmaids, and we see a good deal of board gaming.

Interestingly, even from this bottom-up perspective, there is a hint of violence. In the paintings from one Pompeian bar (now in the Archaeological Museum at Naples), the final scene in a series shows a couple of gamblers having a row over the game, and the landlord being reduced to threatening to throw his customers out. In a speech bubble coming out of the landlord’s mouth, he is saying (as landlords always have) “Look, if you want a fight, guys, get outside”.

So where were the rich when this edgy night life was going on in the streets? Well most of them were comfortably tucked up in their beds, in their plush houses, guarded by slaves and guard dogs. Those mosaics in the forecourts of the houses of Pompeii, showing fierce canines and branded Cave Canem (‘Beware of the Dog’), are probably a good guide to what you would have found greeting you if you had tried to get into one of these places.

Inside the doors, peace reigned (unless the place was being attacked of course!), and the rough life of the streets was barely audible. But there is an irony here. Perhaps it isn’t surprising that some of the Roman rich, who ought to have been tucked up in bed in their mansions, thought that the life of the street was extremely exciting in comparison. And – never mind all those snobbish sneers about the snorting of the bar gamblers – that’s exactly where they wanted to be.

A man refills his cup from a wine cask in this first-century AD Roman relief. (akg-images)

Rome’s mean streets were where you could apparently find the Emperor Nero on his evenings off. After dark, so his biographer Suetonius tells us, he would disguise himself with a cap and wig, visit the city bars and roam around the streets, running riot with his mates. When he met men making their way home after dinner, he’d beat them up; he’d even break into closed shops, steal some of the stock and sell it in the palace. He would get into brawls – and apparently often ran the risk of having an eye put out (like the thief with the lamp), or even of ending up dead.

So while many of the city’s richest residents would have avoided the streets of Rome after dark at all costs – or only ventured onto them accompanied by their security guard – others would not just be pushing innocent pedestrians out of the way, they’d be prowling around, giving a very good pretence of being muggers. And, if Suetonius is to be believed, the last person you’d want to bump into late at night in downtown Rome would be the Emperor Nero.

A fresco painting of game players in a tavern on the Via di Mercurio in Pompeii. (Corbis)

A fresco painting of game players in a tavern on the Via di Mercurio in Pompeii. (Corbis) Ancient Rome after dark was a dangerous place. Most of us can easily imagine the bright shining marble spaces of the imperial city on a sunny day – that’s usually what movies and novels show us, not to mention the history books. But what happened when night fell? More to the point, what happened for the vast majority of the population of Rome, who lived in the over-crowded high-rise garrets, not in the spacious mansions of the rich?

Remember that, by the first century BC, the time of Julius Caesar, ancient Rome was a city of a million inhabitants – rich and poor, slaves and ex-slaves, free and foreign. It was the world’s first multicultural metropolis, complete with slums, multiple-occupancy tenements and sink estates – all of which we tend to forget when we concentrate on its great colonnades and plazas. So what was backstreet Rome – the real city – like after the lights went out? Can we possibly recapture it?

The best place to start is the satire of that grumpy old Roman man, Juvenal, who conjured up a nasty picture of daily life in Rome around AD 100. The inspiration behind every satirist from Dr Johnson to Stephen Fry, Juvenal reminds us of the dangers of walking around the streets after dark: the waste (that is, chamber pot plus contents) that might come down on your head from the upper floors; not to mention the toffs (the blokes in scarlet cloaks, with their whole retinue of hangers on) who might bump into you on your way through town, and rudely push you out of the way:

“And now think of the different and diverse perils of the night. See what a height it is to that towering roof from which a pot comes crack upon my head every time that some broken or leaky vessel is pitched out of the window! See with what a smash it strikes and dints the pavement! There’s death in every open window as you pass along at night; you may well be deemed a fool, improvident of sudden accident, if you go out to dinner without having made your will… Yet however reckless the fellow may be, however hot with wine and young blood, he gives a wide berth to one whose scarlet cloak and long retinue of attendants, with torches and brass lamps in their hands, bid him keep his distance. But to me, who am wont to be escorted home by the moon, or by the scant light of a candle he pays no respect.” (Juvenal /Satire/ 3)

Juvenal himself was actually pretty rich. All Roman poets were relatively well heeled (the leisure you needed for writing poetry required money, even if you pretended to be poor). His self-presentation as a ‘man of the people’ was a bit of a journalistic facade. But how accurate was his nightmare vision of Rome at night? Was it really a place where chamber pots crashed on your head, the rich and powerful stamped all over you, and where (as Juvenal observes elsewhere) you risked being mugged and robbed by any group of thugs that came along?

Probably yes.

Outside the splendid civic centre, Rome was a place of narrow alleyways, a labyrinth of lanes and passageways. There was no street lighting, nowhere to throw your excrement and no police force. After dark, ancient Rome must have been a threatening place. Most rich people, I’m sure, didn’t go out – at least, not without their private security team of slaves or their “long retinue of attendants” – and the only public protection you could hope for was the paramilitary force of the night watch, the vigiles.

Exactly what these watchmen did, and how effective they were, is a moot point. They were split into battalions across the city and their main job was to look out for fires breaking out (a frequent occurrence in the jerry-built tenement blocks, with open braziers burning on the top floors). But they had little equipment to deal with a major outbreak, beyond a small supply of vinegar and a few blankets to douse the flames, and poles to pull down neighbouring buildings to make a fire break.

Part of the Palatine Hill, one of the most ancient areas of the city. (Bridgeman Art Library)