Martin Edwards's Blog, page 122

July 27, 2018

Forgotten Book - Elizabeth X

Vera Caspary (1899-1987) is remembered today chiefly as the author of Laura, but that book launched her as a crime writer, and she continued to work in the genre for more than 35 years. Her very last novel was Elizabeth X, published in 1978, and it's relatively obscure. But it's well worth a look, especially for anyone who enjoyed Laura.

I don't say that because the stories are similar: they aren't. Laura is a murder mystery; Elizabeth X offers a puzzle of character and identity. An attractive young woman in her early twenties, apparently suffering from amnesia, is found wandering in the road by a married couple called Kate and Allan Royce. The Royces take her home and look after her, but attempts to discover her true identity prove surprisingly unsuccessful.

Where Elizabeth X does resemble Laura is in its structure. Again, Caspary employs the Wilkie Collins method of telling a story from several different first-person viewpoints, starting with that of Chauncey Greenleaf, a man much older than Elizabeth, who nevertheless founds himself strongly drawn to her. But is he destined for misery when the truth about her past emerges?

A plot development later in the story also betrays the Collins influence, though I won't say too much about it for fearing of spoiling the surprise. Collins was, at his best, a master of plotting, and I don't think even Caspary's admirers would make a similar claim for her. She is, though, very good at depicting character, and writing incisive, readable prose. I wanted to find out the truth about Elizabeth, even though I feared I might be slightly disappointed at the end of the book (as, to be honest, I was). But Caspary was an independently minded woman who always does an excellent job of portraying the pressures faced by equally strong-minded women, and Elizabeth X , the final example of her gifts, is definitely worth reading.

I don't say that because the stories are similar: they aren't. Laura is a murder mystery; Elizabeth X offers a puzzle of character and identity. An attractive young woman in her early twenties, apparently suffering from amnesia, is found wandering in the road by a married couple called Kate and Allan Royce. The Royces take her home and look after her, but attempts to discover her true identity prove surprisingly unsuccessful.

Where Elizabeth X does resemble Laura is in its structure. Again, Caspary employs the Wilkie Collins method of telling a story from several different first-person viewpoints, starting with that of Chauncey Greenleaf, a man much older than Elizabeth, who nevertheless founds himself strongly drawn to her. But is he destined for misery when the truth about her past emerges?

A plot development later in the story also betrays the Collins influence, though I won't say too much about it for fearing of spoiling the surprise. Collins was, at his best, a master of plotting, and I don't think even Caspary's admirers would make a similar claim for her. She is, though, very good at depicting character, and writing incisive, readable prose. I wanted to find out the truth about Elizabeth, even though I feared I might be slightly disappointed at the end of the book (as, to be honest, I was). But Caspary was an independently minded woman who always does an excellent job of portraying the pressures faced by equally strong-minded women, and Elizabeth X , the final example of her gifts, is definitely worth reading.

Published on July 27, 2018 12:01

July 26, 2018

The CWA Dagger in the Library

I've written many times on this blog, and elsewhere, about my lifelong love of libraries. I vividly remember being, at the age of ten, allowed to become the smallest member of the adult section of Northwich Library, in order to feed my addiction to Agatha Christie, and then to many other crime writers. And in recent years, in recent weeks even, I've enjoyed doing a range of library events up and down the country, as well as hosting Alibis in the Archives at Gladstone's Library.

I've written many times on this blog, and elsewhere, about my lifelong love of libraries. I vividly remember being, at the age of ten, allowed to become the smallest member of the adult section of Northwich Library, in order to feed my addiction to Agatha Christie, and then to many other crime writers. And in recent years, in recent weeks even, I've enjoyed doing a range of library events up and down the country, as well as hosting Alibis in the Archives at Gladstone's Library.So you can imagine that I'm as pleased as Punch to find my name on the shortlist for the CWA Dagger in the Library, along with such luminaries as Nicci French, Peter May, Simon Kernick, Rebecca Tope, and Keith Miles (aka Edward Marston). This is an award where the nominees are selected by librarians throughout Britain, and I'm duly honoured.

There are some truly wonderful libraries in this country. It's been a privilege for me, over the past few years, to become quite closely associated with the British Library, and that relationship, in particular with Rob Davies and his team in the publications department, has brought me enormous pleasure. The same goes for Louisa Yates and her colleagues at Gladstone's, a very different place, an independent library run as a charity, and rich in history, atmosphere and charm.

And then there are the public libraries which mean so much to the communities of which they form part. I've enjoyed working, for instance, with local and area librarians, and also a Friends Group in Stockton Heath which aims to support the professional staff in a variety of ways.

Hard to believe, but it's almost two years since I wrote about

So there is a great deal of room for optimism about libraries, despite the undoubted financial pressures they face, if all of us who believe in libraries pull together. I look forward very much to trying to play a part, in the coming months and years, to trying to play a small part in helping their almost limitless potential to be realised for the benefit of communities not just in my neck of the woods, but further afield as well.

Published on July 26, 2018 03:27

July 23, 2018

More from Dean Street Press

One of the joys of the revival of interest in Golden Age detective fiction is that quite an avalanche of long-vanished books are now readily available. As in any era, the quality varies. But the range of books that one can now obtain is striking - within the British Library series, for instance, there's a huge difference between the work of, say, Alan Melville, E.C.R. Lorac, Richard Hull, and Raymond Postgate. So readers can discover new writers, and then focus on those they enjoy most.

Various publishing models have been adopted. The British Library focuses on high quality mass market paperbacks, Harper Collins on hardbacks, and others mainly on ebooks and print on demand publications. Dean Street Press fall into the latter camp. They do a really good job, and I'm not just saying that because I've written a few intros for them. Their model makes it possible to reissue a large number of books by the same author. The complete works of Annie Haynes, say, would not be commercially viable if the focus were on mass market paperbacks, because their isn't enough interest in them for the books to be sold in large quantities in paperback format. But thanks to DSP, we can now try out Annie's work in ebook or as a print on demand paperback, and much else besides. One of the DSP authors whom I particularly enjoy is Peter Drax, and I'll be saying more about his books in the future.

At present, DSP are reissuing, in large batches, the Ludovic Travers novels of Christopher Bush. Bush was a writer who wrote so much that sometime quality suffered, but I really enjoyed The Case of the Monday Murders, first published in 1936. The mystery is good, even if I did guess the solution early on, but the satiric touches are even better. This book contains plenty of swipes at Bush's fellow practitioners, and as Curtis Evans says in his intro, the character of crime writer Ferdinand Pole, founder of the Murder League, is surely based on Anthony Berkeley. One chapter title is borrowed from Philip Macdonald: "Murder Gone Mad". There's also a hint of self-mockery in the killer's taunting letters, signed "Justice", which might make one recall the comparable correspondence in Bush's own The Perfect Murder Case.

The funniest moment in the book is when Bush mocks Dorothy L. Sayers and E.R. Punshon in the same breath, parodying Sayers' famous review lauding E.R. Punshon (in the guise of "Petrie Cubbe"), but attributing it to Pole. It does make you wonder how on earth Bush managed to earn election to the Detection Club the year after this book came out, especially since Berkeley was famously thin-skinned. It would be good to think that those who are guyed took it in good part. Or perhaps they just didn't read it! (Though given how many of them were prolific reviewers, that would be surprising). Whatever the truth, the great thing is that readers today have the chance to enjoy this one, and I suspect that it is one of Bush's best.

Various publishing models have been adopted. The British Library focuses on high quality mass market paperbacks, Harper Collins on hardbacks, and others mainly on ebooks and print on demand publications. Dean Street Press fall into the latter camp. They do a really good job, and I'm not just saying that because I've written a few intros for them. Their model makes it possible to reissue a large number of books by the same author. The complete works of Annie Haynes, say, would not be commercially viable if the focus were on mass market paperbacks, because their isn't enough interest in them for the books to be sold in large quantities in paperback format. But thanks to DSP, we can now try out Annie's work in ebook or as a print on demand paperback, and much else besides. One of the DSP authors whom I particularly enjoy is Peter Drax, and I'll be saying more about his books in the future.

At present, DSP are reissuing, in large batches, the Ludovic Travers novels of Christopher Bush. Bush was a writer who wrote so much that sometime quality suffered, but I really enjoyed The Case of the Monday Murders, first published in 1936. The mystery is good, even if I did guess the solution early on, but the satiric touches are even better. This book contains plenty of swipes at Bush's fellow practitioners, and as Curtis Evans says in his intro, the character of crime writer Ferdinand Pole, founder of the Murder League, is surely based on Anthony Berkeley. One chapter title is borrowed from Philip Macdonald: "Murder Gone Mad". There's also a hint of self-mockery in the killer's taunting letters, signed "Justice", which might make one recall the comparable correspondence in Bush's own The Perfect Murder Case.

The funniest moment in the book is when Bush mocks Dorothy L. Sayers and E.R. Punshon in the same breath, parodying Sayers' famous review lauding E.R. Punshon (in the guise of "Petrie Cubbe"), but attributing it to Pole. It does make you wonder how on earth Bush managed to earn election to the Detection Club the year after this book came out, especially since Berkeley was famously thin-skinned. It would be good to think that those who are guyed took it in good part. Or perhaps they just didn't read it! (Though given how many of them were prolific reviewers, that would be surprising). Whatever the truth, the great thing is that readers today have the chance to enjoy this one, and I suspect that it is one of Bush's best.

Published on July 23, 2018 08:32

July 20, 2018

Forgotten Book - The Theft of the Iron Dogs

The Theft of the Iron Dogs is one of the more intriguing titles for a crime novel. The book was written by E.C.R. Lorac, and first published by Collins Crime Club in 1946. It's one of a number of her novels set in the north west of England - Lunesdale. This is an area to which she relocated, and where spent most of her later years. Her love of the area comes through very strongly in the narrative.

The period atmosphere is equally strong. The book opens in September, and the early paragraphs begin with a description of harvesting time in the dairy farming district, where "the war effort had not been concerned with the nervous energy required by resistance to bombs or doodles or rockets; it had been the strain of sustained physical effort."

We are introduced to a farmer called Giles Hoggett, of Wenningby, and one rainy day he decides to go fishing. He takes a look at a summer cottage, only to find that two iron dogs are missing from the fireplace, as well as a complete reel of salmon line, a strong chain and hook, a clothes-line - and a large sack. It doesn't take much of a detective's instinct to figure out that someone has set about sinking something in the river Lune. And the experienced detective fan will have no doubt about what that something might be...

Yes, it's another murder mystery case for Chief Inspector Robert Macdonald of Scotland Yard. Madonald has already developed a love of the Lunesdale landscape and lifestyle, and he sets about untangling a neatly contrived mystery. Lorac's writing is characteristically under-stated, and so is her detective. I imagine that this reflects her own personality. In her quiet way, she was a highly professional writer, and although those who crave melodrama should probably look elsewhere, this book is another example of her capable mystery-making. I'm so glad that, thanks to the British Library's Crime Classic series, she has come back into public view.

The period atmosphere is equally strong. The book opens in September, and the early paragraphs begin with a description of harvesting time in the dairy farming district, where "the war effort had not been concerned with the nervous energy required by resistance to bombs or doodles or rockets; it had been the strain of sustained physical effort."

We are introduced to a farmer called Giles Hoggett, of Wenningby, and one rainy day he decides to go fishing. He takes a look at a summer cottage, only to find that two iron dogs are missing from the fireplace, as well as a complete reel of salmon line, a strong chain and hook, a clothes-line - and a large sack. It doesn't take much of a detective's instinct to figure out that someone has set about sinking something in the river Lune. And the experienced detective fan will have no doubt about what that something might be...

