Brian Clegg's Blog, page 99

April 8, 2014

Designer error #1

I've always been fascinated by user interface design - the design of the way a person interacts with a product. It tends to be thought of as a computer software thing, but it applies to anything a person interacts with: a car, a fridge... even a door. And as soon as you design a user interface, you are open to designer error. When people try to use your product and get it wrong, the natural inclination is to think that they are idiots. But, in fact, I think of this as Designer Error #1, which is simply defined:

I've always been fascinated by user interface design - the design of the way a person interacts with a product. It tends to be thought of as a computer software thing, but it applies to anything a person interacts with: a car, a fridge... even a door. And as soon as you design a user interface, you are open to designer error. When people try to use your product and get it wrong, the natural inclination is to think that they are idiots. But, in fact, I think of this as Designer Error #1, which is simply defined:If someone uses your product incorrectly, it is your mistake, not theirs.I suffered from Designer Error #1 myself on one of my websites recently. But before getting to that, one or two of you may have a nagging doubt. Surely Designer Error #1 can't apply to a door? Does it make sense to talk about user interface design of a door? It certainly does. For quite a while, designers loved producing minimalist glass doors with no obvious hinge or handle. Often these were set in a large swathe of glass. And it would be discovered after their installation that no one could find the door. And when they did, they didn't know which side to open it. Often the post design fix was to resort to signage - but it would have been so much simpler if they had made the hinges visible or put a push plate on the door.

Another example of Designer Error #1 with doors was when British Airways built its swish new headquarters, Waterside. I spent an enjoyable half hour once watching this error in operation on the toilets there. The door into the toilets had a nice clear pull handle on it - a large vertical tubular bar type handle. And person after person would come up to the door and pull the handle. And nothing happened. Because you had to push the door to open it. The designer, it seems, loved symmetry (as they often do), and because there was a pull handle on the inside, put one on the outside too. Fail.

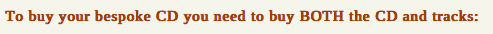

My Designer Error #1 came on my website www.hymncds.com which sells CDs and downloads of accompaniments to hymns. Most of the purchase are straightforward - you either buy CDs or you click through to download from the likes of iTunes and Amazon. But there is an option to order a bespoke CD - one where you choose the tracks from the circa 2,000 strong library and the CD is made to order. Because of the way the pricing works, there are two items required to buy a bespoke CD - a flat production/shipping cost, and a variable amount for the tracks, depending on how many you want. The website made this very clear with a label immediately above the purchasing buttons saying:

However, two purchasers within 24 hours simply paid for the tracks and didn't buy the CD itself, which then required an apologetic email asking for more money and general messing about.

The natural inclination is to think 'Can't they read?! It was obvious, in big letters!' But that's Designer Error #1. It was my fault. The ideal fix would have been to make it only possible to buy one with the other, but that isn't an option with the software I have. So instead I've made two changes. Rather than just have the instruction, then a string of purchase buttons, I have merged the two into a kind of action list:

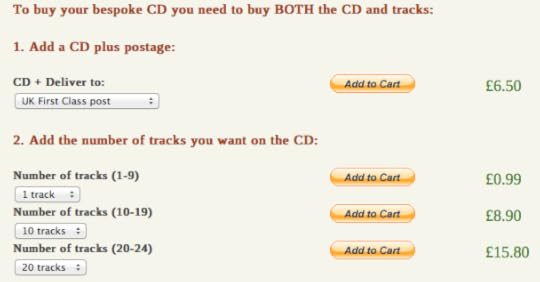

And then, if you do just add the tracks to your cart, you get a reminder there as well:

It's not perfect, but it's a heck of a sight better. If buyers still get it wrong, they are clearly silly. But it would still be Designer Error #1, and I would have to go back to the virtual drawing board.

Published on April 08, 2014 00:58

April 7, 2014

Beyond Flying review

I was delighted, if rather torn, by the opportunity to review about Beyond Flying, a book about the appropriate green response to air travel.

I was delighted, if rather torn, by the opportunity to review about Beyond Flying, a book about the appropriate green response to air travel.There were two reasons for being torn. One is that I think it is important to be green, and that climate change is a huge challenge facing us all - but on the other hand, most green organisations and their stances make me squirm. I am all too conscious that if it wasn't for the opposition of green pressure groups we would, by now, be generating most of our electricity from clean, green nuclear energy, which would have done far more to reduce our carbon emissions than fiddling about with flying habits.

