Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 326

October 9, 2015

LCD Soundsystem and the Mythical Death of Indie

In 2011, LCD Soundsystem took the notion of quitting while you’re ahead to a joyful, lucrative extreme. A mere 10 years into an influential career that was still on an upward trajectory, on the occasion of no scandal or tragedy or big fight, James Murphy’s art-disco rockers chose to break up—and memorialized the event in a Madison Square Garden “funeral” concert that also became a five-disk box set, a record-store exhibition, and a feature documentary.

At the time, people joked that they were doing this all to reap the profits that would come from a reunion tour a few years later. And lo, on Thursday, Consequence of Sound reported that sources in the music industry say LCD Soundsystem will play at least three music festivals on 2016. Billboard then published confirmation from an anonymous source of its own.

But as quickly as the news triggered a social-media storm of crying-with-joy emojis and references to the band’s third album title, This Is Happening, Kris Petersen of Murphy’s label DFA tweeted that it was all a lie. “LCD Soundsystem are not reuniting next year, you fucking morons,” he wrote. Consequence of Sound’s Alex Young held his ground, though: “I’ve been working the LCD Soundsystem story for a month. It’s happening.”

And here it was, the last time people argued about indie rock.

Okay, that’s not true. But the confusion does put a fine point on how times have changed in four years; the truth is, with the way music is now, there probably is real, pervasive nostalgia that LCD Soundsystem could cash in on. In fact, you could argue that the 2011 Madison Square Garden show is as good a marker as any for the end the era when “indie rock” was a term with any cultural significance. Cultural is the key word there—“indie” has long been more of a social description than a musical or economic one, though it originally referred to a truly countercultural movement that predated the Internet. When I use it here, I’m talking about the parade of aughts bands feted by Pitchfork, selling out venues, and making a musical canon that served as a plausibly vibrant alternative to the mainstream.

Defining golden eras and genre trends is always messy, limited, inevitably silly. Plenty of standard-bearers—Arcade Fire, Animal Collective—are still working; plenty of underground and alternative scenes thriving right now; a few newish acts, like Tame Impala or Haim, successfully fit the old definition. But Google “indie rock is dead” and you come up with a slew of think pieces in the last five or six years with that headline: Just today, The Fader published a Q&A between the Vampire Weekend singer Ezra Koenig and Carles, the blogger behind Hipster Runoff, that takes for given that their subculture has died. If it ever lived, that is: “Indie never existed,” Carles says. “What people believe ‘sounds’ like indie still lives on in the fringes of Bandcamps, content farms of yesteryear, and in the hearts of regretful thirtysomethings.”

Parsing exactly what has changed is tough. Maybe it's the way that streaming has made obsolete many record-collector’s cravings as well as the need for distribution channels separate from mainstream ones. Maybe there’s a gender and race dynamic going on; the artists with the highest name-recognition-to-innovation quota now are those like FKA Twigs and Grimes, women who received attention from indie-rock tastemakers but draw on very different traditions. And maybe it’s the rise of “poptimism”—the phenomenon that allows “cool” people to enjoy Beyonce and Taylor Swift.

“The world has spoken, and it prefers genuine fakes to fake genuines,” Ezra Koenig says. “Mid-2000s indie was full of fake genuines.”To hear LCD’s camp tell it, it’s all of these things and more. Days before he took to Twitter to deny the reunion, DFA’s Petersen had written there, “How come the minute I start working in music everyone stops being elitist and snarky and starts liking pop bullshit :(.” And in a follow-up interview with the Village Voice, he observed that it’s plenty plausible that major festivals offered lots of money for an LCD Soundsystem reunion, simply because there aren’t many acts of that band’s tier active at the moment. It also sounded like DFA—one of the most influential labels of the new millennium, having released albums by the likes of Hot Chip, Hercules and Love Affair, and The Rapture—was facing struggles. “I sort of have the understanding that [LCD Soundsystem is] probably going to be the biggest band that comes off this label,” he said, “not because they’re so special, but because there’s no music industry anymore.

In the Fader interview, Koenig made among the more perceptive comments anyone has made about how music culture seems to be changing:

The amateur/professional dichotomy is just about destroyed now. The biggest celebrities now show the openness/vulnerability/‘realness’ that was once associated with ‘confessional’ ‘bedroom’ indie. The smallest artists now rely on big corporate money to get started. All the old dualities are jumbled.

He added, “The world has spoken, and it prefers genuine fakes to fake genuines. Mid-2000s indie was full of fake genuines. I won’t name names.”

LCD Soundsystem's James Murphy might or might not be on that list of names. His band approached modern culture and music history with a mix of ironic poise and seemingly sincere emotion; one of their most famous singles, “Losing My Edge,” offered a half-joking rant from an aging scenester threatened by kids with their “borrowed nostalgia for the unremembered ‘80s.” Were LCD Soundsystem to come back now, they’d be reaping those same kids’ nostalgia, but for a time they remember, a time that seems farther in the past than it really is.

An Iranian General Is Killed in Syria

In May 2014, Hossein Hamedani, a top general in Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, made a statement at a council meeting in Hamedan, the western Iranian province.

“Today we fight in Syria for interests such as the Islamic Revolution,” he said, adding, “Our defense is to the extent of the Sacred Defense”— a reference to Iran’s eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s.

FARS, Iran’s state-run news agency, later struck his remarks from their account of the meeting because it contradicted Tehran’s official line—Iran is not militarily involved in the five-year-old Syrian civil war. As Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty noted, Hamedani’s boasts that Iran had created “a second Hezbollah” and that Iran’s efforts meant the Assad regime in Syria was no longer “at the risk of collapse” were also removed.

On Friday, Iran announced Hamedani had been killed this week in Syria in an ISIS attack. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, the general and some of his bodyguards were killed outside a military airport near Aleppo.

President Hassan Rouhani praised Hamedani as a “martyr” and said his death was a “big loss.”

The New York Times reported that Hamedani’s “death illustrated both the level of Iran’s direct involvement on the government side in the Syrian civil war, and the pervasive violence of the conflict.”

Even as Iran has denied it, the country’s level of involvement in the Syrian civil war has always been substantial. However, as the Assad regime has continued to lose its grip on territory and control, the Iranians have scaled up their presence to bolster the Syrian leader. Just last week, The Wall Street Journal noted Iran’s latest major expansion of troops, which was being coordinated with Russia’s launching of airstrikes in Syria, and an offensive by Bashar al-Assad’s forces.

The costs of Iran’s involvement in Syria are also increasing. The news of Hamedani’s death dovetails with a statement by U.S. Defense Secretary Ash Carter confirming reports that four cruise missiles fired by Russia from the Caspian Sea had errantly landed in Iran. Russian media have dismissed that claim.

Pan Is the Peter Pan Prequel No One Asked For

Have you ever wondered where the pixie dust in Peter Pan came from, or what its scientific name is? Just how the institutional hierarchies of fairies, native tribes and lost boys break down? How the pirate infrastructure Captain Hook would later commandeer was set up? Where Hook came from, or Smee, for that matter? It’s hard to imagine anyone being so curious, more than 100 years after J. M. Barrie’s play debuted, but nevertheless, Pan is here—a big-budget, garish mess of a blockbuster that answers questions about the Peter Pan universe nobody asked.

Related Story

Peter Pan Live Was Never Intended to Be Enjoyed

In Pan, Peter (Levi Miller) first visits Neverland after he’s spirited away by orphan-snatching pirates during World War II (never mind that Barrie’s original story was set at the turn of the century). In this timeline, the kingdom is governed by the dread pirate Blackbeard (Hugh Jackman), who steals children to mine pixie dust (or “pixum”) to grant him eternal youth, while he fights an endless war with Neverland’s native peoples, led by Tiger Lily (played by the decidedly white Rooney Mara). Peter meets the dashing young James Hook (Garrett Hedlund) and inspires a rebellion, but Pan’s plot quickly disintegrates as the director Joe Wright stages one bombastic set-piece after another with very little grasp on the story he’s trying to tell.

The film’s problems certainly begin with its script (by Jason Fuchs, whose only other major writing credit thus far is the fourth Ice Age movie): Pan falls into every prequel pitfall possible. It saddles Peter Pan, the archetypal boy who could never grow up, with a plodding Harry Potter-esque origin story in which he’s the chosen one, some mythic offspring of a fairy prince and a native warrior who bears a magical pan-flute totem and thus has the ability to fly. It invents a new villain—Blackbeard—but then spends endless time on exposition about his tragic past and motivations that would require a whole other prequel to get into.

If Pan’s screenplay is a lesson in anything, it’s that most beloved stories don’t require a whole cinematic universe to go along with them. Captain Hook is Peter Pan’s enemy because he cut his hand off—simple. Do we really need a whole movie where they’re allies, but keep making winking references to their future enmity for the audience’s sake? The film uselessly embellishes the stories imagined by Barrie more than 100 years ago and cemented by Walt Disney: This time the pirate ships can fly, model/actress Cara Delevingne plays all three sultry mermaids, and Tiger Lily’s people are rendered as a colorful, multi-ethnic tribe with no distinguishing features who explode into colorful dust when killed.

Wright is an unabashedly visual director who’s worked wonders with much lower-budget projects in the past. He made his Hollywood entry with his rather sumptuous take on Pride & Prejudice, then stuffed his follow-up, Atonement, with long tracking shots to take in the epic sweep of the evacuation of Dunkirk. In his 2012 adaptation of Anna Karenina, made for less than a third of Pan’s $150 million budget, he pulled the dazzling trick of pitching the Russian court as a giant stage show, with intrigue happening behind the scenes; when Levin journeyed to the countryside, the stage was suddenly blasted open into widescreen splendor, a brilliant trick of cinema.

With Pan, he has all the money in the world and too many ideas of what to do with it. Pirate ships careen and loop-de-loop in the air, shooting cannons at the Luftwaffe, blasting by giant, inexplicable spheres of water containing fish and crocodiles. Every character is costumed to the nines, and Blackbeard is given one bombastic speech after another (the film also infuriatingly copies Moulin Rouge’s idea of having a horde singing incongruously along to Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit”). But the heavy use of green-screen in every epic setting is too easily detected, and a final showdown in the kingdom of the fairies, a land of irregular crystalline structures, is disappointingly flat.

It doesn’t help that every actor involved seems completely lost at sea. Mara, perhaps embarrassed at playing a Native American princess clad in a midriff-baring rainbow outfit, barely registers onscreen, dimly smiling at Captain Hook’s lame efforts to flirt with her. Hedlund barks lines in the most exaggerated accent imaginable, doing a Douglas Fairbanks routine by way of Neptune, a performance so unconvincing I mistakenly assumed Hedlund had to be from another country (he is, in fact, Minnesotan). Jackman gives a more comfortably bad turn, the kind of over-the-top vaudeville routine he can do in his sleep. And as Peter, Levi Miller delivers all his lines as if he’s starring in a toy commercial.

Pan was intended as the first salvo in a new series (Pan 2 is already marked on IMDb as being in development, and would probably have dealt with the origins of Hook’s villainy), but that will likely change if its low box-office predictions hold. Instead, let it stand as a totem of Hollywood’s epic franchise folly, a reminder that just because audiences enjoy a classic media property doesn’t mean they need a CGI-laden cinematic universe about it. We can only hope that its failure will throw producers off that scent—at least until the next abominable idea.

The Hajj Stampede: Twice as Bad as the Saudis Said

The death toll in last month’s Hajj stampede in Saudi Arabia is roughly double the number that the country first reported, the Associated Press is reporting.

The Saudi estimate of the disaster was 769, but the new estimate, based on an AP count, suggests that 1,453 people died in the stampede. This new number would make it the deadliest catastrophe in the history of the event.

The Hajj draws roughly 2 million pilgrims to Mecca each year, an observance that lends its host, Saudi Arabia, unrivaled prestige across the Muslim world. It also saddles the kingdom with billions of dollars of costs and logistical considerations. Over the course of the past 40 years, several of the pilgrimages have been marred by deaths caused from stampedes, the collapse of infrastructure, violence, and fires.

Noting Saudi Arabia’s ongoing struggles with low global oil prices, the civil war in neighboring Yemen, and the (continuing) threat of a domestic insurgency, the AP report suggests the country is more overextended and vulnerable than usual:

Any disaster at the hajj, a pillar of Islamic faith, could be seen as a blow to the kingdom's cherished stewardship of Islam's holiest sites. This season saw two, including the Sept. 11 collapse of a crane at Mecca's Grand Mosque that killed 111 people.

Indeed, Shiite Iran in particular has challenged its Sunni arch-rival’s status as the custodian of Islam’s two holiest sites, warning that if diplomacy doesn’t yield an independent investigation, “the Islamic Republic is also prepared to use the language of force.” Nearly one-third of the deaths in the incident were pilgrims from neighboring Iran.

Given all of this, it’s not terribly surprising that a more accurate accounting of the tragedy had to come from an outside source. As Ruth Graham noted last month in The Atlantic, Saudi officials weren’t eager to take responsibility: “In Saudi Arabia, the country’s health minister chalked up the latest incident to a failure to follow instructions, and the head of the Central Hajj Committee blamed ‘some pilgrims from African nationalities.’”

In the meantime, hundreds of worshipers still remain missing and so the true extent of last month’s disaster is not fully known.

When Prison Is a Game

The first person to die in an electric chair was William Kemmler, a peddler from Philadelphia who murdered his common-law wife in the summer of 1890. 1000 volts of electricity, tested the day before on a luckless horse, knocked Kemmler unconscious, but didn’t stop his heart. In a panic, the warden doubled the voltage. 2000 volts of alternating current ruptured Kemmler’s capillaries, forming subcutaneous pools of blood that began to burst as his skin was torn apart. Witnesses reported being overcome by the smell of molten flesh and charred body hair; those who tried to leave found that the doors were locked. The next morning, The New York Times called the execution a “disgrace to civilization … so terrible that words cannot begin to describe it.” The irony, lost on no one, was that until that morning, electrocution had been promoted as a more humane form of capital punishment.

MORE FROM KILL SCREEN Why the Game About Prison Management Could Be the Most Devastating Title of 2013 Want To Learn About Game Design? Go to IKEA The Game Design of Everyday Things: To Shape the Future

Prison Architect, Introversion Software’s long-awaited incarceration simulator, begins by asking the player to construct an electric chair. A milquetoast, Walter White-type has murdered his wife and her lover, and you, the architect, must carry out his punishment. It’s a disorienting anachronism. The electric chair, its fatal technique refined and its debut hastily forgotten, ruled capital punishment for nearly 75 years, but a series of botched executions in the 1960s sparked a Supreme Court case that led to its effective retirement.

At first, the historically anomaly is odd. Prison Architect, after all, has been marketed and developed as one (British) studio’s take on the contemporary (American) prison-industrial complex. Yet this oddity quickly comes to represent Prison Architect’s relationship to its subject matter: For all of Introversion’s developer diaries about their sensitivity to the minutiae of the penal system, Prison Architect isn’t shy about its distortions and oversights, necessary sacrifices on the thirsty altar of “fun.”

That’s not necessarily a criticism. There are good reasons to choose the electric chair and its symbolic capital over its less spectacular successor, lethal injection. But the reasons betray Introversion’s intentions: The game comes first, everything else, last. And Prison Architect, to be sure, is an excellent game, worthy of comparison to its canonical inspirations, Dwarf Fortress and Bullfrog Productions’ 1990 construct-and-manage simulations. Few games can hope to match Prison Architect’s emergent storytelling, and fewer still can balance brutality and poignancy like it does.

Introversion has been transparent about its desire for Prison Architect to provoke reflection about the American prison-industrial complex, and to do so in a way that does not exploit the suffering of those caught behind its jaws of steel. And, to a degree, Prison Architect achieves this goal. Whereas Valusoft’s lamentable Prison Tycoon series gleefully exploited mass incarceration as a vaguely subversive veneer for its shoddy simulations, Prison Architect genuinely attempts to model the systems that, together, comprise the complex ethnology that is the 21st-century American prison. Particularly admirable is Prison Architect’s sensitivity to how incarceration can exacerbate or ameliorate the interlocking problems of drug addiction and alcoholism (in 2002, 68 percent of inmates suffered from substance dependency), lack of education (roughly half of inmates are functionally illiterate), and recidivism (more than 60 percent of released prisoners will return to prison within three years).

At the same time, however, the distortions Prison Architect makes—escapes are constant, riots are quotidian, and, above all, race is virtually devoid of meaning—betray Introversion’s prime directive: the pleasure of the player. No simulation can, of course, perfectly represent its subject, and so verisimilitude is a poor basis for judging Prison Architect as a simulation. The trouble arises when viewing Prison Architect as anything other than a particularly captivating and colorful ant farm—which is exactly what Introversion wants its players to do.

* * *

The modern prison began to take shape in the 18th century, when social discontent with public torture, executions, and arbitrary acts of violence by the state began to lose their force as instruments of social control. In their place rose new, “gentler” technologies of discipline. Yet reformists, as the philosopher Michel Foucault argues in Discipline and Punish, were concerned with the fact that punishment was administered haphazardly, not the administering of punishment itself. Prisons, first in the form of chain gangs (“public, punitive labor”) and then as discrete institutions, emerged from a desire, in Foucault’s memorable phrase, “to punish less, perhaps, but certainly to punish better.” Though the methods might change, the motivations don’t. Recall the case of the electric chair, whose demise was secured by the invention of lethal injection, which was not merely more humane, but also more effective.

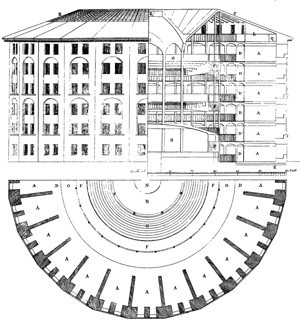

In Foucault’s view, the prison has become the linchpin in a “carceral system” of social control through various, normalizing institutions, especially public education (standardized testing), factories (standardized labor), hospitals (standardized treatment), and the law (standardized judgment). Above all, their purpose is to generate disciplined, docile bodies appropriate for neoliberal economies. Nowhere is this conclusion more clear than in the disturbingly similar architectural conventions for these institutions: Their sober, utilitarian appearance obscures their role in the maintenance of social, cultural, and political power. This type of architecture was exemplified in the unequal gaze of Jeremy Bentham’s imaginary prison, the Panopticon: a building that makes every inmate visible to a single guard, but invisible to every other inmate.

Jeremy Bentham / Wikimedia

Jeremy Bentham / Wikimedia Understanding architecture, in other words, is a crucial for understanding prisons. Leon Battista Alberti, the Renaissance’s most celebrated art theorist, wrote a treatise on prison design, while the engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi is best remembered for his carceri d’invenzione (imaginary prisons), a series of Kafkaesque penal vaults. Prison Architect might belong in this long tradition of real and imaginary prison design were it not for the puzzling fact that architecture is nearly absent from the game. Yes, much of the player’s time is spent planning and erecting new cell blocks, facilities, and fences. But Prison Architect never asks its players to think outside of two dimensions, minus subterranean escape tunnels.

If this seems like a capricious line of criticism, consider this: In the 1970s and 1980s, as the focus of incarceration shifted from rehabilitation to retribution, prison architecture was altered in stride. The monumental (vertical and horizontal) size of new prisons served not only to house a rapidly growing population, but to annihilate any sense of human scale. Case in point: The Colorado prison ADX Florence, the pinnacle of late-20th century American prison design, uses architecture to disorient, isolate, and overpower its inmates. Its window slits—four inches by four feet—prevent inmates from orienting themselves in space; the exercise pit (walled on all sides, again, to prevent orientation) is sized to restrict natural movement. It is, in a former warden’s words, “a cleaner version of hell.”

What incarceration manages, in other words, is not simply its inmates’ bodies, but also their consciousnesses. Prison walls entrap subjectivities as much as they corral physical beings. Prison Architect might not actually be about architecture in any meaningful sense, but it is certainly about systems of control over the physical and mental lives of prisoners. By manipulating prisoners’ schedules, workflows, movements, diets, and cells, what the player really controls is the limits of inmates’ experience. The prison architect of Prison Architect’s material is the immaterial: You are the system, complicit in every present link of the carceral site, from brick to batons to body bags.

Introversion Software

Introversion Software This is the most valuable insight that Prison Architect offers: a chance to resist the solipsism of personal identification and plunge into the systems that structure the experiences of incarceration. From this perspective, Prison Architect takes full advantage of its medium, forging an operable argument that persuades the player that prisons are deeply complex sites of power and misery, and that there are no one-dimensional solutions to the multi-dimensional problems they constitute and are constituted by. Yes, we learn little of individual inmates’ experience, but we come away understanding how their lives are constituted through experience. The shift is subtle, but profound. From militarized, for-profit hells where bodies are made docile at gunpoint to models of rehabilitation that aim for reintegration rather than further exclusion, Prison Architect reminds us that the architects of the systems we participate in are just that: architects. And anything built can be destroyed, or so the logic goes.

But the problem with this sort of praise, and, perhaps, this model of game design, is that when everything is “systems,” it’s easy to forget why identity and identification matter in the first place. It’s true that the conditions of our lives are produced by the systems we are embedded in. Yet no one experiences life as a system. Rather, we live as actors in these systems. And to make systems the exclusive locus of inquiry runs the risk of crushing individual experience, the only kind we can ever truly know. To its credit, Prison Architect attempts to keep sight of the individual through its narrative tutorials, which revolve around particular prisoner’s experiences in prison as a counterweight to its alienating simulation. Yet the gesture comes off as a small consolation, tagged on at the end of the game’s development (and indeed, “story mode” is among the most recent additions to the game).

You are the system, complicit in every present link of the carceral site, from brick to batons to body bags.The other purpose of these micro-narratives is to remind the player, however poorly, that although the prison might be a system with its own internal logic, it is just one node in a larger system that contains legislation, lobbyists, policy, post-industrial urbanism, and any other number of actors that make up the rhizomatic grasp of the prison-industrial complex. Remember Foucault: The prison is not simply a site, but an idea built about discipline and punishment built long before the cornerstone is laid.

Prison Architect alludes towards the forces beyond the prison that themselves construct the prison through a weak, narrative variation on the “Kids for Cash” scandal. Yet the gesture is hopelessly superficial and utterly absent from any meaningful mechanics. The prisons of Prison Architect are essentially hermetic systems: The complex ethnology rarely reaches beyond the prison’s walls. For an argument about the nature of contemporary American prisons, this is a glaring defect. For real prisons, though, it’s better understood as a feature. One reason prisons are often constructed in rural areas is that it obscures their relationship to the other actors in the judicial system (consider: Many European prisons are contained within the same building as the courtroom). The prison, isolated in space, becomes an ontology. Crime, discipline, and punishment are axiomatic, and thus, impossible to contest.

* * *

Every simulation, of course, is a simplification of the real-world system it models. The issue with Prison Architect is not that it fails to represent every aspect of prisons’ complexity, but that the aspects it omits are among the most important for understanding why and how mass incarceration is the way it is. Perhaps this makes for a better game, but it’s ludicrous to pretend that it makes for a worthwhile study of the 21st-century American prison, which has much more to do with decades of punishing state and federal policies on incarceration than the variety of meals inmates are offered. At their worst, Prison Architect’s simplifications exclude the identities and histories that have been swallowed up by the grey, carceral wastes of America.

Introversion Software

Introversion Software Nowhere is the cost of Prison Architect’s exclusions more palpable than in the game’s treatment, or lack thereof, of race. It’s hardly controversial to say that racism is inseparable from the prison-industrial complex, which makes race’s near-total absence from Prison Architect both bewildering and insidious. In a recent article for The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates persuasively argues that the American prison-industrial complex constitutes the latest technology in a long history of structuralist white supremacy. “Peril,” Coates writes, “is generational for black people in America—and incarceration is [America’s] mechanism for maintaining that peril.”

Although mass incarceration has touched virtually every community in the United States (if our prison population were counted as a single city, it would be the fourth largest in the country), its worst injustices have been disproportionately borne by black Americans: One in four black men born since 1970 has experienced prison firsthand. Black murderers whose victims were white are 10 times more likely to receive the death penalty than white murderers whose victims were black.

But in Prison Architect, race matters only insofar as it can (sometimes) determine the gang affiliation of a particular inmate. And while Introversion’s commitment to representing a diverse prison population (of both staff and inmates) is commendable, the studio’s unwillingness to model race as part of a larger system, even as it models so many other systems in the prison-industrial complex, is perplexing. Inclusion is better than exclusion, yes, but inclusion for its own sake is a hollow gesture. If Prison Architect allows would-be wardens to offer programs for drug and alcohol rehabilitation, why not programs designed to foster cultural healing? At least some of the racial tension in American prisons is derived from the fact that prisons are mostly erected in and staffed by (mostly) white, rural areas to house (mostly) black, urban inmates. If race is so foundational to understanding how and why American prisons have developed the way they have, why is it so conspicuously absent from a game designed to provoke reflection on the American penal system?

We cannot think outside our words, which are our walls and our wardens.The point is not that simulations should perfectly reproduce their subjects, if that were even possible—if it were, we wouldn’t need simulations. Rather, it’s that what is selected and left out of simulation betrays the intentions, motivations, and biases, conscious and not-so-conscious, of those who designed the simulation. For everything Prison Architect gets right about prisons where other games have failed, the absence of race as a meaningful game mechanic is a glaring and disturbing oversight. So it matters, in other words, that Prison Architect was brought to life by three white British designers.

I don’t say this to villainize white designers or white players—I belong in the latter category—but to acknowledge that neither play nor design are politically neutral. It’s not a coincidence that the designers of the carceral system look a lot like the designers of Prison Architect, and, moreover, look a lot like me. The whiteness that binds me and the creative leads of Introversion is, perhaps, the same whiteness that allows me to enjoy Prison Architect’s simulation as a game and that allowed Introversion to design a game about American prisons without grappling with the foundational question of race. Because for me, incarceration is a threat so distant that my only knowledge about it comes from media like Prison Architect, which is what makes getting it right so utterly imperative. Black Americans, who have seen so many lives swallowed up and plundered by mass incarceration, don’t enjoy the same critical distance that structures my acts of play, and Introversion’s choice of subject. So what kind of experience is Prison Architect mediating? What knowledge can we get from it, and what does that knowledge leave out? And what is the cost of these lacunae?

Systems do not think for us. Like prisons, they establish the limits of what can be thought. They do not simply teach; they regulate what there is to be taught. That old linguistic metaphor, “the prison house of language,” means exactly what it implies: We cannot think outside our words, which are our walls and our wardens. Simulations can distort for good, and so help us resist, or ill, and obscure the forces that corral hearts and minds. Every system locks us up. But sims like Prison Architect throw away the keys.

The U.S. Gives Up on Building New Syrian Rebel Groups

If a training program ends in Syria after training practically no fighters, does it make a sound?

Apparently, it sounds like this: “I was not satisfied with the early efforts in that regard, and so we are looking at different ways to achieve the same strategic objectives, which is the right one, which is to enable capable motivated forces on the ground to retake territory from ISIL and reclaim Syrian territory from extremism so we have devised a number of different approaches to that going forward,” Defense Secretary Ash Carter said at a news conference in London.

Details are still emerging. The New York Times reported the Pentagon would make a formal announcement later Friday, and Carter suggested President Obama would speak on it.

A senior official tried to put a brave face on the news, telling The Washington Post this wasn’t the end of the program—simply a reimagining: “It’s being refocused to enhance its effectiveness. It’s being refocused in a new direction.”

But “enhancing the effectiveness” seems to undersell the gravity of the program’s failings. It was designed to provide a counterweight to both the Assad regime in Syria as well as radical groups like Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS, by providing U.S. training to moderate Syrian rebels. The goal was to give the U.S. a serious foothold without requiring major commitments of troops. But it has been, by any standard, a failure. Last month, General Lloyd Austin acknowledged that despite spending $500 million, the program was well short of its goal of 5,400 fighters trained per year.

How short? “We’re talking four or five” fighters still in the field, Austin said. He said more had been trained, but they had laid down their arms, been killed, or were captured. Members of the Senate Armed Services Committee, from Republican John McCain to Democrat Claire McCaskill, were flabbergasted and angry.

The new plan, while still vague, involves training soldiers and embedding them with existing units of Kurdish or Arab fighters already in the field, in an effort to fortify those units, rather than trying to create new rebel groups from scratch. An official told the Times that

there would no longer be any more recruiting of so-called moderate Syrian rebels to go through training programs in Jordan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates. Instead, a much smaller training center would be set up in Turkey, where a small group of “enablers”—mostly leaders of opposition groups—would be taught operational maneuvers like how to call in airstrikes.

In London, Carter held up cooperation with Kurds as a model for going forward.

As the training program spins it wheels, the U.S. has widely been seen as ceding much of the field in Syria to Russia, which has launched airstrikes and missiles, largely on behalf of the Assad regime and ostensibly but not actually against ISIS.

In general, it’s been a rough few months for the Pentagon. At the hearing where Austin divulged the poor training numbers, he was also grilled on reports the military was altering intelligence reports on the fight against ISIS to paint a rosier picture. Meanwhile, the Army is facing difficulties in its other major war, in Afghanistan, as well. Taliban fighters won a major moral victory by briefly taking Kunduz, and the U.S. is now dealing with fallout from an airstrike it launched against a Doctors Without Borders hospital in the city. President Obama called the organization to apologize this week for the strike that killed 22 people.

A Prize for the Jasmine Revolution

The four organizations that worked to ensure a peaceful democratic transition in Tunisia in 2013, in the aftermath of the political unrest that followed the 2011 Jasmine Revolution, have been jointly awarded this year’s Nobel Peace Prize.

The Quartet comprises the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts (UTICA), the Tunisian Human Rights League (LTDH), and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers.

“We are here to give hope to young people,” Ouided Bouchamaoui, president of UTICA, said in an interview. “If we believe in our country we can succeed.”

Many had expected the Norwegian Nobel Committee to give this year’s award to German Chancellor Angela Merkel for her embrace of those fleeing the Syrian civil war, or Pope Francis for his message and work, but in the end the Nobel committee picked the Tunisian Quartet, which, in the committee’s words, “shows that Islamist and secular political movements can work together to achieve significant results in the country’s best interests.”

Tunisia, which until 2011 was ruled by longtime President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, was the birthplace of the Arab Spring—and the only country that, four years after those events, is run by a democratically elected government. But Tunisia’s path wasn’t easy.

In 2013, two years after Bel Ali was ousted, the country was in crisis after the assassination of Mohamed Brahmi, the opposition politician. His killing was followed by massive protests that raised doubts about the nature of Tunisia’s nascent democracy. But the Quartet intervened: It negotiated the resignation of the democratically elected “troika” government and its replacement by a constituent assembly. That was followed by the adoption of a new constitution and fresh elections in 2014.

The Nobel committee said the Quartet “established an alternative, peaceful political process at a time when the country was on the brink of civil war.”

It was thus instrumental in enabling Tunisia, in the space of a few years, to establish a constitutional system of government guaranteeing fundamental rights for the entire population, irrespective of gender, political conviction or religious belief.

The message from the Nobel committee was one of hope, given how the Arab Spring has ended in failure in Egypt, Syria, Libya, Bahrain, and elsewhere.

“Tunisia, however, has seen a democratic transition based on a vibrant civil society with demands for respect for basic human rights,” the Nobel committee said.

But the committee noted that even Tunisia “faces significant political, economic, and security challenges,” an apparent reference to the terrorist attack on Western tourists in July and the attack in March on a museum in Tunis.

The Nobel committee said it hoped the prize will contribute “towards safeguarding democracy in Tunisia and be an inspiration to all those who seek to promote peace and democracy in the Middle East, North Africa, and the rest of the world.”

More than anything, the prize is intended as an encouragement to the Tunisian people, who despite major challenges have laid the groundwork for a national fraternity which the Committee hopes will serve as an example to be followed by other countries.

The committee noted that it hoped the prize would encourage Tunisians, “who despite major challenges have laid the groundwork for a national fraternity which the Committee hopes will serve as an example to be followed by other countries.”

The Quartet will receive the prize of 8 million Swedish kronor (around $975,000). Last year’s prize was given to Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi, who both campaign for children’s rights.

The Giddy Genius of Fargo

The first season of FX’s Fargo, which debuted in April 2014, was very good but decidedly uneven. Though the show came out of the gate strong, it sagged in the middle, getting bogged down in a subplot (featuring Oliver Platt) that bore only a peripheral relation to the principal narrative. The season ended on a relative high note, bringing that main storyline to a bitter close. But it was hard not to feel that this was an excellent four- or perhaps six-episode tale unwisely stretched out to 10.

From the early evidence (I’ve seen the first four episodes), the show’s second season, which debuts Monday, is even better—much better. The cast is excellent, the plotlines are richer and more neatly interwoven, and the alternating portions of whimsy and menace are served up with extraordinary panache. Moreover, unlike the first season, which seemed somewhat captive to the great Coen brothers movie that inspired it—another hen-pecked husband making mortal choices, another female trooper, etc.—this time out the series’ creator, Noah Hawley, has given himself wider narrative latitude and seems still more assured in his black-comic vision.

This season—featuring an entirely new plot and cast—is connected to the last through the character of Lou Solverson, who was the father of season one’s central police protagonist, Molly Solverson. The new season rewinds the clock back from 2006 to 1979, when Lou (now played by Patrick Wilson) was himself a young state trooper. The action launches itself quickly, with a grisly triple homicide at a Waffle Hut in Luverne, Minnesota. (The image of blood intermingling with milkshake is eminently Coens-worthy.)

The killings quickly ensnare a local hair stylist (Kirsten Dunst), her butcher’s-assistant husband (Jesse Plemons), Solverson, and the local sheriff (Ted Danson), who is also Solverson’s father-in-law. Further sucked into the orbit of the murders is the Gerhardt crime family from Fargo, consisting of a patriarch (Michael Hogan), matriarch (Jean Smart), and their three sons (Jeffrey Donovan, Angus Sampson, and Kieran Culkin). The killings come at a particularly bad time for the Gerhardts, who are on the brink of war with a larger crime outfit from Kansas City (principally represented by Brad Garrett and Bokeem Woodbine) that is encroaching on their territory.

All of this takes place against the backdrop of the late 1970s: gas lines, Jimmy Carter’s “malaise” speech, the long, heavy shadows of Watergate and (especially) Vietnam. Though he hasn’t made an appearance yet, Bruce Campbell is slated to play Ronald Reagan on a campaign swing through Fargo later in the season. (The show is dotted with Reagan gags, including more than one fictional movie-within-the-movie, the first of which is the basis for the hilariously disorienting, bravura scene that opens the season.)

As he did last season, Hawley winks at the Coens’ Fargo—Danson echoes the “a little money” line and there’s a clever stand-in for the woodchipper—but he borrows liberally from their wider oeuvre as well, tossing delightful Easter Eggs hither and yon. There are nods to No Country for Old Men (a shot-out door lock), Blood Simple (a live burial), The Ladykillers (the Waffle Hut), and The Man Who Wasn’t There (UFOs—yes, UFOs). Nick Offerman plays a close relative of John Goodman’s iconic Walter Sobchak from The Big Lebowski. One episode ends with a lullaby plucked from Raising Arizona and another with one featured in O Brother, Where Art Thou?. The eagle-eyed may even notice the name of the drug store on the main drag of Luverne, Mike Zoss Pharmacy. This one is a double-backflip of a reference: It’s the name of the drug store robbed by Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men, which was itself a nod to the real-life Minneapolis pharmacy, Mike Zoss Drugs, where the Coens shopped in their boyhood. Hawley has even returned the franchise to its original home state.

There are other echoes as well: The precipitating slaughter at a diner evokes the Nite Owl murders of L.A. Confidential, and the Gerhardt boys—three brothers preparing to succeed an aging patriarch—offer clear echoes of Sonny, Fredo, and (possibly) Michael Corleone. There is a clear (and gruesome) shout-out to Reservoir Dogs, and I’d be surprised if Hawley didn’t have Tintin in the back of his mind when he came up with the Kitchen brothers: twin, mute heavies who act as bodyguards for Woodbine’s character.

Danson once again forces us to wonder what his career might have been had he not spent so much of it toiling in the trenches of sitcom.The show is unrelentingly stylish—possibly better-looking than anything I’ve seen on the small screen since season one of True Detective—and giddily experimental, toying with split screens, montage, black-and-white footage, and stark landscape compositions. The overall tone is, if anything, a touch more overtly wacky than last season, though Hawley seems more clearly in control of the material. (This time out, the inevitable Minnesota-nice “Yah”s and “You betcha”s seem like grace notes rather than—to quote the great Nathan Arizona—the “whole goddamn raison d’etre.”) The score is powerful, and the soundtrack selections a witty, absurdist delight, featuring everything from Billy Thorpe’s “Children of the Sun” to Bobbie Gentry’s “Reunion” to Burl Ives’s “One Hour Ahead of the Posse” to the pseudo-Japanese pop anthem “Yama Yama” to the flat-out nuts opening number of “Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of The War of the Worlds.” (Yes, more UFOs.)

The cast is universally top notch. Craggily paternal, Danson once again forces us to wonder what his career might have been had he not spent so much of it toiling in the trenches of sitcom. Garrett is terrific as the face of a corporatism that is extending even into the realms of organized crime. (At one point he explains his negotiations with the Gerhardts: “If the market says kill them, we kill them. If the market says offer more money, we offer more money.”) Woodbine’s quasi-hipster mobster takes a little longer to find his footing, but he gets better and better as the season goes on. Donovan is flat-out fantastic as the eldest (and roughest) of the Gerhardt boys, and Smart instantly dismisses all memory of Designing Women as his icily resolute mom.

The Broadway star Cristin Milioti (last seen on the small screen as the long-awaited mother in How I Met Your Mother) is quietly wonderful as Solverson’s wife, Betsy, who is undergoing chemo and proves to be the show’s sharpest detective to date. The tender domestic scenes between her and Wilson are among the best on the show. The other principal married couple, butcher (Plemons) and hairdresser (Dunst), offer a slightly more mixed bag. Plemons is doughily appealing (he gained considerable weight for the role) but Dunst’s character—whose mistakes and evasions drive much of the plot—has yet to fully cohere. It feels as though an underlying explanation is missing, one that I hope may be supplied in a future episode.

Which brings me to Patrick Wilson. The actor has done fine work in the past (Angels in America, Little Children, and Watchmen come to mind), but his performance in Fargo is a mild revelation. He imbues Solverson with the aura of understated decency that has characterized many of his prior roles, but there’s something firmer beneath it now. A Vietnam Swift Boat veteran, Solverson has an underlying toughness that is only gradually revealed as the season progresses, a toughness that is made all the more intriguing by his resolute insistence on not playing the tough guy.

In sum, Fargo is smart, thrilling, imaginative television, in addition to being (as I would probably have described it in 1979) wicked funny. If there’s a better show this season—or possibly this year—I’ll be happily surprised. My only reservation, (apart from the quibble regarding Dunst) it’s that I’ve only seen four episodes and, as season one demonstrated, a powerful start does not guarantee sustained momentum. (I’m a little nervous about Campbell as Reagan, and I dearly hope the UFOs stay where they belong, at the distant periphery of the story.) But last season there were already clear signs of narrative fraying by this point, and this time out Hawley has everything tied together as neatly as one could desire. Can he sustain this level of screwy genius for another half-dozen episodes? I don’t know. But I can’t wait to find out.

House Republicans Start Over

First Eric Cantor. Then John Boehner. Now Kevin McCarthy.

Conservatives in and out of Congress have, within a span of 15 months, tossed aside three of the four men most instrumental in the 2010 victory that gave Republicans their majority in the House. When the leaderless and divided party gathers on Friday to begin anew its search for a speaker, the biggest question will be whether that fourth man, Paul Ryan, will take a job that for the moment, only he can win.

Ryan, the 2012 vice presidential nominee and chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, has for years resisted entreaties to run for speaker, citing the demands of the job on his young family and his desire to run the tax-writing panel, which he has called his “dream job.” And he did so again on Thursday, within minutes of McCarthy’s abrupt decision to abandon a race he had been favored to win. “I will not be a candidate for speaker,” Ryan tweeted. Yet the pressure kept coming. Lawmakers brought up his name throughout the day, and there were reports that Boehner himself had personally implored him to change his mind.

Whether Ryan does might be the most important question facing House Republicans, but it is only one of many in the wake of McCarthy’s withdrawal. Lawmakers floated more than a dozen names of members who could seek to replace Boehner in the coming weeks. Some were conservative favorites, like Jeb Hensarling of Texas, the Financial Services Committee chairman, or Jim Jordan of Ohio, head of the House Freedom Caucus. Others suggested the party should turn to a caretaker speaker, who would lead the House only through the 2016 election. Those contenders included two senior members who have already announced their plans to retire after the current term: John Kline of Minnesota, chairman of the Education Committee, and Candice Miller of Michigan, who leads the Administration Committee. The two Republicans who challenged McCarthy, Jason Chaffetz of Utah and Daniel Webster of Florida, continued their candidacies, but there wasn’t anything approaching a groundswell of support for them. And Charlie Dent, a Pennsylvania moderate, said Republicans should band together with centrist Democrats to form a bipartisan coalition to govern the House—a possibility that remains exceedingly unlikely.

Some Republicans tried to silence even the quietest whispers about their names. "I'd rather be a vegetarian,” quipped Mac Thornberry, chairman of the Armed Services Committee. And then there was the ever-available Newt Gingrich, who said he’d consider returning as speaker—but only if the party begged.

“This is a fundamental change in the direction of the party that we’re seeing right now.”The bottom line was that, aside from Ryan, Republicans had no earthly idea who could lead them. In the short term, the uncertainty means that Boehner could have to stay on the job longer than he planned when he resigned last month under the threat of a conservative revolt. Stunned himself by McCarthy’s announced withdrawal, the speaker postponed the GOP elections to give time for the party to regroup. (He also cancelled a planned appearance Thursday on The Tonight Show.) A Boehner spokesman said he still planned to hold the floor election for his replacement on October 29 and then leave Congress the next day, but it was unclear if Republicans could find a candidate by then.

In the meantime, Boehner will face even more pressure to “clean the barn up” for his successor and strike deals with Democrats in the next few weeks to raise the debt limit, agree on a budget, reauthorize the Export-Import Bank, and pass a highway bill. Conservatives would be angered, but knowing that they have no viable alternative, Boehner could be empowered to compromise as never before. Yet if he cannot reach agreements, the chaos in the House could have significant ramifications for the country, as the Treasury Department has said the U.S. could default around November 5 if the debt ceiling is not raised, and funding for the government runs out five weeks later.

Conservatives, meanwhile, declared another victory. “This is a fundamental change in the direction of the party that we’re seeing right now, where rhetoric is going to have to meet up with actions,” Adam Brandon, president of the conservative FreedomWorks, told me. He said McCarthy’s decision would likely prompt a number of conservatives who have declined to run before to rethink their decisions. Yet whether any of them could garner 218 votes in the House remained a big question mark. Hensarling, for example, has become a darling of the Tea Party for his steadfast refusal to advance through his committee legislation reviving the Export-Import Bank, a lending agency that conservatives consider the epitome of crony capitalism. But that decision has angered not only Democrats but moderate Republicans, who are actively trying to go around Hensarling and would probably oppose his promotion to speaker. Similarly, any member closely tied to the Freedom Caucus could be a non-starter for allies of Boehner and McCarthy.

And that brings it all back to Ryan. In addition to Boehner, McCarthy reportedly pressed him to reconsider on Thursday, and even a former top aide to President Obama offered something of a tepid endorsement. As political decisions go, however, accepting the speakership would represent the ultimate sacrifice for a relatively-young leader with presidential aspirations. What has historically been a thankless job is now close to impossible. Even in endorsing Ryan, McCarthy told the National Review that he didn’t know if the House was “governable” and that he determined the job would be no fun even if he won. Given their determination to fight, hard-line conservatives would probably turn on him the moment he struck his first deal with Democrats.

It’s a no-win gig, and right now, Republicans have no one else to do it.

October 8, 2015

Spike Lee and NBA 2K16's Storytelling Revolution

Spike Lee’s latest project opens on one of the strangest images he’s ever captured: three actors wearing skintight body stockings with cameras mounted to their heads and pointed at their faces. As they chat about their undertaking, Lee walks in, claps them on the back, and addresses the camera. Before the story has even begun, he’s lifting the veil—this is how the new Spike Lee Joint, called Livin’ Da Dream, was created. Livin’ Da Dream is the story mode for NBA 2K16, a basketball videogame. He wouldn’t have to do this in a film, but in introducing the real actors involved, Lee is clearly trying to underline artistry at work.

Related Story

A Video Game That Plays Itself

Video games have long experimented with narrative, and the “cut-scene,” or short movie clips that move the story along in between playable sections of the game, has been around for generations. Sports games, mostly intended for playing with friends, haven’t traditionally put much emphasis on storytelling, but with technological advances come new frontiers. In the NBA 2K MyCareer mode, you take on the identity of a young player entering the league, get drafted by a team, and play only as him on the court. Eventually, with some perseverance, you can become a superstar. In Livin’ Da Dream, that basic arc is given a more detailed backstory, and a heck of a lot more melodrama, by Lee.

Few video games value realism more than the NBA 2K series. Each edition of the game, which debuted in 1999 and has been updated every year, is as anticipated by the basketball industry as it is the general public. A player’s overall rating, which determines their effectiveness, is viewed by some as a crucial referendum on their status in the league. When Hassan Whiteside, an unheralded backup player for the Miami Heat, emerged as a superstar last season, he was asked about his out-of-nowhere success by ESPN sideline reporter Heather Cox. “I’m just trying to really get my NBA 2K rating up,” he joked. The game quickly obliged.

Playing a game in NBA 2K16 reflects that commitment to realism. Players’ faces and bodies were scanned to reflect their particular celebrations, facial movements, and tattoos; the camera moves and cuts as if you were watching a real television broadcast; real-life announcers go on long digressions about NBA history and specific players. Each annual edition usually reflects a superficial upgrade on the last, with better graphics, up-to-date team info, and a few new features, but there are enough new features every year to justify the purchase for any basketball fan. 2K16’s major addition is Spike Lee’s involvement; though the MyCareer mode has existed for years, it always felt rudimentary, a canned take on the average career path of an average NBA player. Lee (who is credited on the game’s cover) made one of the most famous basketball movies, He Got Game, and has been brought in to spice things up.

Livin’ Da Dream is as big a failure as it is a success, but its mere existence is fascinating, representing the latest primordial step in the evolution of games into a more narrative form of storytelling. When you start your career, you create a player, pick his position, and sculpt his face and body however you please. But then that creation is plopped into a perfunctory coming of age drama that rings somewhat hollow. You’re a straight-A student from Harlem nicknamed “Freq” (that way the characters can address you without calling you by your given name), with devoted parents, a twin sister who teaches you how to play basketball, and a ne’er-do-well best friend named Vic who encourages you on the path to stardom. You play high school games, choose where to play college ball from a number of universities, debate with your family whether to jump to the NBA after one year, and then get drafted by a professional team.

There are twists and turns along the way not worth spoiling, but all of them are extremely predictable. Lee brings back Al Palagonia, who played the greaseball agent Dom Pagnotti in He Got Game, to reprise the character (who rants and raves about your avatar being the best young player alive). As you achieve success, Vic’s life lurches into tragedy. Your parents and sister remain steadfast fans throughout, but even if you agree with their arguments to stay in college and get a diploma before entering the NBA, the game won’t let you—Lee’s story is on a specific track, and you have to follow it. It’s a fascinating melding of the customizability of video games with the more straightforward approach of film. It’s why Lee introduces his actors at the start of the game: He wants players to understand that there’s more at work here than usual.

Livin’ Da Dream might ultimately be dubbed a failure. Though the game got its usual rave reviews, critics mostly panned the MyCareer mode for making players sit through Freq’s hackneyed story. But it’s worth remembering that home video games as we know them are only some 40 years old. Forty years into the history of cinema, the silent era was just drawing to a close, and the first “talkies” were being released. Lee’s efforts are rudimentary and fail to fully grasp the unique properties of gaming—the level of control the viewer wants, and the variety of storytelling possibilities that can unfold as a result. But NBA 2K, and the gaming industry at large, is only growing more ubiquitous and profitable. These kinds of narrative experiments will eventually strike gold.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower