Martin Edwards's Blog, page 126

May 2, 2018

Malice Domestic

I'm back home from Malice Domestic 30. Malice is an excellent convention that I've recommended before and will definitely be recommending many times in the future; it's for all those who enjoy the traditional mystery. It's also very slickly organised by an experienced Board whose hard-working members are committed to making sure that everyone has a great time. This year, the convention moved to a new hotel, still in Bethesda, Maryland, and conveniently close to a Metro station, so that I was able to fit in some sight-seeing in Washington DC before the festivities began.

Those sights included the lovely garden at Dumbarton Oaks, where the spring blossom was gorgeous and memorable, and the famous steps which feature in the film of The Exorcist. Naturally, I fitted in second hand bookshop or two, though for once I resisted the temptation to purchase, knowing that many good books would await me at Malice. Washington DC is a marvellous tourist spot, and the Georgetown area is among its attractive destinations. For dinner, a historic restaurant with the irresistible name of Martin's Tavern proved a brilliant recommendation, not just because the food was good but because it's a place brimming with atmosphere and history; among other things, it's where JFK proposed to Jackie. And when the sun shone, I even found myself reading a book for an hour in the improbable setting of the middle of a busy roundabout, at the rather appealing Dupont Circle.

This year's recipient of the Poirot Award was Brenda Blethyn, twice-nominated for Academy Awards, and now renowned as DCI Vera Stanhope. As last year's recipient, I was asked to host a discussion with Brenda and Vera's creator, Ann Cleeves. There could have been no easier or more pleasurable task, and the vast ballroom was packed. The following day I was on an Agatha nominees panel with Cindy Callaghan and Mattias Bostrum, and then on Sunday Kristopher Zygorski moderated a panel about the darker side of traditional fiction with his customary verve.

As always at these events, there was a chance to catch up with old and valued friends, such as Doug Greene, Josh Pachter, Shelly Dickson Carr, Les and Leslie Blatt, Shawn Reilly Simmons, Cathy Ace, Michael Dirda, Janet Hutchings, and many more, as well as to make new ones - Mattias, Patricia Gouthro (who interviewed me for a research project), and Gabriel Valjean among others.

These contacts are a hugely enjoyable part of a convention, even if at times the whirl of activity can become a bit overwhelming. I have to admit that I was running out of energy before the time came to brave the long double flight back to Manchester, and I've arrived home rather wearily. But I need to spring back into action soon - my next flights and next festival are next week...

Published on May 02, 2018 07:51

April 30, 2018

Trial of Louise Masset - Notable British Trials No. 85

For anyone interested in the history of crime and punishment, the Notable British Trials series has long been a rich source of reliable information. The original series, published by William Hodge and Company, became extremely well-known, and its recent revival by Mango Books is welcome. The second of the "Mango" titles has now been published; it is the Trial of Louise Masset, edited by Kate Clarke.

I must admit that I knew next to nothing about this case, sometimes known as "the Dalston mystery", before picking up this book. It deals with that most horrible of crimes, the murder of a very young and defenceless child. The body was soon identified as three-year old Manfred Masset. His mother Louise was the prime suspect right from the outset.

Louise was a governess in her mid-thirties. Manfred was illegitimate, and in the late 1890s, that was of course a source of social stigma. The position of an unmarried mother was extremely difficult and stressful. Louise vehemently denied killing her own child. On her account she'd already arrived in Brighton, where she was planning to spend the week-end with her new lover, Eudore Lewis (Eudore is a new name to me, I must admit.) The couple registered in the hotel under false names, claiming to be brother and sister.

Louise's denials didn't persuade the police. Eventually, they failed to persuade the jury. She was sentenced to death, and became the first person to be executed in Britain in the 20th century, a miserable distinction. But as Kate Clarke explains, the case was less straightforward than it might seem. There are some remarkable ingredients, not least the involvement of Arthur Newton, the dodgiest solicitor of his era, who would later act for Dr Crippen. Train times come into the story, rather as in a mystery by Freeman Wills Crofts. All in all, a welcome addition to an excellent series.

I must admit that I knew next to nothing about this case, sometimes known as "the Dalston mystery", before picking up this book. It deals with that most horrible of crimes, the murder of a very young and defenceless child. The body was soon identified as three-year old Manfred Masset. His mother Louise was the prime suspect right from the outset.

Louise was a governess in her mid-thirties. Manfred was illegitimate, and in the late 1890s, that was of course a source of social stigma. The position of an unmarried mother was extremely difficult and stressful. Louise vehemently denied killing her own child. On her account she'd already arrived in Brighton, where she was planning to spend the week-end with her new lover, Eudore Lewis (Eudore is a new name to me, I must admit.) The couple registered in the hotel under false names, claiming to be brother and sister.

Louise's denials didn't persuade the police. Eventually, they failed to persuade the jury. She was sentenced to death, and became the first person to be executed in Britain in the 20th century, a miserable distinction. But as Kate Clarke explains, the case was less straightforward than it might seem. There are some remarkable ingredients, not least the involvement of Arthur Newton, the dodgiest solicitor of his era, who would later act for Dr Crippen. Train times come into the story, rather as in a mystery by Freeman Wills Crofts. All in all, a welcome addition to an excellent series.

Published on April 30, 2018 03:58

April 27, 2018

Forgotten Book - Death in Five Boxes

Death in Five Boxes is a novel featuring Sir Henry Merrivale that was first published in 1938. The author was Carter Dickson, the pen-name under which John Dickson Carr wrote about H.M., "the old man". And I must say that the opening scenario of this story shows Carr at his most brilliant. It's quite entrancing.

A young doctor, walking in central London one night, is accosted by a pretty young woman, who is a state of some distress. She wants him to accompany her into a house, and when he agrees to do so, first they encounter a blood-stained umbrella-cum-swordstick, and then they are presented with a bizarre situation. Five people in a room, four of them in a drugged state, the fifth one dead. One of those who is still alive is the young woman's father...

It's a great premise, and Carr develops it splendidly in the next chapters. All the people in the room are rich and well-known, all of them are - allegedly - criminals. What on earth do we make of the strange items found on their person, such as a smattering of quicklime, four watches, and part of the insides of an alarm clock? Not to mention the five boxes which apparently contain deadly secrets, and have been stolen from a solicitor's office. It's all weird, and all entrancing. Suffice to say that I was absolutely hooked.

Unfortunately, my enthusiasm waned as the story progressed. The complications about how the drug was administered began to wear me down, and the presence in the story of a renowned cat burglar rather irritated me (perhaps this was unreasonable of me). We are presented with a "least likely person" culprit, but I felt, again perhaps unreasonably, that this character's motivation hadn't been adequately foreshadowed. Maybe I wasn't paying close enough attention. In the end, I felt that a superb situation was rather inadequately resolved. But full marks for the set-up; it really did grip me.

A young doctor, walking in central London one night, is accosted by a pretty young woman, who is a state of some distress. She wants him to accompany her into a house, and when he agrees to do so, first they encounter a blood-stained umbrella-cum-swordstick, and then they are presented with a bizarre situation. Five people in a room, four of them in a drugged state, the fifth one dead. One of those who is still alive is the young woman's father...

It's a great premise, and Carr develops it splendidly in the next chapters. All the people in the room are rich and well-known, all of them are - allegedly - criminals. What on earth do we make of the strange items found on their person, such as a smattering of quicklime, four watches, and part of the insides of an alarm clock? Not to mention the five boxes which apparently contain deadly secrets, and have been stolen from a solicitor's office. It's all weird, and all entrancing. Suffice to say that I was absolutely hooked.

Unfortunately, my enthusiasm waned as the story progressed. The complications about how the drug was administered began to wear me down, and the presence in the story of a renowned cat burglar rather irritated me (perhaps this was unreasonable of me). We are presented with a "least likely person" culprit, but I felt, again perhaps unreasonably, that this character's motivation hadn't been adequately foreshadowed. Maybe I wasn't paying close enough attention. In the end, I felt that a superb situation was rather inadequately resolved. But full marks for the set-up; it really did grip me.

Published on April 27, 2018 02:30

April 25, 2018

Quai des Orfevres - film review

The famous French film director Henri-Georges Clouzot was a fan of the Belgian crime writer Stanislas-Andre Steeman, and one of his most highly regarded movies, Quai des Orfevres, is among his adaptations of Steeman's fiction. So the story goes, Clouzot started writing the script without having access to the novel, Legitime Defense, which had been published during the war and was out of print at the time. And this reflects the fact that Clouzot, like his English counterpart Hitchcock, was not primarily concerned with whodunit.

The story features Jenny, played by Clouzot's long-time companion Suzy Delair (still alive, I gather, at the splendid age of 100), who is a talented and sexy singer and a performer ambitious to get on in the world. She's married to Martineau (Bernard Blier), a quiet pianist who is driven to jealousy by her flirtatious ways. She cares for him, but is determined not to allow him to dominate her or wreck her prospects of fame.

A wealthy old lecher called Brignon takes a fancy to Jenny, in a scenario which, unfortunately, remains topical to this day. Martineau begs Jenny not to agree to see Brignon again, but she reckons she can take care of herself. He constructs an alibi at a theatre while following her to the place where he reckons she is due to meet Brignon, only to find that Brignon is dead. It seems clear that Jenny has killed him, and Martineau can't resist the temptation to interfere with the crime scene. Meanwhile, Jenny's friend Dora, a photographer who used to take nude pictures of Brignon's conquests, tries to help her out.

Louis Jouvet plays the detective who is soon on the trail. His performance is highly enjoyable, and overall this is a film which has earned the critics' admiration over the years. It has a depth, as well as a number of very pleasing touches, and it's probably one of those films that merits at least a second viewing to appreciate everything. I didn't find it quite as impressive as Le Corbeau , a film Clouzot made a few years earlier, or Les Diaboliques, which most people regard as his masterpiece, but it's definitely worth seeking out.

The story features Jenny, played by Clouzot's long-time companion Suzy Delair (still alive, I gather, at the splendid age of 100), who is a talented and sexy singer and a performer ambitious to get on in the world. She's married to Martineau (Bernard Blier), a quiet pianist who is driven to jealousy by her flirtatious ways. She cares for him, but is determined not to allow him to dominate her or wreck her prospects of fame.

A wealthy old lecher called Brignon takes a fancy to Jenny, in a scenario which, unfortunately, remains topical to this day. Martineau begs Jenny not to agree to see Brignon again, but she reckons she can take care of herself. He constructs an alibi at a theatre while following her to the place where he reckons she is due to meet Brignon, only to find that Brignon is dead. It seems clear that Jenny has killed him, and Martineau can't resist the temptation to interfere with the crime scene. Meanwhile, Jenny's friend Dora, a photographer who used to take nude pictures of Brignon's conquests, tries to help her out.

Louis Jouvet plays the detective who is soon on the trail. His performance is highly enjoyable, and overall this is a film which has earned the critics' admiration over the years. It has a depth, as well as a number of very pleasing touches, and it's probably one of those films that merits at least a second viewing to appreciate everything. I didn't find it quite as impressive as Le Corbeau , a film Clouzot made a few years earlier, or Les Diaboliques, which most people regard as his masterpiece, but it's definitely worth seeking out.

Published on April 25, 2018 04:52

April 23, 2018

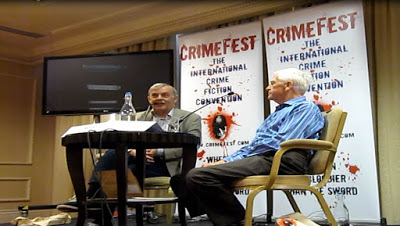

Peter Lovesey - Grand Master

At last year's CrimeFest, I had the easiest and most pleasurable of tasks, that of interviewing Peter Lovesey about his remarkable career, and a week ago, we had the chance to get together again during the CWA's annual conference, and the book-signing that followed it. (Peter is a former CWA Chair, and his continuing commitment to the CWA is something his fellow members greatly appreciate). Right now, he's in the US, and later this week at the Mystery Writers of America Edgars awards ceremony, he will be honoured as an MWA Grand Master.