The other way I'm a little divided is I worked for British Airways for 17 years, and keep a residual affection for the company and the airline business (not to mention having written Inflight Science ) - but at the same time I have only flown once in the last 20 years, which frankly puts most of the green polemicists in the book to shame. I dislike flying and more to the point, I don't see any need for it.

The book itself is in a format I'm not fond of - a collection of essays from different authors, rather than a single readable whole - but most of the essays are interesting and well-written. I didn't agree with them all, but I agreed with bits of many and they all made me think.

The message is varied. Some think we should just cut down on air travel, keeping to essential travel (like visiting a dying relative), others think we should try to cut it out altogether (though being uniformly liberal with a small 'l', I don't think many would want to impose this on everyone else). There is a lot about the joys of slow travel, how you see more of the world doing ground travel, and a lot about substituting videoconferencing etc. for business travel. What everyone agrees is that there is no sensible way to significantly reduce the environmental impact of air travel - we aren't going to get electric airliners - and we need to do something about it.

I thought it was worth pulling out some of the key points and giving my analysis.

It is important that we reduce air travel as it has a big impact on the environment. Probably not strictly true. As is pointed out in the book, air travel only produces around 5% of global emissions (I can't remember if this is factored for the higher impact produced because of the height the emissions are produced at.) If we stopped all flying overnight it would make very little difference to global warming. We need to hit the 95% not the 5%. Realistically, if everyone inclined to read a book like this made the change we'd probably reduce emissions by 0.001%. This is fiddling at the margins.If we made local (e.g. across Europe for us) rail travel more affordable, better and easier to book we could practically do away with local air travel. I absolutely agree. I don't know why anyone still flies to Paris when you can take Eurostar. We need far more of this kind of train travel. But to make this happen we do need good unified booking systems, and crucially cheaper rail travel. So remove the fuel subsidies from air and go back to serious subsidy of rail. And ignore the NIMBYs and get high speed rail like HS2 in place as quick as possible. Quicker than the current schedule. High speed rail is more comfortable, enjoyable, productive etc. etc. than flying. We just need to get rid of the barriers that remain and invest more.People should video conference more. Absolutely - I don't think there is any good reason to fly for business meetings or for conferences (scientists take note!). This includes, as some wryly point out in the book, all the global conferences about climate change and reducing its impact. The technology is there to do it cheaper and greener without flying. Interestingly, in the opening essay, someone from the New Internationalist magazine weasels out and finds excuses why journalists still need to fly. Sorry, no. You can't do 'One rule for us, one for the rest of you.' If you need someone on the spot, use a local. I'd apply the same to all news gathering organisations.There are different levels of need for flying. I think this is impossible to balance, because it is a value judgement that can't sensibly be made. You can't say 'this reason for flying is more valid than that' - or police that value judgement without having a totalitarian state. It's all or nothing.If people want to travel longhaul they should take a few months off and really enjoy travelling slowly. Bullsh*t. This illustrates the worst aspect of this book. So many of the articles assume we're all middle class people doing the sort of middle class job that can be done on a train (hence it's more productive) and that we can take a sabbatical from. Tell that to nurses and teachers and factory workers and waiters etc. etc. This just isn't in the real world. I love travelling places by train and have holidayed very successfully in Switzerland from the UK by train - but that's about the practical limit in the holidays most people can manage the time to do slowly. The vast majority of people will never be able to fit this 'few months off' picture.That last point in the list above illustrates the biggest problem of this book. The approach it advocates is only ever going to apply to such a tiny percentage of people, typically the chattering classes, that it can have no impact on climate change. But I do think we should be thinking about air travel, and particularly how we can make rail a better alternative, with some urgency - and for that I am grateful.

You can buy the book at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com - and all the usual green-friendly sources.

This has been a green heretic production.

Published on April 07, 2014 03:40

April 4, 2014

Peaking late

I'm a great enthusiast for Netflix - partly in terms of the range of interesting TV available (we're currently working through the original Swedish/Danish version of The Bridge, and Last Tango in Halifax for light relief) and just because of the impressive way it just works to do something that is quite amazing, when you think about it.

I'm a great enthusiast for Netflix - partly in terms of the range of interesting TV available (we're currently working through the original Swedish/Danish version of The Bridge, and Last Tango in Halifax for light relief) and just because of the impressive way it just works to do something that is quite amazing, when you think about it.Recently, though, I've dipped a toe into what used to be Lovefilm Instant, which I now get free through Amazon Prime. One of the advantages of watching Netflix is I can do so on a proper TV, using an Apple TV box, but that doesn't support Amazon's offering - luckily, though, our Blu-ray player does (ah, the wonders of modern technology). To be honest there's not a lot in the free stuff on Amazon I wanted to watch, but I was delighted to see one thing. When I first got Netflix, I'd noticed the classic David Lynch TV show, Twin Peaks was on there and duly put it on my 'to watch' list. To my horror, by the time I got round to it, Twin Peaks had dropped out of the library. But joy etc. - there it was on Amazon.

So over the last couple weeks I've had a Twin Peaksathon, watching both seasons with some serious binge viewing, something TP is ideal for. For those of you who remember it, it's still just as weird and wonderful as everyone said it was at the time - and holds up very well to the modern eye, apart from the 4:3 ratio. It's remarkable how much of a buzz it caused back then - even though I never watched it, I could remember from 1990 that the murdered girl was called Laura Palmer. For those who didn't see it, this starts off as what appears to be a straightforward murder mystery, featuring a very strange FBI agent (played wonderfully by Kyle MacLachlan - whatever happened to him?) - but ends up with strong elements of fantasy and downright strangeness.

I know the show was cancelled, so the ending might not have been exactly what Lynch would have hoped for the whole enterprise (and there is a movie prequel/sequel, though it sounds as if that doesn't exactly tie up loose ends), but it did illustrate for me the classic 'great urban fantasy issue.' I'm a huge fan of fantasy writer Gene Wolfe, not for his off-Earth stuff that seems to have made most of his money, but for the superb fantasies set in a not-quite-right real world like Castleview and There Are Doors. But if Wolfe has one flaw it is that he builds up such a weird and wonderful and intriguing complex scenario that the end of the book is almost always a disappointment. I suspected this would be the case with Twin Peaks... and it was. In spades.

Nonetheless, there are many characters in there I'll treasure (though I could have done without the one played by Lynch himself) and a story and setting that will haunt me for a long time. If you have access to it, and didn't see it first time around, I'd recommend giving it a go.

For fans, here's the theme music:

Image from Wikipedia

Published on April 04, 2014 00:20

April 3, 2014

The ride is rough with Lovelock

A couple of days ago, I mentioned James Lovelock's antipathy to peer review in his new book. The review of the book is now live on www.popularscience.co.uk and because I think it is a book worthy of wide exposure, I am reproducing that review here.

A couple of days ago, I mentioned James Lovelock's antipathy to peer review in his new book. The review of the book is now live on www.popularscience.co.uk and because I think it is a book worthy of wide exposure, I am reproducing that review here.James Lovelock is unique, both as a scientist and as a writer. He may be most famous for his Gaia hypothesis that the Earth acts as if it were a self-regulating living entity, but has done so much more in a 94 year life to date.

Rough Ride (not to be confused with Jon Turney’s Rough Guide to the Future ) is an important book, but it is also flawed, and I wanted to get those flaws out of the way, as I’ve awarded it four stars for the significance of its content, rather than its well-written nature. It is, frankly, distinctly irritating to read – meandering, highly repetitive and rather too full of admiration for Lovelock’s achievements. But I am not giving the book a top rating as a ‘well done for being so old’ award – far from it. Instead it’s because Lovelock has some very powerful things to say about climate change. I’ve been labelled a green heretic in the past, and there is no doubt that Lovelock deserves this accolade far more, as he tears into the naivety of much green thinking and green politics.

He begins, though, by taking on the scientific establishment, pointing out the limitations of modern, peer reviewed, team-oriented science in the way that it blocks the individual and creative scientific thinker – the kind of person who has come up with most of our good scientific ideas and inventions over the centuries. He does this primarily to establish that he is worth listening to, rather than being some lone voice spouting nonsense. I’m not sure he needs to do this – I think there are few who wouldn’t respect Lovelock and give him an ear, but it’s a good point and significant that he feels it necessary.

The main thrust of the book is to suggest that our politicians (almost universally ignorant of science) are taking the wrong approach to climate change. He derides the effort to develop renewable energy, despises the way the Blair government chickened out of nuclear power (and is very heavy on the Germans and Italians for their panic reaction after the Japanese tsunami) and makes it clear that from his viewpoint, our whole approach to climate change is idiotic.

With the starting point that the whole system is far too complex to allow any decent modelling, or to be sure what any attempts at geoengineering could achieve, Lovelock suggests that the answer is to let Gaia get on with sorting itself out, and instead of worrying about trying to manage carbon emissions in our current situation, we should instead put our efforts into adapting the way we live to cope with changes in the climate. He points out, the kind of climate we had before the industrial revolution (or accelerated evolution, as he believes it to be) was not the typical climate of the Earth either, which would be more like its state in the grips of an Ice Age.

Rather that trying to somehow get it back to an imaginary utopian state, he argues we should be looking at new ways to live that will enable us to manage despite what the climate throws at us. He points out, for instance, that in our fears of the impact of 2 to 6 degrees of warming we miss that Singapore manages perfectly well in an environment that is 12.5 degrees above the global average. Of course, you might argue that we couldn’t sustain that way of life for 7 billion people – and Lovelock is sanguine about this. He doesn’t expect humans to carry on at that kind of population level, as part of the adaptation.

What’s fascinating is that while reading the book I also read an article by that most demonised of environmental figures, Bjorn Lomborg, and it was remarkable how much similarity there was in their views of the approach we should take, though coming at the problem from very different directions and with very different predicted outcomes.

A final thrust of the book is perhaps less convincing. Lovelock, looking 100 million years or more into the future, suggests that the best way our descendants can survive to keep Gaia going is in electronic form, as it would be possible to live on for many more millions of years despite the Earth warming, due to the Sun’s gradual increase of output, to a stage where it is uninhabitable by biological life. At the same time he dismisses terraforming Mars (and doesn’t even consider starships) as a mechanism for keeping a future humanity alive. This seems a bit of an stance and dilutes, rather than helps the central message of what we should do about climate change and human existence on Earth.

As I mentioned earlier on, you may well find the book a frustrating read because of all the repetition, but this is a book that will really get you thinking about our approach to climate change, and whether we’ve got it all terribly wrong. Read it.

You can find out more about the book at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com, and it's also on Kindle at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

This has been a green heretic production

Published on April 03, 2014 00:31

April 2, 2014

Employment transformation

After George Osborne's recent enthusiasm for full employment there has been a lot around in the media about getting people into jobs, helping people find an employer and the ways that employers can be encouraged to get more people on their payroll. I do think there's an element here of the way the gas companies reacted to the electric light by trying to invent a better gas mantle.

My problem with all this is that you hardly ever hear anything about providing support to people to become self-employed. And yet, as dinosaur industries bite the dust, we can expect that more and more of us are likely to be self-employed. And I think that's a good thing. Having spent about half my working life with a large company and half self-employed there is no comparison. Being your own boss is wonderful, with the upside far outweighing the negatives.

So it's fine to have all this stuff, but why don't newly self-employed people get a national insurance holiday, like the one being offered for newly employed people? Why isn't there as much effort going into helping people set up their own businesses as there is in apprenticeships and encouragement to take on staff? The fact is that micro businesses are an extremely important part of the economy, but governments of all political colours are welded to the old idea of working for large companies as an employee being the only significant model.

Don't get me wrong. I'm not falling for the easy trap of 'I have got on okay for 20 years self-employed, so why can't everyone do it?' I know it's not for everyone. Some just want to clock in for a job, do the work and clock off. And there still will remain plenty of companies that need to be big, with lots of employees. But a sizeable part of the workforce is self employed, or runs their own extremely small companies - and that part could and should grow considerably.

Self employment and startups really are by far the best solution when a dinosaur industry dies out. Yet despite whatever weasel words there may be from the government (and from Labour), the fact is that politicians just don't get it. Our whole system (especially the tax system) is set up to support and reinforce the old way of working. It's time for a radical redesign, and to really give help to those who want to earn money by their own efforts. How about it, Mr Osborne?

