Brian Clegg's Blog, page 66

September 16, 2015

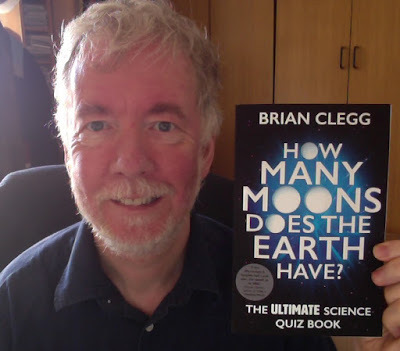

Brian lassos the moon

It doesn't matter how many books you have published, there's still something special about getting your hands on the first copy of the finished product - and never more so than my new book, How Many Moons Does the Earth Have?, as the publisher, Icon Books, has done a great job, giving it a really impressive textured cover.

It doesn't matter how many books you have published, there's still something special about getting your hands on the first copy of the finished product - and never more so than my new book, How Many Moons Does the Earth Have?, as the publisher, Icon Books, has done a great job, giving it a really impressive textured cover.Sadly, you can't buy a copy yet - not til November - but you can already preorder it on Amazon and elsewhere, and I think it will make an ideal gift for hard-to-buy-for people (and something of a bargain at £6.99). In fact there may be one exception to this wait - I'm doing an event at Lichfield Literary Festival on October 8 when we hope there will be early copies available on sale: see the festival's website for details.

It's a science quiz book, in part because if you like attending quizzes, it can be frustrating that they don't have enough/good enough quality science questions. But you don't need to be running a quiz to use it (in fact I suspect most readers won't) - the idea is rather to test yourself with the questions and then turn the page to find the answer, often, I hope, surprising, and a pageful of interesting material expanding on the answer.

It's a bit like taking part in your own version of QI without the pompousness and the answers they get wrong (which is reflected in the title of the book).

Here's some bumf from the back cover:

... and award yourself a small pat on the back if you recognise the movie reference in the post title.

Published on September 16, 2015 01:06

September 15, 2015

Is this the end of complementarity?

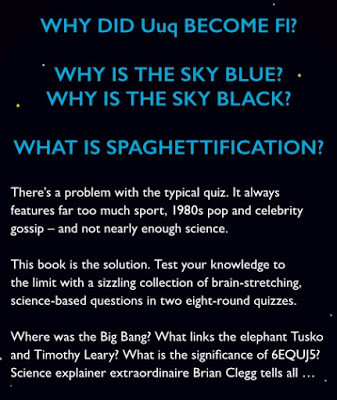

Image © EPFL 2015We have a report from the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) of 'a photograph of light as both a particle and a wave.' HT to Ian Bald for pointing this out - the paper dates back to March, but I didn't spot it at the time.

Image © EPFL 2015We have a report from the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) of 'a photograph of light as both a particle and a wave.' HT to Ian Bald for pointing this out - the paper dates back to March, but I didn't spot it at the time.It's interesting to dig in a bit and see a) is this true and b) is it the end of Bohr's assertion as part of his concept of complementarity that light could act like a wave or a particle but never both at the same time?

The experiment is complex enough that it's a little fuzzy when it comes to the interpretation. What the experimenters did was reported by the EPFL's press people as follows. The experimenters fired a laser at a metallic nanowire. Some of the energy from the photons in the light stimulated electrons in the wire, which meant that 'light' travelled along the wire in two directions. When these waves met they formed a standing wave which generated emitted light. They then shot electrons at the wire which interacted with the emitted light in a quantum fashion, slowing down or speeding up and producing the rather pretty image.

The argument in the press release is that this simultaneously demonstrates the wave and particle nature of the light - the wave in the standing wave and the particle aspect is in the interaction with the incoming electrons that produces the image.

This is a really interesting experiment. As Fabrizio Carbone, the leader of the EPFL team says, 'This experiment demonstrates that, for the first time ever, we can film quantum mechanics – and its paradoxical nature – directly. Being able to image and control quantum phenomena at the nanometer scale like this opens up a new route towards quantum computing.' However I'm a bit hesitant to say that we are simultaneously observing wave and particle behaviour in the same bit of light.

Unless I'm misunderstanding what's going on, we have waves in the nanowire, which strictly speaking are plasmonic, i.e. quantised vibrations rather than themselves conventional electromagnetic waves. These waves are causing electrons in the wire to accelerate, generating photons which are emitted and then interact with the incoming detector photons. So the wave-like process is generating the photons. But they are totally different entities. Of itself this kind of mix isn't uncommon - wave-like behaviour in a radio aerial generates the photons of the emitted radio - but being able to see the impact of both in the same image is. So complementarity is safe.

Whatever the correct interpretation, we must not fall into the trap of confusing models with reality. Light is not a wave, nor is it a particle (nor is it a fluctuation in a quantum field) - these are models that help us get a grasp of its behaviour, but in the end light is light, where waves, particles and fields are all models based on our experience of the macro world. However, it's certainly interesting stuff! You can read the full paper here.

Published on September 15, 2015 00:47

September 14, 2015

On a Bacon hunt

Roger Bacon is a misty figure in the history of science. Over the years, this thirteenth century friar has been portrayed as a mystic, magician, scientist ahead of his time and second rate collector of other people's ideas. It doesn't help that he often gets confused with his unrelated (as far as we are aware) Elizabethan namesake Francis Bacon. But it is in part because of the messy way that Roger has been reported over the years (even starring in a play by one of Shakespeare's contemporaries) that he is a fascinating subject.

Roger Bacon is a misty figure in the history of science. Over the years, this thirteenth century friar has been portrayed as a mystic, magician, scientist ahead of his time and second rate collector of other people's ideas. It doesn't help that he often gets confused with his unrelated (as far as we are aware) Elizabethan namesake Francis Bacon. But it is in part because of the messy way that Roger has been reported over the years (even starring in a play by one of Shakespeare's contemporaries) that he is a fascinating subject.My book on Bacon and his science has an intentionally provocative subtitle. I ought to make it clear that in many ways he clearly wasn't the first scientist. Apart from the impossibility of coming up with a 'first' and the argument that you couldn't have a scientist before the word was coined (a terrible argument to my mind - you might as well say there weren't dinosaurs before the word was coined), Bacon was pretty bad on most of the requirements to call someone a scientist. But he did try most of them. He emphasised the essential contribution of maths long before it was fashionable (Francis wasn't impressed with maths, for instance), Roger went on at great length about the importance of experiment, rather than relying on received wisdom, he risked his life to communicate science and he was a scourge of those who claimed to be magicians (ironic, given that he would later be regarded as one himself). Bacon was pretty bad on scientific matters, but the reason I do give him this tongue-in-cheek label is that I would expect an early person to fit a label to be bad at the role. By the time you get to Galileo and Newton they were far too polished.

But the point of this post isn't to put the case for Bacon, which was never intended to be taken too seriously. Instead it's a chance to share some photos of an attempt to track down Bacon in his main academic home, Oxford. He was in Oxford when the university was just beginning, both as a member of the university and of the Franciscan friary there. I did find a few traces of Bacon - but you might think there'd be a little more.

But the point of this post isn't to put the case for Bacon, which was never intended to be taken too seriously. Instead it's a chance to share some photos of an attempt to track down Bacon in his main academic home, Oxford. He was in Oxford when the university was just beginning, both as a member of the university and of the Franciscan friary there. I did find a few traces of Bacon - but you might think there'd be a little more. Admittedly he gets a lane, suitably small and near the sprawling location of the Franciscan friary, mostly now brutalist overpasses and uninspiring modern buildings. According to legend, at some point he had a study in the building that spanned Folly Bridge on the southern approach to the city. The building certainly existed, though there was no reason to link it to Bacon.

Admittedly he gets a lane, suitably small and near the sprawling location of the Franciscan friary, mostly now brutalist overpasses and uninspiring modern buildings. According to legend, at some point he had a study in the building that spanned Folly Bridge on the southern approach to the city. The building certainly existed, though there was no reason to link it to Bacon.But that structure is long gone. It narrowed the bridge to a single track and was totally unsuited to modern traffic. Now the bridge is an uninspiring bit of architecture you could drive over without even realising you were on a bridge.

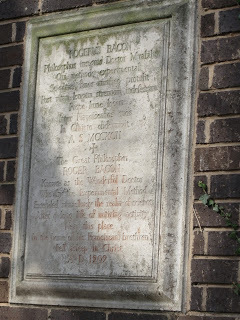

But surely Oxford could not fail to mark the presence of one of its few chances to eclipse Cambridge in the scientific field? There is indeed a plaque to Bacon in Latin and English, reflecting his one-time label of Doctor Mirabilis.

Unfortunately, the siting of the plaque could be better. It is on the side of a multi-storey car park, another of Oxford's delightful replacements for the friary:

Still, there is one place where it feels as if Bacon is being given his due. Oxford's gorgeous natural history museum contains a series of statues of scientific figures, and there, amongst the skeletons, is Roger in all his glory. Of course we've no idea what he looked like, but I think it's right that he should be remembered.

Update: I gather the car park with the plaque is being demolished (my visit was last year). Any Oxford locals know what is happening to the plaque?

Published on September 14, 2015 00:31

September 9, 2015

Review - Cover-Up Woodback phone case

I like to ring the changes with my phone cases, so I was pleased to have the chance to review the Cover-Up Woodback iPhone 6 case.

I like to ring the changes with my phone cases, so I was pleased to have the chance to review the Cover-Up Woodback iPhone 6 case.In principle, a phone case can do three things for a phone - make it look better, protect it and make it feel better to hold - and how well the Cover-Up case comes across depends on how you react to each of these three criteria.

In this case, the appearance can split the jury. I rather like the real wood finish, with one proviso. Some younger observers have not been so impressed, preferring being able to see the attractive back of the iPhone and not entirely sure about the merits of wood on hi-tech equipment.

The wooden back to the case gives it a genuinely interesting and different look - in my case it was a red wood called Purpleheart, which was an attractive shade. The only proviso is that, like most people my age, I remember the horrendous plastic wood-effect finish that manufacturers (particularly US manufacturers) used to splash everywhere. Though it's obvious this is the real deal when you look at it properly, at a glance it could be reminiscent of those 1970s monstrosities.

Then there's protection. A smartphone is worth hundreds of pounds, yet it gets slung around as if it's indestructible. The good news is that the Cover-Up does a great job of protecting the back and sides of the phone against scratches. What it doesn't do is protect the screen - the bumpers on the side don't come high enough to get between the screen and the pavement if you drop it.

Where the case scores highest is in feel. It's very light, so doesn't make the phone feel like a brick, and has silky-touch sides, while the finger that rests against the wooden back feels far better than it does against smooth plastic of my usual case. It's probably the nicest case to hold I've ever had my hands on.

Where the case scores highest is in feel. It's very light, so doesn't make the phone feel like a brick, and has silky-touch sides, while the finger that rests against the wooden back feels far better than it does against smooth plastic of my usual case. It's probably the nicest case to hold I've ever had my hands on.So if you want screen protection it's not a good bet, but otherwise, providing the wood finish appeals to you (it has definitely grown on me), it's a great little case.

You can find out more about the case (and the various woods available for the back) at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Published on September 09, 2015 01:42

September 8, 2015

Operational what?

For a good number of years I was employed in Operational Research (OR). There was a running joke among those involved in the discipline at British Airways featuring a conversation at a party.

For a good number of years I was employed in Operational Research (OR). There was a running joke among those involved in the discipline at British Airways featuring a conversation at a party.Someone asks you what you do and, after about five hilarious attempts to explain it, the person in the joke says 'I work with computers.' These days my attempt at a short explanation is something like 'it was developed during the Second World War as a way of using maths to do things like calculate the most effective pattern to drop depth charges. But now it's used by organisations to solve business problems.'

The little squeezy plane above is from an anniversary get-together which I'm shocked to realise was three years ago. But I've had more recent OR action from a connection with Lancaster University, where I took my MA in OR many moons ago. I visited the university a year or so ago as part of its 50th anniversary celebrations and was delighted to meet up with one of my old lecturers, Graham Rand. As well as showing me around, he mentioned that the Operational Research Society was starting a new magazine called Impact which would be featuring articles on what's happening in today's OR.

I've contributed a couple of articles for the magazine, which has given me a great opportunity to revisit OR and find it still live, well and doing interesting things. The magazine is aimed at the general reader, rather than practitioners, so well worth a look. Fittingly, the first piece I wrote for them, featured on the cover of the first edition, is about a current use of OR in British Airways.

Published on September 08, 2015 01:25

September 7, 2015

Lessons on using Twitter customer service

A lot of companies now offer quick and easy customer service response via Twitter. If in doubt these days, if I'm moaning about a company (or praising one for that matter) I will include their Twitter address in my tweet, and many will respond within minutes or hours.

A lot of companies now offer quick and easy customer service response via Twitter. If in doubt these days, if I'm moaning about a company (or praising one for that matter) I will include their Twitter address in my tweet, and many will respond within minutes or hours.I think this is a good thing - as long as it's done well. I've had some really zippy and helpful responses. But sometimes a company is far too slow in responding. At other times, even if the company responds quickly, it doesn't exactly do itself any favours.

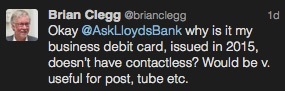

I used Twitter to bring the above moan to the attention of my bank. Lloyds makes it clear just how much it regards Twitter as a way to ask it questions from the name 'AskLloydsBank.' It seemed a reasonable question - I've a relatively new business debit card, yet when I buy stamps or travel by tube, for instance, I can't use my card to pay contactless.

Back came the reply within an hour or so:

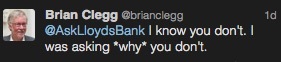

Well, I suppose it was nice to know I was dealing with CL. (No, it wasn't. I didn't really care.) But have you spotted what (s)he did? Answered my question by telling me what I already knew. Not exactly top quality stuff. So, subtle as ever, I replied:

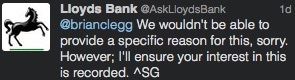

To be fair to the Lloyds staff, at this point the actually read the question. (It's not just Lloyds. As anyone who has ever tried to use Amazon, eBay or Paypal customer service will know, they never read the question properly first time, churning out a knee-jerk reply.) Unfortunately, the response was not one to cheer my heart:

So there you have it. They can't provide a reason. Now, do you think that leaves me a happy customer? No. Twitter is genuinely a great medium for customer service - but in cases like this it proves worse than useless, and the company ends up looking worse that it did before responding. What's more, bearing in mind Twitter is a broadcast (these weren't PMs) they did it for the whole world to see.

Lessons? Yes, use Twitter for customer service. Yes, get back to your customers promptly. But read their questions first time. And if you can't give an answer, give the customer an easy mechanism to escalate the query. 'We wouldn't be able to provide a specific reason,' just isn't good enough.

Published on September 07, 2015 01:08

September 4, 2015

Review - The Alteration

I've come back to this book after a couple of decades and it still holds up well as one of the two great alternative history books where there is no Reformation in Europe, leaving the Catholic church with a stranglehold that limits the development of science, technology and society (the other, of course, is Keith Roberts' lyrical Pavane).

I've come back to this book after a couple of decades and it still holds up well as one of the two great alternative history books where there is no Reformation in Europe, leaving the Catholic church with a stranglehold that limits the development of science, technology and society (the other, of course, is Keith Roberts' lyrical Pavane).The central theme to The Alteration is whether a ten-year-old boy with a superb singing voice should be turned into a castrato to preserve that voice for life at significant cost for the boy - but Kingsley Amis has immense fun with many references to familiar people, books and events, seen in the different light of the tightly Catholic Europe. The strange mix of Tudor and 1970s is done beautifully and atmospherically, as are the many differences between their world and ours (though it's never properly explained why Cowley, now known as Coverley, is the capital, rather than London). There are Protestants in this world - but they are mostly limited to New England, which despite being arguably better than Europe has its own problems.

Altogether a rich and delightful book with enough varied topics (the passage of child to adult, for instance, and the nature of being 'gifted' as well as the obvious social and religious themes) to engage anyone. I do have two issues. The minor one is that it is written in a language that is modern, but with a period feel to deepen that Tudor/1970s mix - which is fine, but distances the reader a little. The rather bigger one is the major plot twist in the final segment of the book - I won't give it away, but this is a twist that will not only have a fair number of readers wincing, but that is so improbable in the context that it makes the ending seem contrived. I understand what Amis is doing here, but he should have found a different way to do it.

Despite that, though, this is a great example of that wonderful mix of science fiction and historical fiction that is an alternative history, and well worth a try.

You can find out more about the book at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Published on September 04, 2015 01:45

September 3, 2015

Literary lunacy

There has been considerable negative reaction to an article by someone I've never heard of called Jonathan Jones in The Guardian who tells us to 'Get real,' because 'Terry Pratchett is not a literary genius.' Jones goes on to say 'I have never read a single one of his books and I never plan to.' Why? Because 'life is too short to waste on ordinary potboilers - and our obsession with mediocre writers is a very disturbing cultural phenomenon.'

There has been considerable negative reaction to an article by someone I've never heard of called Jonathan Jones in The Guardian who tells us to 'Get real,' because 'Terry Pratchett is not a literary genius.' Jones goes on to say 'I have never read a single one of his books and I never plan to.' Why? Because 'life is too short to waste on ordinary potboilers - and our obsession with mediocre writers is a very disturbing cultural phenomenon.'Some have suggested that Jones is indulging in the popular Katie Hopkins method of trying to become famous by irritating people. (If so, it hasn't really worked as it's just his bile and not his person that has reached public awareness.) But I don't think they are right. Instead what we have here is classic literary fiction jealousy of popular fiction.

The attitude is wondrously condescending and amounts to 'Only the fiction I like is worth reading, because it changes lives and enriches the soul whereas your rubbish just entertains the masses.' I'm sorry, I very rarely resort to offensive language, but this is bollocks. There's plenty of literary fiction that is, frankly, boring, unreadable self-promoting trash. It's showing off that is being passed off as art.

All written work (and art for that matter) is communication. If the work fails to communicate to the reader, it is more the fault of the author than the reader, unless what's getting in the way is changing language. The only thing that stops Shakespeare being instantly accessible is they way that language has changed considerably, but if you can overcome that, you don't have to work at getting Shakespeare - it gets you. Viscerally. But I suspect most of the authors Jones would champion with the obvious exception of Jane Austen (and unlike him, I have read some of the authors in question) present quite the reverse picture. They are poor communicators who are more interested in an artistic turn of phrase and piling on the painstakingly implausible angst than linking to the reader.

In one sense Jones is right. Pratchett wasn't a genius. His writing style is closer to P. G. Wodehouse than Shakespeare. But as well as Shakespeare and Austen, give me Pratchett (or Wodehouse, or Bradbury, another author Jones attacks) any day over the pretentious twaddle that Jones no doubt considers literary genius. Because writers like Pratchett and Bradbury knew their craft. They knew how to draw in a reader and get into their minds. And they have influenced and enriched far more lives than Jones' literary elite ever could.

Published on September 03, 2015 01:06

September 2, 2015

Fun with vanadium oxides

In my latest podcast for the RSC's Chemistry in its Element series I take a look at the assorted oxides of vanadium.

In my latest podcast for the RSC's Chemistry in its Element series I take a look at the assorted oxides of vanadium.Vanadium, the transition metal at number 23 on the periodic table, is one of those elements that sounds more like something out of a superhero movie than a real substance. You might expect that vanadium oxide would be of vanishingly small interest, but the reality is different. I should really have said the vanadium oxides, because thanks to vanadium’s five valence electrons there are enough oxides to sound like a successful Hollywood franchise – vanadium (II) oxide, VO, vanadium (III) oxide, V2O3, vanadium (IV) oxide, VO2 and vanadium (V) oxide, V2O5, without going into extra intermediate phases that can produce entertaining combos like V6O13 and V8O15.

Also like those Hollywood franchises, some instalments are more interesting than others, as you'll discover by taking a listen...

Published on September 02, 2015 02:50

September 1, 2015

Corbynistics

There's nothing like politics to bring out lies, damned lies and statistics, and we have to be particularly careful when throwing around percentage figures when commenting on political figures, their supporters and their views. Recently published YouGov data compares the views of the supporters of different contenders in the Labour leadership election, and it is ripe with possibilities for statistical misrepresentation, if those reporting it aren't careful and have trouble with numbers.

There's nothing like politics to bring out lies, damned lies and statistics, and we have to be particularly careful when throwing around percentage figures when commenting on political figures, their supporters and their views. Recently published YouGov data compares the views of the supporters of different contenders in the Labour leadership election, and it is ripe with possibilities for statistical misrepresentation, if those reporting it aren't careful and have trouble with numbers.I was brought to this observation by the blaring headline above from that intellectual powerhouse, Shortlist magazine. (Sorry, the snide factor just slipped up accidentally there.) The reason the headline made me want to dig deeper into the numbers were that, of itself, this headline doesn't tell us anything, because there's nothing to compare with. Is that a lot? Perhaps 50 per cent of the British people believe the world is run by a secret elite and the Corbynites are unusually rational. As it happens, that's not true, but the comparative figures make more interesting reading.

To give Shortlist their due, they did link to their source at YouGov, which meant those figures were available. Note, by the way, that these were the percentages who selected 'Strongly agree', of which more later:

Strongly agree to 'The world is controlled by a secretive elite'

Corbyn Supporters: 28%

Burnham Supporters: 19%

Cooper Supporters: 16%

Kendall Supporters: 7%

All GB: 13%

So the Corbynites are somewhat more paranoid and liable to believe in controlling conspiracies, which isn't particularly surprising - in fact for me it was rather more surprising that Andy Burnham and Yvette Cooper's supporters were also above average. Note, also, by the way that Shortlist's headline subtly changed what the elite were, from secretive to secret, which isn't quite the same thing.

However, for me, the more interesting statistic was another one that Shortlist picked out. They highlighted that Corbyn supporters were much more in favour of nationalisation of the railways than the country 'with 86 per cent wanting this reform, compared to 31 per cent of the public.' (Actually they conflate railways and the health service, where the percentages aren't identical, though similar, while the figures they quote aren't quite either of these.) This confused me as the Corbyn supporters who seem to dominate parts of my Facebook and Twitter feeds are always telling me the public is in favour of nationalisation of the railways.

So I took a look at the YouGov page and what it says makes it clear that Shortlist's analysis is not necessarily true. Here's the YouGov result:

STRONGLY support nationalisation of the railways:

Corbyn Supporters: 86%

Burnham Supporters: 68%

Cooper Supporters: 72%

Kendall Supporters: 46%

All GB: 34%

Leaving aside the 34/31 difference, doesn't this support Shortlist's claim? Not necessarily. Let's imagine the question and the 'all GB results' were something like this:

What is your attitude to nationalisation of the railways?

Strongly support: 34

Slightly support: 25

Neither/don't know: 21

Oppose: 10

Strongly oppose: 10

Which, as it happens, I can tell you they were, as YouGov very kindly responded within minutes to a request for more data. Given these numbers it would be madness to say that only 34 (or 31) per cent of the public wanted the reform. And it is pretty clear that there is a stronger weight in favour than against.

Without that information, Shortlist could have been correct. It could even have been the case that the question had been:

Do you STRONGLY support nationalisation of the railways:

Yes: 34

No: 60

Don't know/no particular feeling: 6

But that's the only type of situation where the conclusions being drawn are valid. It could also, of course, have been:

Do you STRONGLY support nationalisation of the railways:

Yes: 34

No: 25

Don't know/no particular feeling: 41

... which feels very different from the previous result.

This is why we need more breakdown of information when such surveys* are presented. The headlines can be totally misleading. And it would help if the responsible pollsters, which I believe YouGov to be, gave rather more information, like question and range of responses, to make sure that we know what the statistics really indicate.

* Thanks to Freddie Sayers of YouGov for also emphasising that it wasn't actually a survey, but rather data extracted from the profile information of YouGov members.

Published on September 01, 2015 01:19