The array of awards that Peter has received, over an astonishing span of almost half a century, is quite breathtaking. Right from the start, he made an impact on the genre, winning the Macmillan/Panther First Crime Novel prize for his debut Wobble to Death. He won the CWA Gold Dagger for that marvellous mystery The False Inspector Dew, and he's also picked up a couple of CWA Silver Daggers. He won the CWA Diamond Dagger in 2000, And there are many others. Take a look at the long list on his website.

His latest novel, Beau Death, is an excellent illustration of his versatility. There's a freshness of approach in his work, a refusal to be constrained by formula, that keeps his books as engaging today as when he first started writing. The quiet humour of his work is another important ingredient in his novels, and I should also say that he is unquestionably one of the finest short mystery writers to have emerged in the past fifty years. If you'd like to see the videos of my CrimeFest interview with Peter that Ali Karim kindly allowed me to post on my Youtube channel, take a look here.

But there's much more to Peter Lovesey than wonderful writing. His kindness and modesty are admired by those who know him. You have only to look at the many tributes paid to him by his fellow Detection Club members in Motives for Murder, the short story collection I edited in celebration of his 80th birthday eighteen months ago, to see that. I'm truly delighted that he's agreed to give a talk about his classic and contemporary crime fiction at Alibis in the Archives in June (and there are a few non-residential places still available if you're in the UK then). In the meantime, warmest congratulations on becoming a Grand Master, Peter. You are the worthiest of recipients.

Published on April 23, 2018 01:00

April 20, 2018

Forgotten Book - The Tin Tree

I've been musing recently on the impact that the First World War had on detective fiction, and among other things this led me to read The Tin Tree by James Quince, a book that's been on my TBR pile for a while now. Quince's pen-name masked the identity of J.R. Spittall, who signed my copy; he was a clergyman, and his career as a crime writer was quite brief, extending to a mere three novels.

The Tin Tree was the first, and it's a curious book. The opening scenes capture, very effectively in my opinion, the grim reality of soldiering during the First World War, as well as the eerie foggy environment surrounding the eponymous tin tree. The tree, built by the French army, was an observation post, with a ladder inside its trunk, and a platform "commanding an excellent view of the German lines".

The narrator of the story rejoices in the name of Roger Budockshed, although he's nicknamed, equally improbably, Secco - after Seccotine, which apparently is a brand of refined liquid fish glue. He is puzzled by a gunner called Rachelson, who is something of a mystery man. Eventually Rachelson confides in him, explaining that his real name is Montaubon, and that he's begun a new life after going on the run, following a murder in which he was the prime suspect.

It's an interesting set-up, but the story meanders quite a lot after that before reaching a twisty and pleasing climax that anticipates (in a sense) the plot-line of one of Agatha Christie's radio plays; both Quince's story and Christie's are based on the same classic precedent. The fact that the story sags in the middle is the mark of an inexperienced novelist, but Quince was a capable writer, and there is enough here to make it worth persevering, despite the longeurs.

The Tin Tree was the first, and it's a curious book. The opening scenes capture, very effectively in my opinion, the grim reality of soldiering during the First World War, as well as the eerie foggy environment surrounding the eponymous tin tree. The tree, built by the French army, was an observation post, with a ladder inside its trunk, and a platform "commanding an excellent view of the German lines".

The narrator of the story rejoices in the name of Roger Budockshed, although he's nicknamed, equally improbably, Secco - after Seccotine, which apparently is a brand of refined liquid fish glue. He is puzzled by a gunner called Rachelson, who is something of a mystery man. Eventually Rachelson confides in him, explaining that his real name is Montaubon, and that he's begun a new life after going on the run, following a murder in which he was the prime suspect.

It's an interesting set-up, but the story meanders quite a lot after that before reaching a twisty and pleasing climax that anticipates (in a sense) the plot-line of one of Agatha Christie's radio plays; both Quince's story and Christie's are based on the same classic precedent. The fact that the story sags in the middle is the mark of an inexperienced novelist, but Quince was a capable writer, and there is enough here to make it worth persevering, despite the longeurs.

Published on April 20, 2018 11:29

April 18, 2018

"Catch of the Day"

It's not often that my fiction appears in close proximity to that of the great Ben Okri (well, it's never happened before, if I'm honest), so you can imagine that I'm very happy to find my brand new short story appearing alongside one of his (and others by the likes of Sophie Hannah and Elly Griffiths). "Catch of the Day" is one of six stories to be found in Skald , an exciting and innovative collection produced by Audible.

The story behind my involvement with this collection is unusual. It goes back to March last year, when I took part in the Emirates Literature Festival in Dubai. Among other things, I was interviewed with Rob Davies about Golden Age fiction and the British Library Crime Classics. Ellah Wakatama Allfrey proved to be an excellent interviewer, and it all went swimmingly. And shortly after my trip to the Festival, I set off for Honolulu, for Left Coast Crime. Because Hawaii is so far away, it made sense to expand my stay there, and I spent a few days on each of three very attractive islands, Oahu, Kauai, and Maui.

I had in mind, as I always do on these trips, that I'd soak up the local atmosphere, and research the places I visited, in the hope that an idea for a work of fiction of some kind would come along. And so it did. In fact, quite a few possible plotlines hopped into my mind, and before long, I started to sketch out a mystery set on Kauai, an island which I found entrancing. I decided it should be a first person narrative, told by a local driver, as I'd picked up quite a bit of background colour from drivers I met.

Then, out of the blue, Ellah came back into my life with news of the Audible project, and a commission for a new story with a theme of "discovery". She liked the concept of "Catch of the Day", and this spurred me into action. I found her editorial input extremely valuable, and I'm pleased with the resultant story. The photos illustrating in the post were all taken in Kauai and all feature locations mentioned in the story - except for the photo at the end, taken at the Emirates Literature Festival interview.

I'm trying, as a crime writer, to develop my skills and to stretch in fresh directions. This seems to me to be the best way to try to enthuse an increasing number of readers. I've been publishing fiction for a long time, but you can always improve, and this is what I keep aiming to do. And it certainly helps when you have a good and sympathetic editor. I'll never be a Ben Okri, admittedly, but after years of striving, I do feel that my fiction is moving in a more exciting direction than ever before. More news on that front shortly, I hope!

Published on April 18, 2018 04:00

April 17, 2018

Roderic Jeffries R.I.P.

I've just been told that the crime writer Roderic Jeffries, who also wrote as Jeffrey Ashford and Peter Alding, died last year at the age of 90. He'd been living in Mallorca for over forty years, which perhaps explains not only why I've never come across him in person but also why his books have tended, in recent years, to be rather overlooked.

Jeffries was a prolific crime writer, as was his father, Bruce Graeme (whose real name was Graham Montague Jeffries). Graeme, a leading light in the Crime Writers' Association during its formative years, and a good friend of the CWA founder John Creasey, wrote a wide range of mysteries, but was best known as the creator of Blackshirt, a Robin Hood type of character, and Roderic wrote a number of Blackshirt novels himself in the Fifties and Sixties, as Roderic Graeme.

Roderic spent a few years in the legal profession, practising as a barrister, and this gave him material for some of his early crime novels from 1960 onwards. Many of his books appeared under the legendary Collins Crime Club imprint, which, like the Gollancz yellow dustjacket, was in the Sixties and for many years before a brand associated with reliable writers who were library favourites (not to mention stars such as Reginald Hill and Robert Barnard, both of whom were ten years younger than Roderic). More recently, his work has been published by Severn House, a company which has filled the gap left by the disappearance of the Crime Club and Gollancz imprints very effectively.

Mistakenly in Mallorca, which appeared in 1974, introduced Inspector Enrique Alvarez, who became a very long-running series character indeed. The only interview I've come across featuring Roderic is to be found here on the blog of J. Sydney Jones.

Jeffries was a prolific crime writer, as was his father, Bruce Graeme (whose real name was Graham Montague Jeffries). Graeme, a leading light in the Crime Writers' Association during its formative years, and a good friend of the CWA founder John Creasey, wrote a wide range of mysteries, but was best known as the creator of Blackshirt, a Robin Hood type of character, and Roderic wrote a number of Blackshirt novels himself in the Fifties and Sixties, as Roderic Graeme.

Roderic spent a few years in the legal profession, practising as a barrister, and this gave him material for some of his early crime novels from 1960 onwards. Many of his books appeared under the legendary Collins Crime Club imprint, which, like the Gollancz yellow dustjacket, was in the Sixties and for many years before a brand associated with reliable writers who were library favourites (not to mention stars such as Reginald Hill and Robert Barnard, both of whom were ten years younger than Roderic). More recently, his work has been published by Severn House, a company which has filled the gap left by the disappearance of the Crime Club and Gollancz imprints very effectively.

Mistakenly in Mallorca, which appeared in 1974, introduced Inspector Enrique Alvarez, who became a very long-running series character indeed. The only interview I've come across featuring Roderic is to be found here on the blog of J. Sydney Jones.

Published on April 17, 2018 01:00

April 16, 2018

Shrewsbury and the CWA conference

I've just returned from Shrewsbury after an exhilarating weekend. It was the CWA's annual conference, an event I've rarely missed over the past thirty years. The setting was lovely - the ancient town is crammed with history and interest, and the Lion Hotel, whose previous guests have included Darwin, de Quincey and Paganini, was a splendidly historic venue.

The speakers included the legendary investigative psychologist David Canter, author of the Gold Dagger-winning Criminal Shadows, who shared many insights about the pros and cons of offender profiling. A psychiatrist explored the way that her discipline can contribute to cutting edge fiction. A forensic expert cleverly updated us on latest forensic techniques, and how they might be used in solving The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. There were talks about Ellis Peters, and about marketing books in the modern age. A leading scientific advisor to government was the after dinner speaker. And there was much more besides...

Quite a bit of alcohol was quaffed, and we also had a visit to Tanners' ancient wine cellars, again fascinating and historic. A ghost tour around the town was followed by a trip to the castle and the amazing public library, where an extremely old building which once housed Shrewsbury School has been cleverly integrated into a modern facility. I've never seen a library like it. There was also a book-signing at Waterstones.

It was great fun to catch up with old friends and also to meet many of the CWA's newer members, such as playwright Derek Webb, novelists Stephen Norman and Jo Summers, and human rights campaigner Stephen Jakobi. Great credit goes to Cilla Masters for organising things with such verve, and to Dea Parkin for all her support work. As for the CWA's AGM, it was a well-attended forum for lively debate and some very good exchanges of ideas for the future. And the upshot is that I've been re-elected as Chair of the CWA for a further (and definitely, definitely final) twelve-month term. It's a great honour to lead such a thriving and fun organisation.

The speakers included the legendary investigative psychologist David Canter, author of the Gold Dagger-winning Criminal Shadows, who shared many insights about the pros and cons of offender profiling. A psychiatrist explored the way that her discipline can contribute to cutting edge fiction. A forensic expert cleverly updated us on latest forensic techniques, and how they might be used in solving The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. There were talks about Ellis Peters, and about marketing books in the modern age. A leading scientific advisor to government was the after dinner speaker. And there was much more besides...

Quite a bit of alcohol was quaffed, and we also had a visit to Tanners' ancient wine cellars, again fascinating and historic. A ghost tour around the town was followed by a trip to the castle and the amazing public library, where an extremely old building which once housed Shrewsbury School has been cleverly integrated into a modern facility. I've never seen a library like it. There was also a book-signing at Waterstones.

It was great fun to catch up with old friends and also to meet many of the CWA's newer members, such as playwright Derek Webb, novelists Stephen Norman and Jo Summers, and human rights campaigner Stephen Jakobi. Great credit goes to Cilla Masters for organising things with such verve, and to Dea Parkin for all her support work. As for the CWA's AGM, it was a well-attended forum for lively debate and some very good exchanges of ideas for the future. And the upshot is that I've been re-elected as Chair of the CWA for a further (and definitely, definitely final) twelve-month term. It's a great honour to lead such a thriving and fun organisation.

Published on April 16, 2018 09:00

April 13, 2018

Forgotten Book - Death Knocks Three Times

Lucy Malleson was an interesting and capable writer who enjoyed a good deal of success without ever, really "breaking through" into the literary big-time. After her death in 1973, her work quickly faded from view, but she'd had a long career, writing under a variety of pen-names: J. Kilmeny Keith, Anthony Gilbert, and Anne Meredith. The Gilbert name became the best-known, but last year I was delighted to write an introduction for her first Anne Meredith novel, Portrait of a Murderer, when it became the Christmas title for the British Library's Crime Classics series. The book did well- so well, in fact, that although the main focus was on the paperback edition, I gather that the hardback edition swiftly sold more copies than the original first edition! Who would have expected that?

I've read a few of the Anthony Gilbert titles over the years, and I've had mixed feelings about them. She was a capable writer, and she had the important strength of caring about her work which meant that she was not content to stick rigidly to a single storytelling formula. Her main protagonist, Arthur Crook, is a rascally solicitor, so you might think he has a particular appeal for me, but in truth I'm not much of a Crook fan. Sometimes he seems to get in the way of the story, and to me, it's no surprise that a good film made of one of her books,

All of which brings me to Death Knocks Three Times, a novel she published in 1949. The date is significant, because a key element of the story is the period setting: we really get a feel of life in post-war austerity Britain, although some of the political comments seem a bit delphic to a modern reader. The story begins, like others such as The Nine Tailors, with the detective hero - if one can call Crook a hero - stuck in the middle of a car journey due to bad weather, and taking refuge somewhere just before a mysterious sudden death occurs.

It's not quite clear whether murder has taken place (though the reader will suspect it has...) and the action then shifts to a sequence of poison pen letters, sent to a rather unpleasant elderly lady, who summons help from another woman, who is very nicely characterised and whose name is Frances Pettigrew (was Gilbert referencing Cyril Hare's Francis Pettigrew? Given the number of literary and specifically crime fiction allusions in the book, it is possible). Anyway, as the book title suggests, two more deaths fall to be considered, but an unusual air of mystery pervades the story. It's far from clear what is really going on until Crook comes up with an explanation - which, to be honest, I didn't find wholly satisfying, especially in relation to the first death.

This is a novel that has earned rave reviews from good judges such as John Norris. For my part, I admired Gilbert's ambition, and her attempt to do something different and unusual, but I felt that the narrative was too diffuse to be altogether successful, and Crook's muted role also felt rather unsatisfactory. An interesting book, though, and despite my reservations I'm glad I read it.

I've read a few of the Anthony Gilbert titles over the years, and I've had mixed feelings about them. She was a capable writer, and she had the important strength of caring about her work which meant that she was not content to stick rigidly to a single storytelling formula. Her main protagonist, Arthur Crook, is a rascally solicitor, so you might think he has a particular appeal for me, but in truth I'm not much of a Crook fan. Sometimes he seems to get in the way of the story, and to me, it's no surprise that a good film made of one of her books,

All of which brings me to Death Knocks Three Times, a novel she published in 1949. The date is significant, because a key element of the story is the period setting: we really get a feel of life in post-war austerity Britain, although some of the political comments seem a bit delphic to a modern reader. The story begins, like others such as The Nine Tailors, with the detective hero - if one can call Crook a hero - stuck in the middle of a car journey due to bad weather, and taking refuge somewhere just before a mysterious sudden death occurs.

It's not quite clear whether murder has taken place (though the reader will suspect it has...) and the action then shifts to a sequence of poison pen letters, sent to a rather unpleasant elderly lady, who summons help from another woman, who is very nicely characterised and whose name is Frances Pettigrew (was Gilbert referencing Cyril Hare's Francis Pettigrew? Given the number of literary and specifically crime fiction allusions in the book, it is possible). Anyway, as the book title suggests, two more deaths fall to be considered, but an unusual air of mystery pervades the story. It's far from clear what is really going on until Crook comes up with an explanation - which, to be honest, I didn't find wholly satisfying, especially in relation to the first death.

This is a novel that has earned rave reviews from good judges such as John Norris. For my part, I admired Gilbert's ambition, and her attempt to do something different and unusual, but I felt that the narrative was too diffuse to be altogether successful, and Crook's muted role also felt rather unsatisfactory. An interesting book, though, and despite my reservations I'm glad I read it.

Published on April 13, 2018 06:01