John Paul Davis's Blog: JPD's History Substack

April 23, 2024

Scenes from the road - Chartwell House and Gardens

Happy Tuesday, Substackers. I hope recent times have treated you well.

So, despite my best intentions to publish here at least weekly, juggling regular articles with my other commitments (writing and others) proved a step too far. Consequently, I’ve had to prioritise.

Though I still intend to post more history articles here in due course, for the time being, I’ll be mostly sharing photos from my recent trips. If spring lives up to its promise, I’m hopeful there will be many more, particularly to sites that allow me to make the most of my National Trust and English Heritage memberships. It’s possible that a few might also sneak their way into my next novel - but more on that another time!

Below are some scenes from my recent visit to Chartwell House and Gardens, Sir Winston Churchill’s home for over 40 years. It was here, in his beloved family home in rural Kent, that Churchill was inspired to produce some of his greatest works of art and literature - not to mention take refuge from the constant pressures of political life.

Highly recommended for any Churchillian or anyone who enjoys a lovely garden!

February 23, 2024

Done in by the State. Did Henry III's government assassinate three senior barons?

As an author of historical thrillers, political thrillers and historical nonfiction, I’m always excited when these subjects overlap. Surprisingly, this happens rather often. So much so that I currently have over twenty unwritten thrillers waiting to be completed!

Usually, such crossovers centre around some form of conspiracy. Some involve a missing link concerning the whereabouts of a lost treasure. Others, the reputed antics of a secret society - or, at the very least, a society with secrets. The most common, of course, is the oldest crime of them all - Murder! Or, when it comes to politics . . .

Assassination.

Recent happenings in the Arctic North have got me thinking. As long as there have been pretenders to the throne or conflicts of interest in politics, there have been dogsbodies on hand to do the dirty work. From Julius Caesar to JFK, there is no shortage of famous leaders cut down before their time. In England, the list of royals who met suspicious ends is astounding. William II, Edward II, Richard II and Henry VI all died in bizarre circumstances - and don’t even get me started on the Princes in the Tower! Thinking about the subject recently, I found myself drawn back to the reign of Henry III, on which I’ve written two major works. To lose one important magnate could be considered unfortunate. Two careless.

Three is just plain suspicious.

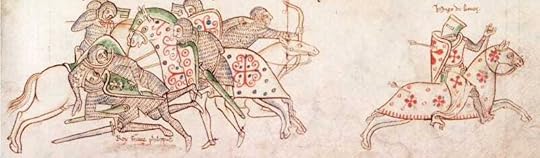

One prominent victim of possible foul play in Henry III’s reign was William Longspée, Earl of Salisbury. An illegitimate son of Henry II, Longspée was John’s half-brother and, hence, the young Henry III’s uncle. Famed for his naval antics at Damme in 1213, it has been alleged that John seduced William’s wife after the earl was captured in the aftermath of the Battle of Bouvines (below, Matthew Paris) in 1214, which may have influenced William’s decision to rebel in the First Barons’ War. Regardless of whether there was any truth in the rumours, Longspée later made peace with his young nephew and returned to a degree of influence.

On 23 March 1225, eight years after the war ended, Longspée joined his younger nephew Richard, the king’s brother and soon-to-be Earl of Cornwall, in setting sail with a sizeable fleet to Poitou to bring what remained of the Angevin Empire to submission. Although the sixteen-year-old Richard took nominal charge, Longspée undoubtedly controlled the expedition. As a reward for acting as Richard’s guardian, Longspée was granted wardship of the lands of the late earl of Norfolk.

Although things in Poitou went well for Richard, Longspée’s early success did not last. The earl contracted an illness on attempting his return to England, forcing him to take refuge on the island of Ré, just off the coast of La Rochelle. On returning home the following spring, he passed away at Salisbury Castle.

How the earl met his end has long been a point of contention. That his decline was of natural causes in direct connection to his earlier illness is possible. However, the chronicler of St Albans believed he may have been poisoned. The culprit in Roger of Wendover’s eyes was the king’s justiciar, Hubert de Burgh, a talented administrator who had climbed the greasy pole of politics under John before masterminding victory for Henry III at the Battle of Sandwich in 1217 (below, Matthew Paris).

Similar accusations would later be levelled at the justiciar following the death of William Marshal’s eldest son and namesake, William Marshal the Younger, 2nd Earl of Pembroke. Born in 1190, William excelled under King John’s care before acting as a surety for Magna Carta. Like Longspée, Marshal took up arms against John and found himself on the opposing side from his father, whom John had appointed Henry III’s regent on his deathbed. Despite their temporary estrangement, there remained much love between the two. After forewarning his son of an impending attack when staying at Worcester Castle, the pair met, ironically along with Longspée, at Knepp Castle before agreeing to take the king’s side. Two years after the war ended, William oversaw his father’s burial and commissioned the greatest knight’s excellent biography, L’Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal, a few years later.

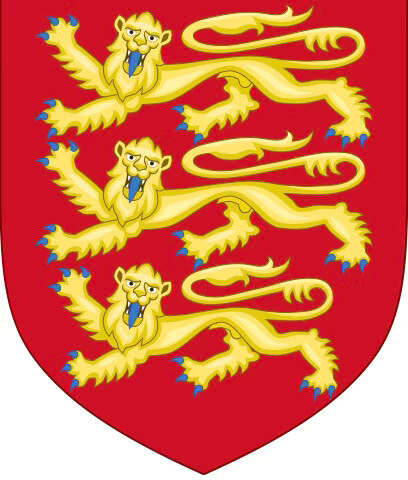

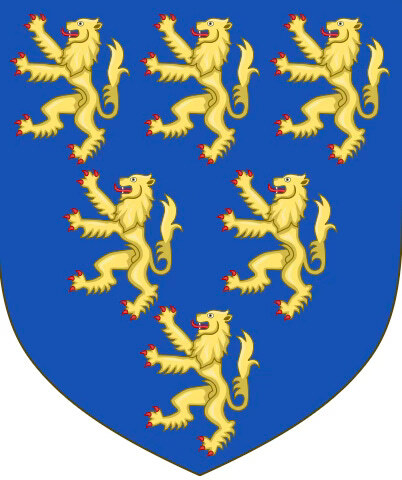

The Marshal Family Coat of Arms

The Marshal Family Coat of ArmsAlthough it is often difficult to establish the exact nature of medieval working relationships, Hubert and William the Younger appear to have enjoyed solid relations throughout the 1220s. When Henry III, acting on papal advice, demanded his castellans to surrender all royal castles in their control, Hubert cemented his ever-strengthening alliance with Marshal by formally granting him the castles at Cardigan and Carmarthen. Yet, by 1228, any early friendship appears to have been damaged beyond repair. When Henry III and the justiciar attempted to subdue the threat of Welsh rebellion, a lack of financial clout and baronial support left Hubert politically isolated. Complicating things further, William the Younger was now married to the king’s younger sister, Eleanor. For the next three years, relations between Hubert and Marshal remained awkward at best, not least after the justiciar took the blame for the king’s failed military excursion into France.

In April 1231, the plot thickened. Less than a fortnight after the highly anticipated wedding between the king’s brother, Richard, Earl of Cornwall, and William the Younger’s sister, Isabel - then Gilbert de Clare’s widow - William passed unexpectedly aged 41. What caused his death remains unclear. Later conjecture by Roger of Wendover’s famous successor as chronicler of St Albans, Matthew Paris, pointed the finger of blame squarely at Hubert de Burgh through poison.

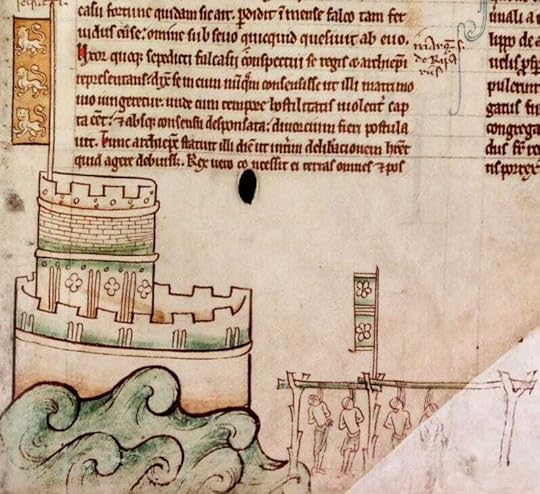

Another influential player in this bizarre intrigue was the Anglo-Norman soldier Falkes de Breauté. Another to endure a fraught relationship with the justiciar, Falkes’s antics throughout Henry III’s early reign were not entirely devoid of controversy. His refusal to return four manors pawned to him by the regent led to bitter relations with the younger Marshal. A similar dispute arose with Longspée over Lincoln Castle. As fate transpired, Falkes passed away in 1226, two years after being exiled to the continent following his refusal to surrender Bedford Castle, forcing Henry III to resort to siege (below, Matthew Paris). What caused Falkes’s death is another mystery. Writing on Falkes’s demise, Matthew Paris offered two clues. An account of him being found dead after retiring for the night was accompanied by an image of the devil feeding Falkes a fish.

So, what exactly happened to these three influential figures? Regarding Falkes de Breauté, the case against Hubert is flimsy. Although an accusation was made during Hubert’s trial in 1232 following his dismissal as justiciar, much of the noise appears to have been retrospective. No more convincing is the suggestion that Hubert had done similar to the late Archbishop of Canterbury, Richard le Grant, who died in Italy on his way home from Rome.

Regarding William Marshal the Younger, a motive is far more apparent. Not only was William the head of the baronage and married to the king’s younger sister, but his newfound friendship with his double brother-in-law Richard, Earl of Cornwall, was potentially detrimental to Hubert’s dwindling power. While a thirteenth-century man dropping dead at 41 wasn’t unheard of, it does appear to have come as a shock. Despite Wendover having made a similar allegation against the justiciar concerning Longspée, Paris was the only chronicler who made the claim of Marshal, who was interred alongside his father at Temple Church, London. The terrible photo below shows a cast copy of what is believed to be his effigy, then on loan to Temple Church from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

A cast copy of William Marshal the Younger’s effigy at Temple Church

A cast copy of William Marshal the Younger’s effigy at Temple ChurchConcerning the late earl of Salisbury, the murder case seems far stronger. True enough, Wendover was the only contemporary source to point the finger at Hubert. Yet interesting evidence would come to light in future years. When Longspée’s tomb was opened in 1791, those responsible were shocked to find the well-preserved corpse of a rat inside his skull. Traces of arsenic were also present in the rat.

Longspée’s tomb at Salisbury Cathedral

Longspée’s tomb at Salisbury CathedralThe question, of course, is why do it? While a motive for killing William Marshal the Younger was political, Hubert’s aggression towards Longspée was likely motivated more by personal embarrassment. During the period when the earl was thought lost at sea, Hubert’s nephew, Reymond, made the bonkers decision to propose marriage to the countess. Not only did Longspée soon turn up alive, but the young Reymond was no noble. When the enraged countess and earl personally took up their grievances with the justiciar, Hubert had no choice but to eat humble pie. Commenting on the matter, Wendover claimed that on apologising to the earl, Hubert ‘invited him to his table, where, it is said, he was secretly poisoned’ (Giles, Wendover, p. 468).

So, what really happened in the dark days of 1226-31? Did Hubert de Burgh really organise three separate murders? While the evidence is patchy, especially for Falkes and le Grant, the possibility that the earls of Salisbury and Pembroke died by dubious means cannot be ruled out. That Hubert was directly involved seems unlikely. Even less likely is that the famously cordial Henry III played any role. On learning of Marshal’s death, Henry furiously wept, ‘Woe, woe is me! Is not the blood of the blessed martyr Thomas fully avenged yet?’

The Martyrdom at Canterbury Cathedral, where St Thomas Becket was murdered

The Martyrdom at Canterbury Cathedral, where St Thomas Becket was murderedOf all the controversial deaths concerning a ruler’s chief political opponent, the murder of St Thomas Becket undoubtedly takes Alfred the Great’s burnt cake. That Longspée and Marshal were done away with somewhat Becket-style seems more possible, albeit impossible to prove. Even if the king was in the dark, the justiciar had plenty of loyal confidants capable of ridding him of turbulent magnates.

If history teaches us one thing, it is that those in positions of power often have faulty memories, especially regarding things that might incriminate them. At times like this, I find the words of two very different Americans particularly apt. Mark Twain once said, “History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.” Former US President Ronald Reagan more than once said, “I don’t recall!”

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

One final call of business. In my previous article, I wrote that I’d be relaxing my Substack schedule from twice a week to a weekly Tuesday. This being Friday, I’m aware I’ve already broken that.

See you next time the muse strikes!

February 13, 2024

From The Devil They Came: The Rise of the House of Plantagenet

The Plantagenets have been on my mind recently. Not that that’s particularly unusual. Being the devout medievalist that I am, barely a day goes by I don’t think of them. They say that men, in general, are that way inclined towards the Roman Empire. Again, I’d be lying if I said that wasn’t true of me either. Or the Templars, for that matter. Or Robin Hood. Or anything to do with the quest for the Holy Grail.

That I regard the Plantagenets worthy of so much attention is unlikely to prove controversial. The rulers of England from the accession of Henry II in 1154 to the death of Richard III at Bosworth Field in 1485, this unique dynasty contributed some of the best and worst kings in England’s history - not to mention some of the most powerful. Even today, many tangible reminders of their time on the throne can be found. And not just in England.

No doubt a greater rarity in my case is which Plantagenets have been on my mind. Contrary to my usual musings from Henry II to Henry V, my recent thoughts have centred more on their distant forebears - namely, the French ones. Many history lovers are at least somewhat aware that Henry II’s ‘Angevin’ Empire was spread across France; many also know that it came from no one source. Some of Henry II’s territories, of course, came courtesy of his wife, Eleanor, whose name will forever be inseparable from the Aquitaine region. Others will also recall that Henry II’s path to the throne was through his mother, Matilda, the eldest daughter of Henry I, the fourth son of William the Conqueror. Perhaps less famous are those who preceded Henry II’s father, Geoffrey V, count of Anjou, often dubbed the first Plantagenet because of the broom sprig he wore in his hat. Though his name remains somewhat revered, the antics of his Angevin forebears are shrouded in legend.

His marriage aside, how Henry II (pictured above, Matthew Paris, Historia Anglorum, British Library Royal 14 C. VII, f.9) came to inherit and acquire such vast swathes of land is worthy of investigation. Indicative of the name, the Angevin Empire originated in Anjou, the so-called Garden of France, which included the Loire Valley and its capital at Angers. While much of Henry II’s birthright, notably England and Normandy, came from his mother, Matilda being Henry I’s heir following William Adelin’s demise onboard the White Ship in 1120, on his father’s side, Henry was also descended from the original counts of Anjou (arms pictured below), who had dominated the county since at least the tenth century.

For Henry II’s contemporaries, the identity of his grandparents was highly significant. Contemporary chroniclers were well aware that Edward the Confessor had prophecised that the green tree of England would once again flourish when the split parts of the trunk were rejoined, something Henry’s accession appeared to satisfy. Further to being a direct descendant of William the Conqueror and the counts of Anjou, Henry was the grandson of Matilda of Scotland, Henry I’s first wife. Through this line, Henry II was the first descendant of Alfred the Great to occupy the throne of England since the Norman Conquest. Equally well aware of this, Henry went to great lengths to promote this part of his lineage, leading to Edward’s canonisation and translation to Westminster Abbey in 1163.

While Henry II’s path to the throne of England hinged more urgently on his more recent ancestors and their role in bringing about and subsequently ending the Anarchy, it was mainly thanks to the original counts of Anjou as previously unknown castellans that enabled him to acquire such remarkable wealth. There are several legends of the origins of the house. First to emerge from the mists of obscurity is Ingelgar, a legendary soldier of fortune. Following Ingelgar was his son, Fulk the Red, who ruled Anjou from around AD 908 until 942. Following him was Fulk the Good, count from 942 until 960. So fragmented was tenth-century France that the title came close to rivalling that of the king.

Over the coming two centuries, the success of Ingelgar’s descendants gave rise to a host of colourful legends. Among them was Geoffrey Greygown, count of Anjou 960-987, who reputedly single-handedly slew a giant. Worthy of similar fame was the influential eleventh-century warlord and pilgrim, Fulk III (Nerra: the black), who apparently achieved victory over the count of Brittany by preventing his army’s retreat with a ‘gale sweeping corn’. Future namesakes would be less worthy of praise. The English chronicler and Benedictine monk, Orderic Vitalis, described Fulk IV as a man of many ‘reprehensible, even scandalous, habits’. The above image shows him making terms with Philip I before defeating his brother Geoffrey and imprisoning him (Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis, British Library Royal 16 G. VI).

By 1131, the rule of the giant slayer’s descendants had reached previously unthinkable heights. So well established was the House of Ingelgar in Anjou that the respected Fulk V (above) was chosen to replace Baldwin II as King of Jerusalem after marrying Baldwin’s daughter, Melisende. With this, the way was clear for Fulk’s son, Geoffrey the Fair (below, courtesy of an enamel effigy on his tomb in Le Mans Cathedral), to rule Anjou. Under Geoffrey, the Garden of France flourished, and his territories expanded. On marrying Matilda in 1128, Geoffrey set his sights on his new wife’s birthright. As Henry I’s heir, Matilda’s claim to England and Normandy was unbroken to William the Conqueror, who had been invested Duke of Normandy in 1035 and crowned King of England in 1066. Though a number of the Anglo-Norman barons reneged on their oaths to Matilda and declared Stephen of Blois king following Henry I’s death, news of Stephen’s rushed accession placed Geoffrey and Matilda on a path to war with the new king in England and Normandy. By 1144, Angevin control of Normandy was almost absolute, ending nine years of conflict and leaving England in a state of civil war.

Further to achieving control of western England, Geoffrey’s investiture as Duke of Normandy and inheriting Anjou ensured approximately half the future Anglo-Norman dominions were already safely under his command. When his ambitious son, Henry, faced Stephen at Wallingford in 1153, the end to the nineteen-year-winter was in sight. Though the crown of England eluded Geoffrey, partly due to his wife’s insistence, better luck would befall the prince. Henry II was crowned on 19 December 1154, less than two months following Stephen’s death.

As a ruler and a man, Henry II had much in common with his Angevin forebears. Tall and handsome, he shared his father’s strength of mind and body. A combination of his red hair and fiery personality earned him the label ‘the little fox’, which also tallied with a passage in the Song of Solomon. Of that fiery personality, Henry was particularly proud. In conversation with his court confessor, the little fox is recorded as having remarked, ‘And why not, when God himself is capable of such anger?’ A gifted administrator and military tactician, Henry followed his father’s example of being extra prudent when choosing a wife. Though Eleanor was nine years Henry’s senior, the marriage brought him significant assets, notably Aquitaine, not to mention a substantial brood that included Henry the Young King, Richard the Lionheart and King John (pictured below, British Library, Royal 14 B VI: from left to right, William, Henry, Richard, Matilda, Geoffrey, Eleanor, Joan, John).

With Eleanor by Henry’s side, the House of Plantagenet’s rule over the ever-developing empire would reach its zenith. From the legendary antics of the self-made Ingelgar to Geoffrey of Anjou’s conquest of Normandy, Henry II’s territories stretched from the borders of Scotland to the Pyrenees. Never before had such large swathes of England and France known one overlord. Indeed, their rise was so unprecedented that the fact that it was even possible raised several questions. The contemporary chronicler Gerald of Wales conjectured that the Plantagenets’ success had only been possible as the unholy consequence of one of the early counts of Anjou being seduced into marriage by the Devil’s daughter, who later flew screaming out of a window on being forced to take Holy Communion. Gerald’s contemporary Richard I took great satisfaction in such tales, stating: ‘What wonder if we lack the natural affections of mankind – we come from the Devil, and must needs go back to the Devil.’ On their origins and fate, the legendary crusader Bernard of Clairvaux was in similarly little doubt:

‘From the Devil they came and to the Devil they will return.’

Two more quick orders of business. After a couple of months of publishing twice a week, I have relaxed my schedule to a weekly Tuesday. Though my commitment to being a full-time thriller writer held considerable sway in my decision, a recurring trend I encountered in recent feedback is that most of you enjoy hearing from me often but not too often. I choose to take this as a compliment!

Finally, in the words of the great Danny John-Jules in the hit 90s TV show Maid Marian and Her Merry Men. It’s Pancake Day. Yes, it’s Pancake Day. Yes, it’s Pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pancake day!

Have a great week.

Some of the above stories were included in my book, King John, Henry III and England’s Lost Civil War, published by Pen&Sword History.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

February 6, 2024

Sir Roland ap Rhys and the Barbary Ape

Completing the trio of Carew Castle’s tales of larger-than-life owners is one of Sir John Perrot’s successors. On the Elizabethan courtier’s death, Carew passed to the Crown before the de Carews repurchased it in 1607 and refortified it for the Civil War. In the latter years of James I’s reign, the de Carews leased the castle to a character of particular ill repute: Sir Roland ap Rhys – alternatively Sir Rowland Rees – a famed sailor and privateer.

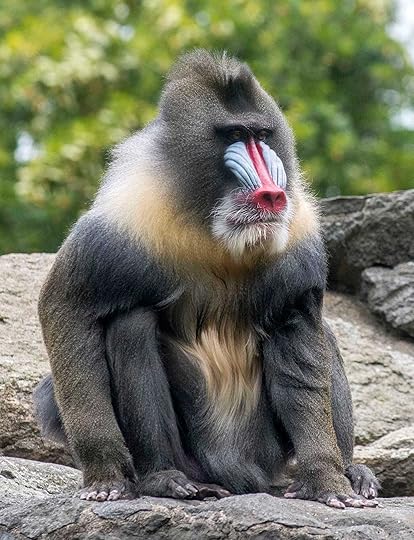

Sir Roland’s legend is famous in these parts. At some point in his tenure, his fiery personality caused a bitter, long-lasting feud with his eldest son, who fell in love with a lowly Flemish merchant’s daughter. On banishing his son, Rhys lived a lonely life at the castle with his pet ape, Satan, acquired on one of his voyages to the Barbary Coast - other accounts say from the wreck of a Spanish galleon. Based on the limited information that survives, it is likely that the beast was a mandrill (below, source: Wikipedia).

During his long, drunken bouts of isolation, the deranged despot’s behaviour became more erratic. When friends and associates visited the castle, the strange pet was often the centre of entertainment, quickly learning to imitate the visitor. At times, the drunken sailor would cry out for his beloved son; the next, he would curse him to hell. Consequently, most stayed away from the castle, knowing they would be the victims of Rhys’s mood and the ape’s devilish pranks.

As Sir Roland’s bitterness reached a fever pitch, the feud with his son culminated in an inevitable tragedy. In addition to his anger towards his son, he held a similar grudge against his son’s new love, accusing her of bewitching him. Complicating the matter, her father, Horowitz, was a tenant of Sir Roland. One cold, fateful night, the Flemish merchant visited the castle to pay his rent. Worse luck, trade had been poor that winter and the merchant was short. On arriving at the rainswept castle, Sir Roland slated Horowitz and mocked his daughter. In the resulting scuffle, the sailor blew his whistle and unleashed the ape.

The merchant was fortunate to escape, leaving Rhys a ruined mess. As he sought to leave for home, a kindly servant invited him to stay for a warm meal as the weather remained treacherous. As they engaged in conversation, Sir Roland’s piercing whistle again reverberated throughout the castle, after which the sounds of further struggle intensified. On entering Rhys’s chambers, the servant and merchant witnessed the pirate dead on the floor, his throat slit, and the ape’s head burning in the fire.

A sickly grin frozen on its face.

Precisely what transpired that night has never been clear. That Sir Roland set the ape on himself in an apparent suicide mission is plausible. If so, what killed the ape? Did the strange creature accidentally burn itself in the fire, perhaps the victim of Sir Roland’s drunken reflexes? Did Sir Roland accidentally kill his pet and commit suicide in instant remorse? Alternatively, did the merchant, and maybe the servant, set upon the pirate and his unique pet and concoct the story to evade suspicion - and rent?

Whatever the cause, the master and ape appear to have perished. Local legend tells that loud footsteps have been heard throughout Sir Roland’s otherwise empty chamber in the northwest tower. The same is true of hysterical laughter and blood-curdling screams. Incredibly, the ape’s ghost has been reported roaming the tower’s battlements. Others claim to have witnessed its head in the long-abandoned fireplace (below). The tale was included in Robert Hardy’s Castle Ghosts of Wales in 1994, which remains an entertaining watch.

Of all the reputed apparitions concerning the castles of Wales, I can think of none quite so bizarre.

Till next time.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The story of Sir Roland ap Rhys appears in my book, Castles of Wales, published by Pen&Sword History. For more on my books, thrillers and nonfiction, check out my official website www.officiallyjpd.com

Thank you for reading JPD’s History Substack. This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 2, 2024

Thoughts so far . . .

So, a couple of months in, I wanted to take a moment to thank you all for subscribing. I’m still working my way around the place, but early experiences of Substack have been a lot of fun. I’ve learned a lot of exciting things and encountered many interesting people - for the most part, that’s meant as a compliment!

Thus far, I’ve focused mainly on medieval history. Further to being my great passion, everything covered has been fresh in my mind and relevant to my recent books. Based on the feedback, most have gone down pretty well, especially the posts on Owain Glyndŵr and the Honours of Gwynedd. A huge thank you to all who have liked, commented, restacked or shared - it’s hugely appreciated. If you haven’t, it’s never too late.

Other than spending far too much time here, my focus this month has been writing and researching White Hart 6. White Hart 5, The Lost Crowns, has made a solid start and already approaching 50 ratings. A huge thank you if you’ve read it and rated it. Due to White Hart confidentiality rules, I’m unable to go into detail about WIPs; however, suffice it to say, it’s going well and is a lot of fun to research. My one clue is it involves the reign of Edward III. I’ll reveal more when Mike Hansen, Kit Masterson and co let me - the jackasses!

Writing aside, I spent part of January in Malta. Being a massive lover of religious history, crusader history, medieval and early modern history, the sun and zero crowds, it was the perfect place to go. Looking back, I’m not sure why it took me so long. The Co-Cathedral of St John is possibly the most majestic church I’ve ever seen. The gilded vault and frescoed ceiling have echoes of the Sistine Chapel. The floor comprises tombstones honouring more than 400 Knights of St John (see below).

The forts of St Elmo and St Angelo (above) are also must-sees for anyone interested in the Knights. Being the massive Templar and Hospitaller fanatic I am, these places were my Disneyland. I plan to write about them in due course. The ancient capital of Mdina also threw up some excellent surprises, not least St Paul’s Grotto (below), where tradition states the famous apostle spent three months in A.D. 60. Due to the restrictions on email size, I can only include a handful of photos. Among them, here’s one of me with a long-lost ancestor!

Thanks again for signing up and joining me on this journey. Apologies if any of these emails land in the junk. I’ve been slow to learn that too many large photos and Amazon links are a magnet for the email dementors, so I’ll be leaving the links out from now on.

If you have any questions, feel free to shoot. Likewise, if there are any subjects you think would make interesting articles, feel free to leave a comment.

Thanks for reading. January is over. It’ll be Christmas soon!

JPD x

P.S. If you’re new to JPD’s History Substack, below is a round-up of all the articles so far. You can find links to them in the archive section https://jpdavis9.substack.com/archive

Sir John Perrot: The Rise and Fall of Henry VIII's Alleged Bastard

Tales From The Tower: Samuel Pepys's Treasure Hunt

Strange Stories From The Chronicles: Mock Suns, Red Rainbows and Bloody Rain

Strange Stories From The Chronicles: Blood-Red Eclipses and The Five Moons Over York

The Dolgellau Chalice

The Mystery of the Welsh Crown Jewels

The Mystery of Owain Glyndŵr's Final Days

Tales from the Tower: The Rise and Fall of Ranulf Flambard

Tales from the Tower: The unkindness of Ravens and the 'Wailing Monk' of Caen

The Real Game of Thrones?

A Scandalous 12th-century Christmas at Carew

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Start writing today. Use the button below to create your Substack and connect your publication with JPD’s History Substack

January 30, 2024

Sir John Perrot: The Rise and Fall of Henry VIII's Alleged Bastard

In my first Substack article, I retold the story of the Norman castellan Gerald de Windsor and his wife, Princess Nest ferch Rhys, who was abducted from her home at Carew Castle - others claim Cilgerran - by her cousin and lover, Prince Owain ap Cadwgan. On being released from captivity two years later, Nest returned to Carew and resumed her life with Gerald.

According to some, she never left.

Owners of political importance were by no means absent from Carew’s later history. Of particular note was the Elizabethan courtier Sir John Perrot (pictured below), who became the castle’s owner in 1558. According to most history books, Sir John was the son of one Thomas Perrot and his wife Mary Berkeley, famously a mistress of Henry VIII. Though Thomas raised the lad as his own, John was conjectured to have been the king’s bastard.

Born a stone’s throw from Haverfordwest in South Wales between 7 and 11 November 1528, the young John first appeared on the scene when Henry VIII was negotiating his divorce from Catherine of Aragon. On joining the household of William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester, Perrot was introduced to the king and was knighted at Edward VI’s coronation. Edward appointed him High Sheriff of Pembrokeshire in 1551 before Perrot impressed Henry II of France when part of the party charged with arranging Edward’s betrothal to the French king’s daughter Elisabeth of Valois. After suffering incarceration in the Fleet under Mary Tudor for sheltering heretics, Elizabeth I entrusted him control of South Wales’s naval defences. In 1570, he reluctantly accepted the new post of Lord President of Munster and faced down the Desmond Rebellions before resigning in July 1573.

Free from the inconvenience of government and aided by his father’s business prowess in Wales, Perrot returned to Carew, aspiring to lead a ‘countryman’s life and keep out of debt’. Over the next five years, he oversaw many improvements at the castle, most notably the north range (above), which housed several domestic rooms, including a Long Gallery. He also rerouted several roads and moved the village to improve the views (below).

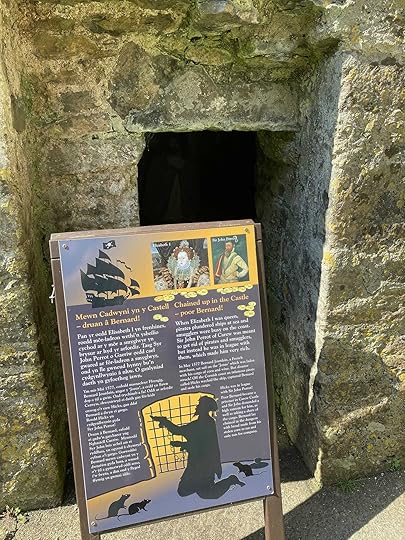

An interesting insight into his time there came in May 1577, when Perrot imprisoned one Bernard Jourdain for waylaying a French merchant ship off the Cornish coast in league with an infamous pirate named Hicks. However, rather than mete out justice, Perrot chained the apparent wrecker up in the castle dungeons (the entrance can be seen below) until he received a ransom and a share of the cargo.

Despite his questionable character and temperament, Perrot’s influence at Elizabeth’s court was still to peak. To crown his astounding rise, the queen appointed him Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1584. That Elizabeth should have made such an appointment is intriguing. Even more so is Perrot’s apparently careless remark in response to her change of mood to him in an audience that ‘now she is ready to piss herself for fear of the Spaniard, I am once again one of her white boys’.

Irrespective of Elizabeth’s reasons for appointing him, the arrogant rogue was not without enemies. News of his loose tongue, coupled with the embellishment of his plans for Ireland, culminated with the queen recalling him around the coming of the Spanish Armada and sending him to the Tower of London the following year on charges of treason. On being tried in 1591, he was found guilty despite the lack of definitive evidence. That he spoke further ill of Elizabeth is certain. Nor did he deny at his trial having uttered the words, ‘Stick not so much upon Her Majesty’s letter, she may command what she will, but we will do what we list… Ah, silly woman, now she shall not curb me, she shall not rule me now… God’s wounds, this it is to serve a base bastard pissing kitchen woman, if I had served any prince in Christendom I have not been so dealt withal’. Despite his blatant rudeness, Elizabeth appears to have sympathised with Perrot’s view that the guilty verdict was politically motivated. Further to labelling the jury ‘knaves’, the queen apparently showed unwillingness to sign the death warrant.

As fate had it, Perrot did not die of the axe but from seemingly natural causes, not three months after the verdict was delivered. A short time earlier, the same fate had befallen one of his officers, Sir Thomas Williams, also in the Tower. Incredibly, Williams had not been the first. Also in Perrot’s number was Sir Thomas Fitzherbert, who had been transferred there in January 1591 under strict orders that he remain in solitary confinement. Despite being allowed the freedom of the Tower, he perished three days before Perrot’s funeral. A fourth, Sir Nicholas White, fared little better, dying in 1593. Perrot’s body was interred in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula (below), where it lies to this day, close to the headless remains of Anne Boleyn.

Exactly how this luckless quartet met their respective ends is another enigmatic riddle for which the Tower has become famous. Officially, all succumbed to the same fate as Henry VI – of pure displeasure and melancholy – yet it seems highly suspicious that four seemingly strong and healthy men could all die inside the Tower of broken hearts. Were they murdered? Committed suicide? Succumbed to illness? Sadly, we will never know.

Equally likely to remain a mystery is Perrot’s true origins. Was he really the son of Henry VIII, or was it mere conjecture? Artistic representations certainly imply that he resembled the marriage-loving king in many ways. A handsome man with a muscular, imposing presence, he also shared much of the king’s temperament. During his time in Munster, Perrot authorised more than 800 hangings. He also fathered several illegitimate children and married more than once; however, fortunately, he avoided divorcing or beheading either of them!

Yet, despite seemingly fitting the profile, the suggestion is suspicious. True, Henry VIII’s enjoyment of Mary Berkeley is well known. Equally valid, Henry fathered several children out of wedlock, Henry Fitzroy perhaps the most famous. However, the main gossip in Perrot’s case came courtesy of Sir Robert Naunton, who later married Perrot’s granddaughter, Penelope, and never knew him personally. Naunton recorded in his own words:

on his return to the town after his trial, he said, with oaths and with fury, to the Lieutenant, Sir Owen Hopton, “What! will the Queen suffer her brother to be offered up as a sacrifice to the envy of my flattering adversaries?” Which being made known to the Queen, and somewhat enforced, she refused to sign it, and swore he should not die, for he was an honest and faithful man. And surely, though not altogether to set our rest and faith upon tradition and old reports, as that Sir Thomas Perrot, his father, was a gentleman of the Privy Chamber, and in the Court married to a lady of great honour, which are presumptions in some implications; but, if we go a little further and compare his pictures, his qualities, gesture, and voice, with that of the King, which memory retains yet amongst us, they will plead strongly that he was a surreptitious child of the blood royal.

Was Elizabeth I aware of, or at least open to, the possibility that Perrot was her half-brother? While it may explain elements of his rise, no official acknowledgement is known to have occurred. Furthermore, when Perrot was found guilty of treason, eighteen months had passed since Hopton had left his post as Lieutenant of the Tower, which raises questions over in what capacity Hopton overheard Perrot’s downhearted remarks. Incidentally, Sir John was Mary Berkeley’s third child, and Berkeley appears to have been geographically removed from the king at the likely time of conception.

Though Perrot was likely not Henry VIII’s son, a wry thought emerges that if the stories were true and Henry VIII had followed in John of Gaunt’s footsteps and married his mistress, Perrot could have reigned as John II. In that event, Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour would never have been queen, and Edward VI and Elizabeth I would never have been born.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The story of the enigmatic Sir John Perrot features in my book, A Hidden History of the Tower of London - England’s Most Notorious Prisoners, published by Pen&Sword History

Thank you for reading JPD’s History Substack. This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 26, 2024

Tales From The Tower: Samuel Pepys's Treasure Hunt

Sir Henry Vane, the younger, was executed on 14 June 1662 on Tower Hill. A leading parliamentarian during the interregnum, Vane later fell out with Cromwell over their differing visions and found himself out in the cold after the Lord Protector dissolved the Rump Parliament in 1653. Despite having played no role in the late Charles I’s execution, come the restoration of the monarchy, Vane’s continued fight for reform made him too dangerous a man for the new king to let live.

In attendance at Vane’s grisly end was Samuel Pepys (above), who commented positively on the late politician’s bravery and conduct. At the time, the soon-to-be famed diarist was enjoying a stellar career in the English civil service, working primarily for the naval officer Lord Montagu, created Earl of Sandwich shortly after Charles II’s ascension. A regular visitor to the Tower, Pepys returned four months after Vane’s beheading on Montagu’s orders to investigate a bizarre story involving the previous lieutenant of the Tower, Sir John Barkstead (below). According to rumour among the London underworld, Barkstead had amassed potentially £7,000 in gold coins, which he buried within the walls before fleeing to Germany. How the late colonel had managed this is unclear. Word at the time suggested he had made a nice earning from extorting the Royalist prisoners before stowing away the proceeds in wooden barrels.

So began one of the Tower’s truly unique tales. Inclined to believe the story to be in keeping with Barkstead’s maverick personality, Sandwich sought the king’s permission to conduct a search, which was subsequently delegated to Pepys. Around the end of October 1662, Pepys arrived at the lieutenant’s lodgings, now the King’s House, and presented himself to its famed governor Sir John (Jack) Robinson - later lord mayor of London. Joining Pepys were a Mr Wade and Captain Evett, who circulated the original treasure story on hearing it from one Mary Barkstead, who claimed to be the late colonel’s wife.

Despite their apparent ignorance over the treasure’s exact hiding place, Mary Barkstead’s referring to a ‘cellar’ within or near the King’s House (as seen below from across Tower Green) led Pepys to an obvious conclusion. The Bell Tower, which dates from the reign of Richard I, adjoins the building and famously includes the same cell in which Sir Thomas More had been incarcerated over a century earlier. No sooner could Pepys say Jack Robinson (kudos to anyone who gets that joke!) did they start to dig.

A disappointing first day was followed by a second. Having become increasingly frustrated at the lack of leads, Pepys adjourned the digging to formulate a more thorough plan. After speaking to Wade and Evett in greater depth, they promised to bring Mary Barkstead to the next session. On 7 November, a third attempt began with the colonel’s alleged widow in their company. Despite her best efforts to remember what her late husband had shown her, the treasure remained unfound, and they left the Bell Tower (as seen below from Water Lane) dejected.

A month passed before a visit from Evett and Wade convinced Pepys to try again. On thinking the matter over, Mary Barkstead concluded that the barrels were actually buried in the garden outside the Bloody Tower - originally known as the Garden Tower (below and to the left). Undeterred by the cold December weather, Pepys gave the green light to a final search. Sadly for all concerned, the result remained the same, and the project was finally abandoned.

So, what are we to conclude? Did the treasure ever exist? Was it found? Does it remain buried? As former Yeoman Warder Geoff (Bud) Abbott concluded, perhaps under a nearby car park? Could somebody have moved the barrels? Was Mary Barkstead cursed by the limitations of a faulty memory? Did the late colonel hoodwink her?

Despite the lack of definitive evidence for the treasure’s existence, the story is not without foundation. Further to the plausibility that the former lieutenant had spent much of the Civil War extorting Royalist prisoners, Barkstead is recorded as having served as a goldsmith in the Strand at the outbreak of the war, which may lend some credence to the possibility of the amassed coins’ existence. The exact value is also subject to some debate. According to the National Archives currency converter, £7,000 could equate to approximately £750,000 in the modern day; however, this discounts its potential historical value. Back then, £7,000 would have been enough to purchase more than a thousand horses, 9,000 sheep, or 10,000 days of trade labour. Not exactly small change.

As fate had it, prior to the treasure hunt, Barkstead had endured a final return to the Tower. He was hanged, drawn and quartered on 19 April 1662, along with two others, for their role in the execution of Charles I. His body was interred, and his head spiked above St Thomas’s Tower (above).

His secrets accompanied him to the grave.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The story of Pepys and his fruitless treasure hunt features in my book, A Hidden History of the Tower of London - England’s Most Notorious Prisoners, published by Pen&Sword History

Thank you for reading JPD’s History Substack. This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 24, 2024

Strange Stories From The Chronicles: Mock Suns, Red Rainbows and Bloody Rain

Further to the stories of blood-red eclipses and multiple moons, as discussed in my last article, the medieval era was chock full of other bizarre sightings. Among the most alluring was one sometimes regarded as a sister of ‘Moondogs’, the far more angelic ‘Sundogs’ (see below, source: Wikipedia).

An example of ‘Sundogs’ may have occurred in England on 8 April 1233. The prominent chronicler of St Albans, Matthew Paris (below), wrote of a strange halo appearing at sunrise and lasting until noon. Intriguingly, a similar occurrence was noted in the Annales Prioratus de Wigornia - the Annals of Worcester. According to the Worcester Annalist, around an hour after the disappearance of that recorded by Paris, people on the borders of Herefordshire and Worcestershire were treated to the sight of a bright semi-circle accompanying an identical halo on either side of the sun. Also present were four red suns and a fifth of the colour of crystal.

Though it’s impossible to know for sure, the chroniclers’ descriptions seem a dead ringer for ‘Sundogs’, also known as Parhelia. Parhelia is an atmospheric condition not dissimilar to ‘Moondogs’ that causes the illusion of one or more bright spots on either side of the sun. Perhaps understandably, the annalist of Worcester viewed the appearance of mock suns and beautiful halos with feelings of hope, not least as the ‘wonderful sight’ happened on Good Friday.

Twenty-one years before this apparent Easter miracle, a bright rainbow was apparently witnessed over the village of Chalgrave in Bedfordshire. In contrast to the typical rainbow, the seven usual hues on this particular April day were blood red. Although such sights are similarly rare, what the chronicler of Dunstable described was almost certainly that of a ‘monochrome rainbow’ (pictured below, source: Wikipedia). Such rainbows occur only when the sun is low, such as sunrise or sunset. Needless to say, the annalist perceived the blood-red arc as a sign of impending doom.

No less concerning to the people of France in 1212 was a shower of blood witnessed on 10 July at Caen in Normandy. Red rain, or blood rain, is more common than ‘Sundogs’ and ‘monochrome rainbows’. Indeed, tales of blood falling as rain go back to Homer’s Iliad in the 8th century BC. The French chronicler Gregory of Tours wrote of such an event over Paris in 582 AD. Likewise, the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth described something similar in his homeland in the 9th century. When blood rain fell over Château Gaillard in Normandy in 1198, the English Augustinian canon William of Newburgh viewed the miraculous sight as emblematic of Richard the Lionheart’s tenacity.

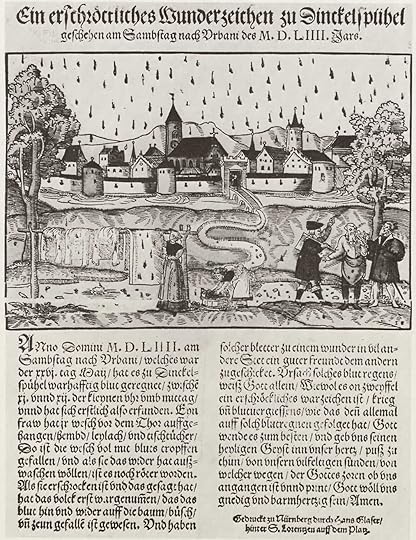

What causes blood rain is still debated. When the German printer Hans Glaser depicted a red shower over the city of Dinkelsbühl in modern-day Bavaria in 1554 (see below), the prevailing mood remained superstition over natural causes. More recently, the Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology (1992) concluded the colour was due to water mixed with dust containing iron oxide. Aerial spores have also been suggested as a possible cause.

Regardless of the strange phenomena’s exact cause, for the people of 13th-century England and France, stories of blood rain understandably aroused feelings of great uncertainty. The fact that the shower at Caen coincided with the alleged apparition of three crosses warring in the sky above Falaise, where John’s nephew, the missing Prince Arthur, had been imprisoned, only furthered the general feeling that trouble was imminent.

As the following months confirmed, 1212 offered no shortage of challenges. As France reeled from the failure of the so-called Children’s Crusade – a bizarre and seemingly spontaneous movement among French youths, which culminated in many being captured by slave traders and sold to the Egyptians – John’s navy wreaked havoc along the Normandy coast before laying waste to the towns of Fécamp and Dieppe. Though John celebrated the excursions’ success, capitulation at Bouvines two years later saw the tide turn. As the eminent Sir J. C. Holt wrote in his celebrated 1961 work, The Northerners, ‘the road from Bouvines to Runnymede was direct, short, and unavoidable’.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The above stories were included in my book, King John, Henry III and England’s Lost Civil War, published by Pen&Sword History.

Thank you for reading JPD’s History Substack. This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 19, 2024

Strange Stories From The Chronicles: Blood-Red Eclipses and The Five Moons Over York

Since beginning my journey as a writer more than fifteen years ago, life has taken me to many memorable locations and introduced me to some truly intriguing subjects. Among the great perks is researching historical manuscripts, notably medieval chronicles. Even now, it’s a process I thoroughly enjoy. Only through the eyes of the literary monk have I found it possible even to begin to understand the workings of the medieval mind.

Though most medieval chronicles possess certain consistencies, no two are identical. Some cover matters of great importance: legendary battles, coronations, the visits of esteemed dignitaries and so forth. Others are more mundane, focusing on local issues, such as feast days, minor squabbles or the implementation of canon law.

Then there are those that are just plain bonkers - quite literally out of this world. From the stories of green children or wild men in Suffolk, blood raining down from angry skies, strange lights in the dead of night or whirlpools swallowing King John’s washed-up treasure, few things rival the commentary of the rambling cleric.

Two particularly memorable examples concern the early reign of King John. A three-hour eclipse of the moon was reported to have made it shine blood red and emit rays like fire on 3 January 1200. For December of that year, the annalist of Burton and the prominent chronicler of St Albans, Roger of Wendover, echoed the musings of the Yorkshire chronicler Roger of Howden that five moons were spotted in the skies above the province of York. While four appeared at each point of the compass, a fifth, accompanied by several stars, began in the centre of the four before making a circuit of each one. After an hour of wowing the astounded eyewitnesses, the additional moons vanished without a trace.

What are we to conclude from such matters? Were the people of Yorkshire witnesses to uncommon astrological activity? A meteor shower? Multiple eclipses? The effects of lousy mead? Too much mead? Not enough mead? Too much water (h20 was often rich in bacteria back then and should be avoided like the plague!). Were they witnessing genuine UFO behaviour? Acts of God? Portents of genuine doom?

Or is there a more down-to-earth explanation?

Regarding the blood-red eclipse, the likely answer is straightforward. The moon will often turn red during a lunar eclipse due to how the sun’s light hits our atmosphere (see below, source: Wikipedia). Likewise, the fiery rays were almost certainly the usual sun’s rays passing through our atmosphere. Even in John’s reign, such a sight was relatively common, albeit usually welcomed with feelings of deep foreboding.

The sight of five moons, on the other hand, is less common. Is it possible the chronicler stumbled upon actual phenomena? Somewhat surprisingly, the answer might be yes. One possibility is that the five moons were the product of an earthly optical illusion, not unlike a mirage in the desert. For this to be the case, the light must pass through two layers of air with different temperatures. The fact that the sighting was reported in December might suggest it was freezing cold, which can also cause mirages. Another possibility is that the eyewitnesses saw the moon through thick glass, possibly during heavy rain. A third possibility is that the likes of Venus, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter were uncommonly huge as they rose alongside the moon on the night in question. Even with the naked eye, Jupiter and Venus, in particular, can be incredibly bright on occasion.

A fourth explanation is that the people of Yorkshire were greeted by the sight of Moon Dogs. Though relatively rare, Moon Dogs or mock moons are an atmospheric optical phenomenon, creating the illusion that the regular moon has bright spots on one, two or all four sides (an example of which can be seen below, source: Wikipedia).

So, what actually happened? Did Roger of Howden and the people of Yorkshire really encounter astronomical sights of wonderment? In truth, we’ll never know. However, in my opinion, there is every possibility the sights were genuine. Coming at a time when astronomy and astrology were deeply intertwined, and such things were viewed as communications from the heavens, it is little surprise that the people of England viewed them with great trepidation.

As the turn of the millennium showed, the new king had plenty to worry about. That year, John ventured to France to conclude the Treaty of Le Goulet with the King of France, culminating in Philip II’s (Augustus) agreeing to officially acknowledge John as Duke of Normandy. In return, John parted with 30,000 marks and submitted to Philip as overlord of the French fiefs - the one exception was the duchy of Aquitaine, which remained the possession of John’s mother, Eleanor. John’s willingness to give up so much for so little was widely lamented in England and undoubtedly hastened Philip’s taking of Normandy in 1204.

Regardless of whether the strange astronomical bodies were genuinely portentous, for John, his reputation as Softsword was already well on its way to being born.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The above stories were included in my book, King John, Henry III and England’s Lost Civil War, published by Pen&Sword History.

Thank you for reading JPD’s History Substack. This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 16, 2024

The Dolgellau Chalice

In my previous article, I discussed the unknown fate of the medieval Welsh Crown Jewels. For almost five hundred years, the whereabouts of the Honours of Gwynedd have been lost to history.

However, there may be one exception.

The piece in question is the so-called Dolgellau Chalice (see above, Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023). Now in the possession of the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, the chalice was discovered on the mountainside of Cwm Mynach, Snowdonia, in 1890. Two years later, it was acquired by one Baron Schroeder - or Schroder - who bequeathed it to the state on his death in 1910.

The chalice’s appearance is impressive. Indeed, few larger or finer have been documented in the whole of Britain. As the above image shows, the silver-gilt body contains a plain, flattened hemispherical bowl on a stem patterned with trefoil leaves above and below the central knop. The lower section, meanwhile, is divided into twelve lobes, connecting to a circular foot embossed with further trefoil-shaped lobes. Research into its makeup has confirmed a thirteenth-century pedigree, which compares with other vessels of the type. The same is true of many pieces of the missing Honours of Gwynedd.

Why it was made, when and for whom are less clear.

Since its discovery in 1890, there have been many theories of its origins. Among the most alluring is that it comprises the seal matrices of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (the Last), his wife Eleanor de Montfort (the daughter of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester) and brother Prince Dafydd, the last independent ruler of Gwynedd. Though the theory is tantalising, it is not without foundation. Contemporary records confirm Edward I had the original matrices melted down and turned into a chalice in 1282, which he presented to the monks of Vale Royal Abbey in Cheshire. What became of the matrices’ chalice following the Dissolution of the Monasteries is unclear. Tradition tells us that it remained the property of the final abbot’s family; however, what happened next is anyone’s guess.

A possible clue to the Dolgellau Chalice’s earlier life can be found on the foot. The signature purports it to be the work of one Nicholas of Herford, presumably a reference to modern-day Hartford. The village is also in Cheshire, thus the same part of the world as Vale Royal Abbey. The Royal Collection Trust, which owns the chalice, states on its website that it may have been made for the monks of Cymer Abbey (see below). The suggestion is an interesting one. While this may suggest it was separate from the Honours of Gwynedd, its thirteenth-century origin would place it in the same time and location as at least one part of the Honours of Gwynedd. The Cross of Neith was deposited at Cymer around the time of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s death in 1282 before its transfer to London. This potentially tallies with the timing of Edward I’s melting down of the matrices of Llywelyn, Eleanor and Dafydd.

Of course, proving beyond doubt that they are one and the same is challenging.

As discussed in my previous two articles, long-standing legend tells that the Honours of Gwynedd and anything else that made up the Welsh Crown Jewels were buried along with Owain Glyndŵr.

The location of Glyndŵr’s grave remains a mystery.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The story of the Dolgellau Chalice is mentioned in my latest thriller, The Lost Crowns, book 5 in the White Hart series. The book is available on Amazon for the introductory price of £0.99 and $0.99 and is free on Kindle Unlimited.

Thank you for reading JPD’s History Substack. This post is public so feel free to share it.