John Paul Davis's Blog: JPD's History Substack, page 2

January 12, 2024

The Mystery of the Welsh Crown Jewels

For millions worldwide, the Crown Jewels of England are among the most important objects still in existence. Metallically valuable and historically priceless, they are commonly viewed as a symbol of more than a thousand years of British history.

It surely comes as little surprise that their home in the Jewel House of the Tower of London has become one of the most visited tourist attractions on the planet.

Far fewer people I’ve encountered are aware that Wales once had its own set of Crown Jewels. Though little mentioned today, for much of the thirteenth century, the Honours of Gwynedd were among the most valuable keepsakes in North Wales. Like their English counterparts, they tied together the history of a fledgling nation.

And became a symbol of native resistance.

Any reference to the medieval Welsh Crown Jewels should be distinct from the modern collection, officially known as the Honours of the Principality of Wales. This set was famously used for the investiture of Prince Charles, now Charles III, at Caernarfon Castle in 1969 and consists of a coronet, a ring, a rod, a sword, a girdle and a mantle. Most of the modern jewels date from the investiture of the future Edward VIII in 1911; the one exception is the coronet, which was custom-made for Prince Charles, based on a royal warrant issued by Charles II around 1677. Amusingly, its creation was only necessary as Edward VIII failed to return the previous one. The coronet and rod were put on display at the Tower of London in 2020 alongside the English collection.

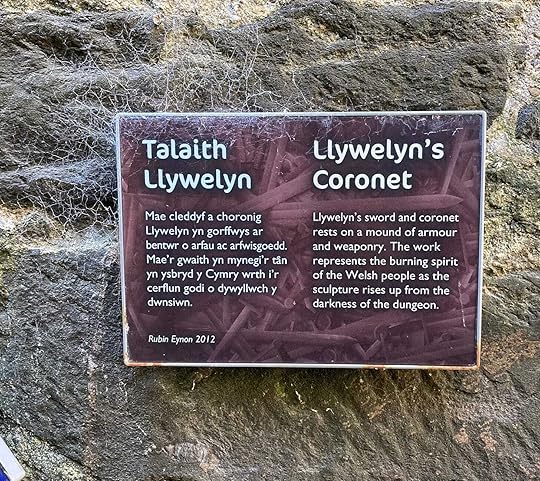

In contrast to the Honours of the Principality of Wales, what became of the original Honours of Gwynedd remains a mystery. Indeed, records from the time are so limited that it’s almost impossible to know what once existed. Sources from the 1280s tell that Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (the Last) deposited something called Llywelyn’s Coronet with the monks of Cymer Abbey (below) shortly before he was killed in 1282. Following the passing of Llywelyn’s younger brother Dafydd, the last independent ruler of Gwynedd, in October 1283, Edward I oversaw the coronet’s transfer to London, where it was presented at the shrine of St Edward the Confessor, who ruled England 1042–1066.

Uncovering a complete history of the coronet is difficult, particularly as no record of its exact age and appearance has survived. Complicating the matter further is the possibility that Llywelyn’s Coronet was one of many crowns. Sources from the reign of Henry III tell of the king presenting a coronet to Llywelyn ap Iorwerth’s son and heir, Dafydd ap Llywelyn, in 1240. Intriguingly, other documents state that Dafydd was already wearing a crown upon meeting the king. This begs an important question: did Dafydd possess more than one coronet, or did the chronicler get ahead of himself? Another intriguing name that crops up in contemporary documents is the Coron Arthur, which literally means Arthur’s Crown. Exciting as the name may sound, this coronet most likely dates from the reign of Owain Gwynedd, the son of Gruffudd ap Cynan, who ruled Gwynedd 1137-70.

What became of either crown is sadly unrecorded. Though the reference to Llywelyn’s Coronet’s relocation from Cymer Abbey to Westminster Abbey is undoubtedly historical, what happened next is where things get misty. Westminster Abbey was famously the subject of a robbery in 1303, resulting in the theft of several important articles, including the Stone of Scone and other items Edward I had acquired from Scotland. The common assumption has long been that Llywelyn’s Coronet was rehomed in the Tower of London when the stolen goods were recovered; however, this is impossible to prove without contemporary receipts. The fact that it was missing from the inventory of 1649 when Oliver Cromwell ordered the English Crown Jewels’ destruction calls this into question.

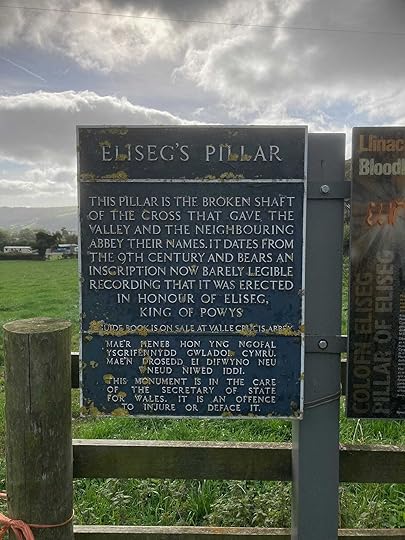

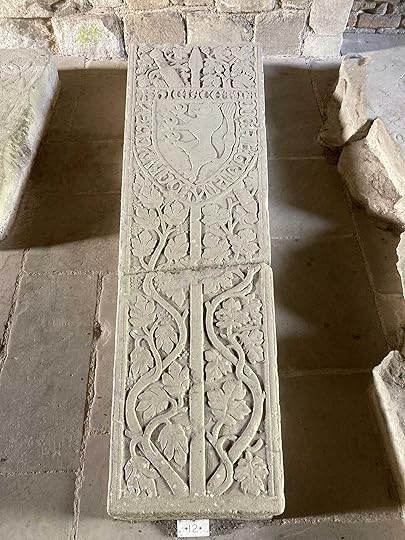

Equally mysterious is the identity of the crown used in the coronation of Owain Glyndŵr in 1404. That Glyndŵr’s coronation in Machynlleth involved one of the above is possible. Equally likely is that he used something new or even older, such as a treasure of the Kingdom of Powys. A descendant of the House of Mathrafal through his father, Glyndŵr was the great-great-great-grandson of Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor, Prince of Powys Fadog, circa 1191-1236. Approximately a quarter of a mile from Madog’s empty tomb (the magnificent slab appears below) at Valle Crucis Abbey lies the Pillar of Eliseg (above), on which the former kings of Powys were listed. The idea that Llywelyn’s Coronet was never returned to Westminster and somehow found its way into Glyndŵr’s possession is a romantic one, albeit impossible to prove.

