Martin Edwards's Blog, page 119

October 3, 2018

Rider on the Rain - 1970 film review

Rider on the Rain is a French crime film which is certainly anything but run of the mill. It was released in 1970 and stars the beautiful Marlene Joubert and also Charles Bronson (in the days before he became famous through the Death Wish franchise). The role of Joubert's mother is played by Jill Ireland, who was Bronson's wife, and far too young for the part.

Now I have to admit that my instinct is to avoid Bronson films, but I was drawn to this one by the fact that it was written by Sebastien Japrisot, one of the finest French crime writers, and the man responsible for books such as Trap for Cinderella and One Deadly Summer. Highly talented, he even wrote the lyric for the film's title song - the music was by Francis Lai, a leading film composer best known for A Man and a Woman and Love Story. Rene Clement directs.

Joubert plays Mel (or "Melancholie"), a young woman who is pushed around by her mother and her husband. One day, a stranger turns up in town. He spots Mel, follows her, and rapes her. She manages to shoot him, and having done so, she throws his body into the sea. Then a mysterious smiling American called Dobbs (Bronson) arrives on the scene, and makes it clear that he knows what she's done.

It isn't clear what Dobbs' game is, and the film sags at this point after a compelling start. I found Dobbs' treatment of Mel troubling, although one or two plot twists put a different complexion on things. This film was a big hit in Europe, though it didn't do well in the UK, and it may be fair to say that time hasn't treated it well. Yet it does have some appealing ingredients, including explicit nods to Alice in Wonderland and Alfred Hitchcock. A curate's egg of a film, really, but the combination of Japrisot and Joubert meant that I felt it was worth watching.

Now I have to admit that my instinct is to avoid Bronson films, but I was drawn to this one by the fact that it was written by Sebastien Japrisot, one of the finest French crime writers, and the man responsible for books such as Trap for Cinderella and One Deadly Summer. Highly talented, he even wrote the lyric for the film's title song - the music was by Francis Lai, a leading film composer best known for A Man and a Woman and Love Story. Rene Clement directs.

Joubert plays Mel (or "Melancholie"), a young woman who is pushed around by her mother and her husband. One day, a stranger turns up in town. He spots Mel, follows her, and rapes her. She manages to shoot him, and having done so, she throws his body into the sea. Then a mysterious smiling American called Dobbs (Bronson) arrives on the scene, and makes it clear that he knows what she's done.

It isn't clear what Dobbs' game is, and the film sags at this point after a compelling start. I found Dobbs' treatment of Mel troubling, although one or two plot twists put a different complexion on things. This film was a big hit in Europe, though it didn't do well in the UK, and it may be fair to say that time hasn't treated it well. Yet it does have some appealing ingredients, including explicit nods to Alice in Wonderland and Alfred Hitchcock. A curate's egg of a film, really, but the combination of Japrisot and Joubert meant that I felt it was worth watching.

Published on October 03, 2018 15:05

Pushkin Vertigo

Recently, I was contacted by the publishers Pushkin Vertigo, who asked if I would be willing to supply a quote in relation to their reissue of Margaret Millar's novel of suspense Vanish in an Instant. I was happy to do so for two reasons. First, I'm a big Millar fan and I'm always delighted whenever her books return to the shelves. Second, I've been impressed by the Pushkin Vertigo imprint, and some of you may recall that I've previously reviewed a couple of their books, by Frederic Dard and Augusto de Angelis, on this blog.

I've taken a further look at their list, and found it really interesting. One of the titles is Vertigo by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. I hope that more books by that brilliant duo resurface - including, dare I say, some of those which have never been translated into English in the past. I would love to read more of their work; alas, my schoolboy French is not up to it!

I note also that PV have reissued several books by Friedrich Durrenmatt. I first came across this fascinating Swiss writer when I was studying German at A Level. One of the set texts was Durrenmatt's sardonic play The Visit. I loved it, and was prompted to read much of his other work, including his detective stories, some of which are now, happily, available again. The Judge and His Hangman is a good place to start.

I recently read Maria Angelica Bosco's Death Going Down and Leo Perutz's Saint Peter's Snow, both of which I enjoyed. Of the two, Perutz's is perhaps the more striking, because the storyline is quite remarkable. No wonder the Nazis hated it. But both novels are well worth reading,and when time permits I'll talk about them in more detail. Bosco, incidentally, was someone to whom Jorge Luis Borges gave encouragement, and if, like me, you are a Borges fan, that in itself is an endorsement.

Published on October 03, 2018 02:49

October 1, 2018

Jersey's Festival of Words

I'm just back home after taking part in Jersey's Festival of Words, a very well-organised literary festival on one of my favourite islands. I was involved with a couple of events - first, a crime writing workshop, and second, a talk. Both took place at Jersey Library in St Helier, where I've spoken a couple of times previously. It's an excellent library, well-designed and with admirable facilities.

Flight times from Manchester meant that I had some free time which enabled me to do some sight-seeing, and take advantage of fantastic sunny weather. I caught a bus to Gorey, a port on the south east tip of the island that I've visited before, and which is quite lovely. Wandering around the harbour, and then Mont Orgeuil, a very well-preserved castle, was a delight. The exhibits inside the castle included the fascinating "Wounded Man" and also "The Dance of Death" installation, and these vivid images set me thinking about possible story ideas...

The crime writing workshop was fun, with a good group of participants who got into their stride quickly with a variety of writing exercises. I've conducted a number of workshops over the years, in an assortment of venues (including a prison and a young offenders' institute, as well as libraries) and find them very interesting. It's something I might well do more often in the future.

The subject of my talk was "The Making of a Crime Novel". I give a range of talks - the most frequently requested over many years being "My Life of Crime", but this was a new one, and the focus was on how I came to write Gallows Court, and the process of moving from the first idea to publication and marketing. I don't speak from notes (usually) so each talk is a bit different, even if the subject is the same. And "The Making of a Crime Novel" will return in the near future...In the meantime, my thanks go to Judith Baker and her colleagues for inviting me to take part in a splendid festival.

Flight times from Manchester meant that I had some free time which enabled me to do some sight-seeing, and take advantage of fantastic sunny weather. I caught a bus to Gorey, a port on the south east tip of the island that I've visited before, and which is quite lovely. Wandering around the harbour, and then Mont Orgeuil, a very well-preserved castle, was a delight. The exhibits inside the castle included the fascinating "Wounded Man" and also "The Dance of Death" installation, and these vivid images set me thinking about possible story ideas...

The crime writing workshop was fun, with a good group of participants who got into their stride quickly with a variety of writing exercises. I've conducted a number of workshops over the years, in an assortment of venues (including a prison and a young offenders' institute, as well as libraries) and find them very interesting. It's something I might well do more often in the future.

The subject of my talk was "The Making of a Crime Novel". I give a range of talks - the most frequently requested over many years being "My Life of Crime", but this was a new one, and the focus was on how I came to write Gallows Court, and the process of moving from the first idea to publication and marketing. I don't speak from notes (usually) so each talk is a bit different, even if the subject is the same. And "The Making of a Crime Novel" will return in the near future...In the meantime, my thanks go to Judith Baker and her colleagues for inviting me to take part in a splendid festival.

Published on October 01, 2018 09:30

September 28, 2018

Forgotten Book - Edith's Diary

It's safe to say that Edith's Diary is one of Patricia Highsmith's less renowned books. It was first published in 1977, at a time when her powers as a crime novelist were, perhaps waning. Indeed, her usual American publishers rejected it, which must have come as a huge blow. But there are some critics who rank it with her finest work, and having come to it belatedly, I'm tempted to agree. It far exceeded my expectations, in fact.

I suppose the first question is this: is Edith's Diary a crime novel at all? One of the characters commits a number of crimes, almost certainly including a murder, but these are not the main focus of the story. And my answer to the question is: I think it can be described as a crime novel, but it really doesn't matter. I don't think it's terribly helpful to get hung up on definitions of what does and does not constitute a crime story. Some stories, naturally enough, occupy the borderlands between crime and mainstream fiction, and worrying about how to pigeon-hole them is a distraction .What counts is the quality of the story.

For me, Edith's Diary was a revelation in more ways than one. I knew that the title character, Edith Howland, kept a diary that becomes increasingly a means of living out a fantasy life divorced from reality, and this is an idea which strikes me as tremendously powerful and appealing. But even the diary is not the main focus of the story. Rather, the key is Highsmith's lucid but rather terrible depiction of a disintegrating life.

Edith's descent is charted over a long time span, with many political references which give the story a dated feel. She's a left-wing progressive, a minor writer and journalist who is married to an apparently (but perhaps not actually) decent man, and they have one child, the lazy, slobbish, hard-drinking Cliffie. The family is completed by her husband's equally idle uncle, whose continuing presence in the household Edith tolerates for reasons that aren't easy to understand. We sympathise with her, but Highsmith is relentless in probing her many weaknesses. The result is a novel that, for all its touches of wry humour, is bleak but memorable.

I suppose the first question is this: is Edith's Diary a crime novel at all? One of the characters commits a number of crimes, almost certainly including a murder, but these are not the main focus of the story. And my answer to the question is: I think it can be described as a crime novel, but it really doesn't matter. I don't think it's terribly helpful to get hung up on definitions of what does and does not constitute a crime story. Some stories, naturally enough, occupy the borderlands between crime and mainstream fiction, and worrying about how to pigeon-hole them is a distraction .What counts is the quality of the story.

For me, Edith's Diary was a revelation in more ways than one. I knew that the title character, Edith Howland, kept a diary that becomes increasingly a means of living out a fantasy life divorced from reality, and this is an idea which strikes me as tremendously powerful and appealing. But even the diary is not the main focus of the story. Rather, the key is Highsmith's lucid but rather terrible depiction of a disintegrating life.

Edith's descent is charted over a long time span, with many political references which give the story a dated feel. She's a left-wing progressive, a minor writer and journalist who is married to an apparently (but perhaps not actually) decent man, and they have one child, the lazy, slobbish, hard-drinking Cliffie. The family is completed by her husband's equally idle uncle, whose continuing presence in the household Edith tolerates for reasons that aren't easy to understand. We sympathise with her, but Highsmith is relentless in probing her many weaknesses. The result is a novel that, for all its touches of wry humour, is bleak but memorable.

Published on September 28, 2018 02:00

September 26, 2018

Beast - 2017 film review

Beast is a drama about crime rather than a conventional crime film. It's set on the lovely island of Jersey, but this isn't a tourist trap portrayal of the place, but rather one which brings out its lonely, bleaker qualities. Written and directed by Michael Pearce (no relation, as far as I know, to the author of the Mamur Zapt crime series), it's interesting and unsettling because it veers away from what appeared to be the predictable development of the plot.

Jessie Buckley, who was very good in the TV version of The Woman in White, plays Moll Huntford. She's 27, and lives with her family; her mother (Geraldine James, excellent as always) is highly controlling and at times unkind to her. There appears to be some mystery about Moll's past which may explain why she's less favoured than her sister. Moll works as a guide on coach tours, though this job plays no real part in the storyline.

After running away from her own birthday party, Moll meets Pascal (Johnny Flynn), a good-looking poacher who soon manages to unlock her wild side. But when a series of murders disrupt the island community, Pascal becomes a suspect. The main weakness in the film is that there is never any clear or convincing indication as to why Pascal is a suspect - just because he doesn't fit in to the community? Moll gives him a fake alibi in relation to one crime that could easily be checked, but doesn't seem to be. I felt this part of the story was clumsily handled.

Never mind. The story develops in an increasingly dark way as the police close in on the killer. Matters are complicated by the fact that one of the cops fancies Moll and wants her for himself. Despite some unevenness in the script, I found this a gripping film, splendidly atmospheric. Well worth watching.

Jessie Buckley, who was very good in the TV version of The Woman in White, plays Moll Huntford. She's 27, and lives with her family; her mother (Geraldine James, excellent as always) is highly controlling and at times unkind to her. There appears to be some mystery about Moll's past which may explain why she's less favoured than her sister. Moll works as a guide on coach tours, though this job plays no real part in the storyline.

After running away from her own birthday party, Moll meets Pascal (Johnny Flynn), a good-looking poacher who soon manages to unlock her wild side. But when a series of murders disrupt the island community, Pascal becomes a suspect. The main weakness in the film is that there is never any clear or convincing indication as to why Pascal is a suspect - just because he doesn't fit in to the community? Moll gives him a fake alibi in relation to one crime that could easily be checked, but doesn't seem to be. I felt this part of the story was clumsily handled.

Never mind. The story develops in an increasingly dark way as the police close in on the killer. Matters are complicated by the fact that one of the cops fancies Moll and wants her for himself. Despite some unevenness in the script, I found this a gripping film, splendidly atmospheric. Well worth watching.

Published on September 26, 2018 03:09

September 25, 2018

The Big Somewhere by Steven Powell

The growth of academic interest in crime fiction over the past few decades has been quite stunning. When Julian Symons published the first edition of Bloody Murder in 1972, very few scholarly studies of the genre were available. Since then, hundreds have been published. Crime has become a "respectable" subject for academic study. Yet it's striking that not one of these academic books has had a fraction of the impact of Symons' book.

Why is this? Certainly, there are many insightful and scholarly studies of the genre which have taught me a good deal. But there is also a sense that some (too many, to be frank) of these books represent the work of a small group of people talking to themselves, rather than to the wider community of crime fans or crime writers. It's not uncommon, for instance, to find endless pages devoted to turgid footnotes which seem designed mainly to prove that the authors have done their homework and which, I suspect, hardly anyone finds useful. In my opinion, that's a real pity.

Not long after The Golden Age of Murder was published, I was invited to take part in a symposium focusing on the work of James Ellroy at the University of Liverpool. The event was organised by a lecturer at the university, Steven Powell, who has specialised in writing about American crime fiction, and in particular about Ellroy. I really enjoyed taking part (and meeting, amongst others, Woody Haut, whose books about hardboiled crime fiction, and its links with Hollywood have long appealed to me); I also found that I enjoyed reading Steven's own writings, which seemed punchier and more accessible than much other academic work about the genre.

Now Steven has a new book out; The Big Somewhere is published by Bloomsbury, and comprises a range of essays by various authors (including Woody Haut) on the subject of Ellroy's fiction. My interest in Ellroy dates back to the late 80s, and although I've not read much of his work in the last fifteen years, I attended a talk he gave some time ago (making sure that he inscribed some of his books to me!) and found him as remarkable in person as he is in print. There is nobody quite like "the Demon Dog".

His unique qualities as a crime writer are well captured, and cogently analysed, in The Big Somewhere. In addition to a general introduction, Steven Powell contributes the first essay in the book, and co-authors the tenth and concluding essay, which deals with Ellroy's influence on the British writer David Peace. It's always the case with a book of this kind (as it is with an anthology of short stories) that one will not rate every contribution equally highly, but I found something of interest in all of them. Diana Powell's study of Ellroy's influence on Megan Abbott (in her earlier novels, at least) is particularly thought-provoking.

Because I'm a fan of books about the genre, I'm keen to see a narrowing of the gap between academic studies and more popular accounts of crime fiction, such as Bloody Murder. Novelists like me who are interested in the genre's range and possibilities can learn a great deal from the academics, and I think it's fair to say that there are plenty of academics who could profitably study the art of writing readably. Books like The Big Somewhere, which contain a good deal of valuable information without becoming unduly bogged down by scholar-speak, point the way forward. I enjoyed reading this book, and not only because of the absence of tedious footnotes in tiny print! I think that anyone who is a serious Ellroy fan will find The Big Somewhere worth reading.

Why is this? Certainly, there are many insightful and scholarly studies of the genre which have taught me a good deal. But there is also a sense that some (too many, to be frank) of these books represent the work of a small group of people talking to themselves, rather than to the wider community of crime fans or crime writers. It's not uncommon, for instance, to find endless pages devoted to turgid footnotes which seem designed mainly to prove that the authors have done their homework and which, I suspect, hardly anyone finds useful. In my opinion, that's a real pity.

Not long after The Golden Age of Murder was published, I was invited to take part in a symposium focusing on the work of James Ellroy at the University of Liverpool. The event was organised by a lecturer at the university, Steven Powell, who has specialised in writing about American crime fiction, and in particular about Ellroy. I really enjoyed taking part (and meeting, amongst others, Woody Haut, whose books about hardboiled crime fiction, and its links with Hollywood have long appealed to me); I also found that I enjoyed reading Steven's own writings, which seemed punchier and more accessible than much other academic work about the genre.

Now Steven has a new book out; The Big Somewhere is published by Bloomsbury, and comprises a range of essays by various authors (including Woody Haut) on the subject of Ellroy's fiction. My interest in Ellroy dates back to the late 80s, and although I've not read much of his work in the last fifteen years, I attended a talk he gave some time ago (making sure that he inscribed some of his books to me!) and found him as remarkable in person as he is in print. There is nobody quite like "the Demon Dog".

His unique qualities as a crime writer are well captured, and cogently analysed, in The Big Somewhere. In addition to a general introduction, Steven Powell contributes the first essay in the book, and co-authors the tenth and concluding essay, which deals with Ellroy's influence on the British writer David Peace. It's always the case with a book of this kind (as it is with an anthology of short stories) that one will not rate every contribution equally highly, but I found something of interest in all of them. Diana Powell's study of Ellroy's influence on Megan Abbott (in her earlier novels, at least) is particularly thought-provoking.

Because I'm a fan of books about the genre, I'm keen to see a narrowing of the gap between academic studies and more popular accounts of crime fiction, such as Bloody Murder. Novelists like me who are interested in the genre's range and possibilities can learn a great deal from the academics, and I think it's fair to say that there are plenty of academics who could profitably study the art of writing readably. Books like The Big Somewhere, which contain a good deal of valuable information without becoming unduly bogged down by scholar-speak, point the way forward. I enjoyed reading this book, and not only because of the absence of tedious footnotes in tiny print! I think that anyone who is a serious Ellroy fan will find The Big Somewhere worth reading.

Published on September 25, 2018 14:48

September 24, 2018

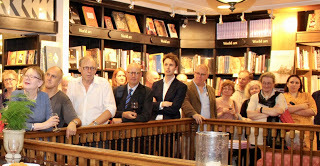

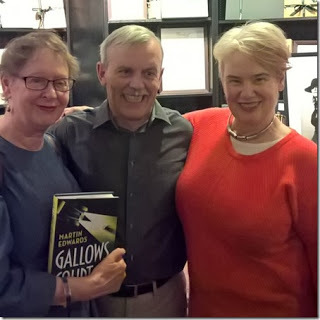

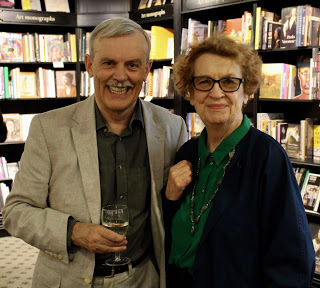

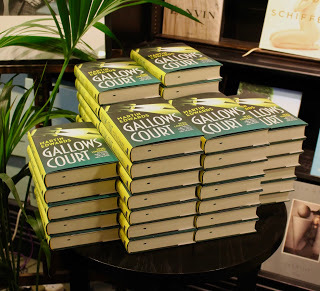

Launching Gallows Court

I've never had a launch party for one of my novels in London before, but Head of Zeus did me proud last week with the launch of Gallows Court at Hatchards in Piccadilly, a lovely venue and London's most historic bookshop. I arrived at the venue on a high, given that the book had just received fantastic reviews in The Times and The Sunday Express, as well as on various blogs and other sites. So I was very much in the mood to celebrate.

And what a fun occasion it was. Many years ago, when I was being published by Transworld, a senior editor gloomily warned me not to get over-excited about launches, and I've never forgotten that. But things are different with Head of Zeus. It really was a wonderful evening and the turnout was terrific.

Barry Forshaw was signed up to conduct a short QandA with me, and he handled it with his customary aplomb. Gary Stratmann kindly took photographs and I'm grateful to him and also to Sven Pehla for the photos accompanying this post.

Among many others, I was delighted to see my former agent, Mandy Little, her successor James Wills, my editor at Harper Collins, David Brawn, and my former editor (from my days with Hodder) Kate Lyall Grant, along with fellow crime writer and music agent Paul Charles. I'd lunched with Paul and chatted to Kate a week earlier in Florida: small world, huh? Simon Brett, my predecessor as President of the Detection Club, came along, and so did Sheila Mitchell, widow of Simon's predecessor, Harry Keating, Bodies from the Library organisers, and the family of CWA founder Roy Vickers. It was good to see Gordon Griffin, a terrific actor who has recorded many of my audio books. There were also numerous CWA chums including Mike Stotter, Linda Stratmann, Ruth Dudley Edwards, Ali Karim, Ayo Onatade, and Chrissie Poulson, other fellow writers such as Robert Thorogood, the lovely guy who created and writes Death in Paradise, blogging friends like Moira Redmond, and Golden Age enthusiasts like Sven, Seona Ford from the Dorothy L. Sayers Society, and Geoff Bradley, editor of CADS.

Among a group of guests whom I first got to know at university were two guys I'd last seen when I took my degree - a very long time ago indeed. Wonderful to see them again after all this time. I very much appreciate the efforts of Nic Cheetham, Suzanne Sangster and the rest of the Head of Zeus team to make the event a success. And I was truly grateful that so many nice people took the time to help me celebrate a book that means a good deal to me.

Published on September 24, 2018 09:41

September 21, 2018

Forgotten Book - Murderer's Fen

Andrew Garve enjoyed a long and fairly illustrious career as a crime writer, as well as pursuing a successful career as a journalist under his real name, Paul Winterton. I tend to bracket him with Michael Gilbert, who was just a few years younger, because they were both versatile and highly professional writers whose books are invariably smooth reads. If I lean in favour of Gilbert, it's partly because he uses his legal expertise so brilliantly, and I think he was a slightly more gifted writer. But Garve was good, make no mistake about that.

Today I'm focusing on Murderer's Fen, a novel he wrote in the mid-Sixties and which is nowadays available again, thanks to Bello. If I didn't know Garve had written it, I could guess, because it features life on a boat as one of the elements in the story - Garve plainly loved sailing, almost to the point of obsession. It crops up time and again in his novels, and it's to his credit that although I'm not interested in the technical details of boats and sailing, this quirk doesn't irritate me at all.

Murderer's Fen is interesting as an example of the "inverted mystery". We're introduced to Alan Hunter, handsome and persuasive, while he's on holiday, eyeing up the girls. Before long we realise that he's actually a nasty piece of work, a sexual predator with little or no empathy for the girls he seduces. And soon, he has cause to contemplate murder.

Garve offers us a variation on the classic form of inverted mystery, by shifting the viewpoint from time to time between the culprit and the investigating detectives (a nicely contrasted pair). This device works well as a means of building suspense. An idea for a twist occurred to me which never materialised - perhaps I'll use it myself one day! Garve wasn't super-ingenious, really, but he knew how to tell a good story. And Murderer's Fen is a good read with an excellent setting in -naturally - Fen country..

Today I'm focusing on Murderer's Fen, a novel he wrote in the mid-Sixties and which is nowadays available again, thanks to Bello. If I didn't know Garve had written it, I could guess, because it features life on a boat as one of the elements in the story - Garve plainly loved sailing, almost to the point of obsession. It crops up time and again in his novels, and it's to his credit that although I'm not interested in the technical details of boats and sailing, this quirk doesn't irritate me at all.

Murderer's Fen is interesting as an example of the "inverted mystery". We're introduced to Alan Hunter, handsome and persuasive, while he's on holiday, eyeing up the girls. Before long we realise that he's actually a nasty piece of work, a sexual predator with little or no empathy for the girls he seduces. And soon, he has cause to contemplate murder.

Garve offers us a variation on the classic form of inverted mystery, by shifting the viewpoint from time to time between the culprit and the investigating detectives (a nicely contrasted pair). This device works well as a means of building suspense. An idea for a twist occurred to me which never materialised - perhaps I'll use it myself one day! Garve wasn't super-ingenious, really, but he knew how to tell a good story. And Murderer's Fen is a good read with an excellent setting in -naturally - Fen country..

Published on September 21, 2018 09:00

September 16, 2018

Eyewitness - 1956 film

I didn't have particularly high hopes when I settled down to watch Eyewitness, a 1956 British B movie, on Talking Pictures. But I liked the music that accompanied the titles, and soon discovered that it was written by Bruce Montgomery (better known as Edmund Crispin). A plus. And then I saw the script was written by Janet Green, who was also responsible for those excellent screenplays, Sapphire (which won an Edgar) and Victim. A definite plus. What's more, the cast was excellent, packed with good actors of the period.

The film proved to be excellent, taut and highly entertaining. It must rank as one of the finest achievements of the director, the under-estimated Muriel Box. The suspense is maintained throughout, but there are also plenty of nice touches, including quite a bit of social comment and comedy, that make the watching experience very enjoyable. I'm surprised it isn't better known.

At the start, Jay Church (Michael Craig) buys a television on hire purchase, infuriating his wife Lucy (Muriel Pavlow, actually a former girlfriend of Edmund Crispin). The couple argue, and she storms out of the house, and goes to watch a film to simmer down. Becoming bored, she leaves her seat in the cinema, and chances upon an armed robbery. Two crooks (Donald Sinden and Nigel Stock) are robbing the manager's safe, but the manager turns up unexpectedly. While Barney (Stock, a future TV Dr Watson) chases Lucy, Wade (Sinden) shoots the manager dead. Lucy runs out into the street, and is knocked down by a bus.

Wade realises that he needs to silence Lucy, and discovers the hospital she's been taken to. Together with the hapless Barney, he follows her there. But things get complicated, as the ward is busy, with an eagle-eyed sister, an extremely attractive nurse (Belinda Lee, who five years later was tragically killed in a car crash at the age of 26), a chatty old patient, and an inquisitive young girl. Tension builds as Wade's murderous designs are thwarted more than once.

The wonderful cast, which also includes Richard Wattis, Nicholas Parsons (as a charming young doctor!), Leslie Dwyer, and Allan Cuthbertson, does an excellent job. But the strength of the film lies in its script, economical yet full of telling lines and scenes. Janet Green was a class act, and Eyewitness is definitely an under-rated film, absolutely worth watching.

The film proved to be excellent, taut and highly entertaining. It must rank as one of the finest achievements of the director, the under-estimated Muriel Box. The suspense is maintained throughout, but there are also plenty of nice touches, including quite a bit of social comment and comedy, that make the watching experience very enjoyable. I'm surprised it isn't better known.

At the start, Jay Church (Michael Craig) buys a television on hire purchase, infuriating his wife Lucy (Muriel Pavlow, actually a former girlfriend of Edmund Crispin). The couple argue, and she storms out of the house, and goes to watch a film to simmer down. Becoming bored, she leaves her seat in the cinema, and chances upon an armed robbery. Two crooks (Donald Sinden and Nigel Stock) are robbing the manager's safe, but the manager turns up unexpectedly. While Barney (Stock, a future TV Dr Watson) chases Lucy, Wade (Sinden) shoots the manager dead. Lucy runs out into the street, and is knocked down by a bus.

Wade realises that he needs to silence Lucy, and discovers the hospital she's been taken to. Together with the hapless Barney, he follows her there. But things get complicated, as the ward is busy, with an eagle-eyed sister, an extremely attractive nurse (Belinda Lee, who five years later was tragically killed in a car crash at the age of 26), a chatty old patient, and an inquisitive young girl. Tension builds as Wade's murderous designs are thwarted more than once.

The wonderful cast, which also includes Richard Wattis, Nicholas Parsons (as a charming young doctor!), Leslie Dwyer, and Allan Cuthbertson, does an excellent job. But the strength of the film lies in its script, economical yet full of telling lines and scenes. Janet Green was a class act, and Eyewitness is definitely an under-rated film, absolutely worth watching.

Published on September 16, 2018 14:15

The Commuter and The Negotiator (aka Beirut) - two 2018 films

When I travelled to Florida recently, the long trip gave me time to read a number of books and to watch a number of movies. Today I'll talk about a couple of the films I watched, two thrillers that made for good aeroplane entertainment.

Liam Neeson is an actor I really like; his combination of crumpled charm and ordinary man turned tough guy heroics isn't easy to resist even if his performances follow a very similar pattern. In The Commuter, he plays a decent family man down on his luck, an ex-cop who is sacked from his job through no fault of his own. As always in films and television, the dismissal is conducted in an off-the-cuff manner that (after my years as an employment lawyer) I find risibly crude and implausible because it's an invitation to litigation that no boss in his right mind would risk. But since it's not a story about employment law, perhaps this is nothing to worry about unduly.

On the train back home, Neeson is approached by a pleasant, mysterious woman, who offers him $100,000 dollars to undertake an apparently simple task. Needless to say, there's a catch...before long, he's involved in a frantic race against time to find which of his fellow passengers is a mysterious character called Prynne, and to figure out why it matters. Yes, it's hokum, but it makes for enjoyable and exciting viewing.

The Negotiator, also known as Beirut, features another class act, Jon Hamm, in the lead role. He plays Mason Skiles, a top diplomat in the Lebanon whose life is wrecked in 1972, when his wife is killed. He returns to the US, and becomes a workplace negotiator before being summoned back to Beirut when his old friend Cal is kidnapped by terrorists.

The screenplay is written by Tony Gilroy, responsible for the Bourne movies, and it's quite accomplished, but it seemed to me that Gilroy was trying to achieve something more than an action thriller, and I'm not quite sure he managed it. Hamm's relationship with Rosamund Pike, one of the kidnap negotiation team, for instance, is rather inadequately developed, while the eternally elaborate politics of the Middle East are tackled in a serious way, but without casting any real light. John Le Carre would, I think, have made more of the material. So what we are left with is an action movie, and it's a perfectly good one, hardly memorable, but a very good way to spend time on a long flight.

Liam Neeson is an actor I really like; his combination of crumpled charm and ordinary man turned tough guy heroics isn't easy to resist even if his performances follow a very similar pattern. In The Commuter, he plays a decent family man down on his luck, an ex-cop who is sacked from his job through no fault of his own. As always in films and television, the dismissal is conducted in an off-the-cuff manner that (after my years as an employment lawyer) I find risibly crude and implausible because it's an invitation to litigation that no boss in his right mind would risk. But since it's not a story about employment law, perhaps this is nothing to worry about unduly.

On the train back home, Neeson is approached by a pleasant, mysterious woman, who offers him $100,000 dollars to undertake an apparently simple task. Needless to say, there's a catch...before long, he's involved in a frantic race against time to find which of his fellow passengers is a mysterious character called Prynne, and to figure out why it matters. Yes, it's hokum, but it makes for enjoyable and exciting viewing.

The Negotiator, also known as Beirut, features another class act, Jon Hamm, in the lead role. He plays Mason Skiles, a top diplomat in the Lebanon whose life is wrecked in 1972, when his wife is killed. He returns to the US, and becomes a workplace negotiator before being summoned back to Beirut when his old friend Cal is kidnapped by terrorists.

The screenplay is written by Tony Gilroy, responsible for the Bourne movies, and it's quite accomplished, but it seemed to me that Gilroy was trying to achieve something more than an action thriller, and I'm not quite sure he managed it. Hamm's relationship with Rosamund Pike, one of the kidnap negotiation team, for instance, is rather inadequately developed, while the eternally elaborate politics of the Middle East are tackled in a serious way, but without casting any real light. John Le Carre would, I think, have made more of the material. So what we are left with is an action movie, and it's a perfectly good one, hardly memorable, but a very good way to spend time on a long flight.

Published on September 16, 2018 05:11