Ned Hayes's Blog, page 2

January 16, 2021

MLK Day: A Langston Hughes Poem

The poet Langston Hughes was a great inspiration to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Examples of their connection are expansive. In 1956, King recited Hughes’ poem “Mother to Son” from the pulpit to honor his wife Coretta, who was celebrating her first Mother’s Day. That same year, Hughes wrote a poem about Dr. King and the bus boycott titled “Brotherly Love.” At the time, Hughes was much more famous than King, who was honored to have become a subject for the poet. To honor MLK’s legacy today, here’s Langston Hughes’s famous poem “I, Too.”

The poet Langston Hughes was a great inspiration to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Examples of their connection are expansive. In 1956, King recited Hughes’ poem “Mother to Son” from the pulpit to honor his wife Coretta, who was celebrating her first Mother’s Day. That same year, Hughes wrote a poem about Dr. King and the bus boycott titled “Brotherly Love.” At the time, Hughes was much more famous than King, who was honored to have become a subject for the poet. To honor MLK’s legacy today, here’s Langston Hughes’s famous poem “I, Too.”

[Read more Poetry Posts]

MLK Day: A Langston Hughes Poem was originally published on Ned Hayes

December 22, 2020

Poem: Journey of the Magi (Read by T.S. Eliot)

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sorefooted, refractory,

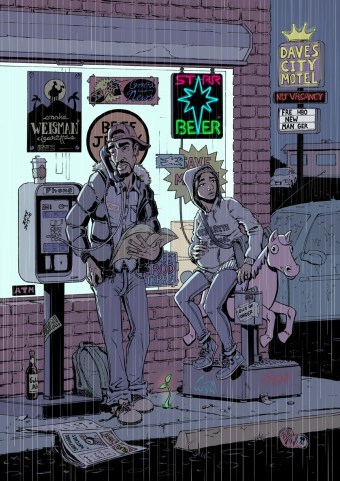

José y Maria by Everett Patterson

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

and running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins.

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arriving at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you might say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

T.S. Eliot, Collected Poems, 1909-1962 (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991).

This poem has been shared here under fair use guidelines provided by The Poetry Foundation.

Poem: Journey of the Magi (Read by T.S. Eliot) was originally published on Ned Hayes

December 14, 2020

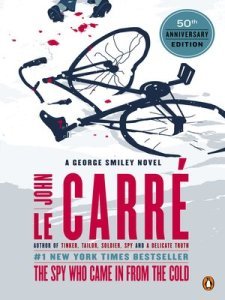

On Writing: Technique & Characterization in John le Carré

Obituary in the Guardian

October 19, 1931 — December 12, 2020

David John Moore Cornwell began writing novels about espionage and spies when he was working as a full-time intelligence agent for the British foreign service MI6 – a group whose very existence was not acknowledged by the British government until 1994. He wrote under the pen name John le Carré (“John the Square” in French) only because foreign intelligence service were forbidden to publish under their own names. When his third novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) became an international best-seller, he left MI6 to become a full-time author, but obviously part of him has always stayed in the intelligence services – for all of his books concern themselves with secrets, lies, espionage and spycraft.

I’ve enjoyed reading John le Carré from time to time over the years, but only really became entranced with his craft last year, when I happened upon his masterwork Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and was enthralled with the subtle humor, the detailed characterizations and the incredibly slow pace of a highly suspenseful novel. How, I wondered, did le Carré manage to maintain tension in a novel that focused on a retired old bureaucrat named George Smiley? Smiley is pudgy, dowdy, old-school English, wears thick glasses, stutters when he talks at all, and when he does speak, expounds in soft syllables. He is a paper-pusher, an analyst, and has probably never held a gun in his life. But somehow, John le Carré makes this novel about Smiley crackle with suspense, and the novel kept me glued to the narrative for 100s of pages. It is a thick book, and a very complicated one, and I even know exactly how it ends, but I never once thought of putting it down. How did he do it?

There are many tools le Carré uses to build his work – like a pointillist master painter, every tidy English scene, every spare sentence and every bit of dialogue builds a gradual picture of enormous tension and incredible momentum. I can’t detail the volumes of education I gained about how to improve my own writing when I analyzed Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and more recently The Russia House, but I can illuminate a few bits of craft that le Carré is teaching me now.

First is the fact that le Carré paints a vivid picture when he describes any character. In fact, le Carré exaggerates when he paints a character. For example, he describes a new character entering a scene with metaphor (not simile) – writing “The first to speak was a distraught, floating man with baby-pink cheeks and baby-clear eyes and a flaxen jacket to match his straggling flaxen hair. His voice floated too” (40).  The vividness of this character description stays with the reader for much of the rest of the book, and from time to time le Carré reinforces it with a slight nod towards the “floating” quality of this man’s look – what is interesting is that this very quality later becomes a plot point, as the Americans distrust this man for his qualities of not-quite-there. le Carré forces readers to see characters as vivid movement on the page, and uses these slightly exaggerated characterizations as a way of burning the character into the reader’s mind, so that there is no doubt what the character is like when he later references them. Painting brightly at the outset allows your characters to last longer in the reader’s mind.

The vividness of this character description stays with the reader for much of the rest of the book, and from time to time le Carré reinforces it with a slight nod towards the “floating” quality of this man’s look – what is interesting is that this very quality later becomes a plot point, as the Americans distrust this man for his qualities of not-quite-there. le Carré forces readers to see characters as vivid movement on the page, and uses these slightly exaggerated characterizations as a way of burning the character into the reader’s mind, so that there is no doubt what the character is like when he later references them. Painting brightly at the outset allows your characters to last longer in the reader’s mind.

The other thing I am beginning to learn from reading closely into le Carré’s work is that a character’s interior life will only take you so far. What I write well, without conscious effort, is interior psycho-drama in which you experience a character’s inner world as they see it, without the intervention of outside elements such as dialogue or even physical descriptions of the surrounding terrain. It is the one thing that literature can do very well that is nearly impossible to replicate in film. For in film, there is no true imaginative interior monologue, no way of seeing the world in terms of interior metaphors and interior voice. There is, of course, the filmic device of a voice-over, but even that doesn’t provide the scrim of dream-like narrative that we as human beings overlay on visceral experience to make a sense-story of life.

We constantly are making a story of everything around us, relating it to other things, and this sense of a world-being-made-of-metaphor is what literature does so very well. When I go out in the world, every person and thing I encounter reminds me of other experiences – I am constantly building a chain of connections between my past experience and my past imaginative life and the life I am currently encountering. I am never just “out of my head” (except perhaps in moments of focused physical attention, such as playing sports or sex). Many great novelists such as DeLillo, Faulkner or McCarthy, spend much of their energy creating a tapestry that resembles this inner life, and that is why their best work is nearly un-filmable.

However, the more I read novelists who are telling a compelling story and are writing for plot, the more I am discovering that good literature can do both psycho-drama and external plot. To establish the point that le Carré is not all about plot and character description, let me first show that le Carré also does the interior psycho-drama thing well. He demonstrates this skill in chapter 7:

She pictured him a waif… lying in semi-darkness on the top berth reserved for luggage, listening to the smokers’ coughing and the grumble of drunks, suffocating from the stink of humanity… while he stared at the appalling things he knew and never spoke of. What kind of hell must that be, she wondered, to be tormented by your own creations? To know that the absolute best you can do in your career is the absolute worst for mankind? (172).

This passage serves as a good synecdoche for the book’s treatment of inner life. It moves clearly from one character’s apprehension of another in the world, and a clear description of how she pictured this person in their ‘waifish’ environment, to her conception of the character’s mindset and concerns. The passage touches on particulars of experience, then implies dark secrets, and then moves naturally to the broader questions of their shared humanity and the big questions of human morality. It is a solid bit of interior monologue.

This passage serves as a good synecdoche for the book’s treatment of inner life. It moves clearly from one character’s apprehension of another in the world, and a clear description of how she pictured this person in their ‘waifish’ environment, to her conception of the character’s mindset and concerns. The passage touches on particulars of experience, then implies dark secrets, and then moves naturally to the broader questions of their shared humanity and the big questions of human morality. It is a solid bit of interior monologue.

What le Carré is beginning to teach me though is how much more powerful such an complex and emotionally full interior space can be when it is prefaced and impacted by events and physical locations that are clearly described and that have action associated with them that has no “discussion” in the reader’s own head. Motion in the exterior world can be as suspenseful and entrancing as motion in the interior world. In The Russia House, le Carré writes mostly a straightforward narrative full of precise observations, character descriptions that are exacting and precise, and dialogue that sings off the page. Here is one sample passage that demonstrates his skill in this critical exterior narrative:

The woman was trembling. Not only with the hands that held her brown perhaps-bag but also at the neck, for her prim blue dress was finished with a collar of old lace and Landau could see how it shook against her skin and how her skin was actually whiter than the lace. Yet her mouth and jaw were set with determination and her expression commanded him.

“Please sir, you must be very kind and help me,” she said as if there were no choice.

….

What happened next happened quickly, a street-corner transaction, willing seller to willing buyer. The first thing Landau did was look behind her, past her shoulder. He did that for his own preservation as well as hers. But his end of the room was empty, the area dark.

“Got it with you then, have you dear?” he asked, peering down and smiling like a friend.

“Yes.”

What I’m learning from le Carré is that very precise description that does not paint with emotion, but instead paints with detail – every detail in the woman’s description denotes terror, every moment adding fear, and the whole scene creates a moment of enormous suspense for both the reader and the characters. Then, le Carré also adds dialogue that has awkward language, but also implores, finished by a commanding note at the end. Finally, there is the rush to action, coupled with the caution of looking around at the crowd. The dialogue is masterful, because it is so spare, with few adverbs at all. Landau, the character, gives a very English reply – he asks about the manuscript, but the manners he use imply that he is trying to be casual, trying to act as if it is of no great concern. Even though we as readers know that the rest of this 400+ page novel depends upon this scene, and even though both characters act as if their lives depend upon what happens with this manuscript handoff, the exchange is a studied moment of casual conversation. This, for me, demonstrates something I could take to heart: casual “throwaway” moments can be just as dramatic – even more so – than moments that are overwrought with adverbs and emotion.

Overall, what is key to learn here for me is the necessity of moving vividly outside the character’s heads and into the world around them in a forceful way. The action can be constrained – as le Carré demonstrates with finesse in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy – but it must be external to the protagonist’s head-talk. If the writer makes the external world come to life in a very real way to the reader, then the internal landscape will matter even more when we return to that inner monologue. The truth is in the intersection between this outer world and this inner world – this is where the writer must make their art.

Since I wrote this post, I was inspired to complete my own spy novel, which is a bit of a twist on the Cold War and War on Terror espionage so well described by le Carré. My novel Wilderness of Mirrors will be released in 2021.

On Writing: Technique & Characterization in John le Carré was originally published on Ned Hayes

December 7, 2020

The Ghost Stories of Charles Dickens

The holiday season sees a million variations on Charles Dickens’s classic A Christmas Carol, yet this marvelous supernatural tale all too often overshadows the ghostly echoes that permeate Dickens’s entire oeuvre.

The holiday season sees a million variations on Charles Dickens’s classic A Christmas Carol, yet this marvelous supernatural tale all too often overshadows the ghostly echoes that permeate Dickens’s entire oeuvre. In John Irving’s book of personal essays, Saving Piggy Sneed, he describes living with the Great Royal Circus in northwest India. One evening, after a circus performance, he was surprised to see children entranced by a televised version of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. These Hindu children didn’t celebrate Christmas, yet they knew the story well – it was “their favorite ghost story.”

We think of A Christmas Carol as the preeminent story of the holidays, but at heart, it’s a ghost story. Dickens told us this fact in his little preface:

I have endeavored, in this Ghostly little book, to raise the ghost of an idea [in] my readers… may it haunt their houses pleasantly.

Christmas Carol is not Dickens’s only eerie tale. In fact, Charles Dickens grew up with ghost stories and he told them everywhere. He told talked of the supernatural as an integral part of the engine that drove his storytelling. “Dickens’s celebration of ghosts,” writes Irving, “…is but a small part of the author’s abiding faith in the innocence and magic of childhood.” For those of us who know Dickens well, ghosts seem to be ever present.

Ghosts first appear in Pickwick Papers, Dickens’s episodic novel. This early book features Mr. Pickwick, Alfred Jingle, Serjeant Buzfuz, Sammer, The Fat Boy, Mr. Winkle and more (doesn’t Dickens have marvelous character names? They’re better than anything in the Simpsons). Embedded in Pickwick Papers is a story called ‘The Lawyer & the Ghost’. There are also multiple tales told by The One-Eyed Bagman – first is ‘The Queer Chair’, about a wayfarer haunted by unusual furniture, and then there’s ‘The Ghosts of the Mail,’ a story of a mail coach carrying unearthly passengers.

More ghostly tales haunt later sections of the Pickwick Papers. ‘A Madman’s Manuscript’ takes us into the insane realm of a man haunted by spectral presences (this psychological horror story would be right at home alongside John Langan’s or Laird Barron’s current work). And the last of the ghost stories in Pickwick points at the future: ‘The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton’ focuses on a miserly character on Christmas Eve who is woken from his curmudgeonly ways by a supernatural figure. The seeds of Scrooge were planted early!

Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens’s third novel, also includes a pair of ghost stories. ‘The Five Sisters’ is a sad fable, while ‘Baron Koeldwethout’s Apparition’ is funny and entertaining during an otherwise slow part of the novel.

In 1843, after Nicholas Nicklebywas published, the idea of Christmas Carol came to Dickens in a flash and he scribbled it down in a frenzy. Christmas Carol combines the best of Dickens. It is not merely a ghost story, but also a comedic tale (like Pickwick) and a redemptive parable (like Nickleby or later, Oliver Twist) G.K. Chesterton, years later, summed up the appeal of the story: “A Christmas Carol is a happy story because it describes an abrupt and dramatic change… the story owes much of its hilarity to the fact of it being a tale of winter and of a very wintry winter. There is much about comfort in the story; yet the comfort is never enervating.”

After the success of Christmas Carol, Dickens kept writing Christmas-themed pieces, but it took 5 more years until he returned to ghosts. In 1848, he delivered The Haunted Man for the holidays. In this tale, a man named Redlaw is haunted by his past and again faces new decisions about his future. Redlaw is reminiscent of Scrooge, but the story doesn’t have the soft focus of Christmas Carol – there’s a harder and more malevolent edge to the ghostly visitation, and a sense of fear appropriate to a truly horrific paranormal story.

Yet Dickens never succumbed to the foreboding that haunted his characters. By 1850, he produced A Child’s Dream of a Star, the story of a girl ascended to heaven as an angel, who awaits the arrival of her brother. Many readers think this story gives insight into Dickens’s own childhood, specifically to his happy days at St. Mary’s, when he was lifted briefly out of deprivation. In the Dickensian, Walter Dexter mentions that “In A Child’s Dream of a Star, [Dickens] refers very touchingly to those days… From an upper window on one side of the house, the Church and Churchyard of St. Mary’s were visible, just as described in this charming story.”

That same year Dickens also produced a short piece called A Christmas Tree, in which he writes about the different types of ghosts one might encounter during the winter season. Other ghostly apparitions emerge in Dickens’ library of work, most published in magazines he edited. Those stories include ‘To Be Read at Dusk,’ ‘The Ghost Chamber’ (which Dickens himself described as “wild”) and ‘The Haunted House.’

Following this period, Dickens wrote two “serious” novels – Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend. But he followed up that literary heavy lifting with two quick short ghost stories – ‘Trial for Murder’ and ‘The Signal-Man.’ The first one is a fantastic atmospheric piece about a man on a jury who is haunted by the murdered man. It’s also interesting to note that the second one – ‘Signal-Man’ – was thought by many readers to have been based on a real apparition, one which made the headlines for years in the United Kingdom. There are many other ghostly stories that have been variously attributed to Dickens, but the final haunting novel that Dickens claimed as his own was his “spooky” and unfinished last work, The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

Following this period, Dickens wrote two “serious” novels – Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend. But he followed up that literary heavy lifting with two quick short ghost stories – ‘Trial for Murder’ and ‘The Signal-Man.’ The first one is a fantastic atmospheric piece about a man on a jury who is haunted by the murdered man. It’s also interesting to note that the second one – ‘Signal-Man’ – was thought by many readers to have been based on a real apparition, one which made the headlines for years in the United Kingdom. There are many other ghostly stories that have been variously attributed to Dickens, but the final haunting novel that Dickens claimed as his own was his “spooky” and unfinished last work, The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

Over the years, I’ve loved reading deeply of Dickens’s oeuvre. It’s amusing and encouraging to realize that such a venerated novelist enjoyed his “childish” ghost stories. In our world today, Dickens would probably be considered a “genre” novelist because he enjoys three things that aren’t found in most of today’s ‘literary’ fiction — broad caricature, a sense of hopefulness (what we’d call ‘sentimentality’ today), and of course, those voices-from-beyond-the-grave that permeate his work. Dickens’s work is full of spooky happenings. His ability to see beyond the mundane and see the inspiration in the ghostly is what makes him such a universally loved storyteller.

FOOTNOTES

Irving was in India doing research for his 1994 novel Son of the Circus.

See Peter Haining’s introduction to The Complete Ghost Stories of Charles Dickens for the exact citation.

A Christmas Tree was published in Household Words, the magazine Dickens edited for many years.

Dan Simmons’s novel Drood was my Christmas read a few seasons ago. Simmons novel is a marvelous tale of spooky happenings and obsessions in Dickens’s own life, narrated by his rival and friend Wilkie Collins. Drood tries to explain the sequence of events that may have inspired Dickens’s last work.

The Ghost Stories of Charles Dickens was originally published on Ned Hayes

November 5, 2020

Remembering Brian Doyle

Today, November 6, is the birthday of Oregon writer Brian Doyle.

I’ve had the great pleasure of getting to know the writing of Brian Doyle this past year. I was introduced to his work by the inimitable Kirstin McAuley at the Oregon Episcopal School, and she’s kindly agreed to allow me to re-post her audio reading of Doyle’s essay from his post-humous book One Long River of Song: Notes on Wonder.

Enjoy Doyle’s wonderful writing voice… and the lovely voice of Kirstin McAuley!

https://nednote.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BrianDoyle-KM.mp3

Brian James Patrick Doyle (1956-2017)

Here’s a short history of Brian Doyle from The Oregon Encyclopedia

Writer Brian Doyle explored the spirit of Oregon’s small towns and the wonders of the world. Describing himself as “a story catcher,” he wrote about spirituality, family, nature, place, wine, and the human heart with a distinctive playful style and zest. The author of over two dozen books, Doyle was also the longtime editor of Portland, the University of Portland’s alumni magazine.

Brian James Patrick Doyle was born in New York City in 1956, into a large Irish-Catholic family with six brothers and one sister. His mother, Ethel Clancey Doyle, was a teacher, and his father, James A. Doyle, was a journalist and the executive director of the Catholic Press Association. He earned a degree in English from the University of Notre Dame in 1978 and worked at the U.S. Catholic and Boston College magazines before moving to Oregon. In Boston, he married Mary Miller, whose artwork appears in several of his books; the couple had three children.

In 1991, Brian Doyle was named the editor of Portland, which he guided to national recognition, most notably with Newsweek’s Sibley Award in 2005. Under his leadership, the magazine published essays not just about the University of Portland but also about beauty, faith, and nature, written by such contributors as Ursula K. Le Guin, David James Duncan, Cornel West, Ian Frazier, James Mattis, Kathleen Dean Moore, and Doyle himself.

Doyle was the author or editor of novels, short fiction, poetry, nonfiction, and essays. As an essayist, he often explored Catholicism and was a regular contributor to America: The Jesuit Review and Guideposts. He described his commitment to his faith in terms of the “genius of Catholicism at its deepest…compassion, witness, reverence, kindness, and tenderness.” From 2004 to 2006, Doyle was the editor of The Best Catholic Writing, an annual volume published by Loyola University Press.

Doyle was a co-author with his father of Two Voices: A Father and Son Discuss Family and Faith (1996). His other nonfiction work includes The Grail (2006), which documents the work of father-and-son winemakers at their vineyard in Dundee, and The Wet Engine (2005), which is about the physical workings of the heart told alongside the story of a life-saving cardiac surgery on one of his infant children. His work also appeared in the Atlantic, Harper’s, the American Scholar, the Oregonian, and the New York Times.

Doyle’s first novel, Mink River (2010), is the story of a fictional town on the Oregon Coast told in the sometimes mystical voices of its struggling inhabitants. The character of Declan O’Donnell, who sailed off into the sunset at the end of Mink River, is featured in his later novel, The Plover (2014). Set in the South Seas and inspired by Doyle’s fascination with the works of Thor Heyerdahl and Robert Louis Stevenson, The Plover combines adventure and mysticism. Chicago (2016) tells the story of a young Notre Dame graduate who takes a job at a Catholic magazine in Chicago in the 1970s and explores the Windy City, and The Adventures of John Carson in Several Quarters of the World (2017) set a fictionalized Stevenson in San Francisco, in homage to nineteenth-century storytelling.

Doyle’s 2015 young adult novel Martin Marten is set on Wy’east, a Native name for Mount Hood. The story intertwines the lives of Dave, a fourteen-year-old boy, and Martin, a pine marten leaving the nest. Martin Marten received the 2016 Oregon Book Award for young adult fiction and the 2017 John Burroughs Medal for Distinguished Nature Writing.

As a novelist, Doyle had a quirky style that suited the energy and mysticism of his writing, often providing the reader with sentient animals and long, adjective-filled, comma-free sentences in a frenzied but ecstatic pace. His writing has been described as “magical realism,” although he rejected that term, telling one interviewer that “I don’t think I write magic realism—I want more to suggest gently that millions more things are possible and real and happening than we know about.” He explained his style this way: “I love runs of adjectives like bursts of salmon in a river.” After Mink River was published, one of his brothers sent him a page consisting of nothing but commas, joking that “you might want to learn to use these.”

Well known in the Oregon literary community, Doyle gave readings and presentations around the state, often leading the audience in a chorus of “Amazing Grace” or regaling them with the story an argument he had with a Buddhist monk about whether soccer or basketball was the better sport. The monk was the Dalai Lama. Doyle’s writing garnered him the Catholic Book Award, three Pushcart Prizes, and an honorary doctorate from the University of Portland, yet he described himself modestly, attributing his interest in writing to his parents.

Brian Doyle died of brain cancer in May 2017. In an interview shortly before the end of his life, he reflected: “If I could say anything to everybody, I would say thank you. I’m quietly very proud to have been called an Oregon writer.”

Remembering Brian Doyle was originally published on Ned Hayes

November 1, 2020

Poem: Invictus

Invictus was the favorite poem of both American Civil Rights firebrand and revered Senator John Lewis, as well as Nelson Mandela, the long-imprisoned and finally triumphant President of South Africa. It seems appropriate on this date to re-read this poem.

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.

Poem: Invictus was originally published on Ned Hayes

October 30, 2020

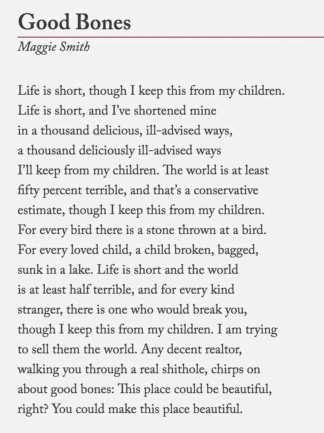

Poem: Good Bones by Maggie Smith

A poem for this moment in our lives… (October 30, 2020)

BY MAGGIE SMITH

Life is short, though I keep this from my children.

Life is short, and I’ve shortened mine

in a thousand delicious, ill-advised ways,

a thousand deliciously ill-advised ways

I’ll keep from my children. The world is at least

fifty percent terrible, and that’s a conservative

estimate, though I keep this from my children.

For every bird there is a stone thrown at a bird.

For every loved child, a child broken, bagged,

sunk in a lake. Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible, and for every kind

stranger, there is one who would break you,

though I keep this from my children. I am trying

to sell them the world. Any decent realtor,

walking you through a real shithole, chirps on

about good bones: This place could be beautiful,

right? You could make this place beautiful.

Read by the poet

https://cdn.simplecast.com/audio/1bf11c/1bf11c14-f329-4a38-b3a4-d5a91aaa46a6/4f5e2257-f3e4-47c0-a37a-08a1098f99f5/693c9700d85be960b56c0bb045134356ccdc8132_tc.mp3

Maggie Smith, “Good Bones” from Waxwing. Copyright © 2016 by Maggie Smith. Reprinted by permission of Waxwing magazine

Poem: Good Bones by Maggie Smith was originally published on Ned Hayes

October 16, 2020

Twelve Terrifying Two Sentence Stories

I found a thread on Reddit that asked this question: “What is the best horror story you can come up with in two sentences?” I posted the best ones I found, as well as one more scary tale I created on my own. See if you can figure out which one is mine! With Halloween right around the corner, these two-sentence terrors fit the month perfectly!

Happy Halloween!

1.

My daughter won’t stop crying and screaming in the middle of the night. I visit her grave and ask her to stop, but it doesn’t help.

My daughter won’t stop crying and screaming in the middle of the night. I visit her grave and ask her to stop, but it doesn’t help.

Image Credit: Fivvr

2.

I woke up to hear knocking on glass. At first, I thought it was the window until I heard it come from the mirror again.

3.

I can’t move, breathe, speak or hear and it’s so dark all the time. If I knew it would be this lonely, I would have been cremated instead.

Image Credit: Public Domain

4.

After working a hard day, I came home to see my girlfriend cradling our child. I didn’t know which was more frightening, seeing my dead girlfriend and stillborn child, or knowing that someone broke into my apartment to place them there.

5.

5.

My sister says that mommy killed her. Mommy says that I don’t have a sister.

Image Credit: Universal

6.

“I can’t sleep,” she whispered, crawling into bed with me. I woke up cold, clutching the dress she was buried in.

7.

7.

I begin tucking him into bed and he tells me, “Daddy, check for monsters under my bed.” I look underneath for his amusement and see him, another him, under the bed, staring back at me quivering and whispering, “Daddy, there’s somebody on my bed.”

Image Credit: Flickr

8.

A girl heard her mom yell her name from downstairs, so she got up and started to head down. As she got to the stairs, her mom pulled her into her room and said, “Don’t go, honey — I heard that, too.”

9.

Yesterday, my parents told me I was too old for an imaginary friend and I had to let her go. They found her body this morning.

10.

10.

In the early morning, I could feel the cat purring against my side, nestled up against me in bed, but the cat smelled of blood. I woke slowly remembering that I had tortured that cat to death last Sunday, and scattered the body parts across the construction site.

Image Credit: DeviantArt

11.

The last thing I saw was my alarm clock flashing 12:07 before she pushed her long rotting nails through my chest, her other hand muffling my screams. I sat bolt upright, relieved it was only a dream, but as I saw my alarm clock read 12:06, I heard my closet door creak open.

12.

12.

The doctors told the amputee he might experience a phantom limb from time to time. Nobody prepared him for the moments though, when he felt cold fingers brush across his phantom hand.

Image Credit: MNN

Nicholas Hallum created a short and chilling tale.

You can ORDER for Kindle here >>

Thank you for your reading and support!

Twelve Terrifying Two Sentence Stories was originally published on Ned Hayes

October 14, 2020

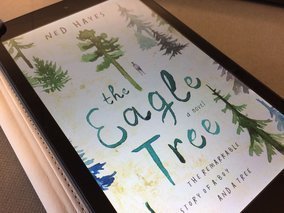

The Eagle Tree: Review by Grace Twomey

In July of 2016 The Eagle Tree by Ned Hayes had been released. The Eagle Tree tells the story of a young boy named March who absolutely loves trees. After finding out that an extremely rare and old tree nearby has been scheduled to be destroyed, he hatches a plan to save it.

The Eagle Tree seems very reminiscent of the popular middle-grade book, Hoot by Carl Hiaasen. However, Hayes tells The Eagle Tree story from a unique perspective. Ned Hayes draws from his extensive experience working with special needs kids to create a main character on the autism spectrum. March falls fairly high on the spectrum. While verbal, the extent of his speaking capabilities remain limited.

Being a single parent proves to be very hard, but being a single parent of a special needs child proves to be even harder. March often struggles to watch out for his own personal safety when climbing trees. This leads to his mother being accused of not being a good parent despite her best efforts. While March tries to keep a nearby forest from becoming destroyed, his mother tries her best to remain in custody of him.

Ned Hayes’ years of experience working with autistic children helps him to create a believable character on the spectrum. Those who have loved ones struggling with autism or Asperger’s Syndrome may enjoy this unique look into the minds of those they love. Even those unfamiliar with the autism spectrum can still enjoy this book and its unique twisting plots.

For fans of Carl Hiaasen or those just looking for a good read, this could be just the book. Overall, I would give it a 4.5 out of 5 stars.

The Eagle Tree: Review by Grace Twomey was originally published on Ned Hayes