Further to the transfer of Llywelyn’s Coronet to Westminster in 1284, Edward I took possession of several valuable religious artefacts. Chief among them was the Cross of Neith - or Gneyth - an alleged fragment of the True Cross. The Alms Roll of 1283 records the king received ‘part of the most holy wood of the True Cross’ at Aberconwy, initially a Cistercian house which predated Conwy Castle (see below). Of crucial importance here is that the cross was delivered to Edward by several key Welsh figures led by Dafydd ap Gruffudd’s private secretary, most likely to curry favour with the new regime. On being taken to London, the relic was witnessed by thousands in May 1285 in a parade through the streets that included Edward and his queen, Eleanor of Castile.

How a piece of the True Cross came to Wales in the first place is itself worthy of investigation. Assuming it wasn’t a local fake, the possibility that Hywel Dda (King of Deheubarth, who came to rule much of Wales in the tenth century) acquired it during a pilgrimage to Rome seems plausible. Edward III entrusted the cross to the Dean and Chapter of St George’s Chapel, Windsor, in 1352, where it remained until 1552. The last recorded mention concerns Edward VI ordering its rehousing in the Tower of London.

Like the rest of the Honours, what became of it remains unknown.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The story of the lost Honours of Gwynedd is central to my latest thriller, The Lost Crowns, book 5 in the White Hart series. The book is available on Amazon for the introductory price of £0.99 and $0.99 and is free on Kindle Unlimited.

Start writing today. Use the button below to create your Substack and connect your publication with JPD’s History Substack

January 9, 2024

The Mystery of Owain Glyndŵr's Final Days

‘His grave is beside no church nor under any ancient yew’s shadow. It is in a spot safer and more sacred still. Rain does not fall on it, hail nor sleet chill no sere sod above it. It is forever green with that of eternal spring. Sunny the light on it; close and warm and dear it lies, sheltered from all storms, from all cold or grey oblivion. Time shall not touch it; decay shall not dishonour it. For that grave is in the heart of every true Welshman.’

Such was the view of Owen Rhoscomyl concerning the final resting place of Owain Glyndŵr. For many of Welsh birth or descent, Rhoscomyl’s words require little explanation. Though the location of Glyndŵr’s grave is long lost, in a sense, it has become somewhat immaterial. In the six centuries since his death, his influence on Welsh history and culture has been almost unrivalled, transcending the physical.

His bones may be gone, but his spirit lives on.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Much of Owain Glyndŵr’s story is, of course, well known. Born in Sycarth, Powys, North Wales in 1354, the son of a minor Marcher lord, there is little evidence that he was destined for greatness. A boy of about eleven when his father died, he was fostered by Sir David Hanmer, an Anglo-Welsh justice of the King’s Bench and trained at the inns of court. In time, the aspiring lawyer would marry Hanmer’s daughter, Margaret. Together, they had at least eleven children, many of whom would leave their own mark on history.

How this humble Marcher would turn out to be a timeless, national hero is a story worthy of close study. Despite a typical upbringing, the diligent lawyer was of ancient royal Welsh stock through both parents. On his father’s side, Owain was a descendant of the House of Mathrafal, who had ruled the Kingdom of Powys (arms above) since Roman times. Through his mother, he was descended from the House of Dinefwr, among whose number was Rhys ap Gruffudd (Lord Rhys, 1155-1197), ruler of the ancient Kingdom of Deheubarth in the south. Of similar importance, due to the death of Owain Lawgoch without issue in 1378, Glyndŵr held the senior claim to the throne of Gwynedd through at least two children of Gruffudd ap Cynan (1055-1137). In such ways, one could argue he was uniquely placed to unite the three ancient kingdoms.

Possessed of impressive royal ancestry he may have been, any suggestion that Glyndŵr’s later march to war was inspired by the desire to fulfil any long-established destiny is doubtful. Having spent much of his early life in England, he appears to have developed little xenophobia against the English. In 1384, he lined up among Richard II’s forces against the Scots at Berwick and seemingly enjoyed good relations with the king. Initially, similar was true of the future Henry IV. Things would change, however, following Bolingbroke’s rebellion against Richard II, leading to his becoming king in 1399. Concurrent to Glyndŵr’s opposition to Henry IV’s usurpation and recent anti-Welsh legislation in the English parliament of 1400, Owain’s call to arms stemmed more from a land dispute with his neighbour Baron Grey de Ruthin. As the feud escalated following an unsuccessful petition to parliament, Grey dallied in passing on the royal command to levy troops to border service, technically making Glyndŵr guilty of treason. On being deprived of his lands, he raised the flag of rebellion on 16 September 1400 and took to arms.

For over a decade, Owain proved to be a significant thorn in Henry IV’s side. Victorious at the Battle of Bryn Glas in 1402, he took several of Edward I’s castles in the north, notably Harlech (see below), in early 1404, which he used as his headquarters. Despite his impressive start, the death of key ally Sir Henry Percy (Hotspur) at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, followed by successive defeats at Grosmont and Pwll Melyn (above) in 1405, ensured the turning of the tide. The short-lived alliance with Sir Edmund Mortimer and Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland, dubbed the Tripartite Indenture, failed to survive 1405. Within a year, what remained of his French allies left for home. Though the resilient Prince of Wales successfully pursued guerilla warfare for three long years, the hammer blow fell in 1409 with the loss of Harlech. Legend says he escaped the castle disguised as a peasant when the English granted the old and infirm passage.

What became of Glyndŵr following the fall of Harlech remains one of the great mysteries of Welsh history. Reports of a successful raid into Shropshire the following year before capturing Dafydd Gam in 1412 appear historical. Yet any evidence he was seen alive after that is difficult to authenticate. One contemporary account tells that he disappeared in 1415 on St Matthew’s Day. The chronicler Adam of Usk suggests he died shortly after the Battle of Agincourt that same year, buried and reburied when the English learned of his burial. Though the chronicler offers no clue concerning the grave’s location, the story may connect with another tradition that Glyndŵr arranged a fake burial for himself at the church of Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant near the Berwyn Mountains in North Wales.

Further to the musings of the chroniclers, the number of local traditions is seemingly endless. Among the most popular are that he died in a forest in Glamorgan or a cave in Gwent. Another states that he escaped in the guise of a hooded figure holding a sickle. Some say he was laid to rest in Herefordshire on Hope Hill. Others, the Golden Valley. Of particular interest are claims that he spent his final days with the families of his impressive daughters. Herefordshire legend speaks of him frequenting a deer park in Kentchurch Court, property of his daughter Alys and son-in-law Sir John Scudamore, in the summer of 1414. Another tells that he held out in the attic of Croft Castle (below), the property of his daughter Janet and her husband, Sir John Croft, allowing him to commute between there, Kentchurch and another daughter’s home at Monnington.

Perhaps the most romantic theory is that he was interred near Valle Crucis Abbey (see below) in the company of his forebears, notably Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor, Prince of Powys Fadog (circa 1191-1236). An alluring legend from the 15th century tells that the Abbot of Valle Crucis was out walking one morning, only to chance upon Owain’s ghost. On being told, “You’ve risen too early this morning,” the abbot responded, “No, it is you who have risen too early, by a hundred years.”

We may never know the exact truth of what became of Owain Glyndŵr. That the location of his grave was a mystery in his own time seems to confirm that knowledge of his whereabouts was limited to a select few. This being said, accepting certain likelihoods seems reasonable. An expert in guerilla warfare, concluding that he sought shelter in caves and lived mainly under the radar is highly likely. Though the stories of being reburied or living out his final days with his daughters have a certain romanticism, it begs many questions. If the English did discover his place of burial, why not exhume it and put his body on display for all to see? Likewise, how did his family maintain such a convincing pretence when their homes were undoubtedly closely watched? The lack of mention of him in 1421, when his son Maredudd accepted a royal pardon from Henry V, likely offers evidence he had passed by then. By this time, he would have been over sixty.

Lost from history the grave of the last native-born Prince of Wales may be, it speaks volumes of his character that a man whose first forty years passed so uneventfully could rise to such heights. In such ways, Rhoscomyl’s words seem particularly appropriate. Like King Arthur and Lleu Llaw Gyffes, Owain Glyndŵr has become more spirit than man. Perhaps in so doing, he really has satisfied the criteria of the Mab Darogan, or son of prophecy. Or maybe the lack of grave may yet prove his greatest legend true. That he sleeps yet never dies. Ready to awaken in the hour of Wales’s great need.

The story of Owain Glyndŵr’s lost grave is central to my latest thriller, The Lost Crowns, book 5 in the White Hart series. The book is available for purchase on Amazon for the introductory price of £0.99 and $0.99.

January 5, 2024

Tales from the Tower: The Rise and Fall of Ranulf Flambard

As established in my previous article, the first stone Tower of London appears to have been completed by the reign of Henry I. It is unclear if England’s first three Norman kings ever used the lodgings there. Either way, from the reign of Henry I onwards, evidence suggests that the accommodation facilities were in regular use and not just for the law-abiding. Though Guldulf’s Tower lacked specifically built dungeons, it perhaps comes as little surprise that walls intended to keep enemies out proved equally good at keeping them in.

It is perhaps one of the Tower’s great ironies that its first prisoner was also its first escapee. By the time of his incarceration in 1100, Ranulf Flambard was arguably the most important non-royal in England. The son of a Norman cleric, Flambard followed his father into the Church and helped establish the Domesday Book before becoming one of William Rufus’s most vocal supporters.

When Rufus (pic below) became king, succeeding his father, William the Conqueror, who died in September 1087, Flambard was chaplain to Maurice, Bishop of London, and keeper of the royal seal: more or less lord chancellor. After acquiring a prebend in the diocese of Salisbury, whose new cathedral at Old Sarum was fast becoming a local centre point, he obtained similar titles while developing a dubious reputation for enriching himself with the revenues of deceased canons. By the 1090s, his eye for business saw him made chaplain of Rufus’s court and appointed chief treasurer. He may also have been England’s first justiciar, more or less Prime Minister.

True to his previous form, Flambard needed little excuse to drum up extra business. When charged with raising the fyrd – the English militia – for the king’s battles with his brother Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy, he regularly pocketed illicit profits by obtaining funds from the warriors’ home villages, as well as levying ‘reliefs’ against the sixteen abbeys and bishoprics under his administration. Though his deeds proved effective, they didn’t go unnoticed. Writing at the time, the local chronicler, William of Malmesbury, lamented, ‘he skinned the rich, ground down the poor, and swept other men’s inheritances into his net.’

In 1099, Flambard secured his most significant promotion to that date, to the See of Durham. Durham was a unique fish in England. Being a ‘county palatine’, Flambard was enthroned as a prince-bishop rather than the usual bishop of a regular diocese. Unsurprisingly, his first year in Durham was blighted by similar accusations of corruption. Echoing the words of Malmesbury, another chronicler decried that ‘justice slept’ and ‘money was the Lord’. On the plus side, Flambard clearly shared Bishop Gundulf’s building talents. Construction of its cathedral, arguably the largest in northern Europe to that date, began on his watch – even today, it is one of the finest in the north of England. In London, the first stone bridge and Westminster Hall – the most prominent secular building in northern Europe – both occurred at his direction. Far more ironically, he also commissioned a curtain wall surrounding the Tower of London.

Flambard had been in Durham less than a year when William II died in 1100, most likely murdered, riding in the New Forest. After mourning the king at Winchester, his well ran dry on the accession of Rufus’s younger brother, Henry I (pic below). Well aware of the bishop’s sinful reputation, the new king stripped Flambard of his offices of state and imprisoned him on charges of embezzlement.

With this, he became the Tower’s first prisoner.

For six months, the disgraced cleric wiled his time away within the walls of Bishop Gundulf’s Tower. Despite being imprisoned, his lodgings were undoubtedly comfortable, per his esteemed position in the Church. Aided by his remaining wealth, he was allowed to maintain his servants, who brought his meals in from the outside world.

Unsurprisingly, the crafty bishop and politician lost little of his charisma and quietly bided his time as he sought liberation. Famed as an entertainer and compere, he frequently hosted banquets for his gaolers, slowly earning their trust. After organizing one such supper on 2 February 1101, for which he ensured either extra quantities of wine or alternative liquids of additional alcoholic volume, he waited for his captors to become inebriated before putting his plan into action. Using a rope smuggled into his cell inside either a ‘gallon of wine’ or a barrel of oysters, he attempted to abseil down the Tower walls. Despite injuring himself after jumping the remaining 20 feet, he limped to the outer wall and scaled it to where his allies had left him a horse. On making it downriver, a ship took him to Normandy and sanctuary with the king’s elder brother, Robert Curthose.

Much debate has occurred concerning how Flambard slipped the net so impressively. Although lax security or the inside knowledge of the constable of the Tower, William de Mandeville, are both plausible, the inferior size of the Tower and the cunning of the man himself undoubtedly contributed. Within a short time of arriving in Normandy, Flambard was busily aiding Curthose in his attempts to invade England. Fortunately for all concerned, the warring brothers signed an awkward truce at Alton, and the king eventually restored Flambard to the See of Durham, which he maintained until he died in 1128.

His final decades show evidence of amended ways, giving generously to his men and those experiencing poverty. Later achievements include completing Durham Cathedral, fortifying the city with a wall around Durham Castle, building Norham Castle and endowing the collegiate church of Christchurch in Hampshire. He also oversaw the translation of St Cuthbert’s relics into its new tomb, which survived until the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Thanks for reading JPD’s History Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The story of Bishop Ranulf and the early years of the Tower of London features in my book, A Hidden History of the Tower of London - England’s Most Notorious Prisoners, published by Pen&Sword History

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/officiallyjpd/

(The app formerly known as) Twitter: https://twitter.com/unknown_templar

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/people/John-Paul-Davis/61554500203836/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@officiallyjpd

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/3119270.John_Paul_Davis

Thank you for reading JPD’s History Substack. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 15, 2018

The Rosicrucian Prophecy

I'm delighted to announce that my latest thriller, The Rosicrucian Prophecy, is now available to purchase on Kindle. The story is Book 2 in the White Hart series, following on from the Crown Jewels Conspiracy. Although a sequel, the books are plot independent and can be read in any order.

Details below.

In Medieval England the defence of the realm in times of need rested on the shoulders of twelve men – a secret brotherhood of knights, who answered only to the ruler of England. They were called The White Hart.

In Medieval England the defence of the realm in times of need rested on the shoulders of twelve men – a secret brotherhood of knights, who answered only to the ruler of England. They were called The White Hart.As they are now…

November 1604:an ancient grave is discovered in a subterranean crypt somewhere in the English countryside. Though the identity of the deceased remains a mystery, a strange symbol etched into the slab offers a bizarre clue to his background. Exactly a year later, an anonymous letter delivered to King James I of England contains a shocking warning. If the contents of the grave are not handed over, the Palace of Westminster will be subjected to an almighty blow at the reconvening of parliament.

Within days, a solitary conspirator is arrested as he prepared to set light to 36 barrels of gunpowder . . .

Over four hundred years later,a famous European socialite arrives in London on the fifth of November in a visit that has the potential to decide the UK’s future with the EU. Despite widespread scepticism over her true intentions, when her car is the subject of a bomb attack by a known terrorist close to Big Ben, panic threatens to engulf the city.

As the eyes of the world become absorbed by the ruthless assassination, less than one hundred metres away, a series of hidden CCTV cameras capture footage of over fifty terrorists entering the undercroft of the Houses of Parliament before proceeding to take all within hostage. With the entire building under lockdown, the terrorists’ demands are made clear. If the same mysterious demands made in 1605 are not met, the Palace of Westminster will finally succumb to its fate.

For White Hart agents Mike Hansen and Kit Masterson, the simultaneous attacks are just the start of an unfathomable chain of events that threaten to tear a hole through the heart of British government. An ancient brotherhood whose existence has long been deemed a myth has finally surfaced, intent on carrying out their legendary purpose. Guided by vague leads left behind in the confessions of the original gunpowder plotters, three forgotten 17th-century German manifestos and the terrorists’ own demands, the White Hart have no choice but to plot their own assault on parliament, while frantically attempting to uncover the truth behind the legendary tomb. For the second time in four centuries, the Palace of Westminster stands on the brink…

And only by uncovering one of mankind’s oldest secrets can they prevent its annihilation. . .

US readers can purchase the book for the introductory price of $1.49 here UK readers can do so for £0.99 hereIt is also available free to subscribers of Kindle Unlimited

October 31, 2017

NEW RELEASE!WHAT IF THE CROWN JEWELS OF ENGLAND, SCOTLAND...

WHAT IF THE CROWN JEWELS OF ENGLAND, SCOTLAND AND FRANCE WERE TO BE STOLEN...

WHAT IF THE GREAT FIRE OF LONDON WERE TO HAPPEN AGAIN...

WHAT IF ALL FOUR WERE TO HAPPEN ON THE SAME NIGHT...

I'm delighted to announce my latest thriller, The Crown Jewels Conspiracy, is now available for purchase.

UK readers can download the kindle version for the introductory price of £1.99 here. US readers can do so for $2.99 here, in addition to downloading it for free as a subscriber of Kindle Unlimited.

FROM THE BACK PAGE

In Medieval England the defence of the realm in times of need rested on the shoulders of twelve men – a secret brotherhood of knights, who answered only to the ruler of England. They were called The White Hart.

As they are now…

In the hot late summer of 1666, a strange document is delivered to the King of England. The writing, though easy to read, refers to an obscure promise: a great fireworks display will soon take place, culminating in a pure body of flame higher than St Paul’s.A week later and with the city burned to rubble, the hunt is on for its mysterious sender.

Present day:When flames are spotted inside a modern building located at the exact site of Thomas Farriner’s bakery in Pudding Lane on the anniversary of the Great Fire, few are prepared that this is just the first phase of the greatest terror attack in living memory. But when information reaches the Prime Minister of a second fire spreading in Edinburgh and a break-in at the Tower of London, it isn’t long before chaos ensues.

For White Hart agents Mike Hansen and Kit Masterson, the escalating attacks are just the start of a bizarre sequence of events that threaten to send the present and past on a collision course. A forgotten foe has finally resurfaced, their ancient threat being carried out. Armed with both the latest in modern technology and cryptic clues from the nation’s dark past, they have no choice but to tackle the threat head on, while also frantically attempting to solve a centuries’ old puzzle before it’s too late. If successful, they could yet save both cities from certain destruction.

But only by uncovering one of history’s best-kept secrets can they prevent the past from repeating itself. . .

June 1, 2016

New Release - The Cortés Trilogy

After over twelve months of silence, I'm delighted to announce the release of an entire series in a special, one-off release.

After over twelve months of silence, I'm delighted to announce the release of an entire series in a special, one-off release.The Cortés Trilogy

Mexico 1520: As the Aztec Empire burns to ash at Hernán Cortés’s feet, in another part of the country a great treasure lies hidden in a sacred place watched over by its keepers. Throughout the land, a strange legend has long told of an ancient people dwelling deep within the jungle whose possessions include a precious set of stones with the potential to bring unlimited power to its owner. As well as wealth beyond their wildest dreams . . .

1904: In an old graveyard in a remote part of the Isles of Scilly, a distinguished academic makes a surprising discovery. The inscriptions on the gravestones are unlike any he has ever seen, at least in that part of the world. The clues point to an astounding possibility. A forgotten Spanish legend. And a four-hundred-year-old cover-up!

Present Day:History lecturer Dr Ben Maloney is sitting in his office when the phone rings. A call from his cousin is rarely anything out of the ordinary, but today what he has to say is anything but normal. Their great-great-grandfather’s body has been discovered in a boat near a deserted island in the Isles of Scilly. With a bullet through his skull!

Dropping everything, the cousins’ decision to visit the site of their ancestor’s demise soon proves to be one that will change their lives forever. With nothing but a hundred-year-old diary and legends from the past to guide them, Ben soon realises their quest to solve the riddle of their ancestor’s death will require them to take on an altogether greater mystery that will lead them not only halfway across the world delving deep into humanity’s bloodiest past but potentially to their own deaths. An unimaginable treasure remains undiscovered – one with the ability to change the world for better or worse. And some will stop at nothing to find it . . .

The Cortés Trilogy includes:

The Cortés Enigma, new and revised edition

The Cortés Revenge, new and previously unreleased

The Cortés Revelation, new and previously unreleased

Out of love for the many who bought the first edition of The Cortés Enigma - if not the Hot Box as well! - the trilogy will be available for the introductory price of £1.99 and $2.99

UK readers can download their copy Here

US readers can download your copy Here

Thanks as always for your incredible support. Enjoy the carnage!

August 18, 2015

NEW RELEASE - THE BORDEAUX CONNECTION

I am delighted to announce the release of my latest thriller. The Bordeaux Connection is now available to purchase from Amazon worldwide!

In Medieval England the defence of the realm in times of need rested on the shoulders of twelve men – a secret brotherhood of knights, who answered only to the ruler of England. They were called The White Hart.

As they are now…

When a series of explosions rock the Scottish capital, The White Hart is once again called into action. While the attackers flee Edinburgh with a hoard of priceless historical manuscripts, in a lonely village in England recent intelligence photographs suggest a potentially shocking connection between the suspected culprits and the wife of the Deputy Prime Minister…

For White Hart agents Mike Hansen and Kit Masterson, the new lead is just the first piece of a potentially explosive puzzle that threatens to tear a hole in the heart of government. As a new threat soon reveals itself, their only chance to bring to an end the recent chain of ruthless activities is to follow the trail to the bitter end. Right to the heart of its deadly conspiracy...

Part one of a brand new series…

UK customers can check out the book here for the introductory price of £0.99. US customers can do the same here for $1.49.

May 10, 2015

NEW RELEASE: THE COOL BOX - SEVEN ICE-SHATTERING THRILLERS FROM SEVEN BEST-SELLING AUTHORS

Following on from the success of

The Hot Box

, I'm delighted to announce the release of a brand new box set titled,

The Cool Box - seven ice-shattering thrillers from seven best-selling authors

. The offer is for a limited time only, and among the seven is my latest thriller,

The Bordeaux Connection

, part one of a brand new series.

Following on from the success of

The Hot Box

, I'm delighted to announce the release of a brand new box set titled,

The Cool Box - seven ice-shattering thrillers from seven best-selling authors

. The offer is for a limited time only, and among the seven is my latest thriller,

The Bordeaux Connection

, part one of a brand new series.UK customers can download the book Here for the special price of £0.99. US customers can download it Here for $0.99.

February 24, 2015

Guest Blog by Darren Baker - The Long Reach of the Montforts

Darren at Lewes in East Sussex, the site of the Battle of Lewes in 1264,

Darren at Lewes in East Sussex, the site of the Battle of Lewes in 1264,in which Simon achieved a surprise victory over the

numerically-superior forces of Henry III, Prince Edward,

and Richard, Earl of CornwallStopping by the Unknown Templar blogspot this week, I'm pleased to introduce biographer and writer Darren Baker, author of the well regarded newly released With All For All - A biography of Simon de Montfort. Darren's is the first biography of the enigmatic de Montfort since JR Maddicott's acclaimed work in 1996, and is already being celebrated as a much needed key addition to one of the most fascinating, yet understudied periods in England's history.

One of the more curious accounts of the English civil war of the 1260s comes from ‘The Templar of Tyre’, an anonymous section of the wider history known as Gestes des Chiprois. Although dealing principally with the crusader states through much of the thirteenth century, the author himself was not a member of the Templar Order. The title is a modern usage that reflects his service to the master of the Templars and, before that, to the wife of the lord of Tyre, John de Montfort. In all likelihood it was while working in the household of this Montfort family that the Templar got his information about the events leading up to and after Evesham.

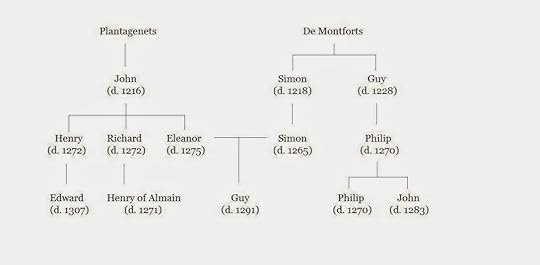

Map of TyreJohn de Montfort was the son of Philip, whose father Guy was a brother of Simon de Montfort’s father. When Simon arrived in the Holy Land on crusade in 1240, Philip was already there. He had been born there sometime after 1204 when Guy, following the Fourth Crusade, married into the family of the local nobility. Philip’s connections and relations put him in a good position to promote his newly arrived cousin, the brother-in-law of the king of England and Holy Roman Emperor, to be the governor of the region in a bid to unite the warring Christian factions. Nothing came of the attempt and Simon soon returned to England, but Philip’s star rose until he was eventually made Lord of Tyre. Even though he was unable to stop the advancement of the Muslim Baibars, the sultan wasn’t taking any chances and had him assassinated in 1270 as he prayed in church, in a scene described by the Templar. He was succeeded by John, who ruled Tyre until his death in 1283. Philip had a son from a previous marriage and life in France, who was also named Philip. Simon evidently knew and trusted him, for in 1259 he made him his deputy for Bigorre, a little county near the Pyrenees that came to him through his older brother, another Guy who, like their father Simon and uncle Guy, also died during the Albigensian Crusade. This Philip later became Charles of Anjou’s right-hand man as he went about conquering Sicily in 1265, the same year that saw Simon’s downfall and death at Evesham and the imprisonment of his fourth son, another Guy de Montfort. This Guy escaped the following year and had joined up with his second cousin Philip by the time of Charles’ victory at Alba in 1268. Two years later, when Charles talked his brother Louis IX of France into making Tunis the first stop of his latest crusade, ostensibly as part of Charles’ plan to create a Mediterranean Empire, Philip went along and died in the epidemic that also claimed Louis and other members of the French royal family. Charles, of course, survived.

Map of TyreJohn de Montfort was the son of Philip, whose father Guy was a brother of Simon de Montfort’s father. When Simon arrived in the Holy Land on crusade in 1240, Philip was already there. He had been born there sometime after 1204 when Guy, following the Fourth Crusade, married into the family of the local nobility. Philip’s connections and relations put him in a good position to promote his newly arrived cousin, the brother-in-law of the king of England and Holy Roman Emperor, to be the governor of the region in a bid to unite the warring Christian factions. Nothing came of the attempt and Simon soon returned to England, but Philip’s star rose until he was eventually made Lord of Tyre. Even though he was unable to stop the advancement of the Muslim Baibars, the sultan wasn’t taking any chances and had him assassinated in 1270 as he prayed in church, in a scene described by the Templar. He was succeeded by John, who ruled Tyre until his death in 1283. Philip had a son from a previous marriage and life in France, who was also named Philip. Simon evidently knew and trusted him, for in 1259 he made him his deputy for Bigorre, a little county near the Pyrenees that came to him through his older brother, another Guy who, like their father Simon and uncle Guy, also died during the Albigensian Crusade. This Philip later became Charles of Anjou’s right-hand man as he went about conquering Sicily in 1265, the same year that saw Simon’s downfall and death at Evesham and the imprisonment of his fourth son, another Guy de Montfort. This Guy escaped the following year and had joined up with his second cousin Philip by the time of Charles’ victory at Alba in 1268. Two years later, when Charles talked his brother Louis IX of France into making Tunis the first stop of his latest crusade, ostensibly as part of Charles’ plan to create a Mediterranean Empire, Philip went along and died in the epidemic that also claimed Louis and other members of the French royal family. Charles, of course, survived.

Guy de MontfortGuy de Montfort wasn’t there. Impressed by his skills, Charles had sent him to Tuscany to take command as his vicar-general. In 1271 Charles went to Viterbo, just north of Rome, in an attempt to break the deadlock over electing a new pope. Presumably he summoned Guy to meet him there. He arrived on 12 March with a large train of knights and discovered that Charles’ entourage included his English cousin Henry of Almain. The next day Guy found Henry in a church and slew him at the altar before dragging his body out onto the square and mutilating it in mock retribution for the disgraceful act preformed on his father’s body at Evesham. Guy was stripped of his lands and honours, did some time under house arrest, but was back fighting under Charles until he was captured near Sicily in 1287. He died in prison in 1291, twenty years after the murder and right around the time the Templar fled Acre as the Saracens conquered the remaining Christian strongholds in the Holy Land. He went to Cyprus and began his chronicle, the first known copy of which appeared in 1343.

Guy de MontfortGuy de Montfort wasn’t there. Impressed by his skills, Charles had sent him to Tuscany to take command as his vicar-general. In 1271 Charles went to Viterbo, just north of Rome, in an attempt to break the deadlock over electing a new pope. Presumably he summoned Guy to meet him there. He arrived on 12 March with a large train of knights and discovered that Charles’ entourage included his English cousin Henry of Almain. The next day Guy found Henry in a church and slew him at the altar before dragging his body out onto the square and mutilating it in mock retribution for the disgraceful act preformed on his father’s body at Evesham. Guy was stripped of his lands and honours, did some time under house arrest, but was back fighting under Charles until he was captured near Sicily in 1287. He died in prison in 1291, twenty years after the murder and right around the time the Templar fled Acre as the Saracens conquered the remaining Christian strongholds in the Holy Land. He went to Cyprus and began his chronicle, the first known copy of which appeared in 1343.

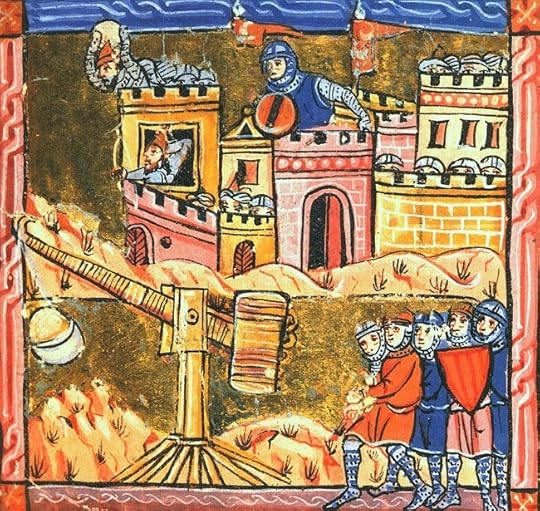

Siege of AcreThe Templar’s account of the English civil war starts in 1265 by introducing Simon de Montfort as the earl of Gloucester. Mistakes like these abound, the result of the Templar recalling years later what he had overheard as events in the west were filtered into the household where he worked in Tyre. He does not mention that Simon was a relative of John’s, only that he was an ‘important man’ married to the sister of the king of England. His claim that Simon was reluctant to get involved in the reform movement, until forced to by Henry, of all people, seems to be his take on Montfort’s initial refusal to take the oath to abide by the Provisions of Oxford. It provides an opening for the Templar to cite Simon’s well-known determination afterwards to keep his oath at all costs, and to force the king to do likewise. While Simon is described as a ‘worthy knight, bold and courageous’, the Templar claims he allowed himself to be taken in by Edward’s ruse with the banners and that led to his defeat. Edward’s escape is also treated with legendary status, suggesting that the Templar learned of these events from Edward’s men after they arrived in the Holy Land on crusade in 1271. Clearly these stories were put into circulation in the hope of bolstering the image of the man who had come to chop heads. Indeed, Edward would escape an assassination attempt as Philip de Montfort had not only the year before.Henry, as usual, comes off the worst of the three. There’s no indication of his many endearing qualities, just a king who favoured foreigners, went back on his word, and got himself captured. The Templar makes him sound like his father John when he says the king ‘rounded up the rebels’ upon his release and had some of them killed, the others he let starve to death. Supposedly this took place in Salisbury, but why there nobody knows. By far the strangest episode related by the Templar deals with the murder of Henry of Almain. In his version of events, Simon is not killed at Evesham, only captured, and Edward asks Almain, his cousin like Guy’s, what he should do with him. Almain advises him to chop his head off, otherwise there will be no peace or an end to the conflict. To avoid the shame of killing him after he was captured, it should be made to look as if Simon fell in battle. So Edward waits until nightfall, chops Simon’s head off, and has his body flung onto the battlefield. Apparently the whole point here is to rationalise the killing of Henry of Almain. Perhaps the Templar did not know that he was in France at the time of Evesham, albeit contracting a marriage to the daughter of Simon’s mortal enemy, and that Guy killed him because he was the most convenient target yet available for the family’s vengeance. It is nevertheless interesting that Edward, despite whose counsel it was, should again be portrayed as sneaky. It would seem his well-deserved reputation for deviousness followed him wherever he went.

Siege of AcreThe Templar’s account of the English civil war starts in 1265 by introducing Simon de Montfort as the earl of Gloucester. Mistakes like these abound, the result of the Templar recalling years later what he had overheard as events in the west were filtered into the household where he worked in Tyre. He does not mention that Simon was a relative of John’s, only that he was an ‘important man’ married to the sister of the king of England. His claim that Simon was reluctant to get involved in the reform movement, until forced to by Henry, of all people, seems to be his take on Montfort’s initial refusal to take the oath to abide by the Provisions of Oxford. It provides an opening for the Templar to cite Simon’s well-known determination afterwards to keep his oath at all costs, and to force the king to do likewise. While Simon is described as a ‘worthy knight, bold and courageous’, the Templar claims he allowed himself to be taken in by Edward’s ruse with the banners and that led to his defeat. Edward’s escape is also treated with legendary status, suggesting that the Templar learned of these events from Edward’s men after they arrived in the Holy Land on crusade in 1271. Clearly these stories were put into circulation in the hope of bolstering the image of the man who had come to chop heads. Indeed, Edward would escape an assassination attempt as Philip de Montfort had not only the year before.Henry, as usual, comes off the worst of the three. There’s no indication of his many endearing qualities, just a king who favoured foreigners, went back on his word, and got himself captured. The Templar makes him sound like his father John when he says the king ‘rounded up the rebels’ upon his release and had some of them killed, the others he let starve to death. Supposedly this took place in Salisbury, but why there nobody knows. By far the strangest episode related by the Templar deals with the murder of Henry of Almain. In his version of events, Simon is not killed at Evesham, only captured, and Edward asks Almain, his cousin like Guy’s, what he should do with him. Almain advises him to chop his head off, otherwise there will be no peace or an end to the conflict. To avoid the shame of killing him after he was captured, it should be made to look as if Simon fell in battle. So Edward waits until nightfall, chops Simon’s head off, and has his body flung onto the battlefield. Apparently the whole point here is to rationalise the killing of Henry of Almain. Perhaps the Templar did not know that he was in France at the time of Evesham, albeit contracting a marriage to the daughter of Simon’s mortal enemy, and that Guy killed him because he was the most convenient target yet available for the family’s vengeance. It is nevertheless interesting that Edward, despite whose counsel it was, should again be portrayed as sneaky. It would seem his well-deserved reputation for deviousness followed him wherever he went.

Henry of AlmainThe Templar ends by describing Guy’s connections in Italy and how the pope absolved him of his deed. He mentions again that the two men were cousins, thus reiterating the intensely personal nature of the civil war. That was probably his intention all along in providing a narrative that he himself had to know was outlandish in some parts, like his statement that Henry of Almain was on his way to be crowned emperor of the Germans when Guy struck. Here was clearly an important saga unfolding in a part of the world only a handful of them might ever see, so it wasn’t necessarily important how it all happened, just that it happened at all. However his account came to be embellished certainly takes nothing away from the Templar as an historian, particularly his eyewitness reports of the end of the crusader states. There may be, moreover, some place for his work yet in researching the years of the Montfortian struggle. Peter Edbury, whose translation of ‘The Templar of Tyre’ is used here, suggests it might be worthwhile in determining whether any of his erroneous claims turn up elsewhere. One has, at least, where the Templar says it was Simon, and not his son Henry de Montfort, who was out riding with Edward when he escaped. This same mistake was made by none other than Robert of Gloucester, whose particulars of the battle of Evesham are the ones most often cited today.

Henry of AlmainThe Templar ends by describing Guy’s connections in Italy and how the pope absolved him of his deed. He mentions again that the two men were cousins, thus reiterating the intensely personal nature of the civil war. That was probably his intention all along in providing a narrative that he himself had to know was outlandish in some parts, like his statement that Henry of Almain was on his way to be crowned emperor of the Germans when Guy struck. Here was clearly an important saga unfolding in a part of the world only a handful of them might ever see, so it wasn’t necessarily important how it all happened, just that it happened at all. However his account came to be embellished certainly takes nothing away from the Templar as an historian, particularly his eyewitness reports of the end of the crusader states. There may be, moreover, some place for his work yet in researching the years of the Montfortian struggle. Peter Edbury, whose translation of ‘The Templar of Tyre’ is used here, suggests it might be worthwhile in determining whether any of his erroneous claims turn up elsewhere. One has, at least, where the Templar says it was Simon, and not his son Henry de Montfort, who was out riding with Edward when he escaped. This same mistake was made by none other than Robert of Gloucester, whose particulars of the battle of Evesham are the ones most often cited today.For more on Darren, you can visit his website www.simon2014.com or check out the book on Amazon UK and US

Family tree of the Royal Family of England and the de Montforts. The marriage between Simon and Henry III's younger sister, Eleanor, made Simon's relationship with the King frequently uncomfortable

Family tree of the Royal Family of England and the de Montforts. The marriage between Simon and Henry III's younger sister, Eleanor, made Simon's relationship with the King frequently uncomfortable

January 9, 2015

Cromwell and the Crown jewels - what really became of England's lost treasure?

View across the battlefield of Edgehill - even today

View across the battlefield of Edgehill - even todayit is soaked in atmosphereWith Charles I dead and his royalist accomplices jailed, fined or condemned to death, candidates to replace him on the throne were sorely limited. Whilst his daughter Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia, remained in exile in The Hague after being ousted by the Spanish and the Catholic league, Charles’s heir and logical successor, his eldest son Charles Stuart, was planning his own military campaign against the Parliamentarians. Recently crowned Charles II of Scotland by his subjects in Edinburgh, his army headed south into England in 1650 and was abruptly dispatched by opposition forces in Worcester, forcing him to flee to the continent.

The Battle Obelisk at Naseby, the decisive

The Battle Obelisk at Naseby, the decisivebattle of the Civil WarHad Charles succeeded, England’s history might have been very different. Instead, as Oliver Cromwell and his New Model Army swept away the last elements of dissent in Ireland and the Midlands, the wind of change that had already been blowing steadily throughout England for over a decade was ready to unleash its heaviest gale. The Rump Parliament, having already brought the king to trial in January 1649, wasted little time in launching a similar attack on the aristocracy and the institution of the monarchy. On 6 February the House of Lords was abolished after a vote in the House of Commons, and within a day a vote was cast to end the line of Stuart succession. From that moment forth England would no longer be ruled by any one person deemed of royal blood, but instead become a commonwealth: a government comprised of a forty-one-man council of state, with the prominent Cromwell sitting unrivalled as its chief citizen. Not as a king. But a politician.The outcome of the Civil War will forever be remembered as a decisive moment in England’s history, and not just for the death of the king. Many of England’s mighty castles, trademarks of the lost dynasties, now lay in ruin, destined for destruction or decay, while the king’s personal possessions were commandeered, many finding a new home under the watchful eye of the new ruler. The symbol of the monarch, so long used to authenticate acts of Parliament, was removed from the great seal and as Cromwell’s forces took over the city of London, the coronation regalia that remained scattered within The Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London were removed from the public eye. Documents from the time confirm the majority of the items were sold, and melted down.Like the king and the institution they represented, the original crown jewels of England ceased to exist.

Edward the Confessor enthroned at Westminster

Edward the Confessor enthroned at Westminster Abbey, as recorded in the Bayeux TapestryThe idea that the Crown jewels of England could ever have been destroyed seems almost unthinkable. Anyone who has seen the present collection behind thick glass in the Jewel House of The Tower of London, watched over by the loyal Yeoman Warders, will undoubtedly acknowledge that there is something unique about them, as if their very appearance is inseparable from that of the monarch, including the kings and queens of the past. The term Crown jewels is itself worthy of further explanation. The term incorporates every item connected with the ceremony from metal to vestments, not merely the crown. Coronation regalia has always played a vital and, at times, dramatic part in England’s history. As recently as 1988, archaeologists discovered crowns from the 2nd century BC. Similar finds have also been recorded from the Saxon era.

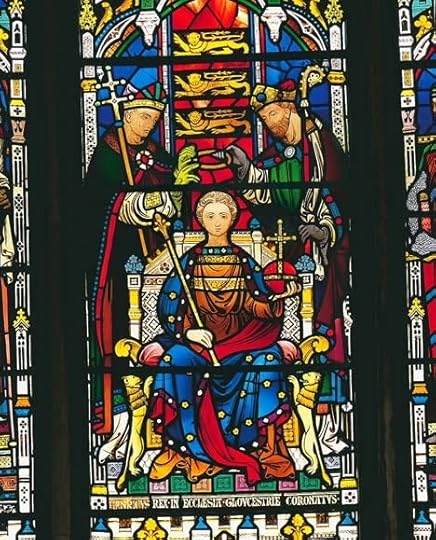

William the ConquerorWilliam the Conqueror’s invasion in 1066 culminated with his being crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey. The Bayeux Tapestry shows both Edward the Confessor and Harold Godwinson wearing a gold crown, and according to the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, that records the history of Britain from around 60BC up until about 1154, William wore a crown on no less than three occasions a year. There are few, if any, surviving records of what exactly the Crown jewels consisted of at that time. Around 15 October 1216, just four days before his death, King John’s entire baggage train was wiped out by a tide in The Wash as he prepared to cross into Norfolk. There is a good deal of uncertainty about what precisely was lost. At his coronation at Gloucester Cathedral on 28 October, John’s son, Henry III, was crowned with a plain hoop of gold, property of Henry’s mother. The usual crown was apparently missing, though whether this was because it had been among the valuables washed away on the east coast or because the circumstances of the war made it inaccessible remains unclear.

William the ConquerorWilliam the Conqueror’s invasion in 1066 culminated with his being crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey. The Bayeux Tapestry shows both Edward the Confessor and Harold Godwinson wearing a gold crown, and according to the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, that records the history of Britain from around 60BC up until about 1154, William wore a crown on no less than three occasions a year. There are few, if any, surviving records of what exactly the Crown jewels consisted of at that time. Around 15 October 1216, just four days before his death, King John’s entire baggage train was wiped out by a tide in The Wash as he prepared to cross into Norfolk. There is a good deal of uncertainty about what precisely was lost. At his coronation at Gloucester Cathedral on 28 October, John’s son, Henry III, was crowned with a plain hoop of gold, property of Henry’s mother. The usual crown was apparently missing, though whether this was because it had been among the valuables washed away on the east coast or because the circumstances of the war made it inaccessible remains unclear.

The first coronation of Henry III, from a window

The first coronation of Henry III, from a windowat Gloucester CathedralIn 1220, when Henry was crowned for a second time, the ceremony, attended by notably more prelates and barons than on the first occasion, was described in much more detail. Records of that event have identified the crown used on that occasion as the Diadem of Edward the Confessor. That this was the same one as used by Edward himself and later William the Conqueror and his successors is quite probable. An inventory of the Crown jewels by a monk at Westminster in the mid-1400s makes further reference to ‘an excellent golden crown’, along with other items apparently used at Edward the Confessor’s coronation, including ‘a tunicle…golden comb and spoon’, and for his wife, Edith, a crown, two rods, an onyx stone chalice and a paten. The spoon, along with the golden ampulla first used at the coronation of Henry IV to pour holy oil over the king, are two of the few pieces from the set that have survived.

King Alfred the Great with crown, from a statue

King Alfred the Great with crown, from a statue located in his home city of WinchesterPrecise references to the diadem’s existence can be found from Henry III’s coronation right up to the reign of Charles I. To confuse matters, there has been some suggestion that the Diadem of Edward the Confessor was renamed King Alfred’s Crown at some point following the dissolution of the monasteries. Prior to that point another crown, referred to commonly as Alfred the Great’s state crown, is also recorded as having existed. Descriptions are vague, but appear different enough to confirm the existence of two crowns. An early description of King Alfred’s state crown referred to it being ‘set with slight stones and two little bells’, while a parliamentarian named Sir Henry Spelman writing during the civil war referred to Alfred’s crown as ‘of very ancient work, with flowers adorned with stones of somewhat plain setting’. One of the few surviving accounts of the diadem states it was a ‘gold crown decorated with diverse stones’. Cromwell’s agents are recorded as having found at least three crowns in Westminster Abbey, Whitehall Palace and the 14th century Jewel Tower, whilst an inventory into the property of Edward II made reference to the existence of ten crowns.

The Jewel Tower - once part of the Palace of

The Jewel Tower - once part of the Palace of WestminsterAmong those might have been a series of rare finds from the reign of Edward I. In 1282, in preparation for his war against Edward I, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd deposited many of his jewels with the monks of Cymer Abbey. In 1284, with the war over, the jewels were handed over to Edward, including the ‘coronet Arthur’, a crown that supposedly belonged to the legendary king.Later in Edward’s reign, the Stone of Destiny was brought from Scotland and kept in the Tower following the King’s victory over William Wallace in 1296. The stone was added to the coronation chair, but the appearance of the stone that now resides at Westminster Abbey does not fit with the original description.

Charles I alongside the Tudor State CrownBy the reign of Henry VII another crown, commonly referred to as the Tudor State Crown, had been added to the collection. Descriptions of this have survived in greater numbers, and it has also been shown in a number of portraits. The frame of this crown was also gold and embedded with pearls, rubies, sapphires and diamonds. It was decorated with a figure of the Virgin Mary, at least three crosses and as many as four fleurs-de-lis. The Tudor Crown was independently valued as the most precious of the original jewels at approximately £1,100, worth just under £2m in the present day.

Charles I alongside the Tudor State CrownBy the reign of Henry VII another crown, commonly referred to as the Tudor State Crown, had been added to the collection. Descriptions of this have survived in greater numbers, and it has also been shown in a number of portraits. The frame of this crown was also gold and embedded with pearls, rubies, sapphires and diamonds. It was decorated with a figure of the Virgin Mary, at least three crosses and as many as four fleurs-de-lis. The Tudor Crown was independently valued as the most precious of the original jewels at approximately £1,100, worth just under £2m in the present day.

A copy of St Edward's

A copy of St Edward'sCrown, apparently created

using gold from the

original diademOf the original items only the ampulla, the spoon, the coronation chair and possibly some of the swords have survived. It is believed that gold from the Diadem of St Edward may have have been used in the construction of the new St Edward’s Crown – the official coronation crown that has been used at most coronations since that of Charles II, including Elizabeth II. According to the official receipts, the remainder of the jewels were destroyed; however, during the civil war, a story told that one of the original crowns, possibly the diadem, had been salvaged by a band of Cavalier soldiers, its whereabouts never divulged. Is it possible one of the original jewels could still exist, waiting to be discovered? The fate of the missing jewels is a central feature of The Cromwell Deception, available now from Amazon UK and US.

THE CROMWELL DECEPTION - OUT NOW

THE CROMWELL DECEPTION - OUT NOW