Ned Hayes's Blog, page 9

May 14, 2018

On Writing: About Moral Gravity and Pleasure and "Comfortable" Writing (and Stephen King)

Last week, I picked up a book that’s been on my shelf for a long time. This was Different Seasons by Stephen King. This book is a collection of four novellas, and was his first publication that reached outside of the horror genre. The book includes the novellas Apt Pupil, The Body, The Shawshank Redemption and The Breathing Method (I had only read Shawshank Redemption before I picked up this book). I began reading the book purely for pleasure, and then I began asking myself about why precisely this book was pleasurable to me as a reader. This paper is about a few of the specific pleasures that I found King brings to a reader. I’m enumerating them here because I hope to duplicate these particular attributes in my own writing.

Last week, I picked up a book that’s been on my shelf for a long time. This was Different Seasons by Stephen King. This book is a collection of four novellas, and was his first publication that reached outside of the horror genre. The book includes the novellas Apt Pupil, The Body, The Shawshank Redemption and The Breathing Method (I had only read Shawshank Redemption before I picked up this book). I began reading the book purely for pleasure, and then I began asking myself about why precisely this book was pleasurable to me as a reader. This paper is about a few of the specific pleasures that I found King brings to a reader. I’m enumerating them here because I hope to duplicate these particular attributes in my own writing.

The thing about Stephen King is that he is predictable. This is not a bad thing. Setting expectations for readers is something that every writer does. We announce to readers with our titles, our writerly personas, the marketing blurbs and in our writing style (Noir? Lyrical? Journalistic? Hemingwayesque? Faulknerian?) what the reader should expect. No reader – I hope – enters into a Cormac McCarthy novel hoping to find a sweet cozy mystery or romance. No one reads romance for blood and gore. But I fear I’m alluding to genre here, when I mean to speak about an attribute of writing that I find particular to King and other writers who have gathered large and consistent audiences.

Yet what Stephen King does is so utterly consistent from book to book that his readers trust him. I knew when I picked up a Stephen King book that I would get human characters that will have a life that I recognize, and that I know as familiar in standard human terms. If behavior must be explained or illuminated for me (as a reader), Stephen King will take the time to explain the behavior until I come to understand that behavior on its own terms and recognize it. This is in stark contrast to a writer like, for example, Jonathan Franzen or Cormac McCarthy, who do not explain their characters in terms of motivation, inner life or external behavior. Their characters thus exist as ciphers to many readers. Some readers find that pleasurable: many others do not.

However, for this reason, some readers (and notably some high-brow writers) believe that Stephen King writes “clichéd” books that contain “stereotypical” characters. This is a valid critique, but I think that all too often writers rely on originality as the prime objective, without realizing that they must ground their stories – and their readers – in the recognizable and the familiar before they take a flight of fancy into the unknown. Part of the reason so-called “dirty realism” fiction (such as that originally popularized by Raymond Carver in the MFA world) became the norm is that it starts with the recognizable, and then the originality is found in building a new perspective or a new framework around the already-known world of the truck driver, the wheat farmer, the mill worker or the down-and-out-drunk. Carver limned his characters in quick stark strokes, with a minimum number of words and descriptors. Yet there’s hardly an “original” character among them: Carver writes no Dickensian Oliver Twists or memorable Martin Chuzzlewits, and will never be known for a character like Scrooge.

However, for this reason, some readers (and notably some high-brow writers) believe that Stephen King writes “clichéd” books that contain “stereotypical” characters. This is a valid critique, but I think that all too often writers rely on originality as the prime objective, without realizing that they must ground their stories – and their readers – in the recognizable and the familiar before they take a flight of fancy into the unknown. Part of the reason so-called “dirty realism” fiction (such as that originally popularized by Raymond Carver in the MFA world) became the norm is that it starts with the recognizable, and then the originality is found in building a new perspective or a new framework around the already-known world of the truck driver, the wheat farmer, the mill worker or the down-and-out-drunk. Carver limned his characters in quick stark strokes, with a minimum number of words and descriptors. Yet there’s hardly an “original” character among them: Carver writes no Dickensian Oliver Twists or memorable Martin Chuzzlewits, and will never be known for a character like Scrooge.

In the way he writes characters, King is like a low-brow John Irving, painting characters vividly so that they stay in your memory. Yet unlike Irving, King does not create caricatures or characters who are memorable for specific traits, behaviors, attitudes or presence in the world. There are no transgender football players, pet bears, or horrific sex accidents in King (cf. Irving’s World According to Garp). King may describe a character with many more words than Carver, yet in the end they are both writing about an “average” mill worker, or police man or homemaker. Both Carver and King start with the average, the norm, and establish that firmly in order to describe what happens to these average characters.

Consider the novella “Apt Pupil” in Different Seasons. In this novella, a young boy is drawn to an older Nazi, and gradually “learns” from him how to be a serial killer and how to discard human lives like leaves. What is really interesting about this story is that I thought I knew the basic plot going in. Old Nazi would entice young boy in a pedophile-like embrace, and gradually things would go to hell. King didn’t write it that way at all. Instead, in the words of one of the main characters, he wrote:

[T]he story of an old man who was afraid… of a certain young boy was, in a queer way, his friend. A smart boy… At first, the boy was not the old man’s friend… At first, the old man disliked the boy a great deal. Then he grew to… to enjoy his company, although there was still a strong element of dislike there […] Part of the old man’s enjoyment came from a feeling of equality… You see, the boy and the old man had each other in mutual deathgrips. Each knew something the other wanted kept secret. (King 191-192)

King’s brilliance here is to make the old Nazi a vulnerable, afraid human being. When a young boy reaches out to him with a threat, they gradually become equals in terms of terror and secrets. I did not expect this at all, and the story entranced me because of the unique approach King took to a story that could have been quite hackneyed. What I meant earlier by “predictability” should instead be characterized as “fully fleshing” his characters. I know that there will be no easy-to-categorize “evil” human beings. Instead, there will be human beings who are flawed and trying to do their best with what they have to work with. He fleshes his people, which is harder to do than it looks.

The other thing that I find intensely “comfortable” about King is that events have moral weight in his novels. Let me explain this point by reference first to Bret Easton Ellis – a writer who I believe avoids moral justice like the plague. Ellis might disagree with this point, and in fact, he often portrays his novels as parodies or satires of moral immorality. Yet at heart, I really think satire is a genre without moral justice – or in mockery of moral justice. Ellis’s characters get away with hell on earth – both in their behavior to other people as well as their behavior to themselves. They don’t live lives that are considered or meaningful, because their actions have no consequence and no moral weight.

The other thing that I find intensely “comfortable” about King is that events have moral weight in his novels. Let me explain this point by reference first to Bret Easton Ellis – a writer who I believe avoids moral justice like the plague. Ellis might disagree with this point, and in fact, he often portrays his novels as parodies or satires of moral immorality. Yet at heart, I really think satire is a genre without moral justice – or in mockery of moral justice. Ellis’s characters get away with hell on earth – both in their behavior to other people as well as their behavior to themselves. They don’t live lives that are considered or meaningful, because their actions have no consequence and no moral weight.

King, on the other hand, even if everything is going to hell – and especially when very bad things are happening – manages to carry his readers through by making an implicit promise that the bad will be accounted for, and that the good (on some level) will triumph. Bad actions have consequence in King, even if they are (as in “The Body”) momentarily avoided. In the end, those who commit crimes are always discovered by themselves or others, and must pay for their actions. And those who quietly do well are discovered in a different way, and rewarded. King is the contemporary writer who most honestly embodies Tolkien’s famous aphorism that it is “the small everyday deeds of ordinary folk that keep the darkness at bay… small acts of kindness, and love” that ultimately defeat evil (Jackson / Tolkien). King adheres to this maxim, almost to a fault. There are no magical mages in King, and very few people with special powers (none that I can think of who understand or control their powers purely for good). There are no melodramatic good guys, and very few purely evil characters. Instead, there is an Everyman or Everywoman who has to struggle with the laundry, self-esteem issues, and their upset spouse, all while struggling with unimaginable forces from the beyond. They are small everyday deeds that ultimately keep the dark at bay. And it is telling that even in these everyday lives, King manages to keep the moral compass clear. In contrast to many other contemporary writers – both literary writers like Paul Auster and commercial writers like Scott Turow – King ensures that we can trust him to bring a moral gravity to his work that is hard to do well, and trite if you don’t pull it off well.

I read King still when I just need some moments of pleasure, because I can trust him to be predictable in terms of his human characters and I trust the moral weight of his books. I’d like to be a writer who is as successful in these two attributes as King has been: even if I never have a Stephen King like commercial success. I think that these two attributes will stand the test of time.

A literary update from NedNote.com

Readers can find my books at these bookstores:

Works Cited

King, Stephen. Different Seasons. New York: Signet, 1983.

The Hobbit: The Unexpected Journey. Dir. Peter Jackson. Warner Bros, 2012. Film.

On Writing: About Moral Gravity and Pleasure and “Comfortable” Writing (and Stephen King) was originally published on Ned Hayes

May 8, 2018

Bookstores: Ada's Technical Books in Seattle

Find my books at Ada’s Technical Books

In the early 2000s, a blusterous tech guy I knew in Seattle went to work for Amazon. Shortly afterwards, I had coffee with my old friend, and he proceeded to tell me how the future of books was Amazon and ebooks. Therefore, in his thinking, all bookstores would soon die, following print books down into the death spiral of ancient history. For some time, it did seem like a number of tech people in Seattle were convinced of this (as-yet-unrealized) nightmare possibility.

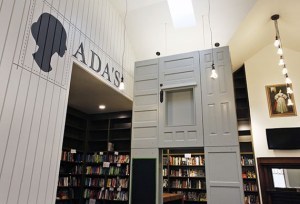

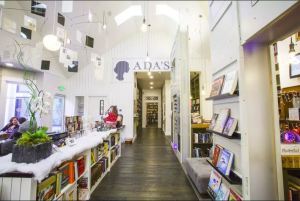

I’m so thankful that Danielle and David Hulton didn’t listen to his bluster. Ten years after my conversation with *that guy*, Danielle and David acquired the slightly woebegone remains of Horizon Books, refurbished the heck out of a classic Capital Hill building and opened a new bookstore in the hip Capital Hill neighborhood in Seattle — Ada’s Technical Books.

Named after Ada Lovelace — (Augusta Ada King-Noel, Countess of Lovelace (10 December 1815 – 27 November 1852). Ada was an early mathematician and writer, known for her work on Charles Babbage‘s proposed mechanical general-purpose computer, the first Analytical Engine.

Ada was the first to recognise that the machine had applications beyond pure calculation, and ne” and is generally regarded as the first computer programmer. She also happens to be the only legitimate daughter of Lord Byron, one of my literary heroes. As Danielle Hulton says “She was a super interesting person!”

Like me, Danielle is a computer programmer who also loves books. Ada’s Technical Books started when Danielle decided to leave her engineering job at Seattle-based Pico Computing (FPGA platform startup). Although they lived in Seattle, they didn’t look to Amazon for guidance and just go online. I’m very glad that instead they saw Powell’s Technical Books in Portland as a great inspiration. Book geeks all over Seattle make regular pilgrimages to Powell’s, so it made sense to duplicate part of Powell’s Technical Books charm in Seattle.

On the fiction front, I was extremely gratified to find that the interests of the Ada’s Technical Books team overlap nicely with mine. Danielle told Geek Girl Con that she loves “Octavia Butler’s ‘Lilith’s Brood’ and Neal Stephenson’s ‘Snow Crash.’ I also really love ‘Pattern Recognition’ by William Gibson and anything by Cory Doctorow.”

Danielle Hulton, owner of Ada’s Technical Books

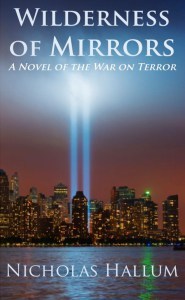

This sounds like a bookseller after my own heart. In fact, given her interests, I’m hoping that when my new speculative fiction novel Wilderness of Mirrors is published, it will find a great home on the SFF shelf at Ada’s Technical Books.

Ada’s Technical Books has a unique focus — it’s in their name — they focus on books for the tech-geek set. Besides technical books, programming books, fiction and mechanically-minded manuscripts, they also provide maker gear such as chemistry sets, tools and make-your-own drone kits.

Ada’s also includes a wonderful cafe with a great menu, a gathering space for the tech community, an event and breakout room, and a co-working space that can accommodate up to 20 individuals at a time. For the owners, it’s all about creating a community around books — which many people have noted is the key to an indie bookstore’s long-term survival and success.

David Hulton said this to GeekWire about building a community at Ada’s: “(It’s a) place where people can learn, and keep up to date on things that are coming out, and also foster their creativity and be able to meet other people that are also interested in learning the geeky things that they’re interested in as well.”

Ada’s Technical Books is also willing to push the technical envelope in terms of new technology and new ways of using technology. For example, in contrast to many indie bookstores, Ada’s has sold e-book readers since the beginning and continues to sell readers and ebooks today. It’s also worth noting that Ada’s Technical Books will convert your Bitcoin into cash and will accept Bitcoin as payment.

I first visited Ada’s Technical Books in 2012, two years after they first opened, and I loved finding this boutique jewel of a bookstore.

Every time I’m in Seattle, I try to make a point to stop in at Ada’s Technical Books, and check on the new fiction and non-fiction that graces their shelves. In fact, I’ve taken fourteen out-of-town visitors to have the Ada’s experience on Capital Hill. I’ll note that after my family and I visit Ada’s, the experience is often followed by a hearty seafood-flavored breakfast at one of our favorite Seattle joints, Coastal Kitchen, where we enjoy our books with a great hangtown fry and steaming cups of strong Seattle coffee.

Ada’s is one of my literary touchstones, and I hope you enjoy the read!

Find my books at Ada’s Technical Books

[Read more BOOKSTORE POSTS]

Pinterest – Ned Hayes Bookstore Board

Bookstores: Ada’s Technical Books in Seattle was originally published on Ned Hayes

May 7, 2018

Poem: Station

Maria Hummel’s book House And Fire was the winner of the APR/Honickman First Book Prize, 2013.

“Station” is a pantoum, a Malay verse form, imitated in French and English, consisting of quotations.

Days you are sick, we get dressed slow,

find our hats, and ride the train.

We pass a junkyard and the bay,

then a dark tunnel, then a dark tunnel.

You lose your hat. I find it. The train

sighs open at Burlingame,

past dark tons of scrap and water.

I carry you down the black steps.

Burlingame is the size of joy:

a race past bakeries, gold rings

in open black cases. I don’t care

who sees my crooked smile

or what erases it, past the bakery,

when you tire. We ride the blades again

beside the crooked bay. You smile.

I hold you like a hole holds light.

We wear our hats and ride the knives.

They cannot fix you. They try and try.

Tunnel! Into the dark open we go.

Days you are sick, we get dressed slow.

Source: Poetry (September 2010)

Poem: Station was originally published on Ned Hayes

May 3, 2018

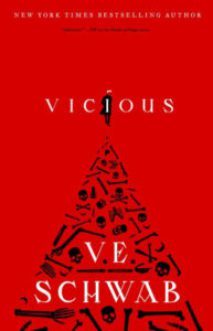

In Search of Doors: V.E. Schwab

A simply marvelous Tolkien Lecture by the wonderful writer Victoria Schwab.

Schwab speaks of J.K. Rowling, Neil Gaiman, Susanne Clarke and so many more writers who have my world astonishing, more hopeful and yes, stranger as well. I truly enjoyed every moment of this thoughtful, insightful, challenging and evocative talk by a writer I admire and enjoy. I hope you enjoy too!

And here is a list of the books by her that I have enjoyed the most:

THE VILLAINS SERIES

Superpowers don’t make you a superhero.

Victor and Eli started out as college roommates―brilliant, arrogant, lonely boys who recognized the same sharpness and ambition in each other. But when they discover a connection between near-death experiences and supernatural abilities, things go horribly wrong. Ten years later, Victor breaks out of prison, determined to catch up to his old friend (now foe), aided by a young girl whose reserved nature obscures a stunning ability. Meanwhile, Eli is on a mission to eradicate every other super-powered person that he can find―aside from his sidekick, an enigmatic woman with an unbreakable will. Armed with terrible power on both sides, and driven by the memory of betrayal and loss, the archnemeses have set a course for revenge―but who will be left alive at the end?

Victor and Eli started out as college roommates―brilliant, arrogant, lonely boys who recognized the same sharpness and ambition in each other. But when they discover a connection between near-death experiences and supernatural abilities, things go horribly wrong. Ten years later, Victor breaks out of prison, determined to catch up to his old friend (now foe), aided by a young girl whose reserved nature obscures a stunning ability. Meanwhile, Eli is on a mission to eradicate every other super-powered person that he can find―aside from his sidekick, an enigmatic woman with an unbreakable will. Armed with terrible power on both sides, and driven by the memory of betrayal and loss, the archnemeses have set a course for revenge―but who will be left alive at the end?

Coming this September, the super-powered sequel…a woman who can turn her enemies to ash. A girl without a face. And of course, Victor Vale is back…

THE CASSIDY BLAKE SERIES

Ever since Cass almost drowned (okay, she did drown, but she doesn’t like to think about it), she can pull back the Veil that separates the living from the dead … and enter the world of spirits. Her best friend is even a ghost.

So things are already pretty strange. But they’re about to get much stranger.

When Cass’s parents start hosting a TV show about the world’s most haunted places, the family heads off to Edinburgh, Scotland. Here, graveyards, castles, and secret passageways teem with restless phantoms. And when Cass meets a girl who shares her “gift,” she realizes how much she still has to learn about the Veil — and herself.

And she’ll have to learn fast. The city of ghosts is more dangerous than she ever imagined.

THE MONSTERS OF VERITY SERIES

In a world where violence breeds monsters, there’s no such thing as safe.

Kate Harker and August Flynn are the heirs to a divided city—a city where the violence has begun to breed actual monsters. All Kate wants is to be as ruthless as her father, who lets the monsters roam free and makes the humans pay for his protection. All August wants is to be human, as good-hearted as his own father, to play a bigger role in protecting the innocent—but he’s one of the monsters. One who can steal a soul with a simple strain of music. When the chance arises to keep an eye on Kate, who’s just been kicked out of her sixth boarding school and returned home, August jumps at it. But Kate discovers August’s secret, and after a failed assassination attempt the pair must flee for their lives.

Nearly six months after Kate and August were first thrown together, the war between the monsters and the humans is a terrifying reality. In Verity, August has become the leader he never wished to be, and in Prosperity, Kate has become the ruthless hunter she knew she could be.

When a new monster emerges from the shadows—one who feeds on chaos and brings out its victim’s inner demons—it lures Kate home, where she finds more than she bargained for. She’ll face a monster she thought she killed, a boy she thought she knew, and a demon all her own.

THE SHADES OF MAGIC SERIES

Magic, mayhem, and multiple Londons.

Kell is one of the last Antari―magicians with a rare, coveted ability to travel between parallel Londons; Red, Grey, White, and, once upon a time, Black. Officially he serves the Maresh Empire as an ambassador. Unofficially he’s a smuggler, servicing people willing to pay for even the smallest glimpses of a world they’ll never see. After an exchange goes awry, Kell escapes to Grey London and runs into Delilah Bard, a cut-purse with lofty aspirations. She first robs him, then saves him from a deadly enemy, and finally forces Kell to spirit her to another world for a proper adventure. Now perilous magic is afoot, and treachery lurks at every turn. To save all of the worlds, they’ll first need to stay alive.

Four months have passed since the events of Darker Shade. As Red London finalizes preparations for the Element Games-an extravagant international competition of magic, meant to entertain and keep healthy the ties between neighboring countries-a certain pirate ship draws closer, carrying old friends back into port. But while Red London is caught up in the pageantry and thrills of the Games, another London is coming back to life, and those who were thought to be forever gone have returned—meaning that another London must fall.

The precarious equilibrium among four Londons has reached its breaking point. Once brimming with the red vivacity of magic, darkness casts a shadow over the Maresh Empire. Who will crumble? Who will rise? And who will take control?

THE ARCHIVED SERIES

Imagine a world where the dead are shelved like books.

Each body has a story to tell, a life seen in pictures only Librarians can read. The dead are called Histories, and the vast realm in which they rest is the Archive.

Mackenzie is Keeper, tasked with stopping often violent Histories from waking up and getting out. Because of her job, she lies to the people she loves, and she knows fear for what it is: a useful tool for staying alive. Being a Keeper isn’t just dangerous—it’s a constant reminder of those Mac has lost, Da’s death was hard enough, but now that her little brother is gone too, Mac starts to wonder about the boundary between living and dying, sleeping and waking. In the Archive, the dead must never be disturbed. And yet, someone is deliberately altering Histories, erasing essential chapters. Unless Mac can piece together what remains, the Archive itself may crumble and fall.

Last summer, Mackenzie Bishop, a Keeper tasked with stopping violent Histories from escaping the Archive, almost lost her life to one. Now, as she starts her junior year at Hyde School, she’s struggling to get her life back. But moving on isn’t easy — not when her dreams are haunted by what happened. She knows the past is past, knows it cannot hurt her, but it feels so real, and when her nightmares begin to creep into her waking hours, she starts to wonder if she’s really safe.

Meanwhile, people are vanishing without a trace, and the only thing they seem to have in common is Mackenzie. She’s sure the Archive knows more than they are letting on, but before she can prove it, she becomes the prime suspect. And unless Mac can track down the real culprit, she’ll lose everything, not only her role as Keeper, but her memories, and even her life. Can Mackenzie untangle the mystery before she herself unravels?

In Search of Doors: V.E. Schwab was originally published on Ned Hayes

May 1, 2018

Kindle Scout Success Story: Ned Hayes

Highlights: Ned Hayes

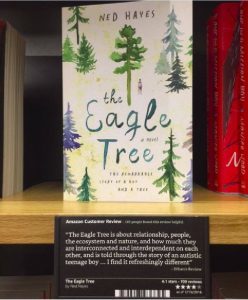

Ned Hayes was a part-time author of historical fiction when he got the idea for The Eagle Tree. The novel was so different from his previous work that he feared nobody but him would like it.

He decided to submit the novel to Kindle Scout – a place where authors can share their never-before-published books, and customers can nominate their favorites to be published.

Support from Kindle Scout readers helped The Eagle Tree land a publishing deal with Amazon Publishing’s literary imprint, Little A, and a bigger audience than Ned has ever reached before.

Ned Hayes wrote a novel so far outside his comfort zone that he wondered if anyone would enjoy it. Kindle Scout readers answered with a resounding “yes.”

New characters often visit novelist Ned Hayes uninvited, so it wasn’t all that strange a few years back when the voice of a fictional teenage boy kept percolating in the back of his mind. Then things got more intense: “A friend of mine took me to this amazing old-growth tree, and the first lines of the story, where the boy saw the Eagle Tree and wanted to climb it, just rose up in me. I had to write the story down. I felt kind of carried away by a rushing stream, and I didn’t know where it was really taking me.”

I felt like I’d given someone a voice who didn’t have one.

— Ned Hayes

The rushing stream carried Ned to The Eagle Tree, a novel unlike anything he’d ever written. He was a published author of historical fiction, and – even though writing novels wasn’t his full-time job, and his books had never reached massive numbers of readers – his work had earned him representation by an established literary agent. But far from being the historical fiction the agent expected, The Eagle Tree was set in modern times, and that percolating voice in Ned’s head turned out to belong to a teenage boy diagnosed with autism. In the novel, young March Wong climbs dangerously high into Washington’s forests to chase his passion for learning all about trees.

The rushing stream carried Ned to The Eagle Tree, a novel unlike anything he’d ever written. He was a published author of historical fiction, and – even though writing novels wasn’t his full-time job, and his books had never reached massive numbers of readers – his work had earned him representation by an established literary agent. But far from being the historical fiction the agent expected, The Eagle Tree was set in modern times, and that percolating voice in Ned’s head turned out to belong to a teenage boy diagnosed with autism. In the novel, young March Wong climbs dangerously high into Washington’s forests to chase his passion for learning all about trees.

“When I first gave the manuscript to my agent, she read it through and said, ‘Well, this is a really different kind of book, and I’m not sure I can sell this.’,” Ned says.

Ned didn’t push. He had his own doubts. “I was concerned that maybe it was a book that I had written just for my own pleasure and that I would be the only reader that really enjoyed it.”

Ned knew a way to test whether the novel would ever speak to anyone but him. As a reader, he’d been participating in Kindle Scout, where authors can submit their never-before-published books. Readers see excerpts from each book, and they can nominate their favorites to receive a publishing contract from Amazon. Ned submitted The Eagle Tree and waited to see if anyone would nominate it. He was about to be carried away by another rushing stream.

“One of the earliest comments I received,” Ned starts to say, surprising himself by choking up, “was from somebody who had a family member who was on the autism spectrum. They said that this book gave them insight into their family member in a way that they never expected, and it changed their entire relationship. And I just felt really moved by that. Because I felt like I’d given someone a voice who didn’t have one.”

The response from Scout users was overwhelming. The Kindle Scout team also saw serious potential in Ned’s work and shared his manuscript with Carmen Johnson, an editor at Amazon Publishing’s Little A imprint. Carmen loved it. She worked with Ned to release Kindle, paperback, and audiobook versions of The Eagle Tree. Thinking back to the exciting weeks when everything came together, Ned says, “Amazon really ended up opening a huge number of doors for me.”

The response from Scout users was overwhelming. The Kindle Scout team also saw serious potential in Ned’s work and shared his manuscript with Carmen Johnson, an editor at Amazon Publishing’s Little A imprint. Carmen loved it. She worked with Ned to release Kindle, paperback, and audiobook versions of The Eagle Tree. Thinking back to the exciting weeks when everything came together, Ned says, “Amazon really ended up opening a huge number of doors for me.”

More than 75,000 readers later, the character of March Wong continues to connect with people. Steve Silberman, whose NeuroTribes appeared on many of the most prestigious lists of the best books of 2015, praised Ned’s “gorgeously written” book for featuring “one of the most accurate, finely drawn and memorable autistic protagonists I’ve come across in literature.”

The success of The Eagle Tree has opened new doors for Ned. He’s collaborating with fellow artists on a graphic novel and an independent film based on the book. He’s also using the bulk of his book royalties to launch OLY ARTS, an arts and culture magazine with print, online, and mobile app editions. He says he wants to “spread the word about the wonderful artists, actors, writers and musicians in the Olympia area who don’t have the megaphone they need to earn a living wage for the amazing work they do.”

The first OLY ARTS issue’s 10,000 copies were supposed to last 12 weeks. “It sold out in two-and-a-half weeks flat,” Ned says beaming. “So there’s a lot of interest and excitement, and it’s fantastic to know that readers of The Eagle Tree made this all possible.”

Kindle Scout Success Story: Ned Hayes was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 30, 2018

Bookstores: Amazon's Bookstores

If you are a connoisseur of bookstores, like I am, then you might find this to be an unusual post, because despite my previous posts praising the shining stars of the indie book world — mainstays like Kepler’s in Silicon Valley, Powell’s in Portland, Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle, and The Strand in New York — I am now going to praise a new type of bookstore on the scene.

Years ago, Hugh Howey made some great points about why more physical bookstores — even ones created by Amazon — would be a good thing for the larger marketplace of books, and would create a larger reading base overall.

Like writer Hugh Howey, I love Amazon’s new physical bookstores. They’re located in major metropolitian areas, where readers tend to collect and form bookish communities. And these bookstores are amazingly focused on creating the very best readerly experience ever. Hugh Howey has posted a longer piece on his experience with Amazon bookstores. I’m with Hugh, I think these bookstores will definitely move the needle in a positive direction for people who love books.

Like writer Hugh Howey, I love Amazon’s new physical bookstores. They’re located in major metropolitian areas, where readers tend to collect and form bookish communities. And these bookstores are amazingly focused on creating the very best readerly experience ever. Hugh Howey has posted a longer piece on his experience with Amazon bookstores. I’m with Hugh, I think these bookstores will definitely move the needle in a positive direction for people who love books.

Here are a few reasons why I love Amazon’s new bookstores so much. There are comfort-and-reading reasons, and there are commercial reasons, and finally, there are literary reasons. Let me enumerate them one by one.

First, it’s obvious that Amazon Bookstores are employing people who know books well and love books. One of my local indie bookstores is an absolute dream — I love Browsers, and I shop for books there every single week. I know all the staff, and they even pick out books they know I will like. However, I’ve been in bookstores where I am treated like I am an intrusion (I will not name the bookstore). Books are mis-arranged and no one seems to care. They don’t know their local authors. They don’t know their stock, and they don’t seem to really care about building a bookish community. Although Barnes & Noble tries harder (surprisingly), I’m saddened to see their books section gradually getting taken over by other kinds of merchandise.

At Amazon Bookstores, the opposite is true. When I enter the bookstore, I’m greeted by people who clearly know their stock, all the books are face out and easy to read, and they are arranged in “similarity” queues, so if I’m looking for a certain kind of book, I can easily find it. Every book has a review posted, and every book is arranged for optimal scanning. There are troves of books that are good discoveries near at hand, and there is everything I’m looking for in a bookstores. It’s a pure reading pleasure at Amazon Bookstores, and I will be going back many many times.

Second, there are ethical reasons to go with Amazon as a publisher and a retailer. Although there are legitimate questions about a warehouse culture and how they’ve taken over Seattle, there are also good things about Amazon. To start with, as an author, I’d argue that they have essentially saved America from the tyranny of the Big 5 publishers. I know my way around book contracts, and I’ve turned several down because they were seizing IP rights, and treating authors like dirt. Furthermore, their editors were over-worked, under-paid and even ignorant about other imprints within their own publishing house.

Second, there are ethical reasons to go with Amazon as a publisher and a retailer. Although there are legitimate questions about a warehouse culture and how they’ve taken over Seattle, there are also good things about Amazon. To start with, as an author, I’d argue that they have essentially saved America from the tyranny of the Big 5 publishers. I know my way around book contracts, and I’ve turned several down because they were seizing IP rights, and treating authors like dirt. Furthermore, their editors were over-worked, under-paid and even ignorant about other imprints within their own publishing house.

It’s important to note that Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited and Kindle Publishing efforts lit a fire under the nascent world of self-publishing, and have made it possible for many authors to make a living across many domains, from Kathryn Le Veque’s wonderful medieval romances to Hugh Howey’s science-fiction writing. (One wonders why no traditional publisher did this first?) I’ve even put my toe in the water here, self-publishing a few science fiction and horror short stories, and I’ve learned the ropes on self-publishing. My longer novels have been published until recently with smaller traditional publishing houses. However, with my novel The Eagle Tree, I signed with a traditional publishing house owned by Amazon Publishing because their contracts were very fair (David Vandagriff reviews all my contracts), and their editors were absolutely a dream to work with. (I won’t even mention the fact that up until 2015, a traditional big 5 publisher put female authors of color in their own ghetto) Amazon publishing definitely lifts up editors, writers and voices of all genders and backgrounds.

Third, for me there were personal commercial reasons to go with Amazon publishing. You might disagree with these reasons, but the data speaks for itself. The high level takeaways are that Amazon now accounts for up to 79% of all ebooks. Furthermore, it’s not just in ebooks that Amazon is making an impact. The data demonstrates that Amazon is now gaining enormous ground in print book sales, at the expense of Barnes & Noble and big-box retailers primarily (note that indie bookstores are indeed resurgent, which is one thing that my little series on bookstores celebrates!). In fact, up to half of actual printed book sales in the United States are now sold via Amazon. The reach and impact of Amazon is impossible to over-estimate for authors. Amazon knows how people read, and how to reach these readers. That’s why the promotion efforts and publicity that Amazon made so much sense to me, and helped to propel my novel The Eagle Tree to national bestseller status.

Third, for me there were personal commercial reasons to go with Amazon publishing. You might disagree with these reasons, but the data speaks for itself. The high level takeaways are that Amazon now accounts for up to 79% of all ebooks. Furthermore, it’s not just in ebooks that Amazon is making an impact. The data demonstrates that Amazon is now gaining enormous ground in print book sales, at the expense of Barnes & Noble and big-box retailers primarily (note that indie bookstores are indeed resurgent, which is one thing that my little series on bookstores celebrates!). In fact, up to half of actual printed book sales in the United States are now sold via Amazon. The reach and impact of Amazon is impossible to over-estimate for authors. Amazon knows how people read, and how to reach these readers. That’s why the promotion efforts and publicity that Amazon made so much sense to me, and helped to propel my novel The Eagle Tree to national bestseller status.

Finally, it’s clear to me that the literary community writ large has failed the reading public. There’s a real problem when we have a WASP-set of New York City based literati pushing a certain type of Philip-Roth style fiction on the reading public as the highest standard, when the majority of the reading public doesn’t read that kind of fiction. This is a problem for readers, it’s a problem for writers who want to make a living and most of all, it’s a problem for the sustainability of literature. Stephen King has pointed this out multiple times. So have romance authors (who constitute over 50% of all books sold), and science-fiction authors (who sell much better than literary fiction). Hugh Howey, a former bookstore employee and bestselling author, described this situation well in a post:

Part of the problem is that the major publishers ignore the genres that sell the best. This is a head-scratcher, and it nearly caused a bald spot when I was working in a bookstore. I knew where the demand was, and I wasn’t seeing it in the catalogs. Readers wanted romance, science fiction, mystery/thrillers, and young adult. We had catalogs full of literary fiction. Just the sort of thing acquiring editors are looking for and hoping people will read more of, but not what customers were asking me for.

Amazon Bookstores get this big important thing about how people actually read. They use all the reams of data at their disposal to curate a selection of books that are actually of interest to people who actually read. Amazon Bookstores don’t distinguish between some author who received a seven figure advance from some publishing house for his memoirs of picking his nose in Manhattan, or a self-published fantasy author who happens to write about elves and dragons and lives in Montana. They stock the books that people read.

There’s a side question, of course, about whether or not we should treat books as “vegetables” or “dessert.” This little metaphor is meant to illustrate the canard that is sure to rise once I state that we should democratize literature (which is essentially what Amazon Bookstores do for the curated and carefully chosen books on their shelves). Books should be read because they are good for you and improve the world, not just because you enjoy them or are entertained by books. Books should be vegetables — you should read them — not just dessert. I think there’s a middle ground, which is that books can nourish and sustain you, and also be an excellent read. Donna Tartt proved this with her books. So has John Irving. So has Toni Morrison. All of these writers know how to tell a rip-roaring fast-moving story that holds their readers enthralled, yet still communicate deeper, darker, more meaningful truths. These kinds of books are well represented at Amazon Bookstores.

There’s a side question, of course, about whether or not we should treat books as “vegetables” or “dessert.” This little metaphor is meant to illustrate the canard that is sure to rise once I state that we should democratize literature (which is essentially what Amazon Bookstores do for the curated and carefully chosen books on their shelves). Books should be read because they are good for you and improve the world, not just because you enjoy them or are entertained by books. Books should be vegetables — you should read them — not just dessert. I think there’s a middle ground, which is that books can nourish and sustain you, and also be an excellent read. Donna Tartt proved this with her books. So has John Irving. So has Toni Morrison. All of these writers know how to tell a rip-roaring fast-moving story that holds their readers enthralled, yet still communicate deeper, darker, more meaningful truths. These kinds of books are well represented at Amazon Bookstores.

If you love bookstores, you owe it to yourself to visit your local Amazon bookstore and determine for yourself if Amazon is making things better for readers and writers.

Here’s where you can find my books on Amazon

(both online in the physical bookstores)

[Read more BOOKSTORE POSTS]

Pinterest – Ned Hayes Bookstore Board

Bookstores: Amazon’s Bookstores was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 28, 2018

Poem: The Trees

To celebrate Arbor Day 2018 I’m celebrating Arbor Day by posting a poem about trees.

The Trees

by Philip Larkin

The trees are coming into leaf

Like something almost being said;

The recent buds relax and spread,

Their greenness is a kind of grief.

Is it that they are born again

And we grow old? No, they die too,

Their yearly trick of looking new

Is written down in rings of grain.

Yet still the unresting castles thresh

In fullgrown thickness every May.

Last year is dead, they seem to say,

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

from The Collected Poems (Faber, 1993)

[Read more Poetry Posts]

Larkin’s poem was part of the inspiration for my novel THE EAGLE TREE

Poem: The Trees was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 23, 2018

The Procession of the Species

The Procession of the Species comes to life this week in Olympia, Washington!

In my novel The Eagle Tree, my narrator March Wong experiences a wonderful parade entitled the Procession of the Species that showcases many different types of animals and plants. I’ve received many questions from readers about this event, and I’m happy to confirm that YES, the Procession of the Species is a real event!

Readers in the Olympia area know that the Procession of the Species has taken place for two decades in the area, and many children and families have participated for many years in creating new costumes that represent the wide variety of flora and fauna that we can see around the world. My own children have even created costumes for this unique parade, and for years we have loved attending and seeing the creativity of the many Olympia people who create their own unique costumes year after year.

The Procession of the Species has been led by a local community team for many years. You can find out more right here at the Procession website. The Procession is such a unique and wonderful experience that it has been replicated around the world in many other cities and locations, from Portland to Seattle to Maine and Vermont.

Here’s a great set of pictures from the Procession of the Species — taken by Shanna Paxton, the photographer for the local publication OLY ARTS,* who created a photo essay about the Procession last year. I’ve included many of her photos here, so you too can experience the wonder and glory of the Procession of the Species.

In the novel The Eagle Tree, March finds in the Olympia community a welcoming environment for his fascination with trees and natural ecosystems. Olympia is a community that works to be highly aware and engaged with the natural world, and tries hard to support the health of natural ecosystems. This is a large part of the reason that I placed my story in Olympia: March’s voice would be heard in this community in a manner that is much more supported than in other communities who are not as connected to the natural world.

In the novel The Eagle Tree, the Procession of the Species creates a bridge of experience between March’s own interior descriptions of ecosystems and the rest of the world’s experience of those ecosystems. March’s experience of the Procession is immersive and leads to his decision to finally climb The Eagle Tree.

The Procession of the Species exists to empower communities to engage in cultural relationships with the natural world as a means of sustaining efforts of environmental protection and restoration. That’s their mission. Also, the Procession of the Species has a unique set of rules which inspire, nourish, and protect the Procession’s cultural evolution of imagination, creation, and sharing. Here are the only rules they have:

No written or spoken words. We use no words, symbols or lyrics in our art, music or dance.

No pets or live animals. We have no live animals in the Procession, with the exception of Service Animals.

No motorized vehicles. We do not motorize our creations which includes the use of musical amplification. Of course, a motorized wheelchair is certainly permitted.

These rules make the Procession of the Species entirely human-powered, human-created, yet devoid of slogans, signs or other words. The Procession of the Species thus becomes an experiential parade of animal and plant life, where the focus is on the creativity of our own community members and the wonder and glory of the natural world that exists all around us. March Wong would be right at home in the middle of the Procession of the Species.

* Full disclosure: I used the royalties from my bestselling novel The Eagle Tree to found the publication OLY ARTS, and it’s been a surprising success in the Olympia region!

You can read more about OLY ARTS on the publication’s website and listen to Olympia-based podcasts, download Oly Arts mobile apps and read in print and online all about Olympia’s vibrant arts scene.

The Procession of the Species was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 18, 2018

On Writing: What We Talk About When We Talk About Genre

In grad school for English literature (the first time around), I had a professor who had written an entire book on genre. Not “genre” as we typically think of it — that silly label for writing that isn’t characterized as high-art “literature” (like science-fiction and fantasy). She was instead writing about the technical definition of “genre” itself, which means the characteristics of a work that can associate any work with other works of writing. At the time, I thought this was absurd — to write an entire book about the very idea of “genre” itself. But now that I’ve been writing novels for nearly 20 years, I see what an important topic this idea of “genre” is, and why it matters to the working writer.

In grad school for English literature (the first time around), I had a professor who had written an entire book on genre. Not “genre” as we typically think of it — that silly label for writing that isn’t characterized as high-art “literature” (like science-fiction and fantasy). She was instead writing about the technical definition of “genre” itself, which means the characteristics of a work that can associate any work with other works of writing. At the time, I thought this was absurd — to write an entire book about the very idea of “genre” itself. But now that I’ve been writing novels for nearly 20 years, I see what an important topic this idea of “genre” is, and why it matters to the working writer.

As I discuss my work-in-progress with other writers and interested readers, the more I realize what a crucial role knowledge of a genre plays in a writer’s mind. Before I go further in this conversation, let’s make sure we know what we’re talking about when we talk about genre.

The genre of any work of fiction is the basic underlying form or function that the work fulfills: genre defines the rules of the game. If you’re playing chess, you’re going to do fundamentally different things than if you’re playing basketball or baseball. I need to know what game I’m playing in order to play the game at all — much less to play it well. Genre defines the basic rules of the game for any piece of writing.

Some simple examples are the differences between poetry and prose, or the differences between a mystery and a romance. For example, a piece of work that is rhymed, published in short stanzas and concerns itself with metaphorical description over straightforward storytelling is a poem, while the same set of words, re-arranged to be non-rhyming and telling a story that uses fewer metaphors to tell a straightforward story with a recognizable beginning, middle and end is called a prose story.

By the same token, if you’re writing a romance novel, you’re going to do fundamentally different things than if you’re writing a mystery novel or a literary novel. None of these things are bad things to write: yet all of them carry specific rules with them that constrain what you can do, how you can do it, and how far you can go with your work.

Things get more complicated, as you move between one type of poem or story and another. Is a mystery novel with romance primarily a mystery or a romance? J.D. Robb is a mastery at combining genres: so is her novel The Witness a romance or a mystery? By the same token, is a fast-moving action novel with horrific scenes in it primarily a thriller or a horror novel?

Things get more complicated, as you move between one type of poem or story and another. Is a mystery novel with romance primarily a mystery or a romance? J.D. Robb is a mastery at combining genres: so is her novel The Witness a romance or a mystery? By the same token, is a fast-moving action novel with horrific scenes in it primarily a thriller or a horror novel?

The distinction can be found in what predominates in a manuscript or story. If the romance is the preeminent element of a story, it’s a romance, regardless of other elements that are interpolated throughout the story. By the same token, if the psychological and visceral elements that make a good horror novel resonate in the reader are the predominant elements, then a book is a horror novel regardless of what else is happening in the book.

