Ned Hayes's Blog, page 10

April 15, 2018

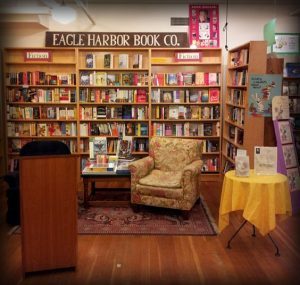

Bookstores: Eagle Harbor Book Company

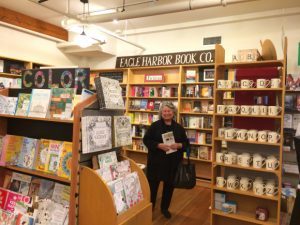

I have a confession to make. Years ago, when I lived in Seattle, I’d take dates on the ferry out to Bainbridge Island, where there’s a lovely little walking district with shops and bars and an absolutely fantastic little bookstore called Eagle Harbor Books. I took dates there to test if they’d have a natural gravitational pull towards the bookstore or not. If clothing shops or drink or food was a more powerful draw to them than books, then they probably weren’t a fit for me. When I finally met someone who said she’d done much the same thing to me — that she wanted to see if I enjoyed Eagle Harbor Books, then I knew I’d met the right person.

I have a confession to make. Years ago, when I lived in Seattle, I’d take dates on the ferry out to Bainbridge Island, where there’s a lovely little walking district with shops and bars and an absolutely fantastic little bookstore called Eagle Harbor Books. I took dates there to test if they’d have a natural gravitational pull towards the bookstore or not. If clothing shops or drink or food was a more powerful draw to them than books, then they probably weren’t a fit for me. When I finally met someone who said she’d done much the same thing to me — that she wanted to see if I enjoyed Eagle Harbor Books, then I knew I’d met the right person.

Eagle Harbor Books is this beautiful little discovery in the middle of Puget Sound. Reached mostly by ferry from the larger city of Seattle, it’s perched in such a way that you can see the saltwater from the store. Shelves are filled with sea lore, and other shelves are filled with Northwest books. Standing here, you feel like you’re walking into a David Guterson novel — and in fact, perhaps you are, because Guterson lives on this island, along with a number of other writers. Among them are such notables as Rebecca Wells, known for Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood.

“We are very lucky on Bainbridge Island–we have some amazing local authors in our community,” Jane Danielson says. She’s the new owner of Eagle Harbor Books — she and her husband purchased the bookstore in 2016, and so far they’re doing a bang-up job revitalizing this wonderful little bookstore at the heart of the Puget Sound.

“We are very lucky on Bainbridge Island–we have some amazing local authors in our community,” Jane Danielson says. She’s the new owner of Eagle Harbor Books — she and her husband purchased the bookstore in 2016, and so far they’re doing a bang-up job revitalizing this wonderful little bookstore at the heart of the Puget Sound.

In the six months since Jane and Dave Danielson bought Eagle Harbor Books (in mid-2016), the store has seen a complete revitalization of its inventory and the beginning of several new community partnerships and event series. The Danielsons have added some 6,000 titles to the inventory at their 4,200-square-foot new and used bookstore.

Fortunately, they aren’t starting from scratch in re-vitalizing Eagle Harbor Books. The Danielsons have a lot of history to build upon. In 1969, “Betty’s Books” opened on Winslow Way with 500 square feet of book selling space. Forty years later, Eagle Harbor Books had expanded to nearly ten times the space, and had become a literary destination. Writers from around the world read here regularly — some even come by boat. Olympia writer Jim Lynch, who I know a little bit, sailed in one evening on his book-tour-by-boat a few years ago (WSJ link) and of course Eagle Harbor Books was high on his itinerary.

There’s one big innovation that the new owners of Eagle Harbor Books have made which is very exciting to me. The Danielsons have added a Teen Advisory Board program. This is a pretty interesting way of engaging young people in books. Teenagers can sign up to receive free advance copies of YA books and write reviews of them. The reviews are then posted in the store and online. Their voices matter at Eagle Harbor Books. Now that’s a great way to give young people a voice in literary culture!

There’s one big innovation that the new owners of Eagle Harbor Books have made which is very exciting to me. The Danielsons have added a Teen Advisory Board program. This is a pretty interesting way of engaging young people in books. Teenagers can sign up to receive free advance copies of YA books and write reviews of them. The reviews are then posted in the store and online. Their voices matter at Eagle Harbor Books. Now that’s a great way to give young people a voice in literary culture!

Now when I visit Bainbridge Island, I’m not checking on my date’s reaction. Instead, I just make a beeline for the bookstore. And if anyone’s up for following me, you can find me back in the corner, thumbing thru the latest David Guterson or Jim Lynch. Whether you you sail in, take the big Seattle ferry or even drive the long way around (thru Poulsbo), it’s worth stopping to browse at Eagle Harbor Books, it’s a gem of the Puget Sound!

Eagle Harbor Book Company is one of my literary touchstones, and I’m happy to share that bookstore experience with my readers! Enjoy!

Find my books at Eagle Harbor Book Company

[Read more BOOKSTORE POSTS]

Pinterest – Ned Hayes Bookstore Board

Bookstores: Eagle Harbor Book Company was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 11, 2018

Poem: The Continuous Life, Mark Strand

(posted on Mark Strand’s birthday – April 11, 1934)

(posted on Mark Strand’s birthday – April 11, 1934)

What of the neighborhood homes awash

In a silver light, of children hunched in the bushes,

Watching the grown-ups for signs of surrender,

Signs that the irregular pleasures of moving

From day to day, of being adrift on the swell of duty,

Have run their course? O parents, confess

To your little ones the night is a long way off

And your taste for the mundane grows; tell them

Your worship of household chores has barely begun;

Describe the beauty of shovels and rakes, brooms and mops;

Say there will always be cooking and cleaning to do,

That one thing leads to another, which leads to another;

Explain that you live between two great darks, the first

With an ending, the second without one, that the luckiest

Thing is having been born, that you live in a blur

Of hours and days, months and years, and believe

It has meaning, despite the occasional fear

You are slipping away with nothing completed, nothing

To prove you existed. Tell the children to come inside,

That your search goes on for something you lost—a name,

A family album that fell from its own small matter

Into another, a piece of the dark that might have been yours,

You don’t really know. Say that each of you tries

To keep busy, learning to lean down close and hear

The careless breathing of earth and feel its available

Languor come over you, wave after wave, sending

Small tremors of love through your brief,

Undeniable selves, into your days, and beyond.

[Read more Poetry Posts]

from Mark Strand’s wonderful book

THE CONTINUOUS LIFE

Poem: The Continuous Life, Mark Strand was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 8, 2018

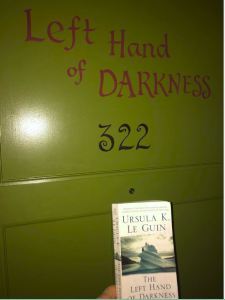

Left Hand of Darkness: A Room

One of the books that rocked my world as a young adult was Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Left Hand of Darkness. The reason this book struck me with such force in young adulthood is that it emphasized different aspects of the typical science-fiction journey.

I read many books about journeys to other planets, other races, other places, future destinations and odd entanglements (most of which ended up in laser gun fire with alien warships of one stripe or another). I read a lot of Heinlein, I must admit, and quite a bit of Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov. Later, I read more John Bruner and Octavia Butler, which contained more ambiguous ideas about alien and advanced human cultures and the implications of space exploration and alien encounters.

But the first book to open my eyes to the possibilities of human evolution, especially on a real personal level, was Le Guin‘s Left Hand of Darkness. This book deals with questions of gender, sexuality, identity, and companionship in harsh terrain. At a time in my life when my own sense of gender was still evolving, the book had a powerful impact, and demonstrated to me what speculative fiction was capable of doing in the hands of a thoughtful writer.

But the first book to open my eyes to the possibilities of human evolution, especially on a real personal level, was Le Guin‘s Left Hand of Darkness. This book deals with questions of gender, sexuality, identity, and companionship in harsh terrain. At a time in my life when my own sense of gender was still evolving, the book had a powerful impact, and demonstrated to me what speculative fiction was capable of doing in the hands of a thoughtful writer.

I suspect the founders of McMenamin’s group of hotels felt much the same way. Because they choose the books and the whimsical ideas that decorate their unique establishments — each of their themed rooms are specifically devoted to an idea or a writer who was important to the Mcmenamin’s founders. I was immensely gratified to find a room named after the book Left Hand of Darkness.

I am a regular and frequent guest at McMenamin’s Grand Lodge in Forest Grove, Oregon. My commute has taken me variously all over the Northwest. In fact, the Seattle Times published an article about my capacity for super-commuting a few years ago. In any case, I stay at McMenimin’s almost every week, and this week, I chose to stay in the Left Hand of Darkness room!

I am a regular and frequent guest at McMenamin’s Grand Lodge in Forest Grove, Oregon. My commute has taken me variously all over the Northwest. In fact, the Seattle Times published an article about my capacity for super-commuting a few years ago. In any case, I stay at McMenimin’s almost every week, and this week, I chose to stay in the Left Hand of Darkness room!

The room was even better than I’d first imagined. Instead of merely having a name on the door, and a copy of the book in the room, the Left Hand of Darkness room has small murals on the bedframes that reflect the central story of the book, of an arduous — nearly mythically hard — companionship in icy terrain on an alien planet that turns into a love affair for two gender-shifting companions.

The room was even better than I’d first imagined. Instead of merely having a name on the door, and a copy of the book in the room, the Left Hand of Darkness room has small murals on the bedframes that reflect the central story of the book, of an arduous — nearly mythically hard — companionship in icy terrain on an alien planet that turns into a love affair for two gender-shifting companions.

It was wonderful to stay in the Left Hand of Darkness room, and to read her work surrounded by such a great paean to her influence and writing. Thanks to McMenamin’s for the Ursula K. Le Guin experience.

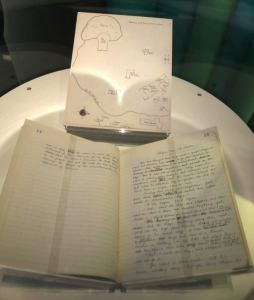

By happenstance, I was able to be in Seattle last week to visit the Museum of Popular Culture (MoPOP). At this Paul Allen founded museum, I re-encountered Ursula K. Le Guin‘s work and influence.

I was very excited to see the actual handwritten manuscript for “The Wizard of Earthsea.” It was great to see that one of seminal books in modern fantasy was hand-created in a lined notebook. Seeing this gave me a lot of encouragement for my own novelistic process of handwriting most of my first drafts and then getting them into the computer. Once again, Ursula K. Le Guin is showing me the writer’s way!

Left Hand of Darkness: A Room was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 4, 2018

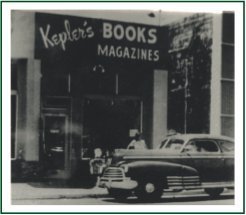

Bookstores: Kepler's Books

Kepler’s bookstore has been part of my life for many decades. The first place my family lived when we moved from Taiwan to the United States in the early 1980s was Sunnyvale California. I am sure that my mother, as an avid reader, visited Kepler’s bookstore in Palo Alto with me in tow. But although I was in fourth or fifth grade, I have no memory of visiting Kepler’s at that time. Instead, my first memories of visiting Kepler’s are on post-college road trips from Washington State to California, when we made regular pitstops in Silicon Valley, stayed with friends or family in the area for a night or two, and visited Kepler’s on the way.

Why visit Kepler’s? Because it was the best and richest book experience in the south San Francisco area – a book refuge in the middle of the intellectually barren software and hardware technology companies. For over 60 years, Kepler’s has been a major intellectual and cultural hub for the Peninsula. On my peripatetic travels through northern California, I always made a point of stopping at Kepler’s.

One particularly significant stop was in 1993, when I did a solo 1500 mile bicycle traverse of the West Coast, from southern California to northern Washington — all the riding time completed in 12 days flat (on some days, I topped 200 miles pedaled!). The days on which I wasn’t riding were spent with family or friends in California, Oregon and Washington. And at my favorite haunts, including restaurants I enjoyed and beautiful bookstores I knew and loved on the West Coast.

One particularly significant stop was in 1993, when I did a solo 1500 mile bicycle traverse of the West Coast, from southern California to northern Washington — all the riding time completed in 12 days flat (on some days, I topped 200 miles pedaled!). The days on which I wasn’t riding were spent with family or friends in California, Oregon and Washington. And at my favorite haunts, including restaurants I enjoyed and beautiful bookstores I knew and loved on the West Coast.

On one particularly memorable hot August day, I bicycled over the Diablo mountain range from the Merced area, and down the other side into San Jose and then on to Palo Alto Valley, where I stayed overnight with a cousin who was in graduate student housing at Stanford University. The next day I peddled over to Kepler’s to pay my allegiance to the best bookstore in the region. In my sweat-stained biking togs I must’ve been an interesting sight, but I still walked out with at least one hardcover (Anne Tyler’s Saint Maybe, as I remember) that I put in my bicycle panniers and subsequently toted with me all the way to Seattle Washington. The book made for some great evening reading by my campfire.

Even though I’d been a fan and a regular for many years, I didn’t know the storied history of the bookstore until quite recently. Here’s a brief version — Kepler’s Books was founded in Menlo Park in May 1955 by peace activist Roy Kepler. Along with Cody’s in Berkeley and City Lights in San Francisco, Kepler’s led the paperback revolution in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 50’s and 60’s. According to their website, Kepler’s “soon blossomed into a cultural epicenter, attracting a loyal following among Beat intellectuals, pacifists, students and faculty of Stanford University, and other members of the surrounding communities, interested in serious books and ideas.” In fact, the Grateful Dead performed at Kepler’s early in their career, and they, along with folk singer Joan Baez, often appeared at Kepler’s holding impromptu salons with local community leaders to discuss ideas, political action, and music.

After the 60s were over, Kepler’s continued with a new generation. In 1980, Roy’s son, Clark Kepler, took over the management of the bookstore. In 1989, Kepler’s moved to its current location in the Menlo Center on El Camino Real. Under Clark’s leadership, Kepler’s expanded its role in the community, developing new partnerships and programs, and winning multiple awards nationally and locally. In 1990 Publishers Weekly named Kepler’s “Bookseller of the Year.”

After the 60s were over, Kepler’s continued with a new generation. In 1980, Roy’s son, Clark Kepler, took over the management of the bookstore. In 1989, Kepler’s moved to its current location in the Menlo Center on El Camino Real. Under Clark’s leadership, Kepler’s expanded its role in the community, developing new partnerships and programs, and winning multiple awards nationally and locally. In 1990 Publishers Weekly named Kepler’s “Bookseller of the Year.”

As the technology revolution swept across the country and changed how people buy things, Kepler’s the bottom line dropped out of Kepler’sbookselling business. Amazon had taken a bite out of the paperback bible. (Oddly enough in the early 1990s, I had the opportunity for a job in the early days of Amazon.com, but I didn’t pursue it because I felt it would take time away from writing novels. I was right on the novel writing front, but wrong on the potential positive impact that an early role as a book review editor at Amazon would’ve had on my life.) In any case, the advent of Amazon and the box big sellers such as Barnes and Noble had a massive negative impact on small bookseller such as Kepler’s.

In 2006, Kepler’s announced it was closing -– the only independent bookseller in the greater Silicon Valley region now dead. Fortunately, there was a massive outcry immediate outcry from the literary public. People knew that they needed a bookstore in Silicon Valley. So the Kepler’s foundation was born, and Kepler’s bookstore resurrected! A new organization — the Kepler’s Foundation — was formed to create events, readings, and additional experiences associated with literate culture, and keep the Kepler’s experiene alive for future generations.

In 2006, Kepler’s announced it was closing -– the only independent bookseller in the greater Silicon Valley region now dead. Fortunately, there was a massive outcry immediate outcry from the literary public. People knew that they needed a bookstore in Silicon Valley. So the Kepler’s foundation was born, and Kepler’s bookstore resurrected! A new organization — the Kepler’s Foundation — was formed to create events, readings, and additional experiences associated with literate culture, and keep the Kepler’s experiene alive for future generations.

I was fortunate to visit the re-vivified Kepler’s bookstore on a nearly weekly basis for a few years. After all, for many years, I’ve worked for my day job for large technology companies who have bases of operation in Silicon Valley, from Adobe to Microsoft to Xerox PARC and Intel. Between 2007-2012, I worked variously as the CEO of a small technology company funded in part by investors in Silicon Valley and as a principal product lead for an R&D team at Xerox PARC, located in Palo Alto, (more on my interesting tech career here).

For a few years, I worked in Palo Alto and commuted down every week from my home in Washington state (my “super commute” was even covered in the Seattle Times). While I was on the road to Palo Alto every week, I made a regular habit of stopping at Kepler’s bookstore to attend author readings, buy books, and check on what new releases piqued my interest. (Occasionally, I’d even stop in at the cigar store next door to sample the wares). My work at Xerox PARC eventually ended and I also sold off my interest in the Valley-funded tech company.

For a few years, I worked in Palo Alto and commuted down every week from my home in Washington state (my “super commute” was even covered in the Seattle Times). While I was on the road to Palo Alto every week, I made a regular habit of stopping at Kepler’s bookstore to attend author readings, buy books, and check on what new releases piqued my interest. (Occasionally, I’d even stop in at the cigar store next door to sample the wares). My work at Xerox PARC eventually ended and I also sold off my interest in the Valley-funded tech company.

But now, as a senior manager at Intel — whose headquarters are in Santa Clara — I have fresh excuses to check in at Kepler’s on a nearly monthly basis (Intel, after all, is kind enough to provide a free air shuttle to all employees for trips to the Valley, and I supervise several team members who are based in the Santa Clara office). So Kepler’s bookstore is once again a big part of my life.

I stopped at Kepler’s most recently a few months ago, to organize a reading near to where many of my friends work in Santa Clara and Palo Alto. I’m also currently a student at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, so I have more reason to be in Silicon Valley, and I’m hoping to do a reading at Kepler’s soon. Along with the rest of the reading community in the Silicon Valley region, I am excited to see where the Kepler’s Foundation takes the future of this important bookstore.

Kepler’s Books is one of my literary touchstones, and I’m happy to share that bookstore experience with my readers! Enjoy!

Find my books at Kepler’s

[Read more BOOKSTORE POSTS]

Pinterest – Ned Hayes Bookstore Board

Bookstores: Kepler’s Books was originally published on Ned Hayes

April 2, 2018

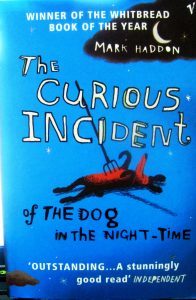

On Writing: The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time by Mark Haddon is the first novel I know of that told the story entirely from the point of view of a person with Autism. There have been other books that dabbled in these waters, but Curious Incident is the first novel that took the full plunge into Autism, and I would argue because it was the first it has mixed success. Because I write books to lift people from darkness and because I believe story has redemptive power, I also found the unrelenting negative reactions to Christopher’s behavior and activities to be different in effect and goals than my own writing.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time by Mark Haddon is the first novel I know of that told the story entirely from the point of view of a person with Autism. There have been other books that dabbled in these waters, but Curious Incident is the first novel that took the full plunge into Autism, and I would argue because it was the first it has mixed success. Because I write books to lift people from darkness and because I believe story has redemptive power, I also found the unrelenting negative reactions to Christopher’s behavior and activities to be different in effect and goals than my own writing.

The novel is written so that Christopher’s point of view is pure in his disconnection from the people around him, and honest in his description of his own behavior. Yet how this behavior plays out – the way that he bounces off other people in a nearly brutal manner – was distressing and I didn’t find it particularly meaningful. It is entertaining, but in much the same way that the movie Trainspotting is entertaining – it’s like watching a car accident for the human carnage, instead of rushing to help the players.

There are many scenes and moments in the story that can be used to illuminate this point, but I’ll just choose one that happens early on in the novel to describe what I mean. When the titular dog dies – as the inciting incident of the novel – Christopher goes to the corpse and his behavior with other people in those moments end up getting him arrested. Here’s the beginning of that scene:

She was shouting “What in fuck’s name have you done to my dog?” I do not like people shouting at me. It makes me scared that they are going to hit me or touch me and I do not know what is going to happen…. I put the dog down on the lawn and moved back 2 meters…. She started screaming again. I put my hands over my ears and closed my eyes and rolled forward till I was hunched up with my forehead pressed onto the grass. The grass was wet and cold. It was nice. (Haddon 4).

Haddon does several things here that are genuine to the situation, the characters, and that show him to be a careful craftsman. First, he shows that by the time Christopher clues into the presence of other people, they are already upset. This is not atypical for even high-functioning people on the spectrum. Second, Haddon gets us firmly inside Christopher’s head and demonstrates how he is feeling (in order, shortly, to justify what comes next). Then, Haddon takes us to behavior that is not neuro-typical, but is a sensation from an inanimate object that Christopher finds soothing. So far, so good.

What happens next adds another player to the mix of activity. One thing I like a lot about Haddon’s work here is that Christopher basically drifts out of the situation entirely, so other people arrive and take action without him even seeming to notice. This happens throughout the novel, and I think it’s fair and exact to the experience of many Aspies – who are absorbed in their own worlds, and are not paying attention to other people as much as neuro-typical people might be paying attention. So another player enters the scene…

I lifted my head off the grass. The policeman squatted down beside me and said “Would you like to tell me what’s going on here, young man?”…. He was asking too many questions and he was asking them too quickly. They were stacking up in my head like loaves in the factory where Uncle Terry works…. The policeman said, “I am going to ask you once again…” I rolled back onto the lawn and pressed my forehead to the grounda gain and made the noise that Father calls groaning. The policeman took hold of my arm and lifted me onto my feet. I didn’t like him touching me like this. And this is when I hit him. (Haddon 6-8)

Again, Haddon does a fine job of demonstrating the disconnection between the policeman’s behavior and Christopher’s reactions. Christopher also has time to describe his own inner sensations (in fact, this description of his inner life goes on rather longer than I’ve allowed for in the paragraph excerpt above). Finally, the policeman does not get what he thinks he needs from Christopher, so he physically interacts with him, leading to disastrous results.

Yet the conclusion of this scene leads me to precisely what I found distressing about the book. Everyone seems to expect Christopher to act “normal,” and when he doesn’t, he immediately gets consequences like being arrested and being treated badly or being lied to, or even being abused in different ways. Although Christopher has a chance to explain himself – to himself – he does not get a chance to explain himself to the world, or to make his voice heard externally. I realize this is a central issue with Autism, but I feel that in the bounds of fiction, it would have been good to go further than just making Christopher a victim.

Curious Incident shows – in spades – the difficulty of interacting with a person on the spectrum, from a parent’s point of view. However, it does not provide enough credence to his own behavior or perspective, or the reasons Christopher might care so deeply about some things or want to figure things out. Christopher is indeed pure in his motivations, but not interesting enough to the reader to over-ride the sense of frustration or disgust that creeps through from his parent’s unspoken perspectives.

I believe Curious Incident didn’t give Christopher enough of a voice, or enough validity as a fully fleshed human being. Instead, it treated a person on the spectrum as someone with essentially the mind of a child. I want to do something different in my fiction: I want to give my main character fully fleshed motivations and desires, that may be valid in his world, even if they are opaque to the “normals” out there in the world. So it’s a fascinating attempt at a novel from the perspective of an autistic person, but one that I feel ends up being too dark, depressing, and frustrating for all concerned.

I supposed I’m a “happy” writer – I believe in happy endings, I believe that characters can be “redeemed” and I believe that all perspectives have value. So I’m pushing hard to have my main character demonstrate enough interest, and enough validity in their point of view that by the end of the novel my audience is cheering for him, instead of turning away in frustration and disgust, as happens (I think) in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time.

I supposed I’m a “happy” writer – I believe in happy endings, I believe that characters can be “redeemed” and I believe that all perspectives have value. So I’m pushing hard to have my main character demonstrate enough interest, and enough validity in their point of view that by the end of the novel my audience is cheering for him, instead of turning away in frustration and disgust, as happens (I think) in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time.

NOTE: After I finished writing this reflection on Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, I published my novel The Eagle Tree and it became a national bestseller, exploring similar themes as Haddon’s book.

A literary update from NedNote.com

Readers can find my books at these bookstores:

Works Cited

Haddon, Mark. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time. New York: Doubleday, 2003. Print.

Robison, John Elder. Look Me in the Eye: My Life with Asperger’s. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007.

Trainspotting. Universal Pictures, 2007. Film.

On Writing: The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time was originally published on Ned Hayes

March 31, 2018

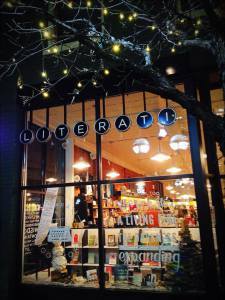

Bookstores: Literati in Anne Arbor

((POSTED ON LITERATI’S 5 YEAR ANNIVERSARY — and my birthday — MARCH 31 !!!))

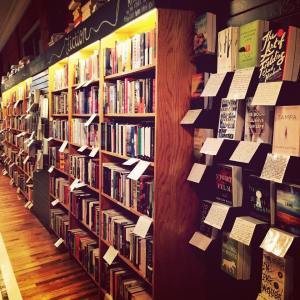

Literati Bookstore is an independent bookstore in downtown Ann Arbor. It’s a wonderful new bookstore that feels fresh, well-designed, digitally capable and knowledgeable, but also fully connected to the history of hardcovers, hand-written book recommendations and their own community.

Although I live nowhere near Michigan, it was wonderful to visit the friendly people at Literati Bookstore, and to see how much they are doing in terms of community outreach, author events and their groundedness in the local bookish world. Now that I’m not there, I love the social media pictures of Literati Bookstore in the Anne Arbor winter snow, and their online pics of author events, both in the bookstore itself as well as at the University of Michigan. I feel like I’m there in person so often at Literati Bookstore, and I find myself ordering online from them, even though I have marvelous local bookstores here in my hometown of Olympia.

What’s really amazing about Literati Bookstore is that it’s relatively new — the bookstore has only been around for only five years.

I’m so excited to have visited Literati in Anna Arbor, and to know that people who care about books are still opening amazing new bookish experiences. The couple who opened the bookstore — Hilary and Mike Gustafson — had a vision for opening a new bookstore in Anne Arbor after the local Borders closed in 2013.

I’m so excited to have visited Literati in Anna Arbor, and to know that people who care about books are still opening amazing new bookish experiences. The couple who opened the bookstore — Hilary and Mike Gustafson — had a vision for opening a new bookstore in Anne Arbor after the local Borders closed in 2013.

Like any good businesspeople, the Gustafsons did a huge amount of research and work prior to opening Literati Bookstore. They had spent quite a bit of time in New York, and enjoyed visiting bookstores across the New York region, including favorite bookstores in Brooklyn and downtown Manhattan. Prior to opening, they also interviewed and talked to over 150 people in the Anne Arbor business community.

Of course, it takes a dynamic team to run such a fantastic bookish experience. They talk about each of their booksellers both in person and on video — people like their inventory lead Jeanne Joesten, their author event organizer John Ganiard, and a wonderful bookseller extraordinaire Claire Tobin, their marketing coordinator. And each of these booksellers are absolutely committing to the mission of the store — you can just tell that each of them are absolutely in love with the books at Literati, and their enthusiasm is contagious.

Of course, it takes a dynamic team to run such a fantastic bookish experience. They talk about each of their booksellers both in person and on video — people like their inventory lead Jeanne Joesten, their author event organizer John Ganiard, and a wonderful bookseller extraordinaire Claire Tobin, their marketing coordinator. And each of these booksellers are absolutely committing to the mission of the store — you can just tell that each of them are absolutely in love with the books at Literati, and their enthusiasm is contagious.

Literati Bookstore is located right in the heart of downtown Anne Arbor, which is a perfect location as the store is only a few blocks from the University of Michigan’s campus. Literati says that it aims to be a place where book lovers can go, talk, and interact with each other.They also host author readings, book clubs, poetry nights, and many other events that make the bookish community a dynamic thing in Anne Arbor.

Literati‘s staff hails from the greater Ann Arbor area, and many have extensive bookselling experience. They are smart enough to partner with collaborate with many Anne Arbor businesses and organizations, including the University of Michigan, 826michigan, Spencer Restaurant, Argus Farm Stop, Vault of Midnight, and many more. Over the last couple years, they acquired the coffeehouse in the same building, and kept it going as a second venue for the Literati community.

Most importantly, Literati says that they believe in the “whimsy that an independent bookstore provides”. I believe in that whimsy as well, so it’s an amazing thing to visit the store.

Here’s one more cool thing about Literati. Almost everything in Literati is repurposed or designed locally. The bookshelves were acquired from a local bookstore that went out of business and their coffee-tables were purchased at local thrift stores and consignment shops, or designed and built right in Michigan. Even the Literati bookmarks were designed by a local graphic designer in Ann Arbor (Alisa Bobzien), while the windows, signs, and bags were designed, hand-painted, and/or constructed by a local artist in Ann Arbor (Samantha Schroeder). Literati Bookstore plans to be around for at least 30 years — and I hope they are there forever!

Here’s one more cool thing about Literati. Almost everything in Literati is repurposed or designed locally. The bookshelves were acquired from a local bookstore that went out of business and their coffee-tables were purchased at local thrift stores and consignment shops, or designed and built right in Michigan. Even the Literati bookmarks were designed by a local graphic designer in Ann Arbor (Alisa Bobzien), while the windows, signs, and bags were designed, hand-painted, and/or constructed by a local artist in Ann Arbor (Samantha Schroeder). Literati Bookstore plans to be around for at least 30 years — and I hope they are there forever!

Literati Bookstore is one of my literary touchstones, and I’m happy to share that bookstore experience with my readers! Enjoy!

Find my books at Literati Books

[Read more BOOKSTORE POSTS]

Watch this amazing documentary by Constant Motion Productions, that tells the Literati Story

Pinterest – Ned Hayes Bookstore Board

Bookstores: Literati in Anne Arbor was originally published on Ned Hayes

March 18, 2018

On Writing: Telling a Story

Telling Stories around a Fire

What does it mean to tell a story? When I think of “telling a story,” I am thinking specifically of the act of verbal storytelling – perhaps around a fire with an audience of people who can leave at any moment. In this situation of verbal storytelling, it’s important to keep your listeners in anticipation of what might come next. It is also helpful to inform them about the world of your story. And to tell them about the kind of story you are telling, and to fulfill that kind of explanation.

Digressions that explain the storyteller’s apprehension of what is to come are most welcome, as such pieces of the “story” build towards satisfying narrative and powerful insights into the characters. On the other hand, self-indulgent words or metaphorical flourishes that detract from the flow of the narrative lose the audience that is collected in the light of the storyteller’s firelit circle.

If you are sitting with a bunch of 11 year old girls by a bonfire, and you begin by saying “I’m going to tell you a scary story,” you darn well better fulfill that expectation. Also, it’s possible to stop your story part way through, and provide some narrative explanation for what is happening to your character (first person or third person). For example, one might pause the forward momentum to observe that “he was really scared now, scared in a way that cuts right down to your bones. You ever felt that way? I know I have, and my blood turns to ice.” Furthermore, you can even digress entirely from the story, as long as you provide an explanation or connection back to the story at hand – for example, I might pause my plot in verbal storytelling, and describe the street of the “scary story” at some length, until I am sure that it is fixed in the reader’s mind.

I’m thinking about this act of verbal storytelling, and how natural it is to “control” our reader’s expectations and inform them about what is happening in your story because I have been reading Donna Tartt’s lovely and rapidly moving literature-as-suspense-novel book The Secret History, in which she describes an insular world of private college upper-classmen who end up committing dastardly deeds (murder of a local farmer, followed by a cover-up murder of one of their own). I began to think about digressions, and how often she undertakes a digression from the “main story plot” in order to tell the reader something else.

I started re-reading Tartt because I grew very bored with two recent novels I’ve read. One was a winner of several literary prizes – Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue – and the other was Tana French’s Broken Harbor, a police procedural that died on the vine. I started thinking then about why I was immediately captured by Tartt, and why I was disappointed in these two novels. I thought of Tartt for two reasons. First, of course, was the fact that her new novel The Goldfinch recently won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. The other is that I have had this quote from Donna Tartt above my writing desk for many years now:

“The first duty of the novelist is to entertain. It is a moral duty. People who read your books are sick, sad, traveling, in the hospital waiting room while someone is dying. Books are written by the alone for the alone” (Tartt Interview 2).[i]

In our work as writers, it is sometimes possible to lose sight of the fact that our ultimate task is simply to tell an entertaining story. All too often, I fear, that our work as writers takes us into extended metaphors, love of language (for language’s sake), experiments with narrative, insertions of different perspectives, and interpolations of authorly opinion, as well as digressions from the text.

All of these tools may help us in our task, but in contemporary fiction – such as in the work of Raymond Carver, Marilynne Robinson, Thom Jones and other New Yorker style “literary fiction” masters – I sometimes fear that we have lost the task of telling a story that “entertains” our audience, and that we no longer understand that if we fail to draw our audience into an active entertainment, we have lost our purpose.[ii]

Here’s one example from Telegraph Avenue. In the middle of this book, Chabon alights on an eight-page uninterrupted, un-paragraphed, nearly unpunctuated monologue that seems excessively full of authorly indulgence. Here’s the beginning of that section: “If sorrow is a consequence of pattern spoiled, then the bird was grieving, seeking comfort in the patter and tap of the baby’s shoes against the wooden floor, Rolando whaling away like Billy Cobham with the heels of his little Air Jordans, working himself around the room…” (Chabon 239). (I’ll stop there as the next period arrives some 5,000 words later) Nothing much happens in these 8 pages – not a single momentous thing occurs, and not a single new insight into character is gained, in my readerly estimation.

Now, it’s worth noting that literary novelists pride themselves on writing about character and personal growth, instead of merely sticking to a rote beginning-middle-end plot cycle. Yet if nothing ever happens to a character – or if the character causes no change in the world – it is frankly difficult for a reader to care about the fate or growth of a character. In contemporary literary circles, I feel that we have fallen too much in love with the sentence, the metaphor and the beautiful language, and creating an articulate narrator. Instead, I think we should focus on telling a story that seizes our reader’s interest.

Let us recall for a moment that idealized scenario I named at the beginning of this short essay – a group of people, gathered around a campfire, enthralled by a storyteller. With this scenario in mind, and the need to seize our reader’s interest: what should one make of the idea of a digression? I mentioned that it’s ok to have some meta-story, or some digressions. But what’s the difference between Chabon’s 8-page indulgent diatribe, and a digression that continues to hold our readers’ interest?

To compare to Chabon’s work, here are a few sentences from near the beginning of Donna Tartt’s novel The Secret History:

“It is easy to see things in retrospect. But I was ignorant then of everything but my own happiness, and I don’t know what else to say except that life itself seemed very magical in those days: a web of symbol, coincidence, premonition, omen. Everything, somehow, fit together; some sly and benevolent Providence was revealing itself by degrees …” (Tartt, Secret History 13)

This particular “digression” is intriguing to the reader because it is essentially setting the stage and reminding the reader of the flow of time – of which a novel is a simulacra and a mockery. It also provides hints and evidences of what is to come – symbols, premonitions, omens. The passage exists to intrigue the reader, not to bore them to death, or to show off the writer’s wordly chops. The ultimate test is this: if we were to transpose these sentences to the fireside, would they sing? I think so.

It may be obvious to the reader by now, but the same digression-as-intrigue works equally well in non-fiction. I am reminded of Joan Didion’s lovely beginning to her classic 1968 essay, Goodbye to All That. Didion writes:

“It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends. I can remember now, with a clarity that makes the nerves in the back of my neck constrict, when New York began for me, but I cannot lay my finger upon the moment it ended, can never cut through the ambiguities and second starts and broken resolves to the exact place on the page where the heroine is no longer as optimistic as she once was.” (Didion 67)

Of course, in reading this passage, the intrigue builds even more profoundly, edging into plot at the end of the passage. First, the passage speaks of the passage of time (Tartt almost mirrors this beginning). Then, the passage gives visceral specific feelings for an abstract event (when New York began), and then a turmoil occurs, leading to the possibility of vast change – the heroine’s attitude transforms. As readers, we want – we must – read on, to find out how this all occurred, and what took place in New York to change our heroine.

Both of these writers step out of the story, to observe the act of storytelling, and make observations about the characters. At one time, I thought that any type of omniscient writing was self-indulgent. But I’ve come to realize that these types of observations are just like the kind of observations necessary in a storytelling moment (like that around a firepit) – in which you need to explain to your audience what is going on, and why it matters. I think the difference between the Chabon indulgence and the careful work done in both the Tartt and the Didion passages is in whether or not the voice is telling us something we need to know to have the story make sense. By the fireside, does it help the listener to care about the story?

Digressions to explain may seem self-indulgent, but if we listen to ourselves in verbal storytelling, we do this all the time. The writers of the mid nineteenth century, with their constant omniscience, and their ability to jump back and forth between characters to weave a better tale, often mirror the common actions of verbal storytelling. In this regard, I think especially of Herman Melville’s digressions about sailing life, ships and whaling in Moby Dick. Those asides add color to the story and explain the situation, and in the end, build towards a stronger plot and greater insight for the characters. Authorial digressions are often meta-story that allow the narrator to comment on your own story.

True storytelling doesn’t give a whit about the particular language used, but propels us through the story itself, and words, language, metaphor (and even characters) serve the purpose of telling a story. Witty digressions and descriptions should not distract from a story, but should add color to it, and add anticipation to that same story. It is worth noting here that that Northwest grand-master of writerly craft – Ursula Le Guin – describes the “involved author” or the “omniscient author” as carrying the “familiar voice of the storyteller, who tells us what has happened, and what has to happen next” (Le Guin 87). Both the Tartt and Didion passages work because they are in the voice of a storyteller who can be trusted to tell us what has to happen next. As readers, we care. And in the end, I think that is all that should matter.

A literary update from NedNote.com

Readers can find my books at these bookstores:

WORKS CITED

Chabon, Michael. Telegraph Avenue. New York: Harper Perennial, 2012.

Didion, Joan. Slouching Towards Bethlehem. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2008.

French, Tana. Broken Harbor. New York: Penguin Books, 2013.

Le Guin, Ursula. Steering the Craft: Exercises and Discussions on Story Writing for the Lone Navigator or the Mutinous Crew. Portland: Eighth Mountain Press, 1998.

McDermid, Val. Quote cited on 11 May 2014. http://www.valmcdermid.com/

Tartt Interview, Donna Tartt. Vintage Anchor Books website. Accessed May 11, 2014. http://vintageanchorbooks.tumblr.com/post/78907850638/the-first-duty-of-the-novelist-is-to-entertain

Tartt, Donna. The Secret History. New York: Vintage, 2011.

END NOTES

[i] A blog entry commented on Donna Tartt’s point: “Every time I read those words, I think of my grandfather, who spent his last few years in a nursing home, dying of Parkinson’s disease. He couldn’t walk or stand or even feed himself; for the last two or three years he could barely talk. What he could still do, though, was read–and read he did, voraciously, day and night, through every one of the stacks and stacks of books my parents and I would bring. And though he would read nearly anything, he loved the romances–the books with a guaranteed happy ending–most of all. And if I have an external reader looking over my shoulder while I work, it’s him–my grandpa, who as he lay in his bed at the nursing home needed stories of hope, stories to remind him of the human spirit’s infinite capacity to triumph over even the most extreme hardship, the most bitter sorrow.”

(See this website for the comment: http://writerunboxed.com/2009/07/17/author-interview-anna-elliott-part-2-needs-intro/#more-1319 )

[ii] I am reminded of this “story telling character” of earlier novels when I read The Corrections (an abominably over-written and indulgent contemporary novel) and compare it to Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell (also a contemporary novel, but one that pushes forward narrative and character development with great relish, and draws water from the same well as 19th century masters such as Jane Austen and the Bronte sisters… and arguably Bram Stoker as well).

On Writing: Telling a Story was originally published on Ned Hayes

March 17, 2018

Poem: My Story in a Late Style of Fire

by Larry Levis

Whenever I listen to Billie Holiday, I am reminded

That I, too, was once banished from New York City.

Not because of drugs or because I was interesting enough

For any wan, overworked patrolman to worry about—

His expression usually a great, gauzy spiderweb of bewilderment

Over his face—I was banished from New York City by a woman.

Sometimes, after we had stopped laughing, I would look

At her & and see a cold note of sorrow or puzzlement go

Over her face as if someone else were there, behind it,

Not laughing at all. We were, I think, “in love.” No, I’m sure.

If my house burned down tomorrow morning, & if I & my wife

And son stood looking on at the flames, & if, then

Someone stepped out of the crowd of bystanders

And said to me: “Didn’t you once know… ?” No. But if

One of the flames, rising up in the scherzo of fire, turned

All the windows blank with light, & if that flame could speak,

And if it said to me: “You loved her, didn’t you?” I’d answer,

Hands in my pockets, “Yes.” And then I’d let fire & misfortune

Overwhelm my life. Sometimes, remembering those days,

I watch a warm, dry wind bothering a whole line of elms

And maples along a street in this neighborhood until

They’re all moving at once, until I feel just like them,

Trembling & in unison. None of this matters now,

But I never felt alone all that year, & if I had sorrows,

I also had laughter, the affliction of angels & children.

Which can set a whole house on fire if you’d let it. And even then

You might still laugh to see all of your belongings set you free

In one long choiring of flames that sang only to you—

Either because no one else could hear them, or because

No one else wanted to. And, mostly, because they know.

They know such music cannot last, & that it would

Tear them apart if they listened. In those days,

I was, in fact, already married, just as I am now,

Although to another woman. And that day I could have stayed

In New York. I had friends there. I could have strayed

Up Lexington Avenue, or down to Third, & caught a faint

Glistening of the sea between the buildings. But all I wanted

Was to hold her all morning, until her body was, again,

A bright field, or until we both reached some thicket

As if at the end of a lane, or at the end of all desire,

And where we could, therefore, be alone again, & make

Some dignity out of loneliness. As, mostly, people cannot do.

Billie Holiday, whose life was shorter & more humiliating

Than my own, would have understood all this, if only

Because even in her late addiction & her bloodstream’s

Hallelujahs, she, too, sang often of some affair, or someone

Gone, & therefore permanent. And sometimes she sang for

Nothing, even then, & it isn’t anyone’s business, if she did.

That morning, when she asked me to leave, wearing only

The apricot tinted, fraying chemise, I wanted to stay.

But I also wanted to go, to lose her suddenly, almost

For no reason, & certainly without any explanation.

I remember looking down at a pair of singular tracks

Made in a light snow the night before, at how they were

Gradually effacing themselves beneath the tires

Of the morning traffic, & thinking that my only other choice

Was fire, ashes, abandonment, solitude. All of which happened

Anyway, & soon after, & by divorce. I know this isn’t much.

But I wanted to explain this life to you, even if

I had to become, over the years, someone else to do it.

You have to think of me what you think of me. I had

To live my life, even its late, florid style. Before

You judge this, think of her. Then think of fire,

Its laughter, the music of splintering beams & glass,

The flames reaching through the second story of a house

Almost as if to—mistakenly—rescue someone who

Left you years ago. It is so American, fire. So like us.

Its desolation. And its eventual, brief triumph.

[Read more Poetry Posts]

Poem: My Story in a Late Style of Fire was originally published on Ned Hayes

March 15, 2018

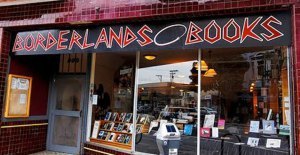

Bookstores: Borderlands in San Francisco

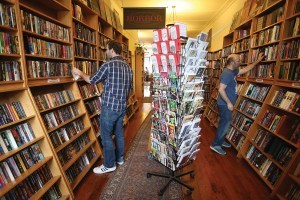

Borderlands Books is a fantastic otherworldly experience in the heart of San Francisco. A specialty store that focuses on science-fiction, fantasy and horror novels, this is a bookstore for a true connoisseur of speculative fiction. I’m not sure if I qualify entirely, as I’m not as well read in the field as I’d like to be. But I do love me some Tim Powers and Ursula Le Guin, and I’m truly deeply madly in love with Nisi Shawl and Octavia Butler’s writing, so sign me up as a fan of Borderlands Books.

Borderlands Books is a fantastic otherworldly experience in the heart of San Francisco. A specialty store that focuses on science-fiction, fantasy and horror novels, this is a bookstore for a true connoisseur of speculative fiction. I’m not sure if I qualify entirely, as I’m not as well read in the field as I’d like to be. But I do love me some Tim Powers and Ursula Le Guin, and I’m truly deeply madly in love with Nisi Shawl and Octavia Butler’s writing, so sign me up as a fan of Borderlands Books.

In fact, I did just that back in 2015. I signed up to be a sponsor of Borderlands Books, and you can do the same thing. In the hot real estate market of San Francisco, bookstores are hardly viable. So literate people of goodwill have signed up to ensure that a great bookstore like this can stay in the city.

BORDERLANDS BOOKS NEEDS SPONSORS every year —

right now, they need new sponsors by March 31st of this year —

You can sign up right here as a sponsor.

You might wonder how all of this came about.

You might wonder how all of this came about.

In 1997 Alan Beatts opened Borderlands Books in Hayes Valley as a used-only bookstore consisting of his personal collection and a selection of books from Know Knew Books in Palo Alto.

Bookstore owner Beatts had done a lot of things before opening his new and used science fiction bookstore. Private Investigator, night club manager, and briefly a used clothing salesman. But he’s stuck to it with Borderlands Books — which is now the largest science fiction bookstore in the United States, carrying 14,000 titles specializing in science fiction, fantasy, and horror.

Borderlands Books is important in SF and fantasy circles, with many author events per year and international tourists popping in daily during busy months. Borderlands Books makes appearances at horror and science-fiction conventions, and has hosted numerous events with a variety of SF/F luminaries, including Lou Anders, Chris Roberson, John Varley, Jacqueline Carey, John Picacio, Graham Joyce, Patricia McKillip, Paolo Bacigalupi, David Drake, Randall Munroe, Steven Erikson, and Cory Doctorow.

Borderlands Books is important in SF and fantasy circles, with many author events per year and international tourists popping in daily during busy months. Borderlands Books makes appearances at horror and science-fiction conventions, and has hosted numerous events with a variety of SF/F luminaries, including Lou Anders, Chris Roberson, John Varley, Jacqueline Carey, John Picacio, Graham Joyce, Patricia McKillip, Paolo Bacigalupi, David Drake, Randall Munroe, Steven Erikson, and Cory Doctorow.

Here’s another nice twist — the café attached to Borderlands Books serves coffee or tea, but they never play music and there is no wi-fi, so that you can simply read books. You can sit and read a new book, or nosh on café treats and read one of the SF magazines also sold at Borderlands. I’ve always thought reading is the point of having a bookstore café, so I’m glad that Borderlands agrees with me.

Borderlands Books also hosts the Tachyon Publications anniversary party with the associated Emperor Norton Awards, given for “extraordinary invention and creativity unhindered by the constraints of paltry reason”. The first award is given to a single work of science fiction, fantasy, or horror, or to an author in these genres, and the second to any creation, creator, or service relating to those genres. In 2008, Borderlands’ owner Alan Beatts and general manager Jude Feldman were jointly nominated for a World Fantasy Award under the World Fantasy Special Award: Professional category.

Despite all this awesomeness, Borderlands couldn’t survive on its own.

Despite all this awesomeness, Borderlands couldn’t survive on its own.

On February 2, 2015, in an open letter posted on Borderlands Books website, the owners Alan Beatts and Jude Feldman, announced they would close the store on March 31, 2015. The Valencia Street store — one of the largest of its kind in the world, specializing in science fiction, fantasy, mystery and horror titles — drew widespread coverage (including a New Yorker piece) after it said the city’s increase in the minimum wage to $15 would not allow it to continue as “a financially viable business” (for the record, the owners support the minimum wage increase).

Then, thanks to a public meeting at which customers proposed ideas for saving the store, a new sponsorship plan was hatched.

Borderlands Books announced a plan to remain open by relying on sponsorships. Soon it seemed that every fan of speculative fiction in the known universe was willing to help out. People from Peter Straub to Neil Gaiman to Joe Hill all sounded the alarm on their social media channels.

“It’s been incredible,” Beatts said. “I had no idea that this would get so much attention from the press, from the public. I was astonished by how many people wanted to get involved.”

“It’s been incredible,” Beatts said. “I had no idea that this would get so much attention from the press, from the public. I was astonished by how many people wanted to get involved.”

The initial goal was merely 300 private sponsors at $100 apiece. This goal was soon surpassed. In fact, the first cohort maxed out at 844 sponsors!

Every year since then, people have signed up to support Borderlands Books, and perhaps the bookstore will even buy their building! (here are some details about the building)

I am proud to say that I was an early supporter of Borderlands Bookstore — here I am, listed under my SF moniker “Nicholas Hallum” as sponsor #214 — one of the first 300 to stand in the gap and defend the bookstore against the forces of avarice and illiteracy! Have I mentioned that you can join us?

You can sign up right here to sponsor Borderlands Books.

Visit Borderlands Books right here.

[Read more BOOKSTORE POSTS]

Pinterest – Ned Hayes Bookstore Board

Bookstores: Borderlands in San Francisco was originally published on Ned Hayes

March 12, 2018

Can Art Save a Life? (Rothko and Pollock)

I read on Brainpickings recently that Mark Rothko, the marvelous abstract expressionist painter, said that when people “weep” when seeing his paintings they are having the same transcendent experience he had when he painted.

Transcendence is an interesting word. It made me remember once when Rothko’s work might just have saved someone’s life.

Ten years ago, I was in divinity school, studying theology and quite seriously considering taking religious orders (albeit as a closet agnostic). Part of my practical training was working as a ER hospital chaplain, and I was on call to comfort the dying and give succor to the injured.

Often, I was called in by hospital doctors or nursing staff to help people find a way towards a peaceful ending or when someone had just experienced a serious loss or accident, and needed to be calmed. Most of the work involved paying attention and simply being present and focused on a person in need. This was a gift to people in short supply in a harried and painful time. It is amazing to me how many staff members – and family members – simply don’t listen to patients in hospitals. So most of what I did was listen.

On one early Saturday morning, I received an emergency call from the hospital. The ER intake nurse needed me there, STAT. A serious accident had occurred, and a survivor of the accident was too agitated. He needed to calm down. They could not medicate him because of his injuries, but they needed him to cease being so agitated. His blood pressure and his agitation were potentially making his injuries worse, and made it hard to do local surgery on him. Would I help?

I said I would come. I did not know if I could help or not, but I could certainly be with him. I had found that sometimes, just being present was help enough.

When I arrived, the staff told me that in the car accident, his friend in the passenger seat had been killed. He had survived, but just barely. We can restrain him, said the intake nurse. But that would be less than ideal. And we can’t medicate him right now. He probably has head injuries.

I went in immediately. In the next room, he was on a hospital bed, and kept trying to leave the hospital, despite his copious injuries, which included a broken leg, perhaps a broken arm, and various contusions and visible injuries. There were probably severe internal injuries too.

He was indeed agitated. He kept wanting to get out of bed, and he cast his head from side to side, talking in a high pitched tone, trying to communicate his fears, his guilt about his friend, asking about what was happening, and how it happened, and why he couldn’t just leave.

I just want to be out of here, out of here, he kept saying.

I asked him questions about himself, trying to change the topic, trying to help him to see himself, and in seeing himself, perhaps to focus inwards, and calm. He told me he was a lapsed Catholic, and then he told me something I thought was important.

I’m a painter, he said. I paint, I make pictures. Abstract expressionism.

Then he went back to trying to leave the hospital. The nurses checked on him, shook their heads. Looked pointedly at me. Take care of this, he needs to calm down, they told me. We need to get him in surgery, and we can only give him a local right now. Get him calmed down.

“You’re feeling like Pollock,” I said. “Jackson Pollock. You know, frenetic, frantic, lots of paint everywhere. Frustrated. Trying to go everywhere. All at once.”

Yes, he said quietly. Yes. Already, his face calmed visibly. Someone knew how he felt. Someone spoke his language.

“The nurses and the doctor, they told me you need to calm down some. Think Rothko, that sense of depth, of color, fields of light. Calm down. Try to move from Pollock to Rothko, ok?”

He looked at me. He nodded slowly, he closed his eyes, and I thought he was drifting in and out of consciousness. But he wasn’t.

Rothko, he said clearly. Rothko. You’re right. He opened his eyes. Now his breathing was no longer a gasp, his pulse almost visibly slowed. His face wasn’t red and upset, and now I could see the lines of a bruise forming under his skin on his neck and shoulder. He had really been banged up in the accident, and now he was coming to know what had happened.

“Rothko,” I repeated in synchronicity with him. Rothko, we said together, thinking of the deep fields of light in the paintings.

A moment later, there was a tear in the corner of his eye.

My friend is gone, isn’t she? Jackie’s gone.

“Yes,” I said. He sighed, he turned his head. Thank you, he said. Then he breathed deep, quiet to the core.

After some time, I stood up and I went out, I told the nurses they could take him into surgery now.

“I hope he does all right. He’s a painter, you know. Abstract.” *

A literary update from NedNote.com

Readers can find my books at these bookstores:

* The actual Rothko quote can be found in Conversations with Artists (public library link)

Can Art Save a Life? (Rothko and Pollock) was originally published on Ned Hayes