Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 329

October 6, 2015

Can You Cut a Drought (or a Steak) With a Plastic Knife?

The historic drought in California, in addition to being linked to wildfires and economic and agricultural troubles, has forced residents and officials to grapple with divisive lifestyle changes. Consider this polarizing aerial shot of a golf course in San Bernardino or the devil-may-swim attitude of some wealthy Californians in the face of water restrictions and threats of fines.

Watching this challenge play out along state and local levels is a surreal exercise. For a restaurant-goer, for example, only receiving a glass of water upon request seems like a small, but telling departure from a normal dining experience. In Fort Bragg, California, conditions are so severe the city recently passed an emergency order that prohibits the watering of landscaping and the washing of building exteriors, sidewalks, driveways, and cars.

The city is also requiring restaurants to refrain from using plates, cups, and silverware that require washing. That means if you go to one of the coastal city’s tourist-friendly canteens or trattorias, you could end up eating your $30 Snapper Vera Cruz on a paper plate or drinking your Anderson Valley pinot noir from a plastic cup.

“You might be able to cut a filet mignon with a plastic knife, but you are not going to cut a New York,” one Fort Bragg restauranteur told the San Francisco Chronicle. “The expense is going to be horrendous, I would expect. So that’s going to be a major impact. It seems to me there are other ways to save water.”

The measure also rings of filling a landfill to spite a drought. But with water levels so low that ocean water is trickling into Fort Bragg’s drinking supply, it’s tough to second guess.

The Public Shaming of Chrissie Hynde

In maybe one of the most uncomfortable NPR interviews since Joaquin Phoenix went on Fresh Air, the Pretenders singer Chrissie Hynde spoke with Morning Edition’s David Greene on Tuesday about her book, Reckless. Or, more specifically, about the mass outrage sparked by the section in which she writes about being sexually assaulted at the age of 21 by a group of bikers, and of taking “full responsibility” for it.

GREENE: I’ll just read a little bit here: “The hairy horde looked at each other. It was their lucky day. ‘How bout yous come to our place for a party.’” And you ended up with them, and then you proceeded to describe what they were asking you to do. “‘Get your bleeping clothes off, shut the bleep up, hurry up, we got bleep to do, hit her in the back of the head so it don't leave no marks.’” This certainly sounds like an awful, awful experience with these men.

HYNDE: Uh, yeah. I suppose, if that's how you read it, then that, yeah. You know, I was having fun, because I was so stoned. I didn’t even care. That’s what I was talking about, I was talking about the drugs more than anything, and how f***** up we were. And how it impaired our judgment to the point where it just had gotten off the scale.

“I’m just gonna say it, Chrissie Hynde is a really tough interview,” Greene says early on. And in her conversation with him, Hynde is indeed difficult: She declines to expand on an anecdote about her love of The Rolling Stones from the book, stating that she doesn’t want to repeat what’s already out there, or feel like she’s at a reading. She’s brusque, even rude, in her manner. She’s also extremely defensive, particularly when pressed on her comments that women are sometimes to blame for being sexually assaulted, and the reaction that ensued.

“I’m not here as a spokesperson for anyone,” she tells Greene. “I’m just here telling my story. So the fact that I've been—you know, it’s almost like a lynch mob.”

Related Story

Ending the Internet Outrage Cycle

No matter how Hynde seeks to qualify it, or declines to use the word “rape,” what happened to her at 21 was undoubtedly a traumatic and vicious assault—one that she’s possibly chosen to deal with for the past four decades by affording herself a degree of power and complicity in what happened. And there’s no denying that speaking publicly, as Hynde has done, about how women can be to blame for being sexually assaulted if they’re dressed provocatively is both wrongheaded and extraordinarily damaging to many victims of rape. But Hynde’s choice of words—comparing the outraged responses to her comments to a “lynch mob”—seems to demonstrate that she feels more victimized by the flood of comments and messages and thinkpieces and news hits responding to her story than she does by actually being assaulted in the first place.

Which begs the question: Is attacking Hynde for blaming herself (and yes, by association, blaming others) ultimately productive and worth the cost of re-victimizing her? Or is the impulse to shame her and others like her sometimes more about self-gratification than advocacy?

* * *

If 2014 was the “Year of Outrage,” as Slate posited, 2015 has been the year of witnessing how outrage manifests, and the consequences it can have on people’s lives in a matter of minutes. In March, the British journalist Jon Ronson published So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, a book in which he interviews recent targets of popular approbation about the impact it had on them. In June, Rachel Dolezal resigned from her position as president of the Spokane NAACP after it emerged that she had lied about and disguised her race. In July, an American dentist, Walter Palmer, had to flee his home and practice after he was revealed to have shot and killed a protected lion in an African nature reserve. Last month, the BBC called the pharmaceutical CEO Martin Shkreli “the most hated man in America” after his company raised the price of a drug for AIDS patients by 5,000 percent.

Also in September, Hynde published Reckless, and gave an interview to The Sunday Times in which she said women who dress provocatively put themselves in more danger than those who dress and act modestly.

“If I'm walking around and I'm very modestly dressed and I'm keeping to myself and someone attacks me, then I'd say that's his fault,” she said. “But if I'm being very lairy and putting it about and being provocative, then you are enticing someone who's already unhinged—don’t do that. Come on! That's just common sense ... I don’t think I’m saying anything controversial, am I?”

For many, she was. “Chrissie Hynde, the Pretenders’ Female Lead Singer, Just Blamed Rape on Its Survivors,” read a headline at Mic News. On the outrage spectrum, Hynde’s comments fell somewhere between Dolezal/Palmer/Shkreli and the manifold micro-outrage storms that erupt on a daily basis—a Taylor Swift video shot in Africa featuring only white people, a reality star styling her hair in cornrows, anything Azealia Banks posts on Twitter. Still, they offer insight into how social-media users tend to respond to inflammatory opinions.

Anger spreads more easily than any other emotion on social media, and considerably more rapidly than joy, the next most viral emotion.“Bile has been a part of the Internet as long as Al Gore has,” Teddy Wayne wrote in The New York Times in 2014 in an insightful piece about social-media outrage. “But the last few years have seen it crawl from under the shadowy bridges patrolled by anonymous trolls and emerge into the sunshine of social media, where people proudly trumpet their ethical outrage.”

Wayne cites a study conducted at Beihang University in 2013, which found that anger spreads more easily than any other emotion on social media, and considerably more rapidly than joy, the next most viral emotion. The study also mentions homophily, or the social phenomenon wherein groups of likeminded people band together, validating each other’s ideas and supporting each other’s reactions and feelings. On social media, this encourages ferocity and discourages nuance, particularly when thoughts are limited to 140 characters. “Twitter is basically a mutual approval machine,” Ronson said in a TED Talk in June. “We surround ourselves with people who feel the same way we do, and we approve each other, and that’s a really good feeling. And if somebody gets in the way, we screen them out. And do you know what that's the opposite of? It's the opposite of democracy.”

Outrage, in other words, enables people to tout their ethical impeccability to others while simultaneously being embraced into a vast and influential group. For such a negative emotion, it has a surprisingly warm and fuzzy effect—unless you’re the person on the receiving end.

In some cases, outrage can be productive. If reactions to a former hedge-fund manager gouging the most physically vulnerable people in society for corporate profit encourages more people to protest ridiculous prices on necessary drugs, that’s indisputably a positive. But the endorphin rush of expressing fury about something and seeing that opinion validated and shared by a significant number of others is presumably as addictive as any other high. After a certain point, as Ronson described, “it began to feel weird and empty when there wasn’t a powerful person who had misused their privilege.” And that means people like Hynde, who deserve sympathy as much as scrutiny, often suffer in the process.

* * *

Forcing public figures to instinctively fear saying anything even remotely offensive doesn’t encourage argument, or intellectual rigor, or even honesty. Instead, it compels people to stick to bland soundbites and safe topics. But it also encourages the manipulation of outrage for publicity, for drama, and for financial gain. Presumably Hynde, a 64-year-old who clearly doesn’t manage her own Twitter and Facebook accounts, had no idea how provocative her comments would be. Generationally, she’s perhaps not as informed about sexual assault as many younger social-media users are. But it’s hard to imagine that her publisher didn’t take a guess, or that the wave of stories condemning her has had a negative effect on her book sales, even while it’s clearly traumatized her on a personal level.

None of this is to say that people shouldn’t be outraged about sexual assault, or about the incredibly misguided belief that women can be responsible for it happening to them. But the instinct to lash out at someone who’s honest about a terrible thing that happened to her, and to victimize her once again, ultimately says more about the people doing the shaming than it does the supposed perpetrator. Meanwhile, people are focusing on one part of Hynde’s book over everything else it contains. “The only reason I’m here and the only reason you’re talking to me is because I made some records, and I go on tour with a band,” Hynde told Greene.

But in the end, that wasn’t what they talked about. Instead, Greene focused primarily on the most provocative anecdote from her book (reading the section about the assault aloud), and challenged her on why she continues to insist that she wasn’t raped. The response on Twitter? A condemnation of Hynde for being so hostile.

A Self-Defeating Crusade Against Salman Rushdie

Twenty-seven years after the publication of his book The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie’s most notorious work and its legacy still engender controversy. On Tuesday, The Guardian reported that Iran is threatening to boycott the Frankfurt Book Fair because Rushdie is to make the festival’s opening keynote address.

“This has been organized by the Frankfurt Book Fair and crosses one of our political system’s red lines,” said Seyed Abbas Salehi, Iran’s deputy minister for culture and Islamic guidance. “We consider this move as anti-cultural.”

The Satanic Verses infamously prompted Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomenei to issue a fatwa against Rushdie, a British citizen, in 1989. The religious edict technically still stands, but is no longer part of the Islamic Republic’s state policy. Iran renounced the death threat to restore ties with the United Kingdom in 1998. During those years, Rushdie’s travel abroad was limited and he was frequently accompanied by security wherever he went.

In his recent statement, Salehi defended the edict, saying “Imam Khomeini’s fatwa on this issue is reflective of our religion and it will never fade away.”

But at what cost? The Frankfurt Book Fair is one of the world’s largest festivals of its kind, and those who would suffer the most from an Iranian boycott would be Iranian authors themselves. The Guardian notes that nearly 300 Iranian publishers attended last year’s festival, representing some 1,200 books.

“The publication of polemic literature and its consequences affect not just authors but the entire publishing industry,” writes the festival’s website in promoting Rushdie’s speech. “That’s why freedom of expression and boundaries are key topics at this year’s book fair.”

The Evolving U.S. Line on the Kunduz Airstrike

How did the U.S. bomb a Doctors Without Borders (MSF) hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan? The group and the world have questions, and the U.S. government has answers—several of them, with the latest coming from General John Campbell in a Senate hearing Tuesday morning.

“The hospital was mistakenly struck,” he said. “We would never intentionally strike a medical facility.”

Following the bombing on Saturday, a U.S. military spokesman on the ground in Afghanistan said that an airstrike “may have caused collateral damage to a nearby medical facility,” but the U.S. didn’t acknowledge hitting the hospital. The backlash against that was fierce, with MSF angrily rejecting that as inadequate for the deadly incident that killed 22 people.

Next, Defense Secretary Ash Carter admitted in a statement that the hospital had been hit in a “tragic” accident.

On Monday, Campbell revised the official narrative, saying the U.S. was simply carrying out a strike requested by Afghan fighters on the ground. “We have now learned that on October 3rd, Afghan forces advised that they were taking fire from enemy positions and asked for air support from U.S. forces,” he said. “An airstrike was then called to eliminate the Taliban threat and several civilians were accidentally struck.”

But in Tuesday’s Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, Campbell clarified: The Afghans made the request, but the decision was made within the U.S. chain of command. “Even though the Afghans request that support, it still has to go through a rigorous U.S. procedure,” he

Russia’s Violation of Airspace ‘Doesn’t Look Like An Accident’

NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg says Russia’s violation of Turkey’s airspace “doesn’t look like an accident.” The comments mark an escalation in the rhetoric between the alliance and Russia over Moscow’s actions in the Syrian civil war on behalf of President Bashar al-Assad.

As we reported Monday, Turkey said a Russian warplane violated its airspace over the weekend, but left after its F-16s intercepted the aircraft. Russia called the violation an accident, and said the incident was being used by NATO as anti-Russian propaganda.

At a news conference in Brussels on Tuesday, Stoltenberg noted that there were, in fact, two violations of Turkish airspace by Russian warplanes, and those violations “lasted for a long time.”

“For us this doesn’t look like an accident,” he said, calling the violations “unacceptable.”

Read Follow-Up Notes David Frum on the Russian interventionThe U.S. and its fellow NATO members have criticized Russia’s airstrikes in Syria. Russia says its planes are only targeting the Islamic State and other terrorist groups, but Western-backed, anti-Assad rebels have also been targeted. And while Russia says its actions in Syria will be confined to airstrikes, Admiral Vladimir Komoyedov, the head of the defense committee in Russia’s parliament, said Monday, “It is likely that groups of Russian volunteers will appear in the ranks of the Syrian army as combat participants.”

That would mark a replication of the playbook Russia has used in Ukraine where hundreds of volunteers are fighting on the side of the pro-Russian separatists. And if that were to happen in Syria, it would mark the first time Russians have been involved in ground combat operations outside Europe since the country’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in the late 1980s. President Obama, at a news conference last Friday, warned that Russia’s actions in Syria would lead it into a “quagmire.”

But the U.S. role in Syria has itself been criticized as ineffectual. Its attempts to train anti-Assad rebels have yielded embarrassing results. Though The New York Times reported Monday that the U.S.-led coalition has “begun preparing to open a major front in northeastern Syria,” aiming to put pressure on Raqqa, which is controlled by the Islamic State.

Safe Harbor No More

The European Court of Justice has ruled regulations that allow U.S. companies to handle the personal data of EU citizens are invalid.

At issue is the question of privacy. The EU has some of the strictest rules on privacy, and companies operating inside the 28-member bloc are barred from sending personal information outside its borders without certain guarantees of protection. The Safe Harbor rules, negotiated by the U.S. and the EU in 2000, allowed tech giants such as Amazon, Facebook, and Google to handle the personal information of millions of people in the EU and move them to the U.S., if they meet certain requirements.

But that agreement was challenged by Max Schrems, an Austrian graduate student, who argued that personal data of EU citizens was misused by the National Security Agency’s Prism program. Several major tech companies, including Facebook, are believed to have cooperated with the program.

On Tuesday, the European Court of Justice agreed. It said the agreement compromised “the essence of the fundamental right to respect for private life,” and “the essence of the fundamental right to effective judicial protection.”

Here’s its ruling, in part:

As regards a level of protection essentially equivalent to the fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed within the EU, the Court finds that, under EU law, legislation is not limited to what is strictly necessary where it authorises, on a generalised basis, storage of all the personal data of all the persons whose data is transferred from the EU to the United States without any differentiation, limitation or exception being made in the light of the objective pursued and without an objective criterion being laid down for determining the limits of the access of the public authorities to the data and of its subsequent use. The Court adds that legislation permitting the public authorities to have access on a generalised basis to the content of electronic respect for private life.

Likewise, the Court observes that legislation not providing for any possibility for an individual to pursue legal remedies in order to have access to personal data relating to him, or to obtain the rectification or erasure of such data, compromises the essence of the fundamental right to effective judicial protection, the existence of such a possibility being inherent in the existence of the rule of law.

Finally, the Court finds that the Safe Harbour Decision denies the national supervisory authorities their powers where a person calls into question whether the decision is compatible with the protection of the privacy and of the fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals. The Court holds that the Commission did not have competence to restrict the national supervisory authorities’ powers in that way.

The court is the EU’s highest court, and its ruling is binding.

Schrems, in a statement, said he welcomed the ruling, “which will hopefully be a milestone when it comes to online privacy. This judgement draws a clear line. It clarifies that mass surveillance violates our fundamental rights. Reasonable legal redress must be possible.”

Many major multinational companies may not be immediately affected by the ruling, however, because they have their own agreements with the EU on the transfer of data, but the court’s ruling is a shot in the arm to advocates of privacy.

“This is extremely bad news for E.U.-U.S. trade,” said Richard Cumbley, a tech lawyer at Linklaters in London, told The New York Times. “Thousands of U.S. businesses rely on the Safe Harbor as a means of moving information. Without Safe Harbor, they will be scrambling to put replacement measures in place.”

Jeffrey Chester, the U.S. chair of the Trans-Atlantic Consumer Dialogue’s information society policy committee who also serves as executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy said:

Safe Harbor was designed to enable US data companies to engage in nothing less than pervasive commercial surveillance in the EU.. The US authorities do not investigate or have the enforcement resources or legal tools to protect Europeans’ data. The end of the current Safe Harbor regime will be a major global victory for privacy.

But Congressman Jim Sensenbrenner, a Republican from Wisconsin, saud he was “disappointed” by the court’s “bold move.”

The United States has taken great strides to build strong data protection and privacy controls, such as USA FREEDOM, which was the first curtailment of surveillance authority in the U.S. since the 1970s. It was a thoughtful rethinking of our national security laws that few other countries have undertaken. With the Judicial Redress Act, Congress has taken additional steps toward providing global citizens’ rights over their own data. These efforts will continue in the U.S., as they should abroad, but we must maintain an environment of cooperation and goodwill with our allies. I urge EU and US officials to address this issue and to work to maintain the healthy commercial relationship the EU and the US have worked so hard to build.

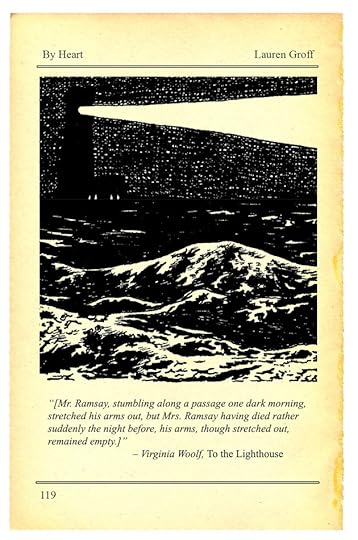

Lauren Groff on Writing With Lightness

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

Doug McLean The middle section of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse is famous for its depiction of time’s ruthless passing. As the narrative frame-rate spikes, and main characters perish as the old house falls to ruin, readers observe a time-lapse film proceed at its own dire speed—with no regard for the human wish to slow down, hold on. Lauren Groff, the author of Fates and Furies, is as impressed as anyone by Woolf’s unflinching vision, but she also sees tremendous tenderness in “Time Passes.” That Woolf reveals her characters’ deaths in tiny, bracketed asides is not a dismissal. It’s a heroic gesture, Groff says, a small, significant revolt against the way that time destroys us all—and it taught her that sometimes the biggest moments can only be done justice indirectly.

Fates and Furies, Groff’s third novel, explores a marriage from both perspective: Telling his side first, then hers, Groff shows how different lives spent side-by-side can be. Groff’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, and the anthology 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Her novel Arcadia was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She lives in Gainesville, Florida.

Lauren Groff: One August I was left alone for a few weeks in an old camp in Cooperstown. My parents wanted to fix the place up, though it would prove so decrepit that they’d soon tear it down to prevent the house from detaching from the hill and taking one slow somersault into the lake. Inside, there was a slight and constant noise that came from either the vermin eating the wood or from the phantoms I felt at night as clammy presences beside my bed.

I had just returned from a year in France; I was about to start college. None of my friends were around. I was confused, silent all day, between worlds, and I was angry because I didn’t know why I was so confused. I would read into the night to stave off the terror, and wake as soon as the sun hit the water and lifted wraiths of fog. I’d go for a run. The rest of the day I’d read on the dock, letting the sun sear my body, flipping over so the water licking through the slats would cool me off.

At some point, I picked up an old library copy of To The Lighthouse someone had bought for 25 cents. I began to read and didn’t stop until the sun had blistered my back. A mysterious rightness, a beautiful submerged truth had invaded me, one that has ever since seemed slightly beyond my grasp. This is, I think, Virginia Woolf’s intention. Her project in To The Lighthouse is to capture the fleeting nature of happiness and transfer it directly to the reader. It’s a sort of literary possession, a ghosting.

In the first part of the novel, “The Window,” Woolf makes beautiful use of the free indirect discourse in a way that is intensely, often erotically, intimate. There is great drama here—not of plot, but of promise, of thought, of looking. It’s a quite ordinary, happy day: Lily Briscoe paints, James waits to sail out to the lighthouse, Minta loses her brooch on the beach. But minute shifts within each person gather and layer, and, in layering, build. Mrs. Ramsay is the warm heart of this book; this grand Victorian mother of eight observes everyone in her orbit and every other character observes her, her great elegance, her kindness. Her daughters, even while being reprimanded by her, notice something in their mother that is like the “essence of beauty;” they “honour her strange severity, her extreme courtesy, like a Queen’s raising from the mud to wash a beggar’s dirty foot.”

The dreamy, shifting first part of the book couldn’t prepare me for the second part, the famously stunning “Time Passes” chapter. There are 10 numbered sections here, moving outward from human time, closing up the house for the night, to the house’s own vision of time as the sleepers settle in, with airs creeping in and exploring the letters in the wastepaper basket, brushing the yellow roses on the wallpaper, hovering above the sleeping faces of the humans. And then time expands even further, to envelop autumn time, with its wild and destructive winds, the “drench of hail,” the sea that “tosses itself and breaks itself.” Human time is only marked in terms of restless sleepers, until the terrible bracketed kicker, the most moving death in literature, marked only as an afterthought, a parenthetical:

[Mr. Ramsay, stumbling along a passage one dark morning, stretched his arms out, but Mrs. Ramsay having died rather suddenly the night before, his arms, though stretched out, remained empty.]

God! The bracket is a whisper, a step back into human time. Mr. Ramsay’s arms are themselves brackets for the absence of Mrs. Ramsay, who has unexpectedly left the story for good.

And then, to add to the devastation the reader feels, life goes on. There are six more sections in “Time Passes.” The house slowly disintegrates. Mrs. McNab lurches in and out, growing old herself, her vivid memories fading. The war booms not far away, explosions shattering teacups, rattling the foundations of this once-happy house. In brackets, young Prue, so beautiful and lively in the first section, dies in childbirth. In brackets, young Andrew is blown up. Dirt invades, rats invade and steal things the humans forgot. The house is on the brink of death itself; then Mrs. Bast and Mrs. McNab grunt and stomp back in to rescue what could be rescued, to clean and fix and polish it. If a few of the people in the first section return after these 10 bad years, they are not the people we want so badly to return. The world is at peace again, but irretrievably diminished.

The greatest texts, I think, first dazzle, then with careful rereading, they instruct. I have learned from Virginia Woolf, more than I even know how to articulate. Among so many things, “Time Passes” has shown me subversive ways of portraying time, of looking away from the human to the far more terrifying, far more immense texture of time beneath the minute span of a human life. Flicking from one to the next so swiftly gives an immense gravity to a beloved character’s sudden death. To bracket information is an almost unbearably intimate way of whispering it into the reader’s ear. Sometimes immense things, like war, and death, and aging, are best seen from the corner of the eye and written of only obliquely, with tremendous lightness.

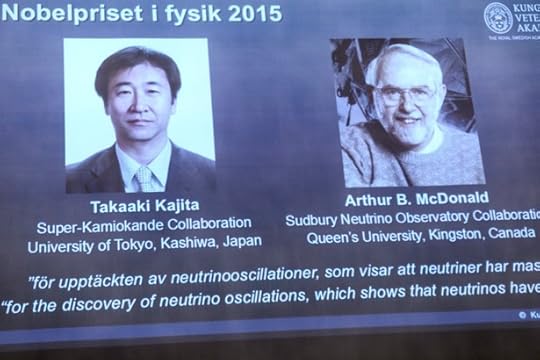

The Puzzle of Neutrinos and the Nobel Prize

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded to Takaaki Kajita and Arthur B. McDonald for their discovery of neutrino oscillations, which show that the subatomic particles have mass.

“The discovery has changed our understanding of the innermost workings of matter and can prove crucial to our view of the universe,” the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which award the prize, said in a statement.

Kajita, of the University of Tokyo, presented the discovery that neutrinos—the second-most-abundant particles in the cosmos after photons—from the atmosphere switch between two identities on their way to the Super-Kamiokande detector in Japan. McDonald’s group, at Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada, meanwhile showed neutrinos from the Sun weren’t disappearing on their way to Earth, but instead were captured with a different identity when arriving at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory.

Here’s more:

A neutrino puzzle that physicists had wrestled with for decades had been resolved. Compared to theoretical calculations of the number of neutrinos, up to two thirds of the neutrinos were missing in measurements performed on Earth. Now, the two experiments discovered that the neutrinos had changed identities.

The discovery led to the far-reaching conclusion that neutrinos, which for a long time were considered massless, must have some mass, however small.

The discovery prompted a rethink of the Standard Model of particle physics, which required neutrinos to be massless.

Kajita said he was checking his emails when he received the phone call informing him of the honor. It’s “kind of unbelievable,” he said.

You can listen to his interview upon receiving the prize here:

McDonald was awoken with news of the Nobel Prize. “As it turns out,” he said, “I did not mind.” Here’s McDonald’s interview:

The Plight of the English Soccer Manager

Whenever news emerges that a soccer club has fired its manager, the cliche most frequently spouted by fans and members of the media is that the ill-fated boss in question “just needed more time.” Brendan Rodgers, the newly sacked manager of the English Premier League’s Liverpool FC, is the latest figure to prompt this line of inquiry: The Independent’s Sam Wallace has pondered the logic of letting Rodgers oversee summer transfers only to sack him a mere two months into the season, while the former Liverpool striker John Aldridge has admitted he “thought Brendan was going to be given a bit more time to turn it around.”

Northampton Town’s former manager, Aidy Boothroyd, agrees that soccer managers do in fact need more time—only the currency required is practical hours in a day rather than theoretical weeks to implement a managerial vision. An average day on Boothroyd’s watch often included fixing a flood under one of the stadium stands, booking a training ground at a local university, and meeting a local groundsman to ensure the field was adequate: All before he could get to the “football” part of his job.

Boothroyd’s testimony comes from the British sportswriter Michael Calvin’s recent book, Living on the Volcano: The Secrets of Surviving as a Football Manager, in which the author interviews several current or very recent soccer club managers about the unique and intense pressure the job entails. The author tries admirably to humanize English soccer-club managers, who often face overwhelming (and unrealistic) pressure to succeed with limited resources. But he also reveals something of the madness inherent in the role itself. In return for the impossible promise of future success, managers are given an incredible amount of power by their clubs, with responsibilities ranging from team selection to tactical planning, motivational speaking to media relations, transfer negotiations to youth player development. As football has grown more complex in recent years, it’s clear that very few people can handle this kind of workload and expect to succeed.

The manager-as-all-powerful-leader approach generally worked in a bygone era when the financial stakes in professional soccer were lower and the player pool more local. Almost every major-league club in England today features a stand or statue commemorating a successful manager from the past —Stan Cullis at Wolverhampton Wolves, Bill Shankly at Liverpool FC, and more recently Arsène Wenger at Arsenal and Sir Alex Ferguson at Manchester United—leaders whose skill on and off the pitch led their teams to glory, in some cases for long stretches.

Club soccer in England, however, has changed considerably in the last two decades. Since the top-tier Premier League began negotiating its own rights deal in 1992, English football has witnessed an enormous influx of TV money—the league’s latest broadcast agreement with Sky Sports came to a whopping £5.136 billion, a 71 percent increase over the previous year.

While this has been a boon for some teams, it’s also raised the cost of failure. Clubs that finish in the bottom three of their respective leagues at the end of the season are forced to move down to the next competitive tier, a punishment known as relegation. This fate was once at worse a source of humiliation for most teams; now, with most clubs failing to break even to pay increasingly exorbitant player wages and transfer fees, it can threaten their ability to stay solvent. Whenever clubs endure a slump, the easiest thing for a nervous chairman now to do is to sack their struggling manager and pray the next one will do better.

This tendency is borne out by the data on average managerial tenures in England. Earlier this year, the League Managers Association released numbers that showed the average manager in England lasts 1.23 years on the job; in the Championship, the tier directly below the Premier League in the English soccer pyramid, it’s 0.83 years. Long managerial stints are a thing of the past. Calvin, in an op-ed for The Independent this past August, painted an even bleaker picture:

There were no fewer than 62 managerial changes last season [in the English League pyramid]: 47 were sacked and 15 resigned. The average tenure of a manager is less than 15 months … Fifty-six percent of first-time managers fail to secure another job.

This instability has arguably undermined the club game as a whole, with teams constantly shifting direction as they change leadership every year. Yet while Calvin paints managers as romantic figures holding out against the cruel, financially driven technocracy that is modern football, the truth is they share much of the blame for their current lot. A deeply conservative group, many are unwilling to admit the game has fundamentally changed around them and refuse to share some of their responsibilities in order to focus on what should matter most—winning the next weekend fixture.

Since the 1995 European Court of Justice edict known as the Bosman Ruling effectively outlawed foreign-player quotas for domestic clubs, player recruitment has become a complex international business involving a lot of moving parts. To add a new player, clubs must deal with a host of intermediaries including agents, managers, board members, and others. Worse, as club football gets richer and transfer fees and wages keep increasing, mistakes in player recruitment are getting more and more costly. Avoiding mistakes is for some clubs a full-time job.

That’s why many teams have opted for the continental “director of football” role, meaning a more long-term appointee who partners with a manager and focuses full-time on budgetary matters, including player recruitment. When the model works, a director of football will work in tandem with the manager to allow them to focus more on the day-to-day preparations of the first team.

While the director of football role has been adopted by several English clubs in various forms over the last few decades, many managers still resist it, refusing to concede even the slightest bit of control over player recruitment. When the Premier League club West Bromwich Albion—which had employed a director of football for some time—hired the manager Tony Pulis for example, it gave him total control over transfers, effectively undoing its recruitment model. The Queens Park Ranger director of football Les Ferdinand has also hinted at some pushback from the team’s manager, Harry Redknapp, over his own appointment: “I suppose managers get a bit paranoid,” Ferdinand recently told The Guardian. “But this wasn’t done without Harry knowing. I spoke to the owners and made sure Harry was happy with me coming in. I wasn’t here to take Harry’s job or tell Harry what to do. I was here and I am here to help the owners get this football club back to where it wants to be.”

“Data might help you narrow the margin of error, but the decision is still a feeling. It’s a gut instinct.”There’s another area too where managers have rejected a tool that might help them be better at their job: the burgeoning field of soccer analytics. Amid concerns about “boffins” reducing the game to spreadsheets, managers will constantly reiterate the primacy of the human touch. Speaking to The Guardian last year, the Everton manager Roberto Martínez warned that feeling, not data, had the final say in his team selection.

“When you see a player,” Martínez argues, “you’ll watch his warm-up, the way he speaks to the referee, the way he speaks to other teammates after missing a chance, the way he celebrates a goal, the way his teammates react when he scores. Data might help you narrow the margin of error, but the decision is still a feeling. It’s a gut instinct.”

What managers may not realize is the chairman’s decision to sack them is also often a gut instinct, born out of fear and an inability to discern the difference between a poor run of luck and incompetent management. But this is where statistical analysis can clear the fog a little. Converting shots to goals for example is a notoriously messy business, and more often the result of chance than intention. There are several ways in which good analysts use that information to tell the difference between an unlucky streak and a true slump.

Armed with this kind of data, managers could ward off nervous chairmen with reassurances the tide will turn, or at least provide them with concrete evidence of areas where the team needs improvement that goes beyond simply firing the person in charge. In the end, some chairmen might be induced to take their finger off the trigger and trust that this too shall pass. That might eventually take some of the pressure off the person in charge so they can take the kind of daring risks that are sometimes necessary to win.

By accepting help with player recruitment or in data analysis, managers might be able to get back to what Aidy Boothroyd called “the football stuff.” He, like most of the figures interviewed by Calvin throughout Living on the Volcano, seems to strongly echo the words of the Chelsea and Feyenoord manager Ruud Gullit: “Being a football manager is no fun at all. You have to put up with all the hassle. It is not surprising that so many turn grey or have heart attacks. I enjoyed working with the players, creating the team—that was fun. But all the rest I hated.”

Today, “the rest” is simply too much for most English soccer managers to handle; thankfully there’s help available, if only they’ll put pride aside and accept it.

October 5, 2015

Edward Snowden Says He'd Go to Prison to Come Home

Edward Snowden isn’t the spy who came in from the cold, but he might be edging slowly toward the warmth.

In an interview with the BBC, the beloved and reviled whistleblower said he’d presented concessions to the U.S. government in an attempt to return to his home country from Russia. “I’ve volunteered to go to prison with the government many times,” Snowden said, according to The Guardian. (The BBC program is not viewable in the U.S.) What I won’t do is I won’t serve as a deterrent to people trying to do the right thing in difficult situations.”

But his overtures haven’t been met with any concrete plea offers: “We are still waiting for them to call us back.”

Former NSA boss Michael Hayden gave the BBC a typically hardline answer, saying, “If you’re asking me my opinion, he’s going to die in Moscow. He’s not coming home.” But there are signs both sides have softened a bit. Shortly after leaving office, former Attorney General Eric Holder told Michael Isikoff that Snowden had sparked an important discussion about surveillance. Holder seemed to signal the Justice Department might be thinking about some sort of plea deal for Snowden: “I certainly think there could be a basis for a resolution that everybody could ultimately be satisfied with. I think the possibility exists.” However, Holder’s successor Loretta Lynch said the U.S. government hadn’t altered its position.

The position Snowden laid out to the BBC would appear to represent a softer view, too. After Holder’s comments in July, Snowden’s lawyer Ben Wizner applauded Holder for his openness, but rejected even his hypothetical ideas. Wizner said Snowden wouldn’t accept any deal that involved a felony plea and prison time. “Our position is he should not be reporting to prison as a felon and losing his civil rights as a result of his act of conscience,” he said.

In March, former General David Petraeus struck a plea deal with prosecutors in a leak case, derided by many observers as evidence of a double-standard for different kinds of leakers. At the time, another of Snowden’s lawyers, Jesselyn Radack, said her client would accept a similar deal.

The Justice Department didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment on Snowden’s remarks. While it’s hard to parse these lawyerly statements and bluffs, one could easily read the last few months as having brought the two sides closer together on a possible arrangement. But closer and close enough are not the same thing.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower