Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 324

October 13, 2015

Jason Rezaian’s Ordeal

From the get-go, it seemed apparent Iran’s imprisonment of Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian on espionage charges wasn’t about an actual crime.

For well over a year, the dual Iranian-American citizen has been held for vaguely defined crimes in one of Iran’s most infamous prisons. He was only allowed to meet with his attorney once before he was tried in a closed-door trial. If you need a refresher on Rezaian’s treatment, here is The Washington Post’s editorial board in July:

Though Iranian law limits such treatment to 20 consecutive days, Mr. Rezaian was held in solitary for 90 days or more. Also illegal was the failure to bring formal charges against Mr. Rezaian for more than five months and the severe restriction of his legal representation. Iranian law says no person may be detained for more than a year, unless charged with murder; yet Mr. Rezaian remains imprisoned.

On Sunday evening, two months after the final hearing, the Iranian judiciary confirmed that Rezaian had been found guilty. Details about sentencing and the evidence against him remain scant, though as my colleague Krishnadev Calamur noted in August, Rezaian could face a 20-year prison sentence.

Earlier, some hopes were pinned to the idea that Rezaian might have represented a bartering chip for Iran as it worked to hash out a nuclear deal with the United States and five other world powers. The deal went ahead and so did Rezaian’s imprisonment leaving one lingering question: If Rezaian’s ordeal was all for show, what is Iran or its judiciary seeking in delivering a guilty verdict now?

Noting Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s comments during an interview with 60 Minutes last month, Thomas Erdbrink at The New York Times, offers the theory that Iran is seeking a prisoner exchange with the United States.

“I don’t particularly like the word exchange, but from a humanitarian perspective, if we can take a step, we must do it,” Rouhani replied about a possible prisoner swap, adding, “The American side must take its own steps.”

Yet, over at The Wall Street Journal, Haleh Esfandiari sees Rezaian’s conviction as a notice of warning from Iran’s hardliners to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani:

By finding Mr. Rezaian guilty, Iran’s security agencies and judiciary are effectively warning Mr. Rouhani. They know that this conviction will strengthen those in the U.S., including members of Congress, who are skeptical of President Barack Obama’s outreach to Iran; and they will continue to try to obstruct Mr. Rouhani’s outreach to Washington. The conviction is a way of saying that they are not subject to Mr. Rouhani’s control.

Whatever the real reason, the ordeal is far from over.

Democrats Roll the Dice in Vegas

The Democratic candidates gathering in Las Vegas on Tuesday for the party’s first presidential debate face a nearly impossible bar when it comes to entertainment.

The Republican debates so far have been nothing if not fun. Enlivened by the performance-art politics of Donald Trump, the occasionally substantive affairs have benefitted from the clash of big personalities and the odd tension created by cramming so many candidates on one stage. The result is simply good television, and ratings gold for Fox News and CNN.

For better or worse, the Democrats are a much soberer bunch. Hillary Clinton is the ultimate play-it-safe front-runner, her efforts at humor and spontaneity cruelly undermined by her campaign’s inexplicable decision to telegraph them. Bernie Sanders has energized the party’s base, but his pledge to avoid attacking Clinton has made the Democratic primary campaign both more polite than the GOP side, and also more dry. Martin O’Malley just can’t seem to get anyone’s attention, while Jim Webb and Lincoln Chafee hardly appear to be trying.

Naturally, the most fascinating Democratic hopeful heading into Tuesday's debate is the one who won’t be there. Vice President Joe Biden’s indecision has officially put Mario Cuomo’s Hamlet act in 1992 to shame. Trying to juice interest in the debate, CNN made it known that Biden could claim his spot on the stage by declaring his candidacy at the very last minute—the debate begins at 8:30 p.m. Eastern—and the network even kept a podium on standby in case he did. (Reports are that Biden has no intention of being in Las Vegas.)

What the Democrats lack in pizzazz on Tuesday they could very well make up for in substance.Yet what the Democrats lack in pizzazz on Tuesday they could very well make up for in substance. Clinton will undoubtedly be forced to explain her opposition—announced last week—to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade agreement that she called “the gold standard” when she worked on it as secretary of state. Sanders will likely be challenged on his stance on guns, which might be the one issue on which he has been to the right of the party base.

Clinton’s strategy will also be interesting to watch. Will she take the traditional frontrunner’s route of focusing on Republicans and pretending her Democratic rivals aren’t even there? Or will she engage Sanders and try to paint his spending-heavy proposals—and by extension his entire candidacy—as unrealistic? O’Malley, the former Maryland governor who heartily campaigned for Clinton in 2008, has become the Democrat most willing to criticize her directly. Will he stick to policy on Tuesday, or will he make the case that Clinton’s email troubles have undermined her electability in 2016? And to what extent will all three of them embrace or distance themselves from President Obama's record domestically and overseas?

Webb and Chafee are the true wild cards. The former Virginia senator has barely registered in the polls, while Chafee is a Republican-turned-Democrat who figures to sharply criticize Clinton on foreign policy. Both have neither past ties or loyalty to the Clinton family nor anything to lose in the campaign, raising the likelihood they could toss rhetorical grenades her way. (No strategy spoilers from Webb, the former Navy secretary: “Eisenhower didn’t yap about D-Day in advance,” a spokesman told Time.)

Expectations for the debate are fairly low. Playing pundit for a night, Trump has declared that the Democratic face-off will be “boring,” but since he can’t fathom the idea of missing out on the action, he plans to live-tweet the whole thing. Even CNN has said it expects lower ratings than for its record-setting Republican debate, and those could be further hurt by competition from the high-stakes playoff game between the Mets and the Dodgers.

For Clinton, and the Democratic Party more broadly, the goal of a debate is not entertainment—even if the debate is in Las Vegas. But they do face a related imperative on Tuesday night, and that’s to at least begin to generate excitement among Democratic voters who have either been turned off by Clinton’s never-ending email drama or by a policy agenda that has been thoroughly blocked by Republicans in Congress. It says something about the dynamics of the race that while Republicans have already begun to winnow their field of contenders, Democrats are still talking about growing theirs. Clinton might be concerned at the moment about holding off Sanders, and keeping out Biden, but she can’t afford to alienate their most passionate supporters and leave half of the party demoralized next year. Even if Democratic voters don’t need to be entertained, they do need to be enthused.

Make It a Double: The World's Two Largest Brewers Agree to Merge

It’s time to pop open the champagne of beers, as the world’s two largest brewers celebrate a merger deal.

A week after SABMiller rejected a takeover bid from AB InBev, the world’s largest brewer, the two companies have agreed in principle to merge, creating a beer behemoth. That’s the culmination of about a month of talks between them. Last week, AB InBev went public with its frustration after three bids prior were rejected. While SABMiller’s board remained aloof, Altria—the American tobacco giant that is SABMiller’s biggest shareholder—issued a separate statement in favor of the deal.

On Tuesday, Altria (along with BevCo, another large shareholder) got its way, but the deal also required AB InBev sweetening its offer, giving SABMiller a slightly higher offer per share; the final deal will be worth $104.2 billion. Altria and BevCo will receive a special kind of share, locked up and non-tradeable for five years, which will help them dodge a tax bullet. Other shareholders can take cash or the same deal.

Related Story

The World's Two Largest Beer Makers Brew Up a Merger

A partial list of the beers the deal will bring under the same roof would fuel a raucous weekend on any college campus: Bud, Bud Light, Corona, Michelob, Stella Artois, Becks, Hoegaarden, Leffe, Coors, Coors Light, Grolsch, Icehouse, Keystone, Milwaukee’s Best, Blue Moon, Foster’s, Pilsner Urquell, Peroni, Miller Lite, and High Life.

Analysts have long felt that a merger between the two companies was just as inevitable as regretting that Raz-Ber-Ita. The world beer market has been consolidating, and slowing economies in some of the places where the market has expanded most in recent years—especially Brazil and China—means brewers need new ways to grow. A map of beer dominance in both South America and Africa looks like a patchwork quilt, with SABMiller and AB InBev strong in different regions. A merger will allow them to exercise more influence across the map.

Shares in both companies rose on news of the deal. Like all the best celebrations, though, this one may leave the partiers with a hangover. While a merger will provide new reach and economies of scale, regulators in the U.S. and Europe may have reservations about the size of the combined company and force it to shed some holdings before approving the deal.

According to a Reuters report Monday, AB InBev may already be in American antitrust regulators’ sights. Craft brewers allege that as their market share grows, AB InBev is trying to hobble them by purchasing beer distributors, which creates a barrier between brewer and market that no amount of hopping—dry or otherwise—can overcome. The Justice Department has begun investigating the claim, and AB InBev confirmed to Reuters that it’s talking to regulators. Like other major brewers, AB InBev has tried other methods to tap into the craft market—notably buying up smaller brewers, including Goose Island and Blue Point.

But all that is a worry for tomorrow. Tonight, drinks are on Altria.

Whither Guantanamo Prisoners?

Pentagon officials are in Colorado this week to scope out potential sites to house prisoners at the U.S. detention center in Guantanamo Bay, the Associated Press reported Monday.

A team of officials will evaluate the state penitentiary in Canon City and the Federal Correctional Complex in Florence, which has been dubbed the “Alcatraz of the Rockies,” according to the AP. Pentagon spokesman Navy Commander Gary Ross called the visits “informational.” The Pentagon previously looked at the Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and the Naval Consolidated Brig in Charleston, South Carolina.

The scouting is part of the Obama administration’s plan to close the military prison in Cuba, which houses detainees captured in the war on terrorism. It’s an attempt to answer the big question surrounding the potential closure of Guantanamo: Where? Where should the prisoners—half of whom are no longer considered a security threat and have been cleared for release—go?

President Obama has vowed to shut down the facility since he was first elected; he issued an executive order calling for the prison to be closed within a year during his first month in office. That deadline came and went, and the White House’s proposed road to shutting down the prison has been rocky since. In December 2009, Obama signed a presidential memorandum ordering then-Attorney General Eric Holder and Defense Secretary Robert Gates to acquire an Illinois state prison as a replacement for Guantanamo. In May 2010, Congress blocked funding for that prison, and banned the use of federal funds for the transfer of prisoners to American soil. In January 2013, the State Department closed the office responsible for handling the closure of Guantanamo. Polling shows most Americans say the U.S. shouldn’t close the detention center.

But the U.S. has slowly transferred some of the detainees at Guantanamo to their home countries—or other countries that will take them. According to a New York Times database, 55 countries have accepted Guantanamo detainees; most have gone to Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan. Six detainees were transferred to Oman in June, and one detainee, whom U.S. officials say was a close associate of Osama bin Laden, was repatriated to Morocco last month. The Obama administration is avoiding Yemen, where most of the detainees are from, citing the tenuous security situation there. As my colleague David Graham wrote last month after the latest transfer, “one sticking point has been recidivism: How likely are former prisoners at Guantanamo to return to the field as terrorists? There’s disagreement, with Republicans saying it’s as high as 30 percent of the 620 released detainees. The administration’s estimate is much lower.”

U.S. Defense Secretary Ash Carter has acknowledged the difficulty of transferring the prisoners, saying last month: “If they’re detained at Guantanamo Bay, fine. I would prefer to find a different place for them.”

He then added: “But we have to be realistic about the people who are in Guantanamo Bay. They’re there for a reason.”

The current prisoner population of Guantanamo Bay is 114.

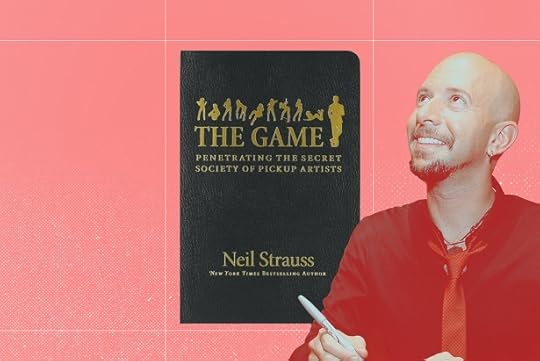

The Game at 10: Reflections From a Recovering Pickup Artist

When Neil Strauss’s blockbuster book about pickup artistry came out a decade ago, I was a Midwestern ingenue in New York City, and I read it mostly as a defensive measure. A nice Ph.D. student named Jon had mentioned The Game, and was demonstrating how it worked by means of “The Cube” routine, where you ask a woman to imagine a box standing in the desert, and you tell her about herself based on how she describes it. (The cube represents the woman’s ego or something—so if it’s big, it means she’s self-confident; if it’s transparent as opposed to opaque that means she’s open as opposed to guarded; if it’s pink that means she’s bright and energetic … basic non-falsifiable horoscope-type material she can read herself into and then find you perceptive.) It was basically a way to harness people’s love of talking about themselves in order to score.

It seemed like dangerous stuff, in that it might actually work. Another tactic, one for which The Game became particularly famous, was the art of “negging”—that is, giving a woman a semi-insulting compliment so that you a) distinguish yourself from the pack of people she’s accustomed to have hitting on her, and b) slightly lower her self-esteem to the point that she wants your approval and is vulnerable to your advances. This is a subtle thing, and it’s not the same as being bluntly mean. If you tell a girl she’s busted, you are a jerk. If, however, you say something like, “Those shoes look really comfortable,” you may have started a conversation, even if the response is, “They’re not. And what the hell is that even supposed to mean?”

Related Story

That’s how I ultimately read the book—the tactics were about starting conversations with people you had no business talking to. Any way you could do this—and there were lots of bizarre techniques with goofy names, like “peacocking,” where you might wear an outlandish hat to give people something to comment on—helped you get the access you needed to try to convince someone to sleep with you. Obviously, it was important not to seem desperate while applying these very detailed rules you learned in a self-help book. (Sample: Do not make a move until you get three IOIs, or Indicators of Interest, such as a slight touch on the arm.) Indeed, the neg itself could be seen as a way to address the problem that sometimes the best way to get a gal’s attention is to ignore her. If she doesn’t notice you’re ignoring her, then you’re both just standing there not talking to each other. Solution: “You have eye crusties. No, don’t rub them. I like eye crusties.” That’s a direct quote. Swoon.

It’s been 10 years, though. Tinder has happened, Strauss is older, and he knows not all of the book ages well; he now calls some of the techniques he documented—and used—“objectifying and horrifying.” He’s married to a woman he loves very much, for which his pickup-artist friends of yesteryear might accuse him of having a case of “one-itis.” For The Game was also a numbers game: Hit on enough women and eventually one of them was bound to succumb to your advances. If anything, Tinder has only facilitated this probability-based approach to courtship, but Strauss’s new book, The Truth, is about how he ended up settling down and making peace with the fact that you can’t be monogamous with everyone. What follows is a condensed and edited transcript of a conversation I had with him recently.

Kathy Gilsinan: It’s hilarious that this interview got postponed a couple of times. That just made me want it more.

Neil Strauss: I know. How appropriate, right? That was the plan.

Gilsinan: So that worked. I was surprised when I first read [The Game] that in addition to being a sort of how-to manual for picking up women, it’s kind of a Neil Strauss coming-of-age story.

Strauss: Yes, totally.

Gilsinan: If I read it right, you start out scared to talk to women, you learn all these techniques and score a lot, and then, to spoil it, you meet this woman for whom none of it works and you fall in love and swear off your player ways.

Strauss: Yes that’s exactly it. I think more people have heard about The Game than have actually read it. I don’t think I’ve gotten any angry emails from people who’ve read it, per se.

Gilsinan: Why were people angry about it?

Strauss: Obviously I was a journalist, this community [of pickup artists] already existed, and I went in to describe my experience of it. But because no one had even heard of this world, and the techniques, let’s face it, are so objectifying and horrifying, that the book became the bible of what it was trying to chronicle in a more neutral way. So I think all of a sudden there were these horrid ideas that people read about in The Game and ... The Game became the origin of those ideas.

Gilsinan: It’s interesting you say almost regretfully that it became the Bible, because it was marketed that way, right? I have a copy that’s on my desk that has [gilt edges], it has a red-ribbon bookmark.

Strauss: You make a good point. It was designed by my publisher at the time like a Bible. So it is like the book’s asking for that.

Gilsinan: But it’s interesting too, given the way the book ends, with you meeting this woman who is not impressed by any of this stuff, and then you end up with her. What do you think that says about the utility of the techniques for banging lots of women versus finding someone who likes you without your having to use tricks on them?

Strauss: Yeah, so if you’re going to talk to me today about it versus then, right? If you talked to me then about it, I would have defended the techniques as a way to learn courtship. If you ask me today about it, I’d tell you that anything that involves manipulation or needing to have a certain outcome is definitely not healthy in any way.

Gilsinan: So 10 years later, why did you change your mind?

Strauss: It isn’t that I changed my mind. You said The Game was kind of a coming-of-age tale, but it was like coming to the age of adolescence at a late point. And I think The Truth in a way was coming to adulthood at a late point. Let’s just face it, I got so deep into that community and was seduced by it that I completely lost myself in it. It happens in the book. Why did I really stop writing for The New York Times, hang out with all these kids running around, you know, the Sunset Strip like a maniac in stupid clothing? I see those photos and I vomit in my mouth a little bit.

“Even when I wrote it, I didn’t think it would be a guide. I thought it would be a book about male insecurity.”I even knew then that it was about low self-esteem. Even when I wrote it, I didn’t think it would be a guide. I thought it would be a book about male insecurity. But now coming out of the other side of it, I can see how there were maybe unconscious forces operating on me that made me so obsessed, and even when I thought “the game” was over, that it still had this hold on me.

Gilsinan: It’s amazing to think of such a book coming out now and what the reaction to it might have been. I think it would have been a lot louder.

Strauss: That’s so true. It’s more controversial now than when it came out, and I think that’s a good thing for society.

Gilsinan: A lot of the criticism was, well, men are afraid of women’s sexuality, and the response to that is, yeah, obviously. That’s not a new thing. To me at least, that’s entirely why this pickup community exists. It’s all about getting over fear of talking to humans.

Strauss: That’s exactly it. And I’ll go one deeper. To me, the biggest shock of my life, was how, myself who wrote The Game, Robert Greene who wrote The Art of Seduction, Tucker Max, who, well, is Tucker Max—what do we all have in common?

Gilsinan: What?

Strauss: We all have narcissistic mothers. So what happened? What happens when you grow up with your identity being squashed by this mother who never sees you but only sees herself, is you grow up with a fear of being overpowered by the feminine again.

Gilsinan: Whoooaa.

Strauss: Right? And so at that level you realize The Game was about being in this power relationship—ok, you’re safe because you’re in control, you’re not being vulnerable. Even the relationships you get in are maybe with people you feel safe with because you’re in control. There’s no way you can have intimacy from that. So when I would do seminars [about The Game], I would say, let me ask you, how many people here were raised with a narcissistic or dominant mother figure? Every time it was about 80 percent of the room. And then when you start to realize, ok, this has nothing to do with the world, it’s just me, I’ve got to get over it—that’s when everything kind of changes.

Gilsinan: How did you come to that realization? Was that a product of therapy?

Strauss: Yeah. I’ll never forget the moment. I met a great woman and we were in a great relationship. And I cheated on her. I got caught. And I felt so bad. I thought I was a nice guy, I really did, you know? And I thought, how can I break the heart of, how could I hurt somebody who loves me and be so selfish? So I checked into sex addiction rehab. And that’s what The Truth is about. Even when I was there, I was cynical about it. Of course there was a dominant therapist to quote unquote emasculate me, so of course it was rough for me. And then there was a moment where I told her the story of my childhood. And she said, “Well no wonder you can’t be in a relationship.” And I said, “Why?” And she goes, “Because you’re in a relationship with your mother.” When she said that a whole wind blew over me. It was like a movie. All of a sudden your whole past story just snaps into line and I saw who I was. Before that I really thought I was healthy, I had parents who loved me, they were never divorced, I had a good childhood, and all of a sudden she saw the story I didn’t. And that was the moment everything changed.

Gilsinan: And the reason there’s an entire book that takes place after that is because seeing the problem is not the same as solving it, right?

Strauss: Oh, you’re so good! Yes.

Gilsinan: Stop it! I know what you’re doing.

Strauss: No, thank you. If it was a movie, it would have been, act out sexually, go crazy, go to rehab and get better, but in real life—and it drove me nuts with the book, too—it’s true, I went to rehab, I found everything that was wrong with me, understood it, and still kept engaging in the same horrible bad behavior. So the knowledge is not enough.

Gilsinan: One of my favorite moments [in The Game] is towards the end, where one of your friends in the pickup-artist community starts to dissect your game. A lot of it is asking questions and treating people like they’re interesting. And you have this realization where you’re like, no wait, that’s my personality. Any time you have to learn techniques to get people to do stuff they wouldn’t ordinarily do, you can start to lose track of where you end and the game begins.

Strauss: It’s true, that’s when I went to such an extreme that everything’s a technique. The guys would practice taking photos with each other to see how they could look more dominant in a photo. They engineer their behavior to such an insane degree.

“The guys would practice taking photos to see how they could look more dominant in a photo. They engineer their behavior to such an insane degree.”Gilsinan: I’m reading this book 10 years ago as a female person. It did have the sort of hopeful implication, that everyone’s afraid to talk to attractive people and just to strangers more generally, but you can follow this set of rules and you’re basically guaranteed to get laid. But I remember asking a male friend at the time if there was an equivalent set of rules for women. Like surely there are female-specific tricks to, in effect, manipulate people into sleeping with you. And his response was, verbatim, “Be hot.” And I think that’s kind of true. Men don’t like being negged in my experience. But maybe I’m doing it wrong? What do you think?

Strauss: To answer the first part of what you were saying, I think yes, getting over social anxiety is a great thing. But the problem is wanting the outcome. If you take away wanting the outcome, it’s nice to have ways to get over social anxiety, but manipulating toward an outcome from someone is where it gets dicey. Because obviously if you’re trying to get something from someone—it doesn’t even have to be an outcome like sex, it could be self-esteem—when you talk to somebody who’s needy, where they’re just being funny and entertaining but they just need a response to feel better about themselves—

Gilsinan: I don’t identify with that at all ...

Strauss: Exactly. It becomes like hits of crack, whether it’s laughter or sex or admiration or fame or money, all those things—I can speak to the sex part—don’t end up making you any more happy than you were without them. But you have to work on it from the inside before you can get to them in a healthy way.

To speak to the second part of it, today, I don’t think it’s actually about male-female, I think it’s about relative status. I’ll give you an example. When Dave Navarro [formerly of the Red Hot Chili Peppers] read the book, he got so excited about negs, he thought they were the funniest thing ever. So some woman would walk up to him and say she loved his music, and he’d say, that’s a great shirt, where did you get it from, the Grand Canyon gift store?

Gilsinan: Oh, that’s a good one though.

Strauss: And he wouldn’t pick that woman up. They’d just be like, what an asshole. So I think a lot of The Game is about relative status. [If your] status is lower in that moment, it’s like, how can I make it equal to [hers] or higher. The answer is that if your status is higher, if you’re not making someone feel good about themselves, you’re a jerk. But today, you’re a jerk no matter what if you’re really out there thinking about status. If you’re out there thinking about what your relative status is you can be guaranteed that it’s lower than everybody else.

Gilsinan: Now that you’re married with a kid—and is that a daughter by the way?

Strauss: A son, but everyone asks that. It’s like somebody’s like, is there a God?

Gilsinan: Could you talk a little bit more about your perspective on the book’s cultural impact? What are your regrets? Do people cite you as inspiration for specific things that you find abhorrent?

Strauss: I definitely don’t have any regrets for two reasons. One is that I really wrote it honest to my experience, and to what I saw and to what I thought were the good and the bad. The second one is, for me, it opened up a door to incredible self-improvement, that I wouldn’t be here, married with a child and my wife, if it wasn’t for The Game, which led to The Truth which led to this great, joyful fatherhood. I really, like, it sounds cheesy to say but I’ll be there with my wife and my son and look around and be like, oh man, I’m so happy, I’m just so lucky, I feel so good. I’ve never been in a place where I just have everything I needed. I just don’t want to lose the stuff I have.

And there were also plenty of people—and people come up to me all the time, who’d read The Game, and had a great path, even better than mine. And The Truth even begins with one of those guys, and they met somebody and fell in love and had a family, and they didn’t get compulsive about it like I did. I suppose it’s one of those books where it’s like a forking path, depending on who you are coming to reading it.

Gilsinan: Do you think that kind of thing is because of The Game or in spite of The Game? You sort of build self-esteem throughout the book but the way you’re able to make it work at the end with Lisa [his girlfriend at the end of that book] is that you sort of jettison a lot of what you had learned. So I’m wondering if the guy you meet at the beginning of The Truth, he meets his wife, but was it [because of] The Game or was it something else?

Strauss: Obviously in my journalistic life, I’m just a big believer in free speech and art not being censored no matter what it is, and I don’t think a book is responsible for someone’s behavior. That’s already sort of part of them for sure. For me, it spoke to a wound of mine that already existed before. These things activate and polarize people. People already exist and they find their communities. I guess people use books like the Bible and other religious texts as excuses to murder other people, but I don’t think those books make them do that.

Gilsinan: Fair enough. So I reread The Game recently, and not all of it ages well. Some of it ages okay.

Strauss: Tell me, I’m curious. Oh God, maybe I don’t want to know. No, tell me. It’s like looking at the photograph of yourself like in high school when you’re awkward and you don’t want anyone to look at it but you don’t want to throw it out either.

Gilsinan: I don’t know about you, I peaked in high school. But it goes through all these different techniques, and The Game focuses on the “Mystery Method” but there’s also like Ross Jeffries, who hypnotizes people, kind of, and it’s weird, and one thing that I don’t think would age well in the Twitter era, there’s one description of a guy whose thing is to just gradually escalate physical contact and his motto is, “let the ho say no.”

Strauss: But even then, I was putting that in to show the extremes. I would hope that at no time is that ever okay in history. I guess the answer is, then it was horrifying. But now he wouldn’t be able to get out of bed without rocks being thrown through his window.

Gilsinan: And then there’s other small stuff, like one guy whose signature move is to bring women home to look at his WinAmp media player with him.

Strauss: That’s awesome, no way. I used the word ‘WinAmp’ in a book. Wow that dates it.

Gilsinan: But like, the equivalent today is “Netflix and chill,” right? But I’m wondering, aside from some of the abhorrent techniques that you’ve sort of disavowed, are there any principles you think apply in the Tinder era? These are problems that people are still trying to solve.

Strauss: Yeah, I think part of that hysteria around The Game is really that I was in this culture and I was reporting what I saw, whether it was good or bad. And I think that’s what you do obviously as a reporter. If I just said the acceptable parts of a community it wouldn’t be an honest nonfiction account. So for sure, now that you’re mentioning these things, I think that there was a journey through all these characters as a reporter, and not to confuse the reporter with a message per se. That said, I think the techniques themselves on a base level are all pretty timeless. It’s like the same ideas were in Ovid’s The Art of Love and are in the classic texts like The Art of Seduction. If you go to Aziz Ansari’s new show, where he grabs people’s texts and reads their phones, you can see them making the same mistakes.

And honestly there are things that all people should really understand, which is being able to see the social conventions and rules by which people operate and understand them is a good thing, so that when on Tinder or in text someone’s giving you a hint to ask them out, and you’re not getting that after four times, they kind of give up on you as an idiot. So it’s good to see that. And it’s good to know how to start a conversation and be interesting and it’s good to know the signals. Before The Game, I think women were interested in me and I just didn’t realize it. I thought, why would they be interested in me, they must do this to all the guys. So I think the understanding is great, to that degree. And I think it’s a nice dichotomy, the difference between understanding the rules and then trying to bend and distort them for your own gratification.

Gilsinan: So take a reader through. What are the top IOIs [Indicators of Interest]? For those of us who haven’t read The Game.

Strauss: I’ll tell you my favorite one. When you make a joke that’s not funny, and nobody laughs except that one person at the table, and then you know—they like you. That’s the most beautiful one.

Gilsinan: But what if you think you’re funny?

Strauss: I tell you what, if still no one’s laughing but that one person, then only you and they think you’re funny, and they’d probably be a great partner.

Gilsinan: There was just a thing making the rounds on the Internet, the rule that you get two questions. Did you see this, on Gawker? It was written from the perspective of somebody being approached, and it said basically, don’t keep asking me questions if I’m clearly waiting for my boyfriend while I’m by myself at this bar. You can ask two questions and if I don’t ask you another question back, then stop talking.

Strauss: That’s funny—I like that, that’s really smart. And that was another IOI. To stop talking, and if they say, “So....” and continue, then that was a sign.

Gilsinan: Do you think three is a good rule for IOIs?

Strauss: I guess the answer is, once you get more comfortable with yourself, you kind of let go of those things. Honestly, I think the real answer, God this is going to sound, I know I’m—is just learning to trust and listen to your intuition. And I’m not just saying this now as the older guy talking about this book 10 years ago, but I think that’s eventually what I learned to do. I would just be with someone. I remember being on dates when I was just learning this and I didn’t know if they liked me or not. And I’d exit, I’d go to the bathroom, and I’d close the door, just sort of stand there and ask myself, is she into you? Does she like you? Does she not like you? And I’d just try to listen to myself and pay attention and I’d get a yes or a no.

And I talk a lot with a lot of artists about creativity and making music, and they say, it’s the same thing, it’s getting in touch with your intuition. So I think maybe these were sort of, if they’re sort of training wheels that allow you to be comfortable with yourself, then that’s the positive side of it. Even while I was doing The Game, there was a point where you just start to know. But I guess I was so socially awkward that I had to make rules first. I think anything with rules is probably eventually wrong, because there’s probably no real rules for social behavior that are ever always right.

Gilsinan: That’s such a bummer because that was the whole value proposition of The Game, to me at least.

Strauss: Here’s an example, even in The Game. There’s an idea of never buying somebody a drink. I remember, I was on a date with someone and I was just so excited to be with her, she was just so great. We each had one drink. The bill came, and it got awkward. I’m like, I’m never supposed to buy her a drink and now I have the bill, what do I do? Then I said, let’s split it. It was for two drinks, and I looked like such a cheap douchebag. That was a case where I just should have said, it’s no big deal to get it. The idea is that there are rules, but the real idea is that there are reasons why those rules exist. If you understand the reasons, you can throw out the rules and recognize that they’re just guidelines.

“The real idea is that there are reasons why those rules exist. If you understand the reasons, you can throw out the rules and recognize that they’re just guidelines.”Gilsinan: So you would probably stand by some of the basic principles, that you don’t have to be afraid to talk to people, that kind of thing? It sounds like some of the things you object to in the former work is just the tactics, right, but not necessarily the overall message, which is have better self-esteem, what are you so afraid of, talking to people?

Strauss: Yeah exactly. I stand by the book, I still love the book, though I can’t guarantee it because I haven’t read it in 10 years—but I think I do. But I stand by it because it was honestly who I was at the time. What I maybe have more issues with—and I already had issues with the community then—I think they’re even stronger now because I see the unhealthy compulsions behind it, and also maybe more against the rationalizations for manipulation that I’ve spoken since then. To be honest, I mean I’m so glad I feel differently because that means I’ve grown and changed and there was a point to writing another book.

Gilsinan: I too have aged since I read The Game, you have aged, a lot of my bros who I read The Game with back in the day are married or on their way there. Are there game principles, if not techniques, that you can use in your marriage to get out of chores and stuff?

Strauss: I think that The Game is a rite of passage for dating and The Truth, to me, is a rite of passage for relationships, so there is absolutely no point in my relationship where I ever use The Game.

Gilsinan: Do you hear that, Ingrid?

Strauss: Exactly, do you hear that, Ingrid? Because part of The Game is that you have a hidden intention. And I think part of a relationship is really opening up your life to the other person, the good and the bad, and being comfortable with that. So the answer is that if you don’t want to do the chores, you sit down and have a conversation about it.

Gilsinan: What? That’s such a disappointing answer!

Strauss: But here’s the cool part of the answer. Here is what I do. There’s something called non-violent communication, created by Marshall Rosenberg, who recently passed away. It’s The Game for relationships, because it’s a way to communicate and be heard and be understood without requiring an outcome. I think the issue with The Game is requiring an outcome, having that hidden intention, but the great thing about non-violent communication is it’s the way to communicate without bringing all your baggage, all your shit into it, and having an outcome that’s bringing you both closer together.

So the answer is that there are tactics in The Truth, but I feel like they’re good ones. In The Game, obviously a lot of my stuff came from low self-esteem, surprise surprise. And I had very critical parents, and you know, the narcissism. So before my son was born, I wrote him a letter that said, hey I just want you to know, your mother and I love each other so much, and we made this decision to have you, and you were born out of love, and you’re wanted, and this is the story of how you came into the world. Just before he was born I put it in an envelope and sealed it, sent it to him at our address and now it’s just sort of sealed in a folder for when he’s older, to know that whatever happens he comes from a foundation of love, of being loved and being wanted.

I think that’s what we lacked in The Game, and [what] we went out to find from other people.

October 12, 2015

Hollywood Comes for Volkswagen

Less than a month after Volkswagen’s emissions cheating was exposed, Hollywood is ready to make a movie about it.

Paramount Pictures and Appian Way Productions, which is run by actor Leonardo DiCaprio, have acquired the rights to a forthcoming book about the scandal, The Hollywood Reporter reported Monday. New York Times journalist Jack Ewing signed a six-figures deal for the book with publisher Norton earlier this month.

While the movie is still a ways away, Volkswagen remains trapped in a slow-moving avalanche that the United States triggered last month. On Sept. 18, the Obama administration ordered the German automaker to pull 500,000 of its diesel cars off the road, saying that it had programmed its vehicles with illegal software to intentionally dodge U.S. emission standards. During testing, the cars checked out fine. On the road, however, they emitted up to 40 times the legal amount for harmful pollutants.

On Sept. 22, Volkswagen revealed that 11 million of its cars were rigged worldwide. A day later, the company’s CEO, Martin Winterkorn, resigned. Last week, Michael Horn, Volkswagen’s top U.S. executive, apologized to lawmakers for the scandal during a congressional hearing. Volkswagen is facing a German investigation, as well as up to $18 billion in fines from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Bloomberg’s Anousha Sakoui points out that the movie deal is the latest in Hollywood’s capitalization on high-profile scandals:

Hollywood studios have been keen to seize on business scandals and have been competing aggressively for book rights. Lions Gate Entertainment Corp. next year will release “Deepwater Horizon,” a story about the BP Plc offshore oil platform that exploded in 2010. The film stars Mark Wahlberg. Paramount plans to release “The Big Short,” a film based Michael Lewis’s book about the collapse of the housing market.

Volkswagen officials have repeatedly vowed to work to restore the public’s trust in the company. An investigative book and a major motion picture about its worst moment may make that venture more difficult.

No Charges for Cecil the Lion's Killer

The American dentist who killed a lion in Zimbabwe this summer will not face charges, the country’s officials said.

A cabinet minister said Monday that Zimbabwe will not attempt to extradite James Walter Palmer, who shot to death Cecil, a lion beloved by locals and researchers, in July, the Associated Press reports. After the killing, Zimbabwe officials had vowed to bring Palmer, who lives in Minnesota, back to the country to face poaching charges. AP explains why law enforcement has stepped back:

[Environment minister Oppah Muchinguri-Kashiri] told reporters in Harare that Palmer can now safely return to Zimbabwe as a "tourist" because he had not broken the southern African country's hunting laws. She said the police and the National Prosecuting Authority had cleared Palmer of wrongdoing.

The death of Cecil, who lived in Hwange National Park, sparked outrage across the globe from a variety of people, including animal conservationists and politicians. Palmer received a slew of hate messages, and protesters surrounded his dental office in Bloomington, Minnesota, which closed temporarily. More than 230,000 people signed a White House petition that urged the U.S. State and Justice departments to work with Zimbabwe on the potential extradition request. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said it would “assist Zimbabwe officials in whatever manner requested.”

How Obama Views Strength

Anyone who got beat up as a kid knows there’s no one weaker than a bully. International politics is slightly more complicated than that, of course, but not by much.

During a lengthy interview with Steve Kroft on 60 Minutes that aired Sunday night, President Obama tried to explain how Russian President Vladimir Putin’s shows of strength in Syria and Ukraine actually reflected weakness. In doing so, Obama also warned against the United States making the same mistake.

Kroft opened by noting how much the world had changed since their last interview, and what that meant for America’s influence overseas.

A year ago when we did this interview, there was some saber-rattling between the United States and Russia on the Ukrainian border. Now it’s also going on in Syria. You said a year ago that the United States—America leads. We’re the indispensible nation. Mr. Putin seems to be challenging that leadership.

Obama asked for clarification, and Kroft provided it. “Well, he’s moved troops into Syria, for one. He’s got people on the ground,” Kroft said. “Two, the Russians are conducting military operations in the Middle East for the first time since World War II bombing the people that we are supporting.” To which Obama replied:

So that’s leading, Steve? Let me ask you this question. When I came into office, Ukraine was governed by a corrupt ruler who was a stooge of Mr. Putin. Syria was Russia’s only ally in the region. And today, rather than being able to count on their support and maintain the base they had in Syria, which they’ve had for a long time, Mr. Putin now is devoting his own troops, his own military, just to barely hold together by a thread his sole ally.

In terms of perceptions of world events, there may be less daylight between Obama and Putin than Obama and his critics. Both world leaders see Moscow’s effective loss of two formerly close allies over the past two years: Ukraine to revolution, and Syria to civil war. Obama perceives Putin’s recent actions—the carving out of rump territories in Crimea and the Donbass and the bombing of U.S.-aligned rebels in Syria—as a desperate attempt to reverse a tide that’s shifting against Russian interests.

Many of Obama’s critics have an opposite interpretation: that the Russian intervention in Syria is an act of strength, and the White House’s relative inaction represents weakness. Kroft summed up this interpretation of events fairly well in a subsequent exchange:

There is a perception in the Middle East among our adversaries, certainly and even among some of our allies that the United States is in retreat, that we pulled our troops out of Iraq and ISIS has moved in and taken over much of that territory. The situation in Afghanistan is very precarious and the Taliban is on the march again. And ISIS controls a large part of Syria.

After interrupting one another, during which Kroft said that Obama’s critics argue the president is “projecting a weakness, not a strength,” Obama turned the examples against these unnamed critics, singling out his opponents within the Republican Party. The logic for U.S. intervention in Syria, he argued, previously led to the Iraq War, and its continued usage suggests that many haven’t learned the lessons of that conflict.

[There are Republicans] who think that we should send endless numbers of troops into the Middle East, that the only measure of strength is us sending back several hundred thousand troops, that we are going to impose a peace, police the region, and—that the fact that we might have more deaths of U.S. troops, thousands of troops killed, thousands of troops injured, spend another trillion dollars, they would have no problem with that. There are people who would like to see us do that. And unless we do that, they’ll suggest we’re in retreat.

Here Obama tries to differentiate between the reality of international relations and the perception of world events. The U.S., as Obama notes, is objectively the most powerful player in the Middle East by whatever metric one wishes to apply: diplomatic alliances, economic clout, military strength, cultural influence, and so forth. But between the spread of ISIS and a unilateral Russian intervention to save the Assad regime, it doesn’t quite feel like the U.S. is the strongest actor there anymore. For some critics, these events are an attack on U.S. “leadership,” to borrow their phraseology, and the Obama administration’s failure to respond with military force signals a lack of “strength” at best and outright “weakness” at worst.

Two issues arise. First, this thinking mirrors how Putin processes his own response to attacks on his country’s interests: A global rival’s actions threaten his perceived sphere of influence, and those actions must be countered with force. In Ukraine, it was the Euromaidan protests that threatened to permanently dislodge Kiev from Moscow’s orbit; in Syria, it may have been the transfer of U.S. arms to anti-Assad rebels. In response, Putin annexed Crimea last year, with disastrous implications for the Russian economy, and is now trying to save the Assad regime this year.

Second, there is also little evidence that a U.S. military intervention in Syria would succeed where interventions in Iraq and Libya failed. In both instances, intervention actually increased regional instability instead of quelling it. Since popular resistance to large-scale military interventions helped propel Obama to the presidency in 2008, it’s unsurprising he’s still skeptical of their efficacy.

[If], in fact, the only measure is for us to send another 100,000 or 200,000 troops into Syria or back into Iraq, or perhaps into Libya, or perhaps into Yemen, and our goal somehow is that we are now going to be, not just the police, but the governors of this region, that would be a bad strategy, Steve. And I think that if we make that mistake again, then shame on us.

When asked if the world was a safer place, Obama replied that America is a safer place.

“I think that there are places, obviously, like Syria, that are not safer than when I came into office,” he noted, before pivoting to his multilateralist approach. “But, in terms of us protecting ourselves against terrorism, in terms of us making sure that we are strengthening our alliances, in terms of our reputation around the world, absolutely we're stronger.”

Love in the Age of Reality Television

My reality TV doppelgänger wears a slouchy hat and a pea coat. In a soft-focus flashback, she wanders alone through a generic cityscape, accompanied by somber piano music. She lounges outside a coffee shop, paging through highlighted books with her glittery fingernails, and crossing a bridge unsettlingly similar to one near where I live in Pittsburgh. She also nails one of my favorite docudramatic standards: contemplatively staring off into the sunset.

I never expected be on a reality dating show. Not only did I never plan to appear in person, but I also never expected to watch myself portrayed on one by an actress. Then, last winter, my college ex-boyfriend, David, appeared as a contestant on a popular Chinese dating show called Fei Cheng Wu Rao, or If You Are the One. He’s been living in Beijing for the past six years, having moved there the summer after our college graduation and our break-up. We keep in occasional contact, so I knew David had already been on TV a couple times before. American expats appearing on Chinese TV is not uncommon: As explained in a June 2012 episode of This American Life, seeing foreigners perform and do “silly” things on TV—speak Mandarin, wear traditional garb, dance—is novel and hugely popular. I’d seen David before on a talk show whose bare-bones set resembled something you’d see on an American public-access channel.

But unlike David’s past TV appearances, If You Are the One isn’t an obscure program: It’s the most-watched dating show in the Chinese-speaking world. When it premiered in 2010, it broke ratings records, boasting more than 50 million viewers. Its recent sixth season drew 36 million—about as many people as watched the last Oscars in the U.S. By comparison, its American prime-time counterpart, The Bachelor, brought in only 8.1 million viewers for its most recent season finale in July.

Knowing that the number of people who saw my appearance on If You Are the One equaled the population of some countries was only part of the embarrassment I experienced. The first time I saw the video clip of myself, I called a Mandarin-speaking friend at 11 p.m. to translate immediately. Reduced to pure vanity, I shouted into the phone, “Do I wear weird hats? Why do the books have to be used?” I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry as I watched the line between my inner and outer lives dissolve before my eyes, repossessed by a TV show I didn’t even know. As a student of cultural studies, I was intellectually fascinated: The philosopher Jean Baudrillard portentously wrote in 1986 that “everything is destined to reappear as a simulation”—even the events of your own life. But emotionally, I didn’t know how to confront my own repackaged image, or how to distinguish where I ended and a larger media agenda began.

* * *

My confusion was further amplified by the fact that this was a love story. For more than a decade now, reality dating shows like The Bachelor have run with the idea that few things are more performative than love and courtship. Even before watching myself on If You Are the One, I was no stranger to TV-produced romance and the tropes of looking for your One True Love (an avid Bachelor viewer, at that time I was plowing through the show’s 19th season). The Bachelor franchise, which refers to its fans as “Bachelor Nation,” encompasses some of the longest-running U.S. dating shows and has consistently produced some of the most-watched television across female viewers of all ages.

Compared to The Bachelor, If You Are the One’s format is more carnivalesque, modeled after an Australian show called Taken Out. The show isn’t serialized, but instead features multiple bachelors per 90-minute episode. Male contestants take the stage encircled by a panel of 24 female candidates—standing at individual podiums in a configuration known as “the avenue of love”—who use lights to indicate their interest. As the women listen to a suitor banter with the show’s host, reveal information about his life in video clips, and watch him perform in what amounts to a “talent” portion, they can elect to turn off their podium lights and clock out of the competition (similar to The Voice). The last women with their lights left on become finalists, and one of them—hopefully—becomes a match.

As the first contestant on the show’s season-six premiere, David sang and danced, solved a Rubik’s cube on stage, and responded to wisecracks about his resemblance to Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory. He also participated in the show’s “love resume” segment, where our relationship rehash came in. I was one of two ex-girlfriends portrayed by the same actress—who also portrayed David’s future ideal partner—all of us wearing different hats and subject to the same nauseatingly saccharine piano music. (I tried to imagine the conversation between David and the show’s producers about how to construct the story of our two-year relationship for a 30-second spot.) As the reality TV version of me gazes toward the sky in the style of a MySpace picture, David explains in voiceover that I was a student when we met, a bookworm, and an aspiring professor. But I was also the prototypical American woman: strong, independent, and not reliant on a man—the implied reason for our break-up. To my great vindication, seven women clock out after hearing this.

Seeing my self-image hyper-realized and mirrored back to me was much more humiliating than airing my break-up story.As a break-up made for Chinese TV, the story made sense. The cultural messaging in If You Are the One has been a source of controversy since its inception in 2010. The show’s creator, the veteran TV producer Wang Peijie, told The New York Times in 2011 that his original intention was to shed light on young professionals in contemporary China, where values are changing. Contestants were portrayed as urbane and glamorous and often more concerned with money and mobility than marriage and tradition. The show made international headlines in its first six months when a 20-year-old female contestant, Ma Nuo, famously declared that, when it came to dating, she would rather “cry in a BMW” than smile on a bicycle. Following the media firestorm, which for some in China pointed to the encroachment of Western materialism and “the degradation of Chinese social values,” the state-controlled TV network began censoring the show. Since then, Wang told the Times, If You Are the One has sought more marriage-minded participants—similar to the relentlessly traditional heteronormativity on The Bachelor.

* * *

It would be easy for me to assume that the story of my relationship was completely subsumed by the larger cultural narratives at play—that it was serving a television show’s ideological ends that have nothing to do with me personally. It would also be easy for me to dismiss the whole absurd incident out of hand, as some friends advised me to do, and to simply declare that this portrayal of me wasn’t me. “She’s an actress in a relationship dramatized for reality TV,” a friend reassured me. And the easiest dodge would be to say that, even before it’s filtered through TV producers, the story of any relationship is an unreliable narrative, ultimately boiling down to two conflicting accounts. The experience is an essential part of being an ex, albeit on a mass-media scale: Your former partner constructs his or her own story about you to tell other people and potential partners—without you. It’s not worth worrying and trying to “set the record straight,” if I even believed such a thing were possible.

But as my embarrassment diminished at being broadcast to millions wearing a less-than-flattering hat, I still couldn’t shake the feeling of uncanniness. Is she me or is she not me? I kept asking. What really bothered me was that, despite my attempts to rationalize it otherwise, this wasn’t an unrecognizable version of myself. I am, after all, an American woman with American values. I do value my independence, where I tool around my city and write in coffee shops. I indulge and imagine myself as literary and cultured and try to project these things to others. Seeing my self-image hyper-realized and mirrored back to me—even my insecurities about being cold, too much in my own head—was much more humiliating than airing my break-up story. It was a pointer toward the performance in everything I do, and certainly the roles I’d played in that relationship.