What do we talk about when we talk about genre? To start with, unless we understand the genre we’re working within, we miscommunicate. If I’m trying to write a children’s fantasy book, there are constraints and rules around this genre. If I’m trying to write a mystery, there are also rules. You can play with the rules, and even violate the rules, but you must notify the reader that you’re intentionally doing so, or you look like just a dumb writer who can’t play the game very well.

Now what’s really interesting about genre is that you can play within a genre, but most readers won’t even realize you’re working with that genre on a conscious level. Yet because you’re fulfilling the requirements of the genre, they’re still satisfied by how you’ve built the story. I’d argue, for example, that my novel The Eagle Tree is a romance. The way it is a romance is that the entire story focuses on one person (March Wong’s) love for and obsession with a tree. The romance is between a boy and a tree. Within the romance convention, a writer starts with the love interest early in the story (I begin this romance on page 1) and then most of the novel is concerned with the obstacles that emerge between the two lovers, to separate them (this is also true of The Eagle Tree). But the idea of critical importance in romance — the thing that make a romance a romance — is that there must be consummation. The lovers must finally come together in some meaningful way. And I also carefully adhered to this genre convention — (spoiler!) — as my main character manages to climb the tree he loves by the end of the book. If I’d broken the romance rules in this novel, my readers might have felt cheated, even if they did not consciously realize they were reading a romance.

Now what’s really interesting about genre is that you can play within a genre, but most readers won’t even realize you’re working with that genre on a conscious level. Yet because you’re fulfilling the requirements of the genre, they’re still satisfied by how you’ve built the story. I’d argue, for example, that my novel The Eagle Tree is a romance. The way it is a romance is that the entire story focuses on one person (March Wong’s) love for and obsession with a tree. The romance is between a boy and a tree. Within the romance convention, a writer starts with the love interest early in the story (I begin this romance on page 1) and then most of the novel is concerned with the obstacles that emerge between the two lovers, to separate them (this is also true of The Eagle Tree). But the idea of critical importance in romance — the thing that make a romance a romance — is that there must be consummation. The lovers must finally come together in some meaningful way. And I also carefully adhered to this genre convention — (spoiler!) — as my main character manages to climb the tree he loves by the end of the book. If I’d broken the romance rules in this novel, my readers might have felt cheated, even if they did not consciously realize they were reading a romance.

Tim Power’s grand and world-spanning novel DECLARE is a great example of a true master combining genres. In DECLARE, Powers combines elements of an espionage-driven spy thriller with fantasy. The book is both a spy thriller and a horrific, sorcerous story of magical hijinks that reach across a century of secret warfare.

Tim Power’s grand and world-spanning novel DECLARE is a great example of a true master combining genres. In DECLARE, Powers combines elements of an espionage-driven spy thriller with fantasy. The book is both a spy thriller and a horrific, sorcerous story of magical hijinks that reach across a century of secret warfare.

Yet at the core, this interesting novel doesn’t work unless it is fulfilling all the rules of the spy thriller. A secret mission needs to be fulfilled. espionage action needs to take place, action needs to include uncovering and/or killing enemy agents, there need to be compartmentalized cells that fight against each other: and in the end, all the action needs to have world-shaking consequences for the secret agency that is funding their activities. And in the modern age of John Le Carre novels, the entire aura has to be one of moral ambiguity and ethical gray zones. All these things happen in DECLARE, and this solid fulfillment of genre expectations are fundamentally why DECLARE is so successful as a novel.

The sorcery is secondary. DECLARE needs to be tightly adhering to a single genre before Powers can interpolate other elements on top of that primary genre structure. (I’ve learned this truth to my chagrin in attempting to undertaken a similar type of magic trick in my forthcoming novel Wilderness of Mirrors.)

A recent writerly conversation brought this question of genre to the forefront, when I realized that the writer I was talking to was fundamentally unfamiliar with the genre I was writing in, and therefore was suggesting elements that didn’t fit the genre at all. (As a side note, this is part of why writers must be readers first and foremost — you’ve got to know your genre intimately to understand how the rules work and how to play within and around those rules.)

If someone thinks I’m trying to write in the genre of “literary fiction” (which is a weird little sub-genre that fundamentally doesn’t sell very well, but has a lot of prestige), when I’m really trying to write a straightforward noir mystery, then our discussion of what the novel should be will proceed upon mutually exclusive, mutually misunderstood tracks. A “literary” novel is not a “noir mystery” novel: the two can share many elements, but they are not precisely the same thing in all aspects. And this is the interesting problem with writing fiction — you have to be aware of the rules and the overlaps in order to play the game well. If you are playing on the tune of one genre, and you slip in a beat or a chord from another genre, that’s very cool — but only if you clearly know what you’re doing. If it feels at all happenstance or slipshod to the reader, then the reader feels cheated and uncertain. The reader stops trusting the writer, and at that point, all is lost.

However, when a writer masterfully fulfills the conventions of a genre, readers find the book satisfying. If a writer knows the conventions, demonstrates that they know how to play by the rules and then tweak and violate the rules with a full wink at the reader, then readers find the book joyous. Finally, when a writer knows the conventions, plays within those conventions, and stretches the conventions by adding their own flourishes that expand — but do not violate — the genre conventions, then readers find the book utterly enthralling. And this is the ultimate goal every writer strives to achieve.

A literary update from NedNote.com

Readers can find my books at these bookstores:

On Writing: What We Talk About When We Talk About Genre was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 16, 2018

Poem: Don't Go Into the Library

by Alberto Ríos

The library is dangerous—

Don’t go in. If you do

You know what will happen.

It’s like a pet store or a bakery—

Every single time you’ll come out of there

Holding something in your arms.

Those novels with their big eyes.

And those no-nonsense, all muscle

Greyhounds and Dobermans,

All non-fiction and business,

Cuddly when they’re young,

But then the first page is turned.

The doughnut scent of it all, knowledge,

The aroma of coffee being made

In all those books, something for everyone,

The deli offerings of civilization itself.

The library is the book of books,

Its concrete and wood and glass covers

Keeping within them the very big,

Very long story of everything.

The library is dangerous, full

Of answers. If you go inside,

You may not come out

The same person who went in.

Copyright © 2017 by Alberto Ríos.

[Read more Poetry Posts]

Poem: Don’t Go Into the Library was originally published on Ned Hayes