Martin Edwards's Blog, page 118

October 26, 2018

Forgotten Book - The Murder of Martin Fotherill

Edward C. Lester is a little-known Golden Age writer who appears only to have written two books, both in the late 1930s. I hope to write about The Guy Fawkes Murder, the first of them, before long, but today my focus is on his second book, The Murder of Martin Fotherill. Both novels feature an elderly amateur sleuth called Moody. He's very much in the tradition of the Great Detective, and has an obliging Watson in the person of the narrator, a chap called Warrington.

The story begins with a man called David Fotherill reporting to the police that his brother Martin is missing. The authorities are not unduly concerned at first, but then a body is found...by none other than Moody. Needless to say, he feel impelled to investigate, and given that Warrington was a work colleague of both the Fotherill brothers, he calls on his assistance.

The book reminded me of the fiction of Rupert Penny, a very clever writer who poured out Golden Age mysteries in the run-up to the Second World War before giving up the genre. Rather like Penny, Lester shows himself a master of the Golden Age conventions. We are offered a cipher, a challenge to the reader, and cluefinder footnotes. There are also numerous references to major Golden Age writers, such as Crofts and Austin Freeman, while Lester also borrows one trick from Richard Hull.

I enjoyed this book, and it's a pity that Lester (about whom I know very little, other than that he attended Westminster School) did not continue to write detective stories. The story begins splendidly, though I must say I felt it sagged after about half-way, as Lester piled on the complications rather too vigorously - I felt myself losing the will to live during the unravelling of the cipher. But for all that, it's a fun mystery, and doesn't deserve the total neglect which has been its fate.

The story begins with a man called David Fotherill reporting to the police that his brother Martin is missing. The authorities are not unduly concerned at first, but then a body is found...by none other than Moody. Needless to say, he feel impelled to investigate, and given that Warrington was a work colleague of both the Fotherill brothers, he calls on his assistance.

The book reminded me of the fiction of Rupert Penny, a very clever writer who poured out Golden Age mysteries in the run-up to the Second World War before giving up the genre. Rather like Penny, Lester shows himself a master of the Golden Age conventions. We are offered a cipher, a challenge to the reader, and cluefinder footnotes. There are also numerous references to major Golden Age writers, such as Crofts and Austin Freeman, while Lester also borrows one trick from Richard Hull.

I enjoyed this book, and it's a pity that Lester (about whom I know very little, other than that he attended Westminster School) did not continue to write detective stories. The story begins splendidly, though I must say I felt it sagged after about half-way, as Lester piled on the complications rather too vigorously - I felt myself losing the will to live during the unravelling of the cipher. But for all that, it's a fun mystery, and doesn't deserve the total neglect which has been its fate.

Published on October 26, 2018 11:12

October 23, 2018

The Circe Complex - DVD review

The Circe Complex was a six-part serial in the ITV Armchair Thriller series way back in 1980. The screenplay was written by David Hopkins and based on a novel by Desmond Cory, an interesting and accomplished author whom I've talked about before. I've not read the book, but I'd like to, and frankly I suspect it may have more to offer than the TV version, which is now available as a DVD. It's interesting, but in some respects unsatisfactory.

The story begins with Tom Foreman leaving his extremely attractive wife Val at home one day, only to kill a policeman for no obvious reason. He ends up in prison, and it emerges that he's stolen some very valuable jewels, and hidden them somewhere. But where are they? Val teams up with an oddball psychiatrist (Alan David, who gives a suitably melodramatic performance) to find out.

The pair organise a jailbreak, but events take a curious turn as Val becomes involved first with the villain who helps to spring Tom, and then with one of the cops who is investigating the case. It becomes clear that Val is indeed a Circe-like character. Beth Morris, a Welsh actress I've never come across elsewhere, is suitably seductive and sinister; she handles a difficult role well, and I'm rather surprised that (although she evidently enjoyed a fairly successful career) she didn't become a bigger star.

Overall, though, I felt this was a rather eccentric mystery, and somewhat frustrating, because there was a sense from start to finish of compelling ingredients inadequately blended together. Whose fault that was, I'm not sure. Yet despite my reservations, I don't regret having watched the show. Cory was full of interesting ideas and insights into human behaviour - his strange book Bennett is an excellent example of this - and The Circe Complex, for all its failings, is an intriguing mystery.

The story begins with Tom Foreman leaving his extremely attractive wife Val at home one day, only to kill a policeman for no obvious reason. He ends up in prison, and it emerges that he's stolen some very valuable jewels, and hidden them somewhere. But where are they? Val teams up with an oddball psychiatrist (Alan David, who gives a suitably melodramatic performance) to find out.

The pair organise a jailbreak, but events take a curious turn as Val becomes involved first with the villain who helps to spring Tom, and then with one of the cops who is investigating the case. It becomes clear that Val is indeed a Circe-like character. Beth Morris, a Welsh actress I've never come across elsewhere, is suitably seductive and sinister; she handles a difficult role well, and I'm rather surprised that (although she evidently enjoyed a fairly successful career) she didn't become a bigger star.

Overall, though, I felt this was a rather eccentric mystery, and somewhat frustrating, because there was a sense from start to finish of compelling ingredients inadequately blended together. Whose fault that was, I'm not sure. Yet despite my reservations, I don't regret having watched the show. Cory was full of interesting ideas and insights into human behaviour - his strange book Bennett is an excellent example of this - and The Circe Complex, for all its failings, is an intriguing mystery.

Published on October 23, 2018 00:30

October 22, 2018

Salisbury Literary Festival

I've returned from a thoroughly enjoyable trip to Wiltshire, which arose from an invitation to take part in the Salisbury Literary Festival, which is in its second year. As the world knows, a terrible crime was perpetrated in this lovely cathedral city earlier this year, and it's had an adverse effect on trade which is continuing. So I was especially glad to show my support, not only for an excellent festival, but also for Salisbury itself. The city is definitely open for business, and it's a great destination. The unlikely crime scene (or at least, the place where the Skripals were taken ill) is shown in the photo below. On a lighter note, I was amused by Fudgehenge!

I was interviewed by Tom Bromley, the Festival Director, at the Salisbury Playhouse, a very good venue which attracted a splendid audience (who were also able to see a panel of four leading female crime writers after my session). The main subject was Dorothy L. Sayers, who was educated at the Godolphin School in Salisbury, and the interview was fun. For me, certainly, and I hope also the audience. A special pleasure was the chance to stay at Sarum College in the Cathedral Close (above), with a view of the famous cathedral spire, which really was stunning. The great novelist William Golding once lived a few doors away.

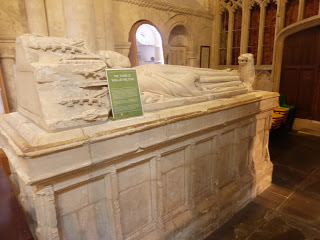

When travelling such a distance, I usually like - if possible - to fit in some sightseeing, if not other events, so as to make best use of the time. On the way down, therefore, I stopped off at Cirencester, a town I've visited before, and at Malmesbury, which was new to me and quite delightful: the old abbey is the resting place of King Athelstan, and the whole town brims with history. There was also a trip to Mottisfont Abbey, an excellent National Trust property (as is Mompesson House in Salisbury's cathedral close, which proved well worth a visit).

I broke up the long drive back to Cheshire by stopping at Marlborough, and seizing the chance to call in at the White Horse Bookshop (excellent) and sign Gallows Court and British Library anthologies. Then it was on to Silbury Hill (the largest prehistoric mound in Europe!) and the incredible Avebury stone circle. I've never been to Avebury before, but the combination of wonderful sunny weather and first class sights made the visit truly memorable. It's a World Heritage Site, and for good reason. If you've never been there, I can thoroughly recommend it.

Published on October 22, 2018 02:58

October 19, 2018

Forgotten Book - The Getaway

Because of my keen and lifelong enthusiasm for Golden Age detective fiction, people sometimes express surprise when I mention the American hardboiled books that I admire. But there's nothing inconsistent about liking both types of writing, far from it. I like good crime fiction of all kinds, and today's Forgotten Book is an example. It's The Getaway, by Jim Thompson.

Thompson was an interesting character, and not long ago I read his biography, Savage Art, by Robert Polito, which is informative and very well-written. Although he died in obscurity, Thompson predicted that he'd become famous, and there was a great revival of interest in his work a few years after his death. Several of his novels have been filmed, and indeed The Getaway was filmed by Sam Peckinpah while Thompson was still alive.

It's a book that I find quite remarkable. The central story concerns a bank robber, Carter "Doc" McCoy, who is married to a former librarian called Carol, who takes to the criminal life with gusto. Doc is unwise enough to collaborate with a villain called Rudy Torrento, and inevitably "the perfect job" goes wrong. Doc and Carol end up fleeing for their lives, with the forces of law and order after them, as well as Rudy.

The story of their fugitive experience is gripping, but Thompson has up his sleeve a final chapter that is, by any standards, quite stunning. I can't think of anything quite like it in the crime genre. Not even Sam Peckinpah, incidentally, was up to the task of trying to film it (rather like Hitchcock's failure to master the dark finale of Francis Iles' Before the Fact - you knew I'd get a Golden Age reference in somewhere, didn't you?!) I really enjoyed this book.

Recently, by the way, I've also read Thompson's After Dark, My Sweet. This is another good and highly readable book, narrated by a strangely sympathetic psychopath, though I wouldn't rate it as highly as The Getaway.

Thompson was an interesting character, and not long ago I read his biography, Savage Art, by Robert Polito, which is informative and very well-written. Although he died in obscurity, Thompson predicted that he'd become famous, and there was a great revival of interest in his work a few years after his death. Several of his novels have been filmed, and indeed The Getaway was filmed by Sam Peckinpah while Thompson was still alive.

It's a book that I find quite remarkable. The central story concerns a bank robber, Carter "Doc" McCoy, who is married to a former librarian called Carol, who takes to the criminal life with gusto. Doc is unwise enough to collaborate with a villain called Rudy Torrento, and inevitably "the perfect job" goes wrong. Doc and Carol end up fleeing for their lives, with the forces of law and order after them, as well as Rudy.

The story of their fugitive experience is gripping, but Thompson has up his sleeve a final chapter that is, by any standards, quite stunning. I can't think of anything quite like it in the crime genre. Not even Sam Peckinpah, incidentally, was up to the task of trying to film it (rather like Hitchcock's failure to master the dark finale of Francis Iles' Before the Fact - you knew I'd get a Golden Age reference in somewhere, didn't you?!) I really enjoyed this book.

Recently, by the way, I've also read Thompson's After Dark, My Sweet. This is another good and highly readable book, narrated by a strangely sympathetic psychopath, though I wouldn't rate it as highly as The Getaway.

Published on October 19, 2018 04:37

October 17, 2018

The Running Man - 1963 film review

The Running Man is a film I've wanted to watch for a long time, and thanks to the Talking Pictures channel, I've finally caught up with it. The reason for my interest was that, many years ago, I read the novel on which the movie is based - The Ballad of the Running Man by Shelley Smith, an author I've discussed several times on this blog, as well as in The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books. What I hadn't realised was that the screenplay was written by John Mortimer, in itself a recommendation.

As well as the ingredients of a good source novel and a good scriptwriter, the film also benefited from a first-rate cast, a good director (Carol Reed) and a theme tune by Ron Grainer. Yet it wasn't a big success - some people claimed that this was because the two stars were Laurence Harvey and Lee Remick and in the wake of the JFK assassination, "Lee" and "Harvey" had unfortunate connotations. Hmmm....Anyway, I found it a very watchable piece of work, quite tense at times, although also rather low-key.

In essence, it's an insurance scam story. Harvey plays Rex Blake, charismatic but reckless, a glider pilot who feels he's been cheated by an insurance company, and that this entitles him to commit fraud by faking his own death. So it's a "Canoe Man" type of story, but with a glider substituted for a canoe. Alan Bates plays the insurance investigator who seems to suspect that something is amiss - but the pay-out is made.

Rex resurfaces in Spain, under a false identity, where his wife (Remick) joins him. All seems to be going well until Bates suddenly turns up. What is his game? A cat-and-mouse story ensues, and I thought Mortimer maintained the suspense pretty well until the end. The novel was published in 1961, when Smith was at the height of her powers, but she only published two more books, both in the 1970s, and neither made any great impression. I've always been puzzled by this, and I'd love to learn more about why her career fizzled out in this way.

As well as the ingredients of a good source novel and a good scriptwriter, the film also benefited from a first-rate cast, a good director (Carol Reed) and a theme tune by Ron Grainer. Yet it wasn't a big success - some people claimed that this was because the two stars were Laurence Harvey and Lee Remick and in the wake of the JFK assassination, "Lee" and "Harvey" had unfortunate connotations. Hmmm....Anyway, I found it a very watchable piece of work, quite tense at times, although also rather low-key.

In essence, it's an insurance scam story. Harvey plays Rex Blake, charismatic but reckless, a glider pilot who feels he's been cheated by an insurance company, and that this entitles him to commit fraud by faking his own death. So it's a "Canoe Man" type of story, but with a glider substituted for a canoe. Alan Bates plays the insurance investigator who seems to suspect that something is amiss - but the pay-out is made.

Rex resurfaces in Spain, under a false identity, where his wife (Remick) joins him. All seems to be going well until Bates suddenly turns up. What is his game? A cat-and-mouse story ensues, and I thought Mortimer maintained the suspense pretty well until the end. The novel was published in 1961, when Smith was at the height of her powers, but she only published two more books, both in the 1970s, and neither made any great impression. I've always been puzzled by this, and I'd love to learn more about why her career fizzled out in this way.

Published on October 17, 2018 11:12

October 15, 2018

The Big Somewhere by Steven Powell

The growth of academic interest in crime fiction over the past few decades has been quite stunning. When Julian Symons published the first edition of Bloody Murder in 1972, very few scholarly studies of the genre were available. Since then, hundreds have been published, and some of them have been extremely interesting. Crime has become a "respectable" subject for academic study,, something I think is really rather wonderful and indeed overdue. Yet it's striking that not one of these academic books has had as much impact as Symons' book.

Why is this? Certainly, there are many insightful and scholarly studies of the genre which have taught me a good deal. But there is also a sense that some academic books represent the work of a small group of people talking to themselves, rather than to the wider community of crime fans or crime writers. Too often they don't seem designed to be read. It's not uncommon, for example, to find endless pages devoted to turgid footnotes which seem designed mainly to prove that the authors have done their homework and which, I suspect, hardly anyone finds useful. In my opinion, that's a real pity.

Happily, there are signs that things are changing for the better. Not long after The Golden Age of Murder was published, I was invited to take part in a symposium focusing on the work of James Ellroy at the University of Liverpool. The event was organised by a lecturer at the university, Steven Powell, who has specialised in writing about American crime fiction, and in particular about Ellroy. I really enjoyed taking part (and meeting, amongst others, Woody Haut, whose excellent books about hardboiled crime fiction, and its links with Hollywood, have long appealed to me).

I also found that I enjoyed reading Steven's own writings, which seemed punchier and more accessible than much other academic work about the genre. An excellent example of this approach is to be found in a collection of essays that he edited, 100 American Crime Writers.

Now Steven has a new book out; The Big Somewhere is published by Bloomsbury, and comprises a range of essays by various authors (including Woody Haut) on the subject of Ellroy's fiction. My interest in Ellroy dates back to the late 80s, and although I've not read much of his work of late, I attended a talk he gave in Manchester some years ago (making sure that he inscribed some of his books to me!) and found him as remarkable in person as he is in print. There is nobody quite like "the Demon Dog".

His unique qualities as a crime writer are well captured, and cogently analysed, in The Big Somewhere. In addition to a general introduction, Steven Powell contributes the first essay in the book, and co-authors the tenth and concluding essay, which deals with Ellroy's influence on the British writer David Peace. It's always the case with a book of this kind (as it is with an anthology of short stories) that one will not rate every contribution equally highly, but I found something of interest in all of them. Diana Powell's study of Ellroy's influence on Megan Abbott (in her earlier novels, at least) is particularly thought-provoking.

Because I'm a fan of books about the genre, I'm keen to see a narrowing of the gap between academic studies and more popular accounts of crime fiction, such as Bloody Murder. Novelists like me who are interested in the genre's range and possibilities can learn a great deal from the academics, and I think it's fair to say that there are some academics who could profitably study the art of writing entertainingly. Books like The Big Somewhere, which contain a good deal of valuable information without becoming unduly bogged down by scholar-speak, point the way forward. I enjoyed reading this book, (and not only because of the absence of tedious footnotes in tiny print!) I think that anyone who is a serious Ellroy fan will find The Big Somewhere insightful and interesting.

Why is this? Certainly, there are many insightful and scholarly studies of the genre which have taught me a good deal. But there is also a sense that some academic books represent the work of a small group of people talking to themselves, rather than to the wider community of crime fans or crime writers. Too often they don't seem designed to be read. It's not uncommon, for example, to find endless pages devoted to turgid footnotes which seem designed mainly to prove that the authors have done their homework and which, I suspect, hardly anyone finds useful. In my opinion, that's a real pity.

Happily, there are signs that things are changing for the better. Not long after The Golden Age of Murder was published, I was invited to take part in a symposium focusing on the work of James Ellroy at the University of Liverpool. The event was organised by a lecturer at the university, Steven Powell, who has specialised in writing about American crime fiction, and in particular about Ellroy. I really enjoyed taking part (and meeting, amongst others, Woody Haut, whose excellent books about hardboiled crime fiction, and its links with Hollywood, have long appealed to me).

I also found that I enjoyed reading Steven's own writings, which seemed punchier and more accessible than much other academic work about the genre. An excellent example of this approach is to be found in a collection of essays that he edited, 100 American Crime Writers.

Now Steven has a new book out; The Big Somewhere is published by Bloomsbury, and comprises a range of essays by various authors (including Woody Haut) on the subject of Ellroy's fiction. My interest in Ellroy dates back to the late 80s, and although I've not read much of his work of late, I attended a talk he gave in Manchester some years ago (making sure that he inscribed some of his books to me!) and found him as remarkable in person as he is in print. There is nobody quite like "the Demon Dog".

His unique qualities as a crime writer are well captured, and cogently analysed, in The Big Somewhere. In addition to a general introduction, Steven Powell contributes the first essay in the book, and co-authors the tenth and concluding essay, which deals with Ellroy's influence on the British writer David Peace. It's always the case with a book of this kind (as it is with an anthology of short stories) that one will not rate every contribution equally highly, but I found something of interest in all of them. Diana Powell's study of Ellroy's influence on Megan Abbott (in her earlier novels, at least) is particularly thought-provoking.

Because I'm a fan of books about the genre, I'm keen to see a narrowing of the gap between academic studies and more popular accounts of crime fiction, such as Bloody Murder. Novelists like me who are interested in the genre's range and possibilities can learn a great deal from the academics, and I think it's fair to say that there are some academics who could profitably study the art of writing entertainingly. Books like The Big Somewhere, which contain a good deal of valuable information without becoming unduly bogged down by scholar-speak, point the way forward. I enjoyed reading this book, (and not only because of the absence of tedious footnotes in tiny print!) I think that anyone who is a serious Ellroy fan will find The Big Somewhere insightful and interesting.

Published on October 15, 2018 08:28

October 12, 2018

Forgotten Book - Cutter and Bone

Many years ago, I watched and enjoyed the film Cutter's Way. This prompted me, some time later, to pick up a paperback edition of Cutter and Bone, by Newton Thornburg, on which the movie was based. But the novel languished on my to-be-read pile for ages. I finally took it with me when I headed off to Tallinn Literary Festival earlier this year, and flight delays meant that I read it from cover to cover on the excessively long journey home. The novel was so impressive that I quite forgot my frustration at the hopelessness of the airline in question.

The book is a crime story, certainly, but above all it's a study of a relationship between two men, and of an America struggling to come to terms with the impact of the Vietnam War. One of those men is Richard Bone, who gave up his career in advertising (Thornburg had worked as a copywriter himself) and his marriage to become a drifter using his good looks and charm to persuade women to spend money on him. One night, Bone abandons a woman only for his car to break down. Then he witnesses a man putting something into a trashcan. Soon it becomes clear that he's seen a murderer disposing of the remains of his victim, a young woman.

When Bone thinks he recognises the killer, from a newspaper photograph of a ranching tycoon called J. J. Wolfe, his pal Alex Cutter dreams up a fanciful extortion plan. Cutter is a Vietnam veteran, whose combat experience has left him with one leg, one eye, a lot of scar tissue, and a hatred of elites. Cutter lives with a woman called Mo, mother of his child, whom Bone is crazy about, and the complexity of their relations is superbly portrayed.

The victim's sister becomes involved with the extortion racket, and later a young woman called Monk joins up with Cutter and Bone as they embark on a crazy trip to the Ozarks (where Thornburg, like Wolfe, farmed cattle) to confront the killer - assuming he is a killer, that is. Bone really isn't sure.

The story blends the grotesque and the poignant, the witty and the macabre, in a way that isn't quite like any other novel. I agree with George P. Pelecanos, who wrote an intro to my edition of the book, that the occasional comparison made between Thornburg's novel and the work of Ross Macdonald is no help at all. This is a genuinely original story, and one that has lingered in my mind ever since I read the final, shocking scene. Highly recommended.

The book is a crime story, certainly, but above all it's a study of a relationship between two men, and of an America struggling to come to terms with the impact of the Vietnam War. One of those men is Richard Bone, who gave up his career in advertising (Thornburg had worked as a copywriter himself) and his marriage to become a drifter using his good looks and charm to persuade women to spend money on him. One night, Bone abandons a woman only for his car to break down. Then he witnesses a man putting something into a trashcan. Soon it becomes clear that he's seen a murderer disposing of the remains of his victim, a young woman.

When Bone thinks he recognises the killer, from a newspaper photograph of a ranching tycoon called J. J. Wolfe, his pal Alex Cutter dreams up a fanciful extortion plan. Cutter is a Vietnam veteran, whose combat experience has left him with one leg, one eye, a lot of scar tissue, and a hatred of elites. Cutter lives with a woman called Mo, mother of his child, whom Bone is crazy about, and the complexity of their relations is superbly portrayed.

The victim's sister becomes involved with the extortion racket, and later a young woman called Monk joins up with Cutter and Bone as they embark on a crazy trip to the Ozarks (where Thornburg, like Wolfe, farmed cattle) to confront the killer - assuming he is a killer, that is. Bone really isn't sure.

The story blends the grotesque and the poignant, the witty and the macabre, in a way that isn't quite like any other novel. I agree with George P. Pelecanos, who wrote an intro to my edition of the book, that the occasional comparison made between Thornburg's novel and the work of Ross Macdonald is no help at all. This is a genuinely original story, and one that has lingered in my mind ever since I read the final, shocking scene. Highly recommended.

Published on October 12, 2018 03:42

October 10, 2018

Amsterdam

I've returned from a short and exhilarating break in sunny Amsterdam, a city I'd not visited for more than thirty years. Eurostar now runs there directly (though you have to change trains on the way back for some reason) and this made for a very convenient trip, as I'd been down in London, seeing friends, publishers, and my son/travelling companion.

To get in the mood for the trip, I took another look at the work of two notable crime writers, both now deceased, whose first novels were respectively Love in Amsterdam and Outsider in Amsterdam. The authors in question were Nicolas Freeling, an Englishman who spent much of his life on the other side of the Channel, and the even more widely travelled Janwillem Van de Wetering.

In their day, this pair were leading figures in the genre, although inevitably one hears less about them nowadays, and Van de Wetering's books aren't particularly easy to find. But both men were quirky, unorthodox characters and their fiction, which is certainly worth seeking out (though I found one or two of Freeling's later books rather dull - the Van der Valk series remains his strength), reflected their wide range of interests.

As for Amsterdam, it shone in the sunlight. The Rijksmuseum occupied almost a full day - there is so much to see - and Vondel Park was lovely to walk around. A lengthy canal trip and a bus tour gave a good overall perspective of the city (and travelling by canal and bus does at least enable one to minimise the risk of being mowed down by one of the innumerable cyclists - crossing a road is not for the faint-hearted), while the Oude Kirche, the city's oldest building, was wonderfully tranquil, even if it is situated in the heart of the red light district.

And there was a bonus for me, one of those pleasant moments that make the writing life seem highly gratifying. When I wandered into a bookshop, I was confronted by copies of Gallows Court and The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books. And the lovely assistant proved to be a Golden Age fan who uses the latter book as a reference guide. Good for morale! It all contributed to an exceptionally enjoyable few days.

Published on October 10, 2018 04:16

October 8, 2018

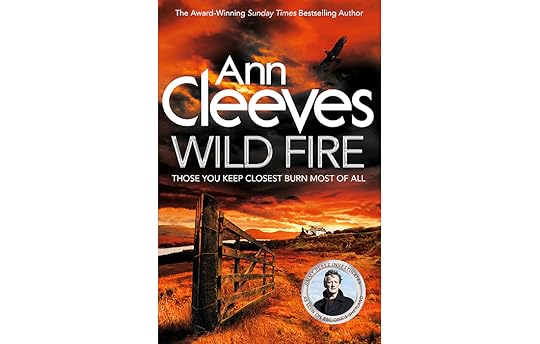

Wild Fire by Ann Cleeves

The crime writing career of Ann Cleeves is an excellent example of the mercurial nature of this extraordinary profession. She was quietly producing very good books for many years before her first Shetland novel, Raven Black, won the CWA Gold Dagger, an achievement swiftly followed by two enormously popular TV series, Vera and Shetland. She's now one of the genre's superstars, but her feet remain firmly rooted on the ground, and she often mentions when giving talks how lucky she's been. Well, up to a point that's bound to be true, and luck is generally necessary in life, but it's also true that in certain respects one makes one's own luck. The fact is that her books have always been enjoyable reads, with a particular strength in the evocation of landscape. We became friends more years ago than either of us cares to remember, and I've found it both wonderful and extremely fascinating to follow her progress.

Which brings me to her new book, Wild Fire, announced as the last Shetland novel (that might, of course, not necessarily also mean the last Jimmy Perez novel, although the publisher's flyer implies that it is - we'll have to wait and see). Ann originally planned the Shetland books as a quartet, but their success meant that four more were commissioned. It's a shame to see such a good series come to an end, but I think it's a sensible decision. Sometimes, a popular series character outstays his or her welcome - I read a book by a fine author (now deceased) the other day; it was written towards the end of the author's career, and featured her regular detective, but I felt it just wasn't up to standard.

No danger of that with Wild Fire. I've been reading Ann's books since before we first met, and I feel this is one of her very best, showing her talents to best advantage. The blend of setting, characterisation, and plot is excellent. I also liked, incidentally, the endpaper map of Shetland; a nod to the classic tradition, yes, but also helpful to readers unfamiliar with the geography of the islands. The book is dedicated to Ann's late husband Tim, who died suddenly last year, a few short weeks after celebrating with the family the award to her of the CWA Diamond Dagger.

What of the mystery? An English family have moved to Shetland, hoping to give their son Christopher, who is on the autistic spectrum, a better life. Unfortunately they become embroiled in a murder case - the victim is a young woman hired by a doctor and his wife to look after their children. The story encompasses important social issues, not just autism but also domestic violence, yet - crucially - this isn't done in a preachy way or at the expense of the narrative momentum. This book is bound to be a bestseller, but so was the disappointing book by the other author I mentioned earlier. What matters much more is that Wild Fire is an excellent example of the traditional detective story, written by an author at the height of her powers.

Published on October 08, 2018 03:00

October 5, 2018

Forgotten Book - My Name is Michael Sibley

Someone asked me recently about whether I ever bother to re-read crime novels. When so many remain unread, logically, can it be a good use of time to revisit books one has read before? Well, I do re-read books, for a variety of reasons. Sometimes it's simply because I love them. Sometimes, too, I'm prepared to give a second chance to a book that disappointed me first time around. The latter course may be risky, but sometimes it reaps dividends.

So it was with John Bingham's debut novel, My Name is Michael Sibley. The book came out in 1952, and was praised by Julian Symons in Bloody Murder, which led me to seek it out. I must have been in my early twenties when I read it, perhaps younger, and I felt that Symons had over-praised it. But when I read it again recently, I saw why Symons liked it, and appreciated Bingham's achievement as I should have done the first time around.

The book is told in the first person by, you guessed it, Michael Sibley. He's a professional writer, and a friend of his from school days has been found dead in suspicious circumstances. A police inspector and sergeant, whose names are never revealed, come to interview him, and he tells a less than truthful story. As events unfold, this proves to have been a serious error. Along the way, we learn about the nature of the supposed friendship between Sibley and the dead man.

I suppose that, originally, I was disappointed partly by the lack of a clever twist to the murder mystery, and partly by the fact that Sibley is a deeply flawed man, hard to warm to. Nowadays, I'm much readier to appreciate the cleverness of Bingham in the way he tells his story. I suspect this book had a considerable influence on Symons' books, and I also feel that there are elements of the story which suggest that Bingham himself was influenced by Francis Iles. Be that as it may, it's a good novel, and I'm really glad I re-read it.

So it was with John Bingham's debut novel, My Name is Michael Sibley. The book came out in 1952, and was praised by Julian Symons in Bloody Murder, which led me to seek it out. I must have been in my early twenties when I read it, perhaps younger, and I felt that Symons had over-praised it. But when I read it again recently, I saw why Symons liked it, and appreciated Bingham's achievement as I should have done the first time around.

The book is told in the first person by, you guessed it, Michael Sibley. He's a professional writer, and a friend of his from school days has been found dead in suspicious circumstances. A police inspector and sergeant, whose names are never revealed, come to interview him, and he tells a less than truthful story. As events unfold, this proves to have been a serious error. Along the way, we learn about the nature of the supposed friendship between Sibley and the dead man.

I suppose that, originally, I was disappointed partly by the lack of a clever twist to the murder mystery, and partly by the fact that Sibley is a deeply flawed man, hard to warm to. Nowadays, I'm much readier to appreciate the cleverness of Bingham in the way he tells his story. I suspect this book had a considerable influence on Symons' books, and I also feel that there are elements of the story which suggest that Bingham himself was influenced by Francis Iles. Be that as it may, it's a good novel, and I'm really glad I re-read it.

Published on October 05, 2018 11:19