Published on April 02, 2014 01:10

April 1, 2014

End of the peer show

I am currently reading for review the latest book by James Lovelock, and a strange and sometimes wonderful thing it is too. I was fascinated to read fairly early on an impassioned attack on something most of us take for granted as part of the mechanism of modern science - peer review.

I am currently reading for review the latest book by James Lovelock, and a strange and sometimes wonderful thing it is too. I was fascinated to read fairly early on an impassioned attack on something most of us take for granted as part of the mechanism of modern science - peer review.The idea of peer review is that before a paper is published or an experiment etc. is funded a group of other scientists (the peers in question) with appropriate knowledge assess the value of the paper/experiment and act as gatekeepers, only allowing through work they feel is worthwhile. But Lovelock points out that this process tends to support the status quo, rather than radical new thinking, and is heavily biassed in the way it is operated towards the 'throw large teams at it' approach that emerged largely in the Second World War and is strongly weighted against individual scientists working on their own, which, he suggests, is a problem.

Lovelock points out, correctly, that only individuals can come up with an idea. You can't have an idea by committee. (It's interesting, we use 'team' when we want to make the concept of throwing a group of people at a problem to sound good, and 'committee' when we want it to sound bad.) It's not that he's against teams, but he sees them as largely responsible for the grunt work to support the ideas from the individuals. And this is fine and good, but unfortunately the peer review process has come to assume a certain way of working, and will tend to reject without consideration input from individuals who don't fall within the classic academic institution model.

One of the examples used to support this is an experience Lovelock had in the early days of the CFC/ozone hole debacle. Lovelock had applied for a small grant from the Natural Environment Research Council as part of a plan to travel on a ship to Antarctica and back, using a device he had invented that enabled him to measure the levels of CFCs in the atmosphere down to parts per trillion. The peer review included this wonderful piece of text:

Every schoolboy knows that the CFCs are among the most inert of chemicals, it would be difficult to measure their abundance in the air, or in sea water, as low as a part per million; the proposer claims to be able to measure their abundance at parts per trillion. The claim is bogus and the time of our committee should not be wasted by frivolous applications of this kind.Lovelock made the journey and took the readings unfunded, providing the primary evidence that would result in the eventual banning of CFCs. The more common form of peer review, deciding on whether or not a paper should be published in journals, he suggests, is equally biassed against anything new/outside current received wisdom/from individual scientists working alone - it's just rare that the negative comments get seen.

There is no doubt that Lovelock is right, but unfortunately what he doesn't do (unless it comes later in the book - I am only part way through) is come up with a solution to the problem. Because the fact is that there are far more people who really will be making bogus claims and coming up with silly papers than happen to be effective individual scientists like him. But at the very least, the processes should allow for an individual who, like Lovelock, has the appropriate qualifications and experience to be published or funded just as much as those who are part of academic institutions. (Admittedly there aren't many such people, but there are still a few.) At the moment this just doesn't happen.

What's more, I do think Lovelock has a point when he suggests that the vast majority of new thinking and new inventions come from such individuals, rather than from big teams. The way we go about science now is very conservative (with a small c). Which is fine where things can continue in 'more of the same' mode, but when we need a radical idea to overthrow current thinking - or for a really impressive new invention (Lovelock stresses most of the great scientists have also been inventors, something big team science doesn't seem capable of matching) - then we are likely to be moribund if we don't find a way to support these maverick individuals. Science will, frankly, be a poor cousin of what it could be otherwise.

Published on April 01, 2014 01:02

March 31, 2014

Poor old Andrew

I feel a bit sorry for Andrew Lloyd Webber. Only a bit, you understand. But he is probably feeling a bit depressed about his latest musical, Stephen Ward, which closed at the weekend after running for less than four months with so-so ticket sales.

I feel a bit sorry for Andrew Lloyd Webber. Only a bit, you understand. But he is probably feeling a bit depressed about his latest musical, Stephen Ward, which closed at the weekend after running for less than four months with so-so ticket sales.It perhaps wasn't the most inspired of choices for the subject of a musical. Outside the UK no one is likely to have heard of the Profumo affair, and even here, what was once a national scandal has become a vague, faded memory. Yet there is no doubt that there was an interesting story there.

We went to see Stephen Ward on Friday, its penultimate day, and I'm glad we did. It was no Cats or Phantom of the Opera. It wasn't packed full of memorable tunes. It only really had one lyrical song, though there were a couple of distinctly effective pieces (even if the one for the orgy scene is worryingly reminiscent of Bustopher Jones in White Spats in places - though ALW has always had a habit of reusing musical flourishes). Notable was the opening song, Human Sacrifice, with its bizarre setting of the Blackpool chamber of horrors, an extremely atmospheric piece. All in all, though, it was an effective evening's musical theatre. And as well as making for an enjoyable outing, it did really make you think about the hypocrisy of the establishment in the early 60s.

I would much rather go to a fine but not flashy work like this than a large scale 'musical' that is just a rehash of existing pop songs in a strung-together storyline like Mamma Mia or We Will Rock You. At least this was original music, written for this story, and producing a whole with a degree of integrity. So while I can understand why Stephen Ward wasn't a hit - and I would have been reluctant to have paid full price to see it - I think that it deserved to have been seen by rather more people. And that genuinely does make me feel the teeniest bit sorry for our Andrew.

Published on March 31, 2014 00:15

March 27, 2014

Georgia on my mind

Like pretty well everyone else in Europe (and most of the rest of the world) I am always totally baffled by the American attitude to guns. I have friends in the US who are lovely, kind people, who will defend to the hilt their constitutional right to bear arms, and given the record of gun killings the country has, this seems bizarre. But I always hold off commenting, because in the end, it's not my country it's not up to me to decide what their laws are, or whether a constitutional amendment designed to allow for militias should apply to the general public in everyday life.

However, one thing is very clear now. Given the new gun laws there, I will certainly never be visiting Georgia. Now admittedly this was pretty unlikely, as I have only flown once in the last 20 years - it's not something I do very often, so I am unlikely to visit the US at all. But while I don't think it's down to me to criticise the decision to allow ordinary citizens to carry guns in bars, restaurants, churches, airports (airports?!?!), libraries, sports grounds, youth centres and primary school classrooms, I do think it is entirely fair for me to say there is no way I am going to set foot in a place where everyone in the restaurant I pop into for a meal could carrying loaded guns.

Of course, those who are in favour of carrying weapons will point out that these guns are purely defensive. As long as I don't do anything I shouldn't, I'll be fine. But hold on. Remember this combines with the 'Stand Your Ground' law, which allows those gun-toting citizens to defend themselves with deadly force if they feel they are threatened with serious harm. So I don't have to pull my own weapon (which, of course, I wouldn't have) to get shot. Someone from a very different cultural background merely has to misread my body language, or way of speaking in a way that makes them feel they are threatened and they can shoot me down. I am not prepared to take the risk.

Now over here in the UK, we are always saddened when Americans stop coming to Europe in their droves if there is a terrorist attack. It seems an over-reaction. So is my response here a matter of double standards? I don't think so. When an attack occurs it is a one-off, undertaken by extremists who are likely to be dead or captured afterwards. If anything, a country is safer to visit after an attack than it was before - and the chances of being in a place where one will happen is extremely tiny. But in Georgia we aren't talking about a handful of individuals being dangerous on one specific occasion, but potentially every adult I come across every minute of the day - and what's more, the law supports them being able to shoot me and get away with it. Is this going to ensure they don't pull the trigger if they get a little irritated? Again, I'm not prepared to take the risk.

Sorry, America, I love you dearly, but Georgia is on my mind for all the wrong reasons.

However, one thing is very clear now. Given the new gun laws there, I will certainly never be visiting Georgia. Now admittedly this was pretty unlikely, as I have only flown once in the last 20 years - it's not something I do very often, so I am unlikely to visit the US at all. But while I don't think it's down to me to criticise the decision to allow ordinary citizens to carry guns in bars, restaurants, churches, airports (airports?!?!), libraries, sports grounds, youth centres and primary school classrooms, I do think it is entirely fair for me to say there is no way I am going to set foot in a place where everyone in the restaurant I pop into for a meal could carrying loaded guns.

Of course, those who are in favour of carrying weapons will point out that these guns are purely defensive. As long as I don't do anything I shouldn't, I'll be fine. But hold on. Remember this combines with the 'Stand Your Ground' law, which allows those gun-toting citizens to defend themselves with deadly force if they feel they are threatened with serious harm. So I don't have to pull my own weapon (which, of course, I wouldn't have) to get shot. Someone from a very different cultural background merely has to misread my body language, or way of speaking in a way that makes them feel they are threatened and they can shoot me down. I am not prepared to take the risk.

Now over here in the UK, we are always saddened when Americans stop coming to Europe in their droves if there is a terrorist attack. It seems an over-reaction. So is my response here a matter of double standards? I don't think so. When an attack occurs it is a one-off, undertaken by extremists who are likely to be dead or captured afterwards. If anything, a country is safer to visit after an attack than it was before - and the chances of being in a place where one will happen is extremely tiny. But in Georgia we aren't talking about a handful of individuals being dangerous on one specific occasion, but potentially every adult I come across every minute of the day - and what's more, the law supports them being able to shoot me and get away with it. Is this going to ensure they don't pull the trigger if they get a little irritated? Again, I'm not prepared to take the risk.

Sorry, America, I love you dearly, but Georgia is on my mind for all the wrong reasons.

Published on March 27, 2014 01:46

March 25, 2014

Review - Among the Creationists

Subtitled 'dispatches from the anti-evolution front line', Jason Rodenhouse's book is a fascinating look at creationism from the outside. Rather than simply poke fun at silly creationist ideas, a game that palls rather quickly, Rodenhouse attends creationist and ID (Intelligent Design) conferences, visits centres and generally immerses himself in the culture, in particular its interface with science. While he does this from the point of view of an atheist, he is respectful of those he is meeting with, and in return, repeatedly emphasises that even when he asks difficult questions after a lecture, he his treated with warmth and kindness, rather than booed and heckled.

Subtitled 'dispatches from the anti-evolution front line', Jason Rodenhouse's book is a fascinating look at creationism from the outside. Rather than simply poke fun at silly creationist ideas, a game that palls rather quickly, Rodenhouse attends creationist and ID (Intelligent Design) conferences, visits centres and generally immerses himself in the culture, in particular its interface with science. While he does this from the point of view of an atheist, he is respectful of those he is meeting with, and in return, repeatedly emphasises that even when he asks difficult questions after a lecture, he his treated with warmth and kindness, rather than booed and heckled.In effect, the book has two different types of chapter. Some delve into the detail of creationist and ID beliefs and make strong efforts to see if there is a way to justify them. The only trouble with these chapters is that, even though they always end up coming down against the creationist view, it can be a bit like reading a theology or philosophy textbook - it gets a little stodgy sometimes. By contrast, the book really livens up with the other chapters, which describe Rodenhouse's experiences, what he witnesses at the events and the creationist centre he visits, and the conversations he has with creationists (including a fairly heated one in a queue for a Subway sandwich).

If you read this hoping to find that Rodenhouse changed his opinion - or managed to change the opinion of a single creationist - it isn't going to happen. But if you come at it from an atheist viewpoint (as I suspect most of the readers will), you will learn a lot more about what creationists believe and why - often because of being presented with distorted facts - and if you come at it as a Christian, you may find some uncomfortable thinking is generated by its careful arguments. More so, in fact, than from the polemic school of Dawkins, Hitchens et al.

The only chapter I wasn't totally happy with was the one entitled 'Why I love being Jewish,' which suffered a bit from American parochialism. Rodenhouse classes himself as a cultural but non-religious Jew. He enjoys Jewish culture and ritual without believing in God, and seems to suggest that this is something unique about Judaism. However, in the UK I'd say that I have come across a similar approach to a good few religions - Hinduism, for instance - and especially in the UK in the form that Astronomer Royal Martin Rees describes himself as a 'Church of England agnostic' - again, someone who enjoys the culture and ritual without having a religious belief.

Overall an interesting book if you really want to get to grips with why creationism is so strong in the US. See more at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Published on March 25, 2014 04:46

March 24, 2014

In this respected science author Brian Clegg

I use a program called Mention to keep an eye on references to my books etc. online, and just occasionally it pulls up something that boggles the mind. Here I am in one of those weird pages that assemble text randomly from the internet for bizarre search engine purposes:

I just love the surreal nature of that second reference.

I just love the surreal nature of that second reference.

Published on March 24, 2014 01:44