Yes, it's another murder mystery case for Chief Inspector Robert Macdonald of Scotland Yard. Madonald has already developed a love of the Lunesdale landscape and lifestyle, and he sets about untangling a neatly contrived mystery. Lorac's writing is characteristically under-stated, and so is her detective. I imagine that this reflects her own personality. In her quiet way, she was a highly professional writer, and although those who crave melodrama should probably look elsewhere, this book is another example of her capable mystery-making. I'm so glad that, thanks to the British Library's Crime Classic series, she has come back into public view.

Published on July 20, 2018 02:00

July 17, 2018

Married Life - 2007 film review

Married Life is the rather odd (and to my mind unsatisfactory) title given to a 2007 American film version by Ira Sachs of a novel published more than half a century earlier by the British crime novelist and spy John Bingham. The book, Five Roundabouts to Heaven, was his second published novel, and is regarded as one of his best. It appeared in 1953 and had the alternative title The Tender Poisoner, which was the name given to a tv version in 1962 in the Alfred Hitchcock Hour series.

The film is set in 1949, with the action shifted across the Atlantic: many of the scenes were filmed around Vancouver. The strong cast includes Pierce Brosnan, who plays Richard, a likeable chap who has a particular liking for attractive women. His closest friend, Harry (Chris Cooper) is married to Pat (Patricia Carlson) but actually having a torrid affair with Kay (Rachel McAdams). After being introduced to Kay, Richard too becomes smitten, and things inevitably become complicated.

As the alternative title to the book suggests, Harry decides that the ideal solution to his marital dilemma is to murder Pat painlessly. But like so many other wannabe killers before him, he discovers that committing the perfect crime is not as easy as he'd like to believe. And then it turns out that Pat nurses a secret of her own...

This is a quirky film, and is much more entertaining than its commonplace title suggests. Ira Sachs offers plenty of touches of dark humour as well as a sequence of unpredictable developments. The historical setting adds to a sense of playful unreality which is part of its appeal. A major bonus with the DVD is the director's commentary on the three alternative endings that he toyed with. No spoilers from me, but they are well worth watching, as is the film as a whole. Although I haven't read Bingham's book, I'm now keen to do so. He was an interesting and sometimes original writer.

The film is set in 1949, with the action shifted across the Atlantic: many of the scenes were filmed around Vancouver. The strong cast includes Pierce Brosnan, who plays Richard, a likeable chap who has a particular liking for attractive women. His closest friend, Harry (Chris Cooper) is married to Pat (Patricia Carlson) but actually having a torrid affair with Kay (Rachel McAdams). After being introduced to Kay, Richard too becomes smitten, and things inevitably become complicated.

As the alternative title to the book suggests, Harry decides that the ideal solution to his marital dilemma is to murder Pat painlessly. But like so many other wannabe killers before him, he discovers that committing the perfect crime is not as easy as he'd like to believe. And then it turns out that Pat nurses a secret of her own...

This is a quirky film, and is much more entertaining than its commonplace title suggests. Ira Sachs offers plenty of touches of dark humour as well as a sequence of unpredictable developments. The historical setting adds to a sense of playful unreality which is part of its appeal. A major bonus with the DVD is the director's commentary on the three alternative endings that he toyed with. No spoilers from me, but they are well worth watching, as is the film as a whole. Although I haven't read Bingham's book, I'm now keen to do so. He was an interesting and sometimes original writer.

Published on July 17, 2018 05:45

July 13, 2018

Forgotten Book - Laura

Laura, by Vera Caspary, is a famous crime novel that became an even more famous film noir, as well as a stage play, and haunting song. The book was originally published in 1942, and it made an instant impact. Caspary was a talented mainstream writer, whose memoirs, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, make fascinating reading. She makes it clear that she wasn't really a mystery fan, but it's noteworthy that her favourite crime writer was Cornell Woolrich, her favourite crime novel Francis Iles' Before the Fact. Suspense appealed to her, in other words, and Laura is a novel of suspense as much as it is a detective story.

When, many years ago, I first saw the film, and read the book, I enjoyed them without fully appreciating them. That was because I paid too much attention to the plot, and although the story has one excellent plot twist, Caspary's strength didn't lie in plotting. On rereading the book after having done some research into Caspary's life, I got more out of it than I did the first time around.

Mark McPherson is called in to investigate the murder of Laura Hunt, a very attractive woman who works in advertising. She is engaged to be married, and her fiance becomes a suspect. McPherson becomes intrigued by Waldo Lydecker, a rather effete older man who was close to Laura, and who is one of the narrators.

In telling her story, Caspary borrowed the narrative device favoured by Wilkie Collins - using different points of view, so as to conceal as well as reveal. It's a device which, when employed with skill (and Caspary was highly skilled), I find engrossing. I've never written a "casebook" novel, but it's something I'd certainly consider at some future date, because the form has a great deal of potential for the crime writer. It's fair to say that Caspary never surpassed Laura, but her other books are also intriguing and well-written, and I'll talk about one or two of them in the future.

When, many years ago, I first saw the film, and read the book, I enjoyed them without fully appreciating them. That was because I paid too much attention to the plot, and although the story has one excellent plot twist, Caspary's strength didn't lie in plotting. On rereading the book after having done some research into Caspary's life, I got more out of it than I did the first time around.

Mark McPherson is called in to investigate the murder of Laura Hunt, a very attractive woman who works in advertising. She is engaged to be married, and her fiance becomes a suspect. McPherson becomes intrigued by Waldo Lydecker, a rather effete older man who was close to Laura, and who is one of the narrators.

In telling her story, Caspary borrowed the narrative device favoured by Wilkie Collins - using different points of view, so as to conceal as well as reveal. It's a device which, when employed with skill (and Caspary was highly skilled), I find engrossing. I've never written a "casebook" novel, but it's something I'd certainly consider at some future date, because the form has a great deal of potential for the crime writer. It's fair to say that Caspary never surpassed Laura, but her other books are also intriguing and well-written, and I'll talk about one or two of them in the future.

Published on July 13, 2018 12:04

July 11, 2018

Jessica Mann R.I.P.

[image error]I'm truly sorry to report the death, on Wednesday, of Jessica Mann, a crime writer and reviewer of distinction. It's only a month ago that she played a full part in the Alibis in the Archives weekend, talking with her customary fluency and passion about female crime writing, and then joining a panel of authors for a wide-ranging discussion about the genre. A fortnight ago, she was - as so often - a convivial guest at a Detection Club dinner. And only last week I received a parcel of books from her. It was, therefore, with great shock and much sadness that I heard the news from her daughter Lavinia yesterday.

Jessica lived a full life of high accomplishment, and I’ll remember her with huge affection not just as a talented author but as someone who was always ready, willing, and able to give younger colleagues, myself included, a great deal of help and encouragement. I first met her in the late 1980s, some years after I first read her books, but it's really been in the past ten years that she and I became friends. She followed this blog and emailed me regularly to urge me to keep busy, travelling and writing. We'd even talked recently about collaborating on a book together. She was a great believer in making the most of life, a philosophy that stood her in good stead.

Jessica Mann was educated at St Paul’s Girls’ School and Newnham College, Cambridge, where she studied archaeology, and Leicester University, where she took a degree in law; she became a barrister, but did not practise, although she later served as an employment tribunal member. Over the years, she served as a planning inspector as well as serving on numerous committees – including the CWA committee – and as Secretary of the Detection Club. A week after she completed her finals at Cambridge, she married the distinguished archaeologist and historian Charles Thomas; they had two sons and two daughters. Jessica and Charles lived in Cornwall for many years, but after his death two years ago she came back to London, the city of her birth.

Jessica’s first crime novel, A Charitable End, appeared in 1971; her penultimate book, Dead Woman Walking took her career full circle, as it reintroduced one of the characters from her debut, as well as the psychiatrist Dr Fidelis Berlin, who appeared in a handful of earlier novels, perhaps most memorably the superb A Private Enquiry, which was shortlisted for a CWA Gold Dagger. Her final novel, The Stroke of Death, saw the reappearance of perhaps her most popular character, the archaeologist Tamara Hoyland, after an absence, regretted by many readers, of a quarter of a century.

Jessica’s non-fiction included Deadlier than the Male, an excellent study of female crime writing, and she was in much demand as a journalist and broadcaster from the time she first appeared on Radio 4’s Any Questions in the 1970s; she also featured on Question Time, Start the Week, Stop the Week, and the Round Britain Quiz . For many years, she reviewed crime for the Literary Review. For about fifteen years, she’d coped with Parkinson’s, which must have been very difficult, but her spirit was indomitable. Her life advice to me, regularly repeated and much appreciated, was very simple: “Do it now!” Jessica was, you see, a wise woman as well as a good friend and a fine writer. She will be much missed.

Published on July 11, 2018 15:31

Double Confession - 1950 film review

Double Confession is a British post-war film which is sometimes described as a film noir, despite the fact that the action mostly takes place on a bright summer day at the seaside. In fact, the basis for the screenplay was a novel called All on a Summer's Day, written by John Garden (a title and author name which seem distinctly non-noir). The Garden name was actually a pseudonym for Harry Liff Verne Fletcher (1902-74), whose day job was as a schoolteacher in Llandridnod Wells.

The story begins with Jim Medway (Derek Farr) turning up at a remote coastal house at four in the morning, apparently to visit a woman. He passes a mysterious man who is leaving the house, whom Doctor Who fans will instantly recognise as the first Doctor, William Hartnell. A scream is heard...

The following day, it turns out that the woman is dead and so is a mysterious man who has plunged from the dangerous cliff path. Medway calls on Charlie Durham (Hartnell), a local entrepreneur who has been having an affair with the dead woman - who proves to be Medway's estranged wife. The plot complications thicken from there.

The quality of the cast lifts this film out of the ordinary. We have Naunton Wayne as an affable police inspector, and Peter Lorre as Durham's psychopathic sidekick. Medway manages to spend his day blackmailing Durham while getting friendly with an attractive woman (Joan Hopkins) who has personal problems of her own. The seaside locations help to make the implausibilities of the plot bearable, and Ken Annakin directs intelligently, even though the story meanders around quite a lot. It's not exactly Body Heat, far less Double Indemnity, but I enjoyed it.

The story begins with Jim Medway (Derek Farr) turning up at a remote coastal house at four in the morning, apparently to visit a woman. He passes a mysterious man who is leaving the house, whom Doctor Who fans will instantly recognise as the first Doctor, William Hartnell. A scream is heard...

The following day, it turns out that the woman is dead and so is a mysterious man who has plunged from the dangerous cliff path. Medway calls on Charlie Durham (Hartnell), a local entrepreneur who has been having an affair with the dead woman - who proves to be Medway's estranged wife. The plot complications thicken from there.

The quality of the cast lifts this film out of the ordinary. We have Naunton Wayne as an affable police inspector, and Peter Lorre as Durham's psychopathic sidekick. Medway manages to spend his day blackmailing Durham while getting friendly with an attractive woman (Joan Hopkins) who has personal problems of her own. The seaside locations help to make the implausibilities of the plot bearable, and Ken Annakin directs intelligently, even though the story meanders around quite a lot. It's not exactly Body Heat, far less Double Indemnity, but I enjoyed it.

Published on July 11, 2018 05:14

July 9, 2018

Football Fever and other celebrations

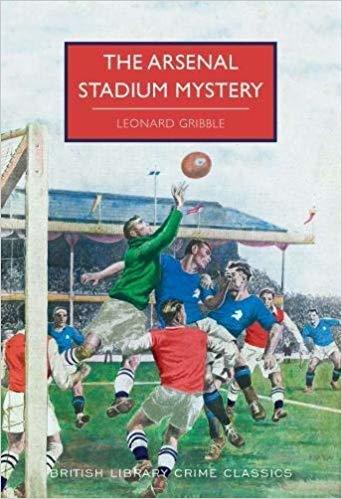

As England celebrates an improbable run of success in the World Cup, the British Library publishes tomorrow a novel that is surely the best of all classic mysteries with a football setting, Leonard Gribble's The Arsenal Stadium Mystery. Great timing! I'm delighted to see this book back in print, and even though I'm not an Arsenal fan, it's an enjoyable fair puzzle mystery that was turned into an equally entertaining film.

England's unexpectedly convincing win against Sweden came as a happy extra birthday present on Saturday. I just got back home in time for the match, following a quick trip to London to watch Burt Bacharach in concert at the Royal Festival Hall. In keeping with the mood, the great man wore an England football shirt throughout. It was a wonderful evening, quite well reviewed here, and we were treated to three new songs, including a very good one that has never been publicly performed before. The standing ovation was utterly deserved, after more than two hours of non-stop melody. Few 90 year olds could compete with this stunning performance, that's for sure.

After the match on Saturday we headed to North Wales for an enjoyable dinner at a nice hotel before on Sunday I achieved a long held ambition. When I was a small boy, we often went on holiday to North Wales, and I became fascinated by an island off Anglesey called Puffin Island. For many years, rats took over from the sea birds, but now they are gone and wildlife boat trips to Puffin Island from the historic town of Beaumaris are available.

I've wanted to take such a trip for a while, and the perfect weather yesterday made it a memorable occasion. It was fascinating to see at close quarters the island which intrigued me so much when I was small. There were seals, as well as innumerable birds. And the puffins are back - it was fun to see them flying around. All in all, a marvellous weekend.

Published on July 09, 2018 07:27

July 5, 2018

Forgotten Book - Game for Three Losers

Edgar Lustgarten was once a familiar face on British TV screens. A barrister from Manchester, he became a successful broadcaster, specialising in programmes about crime. The Scotland Yard TV series that he fronted (and which was very good) has recently been resurrected on the Talking Pictures channel, and this has reignited my interest in a writer who wrote occasional novels as well as numerous true crime books. His first novel, A Case to Answer, was especially well-regarded, not least by Julian Symons.

Game for Three Losers was first published in 1952; later, it was adapted for TV as part of the Edgar Wallace Mysteries series which has again resurfaced thanks to Talking Pictures. The novel is written in Lustgarten's rather distinctive style, with rather more "tell" than "show"; today, this isn't a fashionable method, but he handles it pretty well.

Robert Hilary is a rising star in the political world, a Conservative MP in his late forties. When his trusty secretary leaves work to have a baby, her replacement is a stunningly beautiful young woman and Hilary finds her irresistible. He soon finds himself in a compromising position, and open to blackmail by the woman's rascally lover, who poses as her outraged brother.

I rather expected Hilary to decide that the only solution to his dilemma was murder, but Lustgarten's main focus is on charting the consequences of crime. This is a book roughly in the Francis Iles tradition that focuses on the way the legal system operates - not very justly, in some cases. The story is downbeat in mood, but Lustgarten's crisp writing kept me interested from start to finish.

Game for Three Losers was first published in 1952; later, it was adapted for TV as part of the Edgar Wallace Mysteries series which has again resurfaced thanks to Talking Pictures. The novel is written in Lustgarten's rather distinctive style, with rather more "tell" than "show"; today, this isn't a fashionable method, but he handles it pretty well.

Robert Hilary is a rising star in the political world, a Conservative MP in his late forties. When his trusty secretary leaves work to have a baby, her replacement is a stunningly beautiful young woman and Hilary finds her irresistible. He soon finds himself in a compromising position, and open to blackmail by the woman's rascally lover, who poses as her outraged brother.

I rather expected Hilary to decide that the only solution to his dilemma was murder, but Lustgarten's main focus is on charting the consequences of crime. This is a book roughly in the Francis Iles tradition that focuses on the way the legal system operates - not very justly, in some cases. The story is downbeat in mood, but Lustgarten's crisp writing kept me interested from start to finish.

Published on July 05, 2018 08:25