Ned Hayes's Blog, page 13

January 19, 2018

Poem: Praying with one eye open

published in 2003, appeared in Seattle School of Theology and Ministry Review

praying with one eye open.

Ned Hayes

(after Mark Strand)

through dark windows,

the clouds move like

one thinks a bird

might, old ghost

caught by light,

scattered feathers

fractured

snow.

on this morning, Pentecost,

tremors of brass

burst the air

yet my eyes

are closed, I am

still

as the Christ

who sleeps on crosses

everywhere, that

dead thing now

and ever.

yet

does some flame still

lip this shore,

rousing

all the mingled mass

of tongues

and what wind unscented

by decay

licks through this space?

what fires flit still

over us

sleeping and waking

enthralled by a divine demon

unto grace?

[Read more Poetry Posts]

Poem: Praying with one eye open was originally published on Ned Hayes

Poem: Elegy

my third published poem, appeared in Lost Creek

Elegy, for Doug Dykstra.

Ned Hayes

(died October 1989, Alaska, age fourteen)

Like woken beasts we staggered awkward through the snow

You might have cried, the strain showing in your cheekbones and

big eyes, when we prayed over your mother But you might have

watched the ropes lowering the first coffin and wondered

The right side of yours was heavier; we faltered under wooden weight

Had you piled gold coins as loot under the lid, or chosen secret

stones to hide there, stolen from Matanuska salmon runs?

Maybe the good shoes were too tight or the boy scout medals superfluous and

you laid them against the side to wait till you could get out and test the

snow with bare feet I think you took a perverse pleasure in the box

slipping, one corner on the rope, while we stood there, sweating and

pulling, our feet cold in the sludge and frosted loam

But all you wanted was to be down, like the time you jumped from the

Slackmeyer’s Big Pine and broke your little toe, in spite of the ladder

You were looking up at the circle of faces, shouting “yes, yes” when the clods

of earth were finally tossed to fall wet and dark and wonderful dirt against the snow,

covering two white boxes in moist loose earth You love the smell of

roots and wild things underneath the ground unfrozen now many months later,

and you are cupping the wriggling earthworms and the curious beetles in

your hand and hoping they will try to escape (you can catch them then)

You’re exploring the light cool dirt and whistling the sap into the grass blades

and struggling flowers and – never before done by a boy – climbing pine trees from the inside

Nothing good is quiet in the spring and you are listening to the

brambles and stretching out to hold the rustle of thistles that can sting

a dog’s nose The smell of full fresh underground is rich, like that old

mine shaft we found at Keewatin or the dug-out with the log ceiling where

you slept alone all summer while we were inside the house

You’d walk in covered with dew and pine needles in the morning

And I still expect you to come in and tell your sister “look what I found while I was buried!”

and hold up yellow knucklebones all on a string with an old watch still ticking,

your treasure, like gold unearthed in a wood box as the pirate lights dim out.

[Read more Poetry Posts]

Poem: Elegy was originally published on Ned Hayes

Poem: Transfiguration

my first published poem, appeared in The Mid-American Review

Transfiguration

Ned Hayes

White men’s bodies turn green under the billows of the sea

I have been told so; when the young are dragged from the tide

their lips have melted into a delicate slash of emerald.

Black bodies turn blue in the brine

none of the longshoremen here notice, there are too many dead;

in Jamaica or Barbados it is rarer. There, the heavy pictish tinge

is obvious — their friends, dark and strangely indigo, found

among the flood of tourist caucasian suicides.

There is a color women’s bodies turn

the change is as oblique as the departure of the soul

when our flesh takes on the scent of waves,

our skin tone melds away.

But no one has ever noticed the change of shade;

these corpses often float for years.

then, sometimes, they return to shore, marry, take up jobs or clean

house, have children, laugh and talk.

I am walking around still, tasting of ocean, undetected.

[Read more Poetry Posts]

Poem: Transfiguration was originally published on Ned Hayes

January 17, 2018

On Writing: Realistic Magic found in the works of Tim Powers & John Bellairs

LAST CALL and HOUSE WITH THE CLOCK IN ITS WALLS

Tim Powers and John Bellairs

Published on John Bellairs Birthday – January 17, 1938!

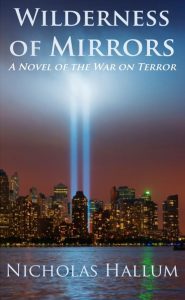

In my spies+sorcery novel Wilderness of Mirrors, I’m trying to write a grounded fantasy that builds on known facts about the Cold War, the War on Terror, 9/11 and the WTC. I am attempting to construct a fantasy that feels as intricate and realistic as the spy novels of John Le Carré. I think I can write a pretty good spy plot, with gun battles, secrets passed in the dark, cryptographic codes to be broken, etc. The tricky part of the novel for me is writing the “fantasy” part, as to this point in my writerly life, I’ve written “straight” contemporary or historical fiction. I also have no desire to craft a world utterly divorced from our reality – a la J.K. Rowling, Tolkien or George R.R. Martin. Instead, I’d like to take the curtain that lies over some 9/11 related events, and simply lift it a little bit, to reveal the edge of “sorcery” behind the scenes. I want any “fantastic” elements to feel as if they are genuine to our reality, and could exist if only someone looked closely enough. So I am looking for models of how to do this effectively.

In my spies+sorcery novel Wilderness of Mirrors, I’m trying to write a grounded fantasy that builds on known facts about the Cold War, the War on Terror, 9/11 and the WTC. I am attempting to construct a fantasy that feels as intricate and realistic as the spy novels of John Le Carré. I think I can write a pretty good spy plot, with gun battles, secrets passed in the dark, cryptographic codes to be broken, etc. The tricky part of the novel for me is writing the “fantasy” part, as to this point in my writerly life, I’ve written “straight” contemporary or historical fiction. I also have no desire to craft a world utterly divorced from our reality – a la J.K. Rowling, Tolkien or George R.R. Martin. Instead, I’d like to take the curtain that lies over some 9/11 related events, and simply lift it a little bit, to reveal the edge of “sorcery” behind the scenes. I want any “fantastic” elements to feel as if they are genuine to our reality, and could exist if only someone looked closely enough. So I am looking for models of how to do this effectively.

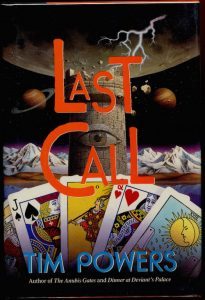

One model can be found in Tim Powers’s Last Call, a book I re-read and marked up in detail this month, specifically because I was in search of his technique of how he did magic+history in a believable way. Powers is the winner of the World Fantasy Award, and one reason that his books stand out from the general glut of fantastic fiction is that he does deep research into history, language and historical style. He also occasionally includes actual historical figures in his fantasy, but carefully written in such a way that they appear quite realistic and grounded in the period. For example, one of his historical fantasy masterworks is The Stress of Her Regard, in which Mary Shelley, Lord Byron and other poetic notables of the period are primary characters. The novel Last Call is only peripherally about the history of the gangster Bugsy Siegel and the founding of Las Vegas. Instead, it is mostly about a seemingly vagabond poker player who finds his lost step-father and has to undertake a bizarre quest back to Las Vegas, where he was abandoned as a child.

One model can be found in Tim Powers’s Last Call, a book I re-read and marked up in detail this month, specifically because I was in search of his technique of how he did magic+history in a believable way. Powers is the winner of the World Fantasy Award, and one reason that his books stand out from the general glut of fantastic fiction is that he does deep research into history, language and historical style. He also occasionally includes actual historical figures in his fantasy, but carefully written in such a way that they appear quite realistic and grounded in the period. For example, one of his historical fantasy masterworks is The Stress of Her Regard, in which Mary Shelley, Lord Byron and other poetic notables of the period are primary characters. The novel Last Call is only peripherally about the history of the gangster Bugsy Siegel and the founding of Las Vegas. Instead, it is mostly about a seemingly vagabond poker player who finds his lost step-father and has to undertake a bizarre quest back to Las Vegas, where he was abandoned as a child.

En route to Las Vegas, Scott (the vagabond), a friend, and Ozzie (the step-father) are pursued by persons unknown. They find a way to evade them, and this is where the magic enters in for the first time in the book. This is the scene I was interested in, because I found the scene very believable, but it violates every natural law I know about. I didn’t have any suspension of disbelief, because my disbelief was accounted for in the scene. Here’s the scene in a nutshell: Ozzie without much notice stops the car and asks Scott and his friend glue plastic deer whistles all over their vehicle, and put playing cards on every other surface, including the wheels. Then they have to prick their fingers and put blood spots on flags and stick the spotted flags out the window. Ozzie doesn’t even tell them what it is for, or why they are doing this. The car is a bizarre sight, and the characters share the reader’s laughter at such strange instructions.

Ozzie doesn’t explain at all what is happening, which heightens the suspense. Ozzie keeps his cards close to his chest, and instead just tells them to do these bizarre things. They follow his instructions with suspicion and hilarity (which nicely mirrors the reader’s disbelief that any of this will work). Because some of the characters share our readerly disbelief in such evident quackery, when it all does work, that fact lands on us as readers with a redoubled gravity. This makes us believe in Ozzie and in the story. Only after the scene is over, does Ozzie explain that they escaped because of these factors:

Those little plastic deer whistles [you two attached all over the car] make a complication of ultrasonic sound waves, all interfering and amplifying and damping each other, and the blood-spotted flags are a lot of organic motion… And then the main thing is the [plethora of playing] cards on the wheels, which are whizzing past the playing cards on the fenders, so…. You get a dozen new combinations of cards…. At a hasty glance, a psychic would tend to assume that there are a lot of people traveling in one vehicle (Powers 169).

As I thought more deeply about the scene, that sleight of hand in terms of withholding of knowledge really worked for me as a reader. It also was true to the sense of the story, and the concealment of fantastic elements, which is part of the plot. Why would a skilled magician or one knowledgeable in magical evasion share any of their secrets with either the reader or the other characters? If Ozzie had led with an explanation, then the “magic” of it working would have disappeared.

I experimented with re-writing the scene, and I quickly found that the best sequence was just as Powers wrote it: 1) Ozzie communicated his bizarre instructions, 2) the characters’ showed disbelief and 3) that in the end it worked, and was 4) afterwards explained later. Since Ozzie was acting in a matter of fact way in doing certain very specific activities – without explaining them – it also makes it evident that he knows precisely what he is doing (even if we don’t know), and it makes it more possible for readers to believe in his activities later on. His behavior is grounded in human reality. We don’t all go about like Hermione in Harry Potter, explaining the magic as we go along. Not explaining it makes it more magical. Withholding the explanation until later is a great plot move.

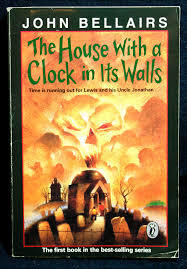

I was also struck by a similar set of bizarre instructions that have real-world grounding in John Bellairs’s classic children’s horror novel The House with the Clock in its Walls. This scene occurs in the penultimate chapter which constitutes the “final showdown.” In this scene, the three main characters – orphan Lewis Barnavelt, Uncle Jonathan and Mrs. Zimmerman – know that they are under threat and must try to discover and battle the plans of an “evil magician.” In the hands of many writers, this scene would be formulaic. The trio would engage in detective work (either through magic or via standard deduction), and then would prepare themselves for a magical battle that would involve wands, spouts of green fire and magical creatures. (One can easily imagine a J.K. Rowling magical scene like this).

I was also struck by a similar set of bizarre instructions that have real-world grounding in John Bellairs’s classic children’s horror novel The House with the Clock in its Walls. This scene occurs in the penultimate chapter which constitutes the “final showdown.” In this scene, the three main characters – orphan Lewis Barnavelt, Uncle Jonathan and Mrs. Zimmerman – know that they are under threat and must try to discover and battle the plans of an “evil magician.” In the hands of many writers, this scene would be formulaic. The trio would engage in detective work (either through magic or via standard deduction), and then would prepare themselves for a magical battle that would involve wands, spouts of green fire and magical creatures. (One can easily imagine a J.K. Rowling magical scene like this).

However, what Bellairs does with the scene is interesting. To this point in the novel, our protagonist Lewis has established himself as a little peculiar, nerdy and unusually inventive for a 13 year old. His Uncle Jonathan is equally zany – if not more so – and is extremely disorganized. Bellairs emphasizes character over magical happenings, and makes us believe even more deeply in his world when he has Uncle Jonathan articulate how these characters have functioned throughout the novel:

We’re no good at that [logical] game. Our game is wild swoops, sudden inexplicable discovers, cloudy thinking…. Lewis, what I want you to do is this. Get a pencil and paper and dream up the silliest set of instructions you can think of. (Bellairs 158)

What follows the instructions written by Lewis is an extremely silly card game and wacky “game” that culminates in finding the “Ace of Nitwits” and the magical object that threatens them. The instructions created by Lewis is very random magic as conceived by a crazy 13 year old, and it foregrounds Lewis without giving him any special abilities. In fact, his lack of special abilities and his zany wit is what makes this chapter fun, and believable. Without Lewis being firmly established as liking these kinds of strange puzzles, the scene would never work: but with that established from chapter one, this action follows so naturally that I cannot now conceive of any other way of finishing the book. In the end, character matters more than special effects to Bellairs.

To sum up my findings on these two magical scenes, I think that two keys to writing “believable” and “grounded” fantasy that seems to be occurring in our reality are as follows: 1) Do not explain what is happening. Provide characters with specific actions that are highly specific and that they believe are “necessary” to cause the effect they want to cause. If the actions are suspect, have other characters voice that suspicion, so the reader’s perspective is embraced. Explain later, and perhaps not even then. 2) Focus on the characters and what they would naturally do. Do not insert magical behavior that does not fit the characters, their motivations, and their behavior to date.

As an addendum to my findings, I’d like to re-emphasize character. If the characters are utterly believable, and the “magic” is utterly believable to the characters themselves, it makes it easier for the reader to believe as well. Writing a fantastic scene should be an outgrowth of a character’s thought process and character development up until that point in the novel, rather than a deus ex machina that just appears or intrudes into the narrative. Writing “realistic” magic is tough, but can be done if one focuses on the basics of realistic human behavior, careful structure in scene dynamics and consistent character motivation as our guiding principles.

A literary update from NedNote.com

Readers can find my books at these bookstores:

Works Cited

Bellairs, John. The House with the Clock In Its Walls. New York: Puffin Books, 1973.

Powers, Tim. Last Call. New York: Avon Books, 1992.

On Writing: Realistic Magic found in the works of Tim Powers & John Bellairs was originally published on Ned Hayes

On Writing: Realistic Magic in Tim Powers & John Bellairs

LAST CALL and HOUSE WITH THE CLOCK IN ITS WALLS

Tim Powers and John Bellairs

Published on John Bellairs Birthday – January 17, 1938!

In my spies+sorcery novel Wilderness of Mirrors, I’m trying to write a grounded fantasy that builds on known facts about the Cold War, the War on Terror, 9/11 and the WTC. I am attempting to construct a fantasy that feels as intricate and realistic as the spy novels of John Le Carré. I think I can write a pretty good spy plot, with gun battles, secrets passed in the dark, cryptographic codes to be broken, etc. The tricky part of the novel for me is writing the “fantasy” part, as to this point in my writerly life, I’ve written “straight” contemporary or historical fiction. I also have no desire to craft a world utterly divorced from our reality – a la J.K. Rowling, Tolkien or George R.R. Martin. Instead, I’d like to take the curtain that lies over some 9/11 related events, and simply lift it a little bit, to reveal the edge of “sorcery” behind the scenes. I want any “fantastic” elements to feel as if they are genuine to our reality, and could exist if only someone looked closely enough. So I am looking for models of how to do this effectively.

In my spies+sorcery novel Wilderness of Mirrors, I’m trying to write a grounded fantasy that builds on known facts about the Cold War, the War on Terror, 9/11 and the WTC. I am attempting to construct a fantasy that feels as intricate and realistic as the spy novels of John Le Carré. I think I can write a pretty good spy plot, with gun battles, secrets passed in the dark, cryptographic codes to be broken, etc. The tricky part of the novel for me is writing the “fantasy” part, as to this point in my writerly life, I’ve written “straight” contemporary or historical fiction. I also have no desire to craft a world utterly divorced from our reality – a la J.K. Rowling, Tolkien or George R.R. Martin. Instead, I’d like to take the curtain that lies over some 9/11 related events, and simply lift it a little bit, to reveal the edge of “sorcery” behind the scenes. I want any “fantastic” elements to feel as if they are genuine to our reality, and could exist if only someone looked closely enough. So I am looking for models of how to do this effectively.

One model can be found in Tim Powers’s Last Call, a book I re-read and marked up in detail this month, specifically because I was in search of his technique of how he did magic+history in a believable way. Powers is the winner of the World Fantasy Award, and one reason that his books stand out from the general glut of fantastic fiction is that he does deep research into history, language and historical style. He also occasionally includes actual historical figures in his fantasy, but carefully written in such a way that they appear quite realistic and grounded in the period. For example, one of his historical fantasy masterworks is The Stress of Her Regard, in which Mary Shelley, Lord Byron and other poetic notables of the period are primary characters. The novel Last Call is only peripherally about the history of the gangster Bugsy Siegel and the founding of Las Vegas. Instead, it is mostly about a seemingly vagabond poker player who finds his lost step-father and has to undertake a bizarre quest back to Las Vegas, where he was abandoned as a child.

One model can be found in Tim Powers’s Last Call, a book I re-read and marked up in detail this month, specifically because I was in search of his technique of how he did magic+history in a believable way. Powers is the winner of the World Fantasy Award, and one reason that his books stand out from the general glut of fantastic fiction is that he does deep research into history, language and historical style. He also occasionally includes actual historical figures in his fantasy, but carefully written in such a way that they appear quite realistic and grounded in the period. For example, one of his historical fantasy masterworks is The Stress of Her Regard, in which Mary Shelley, Lord Byron and other poetic notables of the period are primary characters. The novel Last Call is only peripherally about the history of the gangster Bugsy Siegel and the founding of Las Vegas. Instead, it is mostly about a seemingly vagabond poker player who finds his lost step-father and has to undertake a bizarre quest back to Las Vegas, where he was abandoned as a child.

En route to Las Vegas, Scott (the vagabond), a friend, and Ozzie (the step-father) are pursued by persons unknown. They find a way to evade them, and this is where the magic enters in for the first time in the book. This is the scene I was interested in, because I found the scene very believable, but it violates every natural law I know about. I didn’t have any suspension of disbelief, because my disbelief was accounted for in the scene. Here’s the scene in a nutshell: Ozzie without much notice stops the car and asks Scott and his friend glue plastic deer whistles all over their vehicle, and put playing cards on every other surface, including the wheels. Then they have to prick their fingers and put blood spots on flags and stick the spotted flags out the window. Ozzie doesn’t even tell them what it is for, or why they are doing this. The car is a bizarre sight, and the characters share the reader’s laughter at such strange instructions.

Ozzie doesn’t explain at all what is happening, which heightens the suspense. Ozzie keeps his cards close to his chest, and instead just tells them to do these bizarre things. They follow his instructions with suspicion and hilarity (which nicely mirrors the reader’s disbelief that any of this will work). Because some of the characters share our readerly disbelief in such evident quackery, when it all does work, that fact lands on us as readers with a redoubled gravity. This makes us believe in Ozzie and in the story. Only after the scene is over, does Ozzie explain that they escaped because of these factors:

Those little plastic deer whistles [you two attached all over the car] make a complication of ultrasonic sound waves, all interfering and amplifying and damping each other, and the blood-spotted flags are a lot of organic motion… And then the main thing is the [plethora of playing] cards on the wheels, which are whizzing past the playing cards on the fenders, so…. You get a dozen new combinations of cards…. At a hasty glance, a psychic would tend to assume that there are a lot of people traveling in one vehicle (Powers 169).

As I thought more deeply about the scene, that sleight of hand in terms of withholding of knowledge really worked for me as a reader. It also was true to the sense of the story, and the concealment of fantastic elements, which is part of the plot. Why would a skilled magician or one knowledgeable in magical evasion share any of their secrets with either the reader or the other characters? If Ozzie had led with an explanation, then the “magic” of it working would have disappeared.

I experimented with re-writing the scene, and I quickly found that the best sequence was just as Powers wrote it: 1) Ozzie communicated his bizarre instructions, 2) the characters’ showed disbelief and 3) that in the end it worked, and was 4) afterwards explained later. Since Ozzie was acting in a matter of fact way in doing certain very specific activities – without explaining them – it also makes it evident that he knows precisely what he is doing (even if we don’t know), and it makes it more possible for readers to believe in his activities later on. His behavior is grounded in human reality. We don’t all go about like Hermione in Harry Potter, explaining the magic as we go along. Not explaining it makes it more magical. Withholding the explanation until later is a great plot move.

I was also struck by a similar set of bizarre instructions that have real-world grounding in John Bellairs’s classic children’s horror novel The House with the Clock in its Walls. This scene occurs in the penultimate chapter which constitutes the “final showdown.” In this scene, the three main characters – orphan Lewis Barnavelt, Uncle Jonathan and Mrs. Zimmerman – know that they are under threat and must try to discover and battle the plans of an “evil magician.” In the hands of many writers, this scene would be formulaic. The trio would engage in detective work (either through magic or via standard deduction), and then would prepare themselves for a magical battle that would involve wands, spouts of green fire and magical creatures. (One can easily imagine a J.K. Rowling magical scene like this).

I was also struck by a similar set of bizarre instructions that have real-world grounding in John Bellairs’s classic children’s horror novel The House with the Clock in its Walls. This scene occurs in the penultimate chapter which constitutes the “final showdown.” In this scene, the three main characters – orphan Lewis Barnavelt, Uncle Jonathan and Mrs. Zimmerman – know that they are under threat and must try to discover and battle the plans of an “evil magician.” In the hands of many writers, this scene would be formulaic. The trio would engage in detective work (either through magic or via standard deduction), and then would prepare themselves for a magical battle that would involve wands, spouts of green fire and magical creatures. (One can easily imagine a J.K. Rowling magical scene like this).

However, what Bellairs does with the scene is interesting. To this point in the novel, our protagonist Lewis has established himself as a little peculiar, nerdy and unusually inventive for a 13 year old. His Uncle Jonathan is equally zany – if not more so – and is extremely disorganized. Bellairs emphasizes character over magical happenings, and makes us believe even more deeply in his world when he has Uncle Jonathan articulate how these characters have functioned throughout the novel:

We’re no good at that [logical] game. Our game is wild swoops, sudden inexplicable discovers, cloudy thinking…. Lewis, what I want you to do is this. Get a pencil and paper and dream up the silliest set of instructions you can think of. (Bellairs 158)

What follows the instructions written by Lewis is an extremely silly card game and wacky “game” that culminates in finding the “Ace of Nitwits” and the magical object that threatens them. The instructions created by Lewis is very random magic as conceived by a crazy 13 year old, and it foregrounds Lewis without giving him any special abilities. In fact, his lack of special abilities and his zany wit is what makes this chapter fun, and believable. Without Lewis being firmly established as liking these kinds of strange puzzles, the scene would never work: but with that established from chapter one, this action follows so naturally that I cannot now conceive of any other way of finishing the book. In the end, character matters more than special effects to Bellairs.

To sum up my findings on these two magical scenes, I think that two keys to writing “believable” and “grounded” fantasy that seems to be occurring in our reality are as follows: 1) Do not explain what is happening. Provide characters with specific actions that are highly specific and that they believe are “necessary” to cause the effect they want to cause. If the actions are suspect, have other characters voice that suspicion, so the reader’s perspective is embraced. Explain later, and perhaps not even then. 2) Focus on the characters and what they would naturally do. Do not insert magical behavior that does not fit the characters, their motivations, and their behavior to date.

As an addendum to my findings, I’d like to re-emphasize character. If the characters are utterly believable, and the “magic” is utterly believable to the characters themselves, it makes it easier for the reader to believe as well. Writing a fantastic scene should be an outgrowth of a character’s thought process and character development up until that point in the novel, rather than a deus ex machina that just appears or intrudes into the narrative. Writing “realistic” magic is tough, but can be done if one focuses on the basics of realistic human behavior, careful structure in scene dynamics and consistent character motivation as our guiding principles.

A literary update from NedNote.com

Readers can find my books at these bookstores:

Works Cited

Bellairs, John. The House with the Clock In Its Walls. New York: Puffin Books, 1973.

Powers, Tim. Last Call. New York: Avon Books, 1992.

On Writing: Realistic Magic in Tim Powers & John Bellairs was originally published on Ned Hayes

January 15, 2018

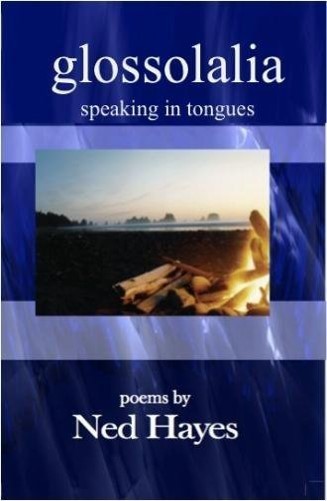

Glossolalia: Collected Poems

Glossolalia: speaking in tongues is a powerful poetic exploration of the last years of the 20th century, spoken in a multitude of interlocking tongues. A deep exploration of human experience, ranging from loss and genocide to joy and childbirth, Ned Hayes uses a multivalent language, ranging widely from ancient mythic tropes to modern slang.

Glossolalia: speaking in tongues is a powerful poetic exploration of the last years of the 20th century, spoken in a multitude of interlocking tongues. A deep exploration of human experience, ranging from loss and genocide to joy and childbirth, Ned Hayes uses a multivalent language, ranging widely from ancient mythic tropes to modern slang.

Poetry in this volume was originally published in literary journals and magazines between 1991-2013.

Publishing journals included Mid-American Review, Amelia, Simul, Seattle Theology, TWIG, and many more.

Glossolalia: Collected Poems was originally published on Ned Hayes

January 14, 2018

Bookstores: Browsers Bookstore in Olympia

Read at Browsers Bookshop When I moved to Olympia Washington in 2003, I had no idea that this was the town in which my bestselling novel The Eagle Tree would be set, and I had no idea that I’d gradually fall in love with this city, establish an arts magazine that extolled the wonders of the local arts scene, and find such a supportive community of fellow artists, writers and creative souls here. Back then, the city was a little funky, still dealing with the hangover of being America’s first “grunge” capital (birthplace of Nirvana, K-Records, and Riot Grrrl), and the recent shut-down of its namesake brewery.

One of the funky experiences was a little downtrodden used bookstore on the edge of downtown. Browsers Bookstore had been there since 1935, but in recent years the cover had been worn, the spine split, a few pages were missing and there were dust on the shelves. I loved it.

Here in this little used bookstore, I could find a nearly-forgotten old academic tome on Milton, an acid-stained leftover Hunter S. Thompson from the 1960s and a cheap Stephen King or Tim Powers paperback. You had to be willing to brave the netherlands of used bookstore back-shelves, but if you dug deep enough, you could make serendipitous discoveries.

In the mid-2000s, I left Olympia for a few years for a graduate fellowship, and just a few short years after my family and I returned, Browsers had a bit of a resurrection. A wonderful new owner — Andrea Griffith — had taken ownership of the bookstore. She had big plans!

Over a two year period, Andrea gradually transformed the bookstore into a shining jewel — a pocket bookstore where a revitalized and fully used upstairs buzzed with the sound of book discussion groups and writer confabs, while downstairs freshly organized shelves groaned under the weight of face-out new editions, featured new releases and special introductions to local authors and literary luminaries. Andrea proved to have extraordinarily well-refined taste in books, and her picks meet readers right where they need a literary jolt. Now Browsers Bookshop wasn’t just about used books and unexpected finds, but instead showcased the best of brand-new Northwest reading alongside the pick of world fiction and non-fiction.

Browsers has a wonderful history, and it’s lovely to see Andrea build on that history. Browsers Bookshop has been in downtown Olympia for 80 years. In that 80 years, four different women have owned the store. Browsers originally began in Aberdeen in 1935 as Anna Blom’s Book Shop. Anna was a Russian Jewish immigrant, born in 1884. She was self-educated, well-read and intelligent. After she divorced and with two young children, she relocated her bookstore to Olympia on the advice of the Washington Supreme Court Judge Walter Beals, who thought Olympia might better support a bookshop during the Depression.

Browsers has a wonderful history, and it’s lovely to see Andrea build on that history. Browsers Bookshop has been in downtown Olympia for 80 years. In that 80 years, four different women have owned the store. Browsers originally began in Aberdeen in 1935 as Anna Blom’s Book Shop. Anna was a Russian Jewish immigrant, born in 1884. She was self-educated, well-read and intelligent. After she divorced and with two young children, she relocated her bookstore to Olympia on the advice of the Washington Supreme Court Judge Walter Beals, who thought Olympia might better support a bookshop during the Depression.

According to Browsers‘ website and conversation with Andrea, Anna Blom’s Bookshop was first located on east Fourth Avenue, about three blocks east of Capitol Way. In 1968, Anna sold her shop to Ilene Yates, a former schoolteacher who changed the name of the shop to Browsers and eventually bought the building where Browsers is now, 107 Capitol Way. The building was for many years a tavern and needed quite a lot of work in order to make the transition from bar to bookstore. Only the front half of the shop was used and when Jenifer Stewart, one of Ilene’s employees, bought the shop in 1985, she worked to renovate the back half to also house books. Jenifer raised her two daughters while running the shop for nearly 30 years. Andrea Griffith took over in late 2014. As Andrea writes, “Browsers continues on, providing just the right book to just the right reader.”

In 2016, I was so excited to partner with Andrea to host my very first launch event for The Eagle Tree, which featured actors and readers like Amy Shepherd, who has been seen on stage at Harlequin Productions, Olympia Family Theater and the Broadway Center for the Performing Arts and Clarke Hallum, recently seen as “Wilbur” in Olympia Family Theater’s production of Charlotte’s Web and known for his starring role in A Christmas Story at 5th Avenue Theater in Seattle. The event also was the first big author reading for the revitalized and re-born Browser’s Bookshop in Olympia. I’m happy to report that there was standing-room only at the event.

In 2016, I was so excited to partner with Andrea to host my very first launch event for The Eagle Tree, which featured actors and readers like Amy Shepherd, who has been seen on stage at Harlequin Productions, Olympia Family Theater and the Broadway Center for the Performing Arts and Clarke Hallum, recently seen as “Wilbur” in Olympia Family Theater’s production of Charlotte’s Web and known for his starring role in A Christmas Story at 5th Avenue Theater in Seattle. The event also was the first big author reading for the revitalized and re-born Browser’s Bookshop in Olympia. I’m happy to report that there was standing-room only at the event.

Subsequently, many other authors and readers have been fortunate to experience Browser’s Bookshop warm hospitality and welcoming audiences, including such literary luminaries as Nancy Pearl, Maria Mudd Ruth, Jim Lynch and Nikki McClure.

Browser’s Bookshop is now truly one of the best bookstores on the West Coast. I’m excited to feature Andrea’s beautiful place as the first in a new ongoing series about my favorite bookish places.

Browser’s Bookshop is one of my literary touchstones, and I’m happy to share that bookstore experience with my readers! Enjoy!

Find my books at Browsers

[Read more BOOKSTORE POSTS]

Pinterest – Ned Hayes Bookstore Board

Bookstores: Browsers Bookstore in Olympia was originally published on Ned Hayes

January 7, 2018

A Tree -- at the Seattle Art Museum

Middle Fork

Over the holiday break, my family had the great pleasure of visiting the Seattle Art Museum (SAM) again. Years ago, I met Bill Gates at a private gathering here, and I’ve had many wonderful experiences at SAM. This time, I didn’t meet any celebrities, but instead I was enthralled with the enormous and wonderful tree sculpture that fills the ceiling of the lobby. I feel that March Wong from my novel THE EAGLE TREE would have been even more enthralled and joyous at the vast tree that filled the air of SAM.I’d like you to enjoy this tree as well, so I’ve created a bit of a photo-essay here by using photos of the tree sculpture here, as well as more details on the sculptor and the process that created this tree, drawn from SAM’s page on the artwork which is by artist John Grade and entitled “Middle Fork”. And interspersed are several relevant quotes from THE EAGLE TREE. Enjoy!

John Grade’s large-scale sculpture, Middle Fork, echoes the contours of a 140-year-old western hemlock tree located in the Cascade Mountains east of Seattle.

Ahead of me, I saw a Western Hemlock. I called out to it its true name too — “Tsuga heterophylla.” Then I jumped up on top of an ancient giant nurse log, and I could look across a small meadow at a field of young trees. This was a clear-cut, and the trees were growing back, but the cut-over had probably been there since the time I was born. I looked across the growing trees, and I could see the tips of some of them droop. The drooping ones were Western Hemlocks. — The Eagle Tree

Beginning by making a full plaster cast of the living tree, the artist and a cadre of volunteers used this mold to recreate the tree’s form out of thousands of pieces of reclaimed old-growth cedar. Middle Fork was conceived and fabricated at MadArt Studio and made its Seattle debut there in January 2015. The original work was 40-feet long and will more than double in length for its installation.

At forty feet, the sky is entirely black, but now starlight bleeds faintly down into the forest from between rushing gray clouds. The wind is picking up as well. I can feel it catch at my coat as I twist above the branches. Along with the wind pushing me, it also pushes the branches I am relying on, in one direction or another, back and forth. That means that when I reach out with the clear memory map I have kept from the ground, the limbs I reach for have moved several inches in the wind to the right or the left, so I must fumble in the air before I can grip them again. — The Eagle Tree

About the Artist

Grade’s work is exhibited internationally in museums, galleries, and outdoors in urban spaces and nature. His projects are designed to change over time and often involve collaboration with large groups of people. He lives and works in Seattle.

THE EAGLE TREE was published by Little A. The book sold over 80,000 copies to become a national bestseller and was listed in 2016 as one of Top 5 Books on the Autistic experience.

Buy THE EAGLE TREE at indie bookstores, Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

A Tree — at the Seattle Art Museum was originally published on Ned Hayes

January 4, 2018

Bookstores: The Strand in New York City

In 2018, I’m writing a short series of posts on bookstores I know and love. The series was due to begin in early February, and I’ve already written love letters (not yet published) to many of the bookstores I love, and told you exactly why you should visit so many of these lovely bookish communities.

In 2018, I’m writing a short series of posts on bookstores I know and love. The series was due to begin in early February, and I’ve already written love letters (not yet published) to many of the bookstores I love, and told you exactly why you should visit so many of these lovely bookish communities.

However, I decided to begin my Bookstore Series earlier than I expected, when I read the obituary for a legend of the bookselling trade whom I have met and whose bookstore I enjoyed.

Strand Books in New York City is a legend for people who love bookstores, and I had the pleasure of visiting the Strand nearly every time I went to New York and even spending time chatting with the inimitable Fred Bass, who is featured in this wonderful obit in this week’s New York Times. To be clear, I got to know Mr. Bass only perfunctorily, by way of asking about books and talking about books. But as we both enjoyed the conversation. There are few people who seemed to have so much interest in knowing the exact catalog of over “18 miles of books,” so I’ll miss him and his bookish knowledge tremendously.

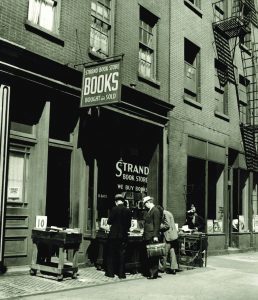

Strand Books in 1938 (Photo via Strand)

Strand Books began in the 1930s, in a district long known for books. Back in the early 1900s, an entire book district covered Fourth Avenue from from Union Square to Astor Place. Fred began working for his father in this bookselling district back when he was 13 years old in 1928. Back then, many bookstores in bookseller’s row had particular specialties and antiquarian interests and Strand Books was only one among many. Yet Fred persevered. (Remind me to set a librarian-magician story in NYC’s classic bookstore district!)

Strand Books eventually moved to Broadway and began expanding under Fred Bass’s leadership in 1956. Now at Broadway on 12th Street, Strand Books took over half the ground floor of what had been a clothing store. Eventually, Strand Books took over three floors of the building and eventually added an antiquarian books department. By the late 1960s, Strand Books was the only surviving bookstore from old bookstore row in New York city.

He loved buying books. “It’s a disease,” he told New York magazine in 1977. “I get an attack, something like a panic, of book-buying. I simply must keep fresh used books flowing over my shelves.”

Fred Bass in the 1970s (Photo via Strand)

As the New York Times article points out, Fred Bass nearly single-handedly grew Strand Books into the renowed giant of bookstores it is today. The Times notes that the 70,000 books in the Fourth Avenue store swelled, at the Broadway site, to half a million by the mid-1960s and 2.5 million by the 1990s, requiring the purchase of a storage warehouse in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. By the time Mr. Bass bought the building for $8.2 million in 1997, the Strand had become the largest used bookstore in the world.

Now that’s an accomplishment! Wow!

The largest used bookstore in the world.

As the Times notes, Mr. Bass was perhaps most famous for creating a literary quiz for prospective Strand employees to take when filling out their applications. “I thought it was a quick way to find if somebody had any knowledge of books,” he told the Times. Applicants had to match 10 authors with 10 titles, and maneuver around one trick question, in an exercise that became a cherished bit of New York lore.

Credit: George Etheredge, New York Times

(Here are more details on the Strand Books quiz)

And in the mid-1990s, I met Mr. Bass himself. As always, he stood behind the counter — sometimes when I saw him he was perched on a high stool, like a king overlooking his bookish palace. He looked like a bartender of books; I almost expected him to slide a bookmark across the table to me, and say in his oddly kind New York accent “What’ll you have today? What’ll take the edge off?”

Credit: Tony Cenicola, New York Times

Yes, Fred was a pusher of books, and he got me to spend hundreds of dollars on books at the Strand over the years. “I got the dust in my blood and I never got it out,” he told McCandlish Phillips, author of City Notebook: A Reporter’s Portrait of a Vanishing New York.

Now you can find Strand Books everywhere around New York City. Besides the main bookstore on Broadway and 12th, you can also find satellite Strands in kiosks outside the entrance to Central Park on Fifth Avenue at Grand Army Plaza and downtown in the South Street Seaport. You can also find Strand Books in a smaller Flatiron district location. Finally, just last year Strand Books opened a summer-season kiosk in Times Square. You can even watch a Video Tour of Strand Books right here.

Strand Books is one of my literary touchstones, and I’m happy to share that bookstore experience with my readers! Enjoy!

Find my books at The Strand

[Read more BOOKSTORE POSTS]

Pinterest – Ned Hayes Bookstore Board

Bookstores: The Strand in New York City was originally published on Ned Hayes

December 31, 2017

A New Year's Day Post

Do not be dismayed by the brokenness of the world.

All things break. And all things can be mended.

Not with time, as they say, but with intention.

So go. Love intentionally, extravagantly, unconditionally.

The broken world waits in darkness for the light that is you.

— L.R. Knost.

A New Year’s Day Post was originally published on Ned Hayes