I was recently confronted with this interplay of real versus acted watching Lifetime’s new drama UnREAL. The series, which debuted in June, is about making a reality dating show called Everlasting—a fictional stand-in for The Bachelor. Written by Marti Noxon and Sarah Gertrude Shapiro, UnREAL is based on Shapiro’s own real-life experiences working for the franchise. I was initially intrigued by how UnREAL offered an opportunity to peer behind the curtain and reveal what Bachelor viewers already suspect: The bachelor isn’t earnestly seeking true love, but is instead a princely playboy trying to rehab his public image. Most of the female contestants aren’t doting future wives, but aspiring starlets. Anyone invested in a love story is assumed to be naive, as it’s taken as a given that the show’s participants know what they signed on for: to be coached and manipulated to manufacture romance and maximize competitive drama.

But my true fascination with UnREAL was the portrayal of Everlasting’s producers. UnREAL captures beautifully how lost, disintegrated, and amoral they become while trying to sell love on TV. Though having editorial control should theoretically afford them some insight, they are as conniving as the show’s contestants and even more confused about the possibility of finding love in their own lives. In the season finale, against the backdrop of Everlasting’s own season finale, UnREAL’s two female protagonists and Everlasting producers (Constance Zimmer and Shiri Appleby) both suffer the fall-out from unstable on-set affairs. Zimmer’s character, Quinn, shaking her head at herself admits, “I think that I actually started to believe the crap that we sell here.”

It’s the larger venture of the show itself that swallows everyone; the effort invested in fabricating love leaves little room for genuine human emotion. In the case of the reality dating show, art not only imitates life, but infects it. Seeing myself as a character, reduced to clothing and gestures and tropes, made me wonder if performance was all there was in my relationship—if there was actually anything “real” to recover from it. I still can’t draw definitive lines, or figure out where I begin and where my doppelganger ends. But ultimately I know I have memories that can’t be recreated, and that are far richer and more complicated than any scene or image could be.

Man Booker Shortlist 2015: The Year of the Runaways

Somewhere in Northern England, a man known only as Mr. Smith is indulging in an unusual hobby: betting on the winner of the Man Booker Prize. He got it right last year, correctly predicting that Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North would take the prize. This year, he’s putting his money on Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways, which traces a year in the lives of four young migrants from India struggling to make a living in England. But he hasn’t even read either novel (or any of the other five on this year’s shortlist). He goes by reviews and the literary tastes he gleans from the judges’ Wikipedia entries.

That Mr. Smith hasn’t read Sahota’s book seems appropriate. Sahota, a British citizen, says he didn’t read a novel himself until he was 18—his pre-college English literature curriculum focused on drama and poetry (he went on to study math). The Year of the Runaways, published this summer in Britain and scheduled to be released in the U.S. on March 1, 2016, is his second novel. It follows the more explicitly political Ours Are the Streets (2011), the diary of a young British Pakistani suicide bomber.

Runaways, too, is a dark book, joining a roster that Michael Wood, the chair of the Man Booker Prize’s committee, acknowledged to the BBC is “pretty grim," adding that “there is a tremendous amount of violence.” But what is striking about Sahota’s newer novel—in contrast to its predecessor and some of its Man Booker company—is its focus on mundane, unremitting struggle, not violent drama (although there’s some of that too). Sahota’s real challenge lies in finding a way to depict lives of daily degradation, poverty, and prejudice while avoiding tedium, and ultimately suggesting that a better future is possible.

Picador

Picador Set in 2003, the book is structured around the year announced in its title. Four novella-length chapters span one season each. Yet within them, Sahota cross-cuts in bold and disorienting ways, alternating between the backstories of the four main characters and scenes from their present lives. Three are men—Tarlochan, Avtar, and Randeep—who make their way to the northern town of Sheffield, just a few among many young Indians bending the law to find opportunity in England. The fourth is Narinder, a pious British-born Sikh woman who is to be Randeep’s visa wife.

Sahota covers all the big issues that might face Indian immigrants—racially motivated violence; the remnants of a lingering caste system; questions of faith and skepticism; the difficult limitations of conventional ideas about gender and sex—by dealing, relentlessly, with the small details. It’s all a matter of paying the rent and making dinner; placating parents and bosses and immigration officials; finding and keeping love. Someone is always trying to catch up on sleep, and no one ever has enough money. They seem unprepared—like Randeep, who considers himself “too young to be anything.”

“What decadence this belonging rubbish was,” laments Avtar. “What time the rich must have if they could sit around and weave great worries out of such threadbare things.” Reality enforces a grit-your-teeth attitude—and even in their immigrant “community,” no sense of belonging offers much respite. There are skirmishes and brawls; workers sabotage each other; roommates in crowded houses steal each other’s savings. Alliances are fragile. Conflict rages within families, too, where filial loyalties are tested on new soil. Characters carry the weight of past traumas, but have no choice but to begin again in an equally difficult world. “Go back now,” an older laborer tells Tochi. “Before there’s nothing to go back for.”

There are no revolutionaries among Sahota’s foursome. Tarlochan, a survivor of horrific ethnic violence, doesn’t organize his oppressed chamar caste. Avtar doesn’t ace his computer-science classes and transform modern technology. Narinder, the pious visa wife, doesn’t become a radical feminist. Rather than seize upon political issues for the feel-good arc of a protest novel, Sahota subtly, powerfully, shows the devastating effect on his characters of narrow horizons.

Narinder, the primary female protagonist and the only British native, is less constrained by economic problems, and her past is the least traumatic—which hardly makes her path less difficult. The others steadily lose faith in the world, but Narinder loses her trust in God. She abandons Sikhism, letting her hair out of her turban as it “[comes] down in ribbons, loosening, uncoiling, falling.” Yet her liberation is temporary and tenuous; she ultimately yields to her father’s demands and returns to her parents’ home to tend to him.

The runaways themselves have been reshaped by the world they have run away to.Still, by the epilogue, more than a decade later, things have shifted. There have been marriages, births, and deaths. The protagonists have gained an economic foothold, followed conventional paths, and settled into family life, or resisted this assimilation. Even if their lives now seem ordinary, the runaways themselves have been reshaped by the world they have run away to. “You haven’t changed,” Narinder tells Avtar, now a husband and father. “Oh, I think we both know that’s not true,” he replies.

Mr. Smith, the mysterious better, doesn’t mention current events as one of the considerations that shape his Man Booker predictions. But a mere glance at the daily newspaper reveals why this chronicle of migration deserves attention today. Only portraits like Sahota’s can describe the experience of being a migrant. Largely based on Mr. Smith’s pick, the British betting house Ladbrokes puts Runaways’s current odds of winning at 9/4, behind only A Little Life at 6/4, as last week ended. On Tuesday, the suspense will be over.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower