Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 330

October 5, 2015

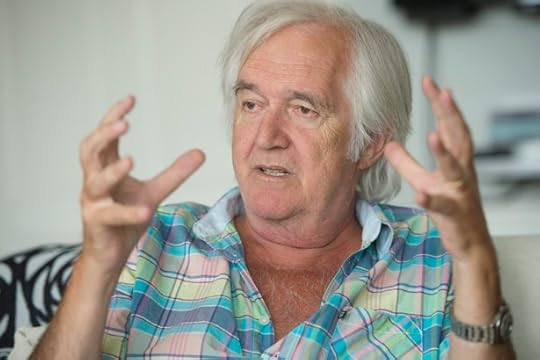

Remembering Henning Mankell

The author Henning Mankell, who died Monday at 67 from lung cancer, came up with the idea for Kurt Wallander after he returned to Sweden from Africa in the late 1980s and was shocked by the racism he saw there.

“Racism for me is a crime, and therefore it seemed natural that I wrote a crime novel,” he said in an interview on his website. “It was after that the idea of a policeman was born.”

What’s striking about Mankell’s series featuring Wallander is its ordinariness. An ordinary policeman, Inspector Wallander, solving crimes in an ordinary town, Ystad, with fewer than 20,000 people. Mankell used the inspector, whose name he fished out of a phone book, and the town to chronicle what was happening in Sweden.

“When I write, I always try to reflect the reality we live in,” Mankell said. “A reality that is becoming rougher and more violent. This violence and its impact on people around it is what I try to reflect in Wallander. But reality always surpasses the poem.”

Mankell certainly wasn’t the first author to write about what he saw as the deficiencies of his society (Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall did that with their Story of a Crime series); nor was he the most successful (that title arguably belongs to Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy). But what he did do was take a genre whose modern plot was crafted by Edgar Allan Poe and transform it into a lens through which to view the modern world—a trait Mankell shares with one of his literary heroes, John le Carré.

In the Wallander books, Sweden is racist, rife with corruption, and has betrayed the ideals of the 1960s. Still, as Mankell told The Telegraph in 2011, that wasn’t how he viewed his home country.

“Sweden is still a very peaceful country to live in. I think that people in Britain have created this mythology about Sweden, that it’s a perfect democratic society full of erotically charged girls,” he said. “That’s bullshit and one of the things I’ve tried to do is correct that.”

And correct it he did. From Faceless Killers, published in 1990, to Troubled Man, published in 2009, Mankell—and through him Wallander—chronicled many of the changes witnessed by Sweden and, indeed, Europe. It explored Sweden’s immigration policy, crime in Europe caused by the fall of the Soviet Union, child abuse, and torture.

The Murder at the Vicarage this is not. In fact, he saw Macbeth as the ideal crime story because it is a “terrible allegory about the corrupting tendency of power.” Readers across Scandinavia, Europe, the U.S., and eventually the rest of the world lapped it up. Mankell saw his work translated into more than 40 languages and sell more than 30 million copies, cementing his place as the dean of Nordic Noir. There were also Swedish film and TV adaptations, as well as the British series starring Kenneth Branagh as Wallander.

Mankell's work has sold more than 30 million copies, cementing his place as the dean of Nordic Noir.It didn’t hurt that Wallander was relatable—and likable. He is diabetic, a workaholic, drinks too much, overeats, is divorced, and has a hard time with relationships. He has a complicated relationship with his daughter, and is the caregiver for his father, an artist afflicted with dementia.

“We share the love of music and we both have a Calvinist attitude towards work,” Mankell said of his hero. “But otherwise, I am not very fond of Wallander as a person, but it doesn’t matter since he is fictional and only exists in my head.”

Mankell did not like being asked about his similarities to Wallander, but there were a few: Like Wallander, he was abandoned by his mother and raised by his father, and he apparently had trouble with relationships. Mankell was divorced three times before marrying Eva Bergman, Ingmar Bergman’s daughter, in 1988.

“It shows I am an optimist,” he told The Guardian in an interview.

But there are differences, too; one being the fact Mankell was an outspoken member of the Swedish left, and a strident critic of Israel and its policies in the Palestinian territories. He was aboard the Gaza-bound flotilla that was blocked by Israel in 2010, and arrested. He accused the Israelis of being “out to commit murder.”

In January 2014, Mankel was diagnosed with cancer, and he decided he would chronicle the treatment and its effects in columns published in several newspapers.

To say Mankell had a complicated relationship with his most famous creation is an understatement. Before his success with the Wallander novels, Mankell was a well-known playwright and the author of 40 books, including some for children. He ran a theater in Mozambique, where he spent much of the year. Upon consigning Wallander to a facility for those with Alzheimer’s in Troubled Man, he said: “I shall not miss” him, before adding: “It is the reader who will miss him.”

It’s safe to say that while Wallander will live on in reprints and adaptations, readers will miss the man who created him.

Republicans Sour on Obama's Trade Pact

Having secured a landmark trade agreement with 11 Pacific Rim nations, President Obama is now relying on trade-loving Republicans to ratify it in Congress. But as details of the pact emerge, the chances of widespread GOP support are dicier than they once were.

Senior Republicans have long been the loudest cheerleaders for the Trans Pacific Partnership. In a reversal of the usual political dynamic, it was the GOP that carried the president’s request for “fast-track” negotiating authority earlier this year and saved him from an embarrassing defeat at the hands of his own party. Yet on Monday those same Republicans criticized the very deal that they gave Obama the power to strike, raising concerns that negotiators for the administration had sold out major U.S. industries in a final rush to finish the agreement.

“While the details are still emerging, unfortunately I am afraid this deal appears to fall woefully short,” complained Senator Orrin Hatch, a pro-trade Republican who, as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, will be key to passing the agreement. Of particular concern to Hatch and other Republicans is a provision excluding tobacco companies from being able to sue governments over regulations seen as targeting their industry. Another Republican, Senator Thom Tillis of North Carolina, said that change from past trade agreements, which was cheered as a victory for public-health advocates, could lead him to vote against the TPP.

Republicans also are upset about the resolution of the final sticking point in the Atlanta negotiations: a shortened period for top drug companies to keep their data secret on advanced medicines known as biologics. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who guided to passage the legislation granting Obama’s expedited negotiating authority, said the agreement was “potentially one of the most significant trade deals in history” but would face “intense scrutiny” in Congress. “We are committed to opening trade in a way that benefits American manufacturers, farmers, and innovators,” he said in a statement. “But serious concerns have been raised on a number of key issues.”

Are the concerns about the final details enough to sink the deal? Administration officials sounded confident that Congress would ultimately ratify it. They pointed out that the lengthy accord hadn’t even been printed yet and that the administration would be spending months going over it with lawmakers point by point. And they debuted a talking point designed explicitly for members of Congress to take back home to their constituents: By eliminating tariffs on U.S. exports to the Pacific, the deal contains some “18,000 tax cuts” for American businesses. “It’s an agreement that puts American workers first and will help middle-class families get ahead,” Obama said in a statement.

“While the details are still emerging, unfortunately I am afraid this deal appears to fall woefully short.”Democrats in Congress overwhelmingly opposed Trade Promotion Authority when it passed in June, and the administration has little hope of persuading most of the party on the substance of the deal. Labor unions and progressives are already gearing up for another fight. Yet Obama will try to flip some lawmakers whose chief concern had been that the agreement was kept secret. Now that it is completed, the deal will be public for at least 60 days before Congress votes, and that vote could slip well into the spring of 2016. And under the terms of TPA, the final agreement needs only a simple majority—and not the usual filibuster-proof 60 votes—to clear the Senate as well as the House.

Another complicating factor for Obama is the presidential election. Bernie Sanders is a staunch opponent of TPP, and his surprising strength in the polls could lead Hillary Clinton to come out against it as well. And on the Republican side, Donald Trump has mocked U.S. negotiators as incompetent. More establishment-friendly candidates like Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio are supportive of the deal, and administration officials may be hoping that Trump is out of the race by the time TPP comes up for a vote next year.

Obama and his team are now two-thirds of the way through a process that began early in his presidency and could result in a legacy-defining trade agreement. The first came with the passage of Trade Promotion Authority over Democratic opposition, and the second came on Monday with the agreement announced in Atlanta. Yet with once-friendly Republicans now wavering, the months-long final leg could become the toughest of all.

Rick and Morty’s Biggest Twist: It Has a Heart

The biggest advantage of an animated TV show is often the biggest disadvantage—limitless scope. Rick and Morty, Adult Swim’s latest cult hit, which wrapped up its second season on Sunday, is a sci-fi show that embraces the creative freedom granted by its format, breezily traveling to alien planets and other dimensions every week and visualizing the most bizarre settings imaginable. But what it managed in its season finale was an emotional gut-punch that felt both unexpected and well-earned. The ending offered a reminder of the show’s less-heralded skill with character development, a quality most of Rick and Morty’s whacked-out cartoon contemporaries lack.

Related Story

Does Community Really Need to Exist Anymore?

The show was initially pitched as a skewed take on the Back to the Future dynamic: Rick is an eccentric scientist, Morty his plucky grandson who adventures with him. But Rick’s motivations for spending time with his grandson are often darkly opportunistic, as he takes advantage of Morty’s pliability and can-do attitude. The show holds onto that thread while expanding its universe as far out as possible, making Rick no regular mad scientist, but literally the smartest being alive, equipped with every invention and burdened with next to no morality. The success of Rick and Morty’s second season wasn’t just its broad imagination, but also how it let Rick incrementally grow a conscience without spoiling the madcap, pitch-black humor at the show’s core.

In the finale, Rick’s decades of interplanetary bad behavior catch up to him, meaning Morty and the rest of his family have to go on the run from galactic cops. They eventually settle on a remote planet so small that it takes five minutes to circumnavigate. Rick and Morty has always excelled at strange sci-fi locations: One episode took place inside a universe that Rick had created in a battery so that its tiny inhabitants could generate power for his car. Another was set inside the minds of Rick’s family as they battled alien parasites that spread through false memories. The bite-sized planet of Sunday’s finale allowed Rick to walk to its South Pole and still overhear his daughter and grandkids refuse to turn him in to the authorities, prompting him to finally make the selfless choice to turn himself in.

Rick and Morty was co-created by Dan Harmon (with the animator and voice actor Justin Roiland) and like his long-running cult hit Community, it manages to be both innovative and classical in its storytelling. The defining pattern of Rick and Morty is that Rick always ends every episode on top through a combination of brilliance and cynicism, so the idea of him as a self-sacrificing hero should seem maudlin and inauthentic. Harmon and Roiland could have easily aired a new wacky sci-fi adventure with their ornery hero and his sidekick for years. Instead, they let Rick’s bitter amorality, and Morty’s ongoing protests at the trail of destruction they often left behind, build up slowly over the season.

Harmon’s legacy in television will be that of the creator who’s never satisfied, to bountiful, creative effect. As Community kept getting miracle revivals from NBC (and later Yahoo) despite low ratings, Harmon constantly had its characters explore the diminished purpose that came with having to tell more stories in the same setting, and the depressing reality of a group of people who’ve been attending community college for six years. That kind of meta-narrative frustrated some viewers and critics, but partly because it’s tethered to the relatable disappointment of working hard to go nowhere. Rick and Morty has the opposite approach—it’s about characters who take multi-dimensional leaps and bounds with every episode—but also confronts relatable human truths about the intangible pull of family and loyalty.

Community’s protagonist is Jeff Winger (Joel McHale), a genius of sorts frustrated by how his small-pond existence contradicts his arrogance. Rick and Morty’s Rick Sanchez is a genius who comfortably thinks of himself as the universe’s cleverest man and is grounded only by his empathy toward other people, which he tries to suppress as much as possible. In the season two finale, the Sanchez family attends an intergalactic wedding, throughout which Rick loudly decries the pointlessness of such a gooey event. But by the end of the episode, he’s making an even more gargantuan, and human, demonstration of love. For a show this fantastically dark, it was the most surprising twist possible.

Passing Blame for the Doctors Without Borders Airstrike

The fallout from the American airstrike that hit a Doctors Without Borders trauma hospital early Saturday in Kunduz, Afganistan, continues to get messier.

The incident, during which 12 staff members from the medical charity and 10 patients were killed, was initially described by an American spokesman as a byproduct of “collateral damage.” An early version of the events asserted the hospital had been hit by airstrikes in response to a Taliban threat against American forces nearby. Afghan representatives also charged the hospital with harboring Taliban fighters, whom they say were firing from the facility.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the French name for the organization, strongly denies this charge and left the city Sunday. The United Nations and other groups have condemned the deadly episode, which MSF has characterized as “a war crime.”

On Monday, General John Campbell, who is the top commander in Afghanistan, clarified the American position during a briefing at the Pentagon.

“We have now learned that on October 3rd, Afghan forces advised that they were taking fire from enemy positions and asked for air support from U.S. Forces,” he told reporters.

Campbell added that this revision deviates from earlier reports suggesting “that U.S. forces were threatened and that the airstrike was called on their behalf.” He added that a thorough investigation is ongoing.

The subtext, if you’ve missed it, is that the airstrike was a response to a plea by Afghan forces based on Afghan accounts of events on the ground. Following Allen’s remarks, MSF released a statement late on Monday morning:

Today the US government has admitted that it was their airstrike that hit our hospital in Kunduz and killed 22 patients and MSF staff. Their description of the attack keeps changing—from collateral damage, to a tragic incident, to now attempting to pass responsibility to the Afghanistan government. The reality is the US dropped those bombs. The US hit a huge hospital full of wounded patients and MSF staff. The US military remains responsible for the targets it hits, even though it is part of a coalition. There can be no justification for this horrible attack. With such constant discrepancies in the US and Afghan accounts of what happened, the need for a full transparent independent investigation is ever more critical.

It’s Extremely Rare for Large Ships Like El Faro to Disappear

El Faro—a 790-foot cargo ship whose name means “lighthouse”—has apparently sunk in the Atlantic Ocean, the U.S. Coast Guard believes.

Rescuers have been searching for the container ship, which was in the path of Hurricane Joaquin, since the crew last made contact Thursday morning, saying El Faro was listing but the situation was manageable. The vessel was carrying 33 people—28 Americans and five Poles—and while searchers have found debris they believe came from the ship, they haven’t found the vessel itself or any survivors. One body has been found.

While nautical disasters remain a fact of life—everything from missing sailboats to deadly catastrophes like the Costa Concordia’s sinking or recent ferry disasters in Asia—it is exceptionally rare for a large ship like El Faro to disappear.

How rare? An analysis of vessels greater than 100 gross tons by the insurance giant Allianz found that in the past 10 years, from 2005 to 2014, only six ships were reported as “missing/overdue”—or, in other words, lost. Three were in 2005. There were none reported in 2011, 2012, 2013, or 2014.

This isn’t to say that ships don’t sink. In 2014, 49 ships “foundered,” which includes sinking or submerging—the largest category of ship losses. But often those are cases where ships sink with some warning, and most or all of the crew can be rescued. The second-largest category is ships that ran aground. (An excellent 2008 Wired story goes inside the world of ship-salvage crews that try to right these vessels.) It’s not an illusion that shipping seems safer these days. The number of total losses has decreased over the last decade.

And no ship lost in 2014 in any method—foundered, wrecked, or otherwise—was as large as El Faro, which was built in 1975 and was 790 feet long with a gross tonnage of 31,515. The biggest cargo ship lost last year was 12,630 gross tons, and while eight of 20 crew members died, that was in a collision—not a disappearance. The Caribbean, where El Faro is missing, also sees comparatively few losses versus the South China Sea, the Mediterranean, or the British Isles.

U.S. Coast Guard members retrieve a life- preserver ring from El Faro on Sunday. (Reuters)

U.S. Coast Guard members retrieve a life- preserver ring from El Faro on Sunday. (Reuters) It’s far too early to know what went wrong with El Faro. It’s not uncommon for cargo ships to lose containers in heavy seas, but sinking is. Allianz lists several risk factors for ships: overreliance on electronic navigation; understaffed or undertrained crews; and structural weakness. El Faro was much older than the average container ship worldwide, which is just under 11 years old, but her owner told the AP the boat was in good condition and suited to rough weather because she was built for Alaskan trade: “She is a sturdy, rugged vessel that was well maintained and that the crew members were proud of.”

Beyond that, large container ships are generally built to withstand major storms. The nature of the business is that captains still have great discretion in how they choose to handle a storm, or whether to try to avoid it. El Faro had a built-in advantage in that it was carrying cargo; an empty ship is harder to handle in rolling waves, Popular Mechanics noted in 2012. Port has its own risks—a ship can be battered against a pier or run aground.

That encourages some captains to stay at sea. Before losing contact, El Faro radioed that it was aware of the weather and was prepared. But, retired captain Max Hardberger wrote for the trade site gCaptain, “If the master does decide to put to sea, he should realize that he may be exchanging a dangerous situation for a suicidal one.” If in a storm, however, the captain has to concentrate on two things, he wrote: keep plenty of room away from shore, reefs, and other obstacles; and keep the boat pointing into the waves.

Steering-way is necessary to keep the bow into the wind and waves. If the main engine fails and the ship falls off broadside to the waves, it will be in a perilous situation. The ship must also have adequate sea room to leeward, both as insurance in case she loses steering-way and to counter the effects of wind, waves, and current. If the master has any doubts about his searoom, he must make way offshore while it is still possible.

Failing all that, ships are typically equipped with enclosed lifeboats that can launch in a storm and will withstand bad conditions. In pitching seas, it can be impossible to launch a traditional, uncovered lifeboat. A boat from the famous Edmund Fitzgerald, found shorn apart after the sinking, shows their inadequacy. But a crew needs to have some warning in order to get into modern lifeboats, too. So far, searchers have found one of the ship’s two boats. It was empty.

Protesters Tear Air France Executives’ Shirts From Their Backs

On Monday, October 5, union activists protesting against proposed layoffs at Air France-KLM broke through fences and disrupted a meeting, targeting at least two managers who were forced to flee the angry crowd, their clothes ripped from their backs. Air France-KLM had just announced a restructuring plan that would lead to 2,900 job cuts after pilots had refused to accept a proposal to work longer hours. Director of Air France in Orly Pierre Plissonnier and Air France Human Resources Director Xavier Broseta bore the brunt of the protest, eventually escaping over a fence with the help of security team members.

A Deal to Unite the Pacific Rim Through Trade

Updated on October 5 at 9:48 a.m. ET

Negotiators from 12 Pacific Rim countries, including the U.S., have agreed on a sweeping trade deal that would bring together about 40 percent of the global economy.

Big win for U.S. workers: @POTUS just secured a trade deal that helps the middle class. http://t.co/RCNK0hj6NP #TPP pic.twitter.com/SFXtD1fKys

— The White House (@WhiteHouse) October 5, 2015

The Trans-Pacific Partnership includes Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, the U.S., Singapore, and Vietnam. It would be President Obama’s signature achievement on global trade and would mark his pivot toward Asia.

Michael Desch, a professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame, called the TPP the “jewel in the crown” of Obama’s foreign-policy achievements.

“Walking this tight-rope between engagement [with China] and containment [of it] will be a challenge, as will dealing with domestic opposition to more free trade with China, but the Obama Administration seems committed to making this a big part of its legacy,” he said.

The agreement, as you might have noticed, does not include China, and Beijing views that as a deliberate attempt to develop an economic counterweight to the world’s second-largest (and by some measures largest) economy.

The TPP, which has been negotiated for nearly eight years, would be the largest-ever regional trade deal, and, as you would expect, it has strong opposition not only in the U.S. Congress, but also overseas. Congress must ratify the deal, which faces opposition from both Democrats as well as Republicans.

Part of the problem, as Alan Morrison wrote in The Atlantic in June, is the deal contains provisions that would allow foreign investors to bypass the federal courts.

But its supporters say the TPP would remove trade barriers and raise labor as well as environmental standards.

A Russian Violation of Turkish Airspace

Turkey says a Russian warplane violated its airspace over the weekend, but left after its F-16s intercepted the aircraft. It’s the latest sign of tensions between Russia and the U.S. and its allies over Moscow’s role in the Syrian civil war.

The Turkish Foreign Ministry in a statement said the Russian plane violated Turkish airspace on Saturday south of Yayladağı, in the Hatay Province. The statement said the Russian ambassador to Ankara was summoned to the Foreign Ministry and Turkey “demanded that any such violation not be repeated and affirmed that, otherwise, the Russian Federation will be responsible for any undesired incident that may occur.” It said the Turkish foreign minister spoke to his Russian counterpart and reiterated those views.

In Moscow, Russia said it was continuing its strikes against the Islamic State.

Last week, Russia began airstrikes in Syria against the Islamic State, one of several groups fighting against President Bashar al-Assad. But Russian airstrikes have also targeted Western-backed groups that are fighting the Syrian leader. The U.S. and its allies are conducting their own airstrikes in Syria, but these are targeting the Islamic State.

On Friday, President Obama said Russia’s actions would lead it into a “quagmire” in Syria. He said the two countries had a “common interest in destroying ISIL,” but Russia “doesn’t distinguish between ISIL and moderate groups.”

The New York Times is reporting that the U.S.-led coalition has “begun preparing to open a major front in northeastern Syria,” aiming to put pressure on Raqqa, which is controlled by the Islamic State.

Meanwhile, activists are Syrian officials say the Islamic State has destroyed the historic Arch of Triumph in the ancient city of Palmyra. The arch is believed to have been built about 2,000 years ago.

The Islamic State previously destroyed the Temple of Baalshamin and the Temple of Bel, both in Palmyra, a UNESCO Heritage Site that is now controlled by the group. The Islamic State believes that such sites represent idolatry.

Man Booker Shortlist 2015: Satin Island

Knopf Doubleday

Knopf Doubleday Tom McCarthy—whose fourth novel, Satin Island, is one of two British books to make the Man Booker shortlist this year—is the only nominee who’s enjoying the experience for the second time. His previous novel, C, claimed a spot in 2010, but if you put any faith in London’s bookies, he’s not likely to win this time. He’s bringing up the rear in the most recent standings.

You might say that McCarthy is just the kind of writer to make it onto the list, and then not get all the way to the top. His avant-garde work has earned high acclaim from critics, including Zadie Smith, who wrote in 2008 of McCarthy’s debut novel,

… it is easy to feel that Remainder comes to literature as an assassin, to kill the novel stone dead. I think it means rather to shake the novel out of its present complacency. It clears away a little of the dead wood, offering a glimpse of an alternate road down which the novel might, with difficulty, travel forward.

And yet that glimpse can leave readers—and perhaps judges, too—scratching their heads even as they’re drawn along, deeply curious.

As critics have noted, Satin Island lacks traditional plot, setting, and character development. Instead, the novel consists of the stream-of-consciousness of an obsessively observant anthropologist, U., who is at work on a Great Report documenting the patterns that define life in the digital age. It’s no small feat to make the internal processing of information the most compelling element in a novel, and McCarthy manages that in pages saturated in symbolism and rendered in hypnotically simple prose. Through U., he also plants the refreshing suggestion that literature can do justice to the character—perhaps the everyman—whose life does not derive much significance from its narrative arc.

At the same time, McCarthy lures the reader into sharing U.’s predicament. Like him, we’re launched on a baffling quest to make sense of dizzying detail. As Duncan White wrote in The Telegraph, “Every chapter—no, every sentence—invites you to plunge deeper into the book’s dark pool, groping for the submerged pattern … On finishing it you will have the powerful urge to throw it across the room then the powerful urge to pick it up to read again.”

That’s just what the Man Booker judges, of course, will be doing over the course of these weeks. I’ll shamelessly plug The Atlantic’s review, by Marc Mewshaw, as an ideal guide to, as he puts it, McCarthy’s “portrait of our overstimulated, interconnected, simulacra-addicted times,” not least because Mewshaw wisely counsels against expecting too much closure:

There’s a growing momentum to the convergences in the text, a sense of a master message encoded in the architecture of symbols that will disclose itself if only the reader connects all the dots. The missing link, the revelation that will explain everything, feels, like the presence of the divine, tantalizingly close but always just beyond reach. That it never materializes may just be the book’s ordering principle.

So instead of probing for some hidden message, I’ll settle for offering a taste of the reading experience—that plunge into a “black pool,” into a sea of unconnected dots. U. documents his findings in discrete paragraphs about his disparate observations, a sort of jumbled set of notes for that Great Report. I’ll take my cue from him, singling out a few passages that convey U’s own “weirdly hyper-alert gaze” at work, exerting a contagious pull on the reader turning the pages.

Here is U., the “corporate anthropologist” who avidly monitors his surroundings—tracking habits, textures, dreams, the media, personal technology—as he takes an inventory of the possessions of a barstool acquaintance:

… a cigarette pack, a plastic lighter, a dog-eared travelcard and a key-fob, fanned out in a rough semicircle across the zinc counter, like a spread of cards. She was, like many single women in her situation, using these objects to create a buffer zone around herself, in which her lifestyle, personality and, not least, availability were simultaneously signaled and withheld.

But just what U. doesn’t do is create a buffer zone. He presses on, his inner processor whirring:

… I lost myself among them. And as I did, I felt a fragile, almost epiphanic tingling of what-if-ness come across me … What if just coexisting with these objects and this person, letting my own edges run among them, occupying this moment, or, more to the point, allowing it to occupy me, to blot and soak me up, rather than treating it as feed-data for a later stock-taking—what if all this, maybe, was a part of the Great Report.

Or try this moment, when U. transitions from the practical to the metaphysical in a poignant scene. He’s visiting a sick friend and finds himself reconsidering his earlier conviction that the hospital’s dirty windows were inappropriate for a sickroom:

… I came to see that, along the very lines that had made me view it as so wrong earlier, the windows’ dirtiness was in fact totally correct. It was the world, its stuff, that had left its deposit—on the windows and in Petr’s bones, his organs, flesh and arteries. The stuff of the world is black. If Petr’s flesh was turning black, it was because he’d let the world get right inside him, let it saturate him, until he was so full of it that it was bursting out again, erupting with a radiating luminescence.

U. pays no attention to scale as he gathers the grist for his Great Report—dirt on a window or a series of unfamiliar possessions easily feed his grand theories. I found myself mimicking the extrapolating habit as I plowed through U.’s copious observations, many of which he leaves dangling. When U. remarked that “the sky was a crime scene” in the case of a parachuting death, did he mean to condemn nature while overlooking the culprit, man-made invention? Was he implying that this is a symptom of our era? I grasped hopefully for a signal in the entertaining noise of patterns and ponderings within his mind.

After reading and reflecting on Satin Island, I can’t help believing that such a signal exists. Yet I can also feel McCarthy’s eagerness to leave me mystified. As U. contemplates submitting his Great Report to his boss, he muses on how it’s likely to go over, aware that perception is anything but straightforward: “Certainly, the fact that it came from me, and the context within which it was presented, would imbue it for him with all kinds of cryptic meaning.” How the Man Booker judges will respond after re-reading McCarthy’s enigmatic creation is, fittingly, anybody’s guess.

October 4, 2015

Germany’s Refugee Crisis Is Getting Worse

When Germany announced in August that it would waive United Nations rules and allow Syrian migrants to apply for asylum regardless of how they got there, officials knew to expect a flood of people. Hopeful families were already surging into the country from all over the Middle East, an area crippled by social strife and political chaos. Authorities predicted the arrival of more than 800,000 refugees to the country by the end of 2015, and they tried to prepare accordingly.

But Germany is now sagging under the weight. Its cities and towns cannot easily accommodate all the refugees. An official from the Berlin Refugee Council called the issue an “organizational problem” rather than a financial one: Authorities don’t have the resources—or the time—to quickly provide registration, funds, secure accommodation, health services, and identification to all the refugees, 200,000 of whom arrived in September alone.

German police and politicians are frustrated. Exhausted migrants who traveled hundreds of miles to escape civil war only to be held in weeks-long waiting lines are even more so. And adding to Germany’s existing logistical problems now is another: The impending arrival of a freezing, harsh winter.

“I wish I'd stayed in Syria and not come here,” a 26-year-old Syrian migrant told Reuters through an interpreter. "I dreamed Germany would be better, but it's so bad. We've been sleeping in the cold. Now my baby is sick."

Thousands of other migrants are facing similar problems. Registration offices are slow to identify and register migrants, especially those without documents—and they’re also approaching the process with heightened suspicion, since plenty of false claims have cropped up since the country opened its doors to Syrian refugees. In Berlin, some people have been sleeping outside for nearly a month, waiting to register. Others have given up trying to apply and taken up shelter on their own, creating yet another headache for German authorities.

The process of registration—which involves taking migrants’ photos and fingerprints, providing them with temporary documentation, and distributing them evenly across the country—used to take a few hours per person, but now takes two days or more, according to Berlin’s health and social affairs office.

Germany’s new refugee policies, announced in August, initially received widespread approval, with two-thirds of the country agreeing with the decision to give refuge to stranded asylum-seekers. Though U.N. regulations say refugees must apply for asylum in the first European Union country they enter, Germany is processing applications from Syrians even if they traveled through another EU country.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has since seen a steep decline in her popularity ratings. Still, Merkel stands by her decision to allow Syrian migrants to flee from civil war, insisting that she would make the same decision again today.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower